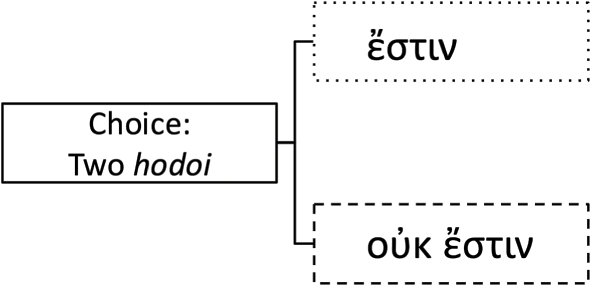

We discussed in the Introduction how a Foucauldian theoretical apparatus could help us identify and examine the specific discursive connections linking Parmenides to Homer, extended deductive argumentation and demonstration to narrative poetry. In fact, I shall hone in on a rather a small subset of the grand archaeological system that Foucault details in his Archaeology of Knowledge. There, in section II of chapter 5, devoted to ‘The Formation of Concepts’, one finds a discussion of ‘forms of succession’, the different sets of patterns or rules that dictate the arrangement of statements in their sequence.Footnote 1 Foucault identifies three ‘forms of succession’, and these will provide the framework for the rest of this chapter and much of what follows in the rest of the book.Footnote 2

After addressing the Foucauldian apparatus briefly, I shall then spell out my purposes in using these terms in the remainder of the book; my strategy will be to contextualize each of these three ‘forms of succession’ within the existing field of scholarship on Homer and narrative more generally (Section 3.1, ‘The Theoretical Apparatus in Context’). I shall then put these terms to work by examining the text of the Odyssey more generally (3.2, ‘How the Hodos Organizes Homeric Discourse’) before addressing the portion of that text most crucial for Parmenides, the first half of book 12, in Chapter 4. What will emerge is that the hodos has the capacity to organize the shape and structure – the ‘forms of succession’ – of a discourse, in this case Homer’s text, in a distinctive way. I shall ultimately argue that the shape and structure of the discursive organization delineated in this chapter provides a blueprint of Parmenides’ groundbreaking extended deductive argumentation, the topic of chapters 5 and 6.

Perhaps the most important level of analysis of the ‘forms of succession’ is the most macroscopic of the three, the level of the ‘rhetorical schema’. Foucault defines this as the rules or patterns according to which ‘descriptions, deductions, definition, whose succession characterizes the architecture of the text, are linked together’.Footnote 3 A core claim developed in chapters 5 and 6 is that one of the main levels of continuity between the first half of Homer’s Odyssey 12 and Parmenides’ ‘Route to Truth’ is to be found at the level of the rhetorical schema. Tracing this continuity will give us a decisive insight into both Parmenides’ strategies for refashioning his ‘new way of thinking and knowing’ and the underlying ‘architecture of the text’ that determines the shape and structure of his extended deductive argument.

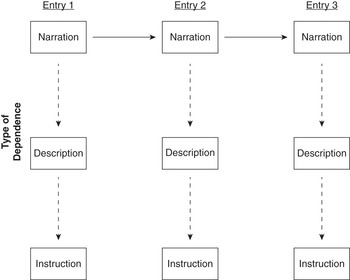

The second and third levels Foucault articulates are the ‘ordering of enunciative series’ and the ‘levels of dependence’, respectively. The categories discussed under the rubric ‘ordering of enunciative series’ are in fact the same categories that elsewhere traffic under the name ‘Discourse Modes’, ‘Text-Types’, or, more traditionally, ‘Rhetorical Modes’.Footnote 4 In Foucault’s scheme these are three in number: we may refer to them here by their more familiar names, ‘narration’, ‘description’, and ‘argument/inference’. Foucault does not define the ‘levels of dependence’, electing instead simply to exemplify them; the examples given include ‘hypothesis/verification, assertion/critique, general law/particular application’. Although Foucault stresses that ‘types of dependence’ between units of statements need not be ‘superposable on’ the categories that comprise the ‘orderings of enunciative series’, that is in fact precisely how I wish to make use of these categories in the analysis to come. More specifically, I shall take the ‘orderings of enunciative series’ as the base units of analysis in my discussion of various hodoi elaborated in the course of the Odyssey, and, with these in hand, shall attempt to see how the rhetorical schema governed by the figure of the hodos determines an overarching pattern of organization – a discursive architecture distinctive to the figure of the hodos – out of these base units.Footnote 5

If it is dry work to summarize technical aspects of Foucault’s system in the abstract, the application of this schema in what follows will make it clearer what precisely is meant by the terms in question, and how they work. I shall undertake this in Section 3.2; the next step, however, is to anchor Foucault’s apparatus in current discussions in Homeric scholarship.

3.1 The Theoretical Apparatus in Context

3.1.1 The oimē, Themes, and Rhetorical Schemata

At first glance, Foucault’s notion of a rhetorical schema might be thought to approach two topics in Homeric studies: the use of metapoetic devices, and so-called catalogic discourse. The latter we shall explore below (see Section 3.1.4); the former we shall examine here, in large part to clarify one way in which I do not intend to use Foucault’s term when discussing epic poetry.

Scholars have discerned a number of metapoetic images at work at various points in the Iliad and the Odyssey. According to one view, the poem is a craft production, an object constructed in the manner of Odysseus’ raft, for example, or his well-made bed.Footnote 6 According to a more well-developed tradition, the Homeric text has been seen to emerge at the intersection of imagery related to weaving and sewing.Footnote 7 The unavoidable point of comparison in this context, however, is the oimē, or ‘path of song’.Footnote 8

Although there may seem to be many tantalizing similarities between the oimē as a metapoetic figure and what we shall examine under the rather cumbersome name of the ‘rhetorical schema of the figure of the hodos’, caution must be exercised.Footnote 9 One prominent conceptualization of the oimē takes each particular segment of the path to be a ‘theme’ in the Parry–Lord sense;Footnote 10 the idea is that these oimai are ‘tracks cut into the landscape’ that link together end on end and, taken collectively, define a ‘map’ of Epos.Footnote 11 Are these oimai, perhaps, coextensive with Foucauldean rhetorical schemata?

The answer, at least in this book, is no. The reason the answer is no depends in part, however, on just what it is that one means by oimē. The way that the word is used in the Odyssey suggests that an oimē in fact comprises a relatively large unit. Demodocus’ postprandial performance, described in terms of an oimē in one of only three passages where the word appears in Homer, encompasses ‘The Quarrel of Odysseus and Achilles’; later, Odysseus will ask him to ‘move along [the path of song] and sing “The Fashioning of the Wooden Horse”’.Footnote 12 These are both apparently rather lengthy productions; if that is the case, their scale is larger than that to which the rhetorical schema of the hodos will refer. (For comparison, Circe’s foretelling of Odysseus’ hodos in Odyssey 12, the central example of the rhetorical schema of the hodos that I examine below, occupies slightly more than 100 lines (12.27–141) of the four books of aoidē Odysseus makes it through in a single evening with the Phaeacians; one hardly imagines that Demodocus discharges his duties with such brevity.) On this understanding, an oimē would seem to be something considerably longer than the amount of text governed by a rhetorical schema, at least as we find it in Homer.Footnote 13

Other discussions of the oimē emphasize the idea that it is something that a poet can hop on or off at any number of points along the grand path of Epos as a whole. On this view, as a poet performs, ‘no matter how small the scale of the performance’ he or she would simply be on the oimē, the ‘path of song’, in virtue of orally performing a poem.Footnote 14 There is an important question, not always clearly expressed, about whether this idea should focus on the word-by-word, line-by-line process of bardic composition, or whether individual units on this larger epic path of song correspond to something closer to a Parry–Lord ‘theme’.Footnote 15

In the first case, the claims scholars have made about the way that the structure of a text conforms to certain patterns – and is perhaps even dictated by certain rules – are very much of the sort I shall develop below. Here again, however, there is an important difference of scale. This strand of analysis of the ‘path of song’ addresses units of text – phrases and lines – of a smaller scale than I intend to investigate via the term ‘rhetorical schema’; rather, units of text of this size are better discussed under the rubric ‘types of dependence’, addressed in Section 3.1.3 below.

In the second case, it is possible to imagine the relationship between a theme and an oimē as corresponding to, or perhaps instantiating, a form of the narratological distinction between story and plot or narrative. This is an attractive hypothesis, and it opens a vista onto an exciting perspective of Homeric poetics. But any such relationship between story and narrative is also different in kind from the relationship I wish to capture under the term ‘rhetorical schema’. Why so? If, on the one hand, any theme can be expressed along the path of song (and, on this view, all themes necessarily would be) and, on the other, every path of song maps onto simply one or another of the ‘themes’ in the mythic repertoire, then the level of connection between the content of the story (the theme) and the manner in which it is narrativized (via movement along the path of song) as plot is necessarily a rather general one.Footnote 16 By contrast, as we shall see, the rhetorical schema governed by the hodos, at least as I examine it here, dictates a far more precise relationship between story and narrative. While it is undoubtedly valuable to combine the two understandings of oimē as ‘theme’ and ‘path of song’,Footnote 17 current scholarship on this topic allows for considerable flexibility in the relationship between the level of story and the level of plot – and this gap between the more macro structure of a theme and the micro structure of a visual poetics of the oimē is precisely the gap filled in part by the rhetorical schema that will be so important in what follows.Footnote 18

3.1.2 Text-Types, Discourse Modes, and Enunciative Modalities

Classic studies of text-types define these to be ‘underlying (or overriding) structures that can be actualized by different surface forms’.Footnote 19 On the traditional view, there is always a single, dominant (underlying or overriding) text-type that characterizes any given text. Because the roots of this approach to textual analysis are to be found in literary criticism, the text-type ‘narration’ has received the most attention and usually serves as the central, positively constructed term against which other text-types are negatively defined.Footnote 20 Two aspects of narration are usually deemed key characteristics: first, that narration depicts ‘events or sequences of events’ and, second, that the ‘order in which events happen is significant’.Footnote 21 By contrast, description is ‘oriented to the statics of the world – states of affairs, enduring properties, coexistants’;Footnote 22 it often introduces elements of the story-world – persons, places, things – and/or attributes qualities to these elements.Footnote 23

While in the case of narration the text’s underlying progression is primarily temporal, in the case of description the text’s underlying progression is primarily spatial.Footnote 24 Scholars have often claimed that important implications follow from this. As noted, the narration of events whose temporal order is significant endows their narration with ‘a natural principle of coherence, one that enables the narrator to construct his presentation sequence … according to the logic of progression inherent in the line or chain of events itself; from earlier to later’; by contrast, and significantly for the analysis to be undertaken here, ‘the descriptive sequence’ is denied ‘any natural resource of coherence’.Footnote 25

More recently, the study of discourse modes, a linguistically inspired method of analysis, has emerged in parallel to the study of text-types.Footnote 26 The key insight animating this enterprise is that several features of the surface text preponderate in – or are understood to be the hallmark of – narrative or descriptive portions of text.Footnote 27 We may note three features.

First, verb forms. Tense-aspect in particular has long been recognized as ‘the most important distinctive linguistic feature’ associated with each of the text-types or discourse modes.Footnote 28 Reflecting the fact that narration is usually defined in connection with the notion of the event, the aorist and historical present are often intimately associated with narration; so, too, as we shall see, is the future tense when the narrative takes the form of a ‘prior narration’.Footnote 29 Person and mood also prove significant: description does not use the second person or the imperative mood, both of which can be found in narration.

Second, the notion that the underlying progression of the text is temporal in narration and inherently unordered in description has a correlate at the surface level of the text. This can be seen from two perspectives: from the perspective of the story and from the perspective of the plot. On the one hand, narrative portions of a text usually progress along with time in the story world; on the other, the passage of time in the story-world is most commonly expressed through, or recorded by, a sequence of narration. By contrast, movement through a descriptive passage does not necessarily suggest the passage of time in the story-world, nor does the passage of time in the story-world necessarily register in passages of description.Footnote 30

Third, textual progression is often marked by temporal adverbs (or combinations of temporal adverbs and specific particles) in the case of high-narrativity portions of text. On the other hand, spatial adverbs (or combinations of spatial adverbs and specific particles) predominate in high-descriptivity sections.Footnote 31

So much for narration and description. What of argument? In fact, typologies of ‘argument’ are much harder to produce. There are three obstacles. First, the topic is under-researched, and analysts of discourse modes or text-types have simply not devoted much attention to differentiating ‘argument’ from ‘description’ or ‘narration’.Footnote 32 Second, in cases where analysts have undertaken this task, their definitions of ‘argument’ are usually so inextricably bound up in a formal, modern understanding of what constitutes an argument that it is difficult to apply such a category to a pre-Aristotelian text like the Homeric poems.Footnote 33 The third stems from Parmenides’ own role in developing argument (and, specifically, extended deductive argument) and the fact that he is a key point of transition in the forms that an argument might take. Since this very transition is the central topic under investigation here, as noted in the Introduction, deciding what constitutes an ‘argument’ without already assuming the accomplishment of the phenomenon whose development we are attempting to observe is a problem.

For the purposes of this project, I shall consider a portion of text to instantiate an ‘argument’ discourse mode if it is formed of a cluster of statements that are linked inferentially; that is, if it is formed of a cluster of statements some of which explicitly provide a justification or rationale for others.Footnote 34 At the surface level of the text, argument sections will be particularly densely populated by conditional clausesFootnote 35 or purpose clauses, which tease out the implications of certain actions or justify pieces of instruction, and by specific usesFootnote 36 of epeiFootnote 37 and garFootnote 38 (to be examined in further detail below).

3.1.3 A-B-C Patterns, and Types of Dependence

Some long-standing conversations in Homeric scholarship, particularly classic studies on catalogues and battle scenes, provide important parallels for the notion of a ‘type of dependence’.Footnote 39 In the Catalogue of Ships, for example, every entry is organized in relation to (a) ‘nation/generals’, (b) ‘places’, (c) ‘number of ships’;Footnote 40 in some instances, further genealogical background for key protagonists is provided.Footnote 41 These categories can also be examined under a more general typology where anecdotes supplement the ‘basic information’ (e.g. names and places in the Catalogue of Ships) with biographical information, while ‘contextual information’ offers ‘what is relevant to the context’ in which the list occurs.Footnote 42

Somewhat more recently, Egbert Bakker has suggested that the so-called A-B-C pattern detailed above is the product of an oral compositional technique that operates through a process of ‘framing’ and ‘goal-setting’:Footnote 43 the basic information demarcates the frame of vision and ‘orients’ listeners as to the future direction of the text.Footnote 44 Detail ‘added’ to the ‘frame’ ‘lends depth and significance’ to the goal, which is the event presented.Footnote 45 By means of this repeated pattern of elements, the epic narrator opens up narrative space, provides direction, and intensifies the experience of listeners.Footnote 46

I shall argue in Section 3.2 below and in Chapter 4 that the rhetorical schema governed by the figure of the hodos makes available a framework of relationships between discursive units (i.e. its own distinctive ‘type of dependence’) that operates in a manner closely paralleling the A-B-C pattern and Bakker’s elaborations on it.Footnote 47 This framework need not be exploited but is available to be activated any time the figure of the hodos is mobilized, as Circe’s two long speeches in Odyssey 10 and 12 make clear.

3.1.4 Catalogues

Discussion of the A-B-C pattern brings us to one final topic of Homeric scholarship that needs to be addressed: the notion of catalogic discourse. A great deal has been said about this topic, its relationship to oral composition, the development of epic narrative forms, and its cognitive functions and their place in a society that is either preliterate or largely so.Footnote 48 Scholars have discussed three principles of catalogic discourse that are pertinent in this setting: that there is some kind of underlying classificatory rubric according to which catalogued items merit inclusion in the catalogue;Footnote 49 that these items form the entries – often specifically delimited by ‘entry headings’ – that make up the catalogue;Footnote 50 and that these entries are enumerated sequentially.Footnote 51

It is this final point that will prove the most crucial for the remainder of this chapter, and indeed much of the remainder of this book. How are the entries to be ordered? There may seem to be two extremes. On the one hand is the list: ‘a list presents items that are more than one in number … and have something to do with each other; but quite unlike narrative, the order of its items may be reversible or subject to free transpositions … the actual order of entries need not follow any scheme or have any obvious significance.’Footnote 52 On the other hand is what we might call a series, where the order of the items catalogued is not reversible or subject to free transpositions but is strictly determined according to some rule or principle. An example of a Homeric list would be the catalogue of Nereids at Il. 18.38–49; is there any sense that it matters whether or not Glauke comes first, Amatheia last, and Doto and Proto in the middle? By contrast, an archetypal epic series can be found at lines 133–53 of Hesiod’s Theogony (or even the parthenogenic portion at lines 126–32). There is simply no question of Gaia coming after, say, Cronus or the Cyclopes (or even the mountains or Pontus): because she begets them, she must plainly precede them.

3.2 How the hodos Organizes Homeric Discourse: Forms of Succession

Ulysses’ journey, like that of Oedipus, is an itinerary. And it is a discourse, the prefix of which I can now understand. It is not at all the discourse (discours) of an itinerary (parcours), but, radically, the itinerary (parcours) of a discourse (discours), the course, cursus, route, path that passes through the original disjunction.Footnote 53

In the Odyssey, the successions in the narration are regulated by the scheme of the path, thus preserving the primacy of catalogic discourse.Footnote 54

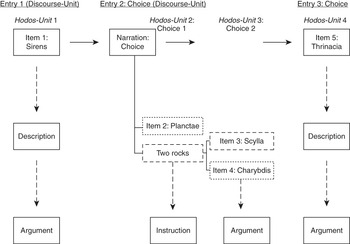

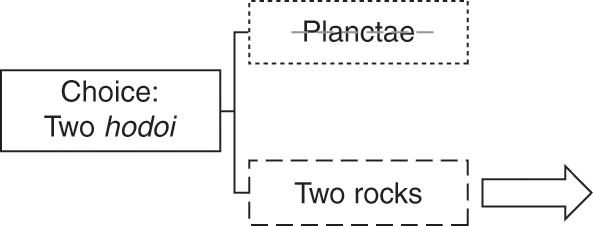

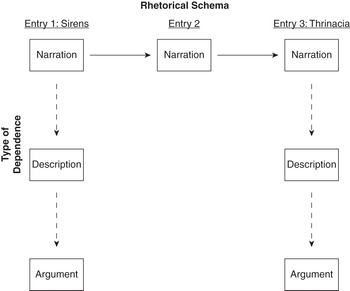

It is time to put these distinctions to work. My fundamental claim comprises the following components. The hodos, understood as a kind of catalogic discourse, structures the discursive architecture of portions of a text according to its own distinctive rhetorical schema; it yields a series, that is, by providing a set of rules or principles according to which items that form entries enumerated in the catalogue can be linked (articulating these rules or principles will be one of the main objectives of this chapter). This rhetorical schema in turn dictates its own distinctive manner of relating one to another the internal components that make up individual entries; this pattern will be examined in terms of a specific ‘type of dependence’. Finally, the base unit I shall consider for examination is the unit of the text that is defined by text-type or discourse mode, be it narration, description, or argument (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Summary of the framework: The hodos and forms of succession

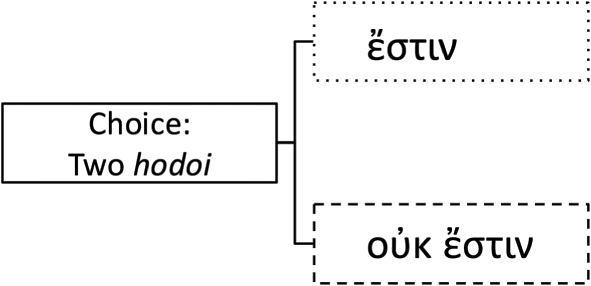

In chapters 5 and 6, I shall show how Parmenides reappropriates this framework for his own ends. More specifically, by retaining the rhetorical schema of the figure of the hodos but substituting claims about the nature of what-is in place of toponyms and place descriptions as the items that make up entries in the catalogic discourse of the hodos, he produced the first recorded sequence of extended deductive argumentation. Parmenides’ new creation will thus have the rigorous and clearly defined rules for sequential ordering of narration, as opposed to the ‘inherent unorderliness’ of description; it will also be made up of statements that address the statics of the world and its enduring properties, as opposed to actions and events. What we shall find, that is to say, is narrativity without narration and description without descriptivity – or, as we would call it, an extended deductive argument.

3.2.1 Catalogues: Constituting the Field of Statements

Understanding the discursive architecture governed by the figure of the hodos as a kind of catalogic discourse requires us to address three features of catalogues. First, catalogic discourse both demarcates the boundaries of a kind of closed set and structures the field of statements it encompasses in such a way as to facilitate the process of classification.Footnote 55 By grouping together a bundle of discrete entities – be they places, individuals, objects – within a single, unifying framework, catalogic discourse organizes the terrain of the field of statements in such a way as to suggest (or, from another perspective, presuppose) a kind of underlying conceptual unity that encompasses the items enumerated.Footnote 56 Second, the catalogic form can articulate the individual items it enumerates as discrete items by framing each entity as an ‘entry’ (with, furthermore, a particular quality that grants it membership in the catalogic set).Footnote 57 Third, by unifying in a single set the discrete entities it enumerates, the catalogic mode of discourse in general makes it possible to indicate the entire set and its component entities in a single shorthand.

An example may help illuminate these points. Unlike the later routes that traverse the fabulous spaces of the Apologoi, the journey Athena maps out in Odyssey 1 remains squarely within the bounds of the ordinary Greek world and is therefore perhaps the simplest, least elaborate journey spelled out in the Odyssey.Footnote 58 We discussed above (Section 1.2) the moment Athena sets the plot of books 1–4 in motion by proposing to Telemachus that he (Od. 1.284–91):

The sequential enumeration of the items – Pylos, Sparta, native land (Ithaca) – is evident. The lexical items that demarcate the entries and articulate the specific items, the pair ἐς and -δε (discussed above in Section 1.2), are equally clear. The underlying conceptual unity established across these items is a more complex question.Footnote 59

Third, the itinerary, with its clear point of origin (where we are now: in this case, Ithaca) and its precisely identified final destination (νοστήσας … ἐς πατρίδα γαῖαν), determines the boundary markers of a closed set, one that encompasses Ithaca, Pylos, Sparta (and Ithaca again). As a result of being fused into a single unit, the entire ordered sequence of places can be intensively summarized by the single word hodos (instead of requiring that each destination be listed extensively). Here the scene in book 1 proves particularly illustrative: two hundred lines and an afternoon’s worth of arguments with the suitors after Athena set the Telemachy into motion, we find Telemachus in his private chambers (Od. 1.443–44):

As a kind of catalogue, the hodos-itinerary marks out the boundaries of a category or the limits of a set. In the course of doing so it creates a distinct unit, the constituent elements of which can be summarized or indexed as a unit or as a bundle of different elements.

3.2.2a Rhetorical Schemata: The hodos Orders Places

The kind of discursive architecture organized by the figure of the hodos, then, is fundamentally catalogic in nature insofar as it enumerates items sequentially within a larger set susceptible to conceptual unification; in addition, it articulates the members in its set as discrete items through the catalogue’s system of ‘entries’. But what kinds of items fill entries in a catalogue, and what principles govern the order of the sequence in which they are enumerated? These are the two parameters that define the different species in the family of catalogues.

Some catalogues take as items the warriors of an army, and the principle according to which entries are sequenced is that of spatial contiguity.Footnote 60 Others take the trees in an old man’s garden sequenced according to a similar principle.Footnote 61 Yet others take living creatures as their items and order entries according to a principle of genesis or begetting: this is, of course, the genealogy. The genealogy is sometimes coupled with the hodos-itinerary as a complementary kind of catalogue, the former operating ‘temporally’, the latter ‘spatially’.Footnote 62 One can understand why (Od. 1.284–85, 291):

The items enumerated in this catalogue are toponyms (and therefore refer to places), and their position as an entry is demarcated by the spatially oriented lexical items (ἐς, -δε) that highlight them as such.Footnote 63

3.2.2b Rhetorical Schemata: The hodos Orders Places

Further consideration of the sequence according to which items in this mini-catalogue are enumerated, however, clearly reveals this simple binary between a ‘spatial’ and a ‘temporal’ conception of catalogic discourse to be incomplete. It is vital to appreciate here that the temporal dimension also plays an important role in configuring the rhetorical schema of the hodos; the figure of the hodos orders spatial relationships according to movement through space in time, with its linear, sequential flow. So, in the same example (Od. 1.284–85, 291):

This is where the distinction between a list and an ordered series becomes relevant: if the Catalogue of Ships orders men according to a principle of geographical (spatial) contiguity, we might imagine a Catalogue of Places that simply takes the toponyms, rather than the names of the warriors who dwell there, as the items in its entries.Footnote 64 Like the hodos spelled out by Athena, it, too, would be formed of items united by their underlying spatial nature. What we find above, of course, is something radically different: as the sequence of particles and adverbs πρῶτα μὲν … κεῖθεν δὲ … δὴ ἔπειτα makes explicit, the order in which these place items occur is not reversible or, as Sammons puts it, ‘subject to free transpositions’; rather, their sequence seems determined by an underlying principle or pattern. The hypothetical Catalogue of Places would, as a catalogue at least (and a repository of information), be the same whether it began with the poleis of Thessaly or Boeotia, whether the islands of the eastern Aegean led to those of western Greece or the other way around;Footnote 65 the Catalogue of Ships (or hypothetical Catalogue of Places) shares important features, that is, with the list.Footnote 66 By contrast, Telemachus’ itinerary would by no means be the same were he to begin with Sparta and return to Ithaca by way of Pylos – for a variety of reasons, logistical and narrative. The order of the sequence matters: the rhetorical schema of the hodos structures the items that form entries in a series. More specifically, it orders a series of spatial items (places) according to a temporal progression.Footnote 67

3.2.2c Rhetorical Schemata: Narrativity of the hodos-Itinerary

But what dictates the order of this progression? What principle or set of rules determines the order of the sequence by which may be enumerated the items that make up the hodos announced by Athena? We may note that closely tied up with the temporal dimension that is constitutive of the hodos-itinerary is the implicit need to move – in time – from one place-item to another. This element of action is another of the main aspects distinguishing the hodos from the hypothetical Catalogue of Places. Another look at the same passage reveals this activity-based dimension:

Above, we defined narration as ‘the representation of an event or sequence of events’, a sequence where, furthermore, ‘the order in which events happens is significant’.Footnote 68 Even stripped to its essentials, it is clear that the skeleton ‘[f]irst to Pylos, then to Sparta, finally home’ implicitly contains the ‘events’ ‘[f]irst [go] to Pylos, then [go] to Sparta, finally [go] home’. The progression of the text tracks this significance and marks it out explicitly with the string of temporal adverbs πρῶτα, κεῖθεν, ἔπειτα. Events are likewise presented in the aorist and/or imperative, features closely associated with the discourse mode of narration. It is thus the narrativity of this portion of text (as a result of which the ordering of events is significant) that imparts a necessary order to the sequential enumeration of places that make up entries in Athena’s hodos-catalogue.

3.2.3 Rhetorical Schemata and Types of Dependence: A Temporally Ordered Sequence of Places as a Framework for Description

That is not all, however. The story is more complex. So, too, is the first hodos that Circe delineates for Odysseus, the one we find in Odyssey 10. It may take no special knowledge to sign out the path from Ithaca to the mansions of Nestor and Menelaus on the familiar terrain of the Peloponnese; what emerges there is the significance of the sequence in which these visits are ordered. The same is not true of the route from Aeaea to the Underworld – for, as Odysseus laments, ‘no man has ever yet travelled to Hades in a black ship’ (Od. 10.502). Circe gives the following set of directions in response (Od. 10.505–16):

In this passage, we see on display the hallmarks of the discursive structure governed by the hodos: a bounded range of places ordered sequentially (the end of Ocean and the fertile shore; the hinterlands of Hades; the confluence of Pyriphlegethon and Cocytus into Acheron and rock) in a unified set. This sequence is dictated by a narrative framework, one in which movement through space in time imparts a specific order to the sequences: (first, depart from here), then, when (ὁπότε) you have crossed the ocean you will find a thickly wooded shore, then from there go to the rock/confluence of Pyriphlegethon and Cocytus; then … etc.Footnote 69

We may, however, note two important points, one concerning the level of rhetorical schemata, the other the level of types of dependence. At the level of rhetorical schemata, we have seen that it is movement through space in time that imparts the specific shape to the order of the items sequenced by the hodos as catalogic discourse. But this example urges us to take proper account of the fact that this is movement through space in time, and to pinpoint the ways this spatial dimension exerts its own influence on the possibilities for ordering the items that make up the catalogue of a hodos-itinerary. In the hodos to the Underworld, the scarcity of any temporal indicators imposing a temporal sequence on the catalogue at the level of the text brings out the underlying order inherent in the enumerated items themselves. Not only are both the spatial and the temporal dimensions of the pattern by which the hodos orders its sequence distinct and irreducible one to the other, but this spatial dimension is topological: that is, we understand space here from the perspective of the spatially contiguous, rather than absolute Cartesian space.Footnote 70

Let us consolidate observations made so far at the level of rhetorical schemata. Crucially, the rhetorical schema of the hodos has a fundamental narrativity insofar as what it depicts are events or actions, and, characteristically, the sequence of these actions or events is significant. The order in which these events or actions are sequenced in turn depends on two parameters. The underlying geography of the space traversed – specifically, the contiguity of the places where events or actions occur – determines the matrix of possible combinations this sequence can take. Movement through this space in time in turn determines one sequence or imposes a clear shape and form on the set of possibilities determined by the underlying geography of the space traversed. That is, the hodos dictates a series insofar as, by adding a dimension of ordered temporal sequentiality, it generates what we might strategically call spatio-temporal con-sequence out of spatial contiguity.

At the surface level of discourse these features are reflected in a number of characteristic ways in the Homeric examples so far examined. First, the verbs linking the units ordered by the rhetorical schema of the hodos are in some combination of the aorist tense-aspect (as one would expect with events and actions), the imperative mood, and the second person. Second, the combinations of adverbs and particles indicate the progression of the text according to a sequential pattern (and, especially in the hodos described in Odyssey 1, a largely temporally determined sequence). But this is because, third, the progression of the text tracks the sequence of the underlying story, which is itself ordered according to a temporal progression through spatially contiguous locations.

The second major point, pertaining to the level of the ‘types of dependence’, is as follows. There is a subtle but significant shift between the items enumerated by Athena to Telemachus and those enumerated by Circe to Odysseus. In the first case, we found a series of place names – ‘Pylos’, ‘Sparta’ – marked out as entries by the lexical tags ἐς or -δε. In the hodos to Hades a similar tag, ἔνθα, designates ‘entries’ in the catalogue, too. This is quite important, given that toponyms seem hard to come by in the Underworld. In this wilderness bereft of proper names, some other means of designating a place must be found: a rock, a confluence of rivers, a grove.

Somewhere between the thickly wooded shore and Persephone’s grove (and the tall poplars, and the fruit-perishing willows), between the rock and Pyriphlegethon and Cocytus, we find ourselves edging away from narrative discourse towards descriptive discourse. This is not only because of the highly conspicuous substitution of the sequence of temporal adverbs πρῶτα, κεῖθεν, ἔπειτα by the tripartite anaphora of the primarily spatial adverb ἔνθα at lines 509, 513, 515;Footnote 71 the passage is equally rich with verbs in the omnitemporal present (ῥέουσιν, 513; ἐστιν, 514; along with unexpressed existential predicates at 509–10 and 515).

The second entry in Circe’s hodos-catalogue thus blossoms into a discursive mode fully marked by ‘high descriptivity’ characteristics. We find a series of pieces of information about what the story-world is like, a set of attributions that constitute subtheme-like items in relation to themes (theme ‘Cocytus’, subtheme ‘which is an off-break from the water of the Styx’), a listing of states of affairs that is the stock in trade of description and all the grammatical features that attend this function discussed above.

To recapitulate: even without any express signalling of the temporal dimension ordering the items sequenced by a hodos, the discursive mode governed by this hodos is still marked by a kind of narrativity thanks to the inherent significance of the temporal sequence of the events it encompasses. Second, it is not only this temporal dimension that defines the order in which the hodos sequences its items: the inherent geography and topology of the spatial items it enumerates plays a fundamental role in dictating the set of possible combinations that form the series of the ordered sequence of the hodos. Third, at the level of ‘types of dependence’, the ‘entry’ component of the catalogic framework creates a regular (in the sense of both ‘orderly’ and ‘repeated’) opportunity for interludes of descriptive discourse that present states of affairs, introduce objects and places and attribute qualities to them, and are marked by the linguistic features characteristic of description (spatial adverbs and verbs in the omnitemporal present, perfect, etc.).

3.2.4 Types of Dependence: Narrative Episodes Tied to Places

One final point must be addressed before moving to the more consequential of Circe’s two hodoi. Continuing with the passage above, we find (Od. 10.513–20):

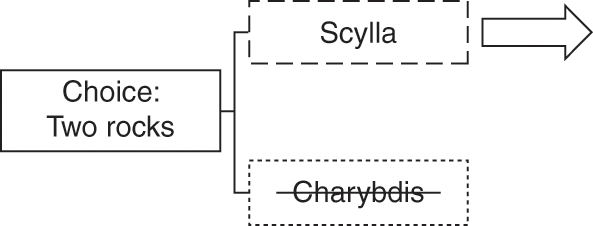

While it is interesting to note how the ‘tag’ ἔνθα is used at line 515 to make the pivot from description-oriented discourse to narratively oriented discourse, the temporal adverb (μετέπειτα) and ordinal language (πρῶτα, τὸ τρίτον) clearly indicate the inherent significance of the ordering of events that is the hallmark of high-narrativity discourse. As we shall discuss at much greater length in the next chapter, the imperative mood here expresses the sequence of actions that constitute the narrative; this highly narrative level nested within a highly descriptive one, which is itself nested in the narratively sequenced catalogue of the hodos, often takes this verbal form in the Odyssey.Footnote 72 Furthermore, as the use of the imperative mood (in dashed underline), the use of the vocative, and the second person markers suggests, this level of discourse is used to convey instructions specifically pegged to the places that make up the catalogue entry and are described in the ensuing description section: we may therefore be more specific and call this level of dependence: ‘instruction’ (see Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2 The figure of the hodos in Odyssey 10

3.3 Conclusions

The apparatus developed in the first section of this chapter (3.1) provided us with a toolkit to analyse key portions of the Odyssey where the figure of the hodos plays a key role in dictating the discursive architecture of a portion of the poem. As a form of catalogic discourse, the rhetorical schema of the hodos orders the entries that form it according to a distinctive sequence. The parameters governing the order of this sequence include both a spatial and a temporal dimension. Because the items that form entries in a hodos-catalogue are places (Section 3.2.2a), the spatial configuration of the places to be catalogued dictates the possible sequence in which they can be arranged on the basis of their geographical contiguity (Section 3.2.2b); on the other hand, in the hodoi we have seen enumerated in Odyssey 1 and Odyssey 10, the fundamentally narrative dimension of the human movement from place to place imparts a clear temporal order to the sequence of places catalogued; it configures what we have termed spatio-temporal con-sequence from spatial contiguity (Section 3.2.2c). This narrativity also gave the catalogue produced by the rhetorical schema of the hodos the quality of a series: the order of the places matters.

The example of the hodos through the Underworld enumerated by Circe in Odyssey 10 also reveals key features of a possible type of dependence governed by the rhetorical schema of the hodos. As we have seen, much as in the A-B-C pattern scholars have discerned in the Catalogue of Ships, the narrative frame of the catalogue provides an opportunity for portions of description to depend from each entry (3.2.3), and for portions of narrativity (in this case, instructions) to further depend from these descriptions (3.2.4).

With this basic structure of the rhetorical schema of the hodos and the types of dependence it can dictate in mind, it is now time to examine the second hodos that Circe spells out for Odysseus: the itinerary in Odyssey 12 that runs from her island of Aeaea and goes to Thrinacia, where the Sun pastures his cattle.

4.1 Odyssey 12: Rhetorical Schema of the hodos

4.1.1 Rhetorical Schema of the hodos

What does the analysis set out in the previous chapter mean for Circe’s second hodos, the one she details in Odyssey 12? The overarching task of this chapter will be to analyse Od. 12.39–141 using the tools introduced and the framework developed in the Chapter 3.

The dramatic scenario in which Circe spells out this hodos is well-known. Odysseus has returned from the Underworld to attend to the bones of the hapless Elpenor. But he is also, from a narrative perspective, still empty-handed; Tiresias has not in fact provided the directions home that Odysseus needs, and it therefore falls to Circe to designate the actual itinerary of his journey home.Footnote 1 She greets the returning voyagers with characteristic hospitality, and then, dispatching the ship’s crew, pledges to Odysseus: ‘I shall indicate the hodos and sign out each [of the road-marks]’ (αὐτὰρ ἐγὼ δείξω ὁδὸν ἠδὲ ἕκαστα σημανέω, Od. 12.25–26).Footnote 2 With a minimum of preliminaries, she then launches into the business of doing just this.

In fact, in the catalogic discourse that follows (Od. 12.27–141), we find precisely what our study of the hodos enumerated by Athena to Telemachus in Odyssey 1 would lead us to expect. There, we saw that: (a) the temporal adverbs and particle combinations πρῶτα μὲν … κεῖθεν δὲ … δὴ ἔπειτα enumerated entries in the catalogue of the hodos-itinerary; (b) the sequence of this discursive enumeration tracked the underlying movement in the story-world from destination to destination to be undertaken in the future by Telemachus; (c) the destinations themselves were marked by the lexical items -δε and εἰς; and (d) the events that made up the core of the narrative were expressed in verbs in the aorist, often in the imperative mood (and in the second person). What we find in Odyssey 12 is fundamentally the same constellation of features, though with a few small modifications; for example, the second person imperatives have been replaced by second person futures. Circe begins (Od. 12.39):

And introduces the Cattle of the Sun (Od. 12.127):

Between these moments, a section introduced by the following lines intervenes immediately after the Sirens episode ends (Od. 12.55–58):

Here, too, the textual progression along temporal lines is marked through the cluster αὐτὰρ ἐπὴν δή. The sequence of the textual progression and the sequence of places to be visited in the voyage are correlated with the story-world that Circe narrates to Odysseus: the ‘what place comes next on the hodos’ (ἔνθα) is coordinated with the ‘what comes next in the narration’ (ἔπειτα διηνεκέως ἀγορεύσω).

This is as we would expect from the rhetorical schema governed by the figure of the hodos. We will in due course be able to examine the portion where Circe presents the choice. First, however, and by way of clarifying the patterns that define the other two discursive units (which will then give us a framework for examining the portion where the choice can be found), we will move to the level of types of dependence to examine how the discursive units marked out by this constellation of adverb and particle clusters, tense-aspect-mood-person configurations, and the relationship between narrated movement through space and discursive patterning are organized internally: that is, at the level of dependence.

4.1.2 Levels of Dependence

4.1.2.1 The Sirens and Thrinacia

As expected, a brief narrative link (Od. 12.39a, 12.127a) connecting catalogue entries creates a frame from which first description (Od. 12.39b–46, 127b–36), then further narration (in the form of instruction – Od. 12.47–54, 137–41) depend (see Table 4.1). It is these relations we will now examine at further length.

The first and last of these discourse-units are as follows (Od. 12.39–54, 127–41):

Table 4.1 Preliminary division of Od. 12.39–141 by discourse-unitsFootnote 3

| Sirens | Choice: Two Roads (and Two Rocks) | Cattle of the Sun | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lines | 39–54 | 55–126 | 127–41 |

Σειρῆνας μὲν πρῶτον ἀφίξεαι, αἵ ῥά τε πάντας ἀνθρώπους θέλγουσιν, ὅτις σφεας εἰσαφίκηται. ὅς τις ἀιδρείῃ πελάσῃ καὶ φθόγγον ἀκούσῃ Σειρήνων, τῷ δ᾽ οὔ τι γυνὴ καὶ νήπια τέκνα οἴκαδε νοστήσαντι παρίσταται οὐδὲ γάνυνται, ἀλλά τε Σειρῆνες λιγυρῇ θέλγουσιν ἀοιδῇ ἥμεναι ἐν λειμῶνι, πολὺς δ᾽ ἀμφ᾽ ὀστεόφιν θὶς ἀνδρῶν πυθομένων, περὶ δὲ ῥινοὶ μινύθουσι. ἀλλὰ παρεξελάαν, ἐπὶ δ᾽ οὔατ᾽ ἀλεῖψαι ἑταίρων κηρὸν δεψήσας μελιηδέα, μή τις ἀκούσῃ τῶν ἄλλων· ἀτὰρ αὐτὸς ἀκουέμεν αἴ κ᾽ ἐθέλῃσθα, δησάντων σ᾽ ἐν νηὶ θοῇ χεῖράς τε πόδας τε ὀρθὸν ἐν ἱστοπέδῃ, ἐκ δ᾽ αὐτοῦ πείρατ᾽ ἀνήφθω, ὄφρα κε τερπόμενος ὄπ᾽ ἀκούσῃς Σειρήνοιιν. εἰ δέ κε λίσσηαι ἑτάρους λῦσαί τε κελεύῃς, οἱ δέ σ᾽ ἔτι πλεόνεσσι τότ᾽ ἐν δεσμοῖσι διδέντων. |

Θρινακίην δ᾽ ἐς νῆσον ἀφίξεαι· ἔνθα δὲ πολλαὶ βόσκοντ᾽ Ἠελίοιο βόες καὶ ἴφια μῆλα, ἑπτὰ βοῶν ἀγέλαι, τόσα δ᾽ οἰῶν πώεα καλά, πεντήκοντα δ᾽ ἕκαστα. γόνος δ᾽ οὐ γίγνεται αὐτῶν, οὐδέ ποτε φθινύθουσι. θεαὶ δ᾽ ἐπιποιμένες εἰσίν, νύμφαι ἐυπλόκαμοι, Φαέθουσά τε Λαμπετίη τε, ἃς τέκεν Ἠελίῳ Ὑπερίονι δῖα Νέαιρα. τὰς μὲν ἄρα θρέψασα τεκοῦσά τε πότνια μήτηρ Θρινακίην ἐς νῆσον ἀπῴκισε τηλόθι ναίειν, μῆλα φυλασσέμεναι πατρώια καὶ ἕλικας βοῦς. τὰς εἰ μέν κ᾽ ἀσινέας ἐάᾳς νόστου τε μέδηαι, ἦ τ᾽ ἂν ἔτ᾽ εἰς Ἰθάκην κακά περ πάσχοντες ἵκοισθε· εἰ δέ κε σίνηαι, τότε τοι τεκμαίρομ᾽ ὄλεθρον, νηί τε καὶ ἑτάροις· αὐτὸς δ᾽ εἴ πέρ κεν ἀλύξῃς, ὀψὲ κακῶς νεῖαι, ὀλέσας ἄπο πάντας ἑταίρους. |

|

First you will reach the Sirens, who charm all Men, whoever happens to approach them. And whosoever draws near to them in ignorance and hears the voice Of the Sirens, neither this man’s wife nor his little children Will be at hand, delighted, as he returns home; But the Sirens, enchanting him with their clear song, Wait in their meadow, and there is a great heap of men Rotting on their bonesFootnote 4 as the skin withers around them. But give a wide berth as you sail past, and anoint the ears of your crewmates With beeswax kneaded soft, in order that none Of them hear the singing. But should you yourself wish to hear it, Let them bind you hand and foot upright on the mast Of the swift ship, the ropes made fast to the beam, So that you may delight in hearing the voice of the Sirens. And if you plead with your men, command them to untie you, Let them bind you yet tighter still. |

Then you will reach the island Thrinacia: and there the many Cattle and sleek sheep of Helios pasture. Seven herds of oxen, and as many fine flocks of sheep, With fifty creatures in each herd. There is no begetting among them, Nor do they ever perish. Their shepherds are goddesses, Nymphs with beautiful braids, Phaëthousa and Lampetie, Whom heavenly Neaera bore to Helios Hyperion. Having given birth to them and raised them, their lordly mother Sent them to the island Thrinacia to dwell far away And guard their father’s sheep and cattle with curved horns. If you leave the cattle unharmed and keep your nostos in mind, You may all yet make it to Ithaca, despite suffering ills. But if you harm them, in that case I foresee destruction For ship and crew; and even if you yourself survive, You will return late and in bad condition, having destroyed all your companions. |

As expected, textual features characteristic of description are on abundant display in Od. 12.39b–46 and 127b–36: verbs are in the timeless/omnitemporal present indicative and in the third person (θέλγουσιν at 40 and 44, μινύθουσι at 46, βόσκοντο at 128, γίγνεται at 130, φθινύθουσι and εἰσίν at 131) or (stative) perfect (ἥμεναι at 45); the spatial adverb ἔνθα opens the descriptive portion at Od. 12.127; motion through the story-world (i.e. the future motion through it that Circe foretells) ‘stops’; the ‘statics of the world’ – states of affairs and enduring properties – are presented, and qualities and properties attributed to objects and places.

Similarly, in lines 12.47–54 and 12.137–41, we find again what we would expect to find at this level of dependence; just as in Odyssey 10, Circe follows descriptions of the places that form the hodos with instructions about what to do there. Accordingly, we find several verbs in the imperative or (especially where conditional clauses are concerned) in the subjunctive or optative; similarly, these instruction sections feature verbs in the second person, rather than the third person of description sections.

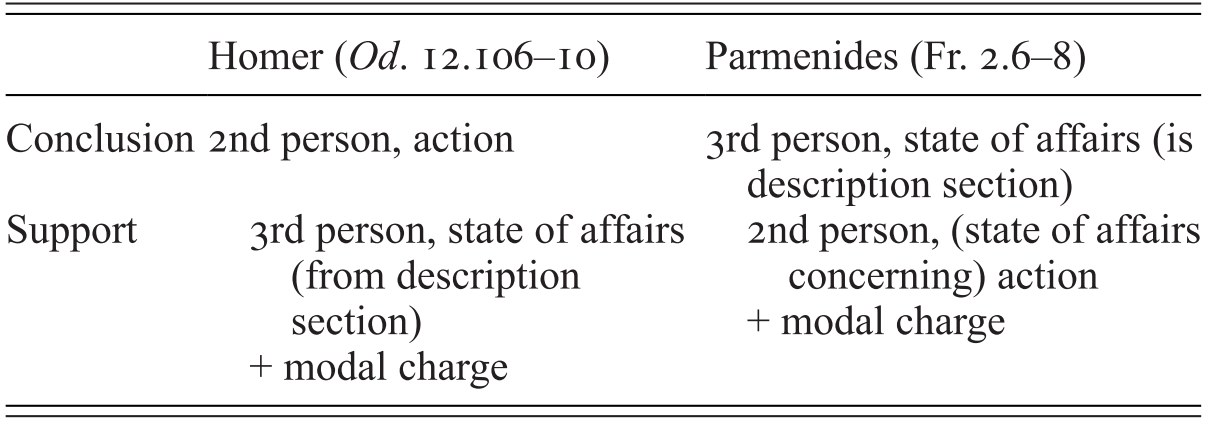

In order to analyse these sections better, it will be useful to proceed by way of a very brief detour through scholarship concerning Homeric deliberation. In a major study of this and related topics, Christopher Gill highlights three features that are characteristic of Homeric deliberation.Footnote 5 First, Homeric deliberation often involves ‘working out the implications of different courses of action’.Footnote 6 Second, this working out of implications involves a process by which an actor ‘first entertains and then rejects a certain course of action; and the rejection is a crucial preliminary to the reaching of a conclusion’.Footnote 7 Third, these courses of action are often ‘evaluate[d] … in light of explicit or implied goals’ or in relation to a general rule;Footnote 8 so the thought pattern often adheres to the following form: ‘if I do x, then y will happen, and this involves z, which is bad or good.’Footnote 9 Rachel Knudsen has identified two further features of Homeric deliberation: first, the conclusion of a chain of inferences often takes the form of an imperative or some other kind of instruction (something concerning actions, that is, rather than states of affairs); and, second, these conclusions often come first and are linked to the supporting premises, which come after, by gar or epei.Footnote 10

Returning to the Sirens, two points may be established. First, that Circe does not merely provide a set of detailed instructions for Odysseus (in the form of the imperatives); instead, she persistently justifies them by embedding them in a purposive or explanatory framework. The means by which she does so are grammatical: the purpose clause and the conditional construction.Footnote 11 Thus Circe’s imperative: οὔατ᾽ ἀλεῖψαι ἑταίρων (Od. 12.47) is not expressed as some kind of divine injunction imposed from above; rather, she supplies a rationale in the form of the negative purpose clause: μή τις ἀκούσῃ | τῶν ἄλλων (Od. 12.48–49). As Knudsen suggests, it is the conclusion, expressed in the form of an imperative to an action, which comes first; as Gill leads us to expect, it is by virtue of thinking through (a) the implications of a course of action (b) in reference to a particular goal or end that each imperative is justified. So, too, her final instructions for Odysseus’ encounter with the Sirens – οἱ δέ σ᾽ ἔτι πλεόνεσσι τότ᾽ ἐν δεσμοῖσι διδέντων (Od. 12.54) – forms the apodosis of a conditional clause: if you plead with your companions to release you, then let them bind you tighter still. In the first instance, Circe establishes the explanatory relationship between her instructions and the rationale behind them in the form of a purpose clause: her instructions (anointing the ears of Odysseus’ crew) represent a good way to achieve a particular outcome (preventing them from hearing the Sirens’ song and, ultimately, being seduced by it). In the second, she uses a conditional clause to articulate something akin to a causal relationship: an effect to be triggered in the event that a given condition is met. We even see a chain of explanatory argument evolve in the linkage between the two (12.49–52): Circe locates her instruction in the apodosis of a conditional clause, and this apodosis triggers its own purpose clause – if what you want is to hear the Sirens, have your men bind you to the mast in order to hear the song of the Sirens and take delight in it (without being fatally waylaid by their seductive song).

The second point is that if it seems natural, even obvious, that Circe should account for her instructions to Odysseus, the first hodos she details (in Odyssey 10) suggests otherwise. There she outlines a series of places Odysseus will need to pass through en route to Hades, giving a detailed series of instructions about what to do when he has arrived at the rock where Acheron receives its tributaries. Those instructions, however, are simply instructions (Od. 10.516–25):

Indicators, syntactical or semantic, articulating explanatory, purposive, or intentional relationships justifying these instructions are completely absent: Odysseus is simply supposed to do the things she tells him to do. The contrast between these two ‘instruction’ segments depending from the ‘description’ sections (the first bare instructions, the second embedded within a framework of inferential justification) suggests we might do well to call this section not only ‘instruction’ (as does de Jong), but even ‘justified instruction’ – or even, according to the terminology set out in Section 3.1.2, ‘argument’.

The Thrinacia episode develops this penchant for examination and explanation. Recall Gill’s observation that in Homeric deliberation, the deliberating character often ‘entertains and then rejects a certain course of action; and the rejection is a crucial preliminary to the reaching of a conclusion’.Footnote 12 Common to Od. 12.47–54 and 12.137–41 is the use of conditional clauses, though the differences between them in the Sirens episode and those related to Thrinacia are striking. In the first case, the conditional sentences are geared towards attaining a certain set of outcomes – to hear the Sirens and not be destroyed by doing so. By contrast, the three conditional clauses in the Thrinacia episode examine the terms and consequences of a single choice. Two mutually exclusive possibilities are presented: either Odysseus and his men can leave the cattle unharmed, or they can harm the cattle – plainly they cannot both harm and not harm the same cattle (the point is driven home by the binary pair ἀσινέας/σίνηαι, 12.137, 139).Footnote 13 What is more, these choices are presented as exhaustive: these two options are plainly the only two conceivable options. In the first case the outcome is clear: nostos for all. Not so the second case; again deploying the framework of the conditional clause, Circe examines two possible consequences resulting from the second course of action. That Odysseus’ men will perish and his ship will be destroyed is expressed unequivocally (τεκμαίρομαι),Footnote 14 but ‘even if’ (εἰ … κεν …) Odysseus happens to survive, he will be much delayed and will return in grievous circumstances (139–41). And although Circe does not explicitly reject one of the two courses of action, the way in which she establishes the implications of each strongly suggests the undesirability of one – ‘a crucial preliminary to the reaching of a conclusion’.Footnote 15

4.1.2.2 Levels of Dependence in Odyssey 12: The Relationship between ‘Description’ and ‘Instruction’/‘Argument’

We see, then, that the two ‘description’ passages fulfil two of the basic roles the study of narrative has typically assigned to description: to introduce the places, objects, characters, and so forth that are to feature in a given narrative segment,Footnote 16 and to make this world and its components vivid.Footnote 17 This pair of functions is particularly vital at this stage in the narrative, located as we are in the fantasy world of the Apologoi. Since Pylos and Sparta, Nestor and Menelaus need rather a different introduction from, say, the Sirens, the scenario is quite different from what we saw in Odyssey 1;Footnote 18 in the fantasy world of the Apologoi,Footnote 19 a world must be formed anew each time the next island-episode appears on the horizon, its story-universe invented and peopled with characters, filled with objects. The two ‘instruction’ or ‘argument’ subsets of the Siren and Thrinacia episodes, meanwhile, reveal a persistent tendency on the part of the goddess to justify or provide explanations for the instructions she offers, and an interest in examining the relationship between action and outcome, decision and consequence.

With this in mind, we may propose the following relationship between Od. 12.39b–46 and 12.47–54, and 12.127b–36 and 12.137–41, respectively. The descriptive passages each (a) introduce the setting and dramatis personae, then (b) hone in immediately on the most pertinent details, which (c) are examined through a kind of embedded narrative that directly or indirectly sets up the ‘instruction/argument’ passages that follow.Footnote 20 Particularly deft in this last respect is the failed nostos Circe presents in miniature in the Sirens episode. She does this through the syntactical resource of the indefinite general relative clause (hos tis, Od. 12.41–43), which allows her to set out one of the two key considerations to be negotiated in the following ‘instruction’: that the Sirens’ song is so seductive that it prevents passing sailors from fulfilling their nostoi and rejoining their wives and children. In the Thrinacia episode, this means introducing the cattle, adumbrating their number,Footnote 21 their extraordinary qualities (Od. 12.130–32), and the degree to which the Sun god cares about them (Od. 12.132–36).

This judicious dispensation of details laying the groundwork for narration to come might simply be thought a mark of good story-telling. Richardson writes: ‘Homer is not interested so much in the object of the description as he is in its effect on the particular scene, and he therefore feels no need to describe the setting for its own sake but only on those occasions when it matters.’Footnote 22 But this narrative strategy should not be taken for granted. As we saw in the case of Circe’s first hodos, instructions issued by the goddess, however vital, need not necessarily be preceded by much in the way of preparatory description; just because a place or object ‘matters’, that is, does not guarantee that it will be presented to the audience prior to ‘mattering’. In the episodes that bookend Circe’s second hodos, however, her instructions and the justification she provides for them are scrupulously anticipated by details introduced in the preceding descriptive sections.

If details that matter need not necessarily be introduced but are in Od. 12.39–46 and 12.127–36, Richardson’s general formulation does only partial justice to the sophisticated use to which the details that ‘matter’ are put in the instruction/argument sections of Od. 12.47–54 and 12.137–41. Details are not introduced in the first sections merely to make a brief cameo in the second before Circe moves on; rather, they are carefully placed in an intentional and purposive framework, or examined in terms of their modality and the matrix of possible consequences that can issue from them. Circe does not simply say ‘put wax in your men’s ears and have them tie you to the mast’ as she does ‘dig a pit of so many cubits, perform this ritual in this sequence, make such and such a vow’ (Od. 10.516–25). Instead, in her instructions to act a certain way, Circe explicitly addresses the question, ‘Why?’, and her discourse, teeming with purpose and conditional clauses, bears the mark of this rationalization.Footnote 23

We may summarize the type of dependence between the description and instruction/argument sections in the following way. In the episode of the Sirens and of Thrinacia, Circe’s descriptive sections serve both to create a world within which the narrative actions are located and to anchor this world in a sense of reality; they also hone in on specific elements of this world that are often of direct significance for the instructions that follow on from them; and, finally, these details serve as the evidence that provides a basis for the instructions issued, and upon which they are justified (or create a consequential framework surrounding the different stances Odysseus and his men might take in relation to them). These observations will also provide a useful starting point for an examination of the intervening passages, in which the Planctae, Scylla, and Charybdis feature.

4.2 Krisis

4.2.1 Rhetorical Schemata

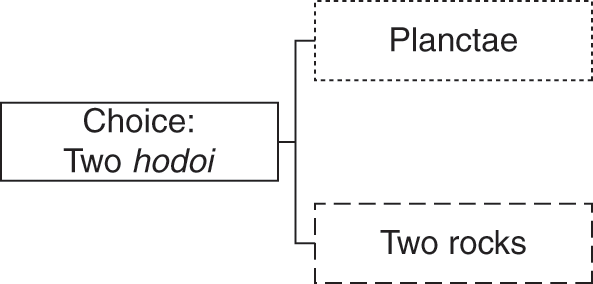

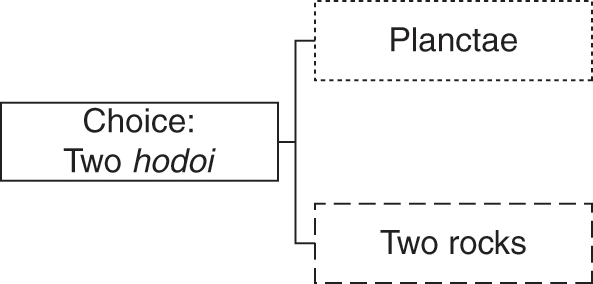

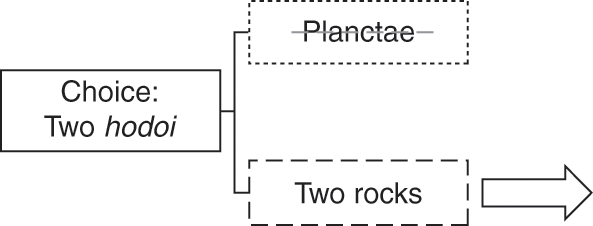

If analysing Od. 12.39–54 and 12.127–41 can be done rather neatly, how best to analyse the different units that make up Od. 12.55–126 is more challenging. De Jong’s commentary, generally a reliable starting point, is misleading or inaccurate in a number of ways when it comes to this passage. For example, lines 12.108–10 and 124–26 are inexplicably assigned to Charybdis, not Scylla; the first half of line 12.73 addresses not only Scylla, but both Scylla and Charybdis; lines 12.81b–82 are plainly not descriptive.Footnote 24 One suspects that these uncharacteristic inaccuracies stem from de Jong’s decision to use the individual characters or places – viz. the Sirens, the Planctae, Scylla, Charybdis, Thrinacia – as the base units (‘episodes’) of her analysis. While this is appropriate for the Sirens (12.39–54) and Thrinacia (12.127–41), where the segmentation of the text (that is, of the narrative or plot) corresponds to the discrete places where Odysseus will arrive, in lines 12.55–126 something else is going on.

Figure 4.1 Preliminary analysis: Discursive organization governed by the figure of the hodos in Odyssey 12

As noted, Od. 12.55–58 fits the model of ‘prior narration’, the top unit in the levels of dependence:

Two recent studies on autar and autar + epei/epeita/epēn have made clear how these clusters of what are traditionally classed as particles and conjunctions are better understood as discourse markers that help speakers organize their discourse by parcelling it into distinct units.Footnote 25 Applying their findings to this portion of the Odyssey, we may say that αὐτὰρ ἐπήν would here mark the beginning of a new narration section. Similarly, we find typical markers of narrative activity, including three verbs in the future indicative ἀγορεύσω, ἐρέω, and ἔσσεται.Footnote 26 The cluster ἔπειτα διηνεκέως also marks the progression of the text along temporal lines. All the features of narration discussed above are in play here.

By contrast, very few of these narrative elements are found in 12.59–126. Instead, we find extensive stretches of description (to be examined shortly) introduced by the portentous phrase (Od. 12.57–58):

These two hodoi, both of which she promises to enumerate, in fact introduce what amounts to 47.5 lines (12.59–106a) of description; verbs in this portion of the text overwhelmingly take the omnitemporal present, and nearly all the adverbs used are spatial (e.g. enthen at 12.59; entha at 12.85; tēi [‘past there’] at 12.62, 12.66; tōi [‘in that place’] at 12.103, 12.104). The text proceeds along largely spatial lines, with little movement in ‘story’ time (barring one important exception, which we shall note shortly).Footnote 27 The function of these portions is clearly to introduce elements of the story-world and attribute qualities and attributes to them.

One major exception is a curiously ambiguous line and a half of plainly narrative language occurring at 12.81b–82, just after the first of the ‘two rocks’ (viz. Scylla’s rock) is introduced (Od. 12.80–82):

As the commentators note, ἰθύνετε is an aorist subjunctive; when combined with the ἄν in the environment of a prophecy, this has the force of something approaching a command.Footnote 29

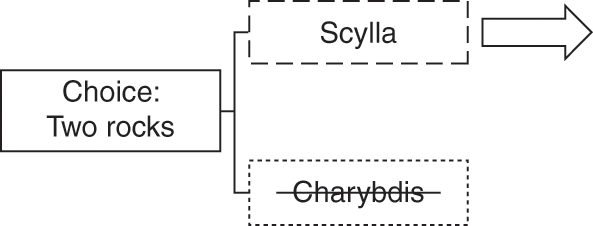

What are we to make of this? Lines 81b–82 (ᾗ … Ὀδυσσεῦ) plainly cannot be designated as descriptive (as de Jong would have it): the textual features are not those of description, neither establishing features of the narrative world nor attributing qualities to the characters that populate it. Depending on how one interprets the force of the subjunctive + an construction in the context of a prophecy, this could either be a prior narration section, which would introduce a new unit, or an instruction section, which would close off an old unit, according to the analysis we have been undertaking so far (see Figure 4.2 below). Perhaps in this setting, however, the ambiguity is useful. We might do well to see the clause that spans the two lines as doing double duty: as instruction, it closes off the section that, as we shall see, details a choice between the two ‘routes’, while as prior narration it opens a new kind of textual or discursive unit in which the two creatures, Scylla and Charybdis, are presented in high-descriptivity passages followed by instruction/argument (12.106b–10) concerning how best to address them.

A version of de Jong’s schema modified to take these points into account might look like Table 4.2. On this reading, we can identify three possible units of analysis. The first would be discursive units, units of discourse parcelled out or marked off as discrete items by discourse markers on the surface of the text (clusters of adverbs and particles, here in combination with prior narration introducing the new unit and following a section of instruction closing the old units); these would be distinctions made at the level of discourseFootnote 30 and would here be coextensive with entries in the catalogue of Circe’s hodos-itinerary (capitalized in Table 4.2). These units we may contrast with what we may still, following convention, call episodes, which would correspond to all the locations Circe mentions, regardless of whether she actually instructs Odysseus to visit them;Footnote 31 these episodes may revolve around particular characters (e.g. the Sirens) but they are ultimately tied to specific places (which number five, underlined in Table 4.2, and would include the Planctae and Charybdis (rejected by Circe)). Finally, we can identify a third category between these two, what we might call a ‘hodos-unit’, which marks out a distinct node in the itinerary (based on the analysis of the level of dependence undertaken so far) that makes up the hodos enumerated in the catalogic discourse of Circe’s prophecy. This level may be seen to bridge the underlying story-world and the level of discourse by capturing the way elements in the story-world are organized by discourse (these number four, in boldface in Table 4.2).

Table 4.2 Preliminary analysis of Od. 12.39–141

| Unit | Discourse mode | Lines |

|---|---|---|

| SIRENS | Prior Narration (PN) | 39a (‘you will first come to’) |

| Description | 39b–46 (epic te in 39 and 44) | |

| Argument | 47–54 (imperatival infinitives in 47, bis) | |

| CHOICE | PN | 55–57a (‘I cannot tell you what your way will be’) |

| Choice 1 | Instruction | 57b–58 (imperatival infinitive in 58) |

| Planctae | Description | 59–72 (epic te in 62, 64) |

| Two Rocks | Description | 73a |

| Scylla | Description | 73b–81a |

| Choice 2/Scylla | Instruction(/PN) | 81b–82 |

| Scylla | Description | 83–100 |

| Charybdis | PN | 101 (‘you will see’) |

| Description | 101–06a | |

| Two Rocks | Argument | 106b–110 |

| (Scylla 2) | Description | 118–20 (epic te in 90, 93, 99) |

| Argument/PN | 121–26 | |

| THRINACIA | PN | 127a (‘you will come to’) |

| Description | 127b–136 | |

| Argument + PN | 137–41 (‘if you do A, then you might/will …’) |

All caps = discourse-unit; bold = hodos-unit; underlined = episode.

It is this level of analysis, the hodos-unit (see Table 4.3), that will provide the basis for the following discussion; breaking things down in this fashion allows us to glean a better insight into the two passages where choices are presented (12.57–82; 81–110, 115–26) and, by helping us better discern the shape of Circe’s hodos, help us better analyse the discursive dynamics through which it is expressed. How, then, does this work in practice?

As we have seen, Circe disclaims the ability to instruct Odysseus, telling him she will present two options between which he must choose (12.57–58):

The first of these two (and both ὁπποτέρη and ἀμφοτέρωθεν underscore the duality of the choice) is presented by lines beginning ἔνθεν μὲν γὰρFootnote 32 πέτραι ἐπηρεφέες (‘There on the one hand [are] steep rocks’, 12.59). Notable is the spatial preposition enthen and the particle men, which open the door to an extended description of these steep rocks (12.59–72). The men is matched by the corresponding οἱ δὲ δύω σκόπελοι (‘And on the other [are] the two rocks’, 12.73), which in turn heads another portion of description (12.73–81a) where the first of these rocks is presented.

Scrupulous symmetries characterize the two items presented in the harmonized balance of the men … de … clauses, as Hopman puts it:

Circe’s prophecy clearly constructs the Planctae and the straits of Scylla and Charybdis as parallel dangers. Both involve a narrow path located between cliffs made of smooth stone (petrai, 12.59, lis petrē, 12.64 [Planctae]; petrē … lis, 12.79 [Scylla]). Amphitrite, who otherwise appears only twice in the Odyssey (3.91 and 5.422), is mentioned in relation to both the Planctae and Scylla (12.60 and 97). Finally … a similar ‘description by negation technique’ is used to describe both hazards. Just as no dove would be able to go through the Planctae, not even a great archer could reach Scylla’s cave with his arrows (12.62–4 and 12.83–84) … in Circe’s speech, therefore, the Planctae are structurally and thematically comparable to the Straits of Scylla and Charybdis.Footnote 33

In Bakker’s view, as a general matter in Homer, the use of men ensures that the option introduced by the de clause is ‘framed’ in relation to the option in the men clause.Footnote 34 This ‘framing’ need not set up an antithetical relationship: ‘[a] speaker using men, looking forward to an upcoming statement with de, does not so much presuppose a common basis for conducting discourse as establish one’.Footnote 35

Whereas units of discourse are mapped onto places one-to-one in the Sirens and Thrinacia episodes, in the course of the hodos-unit formed by the narration-description-instruction section spanning lines 12.57–82 we find two different geographic units, the Planctae and the Two Rocks. They are not introduced at the level of the narrative frame (the top level of dependence), but rather form two different entries placed in parallel at the second level of dependence, that of description.

Precisely the same dynamics are to be found in the course of lines Od. 12.73–106a, which relate Scylla and Charybdis to each other and describe them. The two are presented through a men … de … framing device (for Scylla’s rock: ὁ μὲν οὐρανὸν εὐρὺν ἱκάνει | ὀξείῃ κορυφῇ at 12.73–74; for Charybdis: τὸν δ᾽ ἕτερον σκόπελον χθαμαλώτερον at 12.101)Footnote 36 at the level of description rather than narration.Footnote 37 What follows (Od. 12.73b–81a, 12.83–106a) is an extended description addressing the first option and then the second, the details of which are closely coordinated.Footnote 38 There is also one final point: an advantage of this line of analysis is that the hodos-units do not map one-to-one onto ‘episodes’; as the confusion surrounding lines 73–81a make clear, it is entirely possible for one discrete place or character – Scylla and her rock, in this case – to be split across two different hodos-units in a way that analysing by episode does not allow for.

By way of linking the foregoing discussion to existing scholarship on ancient Greek thought, and also to pinpointing what makes this portion of the Odyssey distinctive, it is helpful to discuss these points in light of the Homeric phenomenon that Geoffrey Lloyd termed ‘polar expressions’, with which the relationship between the Planctae and the Two Rocks, and between Scylla and Charybdis, may seem to have much in common.Footnote 39 As Lloyd emphasizes, however, the unit that forms one half of a ‘polar expression’ can also often be paired with other units to form a ‘polar expression’ along a different axis; so, for example, ‘openly’ can be contrasted with either ‘secretly’ (ἢ ἀμφαδὸν ἦε κρυφηδόν, Od. 14.330) or ‘by trickery’ (ἠὲ δόλῳ ἢ ἀμφαδόν, Od. 1.296).Footnote 40 Furthermore, these polar opposites often admit of a third, intermediate option (or even a gradation of intermediate options): so soldiers need not be only either brave or cowardly, but can also be somewhere in between (μεσήεις, Il. 12.269).Footnote 41 By contrast, however, and very importantly, neither hodos of the two paired by Circe admit of another contrary to be substituted, as with ‘openly/hidden’ and ‘openly/secretly’. No ‘third hodos’ is presented – nor does the possibility seem conceivable, unless one can rewrite the geography of the story-world. It is not only that one cannot travel both routes at the same time; it is also simply that, as presented, there do not exist any other possible routes if one wants to get from the Sirens’ Meadow to Thrinacia. That the two hodoi are part of the physical space of the story-world is central not only to their mutual exclusiveness but also, that is, to the exhaustive nature of the dichotomy they form; as a convenient shorthand, we may also refer to this phenomenon of the exclusive exhaustive disjunction (where one cannot choose both options, or neither, but must choose one) between the two paths of a forked road as a krisis. The krisis will be a feature of enormous importance in Parmenides’ poem.

With this analysis in hand, we can now identify a second kind of operation in the syntax of the hodos as a form of catalogic discourse. The focus has been on the ordered sequentiality according to which items form entries in the series of the catalogic discourse organized by the figure of the hodos (see Table 4.4a, b, c). In the exclusive disjunction or krisis, we see a second possible relationship that can obtain between two items of a hodos-itinerary within one unit of hodos-discourse, one that relates these two items in the story-world at the level of description, not narration.

Table 4.4a Organization by (possible) episodes (after de Jong)

| Sirens | Planctae | Scylla | Charybdis | Thrinacia | ? | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prior Narration | 39a | – | – | 101 | 127a | 55–57a, 81b–82? |

| Description | 39b–46 | 59–72 | 73b–81a, 83–100, 118–20 | 101–106a | 127b–136 | 73a |

| Instruction/Argument | 47–54 | – | – | 106b–110, 121–26 | 137–41 | 57b–58?, 81b–82? |

Table 4.4b Organization by discourse-units/episodes visited

| SIRENS CHOICE | THR. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Two Roads) | Planct. | Two Rocks | (Two Rocks) | Scylla | Charyb. | |||

| PN | 39a | 55–57a | – | – | 81b–82 | – | 101 | 127a |

| Desc. | 39b–46 | – | 59–72 | 73a (both), 73b–100 (first rock) | – | (73b–81a), 83–100, 118–20 | 101–106a | 127b–136 |

| Inst. | 47–54 | 57b–58, 81b–82 | – | – | 106b–110, 121–26 | – | – | 137–41 |

All caps = discourse-unit; bold = hodos-unit; underlined = place visited; strike through = place not visited.

Table 4.4c Organization by hodos-units

| Sirens | Two Roads | (Planct.) | (Two Rocks) | Two Rocks | (Scylla) | (Ch.) | Thrin. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PN | 39a | 55–57a | – | – | 81b–82 | – | 101 | 127a |

| Desc. | 39b–46 | – | 59–72 | 73a (both), 73b–100 (first rock) | – | (73b–81a), 83–100, 118–20 | 101–106a | 127b–136 |

| Inst. | 47–54 | 57b–58, 81b–82 | – | – | 106b–110, 121–26 | – | – | 137–41 |

4.2.2 Types of Dependence: Description and Argument in the krisis Section

This has implications at the level of types of dependence for sections of text that depend from the entries that make up the catalogue of the hodos. Compared to Od. 12.39–54 and 12.127–41, however, the dynamics of lines Od. 12.55–126 are subtly but critically distinct. Since in lines 12.55–126 it is the places themselves – as opposed to actions (e.g. to kill or not to kill the Cattle of the Sun) – that form the possible choices in question, in the scenario of the krisis it is the nature of the places themselves (as opposed to the actions one can or cannot perform there) that now commands the narrator’s attention. The places themselves must be adequately described in order that a choice between them may be made. As a result, in lines Od. 59–126, description predominates to a far greater extent than in other sections: in the Sirens episode the portions are virtually even (7.5 lines of description to 8 lines of argument), while in the Thrinacia episode we find a description to argument ratio of nearly 2:1 (9.5 lines to 5) – between lines 12.59 and 126, however, the ratio stands at nearly 6:1 (52 lines of description to 9 of instruction/argument).Footnote 42

This is significant, especially given the view that oral poetry is good at, and its linguistic resources designed for, ‘describ[ing] the acts of persons and the happening of events’, but offers few means of examining the world beyond ‘verbs of doing and acting and happening’.Footnote 43 On this view, even when the language of oral poetry is mobilized to gain purchase on ‘the nature of the outside world’, its orientation towards the expression of actions and events inclines it strongly towards doing so ‘in diachronic terms, as history rather than as philosophy or science’.Footnote 44