The subject of the following three chapters is the role of aristocratic intellectuals in shaping political discourse and social institutions in interwar Germany, Austria, as well as Europe at large. When constitutional changes in central Europe and revolutions in Russia announced that old elites, such as the aristocratic families, would lose power in a new society of equals, some representatives of these social groups curiously became highly sought-after public speakers. In the age when aristocratic families were imbued with a sense of ‘group disgrace’, the aristocratic intellectuals became strangely appealing as global authorities on all things related to European identity at large.

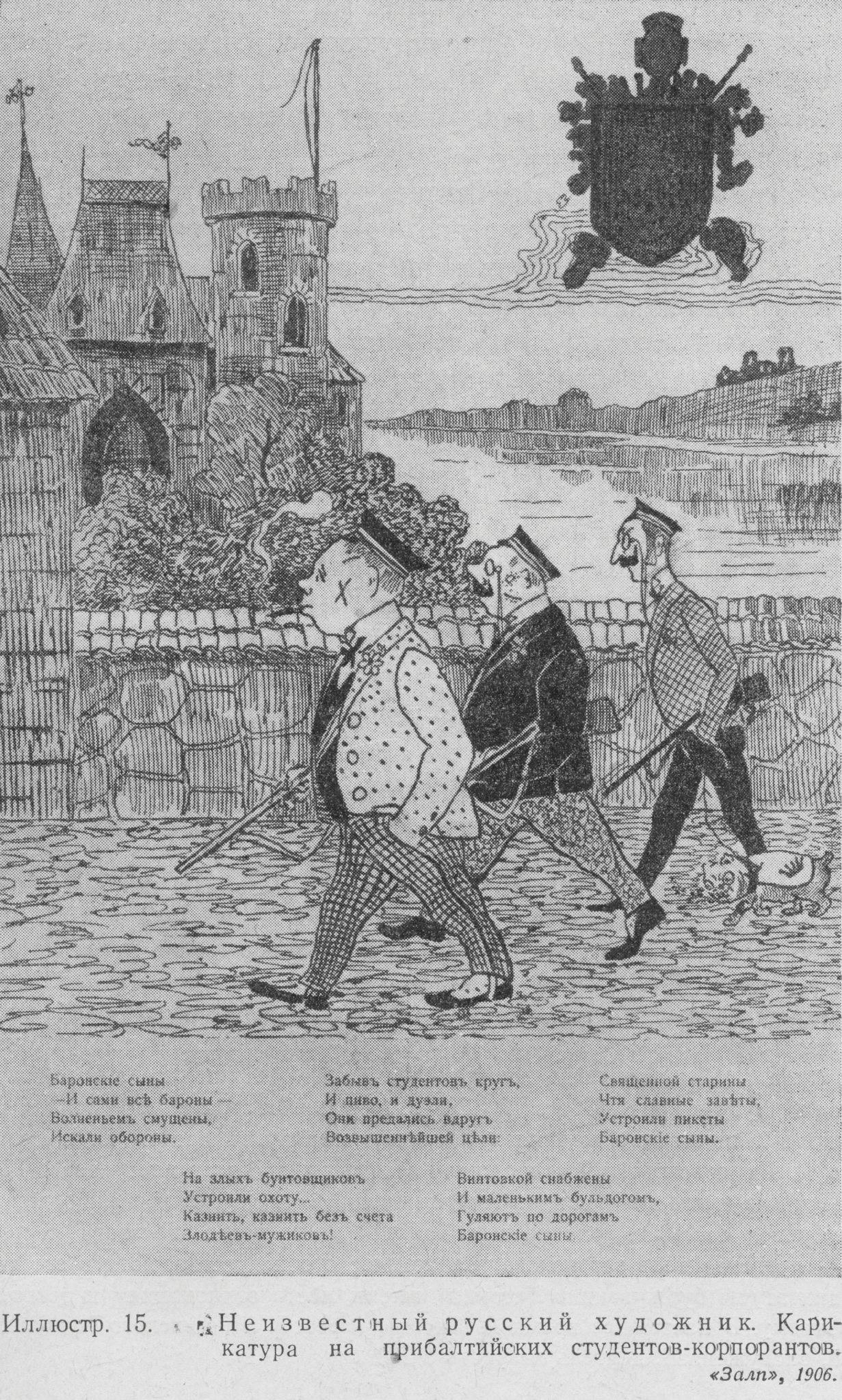

Part of this perception came from the celebrity of particular intellectuals who became Europe’s self-proclaimed ambassadors in encounters with non-Europeans. One contemporary called them ‘Germany’s new prophets’.Footnote 1 The photograph of one of these aristocratic celebrities, Count Hermann Keyserling, whom we last came across as a critic of the German war effort, shows him in such a role.

Characteristically, he is not in the centre of this image. The main protagonist is the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore, whose global popularity in the 1920s had much to do with the appeal of his verdict that Europe was in need of revival.Footnote 2 To the left of Tagore is Keyserling’s wife, Goedela Bismarck, the German Iron Chancellor’s granddaughter. The image represents not just a meeting of different worlds, but a joining of two kinds of continental celebrity: the Indian sage and the former Baltic Baron both speak of Europe’s future from the vantage point of aristocratic outsiders. Tagore, a Brahmin, observed Europe from an Indian perspective, while Keyserling, a Baltic aristocrat, considered himself above all nationalities due to his family’s relationship to more than one empire. He represented the kind of conversion of elites with inspiration from the Orient, which Max Weber had spoken about in his lecture of 1919. Keyserling’s celebrity in interwar high society, not only in Germany but, like Tagore’s, also in Britain and in Argentina, was the product of a particular kind of prestige, which was connected to the idea of European decline. This prestige of ‘former people’ is also the context in which the next chapter places Count Coudenhove-Kalergi’s initiative of a Pan-European federation.

‘My father dreamt of a Slavic kingdom under the reign of the Habsburgs. He dreamt of a monarchy of Austrians, Hungarians, and Slavs. […] In his will, I was named heir to his ideas. It was not for nothing that I had been christened Franz Ferdinand’.Footnote 1 These were the words of the protagonist of Joseph Roth’s novel, Capuchin Vault. It continued the story of the Trotta family, familiar to readers from Roth’s bestselling Radetzkymarsch in which the decline of Habsburg glory was explored from the perspective of three generations of a Slovenian family whose ennoblement dated back to one ancestor’s accidental role in saving the life of Franz Josef of Habsburg at the Battle of Solferino. In the sequel, written in the Netherlands during Roth’s exile from Vienna after the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany, Roth follows the decline of the von Trottas to the next two generations. Witnesses to the end of the Habsburg Empire in the revolution of 1918, Roth’s characters capture the atmosphere of loss that many former Habsburg subjects felt after the disintegration of the empire.

Returning from Siberia after having been taken prisoner on the eastern front, Franz Ferdinand von Trotta finds the Habsburg Empire in ruins. The horses in the Prater are dying of old age, as all the others ‘had been slaughtered, and people made sausages of them’. The back yards of the old army are filled with ‘parts of broken carriages’, which had previously served to transport such eminent personages as the ‘Tchirskys, the Pallavicinis, the Sternbergs, the Esterhazys, the Dietrichsteins, and the Trauttmannsdorffs’.Footnote 2 These old families were now threatened by entrepreneurial new elites from the Prussian North and the Baltic lands, represented by the character of Kurt von Stettenheim, ‘a mix between an international tennis star and a territorially fixed manor house owner, with a slight touch of Ocean Lloyd’.Footnote 3

Roth’s protagonist, Franz Ferdinand, gradually loses all he had: his wife, who runs off with a female artist; his mother, who dies on the day the revolution breaks out in Vienna in 1918; his money, lost to a Brandenburg entrepreneur; and, above all, ‘his’ monarchy. The proclamation of the idea of popular (self-)government, a Volksregierung, sounds to him like words of ‘a beloved woman’ telling him that ‘she did not need me in the least and could just sleep with herself’.Footnote 4 He still has his son, but chooses to send him off to live with a friend in Paris. Even though the line of the von Trottas survives for the time being, their lives appear to be meaningless in the absence of the Habsburgs. Alone, Franz Ferdinand von Trotta has only one consolation: he goes to the Capuchin Vault to pay tribute to the Habsburg emperors. But his mourning is troubled by the fact that his own father had been what he calls a ‘loyal deserter’, a critic of Emperor Franz Josef, the Habsburgs’ last successful emperor before the short final reign of Karl I, from 1916 to 1918. Observing a guard marching up and down in front of the vault, von Trotta, the ‘heir’, asks himself: ‘What is left here to guard? The sarcophagi? The memory? The history?’Footnote 5

These questions were Joseph Roth’s own; he drank himself to death only one year after the publication of this work. Another Habsburg author and a friend of Roth’s from Vienna, Stefan Zweig, followed suit in 1942, committing double suicide with his wife in Brazil, a country he had praised as the land of the future. The city where he died, Petropolis, was the place that, less than one hundred years earlier, had inspired Habsburg Archduke Maximilian to write one of his travel poems lamenting modernity: ‘For where the white man moves, his forest dries up,/ and his woman and child will be engulfed by a chain of sin’.Footnote 6 Like Roth, Zweig had contributed to the charisma of declining monarchs during his exile. One of his bestsellers was the biography of Marie Antoinette; her assassination in the wake of the French Revolution had provided an example of how to end the Old Regime, but also an inspiration to critics of revolutionary radicalism like Edmund Burke.Footnote 7 Like Roth, Zweig saw Prussia, Britain, and Russia as threats to the Habsburg Empire. As two Catholic dynasties, the Habsburgs and the Bourbons, were fighting their last battles against the ‘heretic people’ of an England ‘reaching for empire’, against the ‘Protestant Markgraviate of Brandenburg’ seeking an all-mighty kingdom, and ‘half-pagan Russia, preparing to stretch its sphere of power immeasurably’, they, who used to control most of Europe, grew ‘tired and weary’.Footnote 8 The symbolic victim who, for Zweig, stands in for the sympathetic view of the Old Regime is Marie Antoinette, married off in accordance with a practice that used to work for Europe’s old dynasties. Austria was still marrying, as the old proverb had it, but it was no longer happy. Marie Antoinette, Zweig claimed, was actually a woman of average character. There was neither anything heroic nor contemptible about her; she became heroic by virtue of dying a martyr’s death at the hands of the revolution. In fact, as émigrés like Zweig and Roth saw it, the Habsburg Empire as a whole, after 1918, had suffered the fate of Marie Antoinette. Another contemporary, Robert Musil, painted the empire’s most lasting satirical image as Kakania, an eminently average empire, tucked between Britain’s overseas dominions and Russia’s internal model of colonization.

Roth’s protagonist calls his father ‘Franz Josef’s loyal deserter’; he is the descendant of a man who deserted an imperial dynasty whose empire no longer exists. His inheritance was a utopian ideal of reform for an empire that was no longer recoverable. When the Social Democrats came to power in Austria in 1918, outlawing the Habsburgs and all noble titles, the reform ideas of a generation of Habsburg elites were marooned in a past world whose preservation was no longer politically viable. To understand the ideals of these 1920s and 1930s idealists, it is important to know, just as with Franz Ferdinand von Trotta, the ideas they had inherited.

In the interwar years, Vienna became the capital of the Pan-European movement, a supra-party lobbying group associated with Count Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi.Footnote 9 A graduate of the prestigious Theresianum school in Vienna where Austria’s imperial elite used to be trained, Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi found no empire to serve as a diplomat, which would have been his father’s natural choice for him. Instead, in 1922, he presented a suggestion for a Pan-European Union with Austria at its heart.Footnote 10 The proposed federation endorsed Europe’s economic unity, multicultural diversity, and the use of Africa as a resource colony. He was opposed both to the idea of a German–Austrian Union and to the idea of an accommodation of German nobles within the existing post-Versailles boundaries. Instead, he wanted a multi-ethnic empire under Austrian leadership, whose political form was not necessarily monarchical. In the Austrian, German, and Czech press, Coudenhove-Kalergi criticized both Austrian-German parochialism in Bohemia and Austria, and Czech nationalism.

Franz Josef’s loyal deserters and their heirs

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand and the collapse of the Habsburg Empire four years later created options for counterfactual thinking based on a dramatic break from a past whose continuity had been provided by the Habsburg dynasty. The heritage collection assembled by successive generations of Habsburgs, and the newly institutionalized form of the multinational museum created by Franz Ferdinand and his entourage, now themselves became specimen about the Habsburgs Habsburg artefacts as much as about their purported objects.

Among the ideological debris left behind were the utopian reform plans for a multinational empire. Utopic thinking is usually associated with progressivist historical epochs such as the Enlightenment. But, as we see here, utopic and Enlightenment thinking also have their place in the context of an otherwise melancholic discourse of decline. As Karl Popper put it, ‘the breakdown of the Austrian Empire and the aftermath of the First World War […] destroyed the world in which I had grown up’, making restoration and reform the two central tasks of his generation.Footnote 11 Imperialism imposed by an educated elite was seen by these liberal internationalists as a lesser evil than narrow-minded tribalism.Footnote 12

Like Roth’s Franz Ferdinand von Trotta, Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi was in many respects heir to his father’s ideas. He was critical of the conservative elements among the Habsburg aristocracy. The core conceit of the Paneuropa idea was the prospect of a United States of Europe to occupy a position of geopolitical balance with Asia, the Soviet Union, ‘Pan-America’ and the British Empire. It was a ‘programme of foreign policy’ which invited ‘leaders from all European parties’, ranging from conservatives to socialists, democrats, and liberals. Questions of the internal constitutions of states, he argued, were secondary to the overall goal of European unity, and thus Paneuropa welcomed ‘monarchies and republics, democracies and dictatorships’. It excluded only the ‘extreme nationalists’ and the ‘communists’, who were the ‘natural and irreconcilable enemies of the Paneuropa movement’.

Austria-Hungary provided many intellectual resources for rethinking social roles.Footnote 13 As diverse as any social network in that empire, the entourage of potential reformers around Franz Ferdinand, though most of them were elite administrators of high nobility, did not subscribe to any one ideology. Yet, in terms of the overall spectrum of political opinions in the empire, they shared a common interest – to promote the stability of a centrally organized empire rooted in loyalty to the Habsburg family. Preparing for his succession, Franz Ferdinand had surrounded himself with a circle that was to provide the foundation for his future reign. Many of these, he met during his world tour, and many had their main residence outside of the Austrian crown lands, especially in Bohemia (where Franz Ferdinand himself resided), Poland, Hungary, or Croatia. In the narrower circle of Franz Ferdinand’s supporters, we find such intellectuals as the moderate Baron Johann Heinrich von Chlumetzky, who, as a minister for agriculture in the imperial council in 1906, was instrumental in introducing such reforms as free elections with secret ballots.Footnote 14 Other supporters included the Romanian-born Baron Alfred von Koudelka, an admiral who had published travel notes on his journeys to America, the Croatian-born Emil Woinovich von Belobreska, and the Polish nobleman Theodor von Sosnosky, a historian.Footnote 15 Most of the aristocratic supporters had graduated from the Theresianum academy.

Among the non-noble reformers who put their hopes in Franz Ferdinand and were in turn supported by him was the Romanian scholar Aurel Popovici (1863–1917), who, in 1906, had published a proposal for the United States of Greater Austria in Leipzig.Footnote 16 In his model, the different ethno-cultural components of the Austro-Hungarian empire would be given greater national autonomy in matters of culture and education; in exchange, they would remain bound to Greater Austria by means of a federal union. In total, this union would comprise fifteen quasi-independent units defined by language. Each of the fifteen states in the union would receive votes in the legislative chamber of the imperial government.

Popovici’s theory was influenced by three models: Swiss federalism, as defended by the legal theorist Johann Caspar Bluntschli; the constitutional model of the United States; and Habsburg imperialism.Footnote 17 His explicit motivation in writing the work, aside from being a call to reject Magyarization, was to ensure the ‘future of the Habsburg empire’.Footnote 18 His book also exhibited an outspoken anti-Semitism, opening with a call to resist what he called the ‘Jewish liberal press’ represented by Viennese newspapers such as Neue Freie Presse and Die Zeit, but also provincial papers like the Bukowinaer Post. He demanded a new idea of a ‘greater Austrian state’, deliberately using the words ‘union’ and ‘empire’ interchangeably. While his anti-Magyar position, underlining pragmatic uses of nationalism for the sake of strengthening the central power of the Habsburg dynasty, was characteristic of Franz Fredinand’s entourage. Popovici combined his defence of multinational imperial reform with an anti-Semitic critique on the Jewish press of the Habsburg Empire.

By contrast, Coudenhove-Kalergi’s father, the Orientalist scholar and diplomat Heinrich Coudenhove-Kalergi, also a believer in Franz Ferdinand’s reforms, sought to deconstruct the foundations of Habsburg anti-Semitism. What anti-Semites call the ‘Jewish press’ he argued, was in fact the empire’s national press; the Jewish press, by contrast, remained largely unknown to the general reader. As a speaker of Hebrew, among allegedly eighteen other languages, Coudenhove was familiar with such publications as Esperanza (published in Smyrna), Haam, published in Kolomea, Habazaleth in Jerusalem, Hasaron in Lemberg, the Corriere Israelito from Trieste, and El progreso, published in Hebrew in Vienna. In mentioning these newspapers, Coudenhove reminded his readers that the project of Europe was rooted in a commitment to the Enlightenment, which had always built on a series of micro-Enlightenments in each community for itself, one of which was the Jewish Haskalah movement. Coudenhove was drawing on an already established discourse of multicultural patriotism in the Habsburg lands, represented by a writer one generation younger, the novelist Leopold Sacher-Masoch. In Don Juan of Colomea (1866), he ‘recovers’ a link between the distant frontier town of Colomea with the Roman Empire by claiming that the word was related to ‘Colonia’ and that the small town had grown ‘on the soil of a Roman plantation settlement’.Footnote 19 Coudenhove-Kalergi senior shared Sacher-Masoch’s philo-Semitism and philo-Slavism, as well as the desire to preserve the peculiarity of the multicultural empire against the opposing, nationalizing tendencies coming from Prussia.Footnote 20 Aside from promoting reform within the old nobility, one of the Enlightenments he was particularly interested in was the Jewish one, which began with the reforms initiated by Joseph II. The supporters of Franz Ferdinand were military men of conservative views but they were also proponents of a vernacular sort of internationalism,

Another activity associated with Franz Ferdinand was a renewed interest in heritage preservation. In 1906, the Archduke had become the official head of the empire’s military department, which was also responsible for the maintenance of buildings and works of art. He personally invested much into maintaining the regional peculiarities of ‘his’ lands, such as the wooden churches of Galicia, for example, which residents themselves were quite willing to replace with more durable stone buildings, but which he placed under national protection.Footnote 21 He also considerably expanded the state’s art collection, not least through his world travels, during which he collected specimens of art and natural history from various cultures, creating one of the first ethnographic museums. The purpose of these activities was to maintain control over the existing cultural diversity of the empire so that the dynasty and its cultural institutions could retain a monopoly over the overarching unity bridging the diverse cultures. Franz Ferdinand, in other words, prepared the institutions that would enable the Habsburg dynasty to give a form of identity for a multitude of people who had previously thought of themselves merely as Franz Josef’s ‘peoples’.Footnote 22

The company of travellers who had accompanied Franz Ferdinand on his grand tour went on to witness further developments in Europe on the various fronts. Carl Pietzner became the Habsburg court photographer in 1914, in time to document the war on the eastern front.Footnote 23 Prince Kinsky served in the Austro-Hungarian army on the Russian front, but died of a nervous disorder shortly upon his return in 1919. Count Pronáy lived to see the rise of Béla Kún’s communist regime in Hungary that year and joined the White Guards under Miklós Horthy who, in turn, had accompanied Franz Ferdinand’s uncle, Emperor Franz Josef, on his world tour as a young man, eventually falling during the Soviet siege of Budapest in 1944.

Lessons in internal colonization from Russia, Britain, and Japan

Despite their conservatism in terms of cultural values and their critical attitudes towards rival empires such as Russia and Britain, Franz Ferdinand and his circle were also influenced by their experience of Russian, British, and non-European government reforms. On his world tour, for example, Franz Ferdinand met the Austro-Hungarian consul Heinrich Coudenhove-Kalergi, a linguist of Dutch-Cretan origin, in Japan. Fluent in Japanese, among eighteen other, mostly Asiatic, languages, he had impressed Franz Ferdinand by translating a toast by Prince Arisugawa, a highly placed member of the imperial staff, honouring the Emperor.Footnote 24 Consul Coudenhove had been in Japan for two years by this point and, in 1893, married the young daughter of a well-to-do merchant, Mitsuko Aoyama.

Like some of Emperor Meiji’s consultants, Coudenhove was an advocate of reform; back in Austria, he had published a critical pamphlet suggesting that the nobility abandon its old practice of duelling, and had defended his doctoral dissertation with a critique of anti-Semitism.Footnote 25 The impact of his experience with the Meiji reforms and their abolition of the Samurai privileges found an unlikely interpretation in the context of Austrian society.Footnote 26 Coudenhove used his knowledge of the abolition of the Samurai practice of seppuku when in Japan to advocate the reform of duelling rights in Europe.

This was the third decade of the period now known as the Meiji Restoration, when a section of Japan’s governing elite actively sought to integrate Japan into world politics. In 1872–73, a Japanese committee of scientists and civil servants led by Prince Iwakura Tomomi inspected the practices of government and education in North America, Britain, France, Belgium, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Russia, Sweden, and Italy.Footnote 27 The committee’s historian, Kume Kunitake, marvelled at the technological progress Europe had made in the forty years since he had last seen it, with its railways, telegraphs, and completely new fashions. Of the German states, however, it was Prussia and not Austria-Hungary that most impressed the delegation.Footnote 28

In taking up his father’s vision for an internal reform of the nobility by arguing for the foundation of a new aristocracy – a kind of composite elite – to be formed by mixing tradition and new talent, a ‘serendipitous aristocracy’, Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi belonged to a minority in his generation. This was even more striking considering that, as he added, the vehicle for this form of social eugenics would be ‘socialism, the movement which started with the abolition of the nobility, the levelling of humanity’, but would culminate in the ‘cultivation of the nobility, the differentiation of humanity’. From the ‘ruins of pseudo-aristocracy’ humanity will create a ‘real, new nobility’.Footnote 29 In the 1920s, he wanted a multi-ethnic empire under Austrian leadership, whose political form was not necessarily monarchical. In the Austrian, German, and Czech press, Coudenhove criticized both Austrian-German parochialism in Bohemia and Austria, and Czech nationalism.

The Paneuropa project, with branches throughout central and western Europe, and sponsorship from Europe’s best-known banks and industries, went through stages in which it was called an association and a movement and, from 1932 onwards, a European party in a non-existent European parliament. From the start, the Austrian government had offered Coudenhove a representative space for his lobbying office in the Vienna Hofburg, so that the movement was registered under the illustrious address of ‘Paneuropa, Hofburg, Wien’ until the annexation of Austria by Germany in 1938.Footnote 30

The Paneuropa congresses were decorated by large portraits of great Europeans: Kant, Nietzsche, Mazzini, Napoleon, Dante, and others.Footnote 31 In one publication covering the event, a photograph of this pantheon was placed next to the portrait of Krishnamurthi, a living sage who was very popular in Germany at the time [Fig. 9].Footnote 32

The Pan-Europeanists’ architecture of public memory formed part of a quixotic palace of European memory.Footnote 33 It would be futile to attempt to reinsert some inherent logic according to which these very different intellectuals and their ideas of politics form a coherent montage of a European ideal. What we need is to understand how the invocation of these memory portraits on the walls of public buildings and private homes functioned in the social fabric of those who did ‘European civilization talk’ between the world wars, before it became ‘European civilization’ talk.

Coudenhove had shared and discussed his vision at London’s Chatham House, a foreign policy think tank, from as early as 1931, the year that the first Indian Congress met in India.Footnote 34 As the British Empire was gradually transforming itself into a commonwealth, Coudenhove and his Pan-European followers tried to make sense of continental Europe, whose empires had already begun to crumble. In place of imperial nostalgia, he presented to the world a rebranded idea of empire. His was not just a disenchanted, rational international order, as Wilson’s Presbyterian-influenced League of Nations had it. He proposed an emotional European patriotism with echoes of a Catholic and a Dantean ideal of a universal monarchy, with a pinch of Habsburg nostalgia.Footnote 35

Coudenhove fluctuated between a weaker notion of a federation of states (Staatenbund), as reflected in various wartime alliances like the Entente, and a stronger notion of a Bundesstaat, eventually preferring the latter.Footnote 36 Formally speaking, the Union was considered to be the natural successor of the Holy Roman Empire after the Napoleonic Wars; it was supposed to become a strengthened version of the Confederation of States established under the Congress of Vienna regulations of 1815. In the twentieth century, on the stage of international politics, the idea of a Union was juxtaposed with other supranational political organizations, such as the Soviet Union (which soon revealed its foreign political face as a revised Russian Empire), the ‘Pan-American’ Empire, and the British Empire and Commonwealth. Paneuropa was to be a macro-regional organization with world influence.

Its map presented this Pan-European territory as already existing. National boundaries within Europe, with the exception of Turkey, which was marked with a question mark, were not visually represented. In 1924, the Paneuropa programme demanded a ‘systematic exploration of the European economic colony of West Africa (French Africa, Libya, the Congo, Angola) as a European resource’.Footnote 37 Coudenhove’s aim, as he put it in 1934, was to turn Europe into a community of values, constituted by ‘Greek philosophy, Roman law, Christian religion, the lifestyle of a true gentleman and the declaration of human rights’.Footnote 38 The question mark on Turkey was due to some of its territory belonging to Europe ‘despite’ its Muslim heritage, a conceptual problem for Coudenhove’s Christian conception of European identity.

Coudenhove believed that ‘Nietzsche’s Will to Power is where the foundational thoughts of fascist and Paneuropean politics stand side by side’.Footnote 39 Kant’s presence in his pantheon of Europeanists, along with that of Hugo Grotius as well as the 18th-century balance of power theorists (Mirabeau, Abbé de St. Pierre), was due to their endorsement of European unity as an abstract goal, though this in many ways fits uncomfortably both with Nietzsche’s ‘aristocratic radicalism’ and with the discourse of national sovereignty signalled by the presence of Giuseppe Mazzini on Paneuropa’s symbolic map.

Drawing on Giuseppe Mazzini’s Europe: Its Conditions and Prospects, Coudenhove picked up on the traditions of the Young Europe movement, which bridged nationalism and cosmopolitanism. The combination between the two principles was also the motivation behind including the Bohemian humanist Comenius. Coudenhove’s journal, Paneuropa, devoted a great deal of attention to publishing seminal texts in which European identity was discussed. Nietzsche’s Will to Power manuscriptsFootnote 40 were part of a reading list Coudenhove-Kalergi set for future Pan-Europeans, which also included Napoleon’s Political Testament,Footnote 41 as well as about a dozen or so other works by Dante, Comenius, Grotius, Kant, and Mazzini.Footnote 42 At the opening of the first Pan-European Congress in 1924, Coudenhove’s wife Ida Roland recited Victor Hugo’s speech on European unification ‘in the service of propaganda for the Paneuropean idea’.Footnote 43

The symbol of the Paneuropa movement, a red cross against the yellow sun of Hellenic Greece, reveals the intellectual legacies to which Coudenhove imagined himself heir: what could be called the Christian tradition of geopolitical integration, historically framed from the Crusades, to the European unification models of Abbé St. Pierre, and to the Christian socialism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Within this tradition, Freemasonry was an important sub-group; and indeed, Coudenhove himself regarded Enlightenment projects which themselves criticized Christian traditions as falling within the Christian trajectory. The intellectual background of masonic eclecticism merged neo-Hellenic ideals with Kantian rationalism as well as the German ideal of Bildung, the ideal of culture and education, together with more recent calls for German cultural unity and an imperial discourse. These strands of thought were invoked at Coudenhove’s first international Paneuropa Congress.

This genealogy of European unity as Coudenhove presented it was thus composed of several sometimes contradictory traditions: ideas of a Christian empire and monarchy; ideas of national liberation which were based on resistance to large dynasties; ideas of a balance of power and contrary ideas of economic integration by its critics; and the emphasis on charismatic political leadership and technology as features of modern political systems, against the neo-medievalism of some of his other beliefs. Coudenhove’s Christian–Hellenic baggage did not prevent him from speaking of Vienna as ‘the Mecca of the Paneuropean Union’.Footnote 44 In establishing this account of Paneuropa’s pedigree, Coudenhove not only marketed the noble ancestry of his own idea, but also sought to borrow authorities from other political movements. He reclaimed Kant and Grotius from Wilson and the liberal internationalists; Mazzini from the European nationalists such as Masaryk; and Victor Hugo from the social democrats. In drawing on a variety of authors, Coudenhove emphasized the inherently cosmopolitan background of the European ideal. The masonic eclecticism of his ideal of Europe was, interestingly, strongly reminiscent of the City of the Sun narrative by Tommaso de Campanella, whose depiction of this ideal city included references to Egyptian and Roman polytheism just as to Christianity, Islam, and fiction.

Britain, Coudenhove argued, had to be excluded for reasons of a global balance of power, while Paneuropa was to be modelled after what Coudenhove called ‘Pan-America’ both in its federal structure and its attitude to colonial resource. Coudenhove called for a revision of the Versailles agreement, especially with regard to the question of German (and Austrian) war guilt; a perpetual peace between all the European states; doing away with any customs and other economic borders and bringing about a unified currency; a joint army and fleet; a European limes on its eastern border and erosion of all inner European borders; a true guarantee of minority rights and the introduction of punishment for any propaganda of hate in the press; a Europeanization of education at schools; and a Pan-European constitution.Footnote 45 Paneuropa was thus based on an essentialist perspective on European identity, and yet demanded policies of identity construction through education and infrastructure.

This vision had particular appeal among the non-British subjects of the Commonwealth present at gatherings such as the meeting at Chatham House. One of them was Abdullah Yusuf Ali, a Muslim British Indian and Qu’ran scholar who had been instrumental in securing Indian support for the allied war effort in the First World War. What Churchill, Coudenhove, and Yusuf Ali had in common was the belief that empires had to be reformed but not destroyed, that it was possible to decolonize without losing the sense of empire. The making of this memory was a complex social process, which was driven by the intellectual communities of interwar Europe.Footnote 46

Coudenhove thought of the Paneuropa movement as supra-political and was happy to invite fascists and corporatists such as Benito Mussolini in Italy and Kurt Schuschnigg and Engelbert Dollfuß in Austria to patronize it. Despite this, he resisted the Nazis on account of their racial ideology and their pan-German treatment of Austria, and was in turn blacklisted by the Nazi party in 1933. The night of the Dollfuß murder, the Coudenhoves fled together with Dollfuß’s wife via Hungary and Switzerland to Italy, where Coudenhove-Kalergi notified ‘Mussolini through an Italian envoy’ that they would be ‘passing through Italy with Mrs Dollfuss and her children’. When Coudenhove looked back at his life up to this point, he concluded: ‘The world in which I had grown up has disappeared. The dynasty [the Habsburgs] which my ancestors had followed from Holland to Belgium, and from Belgium to Austria, was overthrown and disempowered. The influence of the nobility was broken. The new world was democratic, republican, socialist and pacifist’.Footnote 47 After the annexation of Austria by Germany in 1938, when Coudenhove was forced to flee Austria, the movement’s central idea of reviving a European multi-ethnic empire based in Vienna had evidently failed. In 1940, the Coudenhoves left Europe for New York.

While Joseph Roth’s hero Franz Ferdinand went to the Capuchin vault to mourn, Coudenhove chose a different path, first becoming a professor of history at New York’s Columbia University and then an activist advocate for Paneuropa, in Switzerland, where the Habsburgs’ history had begun. Obtaining a teaching position in history and politics at New York University, supported by the Carnegie Foundation, Coudenhove revived Paneuropa in exile by founding a Research Centre for European Reconstruction which hosted a Pan-European congress there in 1943, inviting other exiles from Europe.Footnote 48 Here, in 1977, Otto von Habsburg unveiled a monument commemorating Aurel Popovici’s (and Franz Ferdinand’s) work.

Personified cosmopolitanism

Coudenhove’s movement was characterized by a tendency to relate the more abstract genealogy of European unity to concrete historical personalities, as well as to a performance of his own cosmopolitan history. Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi’s mother, Mitsuko Aoyama, came from a Japanese Buddhist family and had converted to Catholicism.Footnote 49 She was one of the first Japanese women of her status to marry a western man. Coudenhove’s wife, who became a lifelong champion of his ideas and co-manager of the project, was the Austrian Jewish actress Ida Roland.Footnote 50 Having to choose a country of citizenship after the revolution of 1918, he opted for a Czechoslovakian passport based on his place of residence, arguing that he was ‘a citizen of the Republic of Czechoslovakia without feeling a commonality of sentiment with this state, apart from my personal admiration for its president Masaryk. Because I belong to German Bohemia and grew up there, I do not [even] have command of my country’s official language’.Footnote 51

The Enlightenment roots of his father’s ideas were still visible in the junior Coudenhove’s plans. His letter of application to the Humanitas lodge, of which his father was already a member, shows the importance of his multi-continental heritage for Coudenhove’s political ideas: ‘Being children of a European and an Asian, thought in terms not of nations but of continents. […] Thus in our eyes Europe was always evidently unified – it was the land of our father’.Footnote 52 He saw himself as a ‘half Japanese child’ whose projects culminated in the ‘first successes of the work on European unification’.Footnote 53 ‘My father’, Coudenhove-Kalergi wrote in this motivational letter, was ‘a European with Flemish, Greek, Russian, Polish, German, and Norwegian noble blood’, whilst his mother was of ‘bourgeois Japanese’ origin. It was as ‘a consequence of this background’ that Coudenhove therefore lacked ‘any exclusive belonging to a nation [Volk], to a race’. He considered himself to belong to the ‘European cultural community and, in a narrower sense, to the German one, but not in the sense of some sort of nationalism’. For these reasons, Coudenhove could only describe his political identity as cosmopolitan and his social circles as stretching across all ‘social spheres and professions’.Footnote 54

Coudenhove’s first individual publications bore close resemblance to the moral ideals behind the political activity of the Freemasons, which, for the first time, had gained formal legal acceptance in the Austrian republic. His book Ethik und Hyperethik (1922) was reviewed favourably in the Wiener Freimaurer-Zeitung (1/3, 1922), a new organ that had begun operating since the legalization of Freemasonry. By mid-1925, the master of the Viennese lodge, Richard Schlesinger, sent a circular to the masters of the great lodges of the world asking them to support Coudenhove-Kalergi’s political projects.Footnote 55

A number of Coudenhove-Kalergi’s contacts also shared a background in Masonic thought. Coudenhove-Kalergi’s application to join the Viennese Freemasons was supported, among others, by the engineer and social philosopher Josef Popper-Lynkaeus and the legal theorist, and future Schmitt opponent, Hugo Heller.Footnote 56 Although Coudenhove was admitted to the lodge, his notion of propaganda and open publicity of political ideals did not fit comfortably with the historically subtle influence of Masonic thought in Europe. Even though the Freemasons themselves expanded their modes of influencing the public after 1918 by founding a newspaper, Coudenhove’s use of publicity was not welcome. After 1926, Coudenhove had grown disenchanted with the Masons. Nonetheless, he probably owed his positive connection with Masaryk and Beneš – with whom he disagreed on almost all matters of policy, from the debate over the customs union between Austria and Germany in 1931, which he endorsed and they dreaded, to the status of Germans in Czechoslovakia – to their shared Masonic heritage adding to their perspectives a touch of cosmopolitan elitism.

Coudenhove-Kalergi also shared his father’s critique of anti-Semitism, which he had edited prior to its publication.Footnote 57 His wife, the actress Ida Roland, was Jewish. Rather than socializing at the salons of high nobility, he instead joined his wife’s more socially mixed circles of writers, artists, and publishers, such as the salon of the Zsolnay family, a Jewish family whose regular visitors included writers like Arthur Schnitzler and Max Brod. Coudenhove’s cosmopolitan elitism was more in tune with the views of a cosmopolitan elite based in Vienna. The notion of ‘Heimat’, or home country, was seen in this circle as parochial, petit-bourgeois, primitive, anti-urban and anti-enlightenment, worthy only of the sharpest criticism.Footnote 58

Paneuropa was one of many geopolitical concepts of European power politics developed between the end of the nineteenth century and the 1920s. This territorial perspective on identity was encompassed by the emerging discipline of geopolitics, which was founded, in the wake of the work of nineteenth-century German liberals such as Alexander von Humboldt, by conservative political theorists in Sweden and Germany, including Johan Rudolf Kjellén, Friedrich Ratzel, and Karl Haushofer.Footnote 59 But Paneuropa was also responding to radical alternatives on the political Left. In June 1923, Leon Trotsky called for a European Socialist Federation under the name of ‘The United States of Europe’, which he saw as a way out of the fragments of the old empires and towards a future worker-led global order. As he put it then, ‘the moment British capitalism is overthrown the British Isles will enter as a welcome member into the European Federation’.Footnote 60 Working against the Soviet paradigm of the European Union as an instrument for a permanent world revolution, but also competing with the idea of a devolved British Commonwealth, Coudenhove-Kalergi selectively appropriated some elements of both rival projects of Pan-European influence. He took the pathos and rhetoric from Trotsky, but rested the economic and ideological foundations of his organizations on the capitalist and imperialist principles of the Commonwealth. His archive of designs for the Paneuropa Congress contains examples of a set of newspapers from the Soviet Union with their characteristic modernist aesthetic as models for Paneuropa, alongside models of stamps coming from a more traditional empire, the British [Fig. 10]. This particular newspaper featured headings such as the need for ‘mass organisations’ of the future, an idea which also appealed to Coudenhove.

Figure 10 Soviet models for Paneuropa. Newspaper Upakovshchik [‘The Packer’].

The aristocrat as a social mediator

‘This book is designed to awaken a great political movement slumbering within all peoples of Europe’, Coudenhove pronounced in the first edition of his Pan-European project.Footnote 61 He sent several thousand free copies of his first Paneuropa manifesto to politicians around the world. It was translated into English in 1926, French in 1927, then Czech, Croatian, Spanish, Hungarian, Lithuanian, and Greek, but never into Russian or Italian.Footnote 62

Coudenhove-Kalergi’s strategy of influence was a more insistent and efficient propaganda effort than those of most of his contemporary theorists on European unity. It comprised a fee-paying and listed membership in his Paneuropa association; the publication of programmatic articles and opinion surveys in different press formats; the foundation of the journal Paneuropa, which was explicitly devoted to propaganda and hence did not publish any critical articles of itself; and his own private correspondence and communication network, to which he and his wife devoted considerable time. Coudenhove also organized a number of international congresses, typically held in one of the European capitals’ large hotels, bringing together politicians and industrialists.Footnote 63

Coudenhove kept in touch with a diversity of what could be described as leader personalities from the spheres of politics, art and literature, and industry, and he put considerable effort into putting them in touch with each other. Many of the politicians and other activists Coudenhove worked with were also proponents of an eclectic blend of political views. This model of Europe as an imperial power was supported particularly by intellectuals. Interestingly, while Paneuropa attracted mostly reconstructed conservative thinkers like German Chancellor, and later Foreign Minister Gustav Stresemann, in France and in central Europe, it proved attractive to socialists, such as French President Aristide Briand, and the former Dreyfusards, such as radical socialist French Foreign Minister Edouard Herriot and economic theorist Francis Delaisi.Footnote 64

In Britain, a new, non-governmental think tank which emerged after the First World War, Chatham House, was an important semi-public site where the imperial and colonial elites tested their ideas of imperial devolution in Europe and the world of the European empires. Coudenhove was invited as a guest from the Continent, and his ideas were widely received.Footnote 65 Here, Coudenhove was in dialogue with Muslim representatives of the Indian Congress and other intellectuals. In Britain, this strand of thought led to the emerging discipline of International Relations in Aberystwyth.Footnote 66 At the same time, among his followers in central and eastern Europe, Coudenhove gained prominence not only through his connections to Masaryk and the Polish Foreign Minister Zaleski but also through his lecture tours, including a trip to Warsaw in 1925.Footnote 67 Among the statesmen most influenced by the Pan-European project were Aristide Briand – whose collaboration with Coudenhove culminated in his announcement of a European federation in 1930 – Edvard Beneš, Gustav Stresemann, and Tomas Masaryk.

In its initial stages, Richard Coudenhove-Kalergi’s Paneuropa project was financed wholly from his private sources.Footnote 68 He quickly attracted enough attention to bring in other funding, mostly through elite circles of bankers, industrialists, and aristocrats. These comprised the Czech entrepreneur (and owner of the famous shoe production chain), Tomas Bata; the German industrialists Paul Silverberg, Carl Siemens, Adam Opel, Edmund Stinnes, Richard Gütermann, and Hermann Bücher (of the AEG, the German General Electricity Company); Carl Duisberg (of the Bayer corporation); a group of private German bankers; the Dutch industrialist N.V. Philips; and the Austrian Otto Böhler.Footnote 69 The US-American Carnegie Foundation for Peace, headed by Nicholas Murray Butler – who published a book on Paneuropa six years before Coudenhove’s first publication on the subject – also supported the project.Footnote 70 All of these figures, along with the governments of several European states, donated money in support of Pan-European’s activities.Footnote 71 In the later 1920s, the founders of the summer conference at Pontigny in France and the Mayrisch circle in Colpach, Luxembourg, were among Coudenhove’s social contacts.Footnote 72 These events were occasions for members of the industrial elites, especially of France, Belgium, Luxemburg, Germany, and Austria, to meet and discuss concerns as well as to invite writers and poets for entertainment and what could be described as public relations purposes. Coudenhove played a role as a mediator on these occasions. The nature of his connection with bankers and industrialists can be illustrated by taking a more detailed look at Coudenhove’s relationship with three of them: the Hamburg-based banker Max Warburg, heir to the European branch of the private bank M.M. Warburg & CO; the Stuttgart-based industrialist Robert Bosch; and the Luxemburg-based Emile Mayrisch.

Banker Max Warburg heard about Coudenhove’s enterprise through Baron Louis Rothschild and offered to support the project with 60,000 gold marks. In 1926, Warburg also sponsored the travel costs and royalties for speakers attending the Paneuropa Congress in Vienna.Footnote 73 Warburg was simultaneously financially supporting other similar movements, ranging from Die Deutsche Nation to the Nietzsche Archive, his brother’s Warburg Institute, and a number of other projects, seeking always to maximize his reach and influence. By the end of the 1920s, Warburg’s support for Paneuropa subsided, since, as he put it to Coudenhove, his concern was that the movement was not sufficiently pragmatic.

Bosch’s support came thanks to the mediation of another sponsor of Paneuropa, Richard Heilner (head of a German linoleum company in Wuerttemberg), who in 1927 recommended Coudenhove-Kalergi to Bosch.Footnote 74 Like Warburg, Robert Bosch was also investing in a number of rival political movements, including Karl Anton Rohan’s Kulturbund, but expressly demanded not to be listed as a public supporter. In fact, Bosch, who was a good friend of the British internationalist David Davies, was at first critical of Coudenhove-Kalergi’s exclusion of Britain from his proposed union, but was ultimately convinced and provided a link between Coudenhove-Kalergi and a number of British internationalists of the period. Bosch promised to contribute an annual sum of 2,500 Reichsmarks beginning in 1928, but in fact contributed even more until 1933. In 1930, he encouraged Coudenhove to found the ‘Society for the Promotion of the Paneuropean Cause’ (Pan-Europäische Förderungsgesellschaft) and took a seat on its directorial board. But Bosch withdrew his support immediately when the Nazi government officially blacklisted Paneuropa, significantly undermining Pan-European activities in Germany.

In addition to prominent figures representing individual banks and industry, like Warburg and Bosch, one of Coudenhove’s most successful networking connections was with the founder of the European steel cartel, the Luxemburg industrialist Emile Mayrisch. Mayrisch was the organizer of a series of summer conferences at Colpach, which brought together politicians, industrialists, and intellectuals, especially of German, Austrian, and French origin. He was one of the interwar proponents of the idea that European integration had to begin with a union of German and French interests on the Rhine and founded the German-French Committee of Studies to discuss this form of integration. Coudenhove participated in these meetings, on the one hand as a representative of his own Paneuropa movement, and on the other hand as a representative of Czechoslovakia, whose cause he endorsed internationally by supporting the work of Masaryk and Beneš.

One of Coudenhove’s chief strategies of getting prominent politicians on board was offering them honorary presidencies at Pan-European congresses, which he organized at regular intervals. The most important politicians to back Paneuropa in this way were Tomáš Masaryk, Edvard Beneš, Gustav Stresemann, Aristide Briand, Leo Amery, Zaleski, and Winston Churchill. Like Coudenhove, Beneš, and Masaryk, Zaleski joined the Freemasons during the First World War; he was a lecturer in Polish language and literature in London at the time, and was foreign minister of Poland between 1926 and 1932.Footnote 75

Apart from Briand, socialists such as Karl Renner were typically reluctant if not entirely negative towards Paneuropa. Nationalists such as Masaryk and Beneš, on the other hand, supported Coudenhove’s work as an international political mediator and themselves encouraged other politicians to join his movement.

In connection with the organization of a Pan-European economic forum in the late 1920s, Coudenhove corresponded with, among other prominent politicians with a background in industry, the French Minister of Labour, Louis Loucheur.Footnote 76 He was put in touch with Loucheur through his friend and Paneuropa supporter, Edvard Beneš.Footnote 77 Beneš wrote a note to the French conservative politician and technocrat Louis Loucheur (1872–1931), then the French finance minister, in which he offered to bring Coudenhove to his first meeting with Loucheur in 1925: ‘Dear Sir, the bearer of this letter is Mr Coudenhove-Kalergi, whose writings on Pan-Europe you surely know. I ask you to give him a favourable welcome and to provide him with the opportunity to lay out his pacifist ideals.’Footnote 78 This encounter then led to a series of meetings Coudenhove encouraged between German industrialists and Loucheur.Footnote 79 In the course of Coudenhove’s correspondence with Loucheur, Coudenhove brought the Luxemburg industrialist Emile Mayrisch (January 1928), Bücher (of the AEG, February 1928), figures from Rhenish industry, Karl von Siemens, the director of the Warburg Bank, Karl Melchior, Caro of the Stickstoffwerke, Richard Heilner of the Linoleum factories, and Count Kanitz, German food minister (May 1928), together in a series of meetings.

The year when Germany joined the League of Nations, 1926, was also fortuitous for the Pan-European union. By 1927, Briand had become the honorary president of the union, and Coudenhove’s activities in this regard contributed significantly to the success of the Young plan, which was effectively a revision of the Versailles treaty, brought about following talks between Briand and Stresemann in 1929. In the spirit of international agreement following Locarno and the Kellogg-Briand pact stabilizing especially German–French relations, symbolized by the constructive policies of Stresemann and Briand, Briand produced a ‘Sketch for a Paneuropean pact’, officially presented in public in May 1930.Footnote 80 Indeed, in 1930, which perhaps was the culmination of Coudenhove’s activities for a Pan-European Union, Briand announced his plan to work on a European Union of twenty-six states based on Coudenhove’s model.Footnote 81 However, most European governments gave this publication a cool reception at best.

Coudenhove was also seeking to win over liberal internationalists, particularly German and Austrian liberals and social democrats, French socialists, and British liberal internationalists, especially proponents of a Christian empire espoused by figures such as Winston Churchill, David Davies, and Alfred Zimmern. From its inception, Coudenhove sought to involve Austrian, German, and French socialists in his Paneuropa movement – at least, those who sought no connection with Moscow. His move to contact the Briand government in 1925, after the defeat of the conservative Poincare, was motivated by the desire to engage the ‘new leftist government’ at a moment in time when they were ‘searching for a new slogan to replace the nationalistic sentiments of revenge and resentment’.Footnote 82 With the same intentions, Coudenhove published a questionnaire to be sent to politicians of different European countries, but especially to internationalists like socialists or liberals, asking their opinion of a Pan-European Union. He then published their responses in his journal. The social democrat Karl Renner responded to the questionnaire by saying that the union was indeed ‘an economic and cultural necessity’.Footnote 83 However, a year later, Renner distanced himself from the movement due to its express anti-Bolshevism.Footnote 84

Similarly, in 1918, Coudenhove associated himself with the socialist Kurt Hiller, whose ‘Political Council of Spiritual Workers’ (Politischer Rat geistiger Arbeiter), founded in November 1918 in Munich, attracted people who were socialist but felt uncomfortable in a socialist party. What attracted Coudenhove to this project was neither its advocated pacifism nor its idea of council democracy, but rather the intellectual elitism that was reflected in Hiller’s programme of a ‘global intellectual logocracy’.Footnote 85 Hiller, like Renner, later abandoned the connection due to Coudenhove’s explicit anti-Bolshevism.Footnote 86

Among Coudenhove’s least successful attempts to influence government members was his attempt at a solution of the Polish corridor problem, which, being an outcome of the Versailles settlement, separated two parts of Prussia from each other.Footnote 87 Realizing that Poland found it unacceptable to renounce its only access to its main port, Gdynia, whilst Germany could not accept East Prussia being separated, Coudenhove proposed building a special corridor comprising a double railway line and an automobile route, which would connect Danzig viz. East Prussia with the rest of the ‘Reich territory’. This line could not be maintained without infringing on Polish transportation within the corridor, ‘it will have to pass subterraneously through a tunnel. A commission consisting of a representative of the German and the Polish government will coordinate all the conflicts resulting from this technical-juridical construction’.Footnote 88

One of the reasons for Coudenhove’s project coming to a halt around 1931 was that, within a short time span, a number of influential politicians and industrialists who had been supporting Coudenhove had died: Emile Mayrisch died in 1928, Gustav Stresemann in 1929, Louis Loucheur in 1931, and Aristide Briand in 1932.

From Paneuropa to the Cold War

Beyond Germany, Austria, and central Europe, Paneuropa had a lasting legacy in the Christian conservative circles of the Anglo-American elite. These included Leo Amery who, like Coudenhove-Kalergi, had an ethnically mixed and cosmopolitan background; his mother was of Hungarian-Jewish background, and he grew up in India. A co-author of the Balfour Declaration in 1917, Amery supported Paneuropa in the 1930s and also corresponded with Coudenhove concerning other matters, such as the problem of Europe’s Jewish population, which Coudenhove proposed to settle in Rhodesia.

But the most prominent British politician to have been influenced by Coudenhove was Winston Churchill, who in his speech on Europe’s need to unite praised the ‘work […] done upon this task by the exertions of the Pan-European Union which owes so much to Count Coudenhove-Kalergi and which commended the services of the famous French patriot and statesman, Aristide Briand’. Just like Coudenhove, who presented the union of Swiss cantons as an example for Europe, Churchill concluded his call for European unification by declaring that Europe should be ‘as free and happy as Switzerland is today’. This was far from Max Weber’s demand for national greatness to avoid succumbing to Swissification.Footnote 89 But Coudenhove’s propaganda efforts eventually were absorbed in the Franco-British plans for European integration. One of the images of Coudenhove after the Second World War shows him seated next to Robert Schuman in the European parliament.

Figure 11 Coudenhove with Robert Schuman in 1956.

In the last decades of the Cold War, political theorists in the United States began to use the term ‘transnational’ to speak of social connections beyond the control of states, as well as to call ‘soft power’ the ability to get people to do what you want without coercing them through weapons.Footnote 90 Unlike the ‘hard’, institutional power of states, soft power achieves influence through gradual projects in culture and education. But these terms also apply remarkably well to the remains of Austria-Hungary, a multinational empire that had no overseas possessions but rather a multicultural, internal space of influence. In addition to regular forms of coercion, Austria-Hungary was notable for centuries for the cultural prowess of its dynasty, the Habsburgs. After the revolution, aristocratic privilege in Austria was abolished and the Habsburgs sent into exile; however, many elements of their established practice of ‘soft power’ and of social connections across the borders of their empire’s component states survived. It was on the foundations of these traditions, I submit, that a number of Viennese intellectuals began to develop new projects for European unity. In the absence of the ‘hard’ power of an imperial army, which in the course of the Great War had fragmented into its national components, they embraced the ‘soft’ power of culture and informal networking between intellectuals, bankers, and industrialists.Footnote 91

‘German Princes and Nobility Rush Funds to Neutral Lands’, the Geneva correspondent of the New York Times noted in October 1918. Citing a Swiss banker, he observed that a ‘large proportion of the depositors bringing their money from Germany and Austria belong to the princely families, posing under assumed names’.Footnote 1 The work of a newsmaker in Europe between 1917 and 1920 must have been exciting and hopeless at once. From the Urals to the Alps, with each deposed monarch, with each exiled prince, European society was becoming increasingly unfamiliar. Many people inhabiting this large territory felt compelled to reinvent themselves under new banners: national democracies, classless societies, people without land. One of the tasks for the relatively new craft of world news reporting was to give readers a provisional image of this continent’s new appearance when its former faces had become mere phantoms. A focus on the German princes allowed grasping imperial decline of the Hohenzollern, Romanoff, Habsburg, and Osman dynasties at once, and in historical perspective. As a shorthand identity, ‘German princes and nobility’ reveals a slice of imperial decline of more than one empire.Footnote 2

At the same time, in Germany itself, even liberals were unsure whether a revolution had actually occurred. Not only did some Germans resent living in times ‘without emperors’,Footnote 3 contemporaries of liberal and even socialist leanings also expressed doubts about the viability of the German revolutions, which seemed feeble and theatrical compared to the images from Russia.Footnote 4 Somebody who is accustomed to images of the October Revolution – many of which, incidentally, were only produced retrospectively, in 1927 – would look in vain for an iconic equivalent from Germany.

In November 1918, the pro-republican Vossische Zeitung featured a confusing photograph of crowds gathered in Berlin on its front page, with a backward-facing Bismarck statue instead of the proclamation of the republic [Fig. 12].

Figure 12 Voss Zeitbilder, 17 November 1918, 1

It took the newspaper several days to change its name from ‘Royal Berlin newspaper for political and intellectual affairs’ to ‘Berlin newspaper for political and intellectual affairs’. Even on the five-year anniversary of the revolution, its weekend supplement showed no photographs from November 1918. Instead of images of crowds, the editors placed a large map of the world on the front page, which advertised the need for radio networks in post-war Germany, featuring the Atlantic Ocean more prominently than the continent of Europe [Fig. 13].Footnote 5

Figure 13 Die Voss, Auslands-Ausgabe, 45 (10 November 1923), 1

There was a debate whether to blow up the statues of Prussian kings adorning the Alley of Victory (‘Siegesallee’), an unpopular project initiated by Wilhelm II to commemorate the defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–71 and derisively called ‘Alley of Puppets’ in Berlin. It had only been completed in 1901 and included a genealogical parade of German rulers from Albrecht of Prussia, the last grand master of the Teutonic Order, to the Prussian King Wilhelm I. The satirist Kurt Tucholsky asked himself: ‘What will come of the Siegesallee? Will they drive it out of the city towards the New Lake because it is too royalist, too autocratic and too monarchist? […] Will they maintain the statues but place new heads on the same necks? […] And was all that learning of their names for my exams in vain?’Footnote 6 In the end they remained in place until Albert Speer’s grand plan to make Berlin fit for the Nazi empire forcibly removed them to a new location in 1938, where they were partially destroyed by allied bombs, then demolished under the auspices of the British and Soviet occupation, the remaining figures buried in the ground, only to be restored and reconstructed in 2009.Footnote 7

Hans-Hasso von Veltheim, the officer who had served in the reconnaissance photography department of the Saxon royal army in the First World War, confessed that he experienced the European revolutions as a ‘purifying and revitalising’ force that may yet ‘constitute a large step forward’.Footnote 8 This did not prevent him from serving as a volunteer officer in a dismantled Cavalry Division of the imperial guard in Berlin in 1919. Under the leadership of Waldemar Pabst and Reichswehr minister Gustav Noske, this division was chiefly responsible for crushing the socialist rebellions in Berlin in early January 1919. But when the Spartakists Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg were assassinated in the same month, Pabst himself was suspected of masterminding the murder. Veltheim chose to attend their funeral in civil attire. He confessed to his wife that he was ‘deeply moved’ by the ‘composure of this immeasurable, enormous crowd’. Deputies from ‘Switzerland, Holland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, Warsaw, Vienna, Sophia’ were among the mourners, and the ‘funeral procession of a Kaiser could not have been more ornate, dignified and moving’. One of the ‘proletariat’, as he described it, even offered him a sandwich, although ‘the man knew’ that he was ‘Oberleutnant and Dr. phil’.Footnote 9 Choosing Munich as his base for the next years, Veltheim sympathetically witnessed the socialist revolution there. He corresponded with the anarchist Gustav Klingelhöfer, who was imprisoned for treason for joining the revolutionaries of the Munich Council Republic, particularly the Red Army group led by Ernst Toller.

While individual aristocrats, like the representatives of other social groups, aligned with a variety of social forces during the revolution, aristocratic families remained objects of critique in central Europe. These ruling families saw themselves as the descendants of families who, for generations, had acquired distinction in ruling over Europe’s vernacular populations of Slavs, Anglo-Saxons, various Germanic tribes, Celts, Galls, Roma, Jews, and other groups. In popular culture, the traits associated with most of these folk groups – visual features, professional affiliations, and such like – usually appeared as marks of stigma or inferiority; but for nobles, their special qualities were always marks of distinction. If in many traditional cultures, unusual physical traits are associated with some kind of evil – one need only to think of the image of the hunchback, or the witch, in the case of nobles, some traits of this kind, such as the Habsburgs’ protruding lip, were used to mark a special kind of familial charisma.Footnote 10

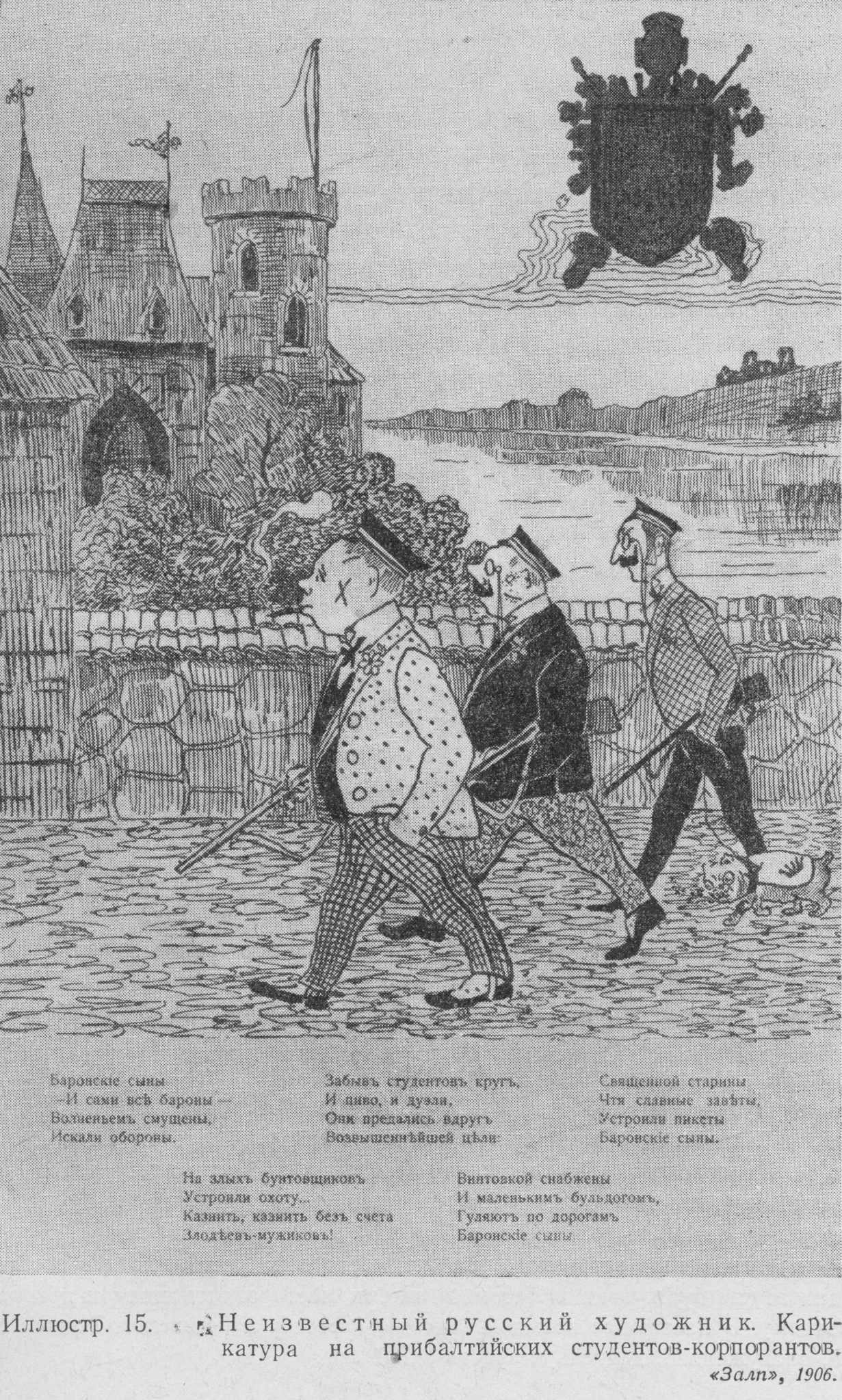

In the early twentieth century, German aristocrats had become objects of satire in Germany and in the Habsburg lands. The Munich-based satirical magazine Simplicissimus ridiculed the Ostelbian Barons as symbols of the old world. ‘Let them cremate you, papa, then you won’t have to turn so much later on,’ reads the caption on one caricature dating from 1906 [Fig. 14].

After the First World War, such jokes became more serious. Election posters made the expropriation of former princes into one of the key rallying cries for voters.

In Czechoslovakia, National Democratic Party member Bohumil Nĕmec argued that ‘nationally foreign […] and rapacious noble families’ had been causing harm to the Czech nation throughout history.Footnote 11 Ironically, his own Slavic surname, which means ‘German’, hints at the history of ethnic relations in his place of origin. The imperial nobility, previously backed by the ancient power of the Habsburgs in the region, became merely another ethnic German minority, which the new governments viewed as being on a par with others, such as the Sudeten Germans.Footnote 12 In both Russia and Czechoslovakia, German nobles were granted citizenship in the new states but were effectively barred from participating in politics and exercising traditional feudal privileges like holding court.

In other states, aristocrats were mistrusted due to the disproportionate privilege they had enjoyed under the imperial governments. In fact, in Germany, for instance, already by the beginning of the twentieth century some members of the nobility had begun to organize themselves like an interest group whose interests go beyond party affiliations, such as the Agrarian Union or the Colonial Society. A number of nobles joined conservative associations of nobles such as the Deutsche Adelsgenossenschaft or the Deutscher Herrenklub, founded in 1924 by Heinrich von Gleichen; many Baltic Germans joined associations such as the Baltische Ritterschaften, which had their seat in Germany, but were active throughout western Europe in the interwar period. Other nobles from the Russian Empire joined the Union de la Noblesse Russe in France, which was founded in 1925, or aristocratic charitable organizations. Others again, particularly members of dynastic families, were active in chivalric associations, such as the Order of the Golden Fleece, the Order of St. John, and others.Footnote 13 The very idea of an aristocratic association was a modern concept, and quite unlike the medieval knighthoods known from such groups associated with the Arthurean legends as the Knights of the Round Table or the Order of the Garter. The modern associations which emerged in late imperial and republican Germany, the most prominent of which was the Deutsche Adelsgenossenschaft, were in fact alternatives to parties. In this way they were a reaction to growing parliamentarization, more than the enactment of a medieval ideal. The very idea of a Genossenschaft of nobles is, conceptually speaking, somewhat absurd. The modern equivalent of that would an imaginary CEO solidarity network, a sort of elite cartel that borrows its language from groups socially and economically inferior to itself. As such, they became what Stefan Malinowski has called ‘laboratories of aristocratic reorientation’, that is, places of mutual aristocrat recognition, as much as organizations serving the purpose of making aristocrats recognized by their non-aristocratic fellow citizens.

In Germany, a communist member of the German Reichstag recalled the words of none other than Robespierre, who justified the execution of Louis XVI as ‘not a decision for or against a man’ but a ‘measure for the public good, an act of national precaution’.Footnote 14 During the revolutionary period before the ratification of the constitution, the new governments of some former German principalities, for instance, Hessen Darmstadt, had already expropriated ‘their’ nobles as part of their revolutionary measures.

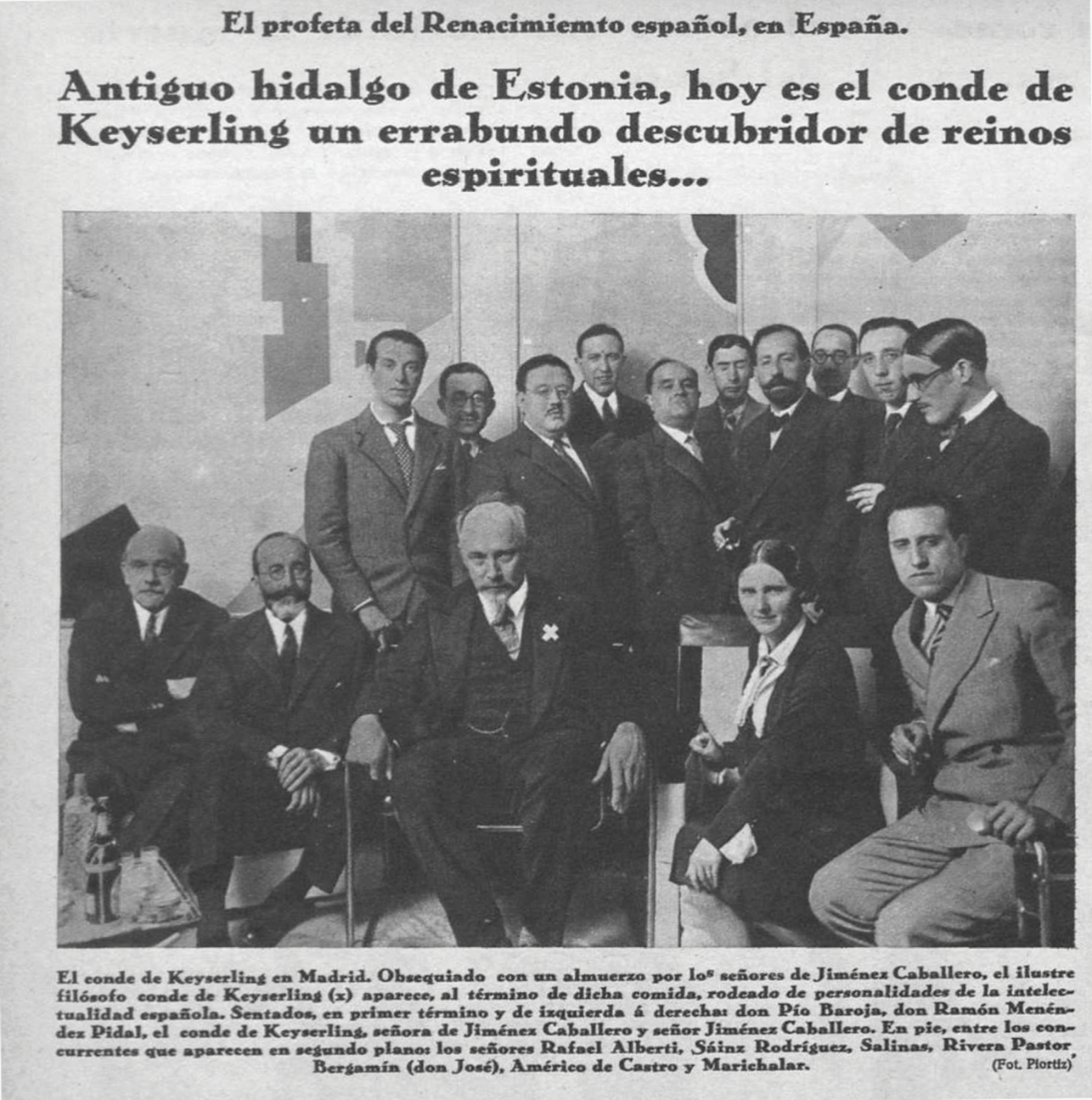

Although the constitutions of some smaller German states had ceased recognizing the nobility long before the revolution – for instance, the constitution of the Free City of Bremen from the period of the Kaiserreich did not acknowledge nobility as a politically privileged status – the majority of regional German constitutions had been dominated by the principles of monarchy and nobility, which only changed radically in 1918–19.Footnote 15 A government initiative for a mass expropriation of nobles, documented in photographs of election campaigns, failed to reach a quorum because only 39.3 per cent of the electorate voted [Fig. 15].Footnote 16

Figure 15 ‘Not a penny for the princes!’ Election poster from Germany, 1926. ‘Den Fürsten keinen Pfennig! Sie haben genug! -rettet dem Volk 2 Milliarden Den Notleidenden soll es zugute kommen!’ [Not a penny for the Princes! They have enough! – save 2 billion for the people/It should benefit those in need!] Election propaganda car (1926); Aktuelle-Bilder-Centrale, Georg Pahl.

Members of the Weimar government discussed at length whether it was acceptable to allow members of aristocratic associations to become members of Parliament.Footnote 17 In the end, a compromise was reached whereby the princes lost some of their real state that had representative functions but were financially compensated for this effect of the law. However, as Schmitt and other critics of this measure insisted, abrogating rights from nobles set a precedent for future liberal legislation, which meant that under certain circumstances, states could redefine the basic principles of legitimacy in their society.

In his role as a legal counsel to the Weimar constitutional court, Carl Schmitt saw the attempts to inscribe derecognition of nobility into law as setting a dangerous precedent. Comparing the situation with the French Revolution, he argued that with the execution of a king (such as Louis XVI), both the person and the office of the monarch were simultaneously eliminated. This model of reform-by-regicide could not easily be applied to the much larger number of European aristocrats. Unless one wanted to resort to assassinations of individuals with noble names on a mass scale, as had happened in the Soviet Union, this could not be extended to an entire social class within the framework of a liberal constitution.Footnote 18 However, even when laws abolishing the nobility were effective, their effect amounted to the abrogation of the rights of an entire social group, setting a dangerous precedent for depriving other groups of rights in the future. The legal definition of nobles as a ‘group of exception’ who can be expropriated by the state is particularly problematic for liberal legislation which is predicated on the a priori equality of all of the subjects of the law.Footnote 19

The republic was in a dilemma: the existence of aristocratic privilege threatened to derail the new ideal of political equality, but so did the possibility of expropriating nobles by law. The new constitutional assemblies ratified the abolition of the nobility by economic means, removing the prerogatives of primogeniture and title, and barring members of noble corporations from public office.Footnote 20 To give an example of popular attitudes towards the nobility in the German Republic, one K. Jannott, director of the Gothaer life insurance group, wrote to Reich Chancellor von Papen in 1932 that it would serve as ‘a great example’ if the noble members of government demonstratively renounced their nobility to show that they did not value the mere noble name ‘and that even by name they want to be nothing else but plain civic [bürgerlich-schlichte] citizens’. Thus, Jannott continued, the then-current government’s problems with accusations of being a ‘cabinet of Junkers and Barons’ could be decisively dismissed. ‘Noblesse oblige!’, Jannott cited the famous bon mot which bound nobles to serving the state and to honour their ancestors. He used it to incite nobles to give up their nobility in favour of the new ‘obligations’ associated with a republican regime.Footnote 21

Members of aristocratic families as well as those who deposed them had the spectre of Bolshevism before their eyes when they witnessed the revolutions in their regions. In Germany, where twenty-two dynastically ruled communities changed constitution between 1918 and 1921, this was particularly acute, but nowhere as immediately as in Hessen Darmstadt, since the wife of Nicholas II, who had been murdered with him by revolutionaries in Russia, was the sister of Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig. As Grand Duke Ernst Ludwig’s son Georg recalled, the way in which his parents were held captive on 9 November 1918 ‘was a very good imitation of the pictures of the Russian Revolution which we, too, had seen in the illustrated journals, and which apparently had started quite a trend’.Footnote 22

When Ernst Ludwig and his family found that they were not to be physically harmed by the revolutionary movement in Darmstadt but merely expropriated, the ex-Duke wished to bless the new government ‘for constructive work in the best interests of our nation [“Vaterland”]’. Ernst Ludwig wished to thank the new government ‘for the dignified way in which you have steered the wheel of the state under the most difficult circumstances and the often criss-crossing tendencies of the popular will, having managed a most serious transformation in the history of Hesse while avoiding all but the most necessary other hardships’. By ‘other hardships’, Ernst Ludwig was referring to the possibility of having been stripped not just of his status, but also of his life, as communist politicians at the time were calling for the beheading of Louis XVI. The letter was signed simply ‘Ernst Ludwig’, without titles.Footnote 23 In return for giving up political power and a few castles, Ernst Ludwig received financial compensation of 10 million Reichsmark.Footnote 24 However, the German hyperinflation rendered this transaction quasi meaningless.

The purposes behind abolishing the symbols of monarchy and nobility varied amongst the European states: in some cases, it was justified by the foreign heritage of formerly aristocratic families; in others, by their economic supremacy. Generally, the less radical European governments tried to address the problem of aristocratic privilege by making it impossible to combine membership in aristocratic corporations and service to the new states. In 1929, President Stresemann’s government determined that membership in the German Nobles’ Union, an aristocratic corporation, was unacceptable for members of the Reichstag, the ministries, and the army. The republican government of Austria had also passed a law concerning the ‘abolition [Aufhebung] of the nobility, its external privileges and titles awarded as a sign of distinction associated with civil service, profession, or a scientific or artistic capacity’. Ironically, Schmitt was right concerning the danger of the precedent, even though he himself helped bring to power the Nazi government, which went on to use the laws of the Weimar era to create its own mechanisms of derecognition. As Hannah Arent would later note, depriving Jews of citizenship in 1935 involved a multiple process of derecognition.Footnote 25 At the same time, Nazi officials could not decide whether or not the old ideal of the nobility contradicted their own ideology of the Aryan race.

In Austria, too, after 1919, nobles had become ‘German-Austrian citizens’, equal before the law in all respects.Footnote 26 During the parliamentary debates on the future of noble privilege in Austria, the social democrat Karl Leuthner argued that ‘the glorious names of counts and princes are in fact the true pillars of shame in the history of humanity’. His Christian socialist colleague Michael Mayr described the nobility as a ‘dowry of the bygone state system’ and thought it was ‘completely superfluous and obsolete in our democratic times’.Footnote 27 But the law itself made the difference clear: all other citizens could keep their imperial decorations, such as titles of civic or military honour. For example, the anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski got to keep his doctoral distinction sub auspicii imperatoriis granted by Habsburg Emperor Franz Josef.Footnote 28 But citizens with noble names had to give up their imperial distinction and even their very names. In this sense, not all imperial privileges were derecognized, but inheritable privileges associated with the German princes were.

However, perhaps paradoxically, one of the unintended effects of this policy of abolishing aristocratic privilege was the emergence of a group of derecognized nobles who turned their newly obtained ‘classlessness’ and social homelessness into a new source of social capital. Their heightened sense of precarity made them appealing to an international elite in search of its true self, Europeans and non-Europeans. Many of them were jointly attracted to such new ecumenical and post-Christian communities as the Theosophical Society, gurus such as Krishnamurthi and Annie Besant, and the intellectual anthroposophism of the German philosopher Rudolf Steiner.

All these were to serve as instruments for shaping a new ideal of humanity that would build bridges between the proletariat and the old aristocracy, negating the authority of the bourgeois middle class with which the policies of derecognition were mostly associated. As Joseph Schumpeter explained in 1927, much of the transition from the old imperial regime to the modern republic depended on the old elites themselves, on the way in which they embraced giving up power for personality and the degree to which they were able to endorse the ideas of the new elites.Footnote 29 The nobility itself, as he put it, became ‘patrimonialized’, turning into a shared heritage.