Across rural Senegal, local actors lament that their local governments suffer from weak resources and insufficient support from the central state. National political parties are only fleetingly engaged, leaving local officials alone with innumerable demands from constituents as villages petition for large investments like schools and with citizens passing constantly to seek assistance with medical bills or funeral expenses. Yet despite their shared challenges, data from an original survey with more than 300 rural Senegalese political and customary elites reveal striking subnational divergence in how local actors experience decentralized local governance. For some, decentralization is a boon, with the local state capturing a meaningful community that works well together. But for others, local governance has heightened political competition between neighboring villages and failed to deliver on its promises.

In this chapter I document this empirical variation to build the contours of my theory. I introduce the survey in the next section before drawing on open-ended questions to outline the dominant narrative arcs offered by respondents about their local political lives. In areas that were home to centralized polities prior to the onset of French colonial rule, local elites describe their local governments as unified and meaningful political entities. More precisely, they describe the properties of institutional congruence: respondents speak of powerful local social institutions that map onto the local state, leading elites to report feeling obligated to alter their political behavior. These attributes are absent in areas of incongruence, where interviewees describe splintered social relations among local elites that increase competition for control over the local government and the resources that come with it. Embedded within these narratives are the theory’s two mechanisms: the role of shared group identification and dense social networks are cited at length in historically centralized zones but are largely absent in local governments without histories of precolonial statehood.

The survey’s sampling design further allows me to examine two of the social shocks that might predict the erasure of precolonial identities that were introduced in Chapter 2. What happens, I ask, in communities that have seen substantial immigration or mass religious conversion, particularly in those local governments home to powerful religious figures? The survey data suggest that institutional congruence is relatively flexible, able to adopt in-migrants and new forms of religious practice to the extent that the twin mechanisms of cross-village social networks and shared group identification are preserved. Elsewhere, the arrival of such challenges enflames disputes over redistribution and representation. Still, these are not absolute truths and the survey demonstrates how institutional congruence can be attenuated by social shocks at the margins.

The chapter ends with a presentation of the survey’s quantifiable measures. Across a number of questions, I find consistent patterns to those emerging out of the qualitative data: respondents in congruent local governments are more positive about their local government’s performance and are less likely to allege unequal treatment, suggesting that narratives of local political life map onto reported experiences with local governance.

Original Survey Data

This chapter uses data collected from an original survey of Senegalese village chiefs and local elected officials conducted between February and July of 2013.Footnote 1 Formatted as highly structured interviews, the survey asked respondents questions about the history of their village and local government, their level of social service access, their evaluations of the economy and the local and central government as well as a host of personal details. Because the questions ranged from standardized to open-ended formats, the data are amenable to a qualitative and quantitative analysis.

I supplement the survey with interviews conducted with central state officials appointed to rural areas, notably the subprefect (the lowest central state administrator) as well as local development agents, both posted to the arrondissement, and officials at the Agence Régionale du Développement, or regional development agency.Footnote 2 Finally, I spoke with the local government secretary in order to collect data on local government activity. Secretaries are often best positioned to verify local government statistics, such as the number of meetings held in the previous year, because they are charged with keeping logs of this information. In the frequent occurrence where the mayor is illiterate, the secretary often has the clearest documentation of the local government’s recent procedures and activities.

In total, the survey covers fifty-six rural communities, sampled from Senegal’s forty-two departments. The survey’s central objective was to illuminate what, if any, empirical variation existed in experiences with local governance along the key axis of historical variation: precolonial statehood. To sample the antecedent independent variable, I purposefully chose fourteen departments that were balanced between areas that were historically centralized or acephalous as well as zones that had an intermittent history of precolonial statehood.Footnote 3 I further sought to ensure variation in exposure to migration patterns and geographic location. For example, all of Kedougou Region was acephalous and it is located far from Dakar while some departments within Tambacounda and Kolda Regions, also far removed from Senegal’s capital, were exposed to precolonial polities. Certainly, these factors are not invariant by department and some departments were chosen specifically because they are home to both historically acephalous areas and smaller states; here again, Tambacounda and Kolda Departments are good examples. Absent exact data on migration, I likewise approximated regions known to have experienced in-migration, such as the peanut basin or Guinean in-migration to the southeast, while cognizant that not all local governments within those units were equally affected.

A map of surveyed regions can be found in Figure 4.1.

Figure 4.1 Map of surveyed departments

Within departments, I employed a random selection strategy to choose local governments. Specifically, I randomly selected two arrondissements from within each department and, in turn, two local governments in each arrondissement.Footnote 4 This helps attenuate the concern that outliers on the independent (precolonial statehood) or dependent (local government performance) variables were intentionally chosen. In reality, I had relatively little information on selected units before visiting given the relative absence of publicly available data on local governments and local social characteristics. To date, I am unaware of any standardized metric of local government performance. In many cases, even the names of local mayors were not available until I contacted the relevant subprefect.

Within each local government, the mayor (or in two cases when the mayor was unavailable, his adjoint) was interviewed in addition to one or two local government councilors and four village chiefs, again all chosen randomly.Footnote 5 Chiefs were randomly sampled by assigning a number to each official village and using a random number generator to draw four numbers. In the event that the chief was unavailable (due to illness, travel, or, at times, old age), the next closest village was chosen.Footnote 6 Councilors were almost exclusively selected by again choosing a village randomly and asking if a councilor lived in that village or, if not, a neighboring one. In cases where multiple councilors lived in a village, we interviewed the councilor whose house we encountered first.Footnote 7

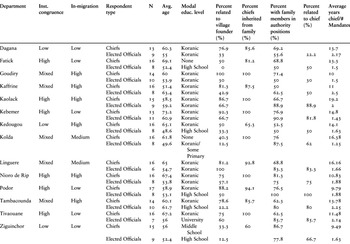

Descriptive data on interviewees, disaggregated by department, can be found in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 Descriptive statistics for local elite survey respondents, by department

| Department | Inst. congruence | In-migration | Respondent type | N | Avg. age | Modal educ. level | Percent related to village founder (%) | Percent chiefs inherited from family (%) | Percent with family members in authority positions (%) | Percent related to chief (%) | Average years chief/# Mandates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dagana | Low | Low | Chiefs | 13 | 60.3 | Koranic | 76.9 | 85.6 | 69.2 | 13.7 | |

| Elected Officials | 9 | 55 | Koranic | 33 | 55.6 | 22.2 | 2.17 | ||||

| Fatick | High | Low | Chiefs | 16 | 69.1 | None | 50 | 81.2 | 68.8 | 23.3 | |

| Elected Officials | 8 | 52.4 | High School | 0 | 50 | 50 | 1.5 | ||||

| Goudiry | Mixed | High | Chiefs | 14 | 60 | Koranic | 100 | 100 | 71.4 | 10 | |

| Elected Officials | 10 | 53.9 | Koranic | 30 | 50 | 30 | 1.5 | ||||

| Kaffrine | Mixed | High | Chiefs | 16 | 51.4 | Koranic | 81.3 | 87.5 | 50 | 11 | |

| Elected Officials | 8 | 63.4 | Koranic | 42.9 | 62.5 | 50 | 2.5 | ||||

| Kaolack | High | High | Chiefs | 15 | 58.5 | Koranic | 86.7 | 100 | 66.7 | 19.2 | |

| Elected Officials | 9 | 59.2 | Koranic | 66.7 | 88.9 | 88.9 | 2 | ||||

| Kebemer | High | Low | Chiefs | 13 | 73.2 | Koranic | 92.3 | 100 | 76.9 | 14.8 | |

| Elected Officials | 11 | 60.9 | Koranic | 66.7 | 90.9 | 81.8 | 1.43 | ||||

| Kedougou | Low | High | Chiefs | 16 | 65.1 | Koranic | 50 | 65.3 | 52.5 | 14.1 | |

| Elected Officials | 8 | 48.6 | High School | 33.3 | 50 | 50 | 1.63 | ||||

| Kolda | Mixed | Medium | Chiefs | 16 | 61.8 | None | 40.3 | 100 | 76 | 16.38 | |

| Elected Officials | 8 | 49.6 | Koranic/ Some Primary | 12.5 | 87.5 | 62 | 1.25 | ||||

| Linguere | Mixed | Medium | Chiefs | 16 | 65 | Koranic | 81.2 | 92.8 | 68.8 | 16.16 | |

| Elected Officials | 6 | 54.7 | Koranic | 100 | 83.3 | 83.3 | 1.66 | ||||

| Nioro de Rip | High | High | Chiefs | 16 | 67.4 | Koranic | 75 | 100 | 81.3 | 10.83 | |

| Elected Officials | 8 | 53.8 | Koranic | 57.1 | 75 | 75 | 1.88 | ||||

| Podor | High | Low | Chiefs | 17 | 58.9 | Koranic | 88.2 | 94.1 | 76.5 | 9.79 | |

| Elected Officials | 8 | 53.1 | High School | 50 | 100 | 100 | 1.88 | ||||

| Tambacounda | Mixed | High | Chiefs | 14 | 60.1 | Koranic | 78.6 | 85.7 | 62.3 | 13.78 | |

| Elected Officials | 10 | 61.7 | High School | 22.2 | 80 | 80 | 2.25 | ||||

| Tivaouane | High | Low | Chiefs | 16 | 67.2 | Koranic | 75 | 100 | 62.5 | 11.48 | |

| Elected Officials | 7 | 56 | University | 60 | 85.7 | 85.7 | 2.14 | ||||

| Ziguinchor | Low | Low | Chiefs | 15 | 56 | Middle School | 33.3 | 60 | 86.7 | 9.49 | |

| Elected Officials | 9 | 52.4 | High School | 12.5 | 77.8 | 66.7 | 1.63 |

Are These Narratives Accurate?

Much of the material presented in this chapter (as well as in Chapter 6) comes from open-ended survey questions or interviews with rural elites. The data I derive from these interviews are at times quantified, but I suggest that it is equally valuable as a lens into local political narratives. Taking the narratives individuals voice about their political experiences seriously emphasizes how individuals reason toward certain conclusions or reinforce certain beliefs or identities.Footnote 8 When local elites reinforce a narrative that local politics is either harmonious or disharmonious, they not only reflect on their political worlds but also reinforce the value of these narratives at the same time. Comments such as those by one village chief in the east of the country, “here politics takes a single form: it’s the interest of the elected officials and their party,” both reflect and reify alienation from political life.Footnote 9 Similarly, when respondents invoke a sense of shared identity or cohesion across the local government – for example, “We have different political parties, but we live in conviviality. We are almost all related” – they valorized a powerful sense of common fate.Footnote 10

This poses a risk: how do we know that the tales spun about the past actually matter, let alone whether they are accurate or not? I recognize that the stories people recount about their communities or the past may be untrue. At the same time, however, I question whether the past is a “limitless symbolic resource.”Footnote 11 In rural Senegal, historical narratives often appear bounded by cultural norms that set a framework for how the past is “remembered” in any given community. In no interview did elites claim a precolonial history when they fell outside the generally understood boundaries of the country’s precolonial politics, suggesting a limit to any opportunistic claim-making to a precolonial past, even when it would be relatively easy to do so to an outsider, such as myself. Still, this threat directly informs my multi-method strategy: employing quantitative and archival data as well as network analysis (see Chapter 6) allows me to cross-validate the patterns described to me by interviewees.

Ultimately, however, the truth matters less than the process of creating and recreating communal memories that are taken as truth. As the Italian historian Portelli (Reference Portelli1991, 50–52) explains, listening to people’s retelling of the past reveals that “what is really important is that memory is not a passive depository of facts, but an active process of creation of meanings.” This does not mean that our informants are not credible, but rather that the narratives they recount are as reflective of the symbols and beliefs that inform how they understand their past as they are of concrete sequences of events.Footnote 12

When rural Senegalese work through what it means to be a descendant of Sine or Fouta Toro, therefore, they at once provide an explanation for the boundaries that define a group while simultaneously making the identity collective by stipulating how individuals fit into this shared narrative.Footnote 13 A precolonial state may define an identity’s scope while also stipulating how they can assert their belonging, be it through tales of their grandfathers’ adventures, their family name, or the land they farm. These tales and memories may be inflated, but they nonetheless serve a critical role in the persistence of shared identities and collective norms alike. Indeed, I find remarkable consistency in the narratives told by elites both within any given local government and within the broad dichotomy I draw between historically centralized and historically acephalous zones. In this way, I suggest that listening to narratives of local political life offers us insight into key processes of norm creation and maintenance and the ways in which individuals reinforce the importance of local identities and shared histories in their daily lives.

Narrating Local Politics in Decentralized Senegal

I begin my analysis of the survey data by distilling two dominant representations of local politics from the surveys: regions where respondents invoke narratives of cohesive and territorially bound identities and areas where local governance is described as divisive, beset by politically rivalrous claims to the local state.

Narratives of Local Governance across Senegal’s Precolonial Geography

Respondents in local governments that fall in the footprints of Senegal’s precolonial states spoke about their local governments in distinctive ways that reveal two clear themes. The first is an idea of a common descent or shared heritage, even though these are at times partially imagined. For example, many respondents in Podor Department scoffed when asked to enumerate other local elites they were related to, responding simply that “we are all family here.” An equally common version of this is seen in the boastful comment of one village chief that there was no conflict in his community because “we are a single family.” Such responses should not lead us to immediately conclude that areas home to precolonial states are simply inhabited by one, large lineage. Like many who made such claims of familial ties, this specific village chief reported few immediate family relations with other chiefs or elected officials in his community.Footnote 14

This practice of adopting a broad rhetoric of kinship with community members even absent identifiable shared bloodlines is common in the West African Sahel as a means to reinforce community solidarity between lineages and settlements.Footnote 15 Communities often have strong narratives of shared descent based on family or clan, that may reflect friendship, “host” relations with in-migrants or cross-ethnic or cross-caste relations. As one community secretary in Senegal’s Wolof heartland described, the local government she worked for was cohesive and efficient. This, she explained, was because “almost everyone is related,” adding “there are many Sow, Mbaye, Ndoye in the rural community.” Typically, Mbaye and Ndoye are Wolof surnames, reflecting the ethnic dominance of the Wolof in the zone. Sow, however, is an ethnically Peulh last name. By including it as one of the “related” families in the community, the secretary reinforces the historical inclusion of Peulh minorities in her area.Footnote 16 Many historically centralized communities report such long-standing ties between non-co-ethnics, “I have almost no boundaries, they are all my family except for the Peulhs and they are my friends,” remarked a councilor in the Saloum.Footnote 17

The second theme emphasizes the value of social cohesion or the prioritization of preserving peaceful social relations. Respondents in historically centralized areas explicitly linked a collective commitment to maintaining social cohesion to the performance of their local governments. Political “colorings” or divisions were repeatedly suggested to be at odds with the historical ties that bound villages together. As a result, one councilor explained, “we put the common interest before politics here.”Footnote 18 This is not to deny social conflict, which is as prevalent in historically centralized areas as anywhere else. What differs, the survey data suggest, is the priority elites place on resolving conflicts with minimal social upset. Thus, for example, in Podor Department, which occupies the eastern stretches of the territory of the former precolonial state of Fouta Toro, long-standing sources of socioeconomic tensions related to caste and social hierarchy persist to the present. Still, one subprefect in Podor noted that elites in the communities he administered managed a “grand diplomacy” to avoid any issues escalating.Footnote 19

I argue that these are narratives of institutional congruence. Here, local histories are deployed to justify social institutions, particularly those around norms of social cohesion and conflict resolution, in ways that offer leverage on the reported behavior of elites. The presence of shared social institutions that are congruent with the local state generates pressure to be broadly representative and redistributive across the local government. Elsewhere in Podor Department, a local government mayor reported that his administration worked carefully with all village chiefs within his jurisdiction explicitly because everyone knew each other and claimed a shared descent from the region’s founders. Village chiefs in his community broadly corroborated this, noting that most villages had a councilor elected to the council, explicitly invoking their shared identity as shaping the right for everyone to gain equal representation.Footnote 20

In stark contrast to their centralized counterparts, interviewees in historically acephalous zones did not speak of social cohesion in the local government.Footnote 21 Local political narratives were more likely to center around social divisions between villages or political parties, with less extreme versions best described as narratives of dispersion, communities of numerous parts that didn’t sum up to a whole. This is reflected in the lack of a robust, unifying identity around any given community’s past.Footnote 22 What is distinct about these zones is not that they lack rich local histories, but that these histories do not encompass the local state as a whole. Respondents were more likely to narrate their history around the foundation of their individual village facilitating what Arcand and Bassole (Reference Arcand and Bassole2007) have dubbed “village capture,” whereby each village is seen as being out for themselves.Footnote 23 This was lamented upon even by elected officials themselves; one mayor in Kolda Region, for example, observed that budget meetings in his government were hindered by the politicking of councilors who only “wear the shirt of their village.”Footnote 24

Alternatively, some local governments were dominated by a specific clan or lineage spread over a handful of villages. In one local government, for example, the mayor was the descendant of the former canton chief. His family remained prominent in the area and a number of his extended family members were elected on the council. A central government official posted to the zone described the family as a “fortress,” adding that he had recently had to intervene during a local government meeting to ensure that all councilors were allowed to speak following the efforts of one representative from the “ruling” family to restrict who could comment during local council sessions. They “reign there,” the state agent concluded, and there wasn’t much the administration could do.Footnote 25 Indeed, some of the most intractable political fights seemed to arise when a small network of local elites, often based in a handful of key economic and political centers, dominated local politics. In contrast to narratives of cohesion and shared descent, the local histories recounted in acephalous zones were notably incongruent with local government boundaries.

The specific form that local political cleavages take displays remarkable diversity, therefore, but regardless of their content, respondents linked them clearly to local government performance. It was in historically acephalous areas that local government officials reported trouble meeting the quorum because of political divisions, with councilors knowingly choosing not to attend.Footnote 26 At times, these divisions were along lines of ethnicity or caste. One casted mayor in Tambacounda was obliged to pay for a car to go pick up all councilors of a higher caste – who would not otherwise pay to travel to a meeting led by a “casté” – if he wanted to meet the required quorum for local council meetings.Footnote 27 In Ziguinchor Region, many respondents lamented that the population could not overcome minor arguments to unite around anything. Even before the 1996 reforms, Darbon (Reference Darbon1988, 173) chronicled the intervillage tensions within some of the local governments in the region. In Mlomp, Oukout, and Oussouye, for example, historically rivalrous villages had been pooled into the local government weakening the ability of the newly formed local government to function properly. As one councilor in the Casamance explained, the Diola’s lack of hierarchical authority meant that while there was (and always had been) independence and equality between villages, this came at a cost: “it’s not like the North … [people here] all have arguments with each other and this means that they get less [services]” because mayors and parliamentarians alike felt little sense of obligation to their neighbors and constituents.Footnote 28

The political divisions recounted in historically acephalous areas were thus directly cited as impacting public goods delivery. One local government, under the rule of a special delegation following an administrative redistricting, was so internally divided along ethnic lines that even the special delegation was “blocked” and had been unable to execute any development project for more than seven months. The community secretary noted that projects, some of which the funding had already been delivered for, were at a standstill because of the political deadlock.Footnote 29 Complete blockage such as this is rare, but the perception dominated in acephalous regions that the only way to get something from or “have a say” in the local council was to have family or ethnic ties to a local councilor or, alternatively, to be a political ally of the ruling party.Footnote 30 “It is not a good political life here, because if you are not in power you are not represented at all,” one village chief surmised.Footnote 31

Why Social Institutions Influence Local Governance

Across historically centralized areas, local elites directly and indirectly described a central role for cross-village social institutions. As defined in Chapter 1, social institutions are norms of appropriate behavior in the public sphere demarcated by group boundaries. They are at once inherently relational – encompassing a relevant network of actors – while also necessarily tied to an identity category that imbues social institutions with meaning. This makes social institutions particularly motivating because they both externally and internally shape actor behavior: externally they offer social sanctions and rewards and circulate information about comportment, but they are also internalized by actors, leading them to think that abiding by any given social institution is an appropriate course of action.

The qualitative components of my survey reveal two key social institutions that embed elites across villages in cases of institutional congruence. First, elites observe norms of conflict avoidance. In Fatick Region, home to the precolonial state of Sine, respondents were particularly proud of their local social harmony, noting that local social institutions prevented political conflict or divisions between Muslims and Christians. “For us in [local government] our politics is limited to trying to solve our problems … we all know each other and that is why nobody dares create political conflicts,” explained one village chief.Footnote 32 Comments such as one community secretary’s in Louga Region, that during elections “everyone has their corner, but afterwards, that is put aside” for the sake of local development were repeated throughout areas that were home to precolonial states.Footnote 33

The second social institution is a norm of balancing voice and resources across villages. This is illustrated well in descriptions of the process of drafting electoral lists. One mayor was quick to clarify that in his position as a local party leader, he had to be careful to put individuals from a large number of lineages and villages on the list or risk being seen as biased or unfair, which would violate local norms.Footnote 34 This was described elsewhere as a geographical balancing act across villages or as a social one across lineages.Footnote 35 Of course, politicians everywhere desire to stay in power and cite delivering goods as the way to do this. Yet it was only in historically centralized regions that politicians proudly claimed to help those who had not voted for them.

Social institutions working behind the scenes shaped the behavior of local politicians and other rural elites. Mayors often lamented a lack of engagement by the majority of local councilors they served with, but they were also quick to note that they valued protecting the reputations of others in the local public sphere more than voicing their dissatisfaction. “You can sanction the act, but not the person,” observed one mayor, explaining that if a chief tried to build something, such as a granary, without passing by the local government council, the council would reject their request to grant the land parcel rather than critiquing the action outright.Footnote 36 Decisions to alter one’s behavior to protect social relations such as these reflect how local social ties stipulate costs while also reinforcing internalized social institutions, here around the value of preserving social harmony.

For many elites in historically centralized areas, the power of local social institutions was directly related to their understanding that their local government was an interdependent community with a shared fate, reflecting the two mechanisms that animate my theory. The presence of dense social ties and a strong sense of common identity were frequently cited as helping prevent deadlock from local political competition and as enabling the local council to find agreement. For example, one local government secretary told me that local social ties prevented “squabbles” with opposition party members from escalating, or, according to a mayor in Louga, that it kept politicians from conflating personal and political desires.Footnote 37 Indeed, political conflict was spoken of as a direct threat to long-standing social relations. Elected officials in historically centralized areas described this as a balancing act rather than a battle: we have to gain party militants to win, said one mayor in Thies Region, but this cannot be allowed to escalate because we “are all kin.”Footnote 38 These patterns were not only evoked by local elites. Even central state officials posted in these areas observed that dense social ties led congruent communities to find “amiable solutions” more often than not.Footnote 39

If the defining feature of local politics in areas that were home to precolonial states is the presence of cross-village social institutions animated by a shared social identity and dense social ties, then their absence goes a long way to explaining the political contention on display in historically acephalous zones. There was little, if any, reference to balancing goods and voice across communities in these areas. In many local governments, partisanship emerged as a vehicle for targeting services, in large part because it offered the most effective means of obtaining a majority or forming a sufficiently large voting block across otherwise disconnected social networks. The comments of two community secretaries illustrate this: “politics is all about who has the people behind him,” stated one, while his counterpart to the south had resigned himself to the fact that “politicians are only politicians … the interest of the party dominates.”Footnote 40

Not surprisingly, evaluations of local government performance varied roughly in line with those who considered their relations or allegiances to be in or out of local power. One subprefect in such a zone complained that village chiefs often came to him with questions rather than approaching their elected officials, noting pessimistically that elected officials would need to learn that they would need the local chiefs if they ever wanted to accomplish anything.Footnote 41 Respondents frequently noted that councilors in these regions only think of their own village, seeing the village as a more important entity than the local government as a whole, leading elites to orient projects toward their own villages as a result. Chiefs with no family ties to the local government were often simply disengaged, stating that they relied on themselves or villagers who had migrated to Dakar or beyond to help them. Decentralization hasn’t improved anything “because the rural community has the power now and if you are not on their side, you will not receive anything, even rice,” complained one chief.Footnote 42 This further impeded the circulation of information about needs across villages. To take one example, a village chief in Kaffrine Region speculated that while the local state hadn’t helped his own village, “perhaps they had in the others,” though he remained unsure since he did not speak to many other village chiefs.Footnote 43

This is not to say that no sense of collective identity emerged during interviews in acephalous areas of the country, merely that collective identities were incongruent with the local state, encompassing only part of the local government’s population in these areas. Respondents could clarify these lines of demarcation in great depth: one village chief provided a long list of all of the villages that he perceived as particularly advantaged in the local government by virtue of their shared history of arrival in the zone and ability to mobilize and dominate local politics.Footnote 44 Alternatively, minority ethnicities spoke of themselves as victims by virtue of their collective minority status (e.g. one Peulh councilor clarified, “the Wolofs [are more powerful] because the notables are from that ethnicity”).Footnote 45 In sharp contrast to their counterparts in historically centralized areas, respondents in historically acephalous zones noted splintered social networks within the local state, they did not espouse shared identities and politicians were reported to engage in far more opportunistic behavior.

Politicians in historically centralized areas also referred with great frequency to their social ties when explaining their political choices. This reflects in many ways the circulation of information across social networks. One community secretary described his local government’s broad family ties as the “cement” of the community; there are numerous social benefits, he explained, of “old men taking their horse carts from [village A] to [village B] to chat with their friends for the day before heading back home at night.”Footnote 46 Village chiefs also reported frequent contact with councilors in the area to discuss both personal and political issues. Many village chiefs pointed out how close they lived to the councilors from their village and reported that these same councilors (or those from immediately neighboring villages) informed them of what happened in the local government council.Footnote 47 Together, these factors led village chiefs in historically centralized areas to report strong relations with their local governments (e.g. “they are very accessible and they help us all the time”), often speaking of them with pride.Footnote 48

To substantiate the claim that there are subnational differences in the density of elite ties across villages, Figure 4.2 shows difference of means tests from more than 330 local elites interviewed in the 2013 survey, distinguishing between those residing in local governments that were home to a precolonial state, where I expect institutional congruence, and respondents in historically acephalous areas, where I expect incongruence. I asked each respondent whether they were related to other elites in their local government as well as a short list of central state officials. I distinguish between family and friendship ties for local elites, with family ties measuring both immediate (parents, in-laws, siblings, uncles, first cousins) as well as extended (second cousins, ‘la grande famille’) family relations. Respondents in centralized areas are significantly more likely to report at least one family tie to another elite (chief, elected official, imam, or marabout) in their local government and, at the 10 percent significance level, to report a friendship tie with another elite as well. These relations are broken down by type of elite.Footnote 49 In general, respondents in congruent local governments have more social ties with other local elites, though there is no difference in having a family tie with at least one elected official or considering a village chief to be a friend.

Figure 4.2 Difference in means in elite social ties

I adopt a more liberal definition for relations to central state elites to include reported relations of neighbors (e.g. someone from the village who now works in Dakar) or those that an individual reports having worked with in the past. This is both because the types of social ties are repeatedly invoked by respondents as meaningful connections to the center and because they are simply more common. Only eleven respondents, or 3 percent of my total sample, reported a family connection to their deputy. The data suggest that there is neither a meaningful difference in reported connections with central government bureaucrats (functionaries), deputies in the National Assembly nor the local subprefect. This suggests that historical experiences with precolonial centralization have not predisposed some areas of the country to systematically have better social conduits to central state favoritism.

Exceptions to the Theory

Collectively, this evidence accords with my theory. Respondents in historically centralized areas speak of their local governments as encompassing a meaningful community (cueing the identity mechanism) that shapes local leaders’ behavior by virtue of their dense social ties (cueing the network mechanism). Some or all of these parts break down in historically acephalous areas.

Though my theory is structural, it is not deterministic and the analysis above presents dominant, but not uniform responses. Historically acephalous areas do see forms of cooperation, with local elites making concessions to each other. One mayor in Kedougou Region explained at length the efforts he had taken to ease tensions with vocal critics in his local government’s capital village, intimating the political and social costs he would incur if he violated the delicate balance he was trying to establish with them.Footnote 50 Similarly, local governments marked by institutional congruence should not lead us to ignore cases where political disagreement does arise. Even in areas where local governance was broadly seen as positive, these narratives were not always universally voiced and non-confirming opinions are heard across the country. A minority of village chiefs in congruent areas complained of not receiving enough from their local government. What sets these complaints apart from those voiced in areas of incongruence is that inequality claims in historically centralized areas were predominately made on an ad hoc basis and were voiced by exactly those the theory would predict would have the least claim on local government resources: those with weak ties to dominant local political narratives, such as in-migrants or casted individuals.

In only a few cases did this appear to be actually driven by neglect on the part of the local state, in contrast to historically acephalous areas where having received nothing from the state was more common. For example, one village chief in Podor Department argued that his local government did not treat his village fairly. The chief, whose family was Wolof and had migrated to the area in the late 1880s, explained that his village which had only become officially recognized fifty years before and, though it had received a health hut and a primary school, an ongoing dispute over land within the community led him to conclude that although the idea of local governance was good, his local government “took sides too often.” “Decentralization is a bad system,” another village chief in Fatick with no social ties to his neighbors said, “because it favors the politics or the strongest of those with family relations in the council.”Footnote 51 In both cases, these chiefs felt excluded because they were “outsiders” whose claims were taken less seriously because of this status (despite the fact that both villages had been founded prior to Senegal gaining independence). Though neither village could claim that they had never received goods from their local council, they felt less included in an abstract, representative sense because their own settlement in the area did not fit into the dominant historical narrative of descent from the precolonial state. This reflects the central role of social network ties to the theory; under institutional congruence, local elites are more broadly representative, but the limits of this may be found at the network’s edges.

In villages with ties to dominant social networks, but who had not received much from their local government, respondents were much more likely to justify this inaction. Noting that his local government had not done anything for his village, one chief was quick to defend that “they don’t interfere either. If I go there with a problem they are patient towards me and are very attentive.”Footnote 52 Other chiefs speculated that they might get more if they had a councilor in their village, but that they never get one because their villages are too small to get someone a place on the party listsFootnote 53 or, more simply, that their villages have been diminished in size and statute and hence “we aren’t considered much anymore.”Footnote 54 Excuse making such as this is a sharp contrast to chiefs in equally small villages in acephalous areas, who never made such justifications for why they were relatively (at least in their view) underserved. Moreover, such complaints – even though at times seemingly warranted – are far rarer in the territories of precolonial kingdoms. Much more common are responses such as one chief’s that “the collective work is better” under democratic decentralization, directly calling on a sense of a common mission that was noticeably absent elsewhere in the country.Footnote 55

The Mediating Effects of Social Shocks

I have argued that distinct narratives of local political life are heard across rural Senegal, with a central cleavage being whether or not local elites view their local government as congruent with meaningful, cross-village social institutions. When they do, they invoke both a shared category – a social identity rooted in the precolonial past – and a dense network of social relations across villages. Together, these two mechanisms alter elite preferences and constrain elite behavior by imbuing elites with more prosocial preferences to the group. As introduced in Chapter 2, however, a series of major social shocks may have altered the composition of local elites and their social networks during the colonial and postcolonial periods. Could the politics of institutional congruence presented above obscure or be altered by these intervening forces? The sampling design of my survey takes into account two of the three factors introduced in Chapter 2: in-migration and religious conversion.Footnote 56 I address each in turn.

In-Migration

Attentive to demographic changes over the past century, I sampled local governments in areas that both had and had not seen substantial in-migration. As described above, interviews in historically acephalous zones suggest political narratives of social division; these tendencies are amplified in acephalous zones that had seen substantial in-migration over the past century. When in-migrants create new villages, they also create new claims to local social and political space that often parallel but only rarely integrate with those of the host population, effectively proliferating the social networks and identities present in a locality.

In general, historically acephalous areas that had seen in-migration displayed some of the most intense political competition and a bimodal distribution of attitudes toward the local government: the local council was representative and redistributive for those with ties to the current power-holders or it was biased and negligent for those without such connections. Though the nature of social cleavages varied – at times understood locally as falling along the lines of ethnicity, caste, autochthony, or partisanship – politics was decidedly zero-sum. Local politics, one subprefect in such a region described, is a “continual battle. Everyone is involved in the political terrain and they all want to occupy it.”Footnote 57 Indeed, the majority of interviewees in regions marked by substantial in-migration noted severe political blockage in the local council, preventing projects from being administered, taxes from being raised, and allowing mayors to flagrantly embezzle local funds.

One consequence was that political competition often fell along lines of how perceived rights to community resources were ordered following in-migration. In one local government in Tambacounda Region, twenty out of thirty-six councilors were elected from the capital village, the local government’s second largest village and among its youngest, having been founded by migrants along the colonial-era railway. The local government’s largest village was far older and had a long-standing rivalry with the capital over the latter’s perceived favoritism by the colonial state. This simmering conflict had been inflamed during the 2009 local elections when the mayor had allegedly changed the local electoral lists after party officials had signed off on it. Because the mayor submitted an altered copy to the subprefect, a large number of candidates from the older, larger village had been removed in favor of those from the mayor’s own native village, the local government capital. The cascading political scandals created by his actions substantiate my contention that such communities lack cross-village norms of conflict avoidance. Here, the mayor was able to pursue his village’s political interests at the expense of broader social relations in a way that is far more difficult in historically centralized areas.

Arguably the most pernicious outcome for long-run development in historically acephalous areas that had seen substantial in-migration was disengagement from the state altogether. While elsewhere in the country many chiefs complained that all they had received from their local government was “one pen and one notebook” per child prior to the start of the school year or the occasional sack of rice, in some local governments numerous non-autochthonous village chiefs reported having been cut out of even these most basic deliveries. “The rural community is useless for us,” one village chief concluded.Footnote 58 These communities were also home to the only villages where multiple village chiefs stated that they had never met their mayor: “we only know the name” said one chief in Tambacounda.Footnote 59

Interviewees in historically centralized areas of the country indicated that in-migration had left a more muted impact on local political discourse. I illustrate this with evidence from the former kingdom of Saloum. Although not the only precolonial state to see in-migration, Saloum arguably saw the most rapid influx of migrants in the first decades of colonialism via the navetanes, or seasonal migrant workers coming from the West African interior. While originally arriving as temporary migrant workers during the peanut harvest, many migrants eventually settled in the area permanently.Footnote 60 As discussed in Chapter 2, in-migrants to the Saloum are considered to have been integrated into existing social structures, in line with long-standing practices of fictive kinship in the region.Footnote 61 This accords with my own interviews. Despite the Saloum’s ethnic diversity, ethnicity was only mentioned by one village chief as a meaningful cleavage in the region. This is surprising given the fact that ethnic fractionalization (measured through a Herfindahl index) in the Saloum ranged between the high 30s and the 50s, reflecting more ethnic diversity than the national average of 63.8.Footnote 62 Because migrants were often integrated into existing villages, few villages in the zone are ethnically homogenous, which, as one subprefect posted to the region observed, meant that any attempts to mobilize ethnic or caste tensions would be hard-pressed to find support.Footnote 63

Still, it must be acknowledged that interviewees in historically centralized areas that had seen in-migration were more likely to report disharmony in local political life than those that had not. But while social and political tensions do appear to be heightened in these zones, social institutions were nonetheless involved to regulate the behavior of autochthons and in-migrants alike. Tensions in these zones were almost always qualified as being resolved in the end without escalating competition among villages. “They can have a big fight,” one village chief observed of the local councilors in his diverse local government in the Saloum, “but two days later you see them together again.”Footnote 64

While in-migration may attenuate the core properties of institutional congruence, therefore, it does not easily overturn these dynamics provided that dominant social institutions survived the colonial era. Institutional congruence can be eroded when the theory’s twin mechanisms weaken sufficiently to render social institutions incongruent with the boundaries of the local state, however. Take one subprefect’s characterization of local political life in the territory of the precolonial state of Boundou, which had seen significant depopulation in the late 1800s. The kingdom’s territory had over time seen significant new settlement, most notably from many in-migrants from present-day Guinea. This challenged the ability of Boundou’s remaining descendants to claim the political power they believed themselves entitled to. Many of these elites were indignant that local government projects went to the newer migrant villages, a complaint voiced with particular acuity toward those of Guinean-descent, despite the fact that they were co-ethnics and that many of the villages in question were much larger and had clear objective need. The old elites whose grandparents had lived under the Boundou were committed to the idea that they deserve priority by virtue of their historical claims in the region. The result, the local subprefect bemoaned, was that sociological factors such as village age and caste became bound up in understandings of deservingness, creating divisive politics that pervaded all local development initiatives.Footnote 65 Despite the persistence of a shared identity rooted in the precolonial past as well as tight social networks among Boundou’s descendants, in-migration had diluted the density of these identities and networks, meaning that the local state was not imbued with the sense of collective purpose that defines congruent areas.

Religious Conversion

If in-migration risks proliferating group identities and social networks, what happens when the defining base of a group identity fundamentally changes? This is a possible outcome of mass religious conversion. Indeed, the early 1900s saw widespread conversion following the expansion of Sufi Muslim brotherhoods, most notably with the rise of the Mouride or Tidjane Brotherhoods, and far less frequently, with the arrival of Catholic missionaries. Yet even in the face of these new forms of religious practice, my interviews and survey data do not suggest that conversion fundamentally altered social ties or replaced locally hegemonic identities. In contrast, in many areas, social networks and shared identities transcended religious identities, suggesting that religious conversion did not fundamentally upset or alter local cross-village social institutions. One Catholic mayor in a majority Muslim local government in Thies spoke openly of his status as a religious minority. “At first,” he recounted, “I had to work to make inroads with the local marabouts, but now we attend each other’s religious festivals. We have the same population, their followers are my constituency, and we both work for local development.”Footnote 66

There is one notable situation that generates an exception. In communities where powerful religious guides become actively involved in local politics, either by running for office themselves or by putting in place candidates who are widely understood to be their proxies, the establishment of a distinct form of political hierarchy despite ostensibly competitive elections obviates the ability of social institutions to coordinate local action because the religious guide himself dictates (or attempts to dictate) local governance. This decidedly less democratic dynamic is illustrated in two local communities surveyed in 2013.Footnote 67

In Louga Region’s Darou Mousty Arrondissement, four out of seven rural communities are run by powerful maraboutic families that descend from Cheikh Amadou Bemba, the founder and spiritual leader of the Mouride Brotherhood. Since the capital villages of all of these communities were founded by Bemba’s descendants during the colonial era, these families have begun claiming their “right” to run their local governments. I surveyed one of these local governments where a prominent marabout had run for and been elected mayor in 2002. “As mayor, I am more respected before the Senegalese administration than if I was just a marabout” he explained, “so I decided that things would go better here if I was mayor as well.” He went on to describe his talibes, or religious followers, as his political base (they “sweep the way for me”), noting that his dual mandates uniquely positioned him to provide things to the community.Footnote 68 To a large degree, his statement is correct. The local government had seen significant improvements in the time since he took office.Footnote 69 While only two villages had potable water in 2002, for example, 95 percent had it by 2013.

Though in the territory of Cayor, in this case, the presence of a religious hierarchy in local governance circumvented preexisting social ties as the marabout’s religious, social, and now political authority subjected the local government less to shared social institutions than to the marabout-mayor’s own vision. To local residents, this was seen as less autocratic in practice than it may first appear to many readers. More than 95 percent of local government citizens adhered to the marabout and described this as a natural elision of authority. Still, not everyone approved. The only village chief interviewed in the local government who was not the mayor’s follower, for example, claimed that Peulh villages such as his own were left to themselves even though they had inhabited the area long before the arrival of the Mourides.Footnote 70

For followers however, the local government was doing good work. One councilor defined himself as a “councilor of the marabout,” having been unknowingly enrolled on the electoral lists by the marabout.Footnote 71 Indeed, 38 percent of councilors on the 2002–2009 council and 22 percent in 2009–2014 were from the chef-lieu, which, home to only 11 percent of the commune’s population, was the marabout’s religious base. In such cases, therefore, social institutions do little to shape local governance because alternative structures dominate.

Elsewhere, prominent religious leaders had less uniform adherence, generating what we might characterize as a distinct form of institutional incongruence. I illustrate this with a local government near the Gambian border whose capital village was also home to an influential Mouride marabout. The chef-lieu had been founded around the Second World War by a descendant of the Mbacke family in Touba, much later than the rest of the villages in the area who largely dated their foundation to the era of the precolonial state of Rip. Approximately 60 percent of the population were followers of the Tidjane Brotherhood, meaning that the marabout’s followers – both local converts as well as those who had in-migrated with his grandfather – were concentrated in the local government capital village.

As in the first example, the marabout’s influence on local politics was striking. The marabout regularly made party electoral lists himself, resulting in the local government capital receiving a disproportionate number of council seats. “The autonomy of the [council’s] decisions is not always assured, especially in the management of community goods,” a 2003 planning document notes, and the mayor “fails to make the distinction between himself as talibe and President [mayor].” This was no longer the case in 2013, when the previous mayor, who had served two terms, had been replaced with a more dynamic individual with a background in local development. The new mayor claimed a good working relationship with the marabout, but was not personally a follower, citing his independence as a positive feature in his ability to make improvements in the local government.Footnote 72 Yet the capital village retained a disproportionate number of councilors (35 percent of the total compared to a population share of 18 percent) and it remained unusually well-doted in public goods.Footnote 73

This “notable favoritism” was commented on at length. One chief concluded that he could not appreciate decentralization because “we have the power of the marabout and this is a defeat for [the mayor].” Noting that many villagers were having trouble getting land titles delivered by the local government, he alleged that when the marabout asked on behalf of a follower, the process went fast, while for other villagers it remained painfully slow.Footnote 74 These same facts were evoked positively by those with ties to the marabout, one village chief who was a talibe and extended family member noted that “it is the marabout who matters here,” before adding negatively “even if the mayor is trying to change that.”Footnote 75

Both cases illustrate how the presence of a prominent marabout in a community can undermine the properties of institutional congruence when it prioritizes a distinct social identity and social network – adherence to the marabout. Still, this is the exception. The vast majority of local governments surveyed were Sufi-dominated and many were home to villages with influential religious leaders, yet congruence remained possible. What matters is whether those leaders are able to dominate the local government, at which point we see the influence of local social institutions inherited from the precolonial past undermined.

Elite Assessments of Local Government Performance

Taken together, the qualitative data presented above indicate that the politics of representation and redistribution in local governments is a function of (a) whether a local government’s boundaries are congruent with cross-village social institutions inherited from the precolonial past and, subsequently, (b) whether or not the area saw a diversification of social identities and networks due to in-migration in the colonial or postcolonial period. In the last section of this chapter, I turn to quantifiable components of the 2013 survey, using questions asked of all respondents to evaluate these patterns more systematically. I break respondents into three categories: first, those residing in local governments in historically centralized areas, which I expect to display properties of institutional congruence; second, those residing in historically acephalous areas where I expect incongruence; and finally those where in-migration generated or amplified incongruence.Footnote 76

Perceptions of Government Performance

I begin by evaluating individual perceptions of local government performance. Figure 4.3 shows the distribution of responses to two sets of questions designed to capture evaluations of the performance of the current local council. The histogram represents responses to the question, “in your opinion, is the local government here in [local government name] going in the right or the wrong direction?” The kernel density line laid over the histogram reflects an aggregated score of responses to a series of questions asking respondents to evaluate their local government’s efforts in specific issue areas, including primary education, health, clean water, bringing in new projects, finding financing, responding to citizen demands, facilitating participation in local government issues, and being equitable. For both, responses are more favorable as one moves to the left and they are broadly consistent across questions, though respondents in congruent local governments are more critical of their local governments when asked about specific issue areas.

Figure 4.3 Evaluations of local government performance

Collectively, respondents are cautiously encouraging their local governments, with very few respondents reporting that the government is doing “very good” or going “completely in the right direction.” Support is strongest in areas of high congruence, where 70 percent of respondents evaluate their local government positively. In contrast, attitudes are more bimodal in incongruent areas that have seen significant in-migration, following the patterns in the qualitative data. Here, 53 percent of respondents are positive while nearly 47 percent are negative. Areas of low congruence are slightly more even, but nearly 40 percent of respondents still view their local government’s performance poorly. Cumulatively, this shows that there is a 10–20 percent increase in negative evaluations in local governments that do not meet my definition of institutional congruence.

Of course, social desirability bias or respondents who are hesitant to critique friends and family members could drive the positive direction of evaluations. Yet this appears to not be the case. The upward bias in positive evaluations by family members is much stronger in areas of low congruence, where the correlation between having a family member in elected office and a positive evaluation is 0.181, compared to 0.023 for areas of high congruence, suggesting that in the latter case evaluations are less affected by social relations. I display this visually in Figure 4.4, which reproduces the bar charts in Figure 4.3, but distinguishes between responses by those with elected family members in their local government (dark gray) and those without (light gray). This means that any gap between dark and light gray bars represents bias for or against the local state by family members.

Figure 4.4 Evaluations of local government performance by family relation

In general, family members are more likely to report that their local government is going in the “right” direction. This bump is smaller in areas of high congruence compared to incongruent local governments, however, and it is only in areas characterized by low congruence that family members are more likely to say that things are going “completely right.” While family members are generally more positive, difference of means tests suggest that it is only in cases of low congruence that family members are statistically more likely to report a positive opinion.Footnote 77 To the extent that the histograms in Figure 4.3 are driven, at least in part, by a desire to positively evaluate personal relatives or friends, this bias is primarily found in incongruent local governments, further reinforcing the story emerging out of qualitative data that suggests strong in- and out-group dynamics in such communities.

Perceptions of Government Responsibilities

The quantitative data also suggest that respondents have distinct conceptualizations of the local state’s obligations vis-à-vis the citizenry.Footnote 78 I asked respondents to tell me what they thought the three central responsibilities of their local government were, coding responses into one of five categories. Some respondents discussed universalistic obligations: local government should provide universalistic benefits or policies for the entire community. For example, responses that the local government should “expand the healthcare network in the local government” or “provide security” fall into this category because they are indicative of an obligation to provide broad coverage. Conversely, an answer is particularistic if the answer implies that the local government should do something targeted to the respondent, for example, to “build a health hut in the village” or provide fertilizer, food relief, or other individualistic benefits. Third, some respondents indicated that the local government should solve problems between community members or otherwise act as a social regulator. It was also often suggested that local governments had a responsibility of representation. These answers suggested that the local council should represent the population’s interests to the central state and/or donors and to respond to their desires in a general sense (i.e. “listen to the population”). Finally, some respondents listed administrative responsibilities, such as providing état-civil papers and collecting local taxes.

These responses are visualized in Figure 4.5. Most respondents invoke universalistic roles, representing 50 percent of total answers across all three questions. Still, respondents in high-congruence local governments list universalistic obligations in more than 60 percent of their answers, compared to roughly 40 percent in incongruent local governments, a 20 percent difference. In areas of low congruence, by contrast, respondents were more likely to note particularistic benefits, though here the difference is less sharp at only 5–10 percentage points. Interestingly, 10 percent of answers in areas of low congruence following in-migration indicated that local governments should play a role as a social regulator, double the rate at which respondents indicated this category elsewhere.

Figure 4.5 Local government responsibilities (% responses)

Perceptions of Equality

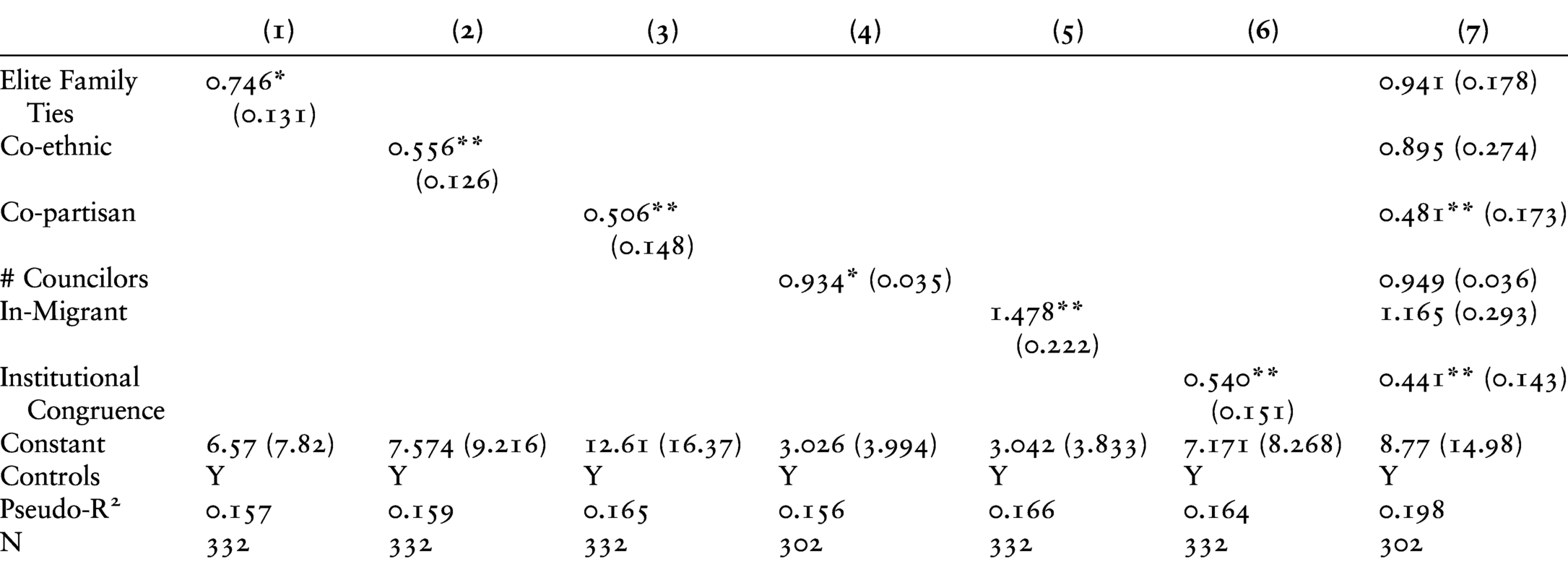

I thirdly evaluate whether or not perceptions of equality in treatment by the local government expressed in interviews can be systematically explained by the mechanisms highlighted in my theory. Table 4.2 reports odds ratios for a series of logit models that takes as the dependent variable a measure of whether or not a respondent made a reference to unequal treatment by their local government during the course of the interview. This is coded zero (no allegations of unequal treatment by the local government) or one (one or more comments that there is targeted inequality). Simply stating that the respondent’s village had not received anything was insufficient to be coded as an inequality claim, rather there had to be a specific statement that the local council played favorites, either generically or by naming which villages or communities were treated better or worse by the local government. Models include a series of controls for the logged population size of the respondent’s village, whether the respondent reported having received any training about local governance or development, their age, their reported meeting attendance during the previous year, and dummy variables if a respondent was a village chief or, similarly, a councilor.Footnote 79

Table 4.2 Odds ratios of perceived inequality in the local council

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elite Family Ties | 0.746* (0.131) | 0.941 (0.178) | |||||

| Co-ethnic | 0.556** (0.126) | 0.895 (0.274) | |||||

| Co-partisan | 0.506** (0.148) | 0.481** (0.173) | |||||

| # Councilors | 0.934* (0.035) | 0.949 (0.036) | |||||

| In-Migrant | 1.478** (0.222) | 1.165 (0.293) | |||||

| Institutional Congruence | 0.540** (0.151) | 0.441** (0.143) | |||||

| Constant | 6.57 (7.82) | 7.574 (9.216) | 12.61 (16.37) | 3.026 (3.994) | 3.042 (3.833) | 7.171 (8.268) | 8.77 (14.98) |

| Controls | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.157 | 0.159 | 0.165 | 0.156 | 0.166 | 0.164 | 0.198 |

| N | 332 | 332 | 332 | 302 | 332 | 332 | 302 |

* p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05. Results from logit models with robust, clustered standard errors by local government in parentheses. Control variables include logged population of respondent village, reported rural council meeting attendance in previous year, whether or not the respondent reported having received any training sessions about their role in the rural council and/or local development, their age, and dummy variables for councilors and village chiefs.

The results support the general contention that perceptions of inequality are impacted by network ties and the availability of different forms of identities in the local government. Being a co-partisan or co-ethnic as well as having family ties to other elites or living in a village with a number of councilors all reduce the likelihood that a respondent made an allegation of inequality. Having some form of a social tie to other elites therefore decreases the probability that a respondent views the local government as treating citizens unequally. Model 5 reports that in-migrants are more likely to allege bias. Finally, in line with my central theoretical predictions, respondents in congruent local governments, proxied here by exposure to precolonial statehood, are less likely to find their local governments unequal in Model 6, one of the few effects that remains significant in a pooled model (Model 7).

Assessing the Role of Local Government Resources

I conclude with a brief discussion of the possibility that the differences I have identified are driven by variable levels of local government resources. Respondent evaluations of their local governments may be influenced by the ability of their local elected officials to finance local projects, be it through donors, central government transfers, or local taxation. In reality, most donor financing is allocated to ministries or is channeled to local governments via state-sponsored programs; few local governments have individual relationships with donors, though some have established sister-city relationships with cities in France or Belgium. Local governments in historically stateless areas are actually more likely to report donor activity, with an average of 3.2 versus 2.4 active NGOs for congruent local governments, though the presence of bilateral partners (such as USAID) is comparable.Footnote 80 The local state relies most heavily on central government transfers, the most important of which is the Fonds de Dotation de la Decentralisation (FDD).Footnote 81 Average transfers between 2009 and 2012 are higher in historically centralized areas, at $23,927 versus $22,773, but the bias is in the opposite direction in per capita terms at $2.18 per capita in historically acephalous areas versus $1.59 in historically centralized areas.Footnote 82 I test the influence of average FDD transfers more robustly in the quantitative dataset presented in the next chapter.

Alternatively, if local governments that fall in the footprints of precolonial states are more efficient at collecting local taxes, respondents may be more enthusiastic about the local state as a function of nascent state-society bargains. Although the role of taxation has played a prominent role in studies of service delivery elsewhere in the world, a generally low tax incidence and a lack of publicly available data have limited investigations into this question in sub-Saharan Africa. National data on local tax revenue are not available, but informal data collected from local government secretaries suggest that areas of high congruence are more likely to collect local taxes, notably, the rural tax (la taxe rurale), which is set at about $2 per resident, with exemptions for the elderly, children under fourteen, women with more than eight children, active military service or disability. Historically centralized areas report an average collection rate of 56.3 percent of their tax rolls compared to only 16 percent elsewhere. In the survey data, there is no clear association between whether or not a village chief reports raising taxes and receiving goods, nor is there an association between rural communities that have higher tax collection rates and those that do not in terms of goods delivery. Certainly, if fully collected, the rural tax would facilitate government functioning. But even a 100 percent collection rate would only amount to around $4,000 in a medium-sized local government, far from enough to engage in significant development initiatives, such as the visible infrastructure projects I measure in the next chapter.

One way around the issue of missing fiscal data is to examine reported payments by citizens. I proxy compliance with tax payments by turning to data from Rounds 4 and 6 of the Afrobarometer which both asked respondents a series of questions about taxation. While respondents in local governments that fall within the territory of a precolonial state are more likely to report paying the rural tax at 64 versus 50 percent, attitudes about the legitimacy of taxation do not differ. Respondents in historically centralized areas are no more likely to report that a good citizen should pay taxes and that it was wrong to not pay taxes or to report that they had refused to pay taxes in the past year. This would suggest that while tax collection does appear to be higher in congruent local governments, this does not reflect differences in underlying attitudes about the legitimacy of tax collection on the part of the state.

In contrast, the ability of congruent local governments to raise more taxes more likely reflects their improved capacity to work with chiefs. Eighty-seven percent of chiefs in historically centralized areas report collecting the rural tax as opposed to only 47 percent elsewhere in the country. That this is a function of local government initiative is reflected in the fact that 42 percent of chiefs in historically centralized areas reported discussing collecting taxes with an elected official in the past year as opposed to an average of 22 percent elsewhere, further demonstrating that historically centralized areas see heightened informational flows between elites.

Conclusion

This chapter presented data from an original survey to identify distinct differences in how local elites describe their political worlds between areas of the country where I expect institutional congruence and those where I expect incongruence. In so doing, the chapter establishes an empirical baseline for my argument: respondents in areas of institutional congruence view democratic decentralization more favorably and are disproportionately more likely to cite the responsiveness and benefits of contact with their local governments as the reasons they appreciate the reforms. They also evaluate the work of their local government councils more positively, they view their local governments as responsible for delivering universalistic benefits, and they are less likely to upwardly bias their evaluations when they are related to elected officials.

This chapter has stressed the importance of how individuals talk about and conceptualize their local governments. The qualitative evidence supports the argument that experiences with local governance are influenced by shared narratives about a community’s past. Though narratives of political life are distinctly local, taking a comparative lens across local governments allows me to identify types despite the inherent specificity at play in each local government. At base, debates about local belonging and who has the right to speak for the community (and what community) remain a key defining feature in rural political dynamics. Who feels represented and who gains access to social services are contingent on how these claims structurally manifest themselves among local elites. Certainly, this chapter has confirmed the expectations of many that distributional politics in rural Africa are informed by ethnic, partisan, and other ascriptive political identities, but at best this explains only some cases. Elsewhere, the structural overlap between formal and informal social institutions aligns to produce what are seen as fairer and more responsive local administrations. Rather than dismissing local politics as inherently detrimental to decentralization reforms, therefore, I argue that we must look them squarely in the face or risk misunderstanding how local political practice generates new forms of inequality and exclusion.Footnote 83 How these different forms of local politics map onto actual delivery of public goods is explored in the next chapter.