On a brisk April morning at the University of Kansas, a group of scholars and veterans of the American war in Vietnam are meeting for a sweeping discussion on manpower and morale issues after the 1968 Tet offensive. While the conversations are engaging, the veterans, nearly all men now in their sixties and seventies, noticeably are most impressed with the luncheon speaker, Chris Noel. Host of the Armed Forces Radio show “A Date with Chris,” the former actress and pin-up model was a favorite among GIs serving in Vietnam. It is clear she still is. Wearing a tiger-stripe camouflage blouse over her bright red pantsuit, Noel stands tall in cowboy boots, each emblazoned with an embroidered American flag. She is contagiously cheerful, full of energy, and her respect for the roomful of vets is undeniably genuine. They wait patiently in line to have their photographs taken with her, wide smiles on their faces.

Noel holds some papers in a black notebook, which she briefly peruses before setting them aside. She scans the room and then straightaway apologizes to the women in the audience. It seems odd, but she explains. Yes, there were women in Vietnam – Red Cross volunteers, USO entertainers like herself, and female nurses. But, she pauses for effect, “This was a man’s war!” Noel shares how she traveled to Vietnam as a young woman to “go build up the morale of the troops.” It was humbling to serve, she says, yet something happened along the journey. “It turned me from a young girl into a woman, just like it did for the men in Vietnam.” Her comments are brief, yet Noel leaves with one simple message: “These guys were the best in our society.”1

Some fifty years after American troops had begun their unheroic withdrawal from Vietnam, Noel’s comments suggest the myth of war turning boys into men has not much suffered from the weight of history. Yet in the late 1960s and early 1970s, a new generation of draft-eligible youths were questioning the orthodoxy of war as a man-making experience. In the process, men’s adventure magazines faded in popularity. The pulps could no longer attract readers from a society uneasy with, if not mobilized against, hypermasculine images and bloody war stories. Amid an avalanche of social change in the early 1970s, men’s mags became a relic of the Cold War past.2

While the sexual liberation and counterculture movements posed stark alternatives to pulp conservatism, a new wave of “radical” feminism proved just as equipped to defy the macho narratives of men’s adventure magazines. Feminists spoke out against a gendered “caste system,” arguing that women were “oppressed as women, regardless of class or race” and appealing to Americans for an end to “male dominance.” The very definition of masculinity seemed under assault.3 No wonder pulp stories tendering advice on how to “keep a woman sexually subjugated” looked increasingly anachronistic by the late 1960s. Nor did stories on “grimy beatniks” who “disgrace us abroad” find much traction among those young readers willing to contest US foreign policy in Southeast Asia and the well-heeled elite in Washington, DC. As America’s Vietnam war began winding down, even the term “macho” – within some circles, at least – came to be seen as a “dirty word.”4

Out of synch with the cultural revolutions of the early 1970s, adventure mags blending war and sex offered little of value to a new generation of young male readers. True, long-standing Cold War gender anxieties remained. In February 1970, Bluebook warned of a new “assault on American virility,” where “inverted sex practices” were making it difficult to determine who was straight and who had “given over to homosexuality and other sex aberrations.” Worse, women had taken on an “aggressive role” and were demanding that men be “submissive regardless of what it may do to him.” By the time of publication, though, stories like these sat uneasily alongside more modern social and cultural constructions of masculinity, suggesting that a universal model of manhood as had long been depicted by the pulps actually never quite existed.5

Neither did pulp writers and editors find that war stories were as easily transmitted to young men coming of age in the mid to late 1960s. Compared with World War II, Vietnam tales lacked popular appeal. A stalemated, bloody conflict, punctuated by the public awareness of atrocities like My Lai, hardly inspired military service, thus contesting the symbolic power of war itself. By the latter stages of Vietnam, veterans like Tobias Wolff were questioning their convictions of war as a man-making experience. As Wolff recalled, the whole ordeal was just “something I had to get through.” When fellow vets returned home with disappointed aspirations of being lauded a hero by an appreciative nation, the warrior myth appeared even more wanting. For the pulps, there was little nostalgia in looking back upon such an unpopular conflict.6

Moreover, the American war in Vietnam complicated questions over who was good and evil. The one-dimensional, triumphalist narratives of earlier pulp stories and comic books no longer held up when compared with unfavorable news reports and veteran narratives. One vet who served three combat tours in Vietnam could not make sense of the evil he had seen or become. “I mean real evil. I wasn’t prepared for it all.” How could American GIs be “just warriors” if they were horrified at what they had turned into?7 Pulp writers took note, Mario Puzo recalling that he could pen only a handful of tales on Vietnam because the topic was “absolute poison.” According to the author of The Godfather, readers “hated” Vietnam because “we weren’t the heroes.” By the early 1970s, even Sgt. Rock comics were ending their stories with “Make War No More.” As legendary comic book artist and editor Joe Kubert explained, “I wanted to make it clear that, despite the fact that I was editing war books, we were not glorifying war.”8

The pulps also retreated from the glorification of war. Covers no longer displayed the lush artwork of Mort Künstler or Samson Pollen, instead featuring photographs of female models in various states of undress. With the popularity of magazines like Penthouse, Oui, and Swank in the 1970s, men’s adventure magazines ultimately made the leap into the “skin” market. As the editorial director for Stag and Men, Noah Sarlat, rationalized in late 1976, “We try to reach the guys who want to read sophisticated magazines like Playboy and Penthouse but can’t understand them. We have no pretensions.” Stag’s covers occasionally promised a riveting World War II story, but the magazine became explicitly more sexual by the middle of the decade. The May 1976 issue, for example, leads with bare-breasted cover model Nellie Bridge staring seductively into the camera, the list of stories beside her proof that this is an “all-new Stag” with “more girls” and “more daring.” Potential buyers are enticed with a review of the ten hottest porno films of 1976, a male/female masturbation handbook, and X-rated answers to readers’ wildest sex letters by porn star Tina Russell. Tales of adventure, war, or heroism are conspicuously absent.9

If the magazines’ more sexually explicit material suggested a temporary rending of war from popular definitions of masculinity, the acceleration of sexual liberalism in the late 1960s and early 1970s placed additional obstacles in front of pulp writers who hoped to reassert traditional gender hierarchies through their stories. This sexual revolution encouraged a wider acceptance of pornographic images and films in mainstream popular culture. Even Gerard Damiano’s Deep Throat, a 1972 X-rated release, earned reviews from leading film critics Judith Crist and Vincent Canby.10 While detractors slammed the obscenity and exploitation of women in these movies, a rising number of Americans came to approve of sexual activity between unmarried partners. The cultural landscape clearly was shifting. Though magazines like Hustler continued to view the female body as an object for consumption, increasingly more women than ever before were willing to contest being stripped of their public voices and demand they take part in the singles culture that the sexual revolution had inspired.11

No less challenging to a militarized sense of masculinity, women’s participation in the All-Volunteer Force (AVF) also complicated narratives that war was just a masculine endeavor. As the draft law expired on 1 July 1973, the armed forces no longer could rely on conscription to staff their formations. Concerns over manpower shortages helped stimulate recruiting efforts aimed specifically at female recruits. Their participation in the enlisted ranks exceeded expectations, rising from 1.3 percent of the total force in 1971 to 7.6 percent in 1979.12 Traditional male attitudes, however, proved savagely resilient. Vietnam veteran and future Democratic senator James Webb wrote a scathing piece in the November 1979 issue of The Washingtonian titled “Women Can’t Fight.” The Annapolis graduate lamented that civilian policymakers, by allowing in female midshipmen, were attempting to “sexually sterilize the Naval Academy environment in the name of equality.” To Webb, the entire process of combat leadership training had been undermined, and the nation’s military forces were “doomed to suffer the consequences.” Lest Americans think these views were confined to bitter Vietnam vets, conservative antifeminist Phyllis Schlafly argued that the “very idea of women serving in military combat is so unnatural, so ugly, that it almost sounds like a death wish for our species.” Resistance to changing gender norms thus ranged from outright disdain of women to sheltering protectiveness.13

Defiance to the US armed forces’ supposed feminization equally could be found in the rise of a paramilitary culture in the mid and late 1970s. It is no coincidence that Soldier of Fortune magazine started in 1975, not long after traditional adventure magazines, combining war and sex, had fallen out of favor. If “stag” mags were going to focus more on sex, then Soldier of Fortune: The Journal of Professional Adventurers could retain the macho pulps’ emphasis on wartime heroism and martial masculinity. By embracing a re-imagined warrior ethos, veterans of the recent war in Southeast Asia might find redemption from their disenchantment with the outcome of Vietnam. Not surprisingly, in these “new” war stories, vengeance took center stage. Beginning in 1980, Soldier of Fortune even started publishing classified ads to hire would-be mercenaries. Veterans could market their expertise as a “jungle warfare” or “weapons specialist,” suggesting an authenticity to this new form of men’s magazine. Apparently, a market existed. Major news outlets like the New York Times reported an increase in crimes committed by perpetrators hired from the Soldier of Fortune classifieds. Perhaps “real” men capable of action still roamed post-Vietnam America.14

Hairy-chested adventurers certainly were operating overseas. In the late 1970s, hundreds of American mercenaries, mostly Vietnam vets, traveled to Rhodesia and Angola to fight on behalf of the white minority governments there. Troubled that the United States wasn’t doing enough to halt the spread of communism in Africa, these guns-for-hire saw it as their duty to respond to recruiting ads in venues like Soldier of Fortune. As one mercenary lamented, “The West isn’t doing its job. The US especially isn’t doing its duty. If they’re too scared to fight the Communists, then people like me have to act independently.” Even former Special Forces Sergeant Barry Sadler, who catapulted to fame with his 1966 hit “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” eventually moved to Central America, running guns and authoring the popular Casca pulp novel series. Arguably, many of these mercenary soldiers traveled to global hotspots hoping to prove their masculinity after a failed American war in Southeast Asia. Sadler intimated that might be true for him. “The hardest thing to do,” he recalled, had been “to live up to the illusion of those who wanted me to be a hero.”15

In fact, stories of returning veterans hardly lived up to the ideals proffered in men’s adventure mags. Popular stereotypes certainly overemphasized the broken, maladjusted warrior image. Closer to the truth, the vast majority of Vietnam veterans returned home to pursue successful lives unencumbered by the aftereffects of war. Still, boys had not come back as victorious heroes who had symbolically earned their manhood. Rather, much of an ambivalent American society viewed them as either victims or survivors of a bad war. (Most female veterans were not incorporated into this narrative for well over a decade after the 1975 fall of Saigon.)16 The whole experience seemed terribly unfulfilling. As one veteran remembered, “If this was manhood, I would prefer to have remained a child.” Vietnam had thus turned the macho pulp narrative on its head. Heroic masculinity seemed farther out of reach thanks to the war, not the principal reward for a job well done.17

However, discerning pulp readers might have expected that not all vets adjusted so easily to their postwar lives. An editor’s note at the end of a 1961 Man’s Magazine story on “The One-Man Army of Bataan” remarked how the World War II hero Arthur W. Wermuth had divorced and was drifting “from place to place.” In civilian life, the Silver Star awardee “did not adjust too easily,” toiling away in a service station, selling pharmaceutical supplies, and joining a flying circus. Even Bill Mauldin’s famous characters Willie and Joe are found struggling in a postwar world. In a Man’s Day feature from early 1953, we see Willie “back to fighting with his wife” and working a forty-hour week. Joe, single, “drifted languidly about, hoping for bigger and better veterans’ bonuses” before re-upping in the army and heading to Korea. Nor were these strains pure fiction. In early 1962, Stag included a full-page photo of a Korean War veteran brandishing a rifle on a housing development rooftop and threatening to shoot anyone who came near him. Policemen persuaded the ex-GI to surrender, but the episode revealed potential long-term emotional and psychological consequences of serving in combat.18

Popular accounts of Vietnam veterans struggling to reintegrate into society, of being violent or drug-ridden, followed suit and proliferated in the early 1970s. The comparison with stable and heroic World War II vets appeared stark. Yet narratives of the “greatest generation” conveniently sidestepped the fact that there was an enormous amount of self-medication and of struggling to adjust within the veteran community. Somehow, alcohol use (and abuse) in 1950s VFW halls seemed far more socially acceptable than smoking marijuana on college campuses a decade later. True, for instance, ran a rare story in late 1968 on “pot-smoking veterans” who potentially might threaten the nation’s social and moral equilibrium. “Tens of thousands of veterans are returning every month from Viet Nam,” the magazine warned, “most of whom have smoked marijuana at least once.” If marginalized, disenchanted veteran-addicts returned home emasculated by a futile war, anxious Americans worried about a surge in domestic violence unleashed by an untold number of “walking time bombs.”19

By the 1980s, the veteran as victim plotline had run its course. With a patriotic commander-in-chief now labeling Vietnam a “noble cause,” a paranoid insomniac from Taxi Driver (1976) or a flashback-plagued vet in Heroes (1977) surely did not encourage a national narrative of regeneration and redemption.20 Instead, hypermasculine heroes, with excessively muscular bodies, landed on the big screen with a vengeance. Sylvester Stallone’s Rambo not only returned to Vietnam to rescue American POWs and finally defeat the Vietnamese communists, but also uncovered the deceit of government bureaucrats who had helped lose the war in the first place. Rambo might struggle at home, but American society clearly had not emasculated this brutally violent warrior. The brawny Vietnam vet would have been right at home within the pages of men’s adventure magazines.21

This Reagan-era remasculinization of the Vietnam veteran suggests that popular notions of gender and masculinity can, and do, change over time. If gender is a social construct, then it remains a malleable concept as long as society continues to reevaluate its norms and values. Moreover, definitions of “heroism” and “manhood” can be used as political tools, reinforcing or, alternatively, challenging the power relationships between men and women. While the macho pulps may have fallen out of favor in the early 1970s – in part, as a consequence of second-wave feminism – the reemergence of fearless warriors like Rambo in the mid 1980s left little doubt that America’s distaste with militarized masculinity was only a temporary phenomenon.22

Remembering War

War stories are more than just tales of military engagements. They tell us something about how and why societies desire to remember war and, particularly, their male veterans in certain ways. While these stories are affected by larger cultural influences, they also help to shape social attitudes as well. For example, young men’s conceptions of manhood and what they deem as appropriate behavior are influenced by a variety of sources: social, cultural, political, and familial. In the 1950s and 1960s, men’s adventure magazines were a unique part of this socialization process. By melding together stories of war and sex, they helped sustain, if not validate, a larger cultural narrative defining gender as a hierarchy of power relationships. In the macho pulps, heroic warriors and sexual conquerors reigned supreme. Even if Cold War-era men fretted over losing their masculinity in a consumeristic, post-World War II society, they still could look to pulp champions as proof that men mattered most.23

Many Vietnam veteran memoirists emulated the basic characteristics of men’s adventure magazines. Most certainly, these writers were angry and contested the idea that war was an ennobling experience. Yet their focus centered upon the male warrior in combat. Among the more popular remembrances, Peter Goldman and Tony Fuller’s Charlie Company was touted as the real-life exploits of a “gook-hunting, dirt-eating, dog-soldiering combat infantry unit.” The book’s subtitle, What Vietnam Did to Us, also alluded to the belief that these warriors were victims far more than the local Vietnamese. Yet these men remained masters of war. In John Del Vecchio’s The 13th Valley, we meet Egan, a natural fighter with a “healthy animal paranoia.” In one episode, he trumpets to his platoon mates, “War. It’s wonderful. It don’t make a gnat’s ass difference who the enemy is. Every man, once in his life, should go to WAR.” Even in the most dissatisfying of wars like Vietnam, where veterans decried their lost youth, readers might still glimpse the prospect, however small, of becoming a hero.24

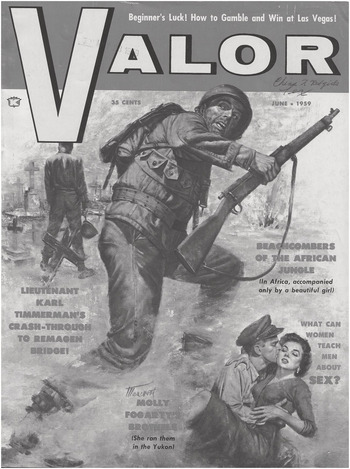

Fig. C.1 Valor, June 1959

And while warriors weren’t to blame for a lost war – one returning vet making note of a cab driver railing against the “damn politicians” and “bleedin’ hearts” – memoirs and novels retained the pulps’ dominant narrative of sexual conqueror. A vicious rape, for instance, is at the heart of Paco’s Story by veteran Larry Heinemann. “If the zip had been a man,” the narrator shares, “we would not have bothered with the motherfucker, you understand that, don’t you?” Other tales focused on the easy access to purchased sex. Bo Hathaway’s novel, A World of Hurt, relies on popular Orientalist language as a Vietnamese prostitute entices a GI with “You fuckee now. Fifteen minute we fini.”25 When John Ketwig nervously enters a brothel for the first time, he meets Lin, who seems to emerge from most any pulp magazine. “I want very much to go with you,” she says gently. “I enjoy my work, and I want very much to make you feel good.” Such sexually violent and sexualized imagery suggested that the cultural stereotypes linking war and sex had retained a central place in how veterans and writers were remembering the American war in Vietnam.26

This cultural construct endured long after Vietnam. In the mid 1980s, Playboy ran an essay on US military bases in the Philippines, the “last frontier” with “beaches and bars and girls and everything cheap.” As one young officer shared, “I can live here the way the British lived in India in the days of the Raj.” Writing for Esquire during the same period, Vietnam vet William Broyles remembered going off to war with a copy of War and Peace and The Charterhouse of Parma stuffed into his pack. “They were soon replaced with The Story of O.” As Broyles argued, “War heightens all appetites.”27

A generation later, as Americans were immersed in another overseas war, this time in the Middle East, the story of Vietnam as a venue for sexual opportunity had changed little. National guardswoman Mickiela Montoya recalled meeting a man in Iraq who claimed the “military sends women over to give the guys eye candy to keep them sane. He said in Vietnam they had prostitutes to keep them from going crazy, but they don’t have those in Iraq. So they have women soldiers instead.” Philip Klay’s 2014 award-winning novel Redeployment hits upon a similar theme, with an entire chapter titled “In Vietnam They Had Whores.” In the story, a group of deployed marines are eating in a chow hall when a woman passes by. “You know,” one of them says, “sometimes, girls who wouldn’t give you the time of day when you were in high school change their minds once you’re a war hero.”28

And, yes, heroism still could be found in war, even in seemingly meaningless ones like Vietnam. In We Were Soldiers Once…and Young, Harold Moore and Joseph Galloway share the “unbelievable heroism” of 1st Cavalry troopers defending a Central Highlands landing zone (LZ) against infantry regiments from the North Vietnamese Army. When Mel Gibson’s film adaption hit movie theaters in 2002, veteran Philip Beidler remembered how he “shed some silent tears for the defenders of LZ X-Ray at the end.” If Americans couldn’t sell themselves to Vietnam in the 1960s, it seemed they finally were having success selling Vietnam back to America in the decades that followed. The success of We Were Soldiers Once suggests a symbiotic relationship between heroes and how we remember war. In short, how could someone become a “hero” if their story wasn’t told? Pop culture renderings like movies and adventure magazines helped maintain the possibility that the title of “hero” remained ever within reach.29

The macho pulps surely reinforced narratives in which triumphant battlefield exploits and heroic deaths far exceeded tales involving veterans suffering through post-traumatic stress or feelings of guilt and alienation. Rarely did adventure mags relay the rage of vets like Robert Muller, who felt like he and his fellow marines “were used like fucking cannon fodder in Vietnam.” Only rarely would pulp readers get a glimpse of veterans like Sergeant Al Drabik, the first GI across the Remagen Bridge into Germany in World War II, who, in 1966, was fifty-four years old, an out-of-work butcher, and a part-time cement factory laborer. More common were tales such as “John Barrow’s Sex Colony.” In this 1964 offering from Men, a “brawling ex-GI with an unquenchable thirst for women and adventure” builds a “private paradise on a South Pacific island, stocked … with a supply of silk-skinned, burning-eyed girls from all over the world.” Clearly, Barrow’s “tropical love heaven” was far better than Muller’s VA hospital inhabited by “fucking drunks and derelicts and degenerates.” In pulp fantasy stories, ex-GIs effortlessly retained their physical brawn and sexual appeal.30

Men’s magazines seemed to be the solution to so much, cultural guidebooks for attaining one’s manhood through valorous combat and sexual virility. They were the antidotes to men’s fears and anxieties – over their masculinity, their unease with women both at home and abroad, and their concerns about not measuring up in a competitive Cold War era. Their influence could be seen not only in PX sales in Vietnam, but also in the ways in which GIs made sense of the war. The popular humor magazine Grunt Free Press, first published in 1968, has the distinct feel of a pulp mag. In its first issue, Grunt, dubbed the “Magazine for Men in Vietnam,” included a story asking if Vietnamese women were the most “beautiful” in the Orient, as well as cartoons of nude Asians seducing American GIs, whether in a foxhole or in a bedroom. Chris Noel, wearing white leather boots and a mini skirt, graces the pages, though she remains anonymous to the reader – “who pays attention to faces or names?,” the caption asks. And yet despite its sexist, nonconformist outlook, Grunt Free Press still conceded that men in uniform and the weapons they carried were “instruments” for the “preservation of a society, a way of life.” Apparently, even rebellious periodicals could push the boundaries only so far.31

For many veterans, however, the Vietnam experience repudiated much of what the pulp magazines had been selling for so long. War wasn’t heroic or manly. Asian women weren’t submissive or a remedy to war’s disillusionments. Mel Gibson may have been inspirational on the big screen, but moviegoers did not share in the recollections of Hal Moore’s troopers, who looked in the mirror every night and thought of “all those guys killed in action, wounded in action, and their friends, their relatives and all those altered lives.” The real war left behind sorrow and pain, anger and frustration, self-pity and regret.32

It is important, then, that we think more deeply about how we remember and how we portray war in our popular culture. Young men often find meaning in images and structures of male superiority, especially when the protagonist is a bold, heroic warrior. They take voyeuristic pleasure in viewing the destruction of war. They are enticed by the anticipation of sexual encounters with and rewards from exotic foreign women. Arguably, they also feel embittered when the reality of war betrays them, leading to a pursuit for retribution, whether militarily or sexually. Along the way, many veterans also question the promise of war as a man-making endeavor. As David Donovan noted of his time in Vietnam, “I wanted so much to be a child again, not a man beset by the dogs of war.”33

But in popular culture, John Wayne, the movie star, never had to grow up, never had to experience for himself the nuances and hardships of modern combat, never had to deal with the aftereffects of war. Even in The Green Berets, there was no victory by movie’s end, only more fighting. As the American war in Vietnam came to a close, disappointed veterans were left to balance the weight of culture in relation to their own experiences. Many found the war wanting. Whether in John Wayne movies or men’s magazines, the reality of war never quite matched the adventure and romance depicted in popular culture. The pulps, it turns out, mostly had been a façade.34

In the end, socially sanctioned versions of heroic warriors and sexual conquerors carry weight. How we remember war matters, and the ways in which we look back upon the past have consequences. This is why placing men’s adventure magazines within their proper historical context is worthwhile. There are social, cultural, and political ripple effects when we accept, as a “natural” imperative, images of men being overtly masculine, having free range over all others, and taking what they want without penalty. The concepts of gender and masculinity, however, need not be fixed. Thus, it seems important that we search for alternative narratives, ones in which manhood is not simply defined by military heroics or sexual conquest.35

Redefining Masculinity and the “Adventure” of War

If Vietnam vet William Broyles indeed had replaced a copy of War and Peace with The Story of O in his wartime rucksack, he more concretely argued that the “enduring emotion” of war was comradeship. Men, and men alone, shared in the brutal spectacle of war, the “only utopian experience most of us ever have.” There were other reasons why men loved war – the power of life and death, for instance – but Broyles lavished praise on the connections between “sex and destruction” that touched the “mythic domains of our soul.” While the former Newsweek editor acknowledged that soldiers suffered death and isolation on the battlefield, he nonetheless gave the impression of war being the ultimate romantic, man-making experience. As Broyles argued, it was “no accident that men love war, as love and war are at the core of man.” Just one short decade after Americans had departed Vietnam, war, it seemed, was back in fashion.36

Broyles’s language and assumptions are insightful, for they demonstrate the social power of pop culture gender constructions and their relationship to war. Veteran narratives, whether in men’s adventure magazines or in memoirs, help normalize expectations about uniformed service and manhood, about military occupation and sexual abuse. In the process, these gendered tropes become embedded in larger popular culture. When a young soldier in the 25th Infantry Division, for example, noted how there were a few rapes and sexual assaults in his division’s area, but “nothing, unfortunately, out of the ordinary,” what did this say about his definitions of “normal” in a wartime environment?37 Such thinking could not simply have been an outcome of military indoctrination. When Men ran articles on a “treacherous nymph” who sold out the US Navy at Pearl Harbor or Saga described Korea as “a good-looking woman with gonorrhea,” this form of socialization not only reinforced the experience of military basic training, but corroborated how young readers already were inclined to think about war, power, and masculinity.38

Without question, the macho pulps were an escape, a way to behold brave men who had surmounted the limits of an emasculating, consumeristic society. These adventurers held no fears of not being able to measure up. They were supermen, in battle and in bed. The cover alone of the April 1966 issue of Men in Adventure said it all – “hard hitting stories of war adventure and sex” that promised “war and pussy galore.” Yet many of these tales were fabricated by pulp writers. Fiction melded imperceptibly into a constructed form of reality. Walter Kaylin owned up to the fact that he and Mario Puzo once ran out of major battles to feature in their stories. Their solution? They made one up. As Kaylin conceded, “It was a battle so close to Anzio and just as fierce. Nobody would have ever heard of it. It was a completely mythical battle, which Mario wrote about in great detail and nobody ever questioned it.” Perhaps it didn’t matter. As long as readers could revel in a sense of adventure, pulp writers had achieved their goal.39

For veterans, in particular, the pulps allowed them to hold onto their battlefield experiences, a social forum articulating how their military service was noteworthy and still valid. Adventure magazines ensured their stories were not forgotten. They might even help with the transition to postwar life, granting them access to others who also had seen some of war’s horrors. Yet these potentially beneficial aspects of the pulps have to be balanced with their more negative attributes. Adventure mags reinforced ideas of hypermasculinity and militarized notions of manhood, and amplified the damaging influence of aggressive sexuality. These traits could be passed down to the next generation of young warriors just as easily as tales of sacrifice and comradery. It seems likely that only reflective readers would have caught these important distinctions.

The macho pulps, however, were not known for their nuance. In general, they imagined war and sex based on unrealistic conceptions that were pervasive in Cold War popular culture, ones that were grandly heroic and lustfully violent. It would be wrong, however, to assume these visions evaporated in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The editor for John Bahnsen’s memoir American Warrior, published in 2007, relished in the pulp narrative decades after the market gave way. “Mythical military heroes,” Wess Roberts claimed, “are often made out as larger-than-life figures who are fierce fighters, brave beyond compare, invincible in battle, loyal to their soldiers, faithful to their duty, defenders of their country, yet cursed with a weakness for beautiful women.” That Roberts saw in Bahnsen all these features, thus confirming his status as an “American warrior,” goes far in revealing the continuing allure of militarized definitions of masculinity and the supposed adventure that war provides.40

It seems important, then, to consider how the American experience with war has been affected by soldiers who carried with them popular narratives of the heroic warrior and sexual conqueror that proved so elusive in reality. In a way, the pulps helped to miscommunicate to their readers, if not society at large, soldiers’ experiences in the Cold War era. That led to future working-class warriors making faulty assumptions about military service, war, and the relationship of gender dynamics to both. One veteran, clearly wrestling with his guilt after killing a Vietcong insurgent, shared how inaccurate perceptions of war had left their emotional mark, long after his actions in combat. “I felt sorry. I don’t know why I felt sorry. John Wayne never felt sorry.”41 Nor did any of the heroes in men’s adventure magazines. Pulp warriors never suffered the consequences of war.

But real soldiers do. And because they do, we all should question versions of war that rely on a warped sense of militarized masculinity. When former Marine Corps Commandant Robert Barrow testified to congress in the early 1990s that “you have to protect the manliness of war” and thus keep women out of combat, he was touting a cultural construct that proved central to men’s magazines. It’s unclear if Barrow ever read the macho pulps, but his language reflected a way of thinking that would have been familiar to adventure readers. Similar assessments could be found well into 2018. One marine veteran writing for The Federalist outlined a host of reasons why only men should serve in infantry units: women get pregnant, they undermine unit cohesion, they have less muscle mass. Besides, the vet claimed, “Men were created to be protectors – protectors of their homes and protectors of society.” A pulp aficionado in 1958 or 1968 likely would have agreed with the author’s assertion that war was a “man’s environment.”42

While sexist attitudes like these clearly persist, it remains possible to rethink the associative relationship between culture and experience when it comes to war. We can, and should, develop a sense of critical thinking among our warriors, opening up the possibility of them questioning long-held tropes of war and sex. Not all pulp readers were seduced by the assumption made in offerings like Saigon after Dark that it was “only natural that the GI looks for solace in the silken arms of a woman after a grueling day dodging death in the rice-paddies.” One soldier responding to a Stag article on reducing VD rates argued that “there must be a better way than encouraging prostitution.” Another GI serving in Japan wrote to Man’s Magazine, declaring that there “is a lot more over here than pure sex! There are plenty of exotic places to visit and unusual things to do without the habitual emphasis on women.” If at least some Cold War readers were willing to rechannel their energies away from hypersexual notions of American manhood, then surely we too can reconsider the ways in which we tell stories of war and masculinity.43

The challenge, it seems, is moving beyond the various pulp conceptions of “normal” male behavior. War need not be the only, even primary, rite of passage into manhood. Pop culture heroes should not rely on sexual conquest for our approval. Arguments invoking supposed gender inequalities to claim that the very nature of women disqualifies them for combat should not be part of the dominant narrative when it comes to debates over military service and even citizenship. Moreover, we should push back against clichéd portrayals of women in war – the sexy pin-up model, the exotic “Oriental” dragon lady, the duplicitous seductress, or the beautiful but deadly female sniper. War does not require sexual action on the part of the warrior. Popular narratives of what it means to be a man need not rest on soldiers dominating their enemy and women in the same breath.44

Redefining adventure in war may, in fact, help young men and women cope better with the realities they face when immersed in wartime environments. It is possible to be an empathetic warrior. Even in the midst of combat, one can be compassionate and benevolent without necessarily demonstrating impotence. The key is opening up conversations that offer alternate models of masculinity. The working-class pulp readers who ultimately went to Vietnam were both sincere and innocent, yet the prevailing representation of manhood they consumed bred only contempt for men who showed weakness of any kind. Adventure magazines’ idealized vision of militarized masculinity encouraged no other possible alternatives to aggressive behavior, either on the battlefield or in the bedroom. Male relationships were about power, pure and simple. Surely, there are other ways to conceive of interactions between men and women.45

Moreover, other tangible outcomes potentially surface when we consider alternate versions of pulp masculinity. Adventure magazines proved to be poor preparation for combat in South Vietnam, where the political war rivaled the military one. Power wielded by the NLF, for instance, oftentimes had little resemblance to the kind advocated in the macho pulps. Would a different version of the modern-day warrior have better equipped young GIs for their tours in Southeast Asia? And, if popular notions of aggressive masculinity helped to normalize violence against the Vietnamese, we might consider the plausible outcomes if Americans had thought differently about the civilian population. The physical and psychological toll on the Vietnamese was enormous, and US vets suffered as well. In fact, one recent study found that veterans who harmed civilians or prisoners in Vietnam were among those more likely to endure postwar trauma. Violence against noncombatants harmed victim as well as perpetrator, yet rarely in the pulps did readers confront this fundamental characteristic of war.46

Instead, adventure magazines fostered a version of masculinity during the 1950s and 1960s that arguably demanded conformity to a narrow definition of what it meant to be a man. To many working-class teens, contesting this popular interpretation risked social delegitimization and accusations of effeminacy. In such a way, the pulps’ influence on the emotional and social education of young readers appears fairly significant. It also seems likely that the magazines’ sexist, if not misogynistic, constructions of women, Asians in particular, may have encouraged GIs to view wartime sexual violence during the American war in Vietnam as somehow acceptable. In an era where far too many critics today problematically link video game violence to mass shootings, we certainly need to take care in arguing a causal relationship between wartime rape and pulp adventure. One was never a direct outcome of the other. Yet it is clear that adventure mags showcased, issue after issue, an obvious correlation between war and sex. Real men dominated their enemies, whether they be a Vietcong insurgent or an exotic “Oriental.”47

As inhibitions declined over time in a frustrating war, it may be that what the articles expressed became more stimulating to their readers. Pulp stories found interesting at home might have been more compelling as they connected viscerally with GIs who were tired, disillusioned, and frightened. Adventure tales may not have been marching orders for soldiers to engage in sexual violence, but they inculcated in their readers a sense that male aggression was central to success in the modern world. By implication, violence became associated with victory.48

In early March 1965, some 3,500 US marines landed in Da Nang, the first major contingent of American ground combat troops deployed to South Vietnam. The New York Times heaped praise on the marines who had “a historic reputation as a fighting force on the mainland of Asia dating back to pre-World War II days.” That same month, Male magazine featured a story by Mario Puzo on American GIs who had “turned Hitler’s top tank army into scrap,” before offering a piece on Korean “give-give girls” who were turning areas south of the 38th Parallel into a “wild pleasure grove.”49

Looking back, the prospect for adventure in the early spring of 1965 seems so palpable. A new war was about to offer young men a chance to follow in their fathers’ footsteps, to grasp the mantle of manhood that had been won against the forces of evil in the Second World War. The pulps would help inspire a new generation of American warriors who, in turn, would encourage their own sons to mature into courageous heroes. It all appeared so glamorous. Yet less than a decade later, men’s adventure magazines had faded into obscurity, the pulp fantasyland ruptured by a war that begat few heroes and far too many villains.50

In the end, the reality of Vietnam helped to discredit the macho adventure narrative, if only temporarily. Perhaps, this is why examining such a “low brow” form of Cold War pop culture still matters today. How we construct popular tales of war and masculinity, how we fashion our ideas on what it means to be a man, matters, especially when the narrative is found wanting. There are consequences when young men, encouraged by fantasy, assertively seek out opportunities to prove their dominance and come up short. Shattered illusions can result in disappointment and frustration, which then can lead to hostility and violence. There are costs when we idealize war as the essential man-making experience. The macho pulps of the Cold War era sold an appealing version of adventure to enthusiastic readers, but not all battles so easily place young men on the road to martial glory.