7.1 Introduction

Many scholars have noted similarities between Italic (Chapter 8) and Celtic (Chapter 9). Reference SchleicherSchleicher (1858) was the first to posit an Italo-Celtic node between Proto-Indo-European and Celtic and Italic.Footnote 1 But in the 1920s Carl Marstrander and Giacomo Devoto questioned the validity of this subgrouping.Footnote 2 Scholarly opinion has varied ever since. It would be fair to say that Italo-Celtic is more debatable than any other higher order subgrouping, certainly much more so than Balto-Slavic.

7.2 Evidence for the Italo-Celtic Subgroup

Many features once cited in favor of Italo-Celtic unity are now seen to be archaisms. For example, the medial r-endings (Lat. sequitur ~ OIr. sechithir ‘follows’) were in the nineteenth century only known from Italic and Celtic, but the appearance of these endings in in Anatolian (Hitt. mid.3sg. -ttari), and Tocharian (Toch.B mid.3sg. -tär/-trä) completely changed this picture. It is true, however, that it is only in Italic and Celtic that -r becomes a marker of middle diathesis, and only Celtic and Latin have created a mid.1pl. *-mor.Footnote 3 In the other branches continuing *‑r the suffix is limited to the primary middle endings only: Hittite prim. -ttari : sec. -ttati; Toch.B prim. ‑tär : sec. -te.Footnote 4 Another feature now known to be an archaism is the t-less 3rd singular medial endings: OIr. berair ‘is carried’, Umb. ferar subj.mid.3sg. These forms are matched by Hitt. ‑ari (ēšari ‘sits’) and relics in Vedic (áduha[t] ‘gave milk’). Of course, archaisms like this do not provide positive evidence for subgrouping, but they aren’t completely uninteresting either. In the case of the primary marker *-r, we may note that the nearest groups to the east, Proto-Germanic, Proto-Balto-Slavic, Albanian, and Greek have all taken part in the innovation of replacing primary middle -r with primary active -i (e.g. Goth. haitada ‘is called’ < *-otoi̯, Arc. Gr. ‑τοι). The fact that the two most westerly branches escaped this innovation may not be fortuitous.Footnote 5

In the realm of phonology there are a small number of innovative features that have been proposed as shared Italo-Celtic developments, but these are all problematic.

Both Italic and Celtic agree in the development of *CR̥HC to CRāC : Lat. grānum ‘a grain’ < *g̑r̥hₓnom vs. Goth. kaurn < PGmc. *kurna-,Footnote 6 OIr. lám ‘hand < *pl̥h2meh2, but this apparent isogloss is complicated by fact that both Italic and Celtic show other outcomes for this sequence. In Italic *CR̥HC becomes CaRaC under the accent, e.g. palma ‘palm of the hand’ < *palama < *pĺ̥h2meh2 (see Reference HöflerHöfler 2017). In Celtic the outcome CRaC is found in a number of examples, which cannot be easily explained as morphological neo-zero-grades, e.g. OIr. flaith ‘rule’, MW gwlat ‘country’< *u̯l̥hₓti-.Footnote 7 It is difficult therefore to believe that the resolution of *CR̥HC sequences happened in Proto-Italo-Celtic. Note in particular the disagreement between MW gwreid ‘roots’ < *u̯radī < *u̯r̥hₓdih2 and the morphologically nearly identical Lat. rādīx ‘root’.

A famous isogloss that does seem to hold up better is the long-distance assimilation of *p … kʷ > *kʷ … kʷ seen in Lat. quīnque, OIr. cóic, OW pimp ‘five’ < *kʷenkʷe < *pénkʷe.Footnote 8

Latin quercus ‘oak’ < *kʷerkʷu- < *perkʷu- (cf. Langobardic fereha ‘aesculus’, Goth. faírguni neut. ‘mountain’) seems to show that in Italic the assimilation *p … kʷ >*kʷ … kʷ preceded the change of *kʷu > *ku. But the Celtic place-name Hercynia ‘oak forest’ < *perkunia seems to show that in Celtic the *kʷu to ku change preceded *p … kʷ > *kʷ … kʷ. Since there was no *kʷ to trigger dissimilation *p developed regularly to ∅. This relative chronology, taken at face value, suggests that the Italic and Celtic long-distance assimilations were independent changes. If, however, the dissimilation of *kʷu- to *ku- occurred already in Proto-Indo-European, as is likely, then one might suppose that the labiovelar had been analogically restored from an oblique stem form *perkʷeu̯- in the dialects ancestral to Latin, in which case no inference about differing relative chronologies of the sound changes can be drawn.Footnote 9

In my 2009 book, I entertained the possibility that Italic and Celtic shared the change of *ū to *ī before yod, sometimes called Thurneysen’s Law. But Reference Zair, Jamison, Melchert and VineZair (2009) has shown that the Celtic facts are amenable to a different interpretation. The Old Irish word for ‘smoke’ dé, gen. diad must go back to an immediate preform *diots, gen. diotos with a short i from earlier *dʰuh2i̯ots, *dʰuh2i̯otos. Zair explains this as *uhₓiV- > *uiV > *iyV-. Reference Fortson, Klein, Joseph and FritzFortson (2017: 838) argues therefore that Thurneysen’s Law is a different phenomenon. But the whole complex of facts deserves more discussion than we can give it here. I limit myself to two observations. First, the forms of the verb ‘to be’ with an ī reflecting *bʰuhₓ-i̯e- cannot be explained by an Italo-Celtic rule (Lat. fiō, Osc. fiíet, OIr. biid, but MW byd points to a short *i) because these forms are also found in Germanic and Balto-Slavic (OE consuetudinal present bið, Lith. pret. 3ps. bìt(i), OCS conditional bi).Footnote 10 Second, while Latin is uninformative about the vowel quantity in prevocalic position, the Sabellic cognates of pius point unambiguously to a short i (Umb. pehatu, Pael. pes etc.).Footnote 11 This raises the possibility that the development in Italic, like Celtic, was by way of a short vowel.

In the realm of morphology we may note first the thematic genitive in *-ī : Ogham Ir. maqqi ‘son’, Gaul. segomari ‘Segomaros’, Lat. aiscolapi ‘Aesculapius’.Footnote 12 Although the building blocks of the *-ī genitive appear to be Proto-Indo-European (see Reference WeissWeiss 2020a: 204), the complete integration into the thematic nominal paradigm is uniquely Italic and Celtic. And yet this cannot have been a Proto-Italo-Celtic innovation. It is clear that the replacement of the inherited thematic gen.sg. *-osi̯o happened in the individual Celtic and Italic languages. VOL *-osio is well represented in Satrican valesiosio and in Faliscan euotenosio. Lepontic -oiso is a probably transformation of *-osi̯o under the influence of the pronominal gen.pl. *-oi̯sōm. This means that Latin and Celtic in the historical period have independently replaced an inherited ending with the same piece of morphology. This could hardly be a contact phenomenon.Footnote 13 Most scholars agree that the origin of the -ī genitive is to be sought in the so-called vr̥kī́ḥ suffix *-ih2, which makes substantives with genitival meaning from thematic nouns. The question then arises what function could the vr̥kī́ḥ suffix have acquired in Italic and Celtic that made it a favorable candidate for eventually replacing the inherited thematic gen.sg.? Answering this question is difficult because we have no attested textual evidence from Italic or Celtic showing both the inherited genitive and the vr̥kī́ḥ suffix. A necessary mid-stage for the transformation of the vr̥kī́ḥ suffix-forms, which are substantives in Indo-Iranian, into an adnominal case form would be their use as adjectives. This would be another instance of the so-called weak adjective phenomenon in which an original substantivized form becomes an adjective. Could the reinterpretation of the vr̥kī́ḥ suffix-forms as adjectives be the shared Italo-Celtic innovation that laid the groundwork for the eventual independent emergence of the ī-genitive?

The ā-subjunctive: OIr. ·bera ~ Lat. ferat ‘carry’. Both Italic and Old Irish display a morpheme ā used to form the subjunctive.Footnote 14 In Latin this makes the subjunctive to thematic present stems, but relic forms of Old Latin and Sabellic show derivation from the root (advenas, atulas, Umb. neiřhabas). This must represent an old pattern. In Old Irish the a-subjunctive is formed to weak presents and strong presents ending in b, r, l, m, and n plus agaid.Footnote 15 Class S 3 (nasal infix presents to seṭ root) affix the suffix to the root with no nasal infix (benaid ~ bia). There are two schools of thought on the Italo-Celtic or Italic and Celtic a-subjunctive. One view, the traditional one, identifies the morphemes of the two language families. The other view, originating with Reference Rix and SchmidtRix (1977) and significantly improved by Reference McConeMcCone (1991), derives the Insular Celtic a-subjunctive from *‑ase-, either the desiderative morpheme *-h1se- (Rix) or s-aorist subjunctive morpheme added to laryngeal final roots (McCone). The advantage of the McCone view is that it allows both Old Irish subjunctives to be derived from a single Proto-Indo-European category. But the disadvantage is that the starting point for the a-subjunctive on this hypothesis would be the s-aorist subjunctive built to seṭ roots; such a category, which is very sparsely attested in other Indo-European languages, would have to have become very successful in the prehistory of Celtic.

The superlative formant *-ism̥mo-: OIr. tressam ‘strongest’ < *treksisamos, MW hynaf ‘oldest’ < *senisamos, Lat. maximus ‘greatest’ < *magisVmos, Pre-Samnite ϝολαισυμος ‘best’ (see Reference Cowgill, Cardona, Hoenigswald and SennCowgill 1970). Even strong opponents of Italo-Celtic like Marstrander admit the strikingness of this agreement. Reference MarstranderMarstrander (1929: 246) wrote:

Une forme tout à fait identique comme irl. nessam, osque nessimo- doit provenir d’une même source primitive; on ne saurait guère admettre qu’elle se soit développée indépendamment dans les deux langues. Mais il n’en suit pas nécessairement qu’elle ait pris naissance à un époque d’unité italo-celtique.

[An absolutely identical form like OIr. nessam, Osc. nessimo must derive from the same original source; it would hardly be possible to accept that it had developed independently in the two languages. But it does not necessarily follow that it arose in an era of Italo-Celtic unity.]

Marstrander thought the proto-form of the superlative suffix was *-sm̥mo- and of “haute antiquité” [“remote antiquity”], hence a shared inheritance. But we know today, thanks to Warren Cowgill, that the proto-form was in fact *-ism̥mo- and it is certain that *-ism̥mo- replaces the earlier superlative formant *-isto- continued by Greek, Indo-Iranian, and Germanic, which was inherited into Italic as traces like iuxtā ‘nearest’ and probably ioviste ‘youngest’ and sōlistimus ‘most favorable’ show.Footnote 16 Furthermore *-isto- could have been remade as *‑ism̥mo- under the influence of the well-attested suffix superlative *‑m̥mo-, which is normally added to pronominal and adverbial stems. But on what basis could a theoretical archaism *‑ism̥mo- be remade to *-isto-, since the suffix -to- would not otherwise occur as a superlative formant? The superlative formant *-ism̥mo- seems the strongest argument for Italo-Celtic. It should be noted, by the way, that the same formant is continued in (para-)Venetic (venixema from Emona), but this is unproblematic if one believes, as I do, that Venetic was an Italic language.

Primary 3rd person middle endings *-tro, *-ntro: OIr. do.moinethar ‘thinks’, Umb. herter ‘should’ < *her(i)tro.Footnote 17 The ending *-ntro results from a contamination of *-ntor and *-ro and the innovation spread from the 3rd plural to the 3rd singular. This innovation did not succeed in completely ousting *-tor and *-ntor in either Italic or Sabellic. In any case, there is no evidence for this contamination elsewhere in Indo-European.

At a much lower level of importance are the many shared lexical items, since content words can be easily borrowed. Nevertheless, some of these items show striking morphological and semantic specializations. Some examples follow.

Lat. crispus ‘curly’, MW crych, Gallo-Lat. PN Crixsus continue a proto-form *kripso- from the root *krei̯p- ‘turn’ found also in Balto-Slavic (OCS krěsъ ‘solstice’, Lith. kreĩpti ‘to turn’). The Italic, Celtic, and Slavic forms presuppose an s-stem *krei̯pos ‘turning’. In Proto-Italo-Celtic the s-stem made a thematic derivative, which, in the most archaic fashion, triggered a double zero-grade of the pre-suffixal stem. The meaning ‘having turning’ was specialized to ‘curly’ and ‘wrinkled’, both meanings attested in Welsh and Latin.Footnote 18

Lat. dēses, dēsidis ‘lazy’, ‘inactive’, OIr. deeid < *de-sed(i)-. The Latin adjective, which is not attested before Livy, has been suspected of being backformed from dēsidia ‘idleness’ (Plautus +), but the close match with the Irish adjective makes this unlikely. The Irish and the Latin form presuppose a semantic development *de/deh1 + *sed- ‘to remain seated’ (cf. Lat. dēsideō) > ‘to be idle’.

Lat. saeculum ‘lifespan’, MW hoedl ‘lifetime’ < *sai̯tlom < *seh2itlom, Gaul. deae setloceniae < *sai̯tlokei̯nii̯o- ‘goddess of long life’ (cf. OIr. cían ‘long’). This match is perfect and, if correctly derived from the root *seh2i- ‘bind’, shows a striking semantic development. The oldest recoverable meaning for both hoedl and saeculum is ‘lifespan’. Thus in early Rome, according to Etruscan belief, a saeculum extended from some important date like the founding of Rome until the last person alive at that initial time died. This meaning could have arisen from the idea of a binding knot, marking the ends of life. Cf. Ved. párur- ~ párvan- which means ‘a knot’, ‘a limit’ and also ‘a fixed period of time’.

Lat. dē ‘down from’, OIr. di, OW di. This preposition, probably the instrumental *deh1 of a pronominal stem *do-, has no precise matches outside of Italic and Celtic. Though just a little word, *deh1’s import is considerable since it is part of a relatively small set of quasi-functional prepositions.

Lat. Sēmō, a god of the oath often associated with Hercules, and Osc. seemún- match Gaul. Segomon-, an epithet of Mars. These forms converge on a Proto-Italic epithet *seg̑ʰo-mō, -mon- ‘strong-man’, a secondary -mon-stem from a thematic stem *segʰo- ‘strength’ (MIr. segh). The form *seg̑ʰo-mō seems to have been a divine epithet found nowhere but in Italic and Celtic (see Reference WeissWeiss 2017a).

Whether one recognizes an Italo-Celtic node or not, the fact remains that Italic shares more innovative features with Celtic than with any other branch.Footnote 19 Nevertheless, it should not be forgotten that both Italic and Celtic individually and in common share many features with Germanic. This connection is not surprising given their geographical positions (see Reference WeissWeiss 2020a: 500–1). Somewhat more surprising are some striking agreements between Italic and/or Celtic and Indo-Iranian, famously highlighted by Vendryes. The phylogenetic import of these agreements is still unclear (see Reference Weiss, Serangeli and OlanderWeiss 2020b).

7.3 The Position of Italo-CelticFootnote 20

The relationship of Italo-Celtic to the rest of Indo-European can be conceived of as the answer to three questions. (1) Was Proto-Italo-Celtic the next clade to separate from the PIE tree after the separation of Proto-Tocharian? (2) How do we interpret the extensive lexical matches between Italic, Celtic, and the other northern Indo-European branches, Germanic and Balto-Slavic, the so-called vocabulary of the northwest? (3) What do we make of the striking matches, especially in the religious and legal lexicon, shared by Italo-Celtic and Indo-Iranian?

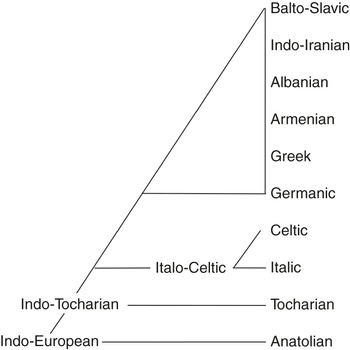

That Proto-Italo-Celtic was the next group to branch off after Proto-Tocharian has been supported by some computational phylogenies of Indo-European (see Figure 7.1) but not others.Footnote 21 To show that Proto-Italo-Celtic was the next to branch off would require demonstrating the existence of innovations shared by all the other non-Anatolian, non-Tocharian branches that are not found in Proto-Italo-Celtic. The best candidate for an innovation of this sort is the thematic optative *-o-i̯h1- of which there is no certain trace in Italic or Celtic, while it is well represented, or at least traceable, in Germanic, Balto-Slavic, Indo-Iranian, Greek, Armenian, Phrygian, and Messapic.Footnote 22 In place of the thematic optative, on the view followed here, Italic and Celtic show the *ā-subjunctive. Another possible innovation of the inner branches is the replacement of the primary middle marker *-r by *-i, which is seen in Greek, Phrygian,Footnote 23 Indo-Iranian, Germanic, Albanian, and possibly Balto-Slavic. These two potential isoglosses seem to constitute the total evidence for innovations not reaching Proto-Italo-Celtic.

Figure 7.1 Tentative tree showing the position of Italo-Celtic

At the same time, it is clear that Proto-Italo-Celtic was in close contact with the rest of the northwestern Indo-European branches. Reference MeilletMeillet (1922) famously identified a long series of lexical items shared between Italic, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic, and Slavic that found no matches in the other IE languages (cf. also Reference Oettinger, Bammesberger and VennemannOettinger 2003). With greater knowledge of Anatolian, Tocharian, and the later Iranian languages, some of these supposedly exclusive items must be reevaluated. For example, the root *seh1- ‘sow’ (Lat. sēmen ‘seed’, OIr. síl, OHG sāmo, OCS sěmę ‘seed’, Lith. sė́ti ‘to sow’) now has a cognate in Hitt. šāi, šiyanzi ‘to press’. The item *seh1- must be reconstructed for highest node PIE, but the specialization to ‘sow’ is still only found in the northwest. On the other hand, Meillet’s example *pork̑os ‘piglet’ (Lat. porcus, OHG farah, Lith. par̃šas, CS prasę) is no longer valid since a cognate is attested in Iranian (YAv. parsa-, Khot. pāsa, etc.).

Nevertheless, there are still many items with a northwestern distribution. Some of these might be common or independent borrowings from substratal languages. This scenario is especially plausible for the names of flora and fauna. An example of this sort might be ‘alder’. The cognates for this word show a remarkable amount of formal variation that is difficult to trace back to exclusively Indo-European morphophonology: Lat. alnus < *alsno-; PGmc. *alisō (ODu. elis in place-names; MDu. else, Sp. aliso) ~ *alizō (OHG elira) ~ *aluz- (ON ǫlr, OE alor); Lith. alìksnis al̃ksnis, el̃ksnis; PSl. *olьxa (Ru. ol’xá) ~ *elьxa (Ru. dial. elxá, Bulg. elxá) ~ *olьša (Cz. olše) ~ *eliša (SCr. jȅlša). Cf. Basque haltz. The word may, however, also show up in Macedonian ἄλιζα (Hsch.) glossed as ‘poplar’.

Two terms relating to agricultural technology with somewhat overlapping meanings are (1) *l(V)i̯hₓseh2 ‘furrow, track’ (Lat. līra ‘furrow’ < *lei̯hₓseh2; OPr. lyso ‘field’ < *lihₓseh2, cf. Lith. lýsė <*lihₓsii̯eh2; OCS lěxa ‘row’, OHG -leisa ‘track’ <*loihₓseh2Footnote 24) and (2) *polk̑eh2 ‘ploughed piece of land’ (OE fealh ‘ploughed land’, Gaul. *olca ‘arable land’ (Gregory of Tours olca, OFr. ouche, Port. olga), ORu. polosá ‘strip of land’). In Latin, Germanic, and Slavic the root *plek̑- ‘plait’ has acquired a -t-extension: Lat. plectere, OHG flehtan, OCS pletǫ. Contrast the unextended *plek̑- in Lat. ex-plicere and Gk. πλέκω. A piece of military technology is reflected by the word for ‘shield’: Lat. scūtum, OPr. staytan for *skaitan < *skoi̯tom vs. OIr. scíath, MW ysgwyd, OCS štitъ < *skei̯tom.

There are a number of words relating to social structure. Most famous is the word *teu̯teh2 ‘people’ (Osc. touta, Goth. þiuda, OIr. túath, Lith. tautà). And in quasi-opposition to *teu̯teh2 is *gʰostis ‘guest-friend’ (Lat. hostis, Ven. hostihauos, Goth. gasts, OCS gostь). From the legal sphere we have *dʰelgʰ- ‘owe’ (OIr. dligid ‘is owed’, OIr. dliged ‘law’, Goth. dulgs ‘debt’, OCS dlъgъ ‘debt’, though the Slavic forms might be a loan from Gothic) and *u̯adʰ- ‘surety’ (Lat. vas, vadis, Osc. vaamunim ‘vadimonium’ < *u̯afemōnii̯om, Goth. wadi ‘pledge, surety’, Lith. vãdas ‘surety’ (obsolete)).Footnote 25

Finally, it’s been observed since Reference VendryesVendryes 1918 that Italo-Celtic and Indo-Iranian share a number of culturally important words relating to the religio-legal sphere not occurring in the intervening languages. The most notable of these are the words *h3rēg̑s ‘rule’, ‘king’ (OIr. rí, Lat. rēx, Ved. rā́ṭ) and *k̑red(s)-dʰeh1- ‘to trust’, lit. ‘place heart’ (OIr. creitid, Lat. crēdere, Ved. śraddhā́ ‘trust’). Vendryes regarded these agreements as archaisms that were discarded in the intermediate languages, but it is striking that the supposed archaic status of these items is not confirmed by evidence from Proto-Anatolian or Proto-Tocharian.Footnote 26