Book contents

- Ingenious Trade

- Ingenious Trade

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Bred in the Exchange: Seamstresses and Shopkeepers

- 2 Girls as Apprentices

- 3 Managing the Trade: Women as Mistresses

- 4 What Girls Learned

- 5 Making Havoc: Discipline, Demeanour and Resistance

- 6 Freedoms and Customs

- Conclusion

- Appendix Who’s Who

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

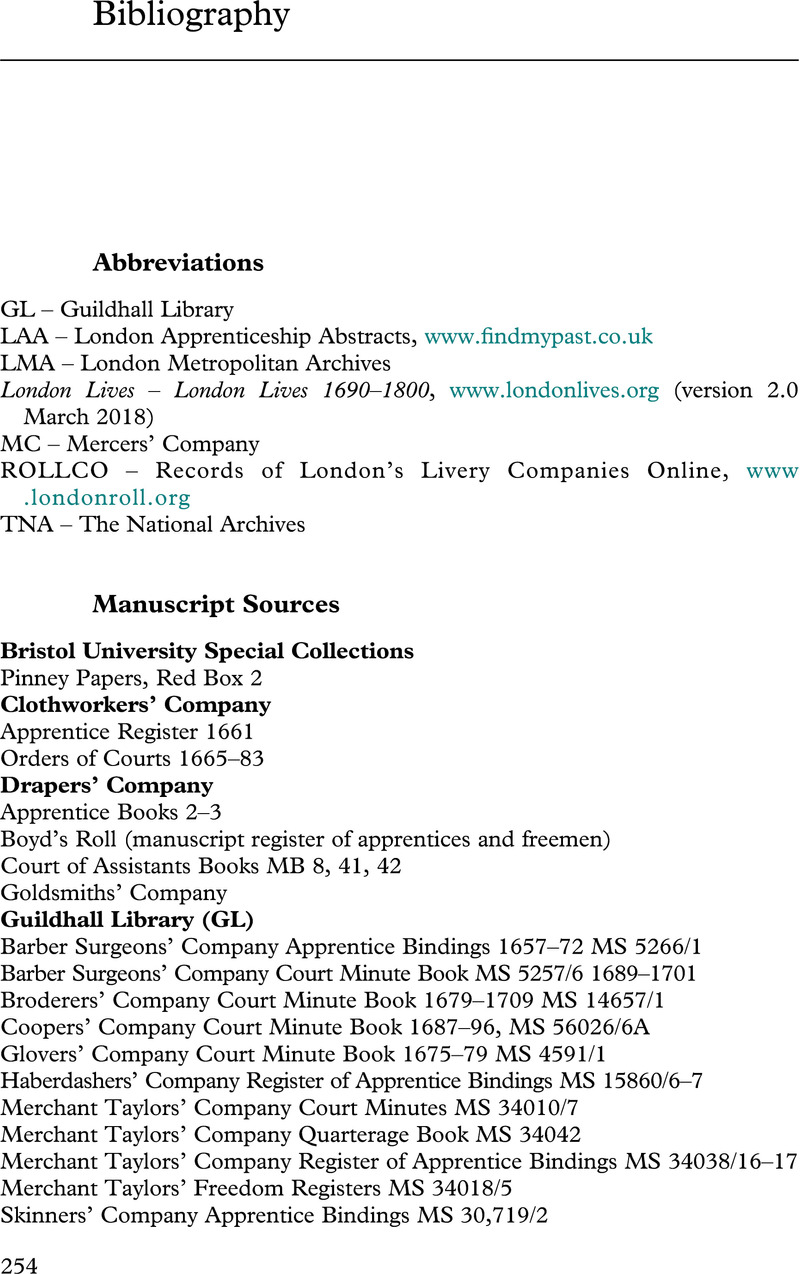

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 November 2021

- Ingenious Trade

- Ingenious Trade

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Bred in the Exchange: Seamstresses and Shopkeepers

- 2 Girls as Apprentices

- 3 Managing the Trade: Women as Mistresses

- 4 What Girls Learned

- 5 Making Havoc: Discipline, Demeanour and Resistance

- 6 Freedoms and Customs

- Conclusion

- Appendix Who’s Who

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Ingenious TradeWomen and Work in Seventeenth-Century London, pp. 254 - 268Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021