It’s a story of a king who is building a palace, a huge extensive edifice, and he subsequently realizes that he can’t complete it within his lifetime and he is distraught. He instructs his carpenters to imprint on every stone and beam, “After me cometh a builder; tell him, I too, am known.”

With the failure of the bombing pause, McNamara’s influence on Vietnam decision-making decreased. He remained Secretary of Defense until February 1968 but spent much of the intervening period drifting further apart from President Johnson, who began to overrule him. After a fresh round of personnel changes, including McGeorge Bundy’s departure to take the job McNamara had wanted as president of the Ford Foundation, McNamara became isolated in an administration that continued to favor “hard” options on Vietnam despite questionable results. As it did, McNamara’s achievements at the Defense Department began to unravel.

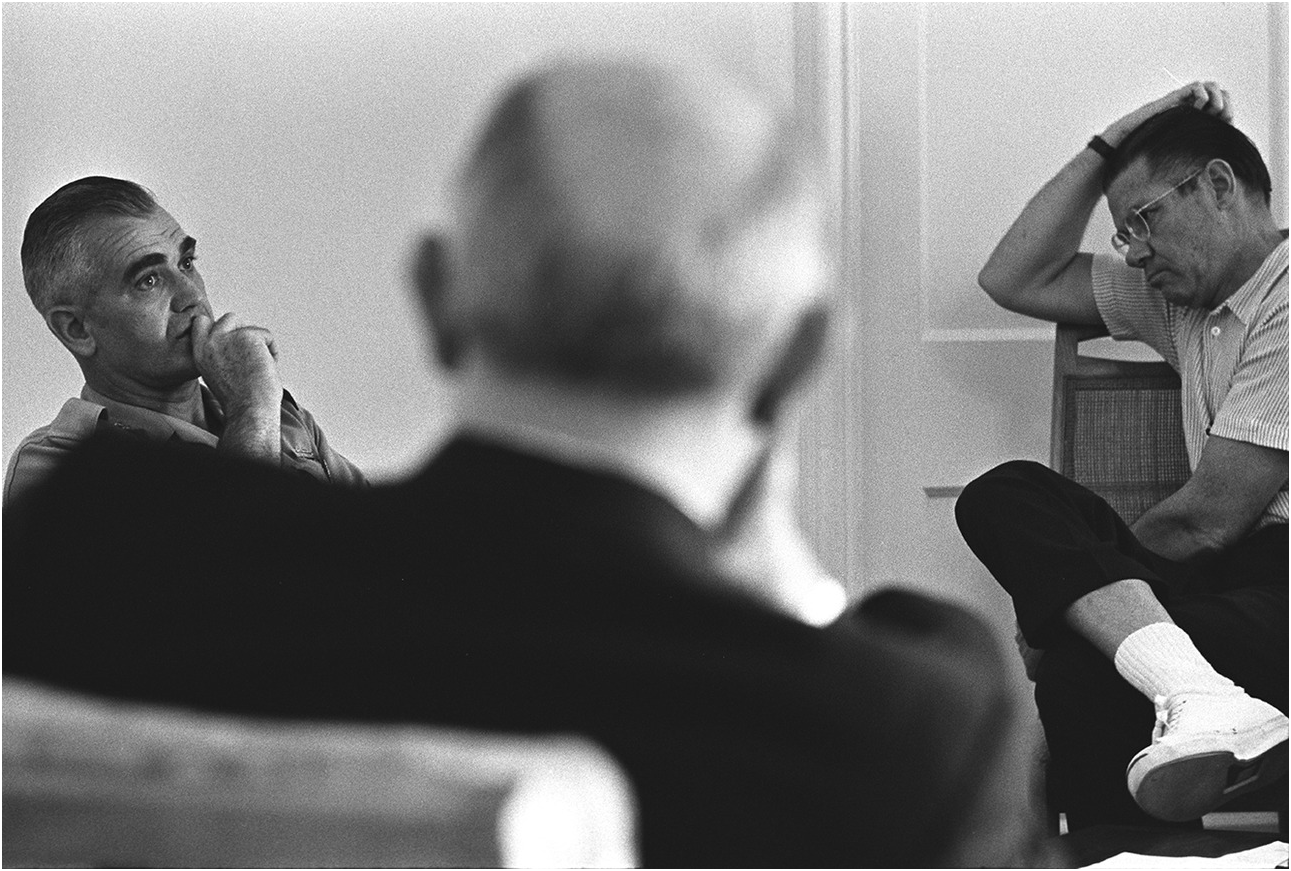

The year 1966 was one of interlocking personal, economic, military and political crises (see Figure 9.1). The consequences of escalation in Vietnam ricocheted onto the domestic and global economy. In March, funding for Vietnam was removed entirely from MAP channels and came under the SASC. The SFRC and SASC both attacked the Secretary for his lack of candor and for the consequences of the administration’s political and economic obfuscations. Stung by congressional criticism and the label of “McNamara’s war,” he informed the Democratic backlash to the President through Robert Kennedy and set out to restore his reputation and protect his legacy at the Defense Department. His friendship with Robert Kennedy exacerbated his disenchantment with the war and strained his loyalty to Johnson to the breaking point. Like many Kennedy holdovers, he drew explicit and unfavorable comparisons between the two Presidents that he had served.

Figure 9.1 From left to right, General Westmoreland, Secretary of State Rusk and Secretary of Defense McNamara attend Honolulu Conference on the Vietnam War, February 2, 1966.

In Vietnam, despite a burst of diplomatic activity in the spring of 1966, the prospect of a negotiated settlement in Vietnam all but ended. Instead, escalation continued with no clear objective in sight. With nothing left to lose, McNamara belatedly stepped out of his self-imposed restrictions and began to question the administration’s strategy openly. He returned to the ideas that he had defended in the Kennedy administration and, in 1967, bypassed the State Department and effectively stepped in to run a peace overture himself.

The end of the bombing pause coincided with developments that set the tone for the rest of the year. Within the administration, McNamara and other “Kennedy men” became increasingly critical of civilian leaders in the White House and State Department. Many, including Cyrus Vance, McGeorge Bundy and George Ball, left. McGeorge Bundy’s departure was a “tragedy” for McNaughton and McNamara, who “didn’t see how things could work at all well” when Rostow replaced Bundy in a downgraded National Security Advisor role.2 McNamara’s private conversations with McNaughton about Rostow’s promotion were unflattering to the President and to his new advisor. About Johnson, he remarked that “he wants a paper shuffler. He says he has enough trouble arriving at decisions when he gets advice from two people; three people is too many.” About Rostow, he observed that he “is full of ideas; the trouble is – so many of them are wrong.”3 Harriman was even harsher and described Rostow as “a menace because of his bent toward escalation.”4 Harriman also criticized William Bundy, whom he said was “just not up to the job,” adding, “State is terribly weak at the top,”5 an assessment that he shared with Michael Forrestal, who felt “all the [State] bureaus have fallen into the hands of people without imagination,” and that “Bill Bundy was the worst of them all.”6

Like many holdovers from the Kennedy administration, McNamara began to draw direct parallels with John F. Kennedy’s policies for Vietnam in a way that challenged Johnson’s contention that he had merely carried through commitments that he had inherited from his predecessor. This was potentially politically explosive for Johnson, who once recounted that “the thing I feared from the first day of my presidency” was that Robert Kennedy would “reclaim the throne in memory of his brother.”7

In February 1966, McNamara reflected on “the Kennedy policy” for Vietnam and how it differed from Johnson’s. McNaughton’s diary reads, “McNamara this morning, while talking with Cy[rus Vance] and me, said that ‘there is not a piece of paper – no record – showing when we changed from an advisory effort to a combat role in Vietnam. I am prepared to say that the United States should not, in the case of covert insurgencies, do more than provide advice and material help to a country. That we should either go to the source of the trouble, like bombing North Vietnam or take it to an international tribunal. He said that that was the Kennedy policy’” (emphasis in original).8 McNamara considered the Johnson administration’s inability to produce a strategy that relied on the purposeful application of military force or alternatives to military force, and maintained that “What we need is a theory that will limit our role”; that bombing had relied on a gamble that “we could pull it off” rather than a strategy per se.9

A “theory” to limit the US role in Vietnam gained urgency as congressional anger about the war mounted. The SFRC spearheaded the Democratic backlash against the Vietnam War when in February, Senator Fulbright launched televised hearings that condemned the administration and McNamara’s conduct of the war specifically. At the same time, however, it continued to weaken the MAP program, which might have supported alternatives to traditional military tools. By March 1966, to bring the MAP under the $1 billion mark as he had promised to do in 1963, and with Fulbright’s support, McNamara formally transferred Vietnam costs into the DOD budget, leaving only minor internal security programs in the USAID budget. McNamara criticized the Fulbright committee for gutting the MAP while the defense budget received funds the administration did not request nor need and explained that the military budget “makes no sense without military assistance.”10

On February 19, in reaction to Rusk’s testimony in front of the Fulbright hearings, Robert Kennedy issued a statement where he questioned the direction of Vietnam policy and suggested a coalition government in the South. Kennedy’s comments in February 1966 had a direct connection to McNamara’s growing frustrations. To the press, McNamara rather implausibly said, “I talked to Bobby Kennedy briefly on another matter Friday afternoon, and he indicated that he was going to make a statement, but we didn’t go into the detail of it.”11 On the contrary, the sheer volume of meetings they shared in 1965, which accelerated in the spring of 1966, suggests otherwise. McNamara spoke to Kennedy at least five times in the days before his statement and again two days later.12 Moreover, in an oral history interview, Senator Edward “Ted” Kennedy remembered how his brother and McNamara’s meetings “were never really reported,” that McNamara would “always go over [to Hickory Hill] for a couple of hours” and that “McNamara was beginning to have very serious second thoughts, but was unwilling or unable – or both – to be able to change it. I think talking to McNamara deepened Bobby’s concern.”13 By February, McNamara, who was unable or unwilling to change the course of the war from inside the administration, contributed to shifting the debate outside the administration.

Johnson criticized “Fulbright, Bobby Kennedy, Teddy Kennedy, Morse” and reminded McNamara that their failure to “cohese” had meant that they “didn’t get anything through in the 1961–64 period.”14 Johnson questioned Fulbright’s motives and cruelly attacked the senator as menopausal and “off his rocker.”15 He questioned the patriotism of SFRC critics instead of engaging with the content of their disagreements.16 By contrast, McNamara and his colleagues at ISA were sympathetic to Fulbright’s criticism even if they blamed him for having inadvertently created budgetary pressures toward militarization. After one particularly heated exchange, McNaughton noted in his diary: “My guilty feeling went with our pretention that the answers are simple – as if Fulbright had nothing to his arguments. It’s the difference between the pose of a leader and the ruminations of an intellectual.”17

For its part, the SASC condemned McNamara for short-changing service needs for operations in Vietnam. He dismissed their accusations as “ridiculous” and quoted his field commanders’ satisfaction with the support they were receiving. He proudly explained that the Vietnam buildup had occurred without the type of domestic upheaval that the Korean War had caused and added that “we seem to take a masochistic pleasure in flailing ourselves with imaginary weakness.”18

Congressional anger also grew over McNamara’s failure to disclose the true costs of escalation in 1965. On Johnson’s request and against his better judgment, McNamara had delayed asking for the full costs of the 1965 escalation until he presented his budget statement in January and submitted a supplemental budget request for Vietnam. Despite claims that the United States could afford both guns and butter without inflationary pressures, the cost of the Vietnam War had doubled from earlier projections and set off inflation. McNamara had favored a graduated bombing program, in part, because it appeared to be the most economical option. The truth was that the cost of operations had become “unbelievably expensive” especially as airplane losses went up. In April alone, forty-four airplanes were lost over Vietnam. McNamara therefore concluded that the numbers predicted for the FY67 were also significantly undervalued and that he would need an additional $14 billion above his budget request if the buildup continued at its present rate and if the war did not end by June, as his budget had assumed.19

Chairman of the Federal Reserve Martin had increased interest rates in December over inflationary fears when he understood the true extent of McNamara’s manipulations. As they became clearer to others, fears mounted and the stock market plunged. Johnson’s more liberal advisors, including the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers Gardner Ackley and Bureau of Budget Director Charles Schulze, now joined Martin and urged the President to pass a tax increase. A temporary excise tax was enacted in March.20

However, in a midterm election year, Johnson wanted to avoid both a debate about the budget and a broader tax increase. He preferred to focus on more favorable economic indicators, including low unemployment and GDP growth. These were more favorable to a Democratic administration that had pushed through a tax break promising that it would jump-start the economy. He criticized liberals as “not prudent folk” and reacted angrily to Ackley and Martin’s “talk” during an election year, saying they “must not admit it, not even feel it in [their] own minds,” hoping that “if I could keep [the budget] low, I could get my Great Society authorized.” McNamara agreed to delay a tax increase if the situation became “clearer” in the second half of the year but warned that the OSD should nevertheless be more transparent with Johnson’s economic advisors so they could provide the President with well-informed advice.21

By April, as the budgetary numbers exploded with no end in sight and with domestic pressure building, McNamara became desperate. In private, “in an unguarded moment” he told McNaughton, “I want to give the order to our troops to get out of there so bad that I can hardly stand it.”22 With a new Buddhist crisis in South Vietnam in the spring of 1966, the country descended into “semi-anarchy,” leading many advisors to conclude that “the Vietnamese whose total incapacity to behave themselves should amount to at least a minimum justification for our dumping them.”23 When US forces were caught in the crossfires of South Vietnamese violence, Galbraith, Harriman and Kaysen each proposed a version of McNaughton’s suggestion to McNamara that “all-out internecine strike in VN would provide us as good an excuse as we could find to disengage.”24 “The problem, of course,” as McNaughton wrote in his diary, was “how.”

When the South Vietnamese government promised elections within five months as a way of resolving the crisis, McNamara sensed an opportunity. As Robert Kennedy had done in his February statement, he recommended that the South Vietnamese try for a coalition government with the Viet Cong.25 To the SFRC, he laid the political groundwork for the gambit and explained, “It is our goal to allow those people to choose the form of political institutions under which they prefer to live. I suppose you could conceive of them choosing some form other than a democratic form. If they did, we would adhere to that choice.”26 Crucially, he understood that the Viet Cong “might or might not take over”; the implication, as McNaughton observed, “is that we’ll then let South Vietnam’s chips falls where they may.”27

The underlying issue, however, was that the administration had no shared understanding of what US objectives in Vietnam were. By the spring of 1966, McNamara was less concerned about the international consequences of Vietnam and had effectively concluded that the United States was “on a losing wicket in Vietnam.”28 His objective, therefore, joined McNaughton’s of withdrawing while minimizing the international and domestic fallout. A coalition government and a negotiated settlement by the end of the year met his objectives and could be financed without additional budgetary upheaval. However, both he and McNaughton observed that “Rusk kept the US eye on the VC total capitulation!”29 They concluded that the administration “must crack through the obstacles to re-examining our objectives (which Bob said neither Rusk nor the President is ready for). Otherwise, none of the sensible actions get taken.”30 Strategy and the meaningful application of military force was impossible without clearer and agreed-on objectives.

Against this backdrop, Ball and McNaughton prepared a report suggesting a fresh set of options for the United States’ efforts in Vietnam. These options included: more of the same, pushing the South Vietnamese toward a settlement or “grab (or create) an excuse to exit.” McNaughton annotated the implied objectives for McNamara. For example, next to a sharp escalation or the present program, he wrote “victory?”; next to freezing the program, he wrote “compromise?”; and next to his favored policy of disengagement, he wrote “loss-minimization.”31

As McNamara’s appraisal of what might constitute realistic objectives in Vietnam shifted, so too did the urgency to adjust military tools accordingly. He described bombing as a “side show of minor military importance,” whose only value was in encouraging a settlement and whose outcome was unlikely to “cause North Vietnam to fold.”32 His view that the bombing program was largely unsuccessful was confirmed in a series of reports in March and April. McNamara had commissioned an independent study of the air war. It agreed with the CIA that bombing had not appreciably affected the North’s ability to fight the war in the South nor had it attained any of its other, ancillary objectives.33 Unlike McNamara, however, the JCS, with a strong advocate in Rostow, encouraged Johnson to move forward on striking industrial targets in the Hanoi–Haiphong area, including bombing POL storage areas and mining Haiphong harbor.34

In response, the OSD resuscitated an old idea about building a barrier aimed at curtailing infiltration into South Vietnam. McNamara and his colleagues were of two minds on the project. On the one hand, it appealed to McNamara’s interest in projects that relied on “imaginative use of technology,” which might obviate the need for further bombing and thus reduce casualties.35 McNaughton described one especially lively discussion on the subject where “Before long [McNamara] was bouncing around the room, looking at maps of [Southeast Asia] and of Europe (to compare the Iron Curtain). He said, ‘Give me $2 billion and I’ll build a barrier no one can get through.’”36 On the other hand, JCS and OSD experts largely rejected the barrier as both impracticable and cost-prohibitive. McNamara and his colleagues at the OSD welcomed the program in the spring of 1966 “because the military reject it with enthusiasm and because it would introduce another variable (presumably debate-provoking).”37 In other words, in bringing up the barrier again, McNamara hoped to force a discussion about the efficacy of bombing in light of its now obvious economic and human costs.

While McNamara’s friends recognized that he did not “urge his private views on the President with the force that he does with his old friends of the Kennedy years,”38 he nevertheless came out much more forcefully than he had hitherto dared in support of negotiations and against the bombing program. This was a significant break for a Secretary of Defense who had scrupulously resisted interfering in what he saw as the State Department’s domain. From January to June, several “promising”39 peace overtures emerged, including a mission led by Chester Ronning, a retired Canadian diplomat, that coincided with the debates over bombing POL targets. Rusk dismissed Ronning’s mission: “quite frankly,” he told the Embassy in South Vietnam, “I attach no importance to this trip and expect nothing of it.”40 By contrast, McNamara urged to the President to hold off on military moves and wait.41

Ultimately, the diplomatic avenues came to naught and, with them, so too did McNamara’s attempts to prevent further expansion of the bombing program. By June, he fell in line, and in what McNaughton described as a “staged NSC meeting” where the “President obviously had arrived at his decision earlier,”42 he acquiesced to bombing the POL targets and blandly observed that “no senior military leader recommends anything other than proceeding with this program.”43 In a private conversation with Johnson, however, he reiterated his reservations: “it just scares me to see what we’re doing there … going after a bunch of half-starved beggars … the great dangers and it’s not a certainty, but it’s a danger we need to look at is that they can keep that up almost indefinitely.”44

Despite his unsuccessful attempts at holding the line in the spring of 1966, McNamara and his colleagues drew lessons from their failures that would inform the future course of diplomacy in Vietnam. First, for them, the lack of coordination between political and military moves had scuttled even modest openings. Although McNamara micro-managed the selection of bombing targets, commanders in the field often determined the timing of the raids, which had on occasion coincided with diplomatic moves.45 Hanoi overestimated the United States government’s ability to coordinate its military and political tracks and therefore saw the attacks as gestures of bad faith. Second, intransigence on both sides was a problem.46 McNaughton observed that “it could be that adversaries might miss opportunities to settle because they insist on moving their settlement terms up and down as the tides of conflict flow better or worse.”47

While McNamara could do little about North Vietnamese inflexibility, his colleagues urged him to push through on the US side. Johnson’s presumptive “ambassador for peace”48 Harriman encouraged McNamara to get “involved in the political aspects of Vietnam” and argued that this would not pervert his conception of State and Defense roles since “military action was in part political.”49 Harriman was even more candid with McNaughton, whom he had mentored when they had worked together on the Marshall Plan. In July, just as a new Italian-Polish led effort code-named “Marigold” was gathering steam, Harriman pulled McNaughton aside and told him, “If you and Bob don’t do it, it won’t be done … State is making no initiatives on the diplomatic side.”50 By September, Harriman was “exercised about our apparent inability to get negotiations started” and described Rusk as “a cork in the bottle.”51 The view that Rusk was unwilling to compromise enough for a political settlement and instead viewed the problems in Vietnam “in highly moralistic terms” was widely shared among skeptical advisors.52

As McNamara became embattled and isolated both within the administration and outside, he sensed his days at the Pentagon were numbered. He therefore moved to restore his public image and protect his legacy at the Defense Department. Since the fall of 1965, McNamara had had regular meetings with the journalist Stewart Alsop in view of producing a profile of the Secretary. The article was finally published in May 1966 and read like an obituary. “McNamara seems likely to go down in history as one of the very greatest public servants this country has produced,” Alsop wrote. The article began with what McNamara later concluded was his greatest achievement, namely his role in changing the US nuclear posture to reflect that it was “impossible to win an all-out nuclear exchange.” Alsop implied that McNamara had wanted to leave for some time and felt that five years, in other words, January 1966, was the “outside limit a Secretary of Defense could usefully serve.” McNamara confessed that “I’ve failed” on Vietnam but defended the value of civilian control and his focus on “rationality” despite the fact that “war is an emotional and irrational affair.” To Alsop, he explained that “reason” had “shield[ed] him from the terrible pressures to which a Secretary of Defense is subjected – the pressures which killed James Forrestal.”

Alsop tried to humanize McNamara and wrote of his different “sides”: he “sound[ed] like a sort of mechanical oracle” and talked of emotion “as on old-fashioned preacher might talk about sin, as the source of all errors,” but “beneath the coolly assured surface” was a “McNamara who shows himself very rarely – an emotional McNamara.” Behind the descriptions about the “gay and charming guest, who has been known to dance a mean Frug” resided the main point of the article, which was to convey that the personal attacks that impugned his character had affected McNamara. It described that he teared up when he felt his honesty was questioned. The article accepted, as McNamara did, that the concentration of power and discipline he had enforced at the OSD may have grated others but explained that it took “simple courage” to make these decisions in the first place.

Alsop and others acted as mouthpieces for McNamara’s attempts at rehabilitation. To his credit, Johnson also countered Fulbright’s caricatured image of McNamara as a number-crunching, unfeeling architect of the war. He recounted a conversation with Fulbright to McNamara explaining that if he had any reservations, “they were because you were not combatative enough, that you had too much of the professor approach, were too much like him – both of you these goddamn crazy scholars, going around here with a pencil in your ear and want to try to dream out something when you sometimes have to stand up … Your friend Rusk is more of a militarist than McNamara. He just couldn’t conceive of it.”53 To others, Johnson similarly said, “They had pictured McNamara as being a big, fat President of Ford. And he’s not.”54 McNamara’s notes from his MAP hearings took a similarly defensive line; he scribbled: “I majored in Philosophy not Statistics or Military Science.”55

McNamara continued this public relations offensive in a series of speeches that coincided with Alsop’s article, first at his daughter’s commencement ceremony at Chatham College and then before the American Society of News Editors in Montreal. In the latter, he built on his notes from the SFRC hearings and attacked the “tendency to think of our security problem as being exclusively a military problem – and to think of the military problem as being exclusively a weapons-system or hardware problem.” He directly challenged the premise for US involvement in Vietnam, suggesting that communism was not a monolithic threat on the world stage and often merely appended itself to conflicts that were rooted in poverty. He added his own view on what the United States should have done in Vietnam, without saying so directly: “Experience confirms what human nature suggests: that in most instances of internal violence the local people themselves are best able to deal directly with the situation within the framework of their own traditions.”56

He ended the speech on a measured note; the man who had been the spokesperson for “rationality” in government policy now reflected on “Man.” He asked, “Is he a rational animal?” Answering his own question, McNamara concluded, “All the evidence of history suggests that Man is indeed a rational animal but with a near infinite capacity for folly. His history seems largely a halting, but persistent, effort to raise his reason above his animality. He draws blueprints for utopia. But never quite gets it built. In the end he plugs away obstinately with the only building material really ever at hand: his own part-comic, part-tragic, part-cussed, but part-glorious nature.”57 After more than five years “plugging away” in office, McNamara may have been reflecting on his failed “blueprints.”

A measure of just how far apart McNamara’s and Johnson’s views on Vietnam had become was illustrated just the day before McNamara made his speech in Montreal. Johnson delivered a speech in Chicago in sharp contrast to McNamara. He noted the lessons from World War II were that “the road to peace is not the road of concession and retreat,” that in Vietnam as elsewhere, “The failure to meet aggression means war, not peace.” He complained about “Nervous Nellies” who could become “frustrated and bothered and break ranks under the strain, and some will turn on their leaders, and on their country, and our own fighting men.” He ended with a line that could not have differed more from McNamara’s view: “The men who fight for us out there tonight in Vietnam – they are trying to find a way to peace. But they know – and I don’t understand why we don’t all recognize that we can’t get peace just for wishing for it. We must get on with the job until these men come marching home.”58

A few months later, in a closed meeting with faculty members at Harvard University, McNamara explained the rationale behind his Montreal speech: “I got so goddam frustrated that I had to have some release … Montreal was an immature act. My responsibility is not to build my image but to manage a department. In those terms, Montreal was a luxury. You don’t inspire men to obey commands by casting doubt on a central doctrine of their reason for being; that is, that security equals military power.” When he was asked about the role the speech may have had in changing the terms of the debate on Vietnam within the administration, McNamara made a telling remark: “That’s not really my problem. What I have to worry about is keeping the lid on Vietnam and in that battle, Montreal cost me plenty. I’m not sorry that I made it.”59

The Montreal speech fueled Johnson’s suspicions that Robert Kennedy was behind his Secretary’s newfound softness (see Figure 9.2). In particular, McNamara had suggested a universal service program in the United States as a way of renewing a sense of national purpose and addressing the unequal burdens of the draft. This was a quintessentially “Kennedy” idea; Robert Kennedy had considered a domestic peace corps program during his brother’s administration. In the months before McNamara’s speech, the issue of reforming the draft had gained a prominent advocate in Senator Edward Kennedy as it had become clear that poorer African Americans were disproportionately dying in Vietnam.60 Edward Kennedy later confirmed that his brother Robert had spurred his interest: “I remember walking into Bobby’s house, probably ’65, ’66, and he mentioned the draft and who was fighting the war,” he remembered. “It was all the poor and the blacks … He said, I can’t take that on. I had an interest in that, so I started offering these amendments.”61

Figure 9.2 New York Senator Robert F. Kennedy (left) and Secretary of Defense McNamara (right), November 5, 1964. Their friendship would create tensions between McNamara and President Johnson.

While many observers celebrated the “real McNamara”62 for standing up in Montreal, his political counterparts were more circumspect. British Ambassador to Washington Sir Patrick Dean reported back to London that “there is also probably some intention on McNamara’s part to improve his personal image … by refuting the idea that he is a militarist by temperament,” adding that “he is known to be sensitive to the popular description of the Vietnamese operation as ‘McNamara’s War.’”63 Closer to home, Townsend Hoopes, who would soon replace McNaughton at ISA, applauded the “agile, almost discrete declaration of independence from the rigidity and growing irrationality of official policy on fundamental issues.”64 Hoopes and the British Embassy assessed that the speeches also represented a revealing break for McNamara, where he stepped away from technical speeches on defense issues to question existing policies for Vietnam and the Cold War. Ambassador Dean observed that it was the “first time so far as I know that the Secretary of Defense has made a major public statement of this sort directed more to a review of foreign policy than to strategy or military questions proper.”65

As the year progressed, McNamara turned away from “military questions proper” and became involved in the diplomatic and political aspects of the war, as Harriman and others had suggested he should. As the midterm elections neared, congressional criticism from the SFRC quieted and Johnson tried to dampen remaining criticisms from the military and from those who argued that the administration did not have a credible negotiating position. McNamara was instrumental in each of these efforts, although he privately felt “the President should change both his Secretaries of State and Defense” after the election.66

In October, he was sent back to Vietnam for the first time in more than a year to nominally consider a fresh request for more troops. Admiral Sharp had requested a troop increase to 570,000 by the end of 1967, a higher number than McNamara had projected in 1965. A month before midterm elections, Johnson wanted McNamara to silence military advisors who increasingly criticized civilians for their timidity and parsimony. Republicans, including Richard Nixon, began to use these views in their political campaigning. In Vietnam, Westmoreland reassured McNamara that “not a single operation” was hampered “in any way by logistical problems,” and the “only service” where he saw problems was the Air Force, which expressed “frustrations over ‘restrictions’ and failure to accomplish what they thought they could.”67

On his return, McNamara spoke glowingly of operations in Vietnam. Behind the scenes, however, he and McNaughton prepared a scathing report for the President and claimed that there had been no progress since 1961. The pacification programs that McNamara had encouraged had, if anything, “gone backward” and the stalemate that he had found in the fall of 1965 was still there but “at a much higher level of conflict.” The bombing program was no more successful. He concluded that the administration should therefore stabilize military operations and redouble its efforts on pacification, focus on clear and hold strategies and, crucially, build up the South Vietnamese capabilities to wage the war themselves while pressuring them into negotiations, however unpromising those negotiations may be.68 The United States needed a way out of Vietnam. McNamara thus began a slow arc back to his objectives and policies of 1963.

Also in October, Johnson convened a meeting in Manila with allies fighting in South Vietnam to assess the situation there and provide a public plan for peace. Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko had suggested that the United States provide a firmer timetable for its promise that it would withdraw troops as and when North Vietnam did.69 With this in mind, Johnson dictated much of what would become the “Manila communiqué.” The “most interesting place,” McNaughton observed, was the fifth clause, which stated: “The people of South Vietnam will ask their allies to remove their forces and evacuate their installations as the military and subversive forces of North Vietnam are withdrawn, infiltration ceases, and the level of violence thus subsides.”70 McNaughton resisted the final clause, which initially read “and the level of violence subsides,” because he and others did not want to “commit the United States to settling internal South Vietnamese squabbles” (emphasis in original). To assuage OSD concerns, the word “thus” was introduced.71 The official position, therefore, became that South Vietnam’s internal problems would be theirs alone and that the United States would disengage if North Vietnam promised to do the same.

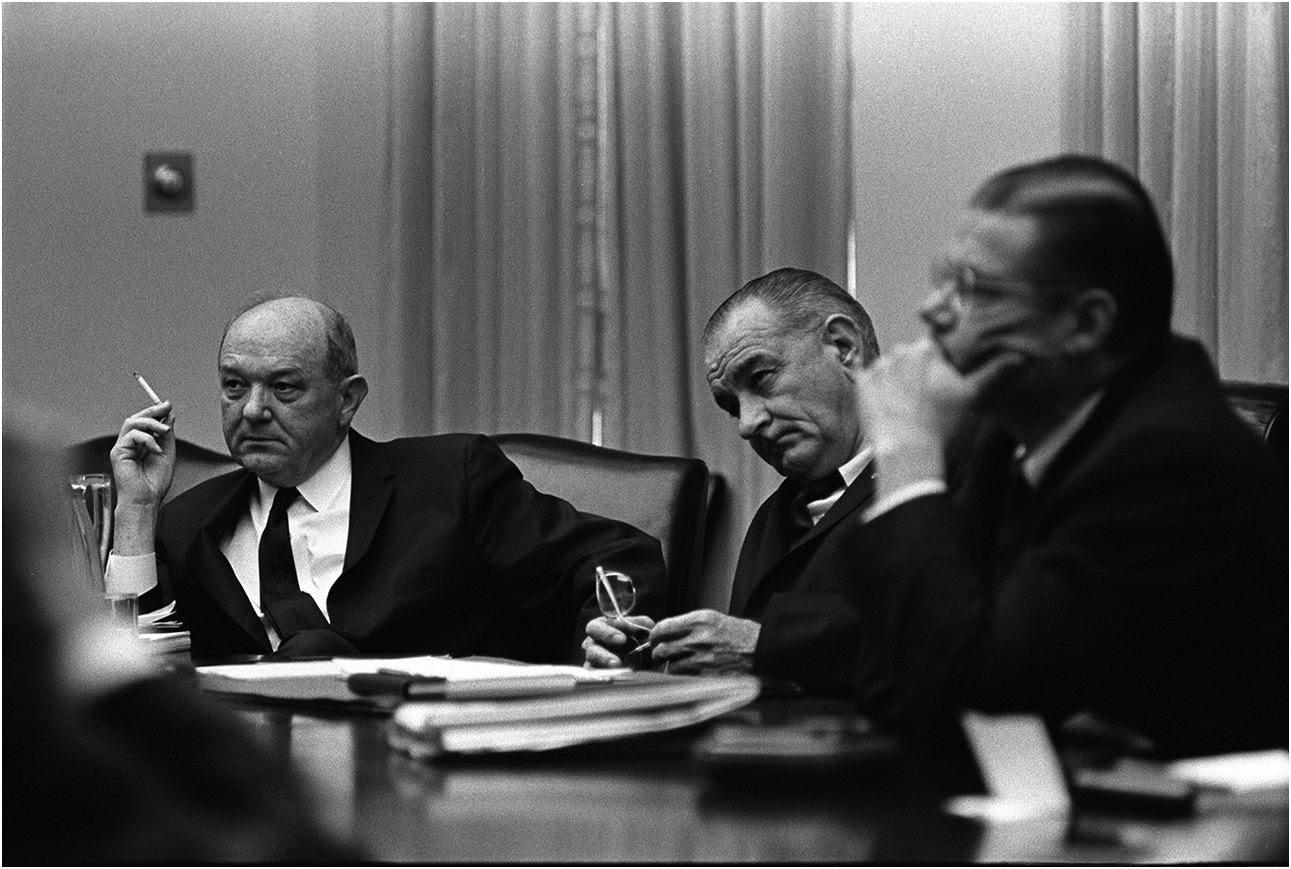

By 1967, McNamara expressed “surprise that he is still Sec Def” (see Figure 9.3).72 Although he continued to consider job offers, he felt an obligation to stay as long as the war went on and as long as he continued to believe that he could hold back more dramatic military choices. Johnson hoped to keep him on until the 1968 election but began to “express doubts … about his loyalty and stability.”73 Above all, he grew increasingly suspicious of McNamara’s friendship with “Bobby,” which suggests that he kept him within the administration because he was too much of a political liability outside it. McNaughton concluded that his boss was a lame duck, that he had suffered a “diminution of power, of influence,” and that “under Kennedy and in the early Johnson days, I sensed a semi-conspiratorial relationship with McNamara – in which things were accomplished despite bureaucratic hurdles … Now I sense that the President is on the ‘hard’ side of Bob – e.g., on Vietnam, in Europe, regarding Anti-Ballistic missiles, etc.”74

Figure 9.3 Secretary of State Rusk (left), President Johnson (middle) and Secretary of Defense McNamara (right) attend a meeting on Vietnam, January 20, 1967. By 1967, McNamara expressed surprise that he was still at the Pentagon and was frustrated by the State Department and White House’s inflexibility on the subject of negotiations.

Throughout 1966 and increasingly throughout 1967, Johnson began to overrule McNamara’s judgement. In Vietnam, on several occasions, he reinstated air targets that the JCS had recommended but which McNamara had rejected.75 In August, the semblance of civil-military harmony gave way to bitter exchanges when Senator Stennis convened hearings that were officially meant to assess the conduct of the air war over Vietnam but unofficially to “get McNamara.”76 The Secretary scoffed at the Chiefs and, somewhat ironically given his positions in the past, told Stennis that the United States could not “win the war on the cheap by bombing.”77

As McNamara’s relationship with the Chiefs deteriorated, Johnson tried to improve civil-military relations. He included Wheeler in his Tuesday lunches and encouraged the Chiefs to report directly to him.78 Similarly, McNamara had resisted an ABM program and ran a personal channel with the Soviet embassy to that end.79 He had told McNaughton that “there are few things that I fight hard with the President, but this will be one of them.”80 In September 1967, Johnson countermanded him and approved a “light” version of the ABM. Johnson’s overtures to the Chiefs undermined one of McNamara’s most important achievements at the OSD, that is, that the direct reporting lines that had existed between the President and the Chiefs had been broken and that civilians at the OSD had been given a mediating role.

Johnson also stymied McNamara’s long-standing efforts at redeploying troops in Europe and Asia. These had gone ahead on a small scale, if surreptitiously, as troops and equipment were redeployed to Vietnam and not returned.81 However, in 1966, McNamara had resumed more robust planning for troop reductions for balance of payments reasons. With France’s withdrawal from NATO’s integrated military command, Germany also began backing away from its offset agreements and Britain cut its conventional forces in the face of its own economic problems. At home, Senator Mansfield pushed for a reduction in US forces in Europe. ISA wholeheartedly supported Mansfield’s efforts, if not publicly, as a way of pushing through its plans to “dual-base” forces, namely repatriating forces to the United States and using investments in mobility to redeploy those forces as needed. In response, European Allies in NATO finally accepted a defense posture based on flexible response but only then “to lock [US] conventional forces in Europe.”82 John McCloy was appointed as the administration’s envoy to Europe to deal with the thorny issue of troop realignments. With Johnson’s support, he joined State and the JCS in resisting the OSD’s efforts.

As his professional achievements fell apart, so too did McNamara himself. By 1967, he was a broken man. He commissioned a study, which became known as the Pentagon Papers, with the express aim of identifying the mistakes that had led to the Vietnam War and to prevent a similar catastrophe from occurring again. In relatively quick succession, he lost his three of his closest advisors, the few he could count on as confidants: Yarmolinsky, whose relationship to Johnson had soured, left, as did Vance. In July, McNaughton was killed in an airplane accident. Closer to home, his relationship with his son broke down over the war and his beloved wife Margaret developed ulcers, which her friends referred to as “Bob’s ulcer.”83 The “emotional McNamara” described in Alsop’s article became more and more visible. Despite his attempts at public redemption, McNamara was attacked wherever he went. Angry students encircled him at Harvard University, which dampened his hopes of returning there.84 In March 1967, he was attacked on the ski slopes of Zermatt in Switzerland, and in September, for the second time, an anti-war protestor tried to set his home in Aspen on fire.85

McNamara experienced a moral crisis over Vietnam decisions. Whereas in Montreal and elsewhere in 1966, he had merely intimated his discomfort about them, in 1967, they exploded into the open. In February, he condemned the bombing program in a meeting where his colleagues described a “distraught and tense McNamara, eyes tearing and voice faltering.”86 In August, during one of Johnson’s Tuesday lunches, McNamara denounced the JCS’s recommendation to bomb densely populated areas around Hanoi and said “he was not worried about the heat [he would get from Congress over bombing limitations] as long as he knew what we were doing is right.”87 Although in the early years of the Vietnam commitment, McNamara had extended tours of duty as a resource allocation measure, without considering the human impact on the men he was deploying, and had recommended a sustained bombing campaign with minimal concern for the resulting casualties, this all began to change. To make the human costs of decisions explicit to others, he asked the JCS to provide estimates of civilian and US forces casualty figures with their recommendations.

One of McNamara’s favorite poems was T. S. Elliot’s “Four Quartets,” and he quoted one passage regularly, including during an appearance on Meet the Press in February 1968, on the day he left the Pentagon, in the preface of his memoirs and at the end of the documentary The Fog of War. It reads, “We shall not cease from exploration / And the end of all our exploring / Will be to arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.” In his last months at the Pentagon, the policies he suggested for Vietnam did just that: at the end of his “exploring,” he returned to where he had started and presented very similar policies to the ones he had in 1963.

In May, McNamara and McNaughton put pen to paper and in a DPM argued that the war was unwinnable and was “acquiring a momentum of its own that must be stopped.”88 The immediate impetus for McNamara’s DPM was Westmoreland’s latest request for an additional 200,000 troops and “an extension of the war into the VC/NVA sanctuaries (Laos, Cambodia, and possibly North Vietnam), mining of North Vietnamese ports and a solid commitment in manpower and resources to a military victory.”89 It coincided with a separate JCS posture statement, which indicated that drawdowns in forces abroad to meet Vietnam requirements had resulted in their inability to effectively meet contingencies that might arise elsewhere in the world.90

McNamara described the ensuing debate as a “’65 type watershed”:91 Westmoreland’s request necessarily required a reserve call-up and “would not win the Vietnam War, but only submerge it in a larger one.”92 Going against Rostow’s and the Chiefs’ resistance, McNamara suggested that the United States reassess its objectives in South Vietnam. He presented the same arguments that McNaughton had made since 1965 and wrote that the administration should begin to reduce the importance of South Vietnam in its public pronouncements and accept a role for the Viet Cong in the South. While the debate in Washington raged, McNamara helped to establish the Civil Operations and Rural Development Support (CORDS) program, the first fully integrated pacification program under Westmoreland’s command. As he had in 1963, he understood that other agencies were less capable of coordinating complex and expensive operations. McNamara’s implied objective in May 1967 was therefore to plan for withdrawal and refocus efforts back to the village level in South Vietnam and away from the “big war” of attrition.

Officially, McNamara went back and forth on bombing throughout this debate. In reality, he informed Robert Kennedy’s statement on March 2, the first since February 1966, which called for a unilateral bombing halt and an offer to begin negotiations “within a week.”93 A month earlier, McNaughton had observed that McNamara “would have been willing to do so” as well.94 In public, for a time, the Secretary of Defense supported Johnson’s decision to expand the targets under Operation Rolling Thunder. By May, though, he called for restrictions on bombing of areas south of the 20th parallel and, in September, joined Kennedy’s position and encouraged Johnson to unilaterally and indefinitely stop the bombing program.95 In a gesture of good will and with an eye to Robert Kennedy, Johnson suggested that he would call off bombing and meet “tomorrow” if “productive discussions” were possible and if North Vietnam “would not take advantage of the bombing cessation or limitation.”96 McNamara called for a cessation without conditions.

His position shifted because of enduring doubts about bombing but also because he had taken a lead role in the so-called Pennsylvania Initiative. Although Rusk and Johnson had never had great confidence in this latest effort at a political settlement, McNamara described it as the “most interesting” negotiation “we have ever had” and, as Harriman had suggested to him, stepped into a role that should have been the State Department’s.97 The mission was run through Harvard Professor Henry Kissinger and two French emissaries, Herbert Marcovitch and Raymond Aubrac, an old friend of Ho Chi Minh’s.98 In September, however, Kissinger had conveyed Marcovitch’s anger that “every time I brought a message we bombed the center of a North Vietnamese city. If this happened one more time, he was no longer prepared to serve as channel.”99 Marcovitch’s complaint represented exactly the type of misalignment of political and military tools that had bothered OSD officials the year before. McNamara was therefore eager to learn from past mistakes and thought a bombing cessation would put the ball firmly in North Vietnam’s court.

When the Pennsylvania Initiative collapsed in mid-October, McNamara “precipitated the last act” of his tenure as Secretary of Defense.100 In his March statement, Kennedy had reiterated his support for a coalition government in the South and suggested the progressive withdrawal of US forces from there under international auspices. During a Tuesday lunch on October 31 and the next day in writing, McNamara made the same suggestion and in great detail. He spelled out the human costs of likely escalations over the next fifteen months: some “10,900 to 15,000 dead,” 30,000 to 45,000 “requiring hospitalization” and further destruction in the South. He questioned whether pacification could “accelerate considerably” but noted with annoyance that none of the JCS’s recommendations focused on the South. In lieu of the policies currently under consideration, he recommended a program that would stabilize US forces and progressively hand over the fighting to the Vietnamese. It bore a striking resemblance to the same policies that he had advocated for in October 1963 only “at a much higher level of conflict.”

Still, McNamara’s reflexive tendency to self-censor out of loyalty to the President endured (see Figure 9.4). He placed a cover note on the memo in which he told the President, “Because these may be incompatible with your own [views], I have not shown the paper to Dean Rusk, Walt Rostow or Bus Wheeler.”101 On the very same day, Johnson asked McNamara to brief the “Wise Men” about the bombing program without disclosing his own views or the memo he had just submitted. In contrast to McNamara, they concluded that bombing continued to be a useful negotiating chip.102 About the meeting, McNamara later noted that “no President should bring into important discussions of events outsiders who really have no full understanding” of the problems.103

Figure 9.4 President Johnson (left) and Secretary McNamara (right) in a Cabinet meeting on the Vietnam War, February 7, 1968. McNamara was days away from leaving the Pentagon to become president of the World Bank.

In later years, McNamara recalled that he “never heard” from Johnson about his November 1 memo. Instead, on November 29, Johnson released a statement announcing McNamara’s departure from the Pentagon to become the new president of the World Bank. He explained that the Secretary had agreed to stay at the Pentagon “so long as the President considered it necessary” and that it was now time for a “fresh person,” that he “could not justify asking Secretary McNamara indefinitely to continue the enormous burdens of his position.” He pointedly added, “the course of our participation to the war in Vietnam is firmly set.”104 In his own statement and meetings with the press, McNamara alluded to the fact that he had considered leaving “in the past two years” and that he had not planned on staying at the Pentagon as long as he had, but that “I have done so because of my feeling of obligation to the President and the nation.”105

However, much as McNamara later prevaricated on the subject, he was fired. Moreover, the World Bank was not an anodyne choice. As an international civil servant, McNamara was forbidden from taking part in domestic politics. Johnson thus neutralized a possible political threat. What most concerned Johnson was not just that his Secretary was finding it more and more difficult to support administration policies – that was not new – but instead that his collusion with Robert Kennedy was becoming obvious. In the days before the President’s announcement, McNamara had had an unusual amount of contact with both Robert Kennedy and Adam Yarmolinsky, who was now working behind the scenes to promote a Kennedy challenge to Johnson.106

At his departure ceremony, Johnson awarded McNamara the Medal of Freedom and predicted that a revolution would come to the World Bank under McNamara’s guidance, the same revolution that he had effected at the Department of Defense. In comments that harkened back to McNamara’s Montreal speech, he said McNamara’s work would now concern “the most important war of all” as he would “attack the root causes of violence and turmoil – poverty, disease, ignorance and hopelessness.”107 In a room filled with Cabinet members as well as Robert and Edward Kennedy, McNamara choked up, “I became so emotional, I could not respond,” he recalled.108 Coughing nervously and holding back tears, he said, “Mr. President, I cannot find the words to express what lies in my heart today. And I think I better respond on another occasion.”109