Communities around the world possess norms that stipulate appropriate social comportment and acceptable ways to exercising political authority. Political scientists are increasingly interested in these dynamics, suggesting that governance may be improved by “harmonization” of traditional and legal forms of governance.Footnote 1 I join this broader research agenda by documenting how social institutions around conflict avoidance and principles of balance shape local governance in historically centralized areas of rural Senegal when they overlap with formal institutional boundaries. Because decentralization reforms have been put in place across West Africa, this raises the question of whether we see similar patterns elsewhere. Is there a robust effect of precolonial centralization on local development outcomes across the region? This chapter offers a tentative answer to this question by pairing an expanded coding of precolonial states across West Africa with data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) and public opinion data from the Afrobarometer survey. This allows me to estimate whether the location of precolonial states correlates with attitudes toward local governance and development outcomes across decentralized West Africa. Afrobarometer respondents in areas that were home to precolonial states report distinctly more positive attitudes about their local governments and democratic practice than their counterparts in historically acephalous zones. The DHS data shows that these same areas also see improvements in local development outcomes in line with both my expectations and the patterns I have documented in Senegal.

The second half of this chapter explores the argument’s theoretical generalizability by returning to the central question animating this book: why are some communities imbued with prosocial attitudes that help them improve their collective good while others are not? My evidence from Senegal suggests one answer can be found by studying how social institutions inherited from the precolonial past facilitate cooperation under decentralization when they overlap with the contours of the local state. But can the argument shed light on empirical phenomena that stray from the specifics of precolonial legacies or decentralization as an institutional reform? To answer this, I highlight how the two mechanisms animating my theory – shared social identification and dense network ties among elites – offer a flexible and generalizable framework for understanding variation in how distributive dilemmas are resolved. I draw on a wide range of research to illustrate the broad applicability of the mechanisms, identifying comparable dynamics at different levels of government and across varying cultural and institutional contexts. I conclude by outlining a series of scope conditions for the argument.

Legacies of Precolonial Statehood across West Africa

My focus on precolonial legacies contributes to a growing recognition that areas of Africa that were home to centralized precolonial organizations have better levels of contemporary development today by refining our understanding of why the precolonial past continues to shape the present. To do so, I have limited the historical treatment under study to look at Senegal’s microstate system in the centuries before French colonization. But is the argument specific to the legacies of precolonial states in Senegal alone? Though scholarship has shown that exposure to precolonial statehood generated continent-wide effects, I focus on the West African state systemFootnote 2, which stretched east to the edges of the Sokoto Caliphate in Nigeria, and south to the coastal states that were most directly touched by the Atlantic trade.Footnote 3 The majority of West African countries were home to a multitude of smaller precolonial polities. As a result, like Senegal, these cases offer unique subnational leverage on the independent variable. At the same time, though more variations on state form are found once we look beyond Senegal, key commonalities defined West Africa’s precolonial polities as lineage structures remained the basic sociopolitical institutions, for example, and leaders faced a common dilemma of how to rule dispersed populations.Footnote 4

Decentralization in West Africa

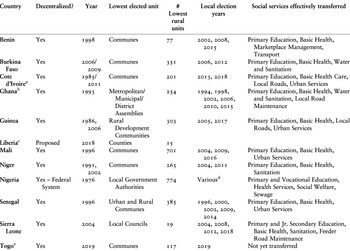

The last three decades have seen a wave of decentralization reforms sweep the African continent, often concurrent with broader processes of political liberalization. Some West African countries, like Ghana or Nigeria, have joined Senegal in expanding earlier decentralization efforts, while others, such as Sierra Leone or Burkina Faso, decentralized more recently in the 2000s. Table 8.1 offers a brief comparison of decentralization reforms in the West African states for which I have data, specifically among those surveyed in Round 6 of the Afrobarometer. These reforms varied in timing and form. Francophone countries have largely followed a similar model that hews closely to France’s own administrative structure: decentralization created urban and rural communes nested with either elected regions (e.g. Mali) or within deconcentrated departments (e.g. Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal).Footnote 5 In contrast, Anglophone countries display more variation, from fully democratically elected local governments in Sierra Leone to Nigeria’s Local Government Authorities (LGAs), where elections are held at the discretion of the state governor. As a result, only a quarter of Nigeria’s LGAs are run by an elected council with the rest administered by a caretaker committee.Footnote 6

Table 8.1 Decentralization in West African countries surveyed in Afrobarometer Round 6

| Country | Decentralized? | Year | Lowest elected unit | # Lowest rural units | Local election years | Social services effectively transferred |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | Yes | 1998 | Communes | 77 | 2002, 2008, 2015 | Primary Education, Basic Health, Marketplace Management, Transport |

| Burkina Faso | Yes | 2006/2009 | Communes | 351 | 2006, 2012 | Primary Education, Basic Health, Water and Sanitation |

| Cote d’Ivoirea | Yes | 1985/2011 | Communes | 201 | 2013, 2018 | Primary Education, Basic Health Care, Local Roads, Urban Services |

| Ghanab | Yes | 1993 | Metropolitan/Municipal/District Assemblies | 254 | 1994, 1998, 2002, 2006, 2010, 2015 | Primary Education, Basic Health, Water and Sanitation, Local Road Maintenance |

| Guinea | Yes | 1986, 2006 | Rural Development Communities | 303 | 2005, 2017 | Primary Education, Basic Health, Local Roads, Urban Services |

| Liberiac | Proposed | 2018 | Counties | 15 | ||

| Mali | Yes | 1996 | Communes | 701 | 2004, 2009, 2016 | Primary Education, Basic Health, Urban Services |

| Niger | Yes | 1991, 2002 | Communes | 265 | 2004, 2011 | Primary Education, Basic Health, Sanitation |

| Nigeria | Yes – Federal System | 1976 | Local Government Authorities | 774 | Variousd | Primary and Vocational Education, Health Services, Social Welfare, Sewage |

| Senegal | Yes | 1996 | Urban and Rural Communes | 385 | 1996, 2000, 2002, 2009, 2014 | Primary Education, Basic Health, Urban Services |

| Sierra Leone | Yes | 2004 | Local Councils | 19 | 2004, 2008, 2012, 2018 | Primary and Jr. Secondary Education, Basic Health, Sanitation, Feeder Road Maintenance |

| Togoe | Yes | 2019 | Communes | 117 | 2019 | Not yet transferred |

a Cote d’Ivoire began its decentralization reforms in the 1980s, devolving authority over the construction of primary education facilities, local market and bus station maintenance, etc. in 1985, but economic crises in the early 1990s led the state to retrench from local communes (Crook Reference Crook and Manor1998, 143).

b Ghana’s District Assemblies are headed by the District Chief Executive, who is appointed by the President. The District Assembly is 70 percent elected by adult suffrage in nonpartisan elections, with the remaining 30 percent appointed.

c Liberian President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf launched a National Policy on Decentralization in 2012, but the legal framework for decentralization, the Local Government Act, was not signed until September 2018.

d LGA elections are held at the discretion of the state governor, with the majority of LGAs run under a “caretaker committee” appointed by the Governor.

e Togo originally enacted decentralization laws in 1998, but these remained unimplemented. Urban and Urban communes held elections in 1987, but all subnational units have been administered by the central-state-appointed officials in the interim (Breuer Reference Breuer, Blomenkemper, Kliesch, Salzer, Schädler, Schweinfurth and Virchow2017).

Table 8.1 also reveals wide diversity in the depth of reform, as many governments have announced decentralization schemes but stopped short of full implementation. Burkina Faso established decentralized administrative principles in its 1991 constitution, but did not hold founding elections until 2006.Footnote 7 Likewise, while decentralization was first discussed in Benin’s National Conference in 1989, the law took ten years to complete and local elections were only held in 2002.Footnote 8 Still elsewhere, decentralization reforms are only now being enacted (and weakly so at that) after years of discussion. Togo has long debated and passed decentralization laws, for example, but has yet to meaningfully transfer authority to the local level and only held its first local elections in June 2019.Footnote 9 Similarly, Guinea’s local government code, decreed in 2006, has yet to be published. Liberia included decentralization reforms in its postwar reconstruction plan but has proceeded slowly since the return to civilian rule. For example, the County Development Fund was introduced in 2006, transferring funds to the lowest administrative unit of the county, but a draft Local Government Act was only circulated in 2013. Due to the 2014–2015 Ebola Crisis, the process was delayed, with the final decentralization laws signed in September of 2018.

In most cases, urban communes have benefited more meaningfully from these reforms than their rural counterparts. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the latter have also seen substantial interference with their borders. In Cote d’Ivoire, former President Gbagbo attempted to increase the number of communes nearly fivefold, though the process was aborted in 2012; today the country has 197 municipalities.Footnote 10 Similarly, Ghana decentralized with 110 District Assemblies in 1993, but the number of districts more than doubled to 254 by 2019.Footnote 11 An inverse version of these dynamics is found in Mali, where the decision to involve local populations in commune creation following the establishment of a decentralized territorial administration in its 1992 constitution led to a proliferating set of demands for increasingly small administrative units as the government sought to find compromises between bottom-up preferences and top-down needs for administrative efficiency. In the end, the country created 701 communes, nearly double the original goal.Footnote 12 At the other extreme, however, Niger simply decentralized by granting more power to preexisting cantons, themselves inherited from the colonial era.Footnote 13

Local governments across the region have been charged with a broadly similar set of responsibilities, though in all cases, state transfers are insufficient and local tax collection weak. Unlike in Senegal, responsibility over basic service provision was promised from the start for most countries in the region, even if they were only bestowed gradually. Mali’s local governments obtained minimal authority over primary education, basic health, sporting and cultural events, and a handful of other policy areas in 1996, but these were not transferred until 2002.Footnote 14 Similarly, local governments in Burkina Faso are officially tasked with eleven policy areas but at the end of the initial three-year timeline set forth by the state, only four of these had been devolved.Footnote 15 In many cases, authority is decentralized but remains effectively concurrent; state and local governments alike are active in basic health and primary education in countries like Nigeria. Note, moreover, that in some cases this authority is circumscribed: Burkina Faso and Guinea remain under the tutelle of the central state, meaning that all decisions must be approved by higher-level officials.

We can draw two tentative conclusions about decentralization in West Africa. First, decentralization remains an incomplete reform, at times blending responsibility in unclear ways. Nevertheless, even though local governments have yet to be granted the full authority promised to them by the center, in all cases they have begun exercising local authority in some domains. Second, most countries have held at least two rounds of local elections. Even if these reforms may be “incomplete” in the eyes of proponents, the combination of these two factors has been sufficient to create new arenas of political competition that are tied to questions of local solidarities, historical settlement patterns, and local distributional politics as I document in the section “Evidence of Institutional Congruence Following Decentralization.”

Evidence from the DHS

If broad trends in decentralization are similar, as shown in Figure 8.1, then the fact that West Africa was home to a series of interconnected microstate systems means that the properties for institutional congruence should be available throughout the region. I begin by examining whether or not there are systematic differences in local gains in public goods access between areas that were home to precolonial states and those that were not. Put otherwise, is there evidence that precolonial statehood impacts the contemporary politics of redistribution similarly across West Africa?

Figure 8.1 Difference of means – DHS data

To do so, I test changes in social service access with data from the DHS. The DHS surveys are collected around the world, surveying a nationally representative sample about household demographics, health, and nutrition. I compare reported access to locally delivered social services in the early 1990s – before democratic decentralization was enacted – with data collected post-decentralization, between 2010 and 2012. Because some countries in the sample have only made tentative steps toward decentralization by the early 2010s, notably Togo and Liberia, I drop them from the analysis.Footnote 16 As has been noted by others, DHS data may best be thought of as estimating the flow of goods through individuals, rather than the actual physical location of services themselves.Footnote 17 I limit the sample to rural respondents, where the assumption that individuals are most likely to obtain access to such flows, like education, at facilities that are in close proximity, is most plausible.

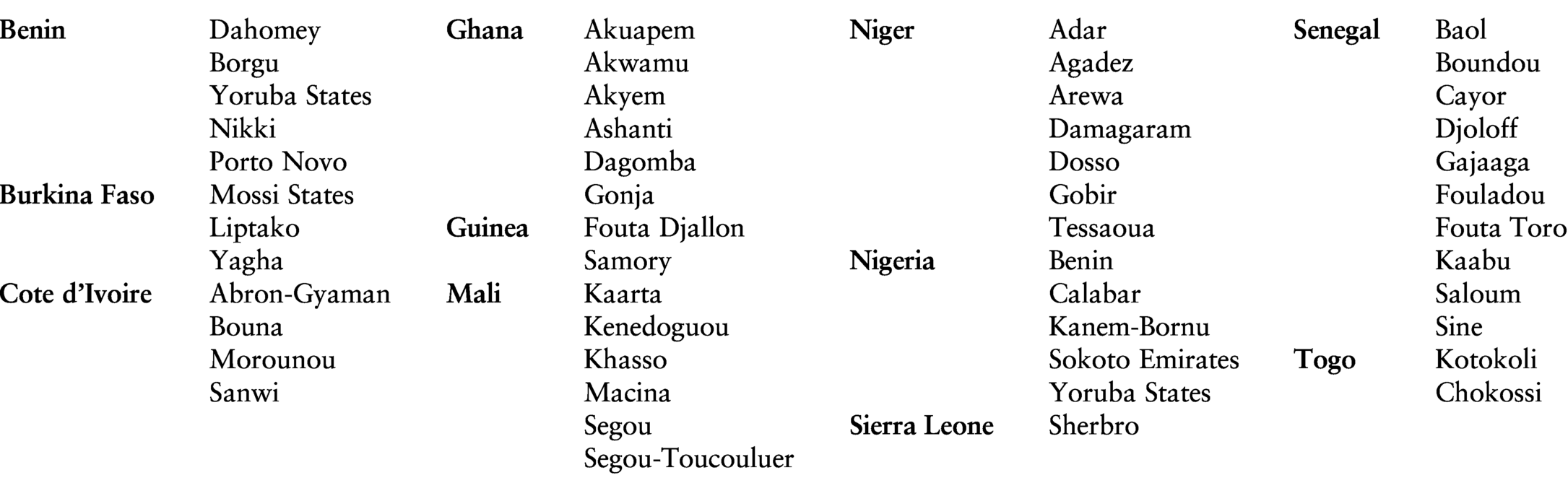

In order to estimate the impact of precolonial statehood on reported access to basic social services in the DHS, I have to match sampled households to the location of precolonial states. I follow a similar procedure as that described in Chapter 5 to expand my coding of precolonial statehood for the precolonial polities listed in Table 8.2, all of which meet my criteria for statehood. DHS respondents are coded as falling within the territory of a precolonial state if their geolocation is within a 20-kilometer buffer of the capital of these states.

Table 8.2 West Africa’s precolonial states in the nineteenth century

| Benin | Dahomey | Ghana | Akuapem | Niger | Adar | Senegal | Baol |

| Borgu | Akwamu | Agadez | Boundou | ||||

| Yoruba States | Akyem | Arewa | Cayor | ||||

| Nikki | Ashanti | Damagaram | Djoloff | ||||

| Porto Novo | Dagomba | Dosso | Gajaaga | ||||

| Burkina Faso | Mossi States | Gonja | Gobir | Fouladou | |||

| Liptako | Guinea | Fouta Djallon | Tessaoua | Fouta Toro | |||

| Yagha | Samory | Nigeria | Benin | Kaabu | |||

| Cote d’Ivoire | Abron-Gyaman | Mali | Kaarta | Calabar | Saloum | ||

| Bouna | Kenedoguou | Kanem-Bornu | Sine | ||||

| Morounou | Khasso | Sokoto Emirates | Togo | Kotokoli | |||

| Sanwi | Macina | Yoruba States | Chokossi | ||||

| Segou | Sierra Leone | Sherbro | |||||

| Segou-Toucouluer |

To avoid imposing assumptions on the form of the data as well as “bad” or post-treatment controls, I present the results of a series of simple difference of means tests in Figure 8.1.Footnote 18 Since most local governments in West Africa are charged with building and maintaining primary education and basic health facilities, I examine measures for both. For education, I look at what percent of children under the age of ten in each surveyed household was enrolled in school at the time of the interview. I also examine the average levels of education of household members. Similar to the strategy adopted in Chapter 7, I limit the sample to household members under ten years of age to ensure that I am only measuring those who could plausibly have benefited from new infrastructure built following decentralization reforms. Data from the early 1990s are truncated similarly for comparison. To measure improvements in healthcare access, I calculate the percent of all children born to surveyed women in the past five years that were delivered in a public health clinic as well as each woman’s reported number of antenatal visits for her most recent birth. As with education, these data are limited to births that would have occurred post-decentralization.Footnote 19

Figure 8.1 presents the results of difference of means tests for these variables. For all four outcomes, the data suggest that there have been disproportionate improvements in areas that were home to precolonial states.Footnote 20 Prior to decentralization, households in historically centralized areas had a lower percent of household members enrolled in school than historically acephalous areas, but this relationship flips completely by the early 2010s. Likewise, these areas have nearly closed the gap in the average education level of household members fewer than ten. Nearly identical trends are found in maternal health: women in historically acephalous zones were more likely to deliver in a clinic in the 1990s, but the bias has flipped by the early 2010s. And while women in historically acephalous zones do have more antenatal visits, this gap has narrowed considerably since decentralization.Footnote 21 These results mirror the trends reported in the DHS data for Senegal in Chapter 7.

Finally, I examine whether or not this could be driven by a wealth effect; areas home to precolonial states have been argued to have accumulated higher levels of private wealth, as has been argued by Bandyopadhyay and Green (Reference Bandyopadhyay and Green2016), which would suggest that the effect of precolonial statehood does not run via the local state, but more simply because families in these areas accumulated more wealth early on. There is no statistically significant difference in the DHS’s household possessions index in either time period. We do see an improvement in access to piped water, however. Households surveyed in areas that were home to precolonial states were statistically less likely to have clean water prior to decentralization, but more likely to have access afterward. Because water is not decentralized everywhere in the region, note that the results for these estimates come from a reduced sample of countries that have devolved water and/or sanitation. The DHS results parallel neatly those presented in earlier chapters for Senegal: private wealth does not seem to positively correlate with precolonial statehood, but access to public goods that are delivered by local governments in the majority of decentralized West African countries does appear to be higher – and improving at different rates – in areas that were home to precolonial states.

Figure 8.1 provides support for my claim that the empirical pattern I document in Senegal has broader empirical traction in the region. But these figures risk conflating the diversity of experiences that West African states have had with decentralization reforms discussed above. A key property of my theory is that institutional congruence embeds decision-making within local social relations, meaning that local governments that see substantial top-down interference may not see congruence despite ostensible decentralization. For example, the fact that many – though not all – of Nigeria’s LGAs are run by caretaker committee may suggest that other redistributive logics prevail because decision-making is removed from the social institutions that I claim alter local elite behavior.

To address this possibility, I replicate the results presented in Figure 8.2 but distinguish between local governments that enjoy full legal autonomy and those that see substantial top-down interference. The latter includes Burkina Faso and Guinea, which remain under the tutelle of the central state, as well as Ghana, where the District Chief Executive (akin to a mayor) is appointed by the President. I code Nigeria’s LGAs as being subject to top-down influence when less than 50 percent of a state’s LGAs were ruled by elected local councils for the majority of time between 2008 and 2013, the date of the last DHS round in my sample, as coded by Kyburz (Reference Kyburz2018).

Figure 8.2 Difference of means – DHS data, accounting for variation in level of decentralization

Figure 8.2 displays the average change in the same metrics between historically centralized and acephalous sample clusters, breaking down the difference between decentralized units that have substantial (or “full”) local authority over local redistribution and those with “partial” authority that sees central state interference. In general, historically centralized areas appear to perform better than historically acephalous zones regardless of the degree of local autonomy. Nonetheless, recent development gains are greater for respondents who have seen more significant decentralization of authority to the local level than those that have seen decentralization with considerable central state oversight. This indicates a strong role for local governance as a driver of local development when there is significant spatial overlap with longer-run histories of cooperation.

Evidence from Attitudinal Data

Next, I turn to geocoded public opinion data from the Afrobarometer public opinion surveys to examine whether rural citizens evaluate their local governments differently in areas that were home to precolonial states. Using data from Round 6, which covers all eight countries of French West Africa, absent Mauritania, and key Anglophone states in the region, including Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone, I match respondents’ villages to the expanded coding of precolonial states introduced in the previous section.

Employing Afrobarometer data allows me to assess the general plausibility that something about governance in areas that were home to precolonial states differs from historically stateless zones. Although the data are necessarily imprecise as to the mechanisms I derive from the Senegalese case, Round 6 offers a number of questions that offer indirect assessments of the theory’s broad contours. These fall into two broad categories. First, the Afrobarometer asks respondents a suite of questions about how they evaluate their local government’s work and, second, the survey asks a number of questions that I use to estimate respondents’ general sense of political satisfaction.

The first five estimates presented in Panel A of Figure 8.3 suggest that by and large respondents who fall in areas that were home to precolonial states are more positive about their local government. Specifically, respondents in historically centralized areas are more likely to think that their local councilor listens to them, to trust their local elected officials, to positively evaluate their council’s work, and to report that it is easy to obtain an identity card, a service frequently (though not exclusively) performed by local governments. There is no difference, however, in the reported likelihood of having contacted one’s local elected official in the past year.

Figure 8.3 Difference in means – Afrobarometer data: (a) attitudinal measures and (b) wealth measures

In an effort to distinguish between what is driven by a local versus a national effect, I also look for differences in how respondents evaluate the President’s performance. As reported in Panel A, there is no difference in evaluations of the President between historically centralized and historically stateless zones, suggesting – though of course not establishing definitively – that respondents are not conflating their satisfaction with local and central state officials. General political satisfaction is proxied with the last two estimates in Panel A. Respondents in areas that were home to precolonial states report being more satisfied with democracy and are less likely to believe that political parties create conflict. Results are consistent when subset by gender and education, and whether or not one is an ethnic minority within their survey cluster. The findings fall broadly in line with the expectations derived from my qualitative data from rural Senegal.

Because Afrobarometer enumerators ask questions about household wealth while also making their own observations about the quality of a respondent’s dwelling, I am again able to test for differences in local development. Specifically, I look at whether there is a difference in access to locally supplied public goods or those provided by the central state and, finally, I test the robustness of the wealth findings from the DHS data reported in Figure 8.1. I measure locally supplied public goods by looking at reported access to water and sanitation (latrines). Because water and sanitation are only devolved competences in some countries in my sample, I only estimate this for countries that have officially transferred responsibility over water and/or sanitation to the local state (as reported in Table 8.1). I measure central-state-provided goods by whether or not a respondent has reliable access to electricity (if at all). Lastly, I estimate the effect of precolonial centralization on household wealth through a standard wealth index of household possessions, an index of household need, the type of residence a respondent lives in (ranging from temporary structure to a permanent house), and the material of their residence’s roof (ranging from thatch or grass to a permanent roof).Footnote 22

These results, seen in Panel B, give no evidence of a private wealth effect, in line with the DHS data. If anything, households in areas that were home to precolonial states seem to fare worse. While there is no difference in household possessions or conversely household needs, West African respondents in historically centralized zones have poorer roof materials and live in less permanent or more traditional residential structures. Historically centralized areas do not seem to benefit more from goods delivered by the central state. In fact, these areas are less likely to have reliable electricity access than historically stateless areas, mirroring the results of the placebo tests presented in Chapter 5. Still, Panel B does indicate that West African respondents residing in areas that were home to a precolonial state have better access to clean water in countries where local governments are charged with their delivery, though there is no effect of broader sanitation efforts, as seen in the null effect for latrine access.

Of course, these findings are only suggestive. The positive bias toward the local state in historically centralized areas could simply reflect more deference to elites rather than actual performance. Nonetheless, Figure 8.3 supports my core contention that there is something systematically different about areas home to precolonial states in the region and that the positive effects of precolonial statehood appear to be limited to locally provided public goods.Footnote 23

Evidence of Institutional Congruence Following Decentralization

Statistical analysis of data from the DHS and Afrobarometer suggests that broadly similar outcomes are emerging in decentralized West Africa, as individuals in historically centralized areas reporting greater satisfaction with the local state and seeing better on average improvements in local development outcomes. This finds traction in case studies of community-specific experiences with decentralization in the countries under study. Reviewing these case studies provides support for three broad elements of my theory: decentralization reforms have elided with local social status hierarchies, this has generated new political arenas for local cooperation (or conflict) akin to a two-level game, and, finally, that local governance has been imbued with social institutions that shape how elites approach the local state.

I begin with the most studied of these questions. The advent of decentralization across West Africa produced a “resurgence of tradition,” as the establishment of new arenas of power produced novel avenues to local authority and local resources.Footnote 24 The creation of local governments – even when fiscal and distributional capacities have been slow to arrive – has paradoxically both reconfigured and reinforced local legitimacies. This is particularly true for traditional authorities who have (re)emerged as powerful figures in local politics in an institutional “layering” of power.Footnote 25 Many chiefs, for example, have seen decentralization as an opportunity to reassert their authority.Footnote 26

In the short term, this raised alarm among proponents of decentralization, who viewed the implication of traditional authorities as evidence of elite capture. Over time, however, this has become less clear. While local notables typically won in the first round of elections, for example, subsequent local elections have seen more competition as local populations came to appreciate the role that the local state would play in their lives. Yet even as candidates who are seen as dynamic and resourceful have made gains, this has not eliminated the role of local social status and being a non-notable or in-migrant remains a potent means to discredit another’s candidacy.Footnote 27 As a consequence, longer-term understandings of local moral communities and not ideological or even partisan dynamics animate local governance in the region as local political dynamics and even vote choice are informed by local social alliances and conflicts. In this way, “discourses of locality, of autochthony, of state authority, of religious belonging, of frontier …” bring local elites and their social networks into the realm of decentralized governance.Footnote 28

Even as interest in the local state has grown and diversified, therefore, customary holders of local social status remain prominent in the local state. Echoing my findings from Senegal, case study evidence documents a tendency of local politicians to claim their right to local social status – including seats in the local council – as a function of their descent from village founders, reflecting the deeply held view that preexisting sociopolitical hierarchies have a particular claim to these new political fora following a logic that “a good leader should be a home grown person.”Footnote 29 Within Niger’s local governments, politics remains closely tied to local solidarities; “The canton chief is first and foremost the representative of a lineage … The president of the cereal bank management committee is first and foremost a man of the neighborhood …” Olivier de Sardan (Reference Olivier de Sardan2009, 45) writes. Candidates draw on broad social networks for political support as they enter the arena of the local state, with lineage structures and historical ties between families serving as important a role as partisanship.Footnote 30 This involved not only family ties, but also friendship and allied villages, suggesting similar dynamics to those I observe in Senegal: shared histories of settlement and cohabitation shape the networks that local elites rely on in local governance.

By generating a new focal point of authority, decentralization has raised thorny questions about who should govern at the local level both within and across villages as local administrative units across the region pool numerous villages together into new jurisdictions.Footnote 31 To this end, local histories of settlement have created either disparate or compatible claims to the right to govern following decentralization, reflecting how “discourses of the local” remain a core dynamic within West African political culture.Footnote 32 Existing work has most often studied this in the framework of autochthony claims. Béridogo (Reference Béridogo1998) and Hahonou (Reference Hahonou2002) observe how autochthony and party politics interact to generate divisive local politics in historically acephalous areas of Mali and Niger in a way that echoes the dynamics I illustrate in Chapter 4.

Evidence from Mali’s experiences with decentralization, perhaps the most studied case in the region, shows how these discourses interact with cross-village dilemmas raised the creation of rural communes.Footnote 33 Mali’s process of commune creation was slowed down considerably as villages refused membership in prospective local governments because the commune’s capital was proposed in the villages of non-autochthons, because they would be numerically dominated by non-co-ethnics or those who were casted or because the boundaries grouped villages with contentious historical relations, to name but a few of the most commonly cited examples.Footnote 34 In southern Mali “the new territorial collectivities concentrate a diversity of village and inter-village interests,” rendering the commune an “‘arena’ of inter-village dynamics, … subject to local social rules that can be identified and which must be taken into account.”Footnote 35

Here a second key component of my theory finds a parallel: decentralization generates a dynamic akin to a two-level game. Across West Africa, decentralization simultaneously offered new venues for village-based elites to expand their authority while also challenging the ability of any village hierarchy to capture the local state, shifting the focus of local political contestation to control of the commune itself.Footnote 36 Importantly, also embedded within the Malian case is a story of inherited cross-village solidarities that can generate institutional congruence. During the country’s consultative process of commune creation, “social solidarity between villages soon became the driving force behind the new communes.”Footnote 37 Local Bamana elite in Mali’s Tinkolé commune, which falls in the territory of the precolonial state of Segou, stressed the past as an organizing principle of local social organization, for example, with “its non-respect constituting a deviation quite detrimental to all life of society.”Footnote 38

Though not himself focused on the legacies of precolonial kingdoms, we find the clearest evidence of the role of precolonial identities in Fay’s (Reference Fay2000, 126–127) study of Mali’s Tenenkou Circle, which lies in the former territory of the precolonial kingdom of Macina. Fay documents how local communities recreated precolonial-era janyeeli, or provinces, when choosing the boundaries of their new communes, citing one local elite: “we are the same … we have the same navel … the same breasts … we marry each other …” At once, the quote invokes the two animating mechanisms behind my theory: a highly localized identity, or category, rooted in the past combined with dense social ties, or network, creates a sense of community solidarity and purpose. This language mirrors that heard in rural Senegal. The local development plan for Senegalese local government of Orkadiere, for example, describes the local government’s many villages as sharing “an umbilical cord” with the chef-lieu, making the local government capital “a place of meetings, convergence, and services whose legitimacy is tied to history.”Footnote 39

Across the West African Sahel therefore, decentralization has generated a “traditional resurgence” as elites, who lay their claim to social status in the past, have come to embrace new roles following democratic decentralization. These dynamics take place across villages as much as within them, with the presence or absence of cross-village social networks shaping local solidarities. This raises the potential for conflict induced by the two-level game dynamics inherent in decentralization, but social institutions – when present across villages – tie elites together into shared expectations about social comportment in the public sphere. Though the form and content of social institutions likely vary from that seen in Senegal, other authors note the presence of powerful social norms tied to local identities and social networks. Olivier de Sardan (Reference Olivier de Sardan2009), for example, emphasizes norms of consensus and conflict avoidance as dominant social institutions in rural Niger, and scholarship from across the Sahel belt highlights how locally understood norms of behavior shape local governance under decentralization.Footnote 40 In Mali’s Kiban Commune, which fell in the territory of the precolonial state of Segou and the subsequent Umarian state afterward, Koné and Hagberg (Reference Koné, Hagberg, Hagberg, Kibora and Korling2019, 56) document how conflict in the commune was “silent,” as the four dominant lineages in the commune moved to protect local social relations in the face of threats. In Burkina Faso’s Dori Region, home to hierarchical chieftaincies in the precolonial era, understandings of poverty and mutual aid are “based in a strong moral notion of a glorious past of communal solidarity.”Footnote 41 Because the citizens of Dori expect politicians to follow community values of solidarity, religious adherence, and respect for the collective good, politicians favor traditional values over pure political calculations in local governance.Footnote 42

Though these case studies – almost all conducted by anthropologists in specific villages or local governments – lose a subnational comparative frame, we see key elements of my theory throughout. Local governments interact with place and lineage-based social hierarchies and they pool villages that must negotiate over new resources delivered by a new jurisdictional body. These negotiations can be contentious, but they can also be cooperative. When case study evidence suggests the latter, scholars tend to report the key moving parts of my theory: these communities tend to have local elites with network ties across villages or lineages that support shared understandings of community solidarity and consensus.

Assessing the Mechanisms beyond Africa

The central argument of this book is that Senegal’s precolonial states have left enduring legacies at the grassroots that are repurposed and redeployed by local communities under democratic decentralization. In the previous section, I demonstrated that there appears to be broad empirical traction for these dynamics across decentralized West Africa. But the question remains whether the argument offers insight for Comparative Politics more broadly. In this section, I discuss how the two jointly reinforcing mechanisms animating my theory – shared social identities and dense social networks – offer analytic leverage around the world. In this way, I show how the book’s core theoretical claim, that distributional politics are shaped by the spatial overlap between the formal bounds of decision-making and localized social dynamics, can extend to a broader set of contexts, even if we relax the nature of the antecedent cause.

I support this proposition by focusing on three recent literatures that have accumulated evidence of processes that parallel those described in the preceding chapters. Collectively, they echo the assertion of Wibbels (Reference Wibbels, Rodden and Wibbels2019, 15–16) that scholars keep an eye to “local social orders,” or the social, economic, and political networks that animate any given community.

Evidence from Native American Reservations

Pioneered most clearly in a series of papers by Cornell and Kalt (Reference Cornell and Kalt1995, Reference Cornell and Kalt2000), the first example comes from Native American reservations in the United States, where the authors find better economic development today when resident tribes have a history of shared governance. Cornell and Kalt refer to this as the existence of an “extra-constitutional agreement.” Where reservations see a “match” between the constitutional rules of resident tribes and their pre-reservation systems of government, tribal governments perform better because this “match” generates agreement on how power should be legitimately exercised.Footnote 43 Cornell and Kalt articulate mechanisms not far from my own: institutions that are perceived as legitimate trigger “the private rewards and penalties of the ‘social sentiments,’ with the social networks that individuals are embedded within inhibiting free-riding and defection vis-a-vis those institutions.”Footnote 44 Cultural norms, they conclude, serve as “glue” between formal and informal institutions.Footnote 45

Dippel (Reference Dippel2014) makes a similar argument. He finds that even where residents are otherwise homogenous, reservations that pool different bands see worse economic outcomes today compared to those with a history of cohabitation. Two things in Dippel’s argument make for an important parallel. First, the effect is strongest for outcomes pertaining to local governance; forced coexistence, he documents, increases internal conflict and corruption. Second, Dippel documents that this difference was minimal until the late 1980s when tribal governments gained more authority. Much like Senegal’s decentralization reforms, the effect of cross-band cohabitation (or not) appears most strongly once decision-making arrives at the local level. Thus, Dippel concludes “historically determined differences in social organization can persist relatively unnoticed for long periods, before they have large and relatively sudden effects on economic outcomes when they interact with big shocks.”Footnote 46

This book effectively inverts Dippel’s explanation. Where he suggests that social cleavages persist over the long run, “even when they are not tied to easily observable characteristics like ethnicity,” I argue that historical sources of social cohesion can persist with equal force.Footnote 47 Evidence from Native American reservations therefore indicates that the creation of new administrative boundaries from on high paired with a later devolution of authority can generate striking divergences, even though, like Senegal, these communities were subject to brutal colonization by an external force. In both, the effect is driven by specifically local political dynamics that result from the spatial overlap between social institutions and the bounds of decision-making.

Evidence from China’s Local Governments

The evidence presented in this book further resembles that presented by Tsai (Reference Tsai2007) on local government officials in China. Tsai argues that local government officials invest more in public services when they are held accountable through informal solidary institutions that both embed officials within the village community and encompass the village as a whole. The presence of such informal institutions, namely lineage associations and temples, generates varying degrees of spatial overlap between solidary institutions and the village as an administrative unit. When this overlap is high, solidary institutions are able to hold officials accountable, even under authoritarianism, by virtue of their dense social networks and promotion of cooperative behavior. In Tsai’s (Reference Tsai2007, 253) own words, “when group boundaries overlap with the administrative boundaries of local government and the group embeds local officials in its activities and institutions … officials are more likely to carry out their duties and perform well.”

Tsai’s argument has been followed by a number of similar studies of village governance in rural China.Footnote 48 Most prominently, Xu and Yao (Reference Xu and Yao2015) find that villages home to larger clans, which often have deep historical roots in a village, have on average higher public goods expenditure. This suggests that clans themselves generate feelings of obligation to the lineage and Xu and Yao explicitly identify identity and network mechanisms. The fact that individuals so strongly identify with their clans facilitates the enforcement of local norms. By downplaying the relative role of elected officials, Xu and Yao suggest that villages that overlap with what amounts to local social institutions – proxied in their study by clan size – perform better. Tsai herself observes that the general logic has older precedents: Skinner (Reference Skinner1965) wrote more than fifty years ago that communes created during the Mao era were hampered because they explicitly did not correspond to preexisting social networks, or, in other words, because they were intentionally incongruent.

A central insight from work on China is that social dynamics influence local development outcomes even under autocracy. Two implications follow for my purposes: first, it suggests that the dynamics I outline can emerge in nondemocratic settings. Second, it reveals that institutional congruence can apply downward to the village level when this is the relevant administrative unit. While my argument stipulates a role for cross-village networks, central for Tsai and others is the encompassing property of local informal institutions relative to the scale of the community in question. This likewise serves to circulate information about reputations, enabling social sanctioning and leading actors to internalize the value of group behavioral expectations.

Evidence from India

Lastly, more diffuse evidence from India indicates that variation in welfare investments is similarly shaped by different degrees of subnational territorial attachment. Singh (Reference Singh2015a, Reference Singh2015b) compares the performance of Indian states and documents how states that have strong subnational identities outperform those that lack such shared identities. Much like local attachment to identities rooted in the precolonial past in rural Senegal, when Indian elites and citizens share a sense of subnational identity, they perceive themselves as having shared obligations to promote the “common good.” Critically, this can cross other markers of diversity.Footnote 49 Ultimately, Singh (Reference Singh2015a, 5) draws a similar conclusion: states are more likely to invest in citizen welfare when there is “a match between the political-administrative unit that has jurisdiction over social policy and the locus of collective identification.”

At a lower administrative level, Anath Pur (Reference Anath Pur2007, 416) finds that informal local governance institutions within villages that maintain social norms and preserve local custom can play a positive, synergistic role within India’s local governments or gram panchayat, precisely because these informal local associations “nest neatly,” almost never crossing gram panchayat boundaries. This “vertical dovetailing” between formal and informal institutions, she concludes, is what makes their relationship productive for local citizens. As with the China case, this shapes how informal local government institutions have persisted within villages as Indian villages have long histories and have largely remained unchanged as territorial units.Footnote 50

Unlike my own argument or that of Anath Pur, Singh’s argument differs in the origins of such collective identification. I document deeply rooted, historical identities in Senegal, but Singh chronicles how politicians in some Indian states actively nurtured the development of subnational identities for political ends, eventually finding themselves constrained by these very subnationalisms, obligating them to meet citizens’ demands for further welfare investments. This suggests – in stark contrast to my own empirical evidence or that emerging from rural China or Native American Reservations – that powerful collective identities can be forged for new subnational units even in a shorter timeframe.

Summarizing the Insights from Comparative Politics

Together, these studies indicate that a degree of “elective affinity” – or congruence between informal and formal institutions – can determine the success of institutional reforms.Footnote 51 What does this diverse set of findings mean for the two mechanisms identified in my own research? In general, scholars emphasize the role of shared identities more than the role of networks. To this end, there is abundant evidence that individuals invoke historical forms of group membership when pursuing political goals, even when these place-specific forms of group membership do not necessarily parallel objective measures of diversity. The most obvious parallel in the African context is Laitin’s (Reference Laitin1986) study of the role of ancestral cities among the Yoruba. Laitin emphasizes that ancestral cities remain the hegemonic identity for the Yoruba despite the presence of other politicized identities, notably religion. The continued identification with hometowns among the Yoruba is in no small part maintained by the fact that hometowns are, Trager (Reference Trager2001, 239) writes, “a place where one is known and where one’s reputation is important.” While for Singh the role of subnational identities is critical to her theory, for others, such as Tsai or Dippel, the role of identities is implied, for example, lineage associations matter because, as clarified in Xu and Yao (Reference Xu and Yao2015), family lineages are a central identity for rural Chinese.

Networks are often less explicitly emphasized. This reflects the relative lack of attention among political scientists to what Tilly (Reference Tilly2006) has called “relational mechanisms.” For Tilly, the relations that individuals maintain with one another are not divorceable from the value of their social and political identities; identities thus reside within relations. Political scientists are not unaware of this – indeed key arguments often rest on assumptions about relations, say within ethnic groups – but we have only recently begun examining this empirically.Footnote 52 Yet, my findings indicate that these are inseparable; identities give meaning to networks while, in reverse, networks incentivize abiding by the behavior and norms that constitute the identity in the first place. Indeed, this book’s argument is predicated on their interaction.

Scope Conditions of the Argument

When are social institutions inherited from the past, such as those persisting from the precolonial era in West Africa, capable of generating institutional congruence? I articulate three scope conditions to my argument below.

Though I have focused on the legacies of precolonial statehood, there is abundant evidence that historical, place-specific identities are being resurrected across the African continent, ranging from autochthony claims to other forms of historical claim-making, such as the mobilization around colonial-era districts in debates about administrative redistricting in Nigeria.Footnote 53 This may indicate that the social requisites for congruence are plentiful. But not all social identities or social networks are capable of generating congruence even if they are otherwise “old.” The first scope stipulates that there must be a clear mechanism of persistence to carry the social institutions imbued by the past into the present. The existence of a potential antecedent alone is insufficient to engender congruence.

This was illustrated in the case study of Koumpentoum, presented in Chapter 6: a positive value on the antecedent condition (here, exposure to the precolonial state of Niani) did not generate congruence because there was no mechanism of persistence to reproduce social institutions over time. In this case, residents of the Niani out-migrated in the mid-nineteenth century, meaning that the local government’s current residents were not exposed to what cross-village social institutions existed during that era. This can help explain why despite an endless array of potential historical legacies, only some exert themselves powerfully in the present. Institutions are political because they are inherently hierarchical, ordering allocative preferences even if they simultaneously enable cooperation. The consequence is that for institutions to persist, they must be valorized and actively reproduced over time.

In rural Senegal, I locate the mechanism of reproduction in village-based social hierarchies. These hierarchies simultaneously validate the social status of individual elites, bolstering their claims to local voice as well as material goods, at the same time they necessitate that elites acknowledge the equivalent claims made by others in their communities. A lineage claiming the village chieftaincy by tracing their genealogy to the era of a precolonial state, for example, has an incentive to affirm shared identities of descent from that kingdom as a legitimate claim to community membership. In this way, shared narratives of descent from a precolonial polity are collectively reproduced by elites over time. We similarly see a clear logic of persistence in other work as well. Tsai’s (Reference Tsai2007) solidary groups, for example, have persisted in rural China because they have long offered a means to the moral standing citizens desire, meaning that they were not intentionally deployed to embed local officials. Returning to Senegal, social institutions rooted in the precolonial past continue to matter because they continue to structure access to meaningful resources, such as reciprocal obligations between families and neighbors, access to land or marriage markets, by virtue of their ties to village social hierarchies.

This further means that anything that troubles the social reproduction of local social hierarchies should overturn the effects I document. Though to date elites have proven quite capable of maintaining traditional forms of social status in the face of expanding and changing political opportunities, other longer-term dynamics could undermine these networks and, by extensions, the impact of the social institutions that elite networks carry with them on local political life. This is perhaps evidenced most clearly in my own empirical material in the presence of prominent religious authorities within local communities, who can pivot elites away from social institutions rooted in village-based social hierarchies or redefine the nature of these social hierarchies entirely around new social institutions. Alternatively, we can imagine that resettlement schemes, such as those seen in Tanzania or Ethiopia, would similarly disrupt cross-village networks and local status hierarchies by nullifying the value of “first-comer” status to a zone.

The interplay between formal governance institutions and informal social ones that animate my theory emerges from a second scope condition. If formal institutional rules reorient elites’ focus outward and upward, rather than inward toward their local social networks, we should expect the effects of congruence to attenuate. My discussion in the section “Assessing the Mechanisms beyond Africa” suggested that the twin mechanisms underpinning my theory may emerge across a wide range of institutional forms with positive effects for development outcomes. This may be when congruence is initiated unintentionally from the top-down, as was seen in Senegal, or when the geography of cross-village social institutions altered the contours of the decentralized state itself, as in Mali, effectively rendering local government performance endogenous to the existence of robust social institutions on the eve of reform.Footnote 54 But while the argument is not necessarily tied to regime type or the nature of institutional reform, it does demand that elites view their most consequential network ties as being at the same level over which they exert authority. Put otherwise, there must be a relational component between decision-makers that subjects them to local social institutions. If they are buffered by these by top-down interference of some kind, we should be skeptical of the ability of social institutions to shape actor behavior.

This is exemplified by thinking through two alternative network structures induced by different formal institutions. Because social networks serve as a means for motivating and sanctioning behavior toward group goals, when elite networks orient actors toward the central state via the threat of sanction from above, we should expect local social dynamics and institutions to be less influential on elite behavior. For example, as described in Woldense Reference Woldense2018. As was shown in Figure 8.3, when local governance remains subject to central government interference, the effects of congruence are moderated. Alternatively, we can imagine cases where institutional design limits the ability of elites to sanction each other from below. A recent example of this argument is found in the Sierra Leonean case, where decentralization reforms have been captured by Paramount Chiefs exactly when they are most closely tied to elected officials. Inverse to my own findings, local public service delivery in Sierra Leone appears to improve when there is more conflict between chiefs and elected councilors. Conversely, service quality declines when there is more collusion.Footnote 55 Yet, as documented by Acemoglu, Reed et al. (Reference Acemoglu, Reed and Robinson2014), Sierra Leone’s Paramount Chieftaincies were created by the British, disembedding them from local social norms and altering social networks between elites. Because these institutions were invented, in other words, they are not subject to older norms of elite cooperation that lay at the base of precolonial political order.

Individuals may possess shared identities and shared social networks, therefore, but when aspects of the formal institutional environment alter the standing of some local social network members, decision-makers can become insulated from local behavioral expectations. When elites have substantial social autonomy in this way, they have more freedom to engage in opportunistic behavior. As a result, formal institutional design must enable the network mechanism to carry social institutions into the calculi of local elites when they meet in the local state.

Norms “do not float freely in space,” Collins (Reference Collins2004, 31–32) writes, “but are crystallized in institutions. The denser the environment they pervade, the thicker they tend to be.” Like Collins, I advance an argument about the potency of social norms in circumscribed communities. Here looms the specter of a third potential scope condition: is the argument limited in scale?

The most obvious answer comes from Englebert (Reference Englebert2002b) who articulates a similar logic, though distinct causal process, to explain cross-national variation in postcolonial state performance. Englebert argues that postcolonial leaders faced different incentives at independence as a function of the degree of violence that their postcolonial boundaries did to precolonial authority structures. Where postcolonial and precolonial boundaries have low congruence, bureaucrats are insufficiently loyal to the state and more likely to engage in neopatrimonial relations. The relative overlap between the postcolonial Botswanan state and traditional Tswana authority has similarly been advanced by Robinson and Parsons (Reference Robinson and Neil Parsons2006) as a means to explain the relative success of postcolonial Botswana. In a different tradition, a large body of work has found that strong national-level identities are the basis upon which the modern European and East Asian Welfare states are built.Footnote 56 Alesina et al. (Reference Alesina, Easterly and Matuszeski2011) globalize this view, finding that political and economic outcomes are worse in cases where states are “artificial,” those whose borders do not match those preferred by its citizen, around the world.

In the intermediate spaces between the local contexts where I draw my own empirical content and the central state itself, however, lies a tricky middle ground. Few precolonial states had the geographic fortunes of the Tswana, who were numerically dominant in the postcolonial Botswanan state and the question of how identities scale subnationally within the polity appears critical elsewhere. Indeed, we might very well expect that countries like Senegal, home to microstate systems, should see precolonial identities play out differently in the postcolonial state than in cases like Uganda or Ghana, where the precolonial states of Buganda and the Ashante Confederacy presented more formidable political obstacles to postcolonial leaders. As argued by Acemoglu, Chaves et al. (Reference Acemoglu, Chaves, Osafo-Kwaako and Robinson2014), it was the credible threat to postcolonial elite posed by these kingdoms that led postcolonial leaders to focus on capturing domestic political compliance. This led to more reliance on the military in the short term, but both countries have more state capacity today than many of their neighbors where an immediate postcolonial threat from a rival sense of legitimacy was less pressing. When social institutions – and the political groups they encompass – are neither nationally congruent nor small enough to be unthreatening to the central government actors, therefore, we may see more interventionist approaches on the part of the state in ways that alter the potential for congruence.

The argument is therefore most likely apt on a local level. Though we can see above how the identity mechanism may scale upward, say as the emergence of a national identity shifts one’s sense of obligations from the local to the national level, the network mechanism should scale more difficultly. After all, it is at a localized level that both networks and identities are most ripe for collective action.Footnote 57 This does not mean that the argument is inherently limited in scale, however.Footnote 58 At higher levels of aggregation, such as Singh’s study of Indian states, territorially larger than the units under study here, networks are still expected to matter, but the nature of elite ties is likely more variable and more vulnerable to pressures from outside the network.

Conclusion

In this final empirical chapter, I have demonstrated that the argument I develop in rural Senegal offers analytic leverage on attitudinal and development outcomes across West Africa. I find that Afrobarometer respondents residing in areas that were home to precolonial states hold more positive attitudes toward democracy and the local state than their counterparts in historically acephalous zones and, in turn, that respondents to the Afrobarometer and DHS surveys in historically centralized areas have seen disproportionate gains in locally provided public goods under decentralization. While I take this as evidence for the argument’s broad generalizability, I note that these empirical regularities may be bounded and merit further analysis.

This chapter has secondly suggested that the two mechanisms that underpin my theory of institutional congruence shed light on a more universal pattern of how subnational distributive dilemmas are resolved. The contours of institutional congruence as a theoretical framework find parallels across the world and at different levels of government. This is consequential because by opening up what the content of social institutions may be, I offer a framework for unifying an otherwise dispersed literature on the effects of social identities and social institutions on access to basic welfare. While many scholars have – and indeed are increasingly – recognizing the interaction between social norms and formal institutions, I put forward a means for us to theorize when these interactions are more or less likely to induce the positive outcomes that we know they are capable of generating, but which we so often see them fail to do.