Introduction

The 1959 Mental Health Act represented, by any standard, a ‘paradigm shift’ in the way in which mental illness was construed, not just in Britain but anywhere.

Its predecessor was the Lunacy Act of 1890. Kathleen Jones, in her influential History of the Mental Health Services characterised that Act thus:

The Act itself is an extremely long and intricate document, which expresses few general principles and provides detail for almost every known contingency. Nothing was left to chance, and very little to future development.

…

From the legal point of view it was nearly perfect … From the medical and social viewpoint, it was to hamper the progress of the mental-health movement for nearly 70 years.1

Laws governing detention and treatment in the nineteenth century were developed in the setting of the expanding asylum system. The early enthusiasm for ‘moral treatment’ failed to live up to its promise. The numbers of those detained in the asylums grew far beyond what was originally envisaged.

Under the Lunacy Act 1890 admission to an asylum or licensed house depended on whether the case was private (involving a justice of the peace and two medical certificates) or pauper (involving a Poor Law receiving officer or the police, a medical certificate and a justice of the peace).2

Admission by inquisition, whose origins dated back to the fourteenth century applied to so-called Chancery lunatics – expensive and affordable only to those with large estates and great wealth. The alleged lunatic could request a trial of their sanity by jury.

There were detailed regimes of visitation by Lunacy Commissioners – unannounced, at an hour, day or night. A report book for instances of mechanical restraint was kept; a medical certificate was necessary for each instance.

Discharge arrangements were complex and could differ for private versus pauper patients. They might involve the person signing the petition for the reception, the authority responsible for the maintenance of the pauper patient, two Lunacy Commissioners – one legal and one medical – or three members of the visiting Local Authority committee.

The Mental Treatment Act 1930 followed a Royal Commission on Lunacy and Mental Disorder 1924–6.3 It proposed that mental illness should be viewed like any other illness, and its recommendation that treatment should not necessarily be contingent upon certification was accepted. The Lunacy Act was amended but earlier legislation was not replaced. The Act introduced ‘voluntary admission’ by written application to the person in charge of the hospital. Non-objecting but non-volitional patients, called ‘temporary’, could be admitted under a non-judicial certificate. An essential condition in the application for reception of a ‘temporary’ patient was that the person ‘is for the time being incapable of expressing (him)(her)self as willing or unwilling to receive such treatment’.4 For many clinicians, the meaning of this provision lacked clarity, accounting for a huge variation in its use – from 34 per cent to 0 per cent.5

Magistrates continued to be involved in overseeing compulsory hospital admissions. The Act authorised local authorities to set up psychiatric outpatient clinics in general and mental hospitals, but the hospital remained the focal point for psychiatric provision.

The Mental Health Act 1959

The Mental Health Act 1959 followed the key recommendation of the Percy Royal Commission, established in 1954, ‘that the law should be altered so that whenever possible suitable care may be provided for mentally disordered patients with no more restriction of liberty or legal formality than is applied to people who need care because of other types of illness’.6

The Act repealed all previous legislation.7 Informal admission was now the usual method of admission. For the first time since 1774, there was no judicial authorisation for a compulsory admission. Patients could be admitted to any hospital or mental nursing home without any formalities. This replaced the ‘voluntary admission’ set down in the Mental Treatment Act of 1930 where the patient signed admission papers. Non-volitional patients could be admitted informally provided that they did not positively object to treatment.

Mental disorder was defined as ‘mental illness; or, arrested or incomplete development of mind (i.e. subnormality or severe subnormality); or, psychopathic disorder; or any other disorder or disability of mind’.

Psychopathic disorder was defined as a persistent disorder resulting in abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible conduct and susceptible to medical treatment. Persons were not to be regarded as suffering from a form of mental disorder by reason only of promiscuity or immoral conduct.

There were three kinds of compulsory admission:

Observation order: up to twenty-eight days’ duration, made on the written recommendations of two medical practitioners stating that the patient either (1) is suffering from a mental disorder of a nature or degree which warrants his (sic) detention under observation for a limited period or (2) that he ought to be detained in the interests of his own health and safety, or with a view to the protection of other persons.

Treatment order: for up to a year, to be signed by two medical practitioners. The grounds were:

(a) The patient must be suffering from mental illness or severe subnormality; or from subnormality or psychopathic disorder if he is under the age of twenty-one.

(b) He must suffer from this disorder to an extent which, in the minds of the recommending doctors, warrants detention in hospital for medical treatment; and his detention must be necessary in the interests of his health and safety, or for the protection of other persons.

Emergency order: following an application made by the mental welfare officer or a relative of the patient and backed by one medical recommendation. The patient had to be discharged after three days unless a further medical recommendation had been given satisfying the conditions of a treatment order.

A Mental Health Review Tribunal (MHRT) alone took over the previous watchdog functions of the Lunacy Commission (which had later become the Board of Control). Detention could be reviewed at the request of patients or relatives or at the request of the minister of health. The tribunal consisted of an unspecified number of persons: legal members appointed by the Lord Chancellor; medical members appointed by the Lord Chancellor in consultation with the minister; lay members having such experience or knowledge considered suitable by the Lord Chancellor in consultation with the minister.

A patient was discharged by the Responsible Medical Officer (RMO), by the managers of the hospital, by an MHRT, by the patient’s nearest relative – though with a possible RMO veto – or, in the case of subnormality or psychopathy, if the person had reached the age of twenty-five.

Guardianship, which had its origins in mental deficiency legislation and promised a degree of control in the community, could now be applied to those with a mental disorder.

Space does not allow us to discuss provisions for mentally disordered offenders in detail. In brief, courts could order admission to a specified hospital or guardianship for patients with a mental disorder of any kind, founded on two medical recommendations. Courts of Assize and Quarter Sessions could place special restrictions on the discharge of such patients. Power to grant leave of absence, to transfer the patient to another hospital or to cancel any restrictions placed on their discharge was reserved to the Home Secretary. Limitations were placed on the appeal of such patients to an MHRT. Those found ‘Not guilty by Reason of Insanity’ were detained during ‘her Majesty’s pleasure’ by warrant from the Home Secretary. The Mental Health Act 1959 provisions by and large resemble those of today, with a significant change concerning the power of the MHRT in 1982, discussed later. The medical profession was united in its enthusiasm for the new provisions and the status of psychiatrists in the medical sphere was enhanced.

The Context of This Radical Change in Mental Health Law

A new optimism had emerged concerning the effectiveness of psychiatric treatment, with a new expectation that patients would return to their communities following a short admission. Jones talked in terms of ‘three revolutions’: pharmacological, administrative and legal.8

The ‘Pharmacological Revolution’

The standing of psychiatry as a medical speciality, based on scientific principles, was boosted with the introduction in the early 1950s of the antipsychotic drug chlorpromazine. Admissions had become shorter and much more likely to be voluntary. The antidepressants, imipramine and iproniazid, were introduced later in the decade. New psychosocial interventions, such as the ‘therapeutic community’ and ‘milieu therapy’ looked promising. There was a sense of a ‘therapeutic revolution’.

The ‘Administrative Revolution’

A 1953 World Health Organization (WHO) report (Third Report: The Community Mental Hospital) described new models for mental health services. Combinations of a variety of services were proposed, including ‘open door’ inpatient units, outpatients, day care, domiciliary care and hostels. Earlier treatment, it claimed, meant fewer admissions; chronic patients could be satisfactorily cared for at home or boarded out. The report significantly influenced the Royal Commission’s determinations.

There were other administrative considerations. In 1948, the new National Health Service (NHS) found itself responsible for the management of 100 asylums, each with its own regulations and practices. Their average population was around 1,500 patients. Patients with a ‘mental illness or mental deficiency’ occupied around 40 per cent of all hospital beds.9

The ‘Legal Revolution’

Some legal matters were complicated by amendments introduced by the National Health Service (NHS) Act 1946. There was also a welfare state–influenced reimagining of law of this kind, now to be seen as an ‘enabling’ instrument as opposed to a coercive or constraining one.

Tackling the stigma of mental illness was another theme. There was agreement that stigma was heightened by what was called the ‘heaviness of procedure’ manifest in the magistrate’s order, linking in the public’s mind the deprivation of liberty for the purposes of treatment with that for the purposes of punishment.

Unsworth summarised the significance of the 1959 Act as a negation of the assumptions underlying the Lunacy Act:

The [1959] act injected into mental health law a contrary set of assumptions drawing upon the logic of the view of insanity as analogous to physical disease and upon reorientation from the Victorian institution-centred system to ‘community care’. … Expert discretion … was allowed much freer rein at the expense of formal mechanisms incorporating legal and lay control of decision-making procedures.10

A ‘pendulum’ thus had swung through almost its full trajectory, from what Fennell and others have termed ‘legalism’ to ‘medicalism’,11 a form of paternalism.

A warning was sounded in parliament, however, by Baroness Wootton:

Perhaps there is a tendency to endow the medical man with some of the attributes that are elsewhere supposed to inhere in the medicine man. The temptation to exalt the medical profession is entirely intelligible … but I think it does sometimes place doctors in an invidious position, and sometimes possibly lays them open to the exercise of powers which the public would regard as arbitrary in other connections.12

Mental Health Act 1983

Twenty-four years later, a new Mental Health Act was passed.13 While the general outline of the 1959 Act was preserved, there was a significant swing of the ‘pendulum’ towards a new form of ‘legalism’.

Among the changes introduced in the 1983 Act, the following were notable:

1. For the first time, the idea of consent to treatment, even if the patient was detained, made its appearance in mental health law. A requirement for consent was introduced for certain hazardous or irreversible treatments – psychosurgery and surgically implanted hormones. These now required the patient’s consent and approval by a panel of three people, including a psychiatrist, appointed by the Mental Health Act Commission (see item 4). Further, consultation with two persons professionally involved with the treatment (other than the patient’s consultant) was needed. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and the administration of medications for the mental disorder beyond three months required consent or a second opinion if the person could not or did not consent.

2. An expanded role and enhanced training was introduced for ‘approved social workers’ in respect of a social assessment.

3. Access to review of detention by the MHRT was expanded and now included patients under a 28-day ‘assessment’ order and automatic review with renewal of a treatment order. Patients became entitled to publicly funded legal representation.

4. An oversight body concerning detained patients, the Mental Health Act Commission, was established. It will be recalled that there was no such body under the 1959 Mental Health Act.

5. Patients suffering from ‘psychopathic disorder’ or ‘mental impairment’ could only be detained if their behaviour was ‘abnormally aggressive or seriously irresponsible’ and if treatment was likely to alleviate or prevent a deterioration of their condition (i.e. a ‘treatability’ criterion’).

6. A duty was placed on the District Health Authorities and local social services authorities to provide aftercare services for patients admitted on a treatment order or on some forensic orders.

In these domains, the rights of persons with a mental disorder were thus enhanced.

What Was the Context of These Changes?

In an extended history of mental health services, Jones began her analysis of the post-1959 period thus:

After the passing of the 1959 Act, it would have been reasonable to expect a period of consolidation and cautious experimentation; but within two years, the whole scene changed. In 1961, a new Minister of Health, Enoch Powell, announced a policy of abolishing mental hospitals, and cutting psychiatric beds by half … Opposition to this draconian policy was muted by three new theoretical analyses … opposed to mental hospitals for very different reasons.14

She was referring to Szasz, Goffman and Foucault. We shall come to them later in this section (see also Chapter 20).

The Ministry of Health’s A Hospital Plan for England and Wales followed Powell’s ‘Water Tower speech’. It proposed the restriction of hospital care mainly to the acute sector. Under a ‘parity of esteem’, this applied to psychiatry just as it did to the rest of medicine. Thus commenced a huge reduction in the number of hospital beds. At the same time, the Department of Health faced increasing fiscal pressures arising from the need to refurbish and maintain decaying public hospitals. The forces leading to the policy of deinstitutionalisation here overlapped with those acting to reduce admissions, including recourse to involuntary hospitalisation. Some noted an ‘unnatural alliance’ between civil rights advocates on the left, who distrusted the state and psychiatric expertise, and monetarist conservatives, who were concerned with the high institutional costs of mental health care (see also Chapter 31).

Highly publicised scandals involving mental hospitals continued – there were some twenty serious inquiries into maltreatment between 1959 and 1983. Faith in the effectiveness of medication – and in pharmaceutical companies, especially following the thalidomide inquiry – was faltering.

Proposals from some academic authorities that outcomes would improve if treatment were focused in the community rather than in hospitals were welcome to government. Evidence was offered that ‘total institutions’ like mental hospitals, in which almost every aspect of the resident’s life is subservient to the institution’s rules, far from being therapeutic, in fact contribute to a dehumanising erosion of personal identity, dependency and disability. Here Goffman’s 1961 Asylums and Barton’s 1959 Institutional Neurosis were influential.15

Joined to these criticisms was another set of voices denying the legitimacy of the psychiatric enterprise itself. Key figures in this loosely termed ‘anti-psychiatry’ movement included three psychiatrists – Thomas Szasz, R. D. Laing and David Cooper (see also Chapter 20). Szasz held that ‘mental illness’ was a ‘myth’ and had no kinship with ‘real’ illness; so-called mental illnesses were ‘problems of living’, not brain diseases.16 From a rather different perspective, Laing and Cooper argued that insanity was an understandable reaction of some to impossible family pressures or, indeed, a society gone insane.17 The experience of psychosis, they claimed, handled correctly – as opposed to conventional treatment – could be transformative.

In significant ways congruent with the ‘anti-psychiatry’ movement were the ideas of Michel Foucault. His Histoire de la folie, published in 1961, appeared in a much abridged form in English in 1965 (as Madness and Civilization) featuring a polemical introduction by David Cooper.18 Madness and Civilization examined how the notion of ‘mental illness’ assumed the status of ‘positive knowledge’ or objectivity and its irreconcilability with society’s growing valorisation of ‘productive’ citizenship. Foucault argued that psychiatrists’ expertise lay in asylum-based governance and non-medical practices, such as techniques for the normalisation of certain sorts of socially transgressive behaviours.

Thus, while these figures differed significantly in their theories, they had in common a critique of psychiatry’s basic tenets, its social role and the institutions in which these were realised. Their ideas found a place within a broader counterculture movement prominent in the 1960s and 1970s, which helped to bring them to the attention of a wider public.

A further significant influence was the civil rights movement in the United States, increasingly effective in the 1960s and 1970s. Civil rights were progressively asserted for groups subject to discrimination – African Americans, prisoners, women, persons with mental illness and persons with disabilities. An essential instrument was the law; a number of key legal decisions led to changes in institutional practices.

Increasingly publicised abuses of psychiatry in the Soviet Union during the 1970s and early 1980s seemed to point to the fact that, unless involuntary hospitalisation was the subject of special scrutiny, arbitrary detention could follow.

The key player in fostering reform of mental health legislation in the 1970s was the National Association for Mental Health (now Mind). Founded in 1946, it started as a traditional voluntary organisation, a partnership between professionals, relatives and volunteers, aimed at improving services and public understanding. Its character, described by Jones as ‘duchesses and twin-set’, changed in the 1970s (see also Chapter 14).

The organisation was shaken by a serious, though failed, attempt of a Scientology takeover. A ‘consumer’ orientation and a focus on human rights followed, marked by the appointment of Tony Smythe as director in 1974. He was previously secretary-general of the National Council for Civil Liberties (NCCL, later named Liberty). Mind soon established a legal and welfare rights service.

Larry Gostin, co-author of this chapter, an American lawyer and recently a Fulbright Fellow at Oxford, was appointed first legal officer in 1975.19 Both Gostin and Smythe had worked in the domain of civil liberties in the United States. While legal director for Mind, Gostin wrote A Human Condition, essentially Mind’s proposals for reforming the Mental Health Act 1959.20

He stated:

The [1959] Act is largely founded upon the judgment of doctors; legal examination has ceased at the barrier of medical expertise, and the liberty of prospective patients is left exclusively under the control of medical judgments which have often been shown in the literature to lack reliability and validity.21

Gostin challenged the assumption that compulsory detention automatically allowed for compulsory treatment. He proposed that all treatment to be given to an inpatient who cannot, or does not, give consent should be reviewed by an independent body. He argued for the concept of the ‘least restrictive alternative’ (which in turn required the provision of a range of alternative services). He also proposed an extended advocacy system.

Gostin took cases to the courts, ranging from the right to vote and consent to treatment to freedom of communication. A particularly successful example was the 1981 case, X v The United Kingdom, before the European Court of Human Rights, resulting in a new power for MHRTs to discharge restricted forensic patients. While at Mind, he formed a volunteer lawyers panel to represent patients at MHRT hearings.

Gostin subsequently received the Rosemary Delbridge Memorial Award from the National Consumer Council for the person ‘who has most influenced Parliament and government to act for the welfare of society’.

The 1983 Mental Health Act thus marked a swing of the Act’s ‘pendulum’, not especially dramatic, towards ‘legalism’ (or called by Gostin, ‘new legalism’). It differed from Lunacy Act legalism by an accent on the rights of detained patients and their entitlements to mental health care, rather than ensuring that the sane were not mistakenly incarcerated as insane, or the detection of grossly irregular practices.

The newly established Mental Health Act Commission faced a daunting task. In addition to producing a Code of Practice, its oversight function involved up to 728 hospitals and units for mental illness and intellectual disabilities in England and Wales, together with 60 nursing homes which could come under its purview if they housed detained patients.

Mental Health Act 2007: An Amended Mental Health Act 1983

The next Mental Health Act followed thirty-four years later, in 2007.

The reduction in the number of mental health beds continued apace – England saw an 80 per cent reduction between 1959 and 2006. An argument grew in the 1980s that, as the locus of psychiatric treatment was increasingly in the community, so should be the option of involuntary treatment. Early moves in this direction were the ‘long leash’ – the creative use of ‘extended leave’ (ruled unlawful in 1985), the introduction of non-statutory Supervision Registers in 1994 and then the passing of the Mental Health (Patients in the Community) Act in 1995. This introduced Supervised Discharge, also known as ‘aftercare under supervision’. This could require a patient to reside at a specified place and to attend places for medical treatment or training. Administration of treatment could not be forced in the community but the patient could be conveyed to hospital, by force if necessary, for persuasion or admission.

The 1990s saw a new turn – a growing public anxiety that mental health services were failing to control patients, now in the community and no longer apparently safely detained in hospitals, who presented a risk, especially to others (see also Chapter 28). The 1983 Act was labelled obsolete – as, for example, in a highly publicised publication, the Falling Shadow report, following the investigation of a homicide by a mental patient.22

A ‘root and branch’ review of the Mental Health Act 1983 was initiated by the government in 1998. Its purpose, as announced by the then Secretary of State for Health, Frank Dobson, was ‘to ensure that patients who might otherwise be a danger to themselves and others are no longer allowed to refuse to comply with the treatment they need. We will also be changing the law to permit the detention of a small group of people who have not committed a crime but whose untreatable psychiatric disorder makes them dangerous.’

This led to what Rowena Daw, chair of the Mental Health Alliance, a coalition of more than seventy professional organisations and interest groups, called a seven-year ‘tortured history’ of ‘ideological warfare’ between the government and virtually all stakeholder groups.23 The Mental Health Alliance was a unique development. Created in 1999, it incorporated key organisations representing psychiatrists, service users, social workers, nurses, psychologists, lawyers, voluntary associations, charities, religious organisations, research bodies and carers (see also Chapter 28).

Initially, a government-appointed Expert Committee chaired by Professor Genevra Richardson produced generally well-received recommendations founded on the principles of non-discrimination towards people with a mental illness, respect for their autonomy and their right to care and treatment. An impaired ‘decision-making capacity’ criterion was proposed, only to be overridden in cases of a ‘substantial risk of serious harm to the health or safety of the patient or other persons’, and there are ‘positive clinical measures which are likely to prevent a deterioration or to secure an improvement in the patient’s mental condition’.

However, as Daw notes:

Government, on the other hand, had different priorities. It was driven by its wish to give flexibility in delivery of mental health services through compulsory treatment in the community; and its fear of ‘loopholes’ through which otherwise treatable patients might slip. In its general approach, the government followed a populist agenda fuelled by homicide inquiries into the deaths caused by mental health patients. Public concern and media frenzy went hand in hand to demand better public protection. … The then Health Minister Rosie Winterton MP stated that ‘every barrier that is put in the way of getting treatment to people with serious mental health problems puts both patients and public at risk’.24

A ‘torrid passage’ (Daw’s words) of Bills through parliament involved two rejections, in 2002 and 2004, and finally, in 2007, an amending Act to the 1983 Mental Health Act was passed.25

Fanning has detailed the role of the containment of ‘risk’ in the generation of the 2007 Act.26 He notes a swing back from ‘legalism’ to a new form of ‘medicalism’ – or ‘new medicalism’. He explains:

The 1959 Act’s medicalism … trusted mental health practitioners to take decisions for and on behalf of their patients according to clinical need. By contrast, the 2007 Act’s ‘New Medicalism’ expands practitioners’ discretion in order to enhance the mental health service’s responsiveness to risk. This subtle shift in focus introduces a covert political dimension to mental health decision-making … the 2007 Act’s brand of medicalism follows an inverted set of priorities to those pursued in the 1959 Act.27

Fanning examines a link to the characterisation of contemporary society, for example, by Beck and Giddens, as a ‘risk society’ – one preoccupied with anticipating and avoiding potentially catastrophic hazards that are a by-product of technological, scientific and cultural advances (see also Chapters 10 and 17). ‘Risk’ replaces ‘need’ as a core principle of social policy. It also leads to a culture of blame if adverse events should occur. Foucault’s notion of ‘governmentality’ also enters Fanning’s account – risk here offering an acceptable warrant for governmental disciplinary measures.

Another factor was the claim – disputed by a number of authorities – that risk assessment instruments had now achieved an acceptable degree of scientific precision as valid predictors of serious violent acts by persons with a mental disorder. The evidence is that risk assessment instruments for low frequency events, such as a homicide, result in a large preponderance of ‘false positives’ (see also Chapter 10).28

However, there is a problem with ‘risk’, Fanning argues. It is unclear what it really means. He claims:

Within reason, anything practitioners recast as evidence of a threat to the patient’s health or safety or to others is enough to justify the deployment of the compulsory powers … Consequently, it undermines legal certainty and impairs the law’s ability to defend patients’ interests.29

The 2007 Act increased professional discretion on the role of risk by:

simplifying and arguably broadening the definition of ‘mental disorder’;

abolishing the ‘treatability test’ for psychopathy, requiring only that treatment be ‘appropriate’ – previously the treatment had to be ‘likely’ to be effective, now that must be its ‘purpose’;

broadening the range of professionals able to engage the compulsory powers, by replacing the role of the ‘approved social worker’ with an ‘approved mental health professional’, who could be a psychologist, psychiatric nurse or occupational therapist. This reduced the separation of powers that existed between those with clinical and social perspectives; and

introducing Supervised Community Treatment (or Community Treatment Orders, CTOs), effectively strengthening supervision after discharge by the imposition of a broad range of conditions. A failure to comply with the treatment plan may result in recall to hospital; and if treatment cannot be reinstituted successfully within seventy-two hours, the CTO may be revoked with reinstatement of the inpatient compulsory order. The patient may appeal against the CTO but not the conditions.

The reforms represented a substantial shift away from a focus on individual rights and towards public protection. An exception was a strengthening of the need for consent for ECT in a patient with decision-making capacity (except where it is immediately necessary either to save the person’s life or to prevent a serious deterioration of their condition) and a right to advocacy (by an ‘Independent Mental Health Advocate’) for detained patients and those on a CTO.

Fanning goes on to claim that the ‘new medicalism’ maintains a ‘residual legalism’ in the amended Mental Health Act, which:

arguably has a sanitising effect by conferring a veneer of legitimacy on ‘sectioning’ processes which may now be less certain, less predictable and primarily motivated by concern for public safety … Far from being a minor statute which changes very little, the 2007 Act represents an entirely new moment in English mental health law and policy.30

At the same time as deliberations were in progress over reform to the Mental Health Act, parliament was passing the Mental Capacity Act 2005 in which the involuntary treatment of patients in general medicine and surgery was to be based on an entirely different set of principles – ‘decision-making capacity’ and ‘best interests’.

Post-2007 Developments

Two drivers of reform garnered significant support during the first decade of the twenty-first century. The first was the proposal for capacity-based law or a more radical version, known as a ‘fusion law’; the second was the adoption by the United Nations (UN) in 2006 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Both aim at the elimination of unfair discrimination against people with a mental disorder.

A ‘fusion law’ refers to a single, generic law applicable to all persons who have an impairment in the ability to make treatment decisions, whether the cause be a ‘mental disorder’ or a ‘physical disorder’.31 It combines the strengths of the Mental Capacity Act 2005 – that is, a respect for autonomy, self-determination and the right to refuse treatment, almost entirely absent in the Mental Health Act – with the detailed regulation of involuntary detention and treatment – its authorisation, by whom, where, for how long, review and appeal mechanisms, all well specified in conventional mental health legislation but absent from the Mental Capacity Act. Involuntary treatment is restricted to those who lack ‘decision-making capacity’ and where it is in the person’s ‘best interests’. Northern Ireland passed such an Act in 2016 following the path-breaking Bamford Report of 2007.

The UN CRPD presents a huge challenge to conventional psychiatric practice. A number of authorities, including the UN CRPD Committee established by the UN to oversee the convention, holds that any ‘substitute decision-making’ (except perhaps by a proxy appointed by the person with a disability, and who will respect the person’s ‘will and preferences’) is a violation of the CRPD. Thus, treatment against the objection of a patient is prohibited. It remains to be seen how the consequent debate with the many critics of this interpretation will play out.32

Scotland and Northern Ireland

Space permits only a brief account of the salient features of Scotland’s legislation. Until 2003, Scottish mental health law was by and large similar to that of England and Wales (though it did retain in its 1960 Mental Health Act an oversight body – the Mental Welfare Commission and a role in compulsory admissions for a Sheriff). However, the Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 marked a substantial departure:

the principle of autonomy is prominent;

it stipulates ten Guiding Principles (with no reference to risk or public safety);

patients must be treatable if compulsion is to be used;

while a criterion of risk to self or others is retained, an additional criterion must be met – a ‘clinically significant impairment of treatment decision-making ability’;

compulsory treatment orders, inpatient or in the community, must be authorised by a Mental Health Tribunal;

there is a right to independent advocacy;

there is a special recognition of advance statements – a failure to respect the person’s wishes needs written justification, which must be reported to the patient, a person named by the patient, a welfare attorney (if there is one) and the Mental Welfare Commission; and

there is a choice of a named person rather than the nearest relative.

Few would deny that this law is far more rights-based than that in England and Wales. As mentioned in the section ‘Post-2007 Developments’, Northern Ireland has taken reform even further, having passed a ‘fusion law’.

European Convention on Human Rights (Human Rights Act 1998)

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to give more than a brief reference to the influence on UK mental health law of the European Convention on Human Rights – later the Human Rights Act (1998). In 2007, Baroness Hale, then a member of the Appellate Committee of the House of Lords, summarised the impact as modest.33 An exception was the ‘Bournewood’ case concerning a man (HL) with autism who was admitted to a hospital as an informal patient, and although he did not, or could not, object, it was apparent that he would not be allowed to leave if he were to wish to do so. His carers, denied access to him, initiated a legal action that he was being detained unlawfully. This progressed with appeals through the English court system up to the House of Lords in 1998, who decided HL’s admission was lawful. His carers then took the case to the European Court of Human Rights, who, in 2004, ruled it was unlawful. This resulted in the Mental Health Act 2007 appending Schedules to the Mental Capacity Act establishing ‘Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards’ covering non-objecting hospital inpatients or care home residents who lacked decision-making capacity and, in their best interests, were not allowed to leave.34

Service User Movement

Similarly, limitations in scope only allow a brief consideration of the influence of service user organisations on changes in mental health law (see also Chapters 13 and 14). Service users had little direct involvement in the development of the 1983 Mental Health Act. While patient groups did form in the 1970s, the service user voice was not significantly heard until the mid-1980s.35 It was reasonably prominent in the debate leading to the 2007 Act, and the major service user organisations joined the Mental Health Alliance. Within or outwith the Alliance, however, their voice was largely ignored by government.

Conclusion

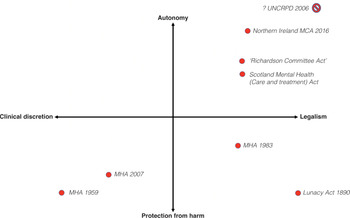

We have traced the course of mental health legislation from 1959 to 2010. The broad sweep of the changes can be summarised schematically, allowing for a degree of simplification. We have adapted the idea from Fanning of locating each law within a space created by two orthogonal dimensions (Figure 8.1).36 While Fanning finally did not support the schema, we propose that by reconceptualising the dimensions, it proves useful. The first dimension has at its poles ‘legalism’ versus ‘clinical discretion’ (or ‘medicalism’). The second has a ‘respect for autonomy’ (or emphasis on decision-making capacity’ and ‘consent to treatment’) versus ‘protection from harm’ (especially to others) dimension. The movements in this ‘legal–clinical–social’ space from the 1890 Act to the 1959 Act, then to the 1983 Act and the 2007 Act can be traced. The Richardson Committee’s 1999 recommendations and the 2003 Scotland Act are also shown, as are the major directions taken in the first decade of the twenty-first century – the Northern Ireland ‘fusion law’ as well as the UN CRPD Committee’s interpretation of the Convention (the claim that ‘substitute decision-making’ is to be abolished means that it is located at the top-right extreme or perhaps falls outside the space altogether).

It is pertinent to ask what has happened to the number of involuntary admissions over the period covered? In England, they declined steadily between 1966 and 1984, rose quite sharply and steadily until 2000 and then remained flat until 2010. The numbers then rose very sharply again (Figure 8.2). The contribution of changes in mental health legislation is difficult to determine. There were increases in involuntary admissions after both the 1983 and the 2007 Acts but other socio-political and administrative changes also occurred. Perhaps the most interesting observation is the stable rate between 2000 and 2008. This period was characterised by a substantial investment in community mental health services, suggesting that resources are a major determinant of the rate of involuntary admissions. Consistent with a resources contribution is the steep rise from 2009, a period of austerity.

Gostin observed that there is perhaps no other body of law which has undergone as many fundamental changes in approach and philosophy as mental health law.37 We have seen that such law reflects shifts – in Jones’s words, ‘good, bad or merely muddled’ – in social responses and values to an enduring and troubling set of human problems.38 We agree with Fennell that, while such laws often may not obviously greatly affect substantive outcomes, they are important, if for no other reason, than they require professionals – and we would add the state and civil society – to reflect on, explain and justify what is being done.39

Key Summary Points

The 1959 Mental Health Act represented, by any standard, a ‘paradigm shift’ in the way in which mental illness was construed, not just in Britain but anywhere. ‘Legalism’ of the 1890 Lunacy Act was replaced by ‘medicalism’.

While the general outline of the 1959 Act was preserved in the 1983 Mental Health Act, there was a significant swing of the ‘pendulum’ towards a new ‘legalism’.

Significant influences were the successes of the civil rights movement in the United States in the 1960s and 1970s that progressively asserted rights for groups subject to discrimination and the establishment of a legal and welfare rights service by the National Association for Mental Health (Mind).

An argument grew in the 1980s that, as the locus of psychiatric treatment was increasingly in the community, so should be the option of involuntary treatment. The Mental Health Act 2007 represented a substantial shift away from a focus on individual rights and towards public protection.

Two drivers of reform garnered significant support during the first decade of the twenty-first century. The first was the proposal for capacity-based law or a more radical version, known as a ‘fusion law’; the second was the adoption by the UN in 2006 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Both aim at the elimination of unfair discrimination against people with a mental disorder.

Changes in mental health law are traced within a space formed by two key dimensions: ‘clinical discretion’ versus ‘legalism and ‘autonomy’ versus ‘protection from harm’.

Introduction

This interview was carried out with Ken Clarke on 24 September 2019 at the House of Commons. It was transcribed and subsequently edited by Ken and this text is placed in italics. The remainder of the text is written by Peter Tyrer.

Early Background

Ken Clarke and I were at the same Cambridge College, Gonville and Caius College, between 1959 and 1962. In the first year, we were in adjacent blocks in Tree Court, a square that is now deprived of trees but still has marvellous wisterias on the walls. Our paths hardly ever crossed. Ken soon became very involved in university politics and I was too preoccupied in organising a botanical expedition to Central Africa. Ken was attracted to Labour at first – his grandfather was a Communist – but then quickly changed to another party whose nature all now know. He was offered his place at Caius before being offered an Exhibition at Oxford University, which he turned down as he felt they were too pompous. Some jokers have suggested this was the reason Ken never became prime minister, as eleven of the last fourteen occupants of the position went to Oxford. The last to be educated at Cambridge was Stanley Baldwin.

The only other point of note that struck me when Ken was at Cambridge was his accent. He came from Langley Mill, a village that is in the middle of D. H. Lawrence country. Although he won a scholarship to Nottingham High School, very eminent in the Midlands, he must have had a fair dose of the typical and not unpleasant local accent and would have understood that ‘silin’ dahn in Stabbo’ meant it was raining very hard in Stapleford (also near the Derbyshire border). He got on very well with the local miners, including those who had known D. H. Lawrence’s father. Ken’s father’s associates did not think much of D. H. Lawrence, who they felt had got above himself by going away and ‘writing mucky stories’, so this gives you an idea of Ken’s social milieu.

By the time he went to Cambridge, however, he was determined to become an MP and his accent had to change (remember this was 1959). He developed a Bertie Wooster-ish lad-di-dah accent with exaggerated rounded diphthongs, but this quickly changed into the voice everyone now knows. Ken is the only politician to be described as ‘blokeish’, a term impossible to define, but I think it really describes his voice. He doesn’t talk down to people in any way and, even when disagreeing strongly, he retains the ‘I’m just an ordinary chap trying to get my point over’ that never sounds offensive. Mrs Thatcher had to have elocution lessons but from his early time in politics Ken never needed them.

The main point of describing this background is to show Ken is not your ordinary politician. He achieved almost all the top positions of state – failing to be elected leader of the Conservative Party on three occasions – and could be regarded overall as highly successful, through dint of great intelligence and very hard work. He was constantly amazed at how lazy and ill-informed so many of his colleagues were.

Consistency

The other thing that is important to emphasise in understanding Ken Clarke is his consistency. It is often said that politicians have to bend in the wind or be toppled, but Ken was an exception. Once he had come to a view, he held on to it unless there was compelling evidence otherwise. The main reason I suspect why he was not elected leader of the Conservative Party was his belief that the UK should be an intrinsic part of the European Community. Unlike many other politicians who changed their views greatly over the years, Ken stuck to his opinion and, if anything, has stressed it even more strongly in these Brexit years.

In his personal life, he has been equally consistent. He was married to Gillian, whom he met as an undergraduate when at Caius, for more than fifty years. She died in 2015 from cancer, and one of her last acts was to vote for her husband in the 2015 General Election. She was an absolute rock to him, especially in his early political years when he commuted between Nottingham and London almost daily.

He is even consistent in his support of football teams. He supports both Notts County and Nottingham Forest and tries to see one of them every Saturday (they play at home alternately); he has kept loyal to both. Even though Notts County has drifted down the leagues and is in danger of going into liquidation, while Nottingham Forest soared to great heights in the 1970s and won the European Cup twice, he has stuck with both teams.

Good Humour and Unflappability

In his memoir, Kind of Blue,1 beautifully reflecting both his love of jazz and his semi-detached connection with the Conservative Party, Ken several times refers to the very true perception that ‘I was so laid back I was almost horizontal’. He is not wounded by criticism – his wife was and tried to defend him – but he regards it as useful ammunition for his rejoinders, which are often very witty. His negotiations with the British Medical Association (BMA) over a new contract and negotiations for an internal market involved the chairman, Anthony Grabham,2 and Ken used to point out his name repeatedly to illustrate that doctors were only interested in their wallets. Yet he also agreed that the BMA, in the end, had won the public relations battle over the new contract, and in my interview with him he conceded that the BMA was the union that he felt was more formidable than any other trade union because it could use the public as its main ally (see also Chapter 28).

Relevance of These Characteristics to Negotiations in Mental Health

I do not share the political views of Ken Clarke and it is equally possible to describe him as a highly intelligent but blinkered politician who has always seen the world through a kind of blue lens. Yet, in the interview, I conducted with him he was absolutely straight. ‘Go ahead, start your recording, ask me anything you want.’ I have to praise that in a politician. The changes he made to the transcript were very small, essentially typographical errors and improvement of clumsy expressions; and never once did he say ‘I’ve changed my mind over that now’ – consistency or stubbornness, you decide.

Ken was also highly regarded as a constituency MP. He represented the parliamentary constituency of Rushcliffe to the east of Nottingham for forty-nine years and improved the lot of his constituents greatly over that time. (I know, as I look over with envy from where I live in the adjacent constituency of Newark, which has been much less successful in gaining funding and new initiatives.) This constituency includes Saxondale Hospital, the former county mental hospital of Nottinghamshire, and Ken was aware of its assets and its failings. What he found most disturbing when Saxondale Hospital was destined to close was what he thought was sound evidence that some of the county dignitaries had managed to place their difficult and embarrassing relatives in the hospital for no good reason and that they had languished there for years.

My Interview

I was far from clear that I would be allowed to tape the interview with Ken when I saw him and only had a few notes jotted down. I was also limited by time. I saw him in Portcullis House, the new base for politicians opposite Big Ben, and he had to return to the House of Commons for a vote on the same evening. I apologise for any important omissions.

Q. Why did you introduce NHS Trusts?

One of the things I was concerned about when I became Secretary of State was to try and make the service much more accountable to its patients, and to stop it being so borne down by bureaucracy and dominated by industrial relations problems. The whole point of the purchaser/provider divide was to make sure what money was being spent on locally and to spend that money on the best outcomes for patients, the service and others in that locality. The service was for the locality, a strikingly novel idea that caused a lot of controversy. I had to reform the awful way in which the service was managed, with the responsibility diffusing out from the centre, not very effectively, saying how the service should be run in the rest of the country. We needed a better way of doing things. The idea of Trusts was to give more autonomy to the local users of services so they could answer for their performances to their local public.

I intended to pass responsibility downwards from oversized headquarters in London and secure accountability upwards so the general public could see where decisions were made. This led to some interesting battles over the next three years but it generally went well.

Q. Was there ever a real risk that the John Moore proposal to have an insurance-based replacement for the NHS was likely to happen?3

There definitely was. If John Moore had not become unwell, the proposal would have gone ahead as Margaret Thatcher and John were quite agreed that this was precisely what they were going to do. She was convinced the American system was much superior to our own, with a system of personal insurance and the state paying the insurance premiums for those who could not afford it. When I became Secretary of State I quickly became aware that I was expected to take over the implementation of this policy.

But I quickly came round to the view that this was quite unacceptable. Nigel Lawson helped me by resisting Margaret Thatcher’s urgings,4 that those who paid these premiums could get tax relief on their private health insurance contributions. It took me many long meetings to persuade her (Margaret did listen to argument) to abandon her scheme, returning to mine that at least had a degree of market-related responsibility with a purchaser/provider split making sure that there was some fiscal discipline.

Before the purchaser/provider discussions nobody really knew that the NHS was spending its money on, and the idea that the money given might be linked to the outcomes was never contemplated. One trouble was that patients did not belong to any trade unions so their views about what was needed were never heard.

I never pretended I was introducing the final model for the National Health Service. I was wanting to change direction by putting in a framework that could be developed in the future. To some extent this has been achieved but now Simon Stevens of NHS England has developed the idea of integrating hospital and community care diluting the purchaser/provider approach.5

Q. You mention in your memoirs that the BMA was the most difficult trade union you ever had to negotiate with. You were not very complimentary about the medical profession generally. Apart from Donald Acheson (then the Chief Medical Officer of Health), who you admired but who was not really part of the system, was there anyone in the BMA who you looked to for guidance and help?

Not really. Well the BMA was a trade union, even though at times they pretended not to be, with all sorts of high-minded statements for the general public, but basically, like all trade unions, they were always concerned about pay and conditions for their members. When I first arrived I was always advised I had to make concessions to the BMA. When I met Tony Grabham (muffled laughter about the significance of his surname) he tried to frighten me, telling me that all the previous Secretaries of State he had to deal with had all folded under the strain and that in the case of Barbara Castle he had reduced her to tears. But I wasn’t going to buckle under this even when they got nasty and went public with advertisements pillorying me.6

Q. Do you think doctors were treated too generously in the pay decisions of 2004?

Yes it was generous. And the government at the time, like almost all governments, was trying to buy popularity. Of course, as you know, the doctors have always been regarded as a special case. When Aneurin Bevan said you had to stuff their mouths with gold he set the scene for the future. When the new contracts set reduced hours for much of their work for more pay most were rather surprised as they were going to be paid more for doing less.

Q. Was the Conservative government involved in any way with the introduction of the Dangerous and Severe Personality Disorder Programme (DSPD) introduced by the Labour Government in 1999?

I have no recollection that at any time we were considering such a programme. I think you have to give the responsibility to the Labour government. The trouble is with policies like this is that you now have this semi-presidential system where everyone listens to advisers and so when public opinion gets sufficiently animated new policies are introduced without ever having been thought through.7

Q. What are your views about the Private Finance Initiatives (PFIs)?

We introduced the idea of Private Finance Initiatives in the 1992–7 government but very few took them on as the Labour Party said they would abolish them if they came to power. When of course they were elected they immediately started to introduce them. They have unfairly been given a very bad name. This is mainly because of the appalling incompetence of the people who negotiated these contracts, with payments that extended far beyond completion of the project. In the end they turned out to be more expensive than public financing. At the time there was this obsession over keeping to targets for the public finances. Gordon Brown was saying continuously in the first two to three years about how prudent he was going to be as Chancellor.8 But the government was not bothered about anything that was not on the books, so the PFIs were not down anywhere amongst the figures, so the government’s reputation for fiscal prudence could not be damaged in any way. My only explanation why the health authorities were allowed to go mad on PFI contracts was that the responsibility for the payments would pass on to a Minister appointed many years into the future.

Q. Can I give you the example of one Trust close to me, Sherwood Forest Hospitals Foundation Trust, where the final bill for the new hospital is going to be more than thirty times the value of the initial cost. How could this happen?’

The problem was that the Trust people had no experience of any kind to negotiate the cost of such complex deals, so the people from these private organisations who negotiated these deals could not believe their luck, and took them to the cleaners. So the argument was quite simple. ‘If you want your new hospital you can have it now. The payment for it will be made by someone else down the road, so don’t worry.’ So a sensible policy, well thought out and prudently applied at first, was quite discredited. Even in the early days when I was trying to get PFI going my approach was to say to each private financier that they could only get a return on their investment if they accepted a proportion of the risk.

The trouble was that the structure of these negotiations was quite unsuitable for the right contracts. People were appointed in the NHS with no experience, often on short-term contracts so they knew they would not have to pick up the flak down the line. So, in the Department of Health headquarters, we had some bright spark, hoping to make his way up the ladder, negotiating with British Oxygen’s finest, knowing absolutely nothing about the oxygen market. So, as you can imagine, the results were very satisfactory for British Oxygen.

Q. Do you think there is a political solution to the imbalance in the funding of the NHS where a large proportion of the funding is going to elderly people like you and me, just to give them a few extra years of life, not always ideal ones, when it should be going to younger people with their lives ahead of them, including a large proportion with mental health problems?

The reason why we have not been able to reverse this trend is that the people in the mental health system do not have a voice. I recognised this when I became Secretary of State and had to close down these Victorian institutions like Saxondale Hospital in my constituency, where people had been kept for years with no voice and no influence. These old ‘asylums’ were absolutely shocking places so it was perfectly sensible to introduce this policy of care in the community, provided it was integrated with hospital care by psychiatrists and others in a coherent way.

The trouble is that care in the community was extremely unpopular. People noticed that suddenly there were strange people out in the street loitering by traffic lights and felt that they ought to be locked away somewhere like Mapperley or Saxondale (if they were in Nottingham),9 and not being allowed to roam the streets.

The public believe that whenever there is extra money in the health service it ought to be spent on cancer patients or children, not on mental health, and populist Secretaries of State in populist governments accede to these requests, especially on cancer, a subject that terrifies the public so they feel if we spend more it might go away.

A more careful and balanced approach is possible but it does require a well-argued political defence. I separate that from the other problem you are touching on, which is the demographic one, the changing proportion of old and young people in society. The reason why there is an inexorable rising demand is the increasing age of the population that is creating a crisis in our health care system. We are going to have to find some way of meeting this demand. The burden of taxation is going to be spent increasingly on looking after the care of the elderly people and this is going to become unbalanced.

The big change is that so many people in their older years are going to need extra care. It is an extremely tricky political problem that has not been properly faced.

Q. But there has been an inter-Party group discussing this over some years. Is there any way in which this issue might be taken out of politics?

No, it can never be taken out of politics. The idea that it can be is quite wrong. Every time a bed-pan was dropped in South Wales there is a problem, which falls to the Secretary of State to deal with the consequences.

It will remain political while we have a totally free tax-paid health care system, even when it is linked to a social care system that is not comprehensively paid for at all by government.

Q. Should the NHS take over social care?

Well, we can’t afford it. It’s as simple as that. The debate about social care needs to be updated. It is perfectly obvious that if you provided the figures that would be necessary to pay for free care out of taxation it would be rejected out of hand. We need to introduce a more rational and fairer system. We need to come round to the idea that social care cannot be totally free and that we cannot avoid some financial burden. It may be possible to organise a national insurance system, but I’m not completely sure about that. We need to have something that takes account of the individual needs of patients and the responsibilities of society. The idea that somebody in a £2 m house should not be expected to pay for the costs of their care is ridiculous. Yet if this person did pay something, it should not mean that someone on a low income who has worked and struggled to pay for their needs over a working lifetime should also be required to pay. This would be clearly farcical.

The reason why we do not have a policy on social care is that no government has had the courage to produce one. Although there have been many attempts to resolve this all of them have proved to be deeply unpopular.

The trouble with our current populist system of government is that all decisions seem to be made by opinion polls. But opinion polls change, so they are no substitute for a properly organised policy. Anyone who suggests that social care should be paid for completely out of taxation would not be able to defend this at a time when there is rapidly increasing demand. So you then have to work out what means testing you are going to apply. A fairer, but not instantly unpopular solution for the twenty-first century, is to have some private insurance arrangements set up for social care.

We have to recognise where we are now. Both our education and health care systems are immeasurably better that when I was Secretary of State. Now we want someone with a well-thought-out plan for longer term reform, someone who can put their head down and not be worried about being unpopular. One of the big things about Margaret Thatcher was that she was not terribly interested in the reactions of the general public, she never looked at popular opinion, as she was a conviction politician.

There are two rules that need to be understood about reform. First, all change is resisted at first, and second, that anything that might cost more money is equally resisted. So you have to be aware of that from the beginning when you are making changes.

Q. Lastly, I want to turn to your time when you were at the Ministry of Justice when you were trying very hard to bring down the prison population. Why has this been so difficult when in other countries this aim has been more successful?

It is very disappointing. Even in America, in places where they have hard-line Republicans, they are beginning to reduce incarceration rates. We should be able to do better.

Q. In current forensic practice there are strong moves to improve the environments of people with significant mental health problems and to obtain early release, but there are many obstructions in the way. What can we do to help here?

There are good people in correctional institutions who recognise that getting people out of prison into good environments is the key to progress. There are far too many people in our prisons who are mentally ill and who require the proper treatment for their conditions. Of course this sometime requires secure accommodation. But we have to acknowledge that our current prisons do not allow adequate intervention for any of the mental health issues that they face.

At present we are having another of these populist drives to be tougher on law and order so we can bring more people into overcrowded institutions where it is almost impossible to do any worthwhile therapeutic work with them. There isn’t the space, there aren’t the personnel and almost all the effort is wasted. Currently we have Priti Patel who is waving this banner to be ‘tough on crime’.10 But it started long before her. Michael Howard, David Blunkett and others did quite a lot to raise the prison population dramatically.11 Priti is going to do her best to make her policy at the next general election a repeat of the old ‘hang ’em and flog ’em’ mantra. But there have been reactions against this. Michael Gove was on our side; 12 he had sensible solutions.

But, as for me, I have to say I failed to get a change in policy. I discussed it with David Cameron very frequently.13 He listened, but he was too nervous about the Daily Telegraph to do anything.

When we had the Thatcher government it was different. When we had good policies that we believed were right we implemented them. But we had to get the timing right. We knew they would be unpopular at first but over time they would be accepted, so we had to bring them in early. Nowadays parliaments seem to be much shorter. It is also different as Prime Ministers now employ ranks of public relations specialists who seem to make all the decisions.

Q. Is there a place for conviction politics nowadays?

Conclusion

The interview finished and Ken popped across to the House of Commons for one of his final debates. In the chaotic last weeks of the 2017–19 government, there was doubt as to who was running the country and one proposition put forward was that he, as Father of the House, might be prime minister for at least a week or so. It did not come to pass, but it would have been a fitting end to a career, which, despite the gloomy words of Enoch Powell that he maintained applied to all politicians, certainly did not end in failure.

Introduction

Over five decades, we have seen major changes in mental health policy for adults and for young people, often influenced by shifts in the broader social, political and economic environment. This chapter summarises some of the main changes, drivers and issues, including the introduction of care in the community and the emergence of new discourses around recovery, marketisation and risk during the period 1960–2010.

From Asylum to Community Care

The Mental Health Act 1959 was a step change from previous legislation in foregrounding the provision of treatment, rather than mere confinement, as the core purpose of mental health services. This reflected wider changes in services, with informal treatment becoming available not only for inpatients but also for those outside hospital (with 144,000 outpatient clinic attendances in 1959 compared to virtually none in 1930). However, mental health was still very much a ‘Cinderella service’, with Mental Health and Mental Deficiency Hospitals containing 40 per cent of NHS inpatient beds but receiving only 20 per cent of the hospital budget.1

With a populist’s ability to identify issues which chimed with the mood of the age, the Conservative health minister, Enoch Powell, saw the old Victorian asylums as being out of step with emerging expectations of a modern Britain. As well as being overcrowded and offering poor standards of care, their very architecture resonated as an uncomfortable symbol of a bygone age of Poor Law and Workhouse. In 1961, Powell captured this in his famous ‘Water Tower speech’ (for more details, see Chapters 1, 31).2 He also recognised the attitudes, customs and practices (both social and professional) which were embodied in these buildings – the ‘sheer inertia of mind and matter’ – that would need to be overcome if services were to be transformed.

This landmark speech was followed by A Hospital Plan for England and Wales, which proposed the development of small-scale psychiatric units in District General Hospitals, with local authorities providing a full range of community services.3 Much of this chimed with the aspirations of the more progressive elements within the mental health professions, who were keen to move out from the isolation (and perceived inferiority) of the old asylums and become part of mainstream health and social services provision. It suited both those with a more biological persuasion, with its emphasis on treatment rather than containment, and the emerging movement of social psychiatry with its emphasis on the social aspects of rehabilitation. However, despite the recognition of what was needed, and cross-party support for this agenda, financial pressures and institutional resistances continued to undermine any substantial implementation of community care. Although inpatient numbers were falling (from 160,000 in 1954 to 100,000 in 1974), there was inadequate investment in new community-based alternatives and concerns were starting to be expressed about the gap between rhetoric and reality.4

Recognising this, Barbara Castle, the Labour health minister, introduced the 1975 White Paper Better Services for the Mentally Ill.5 This made explicit the level of community-based NHS and local authority provision that should be provided per 100,000 population, assuming a roughly equal commitment by the NHS and local authorities, with the latter taking on the main responsibility for those requiring longer-term support and reintegration into mainstream community living. It stated that ‘joint planning of health and local authority services is essential’ and that ‘the policy can only be achieved if there is substantial capital investment in new facilities and if there is a significant shift in the balance of services between health and the local authority’.6 What was less explicit were the mechanisms whereby this joint planning would be achieved; how ‘bridge funding’ could be provided for investment in new facilities before old hospitals could be closed and savings made; and how resources could be transferred from the NHS to local authorities to provide social care. These concerns were amplified by the unfortunate timing of the White Paper, coinciding with economic adversity following the oil crisis of 1973.7

Nevertheless, government funding was made available to pilot the proposed model of service provision in Worcestershire in an experiment known as the Worcester Development Project.8 This allowed for comprehensive services to be established in the community without having to wait for any capital to be released and revenue saved from the closure of the old hospital. On the ground, progress was patchy, with teams in one part of the county moving quickly to relocate all their residents from the former asylum, while others were less committed to giving up previous ways of working – leading to a considerable delay in bringing about its final closure. Although GPs generally saw the new services as better for their patients, they also expressed concerns that they themselves were not properly trained for taking on a greater role in mental health.9

Although the intention was for this blueprint for a community service to be properly evaluated, this was not followed through. As a result, lessons were not learned as to what was actually needed, how much it would cost and how quickly the old hospitals could actually close – impeding further roll-out of the new service model. Whereas the Worcester Development Project had the benefit of bridging finance, this was not available elsewhere. Consequently, many people were discharged into lodgings or unsuitable accommodation with minimal support, arousing increasing public concern. During the hospital closure phase, more attention tended to be given to establishing psychiatric teams in new facilities in District General Hospitals than to integrating people back into mainstream community life. Crucially, there was no mechanism to transfer over funds to local authorities to create an appropriate infrastructure of community-based support.

A somewhat different story characterised developments in children’s services. Here, there had been an established model of Child Guidance Clinics, located within local authority education services and having a strong psychosocial ethos. However, separate NHS hospital-based psychiatric services for young people were also now being developed alongside new adult provision. Early debates in the 1960s were about how to better integrate these service arms – but with little success.10 Things came to a head (largely spurred on by all too familiar debates about a lack of adolescent inpatient beds and who should pay for what) in the 1986 report Bridges Over Troubled Waters.11 This resulted in the advent of an integrated Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS) that was no longer split between the NHS and local authorities. However, there remained a lack of clarity as to how this should operate in practice, with the first national guidelines not arriving until the mid-1990s – and CAMHS remained hampered by lack of substantive financial investment.

Rights and Recovery

Although the 1959 Mental Health Act had been welcomed as a great advance, by the late 1970s the government and other stakeholders were suggesting that a review would be timely. Led by their legal director, Lawrence O. Gostin, Mind ‘argued that many aspects of the treatment of those diagnosed as mental ill were an abuse or denial of their rights’.12 Although the 1983 Mental Health Act retained much of the overall structure of the 1959 Act, a series of stronger safeguards were built in to enshrine the principle of the ‘least restrictive alternative’, including greater independence (and training) for Approved Social Workers; stronger (and quicker) rights of appeal for detained patients; and greater use of second medical opinions in relation to more controversial treatments such as psychosurgery and electroconvulsive therapy. Notably absent from the debates leading up to the new Act was any public or political concern as to the inherent dangerousness of people with mental health difficulties and hence any paramount necessity to protect the public against such people.

A little later in the decade, a new discourse emerged around the rights of young people to protection – which was reflected in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child and the 1989 Children Act. This increased awareness of the need for more specific services to support children and young people with their mental health and well-being.13 However, while this had more tangible impacts on local authority children’s services (as in the provision of guardians ad litem to represent children’s interests in court), it was less influential in relation to mental health where, for example, young people could still be sectioned and sent to adult psychiatric wards without any specific safeguards being put in place.

Linking in with wider movements around disability activism, people with lived experience of mental distress (often describing themselves as ‘survivors’ of the mental health system) started to assert their own voice through campaigning organisations such as Survivors Speak Out and the UK Advocacy Network and, to an increasing extent, voluntary organisations such as Mind. Particularly influential was the movement in the 1990s to claim and redefine the term ‘recovery’.14 Activists such as Pat Deegan in the United States and Ron Coleman in the UK promoted the idea of recovery as reclaiming a life worth living – where it would be for the person (and not professionals) to define what that life would look like. It offered a paradigm shift towards a more co-productive approach to practice – one that did not always sit easily with some of the established attitudes and practices of mental health professionals in its emphasis on areas such as empowerment, peer support and social inclusion.15

This user voice and the idea of recovery were influential in the development of the National Service Framework – although perhaps not as influential as many would have liked. Instead, it was articulated in documents that were less central to policy implementation: The Journey to Recovery: The Government’s Vision for Mental Health Care and A Common Purpose: Recovery in Future Mental Health Services (the latter in collaboration with the Royal College of Psychiatrists).16 Rather than transforming the mainstream of service provision, its influence tended to be in more circumscribed developments, such as the emergence of Recovery Colleges. Concerns started to be expressed that the idea of ‘recovery’ had lost its radical edge and had been appropriated by professional interests to support their agendas – for example, as a pretext for withdrawing services.17 This marginalisation of user-defined recovery reflected a deep ambivalence within the system as to how (and whether) to move beyond rhetoric and situate people not as patients to be cured but as collaborators in their own recovery journeys.

Marketisation

This focus on rights was soon to be overtaken by a newly emerging discourse about management and efficiency in the delivery of public services – which came to dominate the policy agenda during Margaret Thatcher’s premiership. Driven by the ideologies of neoliberalism and New Public Management that were taking hold in the United States, the priority was to make public services more efficient and ‘business-like’ using market mechanisms. A key proposal, based on the ideas of an American economist, Alain Enthoven, was that responsibility for purchasing care and providing services should be separated (the purchaser/provider split). NHS services would be bought from self-governing NHS Trusts which, in theory, would compete with one another, thereby encouraging greater responsiveness and cost-efficiency. A parallel (but different) marketisation of social care was introduced in the NHS and Community Care Act 1990, with local authorities as lead purchasers and the bulk of provision contracted out to the voluntary/private sectors (see also Chapter 3).

For mental health services, this fragmentation within and between different parts of the health and social care system simply exacerbated existing difficulties in ensuring strategic and operational collaboration. Partnership working was, in effect, part of government rhetoric rather than a practical possibility.18 With no mechanism in place for enabling (or ring-fencing) a shift of funding from hospital beds to community care, many local authorities saw an opportunity, at a time of financial pressure, to cut back or abdicate many of their responsibilities in relation to mental health – apart from the statutory duty of providing Approved Practitioners to assess people under the Mental Health Act.

By contrast, relatively unaffected by marketisation, a more coherent approach was being taken forward in CAMHS. In Together We Stand,19 a tiered model was proposed in which different levels of support and expertise were available in response to different levels of need. This was well received and described as a policy that ‘captured the imagination of all and triggered a clear commitment to improve services’.20 However, an unintended consequence was to compound existing problems around transitions (as most areas continued to only see children up to the age of sixteen, with adult services starting from the age of eighteen) – with no provision at all in some areas for sixteen-to-eighteen-year-olds who were either too old or too young for services.21

Risk and Public Safety