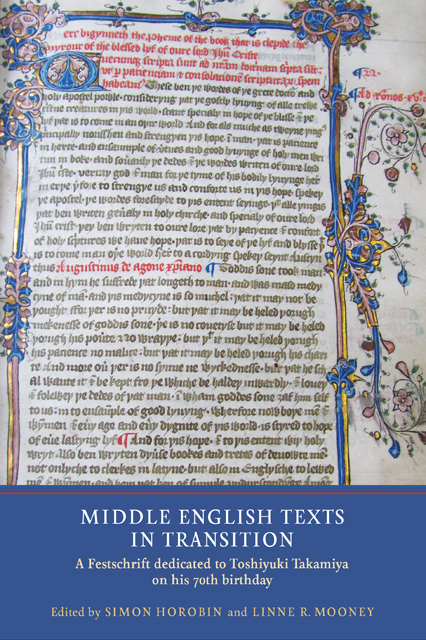

Middle English Texts in Transition

Middle English Texts in Transition Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 March 2023

In an article that has received a considerable amount of attention, Linne Mooney links the professional legal scrivener Adam Pinkhurst, whose autograph appears in the earliest official record of the London Scriveners’ Guild, with the scribe memorably pilloried by Geoffrey Chaucer in an acerbic little verse:

Adam scriveyn, if ever it thee bifalle

Boece or Troylus for to wryten newe,

Under thy long lokkes thou most have the scalle,

But after my makyng thow wryte more trewe;

So ofte adaye I mot thy werk renewe,

It to correcte and eke to rubbe and scrape,

And al is thorugh thy negligence and rape.

This paper will attempt to answer two simple questions: when did Adam Pinkhurst subscribe his name to the Scriveners’ official record, and why was he required to do so? It will have nothing substantive to say on the question of whether Adam Pinkhurst is to be identified with the Adam Scriveyn of Chaucer’s squib, though it may help to fill in some of the historical background on that issue. The wider aim of the paper is to provide a fuller history of the early years of the Scriveners’ Company (properly, at this date, called the Craft of Writers of Court Letter) than has been available hitherto.

Two obstacles stand in the way of anyone seeking to write a history of the origins of the Scriveners’ guild. The first is the extremely shabby state of the official guild record book, the Scriveners’ Company Common Paper. For a profession that made its living by its pen, the scriveners were remarkably inept at keeping their own records in order. The Common Paper has been re-bound more than once and, according to a note tipped into the back by Sir Hilary Jenkinson at the time of its repair by the Public Record Office in 1924/5, its original first gathering included not simply its opening pages (pp. 1–8), but pp. 53–66 as well; other fourteenth- and fifteenth-century entries are scattered throughout the volume (for instance, on pp. 67–91, 222, 281–2 and 296). The PRO did a thoroughly professional job and the volume is now solid, if very far from elegant. The second obstacle is Francis W. Steer’s calendar and partial translation (I use the word advisedly) of this Common Paper, undertaken for the London Record Society in 1968.

To save this book to your Kindle, first ensure [email protected] is added to your Approved Personal Document E-mail List under your Personal Document Settings on the Manage Your Content and Devices page of your Amazon account. Then enter the ‘name’ part of your Kindle email address below. Find out more about saving to your Kindle.

Note you can select to save to either the @free.kindle.com or @kindle.com variations. ‘@free.kindle.com’ emails are free but can only be saved to your device when it is connected to wi-fi. ‘@kindle.com’ emails can be delivered even when you are not connected to wi-fi, but note that service fees apply.

Find out more about the Kindle Personal Document Service.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Dropbox.

To save content items to your account, please confirm that you agree to abide by our usage policies. If this is the first time you use this feature, you will be asked to authorise Cambridge Core to connect with your account. Find out more about saving content to Google Drive.