A Painting

One fun-filled afternoon early in April 2011, as I sparred once more with the Hawai‘i State Library microfilm readers, my eye picked up the word ‘Yamashiro’ in an unusual context. Limiting my search period to June–July 1885, I had been browsing the Daily Pacific Commercial Advertiser, owned by then-Hawaiian minister for foreign affairs, Walter M. Gibson. The pages were grainy on the screen, my control of the scrolling speed shaky. I registered a headline, ‘HAWAIIAN ART’, and then, at the end of the article, paused on the sentence: ‘Mr. Irwin, His Majesty’s Charge d’Affairs [sic] in Japan, takes the picture with him to Japan on the Yamashiro Maru.’ I rewound, zoomed in, waited for the machine to focus – and then commenced reading.

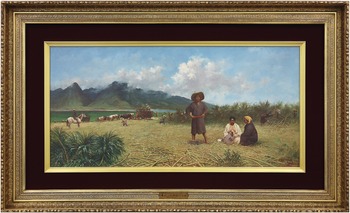

The article announced a ‘Handsome Present from His Majesty the King to the Emperor of Japan’: a ‘fine picture’, approximately 60 inches wide by 30 inches high (152cm by 76cm), by the artist J. D. Strong, depicting a scene ‘on Maui, where Mr. Strong took many elaborate sketches’:

In the foreground stands a strong, fine looking Japanese man, with his hands resting on his hips and his feet apart, gazing good-naturedly out of the pictures [sic]. By his side sit two women, also unmistakably Japanese, who are giving a little baby a drink of water out of a bowl. […] In the middle distance is Spreckelsville and a glimpse of the sea, with a final background of lofty mountains, topped by floating clouds.Footnote 1

In other words, nothing to concern myself with. More out of duty than genuine interest, I inserted a quarter into the microfilm machine, cropped and printed the article, and scrolled on.

Some months later, I did an internet search for Strong – Joseph Dwight Strong (1853–99) – and Spreckelsville, and, much to my surprise, found the painting on Wikipedia with the title, ‘Japanese Laborers on the Sugar Plantation in Spreckelsville, Maui’. I realized I had seen the image before, at least a detail of it: the man, two women and child appear on the front cover of a book published in 1985 to commemorate the centenary of Japanese government-sponsored immigrants first arriving in Hawai‘i. I had bought a Japanese-language copy of the book at the Bishop Museum during my 2011 fieldwork in Honolulu.Footnote 2 And now I was genuinely interested, for in the meantime, I had discovered that Kodama Keijirō had himself worked on the Spreckelsville plantation after his arrival in ‘Hawaii Nei’ in June 1885. If I wanted to write about Kodama, I needed to see the picture – ideally, in the flesh. But the Wikipedia copy, uploaded by the contributor Wmpearl in October 2007, merely noted that the painting was owned by a ‘private collection (Taito Co, Tokyo)’.Footnote 3 What were my hopes of identifying that company, let alone gaining access to the collection?

What happened next is a salutary tale in how not to conduct research. I moved jobs, I procrastinated, I wrote about the painting in passing – and I asked one of my new Zurich colleagues, Hans B. Thomsen, an expert in Japanese art, about ‘Taito Co’. He got to work with his customary generosity, and within a couple of weeks suggested that the company might possibly be Taitō – that is, the post-war incarnation of the Taiwan Sugar Company (Taiwan Seitō Kabushiki Kaisha 台湾製糖株式会社, itself often abbreviated to Taitō 台糖 in Japanese). In fact, to save him time, I could have simply looked at the back cover of the 1985 centenary publication, where the painting’s corporate owner is spelled out loud and clear – but I’d failed to do so (and Hans still doesn’t know).Footnote 4 Either way, all we now had to do was contact the present-day successor to Taiwan Sugar, the Mitsui Sugar Co. Which is how, on a spring morning almost exactly eight years after I first read about Strong’s ‘fine picture’ in Honolulu, I found myself in Tokyo, in the Mitsui Sugar president’s office, standing in front of what one art historian has called a ‘monumental genre painting […] virtually unparalleled in Hawaiian art of the period’ (see Figure 2.1).Footnote 5

Figure 2.1 Joseph Dwight Strong, ‘Japanese Laborers on the Sugar Plantation in Spreckelsville, Maui’, 1885.

In fact, this wasn’t my first unmediated encounter with the painting, but it was the first time I’d seen it in situ. Most striking to the eye was a feature which didn’t appear on the internet, nor on the cover of the 1985 book, namely the work’s massive gold and plush frame. Almost a work of art in itself, it was grand, fussy in its intricately carved geometries, and above all extremely heavy. (At fifty-nine kilograms, it probably weighed about the same as the Japanese man depicted in the painting’s foreground – assuming, like Chapter 3’s Fuyuki Sakazō, that he was just under five feet tall.) Made to order by the Honolulu-based King Bros, it was a frame fit for a monarchical gift.Footnote 6 And yet the ‘handsome present’ self-evidently had not ended up in the Japanese imperial household. Hanging in private collections, it had seemingly not accomplished its object, according to the original Advertiser article, ‘of giving the Mikado a correct and pleasant idea of the new home and employment of his countrymen’.

Where Strong’s painting had instead been hung, and how it ended up here in the office of the Mitsui Sugar president, were partly explained by a small wooden inscription screwed into the King Bros. frame:

If Mrs Irwin, née Takechi Iki,Footnote 7 bequeathed Strong’s work to Taiwan Sugar sometime in the wake of her husband Robert’s death in 1925, then this would suggest that after arriving with the painting in Japan on the Yamashiro-maru in August 1885, Irwin kept it in his private residence for forty years – for reasons I shall later speculate.

At any rate, by the early 1930s Strong’s painting was hanging in the offices of Taiwan Sugar, a company which Irwin had co-founded with businessmen connected to the Mitsui conglomerate in 1900. The company’s president after 1927 was fellow co-founder Takechi Tadamichi (1870–1962) – who was also a relation by marriage to Irwin himself.Footnote 8 And there, fifty years after its composition, the work acquired a set of different associations from its (alleged) original object. On the one hand, it reminded Takechi ‘of the period in his youth that he spent in Hawai‘i’ as a student at Oahu College in the mid 1880s – a period which had begun with his passage there on the Yamashiro-maru in June 1885.Footnote 9 On the other hand, its very location spoke to the history of Taiwan Sugar, one of colonial Japan’s most important corporations. Indeed, just as the painting had been used to frame a centenary success story of Japanese immigration to Hawai‘i in 1985, so, in 1990, it was reprinted at the beginning of Taitō’s ninety-year company history. Juxtaposed to a preface penned by then-president Takechi Fumio (Tadamichi’s son), in which Taiwan Sugar was celebrated as having transformed a ‘disease-ridden primitive land’ (mikai shōrei no chi 未開瘴癘の地) into a site of modern sugar production, Strong’s work took on a set of colonial and neo-colonial associations across the twentieth century.Footnote 10 In short, the painting I was gazing at in Tokyo had acquired multiple new meanings in its passage from Hawai‘i to Japan.

This chapter explores such histories of meaning changing in passage. Indeed, what was true of Strong’s painting was also true of the subjects depicted therein: as I shall first argue, the Japanese men, women and children who crossed to Hawai‘i on the Yamashiro-maru – or any other migrant-carrying ship during this period – experienced the world differently as a consequence of their transit between Yokohama and Honolulu. To study these quotidian transformations is important because the significance of ships as historical arenas in their own right has often been overlooked, as historians interested in global migrations start their analyses in place A and continue them in place B, irrespective of what happened in-between. Some scholars have even gone so far as to argue that transoceanic migrant voyages ‘will be short, at least in memory, because nothing of interest is being recorded. What for mariners is a sea-lane, for a rural or urban migrant is an empty expanse.’Footnote 11

Such claims of the passage as empty of meaning derive partly from the surviving source genres. Alongside Robert W. Irwin and Takechi Tadamichi, Fujita Toshirō (1862–1937) was another first-class passenger on the Yamashiro-maru in June 1885. As his later autobiography makes clear, his crossing to Hawai‘i opened a new chapter in his life, marked by his transformation from employee at the KUK (owner of the ship) to his first assignment as budding diplomat – a career which would eventually take him to San Francisco, Mexico, Singapore and beyond.Footnote 12 And yet he described this transpacific journey in only one half-sentence: ‘I became a clerk in the Foreign Ministry on 29 May, Meiji 18 [1885]; five days later I boarded the Yamashiro-maru and began my assignment in Honolulu’. Fourteen days at sea is compressed into a change of verb, from ‘boarding’ (tōjō 搭乗) to ‘beginning of assignment’ (funin 赴任).Footnote 13 We can be sure that had pirates attacked, or the Yamashiro-maru’s crew mutinied, or perhaps even had the ship’s engines conked out mid-journey, Fujita would have written more. For an elite actor writing from a retrospective position of having travelled the world, however, the passage seemed narratively unimportant. But if historians equally view transoceanic time as ‘nothing of interest’, we risk silencing the key actors in histories of migration, namely the migrants themselves. By seeking to reconstruct processes of transit from other genres of sources, this chapter offers new understandings of the migratory lives of labourers such as those in Strong’s plantation painting.

My second interest lies in how men and women similar to Strong’s subjects were ascribed new meanings during their period(s) of transit by a range of powerful actors. For example, in my lukewarm excitement at having found a brief mention of the Yamashiro-maru in the microfilmed pages of the Advertiser, I had overlooked a key example of such ascriptions. Only some years later, retracing my steps with the aid of the text-searchable Chronicling America database, did I digest the whole 8 July issue in peace and quiet. I first noted the fact that directly under some self-puffery (‘The Weekly P. C. Advertiser is the best and most complete paper published in the Kingdom’, etc.), the page in question had printed the wrong date (7 July). And then, below this and to the left of the ‘Hawaiian Art’ article, I noticed the headline, ‘Japanese Friendship’.Footnote 14 This recorded the granting of a Japanese imperial decoration to Walter M. Gibson, observing:

[T]he honor conferred upon the Hawaiian Foreign Minister possesses more than ordinary meaning, and augurs well for the success of that industrial partnership, as it were, between the two countries, which is expressed so potentially by Japanese immigration. We have room and verge enough for tens of thousands of Japanese families on these Islands, and we hope to see them established here, in thrift and comfortable independence, under our equal and humane laws.Footnote 15

Here was a pregnant set of expectations: that the newly initiated government-sponsored migration programme would eventually expand to an ‘industrial’ scale;Footnote 16 that this would be a positive outcome for what the article earlier called ‘the well-being and progress of this Kingdom’; and that there was space for tens of thousands of migrants. No less than the King Bros’ golden carvings, this was also a frame for Strong’s painting: according to this interpretation, the man, women and child stood for those anticipated thousands of Japanese families and their potential contributions to the Hawaiian nation.

But was this how the migrants themselves understood their arrival as they began new lives in Hawai‘i? And, if not, how can historians counter such narratives of the decorated and the [s]trong? The answers to these questions lie partly in how the space of the in-between – that is, the passage between Fujita’s two verbs, or between the 17 and 18 June dates on Kodama’s gravestone – can be archivally reconstructed. My dream archive of the in-between would be the Yamashiro-maru itself.Footnote 17 But in the absence of the ship, the challenge is one of framing: of bringing together archives at both ends of the journey in order to make educated guesses about the meanings of the passage for the labourers who slept one deck below Irwin, Takechi or Fujita.Footnote 18 And the challenge is also of unframing: of using the archives, and their gaps, to identify the complex agendas which coalesced in visual and textual representations of ‘unmistakably Japanese’ subjects. Only in these ways, I will argue, is it possible to offer some kind of narrative corrective to what the Advertiser, describing Strong’s painting, suggested was a ‘fine representation of a sunny, thriving, hard-working plantation scene’.

Ship as Plantation Boot Camp

The Advertiser newspaper offered the male protagonist of Joseph Strong’s painting a basic humanism: he was ‘fine looking’ and he gazed ‘good naturedly’ outwards. In an ideal world, I would like to go one step further and determine his name. In an ideal world, indeed, I would like to reveal him as Kodama Keijirō, just arrived from Japan on the Yamashiro-maru and now adjusting to his new life in Spreckelsville.

The place to start such a quest – ultimately futile though it will be – is the Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in central Tokyo. This is because Kodama and the other Japanese who crossed to Honolulu in 1885 were part of a new, government-sponsored emigration programme (kan’yaku imin 官約移民) between Japan and Hawai‘i which was trialled that year after much lobbying of the Meiji government by Hawaiian Consul Robert W. Irwin. As usually explained in the secondary literature, the programme was pitched as beneficial to both sides. On the one hand, the sugar-planting lobby in Hawai‘i, which had become increasingly influential in the two decades since the end of the US Civil War (1861–5), would be guaranteed a supply of new labour for the plantations; on the other, Japanese farmers, impoverished by the land tax reform of the early 1870s and especially by the so-called Matsukata deflation (1881–5), would have a new income stream – and in a valued foreign currency.Footnote 19 The Mitsui Bussan trading company, whose founder, Masuda Takashi (1848–1938), was close friends with both Irwin and Japan’s foreign minister Inoue Kaoru, helped organize recruitment.

The first shipment of 945 labourers, arriving in Honolulu on 8 February 1885, was testament to this confluence of business, politics, and diplomacy in mid-Meiji Japan. More than a third of the labourers came from Inoue’s home prefecture of Yamaguchi, in the west of Japan; and they travelled on the specially chartered City of Tokio, a steamship owned by the Pacific Mail Steamship Company – for whom Irwin had worked when he initially came to Japan in 1866. After the City of Tokio sank in June 1885, Irwin chartered the Pacific Mail’s City of Peking for the third dispatch of labourers, in February 1886. In the meantime, the Yamashiro-maru, chartered for the second group, was owned by the KUK, one of whose principal shareholders was the Mitsui Bussan company’s Masuda Takashi.Footnote 20 (As we have seen, Mitsui interests, along with those of Irwin, also lay behind the establishment of the Taiwan Sugar Company in 1900.)Footnote 21

In the Foreign Ministry archives, four thick volumes name the post-1885 government-sponsored departees from Japan, with volume one listing every migrant on the City of Tokio, the Yamashiro-maru, and the City of Peking.Footnote 22 The lists are vertically compiled and divided into sections according to the male labourer’s home prefecture. At the top of each page appears the administrative subdivision one level below prefecture, namely county (gun 郡); and then come the migrant’s town or village, his detailed address, his status and profession, and, at the very bottom of the page, his – or his wife and child’s – name and age. All of the Yamashiro-maru migrants in 1885 were ‘commoner’ apart from three ‘samurai’, and all of the commoners were recorded as ‘farmers’. If the Strong painting was one medium by which the labourers became (or were intended to become) visible to Japanese government elites, then these Foreign Ministry volumes rendered them legible – similar to the exhaustive passenger lists of sixteenth-century New World migrants produced by Seville’s Casa de la Contratación.Footnote 23 Moreover, in this structuring of the archival page, both the compiler and the future reader were conditioned to frame each of the volume’s nearly 3,000 individuals by their provenance; and this, in turn, gives us some sense of what motives lay behind a young man wanting to move to Hawai‘i for work.Footnote 24

The concentration of departees from particular villages reveals the vicissitudes of Japan’s changing engagement with the outside world across the nineteenth century. For example, Hiroshima prefecture accounted for nearly the greatest number of migrants on board the Yamashiro-maru in June 1885 (390, or nearly 40 per cent). Within Hiroshima, Saeki county accounted for the greatest number of migrants (239); and, within Saeki, the village of Jigozen, which supplied thirty-seven migrants aged between twenty and thirty-eight, constituted the largest sending community. Like many of the migrant-sending villages from neighbouring Yamaguchi prefecture, Jigozen is located on the coast of the Seto Inland Sea. In the eighteenth century and up to the mid nineteenth, shipping lanes through the Inland Sea were crucial elements in the transport infrastructure by which western and northern domains shipped both their tributary taxes and their produce eastwards to the Tokugawa ‘kitchen’ of Osaka. There, they traded in commodities which they shipped back to distant ports via Shimonoseki, at the Inland Sea’s western extreme. As domestic trade increased through the eighteenth century, so too did the number of long-distance ships sailing east and west through small ports such as Jigozen; indeed, the village was one of many coastal communities between Osaka and Shimonoseki whose economies began to grow in this period at the expense of hitherto more established market and castle towns.Footnote 25 This, we must assume, lay behind the near-doubling of the population between the 1820s and 1881, when the village was recorded as having 2,300 residents.Footnote 26

In turn, such a demographic transformation throws light on the nominal ‘farmer’ status of the later Yamashiro-maru migrants. In fact, by the 1860s, only 40 per cent of Jigozen’s households were landowners – meaning that 60 per cent of the village’s population somehow made a living without owning land. Most likely, they survived on by-employments connected with the Inland Sea’s increased volume of trade, on coastal fishing, and also on work in the household industries that were renowned in this part of Japan, particularly cotton production. But these survival strategies made non-landed households particularly vulnerable to new infrastructures of interregional trade which were established in the wake of the 1868 Meiji revolution.Footnote 27 In addition, falling agricultural yield in Jigozen in the 1880s, and the opening of a new mill by the Hiroshima Cotton Spinning Company in Saeki county in 1883, created a perfect storm of problems for ‘farmers’ – many of whom had for a generation or two not worked exclusively in agriculture.Footnote 28

No wonder that a large group of working-age men – all men – sought to escape Jigozen in 1885: these were desperate times. A one-line entry on an emigrant list in Tokyo will never do more than hint at the complex motivations which spurred Jigozen villagers to up roots and cross the Pacific; but for a middle-aged man such as the thirty-seven-year-old Wakamiya Yaichi, there were perhaps already half a lifetime of employment disappointments tied up in such a decision. Perhaps personal disappointments, too: if he was married and already had children, he would not see his family again for the minimum three-year period he would be contracted in Hawai‘i. On the other hand, the draw of the new government-sponsored programme was substantial: a guaranteed, unfluctuating wage of nine US dollars a month on a sugar plantation (equivalent to 10.6 yen in 1885), plus room and board, was almost three times what Wakamiya could earn as a day-labourer in Jigozen.Footnote 29 Fuelling these expectations of economic independence and even prosperity, he would have read – or, more likely, have been read – a message from his prefectural governor on 25 May, the day when the migrants left Hiroshima for transit to Yokohama. Work hard, it said, using an idiom of triumphant homecoming, ‘that you may gain the distinction of one day returning to your home town dressed in brocade’.Footnote 30

There were nearly a thousand similar stories to Wakamiya’s on the Yamashiro-maru as it steamed out of Yokohama on 4 June. Such is the imbalance of historical sources in favour of the programme’s backers and organizers that a single entry in the Mitsui Bussan company diary reveals more about the departure than anything I will find in records relating to the migrants: to wit, the fourth was a rainy day, but Mitsui Bussan founder Masuda Takashi nevertheless went to wave the ship off from the pier.Footnote 31 I know hardly anything about Wakamiya Yaichi on board the Yamashiro-maru at that moment, and even less about Kodama Keijirō – who, unlike Wakamiya, was the only departee from his small village of Orisaki, in the county of Tamana, in the west of Kumamoto prefecture. In Orisaki, there was no group exodus by which a historian might hypothesize a motivation for departure, no chain reaction of transpacific migration such as that which would lead to early twentieth-century Jigozen becoming known as ‘America village’ for its high rate of overseas workers.Footnote 32 If I want to understand Kodama’s background, I will need a different archival strategy.

That said, the paper trail generated by the Yamashiro-maru’s botched arrival in Honolulu offers an initial clue as to the transformation that the ship’s migrants underwent while onboard. As soon as the 988 surviving men, women and children were released from quarantine, and just before they were dispersed to plantations throughout the kingdom, the men’s names were entered in the ‘Laborer Contract Book’, today kept in the Hawai‘i State Archives. Each name has been transliterated into the Roman alphabet, but instead of providing vertical information on provenance, the book lists them horizontally, next to a number: Kodama is #1146, Wakamiya, #1405. This was the bango, an individual number engraved on a metal disk and hung around the migrant’s neck like the dog tags later worn by soldiers. (Women, absent in the ‘Laborer Contract Book’, went by their husbands’ bango.)Footnote 33 Such numerical labelling made it easier for employers and government officials to discuss individual cases without dealing with what they clearly regarded as the encumbrance of Japanese names. For example, correspondence from Kaua‘i’s Kekaha plantation regarding Takiguchi Jinta, who arrived on the Yamashiro-maru in 1885 but died eighteen months later at the age of thirty-six, simply referred to ‘the death of Japanese #863’, as if discussing an account-book entry.Footnote 34

By juxtaposing the Tokyo and the Honolulu archives, historians can therefore frame a small but significant transformation in how the labourers were officially identified. On their departure from Yokohama, Wakamiya Yaichi, Kodama Keijirō or Takiguchi Jinta were individuals with names, but on their arrival in Honolulu they were objects with numbers. If later testimony is anything to go by, this shift from name to number was a source of considerable grievance. ‘The [overseers] never call a man by his name,’ one Japanese migrant recalled. ‘Always by the bango, 7209 or 6508 in that manner. And that was the thing I objected to. I wanted my name, not the number.’Footnote 35 In this sense, my desire to give the male protagonist in Strong’s painting an individual name is anachronistic. To the overseer on horseback, and possibly even to Strong himself, this ‘fine looking’ man and his presumed wife were no more than a shared number in a ledger book.

And if we dig further into the moment of the Yamashiro-maru’s arrival, it becomes clear that a second, more existential transformation occurred in the migrants’ lives between embarkation in Japan and disembarkation in Hawai‘i. For Wakamiya, Kodama and Takiguchi did not simply step off the ship and dally into port. Rather, following the outbreak of smallpox among a dozen labourers during the Yamashiro-maru’s passage, the migrants were bundled off to the isolation of Honolulu’s Sand Island quarantine station. There, in what later became known among the Japanese as the sennin-goya, or ‘thousand-person huts’,Footnote 36 they and their compatriots spent more than a month, surrounded by high paling and a watchtower, and guarded by as many as ten men during the daytime.Footnote 37 (The Japanese reportedly ‘kept their quarters and the grounds beautifully clean’, with ‘their own police [guarding] against any nuisance being committed anywhere near the quarters’.)Footnote 38 These cramped conditions offered migrants a foretaste of the minimal accommodation on some of the sugar plantations, where the wooden bunks of similarly named ‘thousand-person huts’ could be stacked three or four high.Footnote 39 For Wakamiya Yaichi as for the others, then, this was an existential transformation in the sense that his physical freedom of movement was considerably curtailed in Hawai‘i compared to his old life in an Inland Sea port. In the quarantine station, it was curtailed by high paling and guards; on the plantation, by a strict labour regime which was laid out in the contract each migrant had signed and then enforced through overseers and managers, kingdom officials and Japanese consular staff, and, in the worst-case scenarios, through the Hawaiian courts.

That such adjustments to time regimes and curtailments of freedom could lead to outbreaks of conflict between the labourers and their overseers was unsurprising.Footnote 40 A different folder in the Japanese Foreign Ministry Archives contains dozens of pages of written testimony detailing the problems that some ex-City of Tokio migrants faced within a few weeks of having arrived – problems corroborated by records in Hawai‘i. From Pā‘ia in central Maui, for example, came complaints of ‘rough handling, insufficient medical attendance, compelling men to work who are sick, and bringing men to court for refusal to work’, as the Hawaiian Board of Immigration’s special agent reported in April. Moreover, ‘On Paia plantation, about the middle of March, a native Hawaiian, a bullock driver, had a dispute or rather fight, with a Japanese, the Japanese received a scalp wound in the forehead.’ After the subsequent court case, ‘all the Japanese, except those on the sick list, […] refused to work and arming themselves with knives and sticks made threatening demonstrations along the highway’.Footnote 41

The Board of Immigration’s president, in a soothing letter to the Japanese Consul in Honolulu at the end of May, acknowledged these accounts but explained that on Pā‘ia and the neighbouring plantation of Haiku, ‘immigrants of the farming class, of simple habits, came into a strange country, [and] the people who received them were unaccustomed to their habits, and ideas, and did not make sufficient allowance’.Footnote 42 Although he promised that Pā‘ia and Haiku would henceforth be given a ‘trial’ status in the government-sponsored programme, bureaucrats in Tokyo were sufficiently alarmed to arrange for a special commissioner to accompany the programme’s second shipment of labourers in June. Inoue Katsunosuke, the adopted son of Foreign Minister Inoue Kaoru, was to report back to the ministry on plantation working conditions, with the threat – not quite spelled out – that if he were unhappy with what he observed, the government-sponsored programme would be suspended or abandoned. Even in late June, however, as Inoue saw out his own quarantine in the considerably more salubrious conditions of the offshore Yamashiro-maru, ex-City of Tokio labourers on Pā‘ia were still complaining of horseback-mounted lunas (overseers) beating them with cane stalks, spitting on them, kicking them in the head, lassoing their necks with the horse’s whip, and depriving them of drinking water during working hours.Footnote 43

To a newly arrived Japanese labourer, therefore, the basic composition of Strong’s painting would have been all wrong. In light of the Pā‘ia complaints, the bullock cart and the mounted luna would have brought very different associations. The overseer would always have been at the foreground of their daily consciousness. And it seems very unlikely that the male protagonist, or indeed any other labourer, would have found (or been granted) time during the working day, especially during the cane-cutting season, to have a cup of tea with his wife and child, let alone gaze good naturedly over his place of work.

Admittedly, such maltreatment of men and women with ‘simple habits’ lay at the far end of a spectrum of migrant experiences in 1885 Hawai‘i. No labourer could have expected kicking and spitting and beating, especially in light of pre-departure visions of brocade. On the other hand, the labourers cannot have been entirely surprised by the change of habits they were forced to experience upon arrival. This is because, in material ways, the shipboard passage had already habituated them to a new way of experiencing the world. First-class passengers might well enjoy the ‘fine smoking room’ to the aft of the Yamashiro-maru’s central funnel, or a sheltered promenade along the ship’s stern railings; they could commune, immediately below the smoking room, in a ‘handsome’ dining saloon which was ‘well lighted with electric lights of various descriptions’, or in the music room; and they could relax in ‘large, lofty, and well ventilated’ cabins, each containing two berths and a bell to summon the steward. By contrast, the 940 male labourers, thirty-five women and fourteen children on the government-sponsored emigration programme spent the majority of their days packed into two rooms, one deck below first-class.Footnote 44 The floors on which the migrants slept were supplemented by large wooden bunks built inwards from the Yamashiro-maru’s port and starboard sides (compared by some migrants to silkworm shelves).Footnote 45 Here, each migrant had an individual sleeping area of a little over 0.9 square metres, or approximately 163 by 55 centimetres, most probably with about 80 centimetres to sit up and/or change clothes. Coffin-like accommodation this was not, in comparison to so-called ‘coolie’ labourers transported across the Pacific and Indian Oceans in the mid nineteenth century.Footnote 46 Moreover, the Yamashiro-maru’s newness marked it out from vessels typically used in the contemporary Melanesian forced-labour trade, many of which became human transporters only after they were no longer fit for inanimate cargo.Footnote 47 But, sleeping head-to-foot and probably three people deep on either the deck’s floor or the elevated wooden bunks, using futons or ship canvasses as mattresses and any blankets they themselves had brought,Footnote 48 it seems unlikely that Wakamiya and his fellow villagers would have enthused – as had Osaka residents viewing the Yamashiro-maru for the first time in 1884 – about the ship’s ‘lofty ‘tween-decks’.Footnote 49

Thus, just as the ‘thousand-person huts’ at the Sand Island quarantine station prepared the migrants for later accommodation on the sugar plantations, so the ship played a crucial role in socializing Wakamiya and his compatriots for the physical confinements of their new lives. Not for nothing did one Hawaiian planter offer a casual analogy about plantation living conditions in the mid 1880s: ‘Dwellings for plantation laborers are furnished free of rental by the plantations. The rooms are generally about twelve square feet, and for unmarried men contain bunks, as in ships.’Footnote 50 Moreover, when Irwin decreed, five days out of Yokohama, that the migrants must take three hours of daily exercise on the upper deck of the Yamashiro-maru (safely screened off from the fourteen first-class passengers), Wakamiya experienced for the first time the intervention of a white man in his daily routines and bodily regimes.Footnote 51 This would be a precedent both for the mass disinfecting showers which the migrants would be forced to take in the quarantine station, and for the racial hierarchies of their lives on the plantations. Even the auditory sensations of the ship – the bridge bell, sounding every half-hour and then eight times on the fourth hour to mark a change of watch, or the constant rumble and grind of the engine – prepared the migrants for the new time regimes they would experience on the plantations, and for the non-stop clatter of the sugar mill. Archivally framed in this way, the ship can be seen for its partial function: not just a mode of transportation, but a boot camp for the plantation.

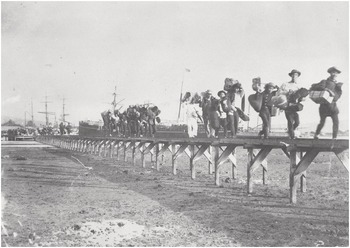

That said, ignorance was also an aspect of the in-between. One of my favourite photographs from Hawai‘i has nothing to do with the Yamashiro-maru: rather, it depicts government-sponsored migrants from the Miike-maru, circa 1893, crossing a long wooden walkway across the beach from ship to land (see Figure 2.2). The men are laden down with luggage – with rolled-up bedding, bamboo-woven trunks, shoulder-bags stuffed with clothes, pots and pans and other packages, all slung over their backs and balanced on the backs of their necks.Footnote 52 They glance towards the strange sight of photographic paraphernalia as they approach shore, and the foremost two men offer a smile. Even in the stillness of the celluloid, there seems to be a spring in the migrants’ step. Arriving in Hawai‘i, the men cannot know how their new lives will unfold. The photograph thus captures them in an extended moment of landfall, a moment which arguably began as soon as they left their home towns and villages in rural Japan.Footnote 53

Figure 2.2 Japanese immigrants landing. Honolulu, c. 1893.

The Nation Cheek by Jowl

The photograph of labourers arriving in mid-1890s Hawai‘i also takes us into a different aspect of the migrants’ daily lives, namely their visual framing as ‘Japanese’. To comprehend one making of that ascribed identity, a short detour is necessary: to explain why, in 1885, a German doctor was present in the kingdom.

Of all the new phenomena visited upon nineteenth-century Hawaiian society, arguably the single most important was disease – acute infectious disease on an unprecedented scale. When one of the ali‘i (chiefs) of Kaua‘i island, Kā‘eokūlani, had a group of men paddle out to engage with the newly arrived foreign ships in what those foreigners called January 1778, there were perhaps 500,000 or more Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) living on the islands as a whole. But among the gifts bestowed by Captain Cook’s men in that first visit were syphilis, gonorrhoea and almost certainly tuberculosis as well. Thus began a century of Native decimation by illnesses which came later to include also mumps, smallpox, measles, influenza and dysentery. By the late 1870s, the islands had lost at least 70 per cent of their Indigenous population, if not 90 per cent.Footnote 54

In Strong’s 1885 painting, particular details spoke to wider ecological and epidemiological transformations in the history of Hawai‘i. For example, the oxen and the overseer’s horse were both animals imported at the turn of the nineteenth century, with massive unanticipated consequences for questions of enclosure and therefore land ownership; and the newly cut cane reminded the viewer of sugar’s post-1830s emergence as the archipelago’s key commodity.Footnote 55 But the most important detail, whether intentional or not, was the almost complete absence of Kānaka Maoli in Strong’s work. In a painting set in Hawai‘i, there were no Native Hawaiians – at least at first sight. Absence-by-disease was a history weighing upon the scene like the clouds hanging over the painting’s background mountains; and absence explained why imported labour from Asia, the Pacific Islands and even Europe was necessary in the first place.

By the mid 1880s, leprosy had joined the list of diseases afflicting Native Hawaiians – although, as historians have subsequently shown, its discursive impact was in some ways more significant on Hawaiian society than its death count. In a throwback to the practices of twelfth-century Europe, foreign doctors in Hawai‘i peddled the association of leprosy with indolence and filth, and thus insisted on segregating Native patients from the general population. One Strasbourg- and Breslau-trained dermatologist, Eduard Arning (1855–1936), who was appointed government resident physician by the Hawaiian Board of Health in 1883, claimed that sufferers were ‘dangerous’ and ‘a hot bed of contagion’.Footnote 56 Reinforcing the association of leprosy with immorality, Arning arranged in 1884 for the death sentence of a convicted Native Hawaiian murderer, forty-eight-year-old Keanu, to be commuted so that the doctor might suture leprous tissue into the prisoner’s arm. The aim, as Arning explained in a letter to King Kalākaua, was to conduct experiments ‘in relation to the possibility of inoculating leprosy on healthy subjects’. Though he declined to ‘dwell here on the propriety of these experiments’,Footnote 57 they attracted much comment in the British Medical Journal in a period when, in the words of one historian, ‘Hawai‘i was coming to be seen as the imperial world’s leprosy laboratory’.Footnote 58 (Keanu died on the so-called leper colony in Molokai in 1892.)

When not treating patients, Arning took photographs as a hobby. His lens roved widely, exploiting the access to ordinary Hawaiian homes that he enjoyed as a doctor. As to be expected from a European male working in the late nineteenth-century Pacific region, Arning’s depictions of human subjects have at times a voyeur quality: here he lines up four lightly clad New Hebridean labourers next to their (three-piece-besuited) Caucasian helmsman; there he positions a small group of half-naked Melanesian workers, the women’s waists covered with dried-grass skirts.Footnote 59 Doubtless the doctor would have defended his compositions as ‘authentic’ and also of medical–ethnographic interest – a corporeal and cultural study, in which the accompanying props (spears, coconuts, clothing) were allegedly revealing of differences between Pacific Islander communities. As such, it was unsurprising that Arning was among the visitors to the Honolulu immigration depot on 11 February 1885, when the city’s great and good gathered to welcome, and to gawk at, a new group of islanders, namely the very first group of Japanese labourers recently arrived on the City of Tokio. According to the Advertiser newspaper, the ‘representatives of the various [Japanese] provinces’ offered King Kalākaua and members of his government ‘an exhibition of wrestling that was very interesting and amusing’. As if anticipating Arning’s own physiological interests, the Advertiser’s correspondent continued:

Those who were to take part in the wrestling wore nothing but a band of cloth passed between their legs and then wound around the waist. Their naked bodies showed every degree of muscular development, some being without any superfluous flesh, but wilh [sic] plenty of sinew, while others were clothed with an abundance of solid brawn, and a few were inclined to fatness.Footnote 60

Arning was on hand to record these wrestlers for posterity, and nine of the images he took that day survive. They capture a variety of poses: groups of families gathered around rice pots; a woman playing the shamisen next to her husband and child; migrants seated or lying on thick blankets; a reader, a smoker and their companions observed by two Caucasian men; a bathing scene in which the women expose their breasts and a toddler stands naked; and, of course, the much-observed bout of sumo. They also include a group shot, of eleven adults and a backward-facing child, which seems designed to capture all the variety in yukata (summer kimono) design that one might expect from a large, diverse group: the cottons worn are variously plain dyed, striped, checked, dark-coloured and light (see Figure 2.3). One man, on the second-right of the back row, wears his yukata somewhat unnaturally over a collarless, buttoned shirt; another, squatting on the front row, turns his back to the camera as if deliberately to display the Chinese character on his back. That this and all the scenes were staged, for technical as well as compositional reasons, does not diminish their historical value. In the bodies on display, as well as in the material culture of pots, pans, bedding, clothing and luggage, Arning’s photographs offer scholars a more vibrant snapshot of Japanese rural life in the mid 1880s than any descriptions of the quotidian I have been able to find in the prefectures whence the migrants originally came.

Arning’s photographs were also a visual manifestation of a written trope pervasive in all contemporary descriptions of the City of Tokio and later Yamashiro-maru arrivals: the migrants as Japanese. English-language newspaper readers in Honolulu were not only informed of ‘Japanese sports’ being performed at the immigration depot; they could also educate themselves – by reading the reprint of a long public lecture delivered by the recently departed US consul-general to Japan – about the working conditions of the ‘Laborer in Japan’. One of the consul’s express hopes was that the Japanese would ‘prove themselves industrious, capable, temperate, amiable, obedient to law, and ready to identify themselves with your progress and your prosperity’.Footnote 61 Yet Japaneseness in 1885 was a claim as much as an empirical reality. To the migrants themselves, the fact that they came from ‘various provinces’ would have loomed as large in their consciousness as any labelling about their life in Japan. Indeed, until they left their home towns to come to Hawai‘i, many of the migrants may never have met men and women from different provinces. For this reason, our ability to imagine the shipboard passage between Yokohama and Honolulu is important in terms of discourses of nationhood. For not only was the ship a preparation for the plantation; it was also a space of nascent nation-making.Footnote 62

The transformation of scale in a migrant’s sense of imaginative belonging, from village to nation, began with the bureaucracy of the government-sponsored programme itself. When Wakamiya Yaichi applied for his passage to Hawai‘i in late April 1885, for example, he addressed his papers – including a pledge of good behaviour, a request for passage assistance, and a statement from his guarantor (usually an older relative) – to the head of the Jigozen village office.Footnote 63 In a community of 2,000 people, this bureaucrat, who was also a neighbour, would have been a familiar face in mediating Wakamiya’s interactions with the Meiji state.Footnote 64 In such a role, village elites would have dealt on Wakamiya’s behalf with officials in the Saeki county office; they, in turn, would have dealt with officials in the Hiroshima prefectural office; and prefectural officials would finally have dealt with bureaucrats in Tokyo. By contrast, once the City of Tokio and Yamashiro-maru migrants arrived in Honolulu and were dispersed to their individual plantations, this familiar local face of the bureaucratic state no longer existed. Instead, the migrants communicated with a direct representative of Tokyo in the form of the Japanese consul and his deputies in Hawai‘i, or with Japanese inspectors employed by the consulate. Compared to the familiar mediation on offer in Jigozen, the Meiji state became more impersonal in Hawai‘i – and yet, in terms of bureaucratic layers, conversely less distant. From Wakamiya’s new plantation, and indeed from his moment of embarkation on the ship, Tokyo was figuratively closer than it had ever been in Jigozen.Footnote 65

Again, this process started from before the moment of embarkation, when, in the aforementioned written instructions from the governor of Hiroshima prefecture, Wakamiya was explicitly warned ‘not to disgrace the nation’ (kokujoku o ukezaru 国辱ヲ受ケサル) during the period of his contract. Such an admonition echoed the wider state campaigns of moral suasion in Meiji Japan – but the material space of the ship also played a key role in helping prepare migrants for their new figurative proximity to the nation-state.Footnote 66 For example, if we think back to the lists in the Japanese Foreign Ministry archives, the provenance of individual migrants was read vertically down, from prefecture to county to village: in the case of Wakamiya, from Hiroshima to Saeki to Jigozen. From the perspective of a bureaucrat in Tokyo, ‘Japan’ was so obvious a label as to be left unwritten. But my guess is that as Wakamiya left Jigozen on 25 May to begin his long journey to Honolulu, he would have ranked the relative importance of those names in reverse order. That is, Jigozen would have offered him a primary sense of belonging which was reinforced by the presence of thirty-six fellow villagers on the road to Hiroshima. But in the port of Ujina, he might have begun to feel lost among the crowd of 389 other migrants from Hiroshima prefecture; and onboard the Yamashiro-maru for the first time, en route to Yokohama, he was thrust into the same space as 276 migrants from Kumamoto and 149 from Fukuoka – two other key prefectures from which the government-sponsored emigrants hailed. True, as a native of an Inland Sea port town, Wakamiya would at the very least have previously seen people from other parts of Japan, and perhaps even conversed with them. But in the steamship, then in the Nagaura quarantine centre near Yokohama, and then during the passage to Hawai‘i, nominal compatriots were suddenly cheek by jowl.

In the absence of an onboard archive, the historian can only speculate as to what Wakamiya made of this physical proximity. For purposes of comparison, we know from the scholarship of Naoko Shimazu that long railway journeys could serve as a catalyst to new self-identifications.Footnote 67 For example, conscript soldiers called up during the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5) first embarked on what Shimazu terms a ‘journey of life’ from their respective home towns to the aforementioned Ujina port in Hiroshima, whence they would subsequently ship to the Asian frontline. As they travelled by train, the soldiers were regularly greeted by cheering crowds, whose support helped young men from otherwise diverse backgrounds begin to feel a sense of connection to ‘the nation’; they also passed key landmarks of ‘national’ culture such as the Akashi Straits, Himeji Castle, and especially – for those coming from the south-west of the archipelago – the floating shrine at Itsukushima (itself close to Jigozen). Shimazu writes that ‘the internal journey from their home town to Hiroshima played a key role in expanding [the conscripts’] geographical space of what constituted “Japan” and, in the process, effortlessly integrated these soldiers from disparate parts of the country into the common national landscape of the homeland’.Footnote 68

Transpacific crossings played a similar role for labour migrants in expanding the geographical space of what constituted ‘Japan’.Footnote 69 For the women on board the Yamashiro-maru in 1885, and for those men who had avoided compulsory military service (of whom there were many in the early 1880s), this may have been the first opportunity in their lives to inhabit the same space as other ‘Japanese’.Footnote 70 We may thus assume that the Yamashiro-maru’s cramped onboard conditions facilitated cross-prefectural communication. As Michael Ondaatje’s evocation of a 1950s shipboard passage in The Cat’s Table (2011) suggests, children were perhaps central to one aspect of this communication.Footnote 71 The antics of Nakano Tatsuzō, Nakamura Keitarō, Katō Yohei and Shiina Tatsuzō, all boys aged three, may have provided a common point of conversation for their parents, who respectively came from Fukuoka, Kanagawa and Chiba prefectures. The mothers Matsuda Tsui (Hiroshima) and Kobatake Kita (Wakayama), both aged twenty-three, perhaps bonded over their baby daughters, aged seven months and twelve months respectively. More generally, the three hours of daily deck-exercise that Irwin ordered midway through the passage would have provided other opportunities for cross-prefectural communication, as would cards and shogi (Japanese chess) games in the lower deck.Footnote 72

Just as the Atlantic slave ships were a site of ethnogenesis for an ‘African’ slave community, the mid-Meiji migrant ships furthered the genesis of national self-identification among the ‘Japanese’ passengers. For bonded people on the slave ships, Marcus Rediker argues, ‘broader similarities suddenly began to outweigh local differences’, such that cultural and linguistic commonalities became ‘crucial to cooperation and community’.Footnote 73 In a similar process, although very different physical conditions, the experience of transit may have served as a precedent for the label of ‘Japanese’ that the labourers were exposed to upon their arrival in Honolulu and then on the plantations – and that they subsequently themselves appropriated. One migrant would later recall her passage to Hawai‘i on ‘a Japanese ship’. She was in fact referring to the Yamashiro-maru’s sister ship from Newcastle upon Tyne, the Omi-maru, and the memory may simply refer to the kind of labelling that became a daily accompaniment to her life in Hawai‘i.Footnote 74 Or it may obliquely reference a process of becoming Japanese which intensified on the transpacific passage. Either way, the shipboard experience prepared the migrants for the textual tropes of ‘Japan’ articulated in the Advertiser after the Yamashiro-maru’s arrival in June 1885, or for visual tropes such as Arning’s photographs of the City of Tokio’s cohort in February.

Yet the ship also remained an ambivalent space of nation-making. The migrants continued to be divided by prefecture for administrative purposes – for example, while being transported from the Japanese quarantine station at Nagaura back to the Yamashiro-maru before departure from Yokohama. According to the very few oral histories which discuss shipboard life, the migrants tended to sleep and socialize in their prefectural groups during the passage to Honolulu – and, given the absence of a large dining room on board the ship, most probably ate in shifts with their prefectural compatriots.Footnote 75 Moreover, as many historians have pointed out, local differences remained central to the Japanese migrants’ daily lives on the Hawaiian plantations, as expressed particularly in dialect and diet.Footnote 76

How, then, should we read Arning’s photographs from February 1885 and the ‘national’ pastimes that they depict? Was what the Advertiser called an exhibition an amusing spectacle for the Honolulu hosts, and for Arning, who saw a chance to add to his nominally ethnographic visual repertoire? In an age when Meiji Japan used world exhibitions to project a certain vision of ‘Japaneseness’ internationally, was it a performance of nationhood encouraged by the Tokyo officials on board the City of Tokio, themselves conscious that the performance’s date, 11 February, was a recently inaugurated national holiday to celebrate the mythical founding of the Japanese nation? Did these Japanese government officials also hope that a celebration of wrestling would foster a sense of national belonging which the migrants were otherwise lacking in their daily lives? We cannot know for sure. But we should also not rule out that the migrants themselves may have been engaged in a moment of play. In both of Arning’s sumo photographs, the bout’s referee, whom the Advertiser refers to as announcing the result ‘with a waive [sic] of his fan’, is actually raising, with dramatic effect, a cast-iron frying pan. Does the pan for the fan thereby undermine the supposed seriousness of the exhibition or the patriotic celebrations of the participants?

Such ambiguities abound in the photographic archive – which, in Arning’s case, is to be found in Hamburg, Germany.Footnote 77 To acknowledge them is better to understand the artifice of the migrants’ reception and representation upon arrival in Honolulu. And they are also important because of the closing sentences of the Advertiser’s report of the 11 February festivities. Having noted that there had been ‘a fine display of muscle, pluck and good nature’, the newspaper recorded: ‘Mr. J. D. Strong took some instantaneous negatives, besides securing some other fine studies.’ In other words, Strong was as active as Arning in the immigration depot on 11 February. And, though it required a sharp-eyed student to point this out to me, three of the figures who also appear in Arning’s aforementioned group photograph are undoubtedly the models for the foreground family in Strong’s Spreckelsville painting. They are the standing man, hands on hips; the seated woman with partially exposed breasts; and the small boy whose cropped hair is rather a blur (Figure 2.4).Footnote 78

Figure 2.4 Photographic models for Strong (see also Figures 2.1 and 2.3).

Nobody should be surprised that painters use models, nor that they apply some artistic licence in departing from those models. The point here, to use an anachronism, is rather that Strong’s effective ‘photoshopping’ of his models into a Maui context was a deliberate attempt to gloss over the emerging archival record about the aforementioned maltreatment of ex-City of Tokio labourers in the Hawaiian Islands. Consider the public relations timeline. The self-proclaimed architects of the government-sponsored programme, Walter Gibson and Robert Irwin, imagined immigration on an ‘industrial’ scale and the transformation of the kingdom by ‘tens of thousands of Japanese families’. (‘Certainly no public man in this Kingdom has labored more assiduously to make Japanese immigration a success than His Excellency Mr. Gibson’, the Advertiser claimed.)Footnote 79 True, not everyone in Hawai‘i felt so sanguine about this prospect, as the spat between the Advertiser and the Hawaiian Gazette over the ‘Asiaticizing’ of the islands demonstrated.Footnote 80 But if anything were likely to kill the programme in its infancy, it would be the lack of supply from Japan rather than the opposition of certain anti-government constituencies in Hawai‘i. And so, only a few weeks after he had accompanied the City of Tokio labourers to Hawai‘i in February 1885, Irwin seems to have commissioned Strong to paint the newly arrived Japanese as a gift to the Meiji emperor. We can only guess at his motivations, but presumably if he could offer the emperor a visual manifestation of the extent to which Japanese subjects were contented in the kingdom, then he might hope for an increased flow of labourers. Thus, the consul and the painter, together with Strong’s studio partner, the equally renowned Jules Tavernier (1844–89), toured Maui in early March.Footnote 81 They visited the Wailuku, Waikapu, Pā‘ia and Spreckelsville plantations, and upon their return to Honolulu, Strong publicly displayed – at a dinner given by Gibson in honour of Irwin on 11 March – several pre-studies, including ‘a sketch of a picture, of Japanese at work in the cane fields at Spreckelsville’.Footnote 82

But the problem with this report was that no ex-City of Tokio Japanese had been posted to Spreckelsville. The first government-sponsored labourers to work there would be the ex-Yamashiro-maru migrants – in fact, the whole 276-strong cohort from Kumamoto prefecture (275 men, one woman, and no children, exposing the fallacy of Strong’s composition). They would be picked up from Honolulu on 21 July 1885, nearly two weeks after the Advertiser’s article on Strong’s completed painting.Footnote 83 So Strong did not and could not have sketched any Japanese on Spreckelsville. Most likely, given his recognizable if somewhat romanticized depiction of the Maui landscape (the sketches do not survive), Strong may have studied the Japanese at work in the cane fields of Pā‘ia, which neighboured Spreckelsville.Footnote 84

If Irwin or Gibson or anyone else in the Hawaiian government had been hoping to appeal to Japan to send more labourers, however, then Pā‘ia was not the place to paint. As we have seen, disputes there about ‘rough handling’ were already beginning in March 1885 – disputes which would lead to a Hawaiian government investigation of the labourers’ complaints in April. Indeed, reports of maltreatment in Pā‘ia, in Haiku and in numerous other plantations beyond Maui were arriving at the Japanese consulate in Honolulu and from there being forwarded to top a growing pile of paperwork in Tokyo. All the more urgent, then, that the Meiji government be presented with a ‘fine representation of a sunny, thriving, hard-working plantation scene’. Without question, the plantation represented could not be Pā‘ia, given the troubles there – and also given that Pā‘ia was owned and managed by Samuel Thomas Alexander (1836–1904), son of a first-generation New England missionary and active in opposition politics to King Kalākaua. But Spreckelsville, owned by the king’s close ally, Claus Spreckels (1828–1908), would do nicely.Footnote 85 Spreckels would get – to use another anachronism – ‘product placement’ for what would, by the early 1890s, be the biggest sugarcane plantation in the world.Footnote 86 And the king – who, if the Advertiser’s July report is to be believed, seems to have taken over the painting’s commission from Irwin – would have a visually striking means of appealing to the Japanese emperor and his government for more labourers.

We’ve come a long way from the actual experiences of those labourers – of men such as Kodama Keijirō, who started working on Spreckelsville in July 1885. But that, it would seem to me, was exactly the point of the painting: it should distract the viewer from the realities of plantation life for the first groups of government-sponsored Japanese in Hawai‘i. It should divert our interests away from the evidence accumulating in the archives that all was not as equal or as humane as it might seem.

As one archival counterpoint to these complex political agendas, we may note that Spreckelsville itself became the focus of worker ire within a month of Irwin’s returning with the painting to Japan. Unfortunately, there survive only the reports generated by the authorities: for example, a court case in September 1885 against seven Kumamoto workers, named and numbered in the court record. Here, in response to the labourers’ claims that they were sick, a Japanese doctor testified that they were not, and that they could go back to work; the Japanese were fined US$3.75 each. Another court summary from October 1885 details the case brought against twenty Spreckelsville Japanese who were accused of gambling.Footnote 87 And, a month later, reports received by the Board of Immigration described ‘trouble arising between Japanese Immigrant laborers on the Spreckels Plantation and their employers’. The latter were investigated by the Board’s secretary, Mr Cleghorn, who instead reported from Spreckelsville of labourers ‘up at night gambling, long after the regulation hour of nine o’clock, at which time lights are ordered put out’. Cleghorn’s interlocutor and translator at this time, as also in the Hawaiian courts in the previous months, was a Japanese immigration inspector called Itō. Channelling Itō, Cleghorn reported that ‘the Japanese laborers on Spreckelsville come from a district in Japan where there was a good deal of trouble in 1877’ – that is, the Satsuma Rebellion against the Meiji government, fought partly in Kumamoto prefecture.

And so we are back at the problem of framing: Itō’s disdain for the class and regional background of the Spreckelsville workers framed Cleghorn’s reports, which then constitute the main surviving written record of Japanese life on the plantation. I’m not sure which is more problematic for the historian: Strong’s commissioned fiction or Cleghorn’s reported facts. But I am sure that, in trying to position the Spreckelsville labourers between the poles of alleged contentment and demonstrable recalcitrance, we are no closer to understanding how Kodama gazed out at the world.Footnote 88

Meanwhile, a second archival counterpoint to the framing of ‘Japanese Laborers on the Plantation in Spreckelsville’ became possible in 2017 thanks to the launch of Stanford University’s Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection. Among the many overseas Japanese newspapers digitized in the collection is the Honolulu-based Nippu jiji, which in February 1935 published a bilingual supplement to celebrate the ‘golden jubilee’ of Japanese immigration to Hawai‘i. This, too, engages in its own framing of Japanese and Hawaiian history: the first page’s subheading, ‘They Till the Soil, and Out of Their Sweat a New Territory Is Born’, rings of the pioneer imagination of settlement in the Pacific which was so prevalent in expansionist Japanese discourse by the 1930s (and which lived on in the Taitō ninety-year history).Footnote 89 But for me the most interesting part of the supplement is the brief life histories of surviving City of Tokio and Yamashiro-maru migrants. We learn, for example, that five of the original Kumamoto contingent to Spreckelsville were still alive and working on the islands in 1935: as builders, coffee growers, pineapple labourers or simply raising their own vegetables. There are photos of these five men, all in their seventies, all in formal jackets and ties. Their hair is grey, their faces lined and tanned after years working in the sun. Back in Hawai‘i in 2011, I had assumed I would never find photos of any of the Yamashiro-maru migrants. But now they gaze out of the pictures and out of my computer screen. These men were the real protagonists – and survivors – of the history embedded in Strong’s painting.

(Re)framing

When Robert W. Irwin accompanied Strong’s large oil painting and the King Bros’ even larger frame back to Yokohama on the Yamashiro-maru in July–August 1885, he may already have known that his intended framing had failed. Not in the sense of the government-sponsored programme: to the contrary, its future was in a better place than it had been on the outward voyage. For after visiting several plantations, Inoue Katsunosuke had placed several formal demands on Gibson, including that ‘no overseer (luna) will be allowed under any circumstances to put his hands in any way on any Japanese for any purposes whatsoever’. When Gibson agreed, and also established a Bureau of Inspection under the Board of Immigration (the very bureau which would later send Itō to Spreckelsville), the course was set for formalizing the programme through the Hawaiian–Japanese Labor Convention of January 1886.Footnote 90

Rather, the failure of the Strong painting concerned how it positioned Japan in the world. The whole tenor of the younger Inoue’s diplomatic mission to Hawai‘i had been set by a letter he carried in June from his adopted father, the foreign minister Inoue Kaoru, for delivery to Gibson. Welcoming the likely future expansion of Japanese emigration into the kingdom, Inoue senior sought to raise various matters of concern, including the need for more Japanese interpreters on the islands. But the main thrust of the letter concerned Chinese immigration to Hawai‘i. In short, he stated, Japanese emigration would be dependent on the Hawaiian government restricting Chinese immigration. This was because ‘His Imperial Majesty’s Government [Japan] are not inclined to regard with favor the association of Japanese and Chinese. In other places such association has been a fruitful source of embarrassment’.Footnote 91 Here, in the polite cursive script of diplomatic missives, was the sharp end of a mid-Meiji discourse of redefining ‘civilization’ away from the hitherto centrifugal power of China and framing it instead within tropes of Euro-American ‘progress’. The doyen of such ‘civilization’ debates was the journalist Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835–1901), whose popular newspaper had indeed published an essay with the title ‘Casting Off Asia’ (Datsu-A ron 脱亜論) in March 1885, arguing that ‘the spirit of [Japan’s] people has already moved away from the old conventions of Asia to Western civilization’.Footnote 92 Irrespective of whether Irwin himself had read the essay, he channelled its spirit in his onboard letter to Gibson of 25 June 1885 (see Chapter 1), in which he claimed that ‘Japanese people have nothing in common with India and China’.

But Strong’s painting undermined this claim – firstly through the figure of the seated child. ‘Excellent’ though the Advertiser suggested the ‘little baby’ [sic] was, its ‘shaved head and side-tufts of black hair’ identified it as having a ‘Chinese-boy’ (karako 唐子) haircut. As David Ambaras has shown, popular sensitivities about children were acute in the Meiji period in light of reports about the abduction of Japanese children for sale in China.Footnote 93 Thus, whatever the reason for Strong’s artistic licence in adapting his model’s original immigration depot pose, there could be no denying the fact that the painting’s foreground child embodied exactly the kind of associational ‘embarrassment’ which the Japanese foreign minister sought to avoid. This, I would suggest, is one reason why Strong’s painting never made it to the Meiji emperor, either as a ‘handsome present’ from King Kalākaua or as a gift from Irwin – and one reason why Irwin never displayed it publicly after 1885.Footnote 94

Another reason for Irwin’s likely sense of failure was the foreground woman’s exposed breasts. Assuming Strong took negatives of the same group which Arning photographed (or that Strong based his protagonists directly on Arning’s image), then we are confronted once again with the question of visual performance. Bearing in mind Arning’s other image of half-naked Japanese women waiting to bathe, the doctor may have staged the exposed mother in order to frame eroticism within the genre of ethnographic observation.Footnote 95 Equally, it is possible that the women in both photographs presented themselves ‘naturally’, behaving according to the social mores of rural Japan in which the exposure of breasts during public bathing or indeed the performance of manual labour was no source of shame (see also Figure 6.3). That public nudity persisted in the contemporaneous Japanese countryside was confirmed by the Victorian traveller Isabella Bird (1831–1904), who noted in the late 1870s that ‘the Government is doing its best to prevent promiscuous bathing’ in rural areas.Footnote 96 And yet Bird’s language reveals exactly the problem that Irwin confronted as he carried the painting on the Yamashiro-maru: nudity was ‘promiscuous’, and it was associated in Europe and North America – as also by the New England missionaries in 1820s Hawai‘i – with ‘uncivilized’ Indigenous peoples.Footnote 97

Thus, Strong’s painting undermined Irwin’s own claim, written from on board the ship in June 1885, that ‘Japan is progressive and rapidly becoming a Western Civilized State’. Indeed, in an interview which the president of Taiwan Sugar, Takechi Tadamichi, gave in the early 1930s for a new book on the history of the Japanese sugar industry, he recalled that ‘during his lifetime, Irwin would look at the painting, see the Japanese woman with her breast exposed, and feel it was shameful [haji 恥] to the Japanese people’. For this reason, Takechi requested that the painting not be reprinted in the book.Footnote 98

There may also have been a third reason for Irwin’s discomfort, one which additionally accounts for the painting disappearing from view for more than forty years after arriving in Japan. When Mitsui Sugar commissioned the work’s restoration in 2017, it became clear that the man and nursing woman’s faces were not ‘unmistakably Japanese’. Compared to the original Arning photograph, they both featured slightly wider eyes, higher and more rounded cheeks, fuller lips and more pronounced noses. Perhaps such judgements lie as much in the beholder’s eye as in the painter’s brush. But the facial ambiguity of Strong’s protagonists, who might as equally have been Native Hawaiians as Japanese, does speak to a final problem for Irwin and a final framing for us. For Irwin, any hint that the painting’s future viewers – any viewer in any circumstances, not merely the Mikado or his ministers – could possibly have construed ‘the Japanese’ as Pacific Islanders would have profoundly undermined Meiji Japanese claims to a higher (European) civilizational status. According to Fukuzawa Yukichi, for example, the history of the ‘Sandwich Islands’ only began with their ‘discovery’ by Captain Cook in 1778.Footnote 99 By this logic, Native Hawaiians were allegedly a people without history prior to their interactions with Euro-American ‘civilization’. If the nominal Japanese depicted by Strong might in any way be construed as synonymous with such people, then the image would fundamentally undermine Meiji intellectuals’ claims to ‘progress’ – claims embodied by the Yamashiro-maru itself.

Given these ambiguities, perhaps we may conclude that Native Hawaiians were not completely absent from Strong’s work after all. This is important because the overlooking of Native Hawaiian history, and the marginalization of Native Hawaiian voices, were not just discursive projects pushed with ever greater intensity by would-be colonialists in the 1880s and 1890s. They are also trends which continue in secondary scholarship: less so in histories of Hawai‘i’s relationship with the United States, which have begun to redress the long historical bias towards English-language sources, but rather in historical accounts of Asian immigration to the archipelago.Footnote 100 The ambiguity inherent in Strong’s key protagonists – that is, the difficulty in ascribing them ‘Japanese’ or ‘Hawaiian’ characteristics, let alone ‘unmistakable’ ones – thus points to the historian’s need to find yet more archival starting points, thereby to reframe the complex histories depicted in this painting.Footnote 101

One alternative archive is the huge collection of nineteenth-century Hawaiian-language newspapers which have now been digitized. My own language deficiencies have precluded my taking the lead in conducting such research, but an assisted trawl of newspapers from 1885 suggested that there is much work to be done in understanding how different constituencies within Native Hawaiian society debated the inauguration of the new government-sponsored programme. In a February 1885 leader for the Honolulu-based Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, for example, the unknown writer begins by framing the arrival of the City of Tokio Japanese with reference to an earlier, much smaller migration from 1868. This was the group commonly known by its ex post facto Japanese name, the Gannenmono, referring to the ‘first year’ (gan’nen 元年) of the new Meiji regime. The Gannenmono, comprising fewer than 150 labourers, are generally considered to be a failed first experiment in mass migration, one which explains why Meiji leaders waited almost twenty more years before sanctioning a new Japanese–Hawaiian programme in 1885.Footnote 102 Yet for the Ka Nupepa Kuokoa author, the City of Tokio labourers were a reminder ‘of the Japanese workers who first arrived here in Hawai‘i. The uniting of these peoples with our own people was pleasant, and the generation that emerged from the mixing with Hawaiians possesses fine strength.’ In other words, the arrival of more than 900 new Japanese in February 1885 was an opportunity to ‘help perpetuate the population of the Hawaiian Islands, at its previous level, through intermixing with the true people of this land’.Footnote 103

Here, then, was a vision of Japanese–Hawaiian ‘intermixing’ (awiliwili) which arguably found its visual counterpart in the faces of Strong’s nominally ‘Japanese’ labourers. Moreover, Ka Nupepa Kuokoa’s hopes for the new programme grew out of its insistence that Japanese immigration was part of a well-formulated Native political agenda for the kingdom, one that would help ‘the true people of this land’ (me ka lahui ponoi o ka aina nei). Immigration was related to King Kalākaua’s policy of ‘increasing the nation’ (hooulu lahui).Footnote 104 Referring to the ‘carefree season of death’ that continued to blight the Native population, the newspaper argued that the king, queen and all the chiefs had sought new ways to strengthen the nation:

Due to the shadow that persistently covers the Hawaiian nation and the lack of resurgence of the people proper [lahui ponoi], it is as if the thought to increase has grown, through mixing with those belonging to the outside. That is how we think now, upon the arrival of this new people from the islands of Japan.

Though it be a single article, the Ka Nupepa Kuokoa leader offers rich departure points for a reframed analysis of the government-sponsored programme. First, it suggests that the traditional historiographical view – that the main Hawaiian motivation for the programme was to address labour shortages in the sugar plantations – needs revision. Instead, the article claims that the main reason for inviting the Japanese was to repopulate the decimated Native population.Footnote 105 True, repopulation was not mutually exclusive with the sugar planters’ needs. But historians of Japanese–Hawaiian migration should not assume that the planters’ interests were synonymous with an undifferentiated Hawai‘i: there were multiple different agendas at stake, including those of Native Hawaiian actors. Thus, secondly, the article calls for different protagonists to be foregrounded in the history of Japanese–Hawaiian relations from those on whom I have focused thus far. As we have seen, the Advertiser would state in July that ‘no public man in this Kingdom has labored more assiduously to make Japanese immigration a success than His Excellency Mr. Gibson’. But such claims, according to the Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, were nothing less than the ‘grand misidentification of the people responsible for this work’. The real protagonist of the government-sponsored programme, ‘the father who sought, who strove until success’, was King Kalākaua himself.

* * *

My other attempt to reframe the archival history of the Yamashiro-maru and its migrant passengers in 1885 was, like the Hawaiian newspaper translation project, a group effort. In 2013, a British man called Graham Corkhill contacted me out of the blue to find out more about my interest in the Yamashiro-maru, and eventually to offer the long-term loan of a constructor’s model of the ship. Also built by Armstrong-Mitchell in 1884, the nearly two-metre-long gleaming hull, encased in glass, suddenly made it possible to understand why port newspapers in Kobe or Honolulu or later Australia so often labelled the Yamashiro-maru ‘handsome’. Spurred by the ship’s presence in Zurich, the then-director of the Johann Jacobs Museum, Roger M. Buergel, suggested we try to loan the Strong painting as well (first we needed to find it!), and some reproductions of the Arning photos, and perhaps a plantation labourer’s yukata or two – and gradually the idea for an exhibition took shape.

Opening in February 2018, ‘Ein Bild für den Kaiser’ (A Painting for the Emperor) displayed Strong’s painting, frame and all, in public for the first time since 1986 and for the first time out of Japan since July 1885.Footnote 106 The painting stood in one of the small museum’s ground-floor rooms, accompanied by a pair of late nineteenth-century rice-straw sandals that a Japanese labourer once wore in the Hawaiian canefields. Downstairs, in the basement exhibition rooms, we juxtaposed the ship model with the Arning photographs, with plantation working clothes, and with subterranean coal paintings by Yamamoto Sakubei (e.g. Figure 6.3). Roger Buergel also commissioned three contemporary artists to reflect on the themes of migration and belonging: one, Jürgen Stollhans, composed a charcoal rendering of the pier-crossing Japanese (Figure 2.2) as a wall mural. This would be, or so I hoped, a different kind of archival space in which to reflect on historical passage and landfall. We invited visitors to walk between image and text, painting and photography, song and silence; and especially between black coal and white sugar.

The exhibition was the closest I ever got to a physical manifestation of the in-between archive I have been exploring in this chapter – but there was someone still missing. And so, on a pre-planned family trip to Japan in the middle of the exhibition period, I took a day to go to Kumamoto, hired a car, and from there drove up the Ariake Sea coast to the tiny hamlet of Orisaki.

As soon as I arrived, I was struck by the folly of what had, to that point, seemed like a really good plan. Said plan was to cold-call one, or possibly all three, of the present-day Kodama households in Orisaki, households I knew existed from a land registry map I had consulted in Tokyo a few years previously. To try and delay the inevitable failure I suspected was coming my way, I first strolled around the local shrine, noting in passing the name of a Kodama Chōmei on a torii (ceremonial gate) dating from 1915. Following a narrow path up towards a cluster of houses, I noticed that one of the Kodama addresses had a small office annexe in its spacious garden – and before I knew it, a twinkly-eyed man in his early sixties was standing before me, turning my photos of a Hawaiian graveyard in his hands.