Book contents

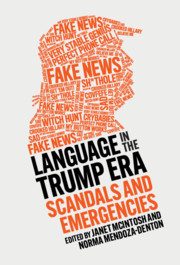

- Language in the Trump Era

- Language in the Trump Era

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Transcription Conventions

- Note on Ethnonyms and Phenotypic Descriptors

- Introduction: The Trump Era as a Linguistic Emergency

- Part I Dividing the American Public

- 1 Part I Introduction: “Ask the Gays”: How to Use Language to Fragment and Redefine the Public Sphere

- 2 The Significance of Trump’s Incoherence

- 3 “Get ’Em Out!”: The Meaning of Ejecting Protesters

- 4 Crybabies and Snowflakes

- Part II Performance and Falsehood

- Part III The Interactive Making of the Trumpian World

- Part IV Language, White Nationalism, and International Responses to Trump

- Index

- References

3 - “Get ’Em Out!”: The Meaning of Ejecting Protesters

from Part I - Dividing the American Public

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 September 2020

- Language in the Trump Era

- Language in the Trump Era

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Note on Transcription Conventions

- Note on Ethnonyms and Phenotypic Descriptors

- Introduction: The Trump Era as a Linguistic Emergency

- Part I Dividing the American Public

- 1 Part I Introduction: “Ask the Gays”: How to Use Language to Fragment and Redefine the Public Sphere

- 2 The Significance of Trump’s Incoherence

- 3 “Get ’Em Out!”: The Meaning of Ejecting Protesters

- 4 Crybabies and Snowflakes

- Part II Performance and Falsehood

- Part III The Interactive Making of the Trumpian World

- Part IV Language, White Nationalism, and International Responses to Trump

- Index

- References

Summary

This chapter analyzes over fifty cases in which Trump sought to remove confrontational protestors during his campaign rallies. Consideration of the linguistic and semiotic form of Trump’s instructions shows that, most often, they consisted of a grammatical imperative, “Get them out,” addressed to his supporters or to event security. The activity of removing protestors became a tool of interactional messaging which not only allowed Trump to signify about his own self-image but also created opportunities for supporters to embody and enact the political project that Trump advocated. The semiotic notion of “iconicity,” in which a sign represents by way of a resemblance or similarity with its object, provides a key to understanding these events. Trump’s ejecting protestors not only allowed Trump to communicate an image of strong, masculine leadership, but also diagrammed aspects of his proposed policies. The very action of ejecting protestors served as a kind of portrait in miniature of Trump’s promised immigration policy; ejected protestors stood for those persons labelled illegal immigrants who would, Trump promised, be deported. “Get them out” thus came to allude to a large-scale redistribution of power and agency, a new morally righteous populism, that his leadership would bring about.

Keywords

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Language in the Trump EraScandals and Emergencies, pp. 63 - 73Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2020

References

- 2

- Cited by