Virginia growers are heirs – not always literally, of course – to an unbroken history of tobacco cultivation that links them to the origins of the plantation and chattel slavery in North America and, by extension, to the larger consequences of both for world history.

An Amerindian crop – transplanted to Europe, transplanted back to America, grown by an English-Algonquian couple, and transplanted to Africa – miraculously justifies whites’ position in Zimbabwe. With such aptitude for meanings and materials, surely whites could make their home in both VirginiasFootnote 1 or anywhere in Africa.

The Agrarian Myth and Tobacco Culture in Colonial History

The colony of Southern Rhodesia was founded in 1890 by a private commercial concern, the British South Africa Company (BSAC). The basis for colonial occupation was the hope of finding the second Rand and the belief in the existence of an African Eldorado. In 1892, after visiting the country, Lord Randolph Churchill judged the environment hostile to farming and concluded that agriculture on a large scale, except for the feeding of a large mining population, would be a ‘ruinous enterprise’.Footnote 2 However, many of the mineral prospectors who sought the elusive motherlode were frustrated – searching in vain for the vein of bright metal. When gold disappointed them, several turned their hands to cultivating the soils surrounding the reefs. Here they found a different kind of gold: the potential to grow the rich golden leaf of tobacco.

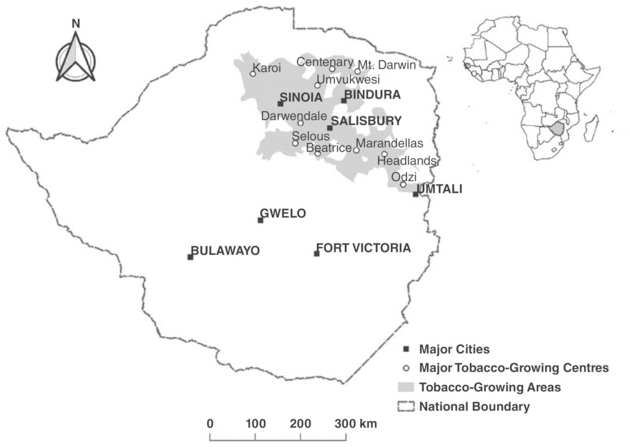

These pioneer white settler farmers carved out farms in the sand veld virgin lands in the northern and north-eastern parts of the colony (see map on Figure 1.1) – an area that was later to assume the appellation ‘tobacco belt’.Footnote 3 Between 1894 and 1945, tobacco growing expanded exponentially to become a key pillar of the colonial economy contributing a third to export earnings and becoming the colony’s major export. However, the development and expansion of the settler colonial tobacco economy in Southern Rhodesia was not a simple, triumphalist, whiggish story of success. It came at the cost of an environmental onslaught and social struggles whose import must be contextualised within the broader global narratives. Tobacco cultivation constructed new social relations, produced and reproduced new environments and ecological landscapes in Southern Rhodesia. To reconstruct a more nuanced and multi-directional narrative on the interaction between the tobacco crop, the colonial pioneer farmers and the environment this chapter draws on a global historiography and explores comparative trajectories of tobacco’s early colonial history in the New World where the crop first became a global commercial commodity. The chapter engages with global histories, especially North American environmental history scholarship on early agricultural settlements, pioneer tobacco planters and the African environmental history historiography on the 1930s stimulated by the Dust Bowl storms and the Great Depression to locate Southern Rhodesia in a broader global history of tobacco farming ecosystems and global conservation discourses.Footnote 4

Figure 1.1 Map of Southern Rhodesia showing the tobacco belt.

In explaining the rise of tobacco cultivation in Southern Rhodesia and the tobacco economy, most local historians have looked at it as a neutral and even benign interaction of ‘man’ and ‘nature’ out of which white settler communities pioneered new productive patterns that promoted expansion, development and growth.Footnote 5 Indeed, the historiographic traditions of the earlier works on Rhodesian tobacco centred more on a glorified and romanticised ‘virgin lands’ tradition of the role of private capital and the enterprise and ingenuity of individual (white, male) farmers captured in the glow of public relations and promotional literature.Footnote 6 This literature ignored the exploitation of huge pieces of ‘virgin lands’ on a larger scale than before, the despoliation of fragile ecologies in the sand veld areas of the country, the extraction of forestry resources of the colony, and the linked social violence meted on African labour in the tobacco farms.

The study of pioneer settler colonial agricultural communities is extensive, conceptually challenging and controversial.Footnote 7 The early literature from the 1920s pioneered by Frederick Jackson Turner followed an upbeat, cheerful model that glorified pioneer agricultural communities and entrenched the ‘mythical’ vision of settler farmers devoted to ploughing virgin lands, putting in crops and transforming vast untamed colonial lands into Edenic gardens.Footnote 8 This historiography was challenged by revisionist historians in the 1950s who criticised the frontier hypothesis as an ‘agrarian myth’.Footnote 9 During the 1970s, this critical scholarly tradition gained greater traction and Turner was attacked by new environmental histories for not acknowledging the sinister side of the westward expansion.Footnote 10 Richard Hofstadter and others criticised Turner’s romantic western history for ignoring the shameful side of westward expansion, particularly the land speculations, the arrogance of American expansionism and the stories of the conquered indigenous populations.Footnote 11

Within these debates about the nature of pioneer agrarian frontiers, the expansion of tobacco farming settlements in the Americas from the end of the seventeenth century attracted plenty of scrutiny from environmental historians. Tobacco had been cultivated by the ‘native’ Americans long before the so-called discovery of the Americas by European explorers.Footnote 12 Indeed, the genus NicotianaFootnote 13 is believed to have its roots in South America where it grew naturally and was cultivated by ‘native’ Indians who used it for religious, spiritual and pharmaceutical purposes.Footnote 14 The European settlers displaced indigenous groups in the growing of the crop, commercialised it and transformed it from an Amerindian into a new ‘European commodity’.Footnote 15 From the Americas, the crop spread to and proliferated in other parts of the world – finding its way to Africa, India, the Mediterranean and becoming grafted into supposedly ‘indigenous agrarian ecologies’.Footnote 16 From the 1600s, tobacco had become an important crop for European merchants and political elites following the establishment of tobacco settlements in the American colonies.Footnote 17

Tobacco became more than a crop. It acculturated itself into an integral part of the colonial culture defining a range of values, labour systems and cultural practices including the calendar itself.Footnote 18 In the tobacco states life was organised around idiosyncratic rituals of making the crop from the nursery, to the lands, harvesting and curing.Footnote 19 Tobacco dominated and regulated colonial life more than any other agricultural activity.Footnote 20 The plant not only affected perceptions of time, but also other dimensions of the colonial culture, as both human and material geography were affected by the crop as it determined settlements and social relations through its cultivationFootnote 21 The growing of tobacco controlled the frontier environment as farmers moved into new virgin lands as soon as their soils showed exhaustion, clearing forest and extending the boundaries of the colony.Footnote 22 Most colonial historians have been critical of the agricultural practices of the tobacco farmers, the plantation economy, slavery and row crop cultivation.Footnote 23 In Chesapeake, where colonial land was opened by tobacco farmers between 1780 and 1840, erosion of tobacco fields as a result of soil exhaustion led to the sedimentation and clogging of streams.Footnote 24

Although it is not clear at what point tobacco was introduced to Africa, it is generally accepted that by the end of the seventeenth century the crop had penetrated much of the continent as a result of Portuguese, French, English and Arabic trade networks.Footnote 25 The Dutch settlers at the Cape in what later became South Africa planted tobacco in 1652 and the crop became popular amongst the Khoisan who traded it in exchange with their labour, cattle and land.Footnote 26 The Yao of Malawi and Mozambique accumulated wealth by supplying coastal traders with tobacco during the 1600s, and traders in the Niger delta disposed of tobacco at higher prices during the nineteenth century.Footnote 27 By 1800, with the establishment of colonial settlements in Africa, tobacco became a key crop for white settler colonial agricultural development in eastern and southern Africa. Therefore, the history of tobacco production is a global narrative that cuts across different cultures and epochs. The heritage of the crop across history has etched itself on the environment, human relations and the human physical body in ways that evoke the need to write stories that reflect the trans-nationality of the crop across time. Indeed, Richard Foltz challenged historians to expand their gaze and write transcontinental environmental histories.Footnote 28 To this extent, the early story of tobacco in Southern Rhodesia must be linked with the global history of the crop and its role in the construction of new social relations and environmental landscapes.

Early Settler Tobacco Farmers, Land Settlement and the Environment in Southern Rhodesia, 1893–1928

Tobacco production in Southern Rhodesia began long before the settlement of Europeans in the country where it is believed to have been brought by the Portuguese traders in the fifteenth century.Footnote 29 Early accounts point out that in most parts of Mashonaland and Matabeleland Africans cultivated patches of tobacco in their gardens for their own consumption, trade and the payment of tribute.Footnote 30 The most popular of these pre-colonial tobacco producers were the Shangwe people who had a thriving tobacco industry that the colonialists found and later undermined.Footnote 31 The exact date for the beginning of white cultivation is unclear, but what is evident is that by 1893, a few settler farmers had begun experimenting with commercial production on very small plots.Footnote 32 The BSAC Reports from 1889 to 1892 note that tobacco cultivation had promising prospects in the colony.Footnote 33

These earliest white settler tobacco farmers were experimenting with the ‘indigenous’ tobacco varieties largely of the genus Nicotiana Rustica.Footnote 34 However, in 1898 the settler government distributed to white farmers, fifteen varieties of Nicotiana Tabacum seed bought from America. The following year the Secretary Department of Agriculture reported that the excellent samples of tobacco harvested proved the suitability of the climate and soils for tobacco farming.Footnote 35 By 1902, the crop was being cultivated in most parts of the colony by Europeans, with the newly established Department of Agriculture reporting that 11, 000 lbs were exported to Kimberley in South Africa.Footnote 36 The 1903 Customs Agreement between the Union of South Africa and Southern Rhodesia under which animal products and crops were guaranteed duty free exchange provided a ready market for Rhodesian tobacco.Footnote 37 However, during much of these early days not much farming was done, and land was rather held for speculative purposes as the hunger for gold drew many of the farmers away from their farms as they sought quick fortunes in gold mining.Footnote 38

In 1903, the tobacco-growing industry was slowly getting established with about 100 white settler farmers cultivating the crop.Footnote 39 Earl Grey, the director of the BSAC, was so enthusiastic about this development that he hired George Odlum, an agriculturalist from Canada as the government tobacco expert and sent him to the United States of America (USA) for a year to study tobacco culture.Footnote 40 Upon his return, the BSAC endeavoured to stimulate production and company shareholders began to actively support the cultivation of tobacco for export to build and sustain a stable white agricultural community.Footnote 41 In 1904, 147,355 lbs of tobacco were harvested.Footnote 42 In 1905, the figure increased to 500,000 lbs.Footnote 43 The growth of tobacco as an export crop had significant ramifications for the land settlement plans of the BSAC. The sand veld that consisted of some of the poorest soils in the colony suddenly found a unique appeal. The company took advantage of this opportunity and hyperbolically pointed to its shareholders that the entire colony of Southern Rhodesia was favourable to the cultivation of tobacco.Footnote 44 In 1904, Odlum emphasised that tobacco was a crop that was peculiarly adapted for a new country such as Southern Rhodesia because of an abundance of cheap virgin soils and a plentiful supply of labour.Footnote 45 In 1905, the BSAC tobacco expert retorted: ‘land is cheap in Rhodesia; if you want more tobacco, plant a bigger acreage’.Footnote 46 As a result of this propaganda, flue-cured tobacco barns sprang up all over the countryside and good crops were grown and prices of 1.s to 1.s.6d per lb were obtainable.Footnote 47

The cultivation of tobacco on a more extensive scale as an export crop was yoked in tandem with the colony’s general agricultural outlook that began to improve from around 1907 following the visit of the company’s directors. That year, the directors declared that the outlook for agriculture in the colony was auspicious.Footnote 48 In 1908, the ‘White Agricultural Policy’ was launched.Footnote 49 For much of these early years from the launch of the White Agricultural Policy the BSAC pursued a policy of encouraging the introduction of large capital to open up the farms as these were envisaged as possessing the capacity to more rapidly develop the resources of the colony than the smaller individual enterprises.Footnote 50 Thus much of the earliest tobacco farming was done by big companies such as Holt and Holt Limited which was granted 30,000 acres of land in 1905 for tobacco production.Footnote 51 Another company formed for the purposes of growing tobacco the Hunyani Estates had a capital of £100,000 and 30,000 acres of land but only managed to produce 4,000 lbs in 1905.Footnote 52

The first tobacco sales in Southern Rhodesia were conducted by private treaty and growers received lucrative prices such that profits per acre were as high as £25.Footnote 53 The main buyers were the United Tobacco Company (UTC) in South Africa. In 1910, the first sale by auction was conducted in Salisbury coinciding with the organisation of the growers into the Tobacco Planters Association. This later became the Rhodesia Tobacco Planter’s Co-operative Society in 1913 whose objective was to find new markets outside of the traditional Union market. In 1914, however, the UTC could not buy much stock of Rhodesian tobacco because of overproduction and a glut which the South African market could not absorb. The result was the 1914 tobacco crash that bankrupted many tobacco growers who abandoned their farms.Footnote 54 More significantly, the tobacco crash eliminated the dominance of big companies in tobacco production and paved the way for the rise of small tobacco farmers.Footnote 55

So, after the 1914 crash most tobacco companies were bankrupted and the BSAC came to view the small farmer as the pillar upon which the future foundation of the tobacco industry depended.Footnote 56 Clements and Harben argue that it was these small farmers after the 1914 crash who permanently settled on the land and changed the face of the landscape as the frontier of tobacco settlements spread further and advanced into new areas.Footnote 57 Clements and Harben glorify these settler tobacco farmers as they ‘tamed the land so today, unlike the bulk of Rhodesia, it reflects in its landscape more often the work of man than the savage exuberance or dull monotony which characterise Central Africa’.Footnote 58 Commenting on the early development of tobacco farming in Southern Rhodesia the Tobacco Industry Council also exhorted the passion shown by the early pioneers:

The distinguishing feature of the early tobacco pioneer was his boundless enthusiasm and energy; with no experience to draw on, little by the way of capital, new growers and their labourers hacked lands out of the Rhodesian bush, and with a simple faith put all they had into tobacco crops.Footnote 59

These pioneering whiggish ‘virgin land’ narratives were constructed around what J. M. Coetzee called ‘dream topographies’ – fantasies of viewing colonised land as empty and unoccupied spaces.Footnote 60 This reinforced the notion of the conquered territory as a pristine wilderness in which native subjects and environmental resources were raw materials for the expansion of settler agricultural communities. These ‘dream topologies’ and virgin land fantasies constituted a Jeffersonian ideology of progressive white yeomanry turning a ‘howling wilderness’ into a garden of settler nationhood in which white settlers and the land become unified and the ‘native’ is rendered invisible.Footnote 61 Thus, attracted by cheap land and the lure of the golden tobacco crop, immigrants from Britain, Europe and South Africa had flocked to the colony and bought huge chunks of land. But to cultivate the most fertile soils, these pioneers had to do heavy stumping and clearing of indigenous trees.Footnote 62 In time, the countryside began to change as the new immigrants altered the very landscape. Native woodlands and grass veld suffered. Veld fires to burn new areas of the sand veld became common, and at the meeting of the directors in 1907 the issue was brought up.Footnote 63 An editorial of the Rhodesian Agricultural Journal in 1908 complained that maize and tobacco farmers were burning grass to clear their land and, in the process, many forests were lost. The editorial mused: ‘what farmer would think of planting mealies or tobacco in soils devoid of humus, yet every year we take away by fire the only means our grasslands have of gaining any’.Footnote 64

In the American colonies the expansion of tobacco farming during pioneer days had created severe ecological problems. Tobacco being a soil nutrients’ draining crop lowered the yielding capacity of the soil, and with scarce capital for fertilisers all the burden was thrown on the soils immediately available.Footnote 65 As a result tobacco farming as practised during the early colonial days in America was an itinerant business. Newcomers to the colony would always petition to move from public lands to which they had been assigned on the plea that their farms were depleted for further tobacco crops.Footnote 66 In the Madison County of North Carolina the boom in flue-cured tobacco during the 1870s and 1880s witnessed huge waves of tobacco cultivation that encroached on forested mountain tops and ridges.Footnote 67 The timbered sandy land was stumped and cropped with tobacco for a few years until the virgin fertility was exhausted by crop removal, cultivation and erosion.Footnote 68 Farmers cleared new lands on the precipitous steep slopes, and the cutting of fuelwood caused deforestation. The countryside was heavily gullied as a result.Footnote 69 The practice of burning the ground for seed bed preparation to kill insects and their larvae was also so common that during late winter the tobacco belt presented ‘a hazy appearance from the great number of glowing fires’ that consumed so much firewood and was so wasteful that there was a scarcity of wood fuel.Footnote 70

Similar problems abounded in Southern Rhodesia because of the activities of the pioneer tobacco farmers. In 1910, the company government of Southern Rhodesia had hired the services of Mr. J. Simms, a forest officer of experience from South Africa to visit Rhodesia and assess the condition of its natural forests. His report pointed out the haphazard and wasteful ways in which forestry resources were being exploited by farmers and miners.Footnote 71 He noted that most of Rhodesia’s forests were poorly stocked and many of the trees damaged by fires caused by farmers burning early grass and not controlling the fire, with disastrous effects on the soil and the deterioration of forests.Footnote 72 He added:

The legitimate cutting of timber for fuel, and the clearing of lands suitable for agriculture is necessary and desirable, but the felling of trees as practised in this country is so wasteful and indiscriminate that it can only be classified as destructive.Footnote 73

Producers of flue-cured tobacco in particular required wood for curing tobacco, and constructing tobacco barns, as well as large tracts of virgin bushes to clear every year to put up new crops.Footnote 74 Figure 1.2 shows the practice of clearing virgin bushes for tobacco farming. Seed bed preparation also required a lot of firewood to burn the ground for the control of insect pests and weeds.Footnote 75 When European settlers established farms in the virgin bush, deforestation and soil erosion became the major challenges and environmental hazards.Footnote 76 This was more accentuated in the tobacco farms as the crop typically depletes the soil more than any other crop since it has a voracious appetite for nutrients such as potassium, calcium and nitrogen.Footnote 77

Figure 1.2 Clearing of virgin land on a tobacco farm in Marandellas in 1912.

The depletion of the soil was particularly deleterious in the sand veld because the soils were so light and of poor fertility that fertilisers were first used for tobacco ahead of any other crop.Footnote 78 A writer in 1898 noted of the poor nature of the sand veld soils in Southern Rhodesia that ‘they do not remain fertile unless manured’ adding that ‘at present manuring is not possible as there are no cattle’.Footnote 79 He also pointed out that another trouble caused by the sandy nature of the soil was that it was so loose a heavy shower of rain always washed it away.Footnote 80 However, in the later days of tobacco cultivation farm manure and green manure were recommended as well as wood ash supplemented with commercial fertilisers.Footnote 81 In 1906, the net worth of fertilisers used was only £114, but jumped to £15, 222 in 1913, an increase of 113 fold as a result of the expansion of tobacco acreages.Footnote 82 The Handbook for Tobacco Planters in Southern Rhodesia emphasised that in order to produce a profitable leaf per acre in the granitic soils large quantities of fertilisers had to be used.Footnote 83 In Nyasaland, where production of flue-cured had begun in the southern provinces in 1904, soil exhaustion was also becoming a serious problem because of the increasing pressure on the land from around 1910.Footnote 84 As migrants pushed into the southern province ‘less and less acreage was available’, and when planters could not find virgin land, they had to import chemical fertilisers to revive their fields.Footnote 85

In 1912, the Southern Rhodesia chief tobacco officer Mr Rice warned growers that tobacco could not be grown in the same lands for more than two years, and it would be advantageous in the third year to put in a leguminous crop such as cow peas and ‘kaffir beans’ to restore the fertility of the soil to a considerable extent.Footnote 86 This practice, however, was received with little enthusiasm by tobacco growers who preferred to use new lands each year thus extending opened-up lands and making them in succession very susceptible to degradation.Footnote 87 Cognisant of these emerging environmental challenges, in 1913 the irrigation officer had written an article ‘The Dangers and Prevention of Soil Erosion’ in the Rhodesian Agricultural Journal.Footnote 88 In the article he insisted that erosion was beginning to show its effects in the territory of Southern Rhodesia, and several farms in Mashonaland had suffered significantly with siltation of rivers along most of the occupied farms.Footnote 89 In October 1914, Mr. Lionel Cripps, one of the pioneer tobacco farmers moved a motion in the Southern Rhodesia Legislative Assembly exhorting the government to take steps to combat soil erosion in Southern Rhodesia, since in his words ‘a stich in time saves nine’.Footnote 90 He correctly observed that the erosion problem was being most felt in the sand veld tobacco farms that composed of light soils more liable to be washed away.Footnote 91 This view was supported by another legislator Mr Cleveland who observed in 1919 of tobacco farmers that they had been growing an article which they could export or sell very profitably resulting in large areas cultivated year after year with the fertility of the soil significantly extracted with nothing being put back.Footnote 92

The environmental problems nascently manifesting themselves in the tobacco farms were compounded by the tobacco boom occasioned by the war. The First World War accelerated the rise of the cigarette consumer culture as patterns of use amongst servicemen increased its consumption.Footnote 93 The tobacco economy became more allied with the state and in the USA the Federal government recognised the tobacco industry as an ‘essential’ industry resulting in a huge boom in cigarette manufacturing and consumption.Footnote 94 This positive upward trend in the global export market for Southern Rhodesian tobacco was given another jolt in 1919 by the granting of an imperial preference of 1/6 duty free by the United Kingdom government on tobacco grown anywhere in the empire and marketed in the United Kingdom (UK).Footnote 95 The result was an expansion in tobacco acreages such that in 1920 tobacco which had hitherto taken up less land than beans became the second most important crop after maize.Footnote 96 The imperial preference offered a great export opportunity for Rhodesian and colonial tobacco to access the UK market without facing competition from old and established tobacco-growing countries such as the USA, Turkey and Greece.Footnote 97 In 1925, the British government increased the existing imperial preference from 1/6 to 1/4. The Wembley exhibition that was held during the same year in London supplied a platform to showcase Rhodesian tobacco to UK and European buyers. Consequently, from 1925 the Southern Rhodesian tobacco industry had shifted its interests from the United Tobacco Company and South African market towards the Imperial Tobacco Company (ITC) and the UK market.Footnote 98 The demand for Rhodesian tobacco on the UK market created a tobacco rush between 1925 and 1928 as well as an influx of new settlers from Britain willing to cash in on the bubble brought in by the imperial preference.Footnote 99 The policy of the Responsible government that had come to power in 1923 was to encourage many white settlers immigrating to Southern Rhodesia to grow tobacco.Footnote 100

Consequently, from 1925, tobacco barns sprang up all over the colony, and tobacco farming spread further into the bush in areas such as Banket and Umvukwesi.Footnote 101 The number of white settler tobacco growers increased from 189 in 1925 to 336 in 1926, once again increasing to 763 in 1927.Footnote 102 The influx of new settlers caused by the tobacco rush created a host of conditions for land settlement particularly visible in the planting of larger acreages, agricultural speculation and the growing of low-quality tobacco.Footnote 103 Because of high prices paid for tobacco, a lot of farmers left cotton and maize to grow tobacco between 1925 and 1927 resulting in a ‘startling’ expansion of the tobacco industry.Footnote 104 In addition to planting large acreages the pioneer tobacco farmers also rarely practised crop rotations. During the 1926/1927 season 30,164 acres were devoted to tobacco, a total increase of 16,249, from the 1925/1926 season acreage.Footnote 105 The report for summer crop returns for 1926/1927 revealed that the expansion in acreages had resulted in single-crop systems and the neglect of crop rotations. The report noted:

It will be observed that 448 farms only grow a single crop (tobacco) and are therefore not practising crop rotation at all. The land planted to tobacco is not regularly used in rotation. It is evident therefore that this important side of agricultural practice is not given the attention it deserves.Footnote 106

In August 1927, the British Secretary for Dominion Affairs Lord Amery visited Southern Rhodesia during the Salisbury Agricultural Show and proclaimed that the country was producing very little tobacco as the UK market could absorb as much as ten times the amount of tobacco being produced up to 200 million lbs.Footnote 107 Lord Amery’s statement prompted a huge increase in tobacco acreages during the 1927/1928 season. Area planted to tobacco went up from 30,164 to 46,622 acres.Footnote 108 Resultantly, production multiplied more than fourfold from 5,660,000 lbs during the 1926/1927 season to 24,889,000 lbs in1927/1928.Footnote 109 There was a crisis of overproduction as there was no ready market to absorb the surplus leaf. Table 1.1 shows the importance of the UK and Union markets for Southern Rhodesia’s tobacco industry. Between 1925 and 1929 the UK and Union of South Africa imported 49,000,000 lbs of flue-cured tobacco from Southern Rhodesia against 845,000 lbs for all the other importing destinations.

Table 1.1 Southern Rhodesia tobacco exports, 1925–1929

| Year | Union of South Africa | United Kingdom | Other Countries | Total Lbs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 2,015,507 | 360,502 | 59,498 | 2,435,507 |

| 1926 | 2,629,269 | 1,417,349 | 241,216 | 4,287,833 |

| 1927 | 7,439,103 | 8,160,761 | 157,118 | 15,756,802 |

| 1928 | 4,836,138 | 9,504,356 | 204,687 | 14,545,181 |

| 1929 | 8,355,230 | 3,380,819 | 182,005 | 11,918,054 |

| Totals | 25,275,246 | 22,823,787 | 844,524 | 48,943,377 |

The ITC relied on American leaf and could not readily take larger amounts of Rhodesian tobacco into their popular brands. The report of the Select Committee on the Position of the Tobacco Industry noted this reality and admitted that British manufacturers held a big interest in American tobacco and would be disinclined to do anything to affect those interests by pushing for brands made entirely from Rhodesian tobacco.Footnote 110 The disaster of 1928 caused a tobacco crash that had far-reaching consequences for the industry. The implications of this disaster for tobacco farming will be discussed in a later section.

Cultivating Class, Race and Social Violence: Tobacco Farming and Labour in Southern Rhodesia, 1900–1945

The history of African labour in Southern Rhodesia’s economic growth has received a great deal of scholarly attention.Footnote 111 The history of labour in tobacco farming, however, has received no other detailed attention outside the seminal work of Steven Rubert who documented various labour regimes in the settler tobacco farms and a rigorous African labour discipline and control system described as ‘benevolent paternal autocracy’.Footnote 112 While Rubert’s tobacco labour history is an authoritative account, it did not integrate itself in a broader and more nuanced global frame linking labour practices in tobacco production within world-wide theories of the history of labour and tobacco production. The problems associated with tobacco production and labour exploitation have all come to be viewed in global terms through the appropriation of a global language and a global framework.Footnote 113 Thus, Rubert did not connect to the broader global studies on tobacco production and labour regimes but wrote a localised history of tobacco labour practices and regimes in Southern Rhodesia that missed how these practices connect to the globalised social disruptive heritage of the crop. Tobacco farming is an ‘intensive, tedious, year-round occupation’ involving a series of operations carried out manually.Footnote 114 Tobacco requires much more labour than any other crop. Tobacco requires more scrupulous management per acre than cotton, rice, or sugar.Footnote 115 Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, while the production of other agricultural products was becoming more mechanised tobacco continued to demand an even greater degree of meticulous hand labour. Consequently, the cultivation of tobacco through its huge labour demands reified cultural meanings of belonging, identity, race, class and gender within the social landscape.Footnote 116

The demand for labour in tobacco production imposed hierarchised social order that transitioned across the centuries as the locus of production shifted from plantations to the independent yeomanry. The plantation tobacco economy in the Americas initially relied on the labour of indentured white servants, but by the late 1600s tobacco planters turned to black slave labour and this shift was accompanied by new forms of labour control and management and a racialised reordering of the social hierarchy within the tobacco estates.Footnote 117 Tobacco cultivation absorbs about half a year of working time and it is often merciless with labour.Footnote 118 Labour peak tasksFootnote 119 include transplanting, weeding, suckering, topping, harvesting, curing and grading.Footnote 120 Tobacco cultivation was closely tied to the use of gangs of labourers who worked under rigorous and aggressive managerial strategies to maximise the quality of the leaf.Footnote 121 When slavery ended, there was a renegotiation of labour relations on tobacco farms. During the twentieth century, the locus of production shifted to the household where male farmers exploited the unpaid labour of women and children.Footnote 122 Production became centred on smaller areas of about three acres on which two thirds of women and children’s labour was devoted.Footnote 123 The conditions for family labour in American tobacco farms were so grim that one writer observed that women and children slept in bedrooms crowded with tobacco and the children were ‘gummy and dirty from contact with the tobacco stalks, their youthful faces tired’.Footnote 124 Studies of contemporary tobacco-production systems have also been able to confirm the continuation of social violence as part of the historical heritage of tobacco cultivation labour regimes.Footnote 125

From the earliest pioneer days, the major problem that confronted settler tobacco farmers in Southern Rhodesia was perennial shortages of African labour. In 1906 at its Annual General Meeting the Mashonaland Farmers Association pointed out that the lucrative potential for tobacco production was going to waste as a result of the unwillingness of ‘natives’ to be engaged as labourers in the farms.Footnote 126 The position of most tobacco farmers with respect to labour was reported in the Rhodesia Herald as being so bad that many growers were obliged to suspend operations until the necessary labour had been procured.Footnote 127 In 1911, the ‘native’ labour question was described as the ‘most acute crisis’ in Southern Rhodesia, and in several districts the lack of labour had been so great that tobacco farmers were without ‘boys’ (meaning African adult men in the demeaning nomenclature of the time) for reaping their crops.Footnote 128 The labour crisis was endemic and was particularly caused by the unwillingness of Africans to work for wages in European farms because they could grow their own crops and sell surplus to earn enough for subsistence and pay their taxes.Footnote 129 The report of the Native Labour Committee (1927–1928) acknowledged this inconvenience with regret:

Considerable inconvenience and in some cases, loss is suffered yearly by many farmers during the months of November to January owing to a large percentage of indigenous labourers going to their homes for the purpose of ploughing and planting at the very time when farmers require additional labour.Footnote 130

The few Africans willing to be employed for wages preferred working in mines where they were paid higher wages.Footnote 131 The importance of African labour as a raw material for tobacco cultivation was captured by one colonial official:

Natives resemble tobacco in as much as they love veld where tropical and sub-tropical conditions make the struggle for a livelihood comparatively easy, and consequently they avoid the watersheds and are found in their numbers on the low veld, and a good supply of native labour is essential to the tobacco planter.Footnote 132

Between 1910 and 1914, the average labour required for cotton in Southern Rhodesia was 60–100 man-hours per acre, for maize 37–100 man-hours per acre and for tobacco of all kinds 356 man-hours per acre.Footnote 133 Before the advent of extensive mechanisation in the post–World War II era, seventy acres of tobacco needed a labour requirement of about 150 ‘native’ boys.Footnote 134 Consequently, African labour expended a lot of capital resources as an expenditure item on the tobacco farm. The cost of African labour fluctuated across the years but by the post– World War II years as a single item, it accounted for 27 per cent of total costs on the farm while expenses for European labour gobbled up 18 per cent of total costs.Footnote 135 The Select Committee appointed in 1949 to investigate the reasons for labour shortages in agriculture and its maldistribution noted the huge disparities in labour requirements between tobacco and other agricultural commodities and enterprises.Footnote 136 It pointed out that tobacco absorbed more work units per acre than other crops as shown by Table 1.2.Footnote 137

Table 1.2 Labour requirements in agriculture in Southern Rhodesia, 1940–1949

| Crop or Stock | Unit | Unitary Labour Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| Tobacco | Per acre | 10.0 |

| Grain | ″ | 1.3 |

| Groundnuts | ″ | 5.0 |

| Potatoes | ″ | 5.0 |

| Cotton | ″ | 3.0 |

| Other Crops | ″ | 1.0 |

| Dairy Cows | Per head | 1.5 |

| Other Cattle | ″ | 0.3 |

| Pigs | ″ | 0.5 |

| Sheep and Goats | ″ | 0.2 |

The mechanisation of agriculture between 1900 and 1945 did not have a significant impact in changing the labour demands in tobacco production as most of the later stages in the production process of tobacco such as priming, topping, suckering, reaping and grading could not be successfully mechanised. Therefore, despite headway in mechanisation that had been made particularly in securing traction, the average man-hours per acre for tobacco production in Southern Rhodesia was estimated to be as high as 1600 hours.Footnote 138

The perennial labour crisis within the colony led to the creation of the Rhodesian Native Labour Bureau (RNLB) in 1903 mostly to supply mine labour, but it became a very useful conduit for the supply of chibaro labourers to tobacco farmers.Footnote 139 During periods of critical labour shortages some white settler tobacco farmers would coerce the company administration to use more effective methods of procuring labourers faster than the RNLB.Footnote 140 As the demand for tobacco farm labour rose, the bureau (RNLB) recruited labourers from Nyasaland, Northern Rhodesia and Mozambique and distributed them to tobacco farmers at prescribed rates and fees. A transport service system called Ulere was established for smooth transportation of labour from Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia.Footnote 141 The cost of procuring each labourer for twelve months service including cost of return journey was £1.10s.Footnote 142 The labour crisis compelled tobacco farmers to adopt nefarious labour recruitment methods that included kidnappings and coercion. Tobacco farmers set up offices in various parts of the country and used all forms of shrewd means to snatch up labourers from maize and cattle farmers.Footnote 143 In one of the cases of recruitment by coercion, two African labourers were hoodwinked by a white tobacco farmer to travel from Bulawayo to Salisbury (a distance of 430 kilometres) upon being promised work in a Salisbury factory only to find out that they had been forcibly recruited as tobacco labourers for a farm in Umvukwesi:

I was contracted by Mr Morrison in Bulawayo, he offered us £2/ month if we agreed to work in Salisbury, we agreed to his terms and 8 natives came to Salisbury with him. We were taken before the Native Commissioner Salisbury and we were told we would be required to work in his tobacco farms in the Umvukwesi for £1/month for 12 months. We refused the offer … Mr Morrison then said, alright you can walk back to Bulawayo where you will be arrested. We had neither money nor food, so we had to accept.Footnote 144

Another nefarious recruitment practice popular in the tobacco farms in Southern Rhodesia was the employment of children. In 1928, The Southern Rhodesian Legislative Assembly passed the Native Juvenile Employment Act to regulate the employment of ‘native’ juveniles particularly in the European farms.Footnote 145 The Act was simply an attempt to codify and legislate for something which was already a fact in many farms and economic sectors of Southern Rhodesia.Footnote 146 During the debate on the bill, one legislator Sir Ernest Montagu pointed out that on many tobacco and cotton farms women had arrived with very young and small children who had been rather useful in picking cotton and reaping tobacco.Footnote 147 The President of the Makoni section of the Rhodesian National Farmers Union (RNFU), however, noted that, the seriousness of the bill was clearly demonstrated by the fact that the League of Nations had laid it down that forced labour for private gain was slavery.Footnote 148 Sir Lionel Cripps described the bill in his correspondence with the Governor of Southern Rhodesia as representing a ‘peculiarly odious form of child slavery’.Footnote 149 In the House of Commons in Britain the bill received a lot of scrutiny and attacks from British law-makers. One speaker who spoke in opposition to the bill pointed out that the law was being enabled and given succour by the profits being realised by Rhodesian tobacco farmers because of the imperial preference on empire-grown tobacco.Footnote 150 The imperial preference was now spurring Rhodesian growers to produce much tobacco at low labour costs and exploit African children.

On 29 December 1927, the Chief Native Commissioner noted that there was a growing entry of small children into the tobacco industry, and children were being employed on a larger scale.Footnote 151 He admitted that child employment was already a common practice and during the past thirty years children had been ‘regularly employed’ on tobacco farms.Footnote 152 A concerned missionary pointed out in a private letter to the Chief Native Commissioner that in his view the tobacco industry was factory work, calling for factory work precautions with respect to children.Footnote 153 Children were employed in the tobacco farms because their labour was cheaper amounting to three or four pence a day and five shillings for a month.Footnote 154 Children were considered better suited than adults for such tasks as grading and stringing of tobacco as they were considered ‘nimble-fingered’ and ‘sensitive to touch’.Footnote 155 The report of the Native Labour Committee vindicated the use of child labour on the tobacco farms and noted that the light nature of several branches of work in the tobacco industry provided very suitable conditions for the employment of the ‘native’ youth and would ‘undoubtedly attract more and more in the near future’.Footnote 156 In 1949, the report on native labour admitted that children of about eight years upwards were employed on both casual and permanent basis on tobacco farms for lighter seasonal work.Footnote 157 By the late 1940s, juveniles constituted a significant proportion of labour on most tobacco farms in Southern Rhodesia varying from between 15–25 per cent of the total labour force.Footnote 158

Conditions of Tobacco Farm Labourers in Southern Rhodesia, 1900–1945

Eurocentric social histories of tobacco farm labour in Southern Rhodesia framed the white settler tobacco farmer as a benevolent patron presiding over ‘primitive’ but happy and contented ‘native’ labourers.Footnote 159 The African tobacco farm labourer is cast as distinctively better off than his companion in African townships and urban centres who was overcrowded and restricted.Footnote 160 However, Rubert’s work illuminated on the grim conditions of African labour that extended from the tobacco fields to their social lives on the farm compounds. Tobacco farming activities in Southern Rhodesia took much of the year and revolved around three production phases. The low-level labour period ranging from May to August and September to November was for grading and nursery respectively; the high level (peak) period from February to April involved harvesting and curing; the middle level period from December to January was the phase for planting and field culture.Footnote 161 The work hours on a tobacco farm varied depending on the nature of the work and tasks but on average male employees worked for 265–285 days in a year with a typical workday varying between six and eighteen hours and labourers working from dawn to dusk.Footnote 162 Labour organisation and efficiency on tobacco farms was based on the notion that Africans responded to a rigid form of discipline and that ‘natives’ understood force and coercion.Footnote 163 There was the use of physical violence sometimes to instil discipline through caning, whipping and clouting.Footnote 164 There were two forms of labour organisation on tobacco farms in Southern Rhodesia – task work and gang labour. Contract or task work involved the allocation of daily work to each employee. Contract work was more commonly used for the annual stumping of virgin lands, collection of wood fuel, weeding, untying cured tobacco and grading.Footnote 165 Gang labour was used for tasks that required intensive use of labour such as planting, suckering and reaping.

Tobacco farm labour in Southern Rhodesia was very gendered. Most of the work was done by adult males and women were not seen as ‘actual workers’.Footnote 166 Globally, the history of labour in tobacco production reveals that gender roles were distinct, and much of the labour-intensive work on the farm was the domain of men while women played at most complementary roles. In America for instance the role for women labourers in tobacco farms during much of the nineteenth century was to prepare food and cook meals for gangs of male labourers.Footnote 167 In Southern Rhodesia women and girls were usually only hired during the busy and peak periods of farm work. They were employed as casual labourers during the period February or March to June and July usually only when male labour shortages were acute.Footnote 168 Even then, female labourers would receive less wages (usually two thirds of what males were getting) than their male counterparts and were not allocated rations. Women’s tasks involved weeding, suckering, untying tobacco and grading.Footnote 169 The average wages for African labour varied across the years but they were generally below the cost of living as testified by the 1927/1928 Native Labour Committee.Footnote 170 In 1913, the average wage was 20s, in 1923/1924 17s.5d, then 19s.16d for 1925/1926 and 21s.4d during the 1926/1927 season.Footnote 171 There was a discernible and conspicuous social and wage hierarchy on tobacco farms. In 1947, European managers were being paid between £20–£40 per month plus a percentage of net profits varying from 10 to 25 per cent.Footnote 172 Keep and accommodation were also provided in addition to the average gross wages. Boss boys (task supervisors) were at the top of the social hierarchy on a tobacco farm and earned £3.2s.6d/month by 1945, and tractor boys earned an average wage of £3.Footnote 173 The rates for general labourers fluctuated even on the same farm between £1.5s and £2.5s in 1945. Young children were paid anything between 2s.6d and £1 with an average rate running at 14s. To justify the poor salaries, white farmers and colonial officials often argued that the wage incentive was weaker with African labourers as they had fewer wants and needs which could be satisfied by other non-monetary incentives.Footnote 174 Rations – weekly supplies of food items were the most popular incentives used by tobacco farmers to keep African labour on the farms. Although the quantities and variety of rations differed from farm to farm the standard weekly ration on a tobacco farm usually consisted of 14–16 lbs mealie meal, 2 lbs of beans or monkey nuts, 1–3 lbs meat or 1 lb dried fish and 4 oz of salt.Footnote 175 Sometimes tobacco and soap would be added to the rations.Footnote 176 The supplies of rations were inadequate for subsistence and farm labourers had to supplement with growing their own food in small pieces of land, hunting game and brewing and selling beer.Footnote 177

The compound was the centre of farm social life on a tobacco farm. The compound as the living space for working Africans has been explored in labour history of southern Africa as not only physical space but denoting a system for labour control and discipline.Footnote 178 The compounds on tobacco farms were much adopted to conform to the tribal aspects of African life so that the ‘native’ would have access to the conveniences of his ‘primitive’ lifestyle. The compounds resembled African villages and composed of mud and straw huts. The farm compound was constructed around colonial prejudices about Africans being happier and contented living in conditions akin to their kraal life.Footnote 179 These prejudices became an alibi for not constructing proper housing facilities in the compounds as ‘brick-built cottages’ were not always to the liking of Africans who ‘preferred a snuggery without windows’.Footnote 180 The houses for tobacco labourers were poor. The report of the Native Labour Committee in 1927 observed that most of the conditions in the farming compounds were deplorable. There was lack of proper sanitary accommodation on almost all farms and most compounds had ‘grass shelters and leaky hovels’ detrimental to the health of the employees.Footnote 181 The Report on labour shortages echoed this and noted that housing provided on most tobacco farms was of poor quality and made from pole and dagga.Footnote 182 The farm compounds also lacked the basic sanitary infrastructure and tobacco farmers were reluctant to spend money on lavatories for their workers such that they had to defecate in the bushes around their living areas.Footnote 183 However, from the 1940s as a result of the tobacco boom which is explored in the next chapter some tobacco farmers had started to offer some more social amenities on their farms. A survey of eighty tobacco farms in 1949 revealed that twenty employed a native schoolteacher and one farmer provided a private clinic, school hall and recreational hall for a staff of 100 boys.Footnote 184 Three farms had laid aside football pitches and organised teams for leisure.

The Global Depression and the Tobacco Crisis in Southern Rhodesia, 1930–1934

The 1930s witnessed two momentous global developments that markedly impacted the patterns of settler agriculture in colonial Africa – the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl disaster.Footnote 185 The Great Depression riled settler and African agricultural economies as export markets collapsed and farmers went bankrupt. The Dust Bowl disaster chastened colonial officials over the ecological crisis that could ensue from unbridled agricultural expansion and instigated concerns about environmental stewardship at a time when overproduction of cash crops was causing land degradation and soil erosion.Footnote 186 To this end, there is a consensus amongst historians that state intervention in agricultural economies in colonial Africa during the 1930s was influenced by the financial pressures of the Depression and the ecological apprehensions evoked by the dust storms in the USA. The Dust Bowl amplified ecological concern and thrust soil conservation within the precincts of colonial intervention resulting in several ambitious conservation programmes prioritising the construction of contour banks and protection of arable land with storm drains. This became much pronounced as the twin conditions of overpopulation in African areas and overproduction in white settler areas were contributing to land degradation.Footnote 187 Intensive cash cropping in both the settler areas and African reserves had resulted in overproduction and a deep crisis in the colonial agricultural economies. However, although white settler farmers and African peasants were both equally to blame for land degradation and soil erosion due to overproduction and monocropping, Africans’ wasteful agriculture was always used as a convenient scapegoat to marginalise African rural producers during the 1930s.Footnote 188

The global agricultural recession that intruded agricultural economies in colonial Africa during the 1930s and drew the attention of the state was a result of overproduction that had created a glut.Footnote 189 New areas had been opened for agricultural expansion spurred by a rise in global agricultural commodity prices during the 1920s. The cash crop boom witnessed much intensive exploitation of grasslands and marginal areas that culminated in soil erosion and land degradation in many countries.Footnote 190 In 1931, the International Economic Conference of the League of Nations pointed out that low agricultural prices in comparison with production expenditure were a result of overproduction stimulated by improved technical methods and the cultivation of new areas.Footnote 191 In the USA, the agricultural crisis hit the tobacco sector so severely that prices fell dramatically between 1928 and 1931 precipitating an acute crisis in most tobacco-producing states and resulting in conditions of poverty, homelessness and unemployment.Footnote 192

When the Great Depression arrived in Southern Rhodesia; it found a tobacco sector that was already struggling – facing overproduction, insufficient markets and a concomitant dramatic fall in prices. While tobacco exports had contributed 46.4 per cent and 42.7 per cent of all agricultural exports in 1927 and 1928 respectively, the figure had dropped precipitously to 17.1 per cent and 17.4 per cent in 1929 and 1930 respectively ruining most of the commercial farmers, who were forced to close shop.Footnote 193 The disaster of the 1928 and 1929 crop claimed the scalp of three quarters of the total producers and saw production falling sharply to 5,500,000 lbs in 1930 from a record high of 24,943,044 lbs during the 1927/1928 season.Footnote 194 One tobacco grower in the Umvukwesi area Mr H. J. Quinton tragically portrayed this gloomy scenario, noting wistfully that ‘in 1928, you couldn’t sell tobacco, in 1929, you couldn’t sell tobacco, and in 1930, you couldn’t sell tobacco’.Footnote 195 The depression obliterated all the progress that had been made in the sector during the previous ten years and many farmers abandoned tobacco and joined the ranks of the penniless unemployed.Footnote 196 The dissolution of the Customs Union between Southern Rhodesia and South Africa in 1930 further restricted the market for Rhodesian tobacco and exacerbated the crisis within the tobacco economy.Footnote 197

The crisis within the agricultural economy compelled the state to begin to take an active role on an unprecedented level (mirroring developments in North America and Europe) in white settler agriculture from 1930.Footnote 198 Chief among these interventions was the creation of commodity control boards to regulate the production and marketing of maize, cotton, beef, and dairy products – as the state stopped its reliance on unregulated activities of private farmers.Footnote 199 In 1934, the state, wary of the precarity of the agricultural industry instituted a Commission of Enquiry into the Economic Position of the Agricultural Industry in Southern Rhodesia under the Chairmanship of Mr Max Danziger, then Minister of Finance to review the farming position of the colony in general and suggest measures which could be taken to enable farming to be conducted more profitably.

The position of the growing side of the tobacco industry was described as ‘parlous and insolvent’ and the prospects of meeting a successful tobacco farmer as strenuous as those of finding ‘a top hat in a nudist camp’.Footnote 200 Most of the farmers correctly blamed the tobacco crisis on the speculative spirit that had been rampant in Southern Rhodesian agriculture where during the boom years a deluge of speculative farmers joined the industry, produced a glut, and abandoned it leaving the bona fide farmers to face the stormy years of depression.Footnote 201 The farmers contended that the land settlement policies of the Responsible Government under the Rhodesian Party, which had come into power in 1923, were much to blame for the speculative spirit destroying Rhodesian farming.Footnote 202 The inefficient farmer had come to try his luck on every agricultural enterprise, rolling fortune’s dice on every crop and making farming a mere game of luck.

The speculative tendencies rampant in white settler agriculture ruined more than the economy – they ruined the environment. In the tobacco farms monocultural over-cropping and soil erosion resulted in localised land degradation. Consequently, there were calls for the government to discourage settlement on virgin land.Footnote 203 This was thought necessary because most of the tobacco speculators would abandon the land during times of low prices after a few years cropping.Footnote 204 The Southern Rhodesian tobacco farmer’s carefree attitude to land and the environment was similar to that of his American counterpart who was described as a ‘thriftless parasite who did no permanent work, destroyed firewood and took no thought of tomorrow’.Footnote 205 The itinerant monocropping of tobacco was one of the major problems in Southern Rhodesia. In Hartley district for instance, not more than 10 per cent of the tobacco farmers on the land obtained a living from it, with most of the land on the farms developed with barns and houses but now deserted, yet six years before such land had been occupied.Footnote 206 Both the long-term farmers and speculative farmers were single cropping tobacco and growing very little (if any) maize, and when they grew maize it was largely for their own domestic consumption.Footnote 207 These single-crop farmers were a liability to the farming industry as monoculture compounded the erosivity of the soil.Footnote 208

The report of the Commission of Enquiry into the Economic Position of Agriculture in Southern Rhodesia declared that Southern Rhodesian forests had long been abused by tobacco farmers with the result that the colony was now confronted with falling timber supplies. The report observed that the colony of Southern Rhodesia was eating voraciously into its forestry capital and exhorted tobacco farmers to protect indigenous timber by less wasteful felling, fire protection, systematic re-afforestation and the employment of heat efficient furnaces.Footnote 209 The report also referred to the problem of soil erosion as a national question that if ignored would turn the country into a desert and exhorted famers to adopt contour ridges.Footnote 210 The report acknowledged the slow pace of tobacco research and the need for a more proactive government sponsored programme.Footnote 211

Tobacco Culture and the Environment in Southern Rhodesia, 1930–1945

The Danziger report had established that speculative production and gambling lay at the core of the tobacco crisis that lingered from 1928. Much of the environmental problems within the tobacco farms were a result of the cultural practices in tobacco production (mentioned before) from the nursery to the curing barn that involved veld burning, stumping and clearing of virgin lands. Tobacco farmers required wood for curing tobacco, and constructing tobacco barns, as well as large tracts of virgin bushes to clear every year to put up new crops.Footnote 212 Virgin lands were touted in official discourse as the most suitable areas for an ideal tobacco crop. Stumping virgin lands was an important routine and practice in the tobacco-production cycle and oft took much labour on the farm. Trees were felled with hand saws and axes, thick brush had to be cleared, logs were sliced for wood fuel, appropriate timber reserved for material for building tobacco barns while the rest of the brush was consumed with fire.Footnote 213 Stumping virgin land for tobacco production was so significant that as a cost in the mid-1920s it averaged between £1 to £1.15s an acre.Footnote 214 With vast areas of forested lands, cheap land prices, large farms measuring over 3,000 hectares the practice of stumping virgin land every year came with very low costs to the farmer.Footnote 215

The cultural practice of stumping virgin lands every year for a new crop became more prevalent because of the eel worm and nematode problem.Footnote 216 The nematodes problem was so pervasive that in 1920, entomologist R. W. Jack had advised growers to totally abandon lands that showed heavy infestations.Footnote 217 In 1935, the problem was described by the Tobacco Research Board (TRB) as ‘the gravest danger to the tobacco-growing industry in Southern Rhodesia’.Footnote 218 In 1938, a survey by the branch of entomology revealed that nematodes were ubiquitous on all soils except newly opened virgin lands.Footnote 219 As a result of this heavy infestation, large areas of land were opened up and cleared every year in the tobacco districts such that there were hundreds of abandoned farms and derelict lands, a situation which compounded the soil erosion problem of the colony.Footnote 220 Ironically, this peripatetic practice in settler tobacco cultivation was happening at a time when colonial officials were overtly critical and abhorrent over an almost similar practice of ‘shifting cultivation’ amongst African farmers which they reckoned ‘primitive’ and wasteful to the environment.Footnote 221 In 1934, Southern Rhodesian forester Edward Kelly pointed out that shifting cultivation was damaging to the environment, inhibited regeneration of the veld and depleted soils.Footnote 222 Consequently, the state in Southern Rhodesia had begun to enforce strict conservation principles and land centralisation in the African reserves from as early as 1925 to combat the wasteful practices of ‘kaffir farming’ that exhausted soils and destroyed grazing lands.Footnote 223 Indeed, much scholarship on colonial conservation historiography has affirmed that while the state zealously enforced conservation on Africans during the 1930s, its hand on settler farmers was very lax and noncommittal.Footnote 224 In colonial Malawi for instance, while the state had imposed a harsh conservation campaign in the Native Trust Lands, its policy on environmental degradation taking place in the tobacco estate sector in the Shire highlands was one of ‘benign neglect’.Footnote 225

To make matters worse for the tobacco farmlands before the introduction of nematicides during the 1940s the only practicable and effective method of control for eelworm was exploitation of virgin lands. Although preliminary research from the 1930s pointed towards the use of grass in rotation with tobacco as a palliative, the scenario for most tobacco farmers was either virgin soil or abandoning production altogether since they did not have other crops or animal husbandry lines to integrate such rotations.Footnote 226 Although the ideal was for every tobacco farmer to be a mixed farmer, this did not work out well in practice during these days. The best tobacco was grown on the sand veld, and maize on the heavier soils. On the sand veld maize production was seldom a paying enterprise and when utilised as a rotation with tobacco it would deplete the soil so severely as to make the lands useless for future tobacco crops.Footnote 227 Thus, as a result, thousands of acres of land had to be abandoned after one-year cropping for want of a suitable rotation.

The crisis of overproduction and speculation also created other pest and disease problems in the tobacco farms particularly from the late 1920s as production spread into new areas. In 1932, Leaf curl the first insect borne disease in Southern Rhodesia was reported by entomologist H. H. Storey who identified the vector as white flies.Footnote 228 The culture of nomadic farming prevalent in tobacco farms meant that tobacco stalks and untidy fields were left unattended perpetually and as breeding points for vectors to spread. These unhygienic practices prompted the state to pass the Tobacco Pest Suppression Act in 1933 that made it mandatory for tobacco farmers to destroy their residual tobacco stalks by 1 August of each year.Footnote 229 However, unhygienic cultural practices continued leading to more disease outbreaks. In 1938, Rosette disease caused by aphids occurred in Umvukwesi.Footnote 230 The diseases caused ‘bushy top’ – the dwarfing and stunting of growth of tobacco plants.Footnote 231 The result was severe losses to most tobacco farmers. From 1937 to 1944 there was a huge outbreak of Alternaria (or brown spot disease, a fungal infection affecting the lower and mature tobacco leaves) in most tobacco-producing areas of Southern Rhodesia.Footnote 232 From 1937 to 1940 heavy losses had followed in all parts of the colony amounting to 3.5 million lbs of tobacco.Footnote 233 As a result of the prevalence of these tobacco diseases field-spraying experiments were conducted on a larger scale and the amount of fungicides and arsenic pesticides such as lead arsenate used annually for seed bed and field spraying steadily increased from around 1939.Footnote 234 Arsenic contaminates the environment, poisons the soil, and causes sickness and death to animals and humans.Footnote 235 The chemical contamination of the environment as a result of tobacco field sprays is more comprehensively covered later in Chapter 3 of this book. However, various veterinary reports and reports from the branch of chemistry between 1932 and 1938 record livestock and wildlife mortality due to arsenic poisoning.Footnote 236

The other environmental problem that arose with tobacco farming during the 1930s was soil erosion. Soil conservation had also become a concern for the colonial state in Southern Rhodesia during the 1930s.Footnote 237 There is consensus that before 1930 soil erosion and conservation were not key priorities of the colonial state, and ‘rapacious settler farming’ dominated the agricultural landscape.Footnote 238 However, the institutionalisation of these ideas is subject to much critical scholarly debate. Beinart locates the South African Drought Investigation Committee Report of 1921 as a key influence in shaping the development of soil-conservation ideas not only in Southern Rhodesia, but in the whole of the subregion.Footnote 239 Ian Phimister, on the other hand, is highly critical of Beinart’s modest appreciation of state conservation efforts in settler farming in the 1930s and posits that significant progress only happened from 1938 when the pressures of the depression had ceded.Footnote 240 While Beinart points to the significant progress in conservation works in Southern Rhodesia, there were several production factors that militated against the effectiveness of this practice and its institutionalisation on the tobacco farms. First, tobacco was cultivated in the flimsy sandy loamy granitic soils that were very susceptible to sheet erosion. Even with contour ridges, the traditional vertical ridge ploughing for tobacco would always catalyse the erosion problem. The straight and vertical tobacco rows which were generally adopted by farmers departed from the curve of the contour with the ridge not having the necessary ability to hold and pass on water. This resulted in a concentration of silt laden run-off into the contour ridges, choking and breaking them. The conservation officer from the Irrigation Department, noted of this practice in 1945:

Recently I visited a farm where this was causing a fantastic amount of erosion, though the land was contour ridged. To have flattened the slope of the tobacco rows to a safe gradient would have been impossible, owing to the irregularity of the ground caused by old erosion and in despair I remarked to the farmer, ‘if you don’t get rid of your ridging ploughs, you will get rid of your farm…’Footnote 241

Most tobacco lands were badly ploughed down by ridging ploughs which left behind deep furrows that made most fields vulnerable to an extended amount of gully erosion.Footnote 242 But, even then the practice of building conservation works was generally uncommon amongst tobacco farmers and this was pointed out by various agricultural conservation officials and reports from the late 1930s. Between 1931 and 1937, the colonial state had erected a rudimentary national soil erosion bureaucracy that included district conservation boards, conservation advisory councils and a soil erosion propaganda subcommittee.

Members of the Soil Erosion Propaganda Subcommittee pointed out in 1937 that the soil erosion problem was heavily linked to the rapacious farming practices of the settler tobacco growers. In their quest to maximise profits, they had adopted continuous and irresponsible cropping which was impoverishing the soil. They warned:

In Mashonaland the areas of rich virgin lands which have been opened up since the days of the early settlers have been mined and the soil impoverished by continuous cropping and erosion until many of the lands have been abandoned as useless … in other cases farmers have continued to flog the dead horse by trying to extract a living from an impoverished soil owing to the reduced yield, the acreage is extended in order to obtain a larger crop, and this process continues whether prices are low or high.Footnote 243

In Nyasaland, white settler tobacco farmers were equally irresponsible and reckless with the control of erosion in their farms. When Southern Rhodesian irrigation engineer W. E. Haviland toured Nyasaland in 1930, he was baffled to see many tobacco farms in a state of disrepair as the estate owners did not use any methods to control erosion.Footnote 244 The lack of a robust thrust in state conservation intervention within the tobacco farming sector in both Southern Rhodesia and Nyasaland stands in contrast with the USA during the same time where the state had to assuage the financial turbulence and the crisis of overproduction with a coterie of measures that integrated production control, price support and soil conservation.Footnote 245 In 1938, the report of the Natural Resources Commission of Enquiry confirmed the importance of tobacco to the colony as an export crop whose receipts for the 1936/1937 season amounted close to £1 million, creating employment for many people and making possible the utilisation of large areas of the sand veld unsuitable for maize farming.Footnote 246 However, the report deplored the restrained pace of conservation amongst tobacco growers, amongst whom anti-erosion works had made the least progress because of the prevalence of eel worm infestations in old tobacco lands:

A certain amount of indifference as to what happens in the meantime might result in the case of a careless farmer or in one attempting to plant an excessive area, but a doubt as to the effects of contour ridging on the eelworm menace possibly accounts for a hesitation on the part of many to spend on a project which might after all be found to be disadvantageous in another direction.Footnote 247

The report further highlighted that through bad management overcutting of indigenous timber had taken place in the tobacco farms to such an extent that with the rate of cutting that existed native timber supplies would be exhausted and there would be a break in the tobacco industry for probably fifteen to twenty years.Footnote 248 This situation had reached a climax in the Umvukwesi area where 30 per cent of the tobacco growers had been compelled to acquire new farms abandoning old ones as a result of depletion of timber resources.Footnote 249 In fact, in 1930, an editorial in the Rhodesia Agricultural Journal pointed out the imperative for re-afforestation within the district to make good the wastage caused by the cutting of timber by tobacco farmers as there was a distinctive danger of ‘a timber famine’ if remedial measures were not taken.Footnote 250 A worried conservator of forests buttressed the need for tobacco growers to adopt afforestation programmes with exotic Eucalyptus trees:

We are continuously getting at the tobacco farmer to look upon the product of fuel as a necessary part of ordinary tobacco operations. After all, if he has not got the fuel, he cannot cure his tobacco, and if he has not got the sufficient indigenous timber to give him his annual requirements, then afforestation with fast growing trees is needed. The situation for the tobacco grower is much simpler … because it is a fact that the tobacco-growing areas can grow trees.Footnote 251

By 1942, the state was facing an acute food deficit resulting from shortages of fertilisers and labour caused by overproduction of tobacco. Food production committees had to be set up to allocate resources towards food production.Footnote 252 In 1942, the Natural Resources Board (NRB)Footnote 253 instituted an enquiry into the conditions of agriculture in the colony that were creating food shortages.Footnote 254 The speculative tendency amongst tobacco growers was pointed out as contributing a great deal to land degradation. Captain A. D. Collins of Tsungwesi Farm in Waterfalls revealed this predatory brand of rapacious farming where land was treated with high-handed and peremptory carelessness, exploiting it for private aggrandisement by mercenary tobacco farmers:

At Inyazura you will see an outstanding example of what I call ‘the get rich quick tobacco grower’. You will see it from the Claires Estate to the Inyazura river. Every one of these farmers have acquired more land and the same thing is happening there. There is no doubt whatsoever that it has to be stopped otherwise this country has only another five or six years of tobacco life in front of it … the whole of the Claire Estates has been taken up now.Footnote 255

In the Odzi district a similar pattern was also developing where tobacco farmers were fast encroaching into bigger areas with the majority of them ‘merely exploiting the land’, and if they had two or three good years of growing tobacco, they had no further use for that land.Footnote 256 In the Umvukwesi district, mass production of tobacco and the wastage of land had created farmers in the area who denuded the land, timber and then just left the ground to be washed out.Footnote 257 The appalling situation for the tobacco farmlands was summarised by one farmer Jacobus Petrus De Kock:

Speaking not from the tobacco market point of view, but from the tobacco soil point of view … I am afraid tobacco growers are mining their land. I have been in the district for 23 years and I have seen what happened here. I would prevent any tobacco grower if I had the power from planting unless the soil was contour ridged … We grow tobacco mostly on the ridges, the crop is reaped, and the tobacco stalks are pulled out, but land is left unploughed for years afterwards and that encourages erosion. I have preached that to tobacco growers for many years, but it does not carry much weight with them. They just want to make as much money as possible with no eye to the future.Footnote 258

State Intervention in Tobacco Production and Control, 1935–1945

The problem of tobacco overproduction had reared its ugly head again in 1934 when production totalled 26,792,092 lbs – provoking déjà vu in farmers, reminding them of the disastrous record crop of 1928.Footnote 259 Their fears of another slump drove the state’s imperative for production control during the 1935–1936 season. The RTA observed that the main cause of the depression enveloping the industry and amounting almost to actual insolvency was the fact that growers were producing more tobacco than the market could handle.Footnote 260 The Association maintained that the aim was to place the industry on a sound economic basis, eliminate the fear of general insolvency on the one hand and the gambling element on the other hand:Footnote 261

The only person who would wish or could afford to take the gamble of producing more than his share would be the speculator, the chancer or the man of big money, and what might be a big gamble to him would be a very definite harm to the bona fide settled tobacco grower, and it is the economic stability of this type of producer which it is our very special business to safeguard.Footnote 262

The RTA considered it necessary to reconstruct the industry and proposed for legislation dealing with production control, which would entail holding from the market all increases of production by growers over their 1933/1934 crops. It also proposed the establishment of an Appeal’s Board where hardships would clearly be sustained by individuals by taking as a measure their production during the 1933/1934 season.Footnote 263 The Tobacco Quota Commission of Enquiry into applications from tobacco growers for increased production during the 1934/1935 season was appointed by the Ministry of Agriculture under the Chairmanship of Mr William Brown.Footnote 264 The RTA placed before the committee principles to be adopted regarding the quota. The Quota Commission received applications from growers, allocated quotas to every grower and made recommendations to the Ministry of Agriculture of the viable national quota capable of meeting facilities and market requirements.Footnote 265