1.1 Introduction

Over the past thirty years, international treaties for the promotion and protection of investment have proliferated, with over 3,000 such treaties concluded. The bulk of these treaties were concluded in the 1990s and 2000s, largely between developed and developing states.

In general structure, investment treaties provide special protections to foreign investors in host states, such as protections against discrimination, arbitrary treatment and uncompensated expropriation, as well as guarantees of fair and equitable treatment. The scope of coverage of these protections is broad. Generally speaking, the disciplines imposed by these treaties are applicable in respect of any measure attributable to the state in respect of a covered investment or investor, regardless of the subject matter of the measure (e.g. environment, public health, energy policy, etc.), regardless of the responsible organ of government and regardless of the sector of the investment. In addition, investment treaties establish specialised dispute settlement mechanisms. Under the treaties, foreign investors may bring claims for breach of the treaty against the host state before an international arbitration tribunal, generally without having to go first through the host state’s domestic courts.

Traditionally, two theories have been advanced for how host states might benefit from entering into investment treaties. The first theory is that – by offering special protections to foreign investors – investment treaties help developing states attract foreign investment.Footnote 1

The second theory is that – by way of additional effect – investment treaties have positive effects on national governance in the host state. On this latter theory, because of a desire to avoid liability for breaches of investment treaties, developing states will internalise consideration of their international legal obligations into their governmental decision making, reform their decision-making processes, and thereby, over time, improve the rule of law not just for foreign investors but also for all those within their territories.Footnote 2 As Roberto Echandi has put it, the fear of arbitration by foreign investors should act as ‘a deterrent mechanism’ against short-term policy reversals and ‘assist developing countries in promoting greater effectiveness of the rule of law at the domestic level’.Footnote 3 Or, as Stephan Schill has asserted, ‘[d]amages as a remedy sufficiently pressure States into complying with and incorporating the normative guidelines of investment treaties into their domestic legal order’.Footnote 4

Such claims have not been based upon empirical evidence regarding the actual effects of investment treaties on state governance. Rather, proponents of this theory have based their views upon the content of the obligations in investment treaties and assumptions about state behaviour. Kingsbury and Schill, for example, have argued that the obligation to provide fair and equitable treatment – found in almost all investment treaties – ‘ought to prompt States to adapt their domestic legal orders to standards that are internationally accepted as conforming to the rule of law’.Footnote 5 Thus, they predict that the obligations contained in investment treaties will ‘have effects over time on specific law and administrative practices within states’, and that these improvements in governance will not only inure to the benefit of foreign investors but also ‘indeed to others under national law’.Footnote 6 In other words, as a result of incorporating their investment treaty obligations into their dealings with foreign investors, host states can be expected to experience positive ‘rule of law’ spillover effects with regard to governance in the host state generally, such that improvements to the rule of law will be felt by all within the host state, not only covered foreign investors.Footnote 7 We refer, henceforth, to this theory of the possible effects of investment treaties on national governance as the ‘rule of law thesis’.Footnote 8

Over the past fifteen years, there has been a significant amount of empirical research on the impact of investment treaties on foreign direct investment (the findings of which have yielded little consensus).Footnote 9 In contrast, we still know little about the effects of investment treaties on governance. Despite the rule of law thesis implicitly underlying much of the investment treaty discourse, and despite anecdotal indications that ‘the signature of international investment agreements by states was generally not followed by regulatory or institutional changes at the domestic level to enable states to meet their newly acquired commitments’,Footnote 10 empirical studies examining the veracity of this claim have been rare. Mavluda Sattorova’s work on the impact of investment treaties on host state governance is a notable exception.Footnote 11 The purpose of this book is to contribute towards filling this gap.

Three assumptions about state behaviour underlie the rule of law thesis. The first assumption is that states make policy choices to seek to comply with their international treaty obligations. The second assumption is that – out of this desire to comply – states internalise their international investment obligations and that these obligations are taken into account in governmental decision making. The third assumption is that this desire to comply with investment treaty obligations ultimately will become operationalised in the host state’s general dealings with all addressees of its legal and regulatory system.

The rule of law thesis, moreover, is rooted in a traditional view about the way in which the international legal order functions. On this view, states affirmatively seek to comply with their international treaty obligationsFootnote 12 either because it is in their self-interest to do so (they would not have consented to the treaty otherwise)Footnote 13 or because they benefit from the reciprocity of compliance.Footnote 14 Further, when states are tempted not to comply, the argument goes, they face the threat of sanctions, which in turn provides a coercive incentive to comply and deters violations in the future.Footnote 15 International relations literature explains this traditional international law approach through a ‘rational choice’ theory of the state. Rational choice theory considers the state to be rational, which is understood to mean that when setting policies and taking decisions, the state undertakes a cost–benefit analysis of alternative actions and their consequences, and that it chooses the action which maximises its preferences.Footnote 16 Given the benefits of compliance and the costs of violation alluded to above, a rational choice model predicts that states, on balance, gain more from compliance, and as such, expects them, for the most part, to internalise their obligations and comply with them.Footnote 17

There are good reasons to be sceptical of the assumptions underlying the rule of law thesis. First, the rational choice theory on which it is based simply does not reflect the complexities of governance. Indeed, empirical studies on compliance with international law carried out in recent years illustrate how inconsistent compliance is and highlight the many domestic and international factors that can impede it.Footnote 18 Such impediments are amplified in developing countries, where, as established in the law and development literature, low regulatory capacity, and/or the absence of a well-developed regulatory governance model, serve as a further hindrance to the internalisation of international obligations into governmental decision making.Footnote 19

Second, internalising international investment obligations into the myriad processes of government is markedly demanding. The pervasive presence of foreign investment throughout national economies is such that a wide range of entities and persons for whom the state is internationally responsible may take measures of one kind or another with respect to a foreign investment or investor. This wide range of entities and persons is reflected in the wide range of actors that have taken measures giving rise to investment treaty arbitrations. According to a study of investor–state treaty disputes by Zoe Williams, examining 584 arbitration cases from 1990 to 2014, 61 per cent of cases were triggered primarily by administrative measures; 26 per cent were triggered by legislative measures alone; and 11 per cent were related to judicial decisions.Footnote 20 Moreover, the economic sectors of the underlying investments in these disputes ranged across all aspects of the host economies, from investments in extractive industries to banking to construction to agriculture to the provision of public services (energy, water services, etc.) to manufacturing, transport and telecommunications.Footnote 21

In this introductory chapter, we develop a framework for thinking about the internalisation of international treaty obligations in governmental decision making that attempts to take account of the complexities of governance. In so doing, we lay out a typology of processes whereby international investment treaty obligations may be internalised and identify factors that may affect whether and to what extent international investment law is internalised by the state. This framework serves as the background for the main body of the book in which we present case studies addressing whether and how a select group of governments in Asia internalise international investment treaty obligations in their decision-making processes: India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Republic of Korea, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Viet Nam.Footnote 22 These case studies serve as a foundation for testing our theoretical framework by empirically examining whether and to what extent these governments take investment treaty obligations into account in their governmental decision-making processes and whether such internalisation has had spillover effects on governance in the state more generally.

The organisation of this introduction is as follows. Section 1.2 begins by setting out the principal research questions with which we are concerned in order to clarify the scope of our inquiry. We additionally set forth a definition of ‘internalisation’ in the context of our thinking about the role of investment treaties in governmental decision making. Section 1.3 situates the project in the existing theoretical and empirical literature on the role of international law in state behaviour. Section 1.4 builds on the literature to set out a framework for exploring the internalisation of international investment treaties by governments. In Section 1.4, we operationalise the concept of internalisation and offer a typology of the kinds of internalisation processes that states may adopt. In Section 1.5, we consider factors that may impact the internalisation of investment treaty obligations and the extent to which governments take those obligations into account in their decision making. Section 1.6 provides an introduction to the case studies that make up the core of this volume, addressing the issues of case selection and methodology.

1.2 Definitions, Research Questions and Scope

For investment treaties to improve governmental administration, the obligations contained within them must have an effect on the decision-making processes of government. They must be ‘internalised’ into the domestic regulatory system. Such internalisation is a foundational assumption to the claim of the rule of law thesis that investment treaties will improve domestic governance. Yet, as mentioned earlier, there are reasons to be sceptical about the degree of internalisation actually present in government and the role of international obligations in governmental decision making.

We define ‘internalisation’ as referring to the formal and informal processes by which the state’s international legal obligations are taken into account in governmental decision making. Our focus, within government, is on the executive, the public bureaucracy and the legislature. In setting this definition, we note two main decision-making situations in which governments may take international law into account. The first situation is when the government implements international law as a domestic law or regulation. In this situation, the government naturally considers international law because the international obligation forms the subject matter of the governmental measure. The second situation is when the government adopts a measure on a matter of domestic law or regulation, which is itself not directly related to international law. In this circumstance, while the government may take into consideration whether the adopted measure is in line or in tension with its international legal obligations, such consideration is in a sense ‘elective’ as the international obligation does not form the subject matter of the measure. Our study focuses on this second situation. That is, we are interested in the question of whether governments take international investment obligations into account when they are considering an original domestic measure (e.g., considering whether to issue or revoke a license, adopt a new financial regulation, etc.).

It is important to note how our understanding of ‘internalisation’ differs from the related concepts of ‘implementation’ and ‘compliance’. In our understanding, compliance refers to the level of agreement or conformity between a state’s behaviour and the requirements of an international obligation. Asking about compliance asks a question about an end result and whether a state has actually adhered to the international obligation.Footnote 23 Internalisation, in contrast, and as we use it, refers to the processes whereby the government considers its existing international legal obligations in its decision-making processes. Importantly, our definition of internalisation does not suppose that the state will always decide matters in accordance with its apparent international investment treaty obligations. To adopt such a definition of internalisation would be to conflate the concept with a kind of compliance. Moreover, while it may be true that the internalisation of international legal obligations increases the likelihood that the government will act in conformity with its obligations, this is by no means always the case. As discussed further below, an international obligation may be one of a number of (political, economic, organisational, etc.) considerations in the decision-making process, and governments may ultimately – in the ‘battle of the norms’ – decide in line with other competing norms or interests.Footnote 24 Internalisation, thus, may be a factor that influences compliance but is conceptually distinct.Footnote 25

We also distinguish our conception of internalisation from ‘implementation’. Implementation is typically understood as the adoption of international law into domestic law, its purpose being to give domestic legal effect to international law, making it enforceable before domestic courts by citizens.Footnote 26 Implementation is also understood as carrying out obligations under the treaty and undertaking positive enactments required by the treaty.Footnote 27 After the adoption and ratification of a treaty, implementation represents the stage when international obligations are integrated into domestic law through enactment of domestic legislation or regulation.Footnote 28 Not only is implementation conceptually different from our conception of internalisation, it is also a poor fit for an inquiry regarding investment treaties. Whereas certain treaties require or imply the need to take domestic regulatory or legal action under their terms,Footnote 29 in the case of investment treaties similar action is not required. Governments rather are expected to refrain from certain actions in order to implement and comply with their obligations.

In adopting this conception of internalisation, we position our research as an attempt to identify specific processes for the operation of investment treaties on governmental decision making in a complex regulatory environment (in which states may be taking a variety of steps in order to make their economies attractive to investment). Our research thus attempts to isolate in this environment the impact of investment treaty obligations on the processes of governmental decision making. By way of distinction, this research is interested in the institutional effects of investment treaties, the institutional processes. We do not, therefore, consider questions regarding the subjective awareness of investment treaty obligations by individual decision makers, nor the psychological internalisation of investment treaty commitments. Similarly, the research we pursue is not interested in questions of ‘socialisation’ but, rather, internalisation as an institutional matter.

To this end, our research addresses three main questions:

First, descriptive: whether and if so in what ways do governments internalise investment treaty obligations into their decision-making processes?

Second, explanatory: what are the factors that affect whether governments internalise international investment obligations in their decision making?

Third, inferential: to the extent that there is evidence that states have internalised international investment treaty obligations into governmental decision making, is there evidence that this has led to improvements in regulatory practices more generally, that is, the positive spillovers suggested by the rule of law thesis?

1.3 Internalisation in the International Legal Literature

We conceptualise our understanding of internalisation against a background of existing legal literature: (1) the liberal international school, which blurs the distinction between the international and the national and opens up the black box of the state; (2) the law and development literature, which addresses the role of law in bringing about good governance and development in low- and middle-income countries; and (3) the empirical legal scholarship, which examines the impact of international law through empirical investigations.

Traditional international law has devoted little attention to the question of how or whether international legal obligations are internalised or considered in the decision-making processes of governments. With respect to the question of how international law impacts domestic law, most scholarship has explored questions of ‘compliance’ or ‘implementation’, proceeding on the underlying yet unspoken assumption that governments internalise their international legal obligations and take them into account in their decision making (even though there may ultimately be forces or reasons which result in non-compliance).

Classic international law treats the state as a unitary actor, without delving into internal state dynamics. The classical literature has argued that states comply with international obligations because it is in their self-interest to do so (they would not have consented to the treaty otherwise)Footnote 30 or because they benefit from the reciprocity of compliance.Footnote 31 Further, classical realist theory asserts that when states are tempted not to comply, the threat of sanctions provides a coercive incentive to comply, and deter violations in the future.Footnote 32

The classical approach, to which the rule of law thesis seems to owe much, rests on a ‘rational choice’ theory of the state. The rational choice theory considers the state to be rational, which is understood to mean that in making decisions, the state undertakes a cost–benefit analysis of alternative actions and their consequences, and that it chooses the action, which maximises its preferences.Footnote 33 Given the benefits of compliance and the costs of violation, a rational choice model predicts that states, on balance, will gain more from compliance, and as such, assumes that, for the most part, states will take their international obligations into account and comply with them.Footnote 34

Moving away from classical, realist paradigms, liberal international legal theory exposes the fiction of the unitary state model and opens up the ‘black box’ of the state.Footnote 35 The work of scholars such as Harold Koh and Gregory Shaffer examines the impact of domestic preferences and dynamics on the international behaviour of a state.Footnote 36 Rather than seeing the state as a unitary actor with one unified interest (as realist theories of the state have), liberal theory emphasises that the state is ‘disaggregated’ into different, and at times competing, actors and interests.Footnote 37 This literature recognises the important impact of domestic factors, structures and actors – such as surrounding social and political discourses or behavioural factors – on the manner or extent by which international obligations become internalised within the state by the government as well as within society.

Within this realm, Koh’s work on the transnational legal process defines the transnational legal process as ‘the theory and practice of how public and private actors – nation states, international organisations, multinational enterprises, non-governmental organisations, and private individuals – interact in a variety of public and private, domestic and international fora to make, interpret, enforce and ultimately, internalise rules of transnational law’.Footnote 38 Through this transnational legal process, states internalise international law not only into their domestic legal system but also more broadly into their domestic practices, values or processes. In other words, the internalisation process is not limited to legal means but may also be of a social or political nature.Footnote 39 It is also not only limited to state actors, but both (domestic and transnational) state and non-state actors have a role in the internalisation process.Footnote 40

Shaffer’s work on ‘transnational legal orders’ and ‘state change’Footnote 41 follows a similar logic, which emphasises the role of domestic factors on state behaviour. In Shaffer’s view, domestic dynamics are the most important factors in understanding the impact of international rules on the state: ‘Arguably, the most important determinant of state change is the affinity of the transnational legal reform efforts with the demands and discursive frames of domestic constituencies and elites in light of domestic configurations of power and the extent of change at stake’.Footnote 42 Thus, domestic demands, domestic power struggles and domestic culture ‘shape how transnational legal norms are received and implemented in practice’, and ‘[s]ometimes they lead to the rejection of transnational law’.Footnote 43 Goodman and Jinks take a constructivist approach, arguing that the internalisation of international law into national behaviour is a result of ‘patterns of acculturation’, or a process of socialisation of social pressures on the state.Footnote 44 Jacobson and Weiss similarly observe that: ‘The social, cultural, political, and economic characteristics of the countries clearly influence implementation and compliance’.Footnote 45 In the international investment regime specifically, Williams likewise argues that domestic factors are the main reason for investor–state disputes.Footnote 46

The global administrative law literature similarly moves away from sharp distinctions between international and national law. One of global administrative law’s main insights is that many legal and normative activities take place in a global administrative space, which blurs the distinction between the international and national.Footnote 47 The acts of national government officials or regulatory agencies in dealing with the state’s international obligations,Footnote 48 and questions about the impact of international law on domestic governance,Footnote 49 thus fall within this global administrative scope.

Within the law and development literature, there is a strong current of opinion arguing that law is a tool for promoting development in low- and middle-income countries, and that the rule of law and good governance are preconditions for such development.Footnote 50 While this premise has served to underlie much international development policy,Footnote 51 other accounts in the law and development literature note that a central ‘uncertainty’ remains ‘about the validity of basic assumptions underlying efforts to promote legal reform’, and that ‘given what is at stake for inhabitants of developing countries’, this uncertainty is ‘unsettling’.Footnote 52 Trebilcock, Davis and others give reason to be sceptical of optimistic claims as to the power of law to trigger reform, most notably due to the challenges posed by economic, political and/or cultural obstacles.Footnote 53 This study seeks to contribute to this scholarship by empirically investigating (1) whether there is evidence that governments in a select group of countries in Asia have internalised investment treaty obligations into their decision-making processes; (2) what factors have affected whether these governments have internalised international investment obligations in their decision making; and (3) whether there is evidence in these case studies that treaty internalisation has led to governance reforms more generally, that is, the positive spillovers suggested by the rule of law thesis.

In the past decade, international legal scholarship has taken what Shaffer and Ginsburg identify as an ‘empirical turn’.Footnote 54 Empirical studies now focus on the effects and effectiveness of international law and aim to explain variations. Empiricism has emerged in diverse fields of international law, including human rights (e.g. Simmons’ empirical study on the effects of international human rights law on domestic politics),Footnote 55 international humanitarian law,Footnote 56 international trade lawFootnote 57 and international environmental law.Footnote 58 In international investment law, empirical work has focused largely on the economic impact of investment treaties. Notable studies on the impact of investment treaties on FDI flows to host countries include, among others, work by Yackee,Footnote 59 Neumayer and Spess,Footnote 60 and Sauvant and Sachs.Footnote 61 Bonnitcha, Poulsen and Waibel review existing studies.Footnote 62 Others have examined whether an increase in FDI actually promotes growth in host states,Footnote 63 or whether investment treaties are more effective at attracting FDI in certain sectors (such as work by Busse and others on the extractive sector,Footnote 64 work by Colen and Guariso,Footnote 65 and Danzman).Footnote 66

Compared to the work on the economic impact of investment treaties, empirical research on the impact of investment treaties on national governance is sparse. Scholars such as BonnitchaFootnote 67 and CalamitaFootnote 68 have flagged this absence. That said, a notable exception is the recent important work by Sattorova, who has developed an empirical argument with respect to investment treaties and national governance.Footnote 69 Further work in this vein includes Ginsburg’s 2005 article on ‘Bilateral Investment Treaties and Governance’.Footnote 70

Finally, while some recent empirical work has begun to address the intersection of international law and public administration, there has been little work addressing how, if at all, government officials internalise international law when they take decisions regarding original, domestic measures. Exceptions in this regard include work on decision making in the executive branch in the United StatesFootnote 71 and in New Zealand.Footnote 72 We are not aware of any similar studies involving Asian or developing states.

1.4 A Typology of Internalisation Processes and Mechanisms

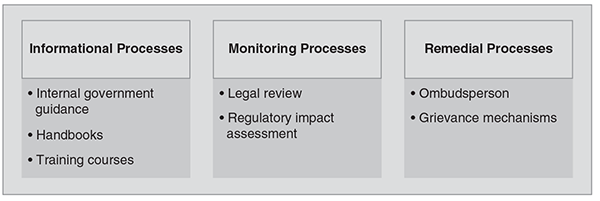

How does a government attempt to internalise its international obligations in its decision-making processes? What are the processes through which this happens?Footnote 73 An empirical inquiry into the abstract notion of internalisation is impossible without clear indicators which operationalise the term. To that end, we distinguish between three broad types of institutional processes of internalisation: informational, monitoring and remedial (Figure 1.1). We would expect to observe at least one of these processes in a state that seeks to internalise its international obligations. Although the focus of our present inquiry is on international investment law, the typology we set out below may be of value to inquiries regarding the internalisation of international law in any field.

Figure 1.1 Examples of informational, monitoring and remedial internalisation processes and mechanisms

Given our interest in the processes of governmental decision making, we take a governance rather than a black letter law approach. In our view, a narrow, black letter law approach would hardly capture the reality of how governments run their affairs and would provide very few insights regarding the possible effects of investment treaties on national governance. We are thus interested not only in formal, legally binding laws and rules but also informal (legally non-binding) norms, practices and processes, through which the government manages its affairs.Footnote 74

We set out our typology in the following subsections.

1.4.1 Informational Processes

By ‘informational processes’, we refer to processes that diffuse information and communicate the state’s international legal obligations to relevant domestic actors.Footnote 75 For example, higher executive or administrative bodies might issue internal guidance, policies or instructions to guide officials as to the application of international obligations. Such processes might include a handbook or a manual, or a training course that informs government officials of the existence and content of the international obligations and seeks to improve knowledge within ministries, agencies or local authorities.Footnote 76 Informational processes attempt to internalise the state’s international obligations ex ante – before or during the process of decision making.

1.4.2 Monitoring Processes

By ‘monitoring processes’, we refer to processes such as a governmental process by which officials screen proposed policies for consistency with international obligations. For example, the regulatory impact assessments (RIAs), which many OECD states have recently introduced,Footnote 77 require government officials to assess whether a proposed regulation is consistent with and complies with the state’s international obligations,Footnote 78 including, specifically, its international trade and investment obligations.Footnote 79 Another example might be a requirement to consult relevant governmental legal experts regarding the compliance of proposed measures with international obligations,Footnote 80 or any ex ante (legal) review of decisions or actions within the government for conformity with international obligations.Footnote 81

1.4.3 Remedial Processes

Remedial processes are designed to correct or defend the state’s compliance with its international obligations.Footnote 82 For example, states might create an ombudsperson that reviews a final administrative regulation for consistency with international obligations or resolves problems with foreign investors before they become formalised disputes.Footnote 83 Alternatively, states might adopt an early warning system to address investment grievances and consider the state’s position under its international obligations.Footnote 84 Such processes are ex post – after a decision has already been made.

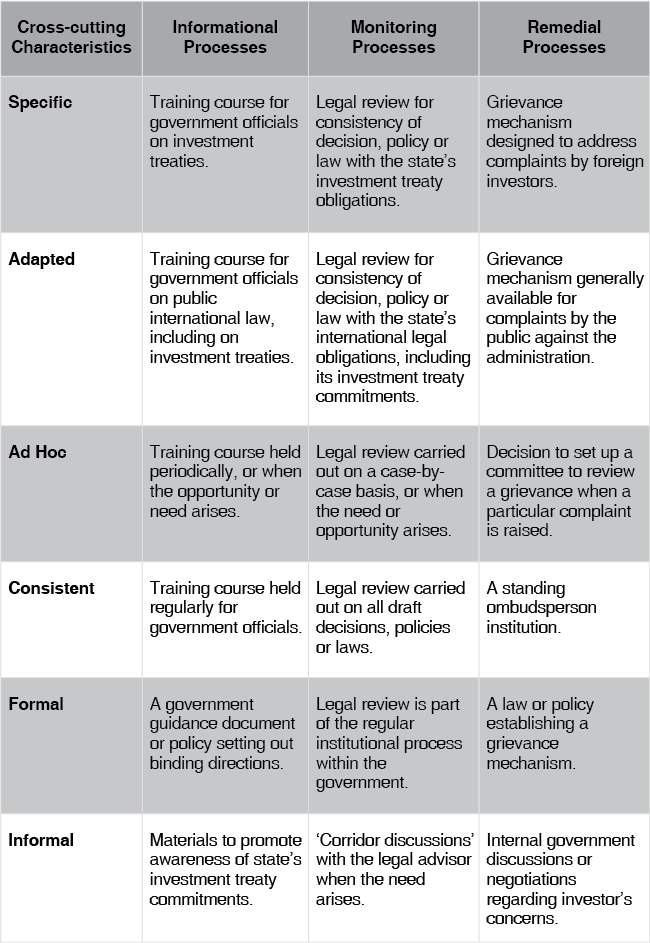

1.4.4 Cross-Cutting Characteristics of Internalisation Measures and Processes

Within the typology of measures that we have identified further refinements are possible regarding processes of internalisation. In the following subsections, we highlight four main cross-cutting characteristics (Figure 1.2). We distinguish between them for analytical purposes, though in practice they may overlap.

Figure 1.2 Examples of cross-cutting characteristics of internalisation measures

1.4.4.1 Specific versus Adapted Processes of Internalisation

Conceptually, a particular measure or process of internalisation may have been designed specifically for investment treaty obligations or it may have been originally designed for a different purpose and later have been adapted for use with regard to investment treaty obligations. An example of a specific process would be the creation of informational handbook on investment obligations, or the creation of an early warning system or process for regulating intra-government coordination in the event of a foreign investor grievance.

In contrast to specific processes, adapted processes are designed for a different purpose but are then applied to investment treaty commitments; for example, a process by which government legal advisors review prospective measures for general legality (which comes to include review for compatibility with investment treaty commitments, alongside other legal commitments). Likewise, RIAs, which monitor for any impacts of proposed measures, also assess the impact of the proposed regulation on investment law obligations (alongside other international and domestic legal obligations). Such processes are created or available for the review of adherence with a different (sometimes broader) category of norms than investment treaty obligations.

1.4.4.2 Ad Hoc versus Consistent Processes of Internalisation

The consistency of a process of internalisation may vary from one country to another or within a particular country as among different internalisation measures. An example of an ad hoc process of internalisation might be a short-term informational campaign on investment treaty obligations for government officials or an episodic training programme, which does not occur on a consistently recurring basis. Examples of consistent processes, by contrast, can be found in well-established processes for the internal assessment of the compatibility of new legislation or new regulation with investment treaty obligations, or in regularised training programmes within government.

1.4.4.3 Formal versus Informal Processes

As observed earlier, we think that a narrow, black letter law approach to internalisation would hardly capture the reality of how governments run their affairs, and would provide few insights regarding the effect of investment treaties on national governance, and how international obligations are considered. When conceptualising processes of internalisation, therefore, we seek to capture the range of both informal (legally non-binding) and formal (legally binding) rules, norms and practices, through which the government manages its affairs.

Informal processes may manifest themselves as processes that are undertaken without a legal obligation to do so. Such informal processes may become institutionalised over time, such as when a process becomes a matter of government convention or custom that is not dependent upon individual actors or groups of actors, for example established, informal channels of communication among agencies.Footnote 85 Informal measures might also include handbooks, education, training, etc., which, although serving as an informational resource for officials about the state’s obligations, are informal inasmuch as the materials do not prescribe binding practices or processes. Formal processes, on the other hand, are established through legally binding norms, such as a regulation establishing procedures for coordinating the exchange of information within government regarding potential investment treaty claimFootnote 86 or a requirement that an RIA be conducted with respect to prospective government measures.

1.4.4.4 Principle versus Practice

Finally, in observing processes for internalisation, it warrants noting that evidence of the existence of a formal process does not mean that it is followed in practice. A state may adopt formal processes of internalisation, which are not used, whether as a result of bureaucratic intransigence, lack of awareness or lack of capacity. Similarly, informal processes, such as governmental conventions, may be recognised in principle but fail in practice to operate in whole or in part. While the existence of a process is a necessary condition for its possible effect on decision making, its existence in itself does not indicate the actual effect that it will have in practice.

1.4.5 Locating Internalisation in Governmental Decision Making

In the preceding section, we have set out a typology of measures and processes which framework operationalises the concept of internalisation as an observable phenomenon of government. In this section, we consider where within government the internalisation of international obligations is likely to be observed.

Looking at the issue from a governance perspective, we see that decision making occurs across the entire state network of government, often at identifiable nodes. Decisions may be taken within different branches of government (executive, legislative and judicial), at different levels of government (central, regional/state and local) and sometimes across branches and across levels. In addition, within each branch of government, there may be nodes along the hierarchy: for example, between central and local levels of government, between ministries and the public administration (bureaucracy), between high-level and mid-level bureaucrats within administrative authorities or agencies, and, in federal states, between the federal and state governments.

Considering the issue from the perspective of international law, as noted earlier, international legal doctrine treats the ‘state’ as a unified entity such that the acts or omissions of all the state’s organs, as personified in its officials, are regarded as acts or omissions of the state for the purposes of international responsibility.Footnote 87 States thus incur international responsibility for actions taken by every branch of government, at every level of government, whether national or sub-national,Footnote 88 as well as by non-state actors exercising governmental authorityFootnote 89 or acting under governmental direction or control.Footnote 90

The wide range of entities and persons capable of taking measures for which the state is internationally responsible is amplified by the nature of investment treaties and foreign investment. The pervasive presence of foreign investment throughout national economies is such that a wide range of entities and persons may take decisions of one kind or another with respect to or impacting upon a foreign investment or investor. Moreover, the broad scope of investment treaty obligations means that virtually all aspects of the host’s economy and regulatory system will be subject to the investment treaty’s disciplines, regardless of sector of investment and regardless of the type of government measure. As a result, for states with investment treaty portfolios, virtually all decisions across government branches and levels with respect to a foreign investor or investment are likely to be of a kind for which the host state may be legally responsible.

That said, it does not follow that all governmental decision makers are equally likely to take decisions that implicate obligations under an investment treaty. As noted previously, according to a study of investor–state treaty disputes by Williams, examining 584 arbitration cases from 1990 to 2014, 61 per cent of cases were triggered primarily by administrative measures, whether taken at the level of central, regional or local government; 26 per cent were triggered by legislative measures alone; and 11 per cent were related to judicial decisions.Footnote 91 Moreover, the economic sectors of the underlying investments in these disputes ranged across all aspects for the host economies, from investments in extractive industries to banking to construction to agriculture to the provision of public services (energy, water services, etc.) to manufacturing, transport and telecommunications.Footnote 92

Building upon this evidence, and the role of administrative or executive decision making in the governance of the modern state, our emphasis in this study is largely focused on the executive and the public administration (although the legislature and the judiciary are also considered in the case studies). To the extent that states may be observed to have internalised their investment treaty obligations, we would expect those processes of internalisation to be found most likely with respect to decision making by the government actors whose decisions are most likely to affect foreign investors and their investments and who are most likely to have direct contact with them – the executive branch of government and its administration. We note, however, that like the state itself, the executive is not a unified decision maker but rather comprised of a wide variety of decision-making nodes and that variations in internalisation among those nodes are likely. Thus, for example, while the ministry charged with negotiating free trade agreements for the government can be expected to evidence a high awareness of the obligations contained in the investment treaties it is charged with negotiating, and to consider them in its decision making, the situation is likely to be different in other ministries or at sub-national levels of government.

1.5 Factors Impacting Internalisation

Inasmuch as international legal theory has opened up the ‘black box’ of the state, it has not accounted for the specific factors and dynamics influencing the work of the executive and the bureaucracy. This is an important omission. Bureaucracies are complex organisations that seldom function in a regular and predictable manner, with many factors influencing bureaucratic effectiveness.Footnote 93 This is even more so in host developing states that lack developed regulatory infrastructures, and must deal with significant political, economic and cultural challenges.Footnote 94

Traditional theories of international law, as noted previously, have assumed that the state will internalise international law. The public administration and public policy literature, antithetically, elaborates on the complexity of the regulatory process and the many factors that influence its success or failure.Footnote 95 Moreover, the law and development literature highlights the daunting challenges that developing countries must overcome in adopting legal or regulatory reform. Davis and Trebilcock thus stress that our ‘expectations about the impact of such reforms should be modest’.Footnote 96

In what follows, we set out a framework for understanding the factors that may affect the internalisation process or the adoption of internalisation measures, drawing on insights from the public policy, international relations, and law and development literature. This model is designed to collect sometimes disparate strands of scholarship and to provide a roadmap for the empirical inquiry carried out in the case studies. While much of this literature is focused on implementation or compliance, its insights are equally instructive for the question of internalisation. To this end, while we take a generous approach, addressing many of the factors mentioned in the literature, we do not take an a priori position regarding the relative importance of any factor. Moreover, depending on the case, factors may overlap or weigh differently in their relative importance. This categorisation serves analytical purposes.

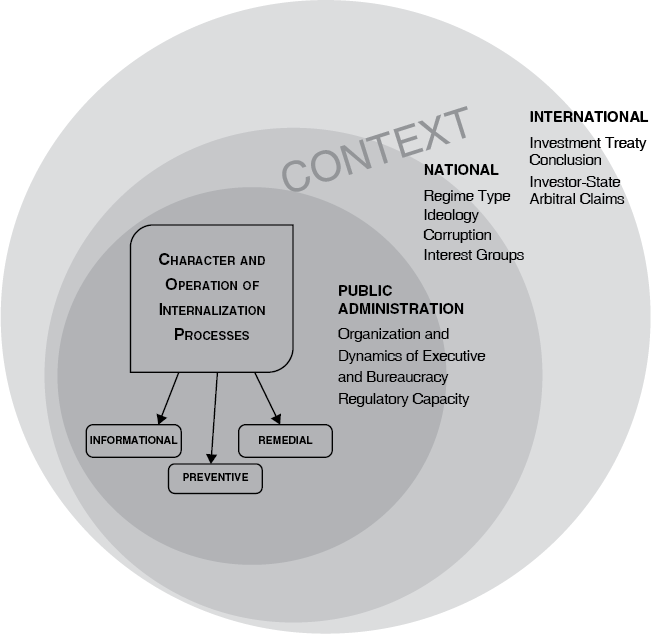

We organise our thinking about the factors that may affect internalisation into three main categories.Footnote 97 The first category encompasses elements with respect to the context of public administration in the state. The second category subsumes elements related to the state’s broader national context. The third category concerns the international context, namely the state’s investment treaty commitments and the presence of claims thereunder. We outline these categories and elements in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3 Model of factors impacting internalisation

1.5.1 Public Administration Context

1.5.1.1 Internalisation Strategy?

The public policy literature stresses the importance of a policy design, or policy strategy, that is, a clearly planned set of measures or processes – be they instruments, designated actors or allocation of resources – for achieving the policy goal.Footnote 98 In operationalising our conception of internalisation above, we outlined our distinction among broad types of processes of internalisation: informational, monitoring and remedial. We recall that typology here because the presence or absence, as well as the character and operation, of such processes will obviously bear upon the internalisation of the state’s investment treaty commitments.

1.5.1.2 Bureaucratic Culture

While the liberal international legal scholarship has opened up the ‘black box’ of the state, it still treats the government and bureaucracy as a ‘black box’, assuming that it translates international law inputs into outputs.Footnote 99 Yet, as James Wilson asserts in his seminal work on bureaucracy, ‘organisation matters’!Footnote 100 The dynamics of organisational and inter-organisational processes are very importantFootnote 101 and may impact internalisation. For example, according to the public policy theory on ‘complexity of joint action’, implementation is negatively related to the number of actors, the diversity of their interests, and the number of decision and veto points.Footnote 102 Contemporary administrations tend to be structurally complex, with a proliferation of inter-organisational (between ministries, agencies, sub-national governments and agencies, civil society, commercial groups, target groups, etc.) connections.Footnote 103 International obligations – often requiring increased collaboration between national ministries, agencies and sectors, as well as with international agencies and partners – add an additional layer of complexity to the inter-organisational process.Footnote 104 Thus, internalisation is likely to depend upon processes for coordination and coherence among different levels of government and jurisdictions.Footnote 105

In developing countries, these challenges are even more profound, and bureaucratic culture may pose a significant impediment. As Trebilcock and Prado conclude: ‘The frailties and failures of public administration in many developing countries have long been documented’.Footnote 106 Indeed, Dam argues that cultural and social factors (in the administration and elsewhere) are of critical importance in determining legal institutions and the success of reform.Footnote 107 And Putnam, in his seminal comparison of Northern and Southern Italian attitudes to the rule of law, has demonstrated how social and cultural attitudes can impact the effectiveness of legal institutions.Footnote 108

1.5.1.3 Regulatory Capacity

The importance of regulatory capacity and resources to implement and comply with international treaties (or any policy for that matter) is widely recognised in the public policy and law and development literature.Footnote 109 In numerous studies, limited regulatory capacity and limited economic and human resources in developing countries have been shown to play an important role in the failure to implement and enforce laws and regulations.Footnote 110 Internalisation thus can be undermined by lack of personnel, inadequate training, lack of technical expertise, lack of regulatory infrastructure, and so on.

Kaufmann and Kraay, for example, demonstrate how costly it is to operate legal or regulatory institutions, to train and retain staff and to disseminate information about the law.Footnote 111 Similarly, Bach and Newman demonstrate how regulatory capacity affects the enforcement of international insider trading rules.Footnote 112 Using Brazil as her case study, McAllister highlights how Brazil’s failure to enforce environmental law is a story of regulatory agencies chronically beset by underfunding and understaffing.Footnote 113 Regulatory approaches that succeed in developed countries may be inadequate or unworkable in the developing world, where the capacity to enforce basic components of laws may be lacking.Footnote 114

In a similar vein, Chayes’ and Chayes’ work on ‘managerial compliance’ has stressed how a lack of state capacity is a barrier to compliance.Footnote 115 As noted, the public administrations in developing countries often lack technical, financial or other capacities, which in turn impact their capability to effectively internalise international obligations. Empirical studies in diverse fields of international law – such as environmentFootnote 116 or human rightsFootnote 117– have illustrated these problems in practice. Corruption has also been identified as eroding capacity and having a significant impact on compliance with international obligations.Footnote 118 Whether subsumed within consideration of regulatory capacity or treated independently, corruption likely stands as a factor affecting internalisation.Footnote 119

Finally, in the field of investment law, Williams has observed a positive link between regulatory capacity and investment disputes, and found that the lower the income and level of development (taken as a proxy for low state capacity), the higher the likelihood that the state will face an investment treaty dispute.Footnote 120 This is an especially suggestive finding given that in contrast to other international regimes (e.g. WTO, ILO, World Bank, IMF, IAEA and many more),Footnote 121 the investment treaty regime lacks coordinated institutional support for regulatory capacity building, arguably undermining domestic internalisation of investment treaty obligations.Footnote 122

1.5.2 National Context

The internalisation of investment treaties may not only be influenced by the public administration context within which a policy is developed but also by broader national factors. In Shaffer’s view, domestic dynamics are the most important factor in understanding the impact of international rules on the state.Footnote 123 Thus, domestic demands, domestic power struggles and domestic culture ‘shape how transnational legal norms are received and implemented in practice’, and ‘[s]ometimes they lead to the rejection of transnational law’.Footnote 124 Jacobson and Brown Weiss similarly state that: ‘The social, cultural, political, and economic characteristics of the countries clearly influence implementation and compliance’.Footnote 125

One notable element of the domestic context that may impact the extent to which states internalise and comply with their international obligations are national elites or other powerful interest groups.Footnote 126 This finding corresponds with the insight of liberal theory that the state is ‘disaggregated’ into different, and at times competing, actors and interests.Footnote 127 The work of Williams supports this observation in the investment treaty regime, finding that treaty violations are often a result of domestic interest group pressure.Footnote 128

In addition to interest groups, the research on compliance suggests that political factors such as regime type and ideology of the ruling government may also impact the way in which a state internalises its international treaty obligations. For example, there is support in the literature for the theory that democracies comply better with their international obligations in general,Footnote 129 as well as studies asserting that democracies comply better with their investment treaty obligations specifically.Footnote 130 On the other hand, leftist governments have historically been more likely to expropriate the property of foreign investors.Footnote 131 Similarly, governments with strong nationalist ideologies may be more likely to resist complying with international legal restraints than governments of different political leanings.Footnote 132 The number of veto players within government also may play a role in internalisation. Some studies, for example, assert that presidential systems – likely due to the small number of veto players – are more likely to violate investment treaties.Footnote 133 At the same time, a smaller number of key decision makers may also suggest a smaller group within which effective internalisation is necessary. In the same vein, internalisation may well be more challenging in federal or decentralised states – with a multiplicity of decision makers – rather than in unitary states.

In thinking about these factors, it warrants bearing in mind that the effects of political factors can be particularly pronounced in developing countries. Important insights from the law and development field highlight how crucial political factors and competing political ideologies and interests can be for the successful adoption of legal or regulatory reforms in developing countries.Footnote 134 In a series of case studies on reforms in Russia, China, Latin America and the Middle East, Carothers and others have shown how the success of reform has often depended upon political conditions, such as support by political elites, or a change from authoritarian to democratic regime.Footnote 135

1.5.3 International Context

1.5.3.1 Investment Treaties: Treaty Conclusion

The rule of law thesis posits that entering into investment treaties will lead states to internalise these international commitments into their governmental decision making.Footnote 136 In other words, the fear of arbitration by foreign investors should act as ‘a deterrent mechanism’ against short-term policy reversals and ‘assist developing countries in promoting greater effectiveness of the rule of law at the domestic level’.Footnote 137 In organising our model of factors impacting internalisation, we include the conclusion of investment treaties as a potential factor leading to internalisation. We acknowledge our scepticism that the simple conclusion of investment treaties is likely to give rise to the development of significant internalisation processes. Nevertheless, we recognise the possibility and, given the claims of the rule of law thesis, consider it important to include in the basic outline of our model.

1.5.3.2 Investment Treaties: Arbitral Claims

Investor–state disputes under an investment treaty may act as a trigger for awareness within the government about the saliency of investment treaties. Large awards, high legal costs, and what is often perceived as an intrusion into state sovereignty, can serve to put investment treaties on the radar. The role of claims in the adoption of investment treaties and in their drafting has already been the subject of significant work. Aisbett and Poulsen have shown, for example, that officials in many developing states acted with a kind of ‘bounded rationality’ in entering into investment treaties, ignoring readily available information about investment claims involving other countries until they themselves were hit by a claim.Footnote 138 Similarly, a study by Manger and Peinhardt has shown how investment treaty claims against capital-exporting states have led those states to more precise drafting of successive investment treaties, moving from vague to elaborate rules in an effort to minimise future litigation risks.Footnote 139 In the present study, we expect that if investment treaties are serving as mechanisms for governmental reform, investment treaty claims will trigger government awareness and increase the likelihood that the state will develop internalisation processes.

1.6 The Case Studies

In the preceding sections, we have conceptually mapped the three main institutional processes or mechanisms through which internalisation would be expected to take place: informational, monitoring or remedial mechanisms. We have also identified some cross-cutting characteristics of these mechanisms, such as whether they are general or specific, ad hoc or consistent, and whether they are formal or informal. Finally, we have sought to flag factors that may impact whether, or the extent to which, internalisation measures are adopted and investment treaties are internalised.

This framework serves as the background for the main body of the book in which we present case studies addressing whether and how a select group of governments in Asia internalise international investment treaty obligations in their decision-making processes. These case studies serve as a foundation for testing our theoretical framework by empirically examining whether and to what extent these governments take investment treaty obligations into account in their governmental decision-making processes, and whether such internalisation has had observable spillover effects on governance in the state more generally.

An empirical assessment of internalisation in individual countries is the only way to develop the evidence necessary to determine the effect of investment treaties on national governance. To that end, the chapters which follow contain qualitative country case studies of eight Asian countries: India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Republic of Korea, Sri Lanka, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. In preparing these case studies, the authors have drawn upon semi-structured interviews conducted with senior- and mid-level government officials and investment lawyers, and the analysis of primary and secondary legal materials. In addition, because the authors are based in the countries about which they are writing, or have deep experience in these countries, they are able to draw upon their own detailed background knowledge of investment governance in the country. We are not aware of any similar empirical studies.

With respect to case selection, the choice of these eight countries for case studies rests on several considerations. The first is principled. The subject of our inquiry – the impact of investment treaties on governance – dictates a primary interest in developing countries, as it is their governance in particular which investment treaties are purported to improve. Thus, six of our eight case studies cover developing countries of different sizes: India, Indonesia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Viet Nam. The inclusion of two developed countries (the Republic of Korea and Singapore) provides comparative context that is valuable in understanding the range of factors which affect the internalisation process and the commonality of certain challenges raised by investment treaties, even for the governments of developed economies. In this regard, we note that we have excluded China from the present study due to its magnitude and complex provincial and administrative structure. China itself might form the basis for a single study.

The second driver for covering these eight states is opportunistic. In undertaking an empirical study of the impact of investment treaties on decision making in national governments, we have proceeded on the premise that, in order to be successful, the case studies should be undertaken by locally based authors with knowledge of the laws and government structures of the subject countries. Further, we have looked to authors who are able to gain access to government officials and other stakeholders for the purpose of developing evidence through interviews and other sources. In this respect, the inclusion of countries in this study has depended upon finding the right author for each country covered, rather than deciding a priori that certain countries must be included. While admittedly this has introduced a degree of serendipity into our case study selection, we do not believe that it impacts upon the value of the work. In the end, this project does not seek to draw broad conclusions about the impact of investment treaties ‘in Asia’. Rather, it seeks to develop a theoretical framework for analysing investment treaty internalisation in government generally and to use that framework to develop an empirical understanding of internalisation in eight Asian countries.

Finally, we have chosen to focus on case studies in Asia, and to work with scholars based in Asia, given our position at the National University of Singapore and the mission of the Centre for International Law which is, inter alia, to advance international law research and capacity in the Asia-Pacific region.