In January 2016, Father Esteban Velazquez crossed the border between Morocco and Melilla. A Jesuit priest, Padre Esteban, as he was known to many, had been living and working for three years in Nador, where he had been coordinating a humanitarian project implemented by a Catholic organisation and funded by Switzerland. Along with a team of eight collaborators, Padre Esteban provided migrant people with emergency medical assistance, food parcels, clothes, and other small hygiene and shelter resources – forms of basic support that migrants relied on to survive the difficult living conditions in the forest camps. Padre Esteban complemented his humanitarian work by vocally criticising the violence unleashed by Moroccan and Spanish authorities against migrants in the borderlands. In an interview he granted to the Spanish newspaper Publico, he declared that his team “had seen everything”, including “mandible fractures, smashed heads, lost eyes and also deaths” (Público 2016).

The Spanish press reported that Padre Esteban was under the constant impression that someone was watching him, following him, listening to his conversations. For three years, however, he managed to juggle his advocacy and humanitarian work, continuing to provide emergency care for migrant people brutalised at the border. But when he attempted to return to Nador in January 2016, Moroccan policemen stopped him at the border post in Beni Ensar. Claiming that his residency permit was no longer valid, they prevented him from re-entering the country. While Moroccan authorities did not publicly announce the reasons for this entry ban, the local Moroccan press reported that Padre Esteban was suspected of Christian proselytism. However, there is common agreement among aid workers and human rights activists that Padre Esteban was prevented from returning because of his outspoken advocacy. “Maybe he said something that bothered someone”, an anonymous source suggested in an interview to the Spanish newspaper Eldiario (Eldiario.es 2016).

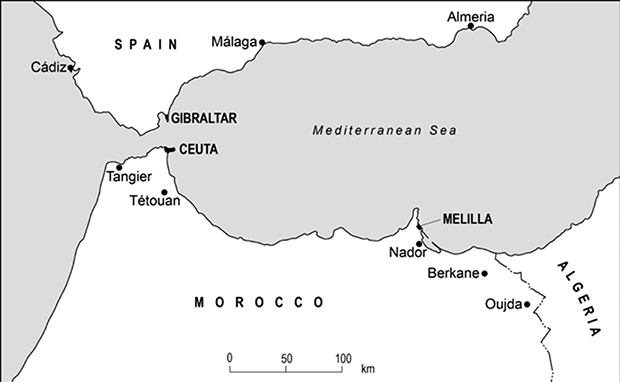

Since the early 2000s, humanitarian organisations have been providing emergency assistance to migrants stranded in the Moroccan borderlands, in particular in the area of Oujda and Nador, and, to a lesser extent, in the forests surrounding the Spanish enclave of Ceuta and in the city of Tangier. For twenty years, the violence unleashed by police forces and border infrastructure has forced migrant people into unbearable living conditions, which humanitarian organisations manage to relieve only marginally. But even this marginal relief is difficult to implement in the borderlands. The repression experienced by Padre Esteban is symptomatic of the inconvenient position occupied by humanitarians at the border. The closer to the fences, the more emergency work has to be conducted under the watchful eyes of Moroccan authorities. State surveillance monitors and obstructs humanitarian activities to prevent humanitarians from speaking out about violence against migrants. For three years, Padre Esteban infringed the unwritten rule regulating humanitarian presence in the borderlands: “if you stay, you shut up” (IRIDIA et al. 2017, 65).

This chapter investigates the uneasy place that aid-funded humanitarian projects inhabit in the governance of the frontier. In the areas surrounding the Spanish enclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, sovereign authorities deploy a violence against people racialised as ‘sub-Saharan migrants’ that has no equal in the rest of the country. Migrant life in the borderlands is thus subjected to power in its most explicit deductive form – a power that actively inflicts pain, coerces bodies, kills, and lets die. The ferocity of border containment changes the way NGOs and IOs operate. Rather than focusing on implementing integration projects, humanitarian organisations working at the border limit themselves to a form of limited assistance, that could be qualified as “minimal biopolitics” (Reference RedfieldRedfield 2013, 21). Minimal biopolitics does not aim at revolutionising the status quo by spurring people’s life and potential. Rather, it aims at mitigating death in a punctual, temporary way, that does not at all challenge the structural degradation of migrant existence at the border (Reference WilliamsWilliams 2015).

The elusiveness of border containment power plays out through the minimality of aid-funded assistance: aid reduces the chances of death without necessarily fostering the possibilities of migrants’ life. Border containment power is not necropolitical or spectacular. It is minimal: it assists migrants at the margins, without moving them away from the margins (Reference WilliamsWilliams 2015). In the Moroccan borderlands, much of that minimality depends on the fact that the very presence of humanitarians in the borderlands lies, somehow, suspended: aid sustains a threatened apparatus of minimal biopolitics, whose presence is constantly at risk of expulsion. In this chapter, however, I will show that humanitarians react differently to the threat of sovereign authorities. Some decide to speak out. Others, instead, decide to stay silent. Aid, I will show, tends to support a threatened and silent apparatus of minimal biopolitics that operates with discretion, and which privileges presence on the ground over denouncing state-sanctioned abuses against migrants.

Discussing the workings of aid-funded humanitarian projects is not possible without exploring the broader history of humanitarian borderwork in the Moroccan North-East. First, donors’ appearance in the borderlands only dates back to the late 2000s. Until that point humanitarian provision in the area was mostly covered by MSF and by Moroccan grassroots organisations. Second, aid-funded NGOs and IOs capitalised on the work of MSF, which supported other organisations in visiting and establishing a presence in the borderlands. To the best of my knowledge, MSF did not receive direct funding from European state donors during the operation of its humanitarian projects in the borderlands, although it did collaborate and interact with aid-funded organisations. Throughout the chapter, I regularly alternate references to the work of MSF and data related to the work of aid-funded NGOs and IOs to highlight the continuities and interruptions characterising the shift between humanitarian work conducted by activist organisations and aid-funded actors.

The five sections of this chapter dissect this minimal biopolitical system by analysing its conditions of existence, rules of functioning, and points of fracture. The first section explores the conditions within which humanitarian work exists by tracking patterns of violence against migrants at the Spanish–Moroccan border. The second and third sections explore the rules which guide the functioning of border humanitarianism. Building on the work of Michel Agier, the second section uncovers the symbiosis between humanitarians and border violence. It explores how humanitarians alleviate a form of suffering that is produced, sustained, and regularly reproduced by the border itself. The third section continues this reflection by focusing on the coexistence of humanitarians and the state in the borderlands. The fourth and fifth sections investigate the points of rupture of minimal biopolitics. I do this by exploring the factors that undermine the precarious existence of the humanitarian system. The fourth section focuses on the challenging relation between humanitarianism and border crisis. Prolonged crisis constantly triggers the need for humanitarian action, while also exposing humanitarian incapacity to implement transformative change. The last section unravels the tension between humanitarian presence and duty to bear witness. It explores how pervasive policing and authoritarian repression oblige humanitarians to choose between operating transformative action and maintaining access to the field.

Violence as Migration Control

Humanitarians operate in a border environment characterised by pervasive violence. At the Spanish–Moroccan border (see Map 2), like in other critical crossing points in the world, the endangerment of life is a structural component of migration containment (see Reference Slack, Martínez, Lee and WhitefordSlack et al. 2016 for an example of the US–Mexico border). The tightening of European borders has progressively transformed the borderlands into a space governed through practices which are in open violation of national and international law. In a report compiled in 2013, MSF argued that in 2012 alone its staff assisted 600 people who had been injured at the border between the Moroccan city of Nador and the Spanish enclave of Melilla. MSF patients had either been directly injured by Spanish and Moroccan border guards or were victims of “indirect violence, generally sustained as sub-Saharan migrants ran and fell trying to escape arrest during raids or fell or cut themselves on the barbed wire covering the multiple fences separating Nador and Melilla” (MSF 2013c, 15). The number of victims of border violence is however likely to be much higher. Data provided by humanitarian and human right groups, in fact, only shed light on the number of people who sought assistance, not on the number of people actually injured (MSF 2013b).

Map 2 Map of the North of Morocco.

After the announcement of the new migration policy in 2013, police discontinued the generalised harassment of migrants and refugees in most areas of the country – at least until the summer of 2018. In the borderlands, however, time appears to have stood still. In particular, in the cities and forests surrounding the Spanish enclave of Melilla, police forces still carry out a policy of institutionalised deterrence of the migrant presence (AMDH Nador 2019). Mass arrests and practices of “infrastructural warfare” (Reference GrahamGraham 2002) currently conducted by Moroccan authorities do not differ from the abuses characterising the period preceding the announcement of the new migration policy. Arbitrary arrests of migrants venturing into the city further restrict migrants’ freedom of movement. This politics of institutional harassment, generally circumscribed to the area of Nador, sometimes extends to the city of Tangier (Reference LemaiziLemaizi 2018). As an aid worker told me in an interview, “it is like if they [Moroccan authorities] were saying ‘you can’t stay here, go somewhere else because we know that if you come here, it’s because you want to cross [to Spain]’”.Footnote 1

Drawing on its work with migrant communities, the NGO Caminando Fronteras estimated that between September 2015 and December 2016 at least “2,213 people were victims of forced displacement, 569 were victims of devoluciones en caliente (summary deportations), 739 were injured due to the violence exercised by [Spanish and Moroccan] security forces, and 6 people lost their life” at the Ceuta and Melilla borders (Caminando Fronteras 2017, 39, translation by author). The borderlands have therefore become a space of exception not only to the rule of law, but to the tolerance towards migrants that (at least between 2013 and 2018) seemed to have become the norm in the rest of the country.

In the borderlands, migrants are stripped of all rights, their life becomes expendable, their abusers go unpunished (Reference AgambenAgamben 1998). Such lethality is not only perpetrated through destruction, but through a purposeful abandonment of migrant people to dangerous environments, where racialised life is exposed to “an unconditional capacity to be killed” (Reference WilliamsVaughan-Williams 2015, 65). The drive for migration control and the Euro–Moroccan cooperation on the matter has therefore normalised ultra-violence as a mode of power, which transforms the borderlands into no-go areas for black people on the move.

Humanitarianism and Border Violence

Humanitarianism works in symbiotic relation to border violence. Migration control creates the conditions that allow the emergence of humanitarian missions and defines the margins of everyday humanitarian action. The normalisation of migrants’ precariousness at the frontier has led to the rise of a “humanitarian border”, a complex system of discourses and practices that govern the frontier by “compensating for the social violence embodied in the regime of migration control” (Reference Walters, Bröckling, Krasmann and LemkeWalters 2010, 139).

The rise of the humanitarian border in Morocco dates back to the early 2000s. MSF started its first migration project in Tangier in 2003, and worked with the population of migrants living in the medina of the city and in the forests surrounding the Spanish enclave of Ceuta (MSF 2005). In 2004, the NGO expanded its activities to the Moroccan region of the Oriental, in the areas of Oujda, Berkane, and Nador, and in 2007 also to the large coastal cities of Rabat and Casablanca (MSF 2010, 2013a). Over the years, multiple humanitarian actors have first worked alongside and then substituted MSF in the assistance of migrants stranded in the North-Eastern borderlands, including Moroccan NGOs, international and faith-based organisations, and the IOM. After MSF decided to leave the country in 2013, its project was taken over by an international medical NGO and by a Catholic organisation – the latter coordinated by aforementioned Padre Esteban in Nador between 2013 and 2016 (Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes España n.d.). The project was coordinated by the IOM and funded by Switzerland (OIM Maroc 2014). After 2015, the two charities continued the project without the involvement of the IOM.Footnote 2 The IOM, however, continued operating in the area in partnership with other Moroccan NGOs (see OIM Morocco 2017). From the late 2000s until 2019, Switzerland was by far the most engaged donor in funding humanitarian assistance to migrants stranded at the borderlands, with other actors (such as the EU, the Spanish Decentralised Cooperation, Finland, USAID, and Denmark) having had a much more dispersed and volatile presence.

Border violence creates the conditions which activate the need for humanitarians’ minimal biopolitics. Humanitarianism has historically had a symbiotic relationship with the causes of suffering that emergency workers attempt to alleviate (Reference RedfieldRedfield 2013). Agier qualifies humanitarianism as “the left hand of the empire”: humanitarians, in fact, operate in symbiosis with warfare to reinforce imperialist hegemony over other parts of the world (Reference AgierAgier 2003). As in most other emergency settings, humanitarian organisations in the Moroccan borderlands operate as a left hand of the border. They engage in a sinister symbiosis with the migration control apparatus by treating victims of both slow and fast violence (see Reference NixonNixon 2011; Povinelli 2011). In reports compiled by MSF, the organisation argued that an extremely high share of the migrants that it treated were victims of police assault or had been injured trying to jump over the fences put in place to protect European borders. The first report compiled by MSF in 2005 argues that “23.5% of the people treated in Tangier, Nador and Oujda, medinas, outskirts (such as Mesnana) and forests (Bel Younech, near Ceuta, and Gourougou, near Melilla), were direct or indirect victims of violent acts”. The report then specified that two-thirds of the victims of violence that the MSF team was treating had been attacked by either Spanish or Moroccan border guards:

Many of the sub-Saharan immigrants who come to our medical teams for treatment for these injuries state that their assailants were institutional or governmental officials from Morocco and Spain. Our patients say that they have been victims of an excessive use of force in addition to humiliating and cruel treatment whilst being detained or chased by certain members of the Moroccan security forces (SF) and the Spanish security forces in Ceuta and Melilla. […] The distribution of violent acts committed against ISSs [Irregular sub-Saharans] is somewhat uneven with the security forces of both countries accounting for over 65% of cases, whilst criminal groups and human trafficking networks represent almost 30%.

In a report published in 2010, the organisation highlighted that one-third of the women interviewed had been victims of sexual violence in Morocco, especially at the Algerian–Moroccan border (MSF 2010). Another publication released by the organisation in 2013 argued that “precarious life conditions” and “criminal and institutional violence” were the main causes of the medical cases that MSF staff were treating (MSF 2013c, 3). To date, not much has changed. As an aid worker put it poignantly during an interview in 2016:

He [an officer of the EU Delegation in Rabat] asked about the main problems that migrants have in Nador. I told him that already if they [the Spanish and Moroccan police] stopped beating them [the migrants], it would be already a lot. […] but it is not just the police, it is the fence that kills them […]. The fence is composed of three lines of barbed wire, which has been declared illegal by Europe, so what did they do? They put it on the Moroccan side of the border. This barbed wire cuts deeply into the skin, and it is produced in Malaga ….Footnote 3

The symbiotic relation that humanitarians entertain with border violence also conditions the kind of support that emergency workers can provide to stranded migrants. Humanitarians, in fact, have to adapt project activities and working logistics to the undignified conditions and constant state of alert in which migrants have to live. Prevented from moving freely around Nador, migrants are forced to hide in the forests surrounding the city – wooded areas where living conditions are extremely precarious, especially in winter. All the activities planned and implemented by humanitarian organisations are conceived to allow migrants to better cope with these undignified conditions, to allow life to be “minimally managed under the persistent shadow of possible death” (Reference WilliamsWilliams 2015, 18). The content of the humanitarian kits distributed by humanitarian organisations were meant to facilitate their survival in the forests surrounding Nador: tarpaulins to build shelters, hats and gloves to cope with cold winter weather (MSF 2013c), and jackets and blankets to migrants living in the forest camps.Footnote 4 The content of the kits was also modified to allow migrants to better cope with the violent policing methods adopted by Moroccan authorities. This emerges very clearly in this interview with a former humanitarian officer, who explained that his organisation decided to start distributing winter jackets rather than just blankets for pragmatic reasons:

At the beginning, we would just distribute blankets. But at every raid in the forest the police would burn down migrants’ shelters, including the blankets. […] So, we started distributing jackets as well. When they [the migrants] ran away from the police, at least they could run away with the jacket. [interview, former humanitarian officer, WhatsApp, October 2017]

Throughout the past fifteen years, migrants have consistently needed NGO assistance to physically visit healthcare facilities in border areas.Footnote 5 The harsh conditions and the constant state of anxiety endured by migrants in the forest provoke mental health problems that NGO psychologists barely manage to address. The psychological impact of border violence is so extreme that it can make migrants ineligible even for the most ambiguous form of care available to them in Morocco: voluntary return. As a humanitarian worker told me in 2017:

The more they [migrants] live in the forest, the more psychological problems they have, because they constantly live in a state of alert and at some point they completely crash …. We have the case of a woman that became completely schizophrenic, but we cannot give her accommodation for very long term, and she cannot stay in the forest … I came to talk with the IOM to see if she could at least benefit from voluntary return, so to stay with her family rather than going to a psychiatric hospital here [in Morocco] … but they said she will probably be declared unfit to travel, if she has this sort of severe psychological problems.Footnote 6

The risk of arbitrary arrest and limited freedom of circulation experienced by migrants in Nador shapes how humanitarian organisations deliver assistance to migrants and refugees. To minimise the risk of arrests, humanitarian organisations do not expect migrants to go to their offices to claim assistance, but rather carry out the distribution of non-food items and medical checks directly in the forests (Reference TyszlerTyszler 2019). In the case of a medical emergency, humanitarians reach migrants in their refuges, conduct a triage, and attempt to treat the patient in place where possible. In the case of deliveries, intractable conditions, or the necessity to see a physician, the social workers would transport migrant people to the hospital and follow up on their admittance and treatment.Footnote 7

In sum, border violence structures the conditions of existence and functioning of humanitarianism. Systematic abuse against migrants triggers the need for emergency relief, while also limiting humanitarian intervention to a form of minimal biopolitics that supports life in the interstices of border violence. The next section will unravel the symbiotic relation that humanitarians entertain with one particular source of border violence: the state.

Encountering the State(s) at the Border

The Moroccan state constitutes a significant actor in the creation of the conditions that lead to the emergence of the humanitarian border. Contrary to what one might expect, humanitarians engage with two different facets of the state at the border: a state that heals, as represented by the healthcare workers who cooperate with humanitarians to heal border violence; and a state that strikes, as portrayed by the police forces that endanger migrant lives and determine the conditions under which humanitarians can operate at the border. These two facets of the state lie on two opposite extremes of the biopolitical spectrum: the state is an entity that exposes migrants to lethal conditions, while at the same time rescuing them from death (Reference JusionyteJusionyte 2017, Reference Jusionyte2018; Reference WilliamsWilliams 2015, Reference Williams2016).

The healthcare system forms part of a state that heals. Indeed, relief workers routinely engage with Moroccan public healthcare structures with which they have a collaborative relationship. Migrants have and still do struggle to access and be admitted to medical facilities without the help of an NGO, especially given the limited freedom of movement that they face in the city. However, hospitals generally accept migrants when they are accompanied by an NGO representative and, as MSF reported in 2013, over the years migrants have become more confident in autonomously seeking medical help (MSF 2013c). “This is because civil society has worked a lot there in the past decade” one NGO officer explained to me. “Now the medical staff is used to staying with the migrants.”Footnote 8

Humanitarians, aid workers and state physicians have all placed the protection of life at the heart of their mandate (Reference RoborghRoborgh 2018). The treatment of foreign patients suffering from injuries caused by border control is therefore jointly conducted by humanitarians and local physicians. Humanitarians initiated and continue this collaboration for both strategic and practical purposes. According to MSF, supporting a parallel healthcare system would undermine the sustainability of medical assistance to migrants. It would also risk discriminating between foreign and Moroccan patients – as vulnerable foreigners would have more chances to access free medical assistance than poor Moroccans (MSF 2013c). Indeed, enhancing the capacity of public medical facilities was chosen and perpetuated after the end of the MSF mission as a more durable solution to tackle migrant vulnerability in the borderlands. Furthermore, directly providing medical treatment to migrants requires financial resources, logistical and medical skills that not all humanitarian organisations have.Footnote 9

Moroccan medical facilities have not only been contributing to humanitarian work by showing an accommodating stance towards the work of humanitarians. At times, medics have openly challenged the repressive attitude of the state towards the presence of migrants in order to allow patients to access treatment. As a former humanitarian worker recalled:

One day I received a call from a Ghanaian guy who needed medical assistance. The guy had a broken leg and I told him that he needed to be transported to the hospital. The patient firmly refused. He feared that if he had gone to the hospital, the police would have arrested him and deported him at the border with Algeria. I went to the hospital of Nador and discussed the question with the medical staff. One of the physicians formulated an abstract hypothesis. “Well, the guy can come here, and we can get him in a cast. Then, if after we have done it, he goes out of the hospital without us realising it and by chance you pass with your car in front of the hospital in that very moment ….”Footnote 10

Beside encountering a state that heals, humanitarians at the border also have to navigate a complex coexistence with a state that strikes, to borrow the words of Michel Agier (Reference AgierAgier 2003). Humanitarians and Moroccan police forces have very different stakes vis-à-vis migrant presence in the borderlands – the former providing emergency protection and the latter containing it through endangerment. The relations between these two actors, however, is more distinctively characterised by the sovereign capacity of the state to decide whether humanitarians can stay in the field and access their patients. In most liminal settings, humanitarians do not have the capacity to freely operate in the field. Their capacity to stay and access their beneficiaries is directly dependent on the tolerance of the various sovereign bodies regulating the area, entities that humanitarians often do not have many means to oppose (Reference Magone, Neuman and WeissmanMagone et al. 2012). The Moroccan borderlands are no exception to this rule. As in many other humanitarian sites, the presence of humanitarians in a space so violently regulated by Moroccan police forces builds on a fragile equilibrium composed of explicit and implicit rules, margins of permissibility, and boundaries to be respected. This zone of indistinctiveness obliges humanitarians to resort to tactics which ensure their discretion. A former humanitarian officer recalled that his team had to enter the forest surrounding Nador around 7.30 a.m. and leave around 10 a.m. to conduct distributions of non-food items and medical visits. Arriving early was essential to avoid the Moroccan police, which would station in front of the entrance to the forest every morning from 8.30 until the evening. “Nobody told us we could visit migrants in the forest, but they saw us going out [of the forest] every day and didn’t say anything” my respondent argued. “They tolerated our work. There was a sort of non-aggression pact.”Footnote 11

Despite the policy of institutionalised harassment against migrants, the authorities appear to tolerate the assistance provided by humanitarians to vulnerable foreigners. State authorities do not, however, necessarily provide a formal acknowledgement of humanitarians’ right to work in the borderlands. In 2011, local authorities suddenly prevented MSF from working in Nador (MSF 2013b). For an entire year, the organisation engaged in negotiations with local authorities to be allowed to resume their activities. After a year of constant negotiations, MSF acknowledged the uselessness of this approach. As a former officer of MSF Morocco said, at some point the team “realised that nobody would ever take the responsibility to sign a document saying that we were allowed to go into the forests. So, we just decided to inform the authorities by letter and go, without waiting for their permission”.Footnote 12 The absence of written permission becomes a tool through which humanitarian activities are kept in a space of uncertainty – not authorised, not prevented, but always preventable. As aforementioned Padre Esteban declared in an interview to the Servicio Jesuita a Migrantes before being banned from Morocco:

The second thing that I would ask for is a written authorisation for the work that we conduct. There are verbal permissions that constitute a legal limbo, especially when the policeman on duty asks for a paper that we do not have, no? Sometimes, for effectiveness, it is better to keep on being in this limbo that does not imply the clash of two opposite opinions. I do not know, but the best thing would be to have written permission for work that has nothing to hide.

In the case of IOs, the state more directly monitors their operations by limiting their capacity to open offices in the borderlandsFootnote 13 (see Reference CollyerCollyer 2012). The UNHCR, for example, has never been able to have a formal presence in the borderlands due to its legal mandate of international protection. So far, the agency has only managed to establish a partnership and referral mechanism with the Moroccan Organisation for Human Rights in Oujda. The latter was chosen as an operational partner for its historical proximity to the government as an attempt to reduce tensions with Moroccan authorities.Footnote 14 At the time of my fieldwork, the IOM focal point in Oujda represented the only formal presence of IOs in the area. However, this form of institutional presence is very low-key: as Richard, the IOM officer I mentioned in previous chapters, stressed during an interview, “this is not an office, it is a focal point.”Footnote 15

Moroccan authorities control humanitarian activities not only by denying written permissions, but also by surveilling organisations operating at the border (IRIDIA et al. 2017). During an interview, a former officer of MSF Morocco told me that during their mobile medical clinics in the woods of Nador in 2011/2012, they could see and hear Moroccan military helicopters flying over the forests to watch over their work. A 2017 report by Iridia, Novact,Footnote 16 and Fotomovimiento on the Southern European border dedicates a section to the “Repression of the defence of human rights” on the Moroccan side of the fence. The authors of the report stress that many of their interviewees had asked for their identity to be kept anonymous “for fear of retaliation” (IRIDIA et al. 2017, 66, translation by author). As one of the respondents interviewed in the report put it:

In Morocco there is constantly a lot of police and a lot of people watching you: the gorilla,Footnote 17 the one living opposite you, the one at the bar, the one that is drinking a coffee. Everything is very ambiguous, nobody tells you what you can or what you can’t do. You get signs or warnings, and you must learn to interpret them if you want to keep on working. Otherwise, you leave. And if you stay, you shut up.

These tactics of surveillance do not only target foreign-funded organisations, but also local organisations funded by Moroccan authorities. In the winter of 2017, the Moroccan NGO Manos Solidarias organised a medical caravan in the forest of Bel Younech, close to the Spanish enclave of Ceuta. Funded by the MDMCMREAM, the caravan was the third event of this kind organised by the NGO and aimed to provide humanitarian assistance to migrant people living in precarious conditions in the forests in Northern Morocco. Once the distribution was underway in Bel Younech, however, Moroccan police forces showed up and barred the NGO from continuing to provide assistance to migrants. This was particularly bizarre: the NGO officers, in fact, had submitted authorisation requests for the medical caravan to the local authorities of the nearby cities of Tétouan and Fnideq. Both requests, however, had gone incommunicado (Reference BentalebBentaleb 2017). What happened to Manos Solidarias, it must be said, contains a paradox: contrary to most humanitarian activities conducted in the borderlands, the medical caravan barred by Moroccan police forces had been funded by the Moroccan Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The state that was preventing humanitarians from helping migrants was the same state that had funded that same assistance activity.

Placed at the two ends of a biopolitical spectrum, the security and the medical branches of the state apparatus have very different relationships with humanitarians. State healthcare structures and humanitarians combine their efforts to form a broader left hand of the border. State security, conversely, not only creates the conditions requiring the intervention of humanitarians, it also polices the very presence of emergency workers in the borderlands, putting migrants’ life at risk not only through direct violence, but also through the obstruction of emergency rescue.

Never-Ending Crisis and Humanitarian Purpose

Minimal biopolitics is a system of power built on an extremely fragile balance of forces and circumstances. Humanitarianism is punctuated by potential fracture points which constantly challenge the meaning, appropriateness, and duration of emergency action. ‘Crisis’ is one such potential point of fracture. Humanitarianism, in fact, has a deep and challenging relationship with the ‘exceptional’. Although suffering can be found in multiple and variegated sites (Reference FassinFassin 2011a; Reference TicktinTicktin 2006, Reference Ticktin2011) the life upon which most humanitarian organisations focus “is not an ordinary one, in the sense of being burdened by everyday complaints”, but is “the life located in an exceptional state of risk” (Reference RedfieldRedfield 2013, 33). However, in contexts characterised by severe conditions of precariousness, inequality, and injustice, the boundary between ‘crisis’ and ‘normalcy’ becomes blurred. The violence and precariousness produced by the border generate a critical albeit local need for emergency relief, which would be otherwise unthinkable (Reference Pallister-Wilkins, Günay and WitjesPallister-Wilkins 2016).

The relation between border humanitarianism and the exception is particularly evident in Morocco, which is an unusual setting for humanitarians. The Kingdom does not present any of the characteristics that normally justify the deployment of humanitarian relief (war, natural disaster, etc.). And yet, there are humanitarians. While recalling the beginning of IOM’s work in the borderlands in 2012, a former employee of the IOM Morocco said: “Morocco is not really the country where you can do humanitarian work. However, the cases of victims of border violence that we were receiving [for Voluntary Return] were too alarming, and we decided to dig into it.”Footnote 18 The exceptional character of border violence transforms the borderlands into the only areas where humanitarian projects assisting migrants in Morocco are to be found. Trying to implement such a programme away from the border deprives humanitarians of the circumstances justifying their intervention: crisis. In 2007, MSF tried to replicate the humanitarian project implemented at the border in Rabat and Casablanca (MSF España 2007). Shortly after its inception, NGO staff realised that their emergency project was unnecessary in urban settings. Migrants in Rabat and Casablanca were not exposed to such high levels of violence and precariousness as in Oujda or Nador, which made a humanitarian approach useless and discriminatory towards the Moroccan population. Confronted with the redundancy of humanitarianism, MSF decided to shift the project to a development-like initiative aimed at ensuring migrants’ access to healthcare by strengthening the capacity of Moroccan public authorities.Footnote 19

And yet, the existence of a border is not sufficient to justify humanitarian intervention. Borders need to be characterised by an acute state of tension. As I mentioned earlier, in 2003 MSF set up a project in Tangier to assist the substantial migrant population living in precarious conditions in the historical centre and in the outskirts of the city. At that time, the city constituted one of the main points of departure of migrant boats heading to Spain. In the following years, the reinforcement of migration control in the Strait of Gibraltar reoriented migration routes towards the Canary Islands (Reference VivesVives 2017a, Reference Vives2017b). This determined a decrease in the number of attempts at crossing (Migreurop 2006) and of the precarious migrant population living in Tangier. Within this framework, MSF estimated that its work was no longer needed and decided to end the project in 2006. The reduction of border pressure had made humanitarian efforts redundant.Footnote 20

The ordinary violence that characterises certain sections of the border generates a never-ending need for humanitarian relief. Prolonged emergencies, however, also challenge the very meaning of humanitarian operations (Reference Barnett and WeissBarnett and Weiss 2008; Reference FeldmanFeldman 2015; Reference RedfieldRedfield 2013). Over the past fifteen years, humanitarians based in Moroccan borderlands have had to question more than once the meaning and validity of their interventions as the causes of suffering lay beyond their response capacity. The last report published by MSF poignantly exposed the difficulty for the organisation to operate transformative change in the field:

Although the medical and psychological needs of victims of human trafficking networks are extremely acute, the absence of other organisations providing assistance and, crucially, protection services, limits the impact of MSF’s assistance.

“It’s extremely frustrating, we provide medical and psychological assistance to victims of trafficking, but we know that as soon as they leave the consultation room they face the same, horrific levels of violence and abuse that brought them to us in the first place”. MSF Medical Coordinator

The report issued by MSF conveys a certain humanitarian fatigue for minimal biopolitics. The medical coordinator interviewed as part of the report expressed frustration at recognising that the emergency intervention was only keeping abuse at bay. Frustration with minimal biopolitics can lead humanitarians to leave. After much discussion, in 2012 the perceived absence of purpose pushed MSF to announce the withdrawal of the Moroccan mission. In an interview with Jeune Afrique, the then head of the MSF mission in Morocco stated that the NGO had recognised that its engagement was “unsuitable for the situation in the field”:

[The fact that we are closing the mission in Morocco] can seem contradictory. But we remarked that the work that is needed here is not the one of a medical NGO. We are not an organisation for the defence of human rights, even if we can denounce violations.

The protracted temporality of border emergency does not only produce ethical challenges for NGOs but is also incompatible with donor funding policies. In 2015, the AECID rejected a proposal for an eighteen-month project on “Improved healthcare attention to the sub-Saharan population in Nador” presented by a Spanish faith-based organisation. According to the AECID evaluation form, the main official reason for the rejection appeared to be the lack of sustainability of the project. The evaluation committee questioned the fact that the project would substitute the action of the state. The proponent organisation, the report continued, had not clearly indicated how activities would be handed over to the Moroccan authorities after the end of the funding, nor how the provision of healthcare to migrants would be maintained afterwards (Cooperación Española 2015). A similar reason motivated a change in funding policy pursued by Swiss Development Cooperation in 2017. In September of that year, the donor announced its decision to stop funding humanitarian projects in Morocco.Footnote 21 As an officer of the Swiss Development Cooperation told me in an interview, until then Switzerland had funded projects in migration and protection in Morocco through the humanitarian aid line. However, the geographical priorities in the distribution of Swiss humanitarian aid had changed. As Morocco had adopted a new migration policy centred on migrant integration, Switzerland felt that it was no longer appropriate to work on migration issues with a humanitarian approach. “Morocco now has a migration policy, and the state considers itself responsible of its resources” my respondent told me. “By continuing to work in the same way we are feeding a system which supports a logic of substitution.”Footnote 22 Whereas MSF voiced its frustration with minimal biopolitics in a more political way, donors tend to distance themselves from it through bureaucratic vocabulary, highlighting the “inappropriateness” and “incompatibility” of emergency action with the broader policies carried out in the country.

Frustration with minimal biopolitics is not a feeling shared by all actors operating in the borderlands. The ordinary character of a border crisis certainly pushes certain humanitarian actors out of the field. However, it also creates opportunities for groups of new, heterogeneous actors willing to engage in relief assistance. In 2010, MSF supported a Moroccan NGO funded by the Swiss Development Cooperation to set up a shelter for migrant women and their children in Oujda.Footnote 23 Between 2011 and 2012, when police violence in the borderlands escalated following the outbreak of the Libyan war, the IOM and the UNHCR sought the support of MSF to visit the borderlands and assess the needs and the possibility of establishing a stronger institutional presence in the area.Footnote 24 In 2012, after deciding to close the mission in the country, MSF started preparing the handover of its activities: it actively looked for other organisations that could continue delivering emergency assistance to migrants stranded in the area, and connected them to potential donors.Footnote 25 Although chronic crisis had pushed MSF to withdraw from the mission, the reality on the ground pushed staff to find a solution to ensure continuity so as not to leave migrants without assistance (Reference TyszlerTyszler 2019). As I mentioned earlier in the chapter, by the time MSF left, the project had been taken over by an IOM-led initiative funded by the Swiss Development Cooperation. Many of the staff previously employed by MSF continued on the new project, including the person who then became the IOM focal point in Oujda in 2014. Donors thus stepped in at the moment when MSF was leaving. In this way, aid allowed for the continuation of humanitarian activities in a context where a radical organisation did not feel like its functional symbiosis with border violence made sense anymore.

Crisis challenges the purpose of border humanitarianism. The exception activates and localises the need for humanitarian action. The prolonged extent of the crisis, however, makes humanitarian efforts redundant for those actors that do not recognise themselves in a minimal biopolitical mandate. In Morocco, the prolonged extent of the crisis marks a fracture between those actors that leave and those that decide to stay. Crisis thus transforms the border environment. The departure of MSF and the infiltration of aid in the borderlands marked the beginning of a process of depoliticisation of humanitarianism. This became particularly apparent in the evolution of a key humanitarian activity: testimony.

Unspeakable Violence and Humanitarian Testimony

Like crisis, testimony also pushes humanitarians’ minimal biopolitics to the edge of fracture. Testimony is central to humanitarian practice (Reference FassinFassin 2008). Bearing witness, however, has a particularly complex relationship with maintaining access to the field (Reference TerryTerry 2000), which makes it one of the most divisive topics among and within humanitarian organisations.Footnote 26 Humanitarians see what the Moroccan state – and, in more indirect ways, European authorities – do to migrants at the border.Footnote 27 An aid worker operating in Nador recalled:

There has been the case of another 14-year-old kid, he stayed seven days in a coma, he arrived to Melilla and then he was sent back by the Spanish police … either he banged his head and then the Spanish police sent him back while he was unconscious, or it was the Spanish police or the fence, which is the same because they are devices paid for by the EU and it kills people. The Moroccan police beat this 14-year-old kid that was in a coma […] … but these are cases that happen every day, it is systematic violence.Footnote 28

The story of Padre Esteban that I started this chapter with is emblematic of the inconvenient position that humanitarians inhabit at the border. Esteban and his humanitarian team, in fact, “had seen everything” on migrants’ bodies, including the most lethal expressions of border violence (Público 2016).

The presence of external actors in the borderlands is particularly problematic for Moroccan authorities. Border violence, in fact, contrasts with the way Morocco wants to present itself to the international community – as a modern, moderate country, respectful of human rights and engaged in the process of democratic transition. Since the early 1990s and more decidedly after 1999, Morocco has undertaken a reformist pattern, aiming to distance itself from the authoritarian imprint that had marked the reign of King Hassan II (Reference BonoBono 2008). This process was sanctioned by the approval of two constitutional reforms in 1992 and 1996, the promotion of a regime of “alternation” in 1998 led by the by Socialist Union of Popular Forces’ Abderrahman Youssoufi, and by the ratification of a number of human right treaties (Reference Jiménez Álvarez, Espiñeira and GazzottiJiménez Álvarez et al. 2020). The political openings characterising the transition included the recognition of human rights abuses perpetrated by the regime in the previous decades (Reference Catusse and VairelCatusse and Vairel 2003; Reference VairelVairel 2004), a phase which is now publicly portrayed as over (Reference Bono, Mouna, Therrien and BouasriaBono 2017). Since its launch, the new migration policy itself has been inscribed into this transitional path, as a demonstration of the commitment of Morocco to maintain its international engagement on the respect of human rights (see Reference NatterNatter 2018). The formal alignment of Morocco to the international human rights regime, however, did not correspond to a disappearance of authoritarian techniques of ruling – like the suppression of dissident voices, the persistence of legislations constraining civil liberties, and the deployment of violence against marginalised groups (Amnesty International 2017; Human Rights Watch 2017a, 2017b; Telquel 2017). To borrow Can’s reflections on Turkey, coercive and violent mechanisms of state power have not disappeared, but they “have become less sustainable for the image of the state at the national and international levels” (Reference CanCan 2016, 352).

The announcement of the new migration policy and the establishment of a political climate more respectful of migrant rights has gone hand in hand with the denial of border violence. On 10 September 2013, King Mohammed VI gave his High Royal Orientations for the formulation of the new migration policy. The communiqué of the Moroccan Royal Cabinet, however, denied the existence of routinised violence against migrants in the country and specified that:

If the operational management of irregular immigration results sometimes in certain excesses, which remain isolated, there is no systematic use of violence by police forces and even less of persecution. Morocco therefore categorically refuses all fallacious allegations that try to harm its reputation.

Testimony has a disruptive potential. By exposing the crude reality of violence against marginalised populations, testimony can challenge the status quo. In March 2013, MSF published the report “Violences, Vulnérabilité et Migration: Bloqués aux Portes de l’Europe” (Violence, Vulnerability and Migration: Blocked at Europe’s Doors). In the document, MSF held Moroccan and Spanish authorities directly responsible for migrants’ precarious healthcare conditions. MSF accused them not only of perpetrating violence against migrants, but also of fostering a climate of fear and terror which prevented migrants from seeking medical care (MSF 2013c). The report received a significant amount of media attention. It thus contributed to the construction of a climate of international shaming that drove Morocco to reform its migration policy (Reference Jiménez Álvarez, Espiñeira and GazzottiJiménez Álvarez et al. 2020).

Speaking out, however, can hamper the relations between humanitarians and sovereign authorities. The state can punish organisations that trespass the boundaries of permissibility by forbidding them from accessing the field. The disruptive nature of testimony thus marks the boundaries of minimal biopolitics: the potential to operate transformative action entails the risk of losing the possibility to operate at all. Morocco’s decision to ban Padre Esteban from returning to Nador seems to be intimately linked to the will of the authorities to keep critical voices away from the borderlands. As two NGO officers put it in an interview:

Lorena: Why was he [Padre Esteban] banned from entry again? Is it because he was speaking out [about border violence]?

Interviewee 1: I think it was for his relationship with the media, it was really …

Interviewee 2: Well, he talked a lot [to journalists] but according to me it was necessary to talk … it is true that he was very abrupt, very direct, so at a certain moment they [the Moroccan authorities] must have said “We are fed up with it”. Maybe it [speaking out] could have been done differently, but it is not that it should have been avoided, everything that he said was well said, maybe the form was not ideal for Morocco ….Footnote 29

Each humanitarian organisation therefore has to balance access to the field and advocacy. The outcome varies depending on the nature of the organisation and its commitment to testimony. Speaking up or staying silent, in fact, are not foregone conclusions, but compromise solutions that organisations have to partake in. Here lies the main difference between the operations of MSF, the actions of Padre Esteban, and the workings of other aid-funded organisations that continued the work of MSF. Despite primarily adhering to a mandate of protecting life, MSF also has a strong duty to bear witness to the violence experienced by its beneficiaries (Reference RedfieldRedfield 2006, Reference Redfield, Bornstein and Redfield2010, Reference Redfield2013). Over the years MSF had to elaborate a calculated advocacy strategy alternating “visibility” and “invisibility” in order to maintain access to the field. From 2003 to 2010, the organisation maintained a very low profile for its operations. As Moroccan authorities treated migration strictly as a security issue, MSF “had to be as invisible as the migrants were”, as a member of the organisation recalled during an interview.Footnote 30 During this period of discretion, MSF staff directly witnessed some of the darkest pages of the history of migration control in the country.Footnote 31 Despite its strategy of “invisibility”, the organisation still issued three critical reports – in 2005, 2008,Footnote 32 and 2010 respectively – denouncing the inhumane treatment of migrants at the border. In 2011, the organisation decided to abandon this approach, and to shift to full visibility.Footnote 33 This change occurred, unsurprisingly, around the same time as the decision to close the mission. Although MSF’s decision decidedly played a role in communicating the ongoing abuses against migrants to the international community, the report was not unanimously welcomed by civil society organisations operating in Morocco (Reference TyszlerTyszler 2019). Some of my respondents suggested that the ongoing strict surveillance of organisations working in the borderlands is linked to the fear that humanitarians and human rights organisations might expose Morocco again to international shaming.Footnote 34

The replacement of MSF with other NGOs and IOs has produced a shift in the way humanitarian work is performed at the Spanish–Moroccan frontier. Whereas MSF had a clear duty to testify against human rights abuses, the actors who replaced the organisation occupy a very different position. The IOM, in particular, follows an openly acknowledged principle to avoid criticising state authorities in public (Reference Olin, Floring and BengtssonOlin et al. 2008, 22). The pamphlets and leaflets published by the Moroccan mission of the IOM never mention police violence against migrants. The publicly available material only mentions that migrants encounter “difficult life conditions” in Morocco (OIM 2017, 9, translation by author). It also specifies that “the passage [to Spain] is far from easy given the securitarian devices in place. In the hopes of reaching Spanish shores, migrants accumulate a certain number of vulnerabilities, which reinforce their precarity” (OIM 2016, 7, translation by author). The causes underlying the production of migrants’ “vulnerabilities” at the border are, however, never discussed.

Donor-funded humanitarian organisations now mainly engage with healing the bodily dimension of border violence, with very little to no space left for the engagement in advocacy activities. Especially since Padre Esteban has been barred from re-entering Morocco, humanitarian NGOs operating at the border only issue communications related to violence against migrants through collective and cautious publications that have a limited outreach.Footnote 35 The only organisation operating at the border that regularly diffuses pictures and communiqués on violence against migrants in the area is the Nador branch of the Moroccan Association of Human Rights (AMDH, in the French acronym). AMDH Nador, however, has a much more limited outreach than INGOs or IOs. The organisation and its members are also more vulnerable to the actions of the Moroccan state than international actors (see Frontline Defenders 2020).

The weakening of critical humanitarian voices feeds a broader choir of international institutions celebrating Morocco’s engagement in migration governance. As I mentioned in the introduction already, this celebratory discourse also elicits criticism about state-perpetrated abuses against migrants at the border. A report published by GIZ in 2016 is very symptomatic of such a trend. In 2016, the GIZ published a report called “A Tale of Three Cities”, comparing migrant integration in Tangier, Istanbul, and Offenbach. The document identified the weakness of local institutions and xenophobic attitudes expressed by the local population as the main challenges to migration governance and integration in Tangier (Integration Strategy Group 2016). Shortly after the report was publicly released, the Moroccan NGO Al-Khaima circulated on social media a letter addressed to the GIZ and criticising the report. The letter stated that:

After having read your document, we understand that it is not appropriate to take the city of Tangier as an example concerning integration in the Mediterranean area. Tangier is a border city and because of that the city records a lot of human rights violations and violence against migrants.

A human rights activist that I interviewed in Tangier defined this sort of discourse as a “pact of silence”. As they poignantly put it during our conversation:

[…] there is a pacte du silence [a pact of silence]. Morocco with this new migration policy has accepted to be the guardian of European borders … and donors try to correct here all the mistakes that they have done on integration in Europe. And Morocco wants to show everyone that they are a bastion in the respect of human rights in the region and that everything goes well, because this gives them more power in Africa …. Et ça arrange tout le monde [and this suits everyone].Footnote 36

The departure of radical actors and the infiltration of aid has marked a depoliticisation of humanitarian border work. The forced departure of figures juggling advocacy and access to the field (like Padre Esteban), the establishment of organisations not prioritising testimony (like the IOM), and the influence of donors avoiding public controversy with Moroccan authorities (like Switzerland) meant that humanitarianism lost its subversive character. Within an aid environment supporting a sanitised portrayal of Morocco as a country of integration, humanitarianism contained itself to the role of provision of a minimal biopolitics – healing migrants’ bodily injuries, keeping death at bay, but not attempting to structurally reverse the causes of border suffering.

Conclusion

Since the mid-2000s, humanitarian organisations have become a steady presence in the governance of Moroccan borderlands. Humanitarian projects develop in the interstices of border violence. They treat the direct and indirect victims of the border. They adapt their working patterns to the rhythm of the violent intrusion of the state in migrant existence. Within this symbiosis, humanitarians establish a double relation with the state: a conflictual relation with security forces which attempt to control and contain emergency outreach; and a collaborative interaction with state healthcare structures, which share the humanitarian mandate to protect life. By providing a form of minimal biopolitics, humanitarian care has become instrumental to the reproduction of a border regime that structurally marginalises migrants’ lives. In the borderlands, migrants are strictly confined to the margins, and humanitarian action can take care of these expendable lives just as long as relief is provided within the margins. Humanitarian care therefore does not work to reverse the conditions that have triggered the need for relief in the first place. It mainly operates to make this process of marginalisation less deadly.

The state of never-ending crisis unfolding at the border challenges the mandate of humanitarian organisations. Confronted with their incapacity to operate transformative action, activist organisations like MSF can decide to leave the field. However, the perpetual border crisis creates niches of opportunity for new organisations to assist migrants in distress. The presence of European donors is instrumental to the reproduction of the humanitarian border. It allows organisations like the IOM to expand their presence in the field when other, more activist actors decide that they have to leave. The arrival of donor-funded organisations, less prone to risk losing access to the field in favour of speaking out, has however led to a fundamental depoliticisation of humanitarianism. As more radical humanitarian formations have been substituted by actors with a weaker mandate to testimony, the border has become more and more silent. Aid thus sustains a threatened and silent apparatus of emergency relief, which maintains migrants’ lives in the margins, without disrupting the conditions which enables life degradation in the first place.