This chapter examines the process through which charismatic attachments between leaders and followers develop in the first place. The process deserves careful investigation because it influences how charismatic leaders establish a loyal following and consolidate paradigm-shifting political movements. Moreover, it lays the foundation for the trajectories of charismatic movements after the deaths of their founders. As I will demonstrate, the factors involved in the creation of charismatic attachments undermine the mechanisms required for the depersonalization of those bonds while setting up the possibility for their reactivation in personalistic form.

This chapter focuses on analyzing Venezuela due to the relatively recent emergence of Chavismo. Whereas Perón first governed Argentina over sixty years ago, from 1946 until 1955, Chávez ruled Venezuela from 1999 until 2013, just seven years before the time of writing. I leverage the contemporary nature of Chavismo to investigate firsthand the conditions under which charismatic attachments form and to illustrate the mechanisms at work. This analysis provides two key advantages over existing studies, which tend to examine the charismatic bonds in a strictly theoretical or historical context (e.g., Eatwell Reference Eatwell2006; Eisenstadt Reference Eisenstadt and Eisenstadt1968; Jowitt Reference Jowitt1992; Madsen and Snow Reference Madsen and Snow1991; Pappas Reference Pappas2012; Weber Reference Weber, Roth and Wittich1922/1978). First, it reveals fresh insights from a diverse range of voters and elites tied to the regime who remember their personal experiences during the founder’s rule. Second, it provides access to relevant, high-quality public opinion data as well as ample primary sources from the period under examination, which are crucial for discerning between the relative influence of programmatic, organizational, and personalistic influences on citizens’ relationship to the founder and his movement.

The chapter begins with a review of the three characteristics involved in the cultivation of deep, unmediated, and emotional ties between charismatic leaders and their followers. I then illustrate how Chávez took advantage of contextual circumstances and his own alluring traits to fulfill these conditions and establish powerful, resilient bonds with his supporters. Next, I contrast the charismatic mechanism of attachment with programmatic and organizational mechanisms, indicating how the former overpowered the latter two to shape citizens’ attachments to Chavismo. To carry out this analysis, I rely on secondary research as well as information from elite interviews, direct observation, and archival research that I conducted during a total of four months of fieldwork in Caracas, Venezuela, in 2014 and 2015.

I complement this qualitative examination with a quantitative analysis of the competing factors involved in citizens’ attachments to the movement. Using an important survey conducted by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) in 2007, at the height of Chávez’s rule, I demonstrate the overwhelming influence of personalistic rather than programmatic or organizational factors on citizens’ ties to the movement. Building on these findings, Chapter 4 uses evidence from focus groups I conducted with followers to assess how their charismatic attachments develop into a resilient identity rather than transform into routinized political linkages. This analysis sheds light on why many remain loyal to the movement after the death of the founder.

3.1 Establishing Charismatic Attachments

How do leaders foster direct, deeply affective attachments with voters to generate loyalty to their movements? As outlined in the previous chapter, I argue that leaders achieve this by fulfilling three conditions. For each condition, contextual factors interact with subjective leader traits to shape citizens’ attraction to the leader and cultivate fervent ties to his movement. While citizens’ initial attraction to the leader helps form these ties, I argue that it is the latter outcome – the process of bonding with the leader’s movement – that is especially important for shaping the trajectory of the movement and its impact on democratic development.

To begin, I argue that the leader must reach out directly to citizens who feel that mainstream society has forgotten them. Due to feelings of suffering and perceived exclusion, these individuals become convinced that the political establishment has no interest in them. Thus, they look for a distinct and impressive political outsider who recognizes their misfortune and appears willing and able to address their long-neglected needs (Madsen and Snow Reference Madsen and Snow1991, 12–15). A crisis that causes disproportionate misery often accentuates these citizens’ thirst for a savior; a cunning leader, in turn, can take advantage of this opportunity to portray himself as the hero that people crave (Weyland Reference Weyland2003, 843).

Importantly, to cultivate charismatic attachments, the leader does not only recognize and promise to resolve the people’s suffering. Rather, he must fulfill a second condition: He must demonstrate his ability to resolve their misery and defend them against the “evil” forces blamed for their distress. To do so, the leader enacts bold policies that quickly produce tangible, impressive results (Pappas Reference Pappas2012, 4–5; Weber Reference Weber, Roth and Wittich1922/1978, 242). Whereas direct recognition provides marginalized citizens with hope for a more dignified life, the leader’s daring performance convinces them that he is capable of delivering on this promise. Importantly, the perception of the leader’s performance as “miraculous” exceeds the positive outcome that would result from voters’ rational performance evaluations; instead, the leader’s performance produces an emotionally intense and unquestioning devotion in the followers that endures even after the leader’s performance declines.

Finally, the leader cements his charismatic image and consolidates a loyal following by crafting a narrative that reinforces his superhuman power, intrepid quest to vanquish the people’s enemies, and commitment to transforming society. To ensure that the narrative resonates with his followers, the leader ties it to relevant cultural figures and symbols with whom his followers already identify (Willner and Willner Reference Willner and Willner1965, 82). Likewise, the leader associates his opponents with familiar, epic foes. By integrating these commonly understood prototypes of good and evil, his narrative reframes well-known historical events “within a salvation framework” that reinforces the legendary character of his leadership (Smith Reference Smith2000, 103–4). To ensure widespread dissemination of the narrative, the leader infuses public spaces with the movement’s symbols and emphasizes key components of the narrative via frequent, unmediated interactions with his followers (Plotkin Reference Plotkin2002, 24; Zúquete Reference Zúquete2008, 93–103). Together, these actions shape the leader’s capacity to establish direct, profoundly emotional connections with his followers.

3.2 Charismatic Attachments in Chávez’s Venezuela

Hugo Chávez’s meteoric rise to power and his fourteen-year rule over Venezuela clearly illustrate the process through which leaders exert charisma to form steadfast attachments and establish powerful movements. Chávez made his political debut in the early 1990s as a military officer amid the collapse of Venezuela’s Punto Fijo (PF) regime. The regime, which was born out of a 1958 political pact between two major, centrist political parties that sought to secure democratization, achieved uniquely high levels of political stability and economic growth compared to its Latin American neighbors for several decades (Smilde Reference Smilde, Smilde and Hellinger2011, 4; Weyland Reference Weyland2003, 826).Footnote 1 However, when the country faced a protracted economic downturn starting in the 1980s, establishment politicians from the two main parties undermined their own legitimacy in several ways. First, they enacted a series of deeply unpopular and ultimately ineffective economic reforms in an attempt to address the worsening crisis, causing citizens prolonged suffering (Weyland Reference Weyland2003, 826–27). Second, while ideologically distinct in name, the two parties became virtually indistinguishable due to their shared commitment to a neoliberal approach (Morgan Reference Morgan2007, 83–84). Third, as establishment politicians clung to power, massive corruption scandals implicating both parties surfaced, proving to citizens that writ large the system no longer represented their interests (Seawright Reference Seawright2012, 90).

In February 1992, during this party-system breakdown, Chávez led a clandestine group of officers called the Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement-200 (MBR-200) in an attempted coup against President Carlos Andrés Pérez (Smilde Reference Smilde, Smilde and Hellinger2011, 487). Although the coup failed and Chávez served the next two years in prison, his defeat earned him national notoriety as an honorable young man determined to rescue Venezuelans from the grips of the selfish “partyarchy” (Coppedge Reference Coppedge1997). By 1998, another failed round of neoliberal policies enacted by President Rafael Caldera sealed the fate of the PF regime. Out of its ashes, Chávez – who promised a radical departure from the outgoing regime’s corruption and incompetence – took the country by storm, winning the presidential election with 56 percent of the vote (Weyland Reference Weyland2003, 828).

3.2.1 Direct Recognition of Marginalized Citizens

Over the course of his rise and rule, Chávez exerted all three of the above-described components of charisma, resulting in the formation of steadfast bonds with millions of Venezuelans. First, he directly recognized and politically incorporated masses of impoverished citizens who had suffered terribly during the 1980s and 1990s, during which Venezuela experienced a sustained economic decline and the PF regime disintegrated (Lupu Reference Lupu2014; Maingon Reference Maingon2004; Mainwaring Reference Mainwaring, Hicken and Kuhonta2014; Morgan Reference Morgan2011; Seawright Reference Seawright2012; Weyland Reference Weyland2003). Specifically, in the years leading up to his first presidential candidacy in 1998, Chávez recognized that Venezuelans’ widespread feelings of exclusion and suffering presented an important opportunity. Unlike politicians from across the ideological spectrum who came to support the PF regime’s widely unpopular neoliberal policies, Chávez publicly empathized with the people’s intense frustration and misery – as demonstrated through his attempted coup in 1992 (Roberts Reference Roberts2013, 1434–40). As a result, poor citizens came to see Chávez as the only leader capable of understanding and resolving their suffering. A Chavista activist illustrated this sentiment in an interview with the author. Unlike politicians from the PF regime who remained preoccupied with their “elite intellectualism … Chávez made the poor and invisible people visible.”Footnote 2 Similarly, a prominent opposition politician stated that Chávez’s open recognition of people’s feelings of suffering and marginalization resonated deeply with them. The politician said, “Chávez understood the people’s accumulated frustration. The people didn’t feel valued [by other politicians]; Chávez made them feel recognized.”Footnote 3

Throughout his presidency, Chávez publicly acknowledged his followers’ suffering and reinforced his role as their savior. A speech he gave on January 10, 2003, illustrates how he claimed personal responsibility for poor and excluded groups:

Make no mistake about Hugo Chávez … in accordance with the Constitution of the Republic and my powers as Chief of State and my responsibilities as President of the Republic, I cannot permit that people die of hunger; I cannot permit that children die because there isn’t medicine or there isn’t milk; I cannot permit that the people drown of hunger and death. Above all things it is my responsibility in front of God and the flag to defend the Venezuelan people, above all things and as dictated by the Bolivarian Constitution!

By promising to single-handedly protect his people from hunger, disease, and death – maladies they suffered at the hand of his predecessors – Chávez illustrated how he sought to personally acknowledge and incorporate excluded sectors of the population into the center of political life. This recognition proved tremendously successful in laying the foundation for many poor citizens’ devotion to Chávez. Indeed, it consolidated their “powerful belief in the ability of the leader to provide transcendence and moral-political renewal” (Hawkins, Rosas, and Johnson Reference Hawkins, Rosas, Johnson, Smilde and Hellinger2011, 187).

3.2.2 Approbation of Heroic Powers through Bold Reforms

To substantiate his claim to rescue the people from their misery, Chávez implemented a series of daring reforms that promised to sweep away the malevolent “political class” and bring peace and prosperity to the masses. He established what would become the cornerstone for all of these ambitious reforms – a new, hyperpresidential constitution that granted him hegemonic control over politics – immediately after assuming the presidency (Corrales and Penfold Reference Corrales and Penfold2015, 19–20; Ellner Reference Ellner2011, 435; Stoyan Reference Stoyan2020, 99–100). During his 1998 presidential campaign, Chávez vowed to enact this constitution to break away from the corrupt PF regime, personally restore and protect Venezuelans’ socioeconomic rights, and enhance their direct participation in politics. After his victory, in his February 1999 inaugural speech, the new president declared what would become a celebrated refrain among his followers: “I swear before God, before the Country, before my people that over this moribund Constitution, I will enact the democratic transformations necessary for the Republic to have a Magna Carta that fits with the new times. I swear” (Chávez Reference Chávez1999). On December 15, 1999, the referendum on the new constitution passed with 72 percent support.

The swiftness and thoroughness with which Chávez oversaw the construction of a new, far-reaching, and overwhelmingly popular constitution made him appear truly heroic in the eyes of his supporters. Several prior leaders, including Jaime Lusinchi (1984–89) and Rafael Caldera (1994–99), who had promised similar constitutional reforms, had failed to follow through (López Maya and Lander Reference López Maya, Lander, Smilde and Hellinger2011, 58). In contrast, Chávez made good on his vow by installing a new and transformative Magna Carta immediately after assuming office. This act – which, among other things, renamed Venezuela “The Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela” – confirmed Chávez’s position in the eyes of his marginalized followers as their liberator and the symbolic reincarnation of national independence hero Simón Bolívar (López Maya and Lander Reference López Maya and Lander2000, 8–10).

The new constitution outlined a series of ambitious and unprecedented objectives, further demonstrating Chávez’s extraordinary capacities to provide the suffering followers with material prosperity and spiritual transcendence (Hawkins Reference Hawkins2010, 35; Stoyan Reference Stoyan2020, 105). For instance, in addition to representative democratic institutions, it created new participatory institutions, including electoral and civil branches to be overseen by the National Electoral Council and the Defender of the People, respectively. The constitution also moved beyond basic political and civil rights to proclaim economic and social inclusion for all citizens. To achieve this vision of inclusion and equality, Chávez endeavored not only to redistribute wealth, but also to fundamentally transform society – to “reestablish the human condition” (López Maya and Lander Reference López Maya, Lander, Smilde and Hellinger2011, 63). By ratifying his new constitution in the first year of his presidency, Chávez boldly signaled his intention to fundamentally transform Venezuela – a proposition that the poor masses embraced with fervor.

Inspired by the success of his new constitution, Chávez implemented several programs that achieved impressive initial results and thus further demonstrated his extraordinary capacities to his supporters. For example, starting in November 2001, he enacted an unprecedented program of land reform through the Law of Land and Agricultural Development and Decree 1.666. This program established a series of Rural and Urban Land Committees through which poor citizens could “exercise their right of property” and thus achieve socioeconomic inclusion, as envisioned by the new constitution (López Maya and Lander Reference López Maya, Lander, Smilde and Hellinger2011, 65). By 2005, 6,000 Urban Land Committees incorporating nearly one quarter of poor Venezuelans had been established (ibid., 66).

Despite the early success of the new constitution and the policies it inspired, however, several problems emerged that went unaddressed. Consequently, the striking initial impact of these reforms began to deteriorate just a few years after their implementation. For example, the new participatory institutions, purportedly designed to empower ordinary citizens, leaned heavily on Chávez’s personal leadership and thus served to concentrate his executive authority rather than provide the citizens with a direct and independent role in the political process (Ellner Reference Ellner2011, 431–32; López Maya and Lander Reference López Maya, Lander, Smilde and Hellinger2011, 60). Similarly, the land reform policies lacked regulation and enforcement mechanisms, resulting in violent conflict between landowners and peasants after the establishment of Rural Land Committees (ibid., 65–66). Additionally, Urban Land Committees, while initially successful in mobilizing the urban poor, became increasingly dependent on the Chávez regime for resources, resulting in a hierarchical structure that undermined the autonomy of local committee members (ibid., 67). Notably, in spite of these clear shortcomings, followers continued to view Chávez as their savior.

As these examples indicate, though Chávez’s constitution made sweeping promises to promote participatory democracy and social justice, the programs allegedly designed to achieve these objectives fell short and even contradicted values of political participation and social inclusion. Yet, rather than acknowledging these shortcomings, Chávez continually papered over them with new, equally bold and unrealistic measures, which he delivered through spontaneous executive decrees and “organic laws” rushed through the National Assembly (López Maya Reference López Maya2016, 211). The audacity and seemingly direct delivery of these gestures only reinforced Chávez’s valiant image in the eyes of his supporters. As a policy coordinator from the Central Bank of Venezuela described, “Chávez was a magician who created the illusion of progress.”Footnote 4 While unrealistic and irresponsible, the initial, tangible effects of his daring policies – embodied by his ambitious new constitution – “proved” his extraordinariness in the eyes of the followers, thereby making him worthy of their devotion.

3.2.3 Construction of a Symbolic Narrative

To solidify his charismatic bonds with the people and consolidate the transformative power of his movement, Chávez cultivated a vivid narrative with three key characteristics. First, the narrative employed “missionary” rhetoric that glorified his image and tied him to classic heroes embedded in Venezuelan culture, including Simón Bolívar, Venezuela’s nineteenth-century liberator; Ezequiel Zamora, the hero of Venezuela’s Federal War; Guicaipuro, an indigenous Venezuelan chief who fought against the Spanish Conquest; and even Jesus Christ (Martínez Meucci and de Lustgarten Reference Martínez Meucci and de Lustgarten2014, 19–21; Michelutti Reference Michelutti2017, 237–38; Zúquete Reference Zúquete2008, 97). The comparison with familiar, beloved heroes cast a saintly glow on Chávez’s figure and imbued his mission with profound historical importance. In fact, the very labeling of his movement as “Bolivarian” suggested to his followers that Chávez did not merely seek to improve their lives, but that he also sought to “reclaim the dignity of the people, of the country, and of the supposedly better past, the mystical, glorious and heroic path that Venezuela always associated with the figure of Bolívar” (Martínez Meucci and de Lustgarten Reference Martínez Meucci and de Lustgarten2014, 23). By depicting Chávez as the true son of Venezuela’s most celebrated and tragic hero, his narrative tapped into several preexisting identities relevant to his followers, ranging from popular Christianity to mestizaje to Santería, and caused Chávez’s followers to worship him like a deity (Michelutti Reference Michelutti2017, 234–36). As a professor of social and cultural studies at the Bolivarian University of Venezuela passionately proclaimed two years after the leader’s death, “Chávez is on the altar with the saints!”Footnote 5

Second, while cultivating his image as a hero of epic proportions, Chávez’s narrative also demonized his opponents. In contrast with his followers, whom he affectionately called “patriots” and “soldiers,” Chávez referred to his adversaries as “enemies,” “coup plotters,” “imperialists,” and agents of the “extreme right” (Gauna Reference Gauna2018, 47). For example, in 2003 he declared in a speech, “this is not about the pro-Chávez against the anti-Chávez … but … the patriots against the enemies of the homeland” (Zúquete Reference Zúquete2008, 105). Further, when opposition citizens protested, he often framed them as enemies of the true “people” and responded with brutal punishment rather than openness to negotiation, as illustrated by his response to the December 2002 strike by workers from the national oil company, Petróleos de Venezuela (PdVSA) (Corrales and Penfold Reference Corrales and Penfold2015, 24–25).Footnote 6 He also routinely marginalized and persecuted opposition judges, leaders, and parties and expelled advisors from within his own ranks whom he accused of betraying him, periodically humiliating these individuals through surprise attacks broadcasted to the public on his weekly television show (Carroll Reference Carroll2013, 64).

The establishment of an all-out war against a “clear-cut enemy” helped promote cohesion and obedience among Chávez’s followers by convincing them that their beloved leader’s critics posed a grave, even existential, threat (Huddy Reference Huddy2001, 150). As explained by the Bolivarian University professor, “Under threats from the ‘extreme right,’ Chávez would unify the people, so there was not dispersion.” In addition to strengthening cohesion among his followers, this strategy made Chávez appear even more charismatic and provided him with convenient scapegoats to blame for drops in performance. By alienating his movement’s opponents and attacking “traitors” from within it, the narrative also helped solidify a deep-seated and profoundly personalistic cleavage.

Third, Chávez’s symbolic narrative generated a mission that promised not only to vanquish evil opponents but also to emancipate the followers from their suffering by bringing about a holistic transformation of society. In contrast to “small, pragmatic changes to an already existing political system,” the mission envisioned a “rebirth” of Venezuela (Zúquete Reference Zúquete2008, 112). The urgency of this all-encompassing agenda left no time or space for questions from hesitant observers. Rather, Chávez emphasized that successful transformation demanded the absolute faith of his followers; those who failed to demonstrate this commitment would suffer dire consequences. As Zúquete states, “To stress this need for a radical transformation of the country, Chávez’s discourse gain[ed] an apocalyptic dimension in which the survival of the country and even the world seem[ed] to be in question” (ibid.). A Chavista activist and journalist further stressed, “the transformation cannot happen without the followers; we need their faith in Chávez.”Footnote 7

To build his symbolic narrative, Chávez established constant, direct communication with his followers through speeches and other performances that dominated media outlets. As the journalist explained, Chávez was a “communicational genius who started a revolution through the media.” The star of his own weekly television show, “Aló Presidente,” he spoke directly into the camera for hours, giving his followers the impression of having an intimate conversation with their president (Capriles Reference Capriles2012, 60; Carroll Reference Carroll2013, 15–18; Zúquete Reference Zúquete2008, 100). He also frequently interrupted radio and television programs to make “emergency” announcements (cadenas) and reinforce the perception of his omnipresence in Venezuelans’ lives (Carroll Reference Carroll2013, 24). As a palace historian and archivist for Chávez described, the founder also traveled tirelessly around the country to personally connect with his followers, both during and between electoral campaigns.Footnote 8

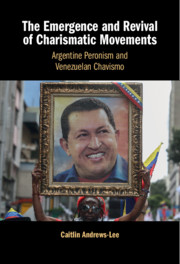

In addition to ensuring frequent and direct communication with his followers, Chávez strengthened his narrative by tightening his control over the media and saturating public spaces with symbols that glorified him and his movement. For example, Chávez’s government purchased or intimidated opposing news outlets by cutting funding, revoking licenses, and constricting the availability of material supplies (Weyland Reference Weyland2013, 19, 23–24). This left the movement with unencumbered space to project the narrative through media platforms ranging from television to radio to print. Chávez also took literal and symbolic ownership of traditional Venezuelan literature, art, and music. His regime sponsored literature, film, art, and music festivals and enjoyed the support of authors, musicians, and artists who fervently dedicated their work to the Comandante. Lastly, the movement filled physical spaces with Bolivarian symbols in the form of posters, murals, statues, buildings, colors, and songs that glorified the founder and his heroic predecessors. For example, Figure 3.1 displays a mural depicting Chávez with Bolívar and Christ (Ramirez Reference Ramirez2014). When combined with his recognition of previously excluded citizens and his implementation of bold reforms, the omnipresence of Chávez’s narrative transformed Chavismo into “a charismatic form of political religion” to which his followers became deeply attached (Zúquete Reference Zúquete2008, 92).

Figure 3.1. Mural of Chávez, Christ, and Bolívar

In sum, Chávez formed steadfast charismatic bonds with his followers by fulfilling three conditions. First, he directly recognized the suffering of marginalized citizens and promised to rescue them from their misery. Second, he proved his ability to follow through on this promise by implementing bold reforms that made an impressive initial impact on followers’ lives, such as a radical new constitution. Third, he established a compelling narrative that tied his heroic leadership to Venezuelan history, underscored the dangerous threat posed by his opponents, and reinforced his mission to provide transcendence by bringing about a profound transformation of society.

3.3 Assessing the Relevance of Alternative Linkage Types

The preceding section outlined the conditions under which charismatic attachments form and demonstrated the role of these ties in Chavismo. Yet, evaluating the impact of charisma on citizens’ attachments and identification with the movement also requires analysis of competing linkage types. This section assesses the extent to which followers developed alternative forms of attachment to Chavismo rooted in programmatic and organizational mechanisms, and it demonstrates how followers’ charismatic bonds overwhelmed these more conventional linkages.

3.3.1 Programmatic Attachments

The programmatic mechanism suggests that citizens’ attachments rest on the substantive coherence of the leader’s policies. Grounded in long-standing studies of issue preferences, retrospective and prospective economic voting, and partisanship, most scholars assume that this mechanism forms the natural and proper core of party and electoral politics (e.g., Achen Reference Achen2002; Downs Reference Downs1957; Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981; Key Reference Key1966; Roberts Reference Roberts2014). To develop programmatic ties, citizens must have well-formed issue preferences that align with the leader’s policies (Key Reference Key1966, 7–8). In addition, the leader must consistently and successfully carry out these policies to earn voters’ approval and establish a clear programmatic trademark that is distinct from that of other parties (Fiorina Reference Fiorina1981, 66). In contrast to bold, shortsighted reforms, whose initially impressive performance casts the individual leader in a heroic light, the programmatic trademark rests on the substantive content and steady functioning of social and economic policies. Citizens “periodically update” their attachment to the movement based on the leader’s adherence to this trademark (Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt2000, 846). If the leader fails to implement distinctive and effective policies that are consistent with this trademark, citizens punish him and reduce their attachment to the movement (Achen Reference Achen2002, 151; Lupu Reference Lupu2013, 52).

Several scholars claim that Chávez developed a programmatic trademark that emphasized state-centered economics and redistributive social programs called missions. To begin, Chávez attempted to increase the state’s role in the economy. For instance, he tightened government control over the state-run oil company, PdVSA, by ratifying the New Organic Hydrocarbon Law in 2001 (Parker Reference Parker2005, 44). Shortly thereafter, he nationalized dozens of non-oil companies and implemented a sweeping Land Reform Law. He also eventually imposed strict currency exchange and price controls to counteract inflation and keep consumer goods affordable (Corrales and Penfold Reference Corrales and Penfold2015, 64).

However, Chávez did not stake out a clear position on economic policy until late 2001, well after he had consolidated widespread popular support. Upon taking office, he confirmed his center-right predecessor’s minister of finance, Maritza Izaguirre, and appeased the International Monetary Fund by cutting the state’s budget by 7 percent and strengthening the Investment Fund for Macroeconomic Stabilization (Corrales and Penfold Reference Corrales and Penfold2015, 48–55). Despite these economically liberal policies, which contrasted sharply with his later turn to “socialism of the 21st century,” Chávez’s movement cultivated impressive popular support: In 1999 and 2000, between 38 and 41 percent of Venezuelans claimed to identify with the movement and 75 to 84 percent approved of Chávez’s performance (Consultores 21 2014).

By late 2001, Chávez began to advertise and implement state-centered policies that were inspired by his new constitution. While many of these programs achieved impressive results at the outset, their performance soon dropped, providing little foundation for sustained programmatic support. For example, though booming oil prices from late 2003 to 2008 facilitated substantial economic growth, Chávez’s protectionist policies failed to stimulate investment and instead invited rampant corruption (Ellner Reference Ellner2010, 88–91; Corrales and Penfold Reference Corrales and Penfold2015, 70). Thus, production in non-oil sectors declined, leading to sharp rises in the number of imported goods; investment in infrastructure lagged, generating electricity and water shortages; and price and exchange controls caused increasing inflation, a rising black market exchange rate, consumer goods shortages, and capital flight. The economy contracted by 3.3 percent of GDP when oil prices fell in 2009, and in 2010, Chávez was forced to sharply devalue the local currency (Corrales and Penfold Reference Corrales and Penfold2015, 63–70). The ultimate failure of these policies and the resulting inflation and shortages disproportionately affected low-income citizens, many of whom were strong supporters of Chavismo.

Nevertheless, the substantial decline in Chávez’s economic performance did not temper his followers’ praise. Instead, his policy failures provided an opportunity for the charismatic leader to strengthen his symbolic narrative by blaming opposition actors whom he labeled as enemies of his revolution, including “imperial powers” like the United States and local agents of the “extreme right” (Zúquete Reference Zúquete2008, 104–7). For instance, as Chávez’s economic performance declined over the course of his rule, his anti-US rhetoric steadily increased – even as the US tempered its critiques of Venezuela (Corrales and Penfold Reference Corrales and Penfold2015, 113). Similarly, on the domestic front, Chávez accused his opponents of plotting “conspiracies against and betrayals of the homeland,” thereby undermining the success of his policies (Gauna Reference Gauna2018, 54–55). The success of this rhetorical strategy demonstrates citizens’ willingness to shield their beloved leader from criticism and suggests that their loyalty to his movement was not rooted in the substantive content and consistent performance of his economic programs.

In addition to state-centered economics, Chávez implemented dozens of redistributive social “missions.” Beginning with their launch in 2003, Chávez poured billions of petro-dollars into these programs in areas ranging from health care to information technology (Maingon Reference Maingon2016, 20). The most prominent missions sought to reduce poverty and inequality through better provision of food, health care, education, and housing. Through these programs, Chávez appeared to prioritize the objectives of equality and social justice showcased in his new constitution.

Yet, like his economic policies, Chávez’s social missions suffered from serious problems. The missions sprang up via presidential decree in a rapid, improvisational, and politicized manner that undercut their sustainability. Consequently, while they improved poor Venezuelans’ quality of life at the outset, the missions failed to perform favorably after their first few years of operation (Corrales and Penfold Reference Corrales and Penfold2015, 61; España Reference España2014). In fact, by 2007, Chávez’s most popular social program – the healthcare mission Barrio Adentro – was considered deeply flawed and largely inoperational (Aponte Reference Aponte2014, 128, 165). While poverty declined from 2003 to 2006, it stagnated from 2007 to 2012 and began to reverse thereafter (Ellner Reference Ellner2011, 433–38; Aponte Reference Aponte2014, 153; Maingon Reference Maingon2016, 119–20). By 2014, poverty had risen to 48.4 percent, surpassing 1998 levels by over 3 percentage points (España Reference España2014, 4). Finally, despite the missions’ rapid initial growth, a 2014 survey indicates that a mere 10 percent of citizens report having benefited from them, suggesting a failure to sustainably reduce poverty and protect Venezuelans’ socioeconomic rights (Aponte Reference Aponte2014, 168; España Reference España2014, 8). Thus, it is more likely that followers’ fervent approval of Chávez’s programs throughout this period arose from “lingering beliefs in [his] charisma” than from the substantive integrity of his policies (Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2011, 29).

In short, the superficial nature and volatile performance of Chávez’s economic and social policies indicates his preference for dramatic reform over programmatic development. Though he promised to establish economic and social inclusion in Venezuela, the delayed implementation of his policies and, ultimately, their negative performance made for a weak programmatic trademark. Most importantly, the bold, hasty application and short-lived success of these policies prioritized the establishment of Chávez’s savior-like image at the expense of medium- and long-term effectiveness. Consequently, while deepening followers’ affective ties to Chávez, these policies held little appeal for programmatically principled voters. Moreover, the delayed application of Chávez’s policies cannot account for the movement’s widespread support during his first three years in office. These factors demonstrate how personalism infused Chávez’s policy agenda and compromised the development of programmatic linkages.

3.3.2 Organizational Attachments

The organizational mechanism suggests that political attachments rest on the ties people cultivate with each other through local involvement in movement-affiliated activities and groups. Through these ties, citizens foster an enduring group identity that is maintained via involvement in the movement’s social clubs, neighborhood associations, and political organizations (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1973; Green, Palmquist, and Schickler Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002). Building this type of bond requires the followers’ widespread and regular participation. The movement’s organizations must also be sustained and strengthened over time and must maintain a “horizontal” rather than hierarchical character to inspire group members’ feelings of efficacy (Ellner Reference Ellner2011, 430–31; Rhodes-Purdy Reference Rhodes-Purdy2015, 423–24). Unlike charismatic attachments, in which followers’ sense of belonging comes directly from the leader, the organizational mechanism suggests that the followers ease their feelings of exclusion in a bottom-up fashion by interacting with each other.

Chávez promoted the organizational dynamic of his movement and even enshrined citizen participation in the 1999 constitution as a necessary condition for democracy (García-Guadilla Reference García-Guadilla and Villasante2012, 220). Early in his presidency, he launched several community-based organizations aimed at placing governance into the hands of the people, including Urban Land Committees, Health Committees, Technical Roundtables for Water, and Bolivarian Circles (Aponte Reference Aponte2014; López Maya and Lander Reference López Maya, Lander, Smilde and Hellinger2011). In 2006, he appeared to strengthen this initiative by establishing the Communal Councils (CCs). Officially registered, neighborhood-level groups consisting of 200 to 400 families, the CCs were intended to be self-governing: They would elect representatives, run their own meetings, and solicit funds directly from the government to resolve problems (Aponte Reference Aponte2014, 264).

In practice, however, this network failed to cultivate genuine organizational ties to the movement. First, citizen participation in the CCs was neither widespread nor regular. A 2005–2007 survey of poor Venezuelans by Universidad Católica Andrés Bello (UCAB) suggests that only 29 percent had ever participated in a community event, while only 7 percent had participated in a CC (Aponte Reference Aponte2014, 260). Among the few citizens who participated in CCs, a 2008 survey by Centro Gumilla indicates that less than 50 percent regularly attended meetings (Machado Reference Machado2009, 48–49). Second, the poor infrastructure of these groups compromised followers’ ability to develop a strong grassroots network. Chávez’s sluggish and haphazard institutionalization of the CCs reflects this weakness: He did not legally recognize them through the Law of Communal Councils until 2006, and he neglected to establish a government ministry to oversee them until 2010 (Aponte Reference Aponte2014, 264). By 2012, in a famous speech titled “Changing Course” (Golpe de Timón), Chávez angrily acknowledged the weakness of his movement’s grassroots spirit (Chávez Reference Chávez, Bonnefoy and Avila2012). Third, much evidence indicates that the CCs functioned in a hierarchical fashion. In many CCs, a mere handful of members remained active, and leaders often served as party bosses rather than local representatives, usurping control over projects and funds at the expense of other residents (García-Guadilla Reference García-Guadilla and Villasante2012, 227–35). Perhaps as a result, a 2009 survey by Centro Gumilla suggests 76 percent of Venezuelans perceived CCs as corrupt, while 77 percent agreed that CCs did not involve most members of their community (Machado Reference Machado2009, 37; Aponte Reference Aponte2014, 271).

Ultimately, the evidence suggests that the CCs did not foster genuine grassroots empowerment. While Chávez extolled the virtues of participatory democracy and made dramatic (if irregular) efforts to establish community organizations, these groups suffered from low participation rates and severe institutional weaknesses. Outspoken leaders dominated many CCs and bred distrust rather than a genuine participatory spirit. Moreover, citizens’ feelings of recognition and inclusion depended more on their devotion to Chávez than their involvement in community affairs. Indeed, while followers praised Chávez for giving them a voice in politics, they did not exercise that voice in practice through involvement in the movement’s participatory organizations. Instead, Chávez imposed cohesion over his movement in a top-down fashion, preventing “formal collective decision-making” and suppressing “the emergence of a second-in-command” (Ellner Reference Ellner2011, 434). Therefore, it is unlikely that swaths of followers developed strong attachments to Chavismo based on an organizational mechanism.

3.4 A Quantitative Analysis of Competing Attachment Mechanisms

I draw from a nationally representative 2007 survey by LAPOP to quantitatively investigate the impact of charisma on citizens’ attachments to Chavismo relative to programmatic and organizational factors. The survey contains relevant questions for all aspects of my analysis, including attachment to the movement (dependent variable); evaluation of economic and social policies (programmatic independent variables); participation in the CCs (organizational independent variable); and perceptions of Chávez’s charisma (personalistic independent variable). In addition, the survey was fielded in August and September of 2007, shortly after Chávez’s second reelection. By that time, voters had several years to experience and evaluate both programmatic and grassroots components of Chávez’s movement, including the social missions and CCs. Thus, the survey allows for an important analysis of the personalistic mechanism’s relative strength at a crucial point during Chávez’s rule.

3.4.1 The Dependent Variable

I construct the dependent variable – attachment to Chavismo – using a question on respondents’ party identification. Political scientists have long understood party identification as a genuine expression of membership in or attachment to a political group (Campbell et al. Reference Campbell, Converse, Miller and Stokes1960; Green et al. Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2002; Lupu Reference Lupu2013). Venezuelans’ identification with Chavista-affiliated parties, therefore, captures their self-perceived political ties more adequately than vote choice, which can result from a range of factors extending beyond attachment to the movement. I create a dichotomous measure of attachment where citizens who identify with one of three party labels connected to Chávez’s movement – Movement of the Fifth Republic (MVR), Fatherland for All (PPT), or the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) – are considered “attached” while citizens who do not are considered “not attached.”Footnote 9 Twenty-three percent of all respondents express attachment to these parties, while just fewer than 9 percent identify with non-Chavista parties. Due to the weakly institutionalized nature of Chavismo, measuring identification with associated parties likely underestimates the number of Venezuelans attached to the broader movement. Nevertheless, I use this measure because the survey does not ask about attachment to the movement per se – and I assume that citizens who identify with affiliated parties also have genuine attachments to the movement.Footnote 10

3.4.2 The Independent Variables

I select several survey items as independent variables to represent the three attachment mechanisms. For the charismatic mechanism, I incorporate a five-question battery on perceptions of Chávez’s charisma developed by Merolla and Zechmeister (Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2011).Footnote 11 This focus on citizens’ perceptions of the leader, rather than “objective” personality traits, captures the subjective dynamic of charismatic authority (Weber Reference Weber, Roth and Wittich1922/1978, 242). As shown previously in this chapter, the factors underlying the charismatic mechanism – direct recognition, bold reforms, and the symbolic narrative – also serve to increase perceptions of the leader’s charisma, suggesting the validity of the measure. Though many successful leaders are perceived as charismatic, scholars have stressed that, relative to other Latin American presidents, perceptions of Chávez’s charisma were uniquely high throughout his tenure (Weyland Reference Weyland2003, 822; Zúquete Reference Zúquete2008, 91; Hawkins Reference Hawkins2010, 37–38; Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2011, 37–38). Furthermore, while related to party attachment, leader approval, and vote choice, charismatic perceptions remain a theoretically and empirically distinct concept.Footnote 12

The questions in the LAPOP charisma battery ask respondents to report on a four-point scale the extent to which they agree about five statements: (1) Chávez articulates a compelling vision of the future, (2) Chávez instills pride in being associated with him, (3) Chávez’s actions build my respect for him, (4) Chávez considers the moral and ethical consequences of his decisions, and (5) Chávez goes beyond his own self-interest for the good of the group (Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2011, 37). I add and rescale these items to create a continuous score of Chávez’s charisma ranging from zero (not at all charismatic) to one (very charismatic).Footnote 13

For the programmatic mechanism, I first include survey items that gauge respondents’ perceptions of Chávez’s economic performance. Following Merolla and Zechmeister (Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2011), I combine four questions – on current and retrospective evaluations of the economy at the national and personal levels – into a single variable using factor analysis, then rescale the variable to range from zero (bad) to one (good). It is important to note that this indicator does not exclusively reflect the programmatic mechanism. Indeed, citizens could give positive evaluations because they approve of the regime’s economic programs or because they perceive Chávez as a savior who makes good on his promise to rescue the people. As Merolla and Zechmeister suggest, “individuals who perceive Chávez as highly charismatic see Venezuela’s economy … through rose-colored glasses” (Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2011, 31). In other words, charismatic perceptions of Chávez may cause respondents to evaluate the economy more favorably. To examine this possibility, I run one set of models in which economic evaluations and charismatic perceptions are independent and a second set of models in which they are interacted. The interaction term will shed light on whether and how charismatic perceptions impact the effect of economic evaluations on citizens’ attachments to Chavismo.

In addition to economic performance, I incorporate two questions on respondents’ assessments of Chávez’s two largest social missions to measure the strength of the programmatic mechanism – the health mission (Barrio Adentro) and the food mission (Mercal). I add these evaluations and rescale the sum to range from zero (bad) to one (good). Incorporating these variables cuts the sample size by over half (N = 641) because only about 50 and 70 percent of respondents report having used the health and food missions, respectively. To address this issue, one set of models examines whether respondents accessed these missions in the first place, while a second set explores the subsample of respondents who report having used both missions. Whereas the former variable measures access to the missions, which tends to be restricted based on partisanship (Hawkins et al. Reference Hawkins, Rosas, Johnson, Smilde and Hellinger2011), the latter more closely reflects citizens’ substantive evaluation of those programs.

To measure the influence of participation in movement-affiliated organizations on attachment to Chavismo, I incorporate a question about respondents’ involvement in the CCs. Because the CCs represent the movement’s central network of participatory organizations, respondents with organizational ties should report extensive involvement in these groups. I rescale a four-point scale in which one is “never” and four is “every week” to range from zero (low) to one (high).

Finally, I incorporate four control variables thought to influence citizens’ identification with Chavismo: socioeconomic status, education, age, and gender.Footnote 14 Table 3.1 displays descriptive statistics for the key dependent and independent variables for both surveys. Additional information on the survey can be found in the online Appendix A.

Table 3.1. Descriptive statistics for dependent and independent variables

| Variable | Scale | N | Mean | Std. Dev. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment to Chavismo* | 0–1 | 1510 | 0.23 | 0.42 |

| Charismatic perceptions | 0–1 | 1438 | 0.55 | 0.36 |

| Economic evaluations | 0–1 | 1474 | 0.50 | 0.22 |

| Mission recipient | 0–1 | 1510 | 0.60 | 0.39 |

| Evaluation of missions | 0–1 | 641 | 0.84 | 0.21 |

| Communal Council participation | 0–1 | 1495 | 0.25 | 0.36 |

| Socioeconomic status | 0–1 | 1510 | 0.58 | 0.24 |

| Education (years) | 0–20 | 1509 | 10.50 | 4.45 |

| Age | 18–89 | 1510 | 36.27 | 14.06 |

| Female* | 0–1 | 1510 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Urban* | 0–1 | 1510 | 0.95 | 0.21 |

* The proportion rather than the mean is given for dichotomous variables.

In total, I analyze four binary logistic regression models. Models A and C include the variable on access to the missions and thus include most respondents (N = 1326). Models B and D replace this variable with one on substantive evaluation of the missions among those who accessed them (N = 579). Finally, Models A and B treat charismatic perceptions and economic evaluations independently, whereas Models C and D interact with the two variables. The next section discusses the results based on these four models.

3.4.3 Results

The results (Table 3.2) suggest the uniquely strong influence of charisma on citizens’ attachments to Chavismo. Models A and B indicate that charismatic perceptions have a statistically significant and substantively large impact on citizens’ ties to the movement. In the unrestricted sample (Model A), respondents who perceive Chávez as extremely charismatic (score of one) are 47 percentage points more likely to express attachment than those who find Chávez extremely uncharismatic (score of zero), holding the remaining independent variables constant at their means. Among mission users (Model B), this figure rises to 58 percentage points (Figure 3.2).

Table 3.2. Binary logistic regression results

| Model A | Model B | Model C | Model D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Charismatic perceptions | 4.06*** (0.36) | 3.74*** (0.49) | 6.32*** (1.04) | 6.65*** (1.51) |

| Economic evaluations | 0.79 (0.41) | 0.52 (0.52) | 4.26** (1.50) | 4.85* (2.11) |

| Charismatic perceptions * Econ. evaluations | – | – | –4.32* (1.77) | –5.30* (2.49) |

| Mission recipient | 1.26*** (0.23) | – | 1.25*** (0.23) | – |

| Evaluation of missions | – | 0.48 (0.53) | – | 0.42 (0.53) |

| CC participation | 0.17 (0.20) | 0.29 (0.25) | 0.20 (0.20) | 0.32 (0.25) |

| Socioeconomic status | 0.18 (0.33) | 0.02 (0.43) | 0.20 (0.33) | 0.04 (0.43) |

| Education | 0.05** (0.02) | 0.07** (0.03) | 0.05** (0.02) | 0.07** (0.03) |

| Age | 0.02** (0.01) | 0.02** (0.01) | 0.02** (0.01) | 0.02** (0.01) |

| Female | –0.19 (0.15) | –0.20 (0.19) | –0.19 (0.15) | –0.20 (0.19) |

| Urban | 0.22 (0.35) | 0.59 (0.47) | 0.24 (0.35) | 0.63 (0.47) |

| Intercept | –6.65*** (0.55) | –6.11*** (0.84) | –8.52*** (0.99) | –7.92*** (1.38) |

| N | 1390 | 607 | 1390 | 607 |

| Pseudo-r2 | 0.29 | 0.20 | 0.29 | 0.20 |

Standard errors shown in parentheses.

*p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

Figure 3.2. Predicted probability of attachment at different levels of charismatic perceptions

In contrast, the programmatic and organizational variables are only weakly associated with attachments to the movement. Models A and B suggest that economic performance does not have a significant, independent impact on Bolivarian attachment. Models C and D examine the potential interactive effect of charismatic perceptions and economic evaluations on attachment. Interpreting this effect requires visual examination of predicted probabilities (Figure 3.3), as the statistical significance of interactions in nonlinear regression does not necessarily indicate a substantively meaningful effect (Brambor, Clark, and Golder Reference Brambor, Clark and Golder2006, 73–74). Model C suggests that there is no meaningful interactive effect: At different levels of charismatic perceptions, the influence of economic performance evaluations on attachment does not change significantly. However, Model D suggests that the interactive effect may have a small, negative effect among mission users: As charismatic perceptions of Chávez increase, the effect of performance evaluations on Bolivarian attachment decreases slightly. While this interaction appears significant, its negative sign suggests that higher charismatic perceptions dampen the influence of performance evaluations. The evidence therefore underscores the “Teflon” effect of Chávez’s charisma (Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2011, 30), which protects him from the negative consequences of poor performance.

Figure 3.3. Effect of economic evaluations on probability of attachment at different levels of charismatic perceptions: Interactive models

In terms of social programs, accessing benefits from one or both missions significantly increases the probability of expressing attachment to the movement. However, as discussed earlier, this does not necessarily suggest that the programmatic mechanism is at work. In fact, among mission users (Model B), substantive assessments of the missions have no significant effect, suggesting that the quality of these programs does not influence respondents’ attachments. Finally, across all four models, participation in the CCs has no significant association with attachment. These data indicate the relative weakness of the programmatic and grassroots mechanisms while further highlighting the strong effects of personalism on loyalty to the movement. Taken together, the four models suggest the relative insignificance of programmatic and organizational factors on Bolivarian attachments while highlighting the disproportionate influence of charismatic perceptions of Chávez.

To ensure the validity of the results, I explore two alternative explanations for the underwhelming effects of programmatic and organizational factors. First, in the additive models (A and B), multicollinearity between charismatic perceptions and the other independent variables could artificially inflate the significance of the former and depress that of the latter. However, the variance inflation factor (VIF) for charisma for both models is low (1.66 and 1.48, respectively), suggesting that multicollinearity does not account for the results.Footnote 15 Second, preference falsification may explain the insignificance of these variables. Specifically, respondents could feel pressured to evaluate Chávez’s charisma more highly than they otherwise might. Yet, citizens generally do not hesitate to express dissatisfaction with Chávez’s regime. In fact, 17 percent of respondents perceive Chávez as completely uncharismatic and 56 percent rate his performance as mediocre, poor, or very poor. One would expect substantially higher approval ratings if preference falsification were at play. The remaining explanation suggests that citizens’ intense perceptions of Chávez’s charisma are intimately linked with their attachment to his movement, while programmatic and organizational factors have notably weaker effects.

3.5 Conclusion

This chapter has investigated the mechanisms through which charismatic attachments form and overpower alternative forms of citizen–politician linkages. Recognition of historically marginalized citizens, daring yet short-lived policies, and a captivating symbolic narrative of redemption cause citizens to perceive the leader as intensely charismatic and solidify their deep, emotional attachments to the leader’s movement. Moreover, the formation of such quasi-religious attachments undermines the development of programmatic and grassroots linkages. Charismatic leaders’ need to demonstrate impressive performance compromises the effectiveness and sustainability of their policies, which weakens the programmatic mechanism of attachment. Additionally, the leaders’ unmediated, top-down recognition of excluded sectors concentrates their personalistic authority and therefore undermines genuine grassroots participation.

I illustrate this argument focusing on the formation of citizens’ attachments to Chavismo in Venezuela. Drawing on qualitative insights from secondary research and three months of fieldwork that I conducted in 2015, I demonstrate that Chávez expertly fulfilled the three conditions necessary for cultivating strong, charismatic attachments with his followers. Subsequently, using data from the 2007 LAPOP survey, I show that voters’ perceptions of Chávez’s charisma provided a stronger, more consistent foundation for their attachment to his movement than factors based on programmatic evaluation and participation in Chavista organizations. Though Chávez proclaimed state-centered economics, redistributive social programs, and grassroots organizations as central to his movement, the results suggest his personal appeal eclipsed these factors. Indeed, most programmatic and organizational elements of Chavismo had no significant relationship with attachment to the movement; in contrast, citizens’ perceptions of Chávez’s charisma were strongly associated with their loyalty to the movement.

I contend that the process through which citizens’ charismatic attachments form is crucial for understanding the resilience of those ties. The three conditions that help form those attachments do not only serve to establish the leader’s initial popularity, but they also make it difficult for subsequent politicians to depersonalize those attachments when the founder disappears. The subsequent chapter draws on focus groups conducted with followers of Peronism and Chavismo to investigate how charismatic attachments, once formed, can develop into a resilient political identity that undermines efforts at routinization while setting the stage for the revival of the movement in personalistic form.