A Statement

Hers is an unlikely story of archival survival:

On the 29th day of November 1897 in the presence of Torijiro Satow and Gyusaku Sugiyama –

Usa states –

My name is Usa Hashimoto –

I am twenty one years of age –

As also for the Mossman Japanese, I came searching for Hashimoto Usa at the turn of the seasons in November 2013 – from autumn to winter in Europe, from spring to summer in Australia. In Canberra, I had found a reference to her statement in an article by David Sissons (1925–2006). Diverted from classics to the study of Japanese in the last year of the Second World War, Sissons had worked as a defence interpreter in war crimes trials in Morotai (Indonesia) for several months in 1945–6, before being posted to work as a translator for the British Commonwealth Force in the Allied Occupation of Japan. After his post-service university training, Sissons’s primary expertise came to be in political sciences and international affairs, but he also began to study Japanese–Australian history in the mid 1960s.Footnote 1 In 1977, he published two groundbreaking essays on what – given his primary work on defence, immigration and trade policies – might at first seem to be a counter-intuitive interest in the history of Japanese prostitutes in Australia.

Sissons was an extraordinary scholar, whose work was foundational to new understandings of Japanese–Australian relations. His former students describe him as ‘meticulous’ and ‘detailed’, a ‘modest’ man, shy to the point of being unwilling to publish on a particular topic until convinced he had covered every empirical base. I could sense this myself from the day I spent among his research papers in Canberra’s National Library of Australia: typewritten letters from all over the world testified to his exhaustive rigour in following up on every possible archival trail.Footnote 2 All of which makes it even more unusual that Sissons’s reference to Hashimoto Usa in his first article on prostitutes contained a minor error.

Though insignificant in and of itself, the act of trying to correct Sissons’s mistake took me into a much more problematic history of how women like Hashimoto had been categorized by officials in late-1890s Australia and Japan, and how, in that bureaucratic process, their voices had often come to be lost. According to Sissons, Hashimoto’s testimony could be found in ‘Q.S.A., Col. A/822, 97/15833’.Footnote 3 But when I later took the lead from ‘Q.S.A’ to fly to the Queensland State Archives in Brisbane, staff there were bemused by the ‘Col. A/822’ reference. If, as Sissons’s citation of the document indicated, Hashimoto’s statement had been recorded on Thursday Island in December 1897, then this must be a mistake, for the ‘COL’ series referred to documents only up to August 1896, after which it had been replaced by ‘HOM’. To add a complication, the Queensland State Archives referencing system had recently been overhauled, such that even if ‘Col. A/822’ for 1897 had existed when Sissons was writing in the 1970s, it would now have a new identification number. But not to worry, the archivists reassured me: ‘97/15833’ was a top number – a kind of watermark through which each document was embossed with the stamp of colonial authority.Footnote 4 So all we needed was to find the Home Office’s Register of Letters (HOM), look up the 15,833rd piece of incoming correspondence which was logged in (18)97, and check what ‘action’ had been performed on that item. In this case, the action – recorded in tiny, cursive handwriting – was ‘HOM/A15 Home Secretary’s Department, General Correspondence 1897, Nos. 15006 to 16595’. So now, the archivists said, I could look up ‘HOM/A15’ on the Archives’ online catalogue for the new identification number (ID 847553); I could then order the folder to my reading room desk – and Bob’s your uncle.

But Bob was not my uncle. After checking and rechecking the home secretary’s incoming correspondence for this range of 1897 papers, I could find no trace of 97/15833 and thus no trace of Hashimoto Usa. Wherever Sissons had found her testimony, she was now lost in the archive.

The extent of my disappointment was irrational. I had a hunch that this young woman, whom Sissons described as a ‘recently arrived prostitute’ in December 1897, might have travelled on the Yamashiro-maru to Thursday Island, in the very far north of Queensland. This was where Japanese migrants had disembarked in large numbers throughout the 1890s, such that the Townsville Daily Bulletin would label the island ‘an appanage of the Mikado’s kingdom’ in 1898;Footnote 5 and I knew that the ship had docked there in early November. Summarizing Hashimoto’s evidence, Sissons explained that she had come from Nagasaki via Shanghai and Hong Kong, where a financial transaction had taken place with the proprietor of a ‘lodging house’. From Hong Kong, she and other Japanese women had been escorted under the cover of midnight, without passports, to Thursday Island, and sold to a brothel-keeper called Shiosaki. He had paid her escort £100 sterling, which Hashimoto herself now had to repay to Shiosaki.

This was a story both extraordinary and all too ordinary for the time, as this chapter will show. But in the form through which I had accessed Hashimoto Usa’s account, it remained at one step removed: Sissons had paraphrased her words, whereas I wanted to know what she herself had said and what language she had used (I assumed her deposition was in Japanese). That was one reason why I wanted to get hold of 97/15833 – and also to see if my hunch about the Yamashiro-maru was correct.

Although Hashimoto’s testimony was absent, the folder I had requested on that November morning – ID 847553 – did nevertheless reveal much about the bureaucratic mindset which had produced her paperwork. Here was a debate in the Cairns Municipal Council, from September 1897, in response to calls by various aldermen to ‘stamp out this disgrace to our civilization’ – namely, ‘Japanese houses of ill fame’. Here was one alderman claiming that ‘when he was in the South recently he found that a number of Japanese women had invaded Brisbane’. And yet here was also the Cairns sub-inspector of police, in a letter to a colleague in Cooktown, begging to state ‘that the whole subject has been very much exaggerated’.Footnote 6

The sub-inspector’s letter led me to request a folder of police correspondence on ‘Japanese women’ from 1897, where I found a memorandum from the Queensland police commissioner, calling for all of the colony’s sub-inspectors to furnish information on (i) the number of Japanese women in their respective districts, (ii) the women’s marital status, and (iii) their ‘general occupation’. Next in the folder was a stream of telegraphed responses: sixteen Japanese women in Cairns, four in Cooktown, one in Port Douglas, four in Townsville, three in Halifax, nine in Mackay and one in Ingham, ‘all prostitutes except consuls wife at Townsville’. And here a letter from the inland settlement of Childers, detailing six ‘places’ and a total of fifteen Japanese females. All claimed to be married – six of that group were living with their husbands, ‘one in each house’, and the others were boarders while their husbands worked on Lady Elliott Island. But the reporting sergeant, referring to the alleged behaviour of Pacific Island labourers in the pejorative language of the time, believed otherwise: ‘from the fact that Kanakas are Constantly resorting these houses, and although [the women] Claim their husbands sends them money, he believe that they get their living by Prostitution’.Footnote 7

A few days later, on 8 November 2013, I requested a folder concerning Japanese immigration into Thursday Island. Here was the rawest form of frontline data collection, namely regular telegrams from the island’s government resident, John Douglas (1828–1904), reporting on new arrivals: on 24 July 1897, ‘Tsinan yesterday brought twenty one japanese from Hong kong males fifteen 15 females six 6’; on 4 August 1897, ‘The Yamashiro Maru brought five 5 Japanese males and one 1 female for Thurs Island from Japan’; on the same day, the Changsha, bringing two males and two females from Hong Kong; and so on, through the southern hemisphere spring and until the end of December – the Omi-maru, the Airlie, the Nanchang, the Chingdu, the Tainan.Footnote 8

This growing pile of telegrams, memoranda, letters and reports added up to what Bill Mihalopoulos has called an ‘ocular regime’, whereby government bureaucrats were directed to keep an eye on a particular subset of the population. As a consequence, that group became more visible to officialdom, leading to further calls for observation and eventual government action.Footnote 9 Mihalopoulos uses the ocular analogy in reference to the strategies by which Meiji bureaucrats began to classify migrating women. He draws on Ian Hacking’s analysis of how the human sciences observe, record, and thereby ‘create kinds of people that in a certain sense did not exist before’, to show how a type of mobile Japanese woman was ‘made up’ in late nineteenth-century Tokyo governmental circles.Footnote 10 As we shall see, this ‘unsightly woman’ was a new category, fit for the purposes of statistical analysis and policy intervention. Such categorizing was as equally evident in Queensland as in Japan. True, the Cairns sub-inspector’s warning of a problem ‘very much exaggerated’ demonstrates that the new ocular regime was not uncontested; and the marriage claims of the alleged Japanese wives in Childers suggests that the targets of the regime occasionally devised strategies to thwart bureaucratic classification.Footnote 11 But still, what the paperwork before me evinced was the objectification of Japanese women by the archival eye.

And then I found her. The dozen or so beige papers, taller and thicker to the touch than your standard A4 sheet, and bound by a piece of string in their top-left corner, were out of place in yet another overflowing folder – sandwiched between correspondence over Japanese labourers in 1894 on the one hand, and a table of Japanese returnees, deaths and deserters from Queensland in the period 1892–8 on the other. At first, I was thrown by the forward-leaning cursive handwriting, in blue ink, and by the addressee: ‘To the Honorable / The Government President / Thursday Island’. This imaginary government title suggested that the original author – the papers were marked ‘Copy’ – had been unsure how to address British colonial authority. And I was also thrown by the fact that the letter came from a woman called Oyaya, ‘living at 29 Malabar Street Singapore’. But the top number was right – a red stamp, ‘Home Secretary’s Office Queensland / 13.Dec.97 / 15833’ – and the third paragraph set my heart racing:

In the end of July this year your Petitioner’s sister named Usa left Nagasaki Japan and proceeded to Singapore via Hong Kong on a visit to join PetitionerFootnote 12

I read on, noting Oyaya’s concern that her sister had been ‘kidnapped from Hong Kong and taken to Australia’, where she had been ‘forced to prostitute herself against her will’. I don’t really believe in ‘the dead waiting to be chosen’, as Alain Corbin has suggested.Footnote 13 But as I turned the final page of Oyaya’s petition – signed by the mark of her finger – I noticed that it had been composed on 8 November, the same date I had rediscovered it in the archives. And, after the petition, here came Usa’s own voice: ‘My name is Usa Hashimoto. I am twenty one years of age.’

Or so I wanted to believe in that moment of archival euphoria. I wanted to believe that Hashimoto’s first-person singular might resist the logic of Queensland’s ocular regime, might be an example of an individual speaking back to the bureaucrats whose language of civilization, invasion, ill fame and disgrace had framed her archival appearance. An ‘I’ for an ‘eye’.

But it was not that simple. For a start, the order of her names revealed a gap between the written and spoken words: the given name (Usa), followed by the family name, was evidence that the transcriber, who would turn out to be the aforementioned Thursday Island government resident John Douglas, had already edited her words to suit an English-reading audience. The ‘presence’ of Torajiro Satow and Gyusaku Sugiyama (that is, Satō Torajirō and Sugiyama Gensaku) would be explained at the end of Hashimoto’s statement: they were her translators from Japanese to the English-language document I had in front of me (her words in Japanese were never recorded).Footnote 14 And, as I shall argue, the translators served as something like court interpreters too, intervening in subtle ways to drive, block and position Hashimoto’s testimony for the listening (and questioning) John Douglas.Footnote 15

These were the beginnings of what Carolyn Steedman has called archival ‘degrees of separation’: Hashimoto (Japanese, spoken) via Satō and Sugiyama (English, spoken) to Douglas (English, written), and Douglas to me.Footnote 16 But even that was an oversimplification. A few hours later, having put Hashimoto to one side and ploughed on through more correspondence about labour shortages in the Queensland sugar industry, I found the still-missing top page to the Oyaya/Usa paperwork (see Figure 5.1). This was a ‘Memo’ by John Douglas, forwarding the petition and statement to home secretary Sir Horace Tozer (1844–1916) and noting that the case ‘represents a curious and not very attractive phase of Japanese colonization as at present existing’. Here was yet another framing of Hashimoto Usa’s words, the imposition of an interpretative filter before Sir Horace or any of the rest of us could even read her account. And, with Sir Horace’s initials and perpendicular marginal comments (‘Noted and with this immigration other similar practices will happen as of course’), and with the vermilion filing instructions and official stamp of the home secretary’s office, there were at least a couple more degrees of reader separation between Douglas and me. Steedman argues that such separation renders the historian ever more ‘inclined to hear voices’.Footnote 17 True, the archive may be a tonal void in terms of physical speech from the past. But, she continues, our handling of hard copies, manipulation of microfilm readers, transcriptions of texts, awareness of reading room whispers and even consciousness of travelling long distances to the archives – these actually constitute acts of training the ear to hear.

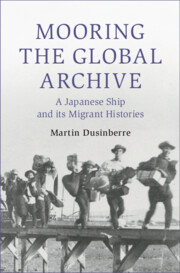

Figure 5.1 ‘Correspondence re alleged abduction of a Japanese woman’, 1897. ITM861850.

In the case of Hashimoto Usa, there were plenty of voices in the room: Satō, Sugiyama and Douglas, for a start, whose worldviews I layer into her statement in the following pages. The problem was, all these voices belonged to men. Douglas (University of Durham) and Satō (University of Michigan) – hell, Sissons (Melbourne) and me (Oxford) – typify what Virginia Woolf called the ‘well-nourished, well-educated, free mind, which had never been thwarted or opposed, but had had full liberty from birth to stretch itself in whatever way it liked’. This was the male writer, the first-person singular whose ‘I’ was a ‘straight dark bar’ casting its shadow over the page:

One began to be tired of “I”. […] But – here I turned a page or two, looking for something or other – the worst of it is that in the shadow of the letter “I” all is shapeless as mist. Is that a tree? No, it is a woman. But … she has not a bone in her body, I thought, watching Phoebe, for that was her name, coming across the beach. Then Alan got up and the shadow of Alan at once obliterated Phoebe.Footnote 18

If, as Steedman concludes, the voices we claim to hear in the archive are ultimately those of the historian, then my channelling of them would be to impose my own straight dark bar on Hashimoto’s words (or, rather, on the version of her words left by her male interlocutors). In analysing Hashimoto’s statement, I could certainly try not to obliterate her; but then I ran the opposite risk of appearing as her one true saviour, a Rankean prince kissing life into the archived dead.Footnote 19

Between obliteration and osculation, I was faced with the structural problem of how to write about Hashimoto’s words. But as Noelani Arista has argued in her analysis of the first Hawaiian-language translations of the Gospel in the 1820s, historians should both read and listen to written texts which were once animated through speech. In observations pertinent also to the Thursday Island encounter between Hashimoto Usa and her Euro-Japanese interlocutors, Arista suggests that such listening will enable historians to ‘attune themselves to the meaning-making systems of not just Hawaiians, but also Euro-Americans, so that we do not miss in which words and whose speech mana (spiritual force) inhered in a culturally diverse world of encounter – where speech and writing worked simultaneously to craft or dissemble power and authority’.Footnote 20

To listen and not just to read, I attempt a two-pronged approach. At one level, I outline the basic story of a woman coming across a beach by structuring the chapter around Hashimoto’s account in the order she narrated it – if, in fact, she determined that order. In terms of empirical value, her statement unshadows a very different history of Meiji Japan’s engagement with the outside world, and of the routes and passages therein, to the histories I have recounted in previous chapters. Along the way, Hashimoto reveals herself to be a factually accurate witness to the phenomenon of undocumented women crossing the fluid borders between Asia and the Arafura Zone, and she disproves the thesis that such mobilities in the late nineteenth century ‘may have been nearly frictionless’.Footnote 21 But although the facts of her passage are important, I am secondly interested in the archival tales historical actors tell, and the voices in which they narrate those tales. Everyone turns out to be a storyteller in the reconstruction that follows, some more flamboyantly than others.Footnote 22 Such stories both provided the data that underpinned the creation of the written archive’s ocular regime, and informed its multiple textual genres – including telegraphs, letters, petitions, bureaucratic reports, purportedly first-person testimonies and newspaper clippings. But in Hashimoto’s case, the provision and withholding of information equally gave her a chance to challenge the male gaze: this was her mana. Contextualizing her history with that of other mobile Japanese women, I try to show where and how her statement performed this challenge in November 1897 – and why, in a world of increasing source digitization, her words and speech remain important today.

Doubtless there will be much to critique in the shadow which my first-person singular casts over the already gendered structures of Japanese migration archives.Footnote 23 But what follows is at least a new attempt to reply to Oyaya’s ‘humble petition’ for ‘due enquiry [to] be made into the above case’.

I Was Born at Nishiyama

My name is Usa Hashimoto –

I am twenty one years of age –

I was born at Nishiyama Nagasaki Japan –

Nishiyama is at the northeastern edge of today’s Nagasaki, about two kilometres as the bird flies from Dejima, the island on which for more than two centuries European employees of the Dutch East India Company were confined. On Google Streetview from pandemic lockdown in Europe, I can read that the Nishiyama shrine is famous for its winter-flowering cherry tree, planted in January 1897 and now some seven metres tall. The shrine grounds also boast a pomelo tree, planted from a seed brought on a Qing dynasty ship from Java in 1667.Footnote 24

In other words, the world beyond Japan was tangible to the people of mid nineteenth-century Nishiyama. If they had strolled up Tateyama, a low-lying mountain to the village’s north, they could have gazed over the great vista of Nagasaki Bay, a seascape synonymous with Tokugawa Japan’s connections to China, Southeast Asia and beyond to Europe (see Figure 5.2). Indeed, a party from France led by the eminent astronomer Pierre Janssen (1824–1907) had set up base on nearby Mount Konpira in December 1874 in order to observe the transit of Venus – the first such transit since 1769, when Captain Cook had been sent by the British Admiralty to Tahiti.Footnote 25 Five hundred local people had helped Janssen lug his heavy equipment up the hill; and to commemorate his successful photographic plates, he later installed a small stone pyramid near the peak.

Figure 5.2 Nagasaki Harbour from Tateyama, after 1896.

I wonder if Hashimoto Usa celebrated the new year of 1897 by praying at Nishiyama shrine, or whether she ascended Tateyama or Mount Konpira one last time before departing Nagasaki in June of that year. There is no way of knowing – but it nonplusses me that a perfunctory internet search reveals more about one of Nishiyama’s nineteenth-century cherry trees than it will about one of its nineteenth-century residents, that it is easier to research the history of a planet crossing the sun than a woman crossing to Singapore.

Seeing My Sister at Singapore

My elder sister is keeping a lodging house in Singapore at Malabar Street –

I am one of the inmates of No 2 at the place known as Yokohama Thursday Island, a brothel kept by Shiosaki –

I departed from Nagasaki with the intention of seeing my sister at Singapore –

Like a navigator, the historian can map the locations mentioned by Hashimoto Usa in the opening sentences of her statement, and their order: Nagasaki, Singapore, the Japanese settlement of ‘Yokohama’ on Thursday Island, back to Nagasaki, once again to Singapore. Her mind seems to jump without settling: having noted her place of birth, should she continue with her journey’s intended destination or its unintended endpoint? The ebb and flow of her narrative may suggest emotional turmoil, caused both by her physical ordeal and also by finding herself, on this 29th day of November, suddenly ‘in the presence of Torajiro Satow and Gyusaku Sugiyama’ and the British official for whom they were translating. From Singapore to Thursday Island and back to Singapore may equally be a narrative consequence of the three men trying to lead the interview to the present situation and Usa resisting – to insist first on her ‘intention’. Either way, the most important detail in these opening gambits is the address of her sister’s lodging house in Singapore. For with her mention of ‘Malabar Street’, corroborated in Oyaya’s own petition to the Thursday Island authorities, Usa takes us from the still air of Tateyama into the brawling, bruising heart of a magnetic Asian cityscape.

Singapore’s global importance by the 1890s had been many decades in the making, its roots predating the port’s founding by Sir Stamford Raffles in 1819. In the second half of the seventeenth century, increasing numbers of Chinese seafarers, including those defeated by the new Qing dynasty (1644–1912), had established themselves in the coastal waters of Southeast Asia, where they traded in commodities which both Chinese and European consumers demanded. The latter’s taste for tea, for example, stimulated the need for the tin, timber, rattan and lead used in packaging. Increasing numbers of Chinese labourers migrated into the region to work in commodity production also for the Qing market – in gold- or tin-mining, in pepper-planting colonies or in the transport of rice from the Mekong Delta. But as previously prosperous trading entrepôts in Hà Tiên (present-day Vietnam) or Riau (Indonesia) declined by the late 1700s, the new Straits Settlements established by the British in Penang (1786) and Singapore expanded, thus also attracting – to the alarm of Singapore’s colonial administrators in the 1830s – large numbers of Indian and especially Chinese immigrant labourers.Footnote 26

Quickly, these labourers themselves became a commodity. As such, their transshipment in and export on from Singapore was stimulated by the growing European demand for Southeast Asian raw materials whose production required an expanding workforce, one supplied by the overpopulated hinterlands of Guangdong and Fujian. In the early years of this so-called ‘coolie’ trade, the labourers were transported to the straits in flat-bottomed junks which in turn carried inanimate commodities back to China. By the last two decades of the nineteenth century, between 50,000 and 200,000 ‘coolie’ labourers arrived annually in Singapore – their mobility now facilitated by the emergence of regular steamship lines to and from China (the routes partly a consequence also of the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869). ‘Singapore was a coolie town’, writes Carl A. Trocki, who estimates that approximately five million people, mainly men, passed through the settlement between the mid 1880s and the beginning of the First World War.Footnote 27

Such high numbers of male immigrants and transmigrants in the impoverished outskirts of the burgeoning city created an environment rife for exploitation, abuse and prostitution. Consequently, in an attempt to regulate prostitution, contain venereal disease and not least control the activities of the Chinese ‘secret’ societies, British colonial authorities established the Office of the Chinese Protectorate in 1877.Footnote 28 By this year (according to official data), there were already two Japanese brothels on Malay Street, in the centre of what would become the city’s eastern entertainment district; but by 1905, there were 109 registered Japanese brothels out of a citywide 353, serving clients from across the social and racial spectrum.Footnote 29 In November 1897, as Oyaya dictated her petition, colonial authorities identified over 3,000 prostitutes in Singapore, about a quarter of whom were Japanese (although both figures were almost certainly underestimates).Footnote 30 But because regulation of prostitution fell under the domain of the Office of the Chinese Protectorate, Japanese consular officials had no direct power over these women; and when the women needed help, they therefore turned to the British authorities.Footnote 31 This is why Oyaya enlisted the aid of one Y. Ukita, ‘Japanese Interpreter and Clark [sic], Chinese Protectorate’, in order to compose her letter on 8 November. ‘Your Petitioner,’ she begins, having presumably walked or taken a rickshaw across to Ukita’s office in the western side of the city, ‘is living at 29 Malabar Street Singapore and is the keeper of a Japanese licensed lodging house.’Footnote 32

There’s not much to go on if you want to recover this history today. In contrast to the lavishly constructed displays of opium dens or rickshaw-filled streets, the topic of prostitution in the Singapore History Gallery of the National Museum, on Stamford Road, is conspicuous by its absence.Footnote 33 The north–south-running Malay Street and the cross-thoroughfares of Malabar Street and Hylam Street survive only as indoor walkways in the Bugis Junction shopping mall, the quarter’s history now as sanitized as it once was seedy. Amidst the designer shops and ‘street’ market stores, with the Intercontinental Hotel looming through the Junction’s convex glass roof, there’s nothing to recall the 116 brothels on these three streets alone, 85 of them run by Japanese keepers such as Oyaya.Footnote 34 Sushi eateries, Belgian chocolatiers and the ubiquitous Starbucks there may well be, but long gone are the days of nominal cake-maker Matsushita Riosaku, who rented the upstairs floor of 36 Malabar Street to ‘women who keep brothels’ at the turn of the twentieth century; or the coffee house and lodging run by Oda at 32 Malabar Street in 1902; or, in the same year, ‘the Japanese hotel called Matsuo Ryokan in Malabar Street’, as noted by the newly arrived Dr Nishimura Takeshiro; or the brothel at 4 Malabar Street where one of Cheng Seng Choy’s regular clients, a 35-year-old Teochew fruit hawker, died of natural causes early on the morning of 25 October 1897.Footnote 35

These histories are to be found in the extraordinary scholarship of James Francis Warren, work based in turn on the records of the Singapore Coroner’s Inquests and Enquiries between 1882 and 1939. Thirty years on from Warren’s archival research, I spent a couple of days in January 2019 looking through the microfilms of these coroner’s courts and was overwhelmed both by the volume of cases and by the general illegibility of the scribes’ handwriting. It would be a miracle to find mention of Oyaya here, the more so because hardly any of the Japanese women who appeared in the records were identified by surname (and it’s not certain that Oyaya took the name ‘Hashimoto’ in 1897). And then there’s the fact that the best surviving evidence of Malabar Street life in the late nineteenth century comes in the form of coroner records which, by their very definition, are created to record death and its associated detritus. If Oyaya really was the keeper of a licensed lodging house in Singapore, then she likely possessed the skills to run a ‘good brothel’ in circa 1900, namely (according to Warren) ‘courage, shrewd judgement of character, physical stamina on an around-the-clock basis, a decent knowledge of first aid, do-it-yourself gynaecology, and skill in self-defence’.Footnote 36 If she did this well and had some luck, she would never appear in the reports of the coroner’s inquests and enquiries – her absence just as much a marker of her success as the fact that she had the gumption to employ an interpreter, dictate a petition concerning her ‘kidnapped’ sister and thereby initiate a paper trail which extended to the far reaches of the British empire in northern Queensland.

As I scroll and squint at the Singapore microfilms, a case from February 1896 catches my eye. It concerns the death of Osai, an employee of the Japanese brothel at 25 Malay Street, where, due to her relatively advanced age of 45, she probably worked as a servant. Her ‘mistress’, Osada, testified that Osai had complained of stomach ache on the morning of 9 February. ‘I took her to the German dispensary at 11am and the dispenser […] gave her a bottle of medicine.’ A little over twelve hours later, she was dead – of a strangulated diaphragmatic hernia.Footnote 37

Here was a case striking in its ordinariness – at least as much as brothel life on what the Japanese called the suturetsu (streets) could be ordinary. Due to her age, we must presume that Osai first came to Singapore as a much younger woman during the earliest years of Japanese expansion into the city. Perhaps she was kidnapped or perhaps she came of her own intention. Either way, she had neither returned home nor risen to become a ‘keeper’ like Oyaya or Osada. If she’d had her hernia for some time, then perhaps ill health and the associated expenses of medicine and doctors’ fees trapped her in poverty – Osada noted that Osai had been hospitalized for twenty days some two years previously. Both women may also have been overcharged for Osai’s treatment: the inquest revealed that the chemist, identified by Osada as German, was in fact no doctor, despite ‘eleven of my girls get[ting] certificates of “freedom from venereal disease” from him every week’. Apparently surprised by this revelation, Osada insisted, ‘I thought he was a “Doctor”’, before adding, ‘I do not know how many of the other keepers think the same’. Meanwhile, Eskato, a ‘pedler [sic] living in 12 Malabar St.’, noted that he knew the deceased and that ‘many of the Japanese employees’ considered the German pharmacist to be a doctor.Footnote 38 If Eskato observed Osai going about her daily work, then most probably he would also have known his Malabar Street neighbour, Oyaya.

A day or two later, prompted by a book in the Singapore National Library, I catch a bus nine kilometres north to the Japanese Cemetery Park.Footnote 39 Now in the city’s quiet residential suburbs, the cemetery occupies rubber plantation land owned by three Japanese businessmen prior to 1891. Like hundreds of other destitute women who died in Singapore from the 1890s to the 1920s, Osai is buried here, her light-grey headstone tilting like a mini Tower of Pisa, her plot delineated by a rectangle of lichen-stained masonry in the grass. The fading inscription records her date of death, her home village – on the Amakusa Islands, in Kumamoto prefecture – and her name (in Japanese): ‘Sai, daughter of Shimo Kiyotarō’.

At the last, then, she has a surname: Shimo. And, far too late given my training in Japanese history, I also realize that her given name was not Osai but Sai. The same was true of her mistress, Sada, and any of the other dozens of women mentioned in the coroner’s enquiries – the sex labourer Oseki and her keeper Ohaye at 52 Malabar Street, or Oichi and her keeper Ofuku at 55 Malabar Street, in 1905 and 1906 respectively:Footnote 40 ‘O-’ was an honorific prefix used for women throughout the Edo and Meiji periods, and well into the twentieth century. All of which means that the author of the November 1897 petition – Usa Hashimoto’s nominal ‘sister’ – was a woman probably called Yaya, not Oyaya.

Shimo Sai’s resting place is a beautiful site, purple bougainvilleas canopying over the cemetery’s main walkway. As I take photos of her headstone, I stoop down to read the inscriptions on neighbouring plots. And here I find the grave of an unnamed woman who died on 21 April 1892. Her address is listed as Tenjin-machi in Kaminoseki town, Yamaguchi prefecture – a district I walked through every day on my way to the Municipal Archives in 2007 and 2008 (Chapter 3).Footnote 41

On the Representations of a Man Named Konishi

This I did on the representations of a man named Konishi at the end of June 1897 –

There were ten other young women who left by a sailing ship at the same time accompanied by Konishi –

I do not know the name of the ship –

We had no passports –

It was midnight –

I intended to go to my sister at Singapore –

The women who emigrated to such entrepôts as Singapore from the last decades of the nineteenth century until the end of the Second World War are popularly known in Japan as Karayuki 唐行 (or, honorifically, Karayuki-san). The term derives from north-west Kyushu and literally means ‘going to China’, although in its very earliest uses, after 1868, it simply referred to women and men who sought work overseas. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, it had come to be applied only to Kyushu women who worked in the sex industry throughout the Asia-Pacific region; and, in later iterations, Karayuki-san connoted women especially from the Amakusa Islands – the birthplace of Shimo Sai – who worked in Southeast Asia.Footnote 42 According to David Sissons, a ‘plaintive song’ was sung about the Karayuki-san at the turn of the twentieth century:

Carried on the drifting current,

Her destination will be

In the west, Siberia;

Which country will be her grave?Footnote 43

The geography of the lyrics is unusual: from Japan, Java would be in the west. Perhaps, then, the song originates from Karayuki-san communities in North America, where ‘Java’ would conjure up an image of the Orient. But be that as it may, the language – as with the Hawaiian holehole bushi plantation songs (Chapter 3) – is of drifting bodies and currents, as if the Karayuki-san had no agency in their decision to leave Japan.

Certainly, substantial numbers of women were indeed carried on drifting currents in the late nineteenth century, against their will and with no idea of their destinations. In September 1897, for example, the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser published an article, ‘The Abduction of Girls from Japan’, itself a reprint from the English-language Kobe Herald (in turn citing Kobe’s Japanese-language Yūshin nippō). The article reported on a recently returned but unnamed eighteen-year-old girl who, after the death of her father, had moved from Shikoku to work in a fan factory in Osaka. One night, she and a friend were ‘accosted’ by a woman offering them work in a Yokohama teahouse. Deciding to accept, the girls were taken to Kobe for several days, and then at 2am on 12 November (1896) stowed away on board the NYK steamship Miike-maru in the company of four men and eleven other women. Travelling in darkness and ordered by the men to remain quiet, the women arrived ten days later in what they expected to be Yokohama but was in fact Hong Kong. There, ‘quartered in a hotel’, one of the girls attempted to escape but was caught; another girl was advised by a young Japanese man that it was useless for her to go to the police unless she could speak English. Another ten days later, nine of the women were shipped to Australia, while the eighteen-year-old was taken to Singapore and then on to a Japanese brothel in Batavia. Becoming ill and needing hospital treatment, her case was attended to by the Japanese consul in Singapore, who eventually arranged for her return to Kobe. The girl reportedly stated ‘that there are many brothels kept by Japanese in Sumatra, all the girls being surreptitiously brought from Japan’.Footnote 44

There survive enough such reports, both in published media and in various archives, for historians to be sure that the practice of Japanese women being abducted and surreptitiously sent overseas was widespread at the turn of the twentieth century. Exactly how widespread is open to question: as David Ambaras has noted for a slightly later period, newspaper reports of ‘abduction’ constituted their own written genre, one often framed by the sensationalist agendas of reporters or editors.Footnote 45 Even a small number of factually accurate cases would be historiographically significant, however. This is because the conditions in which Japanese women and even young girls were ‘recruited’ to work in Southeast Asia (or, later, mainland China) have been made central to a debate about the later Japanese exploitation of so-called comfort women from imperial colonies in the 1930s and 1940s. If it could be proved (the argument goes) that there were no coercion in the period from the 1880s to the 1920s, then (by a deductive sleight of hand) it must also be true that there was no coercion of the later ‘comfort women’. As many reputable scholars have pointed out, using evidence from one place and period to explain another is a deeply problematic methodology – as is the conscious misuse of later oral histories recorded by Japanese women who were, in exceptional cases, only ten years old when recruited for overseas sex labour.Footnote 46 All of which makes discussion of cases such as Hashimoto Usa’s particularly fraught.

But if we follow Hashimoto’s own testimony, then her departure from Japan does not appear coerced – as, indeed, Brisbane officials seem to have concluded in labelling the case as an ‘alleged abduction’ (see Figure 5.1). She states on two occasions that it was her ‘intention’ to go to Singapore. Without knowing her original Japanese phrasing, it’s difficult to parse the nuances of this term. But a few key elements of her statement are consistent with those of other women who left Nagasaki to go overseas in the summer of 1897. In the archives of the Japanese Foreign Ministry in Tokyo, for example, I find first-person testimonies from five women recruited to work in Vladivostok – that is, in the ‘Siberia’ of the Karayuki-san song. The narrative structure of their accounts echoes that of Hashimoto’s in three basic ways.Footnote 47

First, the recruiter was a key protagonist. Rather than an unknown accoster, he was someone the women had partly come to know. In this case, there were two such men: Maekawa Saihachi (aged 39) and Shimosaka Toyokichi (37), respectively a farmer–fisherman and a cooper. Maekawa, who in 1896 had worked as a captain transporting stowaway women to Vladivostok in a Japanese-style sailing vessel, now wanted to lead his own operation. To that end, in addition to renting a boat for 300 yen, he recruited one woman, the twenty-two-year-old Fukuhara Tsuru. Originally from Fukuoka prefecture, Fukuhara had been working in a relative’s Western-style grocery shop in Nagasaki’s Chinatown for all of two weeks when Maekawa, who was a frequent customer, started telling her of a ‘good place’ (yokitokoro 好き処) where she could make money. Shimosaka, for his part, appears to have groomed the other women over a number of days from occasional chance encounters: he ‘met’ Matsunobe Tomi (23) a few days after she had arrived, also from Fukuoka, to learn needlework from her aunt; he came to the house where Onoue Shima (25) was staying while seeking domestic service employment and posed the rhetorical question of whether this were really the kind of household from which she would eventually be able to marry; he often bought eggs at the shop where Nakamura Saku (18) was working, such that she knew his face when she bumped into him on the street one day; and, in the case of Maebara Matsu (23), he was even joined by her employer, an acquaintance, who urged her to go abroad. Thus, for Hashimoto Usa, the ‘man named Konishi’ may have played a similar role as had Shimosaka for these Vladivostok-bound women – as someone she felt she could trust to accompany her to Singapore.

Second, this familiar figure promised to manage the logistics. Matsunobe Tomi recalled that Shimosaka had told her he would take care of passports and everything else. Nakamuru Saku, the youngest of the Vladivostok-bound group, testified:

I said, ‘If we don’t have a licence [passport] to go abroad, then we can’t go, right?’ To which he said, ‘There’s no need to worry at all: I’ll take care of it all’.

There may be an element of Nakamura speaking to her audience here. Her testimony, like that of the other women and the two recruiters, was taken down by a member of staff from the Japanese consulate in Wonsan, Korea, where, en route to Vladivostok, Maekawa’s rented boat had landed (‘having fallen into great difficulties’). Perhaps, to these particular officials, she wanted to emphasize her lack of culpability when it came to the paperwork of international travel. But still, the journey involved ‘no passports’ – as was also the case for Hashimoto Usa.

And third, several of the Vladivostok-bound women were also explicit in voicing their desire to go abroad:

I also knew that [a ‘good place’] would most probably be a foreign brothel, but he recommended it to me in various ways, saying that I could make lots of money and advance in the world, so I ended up wanting to go. [Fukuhara Tsuru]

I thought that if I went to Vladivostok I would do service at some kind of brothel; but because [Shimosaka] said I would get lots of money and could advance in the world, I finally ended up wanting to go. [Nakamura Saku]

Although I thought that if I went to Vladivostok I would do service in a brothel, [Shimosaka] said I would earn lots of money, so I finally ended up wanting to go. [Matsunobe Tomi]

Perhaps this was the phrase Hashimoto Usa used as well, iku ki ni naru 行く気になる, which her Thursday Island translators then rendered as ‘I intended to go’.Footnote 48

Of course, the linguistic evidence from the Vladivostock case is not as unambiguous as it might seem. The almost identical phrasing used by the three women in their recorded dispositions raises the suspicion that they were coached by their handlers to give set responses in the event that they be apprehended. This was certainly true of some Chinese and Japanese women who ended up in Singapore;Footnote 49 and the fact that the Vladivostok-bound women denied knowing the name of the fishing port from which they were smuggled away in the cover of darkness suggests that they were trying – or had been told – to protect the ringleader Maekawa, whose home village (Fukuda) it was. That, at least, is one hypothesis to explain their rote-phrasing. An alternative is that the male consular official in Wonsan not only transcribed but also edited the women’s nominal first-person voices into a series of set phrases in order to simplify his job. More perniciously, he may have done so also to imply that the problem was less groomed coercion than immoral women willing to do anything for money. Here, as often in the case of nominal first-person testimonies ‘glossed by a male hand’, the legibility and brevity of the account served both to simplify complex motivations on the part of the women and to encode gendered assumptions on the part of the men.Footnote 50

But even if the evidence of ‘intention’ is ambiguous in the Vladivostok case, the bigger picture was that there were significant numbers of women willing to earn money overseas in the late nineteenth century. This may have been to ‘advance in the world’ (shusse 出世), and/or to send remittances (sōkin 送金) home – either to their parents and older brothers, or to their village as a whole (as Matsunobe Tomi and Maebara Matsu respectively claimed in their testimonies). In this sense, the women’s motivations for leaving Japan were no different from those of a male migrant such as Fuyuki Sakazō (Chapter 3), who went off to make money in Hawai‘i – or from Fuyuki’s cousin Hiraki Yasushirō, whom Fuyuki helped find sugar plantation work in 1897. Indeed, five years earlier, the Acting Japanese Consul in Singapore had written in English to the city’s Chinese protectorate concerning four ‘girls’ – aged seventeen to eighteen – whom British officials had wanted investigated. Noting that they were all ‘natives of Nagasaki’, the consul explained their economic circumstances at home:

They informed me of their families’ being in such distress that they could not even provide themselves, sometimes with daily food. They arrived in Hong Kong in the beginning of last summer for the purposes of finding some means of living there. They came on to Singapore [as] they had heard about this place being very prosperous.

Having talked to the women, he was sure that they had not ‘been induced to leave or smuggled out by any one’, and that they had left Japan ‘entirely of their free will’. He continued:

Under these circumstances I am convinced that these girls were not brought out by others against their will, but that they really came here by their own wishes, in order to procure a better living in this place, than they could do in their native country.

The consul’s language is more discreet than that of the transcribed Vladivostok women – he writes of ‘a better living’ where they spoke of ‘lots of money’ and worldly ‘advance’ – but the general point is the same: many of the women leaving Nagasaki in the late nineteenth century were doing so for economic reasons.Footnote 51

Yet the pre-war archival eye in Tokyo could not acknowledge the parity of this economic push factor between male and female emigrants. The main body of pre-war diplomatic records in the Japanese Foreign Ministry archive is divided into more than twenty series (mon), of which the most important for the study of overseas migration in the Meiji period would seem to be Series 3 (Commercial Relations). The majority of files relating to the government-sponsored emigration programme to Hawai‘i, for example, are to be found in various sub-series thereof, as in: 3 (Commercial Relations) – 8 (The Movement of Imperial Subjects) – 2 (Migrants). Yet the Vladivostok-bound women are not filed alongside Fuyuki or his migrant counterparts in 3-8-2 but rather appear in 3-8-8 (Miscellaneous), as if metropolitan bureaucrats did not know how to categorize single women wanting to go abroad. In fact, women only appear in the government-sponsored Hawaiian paperwork if they are listed as the wives of male emigrants – even if the status of pre-departure and post-arrival ‘wife’ was considerably more fluid than Japanese officials knew or wanted to believe.Footnote 52 Meanwhile, the four Nagasaki girls questioned in Singapore in 1892, whom the acting consul insisted came simply ‘to procure a better living’, are filed under 4 (Judiciary and Policing) – 2 (Policing) – 2 (Policing Matters, Enforcement and Punishment). Here, the archival eye is unambiguous: the women constituted a problem of law and order.

This apparently technical issue of filing is a classic expression of the metropolitan archive’s ‘ocular regime’, whereby migrating single women were classified as a threat to the Meiji state – and thus in need of repatriation – in ways that single men were not.Footnote 53 The building-blocks of such a classification were the consular reports flowing into Tokyo from Southeast Asia, Australia and North America. In June 1888, for example, the honorary Japanese consul in Melbourne, Alexander Marks, wrote to Tokyo to report on information he had requested from the businessman Kanematsu Fusajirō, who had recently returned to Japan via Port Darwin.Footnote 54 Kanematsu, wrote Marks, ‘says there are 15 men and 21 women [there] who are all prostitutes and the men may all live [?] on the prostitution of the women’. Calling the whole affair ‘extremely unpleasant’, he did ‘not wish the fair name of Japan soiled by a lot of unfortunate women’.Footnote 55 Almost a decade later, in June 1897, it was the same story: Marks wrote of receiving a letter from a Japanese resident of West Australia ‘complaining about the number of Japanese low characters both men and women now in that country’.Footnote 56 Many of these came from Singapore, Marks added.

In these cases, Australia-bound women who desired a better living even through the practice of sex work were framed in three ways. First, their circumstances rendered them ‘unfortunate’ – a language I never saw deployed by officials for Japanese males who had had to leave Japan for similar reasons of domestic impoverishment. Second, their presence undermined both the expansion of Japanese business interests overseas, as embodied by Kanematsu, and also ‘hindered’ those male Japanese who sought ‘respectable Honest Employment’ (in the words of Marks’s 1897 informant).Footnote 57 Thus, thirdly, the women soiled the ‘fair name of Japan’.Footnote 58 Describing them in 1888 as ‘most indecently dressed and in their houses with little or no clothing on at all’, Marks hoped that the presence of Japanese women would not provoke the colonies to impose immigration restrictions on all Japanese subjects – including on the allegedly more reputable men.

The image of working women that Marks and other Japanese consuls reported back to Tokyo in the 1880s and 1890s was an ugly one – even if, as we have seen, such reports were often exaggerated. (‘These women,’ the Cairns sub-inspector of police wrote in November 1897, ‘although a nuisance by reason of their calling are so orderly in their conduct that a stranger coming to town would have to seek them before he would find them, that is they are not prominent to public view’.)Footnote 59 Such negative images are important because, whereas overseas male labourers were uniformly referred to as dekasegi-nin 出稼人 (literally, ‘people migrating away to work’), one of the technical terms for overseas women which Japanese officialdom came to use from the 1880s onwards was shūgyōfu 醜業婦, or ‘women engaged in unsightly work’ – where the first character, shū, can also be read minikui, namely ‘ugly’, ‘base’ or ‘unseemly’. Another common label was mikkōfu 密航婦, or ‘women who stowaway’ (literally, ‘women in secret passage’).Footnote 60 Thus, in the Vladivostok-bound case from 1897, the paperwork was summarized with the combinatory rubric, ‘Concerning unsightly stowaway women’, but elsewhere the objects of investigation were called ‘stowaways engaged in unsightly work’.Footnote 61

As Bill Mihalopoulos has shown, such terminology was effectively produced in the discursive space between consular officials across the Asia-Pacific world and their employers at the Foreign Ministry in Tokyo. The category of ‘unsightly’, he argues, ‘was conceptually oblivious to the vulnerability of the rural poor and to the fragmentary and unstable forms of paid work that led them to seek work abroad’.Footnote 62 But we can go further: shūgyōfu defined women by the work they engaged in upon arrival in a new port, while mikkōfu defined them by the nature of their shipboard transit. In other words, the ‘stowaway’ category discursively trapped migrating women on the ships that had transported them, thereby inviting historians to read the archive according to their passage and arrival rather than according to their pre-departure intentions.Footnote 63

Returning to Hashimoto Usa, the problem is that her stated intention was only to ‘see’ her sister. Yaya herself testified to a planned ‘visit’. Although Usa acknowledges working in a Thursday Island ‘brothel’ (jorōya 女郎屋, if she used the same terminology as the Vladivostok-bound women), she never uses the word ‘prostitute’, as if refusing to be framed by a male imagination of her engaging in ‘unsightly work’.Footnote 64 Instead of mentioning her desire to make money or ‘advance’, she focuses on the culpability of the male agent, Konishi, on whose ‘representations’ she departed Nagasaki. The tension here between Hashimoto’s intention to travel and yet the blame she attributes to Konishi is also consistent with the most detailed of the Vladivostok statements. Maebara Matsu notes that she was ‘recommended’ to go overseas (susumerare 勧められ: did Hashimoto say something similar, which was rendered into ‘representations’ by her translators?); almost immediately, however, Maebara regretted her decision. Thus, intention and regret might not have been mutually exclusive for women like Hashimoto. It’s also the case that in these sentences more than anywhere else in her testimony, I hear a tussle between her and her questioners over who will control the story’s narrative. We may imagine them asking, ‘What was the name of the ship?’

I do not know the name of the ship –

Who kept your passports?

We had no passports –

What was the time when you boarded?

It was midnight –

Where did the ship go?

To which Usa does not immediately answer. First, she insists once again that she ‘intended to go to my sister at Singapore’, as if through repetition she may convince her audience. Only then will she return to her questioners’ agenda: The ship took us to Shanghai –

Does Usa in fact convince her audience of her intentions – at least her twenty-first-century interlocutors? I’m not sure. Or rather, I wish historians had archival access to the most important paperwork in the story, as revealed by Yaya:

Your Petitioner has now received a letter from her sister which says that she is at present in a Japanese house named Matsubara a brothel and that she is forced to prostitute herself against her will.

Given that both Usa and Yaya were unable to write, the logistics of Usa sending correspondence from Thursday Island to Singapore were considerable. Why was Usa updating her sister as opposed to the only other family relation mentioned in Yaya’s petition, ‘her brother in Japan’ – where, Mr Ukita’s translation abilities notwithstanding, our would surely be the more natural personal pronoun? If there had been a similar sisterly exchange of letters between Malabar Street and Nishiyama in the early months of 1897, was Konishi involved in some way as a broker working on Yaya’s behalf? If so, then is it possible that the term ‘sister’ referred – as so often among the Karayuki-san in Singapore – not to a biological relationship but to the hierarchical relationship between a keeper and her prospective employee?Footnote 65 And that Usa intended, through Konishi’s representations, to work in a lodging house at Malabar Street?

And thus: is it possible that Yaya’s appeal to the British authorities in Queensland via Singapore was motivated less by sisterhood than by a recruitment process gone wrong, an asset kidnapped by competitors?

Transferred without Landing

On reflection, I don’t much like the tone of my questions. My voice has bled into that of Hashimoto Usa’s investigators on Thursday Island. Which is unfortunate because, regardless of her pre-departure plans or the exact nature of her relationship to Yaya in Singapore, the next part of her statement, beginning with her and ten other women leaving Nagasaki on a sailing ship, reveals a system in which her intentions counted for nothing. Indeed, we need not define Hashimoto by her passage nevertheless to accept that her period of transit, from Nagasaki through Hong Kong to her eventual arrival on Thursday Island, was a formative moment in her story.Footnote 66

The ship took us to Shanghai, and there we were transferred without landing to a Steamer for Hong Kong where we arrived on the 13th of July –

We were all put up at a lodging house kept by a Japanese called Yoishi Otaka –

I was then told that it would be impossible for me to go to my sister in Singapore as no woman who has not a passport from the Japanese authorities is allowed to land at Singapore –

The visit to my sister at Singapore was my inducement to leave Japan –

My disappointment was so great that I did not know what to do –

In these sentences, Hashimoto offers a series of realizations which must have washed over her like waves of seasickness during her weeks in transit: that Konishi was not the man she had imagined him to be; that a new regime of passports initiated by the Meiji state constrained her movements in ways that sisterly correspondence between Malabar Street and Nishiyama had surely not explained (assuming such correspondence existed);Footnote 67 and, most importantly, that she had become a sellable commodity in a transnational infrastructure which, by 1897, had been years in the making.

The key nodes in this infrastructure were all referenced in Hashimoto’s account, namely the port cities of Nagasaki (described by Consul Alexander Marks in 1888 as the ‘hunting ground’ for ‘unprincipled traffickers’), Shanghai, Hong Kong and Singapore (the last two constituting ‘great sinks of iniquity’).Footnote 68 Two weeks prior to Hashimoto’s departure, for example, a group of two Japanese men and eight women – the latter aged between seventeen and thirty-six – had boarded a German steamer in Nagasaki bound for Shanghai, where they arrived four days later. Without landing, they had attempted to transfer to another steamship bound for Hong Kong but were detected and taken to the Japanese consulate. Along the way, the two male ringleaders escaped, but the women were promptly returned to Nagasaki. Consular officials recorded their addresses, which included both Nagasaki city and also the Shimabara peninsula, another south-western Kyushu region which was particularly associated in the post-war Japanese popular imagination with the Karayuki-san. Two of the eight women, it turned out, were sisters who had already been repatriated from Shanghai the previous October; another, the thirty-six-year-old Ishimoto Tayo, had been working in Hong Kong for nine years but had returned home temporarily to visit her sick mother.Footnote 69 (Again, these histories force us to query Marks’s language of ‘hunting’, with its implication that all women departing Nagasaki were captured against their will.)

This and numerous other cases reveal that the infrastructure of female trafficking was connected partly to the steamship economy – as also in the aforementioned 1896 case of the eighteen-year-old girl and her friend who stowed away on the NYK-owned Miike-maru with the expectation that they would disembark in Yokohama, not Hong Kong. More specifically, the trafficking networks were associated with Kyushu’s most important export item in the late nineteenth century, coal. As part of an ongoing policy to expand its foreign trade, the Meiji government opened nine ‘special ports of export’ in 1889, including four in Kyushu – Kuchinotsu, Karatsu, Moji and Misumi – which specialized in coal.Footnote 70 But this also had unintended consequences, as noted by the Japanese consul in Hong Kong in 1890: ‘The increase in the flow of foreign ships entering and leaving recently opened special export ports such as Kuchinotsu and Karatsu for the purposes of exporting coal, has also increased the opportunity [for women] to slip secretly abroad.’Footnote 71

Coal could of course be carried on steamships, but the most important mode of transport was sailing ships. The 715-ton Sumanoura-maru, with which the Yamashiro-maru collided in October 1884, was one such vessel: bound for Nagasaki carrying only ballast and forty boxes of dynamite (presumably for Mitsubishi-owned mines), its main function was to transport coal from Kyushu back to Yokohama.Footnote 72 Similarly, sailing ships traversing the East China Sea were central to Meiji Japan meeting the exponential increase in demand for Japanese coal in late nineteenth-century Shanghai (see Chapter 6). We must assume that Konishi had arranged for Hashimoto and her ten female companions to travel on one such ship in late June 1897 before transferring ‘without landing onto a steamer for Hong Kong’.

Between them, Hashimoto Usa and her questioners are curiously reticent about this hybrid sail–steam passage from Nagasaki to Hong Kong. Where elsewhere in her statement there are hints of Usa being interrupted, here there are none. And if she chose not to go into the details, that may be because the realities of being a stowaway were too traumatic to dwell upon. Several decades later, retired captain Katō Hisakatsu, who had begun his career on an 850-ton coal-carrying ship sailing from Yokohama to Karatsu and later worked all around maritime Asia, recalled the ‘ingenuity’ (kōmyōsa 巧妙さ) with which ringleaders such as Konishi concealed their human cargo ‘in places unfit to accommodate humans’. Katō also noted how easily things could go wrong:

[The women] might be crowded into the ship’s water tank when the engineer, not knowing they were there, would fill the tank mid-passage and they would be submerged alive, ending up as swollen blue corpses. Or there would be women poisoned by coal gas [carbon monoxide], who would die writhing and screaming and vomiting blood. Or there would be ghost-like women, hair dishevelled and nothing more than bones, starving for food and parched for water, who would eat lumps of coal until they breathed their last. Or there was once a male procurer who was surrounded as the women became ravenous. They gnawed on him as a rat nibbles rice-cakes – women who hated his cold-heartedness and tortured him to death, eating at him while baring their bloody teeth, gouging his eyes out and ripping off his nose.Footnote 73

In this passage, there is a sense that Katō offers graphic details with a little too much relish. ‘Such horrific stories to make your hair stand on end,’ he continues, slipping almost into a genre of sailor’s yarns: ‘No matter how many I write, I would not run out of them.’

But lest Katō be thought to be exaggerating, the international press had reported in 1890 on the NYK-owned steam coal-hauler Fushiki-maru, which left Nagasaki on 21 March. After a few days, a ‘bad smell’ was noticed in the engineers’ mess room, at first attributed to dead rats. But following arrival in Hong Kong on 26 March, the stench was traced to the cofferdam, a compartment some three feet high and two feet wide (91 cm by 61 cm), stretching across the width of the ship above one of the water tanks. Having removed coal from the main hold to get to the compartment’s sliding door, the crew discovered the naked corpses of seven women and a man, all ‘in a more or less advanced state of decomposition’, and four other naked women alive but in a ‘shocking condition’. The survivors described having been lured to Hong Kong by the deceased man, a cooking-oil salesman, who had gone house-to-house selling promises of a better life in Hong Kong. The women had made it on board dressed as coal ‘coolies’, but after entering the cofferdam their exit had been blocked by coal loaded into the hold. To secure relief from the intense heat of the compartment’s iron plates, the survivors reported having lain across the bodies of the dead.Footnote 74

That Hashimoto Usa and her ten female companions did not meet such a fate does not detract from the terror that they presumably felt in the depths of the ship, cooped up in the stultifying darkness of the coal bunkers with the air – at least from Shanghai to Hong Kong – pounding to the engine’s rhythm. If a summer typhoon were to come, with waves ‘running mountains high’, the hold’s coal might shift and even combust – as happened with the Cheang Hye Teng (1,436 tons), steaming with a cargo of coal from Moji to Hong Kong in August 1897; the ship eventually sank with the loss of thirty-six lives.Footnote 75 On top of all this, depending on which of the ship’s male crew knew that there were stowaways on board – and there were always some bribed members of the traffickers’ networks – the women also faced the prospect of rape day and night in the pitch black of the bunkers.Footnote 76 For foreign crew members in particular, according to Katō, the women were ‘an offering to be pinned down while they sated their lust’.

This was an ‘unimaginable world’.Footnote 77

Otaka the Keeper of the Lodging House

Konishi the man who brought me from Japan went back to Japan –

Perhaps he had received a considerable sum of money from Otaka –

I found myself alone in a strange country without a friend to help me –

While I was in such distressed and terrified condition Otaka the keeper of the lodging house told me that Thursday Island in Australia was a very good place to make money, and that I could freely land there without passports –

He strongly advised me to go to Thursday Island –

I followed his advice thinking that in doing so I might find an opportunity to get afterwards to my sister at Singapore –

Although Hashimoto Usa does not name any of the women with whom she travelled or was sequestered, nor indeed her sister by name, she is explicit about four men: Konishi and Matsubara, who accompanied her from Nagasaki to Hong Kong and from Hong Kong to Thursday Island respectively; her brothel keeper on Thursday Island, Shiosaki; and, in Hong Kong, ‘a Japanese called Yoishi Otaka’ – from whom, she suspects, Konishi ‘had received a considerable sum of money’.

These men were the ‘procurers’ (zegen 女衒), or, to use a term I saw more often in the particular sources I used, the ‘ringleaders’ (shubōsha 首謀者). Hundreds of them are named in the Japanese Foreign Ministry’s archives – sometimes by consular officials and sometimes by concerned Japanese visitors or residents.Footnote 78 Back in April 1889, Alexander Marks received a letter from a Hokkaido government official who, on his way to Melbourne, had passed through Port Darwin (whence the businessman Kanematsu had reported the previous year). The official detailed a conversation he had had with two Japanese ship carpenters living there, who testified:

That another Japanese named Takada Tokujiro of Osaka came to that town with five young women all of whom belong to Nagasaki but had been residing in Hon Kong [sic] just previous to their removal to Port Darwin, and that he gave one of them to a Malaya hair dresser for £50, and two to a Chinese at £40 each, keeping one for his concubine and the other under his employment as a public woman.

The two carpenters, the letter continued, had tried to take Takada to a local court but were unable to do so before he had ‘run away’ to Singapore ‘owing to their inferiority in the English speaking capacity’.Footnote 79

Nagasaki – Hong Kong – Australia – Singapore: once again, the key nodes of the traffickers’ network appear in the course of a routine account. As in Hashimoto’s case, Hong Kong was often not the women’s final destination but rather a place of ‘transfer’ (iten 移転), as the Japanese consul noted in 1890, whence women were shipped to ‘ports in Australia or to Sandakan in British-controlled Borneo’.Footnote 80 Similarly, one of the leading Japanese residents on Thursday Island, Sasaki Shigetoshi, confirmed in an 1892 petition to Tokyo that the fifteen sex labourers there had been bought by their brothel owners through five different procurers in Hong Kong. He named two: from Chikuzen, Nishiyama Yoshizō; and, from Nagasaki, Ōtaka Yūichi – that is, the same man named by Hashimoto Usa:

These men put up a ‘Hotel’ sign and seem to be in the lodging-house business, but this is just a surface painting and behind the scenes the main business is actually to be found in the trading of unsightly women (shūgyōfujo). From what I hear of how they trade in prostitutes, they direct subordinating underlings who, with various devious tricks, abduct women of the right age from Kyushu or any other convenient place.Footnote 81

Five years prior to Hashimoto’s arrival on Thursday Island, Sasaki was foreshadowing the infrastructures of her passage: the steamship routes; the Ōtaka ‘lodging house’ in Hong Kong; the transnational networks of the recruiters; and the rhetorical tricks possibly used by Ōtaka to ‘strongly advise’ women like Hashimoto (her words). As Sasaki’s account in the Tokyo archives and a stream of telegrams in the Brisbane archives make clear, Hashimoto Usa was not the first such woman caught up in this infrastructure. Nor would she be the last: four days before she arrived in Hong Kong in July 1897, the Japanese consul there reported eight Japanese brothels and sixty-six Japanese prostitutes in the colony – but maybe as many as fifteen or twenty additional ‘mistresses’ (to Westerners) or trafficked women.Footnote 82 The arrival of Hashimoto’s group from Shanghai would merely have added to this total, had it been detected.

Thus, regardless of her intentions, Hashimoto Usa’s fate had quite probably been set in motion even before she left Nishiyama: by Ōtaka, a man pretending to run a hotel in Hong Kong, with a view to her eventual sale in Australia. And yet, as we shall see, she would speak of ‘boldly’ going to Thursday Island, as if this were her decision as much as his. Perhaps naively, I hear her voice in the adverb, suggesting as it does a kind of empowerment, her subjective framing of a situation which she must have known was beyond her control.Footnote 83 I also hear her voice in her adjectives, ‘distressed’ and ‘terrified’. Here, however, I suspect that she speaks for a plural experience, on behalf of the other women who also found themselves alone in a strange country – but whom Hashimoto will protect by not naming.Footnote 84

I Boldly Decided to Go

So I boldly decided to go to Thursday Island, and was accompanied there by Matsubara from Otaka’s lodging house –

We arrived at Thursday Island on the 11th day of September –

There were other women with Matsubara whom he brought to sell along with me –

After all that, Hashimoto Usa did not travel to Australia on the Yamashiro-maru. In a folder in the Japanese Foreign Ministry archives in Tokyo, I find a note stating that the Nanchang, a China Steam Navigation company steamship, departed Hong Kong on 27 August 1897 and landed at Thursday Island on 11 September. There it discharged, presumably among other passengers, two Japanese men and five Japanese women.Footnote 85 Even here, then, Hashimoto tries to protect her female compatriots by talking vaguely of ‘other women’ rather than giving her questioners a precise number.

The Japanese note is filed in a nine-volume folder, ‘Concerning restrictions to the passage of Japanese migrants in Australia’ – which gives a good sense of how Hashimoto’s journey was framed by concerned Japanese bureaucrats. A few pieces of paperwork later, the Japanese consul in Townsville sent his Tokyo colleagues a brief clipping from a Brisbane newspaper reporting on a question the home secretary, Sir Horace Tozer, had been asked in the Legislative Assembly on 21 September. (The member questioning Sir Horace, the consul added in a hasty postscript, was a Labour Party politician known for his radical Japanese-exclusion views.) Sir Horace had replied that ‘he had a record of every Japanese who had arrived since the recent discussion in the House on the question of Japanese immigration’.Footnote 86 This wasn’t strictly true; but it was nevertheless the case that Hashimoto Usa’s journey coincided with a frenzy of record-making in both Tokyo and Brisbane, thus producing her as an archival subject in a way that might not have occurred had she departed Nagasaki a year or two earlier.

From Tokyo, this documentary drive was initiated in March 1897 by deputy foreign minister Komura Jutarō (1855–1911), who directed Japanese consuls to report biannually on ‘the total number of unsightly women’ in their jurisdiction. (One outcome of this directive was the Hong Kong consul’s aforementioned figures on prostitutes and brothels in July 1897.) As Mihalopoulos has argued, this attempt to render the women visible stemmed from the assumption that the opacity of their lives was synonymous with their alleged unruliness.Footnote 87 By this logic, archivally to know was practically to control; and with such control, which included both stemming the numbers leaving Japan and deporting alleged delinquents back to Japan, the reputational damage to respectable overseas actors such as businessmen would be reduced. The performance of control was particularly urgent by 1897, given that New South Wales was in the process of passing an immigration act that would potentially constrain future Japanese business interests, and Queensland seemed likely to follow suit (see Chapter 4).

Meanwhile, in Brisbane the intensification of data collection was initiated by Sir Horace, who requested from his officials information on the impact of Japan’s 1896 Emigrants’ Protection Law – by which all Japanese emigrants were to be issued with passports – ‘upon the arrival of Japanese laborers and artisans’.Footnote 88 (One outcome of this request was the police reports from Cairns, Cooktown, Childers and so on, cited at the beginning of this chapter.) By September 1897, a few days after he had been questioned in the Legislative Assembly, Sir Horace had his numbers: 116 Japanese women in the colony as a whole, all of whom, with one exception (the consul’s wife in Townsville), ‘gain their living by prostitution’. Fully 34 of these women were to be found on Thursday Island, an increase from the 15 mentioned by petitioner Sasaki Shigetoshi five years earlier. Moreover, the regular telegrams that John Douglas sent to Brisbane from mid 1897 onwards – including noting the arrival of the Nanchang on 11 September – were also an archival manifestation of Sir Horace’s eye for record-keeping.Footnote 89

Thus, Hashimoto Usa happened to arrive on Thursday Island in a period of heightened bureaucratic production. Her interview was the outcome of two different archival agendas, in Tokyo and Brisbane respectively, aligning for a fleeting moment. Channelling his instructions from Sir Horace, it was John Douglas, I fancy, who asked her the question about passports, and who took particular interest in her reporting of Ōtaka’s advice that she could freely land [in Thursday Island] without passports. Echoing both the Japanese government’s view and the language of Sasaki’s anti-prostitution activism, it was John Douglas who declared, in an interview he gave to the Brisbane Telegraph two weeks after questioning Hashimoto, that women ‘smuggled out [from Japan] and brought on from Hongkong’ were ‘contraband’. ‘The evil,’ he continued, ‘is an increasing one, and ought to be checked’.Footnote 90 But over the years, Douglas had also displayed a more nuanced understanding of these Japanese women than many of his counterparts in Tokyo – as when he claimed that two women he had been asked to deport in 1891 were ‘undoubtedly prostitutes of a respectable and orderly type’.Footnote 91 Did he perhaps therefore have Hashimoto Usa freshly in mind when he noted, in his Telegraph interview, that although such ‘Japanese ladies […] are not a desirable addition to our population’, they nevertheless ‘behave very properly’?

We cannot know. But the fact that Hashimoto Usa’s statement was taken down is a testament not just to the production of knowledge generated by bureaucrats working in mutually complementary ways across transimperial space – that is, Tokyo, Wonsan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Thursday Island and Brisbane. It was also a testament to Douglas. Though he had been ordered to collect quantitative data, he also generated something qualitative in his archival paperwork. Hashimoto’s statement was a small victory for stories over statistics.

A Brothel at No 2 Yokohama Thursday Island

Matsubara is not himself the keeper of a brothel –

Matsubara made arrangement with Shiosaki the keeper of a brothel at No 2 Yokohama – Thursday Island –

I have entered into agreement with Shiosaki to pay him the sum of one hundred pounds sterling out of my earnings –

I think Matsubara has received from Shiosaki my large sum of money for passage lodging commission and other expenses alleged to be incurred on my behalf –

Unfortunately I fell into such a miserable state, but the act is voluntary and not against my will, and as Shiosaki has paid the amount demanded by Matsubara with my consent I am now under obligation to pay him £100 –

In the wealth of detail provided by Hashimoto Usa to her interrogators, one question was so obvious as to go unasked: why Thursday Island? A young migrant’s intention to go to Singapore or Hong Kong, either for a visit or for work, makes sense to a twenty-first-century reader given the economic magnetism of both metropolises well beyond her time. But why did Otaka the keeper of the lodging house tell Hashimoto that a tiny island off the northernmost tip of Queensland was a very good place to make money? (By which, of course, he meant a good place for him to make money by trading her.)