The IMF has not traditionally paid much attention to climate finance or to climate change in general but started publishing reports on climate finance from 2010. More recently, the Fund has paid more attention to climate change in general (IMF, 2019c, 2019e, 2019g; Reference Lagarde and GasparLagarde and Gaspar, 2019). Thus, the IMF has not dedicated as much attention to climate finance as to fossil fuel subsidy reform and has also dedicated less attention to the subject than the G20 and especially the OECD. Nonetheless, the IMF output on climate finance provides an important insight into a case of economisation. The chapter starts with an outline of the IMF’s relatively limited output on climate finance, which initially focused on the mobilisation of climate finance and later more broadly on fiscal policies. The way in which the IMF linked climate finance to fossil fuel subsidies and carbon pricing is indicative of its view that climate change is best addressed by pricing emissions. As I explain in the subsequent section, this approach is shaped by the Fund’s worldview and its focus on fiscal policy, and its initial impetus to address climate finance has come from institutional interaction and policy entrepreneurs within the bureaucracy. Finally, the limited consequences of the IMF output at the international and domestic levels are discussed.

12.1 Output: Linking Carbon Pricing and Climate Finance

The IMF output on climate finance consists mainly of knowledge output in the shape of publications analysing climate finance and providing policy recommendations. Importantly, the IMF has not used its considerable arsenal of incentive-based instruments in the context of climate finance the way it has done with fossil fuel subsidies. The first publication was a staff position note published in 2010 advocating the establishment of a Green Fund (different from the Green Climate Fund established in 2010) which would use some of the Special Drawing RightsFootnote 1 (SDRs) of IMF member states as capital on its balance sheet, thus allowing the Green Fund to issue green bonds with SDRs as security (Reference Bredenkamp and PattilloBredenkamp and Pattillo, 2010). An IMF staff position note is an example of a working paper that has not been through the internal IMF approval procedure and thus does not constitute the official IMF position, but which nevertheless is often indicative of the perspective of IMF staff in general. A position note advocating a position conflicting with the official IMF line would not be published by the IMF. Had the IMF adopted the proposal, it would have constituted a radical break with the previous use of SDRs but also meant that the IMF would have had a very significant incentive-based instrument in its hands.

In June 2011, the Fund was one of the international institutions requested by the G20 to provide an analysis of climate finance. The request resulted in the IMF publishing two background papers on domestic sources of climate finance and international aviation and shipping as sources of climate finance (IMF, 2011a, 2011b) and a chapter in the report requested by the G20 (World Bank Group et al., 2011). The domestic sources included carbon taxes, emissions trading systems with auctioning, levies on electricity or petrol, as well as taxes on income, property, consumption or financial transactions (IMF, 2011b). Climate finance from these sources would be clearly distinct from development aid. The IMF argued in favour of carbon taxes as they, unlike non-carbon sources, would mitigate climate change besides providing revenue. The report on pricing emissions from shipping and aviation also highlighted the mitigation benefits of such pricing, especially as the emissions from international aviation and shipping were not subject to any regulation in 2011. The joint report to the G20 was drafted by the World Bank, the IMF, the OECD and a group of multilateral development banks (MDBs), with the IMF leading the drafting of the chapter on sources of public finance on the basis of its two background papers. In 2012, IMF staff wrote a chapter on how to best use using fiscal instruments to generate climate finance counting towards the USD 100 billion target climate finance (Reference Mooij, Keen, Mooij and KeenMooij and Keen, 2012), published in an IMF report on the fiscal responses to climate change (Reference Mooij, Keen and ParryMooij et al., 2012).

Following a brief hiatus, the Fund again started paying attention to climate change beyond fossil fuel subsidies in 2015, mainly through knowledge but also declaratory output. Regarding the latter, Managing Director Christine Lagarde published a statement on the Fund’s role in addressing climate change that repeated the earlier message that carbon pricing could generate climate finance (Reference LagardeLagarde, 2015). Furthermore, a report on policies supporting the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) highlighted the importance of financial instruments in shifting investment from ‘brown’ to ‘green’ sectors and in improving macroeconomic resilience to natural disasters – including climate related ones (IMF, 2019h). The latter topic was again addressed in 2016 in a report on how the IMF could enhance the resilience of small developing states and a chapter in the IMF’s flagship publication, the World Economic Outlook, on how resilience could be improved in sub-Saharan Africa (IMF, 2016a, 2016b). The focus on shifting investment and improving resilience reflects a wider trend also evident in the G20, the OECD and UN institutions such as UNEP (see Chapters 11 and 12). None of these publications focused specifically on climate change but dedicated considerable space to climate change as a factor exacerbating natural disasters. The IMF’s role regarding such countries is particularly relevant as many of these countries are already heavily indebted (often to the IMF) and may need major financial support if natural disasters destroy large parts of society and the economy. Many of these tenets were repeated in the 2019 report on fiscal policies for meeting the objectives of the Paris Agreement (IMF, 2019c). While mainly focused on carbon pricing, this report stressed the importance of the USD 100 billion target, the importance of financial instruments and private finance for improving resilience, and the possibility of using the pricing of shipping and aviation emissions as a source of climate finance (se also Reference Parry, Heine, Kizzier and SmithParry et al., 2018).

Since 2017, the IMF has published so-called Climate Change Policy Assessments of individual countries, and at the time of writing, Belize, Grenada and Saint Lucia have been the subject of such assessments (IMF, 2017a, 2017c, 2018b, 2019b, IMF, 2019d). One objective of these Policy Assessments is to enhance the countries’ chances of attracting finance (IMF, 2019c). All five are countries vulnerable to climate change, and the Fund recommended mitigation policies – including carbon pricing – and adaptation policies – including risk management. Furthermore, the IMF stressed the importance of receiving external climate finance from private and public sources. Interestingly, most of the IMF publications issued on climate change in 2019, including opinion pieces by Managing Directors Lagarde and GeorgievaFootnote 2 and a special issue of the IMF journal Finance and Development paid only limited attention to climate finance. Instead they focused on carbon pricing, financial markets and the risks associated with climate change (Reference GeorgievaGeorgieva, 2019; IMF, 2019a; Reference Lagarde and GasparLagarde and Gaspar, 2019).

Fundamental to the IMF’s approach has been the notion of pricing emissions, making it an ideal-typical example of economisation. Climate change has been defined as an externality which is best corrected through pricing either through carbon taxes or emissions trading systems chapter (World Bank Group et al., 2011). The primary objective of carbon pricing is, according to the IMF, not to raise revenue but to mitigate climate change. This framing of climate change is also evident in its output on fossil fuel subsidies (Reference Coady, Parry, Sears and ShangCoady et al., 2015, Reference Coady, Parry, Le and Shang2019; IMF, 2011b; World Bank Group et al., 2011, Chapter 2; see also Chapter 7 of this book). Defining climate change as an externality to be corrected by pricing the externality is a core tenet of neoclassical environmental economics, which defines environmental problems as economic problems – typically externalities – and pricing as the solution to such problems (Reference Clements, Coady, Fabrizio, Gupta, Alleyne and SdralevichClements et al., 2013; Reference Coady, Parry, Sears and ShangCoady et al., 2015; see also Chapter 1 and 7). Fiscal policies rather than regulatory or industrial policies are defined as the instrument needed to mitigate climate change.

More recently, the Fund has also attended to adaptation, and argued in favour of addressing climate change impact through financial instruments such as disaster insurance (IMF, 2016a, 2016b). The inclusion of adaptation and the risks associated with climate change constitutes a widening of the economisation of climate change beyond ‘just’ correcting the externality. A similar development can be witnessed in the output of the G20 and the OECD (see Chapters 9 and 10), and reflects a wider development towards a focus on the risk associated with climate change in the literature on the economic dimensions of climate change (for an overview, see Reference Krogstrup and OmanKrogstrup and Oman, 2019). Altogether, climate finance has been defined in a broad sense as encompassing private finance as well as public.

Regarding the issue of generating resources, at the beginning of the period studied, the IMF provided suggestions of how different sources – particularly carbon pricing – could be used to reach the USD 100 billion target (Reference Mooij, Keen, Mooij and KeenMooij and Keen, 2012). The IMF operated with an estimate that if 10 per cent of the revenue from a USD 25 per ton carbon price (compared to the carbon prices of USD 35, 40 or 75 that the IMF would later use in its analyses; see Chapter 7) in developed countries was used for international climate finance, it would generate USD 25 billion towards the USD 100 billion target chapter (World Bank Group et al., 2011).

The estimate stemmed from the 2010 Report from the UN Secretary General’s High-level Advisory Group on Climate Change Financing. The amount of USD 25 billion would constitute public finance provided according to an emissions-based burden-sharing key by developed countries. On a similar note, the IMF also proposed placing a price of USD 25 per ton on the emissions from international aviation and shipping, two sectors hitherto exempted from public regulation (and pricing) of their emissions (IMF, 2011b). If developing countries were compensated for the burden that would fall on themFootnote 3, such a price would generate an estimated USD 22 billion from developed countries towards the target. Finally, the IMF also specified the fiscal savings from phasing out fossil fuel subsidies (using the OECD data and thus not including externalities in the definition of fossil fuel subsidies) as a source of climate finance and estimated on the basis of OECD figures that if 10–20 per cent of the expenditure saved was designated as climate finance, it would could yield USD 4–12 billion dollars annually (IMF, 2011a). Altogether these estimates would add a little more than USD 50 billion, leaving the rest of the USD 100 billion to be covered by voluntary contributions from developed countries and private finance.

Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR) has been explicitly stressed when it comes to the importance of the incidence of global pricing of aviation and shipping emissions and to the earmarking of revenue from domestic carbon pricing (IMF, 2011b). Regarding emissions from shipping and aviation, CBDR has been a key issue in the global discussions of reducing these emissions. Such emissions cannot be allocated clearly between Annex II and non-Annex II countries, and consequently the non-Annex II countries objected to the regulation of these emissions that would subject them to the same rules as Annex II countries, hence contravening CBDR (Reference Bows-LarkinBows-Larkin, 2015; Reference Romera and van AsseltRomera and van Asselt, 2015). Given this context, not mentioning CBDR would have been controversial, and the IMF’s solution was to stress that developing countries, particularly those with low incomes and high levels of vulnerability, should not take on a share of the burden of providing climate finance. In this way, the Fund addressed CBDR by calibrating the economic instrument of carbon pricing to avoid the burden falling on the poorest and most vulnerable, rather than saying that only developed countries should be subject to the regulation of aviation and shipping emissions.

Concerning allocations, the IMF has not focused as much on how climate finance should be allocated as on how it should be mobilised. The Fund’s key objective has been to mitigate climate change while keeping costs low, and hence carbon pricing has been advocated with reference to its efficiency (IMF, 2011b; World Bank Group et al., 2011) . While efficiency has been the main priority, as mentioned earlier, the equity principle of CBDR has also been stressed (IMF, 2011a; Reference LagardeLagarde, 2015). The key priority regarding the use of climate finance has been mitigation, although recent publications have addressed adaptation (IMF, 2016a, 2016b, 2017a, 2017c, 2018b, 2019b, 2019d), and the staff position note proposing a Green Fund has operated with the notion of an even split between mitigation and adaptation finance (Reference Bredenkamp and PattilloBredenkamp and Pattillo, 2010). The IMF has not directly addressed the allocation between states, but has dedicated considerable attention to vulnerable states, both in its publications on improving resilience among small developing and states in sub-Saharan Africa (IMF, 2016a, 2016b), and its Climate Change Policy Assessments, which have only focused on highly vulnerable countries, particularly small island developing states (IMF, 2017a, 2017c, 2018b, 2019b, 2019d). On a couple of occasions, IMF staff have proposed channelling revenue from the issuing of SDR-backed green bonds or from the pricing of maritime emissions to the Green Climate Fund or a proposed Green Fund (Reference Bredenkamp and PattilloBredenkamp and Pattillo, 2010; Reference Parry, Heine, Kizzier and SmithParry et al., 2018). These proposals have not been adopted but would have granted developing countries considerable influence over the allocation of climate finance compared to the current system.

12.2 Causes

The initial cause of the IMF addressing climate finance (the first aspect of economisation) have mainly stemmed from institutional interaction, specifically the G20 requesting that the IMF and other International Organisations provide such analysis. It was in this context that the IMF produced most of its official publications (on domestic sources of climate finance, international aviation and shipping and public finance) focusing solely on climate finance. Once the task was completed, the IMF output on climate finance decreased in volume. Output from before and after 2011 was instead drawn up on the initiative of IMF officials acting as policy entrepreneurs (interview with senior IMF official, 25 March 2015). When IMF management, in the context of COP21 in Paris and the Paris Agreement, increased their attention to climate change beyond fossil fuel subsidies, the Fund’s attention to climate finance also increased, constituting a less direct case of institutional interaction, this time from the UNFCCC (IMF, 2019c, 2019h). The UNFCCC also mattered indirectly in terms of setting the USD 100 billion target, thus providing the G20 with the impetus to task IMF and other institutions with analysing sources that could count towards this target. Furthermore, the climate finance chapter in the fiscal responses to climate change book (Reference Mooij, Keen, Mooij and KeenMooij and Keen, 2012) were also explicitly written to address the USD 100 billion target.

Importantly, the member states of the IMF have not played an important role in getting the IMF to address climate finance, except for the fact that the G20 member states that requested the IMF to address the issue were also key IMF member states. Thus, they would know that the IMF would not turn down the G20 request, since the G20 members had a majority of the votes and 16 out of 24 Executive Directors. The level of IMF involvement has been circumscribed by the IMF’s mandate, which does not include development finance the way, for example, the World Bank’s does (interview with senior IMF official, 25 March 2015). In 2019, the IMF Executive Directors (representing the member states) agreed to increase IMF activities supporting countries’ fiscal policies for mitigation and adaptation, yet with a number of Directors cautioning against moving beyond the Fund’s mandate (IMF, 2019c). Rather, the IMF has been involved in aspects of climate finance that have touched upon its core area of fiscal policy, especially fossil fuel subsidy reform and taxation (domestic or on international shipping and aviation). In this way, relations with member states have been important in delineating IMF involvement in climate finance, since they have interpreted to which extent climate finance falls within the mandate of the IMF. Although the IMF bureaucracy has often pushed the limits of its mandate, it has not attempted to do so in the case of climate finance, reflecting the belief among the Management that other institutions, especially the World Bank, are better suited to address the issue (interview with senior IMF official, 25 March 2015).

As regards the second aspect of economisation, how the Fund has addressed climate finance, the IMF worldview has been the most important factor. Not only has climate finance been framed in economic terms, rather than environmental or equity terms, it has also consistently been linked to IMF core tenets such as the need for carbon pricing and fossil fuel subsidy reform (two sides of the same coin to the IMF, as discussed in Chapter 7). Importantly, in its reports to the G20, the IMF recommendations were based on the notions that all public funds would stem from developed countries, and the revenue from carbon pricing would de facto be provided according to an emissions-based burden-sharing key. Both notions, especially the emissions-based burden-sharing have been highly unpopular with the IMF’s most powerful member state, the United States. Other influential member states are also sceptical of solely placing the burden on developed countries (the EU, Japan), emissions-based burden-sharing (China) or both (Australia, Canada). Hence, the IMF bureaucracy has had a degree of autonomy that has allowed it to adopt positions that run against the preferences of key member states. This autonomy could be utilised to an even greater extent as regards reports and working papers published on behalf of the IMF staff rather than the IMF as an institution, as seen in the staff working paper advocating a Green Fund using the Special Drawing Rights (Reference Bredenkamp and PattilloBredenkamp and Pattillo, 2010). The use of SDRs as a source of climate finance was initially proposed by billionaire George Reference SorosSoros (2009). Importantly, the Fund’s output on climate finance has constituted relatively free (and often low-key) exercises in how climate finance ideally should be addressed, rather than an aspect of its core output on financial stability. Institutional interaction has had less influence on how the IMF has addressed climate finance than on inducing it to address it. Yet, drafting reports together with World Bank officials and relying on OECD data and analysis have both shaped the IMF output on climate finance as has CBDR, a normative idea that the IMF was obliged to address because of the UNFCCC.

All things considered, member state relations have constituted a scope condition for the IMF worldview and for entrepreneurship from the IMF officials: the more autonomy the bureaucracy has enjoyed regarding a policy issue, the more influential these factors have been. The IMF has been able to go further concerning the aspects of climate finance related to its core area of expertise, fiscal policy, than to other aspects of climate finance (e.g. allocations between countries or the implementation of climate finance projects).

12.3 Consequences

12.3.1 International Consequences

The international consequences of the IMF’s climate finance output have been limited both by the small size of this output and by the IMF’s more isolated position in the institutional complex governing climate finance. The Fund occupied its most central position within this complex in 2011, when it – together with above all the World Bank – provided the G20 with input for its discussions of climate finance. Yet, even at that time, the IMF’s proposals for using fossil fuel subsidy reform and carbon pricing of domestic, aviation and shipping as sources had not been developed into concrete proposals by the G20 or other international institutions. Although international aviation will be subject to market-based instrument, this instrument will not provide climate finance for developing countries (ICAO, 2019). The main reason for this is that earmarking – especially for activities taking place outside the country where the revenue is collected – is politically and legally controversial (Reference EschEsch, 2013; Reference Romera and van AsseltRomera and van Asselt, 2015). Likewise, the proposal for a Green Fund financed by SDRs was not developed into a concrete proposal for IMF policy. Nonetheless, institutions such as the UNDP (2012) did pick up and elaborate the notions of using revenues from pricing of international aviation and shipping and SDRs as sources of climate finance. More recent output on improving resilience through financial instruments is more in line with the emerging positions of other institutions and has also informed how they have addressed resilience especially in vulnerable countries. More specifically, the OECD and the World Bank have relied heavily on IMF analyses of the financial and economic situation of vulnerable countries, and recommended that the IMF play an active role as provider of resilience finance to such countries (OECD and World Bank, 2016). Likewise, the UN Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development has relied on the IMF’s analysis of economic benefits of fiscal spending on resilience and recommended that the IMF be involved in how vulnerable countries improve resilience (United Nations, Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development, 2019).

The cognitive idea that carbon pricing, fossil fuel subsidy reform and climate finance are interconnected and the normative idea that this relationship should be strengthened, which the IMF has consistently stressed, has also gained momentum in the run-up to and following COP21 (see inter alia Reference Bowen, Campiglio and TavoniBowen et al., 2013; The Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action, 2019; UNFCCC Standing Committee on Finance, 2016, 2018). Arguably, the IMF output should be seen as an early forerunner of (among international institutions) and contributor to the framing of climate finance in particular (and climate change in general) as an economic issue to be addressed with economic instruments. Climate finance, in itself not an issue that can be framed as addressing the externality of climate changeFootnote 4, has been framed as an issue of redirecting (predominantly private) finance both by the IMF and within the wider climate change complex. As discussed in Chapters 10 and 11, this approach is also common in the G20 and the OECD, and is based on the notion of addressing climate change through economic instruments addressing the barriers to climate action (especially de-risking) rather than climate change as an externality. The IMF did not invent this approach, but whenever it has expressed that finance should be redirected from brown to green, or that resilience should be addressed through financial instruments, it has contributed to the standing of this approach. The IMF’s support for this way of addressing climate finance is important, as it has considerable expertise and authority, especially among international and domestic economic actors (Reference Barnett and FinnemoreBarnett and Finnemore, 2004, chapter 3). On a very fundamental level, since 2010, the IMF has supported the normative idea that climate finance is important, and that developed countries have an obligation to provide it, which is not a given for an institution often accused of furthering the economic interests of developed countries.

12.3.2 Domestic Consequences

The IMF’s calls for using revenue from carbon pricing or fuel or electricity levies as a source of climate finance (IMF, 2011b) has not been heeded by developed states, inter alia because finance ministries are opposed to earmarking revenue and because the constitutions of some states prohibit it. Even the revenue from the auctioning of emission allowances to aviation in the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS), half of which should be earmarked for climate purposes according to the 2008 EU Regulation on aviation in the ETS, has been controversial and the revenue mainly spent domestically, underscoring the opposition to earmarking revenue for international public climate finance (Reference EschEsch, 2013).

The consequences of the IMF’s output are more pronounced concerning output focusing on individual countries, often with a more implicit climate finance focus. Crucially, the Climate Change Policy Assessments have contained very concrete policy recommendations that inter alia might help the countries in question attract public and private climate finance. These Assessments consist of technical assistance, provided on the request of the country that is being analysed. They will constitute one framework for the Fund’s (and also the World Bank’s) interaction with the countries in question regarding climate change, including collaboration between the Fund and the government on issues such as risk management (IMF, 2019d). All in all, in the future, the Climate Change Policy Assessments will mean a closer IMF involvement with the implementation of climate finance. On a similar note, the integration of climate mitigation issues in Article IV consultations may provide a framework for systematically promoting mitigation policies in line with IMF recommendations on policy design. Whether mitigation issues are integrated in these consultations will depend on how much traction the country team believes these issues will have with the government in question (interview with senior IMF official, 19 May 2020).

Given that the IMF’s output on climate finance has been limited, it is difficult to discern direct influences on the negotiation positions on climate finance or the provision or implementation of such finance in the United States, United Kingdom, India, Indonesia or Denmark. For instance, the Fund’s argument for focusing on adaptation risk and resilience and on shifting private financial flows has resonated domestically, but given that such arguments have come from a range of different actors and institutions, it is difficult to discern how influential the IMF has been in this respect. Nor has the IMF influenced the position of the climate finance issues it has addressed on either public or policymaking agendas, inter alia because some of these ideas regarding generating resources had already been proposed in the 2010 UN High-level Advisory Group on Climate Change Financing report (United Nations, 2010) without much effect.

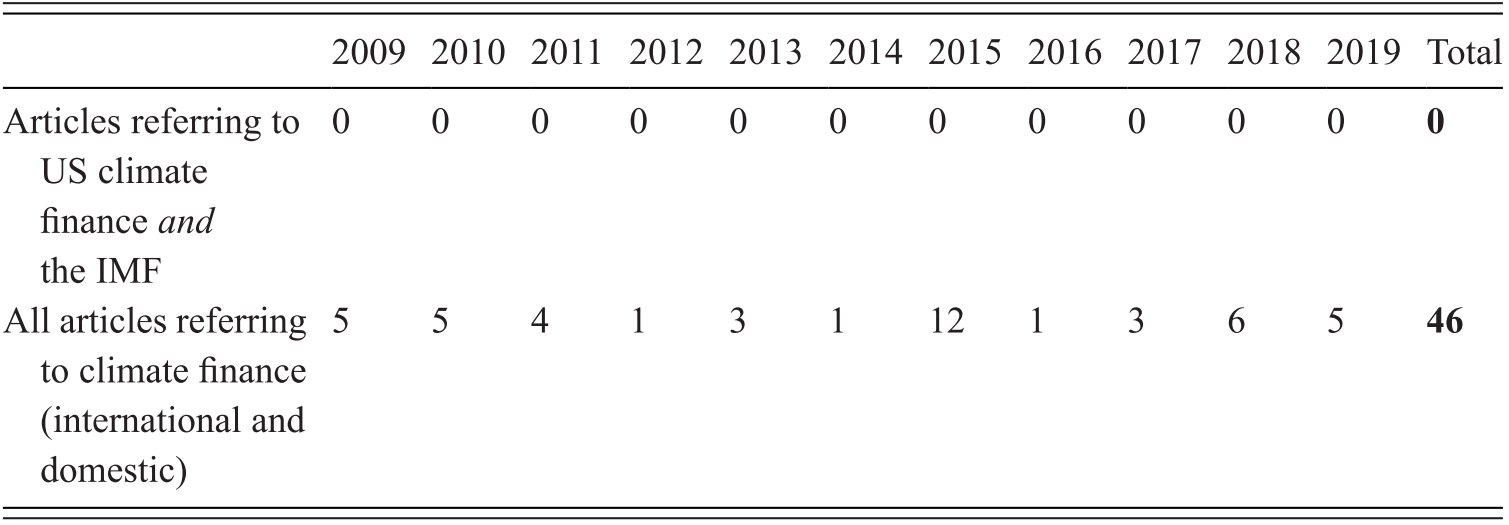

In the case of the United States, there has been limited cognitive and normative influence from the IMF on policymakers, in spite of the generally close interaction between the US Treasury and the IMF made possible by being headquartered in the same city. Fundamentally, much of the IMF output has been in direct opposition to US positions on climate finance, for example, the notions of burden-sharing and of using carbon pricing revenue as a source of climate finance. The idea of federal carbon pricing was largely abandoned by the Obama administration after the defeat of the Waxman–Markey proposal for an US emissions trading system in 2009 (Reference MacNeilMacNeil, 2016). Furthermore, the IMF has not been linked to climate finance at all in either the New York Times or the Washington Post (see Table 12.1).

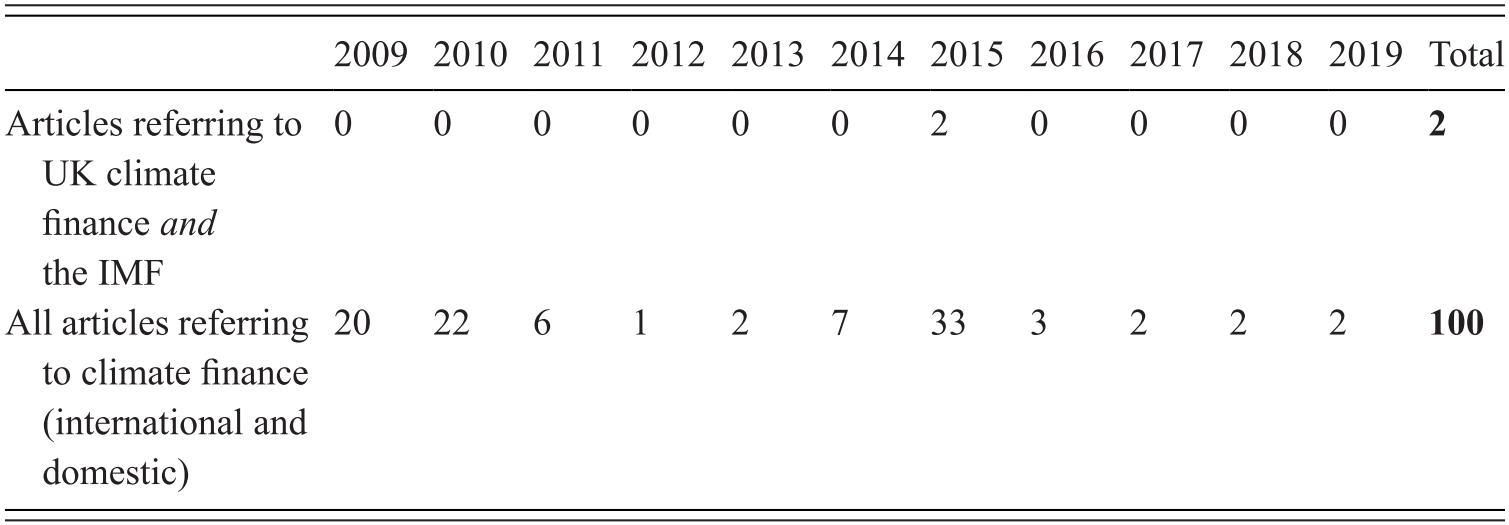

The IMF has also not yet had a discernible impact on the UK position on climate finance. While the IMF has provided important data for G20 discussions of climate finance that have involved the UK (and the United States, India and Indonesia), this constitutes an influence on the G20 rather than directly on the United Kingdom. The United Kingdom is one of the countries which will have mitigation issues included in their Article IV consultations although at the time of writing these have been postponed due to the Corona pandemic. On the public agenda, the only references to the IMF in relation to UK climate finance consist of two brief references to a 2015 meeting on climate finance in the margins of the IMF and World Bank annual meeting in October 2015 (Editorial, 2015).

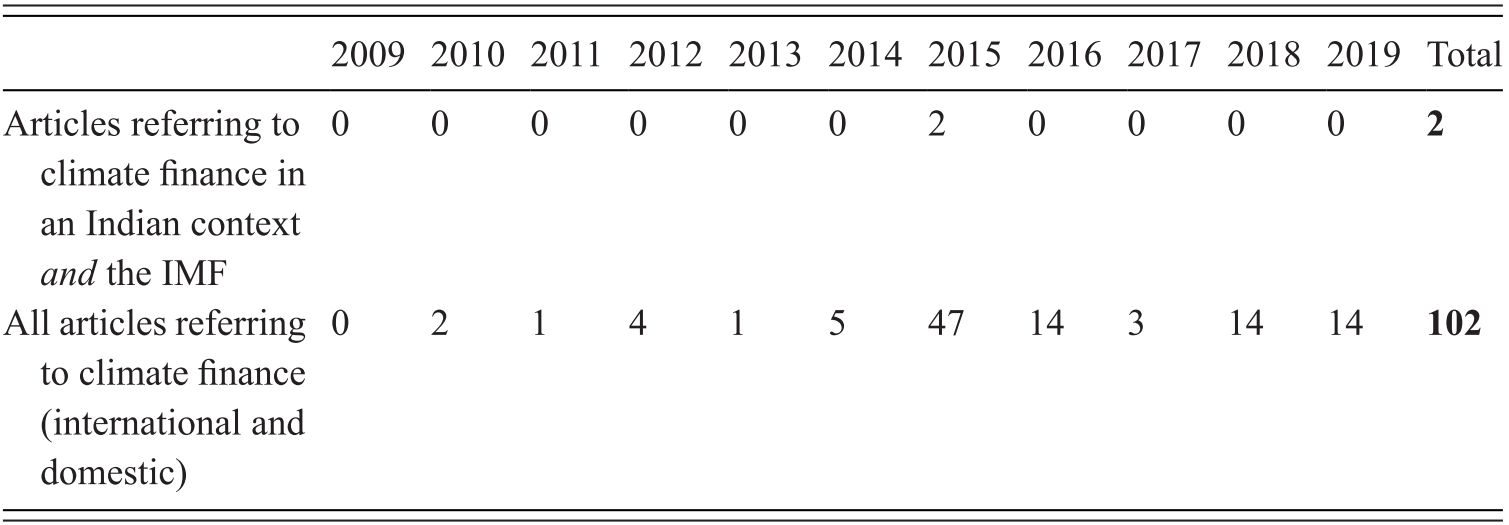

India and Indonesia have also interacted with the IMF concerning climate finance in the context of the G20. Beyond this, the limited IMF output on climate finance has had no discernible influence on climate finance in the two countries or on the negotiation positions. Indian media has mentioned the IMF only in the context of climate finance once, namely the aforementioned 2015 meeting on climate finance in the margins of the 2015 IMF and World Bank annual meeting (Reference MohanMohan, 2015b).

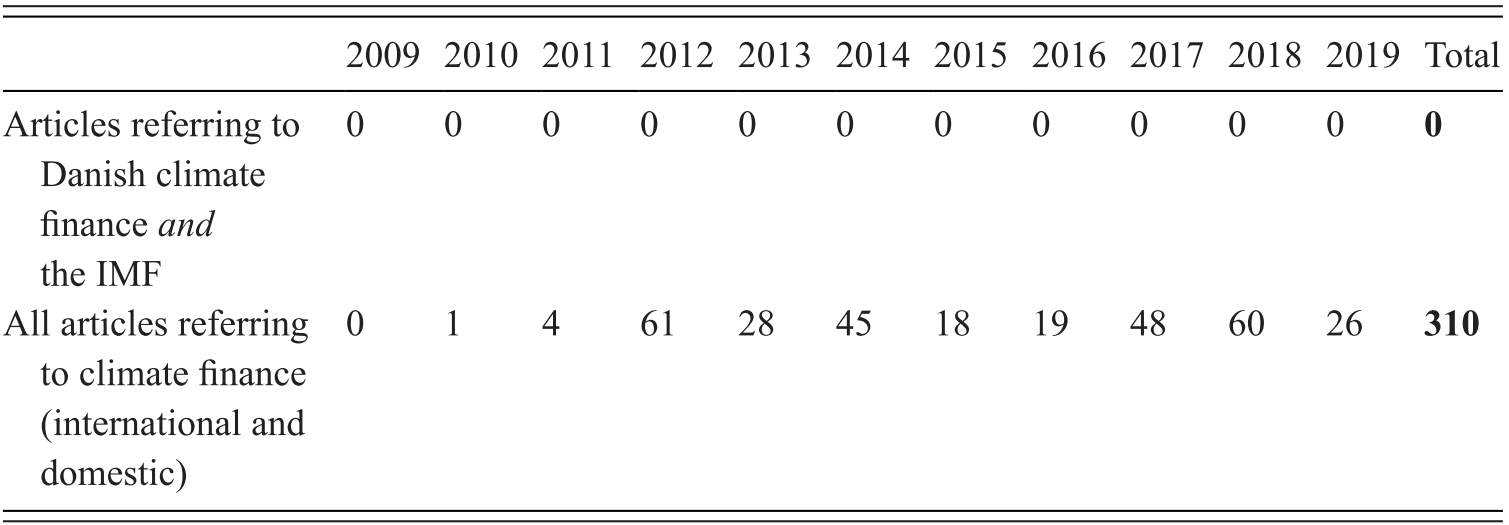

In line with the other countries, at the time of writing, it is, in the case of Denmark, not possible to discern any IMF influence on climate finance, although this may change when the Article IV consultations with Denmark start including mitigation issues as planned. There have been no identified references to the IMF and climate finance on the Danish public agenda (see Table 12.4).

Table 12.3 Climate finance and the IMF in the Indian media: The Hindu and Times of India

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Articles referring to climate finance in an Indian context and the IMF | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| All articles referring to climate finance (international and domestic) | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 47 | 14 | 3 | 14 | 14 | 102 |

12.4 Summary

The IMF output on climate finance has been knowledge-oriented and relatively limited, underscoring that it has not been a key part of the IMF’s portfolio. While the early reports from 2010–12 focused on generating climate finance, particularly through domestic and international (on aviation and shipping) carbon pricing, later output has also stressed shifting investment and improving climate resilience. The economisation of climate finance has been pronounced through all of this, with the Fund proposing economic instruments such as carbon pricing and insurance mechanisms, and emphasising efficiency as an objective. The IMF output has mainly been the result of institutional interaction with the G20 and officials acting as policy entrepreneurs, and has been shaped by its institutional worldview, which has been more limited by member state relations than has been the case regarding fossil fuel subsidies. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the low-key output of the IMF has only had limited consequences at the international level, and the analysis has not been able to identify any consequences at the domestic level thus far, although the integration of mitigation concerns into Article IV consultations and other bilateral interaction may change this.