When Robert McNamara accepted President Kennedy’s offer to serve as the United States’ eighth Secretary of Defense, the role was still new, a barely decade-old innovation emanating from World War II. As a young agency, the OSD was still defining its place in the national security decision-making landscape and, in so doing, trying to find the appropriate balance of power between civilian and military authorities. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had left the new administration with the Defense Reorganization Act of 1958, a congressionally mandated program for change at the Department of Defense. McNamara recognized its sweeping potential to pave the way for his bureaucratic revolutions as the longest-serving Secretary of Defense.1 The year 1960 was a propitious moment in the office’s history and for a man who by personality as well as professional and intellectual inclination was predisposed to pushing organizational change and centralizing authority around himself.

The history of the OSD and the legacy of McNamara’s predecessors provide a context and a framework in which to consider civil-military relations at the time and, ultimately, to understand McNamara’s policy recommendations for Vietnam. The framework in the pages ahead breaks with existing literature that has tended to consider civilian control in terms of cultural, sociological or organizational relationships with the military. Instead, the history of the OSD’s civilian control until 1960 was essentially the history of two trends: strategic and operational control, on the one hand, and “resource allocation,” on the other.2

First, civilian control of strategy and of operational decisions has been the traditional focus of civil-military relations literature and has concentrated on the changing relationships and power dynamics between the OSD, the President, State Department, the National Security Council (NSC) and military services in the articulation of national strategy. The steady progression of civilian control before McNamara’s arrival at the OSD was coupled with the gradual reduction of military voices in the upper echelons of decision-making, a process that each incumbent Secretary on the whole supported.

The second dimension is the economic one, or what Samuel Huntington called “resource allocation”: civilian control was also about defining the appropriate level of fiscal commitment to military expenditures and balancing defense spending with other domestic or civilian needs. Here, the evolution had been more fitful and controversial. Senator Kennedy had campaigned aggressively for increased defense spending and criticized his opponent’s thriftiness. However, despite his campaign rhetoric, Kennedy’s transition team recruited a Secretary of Defense with the managerial skills to control the ballooning defense establishment and its costs. Although the defense budget expanded during the Kennedy years and McNamara’s tenure, the reforms they engineered were specifically designed to reduce defense expenditures in the long term.3

Each Secretary of Defense from the first incumbent James Forrestal to McNamara confronted an in-built cultural ambivalence in the United States about anything that could be construed as extending the reach of the federal government in general and of military authorities specifically. Americans were uncomfortable with the military establishment that they had inherited from World War II. The Pentagon building itself was erected hastily between 1941 and 1942 to coordinate the war but with a stipulation from Congress that it was a temporary structure and that it would be converted into a veteran’s hospital “after peace is restored and the army no longer needs the room.”4

As Ernest May observed, although the US federal government and its military structures were among the “longer-lasting artifacts of the Cold War,” they were not preordained in a culture that had resisted permanent structures to organize the country’s relations with the world.5 The Defense Department was a product of necessity, born of battlefield imperatives during the war rather than from deliberate design. All previous and subsequent attempts to centralize and organize a standing military force faced deeply rooted resistance as it raised the specter of a Prussian-style General Staff.6

After the attack on Pearl Harbor and the United States’ entry into the war, the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration recognized that existing structures were inadequate for a world war and especially for joint operations with British allies. As a result, in February 1942, “quickly and without great fanfare,” the existing, more loosely organized Joint Boards between the Army and Navy were replaced with what would become known as the Joint Chiefs of Staff.7 The latter mirrored the British armed forces as a way to streamline coordination of the Anglo-American Combined Chiefs of Staff that oversaw Allied operations. To provide a counterpart to the British Royal Air Force (RAF), and in recognition of the growing role of air power in this new conflict, the Army’s Air Force was given equal status with the Army and Navy and eventually became a third, independent service.8

The organizational changes to the services challenged the previous segregation of the Army and Navy which, on the basis of “elemental distinction” between land and sea, had jealously guarded their independence until that point, going as far as to produce separate war plans. Even though the war experience offered a case for the unification of the services, unification did not occur. The Navy, under the stewardship of James Forrestal, attacked the plans. In addition to philosophical fears associated with a centralized, military command, the Navy felt that it had the most to lose with unification: it could lose its air power to the newly created Air Force that seemed destined to play a leading role in the command of atomic weapons, and its Marine Corps could be subordinated to the Army to leave the Navy with a much-reduced role.9

By contrast, the Army and Air Force largely welcomed, and even encouraged, the wholesale merger of the armed services. In addition to promising relatively more budgetary security, for the Army, unification provided “a way to deal with a dangerous, rebellious, cocky child, the semiautonomous Army Air Force.”10 For its part, the Air Force supported unification because it relied on greater capital investments that could be siphoned off from the Navy; it “cockily” assumed that it would get a larger share of a unified budget. Its leaders also concluded that equal independence would ensure Air Force dominance because it had succeeded in capturing the imagination of the US public and its congressional leaders by convincing them that air power would be the key to any future war.11

In addition to debates on the merits of unification, the new national security infrastructure caused a debate about the appropriate balance between respecting and protecting military expertise, on the one hand, and ensuring civilian control, on the other. Reflecting this climate, in 1957, Samuel Huntington produced his groundbreaking work on civil-military relations, The Soldier and the State.12 Huntington later described the book as an “unabashed defense of the professional military ethic and rejection of traditional liberalism [which] was in itself evidence of this intellectual debate.”13

Huntington described how the increased complexity of warfare and technology in the nuclear age and the attendant need for specialized military expertise required “institutional autonomy.” Washington’s civilian leaders should resist the temptation to civilianize the military or interfere with its conduct – what he termed “subjective control” – and instead encourage independent military professionalism, or “objective control.” For Huntington, the “requisite for military security [was] a shift in basic American values from liberalism to conservatism”; that is, military values could enrich society rather than vice-versa. Ultimately, Huntington’s work was a product of and reaction to the debates of the times and was born of a concern, which was also distinctly American, that overbearing control of the military was a distinguishing characteristic of dictatorial regimes.14

Huntington juxtaposed two types of actors – civilian and military – in a neat dichotomy around which the battle lines of civil-military relations would be drawn. Barring emblematic civil-military clashes such as the MacArthur controversy over the Truman administration’s policies in Korea, the situation in practice was more complicated. Also, Huntington assumed that military institutions were or could be apolitical, which ignored the fact that from the 1940s onward, military authorities had become intensely political as they became more savvy at competing for resources and influence in Washington.15

Instead of a battle between two sets of actors, the creation of the national security infrastructure had created tensions across several, interlocking axes, including between services themselves, between coordinating bodies such as the NSC and the State Department, between the legislative and executive branches, and between the JCS and the OSD.16 As the Defense Department’s budget expanded, many were concerned about the growing focus of military power on the projection of US power abroad and the OSD’s growing prominence over the State Department. The relationship between the State and Defense Departments and between the Secretaries in defining national security strategy troubled each incumbent pair; more often than not the issues were resolved through personal rapport rather than any enduring bureaucratic solution.

The JCS/OSD axis was equally salient because it hinged on who should be the leading military advisor to the President, the Commander-in-Chief. For General Taylor, Eisenhower’s Army Chief and later Kennedy’s Chairman of the JCS, the JCS should be a non-political body that could transcend agency needs and provide advice on the best way of fulfilling civilian-set objectives.17 At the same time, he agreed with two of McNamara’s civilian advisors who later suggested that “meaningful professional advice” from the JCS was “difficult” if not impossible because of the individual Chiefs’ “channelized thinking.” As he noted, each Chief was still embedded in his service, and as a result, the JCS’s advice was “largely the product of bargaining” between the services.18

The manner in which each President defined the JCS’s role had a direct bearing on the type of Secretary of Defense he sought, namely in determining if the Secretary’s role should be a policy-making one or a managerial one primarily concerned with organizing the budgetary process.19 During these key decades, the OSD expanded its responsibilities along both lines, often to the detriment of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The first President to grapple with these bureaucratic and intellectual challenges was Harry S. Truman. Thrust into the role of President in the closing years of the war, he oversaw the defining moments of the Cold War. During the closing months of the war, the Truman administration also faced the challenging task of demobilization. However, confronted with new threats and international obligations, not least of which was the occupation of Germany and Japan, the United States retained a force that was four times that which had existed in 1939. This was the first time that the United States had a substantial military force in a time of peace. With it came a five-fold increase in defense allocations from $1.8 billion in 1940 to $10 billion in 1948, representing 14 percent of the US GDP by the end of the Truman administration.20

Events including the Berlin airlift in Europe, McCarthyism at home and, above all, the Korean War dashed Truman’s earlier hopes to reap a “peace dividend,” or a major reduction in this new defense budget. Instead, the rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union emerged as the defining characteristic of international relations. Responding to new international realities and responsibilities, Truman presided over the expansion of the national security state. His four Secretaries of Defense – James Forrestal, Louis Johnson, George Marshall and Robert Lovett – each grappled with the President’s inclination to compromise among stakeholders, to “satisfice” in setting up often flawed national security structures and to give them contradictory objectives. In particular, President Truman urged each of his Secretaries of Defense to keep the military budget down even while he expanded the United States’ worldwide commitments.21

The founding act for the Department of Defense, the “compromise National Security Act of 1947,” as one scholar has called it, created most of the principal structures for national security decision-making without settling underlying issues that plagued inter-service relations and their relations with the civilian authorities.22 As the historian John Lewis Gaddis has critically noted, “preoccupied as they were with maintaining support for containment within the bureaucracy, the Congress, the informed public, and among allies overseas,” the administration chose political expediency over efficiency: the “price of administrative effectiveness can be strategic shortsightedness,” and, in this instance in particular, “process triumphed over policy,” where policies and structures that were feasible were chosen over those that were desirable.23 Moreover, many of the structures and especially the OSD were structurally weak, with a notable gap between their formal authority, which was relatively broad, and their substantive authority.

Principally for economic reasons, Truman was initially favorable to the wholesale merger of the services. However, faced with congressional resistance, he compromised and proposed a program of legislative reform whose “overall purpose was to erect an integrated structure to formulate national security policy at the uppermost level of government.”24 The National Security Act created the NSC, which was designed to advise the President on national security issues and provide strategic direction as the country’s international obligations expanded. The NSC’s Chairman was the President and its members included the Secretary of State as well as representatives of three new agencies: the National Security Resources Board (NSRB), the Secretary of Defense and the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The CIA, the successor agency to another World War II innovation, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), became the NSC’s main source of intelligence, although other intelligence agencies scattered across government, including in the military services, continued to operate in parallel. Crucially, each of the Service Secretaries was on the NSC. As a result, defense representatives held four of the seven seats on the NSC in its founding years.25

In addition, the National Security Act created the OSD to oversee the National Military Establishment (NME), later renamed the Department of Defense. The Secretary of Defense was designated as the President’s principal advisor on military affairs and, as such, provided “general direction” to the Secretaries of the Army, Navy and new Air Force. However, in practice, his supervisory responsibilities were limited and, more often than not, undermined by the President himself. Furthermore, the act created three civilian “special assistants” to support the Secretary. These included a Comptroller, who was responsible for harmonizing the service budgets into one annual military budget.26 In addition, the Secretary oversaw two new boards that concerned all military services: the Munitions Board and the Research & Development (R&D) Board.

Despite these reforms, the Service Secretaries retained most of their power, notably by keeping a direct line of communication to both the President and the Bureau of the Budget. The position of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff was a shallow one even if his announced responsibility was ambitious. Officially, he was charged with providing strategic direction to the military forces, preparing plans, establishing unified commands and reviewing materiel and training requirements. In practice, however, he had no power over the Chiefs and instead acted primarily as a liaison with the White House. General Eisenhower was appointed as the first Chairman on a temporary basis in November 1948, but since he continued in his capacity as President of Columbia University, he spent scarce time on his JCS duties. It was not until August 1950, with the appointment of General Omar Bradley, that the JCS had an official Chairman. Moreover, from the start, the Chairman of the Joints of Chiefs and the individual Chiefs were in an unhappy tension with the Secretary of Defense: although they reported to the Secretary of Defense, they were also rival military advisors to the President, NSC, State Department and Congress.

As a result, In August 1949, the act was amended to clarify the respective roles of the Secretary of Defense and the JCS. The powers of the Comptroller were reinforced with a view to creating a first unified budget in fiscal year (FY) 1950. Although the amendments strengthened the Secretary of Defense’s position on the budget, they weakened him by limiting his role to that of “principal assistant to the President in all matters related to the Department of Defense” rather than to defense policy more generally.27 Similarly, since the Service Secretaries no longer chaired in the NSC, they were forced to consolidate their views through one representative, the Chairman of the JCS. In so doing, the latter’s role was strengthened.

In addition, in a move that would frustrate successive administrations, the amendments allowed members of the JCS who were designated as the “principal military advisors to the President and the Secretary of Defense” to disagree with the administration’s policy and to raise their disagreements in Congress “on [their] own initiative, after first informing the Secretary of Defense.”28 The Chiefs’ independent advisory role to Congress, to the President but also to the NSC and the State Department further politicized them and arguably paved the way for public spats with each administration, most notably over the Truman administration’s strategy in Korea, which culminated in the MacArthur controversy.29

The first Secretary of Defense, in office from September 1947 to March 1949, was former Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal. A central figure in the creation of national security structures during and after the war, Forrestal was also credited with coining the phrase “national security” when, during a congressional hearing, he had explained that “our national security can only be assured on a very broad and comprehensive front. I am using the word ‘security’ here consistently and continuously rather than ‘defense.’”30 At the Navy, Forrestal had also been a leading opponent of President Truman’s plans to support the unification of the services. In his first week on the job, he wrote in his diaries, “My chief misgivings about unification derived from my fear that there would be a tendency toward overconcentration and reliance on one man or one-group direction. In other words, too much central control.”31 As a result of his “misgivings,” Forrestal was more responsible than most for the compromises that had resulted in the OSD’s structural weaknesses. Yet despite a personal relationship that would continue to be ambivalent, Truman chose him as his first Secretary of Defense.

Forrestal was given a near impossible task riddled, as it was, with conflicting goals and stakeholders. Truman extended the United States’ responsibilities but imposed low force and budgetary ceilings on Forrestal, which he then had to communicate to and enforce on the Chiefs. In an effort to assuage inter-service issues, the administration insisted on balanced forces, or an equal distribution of resources across the three services. This was counterproductive and resulted in heated debates about strategy among the services. The perceived unfairness of balanced forces played a part in the bitter battle between the Navy and the Air Force about who should be the custodian of atomic weapons.32

The Secretary’s lack of executive power over the Chiefs was almost immediately apparent: the Chiefs ignored his proposed national strategic concept that was designed to guide their military assessments as well as Truman’s budgetary ceiling.33 Instead, they presented him with separate positions and budgets as the Chairmen of the JCS, Eisenhower and then Bradley sidestepped their official responsibility for coordinating the Chiefs’ views. Truman further undermined Forrestal’s authority by regularly bypassing him and reaching out to the Chiefs and the Service Secretaries directly. Perhaps the only relationship that was comparatively smooth during Forrestal’s tenure was with the State Department where he benefited from his friendships with Secretary of State George Marshall and his Undersecretary, Robert Lovett. Their relationships did much to smooth collaboration between the two departments.

Eventually, the stresses of the office began to take their toll on Forrestal, who was unable to control the NME. Aides observed that “part of his scalp had become irritated from continued scratching” as he began to retreat into a state of increased isolation and paranoia.34 By reaching out to Thomas Dewey, Truman’s opponent in the 1948 election, in a bid to remain in office whoever won, Forrestal effectively ended his career. Within three months of resigning from office and after at least one previous attempt, Forrestal committed suicide, by throwing himself from the window of his hospital room at Bethesda Naval Hospital where he was recovering from “nervous exhaustion” that his doctors and friends traced back to the unification debate and to “excessive work during the war and post-war years.”35 The last person to see him recalled him “copying lines from Sophocles’ chorus about the warrior Ajax, worn by the waste of time.”36

James Forrestal’s experience would cast a long shadow over each of his successors and especially on McNamara’s colleagues in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, many of whom had begun their careers in government under him. For some, the relationship with Forrestal was very personal. Michael Forrestal at the NSC was James Forrestal’s son and was unofficially adopted by one of his father’s closest friends, Averell Harriman at the State Department. Townsend Hoopes, a Forrestal mentee and later McNamara’s Deputy for International Security Affairs, wrote a biography of Forrestal in which he described the latter’s death as “towering loss” and a “profound personal tragedy.”37 Secretary of the Treasury C. Douglas Dillon’s father had chosen Forrestal to succeed him at the head of his investment bank Dillon, Read & Co. where Forrestal also worked with the younger Dillon and Paul Nitze. In later years, Forrestal offered Dillon his first job in government.

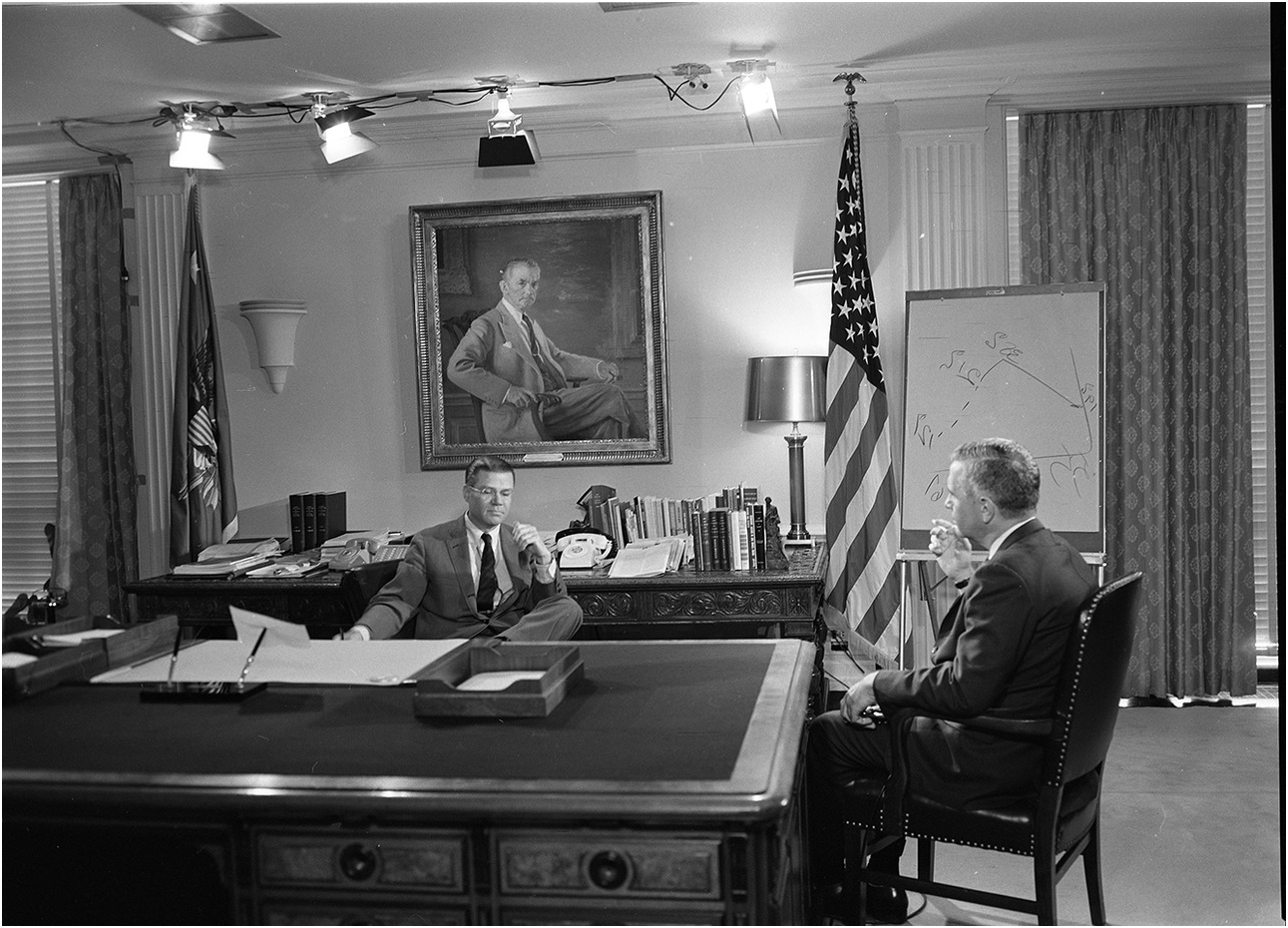

Forrestal’s failure to mold already entrenched service interests, or what Samuel Huntington termed “servicism,”38 and other resistances most haunted his successors. McNamara kept a large portrait of Forrestal above his desk (see Figure 1.1). In one telling exchange with President Johnson after several years in the job, the President complimented McNamara’s ability to maintain a stronger team than had existed in “Jim Forrestal’s time.” McNamara responded, “He wouldn’t have killed himself that’s for sure.”39 Forrestal’s failure to create unity primed McNamara’s tight control over and high expectations of loyalty from his subordinates.

Figure 1.1 Secretary of Defense McNamara sits down for an interview with CBS, September 19, 1963. A painting of former Secretary of Defense James Forrestal hangs in the background.

In a similar vein, during McNamara’s confirmation hearings as Secretary of Defense, the Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC), Richard Russell, wryly commented: “In the past, there have been partly humorous suggestions that being named Secretary of Defense merits condolences instead of congratulations; and, of course, it is true that any person who successfully discharges the duties of this position needs all the cardinal virtues, a double portion of fortitude, and some others.”40

The experience of Louis Johnson, Forrestal’s immediate successor, who served from March 1949 to September 1950, was hardly more encouraging. A lawyer by training, Johnson had been Assistant Secretary for War from 1937 to 1940, during which time he oversaw the wartime industrial mobilization. After the war, he had been a major fundraiser for Truman. Promising to “knock a few heads together,” Johnson announced that he would succeed where Forrestal had failed, particularly in achieving greater unification and keeping the budget in line with, if not below, the President’s wishes.41

However, by trying to make a reputation as a “great economizer,” Johnson made enemies who subsequently made him the scapegoat for the Truman administration’s humiliation when it was caught off-guard and unprepared at the outbreak of the Korean War. His decision to focus relatively more on strategic air power, which he considered a cost-effective investment in security, alienated the Navy, who staged a major protest that became known as the “Revolt of the Admirals.” In general, his inclination to ignore the advice of military colleagues meant that they remembered him as “probably the worst Secretary of Defense.”42 His relationship with the State Department was no better: he feuded with his counterpart, Dean Acheson, who described him as “mentally ill” in reference to a brain operation Johnson had undergone to remove blood clots.43 At first, Johnson was philosophical about the criticisms aimed at him: “A public official, of course, must expect a good deal of criticism, particularly when he must take a stand on a controversial issue.”44 Nevertheless, he was eventually dismissed.

Johnson’s discharge came at a time when NSC 68, with President Truman’s approval, was gaining momentum across government and in the midst of the Korean crisis. Both created pressures for increased military spending to meet expanded worldwide commitments. In particular, NSC 68, the joint State–Defense document that Paul Nitze at the Policy Planning Staff in the State Department had primarily drafted, called for a “substantial increase” in military forces and for vast investments to match the growing Soviet threat.

Within two months of taking office as the third Secretary of Defense, George Marshall, the Army war hero and retired Secretary of State, championed a changed defense posture. In a nod to his predecessor, he explained:

Always there has been a drive to find scapegoats to shoulder the blame. The basic error, however, has always been with the American people themselves. The fault has been with their refusal to sanction an enduring posture of defense that would discourage aggression, and, if war came, would reduce the casualties, the sacrifices, the excessive costs and the needless waste.

Echoing an argument James Forrestal had made, he criticized the “emotional instability” of the American people and their legislators who pushed for massive demobilization (a “violent dip”) after the war despite being “in the midst of a dangerous world.”45

When Marshall left, he insisted that his Deputy, Robert Lovett, succeed him as Secretary of Defense. A banker before the war, Lovett had directed the buildup of US air power during the war as Assistant Secretary for Air in the War Department, after which he had worked on the Marshall Plan. He shared Marshall’s view about the American tendency to neglect defense, explaining that “we seem to have had only two throttle positions in the past: wide open when we are at war and tight shut when there is no shooting.”46

Lovett oversaw the Korean buildup and, more than any Secretary of Defense, played a central part in raising the United States’ level of military readiness to respond to the Cold War and the growing potential of limited war. Echoing a rhetoric that would become commonplace and that would justify a growing defense budget throughout the Cold War, he explained: “We must make an effort to get the only insurance that works – strength. We tried peace through weakness for generations, and it didn’t work.”47 At the same time, as a progressive Democrat who understood that defense drew on finite governmental resources that could instead be earmarked for domestic issues, he explained how a longer-term level of preparedness would be cheaper in the longer term: that “less money annually, but steadily, can accomplish much more than huge sums today and nothing tomorrow.”48

Although his tenure was relatively smooth and free of controversy, Lovett closed the Truman administration’s chapter for defense policy by raising concerns about the organizational arrangements for defense, warning his successor that the 1949 Amendments had not solved inherent tensions between the Secretary of Defense and the JCS and that the budgetary process was still not efficient and economical enough.

At this critical juncture in the history of the OSD, General Eisenhower was elected as President, an exceptional presidency in many respects especially for defense policy. In addition to promising a prompt end to the Korean War, Eisenhower campaigned on the pledge to restore fiscal responsibility to government. As one of the most decorated generals in US history and as the first Chairman of the JCS, Eisenhower had a keen interest in defense policy. Although he had three Secretaries of Defense during his two terms, in reality, Eisenhower was his own Secretary. Moreover, as someone who had commanded or served with many of his Chiefs and senior military officers, Eisenhower was a special President and could more easily overrule his military advisors, something he did repeatedly.

Having been consulted at various points in the Defense Department’s nascent years, Eisenhower was quick to identify and act on its structural problems. He was inclined to support greater unification because of his experience as Supreme Allied Commander in the war and at NATO, while his fiscal conservatism moved him to act on more efficient budgeting practices. As he explained to a friend shortly before his inauguration in 1953, Eisenhower’s attitude to defense and to security was grounded in this attitude to federal spending: “The financial solvency and economic soundness of the United States constitute the first requisite to collective security in the free world. That comes before all else.”49 In practice, although he set up a number of structures and reforms aimed at reducing expenditures, his budgets “were never as austere as he made out.”50

Still, in a spirit of managerial reform, in his first year in office, Eisenhower asked the banker David Rockefeller to chair the “Committee on Methods of Reorganizing the Executive Branch for the Federal Government,” which also included Robert Lovett and General Bradley. Among its recommendations, many of which would inform the administration’s congressional moves, the committee suggested centralizing authority at the OSD with respect to research, logistics and procurement decisions, and at the level of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

Perhaps Eisenhower’s most important innovation was to strengthen the NSC as a way of enforcing his fiscal discipline and bringing defense expenditures down. The NSC was expanded to include the Secretary of the Treasury and the Bureau of the Budget, which participated in spelling out a Basic National Security Policy that was meant to inform the military department’s budgets within an overall ceiling, although Eisenhower tactfully called them “targets” instead.51

If Truman’s last Secretaries of Defense lamented the lack of investment in defense, Eisenhower’s first Secretary of Defense, Charles Wilson, swung the pendulum decidedly in the other direction. Coming from General Motors, which he had led for over a decade, Wilson controversially quipped during his confirmation hearings that “What’s good for General Motors is good for the country.” In addition to being the largest US corporation at the time, General Motors had been a major supplier of military equipment during the war. The comments exacerbated criticism leveled against the Eisenhower administration that out-of-touch businessmen dominated it or, as one critic put it, that it was an administration with “seventeen millionaires and one plumber” with Secretary Wilson as the “businessman ne plus ultra.”52

Wilson ruffled the most feathers as he searched for savings. He drastically cut appropriations without consulting the Chiefs as he presumed they would continue to ask for much more than could be realistically appropriated. Within four months of taking office, he cut 40,000 civilian employees in the Defense Department. In addition, he designed the administration’s new strategy, “the New Look,” with the NSC and not with the JCS. The New Look focused heavily on nuclear weapons and thus prima facie favored the Air Force. The Army, which had historically supported unification, now, under the stewardship of Maxwell Taylor, turned decidedly against it in a confrontation that the New York Times dubbed the “Revolt of the Colonels.”53 All in all, in his steadfastness to achieve savings and his inability to communicate constructively with the Chiefs, Wilson’s tenure was an acrimonious one.

In October 1957, the industrialist and former President of Proctor & Gamble, Neil McElroy, replaced Wilson. During his two years in office, and under the impetus of Eisenhower, McElroy oversaw the most important legislative reform of defense organization since the war: the Department of Defense Reorganization Act of 1958. The act gave President Eisenhower virtually all he had asked Congress for and laid the groundwork for McNamara’s changes to the department. It placed defense policy and notably the budget in civilian hands in order to balance each of the service’s needs while keeping in mind administration-wide fiscal priorities. As the act read, it aimed “to provide for the establishment of integrated policies and procedures for the departments, agencies, and functions of the Government relating to the national security.” Reflecting the administration’s concern about the role of the defense budget in federal spending, it sought “to provide more effective, efficient, and economical administration in the Department of Defense.”54

Overall, the Secretary of Defense’s power was substantially increased. The act “provide[d] a Department of Defense, including the three military Departments of the Army, the Navy (including naval aviation and the United States Marine Corps), and the Air Force under the direction, authority and control of the Secretary of Defense” and increased the staff at the OSD and the JCS. The Chairman of the JCS was given voting rights on the JCS, changing his role to one with clearer executive responsibility. The services themselves were changed from departments that were separately administered to departments that were separately organized under the authority of the Secretary of Defense. In other words, the services now reported to the President through the Secretary of Defense. However, in spite of McElroy’s objections, the act preserved the right of the Service Secretaries and Chiefs to make recommendations and to express independent opinions to Congress; it maintained the “legislated insubordination” that had troubled him and every other Secretary before and after.

Finally, as Eisenhower had suggested, the act “provide[d] for the unified strategic direction of the combatant forces, for their operation under unified command, and for their integration into an efficient team of land, naval, and air forces.” By setting up a new system of unified commands under the direction of the Secretary of Defense and the President, the act cut the Chiefs’ authority across horizontal lines as well.55

The first Secretary of Defense to benefit from these changes, although he did not act on them in any significant way, was Thomas Gates. A former banker and Secretary of the Navy, Gates had hoped to return to banking until the untimely death of Deputy Secretary of Defense Donald A. Quarles, who was on track to replace McElroy, forced him to reconsider his plans. In many ways, Gates’ tenure was a caretaking one but one during which the tone was set for the arrival of McNamara. Gates passed the Defense Reorganization Act and turned attention to the growing salience of limited wars in the nuclear age.

Building on an intellectual and legislative context that was open to questioning the Defense Department’s position and structures, Eisenhower took two final steps before leaving office. First, in 1960, he appointed New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller to review the organization for defense and to present his findings before the Jackson Subcommittee on National Policy Machinery. In his report, Rockefeller recommended greater centralization around the office of the President and presented an ideal Secretary of Defense as a “management specialist” who could faithfully implement presidential directives through “active management.”56 The report also suggested one of the reforms that would make McNamara famous, namely that the defense budget should be organized according to themes and defense functions rather than by services.57

Second, Eisenhower’s departure speech was decidedly pedagogical and warned Americans of the dangers that their new defense establishment could represent to the country’s economic health. He reminded the public that the “conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience” and had been “compelled,” and he warned of the “potential for the disastrous rise” of “unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought by the military-industrial complex” in “the councils of government.”58 The speech went on to expand on a related theme, namely the danger that federal spending could increase to a point that it would crowd out private entrepreneurial efforts in science or indeed in any field. He explained that “It is the role of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system – ever aiming towards the supreme goals of our free society.”59

Eisenhower’s successor, John F. Kennedy, demonstrated a lively interest in defense policy during his campaign. He had set up a Special Committee during the transition to study “how to strengthen the Defense Department and make it more responsive to the needs of our time” and chose Senator Stuart Symington as its Chairman. A one-time competitor for the Democratic nomination, Symington converged with Kennedy on the issue of a possible “missile gap” that Eisenhower had allowed to open by emphasizing fiscal prudence over military strength.60 Symington, who had been the first Secretary of the Air Force under Forrestal, turned to his old friends and associates from the Truman administration.61 The Committee’s final report reiterated many of the positions that Symington had championed since his days at the Air Force. These included recommending the unification of the services under a single chief of staff and the wholesale reorganization of the armed services into functional commands, for instance with one concerned solely with nuclear weapons and another with limited war. The report was greeted with predictable hostility in the services and much of the Congress, and the incoming administration privately deemed it “not feasible.”62 Publicly, Kennedy’s reaction to the 5,000-page report was more diplomatic: he told the waiting press that it was “an interesting and constructive study which I know will be carefully analyzed by the Congress and the incoming Administration.”63

Within the transition team, Richard Neustadt, the famed political scientist of presidential power, echoing the Army and Secretary Gates’ response to the Symington report, wrote to the incumbent President that he should focus on the “far-reaching potential”64 of Eisenhower’s legislative legacy. He wrote that “27 months after the passage of the 1958 Act,” the Defense Department was in a “transitional period” and explained to the President that “steps towards unification have been made necessary” by two imperatives: “One, to bring better business management to the massive operations of the Defense Department and thereby to effect efficiencies and prevent waste in the activities that have come to consume more than half the Federal expenditures and, two, to accommodate military strategy and operations to the technological revolution in warfare that has marked the past two decades.” The challenge for the administration was to organize the defense establishment in the “most economical and efficient manner possible … in a framework of responsible civilian control.”

Although Neustadt favored making the most of the 1958 act as a first step, he nevertheless proposed a number of bureaucratic steps and changes that went well beyond the act as a sort of menu for the incoming administration. These steps included converting Secretaries of the military departments into Undersecretaries of Defense or abolishing them altogether, and getting rid of the Chiefs’ dual responsibilities to their departments and the JCS. Neustadt also reiterated many of Symington’s recommendations, including “restructuring the military departments into functional organizations” and creating a single chief of staff, even while he accepted that the latter “is the most controversial step” and that the wholesale merger of the services “the most controversial of all … a most extreme degree of unification.” All in all, although Neustadt and his colleagues in the transition team accepted that the 1958 act had established a framework for reforming the Defense Department, they did not exclude further and more aggressive moves.

As far as staffing arrangements at the OSD were concerned, Neustadt explained, “The main present need is not further legal structural changes but improvements in the programming, budgeting, another decision-making processes and in the staff arrangements to get on top of the remaining difficult problems.” The administration needed a first-class manager of people and processes. He suggested to the new President that key bureaucratic changes were needed at the OSD, whose “central defect” was the “lack of civilian advisors.” A Secretary of Defense aided by civilian advisors should work toward a “fundamental overhaul of the Department’s budgetary processes to achieve a sound management framework.”65

Robert Lovett, who had served as Truman’s last Secretary of Defense and who was initially offered the job but declined, suggesting Robert McNamara in his place, shared Neustadt’s views. Together with Charles Wilson, Eisenhower’s first Secretary of Defense, Lovett counseled the transition team and described the ideal candidate. He argued that the Pentagon needed an “analytical statistician who can tear out the overlap, the empire building.”66 He later explained his choice of Robert McNamara to fill these shoes by saying that there were “very few people who were competent to deal with the basic problems in the Pentagon which was getting into the unnecessary duplication and the over-layering which had grown up under our system of operation. I felt that there should be a really careful analysis of the Department and that statistics should be developed which might help in pointing a way to a solution.”67

Both Neustadt and Lovett’s remarks illustrate how ill-defined the role of the Office of the Secretary of Defense was and just how much in “transition” it was when McNamara came to Washington. As one of McNamara’s predecessors, Lovett had first-hand experience of the problems that would confront the new Secretary. The administration needed a candidate with the managerial and budgetary vision to implement Eisenhower’s reforms and to deal with the inevitable and ongoing bureaucratic resistance.

Neustadt and Lovett also implied that achieving “civilian control” would depend on appointing a manager who could be completely loyal to the President and who could, in turn, inspire the loyalty of his own advisors. Moreover, the transition team counseled that the ideal Secretary would come from the private sector, bringing managerial experience, but without appearing to be part of the military-industrial complex that Eisenhower had spoken about. The Kennedy campaign latched onto criticism of the Eisenhower team, and his Secretaries of Defense in particular, as being an administration dominated by business people. In later years, McNamara was explicitly compared to his predecessors in this respect: one wrote, “Mr. McNamara is not subject to the family, socialite and public-figure consciousness of Neil McElroy … Nor is he subject to the Ivy League inhibitions and investment-trust dignity of Thomas Gates … Mr. McNamara simply isn’t susceptible to any pressures – social, military, intellectually, or editorial.”68

As the British Foreign Office observed at the time, appointments in the Kennedy administration put a greater “emphasis on a professional or professorial background” with “strikingly few connections with big business.”69 Although McNamara came from the Ford Motor Company, he also captured the spirit and tone of the New Frontier and became one of its iconic figures. As the journalist David Halberstam described, “Bob McNamara was a remarkable man in a remarkable era.”70

Much has been made of McNamara’s intellectual qualities, in particular of his quantitative logic and cold rationality. While his statistical skills made him stand out to people like Robert Lovett, for John Kenneth Galbraith and Adam Yarmolinsky (who with Kennedy’s brother-in-law Sargent Shriver led the staffing task force of the transition team), it was McNamara’s sense of public service that distinguished him most.71 On paper, McNamara’s professional journey was one that fit the stereotype of the quantitative-minded manager. However, his CV belied a greater degree of intellectualism and interest in public service. As Halberstam put it, “challenges fascinated him, but not worldly goods or profit as ends in themselves.”72

Born in San Francisco to a modest family, McNamara attended public schools and the state university at Berkeley before going on to Harvard Business School (HBS) for a Master of Business Administration degree. After spending a year at the Price Waterhouse accounting firm, he returned to HBS as its youngest assistant professor where he taught a course on planning and control from August 1940 until January 1942. In so doing, he contributed to the school’s groundbreaking work on the application of statistical methods and quantitative data for the purpose of management. Newly married, McNamara described living in Cambridge “more happily than we had ever dreamed possible.”73

He left Harvard on unpaid leave to join the war effort and apply his work in academia to public purposes. He worked for Robert Lovett, then Assistant Secretary of War for Air, in the Army’s Department of Statistical Control under Charles B. “Tex” Thornton reviewing the Army Air Force’s bombing campaign, and eventually served under General Curtis LeMay in the Eighth Air Force.74 McNamara and his team of “whiz kids” applied the statistical methods they had developed at HBS to strategic bombing and, in so doing, improved both the efficiency and lethality of the air strikes.

After the war, McNamara hoped to return to Harvard and to the intellectual excitement that he had enjoyed there. However, when he and his wife Margaret contracted polio, their “very, very expensive”75 medical bills forced him to choose a more profitable path. Although he was not particularly drawn to business – in fact, his first response to Thornton’s suggestion to go into the corporate world was an “unequivocal no”76 – the “whiz kids” including McNamara brought their skills to the Ford Motor Company and overhauled the company in the ensuing decade. Building on his course at HBS, McNamara became director of planning at the company.

However, at Ford, McNamara chose a lifestyle that was more academic than it was corporate: he described himself as “a motor company executive who seemed an oddball for Detroit.”77 Whether or not his intellectualism was “self-conscious,”78 the McNamaras chose to live in the university town of Ann Arbor rather than Detroit and preferred local book clubs to golf clubs. In his job as well, McNamara did not fit the typical model of the corporate leader: he was instrumental in improving the cars’ security record and in pushing social responsibility measures at time when they were rare, as well as in building up the Ford Foundation in its formative years.79

On November 9, 1960, the day after the election, McNamara was promoted to become the first President of the Ford Motor Company who was not a member of the Ford family. As McNamara later explained, he “was one of the highest paid industrial executives in the world, not wealthy, but in a position to become so.”80 Although he declined the administration’s first offer to serve as Secretary of the Treasury, it was not long before he accepted to serve as Secretary of Defense even while he admitted that he only “followed defense matters in a rather superficial way through the press.”81 Despite his “deep loyalty to [the Ford family] and to the Ford Motor Company,” McNamara explained, “I could not let their interests outweigh my obligation to serve the nation when called upon.”82

In addition to providing a platform for public service, the OSD provided an intellectual challenge. McNamara told a New York Times reporter: “I think each large organization goes through a period of evaluation when the patterns of the future are formed, when the intellectual framework for decisions is established, when the administrative techniques are sharpened, when the organization structure takes shape[;] I believe that the Department of Defense is in such a period today.”83 After successive leaders’ attempts at “trimming,” McNamara was determined to press on with bottom-up reform.

McNamara accepted Kennedy’s offer on two conditions, both of which were largely met. First, that he “would have the authority to organize and staff the Defense Department with the most competent men [he] could find without regard to political affiliation or obligation.” Barring some Service Secretary positions, this condition was largely upheld. McNamara’s second condition spoke to the campaign and transition team’s intellectual approach to the department. Although McNamara agreed with “the premise” of Symington’s report, he “felt that it was extremely unlikely that the report, or any significant part of it, could be implemented politically.”84 As a result, he asked that “during at least the early part of my term (i.e., approximately the first year), I would not be obligated to undertake a major reorganization of the Defense Department of the type recommended in the Symington Report.”

A final and implied third condition was his “belief that the Secretary of Defense, in order to succeed, must have the closest possible, personal working relationship with the President and must receive the President’s full backing and support so long as he is carrying out the policies of the President.”85 Just as his success at the Ford Foundation rested on his personal loyalty to the Ford family, his loyalty to Kennedy determined his efforts to bring military bureaucracies and power under civilian and presidential control.

The congressional leaders who had pushed through the 1958 act welcomed the arrival of a Secretary who was prepared to deliver on its promise. Richard Russell applauded McNamara’s efforts, saying: “It is gratifying to note that the Secretary is making use of the authority the Congress has vested in him to streamline the Defense Establishment as it has been the position of this committee that the Secretary of Defense needs no additional authority to accomplish desirable changes but need only exercise the authority given him by the Congress. It is hoped that such changes as have been made and others yet to be accomplished will go far to eliminate many of the examples of wasteful duplication and competition between the services which have all too frequently come to the attention of the committee.”86

In a similar vein, his counterpart in the House, Carl Vinson, added, “He’s a genius, the best who’s ever held the job.”87 While both Chairmen were Democrats, admittedly southern conservative Democrats, McNamara also provided a measure of protection from Republicans. Even the most conservative members of the committees, including Barry Goldwater, appreciated McNamara, who had been a nominal Republican although he had voted for Kennedy. Republicans were generally satisfied with his skills as a manager and only later became frustrated when he cut into R&D projects in their constituencies or in ways that they felt could undermined the US position vis-à-vis the Soviet Union.88

Looking back on his arrival at the OSD, McNamara remarked that the two most pressing needs that he confronted were to align policy and strategy to force structure and to integrate the different parts of the department. He recognized that his predecessor, Thomas Gates, had been moving in that direction, “but the linkage between foreign policy and the defense budget was totally lacking.”89 Instead of following the rather more political avenues that Symington had suggested, McNamara chose Neustadt’s recommendation to capitalize on Eisenhower’s reforms and centralize authority around his office, notably through the budgetary process, as “a substitute for unification of the services and the establishment of a single chief of staff.”90

As this brief history of the OSD has shown, by the time McNamara entered the Pentagon, the nature of civil-military relations had evolved on two fronts. First, civilians had progressively implemented greater control over their military counterparts in designing policy and strategy. Through various permutations, the power relationship between the JCS and the Secretary of Defense had become clearer and leaned decisively in the OSD’s favor. Second, the defense establishment and its budget had become a central part of the federal government. Yet the debate about “how much is enough” raged on, especially in determining the exact process by which civilian objectives and service budgets could be reconciled.91

McNamara’s revolution at the OSD in the 1960s intensified this process on both fronts. In the spring of 1962, McNamara proudly submitted his first budget for FY63, the first budget that demonstrated his transformation of the budgetary process and that showcased his “tearing into” the inefficiencies at the Department of Defense. He could proudly look forward to cost savings in the coming years. At about the same time, the issue of Vietnam landed on his desk as President Kennedy leaned on his “dynamo” of a Secretary to bring order to another messy challenge for the administration.

Too often, historians have evaluated McNamara’s contributions to Vietnam through diplomatic and military lenses and in binary terms, along neat dove/hawk lines that obscure an arguably more informative lens, namely how Vietnam might have been perceived from the vantage point of his office at a special time in its history. The bureaucratic influences on McNamara worked in contradictory and at times paradoxical ways. However, McNamara favored withdrawal and then resisted the growing US commitment to South Vietnam because of, not in spite of, being Secretary of Defense. By mapping how McNamara defined his job, his policy recommendations on Vietnam begin to make much more sense.