The assembly’s very existence would also help promote the peaceful resolution of international conflicts. Because elected delegates would represent individuals and society instead of states, they would not have to vote along national lines. Coalitions would likely form on other bases, such as world-view, political orientation, and interests. Compromises among such competing but nonmilitarized coalitions might eventually undermine reliance on the current war system, in which international decisions are still made by heavily armed nations that are poised to destroy one another. In due course, international relations might more closely resemble policymaking within the most democratic societies in the world.Footnote 1

The United Nations is not a world government, but it is our primary forum to discuss issues and risks of global significance in an increasingly interdependent world. Whether it is perceived as being imbued with a strong dose of democratic legitimacy matters a great deal for its effectiveness, credibility, and ability to become a problem-solving organization. For all of these reasons, and for those expressed below, we suggest the establishment of a significantly reformed General Assembly as explained in Chapter 4. Until such significant reforms are realized, in this chapter we also sketch out the possibility of an interim “World Parliamentary Assembly” that could serve as an advisory body to the General Assembly, acting as a type of “second chamber,” and greatly enhancing the legitimacy of the UN as a global decision-maker as soon as possible.

This is particularly important because the United Nations General Assembly itself on a number of occasions has expressed its unambiguous support for democratic forms of governance for its members. For instance, General Assembly Resolution 44/146 (1989) on

Enhancing the effectiveness of the principle of periodic and genuine elections [stressed] its conviction that periodic and genuine elections are a necessary and indispensable element of sustained efforts to protect the rights and interests of the governed and that, as a matter of practical experience, the right of everyone to take part in the government of his or her country is a crucial factor in the effective enjoyment by all of a wide range of other human rights and fundamental freedoms, embracing political, economic, social and cultural rights.Footnote 2

And General Assembly Resolution 55/2 (2000), one of the more substantive resolutions issued in recent decades, also known as the United Nations Millennium Declaration, states: “We consider certain fundamental values to be essential to international relations in the twenty-first century.” These include: freedom, equality, solidarity, tolerance, respect for nature, and that “democratic and participatory governance based on the will of the people best assures these rights.”Footnote 3 Clearly the United Nations voice in these important matters would carry considerably more weight if it were seen itself as being imbued by adequate levels of democratic legitimacy.

The idea of establishing a second chamber at the United Nations has existed since the organization’s inception. Grenville Clark and Louis Sohn wrestled with the issue as they worked on World Peace through World Law in the 1950s. While not actually recommending the creation of a bicameral UN, they stated: “We hold no dogmatic views on this difficult subject, the essential point being that there must be some radical, yet equitable, change in the present system of representation in the General Assembly as a basis for conferring upon the Assembly certain essential, although carefully limited, powers of legislation which it does not now possess.”Footnote 4 The idea is certainly older than the UN; the founders of the League of Nations for a time considered adding a people’s assembly as part of the League’s initial organizational structure.

One key motivation was to enhance the democratic character of the UN by establishing a firmer linkage between the organization and the peoples it was meant to serve. The preamble to the UN Charter starts with “We the peoples” and highlights our determination to “save succeeding generations from the scourge of war” and to achieve other noble ends. But, in time, the General Assembly, which comes closest among the UN’s existing agencies to representing the will of the people, falls far short of this. The men and women who serve on the General Assembly are diplomats representing the executive branches of their respective governments and there is generally no meaningful, direct linkage between them and the people they are supposed to represent. In fact, in many countries, there is no linkage between the governments themselves and the people they rule over because they are not working democracies. In his open letter to the General Assembly of October 1947 Albert Einstein stated:

the method of representation at the United Nations should be considerably modified. The present method of selection by government appointment does not leave any real freedom to the appointee. Furthermore, selection by governments cannot give the peoples of the world the feeling of being fairly and proportionately represented. The moral authority of the United Nations would be considerably enhanced if the delegates were elected directly by the people. Were they responsible to an electorate, they would have much more freedom to follow their consciences. Thus we could hope for more statesmen and fewer diplomats.Footnote 5

In time, rather than bring a measure of democratic legitimacy to the General Assembly by providing for the direct election of its members – an innovation that would require amendments to the UN Charter, as outlined in Chapter 4 – proposals emerged that put forward the creation of a second chamber, a World Parliamentary Assembly (WPA), complementary to the General Assembly, which would continue to be the main locus of government-to-government interactions. The WPA would help bridge the democratic legitimacy gap that arises when an organization, through its actions (e.g., the drafting of Conventions, decisions to intervene or not on behalf of the international community in various conflicts, the actions of its various specialized agencies and related organizations) can affect in tangible ways people’s welfare, but those affected by these decisions have little input in how they are formulated, arrived at, and implemented, thereby creating a disconnection between citizens and the United Nations.

In Chapter 4 on the General Assembly we argued in favor of giving the General Assembly greater powers to legislate in a narrow set of areas, to empower it to actually begin to deliver on the main aspirations embedded in the UN Charter. We think that this idea would gain greater acceptance and better outcomes would be ensured if the UN moved, as quickly as possible, to establish interim mechanisms that also represent peoples more directly, not just governments and/or states. Governments’ main interest at the UN to date, by and large (either consciously or through the power of inertia), is the preservation of a system overly reliant on a too-narrow conception of the sovereign state. With the possible exception of the member states of the European Union, they are mainly motivated by the belief that “a nation-state cannot be subjected to, or made accountable for the decisions of any authority beyond itself.”Footnote 6 This may have been a convenient ideological foundation for the UN for the major powers in 1945 but it has increasingly turned into an absurdity – close to 200 sovereign states operating in an interdependent world increasingly in need of a global rule of law, but bound by a chaotic patchwork of different, at times contradictory, sets of rules.

Representing the interests of the global citizenry, a new WPA, advising the current UN General Assembly, could bring in a fresh global perspective on the broad array of unresolved problems that we currently confront. It would be in a stronger position to promote higher levels of international cooperation because its members would be called upon to see such problems through the lens of humanity’s better interests rather than narrow national considerations. The WPA also could be a much more effective catalyst for advancing the process of reform and transformation at the United Nations itself because, as we shall explain below, its members would have a much looser linkage with their respective governments and their specific national – as opposed to global – priorities. In the 2010 version of his original paper making the case for the establishment of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, Heinrich notes that such a body could also play a role in reinforcing democratic tendencies in many corners of the world and foster “a new planetarian ethos by symbolizing the idea of the world as one community.”Footnote 7

Setting up a World Parliamentary Assembly

Article 22 of the UN Charter states: “The General Assembly may establish such subsidiary organs as it deems necessary for the performance of its functions.”Footnote 8 It is likely that the creation of a WPA would be seen in the spirit of the “important questions” identified in Article 18 of the Charter, which require a two-thirds majority of those members present and voting for approval, but would not require the approval of the permanent members of the Security Council. So, building public and governmental support for a General Assembly resolution putting in motion the establishment of a WPA would be the first step in what would likely be a multi-stakeholder process, involving wide consultations. However, this process will not start from zero. The creation of a WPA has already received strong endorsements from a number of major organizations and bodies. In 1993 the Canadian House of Commons Standing Committee on External Affairs and International Trade recommended that “Canada support the development of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly.”Footnote 9 In 2005, with the support of the Committee for a Democratic UN – now known as Democracy without Borders – 108 Swiss Parliamentarians sent an open letter to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan calling for the establishment of a WPA.Footnote 10 That same year the Congress of the Liberal International followed suit by calling “on the member states of the United Nations to enter into deliberations on the establishment of a Parliamentary Assembly at the United Nations.”Footnote 11

Also in June 2005 (and again in July 2018) the European Parliament issued a resolution that called for “the establishment of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly (UNPA) within the UN system, which would increase the democratic profile and internal democratic process of the organisation and allow world civil society to be directly associated in the decision-making process,” also stating that “the Parliamentary Assembly should be vested with genuine rights of information, participation and control, and should be able to adopt recommendations directed at the UN General Assembly.”Footnote 12 These declarations were given further stimulus in 2007 with the establishment of the International Campaign for a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, an umbrella organization that, as of 2018, has brought together over 150 civil society groups and 1540 parliamentarians from 123 countries. It defines itself as:

a global network of parliamentarians, non-governmental organizations, scholars, and dedicated citizens that advocates democratic representation of the world’s citizens at the United Nations. A United Nations Parliamentary Assembly, UNPA, for the first time would give elected citizen representatives, not only states, a direct and influential role in global policy.Footnote 13

The World Federation of United Nations Associations issued a resolution at their World Congress on October 21, 2018, stating that it “supports steps towards the creation of a United Nations Parliamentary Assembly” and that the UN “must address the democratic deficit within global decision-making processes” if it is to be successful “in the pursuit of creating a better world for all and ensuring that no one is left behind.”Footnote 14 A similar resolution was issued in May of 2016 by the Pan-African Parliament.Footnote 15

Despite these initiatives and prominent statements, it is reasonable to assume that there will be some opposition. The obstacles are likely to be of at least two kinds. First, there may well be resistance within some of the member states of the UN, for whom institutional inertia is a defining characteristic. This might be particularly the case for some of the larger states, including those with veto power in the Security Council, which might hesitate to introduce institutional innovations that could upset internal power relationships or that might introduce a degree of unpredictability – or simply change – in the management of UN affairs. For that reason, it will likely be necessary to approach this project in a multistaged way. In the first instance, the WPA would, as described above, be set up as a consultative body, with the power to make recommendations on issues of international concern but with no effective political power; an adjunct institution to the General Assembly with responsibilities that would be difficult to perceive as a threat to the established political order. Learning from past experience, it would be useful to continue to support the building of a civil society coalition that would make the case for the establishment of such a body and would seek to obtain the support of sympathetic governments to play a catalytic role within the General Assembly, building a critical mass of support. In this regard, governments such as that of Canada and the European Parliament could be potentially important allies.

There is, moreover, a useful model to guide the future evolution of the WPA. The European Parliamentary Assembly was established by the six founding members of the European Economic Community (EEC) (Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands) and met for the first time on March 19, 1958. It initially had 142 members drawn from the parliaments of the EEC’s six members, with the Assembly subsequently changing its name to the “European Parliament” in March 1962. In the early years, members of the European Parliament served in a dual national and European capacity, but at a Summit Conference in Paris in December 1974 the decision was taken to move to direct election of members by universal suffrage, with the first such election taking place in June 1979. With the accession of Denmark, Ireland, and the United Kingdom in 1974, the number of members of the European Parliament (MEPs) was increased to 198. Successive enlargements took place with the accession of Greece in 1981, Spain and Portugal in 1986, and other countries in later years. The Treaty of Lisbon in 2009 capped the number of MEPs at 751.

More important, however, than these membership enlargements, reflecting the growth of the EU from 6 to 28 members over the past several decades, has been the expansion of its powers. The Treaty of Luxembourg significantly expanded the powers of the Parliament in budgetary matters in April of 1970, to coincide with a shift in the sources of funding of the EEC, from member state contributions to its own resources. The 1987 Single European Act made accession and association treaties for prospective new members subject to parliamentary approval. The Maastricht Treaty in 1992 expanded the powers of Parliament by making the membership of the Commission subject to parliamentary approval, de facto giving it control over the EU’s executive functions. These powers were further expanded with the Treaty of Amsterdam in 1997, which devolved to the European Parliament certain powers from national governments to other areas such as legislation on immigration, adopting European legislation in certain areas of civil and criminal law, and foreign and security policy. The Treaties of Nice (2001) and Lisbon (2009) saw further expansion of the Parliament’s powers, with the latter adding some 45 areas where the Parliament would essentially share a codecision role with the Council of Ministers.

From its humble beginnings as a parliamentary assembly in 1958, the European Parliament has moved over the past decades to the center of decision-making on issues of concern to the European Union and has attained a large measure of democratic legitimacy. Interestingly, its members are not grouped by nationality but by broadly shared political persuasions or beliefs, suggesting that shared ideas and values are now considered more important that political geography. A European Parliament model, with stages of incremental and progressive development (e.g., by initially establishing a parliamentary advisory body at the UN under Article 22 of the Charter), however, is not the only proposal on the table for the setting up of a WPA at the UN. Some have suggested an amendment to the UN Charter under Article 109 to establish a more robust legislative body in the first instance (see Chapter 4) which, however, requires the approval of two thirds of the UN’s members and the assent of all permanent members of the Security Council, a high barrier to clear.Footnote 16

Launching a WPA under the power given to the General Assembly under Article 22 to establish subsidiary organs may be a more promising approach than seeking an amendment to the Charter. Indeed, the case can be made that getting 129 members of the General Assembly to support a WPA resolution would not be an insurmountable obstacle since there is, in general, broad awareness that, as currently constituted, the United Nations is no longer “fit for purpose” and there is a need to narrow the governance gap associated with our collective inability to confront serious global problems. If anything, this sense that our current global order is in need of significant repair might well intensify in coming years, under the onslaught of a multitude of unresolved global problems.

A possibly more promising and speedier approach than persuading 129 members of the General Assembly to launch a WPA could be through a standalone treaty which might get the WPA off the ground with the participation of some 30 members, representing a broad spectrum of the UN’s membership. This could set a process in place for the subsequent ratification by other members. A similar procedure was followed, of course, for the creation of some of the UN’s leading and/or long-standing organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Labor Organization (ILO).

In any event, as the above discussion makes clear, there are multiple paths to the establishment of a WPA. Another possibility would be to follow the model used in the negotiations of the Land Mines Treaty; a “single negotiating text method” could be adopted for the creation of the WPA, with first discussions taking place outside UN structures. Initial efforts to establish the WPA in this scenario could include consultations between like-minded, sympathetic stakeholders and could be enabled by the support of a core group of supportive states. While desirable, it would not be essential to have the consent of all or even the majority of nations to get this institution off the ground. Any state could join this initiative and it is expected that citizens would urge their governments to support the WPA. In time, as the WPA gained democratic legitimacy, it could be integrated into the international constitutional order, attached as an advisory body to the General Assembly, consistent, as noted earlier, with Article 22 of the UN Charter that empowers the Assembly to create “subsidiary organs.”

It is not unreasonable to expect that WPA members, given their closer links to national parliaments and their constituents, might then see themselves less bound to national interests and priorities. Diverse coalitions might then emerge and the WPA’s very existence would contribute to finding creative solutions to global problems. The power, ingenuity and efficacy of coordinated transnational civil society movements, including “smart coalitions” with like-minded states, have proven themselves in the recent remarkable successes of, for example, the creation of the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the Land Mines Treaty (see Chapter 21 for more information on transnational civil society coalitions and “citizen diplomacy”).

A second kind of objection or obstacle to the establishment of a WPA, as discussed in Chapter 4 in relation to a significantly reformed General Assembly, would likely stem from a potential lack of agreement on the basic architecture of such an organ. Who would be its members? What would be the criteria for representation in a community of member nations ranging in population size from China and India to Palau and Nauru? How would one address the issue of the nondemocratic nature of many of the members of the UN? Would countries’ participation in the WPA be based on the principle of one-person-one-vote or some other principle that could be applied consistently across all members? Might democratic nations object to the participation of nondemocratic/authoritarian regimes in an institution that would have as a key primary purpose to bring to the UN a measure of democratic legitimacy?

These are central questions, but they are amenable to sensible proposals and solutions that will be useful in planning the broader UN reform. Obviously, the design of the WPA’s architecture would have to employ a consultative process and involve a broad cross-section of humanity. A high-level panel, or expert group, within or external to the UN could be set up to review existing answers to the above questions and to suggest, as needed, alternative avenues. In the pages that follow we put forward two alternative proposals, one that builds on the work done in this area by Dieter HeinrichFootnote 17 and Joseph SchwartzbergFootnote 18 and another which was originally proposed by Richard Falk and Andrew Strauss.Footnote 19 These proposals are distinctive from those set out in Chapter 4, as they are relevant for an Assembly at first constituted by members appointed or chosen from members of national parliaments or similar bodies.

A Modified Heinrich/Schwartzberg WPA

Heinrich and Schwartzberg envisage a WPA made up of members appointed by or chosen from members of national parliaments of UN member states, a proposal very much in the spirit of the formation of the European Parliament. Neither is opposed to the direct election of members, but both consider it as being premature; a complex undertaking for which, given the diversity of the UN membership and the different political regimes currently in existence, the international community is not yet ready for. It is, of course, a desirable goal for the future, a natural conclusion to an evolutionary process that would have several intermediate stages. As a start, national parliamentarians as members of the WPA would certainly bridge in a clear way part of the democratic deficit at the UN. They would in general be more representative of the populations of their respective countries than unelected government bureaucrats and/or diplomats serving their countries at the United Nations. As they would generally do in their home countries, members of the WPA would see themselves as representing their countries’ citizens and could play the role of advocates for the United Nations in their home countries. Their participation in the WPA should also broadly reflect the distribution of political power in the national parliament across the different political parties and persuasions (e.g., right, left, green, etc.). Furthermore, we would strongly favor the introduction of some gender quota system, to ensure sufficient gender diversity in the WPA. At the moment, according to data compiled by the Interparliamentary Union, on average the share of women in parliaments worldwide in 2019 stands at slightly more than 23 percent. There is credible evidence from a range of studies about the benefits of higher participation of women in village councils, national parliaments, corporate boards in publicly listed companies, and other such decision-making bodies; introducing approximately a 40 percent quota for women in the WPA, therefore, would be highly desirable.Footnote 20, Footnote 21

There would be no obligation for countries to participate in the WPA; member country governments could opt out if they wished. Countries could also be given the option to choose distinguished citizens (e.g., former members of national parliaments, retired judges, eminent citizens at large) as WPA members if they felt that the double burden of serving in the national parliament and the WPA might represent an excessive claim on their time, particularly if, as could be expected, the WPA would be available for business and deliberations during a not insignificant portion of the calendar year. By the same token, countries that felt they had the institutional machinery in place for the direct and credible election of WPA members from the outset could not reasonably be prevented from opting to do so, in a voluntary fashion. The activities of the WPA would be funded from the UN budget and the cost of its operations is not initially expected to be onerous. In any event, as we discuss in Chapter 12 on a new funding mechanism for the UN, there would be adequate resources available to finance these activities under the 0.1% of gross national income (GNI) annual funding target we are recommending.

Members could serve for four-year terms, subject to a two-term limit. We think that this would be desirable to avoid the emergence of a professional political class for which long tenures in office can sometimes contribute to a shift in incentives and motivations, with remaining in office at times overriding all other considerations. Deliberative bodies can also benefit from infusions of fresh blood, new perspectives and the energy of younger (and maybe more idealistic) new generations of leaders. One would hope also that the WPA would be good training in the workings of democracy, and this could be an invaluable experience for members from countries with limited, imperfect, or nonexistent traditions of consultative democracy. We also think that there is merit in the idea that WPA members should be provided with legal protections, in particular against possible retaliation from their home governments for taking positions that they might perceive in the global public interest, but which governments might judge as counter to established national priorities and/or policies, as determined by the government then in power.

One early challenge in the setting up of the WPA would be how to manage the participation of nondemocratic and/or authoritarian regimes. Painful tradeoffs are likely. On the one hand, since the WPA is brought into being to imbue the UN with a greater degree of democratic legitimacy, one would favor processes for the election of its members that would exemplify the very principles of accountability, transparency, consultation, and rule of law that underpin accepted norms of good governance (as discussed in Chapter 20 on the principles and values underpinning global governance reforms). On the other, one would wish a WPA that was truly universal in its representation of the human family and this would mean, inevitably, including those parts of the world where citizens, often through no fault of their own, are ruled by autocratic regimes and governments that either do not believe in the periodic legitimization of rule through the ballot box and/or would not wish to put themselves through that test. How to guard against, for instance, China ensuring that all of its (likely several dozen) members to the WPA would be card-carrying members of the Communist Party?

There may be no easy solution to this particular quandary in this first stage of the WPA, where its role will be largely advisory. Laurenti regards the existence of nondemocratic states as being an insurmountable obstacle to the creation of a WPA, because the presence of representatives from these countries (e.g., Belarus, China, Cuba, North Korea, Sudan, Syria, Venezuela, many countries in the Arab world, and a significant number in sub-Saharan Africa) would undermine the WPA’s desirable democratic character.Footnote 22 We do not wish to minimize the importance of this concern. However, the existence of authoritarian regimes did not prevent the creation of the UN itself and the General Assembly’s membership is made up of fully democratic states, some that are flawed in their democratic character, and many others that are characterized by various shades of authoritarianism.

That is, unfortunately, the state of democracy in the world today. Close to 32 percent of the countries included in The Economist’s Democracy Index 2018 are authoritarian regimes of some form or other.Footnote 23 But, as noted earlier, their presence in the General Assembly has not prevented that body from endorsing democratic and participatory forms of governance as the most desirable option for its members. Thus, rather than wait for the time when all members will be democratic (possibly a very long time), we would favor an approach that was broadly inclusive, and that as long as the majority of the WPA’s members were democratic, the Assembly could still function effectively and be a catalyst for change. Laurenti also raises questions, with the possibility of the appearance of this new global institution, about the willingness of citizens to tolerate the stresses that would be placed upon them by the existence of a global “mandatory regime” that would be “dominated by people unlike themselves,” by “aliens” as he calls those of a different nationality.Footnote 24 We will come back to this issue in the last section of this chapter. Suffice it to say now that, in the early stages, there is very little in our vision of a WPA that is “mandatory” in nature; its role would initially be largely advisory, like the European Parliamentary Assembly set up in 1958.

One possible compromise, for instance, might be for the General Assembly resolution establishing the WPA to set out a list of minimum qualifications that would need to be fulfilled to be accepted into membership. If, for instance, one possible criterion for membership would be that there be no pending legal cases against the member for financial improprieties, 40 percent of the members of the Brazilian legislature would be automatically disqualified. More generally, rather than establishing criteria that would aim for the lowest common denominator, one would wish to encourage the selection of members that were recognized objectively for their integrity and a distinguished life of public service. In this respect, one option worthy of serious consideration would be to ask national parliaments (or similar bodies, where parliaments do not exist) to elect their WPA members by secret ballot, to free voting members from the usual sectarian/partisan, or other pressures that so often stand in the way of electing the most capable and worthy candidates.Footnote 25 In any case, given the current state of democracy in the world, it is to be expected that the WPA would have a clear democratic majority among its members.

Distribution of WPA Membership

A central issue to resolve is the determination of country membership in the WPA. The principle of one-person-one-vote, at this stage in human history at least, likely poses insurmountable practical challenges. China’s population overwhelms that of most other countries; this would result in highly skewed membership in favor of China, a nondemocratic UN member. Understandably, there might be strong opposition to the creation of a body intended to boost the democratic legitimacy of the United Nations being dominated in its membership by a country with a very limited tradition of democracy. For this reason, Schwartzberg, for instance, goes back to the criteria that he proposed for determining voting power in the General Assembly, consisting of three elements: population share (P), relative contributions to the UN budget (C), which, as noted earlier, is a proxy for the share of the country in world GNI, and a membership factor (M) which is simply 1/193 percent, to represent a country’s current voting power in the General Assembly under the one-country-one-vote system. The arithmetic average of these three shares (P + C + M)/3 = W determines a country’s relative weight or share in the WPA membership.

The total number of seats in the WPA for country j, Sj, will then be determined by the ratio of Wj to D, where D is defined as the weight for the smallest member. Thus, to take the example of China, Wj = 11.993, as derived in Table 4.1. For the 193 members of the United Nations, D = 0.173. So Sj for China would be 11.993/0.173, which rounded to the nearest integer translates into 69 members in the WPA. For Bangladesh Wj = 1.015 from which one can derive that, rounded to the nearest integer, the country would have six WPA members. Table 5.1 below presents a summary of the data, using population and GDP figures for 2017. The WPA would thus have a total of 567 members, with the United States (48), India (46), and Japan (14) having the second, third and fourth largest representations. A total of 107 countries would have one representative each. While these countries account for 5.9 percent of the world’s population, they would nevertheless account for 18.9 percent of the total number of seats in the WPA. This reflects the bias toward small countries which the Schwartzberg proposal builds in deliberately through the introduction of the “UN membership” factor in the determination of the membership weights. Three countries, China, the United States, and India, accounting for 41 percent of the world’s population, would have a total of 163 representatives, or 28.7 percent of the total. Each of the deputies representing countries small enough to have only one WPA member, would represent an average of 4.1 million people, whereas one of the Chinese representatives would represent some 20 million people.

Table 5.1 UN member state representation in a WPA: Modified Schwartzberg/Heinrich proposal

| Seats per nation 1 | Number of nations | % | Number of seats | % | Population in millions | % | Average population per seat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 107 | 55.4 | 107 | 18.9 | 441.08 | 5.9 | 4.1 |

| 2–3 | 58 | 30.1 | 127 | 22.4 | 1422.41 | 19.0 | 11.2 |

| 4–9 | 20 | 10.4 | 112 | 19.8 | 1745.90 | 23.3 | 15.6 |

| 10–20 | 5 | 2.6 | 58 | 10.2 | 827.26 | 11.0 | 14.3 |

| 21–69 | 3 | 1.6 | 163 | 28.7 | 3051.29 | 40.7 | 18.7 |

| Total | 193 | 100.0 | 567 | 100.0 | 7487.94 | 100.0 | 13.2 |

1 Seats per nation determined by relative population and GDP shares, as well as UN membership factor as described in text.

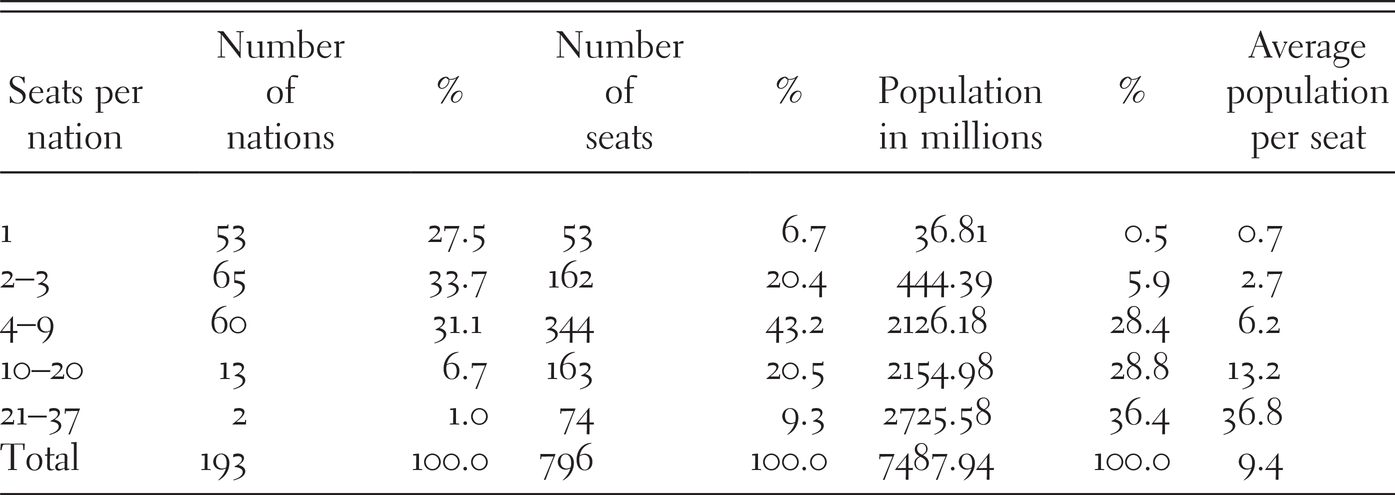

The above method could be in operation for four parliamentary terms, lasting a total of 16 years. It is expected that during this period the WPA would gain in legitimacy having joined in or influenced numerous General Assembly resolutions, having taken up for debate and made recommendations on a broad range of matters of international concern, including those issues that straddle national borders, such as climate change, human rights, poverty, income distribution, gender equality, rule of law and the like, and having mobilized public opinion in support of the goal of strengthened international cooperation. As the profile of the WPA expanded, a case could be made to move to a system that determined membership in the body solely on the basis of population, but in a nonlinear way, relying on the principle of degressive proportionality, meaning that smaller states would be entitled to more seats than would be called for under a system that allocated places strictly in proportion to their population. One such option would be the so-called Penrose method which assigns seats in relation to the square root of the country’s population, rounded to the nearest million, subject to the proviso that all countries will be entitled to at least one member. Table 5.2 shows that two countries, China and India, accounting for close to 37 percent of the world’s population, would have a total of 74 members, or slightly over 9 percent of the membership, each of whom would represent some 37 million people. The Penrose method therefore has the effect of reducing further the share allocated to the most populous states, as reflected in the larger number of people represented by each WPA member.

Table 5.2 UN member state representation in a WPA: Seat distribution as per Penrose population1

| Seats per nation | Number of nations | % | Number of seats | % | Population in millions | % | Average population per seat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 53 | 27.5 | 53 | 6.7 | 36.81 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| 2–3 | 65 | 33.7 | 162 | 20.4 | 444.39 | 5.9 | 2.7 |

| 4–9 | 60 | 31.1 | 344 | 43.2 | 2126.18 | 28.4 | 6.2 |

| 10–20 | 13 | 6.7 | 163 | 20.5 | 2154.98 | 28.8 | 13.2 |

| 21–37 | 2 | 1.0 | 74 | 9.3 | 2725.58 | 36.4 | 36.8 |

| Total | 193 | 100.0 | 796 | 100.0 | 7487.94 | 100.0 | 9.4 |

1 Penrose population is defined as the square root of a country’s population in millions.

We have presented the above two scenarios to underline that there is a range of possibilities for the determination of membership shares in the WPA. The issue is partly technical and partly political. The European Union does not use a fixed formula to determine the relative representations of national deputies in its parliament; country shares are periodically negotiated and some nontangible factors may enter into the consultations, affecting the ultimate outcome. While it will be necessary to come up with a membership mechanism that will be perceived as reasonably objective, fair-minded, and enhancing the credibility of the WPA before the public, a considerably more important set of issues will be those concerned with the functions of the WPA, its role within the UN system, its relation to the General Assembly, and the role it would play in strengthening support at the global level for the United Nations.

Schwartzberg envisages an ultimate transition for the WPA where membership in it would be completely delinked from the nationality of its members. Abstracting from national borders, one would divide the world into a sufficiently large number of electoral districts and elect members for the WPA in each district, broadly in conformity with the principle of one-person-one-vote. We do not believe that this approach would be feasible in anything like a reasonable time frame as it would likely skew the membership of the WPA toward the more populous states and thus would be resisted by many member states. Even in the European Parliament, already operating under a system of broad degressive proportionality, the criterion for membership is still based on the nationality of candidates. What is likely to happen in the EU – and could thus be a harbinger for the future as regards the whole world – is that with increased intra-EU migratory flows, there will be shifts in the composition of national populations over time with, for instance, a significant proportion of the population of Spain, say, being of non-Spanish origin, mainly from other EU states. Made eligible to vote and to be voted for, one could imagine a situation where Spain’s WPA contingent could have a significant number of non-Spanish members. Something like this, of course, has already happened within national territories; there is no impediment whatsoever for a member of the Spanish parliament representing, say, Madrid, to be a former resident of Barcelona or Bilbao. As of now, the only requirement is that he/she be a Spanish citizen. In keeping with this analogy, one would say that in that distant future, the only requirement for membership in the WPA would be that the person be a world citizen.

One important question to settle over the longer term is whether the WPA would retain indefinitely its role as an advisory body, with the locus of political power remaining firmly in place with the General Assembly, whose members would, as noted earlier, be ultimately elected by popular vote. And, if the answer to this question is no, suggesting in time a more political role for the WPA, how would these powers relate to those already granted, in a revised Charter, to the General Assembly? We do not think that this difficult issue needs to be decided now. There is considerable merit to the idea of introducing within the UN the institutional infrastructure for an advisory mechanism, as soon as possible, that more fully reflects the aspirations and priorities of the people, not just nation states as is the case with the General Assembly today. If the UN Charter amendments that would make it possible to introduce a system of weighted voting in the General Assembly are a longer-term goal, then the coming into being, in a much shorter time horizon, of a WPA with extensive advisory powers is an initiative worth pursuing on its own merits. Whether to grant the WPA powers that transcend the merely advisory is a decision that can be taken after the General Assembly is in operation as a budding world legislature, with narrowly defined powers in the areas of peace and security and management of the global environmental commons, under a system of weighted representation. What is clear, however, is that a WPA in operation would be an excellent preparatory step for the eventual emergence of a General Assembly with legislative powers.Footnote 26