What This Book Is About

Flavius Cerialis was the prefect of the Ninth Cohort of Batavians at the fortress of Vindolanda, in northern Britain, in the late 90s and early 100s AD. He was probably a Batavian noble, and necessarily of equestrian rank. We have some texts probably written in his own hand, including a draft of a letter (Tab. Vindol. 225), of which Reference AdamsAdams (1995: 129) has observed that ‘[i]ts orthography is consistently correct, and it has two types of old-fashioned spelling (the etymologically correct -ss- in occassio, twice, and saluom)’. On the basis of this and other evidence, he concludes that Cerialis’ father was probably made a Roman citizen for loyalty to Rome and that Cerialis received a formal education in upper-class Roman literary culture.

But ‘old-fashioned’ spelling is by no means restricted to texts written by the highly educated upper class.Footnote 1 As Reference AdamsAdams notes (1995: 130–1), examples can also be found in the writing of the scribes of Vindolanda, showing that education received by these professionals, whose spelling is generally highly standard, had apparently included such features. And in fact, even in a text whose spelling is aberrant enough to give ‘support to the idea that [the writer] may have been a civilian trader without access to military scribes’ (Reference AdamsAdams 1995: 130–1, on Tab. Vindol. 343, letter from Octavius), there is evidence that this writer too had been taught to use ‘old-fashioned’ spellings (although not always correctly).

It turns out that Octavius is by no means the only writer who combines substandard and ‘old-fashioned’ spelling: we will see examples from, among other places and times, first century AD Pompeii, second century AD Egypt and fourth century AD Britain. This – along with other types of what I shall call ‘optional’ spelling features – provides a unique, and unexpected, insight into the kind of education that was received by those who did not belong to the highest stratum of society, predominantly in the first to fourth centuries AD.Footnote 2 As will be discussed below, our direct access to knowledge about sub-elite education, in the form of information provided by ancient authors, is very limited. Consequently, if we want to find out about this important question in the study of Roman society, we must take indirect approaches.Footnote 3

By ‘optional’ spellings I mean those which were available for writers educated in the standard orthography of the day to use (and were hence not considered incorrect), but whose absence would not have led the educated to consider their writer to be un- or under-educated. In addition, they are non-intuitive, that is they will not be produced by a writer who has simply learned a basic mapping of individual letters to sounds.

In this book I will consider two categories of optional spelling: ‘old-fashioned’ features (on the definition of which see pp. 10–15) and diacritics used to mark vowels and glides in the form of the apex and i-longa. To do this, I use a range of corpora whose writers can be assumed, in the main, to belong to the sub-elite, even though certain of the texts in some of them may have been written by those who belong to the higher echelons of society (e.g. the equestrian prefect Cerialis at Vindolanda); as far as our knowledge allows, I will take the background of the writers into account. In addition to this primary purpose, a secondary, but not unimportant, aim is to contribute to the understanding of the development of Roman orthography – and in some cases also sound change – more generally, in order to be useful for both epigraphists and linguists.

Sub-elite Education in Literacy

The question of the extent and type of literacy in the ancient world is a perennial one and is difficult to answer. Reference HarrisHarris (1989: 259–73) estimates levels of literacy under the Roman empire to be no greater than 15% in Italy and 5–10% of the population in the Western provinces. These figures are problematic in a number of ways and are really only ‘guesstimates’. More important is his emphasis on the great variation in literacy across the empire, which was affected by a large number of factors, including social class (including slave vs free), wealth, occupation, gender, geography (e.g. location in the empire, rural vs urban, local infrastructure), linguistic background and many others.Footnote 4

There is also the issue of how to define literacy, which is hard enough to establish in the modern day: clearly most male members of the elite had received an education which rendered them capable of reading and writing highly complex literary works, but on the evidence available to us it is often difficult to know whether, for example, a craftsman who could write his name could do only this or much more. However, what is clear is that literacy, while not wide, could be deep, in the sense that certain members of the sub-elite were often literate and could read and write to a fairly high level. We have plenty of evidence for slaves of the elite acting as secretaries and reading-machines for their masters, for instance, but there are many other occupations, both among slave and (sub-elite) free, where literacy is attested or implied, and the written word was pervasive, even if it was not a great impediment to be illiterate (Reference HarrisHarris 1989: 196–233; Reference WilliWilli 2021: 14–19). For example, the majority of those carrying out business with the financier family of the Sulpicii in Puteoli, and in the similar tablets from Herculaneum (on which, see pp. 28–31), were literate, since they were able to write out a contract in their own hand (about a fifth of these chirographa were written by someone else; Reference CamodecaCamodeca 2017b: 24). Both they and the scribes who wrote the rest of these documents achieved a largely standard orthography (for some exceptions, see p. 262).

However, what is lacking is much evidence for the educational system by which those in the sub-elite learnt to read and write. Reference Bloomer, Grubbs and ParkinBloomer (2013: 451), for example, tells us:

[T]he Roman boy or girl of the first century CE came to grammar school about the age of seven, already knowing the alphabet. Reading, writing, and arithmetic were learned here. The child would learn to write and then read Greek; Latin followed. After basic literacy (including memorization and recitation) the child learned grammar, mythology, and literary criticism all together while reading a poetic text and listening to the teacher’s exposition. A set of exercises from aphorism to fable and description, themselves increasingly complex narrative building blocks, led to the finished speech. At the final stage of declamation, the advanced boy learned a system of composition and delivery of mock deliberative and legal speeches.

What Bloomer does not specify is that this describes the educational career of a child who was a member of the elite. Works by writers like Quintilian, on whom Bloomer is leaning here, were written by the elite for the elite; they were not interested in describing the education of the sub-elite: as Reference Sigismund-Nielsen, Grubbs and ParkinSigismund-Nielsen (2013: 289) says, ‘[w]e meet freeborn children from the lower classes very infrequently in our sources. They were simply not interesting enough’.Footnote 5

Nonetheless, as we have established, it is clear that literate education could be available to the sub-elite (see also Reference Mullen and BowmanMullen and Bowman 2021: 61). Slaves could be taught in a paedagogium in their owner’s villa; slaves of the imperial household were taught in the Paedagogium on the Palatine – presumably often to a high level (Reference Sigismund-Nielsen, Grubbs and ParkinSigismund-Nielsen 2013: 296; although note the scepticism of Reference HarrisHarris 1989: 247–8). Scribes, whose work will form much of the data used in this study, clearly were educated in some fashion – and, as I shall show, in a fashion that in some respects at least was different from that of non-scribes – but we know very little about how they were trained (Reference MorganMorgan 1998: 32).

Likewise, there appears to have been some literacy education that took place in the army, perhaps for scribal purposes (see pp. 273–6), perhaps for soldiers more generally;Footnote 6 the tendency for letters written from and to Vindolanda to end with a greeting in a different hand from that which writes most of the letter suggests that some level of literacy among non-scribes was not uncommon. Reference HarrisHarris (1989: 253–5) suggests that literacy was much higher among legionaries than auxiliaries, but at least some auxiliaries could write, as demonstrated by the letters of Chrauttius from Vindolanda (Tab. Vindol. 264 and 310). Chrauttius will have been a Batavian or Tungrian auxiliary, and probably learnt a non-standard version of Latin in the army, perhaps showing some influence from his first language (Reference AdamsAdams 1995: 129–30), but is capable of writing a greeting formula.

Similarly, Reference Bowman and ThomasBowman and Thomas (1994: 74) suggest that the military reports with the heading ‘renuntium’ were written by the optiones making the report themselves, on the basis of the different hands of the writers. Reference AdamsAdams (1995: 102–3) has argued that the appearance of debunt ‘they ought’ in place of standard debent suggests that the exemplar on which these reports are based was also written by a non-scribe (perhaps also one of the optiones). He observes that this provides evidence of different degrees of education among the writers at Vindolanda: ‘[t]he renuntia thus give us an intriguing glimpse of a social class (probably that of the optiones) who regularly used the substandard form debunt, yet were literate’ (Reference AdamsAdams 1995: 131; emphasis in the original).

Further evidence of education at Vindolanda comes from lines of Virgil, possibly Catullus, and pseudo-Virgil (Tab. Vindol. 118, 119, 854 and 856), which were presumably produced for writing practice, although the ‘literary’ hands used are different from the usual scribal scripts. The editors suggest that 118 may have been the output of children of the prefect Flavius Cerialis, although there is no evidence of such a connection for 854 and 856.Footnote 7

It might be assumed that the education undergone by sub-elite members of society largely followed the same pattern as that described by Bloomer above, except that education stopped at some earlier point in the process – exactly at which stage might depend on the resources and aims of the child’s parents, on what teaching was available or other factors. To some extent, this is probably true; in the context of learning Greek in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt, Reference MorganMorgan (1998: 56–7) finds that papyri and other writing materials containing learning exercises and school texts have a different geographical distribution, with letters and alphabets widely scattered, including in villages, as are wordlists and literature, while scholia, rhetorical exercises and grammatical texts are far more restricted, especially to more urban areas:Footnote 8 she concludes, ‘[i]t looks rather as though the number of people in Upper Egypt whose education progressed as far as learning grammar and rhetoric was a very small proportion of those who acquired some basic literacy and read some literature’ (Reference MorganMorgan 1998: 57).

However, we should be careful of making too many assumptions along these lines: even if we assume the Egyptian situation is representative of learning elsewhere in the empire, we can seldom identify any clues about the social background of those using these materials, so it is possible that they still largely reflect the education of a fairly small elite.Footnote 9 Moreover, Reference MorganMorgan (1998: 67–73) has emphasised, again on the basis of the Egyptian Greek material, that the process by which children were educated was less a curriculum whereby everyone studied the same thing, but some people dropped out earlier than others, but rather a system involving certain ‘core’ exercises and texts, and a much wider ‘periphery’ whose contents were heterogeneous and depended on the choice of the teacher (and presumably other factors, such as access to texts). Morgan includes in the ‘core’ the kind of basic literate education that to some extent this book focusses on:

[e]verybody, so far as we can see, learned to read and write through reading and writing letters, alphabets and words, though syllabaries may not have been so popular. It is plausible to suppose that everyone read and copied gnomic sayings … It seems likely that Homer was very widely read, at least up to the end of the Roman period. Beyond these, what our survivals represent is less a curriculum than a free-for-all.

It makes sense that learning to read and write should be at the core for everyone, since very basic literacy is perhaps open to less variation than other types of education.Footnote 10 But the periphery might have been very different from what Morgan finds in Egypt, depending on the kind of use that literacy was to be put to. For example, shorthand, which is used in a number of texts at Vindolanda (Tab. Vindol. 122–6), was presumably not part of the standard educational system but was a speciality of those who were being educated as scribes or secretaries. And even at the level of the core, some variation existed: as already noted, syllabaries seem to be used less than other learning materials, in Egypt at least. And Quintilian (Institutio oratoria 1.1.26–32) mentions various approaches to learning to read and write of which he approves (ivory letter shapes to play with) or disapproves (learning the names and order of the letters before their shape; putting off the most difficult syllables; haste in moving on to pronouncing words and sentences).

As we shall see, there might also be variation as to what spellings a teacher might favour: they could be conservative or innovatory. The teachers themselves might also be of higher or lower literacy levels, have access to more or fewer resources, or even make greater or lesser effort. It is not unreasonable to suppose that, on the whole, the cheaper the teacher, the less they might have to impart and the less enthusiasm they might have to impart it. The contexts in which literate education took place might also have varied significantly; both ancient and modern discussions assume that it is children who are learning to read and write, but again, the Vindolanda tablets might provide an exception, if we assume that soldiers like Chrauttius learned to write only in the army, and hence presumably as adults. Another example of learning taking place after childhood comes from the tablets of the Sulpicii of Puteoli, where the Claudian letter Ⅎ in place of <u> for /w/ is found in TPSulp. 5 (by a scribe), 27 (non-scribe), 32 (scribe), 48 (both scribe and non-scribe), 77 (non-scribe) and 101 (scribe), mostly in the names of the consuls Vitellius and Vipstanus, but once in uenalium ‘for sale’ (77) and once in uadimonium (5). All of these tablets are from AD 48 (apart from 5, which is undated) and reflect the introduction of the Emperor Claudius’ new letters (on which, see Reference OliverOliver 1949). Clearly, some scribes and non-scribes alike had heard about and adopted this new letter, at least for the formal context of consular dating. Scribes in the army and elsewhere might also have received additional training, on top of whatever literacy skills they arrived with. And much of this assumes some kind of formal education, with a paid teacher: some may have learnt informally, from their parents, friends or peers, in which case the process might have been quite different, and presumably less systematic.

It does seem likely that scribes must have received some kind of education for their role. The fact that the spelling of the scribes in the tablets from Pompeii, Herculaneum and Vindolanda contains so few substandard features in itself implies a certain degree of homogenisation amongst these groups, which might be due to specific education (perhaps in the form of top-up training). However, it is also possible that people who became scribes were more likely to have already received a high-quality education in standard spelling. As we shall see, the enquiries in Parts I and II will reveal other ways in which scribes show homogenisation in spelling that implies a process of education specifically for scribes.

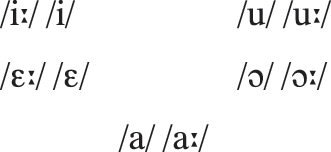

As important as the question of what was taught, and how, in different contexts is how well it is taught (or, since teaching is at least a two-person process, learnt). That is, the difference in educational content when it comes to spelling might not be very great between those who are well taught and those who are badly taught; the major difference might be their ability to use what they have been taught consistently according to the canons of the elite standard. For example, two writers may both have learnt that the digraph <ae> is used to spell certain words which contain the vowel /ɛː/; one of them consistently remembers which words contain <ae>, while the other remembers only some words or only remembers some of the time, and the rest of the time uses <e>, or hypercorrects by using <ae> in words for which the standard spelling requires <e>. In this case, the two writers have received the same educational content (existence and use of <ae>) but not the same quality of education. One could imagine yet another writer whose education has been so basic that they were simply taught the names and values of the individual letters corresponding to the sounds in their idiolect; this writer would therefore never have learnt the existence of <ae> and will always write <e> for /ɛː/.Footnote 11 Here this has been a difference in content as well as quality.

This distinction allows us to be more precise in our examination of whether the content of the orthographic education which was received by elite or sub-elite, or standard and non-standard spellers, was much the same, or not. If it was not, ‘old-fashioned’ or otherwise non-intuitive features such as apices and i-longa will appear only in the writing of elite or standard spellers; if it was, we should expect to find old-fashioned spellings in both elite and sub-elite writings, by both standard and substandard spellers: any differences in the orthography of these categories will then be ones of consistency or correctness, reflecting quality of education rather than content.

Defining ‘Old-fashioned’ Spelling

A good example of the complicated issues involved in identifying ‘old-fashioned’ spellings is the letter of Suneros (CEL 10), from Oxyrhynchus, dated to the Augustan period. We find the following features:

<ei> for /i/ < /iː/ by iambic shortening in tibei for tibi ‘to you’, and for /i/ in uocareis for uocāris ‘you will have called’ (in error, since the /i/ in the final syllable was never long, but presumably due to confusion with the perfect subjunctive uocārīs).

<e> for /iː/ (deuom for dīuum ‘of the gods’).

<xs> for <x>: adduxsit for addūxit ‘(s)he brought’, Oxsyrychitem for Oxyrhynchitem, maxsuma for maxima ‘greatest’.

<u> for /i/ before a labial: maxsuma for maxima ‘greatest’.

<q> for /k/ before <u>: qum for cum ‘when’.

<uo> for /wu/: uolt for uult ‘wants’, deuom for dīuum ‘of the gods’.

The editor Cugusi describes <ei> as a ‘sign of antiquity’ (‘segno di antichità’) and <uo> in uolt as an ‘archaising spelling’ (‘grafia archaizzante’) but for deuom notes that the ending ‘-om continued in use more or less to the end of the Republic’ (‘-om ci porta pressappoco alla fine della Repubblica’), describes <q> as ‘probably already in this period a “scholarly” spelling’ (‘probabilmente già in questo periodo grafia “scolastica”’), does not consider <xs> old-fashioned, and does not comment on <u> in maxsuma. He sees <e> in deuom as due to a confusion between /eː/ and /iː/ found in inscriptions (for slightly more clarity here, see also Reference CugusiCugusi 1973: 667). Reference AdamsAdams (2016: 208–9) says that Suneros ‘uses the old spelling tibei, and deuom is archaising on two counts.Footnote 12 Vocareis is a false use of orthographic archaism’. However, on the whole he takes a nuanced approach, emphasising that use of <u> continued into the first century AD, and that ‘[s]pelling reform does not take place overnight, and personal preference was a factor’ (Reference AdamsAdams 2016: 205).

As I shall show in the rest of this book, the ‘old-fashioned’ nature of these spellings is overemphasised by Cugusi and even by the more careful Adams. Even leaving aside the question of when in the Augustan period the letter was written (since habits probably changed a fair amount between 31 BC and AD 14), most of these spellings were still in fairly common usage at that time. This is the case for <ei> for /iː/ (Chapter 3); /wɔ/ had become /wu/ probably not much earlier in the century, and <uo> was still the more common spelling, although a move to use <uu> in official orthography does seem to be visible (Chapter 8). The use of <u> for <i> in maxsuma is still found in the first century AD in high-register texts but was perhaps moving out of the standard (Chapter 6). As for <xs> (Chapter 14) and <q> before /u/ (Chapter 12), these were always minority usages in the Republic but were beginning to lose favour in official orthography of the time; their use was perhaps not particularly striking in the context of an informal letter. The use of <e> in deuom may reasonably be considered old-fashioned (Chapter 3). On the whole, Suneros was perhaps a conservative speller (as well as a substandard one),Footnote 13 but most of his spellings are not archaic for the time.

In fact, despite the frequency with which terms such as ‘archaising’ or ‘old-fashioned’ are used, as with the letter of Suneros, to describe the spelling of a given document, defining them is surprisingly difficult, not least because there are several ways in which a spelling could be said to fall into such a category. The least useful definition is that which compares the spelling of a text with the kind of idealised, abstract and anachronistic notion of ‘standard’ Latin spelling that appears in editions of Latin literary texts and often also in inscriptional texts (including in the large online corpora).

Where the spelling feature in question represents a phoneme or series of phonemes which have undergone change in the history of Latin, it is possible to define ‘old-fashioned’ against this sound change. Thus, for example, once the diphthong /ɛi/ developed to /eː/ around the middle of the third century BC, the spelling <ei> could be considered ‘old-fashioned’ relative to <e>, and likewise once /eː/ had become /iː/ around the middle of the second century, the use of both <ei> and <e> could be considered old-fashioned relative to <i>.

Such a definition proves rather unhelpful, in a number of ways. In the first place, it ignores the fact that spelling takes time to catch up to phonological change (if it ever does): as we shall see, the use of <ei> and <e> demonstrably continued long after the relevant sound changes took place, but only after a certain time will their use have been considered old-fashioned. Secondly, under this sound-change-based definition of ‘old-fashioned’, it would be necessary to consider the continued use of <ae> to represent /ɛː/, the result of monophthongisation of the diphthong /ae̯/, old-fashioned from the point at which the sound change first took place.Footnote 14 But this definition fails to identify the difference, at least under the empire, between (correct) use of <ae>, which was simply the standard spelling – and whose absence would mark out the writer as undereducated – and use of <ei>, whose absence would not have the same effect (for more on this, see 50–57). Lastly, many of the features called ‘old-fashioned’ are not the result of sound changes, for example use of <xs> beside <x>, or <k> and <q> beside <c> to represent /k/. Identification of ‘old-fashioned’ spellings only with regard to sound change will therefore not help us with these cases.

So the definition of ‘old-fashioned’ needs to be usage based: spellings are ‘old-fashioned’ when they are no longer part of the core repertoire of standard orthography. This is not to say that they are necessarily substandard; simply that their use is not necessary for a writer’s orthography to be accepted as hewing to the educated standard (on the use of the terms ‘standard’ and ‘substandard’, see pp. 15–18). Depending on the context, and on the status of individual features, their usage may have made the writer seem to readers to be highly educated, conservative, idiosyncratic, fuddy-duddy or any number of other effects which it is difficult or impossible for us to pin down.

Taking these issues into account, I adopt three methods of assessing whether spellings were ‘old-fashioned’. Firstly, I have considered evidence from the writers on language whose works are dated more or less to the period being considered in this book (i.e. from the first to the fourth centuries AD). For more information on these authors, see pp. 37–9. These authors sometimes tell us (relatively) explicitly of their view on the currency of a particular spelling; even when they do not directly provide us with this information, the very fact that they mention something suggests that its existence was relevant to their intended audience.

There are, however, several issues that we must be careful of when dealing with this kind of information. The tradition of writing about language was tralaticious; its audience was also primarily interested in the reading of works of literature often dating from several centuries previously. The effect of these characteristics might be to foster mention of orthography which was very highly archaic by the time of the writer – perhaps not at all or barely used by anyone at the time.

Furthermore, different writers might have different attitudes towards orthography, preferring either more modern or more old-fashioned spellings, which may lead us to misanalyse the ‘old-fashionedness’ of particular orthography. In some cases the authors tell us explicitly about their approach; for example, Quintilian paints himself as (somewhat) in favour of more modern spelling, at least insofar as this reflects contemporary speech:

ego, nisi quod consuetudo optinuerit, sic scribendum quidque iudico, quomodo sonat. hic enim est usus litterarum, ut custodiant uoces et uelut depositum reddant legentibus. itaque id exprimere debent, quod dicturi sumus.

For my part, I think that, except for what is maintained by tradition, we should write as we speak. Because this is the purpose of letters: to represent sounds and, as it were, to echo what has been put down to their readers. So they ought to express what we say.

Lastly, it must be remembered that, while the writers on language had different backgrounds and audiences, they were writing for the (children of) the elite, or their teachers (or at least for those who had the resources to aim for elite status for their children). Consequently, their claims about the status of particular spellings are not necessarily likely to represent the habits of the sub-elite. Indeed, as Reference Biddau, Ferri and ZagoBiddau (2016: 51–2) observes, we cannot be sure that anyone at all shared a writer’s view.

The second method is to investigate the spelling of ‘official’ inscriptions emanating from and concerning the imperial (and perhaps local) elite and legal system, or of other texts known to be written by members to the social elite, on the basis that this represents standard orthography, and that spellings which have fallen out of use here are consequently ‘old-fashioned’. As with looking to the statements of the writers of language, this has the effect of privileging the elite over the sub-elite in defining the standard (although this is not in itself necessarily incorrect, since the development and imposition of a standard orthography is often a top-down process).Footnote 15 It is also less easy than it sounds, since there was not one genre of ‘official’ inscriptions: it is often claimed, for example, that legal texts continued certain spellings for longer than other kinds of texts. Should we, then, discount legal texts? And what, if any, other distinctions should be made? While these are interesting questions, they are not the focus of the present investigation, nor is there the space to do a thorough investigation of ‘official’ orthography across the whole of the chronological span that I am considering. Consequently, I do not draw distinctions between the different types of ‘official’ inscriptions, and I only treat them separately from the overall picture of Roman epigraphy as a whole mentioned in the following paragraph when it seems particularly relevant.

My final method of identifying ‘old-fashionedness’ in spellings has been to carry out searches among the massive epigraphic corpus collected as the EDCS, which allow me to roughly identify the frequency of a particular orthographic feature. For most features I have only carried out searches for the whole period of the first to fourth centuries AD, but where relevant, I have searched more precisely within that range to give an idea of changing usage over the period.

The information that these three methods provide on the status of a given spelling will not necessarily be consistent – just as a reader or writer’s view of how ‘old-fashioned’ a feature was may have varied depending on their education, social background or even personality, as well as the genre or register of text. This being the case, it is perhaps unsurprising that one result of the research carried out in this book will be, among other things, to cast doubt on the idea that there was a single, easily identifiable category of ‘old-fashioned’ spelling: this is not to say that use of a given orthographic feature was never seen as ‘old-fashioned’: simply that the point at which a spelling became ‘old-fashioned’ (if it ever did), varied across time as well as according to other variables. Nonetheless, I will follow common (modern) practice in continuing to refer to the particular type of optional spelling practice discussed here as ‘old-fashioned’ for now, while highlighting the problems and inconsistencies in using this term – and dropping the scare quotes. I will return to the question of the use of the term ‘old-fashioned’ in the conclusion (258–61).

Standard and Non-standard Spelling

In this book I will often talk about standard and substandard spelling (as well as old-fashioned spelling); indeed, one of my main claims is that old-fashioned spelling can be found in the writing of substandard spellers as well as those whose spelling is otherwise standard. The idea that Latin of the Classical period had undergone a process of language standardisation is widely held (see e.g. Reference RosénRosén 1999; Reference Versteegh, Adams, Janse and SwainVersteegh 2002; Reference AdamsAdams 2007: 13–17; Reference Clackson and HorrocksClackson and Horrocks 2011: 77–288; for an overview of bibliography, Reference NikitinaNikitina 2015: 3–9; and on the teaching of the standardised language in the later empire, Reference FosterFoster 2019).

However, recently scholars have emphasised the ways in which standardisation of spelling was not complete in the first century BC, and that orthographic variation continued to be found even in the writing of the highly educated elite, and in official inscriptions at least into the first century AD; see, for example, Reference ClacksonClackson (2015); Reference NikitinaNikitina (2015); Reference AdamsAdams (in press). Reference ClacksonClackson (2015) rightly emphasises both that the continued discussion of spelling variants in writers on language can be evidence of diversity in orthography and that there is still variation in spelling in official inscriptions of the first centuries BC and AD (based on the findings of Reference Fischer and CallebatFischer 1995). He concludes that

[w]ith so much variation in surviving documents, it is only possible to say which spellings are ‘correct’ and which are ‘incorrect’ with the benefit of hindsight. Spellings which were endorsed by later grammarians and became current in educational texts appear to us now to be the ‘correct’ spellings, and pass without comment. A Roman of the first century CE, however, may well have had different views, or may not have recognised a single ‘correct’ form … Quintilian is certainly aware that different spellings were possible, and is able to defend one spelling against another, but we must be wary of any idea that the spellings which are recommended by Quintilian, or indeed those found in the Res Gestae, are already ‘standardized’ at the date they are written. If the autograph manuscripts of Cicero had survived, we might have different views about what was considered ‘correct’. Writers, including the drafters of authoritative law-codes, did not yet share a set of codified norms, nor was any such set universally accepted. At the end of the first century CE, the process of standardization, at least in orthography, was not yet complete.

However, the fact that some variation was acceptable in spelling does not necessarily mean that there was no such thing as standard orthography at all. The types of spellings that Clackson and other scholars have focussed on as showing variation in the first centuries BC and AD are precisely those that are usually called ‘archaic’ or ‘old-fashioned’: Clackson mentions the spelling of pecūnia ‘money’ as pequnia, <u> for <i> before labial consonants, particularly in superlatives and ordinals, <uo> for <uu>, and use of <ii> to represent /jj/ in words like maior and eius. These are spellings which are often traced back to older writers, and indeed often associated with particular named great men of literature or politics. To some extent, and with variation depending on exactly how outmoded the older spelling came to seem, either the newer or the older spelling was acceptable: as Quintilian says, ‘on these matters, the school teacher should use his own judgement: for this ought to have the greatest weight’ ([i]udicium autem suum grammaticus interponat his omnibus: nam hoc ualere plurimum debet, Quintilian, Institutio oratoria 7.30). These are separate from ‘barbarisms’, which include ‘that vice known as a barbarism, of which examples are found everywhere, anyone can easily come up with instances of for himself, such as adding to any word a letter or a syllable or taking one away or replacing one with another or putting the right letter in the wrong place’ (illud uitium barbarismi cuius exempla uulgo sunt plurima, sibi etiam quisque fingere potest, ut uerbo, cui libebit, adiciat litteram syllabamue uel detrahat aut aliam pro alia aut eandem alio, quam rectum est, loco ponat, Quintilian, Institutio oratoria 5.10).

This kind of spelling is not acceptable: it is a uitium.Footnote 16 And it is this kind of spelling I will refer to as substandard: things like <b> for /w/, <e> for /ae̯/ or for short /i/, or absence of <h> in certain lexemes. Quintilian does not explicitly mention features like these at all, because it would be unthinkable for someone teaching pupils of the social level which Quintilian is writing about to introduce them as acceptable.Footnote 17 But subsequent scholars would do so, sometimes with great enthusiasm (as in the list of corrections known as the Appendix Probi; Reference PowellPowell 2007). These spellings reflect sound changes which have taken place in the Latin of their users (and often quite possibly of even elite speakers), but have not been admitted into the orthography of educated writers, and instead mark out their users as ill- or under-educated. Only very rarely do we find them in official inscriptions or those commissioned by the elite. Nor do we find them very much in some of the sub-elite texts which we will be looking at here, notably the tablets at Vindolanda, Pompeii and Herculaneum. This is particularly true of those texts and sections of texts which are written by scribes, who had presumably received an education which encouraged such lack of variation (for more on this, see pp. 271–6), but even in most texts which seem to have been written by non-scribes, differences in orthography are relatively minor, which makes texts which do diverge significantly from this norm, such as those of Octavius and Florus at Vindolanda (Tab. Vindol. 343, 643 respectively), and C. Novius Eunus in the tablets of the Sulpicii (TPSulp. 51, 52, 67, 68), all the more striking.

Structure of the Book

After the Introduction, the book consists of two parts, followed by a conclusion. The first part, consisting of Chapters 2–17, deals with old-fashioned spellings, starting with spelling involving vowels and moving on to consonants. In each case, I outline the circumstances that led to the spelling under discussion becoming old-fashioned and provide some context for the use of this spelling in the epigraphic record more generally, mostly in the form of investigation carried out by means of searches of the EDCS. I have not taken a uniform approach in this, both because different spellings require different focus on aspects of their use and because the nature of the database means that different types of search were possible for different spellings. Where relevant, I have also discussed what Roman writers on language had to say about a particular usage. I then provide data on, and discussion of, the usage of each particular spelling in the sub-elite corpora.

The second part, consisting of Chapters 18–24, focusses on two types of what might be considered diacritics: apices and i-longa, primarily in the Isola Sacra funerary inscriptions, the Vindolanda tablets and the tablets of the Sulpicii, since in these corpora their use seems to be restricted largely to stonemasons and scribes, and therefore provides insight into specifically professional writing traditions and education.

In the conclusion, I summarise my findings on these optional spelling features, focussing on three areas: what I have learnt about the use of old-fashioned spellings over time and in different social or geographic contexts; what this investigation tells us about education and social level, and in particular what we can learn about the education that scribes received; and what my research has revealed about sound change in Latin.

Methodology

Scribes, Writers and Authors

Writing in the ancient world was not necessarily a one-person job (Reference Clackson and ClacksonClackson 2011: 36–8). This is perhaps most obvious when we consider inscriptions whose creation required special skills, such as those carved in stone: very often the stonemason must have been working from a copy of the inscription written on some other material. This copy could have been written by the stonemason himself, but often it must have been written by someone else, perhaps by the person who commissioned the inscription or by a third party (or parties) who acted as intermediaries. However, the same is also true even for more ‘informal’ texts which were written on materials which ostensibly required less specialist skills than carving on stone. Very often, those writing on wax or wood tablets, papyrus or ostraca will not have been the author of the text, but scribes, presumably writing to dictation. The texts themselves often provide hints that this is the case. For example, the Claudius Tiberianus archive from Egypt early in the second century AD contains six letters from Claudius Terentianus to Claudius Tiberianus (see pp. 35–6), the main texts of which are written in four different hands.

Likewise, in the Vindolanda tablets it is quite common for a different hand to add a short message at the end of a letter, presumably in the handwriting of the author, whereas the rest of the letter is written by a scribe. This shows that the use of a scribe is not dependent on the author of a text being illiterate. On the chirographa in the TPSulp. tablets, which feature two versions of the same text, one written by a scribe and the other by the person taking out a loan, see pp. 28–30. The same may also be true for the writing of curse tablets; although the temptation is to take these texts, which often contain ‘vulgar’ features in spelling and language, as representing the unmediated language of their authors, we know that the creation of curse tablets could involve experts who sometimes used handbooks of formulas. It is not unlikely that these experts could also have been responsible for the writing of the texts, or that an illiterate author had someone else write the text (Reference GagerGager 1992: 5; Reference Clackson and ClacksonClackson 2011: 37; Reference McDonaldMcDonald 2015: 136).Footnote 18

Consequently, in this work I will distinguish between the author of a text (i.e. the person responsible for its wording) and the writer (i.e. the person who physically wrote the text); these may be the same person or different people; a text might have more than one writer (as in the case of the letters with a personal message at the end); and a text could have more than one author (e.g. as in the case of a curse tablet whose message is based on a template provided by an expert but with input from the person who commissioned the curse). I will use the term ‘scribe’ to refer to a professional writer who is writing a text on behalf of someone else.Footnote 19

One of the consequences of the frequent uses of scribes is that we cannot make any assumptions about the educational level of writers of texts on the basis of linguistic features other than spelling, and conversely that we cannot make assumptions about the education of authors on the basis of spelling (unless we have evidence to think that writer and author are the same person). For a good example, consider the letter of Chrauttius from Vindolanda (Tab. Vindol. 310), whose spelling is perfectly standard, but whose language is idiosyncratic (Reference AdamsAdams 1995: 129–30). This presumably reflects the fact that Chrauttius dictated the text to a scribe, who naturally used his own knowledge of orthography but faithfully wrote down what Chrauttius said without correcting it.

Finding and Counting Old-fashioned Spelling

In the first part of this book I examine the use of old-fashioned spellings in the corpora. In general, these have been under-studied, but even when they have been noticed, there are methodological issues that have not been addressed. For example, collecting the numbers of a particular feature in a writer’s output, or in a whole corpus where these are more unified generically or temporally, is not particularly useful when we do not also have the numbers of instances where this feature could have been used but has not – in other words, we need to know the frequency of a particular feature, not only the raw numbers.Footnote 20 This is particularly necessary given the range in the number of words and types of text, as well as the chronological and geographical range of the various corpora which I have used.

In the main, therefore, I have tried where possible to count each example of both a particular optional spelling and its standard equivalent. This is not always easy, because in some cases the standard spelling is so common as to make counting excessively burdensome. For instance, <ae>, the counterpart of old-fashioned <ai>, is extremely frequent because the diphthong it represented appears in many lexemes and in frequent endings, while <ai> is so rare as to be almost non-existent in the corpora. There would be no point in counting examples of <ae>. In these cases I will give an indication of the frequency of the standard spelling without providing precise numbers. In corpora where there is likely to be less homogeneity among the various writers, such as the letters or the curse tablets, I have usually only counted this type of feature when a given text or writer within the corpus also uses the old-fashioned variant.

I chose which old-fashioned features to examine on the basis of those that appear in the sub-elite corpora I have been using. Thus, for example, I do not discuss the use of <oe> for /uː/ because this spelling is not found.Footnote 21 I have also not included three types of spelling even though they appear frequently. These are absence of <h> when writing aspirated stops in Greek words and in Latin words to which a spelling with <h> became attached (like pulcher, triumphus etc.); use of <u> or <i> for <y> in Greek words; and use of unassimilated spellings (like conlabsum for collapsum). In the case of the first two it is true that absence of <h> and <y> could be seen as old-fashioned,Footnote 22 but it is also possible that their absence could reflect the inability of the writer to know where they should be used (since many speakers will have pronounced the aspirates as plain stops, and <y> as /i/ or /u/). Consequently, this absence can reflect substandard rather than non-standard spelling (which is of course relevant to education in itself, but this sort of spelling is not the focus of the present work).

As for the unassimilated spellings, their status within the Roman orthographical tradition is complicated. It seems that to a large degree their use was both optional – like old-fashioned spelling – and not deprecated in educated writing, with variation continuing throughout the imperial period, and inconclusive discussion of their use being frequent in grammatical works. The details of which unassimilated forms are favoured is extremely complex (see Reference NikitinaNikitina 2015: 71–106 for a discussion of their use in legal and ‘official’ texts of the first centuries BC and AD; and Reference AdamsAdams in press). In some cases, the unassimilated writing reflects an earlier stage of the language, but its continuation will be mainly due to the synchronic co-existence of forms which show the unassimilated consonant (e.g. the preposition ad and the preverb ad- in aduertō, admoneō, addicō etc.; collābor beside collāpsus) rather than to an unbroken educational tradition; consequently, I do not consider its use old-fashioned. In addition, I have not included features which exist on the borderline between phonology and morphology, such as third declension ablatives in -ī and gerundives in -undus vs -endus.

I have already discussed the problem of defining standard and old-fashioned spelling, and the necessity of doing so in terms of usage. Unfortunately, although scholars often refer to old-fashioned or archaising spellings, they seldom provide thorough evidence regarding not only when particular spellings first appeared but also when the older spelling stopped being used, along with a timeline suggesting at what point the innovatory spelling began to become the standard spelling. This is no doubt because such a task has been – and to some extent still is – extremely difficult. Handbooks of epigraphy or historical linguistics seldom provide this kind of thorough evidence, and collecting examples and identifying dates for them can take a long time. The huge amount of texts and metadata contained in, and searchability of, modern epigraphical online databases such as the EDCS, the Epigraphic Database Roma (EDR), the Epigraphic Database Heidelberg (EDH) and the Computerized Historical Linguistic Database of Latin Inscriptions of the Imperial Age (LLDB) can make a huge difference to this sort of research: for an example of a study which makes excellent use of these new resources, see Reference Mancini, Agostiniani and MarcheseMancini (2019), which is also discussed later (Chapter 14).

The primary online database that I have used is the EDCS. This is because it contains by far the greatest number of inscriptions, has the most useful search features and provides metadata of various sorts, links to other databases and scans of early editions. However, it also has significant limitations.Footnote 23 These basically boil down to two types of issue. The first is how to get the results that one wants from a search. Search is only possible on letter strings, meaning that in many cases a search for a particular string will produce output which includes many irrelevant sequences. While there is an ‘and not’ function, this is also limited to a single string, and so is not as useful as it could be. As a result, one has to be quite careful and precise about what strings one searches for, and even then it is often necessary to manually check the output and remove false positives.Footnote 24 Furthermore, at the time I was carrying out most of the research, in addition to the normal search function on the whole EDCS, there was also a ‘no solutions’ search, which in theory ignored examples of a particular string which are resolved abbreviations, and the unfortunately named ‘wrong spelling’ search. While these allowed some useful narrowing of the search parameters, the output produced by the different searches was rather unpredictable: for example, a given spelling was sometimes considered ‘wrong’ and sometimes not, and might turn up in the full search, in the ‘wrong spelling’ search, or both.Footnote 25

One way of getting round this problem is simply to download the entire corpus and run searches on it by other means than the web interface. However, without sophisticated programming knowledge which I lack, this is not necessarily easier, not least because the inconsistency is inherent in the way that the inscriptions have been inputted into the corpus itself. Thus, a given spelling is sometimes marked up using a notation <X=Y>, where X is the ‘correct’ spelling and Y the deviant variant, sometimes marked by an exclamation mark between brackets following the end of the word: (!), and sometimes not marked at all.

An example of the problems: looking for examples of arcarius, I searched for ‘arcari’ in the full search, with a date of ‘01 to 400’ (25/01/2021). This gave 90 results, which had to be manually checked. This resulted in 14 inscriptions containing the lexeme arcarius, including abbreviated and restored forms in which the sequence arc was actually attested; it also included 13 inscriptions containing the sequence ark. Although these instances of arkarius were all marked up in the output with the notation <c=k>, none appeared in the ‘wrong spelling’ search for ‘arkari’, which provided another three instances not included in the search for ‘arcari’. This seems to have something to do with abbreviations: all in the full search were ark(ari).

The second issue is that the readings, datings and other information provided by the database are not necessarily accurate,Footnote 26 and most inscriptions are anyway not provided with a date. Ideally, therefore, one would check all readings and datings of inscriptions containing a given spelling which has been found in a search of the database in the editions and other literature. However, given the frequency which many spellings of this type demonstrated, it became clear that such a task was simply not possible. For example, the searches required to find examples of <uo> for /uu/ produced literally thousands of results – many of these could be discarded relatively easily, but even this still took considerable time, and the subsequent work to check readings and datings took even longer. In the end, despite the dedication and initiative of Victoria Fendel, who helped to do this, and despite various shortcuts,Footnote 27 I came to the conclusion that such a task was simply not feasible within the bounds of the present project.

The work of myself and Dr Fendel on this front has fed into the discussion of the spellings <uo> for /uu/, <uo> for /we/ before a coronal, <qu> for /k/ before a back vowel, and <ai> for <ae>, but in the main I have taken a different approach. Where the numbers make it necessary, for a given spelling I have mostly restricted the searches in the EDCS to inscriptions within a relevant date range. Since, as already noted, the database does not provide a date for many (probably most) inscriptions, this means that these undated inscriptions, many of which are nevertheless relevant, are omitted from the results of the search. This should be borne in mind when comparing distribution of spellings in terms of numbers of inscriptions. The hope is that even with this loss of data, the distribution of dated spellings more or less represents the distribution across the whole corpus.Footnote 28

Different approaches to checking results have been adopted depending on the amount of data for a given spelling. In every case where I give a reference to an edition, the spelling has been checked against the edition. When giving numbers of inscriptions in the tens, I have checked the output to remove restorations and false positives, but have not usually checked against the editions; when the number of inscriptions reaches the hundreds, I have not even done this. On the whole, the smaller numbers are of old-fashioned spellings, while the larger numbers are of standard spellings, so there is probably a tendency for the standard spellings to seem even more common relative to the old-fashioned spellings than they really are.

In the collection of old-fashioned spellings from the corpora, I have not included readings which are highly doubtful or sequences of letters which cannot be understood. With regard to abbreviations and restorations I have taken a common-sense approach: I have not included cases such as Sex. for Sextus, since it does not rule out that the author might have used <xs> when spelling the word out in full, but I have included abbreviations like k. for castra. Naturally, I do not include spellings which are found only as restorations, but I do include cases like peq[u]nia, where we can be sure of what the missing letter is. All percentages are given as the nearest whole number.

The Sub-elite Corpora

In this book I use corpora as a way of indirectly assessing the type of education received by the members of the sub-elite in the Roman empire. The sub-elite can be defined straightforwardly as all inhabitants of the empire who were not ‘senators, the equestrian class, and the local governing class’ (Reference TonerToner 2009: 3). Such a definition of course obscures many important distinctions among the several tens of millions who occupied this position, including slave vs free (and vs freed), ‘affairistes’ vs ‘average workers’ vs labourers, women and men, urban vs rural, etc. (see e.g. Reference TonerToner 2009: 1–5; Reference Courrier and GrigCourrier 2017; Reference Grig and GrigGrig 2017: 18–21). Unfortunately, we cannot investigate the orthography of the texts in the corpora with as much granularity as we would like, but the corpora do allow some distinctions to be drawn, particularly scribes vs non-scribes (especially in the tablets of the Sulpicii and of Caecilius Jucundus from Pompeii, and at Vindolanda), and military vs non-military writers (in the form of the texts from the army at Vindolanda, Vindonissa, Dura Europos, Bu Njem, and the Claudius Tiberianus letters as opposed to the other texts).

I have chosen corpora in which it is a reasonable assumption that the majority of writers did not belong to the elite of the empire. In most of them we have a fair idea about the social status of the writers; in addition to scribes and soldiers, identifiable writers of the texts include slaves, contractors and praetorian guards, although there is seldom enough evidence to allow strong conclusions to be drawn about the type of education which these categories of person received. The major exception to this is the curse tablets, which often provide very little or no information about the writer of the text (who may or may not be different from the author). It is often implied that these are by definition written by members of the sub-elite: ‘they come to us largely unmediated by external filters; unlike ancient literary texts, they are devoid of the distortions introduced by factors such as education, social class or status, and literary genres and traditions’ (Reference GagerGager 1992: v).Footnote 29 However, as already noted (pp. 19–20), this is not necessarily the case.

We might assume that tablets with multiple substandard features were not written by a member of the elite, but, just as a high level of orthographic education does not imply a high social position, lack of success in achieving a high level of education does not necessarily rule out membership of the elite (at least as far as writing goes). However, there were relatively low barriers to entry in the creation of these texts, which were not, after all, intended to be read by the public. So where the author and writer were identical, there is at any rate no reason to assume that curse tablets were created more by the elite than the sub-elite; and professional writers of curses would have belonged to the sub-elite.

These ‘sub-elite’ corpora, then, predominantly include texts produced by sub-elite writers. But they do not necessarily only include texts written by the sub-elite. The Vindolanda tablets include letters, (parts of) which are written by prefects of the cohort and their wives, who probably belonged to the equestrian ranks; the corpus of letters includes a number which emanate from the upper levels of the civilian or military bureaucracy; and, as noted above, there is no reason why we should rule out the elite as authors or writers of curse tablets, for example. Where we can identify members of the elite within the corpora, their usage provides a useful point of comparison with the conclusions drawn on the basis of the other texts.

My choice of corpora is obviously skewed by what has survived the vicissitudes of history, as well as what was available to me in good editions (somewhat more restricted than usual during the pandemic, due to lack of library access for part of the time). Within these constraints, I have used corpora which are internally coherent in terms of place, time, social circumstance or genre, while providing coverage of the geographical and chronological extent of the Roman empire.

The Tablets of the Sulpicii (TPSulp.)

The archive of the Sulpicii (Reference CamodecaCamodeca 1999) consists of 127 documents written on wax tablets found in 1959 around 600 metres outside Pompeii. Their wax, and the writing upon it, was remarkably preserved along with the wooden sides and backing. The tablets make up the archive of a family of bankers, the Sulpicii, of whom the most frequent members identified are C. Sulpicius Faustus, his freedman C. Sulpicius Cinnamus, and, in the 60s AD, a C. Sulpicius Onirus. They provide the records of a number of types of transactions such as loans, agreements, oaths and legal cases (and in one case a letter). They often contain consular dates demonstrating a range from AD 26 to 61 (but primarily between 35 and 55). The tablets mostly refer to business taking place in Puteoli, but with instances at Capua, Volturnum and Rome.

The documents generally consist of two or three tablets connected together. In the case of the diptychs, this provides an internal pair of wax surfaces (as it were, pages 2 and 3) and an external pair of wooden surfaces (pages 1 and 4). Most of the documents consist of two versions of the text; in the diptychs, one is found on the inside pages, and one on the outside pages (in this case in ink on the wood), along with the names and symbols of the witnesses. In the triptychs, the additional wax surface (page 5) hosted the second version of the document. In addition, some have an index, a brief description of the contents for convenient identification, either inked or scratched into the wood.

There is a distinction to be made between two types of documents: testationes and chirographa, which pertain to different types of legal records (for a breakdown of which, see Reference CamodecaCamodeca 1999: 34 fn. 103). In the first type, which are generally written in the third person, we can assume that all parts of the tablet were written by a scribe or scribes, although not necessarily by the same scribe. Chirographa, which formed a contract between two people and are written in the first person, have the inner version written by the other party to the agreement. These often begin scripsi, implying that they are indeed written by the other party, and that this section is in their actual handwriting is shown by a couple of further pieces of evidence. The strongest piece consists of instances in which one person has written on behalf of another because, we are told, the party to the contract is not literate (TPSulp. 46, 78, 98); if it were standard practice for the contract to be written by a scribe, this information would not need to be included. Likewise, the Greek chirographum in TPSulp. 78 and the one in Latin but using the Greek alphabet (TPSulp. 115) presumably reflect the fact the writers could not speak or write Latin respectively, but, being literate in Greek, were required to write themselves rather than relying on a scribe. In addition, there are a number of instances where the spelling of the inner writing differs significantly from the more standard spelling on the outside, implying that a different person wrote the inner and outer versions of the text;Footnote 30 of course, it would be possible that this writer was also a scribe, although if so not a very well-trained one. I assume that all testationes and all of the writing on the exterior of tablets or on page 5 of a triptych are the product of scribes (though more than one scribe may have written the relevant parts), while all the writing on the interior pages of chirographa are written by individuals who were probably not professional scribes.Footnote 31

The Tablets of Caecilius Jucundus (CIL 4.3340)

L. Caecilius Jucundus was an argentarius operating in Pompeii; 153 wax tablets from his archives are preserved and were published by Zangemeister as CIL 4.3340. Almost all of these pertain to his activity as an intermediary between buyer and seller in an auctio; a small number record money paid to the city of Pompeii for the rental of various goods belonging to the city. Apart from two tablets dated to AD 15 and 27, the former referring instead to L. Caecilius Felix, perhaps a relative of Jucundus and his predecessor in the business, all the tables in which the date is preserved come from between AD 52 and 60.

The records of the transactions follow three different structures: they may be written entirely in the third person, with both interior and exterior copy written by scribe; or one part is written in the first person, by the seller him- or herself or a deputy (as demonstrated by the substandard spelling in the exterior text of 26, 38, 40 and 45, and the use of the Greek alphabet in 32). In these tablets, either the interior is written in the third person by a scribe, with the exterior in the first person, or the tablets take the form of a chirographum, with two copies of the contract written in the first person, with the interior written by an individual and the exterior by a scribe, as in the chirographa of the tablets of the Sulpicii (for an apparent exception to these structures, see p. 178 note b). On the tablets and their contents, see Reference AndreauAndreau (1974: 14–25, 311–12), Reference MeyerMeyer (2004: 149–50).

The Tablets from Herculaneum (TH2)

Some 160 or so wax tablets were also found in Herculaneum during excavations in the 1930s and subsequently, containing similar financial records to those of the Sulpicii and Caecilius Jucundus, and dating from 8 BC to AD 75 (although primarily to the last twenty years of this range). The heat they were subjected to, resulting in the carbonisation of the wood, has meant that they have physically survived better since excavation than the tablets of the Sulpicii; unfortunately it also resulted in the melting of the wax, meaning that in general only those parts written in ink directly onto the wooden surface of the tablets remains, primarily witness lists but also sometimes a third version of the interior and exterior copies as in the other tablets. Reference CamodecaCamodeca (2017a) gives 42 of these texts, previously published in a variety of venues, in anticipation of a complete edition.Footnote 32

The Tablets from London (WT)

A total of 405 waxed tablets used for writing were discovered in an archaeological excavation in the City of London between 2010 and 2014, of which 181 – all those which showed traces of text – were published by Reference TomlinTomlin (2016), along with two stylus labels (only one inscribed) and two wooden tablets written on with ink. Almost all date from the second half of the first century AD to the early second century, or are undated, with four coming from the second century after AD 125, and one from the third century. They include correspondence, financial or legal documents, accounts and other miscellaneous genres.

The context of the texts is sub-elite: those mentioned include coopers, brewers, transport contractors, businessmen, slaves, decurions, a bodyguard of the governor and auxiliary soldiers (a probable equestrian prefect of auxiliaries, Classicus, is named in WT 33); not all of them were written in London, and some letters were definitely sent to London. There is some evidence of a scribe as the writer of at least one text (WT 29), who appears to have got the author’s name wrong and corrected it.

The Vindonissa Tablets (T. Vindon.)

From AD 16 or 17 to 101, three legions, along with auxiliaries, of the Roman army were consecutively stationed at an army camp at Vindonissa (modern-day Windisch in Switzerland). From this camp have emerged a collection of 65 wax tablets whose wooden backing shows readable traces of writing, and which have been edited by Reference SpeidelSpeidel (1996). These date from around AD 30 to 101, and consist largely of letters, but also other genres of text, including a record of discharge from the army, a receipt, a promissory note and a contract.

The Vindolanda Tablets (Tab. Vindol.)

The Roman fort at Vindolanda (near to what would become Hadrian’s wall) preserves a large collection of texts written in ink on wooden tablets from between AD 85 and 130, the majority from about a decade starting around AD 92. Many of these are letters, either sent from or received at Vindolanda, but they also include other genres, including literary texts, reports and lists. The auxiliary cohorts who occupied the fort in this period were Tungrians and Batavians, (presumably) mostly Germanic speakers from Gallia Belgica and Germania. Germanic and Celtic names are frequent in the texts. The cohorts were led by equestrian prefects, of whom we have correspondence of Julius Verecundus, prefect of the First Cohort of Tungrians, and Flavius Cerialis, prefect of the Ninth Cohort of Batavians, along with that of the latter’s wife Sulpicia Lepidina.

It is presumed that the majority of the texts are written by scribes: this is most clear from the letters, where the author often writes a brief message in their own hand at the end (for other evidence, see p. 226 fn. 3); it is also suggested by the high level of consistent standardness in the texts. There are, however, some texts whose writers are probably not scribes, which will be discussed as appropriate in the rest of the book.

The Vindolanda tablets were published in Tab. Vindol. II (Reference Bowman and ThomasBowman and Thomas 1994), III (Reference Bowman and ThomasBowman and Thomas 2003) and IV (Reference Bowman, Thomas and TomlinBowman, Thomas and Tomlin 2010, Reference Bowman, Thomas and Tomlin2011 and Reference Bowman, Thomas and Tomlin2019). Tab. Vindol. II was digitised as a website called Vindolanda Tablets Online,Footnote 33 and both Tab. Vindol. II and III were also available at another site called Vindolanda Tablets Online II,Footnote 34 which along with the printed editions, I used in this book. For the sake of completeness I give their URLs in the footnotes. However, both sites are no longer directly accessible, and all the Vindolanda material is available on RIB Online.Footnote 35

The Bu Njem Ostraca (O. BuNjem)

The garrison at Bu Njem in Libya, ancient Gholaia, called Golas by the Romans, has left behind a corpus of documents consisting of 146 ostraca (not all with readable writing on them) and five fragments of wall plaster with writing on them, published by Reference MarichalMarichal (1992). The ostraca which give information as to the date come from between AD 253 and 259. The garrison was abandoned shortly after 259. On the basis of an analysis of the names, Reference MarichalMarichal (1992: 65) concludes that the soldiers are auxiliaries, of which the great majority were recruited in Africa. The documents cover a range of genres, such as receipts, reports and correspondence, with some authors being of high rank (e.g. O. BuNjem 75, sent by a procurator), but this is not the case for the majority (see also Reference AdamsAdams 1994 on the background and language of the Bu Njem ostraca).

Papyrus and Parchment from Dura Europos (P. Dura)

Dura Europos, in the province of Syria (later Syria Coele), was captured in AD 164 or 165 under the Emperor Lucius Verus and was eventually taken by the Persians in 256. From at least 208, it was garrisoned by a cohort of auxiliaries, the Cohors XX Palmyrenorum, and practically all of the texts in Latin come from an archive which was left behind when the room in which they were contained was abandoned in order to allow building works connected with the siege of 256. They include a number of official letters, ‘morning reports’ (daily reports of the status of the cohort and its personnel), rosters and lists of various sorts, a collection of judicial decisions by a tribune (although only one is in Latin) and a festival calendar (the feriale Duranum). These date to the last fifty years or so of Dura’s occupation by the Romans. I have used the edition of Reference Welles, Fink and GilliamWelles et al. (1959), except for the letters, where I have followed the text as given by CEL 55–68, 70–80. I have included all texts found in the archive, with the exception of the feriale Duranum, since this official document did not originate at Dura (although of course it could have been copied there) and is likely to reflect the orthography of the authority from which it emanated.

Graffiti from the Paedagogium

The building known as the Paedagogium on the Capitoline hill was built in AD 92 and features a number of (mostly very) brief graffiti: the edition of Reference Solin and Itkonen-KailaSolin and Itkonen-Kaila (1966) provides 369, but some of these include only pictures rather than words, and some are in Greek. The graffiti themselves date to the second and third centuries AD. On the basis of the graffiti, the building seems to have been used primarily by slaves: many of the names that appear in the graffiti are characteristic of slaves, and some of them refer to their writers as slaves or having servile occupations. The corpus is not large, and does not provide much useful information, but it seemed inappropriate to exclude it because of the likelihood that this building was indeed the paedagogium of the imperial palace (Reference Solin and Itkonen-KailaSolin and Itkonen-Kaila 1966: 73–8; Reference Keegan and GeorgeKeegan 2012). Consequently, it could provide evidence for the kind of literate education which the management of the imperial house considered appropriate for its slaves.

Curse Tablets (Kropp)

Reference KroppKropp (2008a) provides a collection of 382 curse tablets in Latin from across the empire, dating from the second century BC to perhaps the fifth century AD, but with the majority coming from the first to fourth centuries AD. On the question of who was writing these texts, see pp. 19–20 and 27. I have only included in my data words clearly recognisable as Latin, in the Roman alphabet – words in the Greek alphabet (whether Greek or Latin), and magic words, have been omitted.

Letters (CEL)

CEL is a corpus of non-literary Latin letters preserved on papyrus, tablets and ostraca, dating from the first century BC to the sixth century, although the majority come from the first four centuries AD. They are from across the empire, although there is an emphasis on Egypt as the primary place where papyrus was preserved. The authors include a range of social circumstances, although the army is particularly well represented. In fact, a large number of the letters in CEL come from the other military corpora (Vindonissa, Vindolanda, Dura Europos, Bu Njem), and I have not included them a second time. Since the remaining letters mostly do not belong to large collections of the same origin, and given their general heterogeneity (other than genre), I have mostly not felt it useful to treat the letters as a single corpus for the purpose of statistics, and discuss them individually.

There are two major exceptions to this. The first is the ostraca from the wâdi Fawâkhir in Egypt, which probably date to the first century AD (CEL 73–80). CEL 73–78 appear to be written by the same person, presumably the author Rustius Barbarus; whether he is also the author of 79 and 80 is uncertain. These ostraca contain many substandard spellings (e.g. que for quae, tan for tam, scribes for scribis, uirdia for uiridia, mittes for mittis, stati for statim, debio for debeō, habio for habeō, exiut for exīuit, sepius for saepius, c̣ọḷic̣los and coli[clos for cauliculōs, casium for cāseum, lintiolo for linteolō, redda for reddam, massipium for marsūpium).

The second is the cache of papyrus letters from Karanis in Egypt, dating to the early second century AD.Footnote 36 The letters are either sent from Claudius Terentianus to Claudius Tiberianus (P. Mich. VIII 467/CEL 141–471/146, and CEL 143) or from Claudius Tiberianus to another person (472/147);Footnote 37 CEL 148 is too fragmentary to identify the author. The authors are both soldiers, and it is often supposed that Tiberianus was the father of Terentianus; there are further letters written in Greek. Whether they were first- or second-language speakers of Latin is a matter of discussion (Reference NachtergaeleNachtergaele 2015). The letters are all written in different hands except for 468/142 and 143, and perhaps 470/145 and 471/146 (although Reference Halla-aho, Solin, Leiwo and Halla-ahoHalla-aho 2003: 249 doubts these last two belong to the same scribe on the basis of the difference in the orthography). In addition, Terentianus may have written the greetings or addresses in a different hand from the rest of the letter in 468/142, 470/145 and 471/146 (Reference Halla-aho, Solin, Leiwo and Halla-ahoHalla-aho 2003: 245, 250–1). Except for 472/147, all the letters contain substandard spelling, although to varying degrees, but also, as we shall see, old-fashioned spellings.

Funerary Inscriptions from the Isola Sacra (IS)

The necropolis on the Isola Sacra, between the ports of Ostia and Portus to the south-west of Rome, contains a large number of tombs and burials dating from the late first to the early fourth century AD. The corpus of inscriptions edited by Reference HelttulaHelttula (2007) contains 368 funerary inscriptions in Latin from the necropolis, almost all of which belong to the second to third centuries AD (I do not include the tiny number of non-sepulchral inscriptions, nor, obviously, those in Greek). The tombs commemorate, and were set up almost entirely by, members of the sub-elite, including many freedmen and freedwomen, slaves and freeborn (many of whom will have been the children of freedmen and -women), and including a range of occupations (for a useful sketch, focussing on a subset of the tombs, but representative of the whole corpus, see Reference Tacoma, Cascio and TacomaTacoma 2016: 138–41; on the predominance of freedmen and -women in funerary inscriptions, see Reference TaylorTaylor 1961, with reference to the Isola Sacra at pp. 120–2). Some of these were slaves or freedmen of the imperial household, and some were, moreover, clearly affluent, but they cannot be said to have belonged to the small elite defined as the senatorial and equestrian classes.

Writers on Language

I give here a very brief overview of the Roman writings on language referred to in this book.Footnote 38 I have looked for material in the major writers of the first to fourth centuries AD. In the discussion of <k> and <q> I have also included some relevant later writers, mentioned by Reference LindsayLindsay (1894: 6–7), without carrying out a thorough search. For more information on all except Quintilian, see the editions cited, and the useful summaries in Reference ZetzelZetzel (2018: 96–8, 231, 279–329). Where a text is quoted from another edition, but is also included in Grammatici Latini (GL; Reference KeilKeil 1855–80), I also provide a reference to GL. Texts are quoted as printed in the editions, except that I have changed v to u throughout, replaced capital letters at the start of sentences with lower case and used double quotes (“ ”) in place of various equivalent national conventions. I have made no attempt to make them consistent in other ways. In the translations I have not used brackets and slashes to distinguish phonemes from graphemes, since these are not concepts kept distinct by the authors. All translations are my own, except where noted.

L. Caesellius Vindex. Second century AD. His writings are known only from excerpts in Cassiodorus’ sixth century AD De orthographia, of which I use the text of Reference StoppacciStoppacci (2010), under the names Caesellius and L. Caecilius Vindex. To what extent either of these was actually written by Caesellius Vindex (see the contrasting comments of Reference StoppacciStoppacci 2010: clxvi–vii and Reference ZetzelZetzel 2018: 288), and whether they were altered before inclusion by Cassiodorus are uncertain.Footnote 39

Flavius Sosipater Charisius, Ars grammatica. Early 360s AD. Reference BarwickBarwick (1964).Footnote 40

Cledonius, Ars grammatica. Fifth century AD. GL (5.1–79).

L. Annaeus Cornutus. AD 20–65. His De enuntiatione uel orthographia is known only from excerpts in Cassiodorus’ sixth century AD De orthographia, of which I use the text of Reference StoppacciStoppacci (2010). These were not necessarily unchanged by Cassiodorus. An English translation is found in Reference Boys-StonesBoys-Stones (2018: 142–55), but he uses Keil’s (GL 7.147–54) text, which is sometimes quite different.

Curtius Valerianus. His work is known only from excerpts in Cassiodorus’ sixth century AD De orthographia, of which I use the text of Reference StoppacciStoppacci (2010). These were not necessarily unchanged by Cassiodorus. His date is uncertain (after the second century AD according to Reference ZetzelZetzel 2018: 288; fifth century AD according to Reference StoppacciStoppacci 2010: cxxxix).