Several of the Isola Sacra funerary inscriptions contain apices (see Table 31). The most important variable in the use of the apices is position in the text. Their main purpose is to emphasise the initial dīs mānibus formula (as noted by Reference ChristiansenChristiansen 1889: 12) and/or some or all of the names on the tomb (particularly the names of the deceased, or the person for whom the tomb is intended).Footnote 1 As will be discussed shortly, although the i-longa is mostly used differently, in some cases it also takes part in this usage. Thus in IS 69, there are apices on mánibus and on three out of four of the non-abbreviated parts of the name formulas of the two dead women, while in IS 70, which uses the abbreviation d. m. for dīs mānibus, there are two name formulas which each receive an apex on the only long vowel (which is not /i:/) in the formula. In some cases words modifying these names are also given apices.

Table 31 Apices in the Isola Sacra inscriptions

| Inscription | dis manibus | Name(s) of deceased | Name(s) of builder | Other words |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IS 69 | dis mánibus | Alfiáe M. f. Prócilláe | P. Sextilius Pannychianus | |

| IS 70 | d. m. |

| ||

| IS 72 | dís mánibús | P. Betileno Synegdemo | Betiliena Antiochis | |

| IS 79 | d.m. | Aphrodisiáe karíssimaé béne merenti | L. Suallius Eupór | |

| IS 97 | diìs m. (right side) | C. Nunnidius Fortunatus | Claudi Luperci | púrumFootnote a |

| IS 110 |

| filí | ||

| IS 128 | diìs mánibus | Iúliae L. f. Apollóniae |

| |

| IS 130 | d. m. | Antoniáe Tyche matrì optimáe | MMM Antoniì Vìtális, Capitó, Ianúárius fíliì | |

| IS 169 | dis manibus |

|

| |

| IS 195 | Ónesimé | Erós cónseru[ | ||

| IS 210 | d. m. |

| Ulpia | |

| IS 253 | d.m. |

| ||

| IS 309 | dìs mánibus | Murdiae Apelidi |

| |

| IS 314 | Ti. Plautị[ | agró | ||

| IS 360 | d.m. | ]li Eutychetis | ]odius Deúther |

a The apex is not printed by the editors, but is noted in the commentary and is clear in the photograph.

In the fairly long IS 253, the initial two name formulas do not receive an apex, but at the second mention of M. Antonius Vitalis an apex is used (on, unusually, an <i>). The two lines containing the name formulas at the start of the inscription are in larger letters than the rest of the text, so it is possible that these were already felt to be appropriately marked out, and not to require an apex.

Apart from IS 127, on which see directly below, out of 15 inscriptions containing apices, only 4 inscriptions (IS 97, 110, 169 and 314) place apices on words that do not fall into these categories. These apices are all on long vowels. The apparent disparities in these texts from the standard practice in the latter two are less stark than they may at first seem. IS 169 is the only inscription which contains the unabbreviated dīs mānibus formula and which does not place an apex on either of the words. However, the first line and most of the second, containing dīs mānibus and the first name formula, have been erased and rewritten. Since both of the other two name formulas in this inscription are given an apex, it is reasonable to suppose that the same would have been true of the first one, and probably also of dīs mānibus. In the case of IS 314 the inscription is extremely damaged and not much text remains, so it is impossible to know whether it would also have used apices on the dīs mānibus formula, or on some of the names as well.

IS 127 shows a markedly divergent, as well as highly enthusiastic, use of apices: the editors identify them as dividing words, indicating abbreviations, filling empty spaces, and indicating the accent. As to the accent position, I presume they refer to the small number of apices which appear above rather than between letters, on the initial letters of every word of the second line Źosimes q́uae úixit, and on tabelĺ(arius). I would analyse the use of apices in the second line as emphasising the name of the deceased (the first line is simply d.m.).

The distribution by vowels and diphthongs is remarkably even, including, unexpectedly, on <i>:

| aː | ɛ | eː | i | iː | ɔ | ɔː | u | uː | ae̯ | ɛu |

| 6 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

There is a weak tendency for the apex to be placed on long vowels: except for <u>, there are more apices found on the long version of each vowel than on the short; out of the 4 instances of non-abbreviated mānibus which bear the apex, all have an apex on the <a>, and only one (also) has an apex on the <u>; and some inscriptions (IS 70, 128, 309, 169, plus 314 and 253, in which only one apex is found) only use apices on long vowels. Also, all apices which are not on the dīs mānibus formula, on names, or on adjectives agreeing with names, are on a long vowel, although this may be a coincidence. But only 23/38 = 61% apices are on long vowels, with 8 being on diphthongs and 7 on short vowels. As we will see, this is a much lower rate than even the Vindolanda tablets or the tablets of the Sulpicii, both of which show a lower rate than the 75–77% in the Lyon and Vienne inscriptions examined by Reference Flobert and CalboliFlobert (1990). The position in the word is also evenly spread, with only 14/38 (37% plus 1 monosyllable) apices being on the final syllable (again, this is much lower than at Vindolanda or the tablets of the Sulpicii, which favour final syllables).

It seems pretty clear that in general the use of apices in the Isola Sacra inscriptions is for decoration/text structure rather than for the purpose of marking vowel length, although this may have been a secondary consideration, since some inscriptions only used apices on long vowels. IS 169 and perhaps IS 314 took a somewhat different approach, in which only long vowels were marked, even on words which are not part of a name or an attributive noun or adjective phrase – although even in IS 169, 2 out of 4 words with an apex are names.

We must remember that inscriptions from the Isola Sacra which contain apices are very much the minority. Nonetheless, the fact that there is a pattern in the use of apices in the inscriptions which contain them suggests some sort of educational tradition among the writers of these inscriptions, however broadly defined. We might think of a relatively formal tradition among those who were employed to compose funeral inscriptions or advise customers on their composition, a much looser tendency among some writers to reproduce what they find in looking at other funerary inscriptions, or even a habit passed along by the stonemasons of tombstones themselves, adding apices on their own initiative at the time of engraving the texts.

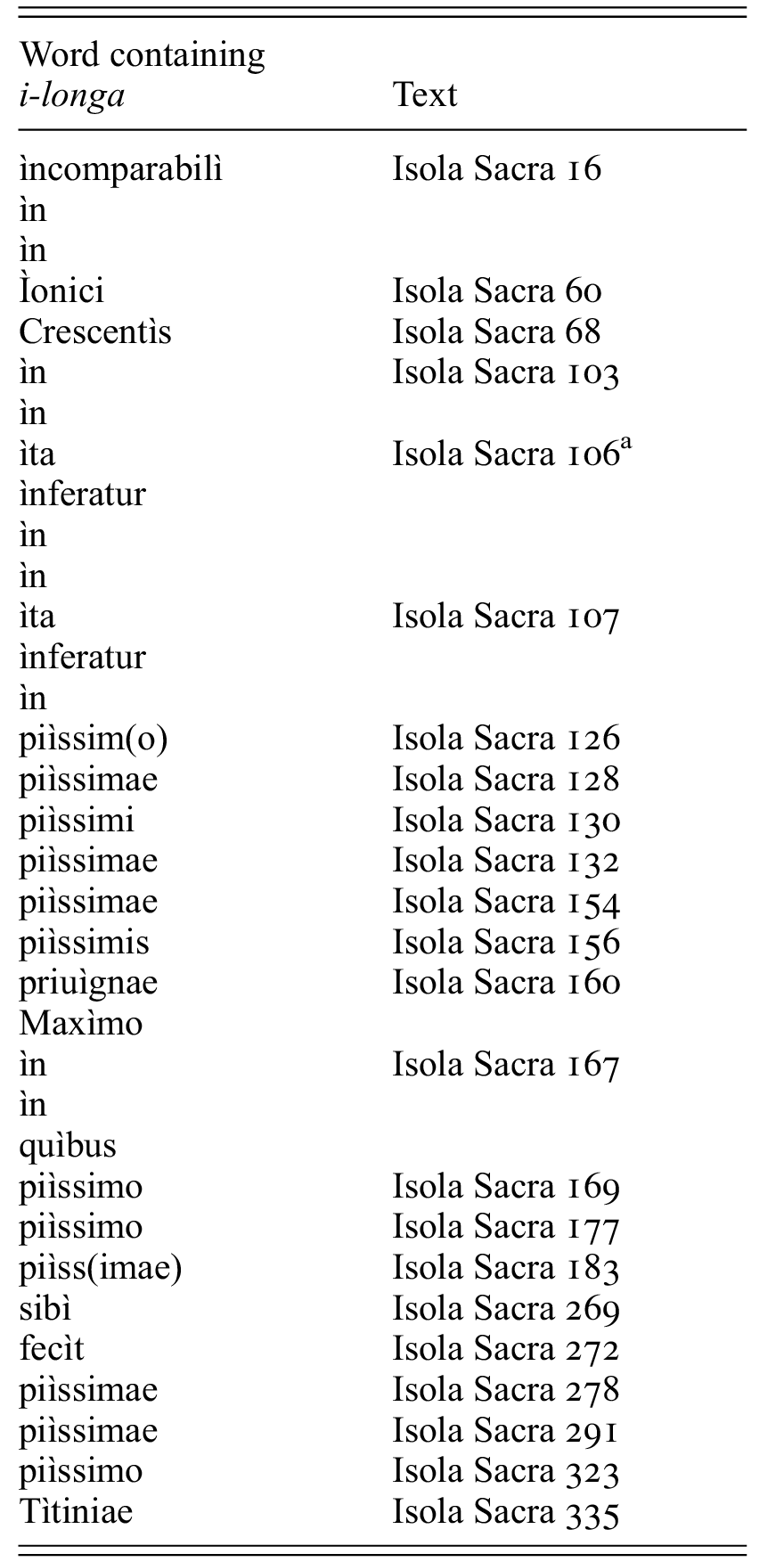

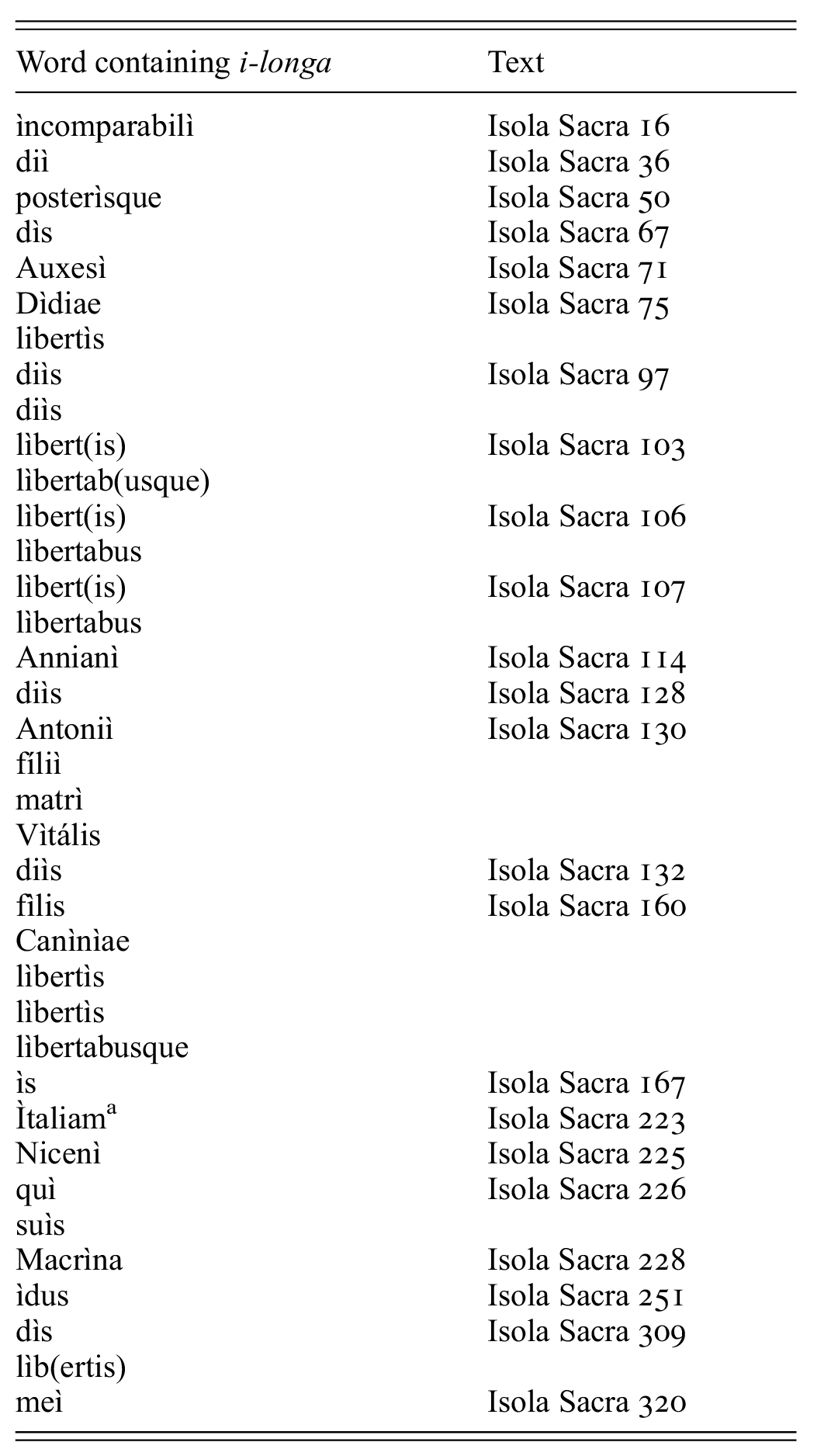

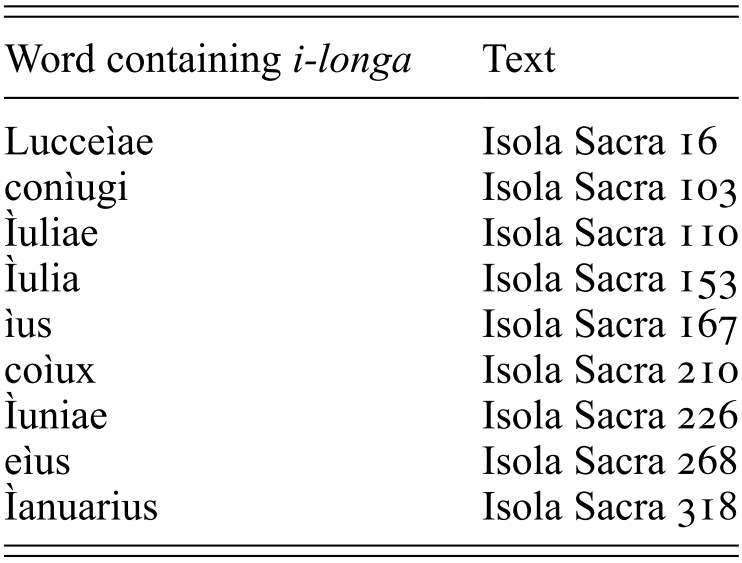

There are 84 instances of i-longa compared to 36 instances of apices in the Isola Sacra inscriptions, introducing the theme we will see in the tablets of the Sulpicii, and those from Herculaneum, of greater use of i-longa than of the apex. As in the other corpora, i-longa is found to represent long /iː/ (37; Table 33), short /i/ (34; Table 32), as well as /j/ (9; Table 34), plus 4 more uncertain whether short /i/ or /j/.Footnote 2 Unlike in the TH2 corpus, where <ì> is massively favoured as a way to write /iː/, a (small) plurality but not a majority of <ì> in the Isola Sacra inscriptions represent /iː/. This matches with the use of apices in this corpus, where marking of long vowels was not a priority.

Table 32 i-longa on short /i/ in the Isola Sacra inscriptions

| Word containing i-longa | Text |

|---|---|

| Isola Sacra 16 |

| Ìonici | Isola Sacra 60 |

| Crescentìs | Isola Sacra 68 |

| Isola Sacra 103 |

| Isola Sacra 106Footnote a |

| Isola Sacra 107 |

| piìssim(o) | Isola Sacra 126 |

| piìssimae | Isola Sacra 128 |

| piìssimi | Isola Sacra 130 |

| piìssimae | Isola Sacra 132 |

| piìssimae | Isola Sacra 154 |

| piìssimis | Isola Sacra 156 |

| Isola Sacra 160 |

| Isola Sacra 167 |

| piìssimo | Isola Sacra 169 |

| piìssimo | Isola Sacra 177 |

| piìss(imae) | Isola Sacra 183 |

| sibì | Isola Sacra 269 |

| fecìt | Isola Sacra 272 |

| piìssimae | Isola Sacra 278 |

| piìssimae | Isola Sacra 291 |

| piìssimo | Isola Sacra 323 |

| Tìtiniae | Isola Sacra 335 |

a The second in in the final line is not marked with an i-longa by the editors, but is clearly visible in the accompanying photo.

Table 33 i-longa on long /iː/ in the Isola Sacra inscriptions

| Word containing i-longa | Text |

|---|---|

| ìncomparabilì | Isola Sacra 16 |

| diì | Isola Sacra 36 |

| posterìsque | Isola Sacra 50 |

| dìs | Isola Sacra 67 |

| Auxesì | Isola Sacra 71 |

| Isola Sacra 75 |

| Isola Sacra 97 |

| Isola Sacra 103 |

| Isola Sacra 106 |

| Isola Sacra 107 |

| Annianì | Isola Sacra 114 |

| diìs | Isola Sacra 128 |

| Isola Sacra 130 |

| diìs | Isola Sacra 132 |

| Isola Sacra 160 |

| ìs | Isola Sacra 167 |

| ÌtaliamFootnote a | Isola Sacra 223 |

| Nicenì | Isola Sacra 225 |

| Isola Sacra 226 |

| Macrìna | Isola Sacra 228 |

| ìdus | Isola Sacra 251 |

| Isola Sacra 309 |

| meì | Isola Sacra 320 |

a In context, as the first syllable of a hexametric line, <i> the is presumably considered long.

Table 34 i-longa on /j/ in the Isola Sacra inscriptions

| Word containing i-longa | Text |

|---|---|

| Lucceìae | Isola Sacra 16 |

| conìugi | Isola Sacra 103 |

| Ìuliae | Isola Sacra 110 |

| Ìulia | Isola Sacra 153 |

| ìus | Isola Sacra 167 |

| coìux | Isola Sacra 210 |

| Ìuniae | Isola Sacra 226 |

| eìus | Isola Sacra 268 |

| Ìanuarius | Isola Sacra 318 |

The reason for this fairly equal distribution is that, even more than with the apices, use of i-longa is often driven by non-strictly linguistic factors, in particular a tendency for i-longa to be used to create visual clarity when preceded or followed by a letter formed with an upright stroke. The clearest example of this is the use of <ì> for the second vowel in a sequence /i.i/ found in the word piissimus, which makes up 12/34 of the instances of i-longa for a short /i/. There was evidently a convention that in such a sequence the second <i> was lengthened for visual clarity.Footnote 3 Many of the examples occur in inscriptions in which i-longa was not otherwise used, despite the presence of other instances of <i> (IS 126, 154, 156, 169,Footnote 4 177, 183, 278, 291, 323), which demonstrates that it is just this sequence which was targeted.

Unsurprisingly, where the second <i> in the sequence represented long /iː/, i-longa is also sometimes found. Again, in IS 36 (diì), 97 (diìs, twice), and 132 (diìs, piìssimae), it is only used in this context. The same is true of 128 (diìs, piìssimae, although long vowels are also given apices in mánibus, Iúliae, Apollóniae). In IS 130, three sequences of <iì> are found (Antoniì, fíliì, piìssimi), but the i-longa is also used to mark long /iː/ in matrì and Vìtális. In these last two inscriptions, an interaction between use of i-longa and the decorational/emphatic purpose of the apex seems possible (diìs agreeing with mánibus, piìssimae with Iúliae and Apollóniae; fíliì and piìssimi agreeing with Vìtális, Capitó, and Ianúárius). In Ìdus (251), the first letter of the word comes directly after the number IIII, so the i-longa here serves a useful function in marking off the number from the start of the word (although there is also an interpunct there is little space between the two).

Practically all the instances of i-longa for short /i/ can be explained by a similar habit, where I is next to N (ìn, ìn-), M (maxìmo) or T (Crescentìs, ìta, Tìtiniae, fecìt), as can many instances for long /iː/ and /j/: L (lìbertis, lìbertabus, fìlis), T (libertìs, Ìtaliam, Vìtális), N (Annianí, Nicenì, Macrìna, Antonì, conìugi). In these cases, the adjacent letters all involve one or two uprights which, when adjacent to the single upright of I, could cause some confusion in reading.Footnote 5 Of course, this may be coincidental, and there are examples of <ì> next to other letters. But support comes firstly from the very clear case of Canìnìae and Can\inìae, where the photo shows how much more difficult to segment the sequence NINI in the former and INI in the latter would be without the use of i-longa; and secondly from the fact that <ì> is not in fact the only letter that takes place in this process. Thus we find, for example, <t> lengthened in Sitti, merenti (IS 68), fecit, Rutiliae (IS 49), fecit (IS 99), optimáe (IS 130), libertis (IS 241, left side), Primitibus (IS 315), fecit, aditum, manumiserit (IS 320), Tattia (IS 332, third <t>) and <l> lengthened in libertis, libertabusque (IS 14), libertis (IS 71), libertab(usque) (IS 120).Footnote 6

Most examples of i-longa can be explained by reference to this practice, as well as the tendency we have already seen in the discussion of apices to use it as one of several methods to emphasise personal names.Footnote 7 In IS 60, for instance, in addition to Ìonici, the <y> found in Alypo and Chrysopolis is considerably higher above the line of the other letters (although there are no examples of <y> in non-names in this inscription to compare it to); the initial <a> of Alypo appears in the photo also to extend higher above the line than elsewhere, although this is not commented on by the editors. The <f> of f(ilio) in the name formula is also described by the editors as ‘grande’ (as well as the <x> of uixit). In IS 71, Auxesì has an elongated <x> as well as the i-longa, as does the <f> of Felici (although, as noted in fn. 6, <f> tends to be elongated before <e> anyway). In IS 75, beside the i-longa of Dìdiae, the second <e> of the cognomen Helpidis bears what the editors call ‘a stroke at the top, lengthened towards the left’ (un trattino superiore … allungato verso sinistra), which seems to be another way of marking out the name. In 130, every word in the sequence Antoniáe Tyche matrì optimáe has either an apex or an elongated letter (in the case of Tyche it is the <y>).Footnote 8

Unlike with the apices, whose use might be a feature of the spelling of the writers of the inscriptions or a practice of the stonemasons themselves, the heavy usage of i-longa as a means of avoiding consecutive upright strokes seems more likely to be due to the stonemasons rather than telling us anything about sub-elite education more widely.

All in all, there are only a handful of cases of i-longa which do not fit into this picture. For example, in 167 the third line features a run of i-longa in ìs quìbus ìus, for which I do not have an explanation, but observe that <ì> is used here on a long /iː/, a short /i/ and a /j/ respectively, so is probably not marking a linguistic feature (there are several other instances of unmarked <i>, as well as two of ìn). There may be one or two instances where the writers are intentionally marking long /iː/ (e.g. quì and suìs in IS 226), but on the whole I would attribute the remaining unexplained cases as due to the practical or aesthetic considerations of the stonemasons. The emphasis on practicality, decoration and text structure over phonology in the use of apices and i-longa in the Isola Sacra inscriptions is something to keep in mind as a parallel when considering usage in the other texts which we are about to look at: although of course in some ways the praxis of writing with ink or a stylus on wood or wax is very different from carving on stone, nonetheless there are – as we shall see – some similarities. They also give us an idea of the range of uses that these features can be put to, which are quite different from those implied by the writers on language and by elite inscriptions.