The Medieval Gift and the Classical Tradition

The Medieval Gift and the Classical Tradition Book contents

- The Medieval Gift and the Classical Tradition

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought Fourth Series

- The Medieval Gift and the Classical Tradition

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 The Gift in Classical Literature

- Chapter 3 De Beneficiis in Medieval Contexts

- Chapter 4 Writing Generosity

- Chapter 5 Sanctifying Generosity

- Chapter 6 Romancing Generosity

- Chapter 7 Performing Generosity

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

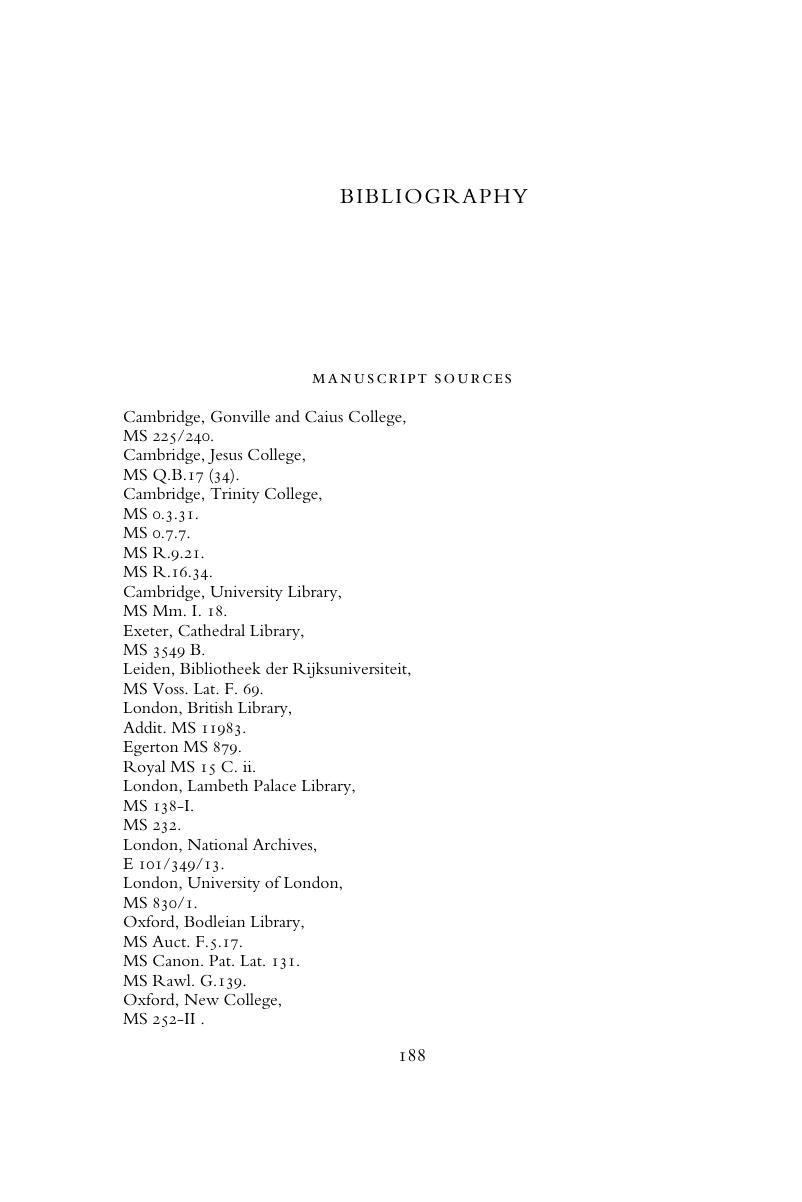

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 August 2019

- The Medieval Gift and the Classical Tradition

- Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought Fourth Series

- The Medieval Gift and the Classical Tradition

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 The Gift in Classical Literature

- Chapter 3 De Beneficiis in Medieval Contexts

- Chapter 4 Writing Generosity

- Chapter 5 Sanctifying Generosity

- Chapter 6 Romancing Generosity

- Chapter 7 Performing Generosity

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Medieval Gift and the Classical TraditionIdeals and the Performance of Generosity in Medieval England, 1100–1300, pp. 188 - 216Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019