By the mid-2010s, the growing distributive crisis – manifest in extreme shortages of land and job opportunities that particularly affected young adults – was progressively undermining the EPRDF’s strategy of coercive distribution as a means of maintaining mass acquiescence. Despite engineering landslide electoral victories in 2010 and 2015, there were growing signs of popular discontent and mass anti-government protests exploded first in 2014, then again in late 2015. Beginning in Oromiya, the protests expanded rapidly in early 2016 first across that region and subsequently to the rest of the country. Government attempts to subdue the protests through outright coercion and new forms of distribution failed. By early 2018, the EPRDF was forced to concede a leadership change that ultimately led to the abandonment of its project of state-led development and the collapse of the ruling coalition.

This chapter provides a detailed account of these events with a view to analysing the causes of the protests, including both the initial sparks that led to the outbreak of protests and the underlying drivers that enabled their spread and sustained them over four years. The argument presented here highlights three main points. First, the distributive crisis meant that large numbers of young adults had escaped the EPRDF’s enmeshment and many were deeply disenchanted with unfulfilled promises of developmental progress and improved living standards. Second, the EPRDF’s response to the protests differed markedly from that of past crises due to emerging divisions within the ruling elite. Rather than a collective threat that required a coherent response, previously subordinate EPRDF factions saw the opportunity to use the protests as political leverage within the ruling coalition. Third, these mass and elite political dynamics were refracted through the prism of ethnic federalism. The result was that mass unrest and elite contestation divided along ethnic lines. Ethnic politicisation would subsequently prove to be a major factor in the EPRDF’s collapse into civil war, with a divided ethno-political elite mobilising mass discontent amongst their ethnic constituencies in the pursuit of their political ambitions.

The analysis uses multiple data sources to build up a picture of the evolving protest movement. In terms of quantitative data, the analysis draws on the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED) (Raleigh et al. Reference Raleigh, Linke, Hegre and Karlsen2010).Footnote 1 While ACLED is the only data source that aims to provide comprehensive coverage of protests, riots and state violence, there are inevitably important limitations. First, ACLED relies heavily on media sources, albeit that events are verified and reviewed by three reviewers. As such, the dataset is shaped by what media outlets consider newsworthy and, in a context in which the Ethiopian state was intentionally restricting reporting and internet access, also what media was able to cover. Second, ACLED is likely to be biased towards urban centres rather than rural areas for several reasons. First, since urban centres have better communications and so protests are more likely to be reported and, second, since the ACLED analysis codes events to the nearest town when the exact location is unknown (Eck Reference Eck2012). Consequently, there is a risk that the detailed geo-location data lead to a false sense of their accuracy. With this in mind, the data are used in the following analysis primarily to examine the broad spatial and temporal spread of the protests, acknowledging the limitations where relevant. Alongside these quantitative data, the discussion returns to several case studies from preceding chapters, namely the Wenji-Shoa sugar plantation (Chapter 5), the periphery of Adama town (Chapter 7) and Kuyyu and Merti wereda (Chapters 8 and 9). These cases provide an indication of the local impacts of the protests, though these cannot, of course, be generalised and these cases were by no means the areas most severely affected.

The chapter begins by documenting the spread of the protests from 2014 to the change in leadership in 2018, before outlining the detailed argument. The analysis concludes by considering competing explanations for these events drawn from the limited existing literature and relevant theory. The analysis considers the strengths and limitations of these contending explanations, and, where data allow, rules these out.

Mass Protests and the Unravelling of EPRDF Control

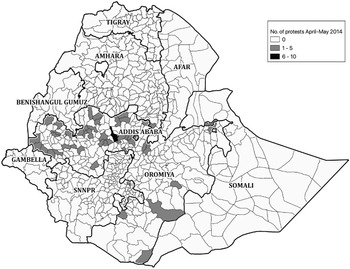

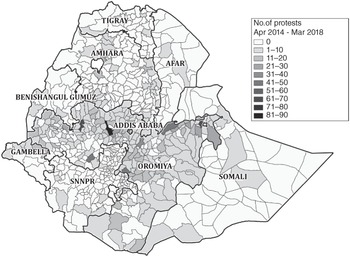

The initial phase of the Oromo protests appears to have begun on the 12 April 2014 with student protests at Jimma University against the Addis Ababa Masterplan. At the same time, on 12–13 April, the OPDO held a workshop on the new Masterplan, resulting in outspoken criticism of the plan from the party’s rank and file that was broadcast on regional state television. Indeed, this broadcast inflamed resentment at land expropriations for urban expansion and agricultural investments, and entrenched the perception that the federal government was driving the expansion of Addis Ababa and the expropriation of Oromo land. Over the following two months, protests swept across western Oromiya, particularly focused on Ambo in West Shewa, and Wellega, although a scattering of protests were held across the region (see Figure 10.1). The security forces violently suppressed demonstrations, with ACLED documenting 52 deaths, and succeeded in putting an end to the protests by the end of May.

Figure 10.1 Map of 2014 protests

Note: data include all events coded as protests, riots and violence against civilians.

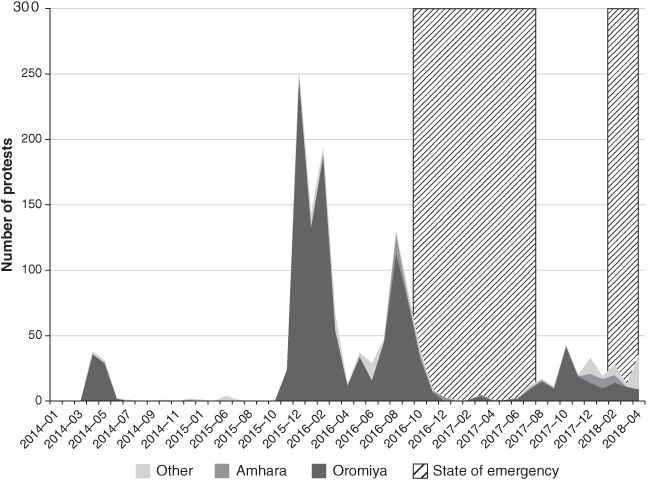

There was a distinct absence of protests during the following 18 months due to the heavy-handed initial response and the stringent measures taken to maintain political order and secure a sweeping victory in the May 2015 federal elections (see Figure 10.2). The narrative that the elections signalled mass EPRDF support was shattered, however, by a much larger wave of protests that swept across the region from 19 November 2015. This second phase began in the town of Ginchi in West Shewa, where the local population protested government plans to expropriate a football pitch and forested area for a new investment project (Fasil and Lemma Reference Fasil and Lemma2015, Burke Reference Burke2017). While resistance to the Addis Ababa Masterplan was initially a key rallying point, protestors’ demands quickly evolved, with the result that very soon the motivation, according to one protestor, was ‘no longer the Addis Abeba Master Plan, but “a better opportunity for all of them”’ (cited in Fasil and Lemma Reference Fasil and Lemma2015). Thanks to the rapid broadening of protestors’ demands, the government’s decision to withdraw the masterplan in mid-January 2016 did little to restore order, with protests continuing for several months.

Figure 10.2 Trend in protests over time

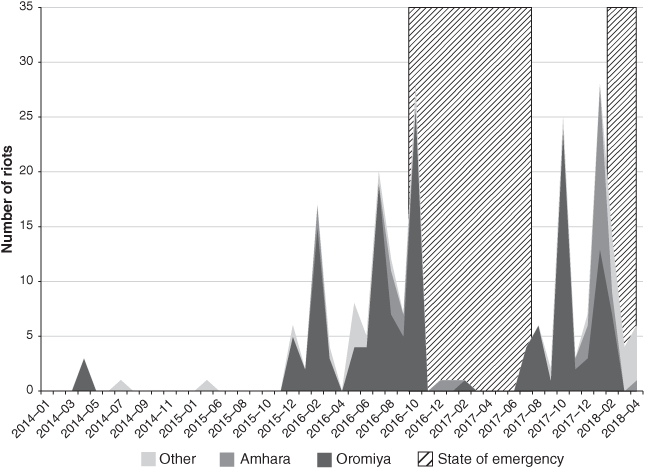

The 2014 and 2015–2016 protests were largely peaceful demonstrations and particularly focused on universities and high schools. ACLED suggest that only a small proportion of demonstrations turned to violence, with rioters targeting government offices, businesses owned by the TPLF-affiliated EFFORT and, in December 2015, two Dutch-owned flower farms (Figures 10.3 and 10.4). However, peaceful protests were met with a violent response from the security forces, resulting in approximately 400 deaths by the end of March 2016 according to ACLED. Once again, the heavy-handed response ultimately contributed to a decline in protests, although this was only a temporary lull.

Figure 10.3 Trend in riots over time

Figure 10.4 Map of 2014–2018 protests

Note: data include all events coded as protests, riots and violence against civilians.

Protests reached another peak in the second half of 2016. The main focus of the protest movement remained Oromiya, with the Grand Oromo Protest on the 6 August 2016 constituting the biggest single day of action. Moreover, this region-wide protest signalled the protestors’ ability to coordinate action rather than just carrying out spontaneous, locally organised protests. However, the crisis deepened at this time with the spread of protests to the second most populous region, Amhara.Footnote 2 Protests began on the 31 July in Gondar, primarily focused on the contested territory of Western Tigray. This area had, for much of recent history, been administered from Gondar as part of Begemder Province, but was placed in Tigray under the federal system due to its predominately Tigrigna-speaking population. Many Amhara claim the area as an integral part of Amhara and believe that the TPLF artificially changed the ethnic balance of the area through the promotion of agricultural investments since the 1990s and resettlement in the mid-2000s (see Chapter 5). The contested status of the territory was an important issue in the 2005 elections and the Welkait Identity and Self-Determination Committee subsequently formed to demand a referendum on three wereda: Tselemt, Tsegede and Welkait.Footnote 3 The arrest of the committee’s leaders sparked protests first in Gondar and subsequently the regional capital, Bahir Dar, and North Wello.

Protests reached another peak in October 2016, following the Irreecha festival that took place on the 2 October. Irreecha is a traditional thanksgiving festival led by the Aba Gadaa and celebrated in Bishoftu which had become an increasingly politically contested terrain in the preceding years (Debele Reference Debele2019). The Mecha and Tulema Association promoted Irreecha as unifying symbol for the Oromo people and a celebration of the Oromo traditional religion (Waqqeeffana). When Mecha and Tulema was banned in 2004 for its role in protests against the relocation of the regional capital to Adama, the Oromiya Regional Bureau of Culture and Tourism took over festival organisation. The Bureau of Culture and Tourism used its authority over the Aba Gadaa to promote a managed form of Oromo ethno-nationalism and to use the event to laud the regime’s developmental achievements (Debele Reference Debele2019).Footnote 4 In 2016, protestors used the large-scale gathering to chant anti-government slogans and security officials caused a stampede in which some 100 people died when they attempted to disperse the crowd with tear gas and, according to some claims, live ammunition (Burke Reference Burke2017).

Outrage at the Irreecha tragedy led to a break from peaceful protests, with diaspora leaders calling for ‘five days of rage’ through attacks on government offices and investment projects (Allo Reference Allo2018, p. 38, Debele Reference Debele2019). Amongst others, rioters attacked textile and juice factories, flower farms and tourist lodges across Oromiya (Maasho Reference Maasho2016), as well as the Wenji-Shoa Sugar plantation, discussed in Chapters 5 and 6.Footnote 5 In attacking these projects, protestors did not just target symbols of the ‘developmental state’, but also sought to deter foreign investors and thereby increase the economic pressure on the government. Protestors also targeted local state officials and their offices. The period from 2015 to 2018 was described by the chairman of Dhenkore Dhenku kebele, where land was expropriated for Adama Industrial Park and other infrastructure projects (see Chapter 7), as ‘a time of wild fire’ in which youth protestors burned down the Farmer Training Centre and the health post. Indeed, the situation was so bad that for three years the kebele administration ‘feared to enter the kebele during the day’, instead resorting to night-time raids to arrest suspected protestors.Footnote 6

With the situation rapidly deteriorating the Federal Government declared a State of Emergency in October for six months, which was subsequently extended for a further four months, finally ending on 4 August 2017. The State of Emergency created a Command Post which took control of all federal and regional security forces, and the authority to ban all public demonstrations, shut down communications, arrest individuals without warrant, impose curfews and reorganise state administrations. This State of Emergency resulted in a sharp reduction in protests and riots, and brought back some degree of stability (Figures 10.2 and 10.3).

During this period, a new challenge emerged, however, with the outbreak of widespread violence around the long disputed Oromiya–Somali border. As in many other places, the complexities and fluidity of ethnic identity and the mobility of pastoralists constitute a poor fit for the rigid territorial principles of ethnic federalism. Referenda were held in 2004 in 422 kebele along the border with 323 kebele opting to join Oromiya, including many that had previously been in Somali region (Adugna Reference Adugna2011, Kefale Reference Kefale2013). From early 2017, the Somali regional government seized on instability in Oromiya to attack the Oromo population in these areas, resulting in many deaths and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people. For this purpose, the Somali regional government used its Liyu police force that had been built up over the previous decade with federal support to carry out a counter-insurgency campaign against the ONLF. Consequently, many Oromo suspected that the TPLF-dominated military leadership was using the Liyu police to attack the Oromo (e.g. Hassen Hussein Reference Hassen Hussein2017, Lefort Reference Lefort2017).

Even before the State of Emergency ended, further protests broke out in June and July 2017, triggered by government actions that seem particularly obtuse in light of the precarious stability. In June 2017, the Oromiya regional government implemented a change in the order of the letters in the Afaan Oromo alphabet (qubee) taught in schools without any consultation with Oromo society (OPride Staff 2017). Based on a decision taken more than a year before, the move symbolised the EPRDF’s standard top-down practice and triggered further protests in Ambo. Shortly afterwards, the government created further resentment when it imposed major tax increases on small businesses resulting in protests during July and August across Addis Ababa and Oromiya, ultimately forcing the government to scrap its plans (Abera Reference Abera2017, Davison Reference Davison2017). Moreover, the end of the State of Emergency in early August 2017 almost immediately led to a resurgence of protests and riots across Oromiya and Amhara. In particular, a five-day strike called by the opposition Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC) on 23–27 August 2017 brought the region to a standstill and blocked all roads into Addis Ababa.

Initial protests in 2014 and 2015 were dominated by students. However, as the movement gathered pace, the protests drew in a broader range of young people, both those in and out of education and particularly the unemployed (Abebe Reference Abebe2020). The main actors in the protests came to be known as the qeerroo, an Afaan Oromo term meaning an unmarried young man, approximately 20–36 (Østebø Reference Østebø2020b, discussed in more detail below). While young men were at the forefront, young women – known as qarree – also actively participated (Debele Reference Debele2019). Though some people of all ages participated in the protests, the driving force of the movement was undoubtedly the youth population, in particular, the generation of young people that had slipped through the net of the EPRDF’s strategy of enmeshment as a result of the acute shortage of land and employment.

The government’s response to this deepening crisis sought to employ a similar combination of internal reform, coercion and distribution that had achieved political stability and economic growth following the ‘Armageddons’ of the early 2000s. The government’s initial response was to cast the protestors as ‘an organized and armed terrorist force’ financed by Egypt and Eritrea (Getachew Reda, Minister of Communication, cited in HRW 2015, France 24 2016). This ‘terrorist’ threat was, in turn, used to justify violence and mass repression of largely peaceful protests. Police also arrested the leadership of the OFC, one of the few political parties that had continued to engage in the stacked electoral process. The government limited protestors’ ability to coordinate their activities, shutting down internet and phone services, which remained under the exclusive control of the state Ethiopian Telecommunications Corporation.

The TPLF’s old guard had conducted a study tour in 2014 in rural Tigray, which highlighted widespread grievances amongst the population. Consequently, this group proposed a ‘Deep Renewal’ of the EPRDF – mimicking the tehadso carried out in the early 2000s – to root out corruption and improve party discipline (Lefort Reference Lefort2015). Deep Renewal was announced at the EPRDF Congress in August 2015 (Berhane Reference Berhane2016) and government officials frequently admitted the failings of the party, including corruption, along with promises of reform (Getachew Reda, in EBC 2016). Protests in November 2015 gave added impetus to Deep Renewal. However, from the outside at least, the resulting changes in the federal government appeared modest. More substantive was the removal of the OPDO leadership in October 2016 and the installation of apparent reformists Lemma Megersa as President and Abiy Ahmed as his deputy.

The government also expanded forms of mass distribution that fit the EPRDF’s productivist ideology in an attempt to repair the holes in its strategy of enmeshment. As discussed in Chapter 8, the Urban Productive Safety Net Programme, though initiated in response to earlier inflation, finally began implementation in 2015/16, as the protests exploded. The Ministry of Urban Development responsible immediately formulated proposals for a large-scale expansion of the UPSNP in direct response to the expanding protests. The government also sought to extend its support for MSEs that had formed the bedrock of its support for young people lacking access to land and employment. The 2017 budget announced a Youth Revolving Fund in which the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia would provide 10 billion birr to be distributed through the party-affiliated microfinance institutions. Given the political importance of the Fund, the supposedly independent microfinance institutions came under strong political pressure to issue low interest loans, regardless of the technical criteria used to assess borrowers’ creditworthiness.Footnote 7 Among those who received loans were twenty-five qeerroo organisers in Adama who had been imprisoned for their role in the protests and were immediately given one million birr on their release to start a cattle-fattening business.Footnote 8 Moreover, the criteria for distributing funds were shaped by political pressures. For example, Dodota wereda, which had been comparatively peaceful, received only 4.6 million birr to distribute to youth in the wereda whereas neighbouring Robe wereda, where the protests had been particularly destructive, targeting banks and government offices, received 15 million birr. The unfortunate lesson drawn by qeerroo in Dodota was that ‘the more violent you are the higher the budget you will get’.Footnote 9

The government also sought to address the grievances related to land administration, which had provoked the initial protests. In late 2016, the federal Agricultural Investment Land Administration Agency (AILAA), created to centralise control over large-scale and foreign agricultural investments, was disbanded and the authority to allocate land to investors was returned to regional administrations. The new Oromiya regional government also cancelled hundreds of underperforming land leases and redistributed some land to groups of young people (Fekade and Lemma Reference Fekade and Lemma2018). Furthermore, in October 2017, Prime Minister Hailemariam Dessalegn established the National Integrated Land Use Policy Directorate under the Prime Minister’s Office. This Directorate was given three years to propose an organisational structure for land administration and to formulate a National Land Use Policy to guide city expansion and industrial zoning, amongst other land uses.Footnote 10

On this occasion, however, the combination of coercion and distribution was unable to stem the tide of resistance. Protests and riots continued, finally forcing the EPRDF into more substantive reforms. On the 15 January 2018, the government announced the release of some 6,000 political prisoners, including the OFC leadership, to great public celebration. By this time, however, anything less than regime change was insufficient to satisfy protestors. A series of protests across Oromiya and in the periphery of Addis Ababa effectively blockaded the capital from 12–13 February, and two days later, Prime Minister Hailemariam Dessalegn resigned as Prime Minister and EPRDF chair, triggering a leadership contest that was eventually won by the OPDO’s Abiy Ahmed, who took office as prime minister on the 2 April.

Abiy’s ascent to the premiership constitutes the beginning of the end of the EPRDF’s authoritarian state-led development project that originated in the TPLF’s revolutionary struggle. Abiy’s selection symbolised the TPLF’s loss of power within the ruling coalition and the ascent of a different EPRDF faction without ties to the revolutionary movement. The EPRDF leader was selected by the EPRDF Council in which each of the four parties had equal vote shares. The key question was whether the EPRDF would select a new leader from long-standing senior party figures – most likely Demeke Mekonnen of ANDM or Shiferaw Shigute of SEPDM – or from the reformist OPDO. Lemma Megersa, Oromiya president and the most popular Oromo politician, stood aside since he was not a member of parliament, paving the way for his deputy Abiy Ahmed. Though the votes in the leadership contest were not made public, the TPLF was widely believed to have opposed the OPDO leadership, instead nominating Demeke. However, Demeke refused the nomination, opting to remain deputy Prime Minister and throwing his support behind Abiy Ahmed. The result was that the TPLF and some SEPDM officials supported Shiferaw Shigute but Abiy Ahmed won comfortably based on the support of the OPDO, ANDM and many in SEPDM (Fekade and Lemma Reference Fekade and Lemma2018, Fisher and Gebrewahd Reference Fisher and Gebrewahd2018). As discussed in Chapter 11, Abiy’s subsequent premiership saw the TPLF steadily marginalised within the federal government, while the new administration, with strong support of western donors, announced a series of reforms to liberalise the economy, marking a break from the EPRDF’s ‘developmental state’.

Explaining Mass Protests and the Collapse of the EPRDF

The protest movement that ultimately led to the EPRDF’s collapse was the result of multiple, intersecting processes. The argument put forward here is that the key factors were the mass distributive crisis that meant large numbers of young adults escaped the EPRDF’s strategy of enmeshment; the fragmentation of the ruling elite, at least partly the result of a divided response to mass protests; and the federal system and the politicisation of ethnicity, which shaped the form of both mass protests and elite factionalism. Each of these is considered in turn.

Distributive Crisis and Mass Protests

The argument put forward in the preceding chapters is that the failings of the government’s development strategy in the context of rapid population growth eroded the strategy of coercive distribution that the EPRDF had used to maintain political order. When the EPRDF came to power, it sought to secure popular acquiescence through a strategy of coercive distribution that established direct ties of dependence with individual households. Initially, distribution focused on state-owned land and agricultural inputs. From an early stage, the government recognised that rapid population growth would inevitably erode the effectiveness of this political strategy. ADLI was therefore framed as a race against population growth to achieve structural transformation, utilising an agrarian surplus to finance industrial employment creation that would absorb rural surplus labour and thereby replace access to land as the key distributive resource. ADLI would therefore combine productivity growth, improving livelihoods and equality in the short-term, and structural transformation and the maintenance of political order in the long run.

The political crises of the early 2000s highlighted ADLI’s limitations and forced a re-think in the government’s strategy. As part of the ‘developmental state’, there was a shift in agricultural policy, which increasingly prioritised productivity growth and commercialisation over equality. While government statistics show a sharp subsequent rise in agricultural productivity, the individualisation of land tenure that sought to promote agricultural productivity effectively excluded a generation of young adults from access to an agricultural livelihood – previously the key form of distribution. Alongside population growth – the main cause of land shortages – key projects of the ‘developmental state’ that sought to accelerate economic growth through the promotion of agricultural and industrial investments, infrastructure projects and urban expansion enhanced competition for land, expropriating existing landholders with minimal compensation. In contrast to ADLI, which sought to protect the peasantry from displacement, the ‘developmental state’ necessitated the exit of large numbers of people from the agricultural sector in order to raise productivity.

The incorporation of this surplus labour through industrial employment creation was therefore a political imperative. Industrial policy focused first on domestic capitalists and, subsequently, foreign investment in state industrial parks, yet delivered mixed results. On the one hand, the government delivered rapid and sustained economic growth over a period of more than a decade and this growth translated into major improvements in almost all social indicators. On the other hand, however, the strategy, in the context of rapid population growth and the constraints of the global economy, resulted in a growing distributive crisis along generational lines, with large numbers of increasingly well-educated young people lacking access to land and a realistic possibility of an agricultural livelihood, but also lacking off-farm employment opportunities in line with rising expectations. As shown in Chapter 8, a combination of ideological resistance to ‘welfare dependency’ and resource constraints meant that the government remained committed to the belief that the only solution was labour-intensive growth, with more direct forms of distribution, such as social transfers, woefully insufficient to address the growing crisis. The result was that the government’s strategy of coercive distribution had less and less to offer a generation of educated young adults with rising aspirations. The hole in the government’s strategy of enmeshment was all the more visible in Oromiya, where the OPDO had long lacked local legitimacy and party discipline.

The results of this distributive crisis are best demonstrated by a series of ethnographic studies focused on young adults and children. A consistent theme of the work of Abebe (Reference Abebe2020), Mains (Reference Mains2012) and Di Nunzio (Reference Di Nunzio2019) carried out in different parts of Oromiya and Addis Ababa is the resentment, despair and frustration of young people – particularly young men – bypassed by rapid growth and lacking opportunities either in agriculture or beyond. In this regard, there is a clear resonance with Gurr’s (Reference Gurr1970) theory of relative deprivation, in which the gap between people’s expectations and the state’s ability to meet those expectations is proposed as a central driver of rebellion. In Ethiopia, rising educational attainment led to the expectation of improved economic opportunities, yet for too many the ‘developmental state’ failed to deliver. This distributive crisis translated into a major political crisis in part because the government had so visibly taken responsibility for the distribution of land, jobs and most other services as part of its strategy of coercive distribution. Consequently, the inability to provide access to land and jobs was a deeply political issue that inevitably led to resentment of the party-state that had failed to deliver.

A number of observers have pointed to state expropriation of smallholders to make way for agricultural investments, urban expansion and infrastructure development as major causes of the protests (Rahmato Reference Rahmato and Cochrane2019). While the injustice of displacement was undoubtedly an important spark for the protests, state expropriation was by no means the main cause of the distributive crisis. Rather, land expropriation was just the most visible expression of the inequality and injustice of the ‘developmental state’. The rapid spread of protests across Oromiya and elsewhere, however, clearly show that additional factors – beyond the grievances related to individual investments or infrastructure projects – drove the broad spread of resistance. Indeed, throughout this period access to land and employment remained central themes of the protest movement, with slogans such as ‘lafti keenya lafee keenya’ (our lands are our bones) a regular chant of protestors (Abebe Reference Abebe2020, p. 9). Moreover, for the most part, it was not expropriated middle-aged farmers that drove the protests, but rather their children and a generation of young, relatively well-educated adults with few economic opportunities in agriculture or outside who had escaped the EPRDF’s enmeshment.

Elite Fragmentation and Collapse of Party-State Infrastructural Power

Existing theory clearly shows that while mass protests grab the headlines, regime collapse requires not just mass opposition, but also elite divisions. These divisions erode the state’s ability to provide a coordinated response and raise the possibility that elite factions might align with protestors to support regime change (Skocpol Reference Skocpol1979, O’Donnell et al. Reference O’Donnell, Schmitter and Whitehead1986, Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman1997, Geddes Reference Geddes1999, Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007, Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010, Slater Reference Slater2010). This general point is evident in the EPRDF’s collapse and the contrasting response to anti-government protests in 2005 and 2014–2018. As discussed in Chapter 4, the 2001 TPLF split centralised power around Meles Zenawi who installed regional leaders that depended on him for their power. The result was that the food crisis and urban protests in 2002–2005 were collective threats to the political elite that necessitated a coherent and decisive response. In sharp contrast, mass protests from 2014 intensified emerging divisions within the ruling elite, undermining the government’s response to the crisis and leading, ultimately, to a catastrophic fallout between contending factions.

The EPRDF had always been a somewhat unstable coalition of a revolutionary party – the TPLF – characterised by strong ideological commitment and party discipline, and a collection of fragmented parties formed by creating or co-opting ethnic leaders. Elite cohesion was maintained after 2001 not through party institutionalisation, but Meles’ centralisation of power. Leadership succession and generational turnover is invariably a key test of organisational strength (Huntington Reference Huntington1968, Brownlee Reference Brownlee2007, Geddes et al. Reference Geddes, Wright, Wright and Frantz2018). Indeed, for the EPRDF Meles’ 2012 death presented a fundamental challenge. Prior to his death, Meles had begun a process of generational change in the EPRDF leadership with key figures from the civil war and founding leaders of many parties retiring to make way for a new generation. Foremost amongst this new set of leaders was Hailemariam Dessalegn, Meles’ apparent chosen successor. A number of key figures retired in this period including Seyoum Mesfin and Abay Tsehaye, founding members of the TPLF, Addisu Legesse and Tefera Walwa from ANDM, and Girma Birru and Shiferaw Jarso of the OPDO. Moreover, the remainder of the founding generation, including Meles, was expected to stand down before 2015.

Long-standing tensions regarding the subordination of non-TPLF parties within the coalition and this generational turnover became increasingly apparent following Meles Zenawi’s death. An immediate succession struggle was avoided by installing Hailemariam Dessalegn as Prime Minister. Hailemariam, from the small Wolayita ethnic group, a minority protestant denomination, and the fragmented and weak SEPDM, was a compromise candidate between the increasingly assertive ANDM and OPDO, and the once dominant TPLF. However, the compromise undermined elite cohesion and federal authority, with regional administrations acting increasingly autonomously. Indeed, this weakness was acknowledged by Hailemariam soon after leaving office,

Since Meles, there has been a fierce power struggle within the party which I was able to navigate through, as I was considered a neutral person – between those who considered the TPLF to be the dominant party and those in the other three parties which wanted to end this dominance.

The growing power struggle within the coalition was not just between parties, however, but also a generational division between the old guard and a younger generation (Lefort Reference Lefort2012b, Saaddo Reference Saaddo2016, Fisher and Gebrewahd Reference Fisher and Gebrewahd2018). Despite the plan for generational change, most political leaders and economic advisors from the past two decades remained in influential advisory or party leadership positions. Again, this point was clearly acknowledged, in retrospect, by Hailemariam,

Younger leaders, including myself, interpreted this [Meles’ plan] as being the need for older leaders to give over power. This created a clash with the older guys, who were communist-minded, in both ideological and generational terms. This caused instability in the party as we tried to reduce the influence of the old guard, who were particularly influential in the TPLF [and] ANDM.

These divisions forced a return to the collective leadership that had prevailed before Meles’ centralisation of power in 2001, as well as a considerable slowdown in decision making in the federal government and growing regional autonomy (Lefort Reference Lefort2014). However, tensions did not lead to a breakdown of the ruling coalition until mass protests magnified these emerging divisions.

The first clear indication of problems came at the presentation of the Addis Ababa masterplan in 2014. The masterplan was jointly approved by the Oromiya regional government and the Addis Ababa administration, and contained forwards written by Oromiya regional president and OPDO chairman, Alemayehu Atomsa, and the Oromo Mayor of Addis, Kuma Demeksa, the original leader of the OPDO. The planning process also reportedly had the support of senior OPDO figures such as Abdulaziz Mohammed, deputy regional president and Aster Mamo, deputy prime minister (Weldeghebrael Reference Weldeghebrael2014). Yet, the presentation of the plan to OPDO officials in Adama in April 2014 was vigorously resisted by the rank and file (Yibeltal Reference Yibeltal2014). Takele Uma, then head of the regional Land Administration, was broadcast on Oromiya Regional television criticising the plan in a remarkable break from the principles of democratic centralism that should ensure party discipline,

The issue of Addis Ababa and surrounding Oromia region is not a question of towns; it is a question of identity. When we speak of identity, there are fundamental steps we ought to take to ensure that the plan would incorporate and develop the surrounding towns while also protecting Oromo’s economic, political, and historical rights … We don’t want a city that pushes out farmers and their children but one that accepts and develops with them … more importantly, we don’t want a master plan developed by one party and pushed down our throats.

However, senior OPDO officials did not immediately seize on this resistance from within the party and the initial mass protests that followed. Rather, expanding protests magnified existing fractures in the OPDO and EPRDF, undermining the government’s response and ultimately leading to a major internal power struggle. As the protests spread and intensified, they contributed first to leadership change within the OPDO and the collapse of the party-state infrastructural power that was vital to the maintenance of political order. OPDO and ANDM leaders subsequently encouraged protestors, attempting to ride the wave of protests in order to challenge TPLF supremacy.

These changes are most evident in the OPDO, which in October 2016 was forced into a change in leadership in which the old guard – widely seen as subservient to the EPRDF and lacking local legitimacy – was replaced by a younger generation resistant to the masterplan and demanding a stronger role in the EPRDF. An important theme of the early protests focused on the OPDO’s illegitimacy, subservience and corruption (Yibeltal and Waldyes Reference Yibeltal and Waldyes2016). Indeed, the leadership change was regarded as the first time that the OPDO had itself initiated leadership change, rather than at the EPRDF’s instruction (Fekade and Lemma Reference Fekade and Lemma2018). Regional President, Muktar Kedir,Footnote 13 and deputy, Aster Mamo, were replaced with Lemma Megersa and Abiy Ahmed. Both Lemma and Abiy were long-standing OPDO members and, in Abiy’s case, had held senior positions within the security services. Nonetheless, Team Lemma – as the duo and colleagues became known – rose to prominence due to their stated opposition to the masterplan and support of the protestors’ demands. For example, in November 2015, when Speaker of the Oromiya parliament, Lemma stated that,

As for the Integrated Addis Ababa Master Plan, even if it is for the benefit of the Oromo people; even if it were to pour gold on us, it will not be implemented if rejected by the public; it will not be implemented.

This rhetoric continued once Lemma took office, with frequent statements expressing solidarity with the protestors and, at times, opposition to the federal government and, implicitly, TPLF dominance.

Why persist with costly street protests when we have made your demands our own? If we failed to deliver using existing legal and institutional mechanisms, I and all of us here will join you in the protests.

I took the oath of office to serve my people not shadowy elements hiding behind the cover of strict adherence to party dogma.

Lemma and the new leadership achieved a remarkably rapid turnaround in popular perceptions of the OPDO, from illegitimate and corrupt to being a legitimate voice of Oromo opposition (Hassen and Ademo Reference Hassen and Ademo2017).Footnote 14 A less dramatic but nonetheless important shift in the ANDM leadership also took place in the years after Meles’ death. From 2008 onwards, key leaders such as Addisu Legesse, Tefera Walwa and Bereket Simon retired or moved out of formal positions of power. This enabled the rise of a new generation that was more assertive and resistant to what many Amhara consider to be the EPRDF’s frequent attempts to scapegoat Amhara chauvinism for all of Ethiopia’s failings.

There are strong indications that from at least 2016 onwards, some senior OPDO and ANDM leaders fuelled the expanding protests. According to Juneydi Saaddo, a former President of Oromiya (2001–2005), senior members of the ODPO and ANDM ‘started actively colluding with opposition parties and activists’ (Saaddo Reference Saaddo2016), while a document presented to the National Security Council in November 2017 acknowledged the role of unspecified members of the ruling party in stoking protests (Addisstandard 2017). More specifically, ANDM leaders were directly implicated in the August 2016 Welkait protests (Davison Reference Davison2016, Lefort Reference Lefort2016).

These divisions presented a challenge to the security services’ ability to suppress the protests. Regional police are required to speak Afaan Oromo and are therefore almost exclusively Oromo. In contrast, federal police are required to speak Amharic and are recruited nationally, making them largely non-Oromo. Federal police can be sent to a region when a situation exceeds the regional police’s capacity and on request by regional authorities (Arriola Reference Arriola2013). Regional police attended to the initial protests, but as protests spread and the federal government sought to crack down in December 2015, it drafted in the federal police, military and even apparently the Somali Liyu police in parts of eastern Oromiya (HRW 2016). The post-2016 OPDO leadership took an explicit stand against federal intervention, attempting to prosecute members of the federal armed forces that had killed peaceful protestors and, in December 2017, rejecting the federal intervention that had not been requested by the regional government (OPride 2017).Footnote 15

Factional struggles and leadership change in the OPDO also accelerated the collapse of party-state infrastructural power after 2015, weakening structures which already had limited influence over younger generations. Respondents in Kuyyu and Merti reported a sharp decline in the development teams and system of performance evaluation from 2015. Respondents across state levels from the regional government to the kebele also noted a sharp decline in the pressure from higher levels of the party-state – distracted by elite political wrangling and leadership change – to mobilise the population. As one regional government official noted in early 2018,

At the moment there are big challenges. The instability, it holds your attention, it is hard to focus on development.Footnote 16

The result in the research sites was a significant reduction in what had been regular performance evaluations or gim gema for kebele officials and sub-kebele organisations.Footnote 17 Moreover, there was no attempt to conduct the annual assessment of model farmers or households for several years,Footnote 18 while there was no hint of the democratic centralism and discipline that previously underpinned the development team structures,

Nothing happens to anyone who does not follow the messages that come from 1-to-5 groups. If you like you apply it if you don’t like you can leave it. It is a voluntary.Footnote 19

Moreover, local leaders and the general population were inspired by the protests and the new OPDO leadership to refuse to acquiesce to the demands made by the party-state hierarchy. Several health extension workers, for example, took the previously unthinkable action of cancelling their OPDO membership.Footnote 20 Indeed, one male development team leader argued,

Previously if you speak or criticise the government you will be labelled as OLF and you might end up in prison. So people were living in fear. But after Lemma became president that fear was broken.Footnote 21

According to a male focus group participant,

there is a hope these days … Because of the change we are seeing at the top. Because of this change we do not fear to express our views and dissents anymore. Previously if you speak against the kebele cabinet they label you as OLF, they say you have ‘anti-government view’. The kebele militia including this guy [pointing to one of the FGD participants] used to harass you. Now that has decreased.Footnote 22

The growing factional divisions were therefore an important additional factor in the spread of the protests from about 2016 onwards, undermining the infrastructure of party-state control, and inspiring resistance to the federal government. The growing assertiveness of ANDM and OPDO leaders ultimately led them to coordinate activities to demand change within the ruling coalition. This alliance was evident in December 2017 when the two parties announced that their MPs would boycott parliament in protest at state violence (Hassen Hussein Reference Hassen Hussein2017). The ANDM-OPDO alliance was also believed to have been a key factor in forcing Hailemariam to resign and, ultimately, the selection of Abiy Ahmed as his replacement. Political parties can be effective ‘vehicles for elite collective action’ that underpin authoritarian rule (Slater Reference Slater2010, p. 50). In post-Meles Ethiopia, in contrast, the EPRDF became the battleground for bitterly fought factional struggles, in which mass protests magnified emerging fractures within the ruling elite and were used by political elites as leverage to shift the balance of power in the coalition.

Federalism and the Politicisation of Ethnicity

Distributive crisis and elite fragmentation were both vital drivers of the protests and the collapse of the ruling coalition. However, the federal system and the growing politicisation of ethnicity fundamentally shaped the form that the protests and conflict took, with the protest movement and elite factionalisation organised along ethnic lines.

When the EPRDF came to power in 1991, ethnic self-identification was not ubiquitous. The TPLF and, to some degree, OLF had promoted ethno-nationalism as a means of popular mobilisation in their home regions. However, the creation of political units for ethnic self-administration and political parties to represent ethnic groups extended the principle of self-rule to many groups which had not demanded it. As one observer noted,

The Ethiopian constitution reads as if someone attempted simply to deduce the appropriate structure of the federal state from a set of first principles, in conjunction with a census of ethno-linguistic groups. One result of this is that federal autonomy has been accorded to ethnic groups that had not in fact mobilized politically for it, and indeed may not have identified themselves as ‘nations’ at all.

Federalism was therefore not a neutral act of recognising existing ethnic groups and settlement patterns. Rather federalism took a range of social markers, notably language, and politicised them, territorialising ethnicity and making a singular ethnic identity the central reference point in individuals’ engagement with the state and access to the resources it provided. In doing so, federalism entrenched previously fluid and complex ethnic boundaries, and in some cases created ethnic divisions where none previously existed.

Wimmer’s (Reference Wimmer2018) work highlights three main factors that underpin nation-building and defuse inter-ethnic tensions. The first is rooted in histories of state formation, with common spoken and written language underpinning exchange relations between actors and groups, while linguistic diversity ‘slows down nation building’ (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2018, p. 30).Footnote 24 Second, nation-building depends on states’ ability to provide public goods and services. Where high capacity states deliver valued services, individuals of any ethnic background are more likely to engage with the state and establish exchange relations, while in the absence of broad-based provision, ‘alliance networks will compartmentalize along ethnic divides’ (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2018, p. 28). Finally, where voluntary organisations reach across ethnic divides before the transition to a nation state, political leaders use these networks to build a multi-ethnic political class, de-politicising ethnicity. In contrast, where elite networks form along ethnic lines, ‘political competition pitted ethnic community against each other, and ethnic identities became more politically salient than the imagined community of the nation’ (Wimmer Reference Wimmer2018, pp. 65–66).

Ethiopia’s history of state formation, discussed in Chapter 3, provided a problematic legacy for nation-building. The Imperial conquest of southern Ethiopia in the late nineteenth century and abortive attempts at forging a unified national identity based on the Amharic language and the Orthodox Church resulted in a country with enormous linguistic diversity, and an Imperial state incapable of public goods provision. Moreover, attempts to project Imperial authority into the newly conquered south through land grants to northern settlers resulted in inter-ethnic exploitation and eliminated any possibility of multi-ethnic elite networks. However, the EPRDF’s creation of the federal system in the 1990s – inspired by Lenin and Stalin’s approach to the nationalities question in the Soviet Union – could hardly have done more to entrench ethnic divisions and undermine national unity. The move to use local languages for primary education and government administration certainly had the positive effect of expanding access to the state for the majority of non-Amharic speakers. Yet, the unfortunate result was also to entrench linguistic divisions, with even highly educated members of different ethnic groups lacking a common language.Footnote 25

In some respects, the EPRDF’s focus on mass distribution does resonate with the importance of public goods provision. As argued throughout this book, the EPRDF sought to tie people to the regime through the generation and distribution of key resources, from land and jobs to education and health. Despite major expansion of access, any positive effect of service delivery on national integration was muted by several factors, however. First, goods and services were distributed not by a neutral national authority, but through what was widely considered to be a Tigrayan-dominated federal government working through ethnically defined regional administrations. This leads to the possibility that exchange relationships are formed primarily between ethno-regional elites and their ethnic constituencies, not necessarily the federal government. Second, federalism itself raises problematic questions regarding the links between ethnicity and resource access, and thereby the rights of national citizenship. Regional borders were drawn to maximise ethnic homogeneity within regions and ethnic heterogeneity between regions to enable self-administration of an ethnic group’s territory and resources. The strong implication of the federal system, therefore, is that each ethnic group has its own region and that within that region ethnic insiders have a greater claim to resources than ethnic outsiders, undermining any claims associated with Ethiopian citizenship.Footnote 26

The ethno-politicisation of resource access is particularly evident with respect to land. As Boone’s (Reference Boone2014, p. 68) work has demonstrated, land tenure regimes define patterns of political authority, territorial jurisdiction and ‘boundaries of membership in a political community’ and, in doing so, shape the pattern of distributive conflicts. The result is that land tenure regimes rooted in divisions between insiders and outsiders translate into ‘conflict that runs along ethnic lines’ (Boone Reference Boone2014, pp. 322–323). The territorial implications of federalism therefore translated into distributive conflicts being framed in ethnic, rather than class or generational terms. This process is particularly visible with respect to the inter-ethnic competition for ownership of ethnically diverse cities under federalism, discussed in Chapter 7. Under federalism, protestors interpreted the state-driven expansion of multi-ethnic Addis Ababa into surrounding Oromiya as a prime example of a broader pattern of ethnic oppression rather than the outcome of population growth and urban economic development. Similarly, the expropriation of peasant farmers to make way for agricultural investments and infrastructure projects were often interpreted not in class terms, but as the actions of the TPLF-dominated federal government that exploits and marginalises ethnic insiders to the advantage of ethnic outsiders (Ethiopian or foreign). The EPRDF’s reliance on party-owned, military and politically affiliated companies for this purpose inevitably heightened the sense of injustice and perception of political and ethnic favouritism. Finally, widespread land shortages under a federal system that prioritises ethnic insiders has led to inter-ethnic conflict over territory. The most visible recent examples include disputes over Welkait and Raya between Tigray and Amhara regions, and along the Oromiya–Somali border, both of which directly contributed to the protests. In the context of federalism, therefore, resource shortages are interpreted primarily in terms of insider-outsider claims between ethnic groups, rather than demographic pressures and the demands of state-sponsored capital accumulation.

Finally, far from building new multi-ethnic organisations and networks that might de-politicise ethnicity, federalism further entrenched intra-ethnic elite networks and inter-ethnic elite divisions. Civil society – long repressed under past administrations – was constrained under the EPRDF that considered any independent organisation to be a threat to its authority. As such, the main organisation that could plausibly have provided such a unifying role was the ruling party itself. However, the EPRDF was created not as a multi-ethnic national party, but a coalition of ethnically defined parties.Footnote 27 Ethnic federalism provides powerful incentives for ethnic parties to adopt an ethno-nationalist message to mobilise mass support with which to contest power at the centre. Maintaining cohesion within the EPRDF coalition was always something of a challenge. However, the dominance of the TPLF in the 1990s and then Meles after 2001, and the subordination of other factions, constrained regional leaders who were expected to maintain order and implement federal plans within their regions. Over time, however, non-Tigrayan junior partners accumulated grievances, from ANDM’s resentment at Amhara chauvinism being blamed for all of Ethiopia’s problems to the OPDO’s perception that the EPRDF represented the continuation of past oppression by northern ethnic groups, rather than real self-determination. Following Meles’ death in 2012, central control weakened considerably with the result that EPRDF parties increasingly sought to build popular legitimacy through ethnic mass mobilisation, in doing so entrenching inter-ethnic divisions. The OPDO and ANDM support for popular protests from 2016 onwards was the result.

The protest movements were fundamentally shaped by the federal system and the politicisation of ethnicity. Protests began in opposition to what was perceived as the TPLF-dominated federal government’s attempt to expand Addis Ababa into Oromiya and subsequently morphed into broader protests against the ethnically structured state. In such circumstances, it is unsurprising that they took the form of ethnic protests.Footnote 28 The protests quickly became known as the Oromo protests and were inseparable from the qeerroo and its association with Oromo nationalism. According to some accounts, at least, the qeerroo were cast as the youth generation of the Oromo Gadaa system (Hamza n.d.). Not only were the qeerroo young men, they were framed as part of the qubee generation, the first to be educated using the Afaan Oromo alphabet introduced to formal education in 1992 (Debele Reference Debele2019, Abebe Reference Abebe2020). Oromo nationalist songs, such as those of Hacaalu Hundessa, moreover, quickly became the soundtrack of the protest movement.Footnote 29 As such, the protestors were immediately cast not just as a generation of relatively well-educated young men with rising aspirations, but also as self-identifying Oromo. Protestors were the product of the EPRDF’s Ethiopia in terms of education and ethno-nationalism, yet lacking the economic opportunities that the government had promised. As the protests spread, they were primarily sparked by local, ethnically framed grievances, such as the Welkait dispute for Amhara, and entailed not the formation of a nationwide youth movement, but separate ethno-nationalist movements. Even when the Fano – the Amhara youth movement that drove protests there – expressed their support and solidarity with Oromo protestors in 2016, there was never any question that the two groups might merge to form a multi-ethnic movement. Instead, the aim was to coordinate distinct ethnic movements, which – temporarily – had the shared objective of overthrowing the TPLF-dominated EPRDF.

The result was that a generation of young adults with rising expectations but few economic opportunities either in agriculture or outside escaped the EPRDF’s strategy of enmeshment and mobilised along ethnic lines. Within an increasingly fragmented ruling coalition, these ethnic-based protests provided a political opportunity for the previously subordinate leaders of parties representing the largest ethnic groups to displace the TPLF and claim a greater share of power within the federal government. This factionalism led to the EPRDF’s collapse.

Competing Theories of Protest and Regime Collapse

In order to strengthen confidence in the argument presented above, it is important to consider the strengths and limitations of alternative explanations for the EPRDF’s collapse (George and Bennett Reference George and Bennett2004, Bennett and Checkel Reference Bennett and Checkel2014). Some of these have been proposed by a growing body of work that focuses on the protests, while other possible explanations can be drawn from existing theory with potential relevance to Ethiopia. Several alternate explanations can be ruled out based on available evidence, while others, I would suggest, complement but cannot replace the argument presented above.

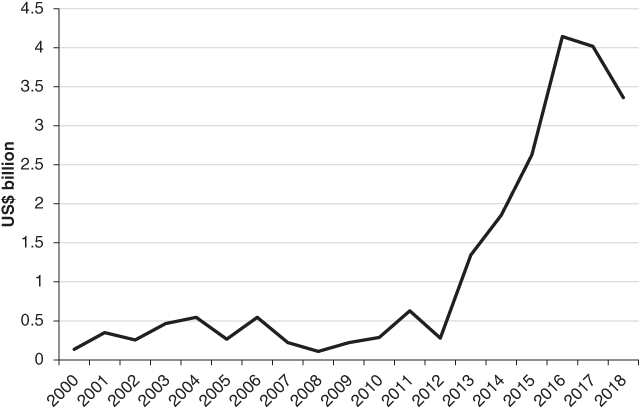

Research on regime transitions in general and Africa in particular highlights that economic crisis is a common cause of regime breakdown (Bratton and van de Walle Reference Bratton and van de Walle1992, Haggard and Kaufman Reference Haggard and Kaufman1997, Geddes Reference Geddes1999, Levitsky and Way Reference Levitsky and Way2010). Economic crisis prevents political elites from buying the support of key intermediaries – whether state bureaucrats, party footsoldiers or security services – resulting in the loss of state coercive powers. This hypothesis is worth considering with respect to Ethiopia given that the ‘developmental state’ model was showing signs of strain by the late 2010s. In particular, the government faced growing concern about its ability to service growing foreign debt due to poor export performance and foreign exchange shortages. Debt ballooned under the Growth and Transformation Plans as the state made vast investments in mega projects seen as essential means of accelerating structural transformation such as hydropower dams, railways, sugar factories and plantations, and industrial parks. The IMF – which had long opposed Ethiopia’s state-led development strategy – raised its assessment of Ethiopia’s debt risk from low to moderate in late 2015 and in October 2016 the Ministry of Finance issued a directive limiting non-concessional borrowing by state enterprises (IMF 2018). The development strategy, which by that time was focused on attracting foreign investment, was further hit by the protests, which from late 2016 targeted agricultural and industrial investment projects. As shown in Figure 10.5, the protests did break the trend of rising foreign investment in 2017 and 2018.

Figure 10.5 Foreign direct investment net inflows

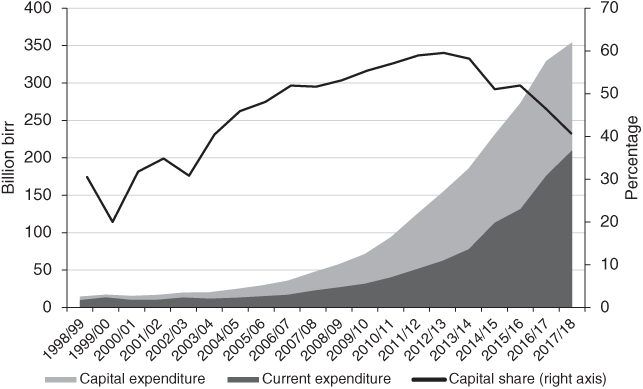

While the debt crisis presented an important and growing challenge to the state-led development model and the protests contributed to the growing economic problems, it would be hard to make the case that either factor was a major cause of the political crisis itself. Available data do not support the hypothesis that economic crisis resulted in an inability to pay lower-level officials. Figure 10.6 shows that government expenditure continued to rise throughout the protests. Indeed, the government ring-fenced pro-poor spending on sectors such as health, education, agriculture, roads and food security – including salaries for state officials – when it sought to limit overall spending after 2016 (Ronnås and Sarkar Reference Ronnås and Sarkar2019, pp. 20–21). Moreover, attempts to placate protestors through measures such as the Youth Revolving Fund led to further spending increases through supplementary budgets (Ronnås and Sarkar Reference Ronnås and Sarkar2019, p. 21). Government spending on capital investments reduced slightly as a proportion of total spending from 2013/14 and then in absolute terms in 2017/18. The result was to slow progress with some major infrastructure projects, though this seems highly unlikely to have contributed to what were by then already widespread protests.

Figure 10.6 Government expenditure

The other major economic factor that might plausibly have contributed to the protests is inflation. Inflation certainly was a major problem, eroding real incomes for public and private sector workers, as well as many smallholder farmers who are net buyers of food. However, as shown in Figure 8.1, the main inflation peaks were in 2008 and 2011. By the outbreak of the protests in 2014–2015, inflation had stabilised at comparatively low levels. While inflation no doubt contributed to a general squeeze on livelihoods for many, on its own it does not provide a strong explanation for the 2014–2018 protests.

Another potentially useful analytical perspective concerns social movements and, in particular, the role of technology in protest organisation. Further research is undoubtedly required to deepen the limited grey literature that has examined the qeerroo and other groups that led the protests (Aga Reference Aga2020, Burayu Reference Burayu2020, Østebø Reference Østebø2020b). The approach taken in this book has focused on intra-elite politics and state strategies for popular incorporation, based on the argument that these factors fundamentally shaped the potential for mass mobilisation and regime breakdown. Broadly speaking, this approach aligns with research on the ‘political opportunity structures’ that shape the potential for social movements (Tarrow Reference Tarrow1998). Nevertheless, a complete understanding of the protests requires more detailed analysis of the organisation of the qeerroo movement itself. The literature on social movements has focused on three main factors (Goodwin Reference Goodwin2001, pp. 55–58). The first is the collective beliefs and identities that are used to inspire mass mobilisation, with movement leaders framing material reality as unjust and alterable, and articulating a set of shared grievances through a particular interpretation of historical events (Sewell Reference Sewell1985, Jasper Reference Jasper1997). Second, is the material resources required to sustain social movements, including money, facilities, communications and transport infrastructure (Tilly Reference Tilly1978, McAdam Reference McAdam1986, Tarrow Reference Tarrow1998). The third factor concerns the key role of social networks in recruiting participants, and sustaining and coordinating collective action (McAdam Reference McAdam1986, Gould Reference Gould1995).

To date, there is insufficient research on the protests to provide a full analysis of the movement in terms of these analytical categories, though a preliminary assessment of key factors can be attempted. Clearly shared beliefs and identities were an important motivation for the protestors in the face of state violence. In the context of federalism, grievances were articulated in ethno-nationalist terms. For the Oromo, this took the form of opposition to TPLF domination, which undermined meaningful ethnic self-determination, and continued more than a century of exploitation by the Ethiopian state. For the Amhara, in contrast, resistance contested the scapegoating of the Amhara for the failings of Ethiopian state-building that had been used to justify the confiscation of territory and political power.

Existing analyses are more divided when it comes to the origins and organisation of the protest movement. The protests have generally been portrayed as a spontaneous uprising, with some local organisation, but very little ‘horizontal’ organisation between protestors in different areas. According to this line of argument, a key role in the coordination was played by the diaspora activist, Jawar Mohammed, who utilised his satellite television station, the Oromia Media Network, and Facebook to communicate with protestors (Østebø Reference Østebø2020b). Ethiopian Satellite Television, associated with diaspora opposition politicians, played a similar role in the Amhara protests. When the government cut internet access, protestors resorted instead to communication through text, phone or word of mouth. A quite different view has recently been put forward by individuals who claim the Qeerroo Bilisummaa Oromoo (Youth for Oromo Freedom) organised the protests. This Qeerroo organisation was apparently established in 2011, inspired by the Arab Spring (Aga Reference Aga2020, Burayu Reference Burayu2020). After several years building organisational networks, the protestors were able to mobilise large numbers of youth, while, they claim, Jawar Mohammed played a modest role. Depending on the assessment of these competing claims, the resources available to the social movement and, in particular, the internet, social media and satellite television, may have played a key role in the protests.

While important questions remain therefore concerning how protestors were able to mobilise and organise so effectively, such an analysis would be supplemental to the core arguments presented above. As leading social movement theorists have long argued, the key factor shaping social movements’ success is the political opportunity structure, which provides signals to emergent movements regarding potential allies among the political elite and shapes the repressive capacity of the state (Tilly Reference Tilly1978, Tarrow Reference Tarrow1998, Goodwin Reference Goodwin2001). A deeper analysis of the organisation of the protests would nuance understanding of the protests, but the key factors leading to the EPRDF’s collapse remain the failings of the EPRDF’s strategy of coercive distribution, the articulation of these distributive failings in terms of ethnic inequality and marginalisation, and elite fragmentation.

Conclusion

The wave of protests that swept across Ethiopia from 2014 and ultimately led to the EPRDF’s collapse were the result of multiple intersecting factors. Foremost amongst these were the mass distributive crisis, primarily affecting young adults, and the fragmentation of the ruling elite, both of which were refracted through the prism of ethnic federalism. On coming to power in 1991, the EPRDF identified its lack of control over the country’s ethnically diverse peasantry and rapid population growth as the main threats to its rule. This threat underpinned elite cohesion in the pursuit of a project of state-led development that promised to provide the distributive resources to secure mass acquiescence. Despite its early identification of these threats to its authority, the EPRDF ultimately proved unable to address them. Population growth outpaced government successes in promoting agricultural productivity growth and industrial employment creation, while the federal system that was intended to contain ethno-nationalism led to the politicisation of popular and elite grievances along ethnic lines. Ultimately, this led to the collapse of the ruling coalition and the end of its project of state-led development.