The permanent move of members of the Ottoman dynasty to the harem at the New Palace in the sixteenth century gradually transformed the imperial harem (Harem-i Hümâyun) into a well-organized, hierarchical, and institutionalized structure with rigid protocols and training, similar to that found in the Enderun. Indeed, the Harem-i Hümâyun was also called Enderun-ı Hümâyun in some sources.Footnote 1 In the eighteenth century, the general organization of the imperial harem was more or less the same as it had been in previous centuries. Even so, tracing the evolution of the imperial harem from the sixteenth century onward shows that, despite its institutional continuity, its organizational structure was never static. At different periods, the number of women living in the harem changed, and the importance attributed to various hierarchical positions within it could increase or diminish over time. Just as the Enderun experienced change in its organizational structure over time,Footnote 2 so too did the imperial harem evolve in terms of its physical and organizational structure.

The present chapter reconstructs the structure of the imperial harem and the relationships within it, with a central focus on its residents. This task is important, for it is only by understanding the web of hierarchies within the harem that one can trace women’s relationships with the imperial court during their harem service and following their transfer from the palace. The chapter identifies the residents of the harem through an analysis of their origins, families, names, occupations, and salaries, based on extensive research into the range of sources noted above. The available sources enable to construct both women’s positions in the harem organization and the size of the harem population in the eighteenth century. The final section of this chapter evaluates the role of patronage relations within the broader network of relationships in the imperial harem. The long-lasting relationship between the imperial court and female palace slaves was rooted in the harem, and residents of the harem were attached to the household through various layers of patronage relationships.

Residents of the Imperial Harem

Tayinat (allowance), masraf-ı şehriyârî (royal expenditures), mevâcib (stipend), inamat (gifts), and mübayaa (purchase) registers are valuable sources that provide information about the structure of and residents in the imperial harem.Footnote 3 Although these registers generally do not allow us to establish the exact numbers, positions, or names of all harem residents, some rare mevâcib registers do enable us to count the harem population at particular moments of time, to tease out the names of individual harem members together with their occupations and assigned salaries, and to know who possessed how many slaves in the harem.Footnote 4

From the last quarter of the sixteenth century, the imperial harem’s population at the New Palace gradually increased in connection with many developments realized in this period. Leslie Peirce provides a detailed analysis of the changing harem population for the period from the mid-sixteenth century to the mid-seventeenth century. According to Peirce, the harem’s population at Selim II’s death in 1574 was forty-nine. During the subsequent reign of Murad III, it increased to 104, and then continued to grow during each successive reign. During the reign of Mehmed III, the harem population was 275; it rose to 295 in 1622, to 433 in 1633, and to 436 in 1652.Footnote 5 Some European accounts provide information about the size of the imperial harem for this period, although their estimates of female members varied and were sometimes exaggerated. In 1573, for example, Costantino Garzoni reported that 150 women were living in the New Palace and in the Old Palace there were 1,500.Footnote 6 According to Domenico Hierosolimitano, more than 800 women were fed regularly in the Seraglio.Footnote 7 Ottaviano Bon, the Venetian bailo to Istanbul between 1604 and 1607, and Bobovius, who was a page in the Enderun in the seventeenth century, both claimed that the number of female slaves in the palace was between 1,100 and 1,200.Footnote 8

The number of female palace slaves also changed during each sultan’s reign. According to the mevâcib register from the period of Mahmud I (r. 1730–1754), there were 446 female slaves in the imperial harem.Footnote 9 A mevâcib register from the period of Selim III (r. 1789–1807) shows that the number of female slaves in the imperial harem was around 720.Footnote 10 By contrast, a mevâcib register from the period of Mahmud II (r. 1808–1839) lists only 473 female slaves in the imperial harem.Footnote 11 D’Ohsson, who lived in the second half of the eighteenth century, stated that the imperial harem was composed of 500–600 female slaves.Footnote 12 Likewise according to Melling’s account, some 500 women populated the harem.Footnote 13

The sources examined for this study reveal that during the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth centuries, the imperial harem’s organization remained much as it had been during the seventeenth century. The Ottoman imperial harem had a hierarchically organized structure that encompassed various female slaves of different status. The harem’s female slaves can be broadly categorized into two groups: the first comprised women who were directly linked to the sultan as consorts (kadın and ikbal), while the second included those who worked in the service of the sultan and the dynastic family, as well as those who served in various sections of the harem. Inexperienced female slaves who newly entered the imperial palace were called acemi (novice), and their early period of service was known as acemilik (novitiate). In time, the acemis attained the various ranks. D’Ohsson noted that female slaves in the harem were actually composed of five separate groups, namely “cariye (female slave), şakird (apprentice), usta (mistress), gedikli (who waited on the sultan in person), kadın.”Footnote 14 The basis on which these women were promoted is not yet as clear as it was for the men in the Enderun.Footnote 15

Consorts of the Sultans, Wet Nurse (Daye Kadın), and the Chief Administrative Officer (Kethüda Kadın)

Female members of the sultan’s family who lived in the imperial harem consisted of the sultan’s mother (valide sultan), his unmarried daughters, and his consorts. The valide sultan was the most important and powerful member of the dynastic family, and as such she constituted the chief authority over the harem. Senior and experienced slave women served in her entourage.Footnote 16 Until the beginning of the sixteenth century, the sultans’ consorts included both married legal wives and slave concubines. From this period on, however, imperial marriages with the daughters of Christian dynasties and of the Anatolian emirates fell into disfavor. Instead, the Ottomans normally adopted the practice of maintaining slave concubines rather than marrying legal wives, although a few rare sultans continued to marry.Footnote 17

As the archival sources reflect, the sultan’s favorite consort in the sixteenth through seventeenth centuries was named haseki. Even as late as the period of Mustafa II (r. 1695–1703), the title haseki was used.Footnote 18 By the eighteenth century, though, the title haseki no longer appears in the records, seemingly haven fallen out of official use and replaced by the title kadın. The consorts were not limited in number, although they were ranked by their status: the highest-ranking consort bore the title senior/head consort (baş kadın), followed by second consort (ikinci kadın), third consort (üçüncü kadın), fourth consort (dördüncü kadın), and so on. Promotion was possible among the consorts over time.

Below the consort (kadın) ranked a lower level of concubine who bore the title ikbal (favorite, fortunate one). Like the consorts, these concubines were ordered by seniority, as senior ikbal, second ikbal, third ikbal, fourth ikbal, etc. The available sources reveal that Mustafa II, Mahmud I, and Mustafa III each had ikbals.Footnote 19

In the imperial harem, not only sultan but also each other member of the dynastic family, including the sultan’s mother, sons, daughters, and the consorts as well, possessed their own cadre of female slaves assigned to their personal service. During the reign of Mahmud I (r. 1730–1754), twenty female slaves were assigned to the service of the head consort, while another five consorts had various numbers of female slaves in their service, ranging from eight to thirteen.Footnote 20 The head consort and other high-ranked consorts also enjoyed the service of an agha (palace officer) and personnel responsible for the coffee service (kahvecibaşı).Footnote 21 In the period of Mahmud II (r. 1808–1839), consorts were served by between three and thirteen female slaves, again in accordance with their status.Footnote 22 The number of female slaves assigned to the service of senior ikbal and other ikbals of Mahmud I ranged from four to six.Footnote 23

In both of these periods, the sultan’s sons and daughters typically had more female slaves than most of the consorts. For instance, in the period of Mahmud I, the number of slaves in the princes’ service ranged from seven to nineteen; during the reign of Mahmud II, the numbers were slightly lower. In the latter period, female slaves serving the sultan’s daughters ranged in number from five to fourteen.Footnote 24

*

Another woman who held great influence within the imperial harem in every period was the sultan’s wet nurse.Footnote 25 She had a prestigious position, recognized through the honorific title “respectable” (izzetli) that was attributed to her.Footnote 26 In some cases, young wet nurses for the sultan’s children were admitted to the imperial harem together with their own daughters. In fact, the mevacib list belonging to the period of Mahmud II reveals that a wet nurse’s daughter (daye kızı) appeared in the service of both prince Abdulmecid and Mihrimah sultan (one of the sultan’s daughters), earning a personal salary.Footnote 27

The high status position held by the wet nurses was also reflected in their allowances. In the registers of the imperial harem’s food allocations (tayinat), only the sultan’s family members, the chief administrative official (kethüda kadın), and the wet nurse are listed individually. The remaining harem residents are listed as an undifferentiated single group. To give but one example from a large number of possibilities, a food allocation (me’kûlât) register from the period of Mehmed IV, dated 1643, shows the wet nurse being allocated the almost same amount of food as the sultan’s mother.Footnote 28 According to an expenditure register delineating purchases and disbursements for privy purposes (harc-ı hassa) from the period of Mustafa II, the wet nurse received a higher allowance than the head consort or any of the other consorts.Footnote 29 As will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 3, wet nurses were usually married to a high-ranking state official, in accordance with their status.

*

The chief administrative officer (kethüda kadın) acted as the superintendent of the imperial harem, and as a result had an influential and prestigious position.Footnote 30 The honorific titles attributed to her, such as prosperous, virtuous, respectable (saadetli, iffetli, izzetli), reflected her status in the harem.Footnote 31 In the archival registers, while the large number of female palace slaves are mentioned as a single group, the chief administrative officer is always listed individually. Ottoman chroniclers have left us with information concerning the duties and importance of this chief administrative officer. Historian Silâhdar informs us that following the death of Hadice Turhan Valide Sultan, mother of Mehmed IV, in 1683, the chief administrative officer became responsible for taking delivery of her possessions, for maintaining the order of the harem, and for guarding the princes.Footnote 32 Likewise, her predecessor, Kösem Valide Sultan (d. 1651), instructed the chief black eunuchs that whenever an important issue took place they should inform the chief administrative officer to ensure their access to the sultan’s mother.Footnote 33

European accounts frequently emphasized the role and status of the chief administrative officer. Generally, she was referred to as kahya kadın, and reportedly she had a privileged position in the imperial harem, being its governess and lady matron to all the women.Footnote 34 She examined all the girls who were brought to the palace and ensured their adherence to the harem’s rules and orders.Footnote 35 According to European accounts, kahya kadın also took care of the women who were destined to become the sultan’s consorts.Footnote 36 D’Ohsson noted that the kethüda kadın was selected by the sultan from among the most experienced women and from the ranks of gediklis.Footnote 37 He added that as a sign of her high status, the kethüda kadın carried a cane and an imperial seal.Footnote 38

The chief administrative officer’s privileged position can also be seen in the network of gift exchange that existed within the imperial court. For instance, during a birth ceremony that took place during the reign of Ahmed III, the chief administrative officer received gifts alongside the sultan’s mother, his daughters, his consorts, and the wet nurse.Footnote 39 The mevâcib registers likewise point to the chief administrative officer’s high status and prestigious position. According to a register from the period of Selim III (r. 1789–1807), the chief administrative officer received 500 akçe daily, more than the sultan’s mother, who received 400 akçe.Footnote 40 During the reign of Mahmud II (r. 1808–1839), the chief administrative officer continued to receive 500 akçe, while the sultan’s children received only 100 akçe each; the head consort and other six consorts received much less, only 40 akçe per day.Footnote 41 D’Ohsson noted that since 1689, the chief administrative officers had enjoyed a large pension of 7,500 piastres per year, granted to them by Süleyman II.Footnote 42

Like members of the dynasty, the chief administrative officer had her own suite, in accordance with her status. She had an eunuch agha,Footnote 43 personnel responsible for providing the coffee service,Footnote 44 and female slaves in her personal service. In the period of Mahmud I, she had four female slaves; during the reign of Mahmud II, this was increased to five. Her slaves, in turn, were ranked, and their daily stipend ranged from five to forty akçe.Footnote 45

Like the wet nurse, the privileged position of the chief administrative officer in the harem hierarchy was also reflected in the amount of food assigned to her. According to the sources, the chief administrative officer always received less food than the chief black eunuch, but higher amounts than the princes and sometimes even the sultan’s consorts.Footnote 46

Gedikli- Usta- Şakird- Cariye

Gedikli was below the rank of kadın. The gediklis were girls destined for the sultan’s personal service. These women had similar employment to that of the officers of the privy chamber (has oda), and they carried the titles of their offices. For instance, the person who was responsible for table service was called çaşnigir usta (mistress of the table service). The woman who was in charge of laundry service was, likewise, named cameşuy usta (mistress of the laundry service). In the suite of each gedikli, there were female slaves who helped her and were trained at the same time. When his kadın died or was sent to the Old Palace, the sultan chose her replacement from among these girls. Those who were most distinguished would receive the title of ikbal, ranked below the kadın but in line for eventual promotion to the rank of kadın.Footnote 47

Ustas performed the same personal service for the sultan’s mother, consorts, and children as the gediklis performed for the sultan. Ustas also had their own entourage of female slaves. Each usta was known by the work assigned to her and also by the name of the person she served.Footnote 48 Therefore, one finds in the records the sultan’s mother’s cameşuy usta, or Ayşe Sultan’s kahveci usta (the mistress of the coffee service), etc.

According to the archival sources, the following ustas lived in the imperial harem: hazînedar usta (head treasurer), saray ustası (mistress of the palace),Footnote 49 deputy mistress (vekil usta), cameşuy usta (mistress of the laundry service),Footnote 50 çaşnigir usta (mistress of the table service), ibrikdar usta (mistress of the ewer service), kahveci usta (mistress of the coffee service), kilerci usta (mistress of the pantry), berber usta (mistress of the hairdressing service), kutucu usta (mistress of toilette services),Footnote 51 külhancı usta (mistress of the bath service)Footnote 52, and kâtibe usta (head scribe). Each usta also had a main assistant. D’Ohsson defined the head treasurer as the assistant to the chief administrative officer and defined her duties as being in charge of the sultan’s clothes and the harem’s finance, as well as accompanying the palace women when they were outside.Footnote 53 The head treasurer was followed by second treasurer (ikinci hazînedar), the third treasurer (üçüncü hazînedar), and sometimes a fourth treasurer (dördüncü hazînedar) and fifth treasurer (beşinci hazînedar).Footnote 54 The reputable position of treasurers was reflected in the number of female slaves assigned to their service. During the reign of Mahmud I, the second treasurer had three female slaves to herself.Footnote 55 In the period of Mahmud II, the head treasurer had two female slaves, one of whom was called the head female slave. The second and third treasurer each had one female slave.Footnote 56

In the eighteenth century, some head treasurers held an even more special place in the harem’s hierarchy. For instance, Nevres Kadın, who was the third consort of Abdulhamid I, was the head treasurer, as was the sixth consort of Mahmud I. In the latter case, she had thirteen female slaves in her service, more than the number serving the sultan’s fourth and fifth consorts.Footnote 57 In the period of Abdulhamid I, the head treasurer received a greater amount of food than even the chief administrative officer and the second consort.Footnote 58 The allowances assigned to ustas also reflected their relative positions in the imperial harem. For instance, during the reign of Mahmud I, the daily stipends assigned to ustas were higher than the amount given to the sultan’s ikbals.Footnote 59 According to the mevâcib register from the period of Mahmud II, stipends allocated to ustas exceeded those assigned to the consort and sultan’s children.Footnote 60 During the reigns of both Mahmud I and Mahmud II, each usta usually had one female slave in her service. The sources suggest that the ustas’ hierarchical status remained relatively uniform across the eighteenth century, in terms of their stipends and the number of female slaves working for them, although there were some minor variations.

Figure 1.2 “An attendant of the Harem of the Grand Signior.” Octavian Dalvimart, The Costume of Turkey (London: William Miller, 1804).

A lower category of women serving in the harem was the kalfa. Kalfa was a rank below that of usta.Footnote 61 The entourages of the imperial family included kalfas. Among the female slaves given to the service of the sultan’s children, for example, were nannies and wet nurses who carryied the title kalfa (daye kalfa- dadı kalfa).Footnote 62 Some of the sultan’s ikbals were also called kalfa: four ikbals of Mahmud I were Miyase Kalfa, Fehmi Kalfa, Sırrı Kalfa, and Habbabe Kalfa.Footnote 63 Senior kalfas were also responsible for training the novices. Finally, according to D’Ohsson, the term şakird (apprentice) referred to those who were trained to fill vacant places among the gediklis and ustas.Footnote 64

*

Apart from these specialized categories of women, the largest group within the imperial harem was the female slaves (cariyes) who performed various services.Footnote 65 Cariyes were the lowest-ranking members of a particular individual’s suite and they performed the harem’s ordinary menial tasks, such as cleaning, laundry, maintaining the baths and pantry, and other similar tasks.Footnote 66

Apart from sultan’s family (which included his consorts), the ustas, and the kalfas, palace aghas also owned female slaves. The chief black eunuch had four female slaves, in addition to the head female slave called ağa ustası;Footnote 67 after the members of the imperial dynasty and highest-ranking members of the harem, this was the largest number of female slaves in one person’s service. According to D’Ohsson’s account, the chief black eunuch was the only palace officer who was allowed to have slave girls serving him.Footnote 68 However, the records show that the agha of the treasury (hazînedar ağa), the servant of the chamber (oda lalası), the chief door keeper (baş kapı gulamı ağa), and the favorite (musâhib ağa) also had female slaves in their personel service.Footnote 69 Female slaves were likewise assigned to the service of dethroned sultans.Footnote 70

During the eighteenth century and in the reign of Mahmud II, the imperial harem’s structure remained largely as it had existed in the seventeenth century, although there were some minor changes. For instance, while there were influential figures known as musâhibe (companion) in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,Footnote 71 references to this position do not appear in the eighteenth-century sources. Likewise, during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and into the reigns of Mustafa II (r. 1695–1703) and Ahmed III (r. 1703–1730), there were women in the imperial harem called bula.Footnote 72 However, the term bula did not appear in the examined sources from the rest of the eighteenth century. In the imperial harem, the importance and definition of certain positions and titles thus changed over time, just as they did in the Enderun.Footnote 73

A Female Slave’s Entrance to the Imperial Harem

Female palace slaves were taken into the imperial harem in a number of different ways. Unfortunately, from the existing records it is not possible to determine in what ways each individual female slave arrived. However, as in the previous centuries, female slaves of the eighteenth century entered the service of the imperial harem either as gifts, through purchase, or as war captives.

Captive girls were presented to the palace in every period of the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 74 Gülnuş Sultan, mother of Mustafa II (r. 1695–1703) and Ahmed III (r. 1703–1715), for example, was born in the 1640s in Rethymno, Crete, which was at that point under Venetian rule. Led by Deli Hüseyin Pasha, the Ottoman army seized part of the island during the Crete War (1645–1669); the girl was then enslaved and sent to the palace.Footnote 75 According to Rycaut’s account, during a campaign in 1697, Mustafa II wrote a letter to his mother stating that he would send her a present of young ladies from the region of Transylvania.Footnote 76 The admission of captive girls into the imperial harem continued during the eighteenth century.Footnote 77

Other female slaves entered the imperial harem as gifts from foreign rulers, local statesmen, and even between members of the Ottoman dynasty.Footnote 78 A person named Hamza Efendi presented Sanavber Hatun to Mustafa I, for example; later in the eighteenth century, when the ruler of the Güril did not submit his poll tax for several years, eight male slaves (gulâm) and four female slaves who had been sent as presents with the Georgian envoy were then sold in the bazaar to cover the poll tax debts.Footnote 79 The Crimean Khans sent female slaves,Footnote 80 while female members of the dynasty and statesmen of various statuses likewise presented female slaves as gifts to the sultan on different occasions. Mustafa II’s consort Hafife had been presented to the palace by Şirvanî Kara Ebubekir Efendi when she was ten years old.Footnote 81 The eighteenth-century chronicler Şem’dânî-zâde likewise recorded that some female slaves were admitted to the imperial palace as presents, while European authors noted that girls in the imperial harem were presented as gifts from members of the imperial family, grand dignitaries, and provincial governors. It was also stated that Tatars presented young virgins to the sultan.Footnote 82

Upon a sultan’s enthronement, gifts from statesmen played an important role in the making of a new cadre within the harem. Aubry de la Motraye noted that Ahmed III had received one hundred Circassian virgin slaves as presents following his accession to the throne.Footnote 83 Dallaway also noted that when the sultan came to the throne, the grandees presented him with virgin slaves who, they hoped, would become their patronesses.Footnote 84 As will be seen in Chapter 2, the enthronement of a new sultan could result in some female slaves in the previous sultan’s harem being manumitted; as a result, the harem itself was regularly being renewed. Statesmen’s goal of presenting new female slaves was to assist with dynastic reproduction. For instance, following the enthronement of Sultan Ibrahim in 1640, statesmen sent female slaves in order to ensure the continuity of the dynasty.Footnote 85

Female slaves were also presented during the wedding ceremonies of the dynastic family. At the wedding of Mehmed IV’s daughter Hadice Sultan in 1675, the groom offered female slaves to the sultan’s mother, to his wives, and to Princes Mustafa and Ahmed.Footnote 86 For the wedding between Mustafa II’s daughters and viziers, the pashas of Bosnia, Erzurum, and Meskhetia sent female slaves.Footnote 87 Likewise, in a 1676 circumcision ceremony, the groom Musâhib Mustafa Pasha presented an artist female slave to the sultan’s mother and bath attendant (tellâk) female slaves to each of the sultan’s consorts.Footnote 88

The imperial palace also acquired female slaves from other members of the court. Before his death, Ahmed Agha (d. 1596), the steward of the door keepers (kapıcılar kethüdası) and great master of the stable (büyük mirâhur), had noted that Safiye Valide Sultan had the rights to his cash and his female slaves.Footnote 89 When Grand Vizier Hasan Pasha died in 1792, his property was confiscated and his female slaves were sent to the imperial palace.Footnote 90 In some cases, when manumitted female slaves who had already left the imperial palace died, their own female slaves were taken into the imperial harem. Again, as will be discussed in Chapter 2, the inheritance relationship between manumitted slaves and their manumitters was predicated on the fact that part of a palace woman’s estate would be delivered to her master. When a female slave of a manumitted palace woman was taken into the imperial palace, the price of the slave was reduced from the sultan’s share of the estate, as he was one of the heirs of the palace women. To give but one example from among various possibilities, when Bekdaş Hatun died in 1720, her female slaves were given to the reigning sultan Ahmed III.Footnote 91

Purchase was another means of acquiring slaves for the palace.Footnote 92 Eighteenth-century historians Subhi and Şem’dânî-zâde noted that a female slave was bought for Saliha Sultan, mother of Mahmud I, from a slave dealer.Footnote 93 Şem’dânî-zâde also added that the vizier of the period bought female slaves for the Valide Sultan from the slave market.Footnote 94 European accounts likewise provide numerous examples of the practice of purchasing female slaves for the imperial harem. According to Nicolas de Nicolay, who came to Istanbul in 1551 in the retinue of Gabriel de Luel, Sieur d’Aramon, French ambassador to the Ottoman court, some of the sultan’s women and concubines were purchased from merchants.Footnote 95 Aubry de la Motraye noted that the women in Ahmed III’s harem had all been bought.Footnote 96 Dallaway stated that the female slaves of the seraglio are either privately bought or exposed to sale in the Avrat bazar.Footnote 97

Especially slave wet nurses (daye cariyes) were purchased to meet the needs of the sultan’s children.Footnote 98 Şem’dânî-zâde added interesting anecdotes to his account about female slaves taken to the palace for this purpose. During the reign of Abdulhamid I, the sultan’s consort became pregnant, and a wet nurse thus became necessary. Ulema and imams informed the members of the neighborhood, and the inns were searched for Circassian or Georgian women who were three months pregnant. He added that these women were required to be pleasant and long-haired.Footnote 99

The prices paid for female palace slaves are rarely known, although it is possible to find some information. Certainly, the price of female slaves varied enormously according to their qualities. During the reign of Mehmed IV, artist female slaves were purchased at prices ranging from 36,000 to 406,000 akçe.Footnote 100 The prices of Georgian and Russian female slaves taken for the imperial harem in the reign of Ahmed III were between 150 kuruş and 250 kuruş, while others cost between 280 and 320 kuruş.Footnote 101 During the reign of Abdulhamid I, a very high sum of 16,000 kuruş was paid for one Georgian slave,Footnote 102 while a Russian slave was purchased for only 87 kuruş.Footnote 103 This discrepancy was observed in Melling’s account, which pointed to beauty alone being a key indicator of price and thus value; talents and other interesting qualities counted for little.Footnote 104 This accorded to the value of female slaves within the broader Ottoman society, in which prices varied according to the girl’s beauty, age, and other characteristics.Footnote 105

*

When pages were taken for the Enderun, it was recommended that those from certain regions be preferred and that those from certain other places be avoided.Footnote 106 In the majority of cases, the available sources do not allow us to trace the geographic origins of individual female palace slaves. It is clear, though, that slaves of various origins were taken to the imperial harem, including Circassian, Georgian, Abkhasian, Russian; women from Africa and Europe also became slaves. Angiolello noted that girls in the Old Palace are all Christians and that they had been brought from various parts of the world.Footnote 107 Other European writers stated that most of the women in the palaces were Christians from Greece, Hungary, Poland, Wallachia, Italy, or other regions.Footnote 108 D’Ohsson noted that there were women in the imperial harem who were brought from Europe, Asia, and Africa.Footnote 109 J. Dallaway and Ch. M. Deval also noted that female palace slaves were Circassian and Georgian.Footnote 110 Archival documents from the eighteenth century provide corroborative evidence. An order was given to a governor (beylerbeyi) to purchase Circassian, Abkhazian, and Russian slaves for the imperial harem.Footnote 111 A woman named Sarayî Şehbaz (d. 1716) was from Malta, while Sarayî Simten Kadın, who was manumitted by Mustafa III, possessed a slave from Wallachia named Lutfiyye.Footnote 112 In every period, black women from Africa also served in the imperial harem, although they were few in number. According to Ottaviano Bon’s account, in the seventeenth century, black women were brought to the imperial court from Cairo.Footnote 113 In the eighteenth century, at least two black women (zenciye) were present in the imperial harem: Zenciye Saide (d. 1776) and Zenciye Halime, who were manumitted by Âlicenab Kadın, Mahmud I’s head consort.Footnote 114 The varied origins of female palace slaves in the eighteenth century more or less reflect the situation of other slaves living in other parts of the Ottoman Empire.Footnote 115

It is not possible to determine at what age each female slave entered the palace, but it is understood that there was no standard practice concerning the age of entrance to the harem. Some of the slaves entered the palace as children, while others entered at a later age. It is said that Turhan, who later became the concubine of Sultan Ibrahim, was only four years old when she was captured by raiders and then presented to the palace.Footnote 116 According to D’Ohsson’s account, since some people intended to offer girls to the sultan as an act of homage, they carefully cared for the girls and sent them to the palace when they reached the age of ten or eleven.Footnote 117 Sungur, who appeared at the beginning of this book, wrote to Selim III and stated that she had been taken to the palace at the tender age of five.Footnote 118

Additionally, some features related to physical appearance and character were sought in women who were taken to the court, and in some cases chronicles provide clues on this issue. For instance, according to Şem‘dânî-zâde’s account, a summer palace was constructed in Beykoz in 1764 and female slaves with eminent and desirable attitudes (mümtaz ve müşteha tavırlı) were selected in addition to pages.Footnote 119

*

Regardless of their geographical origins or the means through which they were acquired, girls started an entirely new life once they entered the palace. D’Ohsson noted that girls selected for the palace were first examined by a woman assigned to this office; the slightest bodily defect was sufficient to exclude the girl.Footnote 120 Female slaves were divided into Chambers similar to those of the pages in the Enderun.Footnote 121 They were then trained under the supervision of more experienced women.Footnote 122

Following their entrance into the palace, the girls were converted to Islam through the repetition of the core Islamic creed, “There is no God but Allah, Muhammed is the Messenger of Allah.”Footnote 123 During the first period of their enslavement, called acemilik (novitiate), they underwent training in court manners under the supervision of elders. They were employed in the activities to which they were best suited. They were given knowledge of the Islamic religion, they learned Turkish, and some of them even received education in sewing, embroidery, music, and dancing. Angiollello, who served in the palace during the reign of Mehmed II, described the training of women in the sultan’s harem. He noted that senior women taught the new ones how to speak and to read, instructed them in Muhammedan law, and showed them how to sew and embroider, to play instruments, and to sing. The girls also learned about Ottoman ceremonies and customs, to the degree that they had the inclination to learn.Footnote 124 D’Ohsson also observed that the newly acquired slaves were educated by older women; at the end of their novitiate, they began their service in the harem.Footnote 125

Names of Female Palace Slaves

Female slaves were given new names that usually accorded with their physical appearance and their personality.Footnote 126 These new names served as a break from old identities and the adoption of new ones; the girls’ new life, then, was marked by the adoption of a new name and identity. In Ottoman society, female slaves generally were given Persian names, mostly related to flowers, fragrances, and other pleasures of life.Footnote 127 On the other hand, some female slaves bore Arabic names.Footnote 128

In Ottoman society, a person was called by his/her father’s name. When a person became a slave, his/her new status was marked by renaming. Male slaves – and also devshirmes – were called “bin Abdullah” (son of a slave of God); female slaves, including those in the palace, were called “bint Abdullah” (daughter of the slave of God).

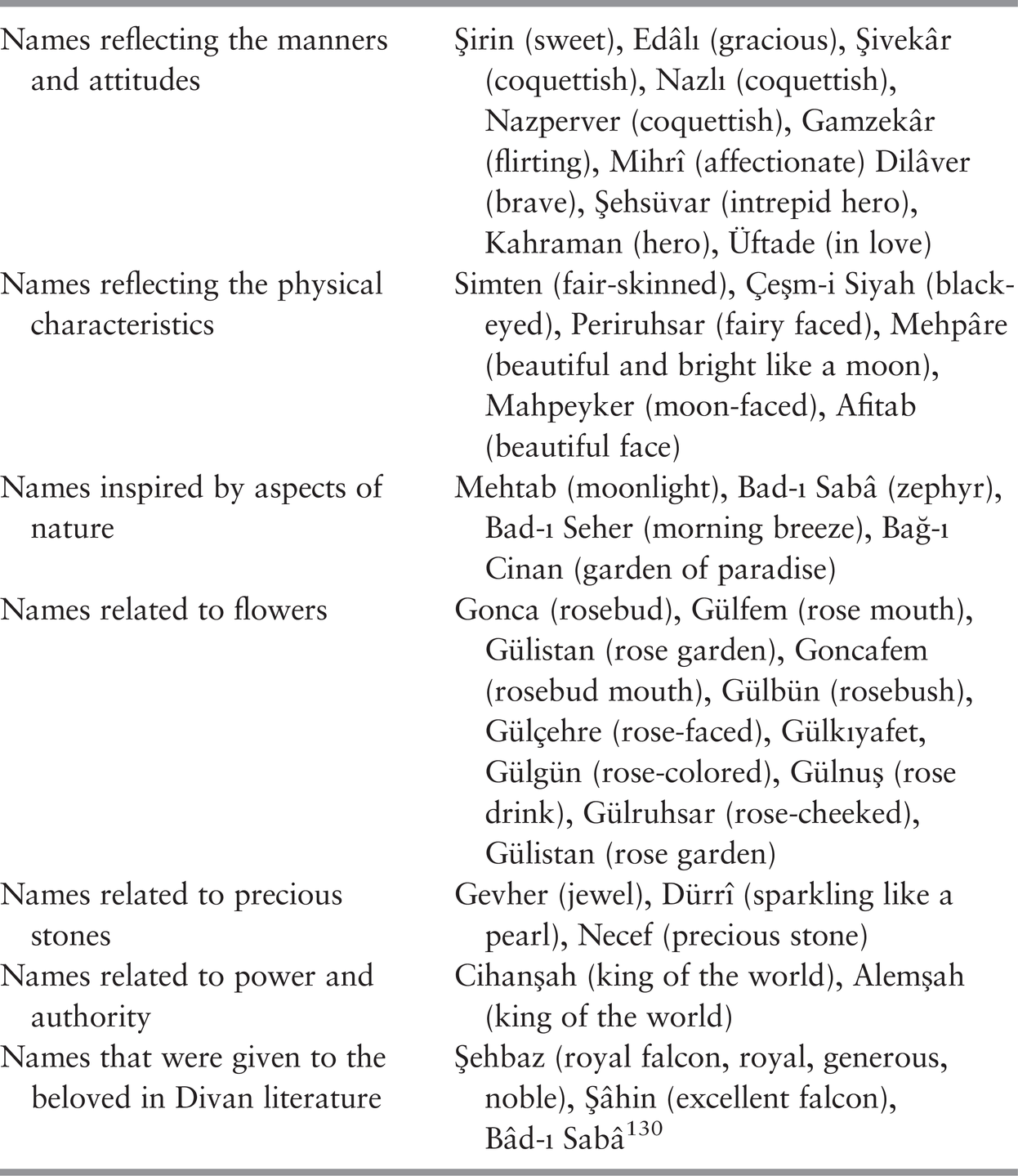

Archival records that provide information about the names and origins of female slaves who were taken to the palace offer the possibility of two naming alternatives. It is possible that some female slaves had already been given new names before they entered the palace, and they then kept these names following their admission. Other slaves were given new names only after they had entered the harem. From the eighteenth-century records, it appears that the great majority of slaves in the harem had Persian names, although a few had prestigious Arabic names associated with the family of the Prophet Muhammed, such as Ayşe, Fatma, Zeynep, and Hadice.Footnote 129 As far as the Persian names have been evaluated, girls were given names than can be categorized roughly into several types. Some girls were given names that reflected the manners, attitudes, and physical characteristics. Others carried names that were inspired by aspects of nature. Some women bore names related to flowers, precious stones, and power and authority. Few women had names that were given to the beloved in Divan literature (Table 1.1)

Table 1.1 Categorization of the Persian names carried by palace women

| Names reflecting the manners and attitudes | Şirin (sweet), Edâlı (gracious), Şivekâr (coquettish), Nazlı (coquettish), Nazperver (coquettish), Gamzekâr (flirting), Mihrî (affectionate) Dilâver (brave), Şehsüvar (intrepid hero), Kahraman (hero), Üftade (in love) |

| Names reflecting the physical characteristics | Simten (fair-skinned), Çeşm-i Siyah (black-eyed), Periruhsar (fairy faced), Mehpâre (beautiful and bright like a moon), Mahpeyker (moon-faced), Afitab (beautiful face) |

| Names inspired by aspects of nature | Mehtab (moonlight), Bad-ı Sabâ (zephyr), Bad-ı Seher (morning breeze), Bağ-ı Cinan (garden of paradise) |

| Names related to flowers | Gonca (rosebud), Gülfem (rose mouth), Gülistan (rose garden), Goncafem (rosebud mouth), Gülbün (rosebush), Gülçehre (rose-faced), Gülkıyafet, Gülgün (rose-colored), Gülnuş (rose drink), Gülruhsar (rose-cheeked), Gülistan (rose garden) |

| Names related to precious stones | Gevher (jewel), Dürrî (sparkling like a pearl), Necef (precious stone) |

| Names related to power and authority | Cihanşah (king of the world), Alemşah (king of the world) |

| Names that were given to the beloved in Divan literature | Şehbaz (royal falcon, royal, generous, noble), Şâhin (excellent falcon), Bâd-ı SabâFootnote 130 |

Families of the Female Palace Slaves

Since a person was called by his or her father’s name in Ottoman society, an examination of the names of manumitted female palace slaves provides information not only about their origins but also about the identity of their fathers. In the available registers belonging to female palace slaves, the great majority of them (97 percent) are listed as bint (daughter of) Abdullah,Footnote 131 as was also the case for other Ottoman women of slave origin. The name Abdullah was used interchangeably with the names of Abdülmennan, Abdülkerim, Abdürrahim, and some other names relating to God. An example of a woman who was not listed as “bint Abdulah” is Sarayî Amine Hatun bint Ahmed Beşe bin Abdullah.Footnote 132 The identification of the mother is more difficult than that of the father. As a requirement of Islamic law, living parents including mothers appeared in estate registers as heirs as long as they were alive. However, among the examined examples, it was extremely rare that parents appeared as heirs in the estate registers of manumitted female palace slaves.

The story of Sarayî Necef, also known as Saliha bint Abdullah bin Abdülmennan, is unique and thus very important in revealing the family network of female palace slaves. In a court case dated 1715, Necef Hatun’s estate was divided among her heirs. She had been manumitted by Hadice Sultan (1662–1743), who was the daughter of Mehmed IV (r. 1648–1687). Necef’s heirs were her previous master Hadice Sultan, her husband, el-Hac Halil Agha bin Ali bin Himmet, her minor daughter Emine, and, interestingly, her mother Sarayî Zeynep bint Abdullah, who was also of slave origin.Footnote 133 One year later, Sarayî Zeynep, who was also manumitted by the same Hadice Sultan, appeared in the law court and stated that her grandchild Emine had died; she thus demanded her rights over the estate of the young girl.Footnote 134 The case of Necef bint Abdullah is unique for various reasons: it shows a palace woman who had knowledge of her mother, and both daughter and mother were manumitted by the same master. It is possible that Necef and her mother Zeynep had been taken to the palace together.Footnote 135 There are certainly several examples showing that daughters of wet nurses also lived in the harem.Footnote 136

The story of Zeynep and Necef leads to the definition of another category, that of sarayî daughter (sarayî kızı). In some very rare examples, palace women are listed as sarayî kızı. It is possible that those girls who had at least one parent affiliated to the imperial court were named sarayî kızı. One of the defining features of this group of sarayî kızı was that their fathers were not listed as Abdullah. In general, the sarayî kızı had a palace-affiliated mother. For instance, Sarayî kızı Emetullah was the daughter of Sarayî Zeynep and Halil Agha bin Himmet,Footnote 137 while Sarayî kızı Fatma Hatun was the daughter of Usta Ahmed bin Osman and Sarayî Hanife.Footnote 138

Brothers and sisters also appear extremely rarely in the examined estate registers. In my examination of 460 estate registers in which inheritors are recorded, I found only four women who had a named mother, only four who had named sistersFootnote 139 and only one woman who had a brother.Footnote 140 Sisters of the examined palace women did not carry the title sarayî.Footnote 141 This raises the possibility that the siblings may have been brought to the capital together, and then one was taken to the palace while the others were sent to different households. For instance, Reftâridil was sold together with her sister, but only Reftâridil was taken to the palace where she became the consort of Murad V.Footnote 142

The very rare appearance of family members as heirs in the estate registers raises the question of how much contact these palace women were able to maintain with their natal families. In 1864, a minor female slave was presented to Behice Sultan (b. 1848), the daughter of Sultan Abdulmecid. A document was prepared stating that the girl’s relatives would not interfere with her. This implies that it was not considered appropriate for female slaves who were taken to the imperial palace to be contacted by their families.Footnote 143 Yet some rare examples from earlier periods do reveal that some female palace slaves were in contact with their family members, but only those who had some link with the imperial court. In the seventeenth century, the famous Canfeda Hatun, a chief administrative official in the harem, had two brothers that she looked after, both of whom held the rank of pasha.Footnote 144 Likewise, Hadice Turhan Valide Sultan’s (d. 1683) brother Yunus Agha (d. 1689) was living in Istanbul.Footnote 145

In sum, the high ratio of “bint Abdullah” and the extremely rare appearance of family members, such as mothers and siblings as heirs, imply that the great majority of these girls lost contact with their family members. These girls came from many different regions, but all were divorced from their own lineage as they were gathered into the harem. This situation impacted their relationship with the imperial court and strengthened their sense of belonging.

Relations within the Imperial Harem

Very little is known about the internal functioning of the harem, or of the relationships that developed between its residents. The account of Derviş Abdullah, halberdier (teberdar) of the Old Palace, provides an idea about how female palace slaves were perceived within the palace. He noted that “female slaves were regarded as daughters, and since it was a religious duty for Muslim believers to protect their children, it was also compulsory to protect female slaves.”Footnote 146 Likewise, in one archival record, female palace slaves were defined as those who were nourished, cared for, and educated by the imperial court.Footnote 147

The long-lasting relationship between the imperial court and its female palace slaves was rooted in the harem, and residents of the harem were attached to the household through various layers of associations that were often based on emotional and material bonds. Residents of the imperial harem, much like those of the Enderun, occupied various ranks within the hierarchy and were protected and provided with benefits during their service period. Importantly, household members were related to the household through a patronage relationship. Household heads were responsible for providing for their dependents, safeguarding their best interests, and ensuring their welfare. The principle of Islamic tradition ordering that slaves should be treated well might have been influential in their attitude toward slaves. Patronage relationships were fostered in the imperial court and were realized across various layers, and this shaped the dynamics among the members of the imperial court.

*

In every period, male and female members of the imperial court received regular stipends called mevâcib and ulufe in return for their services. This practice was not enacted exclusively at the Ottoman palace: in a similar manner, residents of harems across the Near East and South Asia received monthly salaries.Footnote 148 A person’s position within the imperial harem, or in the Enderun, played a major role in determining their stipends.Footnote 149 According to the mevâcib registers belonging to the periods of Selim III and Mahmud II, female palace slaves received between 5 and 500 akçe per day.Footnote 150 In a mevâcib register from the period of Mahmud I, 446 female palace slaves were recorded and, of these, 52 received between 20 and 100 akçe, 21 received 15 akçe, and 67 received 10 akçe. The vast majority (306) received only 5 akçe.Footnote 151 Among 473 female palace slaves listed in a mevâcib register from the period of Mahmud II, almost 20 percent (92) received 20 akçe or more, but the rest received no more than 15 akçe.Footnote 152 Additionally, some members of the harem received a share of the customs.Footnote 153

Residents of the imperial harem were assigned food, listed in the records as me’kulât.Footnote 154 The great majority of female slaves are listed together under a general category.Footnote 155 Higher-status residents, such as the chief administrative officer and the wet nurse, were listed separately. Female slaves in the imperial harem were also assigned clothing, called melbûsât.Footnote 156 Writing in 1534, Benedetto Ramberti noted that “the sultan gives pay of ten to twenty aspers per day to the girls in the Palace and twice every year at the two Bairams he has them clothed in stuffs of silk.”Footnote 157 Other objects that the harem members needed were also provided.Footnote 158

Apart from salaries, clothing, food, and other necessities, harem residents received extra payments and gifts called in‘âm, ihsân, or ‘atiyye on specific occasions. These gifts paved the way in strengthening the ties between the imperial household and the members of the imperial court.Footnote 159 These gifts included goods of various kind and quality.Footnote 160 Habibe Kadın bint Abdullah, who was the consort of Mahmud I (r. 1730–1754), designated monetary and tangible gifts, including several types of textile furnishings, to several harem residents including the black eunuch Beshir Agha and the female slaves of the head treasurer, of the mistress of the pantry, of several kalfas, and others.Footnote 161

The possession of female slaves by various people in the imperial harem paved the way for a diversification of patronage relations. Members of the imperial court acted as benefactors and offered patronage, depending on their status in the hierarchy. For instance, Süleyman Agha bin Abdülmennan, the Agha of the Old Palace, donated several items as a trousseau to his slave Hibetullah bint Abdullah in 1740 while she was still a child. The objects and jewelry assigned to this young slave were astonishing, both in number and value: the trousseau included two pairs of emerald and diamond earrings, a gold bracelet, two emerald belts, fourteen rings made of various gems, and other accessories made of gold and precious stones. The value of furs and other clothing items was not less than that of the jewelry: three furs of different qualities, fifteen caftans, twenty dresses, and other clothing items. The trousseau also contained a variety of household items, including textile products, candelabra, trays, a coffee ewer, a basin, a thurible, a rose water flask, and even a clock. The total value of all these items was 12,080 kuruş, which was a huge amount compared to the generosity of Habibe Kadın. Since Hibetullah was too young to take care of these items, Süleyman Agha entrusted these objects to Fatma Hatun, who was another of his slaves.Footnote 162

Harem residents received gratuities called ıydiye bahşişi on religious holidays.Footnote 163 D’Ohsson noted that in two bairams, harem residents were given gratuities.Footnote 164 They also received muharremiye, which was pocket money given out at greeting ceremonies held at the beginning of the month of Muharrem.Footnote 165 Harem residents were also granted favors before imperial departures (hareket-i hümâyun). For instance, when Ahmed III moved from his waterside residence in Eyüb to Istanbul, he bestowed gratuities upon the harem residents.Footnote 166

Weddings and birth ceremonies within the imperial dynasty were special occasions during which harem residents received presents as members of the household. Presenting gifts to the residents of the imperial harem on the occasion of imperial weddings was an ancient tradition.Footnote 167 When Emine Sultan, a daughter of Mustafa II, married Çorlulu Ali Pasha, the latter offered gifts to the head treasurer of the Sultan and the Valide Sultan, to the mistress of laundry and her staff, and to the female slaves who were sent to Emine Sultan’s palace.Footnote 168 Likewise, as reflected in the registers of velâdet-i hümâyun (imperial birth ceremonies), members of the imperial harem were presented with gifts following the birth of members of the dynasty.Footnote 169

The education given to members of the imperial harem can also be evaluated in the context of patronage relations. As mentioned above and resembling what took place within the Enderun, female slaves received education in accordance with their capacities and position.Footnote 170 Some harem residents received education in Islamic sciences, reading, calligraphy, sewing, and embroidery, as well as several branches of art such as literature, poetry,Footnote 171 dance and music,Footnote 172 shadow puppetry, and other theatrical skills.Footnote 173 In addition, some female slaves had training in medical fields.Footnote 174 Bobovi, who was a page in the seventeenth century, stated that the primary aim of education in the harem was to teach Ottoman court culture and loyalty to the imperial household.Footnote 175

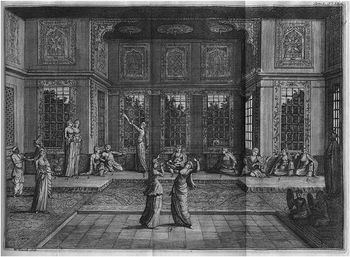

Figure 1.4 “Women dancing in the Harem.” Aubry de la Motraye. A. De La Motraye’s Travels Through Europe, Asia and into Part of Africa (London: Printed for the author, 1723).

The education given in the imperial harem was important when we take into consideration the future roles of female palace slaves following their transfer from the imperial court. As will be discussed in the following chapters, following their departure from the palace, these women were absorbed into the local communities with an intact “palace identity.” This allowed them both to establish social and communal relationships with people, especially with members of their neighborhood, and to represent court culture outside of the palace. The women were married primarily to members of the askeri class (members of the ruling elite), and it was thus important that they be trained properly, considering their future positions in the outside world. A statement used in one court register hints that some harem residents were trained as meticulously as one would train one’s own child (evladiyet üzere terbiye edib).Footnote 176 This approach seems to have been informed by Islamic theory.Footnote 177

There is no doubt that apart from the patronage relations, an emotional bond was formed among the members of the imperial court. Halberdiers of the Old Palace called each other ocakdaş, referring to their affiliation to the same institution.Footnote 178 Similarly, the common harem experiences of the female slaves of various ages and standings strengthened their attachment to each other. Lost contact with their family members obviously strengthened these ties. It is difficult to reach into the emotional bonds that developed among women in the palace. However, during their palace service, feelings of sisterhood (ahiret kardeşliği) developed among the residents. Sarayî Okumuş Ayşe Hatun bint Abdullah was the adopted daughter (ma’nevî kız) of Hâcce Emetullah Hatun bint Abdullah bin Abdulmennan, who was herself previously the mistress of patients (hastalar ustası) in the Old Palace.Footnote 179 Likewise, a moral and sometimes emotional bond was created between master and female slaves. Hadice Sultan (1768–1822) regarded her head treasurer, Dilpezir Hanım, as her daughter.Footnote 180

The depiction of the harem as an always harmonious institution would be misleading, though. Exceptional situations and distressed relationships certainly existed. Several records across various time periods reflect examples of intrigue, hatred, and competition. Thievery was another fact in the imperial harem. Indeed, it is said that a fire was set in the New Palace in 1665 in order to conceal jewelry thievery in the harem.Footnote 181

In sum, a reconstruction of the harem hierarchy and an examination of the network of relationships that developed in the harem are critical for understanding how manumitted female palace slaves maintained their ties with the imperial court over the longer term. This will serve as a point of departure into the investigation of the lives of these women as they left the harem, which will be addressed in detail in the following chapters.

As I discuss in the next chapter, the slave’s transfer from the palace through manumission did not end her relationship with the imperial court, but rather established a new type of relationship that lasted until her death. Having completed their service period in the imperial harem, female palace slaves were manumitted and transferred from the palace to begin a new life in society. The next chapter examines the process of transfer from the palace and the relationship with the imperial court following these former slaves’ transfer from the palace.