Introduction

In the UK, the number of deaths due to substances far exceeds other preventable deaths such as melanoma, suicide, road traffic accidents and AIDS, which total around 10,000 per annum. The death rate due to drugs in the UK is now the highest in Europe: opiate and cocaine deaths are at an all-time high (Figure 25.1). Alcohol is responsible for approximately 25,000 deaths every year and is now the leading cause of death in men under fifty years of age. Tobacco still leads to 80,000 deaths every year. See Box 25.1 for definition of terms used in this chapter.

Box 25.1 Terminology

The terms addiction and dependence will be used interchangeably, as will the terms ‘drug’ or ‘substance’.

The terms ‘drug’ and ‘substance’ cover those psychoactive substances that are legal or licit and commercially available (tobacco and alcohol) as well as those that are illegal or illicit.

These terms will also be used to describe ‘street’ use of drugs which includes:

drugs bought over the Internet;

prescribed medication (e.g. benzodiazepines, opiate, opioid and gabapentinoid drugs) used in a manner not indicated or intended by a medical practitioner; and

use of over-the-counter preparations such as codeine-based products (e.g. cough medicines, decongestants).

Illicit drugs include:

cannabinoids (tetrahydrocannabinol or THC and cannabidiol) and synthetic cannabinoids (‘spice’);

central nervous system depressants such as opiates and opioids (e.g. morphine, codeine, heroin; and buprenorphine, oxycodone, methadone, fentanyls);

stimulants (e.g. cocaine, crack cocaine, amphetamines and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, known as MDMA or ecstasy, khat);

hallucinogens: lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and psilocybin (magic mushrooms); and

novel psychoactive substances (NPS).

The health, social and criminal justice systems currently in place are not able to provide the flexible response in which the public can have confidence and to which they can adhere. Moreover, vindictive policies which criminalise people with substance dependence are therefore also unlikely to yield positive outcomes as addicts are suffering from a clinical disorder which requires treatment and support rather than indiscriminate sanctions.1 Addictions exact a high price in preventable illness, disability and deaths and are a marker of deprivation and inequality.2

Social Epidemiology, Medical Treatment and Drug Laws: 1960–1990

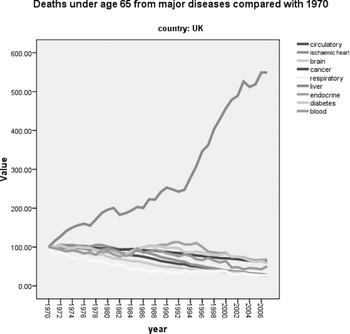

Current policy ambition is to reduce use rather than the harms caused by substances, and tobacco consumption has decreased but alcohol consumption has doubled over the last fifty to sixty years. Deaths from liver disease have demonstrated a steep rise between 1970 and 2006, 80 per cent of which are alcohol related and 20 per cent due to viral hepatitis (see Figure 25.2). Alcohol consumption increased as it became more affordable and sales from corner shops and supermarkets for off-premises consumption became legal. The pattern of drug use, too, has changed markedly over the last 100 years. Between 1920 and 1960, drug use was very low and mostly by people with other conditions. The Dangerous Drugs Act prohibited the sale of drugs without a medical prescription.3 Medical prescription to addicts was allowed as a last resort. This came to be known as the ‘British System’.

Figure 25.2 Standardised mortality rates from different diseases in the UK

Note the remarkable rise in deaths from liver disease as compared with other medical conditions: 80 per cent of these are due to excessive alcohol use and 20 per cent to viral hepatitis

From the 1960s, there was a new development: young drug users associated with the music scene appeared. Apart from the obvious link with entertainment, drugs such as cannabis, amphetamine or ‘uppers’ (in the form of an over-the-counter Benzedrine inhaler) and LSD came to symbolise their new ‘alternative’ identity with the hippy youth protest movement, its political values and new ways of dressing and behaving. This aroused suspicion and even anger in both the public and politicians. The Advisory Committee on Drug Dependence established the independent expert Wootton Committee review of cannabis and concluded that, despite the fact that the dangers of cannabis use had been exaggerated, it should stay illegal but in a lower class of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, that is, cannabis-related offending should be regarded as less serious than that related to opiates and cocaine and penalties be reduced.4 This advice was ignored and some forms of cannabis stayed in Class A and the rest in Class B.

During this time, the Home Office spotted that notifications of cases of heroin addiction had increased from 50 in 1958 to 1,299 in 1967 and that 80 per cent of users were under the age of 29. They were mainly young men who injected intravenously and were perceived as some threat to society. As this new cohort differed markedly from the few older middle-class people who were treated under the ‘British System’, the second Brain Committee in 1964 concluded that heroin use was a ‘socially infectious condition’.5 Its recommendations included new specialist addiction treatment units (Drug Dependence Units, or DDUs) under psychiatric leadership; compulsory notification of new cases; licences for doctors to prescribe heroin or cocaine at these centres; and, importantly, abstinence rather than maintenance with heroin or a substitute medication. Withdrawal treatment became the treatment of choice, and when this failed, addicts sought alternative treatment or drugs. This strategy appeared to curb the drug problem to an extent but not entirely.

Cannabis remained popular and convictions increased. During the 1970s, injection of barbiturate drugs became the most common form of death from overdose, but this subsided when Southwest Asian heroin began to make an appearance on the black market and benzodiazepines replaced barbiturates as they were considered a safer and non-addictive sedative medication at the time. Furthermore, as prescribed injectable amphetamine and illicitly produced amphetamine powder, which was either snorted or injected, became available, it became the most widely used drug after cannabis. Services remained focused on heroin users but, because of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, all injecting drug users became an increasing cause for concern.

A new heroin epidemic emerged in the 1980s when cheaper black market heroin was imported from the Golden Crescent (Iran, Afghanistan and Pakistan). This cohort differed in that now it was adolescents and young adults who were inhaling (‘chasing’) heroin, and although this route of use protected against HIV, many did turn to injecting and suffered serious complications. Use of cocaine and crack also increased and intravenous use of the benzodiazepine temazepam emerged as a problem. While it is estimated that in 1994 there were about 67,000 people in treatment for drug misuse, by 2007 there were 195,000.6

Following on from these developments, the revision of the Dangerous Drugs Act led to the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.7 The Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (MDAct 1971) has two separate dimensions, classes and schedules. Schedule 1 contains all drugs that have no medicinal value. Schedules 2–5 define the degree of safekeeping that different medicines require; this is because of the medicinal value of many ‘misused’ or recreational drugs.

Classes define the penalties for illegal possession. Three classes of drugs emerged: those continuing to enjoy recognition as medically useful but also associated with abuse (e.g. opioids, amphetamine); those that lost recognition as medicines and continued to be associated with abuse (e.g. cocaine, LSD, MDMA, magic mushrooms); and those that had never enjoyed recognition as medicines and continued to be associated with abuse (e.g. crack cocaine and ketamine analogues). Within each class, penalties intending to serve as deterrents differ in severity, depending on whether they are for possession for personal use, dealing, supply or importation. These penalties are meant to indicate the relative harms of the different drugs and act as a deterrent to use/supply. Severity of penalties is related to the potential of each drug for individual harm rather than cumulative social harm, which arguably would be more rational. They reflect the predominant UK policy of prohibition of recreational drug use that has been in place for nearly a century. As the costs of this undertaking in terms of social and personal damage are not inconsequential, there is a case for considering the proportionality of the penalty to the harms that may accrue both socially and individually.

Emergence of Public Health and Harm Reduction Approaches

There were a range of responses to the heroin epidemic of the 1980s, including the national campaign ‘Heroin Screws You Up’ aiming to prevent its initiation, and expansion of facilities for medical treatment. New multidisciplinary services offered residential rehabilitation. The objective was to persuade addicts to abstain. However, the epidemic of HIV/AIDS transformed this strategy. Accordingly, a flexible harm reduction policy was recommended by the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD). Implemented under the Thatcher government, it further expanded services and instituted needle exchange and methadone prescription. It was credited with the less than expected increase of HIV infections in drug users; in fact, the UK had the lowest in Europe. Despite these measures, during the 1990s heroin use continued to increase, especially among adolescents and young people, and ecstasy (MDMA) use started to materialise as part of the rave dance scene. This development caused significant disquiet and stirred up much debate within criminal justice, political and health settings.

Over the previous decades, illicit drug use itself was being increasingly conceptualised by younger people as ‘normal’ behaviour, while smoking was considered a more ‘deviant’ practice and perceived as a ‘drug’. It was argued that, had tobacco been discovered at the same time, it would not have been a legal substance. Restrictions on smoking and drinking and relaxation of the drug laws began to be examined. Continuing recreational use of licit substances, such as prescription drugs, added increasing complexity.

A model of public health, derived from that applied to tobacco, began to influence thinking on drugs and alcohol. Epidemiology became the research tool which underpinned the investigation of alcohol and drug use at the population level and represented a steer away from a strictly ‘medical’ model.

Thus, alcohol policies, though led by psychiatrists, also embraced a more varied group of disciplines and organisations such as the voluntary sector, the law and the police. This was because alcohol was conceptualised as a problem of the many, not just the few severely affected by the ‘disease’ of alcoholism. A landmark study by Edwards and colleagues in 1977 compared the impact of structured, individual advice, with the full treatment paraphernalia in use at the time. Advice, by and large, did as well as the already prevalent more complex treatment at twelve‐month follow-up.8 Encouraging the general population to reduce both smoking and alcohol consumption by ‘brief interventions’, mainly in primary care, was promoted.

Following the election of the Conservatives in 1979, this became problematic for politicians who were wary of imposing restrictions on advertising, increasing taxation and introducing licensing. During this time drug treatment had moved from primary care–based treatment to that which was led by psychiatric specialists. This was underscored by the need to notify the Home Office (rather than the Department of Health) of new cases, much like infectious disease control, as drug use was considered a ‘socially infectious disease’. Ideas around risk and the health of the population formed part of the thinking. Lifestyle, self-help and control as well as abstention were now entwined with the public health agenda. So, the impact of substance use on the whole population, as well as the individual who needed treatment, mattered.

This overall strategy of harm reduction was instituted after Labour came to power in 1997. It was implemented through an expansion of treatment programmes in 2000 which did reduce the rising death toll from opioids (see Figure 25.3). As penalties for drug offences were also rising, Drug Treatment and Testing Orders were introduced to engage users in treatment which meant that drug treatment became inextricably linked to criminal justice. In 2004, an Alcohol Harm Reduction Strategy was introduced to combat the massive rise in alcohol harms (e.g. Figure 25.2) and it was also based on the model of drug harm reduction.

In parallel, as the drug scene unfolded, since 1960 there had also been significant progress in the understanding of addiction and, to some degree, the associated harms to the individual and to society. The UK played an important role in the growth of this advancement. One key development in the 1970s was that novel terminology replaced the term ‘addiction’: the concept of ‘dependence’ was born and it could be applied to all substances. Dependence was defined by a set of criteria to diagnose or categorise the condition, be it because of drug, alcohol or tobacco use. Momentum around this conceptual breakthrough gathered so that, in due course, dependence came to be regarded as a chronic relapsing brain disorder.9

Towards an Understanding of Mechanisms and Harms: The Contribution of Neuroscience

Historically, addiction disorders have been portrayed – or understood – as a moral failing, a bad habit. Substance misusers may be treated in the acute phase of their illness in medical settings but, if left untreated, as they often are, they are then prone to poor medication adherence, poor control of common disorders such as hypertension and diabetes, increased risk of cancers and decreased effectiveness of treatments for pain. Substance misusers have not been considered worthy of first-class care compared to people with other preventable or treatable long-term conditions.

The remarkable contributions of neuroscience over half a century, 1960–2010, have demonstrated the biological basis of substance misuse, which can become a chronic medical condition, much like diabetes and hypertension. Recent research has demonstrated that a drug that induces dependence initially produces changes in reward neurotransmitters and neural circuitry which are (perhaps permanently) affected after repeated use. Eventually, the user loses control due to the development of negative physiological and emotional states and habit entrenchment. This neuroscience-based analysis in no way precludes an appreciation of the social, cultural and political factors that influence initiation and continuation of substance use.

Over this time, effective and innovative pharmacological treatments have forged ahead and continue to do so. There is a diversity of medications based on detailed knowledge about how they block the action of drugs such as opiates, stimulants, benzodiazepines and cannabis. Methadone has been and continues to be prescribed to those with heroin dependence and nicotine replacement to tobacco smokers. Newer medications such as buprenorphine and naltrexone for opiate dependence and acamprosate for alcohol dependence now form part of the pharmacological treatment options available. Psychological treatments, too, have found favour with service providers, and a combination of psychosocial interventions and medications are often recommended.10

It has become much clearer that the lack of response to treatment, rather than being due to poor character, lack of willpower or self-control, has very likely been rooted in an inadequate understanding of the nature of the problem. Refusing to recognise that the provision of resources to effectively treat, research and educate professionals and the public about addiction diminishes legitimate optimism derived from this substantial body of research.

As important are fair and appropriate drug policies, that is, public laws and regulations which can be expected to reduce harms to society while minimising unintended consequences. This stance recognises that psychological, social and political processes may lead to exacerbate and even thwart access and responsiveness to appropriate treatment. It also acknowledges that the biological and psychosocial drivers of addiction are unlikely to disappear even if abstinence is achieved. Understanding of brain mechanisms can be translated within the individual and wider social context.

Drug Laws in the UK: Lessons Learnt?

The justification for the illegality of many drugs is that they are harmful and hence criminal sanctions are necessary to reduce the harms to society and to individuals because they will act as a deterrent to their use.

For the last sixty years, the UK drugs policy has been controlled under two Acts of Parliament. Medicines are controlled under the Medicines Act and recreational drugs under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. In practice, many drugs – for example opioids, ketamine, benzodiazepines and stimulants – are controlled under both Acts which makes the position unnecessarily complicated as they come under the control of two different ministries of state.

Up until the early 1970s, rather than the policy debate around the drug laws centring on harms, it was focused on the morality of drug taking. In an attempt to redress this to some extent, the Misuse of Drugs Act in 1971 was introduced. This included understanding of the perceived harms caused by drugs, but they were not as well understood then as now. The ACMD was established to ‘keep the drug situation under review and to advise ministers on the measures to be taken for preventing the misuse of drugs or for dealing with problems connected with their misuse’. One of its key objectives is to decide on the relative harms of drugs and so locate them within the classes A, B and C.

Since 1971, there has been some movement of drugs between classes. Ketamine and GHB have come under the control of the Act. Methamphetamine has moved from Class B to Class A. Magic mushrooms have been made Class A and benzylpiperazine Class C. Cannabis has moved from Class A/B to C and then back to Class B. Until 2009, all governments had followed the advice of ACMD, but then, for the first time, their recommendations about cannabis and ecstasy were not heeded.

The public, policymakers and scientists need to act in unison to produce an evidence-informed, balanced and workable response as substance use and misuse remain a feature of everyday life in the UK today. Arguably the most important example of the divergence between science and policy is in the classification of what constitutes a ‘legal’ or ‘illegal’ drug. Alcohol, which is, of course, legal and widely available, produces considerable harm. Tobacco, too, is highly addictive and harmful but legal. Cannabis, on the other hand, remains illegal in many countries following the ban in 1961 by the UN convention but does relatively little harm.11 As another example, some ‘drugs of abuse’ have medicinal value – for example, opioids, benzodiazepines, amphetamines and constituents of cannabis – so the regulations make allowance for these. However, other drugs such as psychedelics (e.g. psilocybin) and MDMA with lesser harms and arguably with therapeutic potential for alcohol dependence, obsessive-compulsive disorder and PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) are not currently available legally.12

This issue has been examined in a multi-criteria decision analysis incorporating sixteen parameters of health and social harms of different drugs as illustrated in Box 25.2.13 The results demonstrate a striking lack of correlation between harms and the degree of prohibition (see Figure 25.4). This has been internationally replicated in Australia and Europe.

Harms to users:

Drug-specific mortality

Drug-related mortality

Drug-specific harm

Drug-related harm

Drug-specific impairment of mental functioning

Drug-related impairment of mental functioning

Loss of tangibles

Loss of relationships

Harms to others:

Injury

Crime

Economic cost

Impact on family life

International damage

Environmental damage

Decline in reputation of the community

One key element underpinning the value of systematic harm assessment of different drugs is that the availability of less harmful drugs leads to lower levels of harms to users. One of the most remarkable natural experiments that support this was the rise and subsequent fall of mephedrone in the UK (see Figure 25.5). This synthetic cathinone was legal in 2008 when it became popular in the UK. Within a few months, it had commandeered a significant part of the recreational stimulant market. This led to huge media hysteria with exaggerated claims of harms that, in effect, forced the Labour government to ban it just before the 2010 general election. Several years later, it became clear that mephedrone use had very significantly reduced deaths from cocaine and amphetamines. It appears that a significant proportion of the users of these drugs had switched to mephedrone, probably because it was legal, easily available and comparatively safe. Once mephedrone was made illegal, they switched back to their original stimulant and deaths from cocaine and amphetamine have reached all-time highs.

At this point, it is worth noting that the use of tobacco and alcohol products falls under separate age of purchase controls and taxation and are regulated food or commodities.

As the historical overview outlines, the profile of users changes as do the type and pattern of use of substances changes over time. Substance users can be very variable in terms of social status and health conditions. They have multiple needs, including being stigmatised, socially deprived and having traumatic life histories, mental health problems and living on the margins of society: the homeless, migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

Substances are now commonly consumed in combination, and some combinations are more dangerous than others. New drugs emerge and, sometimes, if a particular drug becomes difficult to obtain because of either a change in the law or reduced supply, a more potent drug is developed. Several examples of this are cannabis and heroin which have been supplemented by synthetic cannabinoids or fentanyl. Very often users are not aware of what precisely is contained in the drugs they are using and so are not aware of the risk to which they are exposing themselves. Laws and policies need to take account not only of the type of drug and extent of use but also of these changing profiles of both drug and user.

Future Directions: 2010 and Beyond

In 2007, Sir David King, former UK chief scientific adviser, predicted improved treatments for addiction and other mental health disorders and the development of newer recreational drugs, some of which may lead to fewer harms and lower risks of addiction than the substances in use today.14

In 2009, one of us, David Nutt was dismissed as Chair of the Advisory Council for the Misuse of Drugs after pointing out that current government policy and the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 were not evidence-based. Specifically, he commented that among the most harmful drugs in the UK were legal ones – that is, alcohol and tobacco – and the current government approach to focus on ‘illegal’ drugs was a missed opportunity to reduce overall drug harms. His removal was justified on the grounds that, as the chief government advisor, he should not be opposing government policy which failed to acknowledge that these were drugs.

Since then, with the advent of ‘austerity’, the UK has witnessed the decimation of treatment services for drugs, alcohol and smoking cessation, with numbers of consultant addiction psychiatrists and trainees dramatically reduced.15 This is a false economy: the stark increase in deaths is a chilling reminder of the gravity of the state of play.

There have been new issues and new substances as well as new groups of substance misusers. While much of the debate has centred on younger people, including children and adolescents, attention has recently turned to older people who are misusing cannabis and heroin as well as over-the-counter and medically prescribed medications.16 For example, there is now an appreciation that addiction is a lifetime problem for some and accumulating evidence that older people are vulnerable to the impact of legal and illegal use.17 In addition, we see the emergence of an ever-growing number of designer ‘novel’ psychoactive substances, available through the Internet; the popularity of e-cigarettes (vaping) for many substances apart from nicotine; and the changes in the legal status of cannabis so that it can be prescribed as a medicine. There is exciting potential for the development of new pharmaceutical agents for the treatment of substance misuse.

What half a century has shown us is that, overall, deaths from substance use have risen. There are a broad range of factors that contribute to this sad situation. The last years can be characterised as having seen prohibitionist developments in UK drug laws, while those evidence-based policies that could reduce the use of alcohol, especially minimum unit pricing, have not been introduced universally. Scotland and, recently, Wales have introduced these changes and preliminary data from Scotland suggest a decrease in alcohol use and its harms. However, in England, encouraged by the drinks industry, the government has resisted any change. There have been some significant steps forward in that smoking advertising has been banned and there are restrictions on smoking in public places, bars and restaurants, but the alcohol industry has managed to avert similar controls. These strategies have failed to achieve their goal and sometimes have even led to the development and use of more harmful substances. Particularly disturbing perhaps is that the Schedule 1 controls make it very difficult to use certain drugs for medical research.18

As is the case in many countries now, policy regarding substances is best placed within health care departments rather than the Home Office. For example, in the Netherlands, testing and regulated access to some substances has largely eliminated deaths from new recreational drugs; and in Portugal, the provision of appropriate comprehensive treatment interventions and facilities has significantly reduced opioid deaths. Further examples include prescription of medicinal cannabis as an alternative to opioid analgesics and the development of safer injecting/drug consumption rooms for those who have tried other methods.

Conclusion

The last sixty years has been an extraordinarily dynamic period in terms of both the rapid march of scientific progress and the changing landscape of drug use, drug harms and drug policy. It is fitting to end with prescient excerpts from an interview by Griffith Edwards, the quintessential figure in addiction psychiatry in the UK between 1960 and 2010 and editor-in-chief of the journal Addiction between 1979 and 2004:

Addiction science at its most productive knows no substance boundaries. There is great benefit in comparing across substances the mechanisms of dependence, distributions of consumption, treatment processes, policy and control responses.

He valued:

Daring to provoke debate, but with respect for everyone’s opinion.

He summarised key components as follows:

Our agenda themes (include) to encourage debate on the ethical dimension (in journal publishing), the relationship between science and policy, to promote internationalism (and) enhancing the quality of science.19

Key Summary Points

Substance use and misuse remain a feature of everyday life in the UK today. They are a cause of death and disability and a marker of deprivation and inequality. The health, social and criminal justice systems currently in place are not able to provide the flexible response in which the public can have confidence and to which they can adhere.

While much of the debate has centred on younger people, including children and adolescents, attention has recently turned to older people who are misusing cannabis and heroin as well as over-the-counter and medically prescribed medications.

The remarkable contributions of neuroscience over half a century, 1960–2010, have demonstrated the biological basis of substance misuse, which can become a chronic medical condition, much like diabetes and hypertension.

There is exciting potential for the development of new pharmaceutical agents for the treatment of substance misuse.

An aspiration we have is towards a new public understanding of addiction through education so that people can make informed choices based on realistic policies.