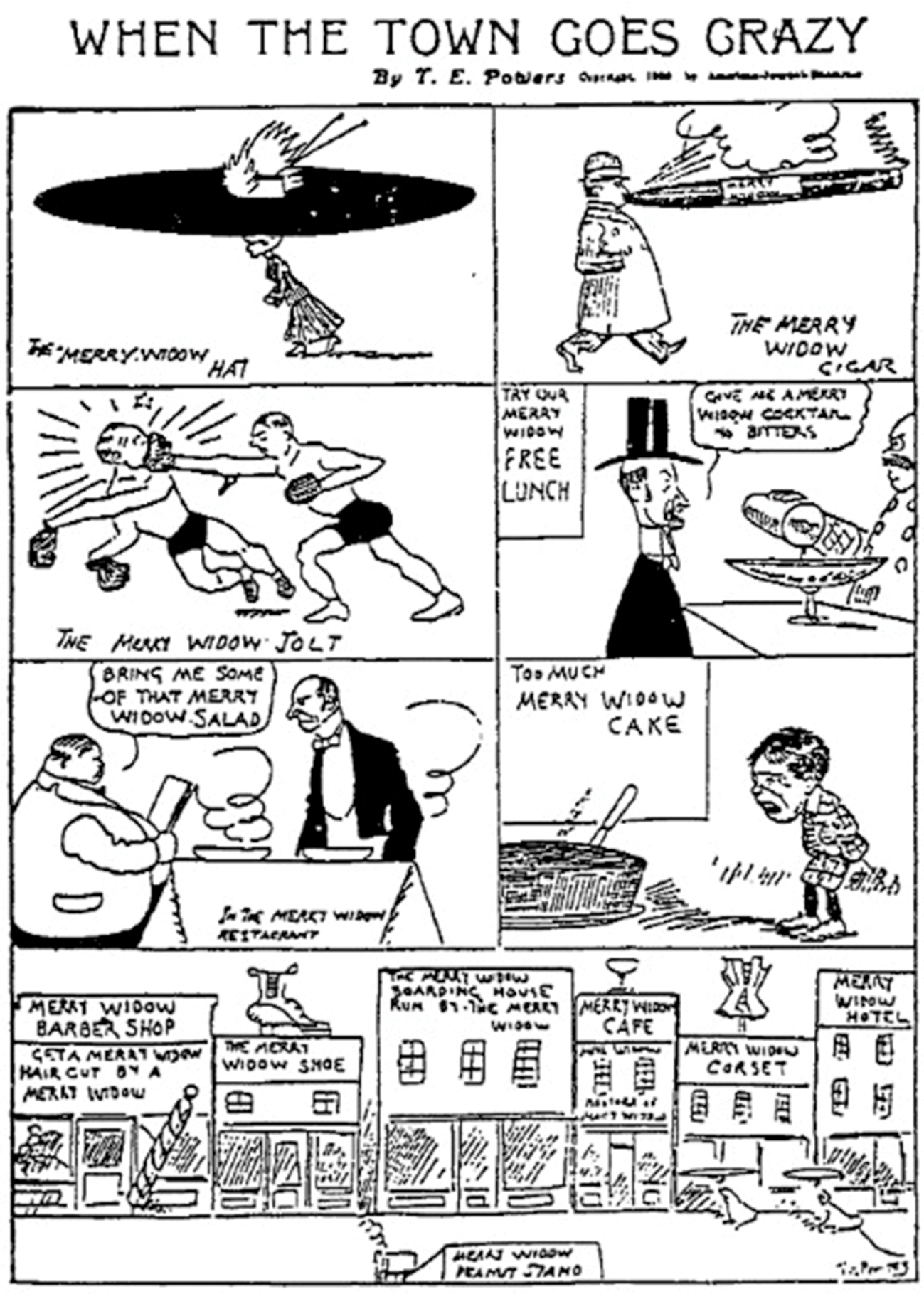

It was, above all, the romantic melodies and rich harmonic textures of operetta that attracted British and American audiences. B. W. Findon, editor of The Play Pictorial, claimed that the chief factor in the success of The Merry Widow was its music. He wrote enthusiastically, ‘I have assisted at no first night since the production of “The Gondoliers” in which the music has been so consistently melodious and ear haunting’, and went on to explain that the desire to hear the music again was the main reason for repeat visits to the theatre; it is ‘the factor which always makes for long runs’.Footnote 1 A reviewer of the Broadway production followed a similar train of thought, commending the scenery, but insisting ‘it is on its music that “The Merry Widow” depends for its chief success’.Footnote 2

Characteristics of Musical Style in Operetta

The music of operetta occupied a number of positions between popular musical theatre and opera. Lehár’s most operatic scores were Zigeunerliebe (Gipsy Love in London, Gypsy Love in New York) and Giuditta. Findon remarked on the operatic qualities of Gipsy Love, noting that it demanded skilled singers, such as Robert Michaelis and Sári Petráss.Footnote 3 Kálmán’s most operatic score was Die Bajadere (The Yankee Princess on Broadway), and Gilbert’s most operatic score was Die Frau im Hermelin (The Lady of the Rose in London, The Lady in Ermine in New York). Findon commented on the ambitious character of the latter, its being almost through-composed, with little dialogue until the third act.Footnote 4 There were composers who moved in the opposite direction, introducing an operetta-like character into their operas, as did Puccini in La Rondine and Richard Strauss in Der Rosenkavalier. Ironically, when Hugo von Hofmannsthal heard Lehár’s Libellentanz, he said how beautiful it would have been if Lehár had composed the music to his Rosenkavalier libretto.Footnote 5

Dance rhythms formed an important part of the style of every operetta composer but did not prevent the cultivation of individual stylistic characteristics. Leo Fall’s distinctiveness is explained by Richard Traubner:

A song which sums up the Fall spirit might be ‘Das ist das Glück nach der Mode’ from Die Rose von Stambul. Kálmán could not have written it, nor Lehár. It is too gay, too conversational, perhaps too flippant. Its refrain does not attempt to soar in a Puccini-esque way but the whole is, preeminently, a brilliantly soaring sung waltz.Footnote 6

That said, Fall produced for the same market as other operetta composers and had life experiences in common with them. His father was a military bandmaster, as was Lehár’s (and Sullivan’s), and, like Lehár and Kálmán, he was not Austrian. His nationality at the time of his birth was Moravian, which would be Czech today. In his teens, he had studied at Vienna Conservatory, but then, like Oscar Straus, he worked in Berlin in the 1890s. He was the least fortunate among the most admired of silver-age composers in having his career cut short by cancer, resulting in his death in 1925, aged 52. Like many of the most successful operetta composers, Fall was Jewish. Thus, it seems no coincidence that composers involved in the American invasion of London’s West End in the mid-1920s were mostly of European Jewish stock (the fathers of Jerome Kern and Richard Rodgers were German Jewish immigrants, and George Gershwin’s father was a Russian Jewish immigrant).

In Adorno’s opinion, Straus and Fall possessed some artistic merit because they retained links to Viennese classicism:

Oscar Straus learned his craft from the Viennese tradition, and strove to compose a richer operetta music, but was faced with two choices, either to align himself with industrialization, or, in cultivating arts and crafts, lack the social impact of Johann Strauss. Leo Fall was the last to retire with some decency from the affair.Footnote 7

However, it needs to be borne in mind that Straus was also influenced by cabaret music. He lived for several years in Berlin, where he built a reputation at the Überbrettl cabaret in Alexanderplatz, and he had also toured with cabaret singer Božena Bradzky. Heinrich Reinhardt, the composer of Der Opernball, distanced Straus from the Viennese tradition by claiming that the sounds of the Überbrettl gave a certain elegant capriciousness to his music that was not at all Viennese.Footnote 8 It is heard in Die lustigen Nibelungen (1904), with a libretto by Rideamus (Fritz Oliven), in which satire is directed at earnest Wagnerians more than at Wagner. Yet Reinhardt’s comment goes too far in the case of Ein Walzertraum, the Viennese qualities of which can be distinctly heard in the waltz duet for two tenors, ‘Leise, ganz leise’. Straus was receptive to a variety of music, and one of the biggest impressions made on him occurred on 1 September 1886, when, aged 16, he went to the Carltheater to see The Mikado by Gilbert and Sullivan. It opened his eyes and ears to new possibilities and remained one of his favourite stage works.Footnote 9 He had intended to study composition with Léo Delibes in Paris in January 1891, but Delibes died just before his arrival. So, instead, he endured three years of Prussian musical discipline from Max Bruch in Berlin, who castigated him for his ‘wretched inclination towards frivolity’.Footnote 10

Lehár, too, wins Adorno’s respect for being acquainted with the demands of ‘art music’, and possessing a sense of aesthetic responsibility that prevented his operettas from becoming mere market articles, even if they bore ‘the musical sign of industrialized production’, which was ‘the complete elimination of all contrasts within melodies, and their replacement with sequences’.Footnote 11 He cites the waltz in Die lustige Witwe as an example. A melodic sequence entails the repetition of a musical motive or phrase at a higher or lower pitch – often modified in some way – and may simultaneously include sequential harmony. Ascending sequences, such as found in ‘Mein Held’ in Der tapfere Soldat (The Chocolate Soldier in New York and London) are more common than descending sequences. ‘Leise, ganz leise’ in Ein Walzertraum has a descending modified sequence in the first eight bars. Yet sequences are by no means omnipresent in operetta: for instance, Achmed’s song ‘O Rose von Stambul’ in Fall’s Die Rose von Stambul is not in the slightest sequential.

In composing songs for operetta, consideration might be given to the technique of a particular singer. Lehár often composed with Richard Tauber’s voice in mind, knowing the range of timbre he possessed across the vocal registers, and how gently he could sing high notes. Stefan Frey remarks that Lehár’s later lyrical operettas were tailored to the Tauber style.Footnote 12

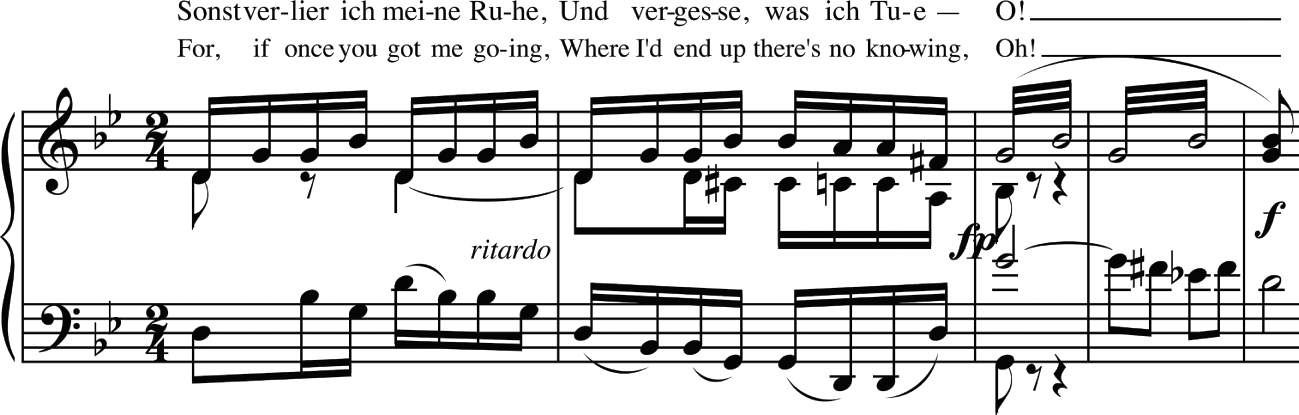

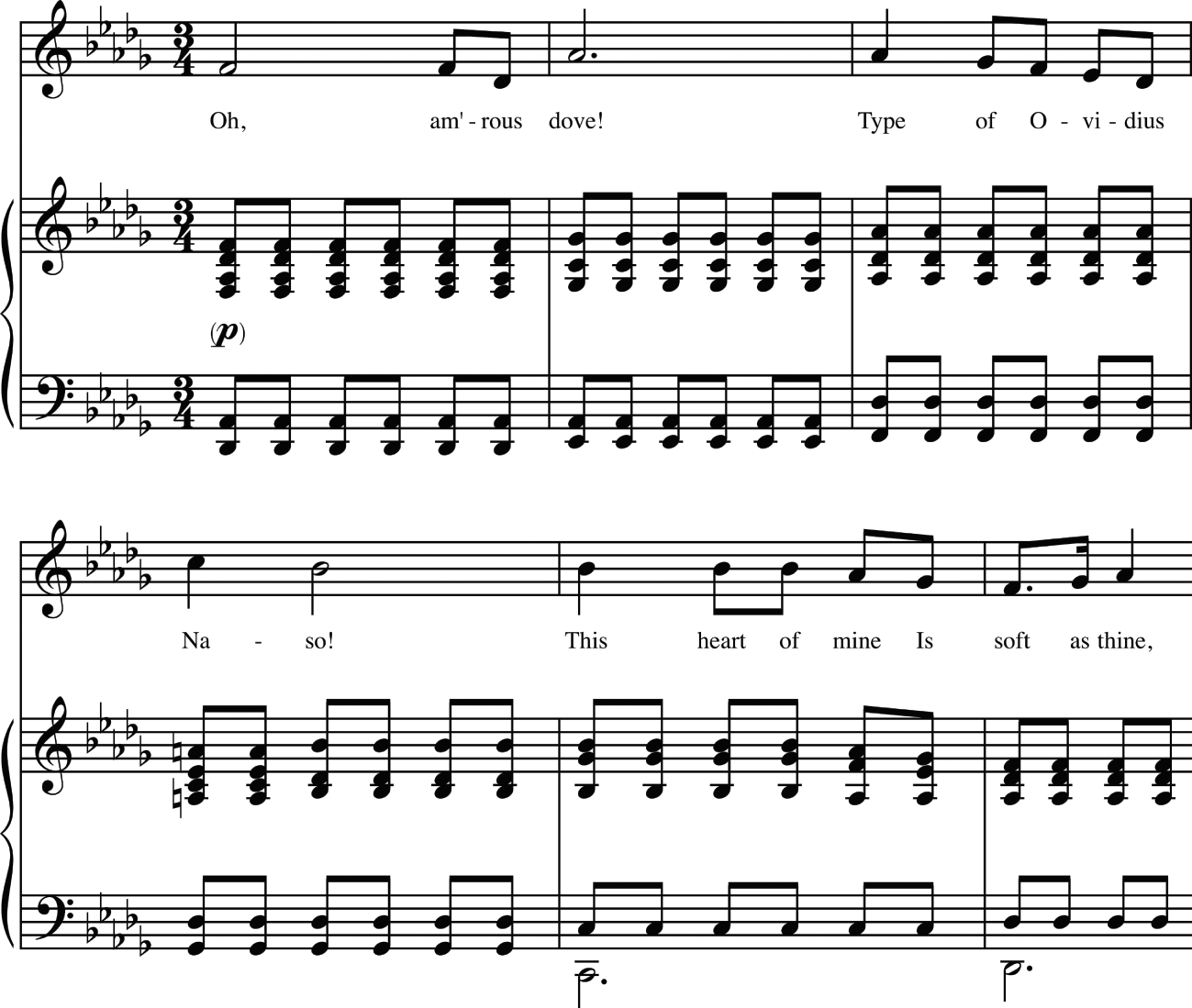

By the turn of the twentieth century, the free-floating sixths, sevenths, and ninths that had worked their way into the Viennese popular style were a regular feature, and could be used confidently without even a hint of resolution.Footnote 13 ‘Walzer, wer hat dich wohl erdacht’ in Act 3 of Das Fürstenkind shows how, by 1909, free floating sixths and sevenths could be used flexibly as colourings of tonic harmony (Example 1.1).

Example 1.1 ‘Walzer, wer hat dich wohl erdacht’.

These dissonances add stimulating tension to the music. Note how the melodic phrase at ‘Walzer ganz allein’, which ends on a major 7th, lends an erotic frisson to ‘Ein Walzer muß es sein’ in Die Rose von Stambul (Example 1.2). Volker Klotz describes this duet as ‘utterly Viennese dance eroticism’.Footnote 14

Example 1.2 ‘Ein Walzer muß es sein’.

The harmonies used in operetta could sometimes be adventurous. ‘Tiefe Nacht’ from Eduard Künneke’s Zauberin Lola (1937), for example, has harmonies and modulations reminiscent of Richard Strauss. Writing of Künneke’s Der Tenor der Herzogin (1930), Adorno declared: ‘It cannot be denied that Künneke is musically superior to the operetta average; by competent and careful instrumentation, a (relatively) selective awareness of harmonic or melodic shape; also, some knowledge of more advanced jazz achievements’.Footnote 15 Künneke had spent 1924–25 in New York, and, by the time he came to compose Traumland (1941), his music was influenced extensively by American styles, including the new swing style.

Künneke aside, Adorno comments sarcastically on operetta harmony: ‘Genuine modern operetta melodies must be harmonized with impressionistic ninth-chords and whole tones’.Footnote 16 Extended harmonies are not difficult to find, but they sometimes go further than may be expected: for example, a supertonic eleventh harmony appears six bars before the close of ‘Fredys Lied’ in Act 1 of Die Dollarprinzessin (see the first bar of Example 1.3). In earlier times, this would have been harmonized with a second-inversion tonic triad.

Example 1.3 Close of ‘Fredys Lied’.

Gilbert extends the tonic chord with major sevenths and ninths in the song ‘Silhouettes’ in Act 1 of The Lady of the Rose (1922) (see bars two and four of Example 1.4).

Example 1.4 ‘Silhouettes’.

Abraham employed bold extended harmonies in Ball im Savoy (1932), as the end of the Prelude illustrates (Example 1.5).

Operetta is not celebrated for its imaginative use of polyphony, but contrapuntal interplay does exist. For example, the uniting of two themes, a favourite device in the Savoy operas, is found in the duet ‘Komm mit nach Madrid’ in Lady Hamilton (Song of the Sea in London) alongside other examples of Künneke’s contrapuntal skill in that operetta. His technical ability in counterpoint was already evident in Der Vetter aus Dingsda (Caroline in New York, The Cousin from Nowhere in London) which replaced choruses with subtle ensemble work, such as the ‘Roderich’ and ‘Batavia’ septets in Act 2. He had studied composition in Berlin with Max Bruch, who despised operetta and took pleasure in setting contrapuntal exercises. Künneke, like Abraham, was at first drawn to ernste Musik, and his first stage work, Robins Ende (1909), was designated a comic opera rather than an operetta. Kálmán, too, shows an understanding of polyphony in the finales of Das Hollandweibchen (1920), given in London as A Little Dutch Girl, although his interest in counterpoint declined in later works. The counterpoint in the duet ‘Niemand liebt dich so wie ich’ in Paganini shows that Lehár also possessed skill in this area, even if he did not always reveal it in his ensembles. It is far from the sweetly harmonizing thirds and sixths of the typical romantic love duet. The Act 2 duet between Pipsi and Dagobert in Eva contains a canon at one bar’s distance. The learned device of canon is not what one would expect to find in operetta, but there is also canon (at two bars’ distance) in the Act 2 finale of Offenbach’s Fantasio, between the Prince and Marinoni (‘Princesse si charmante’).

Silver-age operetta differs in its musical representation of love and romance from the music of the Savoy operas. A comparison of the Fairy Queen’s song ‘Oh Foolish Fay’ in Iolanthe (1882) with Nadine’s ‘Komm’, Komm’! Held meiner Träume’ (‘My Hero’) in Der tapfere Soldat (1908) demonstrates the changes in representational technique. Both characters sing of the man they desire, and the need to control their longing. Both songs contrast a lyrical refrain with a narrative verse containing shorter note values. But that is where the similarity ends. Sullivan employs a throbbing accompaniment in his refrain and composes a melody with sighing appoggiaturas over passing chromatic harmonies. It is marked to be performed softly throughout, even at its climactic point, and there is a decline in tension as it attains closure (Example 1.6).

Example 1.6 Fairy Queen’s song from Iolanthe.

In contrast, Oscar Straus conveys longing with an ever-rising exhortation to ‘come, come’, coupled to a crescendo that it is interrupted unexpectedly by a soft augmented chord at ‘calm my longing, calm my desire’, creating a peculiarly sensual effect. The augmented chord moves, in apparent resolution, to the tonic harmony, but the vocal melody wanders around a dissonant major seventh, sustaining a yearning tension (Example 1.7). The more pronounced sensuality of Straus’s music is then emphasized by another crescendo, which reaches a passionate climax in the final bars.

Example 1.7 ‘Komm’, Komm’!’

Richard Rodgers told Alan Jay Lerner that he thought ‘My Hero’ was ‘the most perfectly constructed song in modern musical literature’.Footnote 17

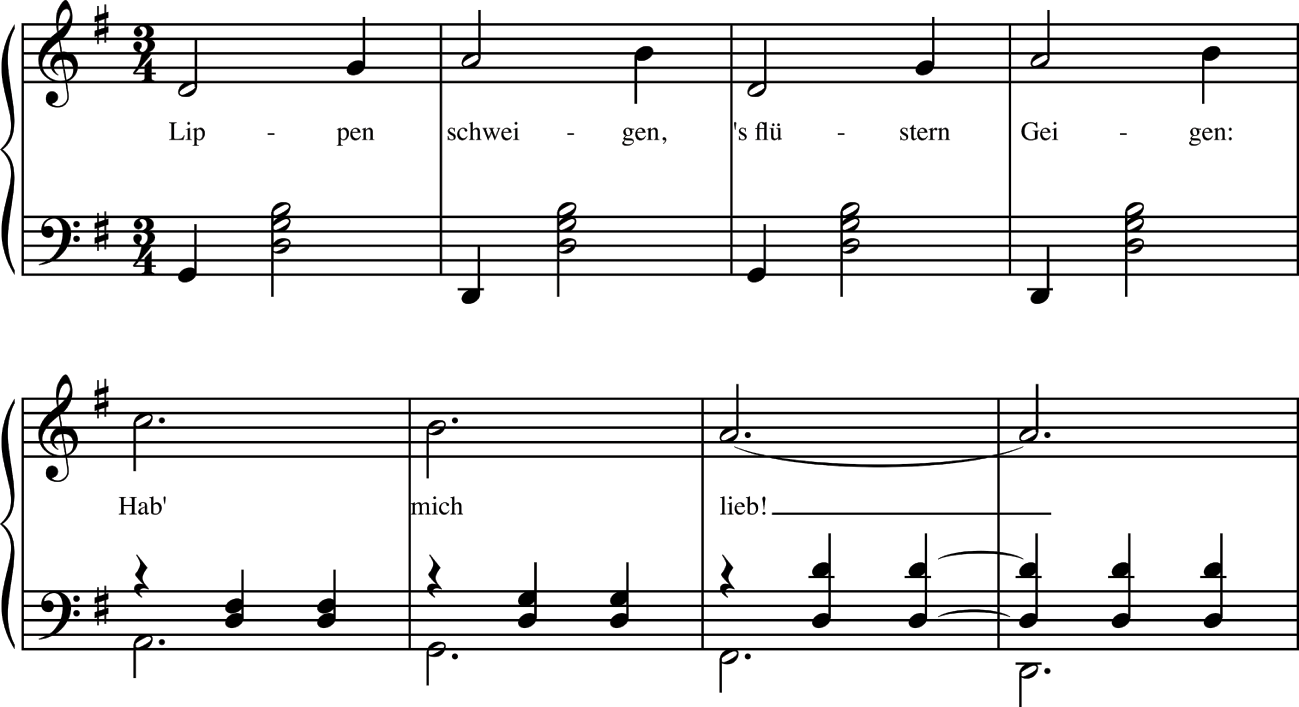

The Importance of Dance

Dance was a vital ingredient in operetta, and performers were generally expected to be able to both dance and sing. The importance of dance to operetta is apparent in titles, such as Ein Walzertraum, Die Csárdásfürstin, and Die blaue Mazur.Footnote 18 In the first decade of the twentieth century, waltzes were the favourite numbers, and this led to a new waltz craze in the UK and USA. Ironically, it was often the continental European take on the English waltz, or what was known in the USA as the Boston waltz (valse Boston), that had the greatest impact. The slower tempo waltz (early examples of which were James Molloy’s ‘Love’s Old Sweet Song’ of 1884 and Charles Harris’s ‘After the Ball’ of 1891) is closer to the famous ‘Merry Widow Waltz’ (‘Lippen schweigen’) than is the faster Viennese waltz. Indeed, the Viennese waltz was beginning to be regarded as less modern than the English waltz, which, by 1912, had become the urban preference, while the former remained the predilection of the rural Hunt Ball.Footnote 19

Twentieth-century operettas were more diverse in musical style than those of the preceding century, and happy to embrace dance rhythms from a variety of sources. The cakewalk was the first distinctly American dance to be imitated in Europe and was included in a number of operettas in the first decade of the twentieth century. Modern dances for couples differed from the old sequence dances, which had preset patterns or figures for groups of dancers. In the half-dozen years before the outbreak of the First World War, the most popular dances were the waltz, the two-step and the lancers (a sequence dance). The two-step gave way to the one-step around 1911. In the years that followed, first the tango, then the fox trot, Charleston, and pasodoble became indispensable parts of the modern dance repertoire and made their way into operettas. The polka remained popular in the UK and USA and continued to be heard in operetta. The csárdás is a special case: it had developed in the nineteenth century into a couple’s dance, although it was danced in and out of hold, especially in the fast section. It continued to appear frequently in operetta but was too associated with Hungarian folk dancing to gain a place in British and American ballrooms.

Lehár kept abreast of the fashionable dances and was the first to include a cakewalk (Die lustige Witwe, 1905), a tango (Die ideale Gattin, 1913), and a fox trot (Wo die Leche singt, 1918). The tango had found its way from Buenos Aires, via Paris, to other cities in Europe and the USA. It may have carried vague associations of the gauchos and headstrong women of the Argentine pampas, but it was actually a modern metropolitan product. There were two main styles of tango rhythm: the march-style and the more modern milonga-style (Example 1.8).

Example 1.8 Tango rhythms.

Most tangos have the syncopated milonga rhythm, but the older style was also liked, and both can be found in operettas of the 1930s: for example, ‘Es muß was wunderbares sein’ in Benatzky’s Im weißen Rössl (1930) is milonga-style, but ‘Sie kommen zum Tee’ in the same composer’s Bezauberndes Fräulein (1933) is march-style. Sometimes a feeling grew that certain dances were overdone in operetta. Hence, the waltz became the subject of parody in Fall’s The Eternal Waltz (1911), as did the csárdás in Kálmán’s Der Teufelsreiter (1932). There are signs that the waltz song was losing its fascination in the 1920s. A critic remarked that José Collins sang ‘the inevitable waltz song’ in Straus’s The Last Waltz ‘with consummate ease’. The word ‘inevitable’ may be a sign of increasing fatigue with the waltz, or an indication of its predictability in operetta. Many composers were already looking to America for musical inspiration – Künneke being one of the first. Ironically, a decade earlier, a New York critic had praised Straus’s The Chocolate Soldier for its variety of music containing ‘everything, fortunately, but rag-time’.Footnote 20

The Impact of Jazz

American music began to increase its presence in London during the First World War, making up for the lack of Austro-German entertainment in those years. When war concluded, jazz of a more pronounced character began to be heard (starting with the visit of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band in 1919). American influence on German operetta had its source in the music-making of African Americans in the period just before the jazz craze of the 1920s. An influential figure was Will Marion Cook, whose significant contributions to musical theatre included Clorindy, or the Origin of the Cakewalk (1898) and In Dahomey (1902), and who founded the New York Syncopated Orchestra in 1918. Another was James Reece Europe, who, in 1913, became the personal musical director of dancers Irene and Vernon Castle. The Castles were the initiators of the fox trot – before the advent of this dance, ragtime was danced to the two-step. Reece Europe performed with his military band in Europe during the whole of the final year of the First World War. Both Tim Brymn and Will Vodery also conducted military bands in Europe during wartime.

In the next decade, white bandleader Paul Whiteman, whose band played in Berlin with great success in 1926, proved a major influence, especially by demonstrating that a syncopated style could work with Tin Pan Alley songs and was not restricted to ragtime and blues. Cornet player Bix Beiderbecke, the son of German immigrants to the USA, performed with Whiteman’s band for a time and was a pioneer in developing a jazz ballad style.

It needs to be borne in mind that the term ‘jazz’ was, for most people in Europe, a general label for modern popular music. The merest association with popular musical theatre or modern dancing could be enough for something to be labelled ‘jazz’. The waltz from Shostakovich’s second Jazz Suite (1938), for instance, bears far more resemblance to ‘Weißt du es noch?’ from Die Csárdásfürstin (1915) than anything that would now be categorized as jazz. Künneke, in Der Vetter aus Dingsda (1921), was one of the first to incorporate styles more closely related to jazz, but Bruno Granichstaedten went further in Der Orlow (1925) by including a jazz band (with saxophones, banjo, and drum kit) playing a shimmy in the third act (Example 1.9).

Example 1.9 Shimmy in Der Orlow.

The excuse for the jazz band was that, in Ernst Marischka’s libretto, a Russian grand duke is living in exile in New York.Footnote 21 Der Orlow enjoyed, perhaps surprisingly, a huge success in Vienna, stimulating demand for American music on the operetta stage there and in Berlin.Footnote 22 It was adapted by P. G. Wodehouse and given as Hearts and Diamonds at the Strand Theatre, London, in 1926.

In post-war London and New York, the waltz had become old fashioned. MacQueen-Pope described Lehár’s The Three Graces, at the Empire Theatre in 1924, as belonging to ‘the London of Waltz Time, not the London of Ragtime and Jazz’.Footnote 23 It did include a fox trot but came across in sum as old fashioned, despite reaping praise for being ‘brimful of delightful melody’.Footnote 24 The modern was now represented by Irving Berlin, Nat Ayer, and Jerome Kern. The next year, Lehár changed tack. Clo-Clo, at the Shaftesbury, was set in the present, and also contained music by Max Darewski – the first time Lehár had permitted interpolations by another composer. A critic complained, ‘Franz Lehár’s melodious Muse has sold herself to that body-shaking St Vitus of discordant orchestral screech sounds known as “Jazz”’.Footnote 25 But Lehár did not continue along the jazz pathway, and such sounds are absent from Das Veilchen von Montmartre (1930). Some dances went out of fashion quickly, but others did not: the one-step, popular just before the war, is still found in ‘Heute Abend komm’ ich zu dir’, in Lehár’s Der Zarewitsch of 1927. In particular, despite the popularity of syncopated dance music, the waltz continued to retain its appeal, and it was to the strains of Oscar Straus’s Three Waltzes, at the Majestic in 1937, that operetta bid farewell to its years of popularity on Broadway.

Knowledge of certain dance rhythms could be imprecise, and J. Bradford Robinson has argued that the German shimmy differed rhythmically, if not metrically, from the American version, which began to be popular around 1920 and was banned as immoral in many dance halls. The shimmy was related to the fox trot in musical style, but not in movement. Couples danced close together in a small space, shaking their shoulders and hips. Instead of the typical American ragtime pattern (quaver, crotchet, quaver, two crotchets), the characteristic rhythm for the shimmy in Berlin consisted of two quavers followed by three crotchets. Robinson cites the shimmy in Ernst Krenek’s Jonny spielt auf and Karol Rathaus’s Der letzte Pierrot as the earliest German sources of the rhythm.Footnote 26 However, these works premiered in 1927, and the rhythm is already being used in Künneke’s Lady Hamilton of 1926, in the duet ‘Komm mit nach Madrid’ (Example 1.10).

Example. 1.10 ‘Komm mit nach Madrid’.

The shimmy in Der Orlow had a related rhythm in the saxophone, beginning with four rather than two quavers, as does ‘Fräulein, bitte, woll’n Sie Shimmy tanzen’, a duet in Act 3 of Kálmán’s Die Bajadere, premiered in Vienna in 1921 (Example 1.11).

Example 1.11 ‘Fräulein, bitte, woll’n Sie Shimmy tanzen’.

The earliest example of a shimmy in operetta is found in the second act of Stolz’s Das Tanz ins Glück (1920), a work produced in London as Whirled into Happiness in 1922, and given in New York as Sky High in 1925. It could easily be mistaken for a fox trot, but the significant difference is that the fox trot’s musical phrases were generally punctuated rhythmically by repeated chords, whereas Stolz’s shimmy has undulations (Example 1.12).

Example 1.12 Fox trot and shimmy rhythmic punctuations from Act 2 of Stolz, Das Tanz ins Glück. The shimmy is transposed for ease of comparison.

The rhythm stuck around, and one of the most familiar examples occurs in the verse accompaniment of ‘Seeräuber Jenny’ (‘Pirate Jenny’) in Die Dreigroschenoper (Example 1.13).

Example 1.13 ‘Seeräuber Jenny’.

It is possible that the shimmy rhythm found in ‘Komm mit nach Madrid’ and ‘Seeräuber Jenny’ had a source in Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, which contains many examples of this rhythm. Paul Whiteman recorded it in June 1924,Footnote 27 and recordings of Paul Whiteman’s dance orchestra became available under a matrix-exchange programme in 1926. Sheet music from the USA had also become more readily available. Robinson suggests the song ‘Papa Loves Mama, Mama Loves Papa’ (by Cliff Friend and Abel Baer) as a possible source of the shimmy figure, because it was a hit in the Weimar Republic in 1924, as ‘Vater liebt Mutter, Mutter liebt Vater’, and spawned imitations.Footnote 28 However, neither Rhapsody in Blue nor ‘Vater liebt Mutter’ help to explain the early date of Kálmán’s shimmy. The explanation may simply be that undulating or repeating notes were intended as a counterpart to shaking of the body when dancing the shimmy. The rhythm certainly had long-lasting appeal: as late as 1930, we find a shimmy, ‘Ich lade Sie ein, Fräulein’ in Bentazky’s Meine Schwester und ich (Meet My Sister on Broadway, My Sister and I in the West End).

The instrumentation of the modern dance band was an influence on Weill’s Die Dreigroschenoper of 1928. The Berlin theatre orchestra sound had been dominated by strings, but some new operettas highlighted wind instruments and included piano, banjo, and drum kit. Several revues by African-American troupes were given in Berlin, 1924–26, and nurtured a familiarity with syncopated styles.Footnote 29 The Berlin theatre critic Alfred Kerr saw nothing particularly original in Kurt Weill’s stage music, claiming that Weill enticed the audience with older, existing, reliable melodies behind a mask of jazz.Footnote 30 Yet Adorno was struck deeply by Weill’s achievement. After hearing Die Dreigroschenoper for the first time, he wrote that it seemed to him ‘the most important event of the musical theatre since Berg’s Wozzeck’.Footnote 31

This is not the place to speak of the merits of the text, but rather of the grey, smoky songs that remain walled up behind a few tones, of the ballads, smoking greyly and bawled out, echoing the amorphous, urgent, rebellious call of the proletariat. At first, this music seems distant from me, in that it draws consequences from nothing that registers as current musical material. Instead, it seeks to work through the transformation of old shrunken material. Yet, with Weill, such an effect is so strikingly and originally accomplished that, faced with this fact, we are struck dumb.Footnote 32

Nevertheless, as The 3-Penny Opera, it lasted for only twelve performances at the Empire Theatre, New York, in 1933.

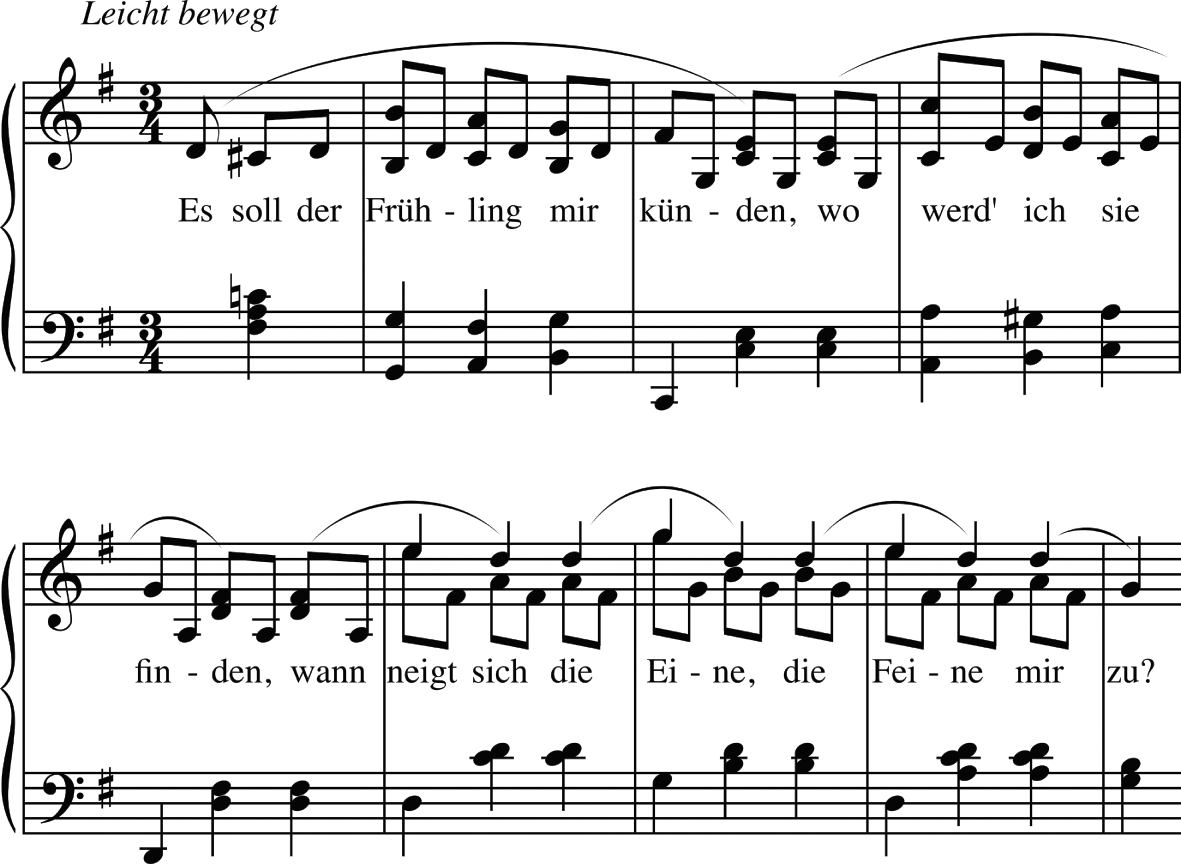

A Mixture of Styles

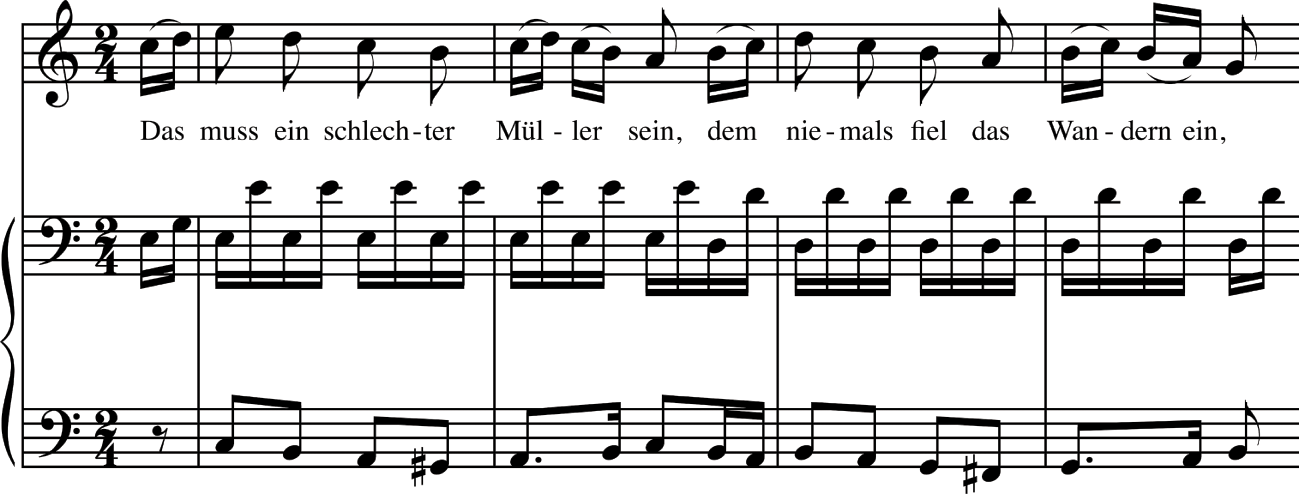

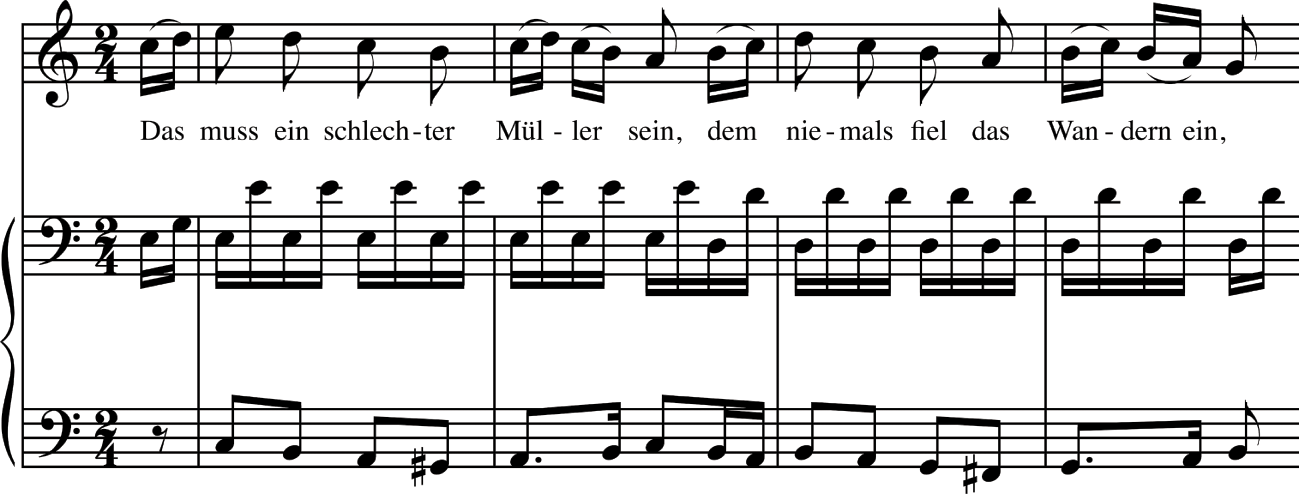

There was delight in mixing musical styles, and it is common to find Austro-German, Hungarian, and American styles in the same piece. This mixture is rarely suggestive of any cultural clash: Künneke’s Der Vetter aus Dingsda (1921), set in the Netherlands, covered a gamut of styles, from the valse boston (‘Strahlender Mond’) to the ragtime two-step (‘Überleg’ Dir’s’ and ‘Mann, o Mann’), the tango (‘Weißt du noch?’) and the fox trot (‘Batavia’). Also present was the Schubertian lyricism that had proved so appealing in Berté’s Das Dreimäderlhaus, which Künneke had spent many evenings conducting at the Friedrich Wilhelmstädtisches Theater in 1916. The biggest hit of Der Vetter was ‘Ich bin nur ein armer Wandergesell’ (in London ‘I’m Only a Strolling Vagabond’, in New York ‘I’m Only a Pilgrim’). The middle section of this song could easily be exchanged with bars 9–12 of ‘Das Wandern ist der Müllers Lust’ from Schubert’s Die Schöne Müllerin, such is the stylistic affinity (Examples 1.14 and 1.15).

Example 1.14 ‘Ich bin nur ein armer Wandergesell’.

Example 1.15 ‘Das Wandern ist des Müllers Lust’.

Kálmán’s Die Herzogin von Chicago (1928) is unusual in containing a stylistic conflict that creates a reaction among its dramatis personae, because it pits the csárdás and waltz against the Charleston and fox trot, and, in so doing, symbolizes a broader cultural struggle between national tradition and cosmopolitan fashion.Footnote 33 Die Herzogin illustrates a change in the representation of America on the German stage. Kálmán had benefitted from advice on American style given to him by Herbert Stothart when composing Golden Dawn for Broadway in the previous year.Footnote 34 There had been little in the way of an American idiom in Fall’s Die Dollarprinzessin (1907), setting aside the interpolated numbers Jerome Kern composed for the Broadway version. The quartet describing dollar princesses, for example, had a waltz refrain. In contrast, the Duchess of Chicago’s song, ‘Wie sich’s schickt’, distinctly evokes America – even if it is a fox trot without syncopation – as a consequence of the occasional use of blue notes, especially in the accompaniment. She sings about travelling through Europe, cheque book in hand, buying anything she fancies, because she is from Chicago, where only the dollar rules. The musical conflict between csárdás and Charleston in this operetta did not have the same resonance in the USA as in Europe, and that may have been the cause of its lack of success. Alternatively, it may have been owing to its containing sharper satire than Die Dollarprinzessin. The Shubert brothers decided not to stage it on Broadway, after a disappointing reception at try-out performances in 1929.

Brecht and Weill went a step further in Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny) of 1930, by ensuring that satire permeated the music as well the words. An illustration is the ‘Alabama Song’, with its sour dissonances and self-consciously emotional lyricism, which capture the Gestus that Brecht believed necessary to ensure an audience would remain critically alert, rather than succumb to theatrical illusionism. There was no American staging of this work until an off-Broadway production in 1970. Paul Abraham’s operettas often relied heavily on American musical styles, but did so for fashionable appeal, rather than satirical purpose. The song ‘My Golden Baby’ from Die Blume von Hawaii (1931), for example, resembles a popular dance-band number (and, indeed, became one), even though Alfred Grünwald and Fritz Löhner-Beda’s libretto for this operetta touched on political issues relating to the American occupation of Hawaii in the late nineteenth century. Satire disappeared from Kálmán’s work, and his last operetta Arizona Lady (libretto by Alfred Grünwald and Gustav Beer, music completed by his son Charles in 1954) contains a song, ‘Arizona’ that could easily be regarded as a tribute to the Rodgers and Hammerstein song ‘Oklahoma!’ from the 1943 musical of that name. It undoubtedly has musical features in common when the chorus sings in praise of Arizona.

Orchestration and Orchestrators

Reviewing a performance of Das Land des Lächelns by Frankfurt Opera in 1930, Theodor Adorno commented:

It embraces the pathos of Puccini’s Turandot, which already belongs to operetta, and even its enthusiasm with rhapsodic-melodic arches comes from Italy. The admired orchestration proves on closer listening to be rather poor.Footnote 35

Adorno was seizing an opportunity to take a shot at Lehár’s orchestral imagination, knowing that his skills in this domain had been praised as exceptional in the 1920s, when he was often called the Puccini of operetta.Footnote 36 Lehár, who was actually on friendly terms with Puccini, demonstrates consistent orchestral skill in his operettas – for example, in the striking writing for wind instruments in Eva (1911), or the delicate effects achieved in the duet ‘Fern wie aus vergangen Tagen’ from Wo die Lerche singt (1918). Each of his operettas has its own characteristic orchestral sound, and his expertise as a violinist informs the scores of Zigeunerliebe (1910) and Paganini (1925). His orchestration frequently plays a role in the drama. As an example, Stefan Frey cites the trilling clarinet that ironically questions Valencienne’s assertion in Act 1, No. 2 of Die lustige Witwe that she is a respectable wife.Footnote 37 Lehár’s imaginative scoring is heard in his tone painting during the first number of Zigeunerliebe, which Frey describes as a dialogue with the forces of nature.Footnote 38 Contemporary critics praised the tunefulness of Austrian and German operettas, but they also, especially when listening to Lehár, appreciated the skill with which they were scored. Reviews in The Times speak of the ‘grace and vivacity’ of the orchestration of The Count of Luxembourg, and the care taken with that of Gipsy Love.Footnote 39 A critic in the New York Times, in contrast, expresses unhappiness at Leo Fall’s orchestration in The Girl in the Train, accusing the composer of being too influenced by Wagner. He likens the opening to that of the second act of Die Walküre, and complains of an excess of percussion and trombones, even if, sometimes, ‘dear old Vienna calls him away from Bayreuth, and he bursts into a spontaneous waltz rhythm’.Footnote 40

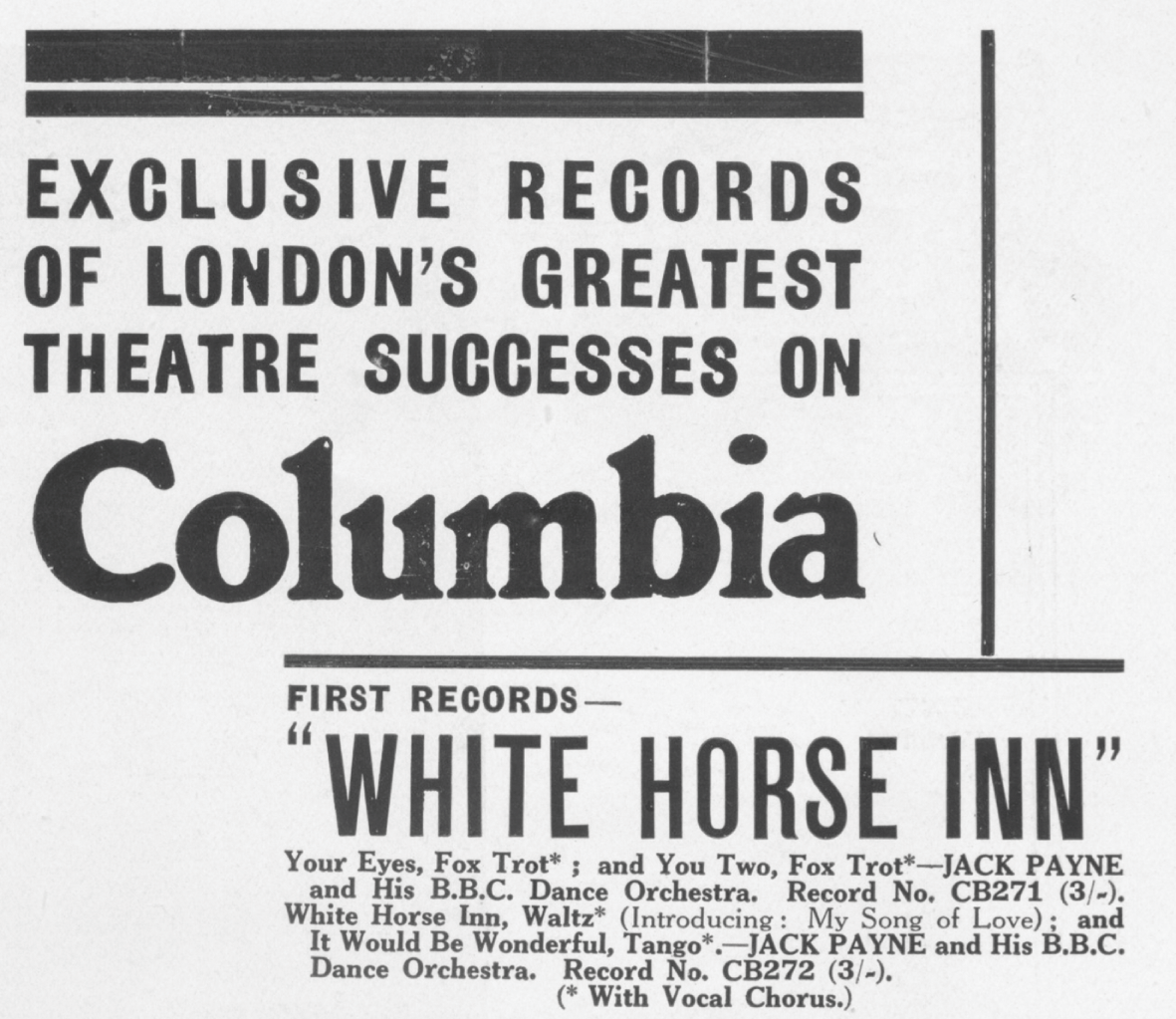

Most operetta composers in Vienna and Berlin were happy to have the help of orchestrators. Orchestrators were also on hand for New York productions. Vienna-born Hans Spialek was prominent among them and was credited with the orchestration of the Broadway White Horse Inn. He was also responsible for the orchestration of Kálmán’s Marinka, produced at the Winter Garden in 1945. Unlike opera, operettas were likely to be given updated orchestration when revived.

Oscar Straus was a fine orchestrator: an early example of his ability to characterize in orchestral sound is heard in the piquant scoring of the duet ‘Piccolo! Piccolo! Tsin, tsin, tsin’ in Ein Walzertraum. Nevertheless, he began to look for help with orchestration in the 1920s, and when his Three Waltzes was produced at the Majestic in 1937, Conrad Salinger, Hilding Anderson, Don Walker, and others were responsible for its re-orchestration.Footnote 41 Lehár found collaboration with orchestrators unthinkable, even if that meant his turning up with complete parts only at the dress rehearsal.Footnote 42 He argued that he could develop and perfect his imagination and shape his own musical ideas more effectively than anyone else.Footnote 43 All the same, he was unable, once rights had been purchased, to prevent re-orchestration. Sometimes this meant changes were made for a reduced orchestra, and sometimes it went further, as in Frederika (1937), the Broadway version of Friederike, which was re-orchestrated by Hilding Anderson and William Challis. Kálmán did his own orchestration, with the exception of Golden Dawn and Marinka, and Weill, too, took full control of orchestrating his work, whether in Berlin or New York. Künneke, another operetta composer skilled in orchestral technique, believed a composer needed to understand in the smallest detail the individuality and technical possibilities of every instrument of the orchestra. For him, orchestral colour was as important to a composer as pigment to a painter.

The score is as much a part of composition as is the colour scheme in the creation of a painting. Nobody would call someone the creator of an image, who merely determined the rough outlines; and it is no different with music. Whoever wants to call a work his own intellectual product must also write the score.Footnote 44

According to a report in the Berliner Tageblatt, Paul Abraham orchestrated his works himself.Footnote 45 Yet he did not always seem averse to collaboration. Egon Kemény, for example, was given the job of arranging a score in which Abraham specified instrumental groups but not the exact notes each instrument was to play.Footnote 46 This resembled contemporary Broadway practice.

The size of operetta orchestras had grown over the years. The first version of Offenbach’s Orphée aux enfers (1858) had two flutes (both doubling piccolo), two clarinets, one bassoon, two horns, two cornets, two trombones, timpani, untuned percussion, and strings. It required, in all, around twenty-four players. Die Fledermaus (1874) had, in addition, two oboes, a second bassoon, two further horns, trumpets instead of cornets, an extra trombone, tuned and untuned percussion, and a harp. The string section would have contained more players, too. Therefore, some forty players were needed. Die lustige Witwe (1905) required a similar orchestra to Die Fledermaus but also called for a small on-stage band. In tandem with the growth in orchestra size, there was increasing diversity in instrumentation. Romberg included a saxophone in Blossom Time (1921). Künneke added a banjo to the score of Der Vetter aus Dingsda (1921), and a saxophone to that of Lady Hamilton (1926). Lehár asked for a saxophone in Der Zarewitsch (1927), as well as three balalaikas.

Im weißen Rössl (1930), given as White Horse Inn in London and New York, went well beyond any instrumental resources demanded hitherto. The original score (lost for many years) called for a pit orchestra of two flutes (doubling piccolos), oboe (doubling English horn), two clarinets, three alto saxophones, tenor saxophone, bassoon, three horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, two percussion players and a kit drummer, harp, banjo, guitar, celeste, and strings. In addition, several stage bands were needed: a zither trio (violin, zither, guitar), a jazz band (alternative line-ups are given, but one example comprises trumpet, saxophone, trombone, banjo, and drum kit), a steam boat band (piccolo, E♭ clarinet, B♭ clarinet, trumpet, tenor horn, trombone, and reduced drum kit), and a fire brigade band (E♭ clarinet, B♭ clarinet, two trumpets, two tenor horns, tuba, and reduced drum kit).Footnote 47

Although a full orchestral score is now available to the conductor of Im weißen Rössl, it was far more common before 1940 to find musical directors using piano-conductor scores.Footnote 48 These would be piano vocal scores with additional handwritten indications of instrumentation and instrumental solos. Figure 1.1 shows part of the conductor’s score of Blossom Time, with handwritten notation and indications of instruments. It is a copy, reproduced with a spirit duplicator, a machine that removed the necessity to hand-copy scores when several companies were putting on performances simultaneously. The Shubert Archive possesses five identical hardbound copies, which must date from 1923 at the earliest, because that is the year Wilhelm Ritzerfeld invented the spirit duplicator, with its distinctive lilac ink.

Figure 1.1 Excerpt from the Overture to Blossom Time in a copy of the piano-conductor score.

Music and Drama

Music may be an appendage to drama or may play a more active role. Musical variety is not present for its own sake in Der Vetter aus Dingsda; it is there to enrich specific dramatic scenes. Otto Schneidereit remarks that Künneke chose a rhythm for each musical number that helped to characterize the corresponding action.Footnote 49 Der Vetter has numbers, but they are part of a dramatic whole. Schneiderheit believes that Künneke was not usually so careful, because his focus was often on the music more than the drama. Nobody praised him, he says, for being a skilled and trained music dramatist.Footnote 50 Yet the way the waltz duet ‘Nicht Wahr, hier ist’s wie im Zauberreich’ is interrupted in the finale of Act 1, and the melodrama that follows, is clear evidence of musical-dramatic skill on Künneke’s part.

Lehár, too, was interested in dramatic wholes, and his employment of recurring melodic motives was a means of achieving large-scale coherence. In Eva, the title character’s song ‘War’ es auch nichts als ein Augenbick’ provides a melodic motive the recurs at significant points of the drama. Lehár was to give ever-increasing cohesion to his operettas via the use of motives. Frey discusses his use of the ‘O Mädchen, mein Mädchen’ motive in Friederike.Footnote 51 This song is more than a detachable Schlager; it is a source of important unifying material that adds to the drama and to the psychological representation of character. Giuditta is the most thematically organized of his operettas, its motives and melodic reminiscences contributing powerfully to the dramatic action. In its final scene, the harmony and orchestration make the reprise of the muted trumpet’s motive from ‘Meer von Liebe’ a strangely otherworldly reminiscence, a wistful evocation of the fairy-tale of which Octavio speaks. Lehár was not alone in conceiving methods for lending musical coherence to larger structures: Kálmán, for instance, makes use of leitmotifs in Die Bajadere.

Lehár’s through-composed second act finale of Der Graf von Luxemburg, in which motives and short reprises play a role, was an attempt to create a seamless flow of drama and musical numbers. This was lost in the London and New York productions, as a consequence of its revision from three acts to two. Lehár was not the only composer to find that efforts to embed a dramatic scene in music was overturned. Changes made to a scene can negate the intentions of the composer, even if the musical structure is unaltered. In the London version of Die Dollarprinzessin, Adrian Ross’s lyrics, unlike those of George Grossmith for the Broadway version, make no reference to typists in the opening chorus. As a consequence, although music of that chorus is unchanged, its semiotic import – its representation of clicking typewriters – is lost (Example 1.16).

Example 1.16 Typewriter chorus.

Structural changes were often made because there were different expectations of operatic productions when they transferred to Broadway or the West End. Oscar Straus pointed out some of the differences between London and Vienna productions to a journalist: ‘Your choruses are much bigger, and … you have many more songs than we are content with.’Footnote 52

Operetta was structured in acts, or sometimes just scenes (the usual format of revue), with musical numbers – songs, duets, ensembles, and so forth. Berlin operetta, as represented by Walter Kollo and Jean Gilbert, privileged songs over ensembles, and avoided complex finales. Frey points to the second-act finale as ‘normally the showpiece of every Viennese operetta’.Footnote 53 The finale of an act (typically the first or second) was normally the only place through-composition would be found. An exception is the second act of Lehár’s Endlich Allein (1914), which concludes with a protracted love duet that occupies over twenty pages of vocal score and includes ten changes of key signature. Lehár was already working towards an extended love duet with ‘Wenn zwei sich lieben’ in Der Rastelbinder (1902), which lasts over seven minutes in performance.

Another way in which cohesion could be brought to the whole, was by giving an operetta a particular character. That happened in the nineteenth century with the Gilbert and Sullivan comic operas (no one could mistake the music of The Gondoliers for that of The Mikado). Fall’s Der fidele Bauer of 1907 has a different sound character to Die Dollarprinzessin later the same year, and each of Künneke’s operettas has a different overall character. Andrew Lamb has argued, with reference to The Count of Luxembourg, that Lehár’s genius ‘lay not just in his ability to provide supremely popular melodies, nor in his rich command of orchestral colour’, but, more particularly, ‘in his ability to capture in musical terms the atmosphere of the romantic situations and the various passions of the characters’.Footnote 54 Characters in operetta are constructed not just by the words, but by the music as well.Footnote 55 In Die lustige Witwe, Danilo and Hanna (Sonia) are musically distinct from Camille and Valencienne (Natalie). Romantic lovers are also characterized differently from one operetta to another: Danilo and Hanna are distinct from Goethe and Friederike, who, in turn, are distinct from Sou Chong and Lisa in Das Land des Lächelns.

While Lehár was seeking greater overall cohesion through musical characterization and motivic connections, others, such as Kollo, were interested in the loose structures of vaudeville and revue. Writer-producer Erik Charell takes credit for creating revue operetta. His biggest triumph was Im weißen Rössl, in which Ralph Benatzky’s music was supplemented by that of Robert Stolz, Bruno Granichstaedten, Robert Gilbert, and an unacknowledged Eduard Künneke, who composed scene music, arranged choruses, and even gave a hand with the orchestration.Footnote 56 Revue operetta tended to be multi-authored from the start – necessitated by the tight production schedule – and is therefore to be distinguished from the practice of interpolating numbers.

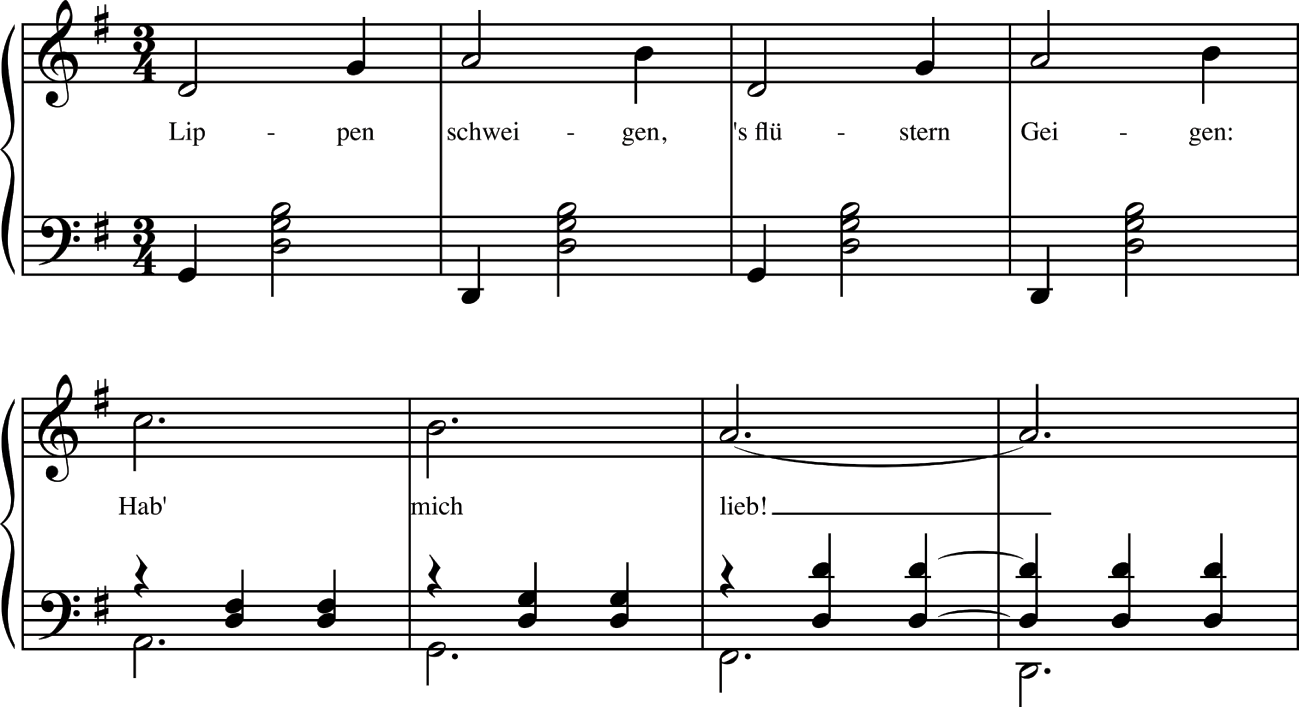

Lehár had long been aware that music on its own could function as psychological drama. It is the music that reveals the secret emotions of Danilo and Hanna while their lips remain silent. Heike Quissek comments that it is in their waltz duet, ‘Lippen schweigen’, that the latent psychologization of these figures reaches its climax.Footnote 57 The few words it contains is significant, because it is not the lyrics but music that characterizes them: lips may be silent but their emotions unfold to the steps of the waltz.Footnote 58

The musical continuity of the Act 1 finale of Künneke’s Der Vetter aus Dingsda is an example of how music can function as part of dramatic and psychological characterization. There is recitative and arioso in this operetta, not just songs and ensembles. It also possesses an unusual intimacy because it is cast on small scale. Another composer alert to characterization and the role of music in drama was Kálmán. Frey says of Gräfin Mariza, ‘every number characterizes the one who sings it’, and ‘every number develops from the situation’.Footnote 59 This takes precedence over what was conventional: for example, the tenor’s duet is with the soubrette, rather than the diva. A common way of characterizing a person is to use an obbligato instrument: for example, a rhapsodic solo violin accompanying a Gipsy’s singing.

While some operettas began to reduce spoken dialogue, others continued to include large quantities. Act 3 of Edmund Eysler’s Die goldene Meisterin (1927) contains around six minutes of music and over twenty minutes of dialogue. It is an example of an older ‘musical play’ type of operetta surviving on the German stage into the 1920s. The spoken word offers a simpler means of advancing the action than does music, which so often creates a pause in the drama. In what has become known as an ‘integrated musical’, musical numbers are designed to be a necessary part of the drama, meaning that a song cannot be omitted without damaging the drama or narrative. Integration was clearly a growing concern for some operetta composers (consider Lehár’s Friederike). The use of reprise (in German, Reminiszenz) can be an integrating device and an equivalent of analepsis (‘flashback’), or it can simply be a case of ‘here’s another chance to hear an attractive tune’. The employment of motivic connections, already discussed, was another technique contributing to large-scale integration.

In addition to conceiving an operetta as a whole, decisions about structure needed to be taken on a small scale. Here, the fashionable structures of popular song bore an influence, as can be seen in the adaptation of the bullfinch duet (‘Wer uns getraut’) from Johann Strauss’s Der Zigeunerbaron (1885) for the MGM film The Great Waltz (1938). Dimitri Tiomkin was responsible for the musical arrangement, and it was given fresh lyrics, ‘One Day When We Were Young’, by Oscar Hammerstein II. It was already fashionable in tempo because, unusually for its original date of composition, it was the slower type of waltz. The original, however, had been in verse and refrain form, the typical popular song structure of the later nineteenth century, but the later version was converted to AABA form, the typical structure of Tin Pan Alley songs. To achieve that, the original verse music was scrapped and the 16-bar refrain became the basis of the whole song. It was stated and repeated, then, after a new melodic passage added for the ‘B’ section, repeated again.

The perception that operetta creation had developed into a type of industrial production, encouraged ideas about preformed musical units assembled on conveyor belts. Adorno asserted, ‘the law that rules operetta lies in the objective force of banal, ready-made shapes’.Footnote 60 On the occasion of a revival of Die lustige Witwe by Frankfurt Opera in 1934, he claimed that Lehár’s work illustrated the turning point of the genre, before it slipped into unremitting decline:

Die lustige Witwe stands at the border: one of the last operettas that still has something to do with art, and one of the first to thoughtlessly renounce it. It doesn’t yet survive on sequences, but from melodic and rhythmic profiles – an interpolated jazz piece from today seemed paltry in this context. It has a certain individual attitude and is even tasteful in its lightly suggested Southern Slavish tone. It has a dramatic moment when Danilo dashes off to the strains of the Maxim song: this song, a singular monument to Frou-Frou’s world of love, preserved the faithful features of its epoch more than any current hit. Furthermore, Glawari’s romance [‘Vilja’], as sentimental as it is, allows you to listen, and there is absolutely no mistaking that it is not yet put together on a conveyor belt, but, rather, made by a human being.Footnote 61

In Adorno’s mind, Lehár and Kálmán had failed to realize their early promise through having succumbed to the demands of industrial methods of production. Writing of Die Herzogin von Chicago, he asserted: ‘One knows that the earlier Kálmán, in his commercial art manner, created much that was pretty and imaginative. Today there is nothing left of this; a composing template (Komposnierschablone) prevails that turns plagiarism and his own past into a system.’Footnote 62 Adorno invariably sees commercial music production as the replication of successful formats, and yet it is patently evident that commercial music undergoes changes in its structure and parameters (harmony, rhythm, timbre, and so forth) over any given period of time. The operettas of the 1920s and 1930s are not the same as those of the first two decades of the twentieth century, despite certain genre-related continuities.

Operettas on Historic Subjects

There were three main types of operetta content: the modern, the exotic, and the historic. The latter subdivided into those that had newly composed music (such as Madame Pompadour and Lady Hamilton) and those that contained reworked music by earlier composers (such as Das Dreimäderlhaus and Casanova). Some operettas with historic themes adopted elements of period style, as do Lehár’s Friederike (1928) and Kálmán’s Kaiserin Josephine (1936), both of which included gavottes.

Among operettas on historic topics containing reworkings of older music, one of the best received was Walzer aus Wien (1930). It loosely followed the career of Johann Strauss Jr and had music by him and his father, adapted by Erich Korngold and Julius Bittner. Some music is readily recognizable: for example, the song ‘With All My Heart’ is based on the waltz Künstlerleben, and the refrain of ‘Morning’ draws predictably on Morgenblätter. In other numbers, Korngold was drawn to elaborating musical motives and phrases from unfamiliar operettas by Strauss, building them into longer spans. In London, as Waltzes from Vienna in 1931, the music was further reworked by G. H. Clutsam and Herbert Griffiths. On Broadway, as The Great Waltz (1934), Frank Tours and Robert Russell Bennet took a hand in its arrangement.

Oscar Straus’s operetta Die drei Wälzer (1935), which told the tale of three generations of one family and their romances, also contained arrangements of the music of Strauss Sr and Strauss Jr, to which was added music by Straus himself for the modern day third act. Its premiere was in Zürich, but it went on to huge acclaim when it was produced in Paris, starring Yvonne Printemps, at the time of the World Exhibition of 1937. It then opened on Broadway but was not seen in London until March 1945 (its run of 189 performances coinciding with the final months of the Second World War). The three waltzes of the title appear one in each act: ‘Wien ist ein Liebeslied’ (Act 1), ‘Ich liebe das Leben’ (Act 2), and ‘Man sagt sich beim Abschied Adieu’ (Act 3).

Perhaps the most beloved of operettas on historic themes that also used historic music was Das Dreimäderlhaus (1916), for which Heinrich Berté adapted compositions by Schubert. Adorno wrote of this work: ‘It is no coincidence that just when the last chances of producing light music have shrunk, operetta glorifies the “creative” artist by stealing his tunes.’Footnote 63 To be fair, Berté had originally composed most of the music himself but had come under increasing pressure from Wilhelm Karczag to replace it with arrangements of Schubert before a production at the Raimund-Theater would be agreed.Footnote 64 In 1921, one critic thought that the time for jazz had passed, and greeted the production of Blossom Time, Sigmund Romberg’s American version of this operetta, with the words: ‘After jazz, what? They tried a new answer on Broadway last evening when “Blossom Time” was produced at the Ambassador.’Footnote 65 A comparative study of Das Dreimäderlhaus and its British and American adaptations features in Chapter 2.

The spectacular revue operetta Casanova (1928) contained music of Strauss Jr, arranged by Ralph Benatzky, and was thus odd in using historic music but not that of the period in which its title character lived. It was first produced by Erik Charell at the Großes Schauspielhaus, Berlin, and brought to the London Coliseum by Stoll in 1932. Another unusual case was Die Dubarry (1931), Paul Knepler and Ignaz Michael Welleminsky’s revision of Carl Millöcker’s Gräfin Dubarry of 1879. Knepler was historical operetta’s most skilful librettist; he had worked with Béla Jenbach on Paganini for Lehár (1925) and went on to collaborate with Arnim Robinson on Die drei Wälzer for Oscar Straus (1935). Millöcker’s operetta contained no historical music related to the period of the Comtesse du Barry, but his own music had acquired a historic character related to its date of composition. Therefore, in this case, the music was updated and elaborated by Theo Mackeben. Its English version, The Dubarry (1932), by Desmond Carter and Rowland Leigh, was a huge hit with the West End audience but ran less successfully on Broadway.

Die Fledermaus was twice ‘brought up to date’ for a modern audience on Broadway, as The Merry Countess and A Wonderful Night, in 1912 and 1929, respectively. Sometimes, the process of updating could change the fortunes of a previously unsuccessful operetta: Indigo und die vierzig Räuber, Strauss Jr’s first operetta, had not enjoyed much attention since its premiere in 1871, but its reworking by Ernst Reiterer as Tausendundeine Nacht in 1906 won full audience approbation.

Operettas on Exotic Subjects

While operettas with modern themes were increasingly characterized by syncopated rhythms in the 1920s, those with exotic themes were spiced up with augmented intervals, modal harmony, and ostinato rhythms. Hungary was often represented an exotic domain, with Gipsy music emphasized. It may be argued that some composers were Hungarian, but the question is of style and representation rather than the composer’s ethnicity. Thus, it is necessary to ask: ‘How Hungarian is Kálmán’s Hungarian style?’ Would Béla Bartók have considered it Hungarian? Consider ‘Höre ich Zigeunergeigen’ from Gräfin Mariza (1924). It uses the Dorian mode, but that mode was often selected to represent the mysteriously exotic, after Rimsky-Korsakov’s effective use of it for that purpose in his Scheherazade (1888). Choosing another example, how convincing is the Gipsy song ‘Ich bin ein Zigeunerkind’ in Lehár’s Zigeunerliebe? Neither Kálmán nor Lehár were Gipsies, but, equally, neither had been immersed in Viennese culture before becoming purveyors of ‘authentic’ Viennese style. It may be that Gipsy culture suggested ethnic community, whereas Vienna suggested cosmopolitanism.

Lehár used different dance rhythms to characterize a modern Western Europe (Paris) and an Ottoman Eastern Europe (Pontevedro) in Die lustige Witwe.Footnote 66 The cultural clash is less East and West, however, than that of the traditional rural and the modern city. The Viennese audience, with its mixed ethnicity, no doubt identified with urban modernity, while retaining a certain degree of nostalgia for rural tradition, but this was an operetta that broke with the typical emphasis on Vienna, and its wine, women, and song. Stan Czech, in his Lehár biography, sees in it the birth of a new type of operetta, one that heralded a revolution in dramatic content, musical style, and orchestral technique.Footnote 67

Operetta often employed signifiers of ‘national style’ as colour. Frey describes the Orientalism in both the music and libretto of Fall’s The Rose of Stamboul as merely decorative.Footnote 68 Fall had not previously tried his hand at Oriental colouring of his music, and applies it inconsistently here. It is heard immediately in the drone bass and Lydian modal melody of the prelude. It emerges from time to time elsewhere but is not particularly noticeable in Achmed Bey’s big solo ‘O Rose von Stambul, nur Du allein’. Achmed’s ‘Ihr stillen süßen Frauen’ has more of the Spanish seguidilla than the Orient about it, and exoticism disappears entirely for ‘Ein Walzer muß es sein’. One might imagine some ‘Oriental’ eroticism would reappear for the Act 3 ‘Schnucki’ duet (‘lovey-dovey’ on Broadway), but Fall can handle seductive comedy without it.

Lehár provides a ‘Russian’ score for Der Zarewitsch and ‘Chinese’ score for Das Land des Lächelns, but this merely emphasizes the constructed character of national identification. Representation of the foreign in operetta can also have an ironic tone, as Volker Klotz has flagged up in discussing the Batavia septet in Der Vetter aus Dingsda.Footnote 69 Despite the exotic chords and slithering bass notes, the narration, here, is a fiction, and, what is more, references to a gnu, wildebeest, and kangaroo in the lyrics seem designed to make this obvious (Batavia was a former name of Jakarta in Indonesia). Then, there is the ‘jazz’ style that may connote place, but without necessarily connoting a nation or even a time period. The on-stage jazz band, the White Horse Inn Syncopaters, raises interesting questions. How does this work, when the piece is notionally set in the period before the death of the Emperor Franz Joseph? Is the use of jazz dance styles in White Horse Inn no stranger than the anachronistic dance styles in Strauss’s Der lustige Krieg (1881, but set in 1730), or Millöcker’s Der Bettelstudent (1882, but set in 1704)?

The operetta that comes closest to offering an ironic critique of musical Orientalism is Kálmán’s Die Bajadere. The representation of ethnic identity is problematized in this piece because a young prince from Lahore has fallen in love not with a Hindu dancer, as he believes, but with a French singer who is merely playing the role of a bayadere on the Parisian stage.Footnote 70 Kálmán’s music is more Hungarian in character than Indian (just as it is more Hungarian than African in Golden Dawn). Even its shimmy has something suggestive of Hungary or, perhaps, Klezmer about it. When an ironic mood is not evoked, the general tendency of operetta exoticism is to offer little more than spectacular scenes and extraordinary sounds. Since this cannot be maintained for long periods, the exoticism is usually applied inconsistently; it is a dressing-up that comes on and off during the course of the musical drama. ‘Dein ist mein ganzes Herz’, the best-known song of Lehar’s Das Land des Lächelns is not in the least exotic; yet, elsewhere, the singer, Sou Chong, is given exotic signifiers. The melismas on ‘ah’ in his ‘Von Apfelblüten einen Kranz’ are indebted to Orientalist representation – one has only to think of the song about the jeune Indou (the ‘Bell Song’) in Léo Delibes’s Lakmé (1883).

Operetta of the twentieth century does not fail to recognize the complexities of ethnic identities: a hit song from Paul Abraham’s Viktoria und ihr Husar, ‘Meine Mama war aus Yokohama – aus Paris war der Papa’, prompts the question, do you necessarily need to choose to identify with either East or West if you are half Japanese and half French? A French listener to French music may have an advantage over a Japanese listener in possessing greater familiarity with musical signs of ‘Frenchness’, but signs recognized by a cultural insider are no less arbitrary. There is not ‘something in the blood’ that allows people to represent their own ethnic group but not a different ethnic group. It is not a person’s genetic make-up, but, rather, cultural knowledge that enables such representation to work convincingly and win acceptance from those who are personally immersed in the culture represented.

Abraham had composed music for several operettas before achieving worldwide fame with Viktoria und ihr Husar, which included a variety of dance rhythms from around the world: fox trot (‘Mausi’), English waltz (‘Pardon, Madame’), csárdás (‘Nur ein Mädel’) as well as a pasodoble and tango. After its triumphant premiere as Viktória in Budapest, it reappeared in a German version as part of Leipzig’s ‘week of operetta’ in the summer of 1930 and went on to great success at the Metropol in Berlin and then in London. Abraham had studied at the Franz Liszt Music Academy and, initially, was committed to ‘serious’ music. However, when he discovered the money to be made by serving the lighter muse, he changed direction.Footnote 71 His first big hit was ‘Bin kein Hauptmann’ (I’m not a captain), a song written for the film Melodie des Herzens (1929), but he was already composing for the theatre. He eventually composed 16 operettas and contributed music to over 20 films.Footnote 72 Abraham was the subject of a newspaper article in 1931 headed ‘Berlin’s Stage Looks Toward America’. It was a reference both to the composer’s interest in American music and to his having chosen an American theme for his operetta Die Blume von Hawaii (Leipzig, 1931).Footnote 73 The jazz element had increased in this work compared to Viktoria, and when it was given a production in Budapest, Abraham took five American jazz musicians from Berlin with him.Footnote 74 His operetta of the following year, Ball im Savoy (given as Ball at the Savoy at Drury Lane in 1933), contained a remarkable mixture of American and Latin dance styles.

The sound world of Abraham’s operettas is distinct from the older Viennese operas, and his enthusiasm for incorporating styles from different countries marks his cosmopolitan disposition. He was not averse to including novel, sometimes parodic, syncopated dance routines in his work, examples being ‘Känguruh’ (Example 1.17) in Ball im Savoy and ‘Black-Walk’ in Roxy und ihr Wunderteam (1937).

Example 1.17 ‘Känguruh’.

Abraham’s eclecticism was seen by some in a negative light: an American reviewer of the premiere of Ball im Savoy at the Großes Schauspielhaus, Berlin, announced that Abraham was ‘at the moment the most popular operetta composer of Central Europe’, although it was difficult to identify a characteristic Abraham song: ‘He flits from style to style without leaving a mark.’Footnote 75 Abraham was not the first to be criticized on stylistic grounds: Kálmán’s Tatárjárás (which became Ein Herbstmanöver) was criticized for lack of stylistic unity: ‘From every single number sounds a different dialect.’Footnote 76

Sometimes the rural areas of a country can form an exotic contrast to the city, as occurs when the city dwellers meet the Wolfgangsee locals in White Horse Inn. ‘Im Salzkammergut’ is a Ländler, and also a humorous slap dance (Watschentanz). It demonstrates that country folk have their own ways of enjoying themselves. Dialect is used in this song, for instance ‘kann i net’ instead of ‘kann ich nicht’, and the words ‘da kann man gut lustig sein’ (as Giesecke the Berliner sings them) are sung by Josepha and the locals as either ‘da kamer gut lustig sein’ or ‘da kama gut’ (no doubt because of the humorous rhyming with ‘Salzkammergut’).Footnote 77

America was perceived by some European critics as a kind of ‘vulgar’ Other, rather than ethnic Other. In Paganini, one London critic was beginning to detect that Lehár was writing ‘music in two kinds’, part Viennese and part American. He declared that Tauber’s song ‘Girls Were Made to Love and Kiss’ would give less pleasure than some other numbers to the conservative members of the audience: ‘there is a moan in it from across the Atlantic that will not compensate them for the rhythm of Vienna’. Then, allowing us to recognize that the ‘conservative’ are those in the expensive stalls (those possessing both money and good taste), the critic continued, ‘but the circles and gallery at the Lyceum could not have too much of it and Herr Tauber was tumultuously invited to “plug” it again and again’.Footnote 78 Note the term ‘plug’, which was associated with the brash commercial marketing of New York’s Tin Pan Alley.

Musical Emulation and Cross-Fertilization

I conclude with a few words on the mutual influence that can be perceived on the stages of Berlin, London, New York, and Vienna. European composers were seeking opportunities in New York at the end of the nineteenth century and beginning of the twentieth. Gustave Kerker, who was one of the first to make a success with operetta in New York, was German, but had lived in America since childhood. His The Belle of New York had a disappointing run at the Casino in 1897, but created a major impact on London theatre the following year. Victor Herbert was Irish born, but, before moving to the USA in 1886, he had acquired extensive experience of music in continental Europe and played cello in the Strauss Orchestra during 1880–81. Rudolf Friml was Czech and was in his twenties when he moved to the USA in 1906. Sigmund Romberg (born Siegmund Rosenberg) was of Austro-Hungarian Jewish heritage and also in his twenties when he moved to the USA in 1909.

Some composers of German operetta purposely adopted American elements, but at other times the influence from Broadway crept into the music in a less conscious way.Footnote 79 It seems likely that Azuri’s Dance, ‘Soft as a Pigeon Lights upon the Sand’, from Act 1 of Romberg’s The Desert Song, was lurking somewhere in Lehár’s mind when he wrote the final scene of Giuditta. However, it appears equally likely that ‘Mädel fein, Mädel klein’ from Der Graf von Luxemburg was in Romberg’s mind when he composed ‘Just We Two’ for The Student Prince. Librettists were not immune to unconscious reminiscence, either: the duet for Gonda and the President in Die geschiedene Frau, contains the lines ‘Then she goes to the left / And he goes to the right’, which are echoed in Angèle and René’s duet in Der Graf von Luxemburg. A memory of popular tunes can lurk in the unconscious of a composer and be recollected unintentionally. The tune of ‘Ich bin dein Untertan’ in Fall’s Madame Pompadour (1922) sounds remarkably similar in places to that of ‘Ein Glaserl Wein’ from Kálmán’s Das Hollandweibchen (1920). ‘Warum bin ich verliebt in dich’ in Abraham’s Ball im Savoy resembles ‘Das Leben wirklich spaßig ist’ in Georg Jarno’s Die Försterchristl. These similarities are no doubt the result of unconscious processes, and stand apart from deliberate quotation, such as that of the ‘fate motive’ from Bizet’s Carmen in the duet ‘Josef, ach Josef, was bist du so keusch?’ sung by Madame Pompadour and Calicot. The quotation is consciously employed, with a degree of humour, to characterize Pompadour as a femme fatale (see the final bars of Example 1.18).

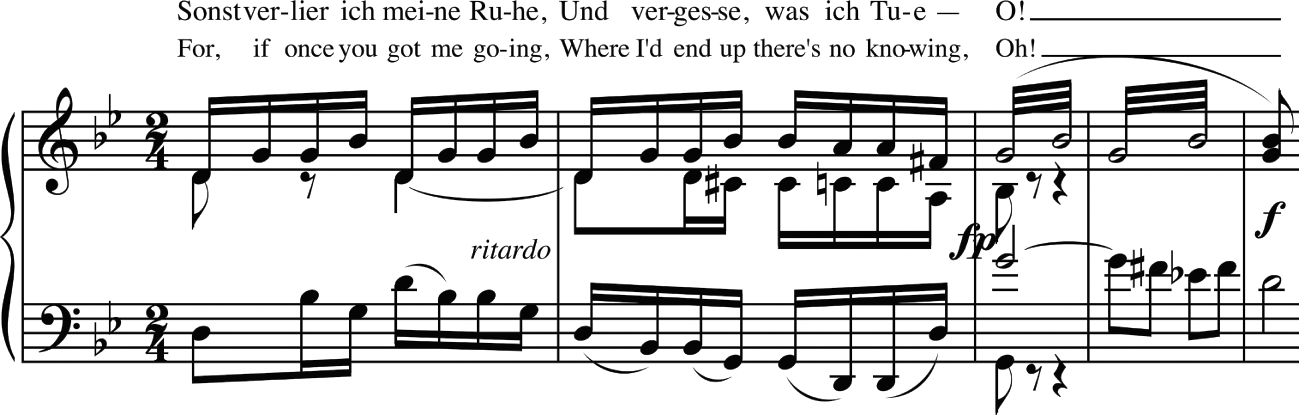

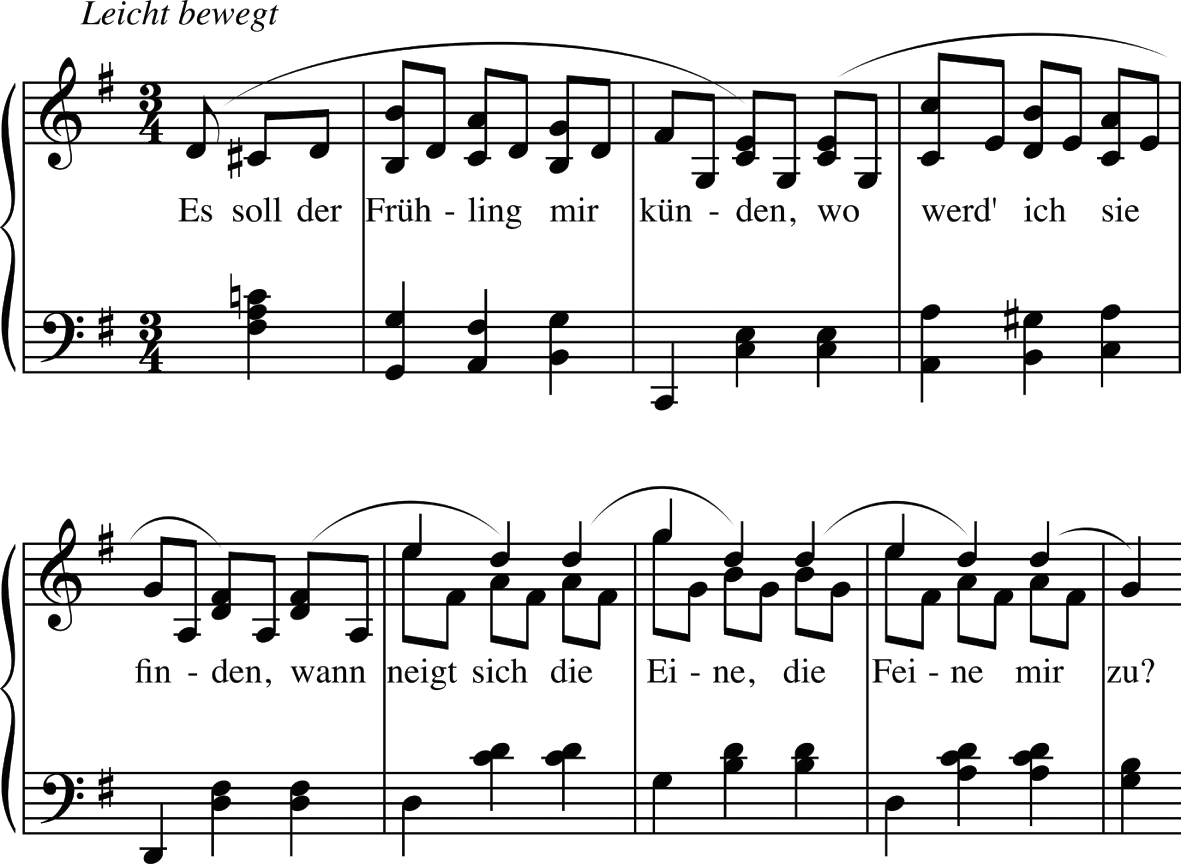

Composers of British musical comedy were not averse to taking note of the techniques of German operetta composers, and, although they sometimes failed to equal the sensual harmony, the melodic style was easier to imitate. ‘Love Will Find a Way’, the waltz hit in Fraser-Simson’s Maid of the Mountains (1917), bases itself on the Merry Widow waltz by doubling each of the first few notes of Lehár’s melody (Examples 1.19 and 1.20). Note that it is Lehár’s characteristic tempo of valse moderato.

Example 1.19 ‘Lippen schweigen’.

Example 1.20 ‘Love Will Find a Way’.

In the late 1920s and 1930s, it was Noël Coward and Ivor Novello who rose to the operetta challenge in London. When Coward composed his first operetta, Bitter Sweet (1929), he wanted Evelyn Laye, known for her roles in continental European operetta, to play the lead role of Sari (she did so on Broadway, but Peggy Wood was Sari in London). In Operette (1938), he composed specifically for the Berlin operetta star Fritzi Massary, who played Liesl Haren.

This chapter investigates the various ways in which operettas were changed as they transferred from one social-cultural context to another. The term ‘adaptation’ generally refers to remediation – a reworking from one medium to another – but the cultural transfer of operettas more commonly involved the creation of new versions of works already designed for the stage (the adaptation of stage operettas as films is discussed in Chapter 3). This is not to deny that differences could be considerable, but, most of the time, changes were made to accommodate differing cultural experiences and expectations, which is why the term ‘transcreation’ is useful. It was never a case of merely translating the German book and lyrics; it was necessary to capture the cultural meanings and emotional nuances that resist direct translation, enabling them to be recognized in a new context.

Developed as a concept in advertising in the 1970s, transcreation has become associated with the creative transformation of images and modification of storylines in computer and video games as part of a strategy to reach different cultural markets.Footnote 1 In the cultural transfer of operetta, transcreation encompassed scene and costume design as well as interpolated numbers, character modifications, and structural changes. None of this is aptly described as translation, yet to use the word ‘transformation’ would be to go too far. The different versions of stage works often remain fundamentally the same.

Linda Hutcheon has stressed that cultural and social meaning cannot be conveyed effectively by merely translating words.Footnote 2 This, too, can be linked to the idea of transcreation. In some cases, what is at stake is translation in the sense in which Nicolas Bourriaud has called for creative artists to translate the meaning of a cultural artifact for an ‘outsider’. For Bourriaud, translation is at the heart of an important ethical and aesthetic struggle, that of ‘rejecting any source code that would seek to assign a single origin to works and texts’.Footnote 3 Arguments advanced in poststructuralism and deconstruction have made it difficult to claim authority for an ‘original’: the original, itself, exists in an intertextual web. Fidelity discourse has been abandoned by adaptation theorists, although comparison of similarities and differences remains of interest.Footnote 4

The ease with which cross-cultural translation could be achieved illustrates the commonalities of twentieth-century metropolitan experience, and the practices of translation and transcreation are significant for operetta’s character as a cosmopolitan genre. Popular forms of entertainment often carry more conspicuous traces of the cultural context in which they were created than do high-status art forms. Artistic respect for opera ensured that it was seldom reworked to fit a changed cultural environment to the same extent as operetta. Opera had often been subject to adaptations in its earlier days, but that diminished after the polarization of ideas of art and entertainment from the middle of the nineteenth century on, when adaptation came to be seen as demeaning. Even in the most provocative Regietheater, alterations to an opera’s libretto are rare, and revisions to its music even rarer. Moreover, operas are almost always given in the original language. Operettas, on the other hand, are subjected to changes in language, structure, and scene, and often have added music. Reginald Arkell, who, with A. P. Herbert, was responsible for the book and lyrics of the West End production of Paganini in 1937, was taken aback when its composer, Lehár, and its lead singer, Richard Tauber, opposed them strongly. Theatre publicist MacQueen-Pope shared Arkell’s consternation:

in those days, when the rights of a continental success were secured for London, little attention was paid to any clauses in the contract calling for purity of performance and strict adherence to the story, and requiring that no numbers should be interpolated.Footnote 5

The creation of new versions offered opportunities for originality. Such a task did not have to be tied to ideas of fidelity and respect for the former text; it could be a reimagining or a reinterpretation.

It is not uncommon to find that the libretto of an operetta is already an adaptation of a novel, poem, or stage play. The Merry Widow, for example, was an English version of Die lustige Witwe, which was already a musical adaptation of Henri Meilhac’s play L’Attaché d’ambassade, performed at the Théâtre du Vaudeville, Paris, in 1861.Footnote 6 When Ben Travers, now best known as the author of the Aldwych farce Rookery Nook (1926), authored the book and lyrics of The Three Graces for the Empire Theatre in 1924, he reworked Lehár’s Der Libellentanz (1923), which was already a reworking by Alfred Maria Willner of Carlo Lombardi’s new libretto to Lehár’s Der Sternglucker (1916), given in Milan as La danza delle libellule (1922). Other works that were much revised, if not to similar extent, were Lehár’s Endlich Allein (becoming Schön ist die Welt) and Der gelbe Jacke (becoming Das Land des Lächelns), Kálmán’s Der gute Kamerad (becoming Gold gab ich für Eisen), and Fall’s Der Rebell (becoming Der liebe Augustin). It is better, perhaps, to speak of prior versions than original versions, to relinquish searching for an original, and accept that different versions exist, each of which may contain something of unique artistic value. When Eduard Künneke visited his birthplace, Emmerich am Rhein, in later life, he signed the town guest book and appended a musical quotation, the beginning of ‘Ich bin nur ein armer Wandergesell’ from Der Vetter aus Dingsda. However, Künneke also added the title and song lyrics from its London production (The Cousin from Nowhere, ‘I’m Only a Strolling Vagabond’).Footnote 7 It would appear he identified with both versions.

The remapping of a scene onto a locally known place that would conjure up similar associations to those that were culturally familiar to the former audience was part of transcreation. It was an important means of reproducing similar pleasure and understanding. The fact that such substitutions were easily made points to a certain equivalence in the experience of urban environments. In The Girl on the Film, James T. Tanner’s West End version of Filmzauber, Adrian Ross’s lyrics have Freddy and Max singing about walking down Bond Street, rather than Unter den Linden. The transcreation of Filmzauber also had to deal with differing sociocultural nuances. The German version featured the character Euphemia Breitsprecher, whom Tobias Becker argues would have been immediately recognized in Berlin as a caricature of the social reformer who believed films posed moral danger and should be restricted to serving educational purposes.Footnote 8 Tanner exchanges her for a film enthusiast and former actor, Euphemia Knox. It is an indication that the new medium of film met with less moral concern in London than it did in Berlin. If anxiety was felt in the UK, it was about the prospect of American films destabilizing the British social hierarchy with their democratic values.Footnote 9 The notion of the sinful metropolis was stressed in Berlin through the character Käsebier. His counterpart in London, Clutterbuck, is more concerned about foreign threats, especially invasion. Given that the date of Tanner’s version was 1913, the London audience would have linked such threats to Germany. Ostensibly, it concerns Napoleon, so the audience may have felt reassured that, since the once-feared invasion of England by Napoleon failed to materialize, a German invasion was equally unlikely. Both versions included the projection of a film in the final act. The Gaiety was obliged to obtain a cinema licence in order to do so.Footnote 10

The Broadway version of The Girl on the Film was almost identical to the West End version but became the subject of a historic plagiarism case in 1914, when an American court declared that another theatrical production, All Aboard, breached its copyright by depicting a French invasion in a similar manner. That offers a neat illustration of the distinction between legitimate reworking, following the formal acquisition of rights, and plagiarizing for an unrelated production.

There was one location, a country of mountains, brigands, and tyrants, that had many names but remained essentially the same. First introduced as Ruritania in Anthony Hope’s novel The Prisoner of Zenda (1894), it was a fictitious version of the Balkans that became better known by Western European and American audiences than the Balkans themselves. Ruritanian locations featured in many operettas from German, British, and American stages. The homeland of the merry widow was Pontevedro in the Balkans (a thinly disguised Montenegro, which had defaulted on a large debt to Austria at the end of the nineteenth century). It became Marsova in the English version of the operetta, Farsovia in the burlesque at Weber’s music hall, Monteblanco in the MGM silent film of 1925, and Marshova in MGM’s later film of 1934. Such place names served to conjure up romantic adventures in the wilder parts of Europe: Hugo Hirsch’s Toni has a plot involving the loss of a precious jewel from Mettopolachia, and the leading characters of Jean Gilbert’s Katja, the Dancer are ex-aristocrats of Koruja.

Sometimes a new version departed radically from its German stage version, but the fact that such adaptations usually affected only the scenes and dialogue indicates the lack of any sense of perplexity about musical style. The existing music may have been sometimes chopped about and re-orchestrated, but melody, harmony, and rhythm were seldom altered, although additional numbers were often interpolated. Basil Hood may have claimed that he made almost a new play out of The Count of Luxembourg,Footnote 11 but the music was still that of Lehár. Musical style in an operetta often appears to be independent of the setting. The mixture of styles in Künneke’s Der Vetter aus Dingsda, which included transcultural modern styles such as the valse boston, tango, and fox trot, hardly seems designed to indicate a location in the Netherlands. Indeed, the New York version shifted continents for an American Civil War setting.

Few would argue that a musically unsatisfying opera or operetta has survived in the repertoire owing to a first-rate libretto. Yet it is not uncommon to hear of stage works surviving because of the quality of the music alone. A typical comment is found in a review of Caroline, the Broadway version of Der Vetter aus Dingsda: ‘Last night’s audience … seemed not much disturbed by the poorness of the book, and it is safe to assume that future audiences will also refuse to be bothered by it.’Footnote 12 Nevertheless, it had a short run, and most Anglophone revivals of this work have been of its London incarnation as The Cousin from Nowhere. It should also be emphasized that the German libretto was skilfully constructed (after Max Kempner-Hochstädt’s comedy) by Herman Haller, with lyrics by Rideamus (Fritz Oliven).Footnote 13