‘[e-books are real because] In publishing, all books are ebooks before the files are sent to the printers.’

‘Actually I also judge the cover [of an e-book], even though it’s not like a printed one … if I see one that obviously has been badly done on Photoshop or something like that I’m going to go, “No, just no. No way. I don’t trust it.”’

‘[an e-book is real] Because it’s pretty much the exact same as a physical book except I can read them in the dark!’

‘[an e-book is not real because] not the same product.’

A reader enters a bookshop. Not a physical bookshop, with a fixed location and a finite stock selected to appeal to a defined clientele; the reader isn’t weaving between shelves of signed first editions in Toppings of Ely, or ziggurats of business bestsellers in Hudson Books at Logan International Airport. Instead, it’s a bookshop of two dimensions, contained on a glowing screen. It’s infinitely thin and, thanks to the millions of titles on offer, for all intents and purposes infinitely wide. Bits of book flash across the interface: gifs of cover images, blurbs ‘From the Back Cover’, page counts and colophons, an arrow to click to ‘Look Inside’. Whether these fragments relate to any print binding is not easy to determine. Personalised suggestions jostle with sponsored products, while ratings and rankings and recommendations (genuine and fake) swoop and dive into their field of view. The reader is not naïve: they know that none of this landed at the top of their screen by accident. But how they sift through the information on offer, how they weigh up evidence in evaluating books and authors, and how they make a judgement on what is worth their time and (sometimes) money speak to what counts in deciding whether a given book counts. And for e-books, when, and whether, realness is required.

This chapter investigates first encounters with e-books and the processes by which readers evaluate a given work. It examines how trust is established and legitimacy constituted in practice, considering realness and bookness in terms of a given e-book’s status as cultural product and cultural object, and the ways in which e-book legitimacy can hinge on relationship to a print edition or to traditional mainstream publishing. It analyses the reader’s rationales of realness on the theme of equivalence, contrasting conceptions of an e-book as real because ‘bits and ink – there’s no difference’, and unreal because they are ‘not the same product’.1 Finally, it considers the digital proxy and the ersatz book as two discrete types of e-book unrealness.

In making a judgement as to the legitimacy of a given e-book, prospective readers confront separate but entangled stigmas: not only the lower status of digital books, a ‘format deemed lacking in cultural value’,2 but also the lower status of self-publishing. Examining how readers interrogate an e-book requires also examining how creators present that book: how publishers and authors (and publisher/authors) work to anticipate readers’ questions, attempt to allay their fears, and collaborate to constitute credibility. Paratextual theory offers the tools for such investigation.

Paratext: ‘Threshold of Interpretation’

Paratext is ‘what enables a text to become a book and to be offered as such to its readers and, more generally, to the public’.3 If there is an element of audacity in putting forward a zip file of data and describing it as a book, Genette reminds us that there is an element of audacity in putting forward any text and describing it as a book. No matter how traditional, conventional, or even derivative a text might be in some ways, without ‘productions, such as an author’s name, a title, a preface, illustrations’ (though paratextual elements range much further than this), it is not yet ‘endowed with significance’ as a book.4 Paratext is what creators use to not only ‘present’ but also ‘make present, to ensure a text’s presence in the world, its “reception” and consumption in the form (nowadays, at least) of a book’ [emphasis his].5 It is ‘the fringe of the printed text which in reality controls one’s whole reading of the text’,6 embracing a wide array of elements that adjoin the text, and offer instruction and context that guide the reading of that text. Examples range from chapter titles to book titles, cover design to advertising copy, personal inscriptions to Woolf’s (initially) private reflections in her diary on the process of creating Jacob’s Room. Paratext can convey a work’s status bluntly, as with the word ‘classic’ printed above the title of a novel, or quietly, as with printing the same novel in a small and inexpensive format that, by its very economy and plainness, declares itself a student-friendly edition of a canonical text.7 Genette developed his concept of paratext in the 1980s, exploring some aspects in Palimpsestes (1982, first translated into English in 1997) before a more comprehensive treatment in Seuils (Paratexts) (1987, translated into German in 1989 and English in 1997).8 He refined his ideas in a time when e-books were obscure, almost a curiosity, yet they have found new life in the examination of book-objects hatched generations later. Paratext’s very utility and versatility has made Corinna Norrick-Rühl question whether it should be described as ‘theory’ at all, suggesting that it might instead be viewed as somewhere between theory and toolkit.9 But whether theory or kit, paratext is ideal for exploring contemporary questions of legitimacy and reputation, offering a means, comprehensible between academic disciplines, for discussion of fluid as well as fixed elements.

E-book Paratext: Crossing the Threshold on Screen

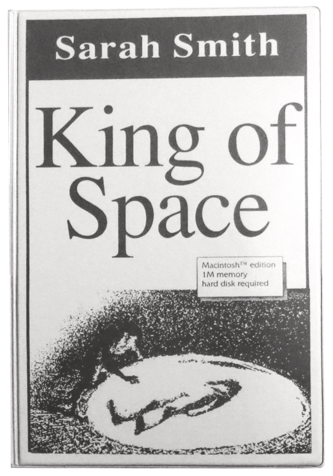

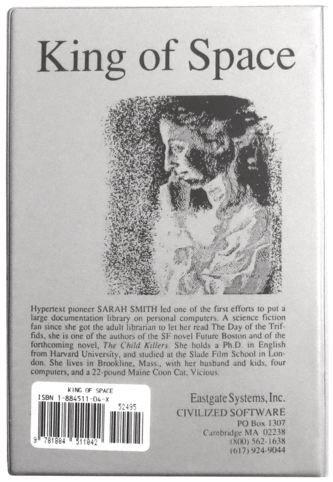

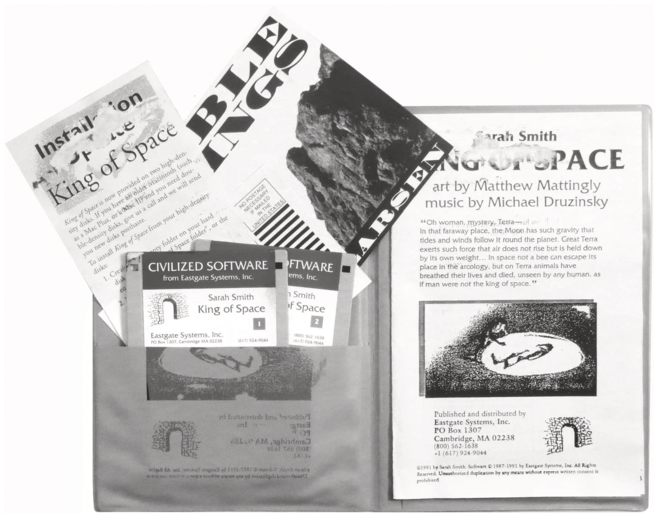

Paratext advances many agendas at once. For any work of literature, paratext is tasked with establishing value and worth, ‘ensur[ing] for the text a destiny consistent with the author’s purpose’ by positioning it on multiple axes and anticipating the concerns of multiple audiences.10 But paratext can’t dictate; it can only negotiate. It is the ‘zone of transition, but also transaction’ where authors, publishers, and readers meet, ‘a privileged place of a pragmatics and a strategy’, and paratextual messages are not instruments of control [emphasis his].11 ‘A novel’, as Genette put it, ‘does not signify that “This book is a novel,” a defining assertion that hardly lies within anyone’s power, but rather “Please look on this book as a novel”’.12 Paratext, for such a work of fiction, simultaneously labours to present it as a novel and as a good novel, to be evaluated according to the standards of the desired genres, traditions, audiences, and markets. The strain of serving multiple audiences can be particularly intense where publishers are attempting to take advantage of the possibilities of digital literature while pursing credibility in environments designed for print. An example is the 1990s interactive literature publisher Eastgate shipping floppy disks in packages ‘safe for bookstores’ (see Figure 2.1), with codex-like covers and spines, pitched to booksellers on the same kinds of in-person visits used by mainstream publishers for print books, and adopting ‘establishment’ intellectual property policies aligned with the interests of university tenure committees and ‘traditional bookselling’ practice, despite the heavy financial burdens these imposed.13 As Dene Grigar observes, ‘the folio, which was made to resemble a book that could sit on a shelf, served as a breadcrumb leading from the late 20th Century print culture to the early 21st Century digital one’.14

Figure 2.1 Eastgate Systems, Inc. packaging of Sarah Smith’s ‘King of Space’ (1991).

A novel on screen must answer all the questions put to a novel in print, while also addressing concerns specific to digital novels. Foremost among these are concerns about the text’s relationship to traditional mainstream publishing. Was it chosen? And if so, by whom? Key evidence of industry approval, and if so the degree of investment by members of that industry, is sought in existence in print. ‘If it hasn’t been backed by a publisher’, as one focus group participant in my own study put it, ‘instantly my mind goes to, “Well, why not?”’15 Ultimately, the brutal question digital novels must answer is ‘if the publisher wasn’t willing to invest in it, why should I?’16 How e-novels, and any e-books, respond via paratext – how authors try to encourage favourable interpretations, and how readers try to seek reliable information – reveals much about how the paratextual transaction actually functions for books on screen.

Proximity and Authority

Genette’s grouping of elements into five key dimensions (spatial, temporal, substantial, pragmatic, and functional) brings to light patterns, commonalities in aims and tactics over time, and insights into the presentation and reception of texts in the real world. However, much scholarship to date has bypassed Genette’s distinctions, implying that because his categories date from the era of print, and never had firm boundaries in the first place, engaging with them is fruitless.17 Birke and Christ propose retiring most, if not all, of Genette’s twentieth-century, text-based, deliberately flexible subcategories, arguing that ‘context (or the universe of texts) moves so close to the text that “thresholds,” paratextual elements that negotiate the space between text and context, become increasingly difficult to isolate and identify’.18 Simply abandoning his distinctions, however, squanders a vocabulary ideally suited to discussion of textual boundaries; a vocabulary that is and always was open to evolution. The boundaries of ‘multiform and tentacular’ paratext are defined by Genette as subtle and mutable, inevitably taking different forms in different contexts and at different times.19 McCracken’s approach of ‘augmentation and modification’20 allows for nuance, and selective application of relevant subcategories, rather than a wholesale banishment of taxonomies informed by centuries of book history, and which frequently draw connections between contemporary paratextual strategies and related approaches from the print and manuscript eras. To do otherwise would sever e-books from the reading and publishing traditions from which they spring.

Discarding the spatial dimension is particularly dangerous, as proximity to the text can play a critical role in conveying to readers authorial intention: the intention without which an element is not paratext at all.

‘Respectful Distance’

In the spatial dimension, Genette divides paratext into two broad categories: peritext and epitext. Although both ‘surround and extend’ the text, in a printed book, peritext is ‘within the same volume’: printed and bound with the words of the text itself.21 A typical example is a cover, but more deeply embedded are types such as illustrations, epigraphs, chapter titles, and the author’s name (and all that such a name evokes in terms of gender, nationality, class, etc.). Epitext, in contrast, is ‘at a more respectful (or prudent) distance … located outside the book’.22 An example could be a descriptive entry in a publisher’s catalogue that seeks to place the book under a science, psychology, or self-help category, or an author biography that emphasises credentials, or simply demographics such as age. But epitext could just as easily be a recording of a public talk by the author, perhaps conveying some of the same information, verbally or visually. This distinction allows us to consider separately elements attached to and elements distanced from the text, and to examine the influence of elements bound in print but more loosely affiliated in digital format.

To be paratext, elements must be ‘characterised by an authorial intention and assumption of responsibility’, affirmed by either the author or the publisher whom they have empowered to distribute and represent the text.23 Hence, a book review in a broadsheet is outside the boundaries, until such time as a quote is plucked from that review and placed in a press release (epitext) or printed on the back cover of a subsequent paperback edition (peritext). That which is not authorised remains metatext: commentary about a book, potentially influential, but not part of the transaction between reader and creator. Proximity matters, not least because classic paratextual theory comes from an era where the more closely bound an element was to the text, the safer it was to assume that it was indeed authorised. While discernment is always needed (deceptive paratext having a long tradition in print), epitext by its distanced nature demands a greater degree of scepticism and scrutiny. Readers typically confront epitext in the rush of the outside world, encountering some elements but not all (no one but an author’s publicist or mother could realistically track every output), and continually sifting the authorised from the unauthorised. Print peritext, in contrast, comes from an object of finite size and at least some integrity, where additions may be discernible as additions (as with comments scribbled in the margin) and any bound element difficult to ignore. In effect, in Genette’s view, any print peritext element, even a decorated end-paper, ‘cannot not’ be influential [emphasis his].24

Establishing Legitimacy: Digital Elements of the Peritext + Epitext = Paratext Equation

Much epitext is now digital for books in any format, as author websites and tweets, author-generated BookTok and Bookstagram content, publisher-generated book trailers on YouTube, recordings of public events, and online versions of press interviews invite readers to access the author (or at least their public authorial persona) digitally even if they are still accessing the text itself in print.25 In my own study, participants’ responses emphasise how integral personal research is to their book selection processes: by the time a book is in one’s hands, ‘you have an idea’ of what to expect, because ‘you’ve read about it already’.26 Recommendations are very common, but personal investigation is even more so. But for e-books, digital epitext is, in some ways, at a less ‘respectful distance’ than is the case for print books. If downloading an e-book is quick and easy, Googling the author is even quicker and easier. For readers using tablets, smartphones, and personal computers, the two tasks – obtaining books and researching books – take place on the same device. Some models of e-readers can, with effort, still be kept offline, relying on USB cables to transfer titles from a separate connected device, but WiFi (such as Whispernet-branded connectivity, which Amazon once made central to its Kindle sales pitch) makes inviting the retail space into the device, browsing the bookshop via e-ink, the convenient default option. ‘During the reading process one can easily tap a tablet’s touchscreen to view comments, ratings, reviews, and author information and commentary without putting the device aside.’27 For an e-book, digital epitext is, in a sense, attached to the physical object, akin to precarious peritext, and potentially filling the information gap left by peritext such as front matter that readers knowingly skip. Unlike print books, which regularly come into their possession by the design of others (as with gifts, or by chance, as with books left behind in holiday cottages),28 sources of e-books are almost invariably prominent, even obtrusive. The e-books participants obtained came from identifiable sources: public libraries, Project Gutenberg, and university libraries most often, but sometimes an ‘e-mail direct from author (PDF)’ or a download from Pirate Bay.29 Even a PDF found via Google search is downloaded from somewhere, and e-book gifts, rare as they are for these participants (only 4.0 per cent had received one in the past twelve months) are typically ‘given’ via a link to a website from which the recipient can download their present. (It is part of what makes an e-book collection a walled garden: little enters without the owner’s permission, little is shared, and, aside from expiring loans and repossessed Orwell novels,30 nothing ever truly leaves.)

Proximity matters because it, to a large extent, determines what elements readers use, and what elements readers trust. Closeness to the text still suggests (even if those signals are not accurate) that a given message is truly from the author or publisher and not from the device, and hence meaningful. Distance suggests that a given message is not from the author or publisher (and, if genuinely objective, meaningful in a different way). In terms of closeness, and suggestion of meaning, few paratextual elements are as prominent as a cover image.

Judging E-books by Their Detachable Covers

McCracken speculates that ‘given this expanded network of epitexts for e-books, the front cover is perhaps less important now as a marketing device than it is for print books’,31 but data from my study suggest that it remains an element of paramount importance. These participants describe relying on it not only for information about the type of book but also for clues as to its status and trustworthiness. If anything, the cover may take on greater importance when some other signals of publisher investment, such as paper quality, are no longer available for consultation.

Covers are an eminently reasonable place for readers to start when forming their initial assessments of how much investment and expertise have gone into a particular book. Cover design represents daunting effort, whether by a demotic author or, in the case of a mainstream published book, the combined input of design teams, editors, and sales and marketing specialists32 – even where images may be part or wholly AI generated, humans are still, at time of press, required to define the task, write the prompts, evaluate and refine the outputs, and shepherd the chosen design through the gauntlet of publisher and retailer approvals. Readers risk a bit of money and a great deal of time on their choice of book. Participants in my study frequently underscored that evidence of others’ risk, what publishers have invested themselves, ranks alongside the demonstrable skill of the author and editor in determining whether a given novel is worth their own money and time.33 They were sceptical of supposed difference, noting that ‘there used to be this perception that an e-book cover worked in a different way to a print book cover…I’m not entirely sure if that’s true’, while reporting that in their own experience, ‘when you transfer to e-books…that [cover] image still plays a role and also the blurb’, and that they ‘tend to judge the book by its cover no matter if it is print or digital’.34 A ‘badly done’ or an ‘unprofessional’ cover, therefore, instantly destroys any possibility of trust in the book. Not only does it suggest self-publication but it also signals to them carelessness: a book where ‘the cover looked really dodgy’35 is expected to remain dodgy throughout. ‘Cheap or unprofessional’ covers ‘badly done on Photoshop’36 were perceived as both typical of self-published e-books and quite reasonable grounds for rejecting a title.

When participants discussed using covers as indicators of quality, it was not a matter of trusting covers but rather trusting their own experience with covers. They had faith in their ability to decode the paratextual messages authors and publishers have placed there, relying on mental models of a printed book for their information-seeking task much as experienced users of traditional libraries have been observed to apply mental models of traditional libraries to digital library searches.37 A further complication comes from the difference between stable formats, such as PDF, and reflowable formats, such as .EPUB and Amazon’s .AZW. Not only does reflow dynamically change aspects such as margins and line breaks (usually for the worse, from a design point of view) but the option of customisation also raises issues of discerning authorial responsibility.

Discerning Authority in an Adaptable Book-Object

Peritext is and always has been porous. Movement between categories of peritext, epitext, and metatext is expected and commonplace, for print as well as for digital books. A given element may move in and out, included in this edition, excluded in that, and perhaps eventually achieving its ‘ultimate destiny’: to ‘catch up with its text’ and become part of the text itself.38 The only things that are unusual about promotion or demotion of elements in e-books are (a) the degree of reader involvement and (b) the degree to which adaptations are reversible and sometimes invisible. (However, Galey argues that the near-infinite fluidity imagined by some early theorists of the e-book is greatly overstated.)39 Customisation at the point of purchase is not unknown for print. A manuscript owner in 1100 or a bookshop patron in 1720 could select their binding or indeed leave the pages in a stack held together with string. The modern reader can choose between hundreds of print editions of Pride and Prejudice, selecting paratext that emphasises the novel’s status as a classic, or its central romance, or its various film adaptations, making a conscious decision to match the edition to their conception of and/or reading strategy for the text (or perhaps picking up whatever is closest, and accepting discordant paratext as the price of convenience). But for the e-book, peritext is not only ‘flexible’,40 it is perpetually so, at the point of purchase and at almost any point beyond: ‘fluidity marks the electronic text in contrast to the stationary nature of print on a page: adjustment of font-size, brightness, contrast, and landscape or portrait orientation’.41 If one is a typical reader, making use of multiple modes and platforms (in my surveys, most respondents who read e-books at all had used two or more different devices for reading in the past twelve months) one may be simultaneously using a smartphone app for one book and a desktop browser window for another, or taking advantage of the ‘save my place’ feature on Kindle to swap between devices for the same text, and encountering it through two equally but differently personalised interfaces. There is not one personal version but the potential for a plethora of personal versions, appearing in sequence or simultaneously, optimised for different settings and situations. But assuming that customisation effectively obscures authorial intention, rendering any element useless as peritext (or even non-paratextual) is speculating ahead of the facts.

Precarious Authority

Genette designated a specific category of paratextual elements distributed in or immediately around the print object but not affixed to it.42 A ‘precarious peritext’ is an element like a French ‘please-insert’ that, while created and authorised by the publisher, remains a slip of paper easily separated from the bound copy, unlike ‘durable peritext’ elements such as bindings and tables of contents.43 While it would be on one level simple to reclassify all e-book peritext as precarious, that would ignore the way peritextual matter is actually stored in an e-book file, and the ways in which readers experience peritext on the level of an e-reading device.

Formatting as experienced by the reader can be highly adaptable for a reflowable e-book file, with elements such as font, margins, and line spacing adjustable via device or app settings, and elements such as pagination adjusting dynamically to accommodate setting changes. But these setting changes, stored in a local file, do not change the e-book file itself. (The settings are meant to endure over multiple reading sessions, but users of e-reading apps are all too familiar with the software crashes that return settings to default.) Opened and read on a dozen non-synced devices, the file could be experienced in a dozen guises. An e-book ‘is simply a disguised zip archive’,44 containing a series of separate files where text, images, formatting, and so forth are stored discretely, to be interpreted and displayed by the interface software each time the e-book file is opened. It is a simple exercise to change file type for an unprotected .EPUB file and view or alter the constituent files, and only slightly more complicated to strip out Digital Rights Management and do the same for a protected .EPUB or .AZW file (as some participants in my study do, despite the fact that this violates terms and conditions from Amazon and some other retailers. Please see Chapter 4 for more on these participants’ e-book customisation). But such alteration would not take place by accident. The reader would need to take a series of steps, such as downloading specialist software such as Calibre (and, if a coding novice, downloading detailed instructions) to make a permanent change. In this way, e-book peritext is, in fact, more durable than print peritext: while a file can become corrupted, it can only be intentionally, and not accidentally, dismembered or defaced.

Where e-books have conspicuously less integrity than print books is the invisibility of such permanent changes. Kirschenbaum notes how eighteenth-century legal scholar William Blackstone argued that legal records be kept exclusively on rag linen paper rather than leather, wood, or stone not because paper was durable, but because it was not durable: unlike robust surfaces that could be scoured clean, the paper document was ‘fragile enough to readily expose any attempt to tamper with or change it’.45 Many elements of print paratext can be forcibly removed, like a torn-off paperback cover or a razored-out colour plate. But such durables of print typically leave scars: a defaced and visibly diminished text with gaps, spaces where meaning should be, that invite a frustrated reader to go looking for what’s been withheld. (The status of removable paper dust jackets, which were for much of the nineteenth century treated as disposable protective wrapping, but are today desirable elements of a new hardcover book and essential for that book’s sale as an undamaged copy, highlights the importance of context in determining what leaves a gap and what does not.) The question is whether the removal of electronic paratextual elements (including elements that don’t mimic print, like dynamic indexes) leaves scars and gaps, or whether, as Galey identifies in his case study of a digital edition of The Sentimentalists released with incorrect ContentID information, ‘readers [of the corrupted version] would have no way of knowing that they have not, in a basic sense, read the same novel as other readers’.46

Short of such Calibre-enabled file-level tampering, what is mutable in the reflowable e-book is not the file but the interface: not only because it is customisable but also because it is perpetually remade. As a ‘web page in a wrapper’47 the e-book is read (much like a webpage where content and formatting instructions are distributed over a series of text .XML and image .JPG and .CSS stylesheet files) through mediating software that compiles input from various sources. Rather than storing the output each time, the software stores the data needed (including user settings and, if all goes well, the user’s progress through the text) to make it afresh in the next session. In a sense, the version a reader is actually looking at on screen, generated from the instructions in .EPUB or .AZW files and associated settings and progress files, ceases to exist when the reader looks away: not only when they ‘shut’ the book (closing an application on their tablet or opening a different book on their e-ink reader) but also every time they turn the page. (Leading to the experience that has frustrated so many readers: flipping backwards in an e-book to check something on a previous page and discovering that the pagination has changed, and the words one was looking for have moved despite no changes to font or other settings. This phenomenon of wandering text is identified in some studies as a potential barrier to reading comprehension, retention, and/or immersion, interfering with a reader’s ability to construct a cognitive map of the text.48 For more on wandering text as part of the digital reading experience, see Chapter 4.) Kirschenbaum, examining Max Barry’s 2011 novel Machine Man, where the author used a software development version control tool to both preserve all interim versions of the text and post these accumulated versions to his personal website, concludes that ‘in this model the text becomes less an object or an artefact and more like an event’ in a programming sense.49 If that model can be extended to cover an .EPUB or .AZW file where the inner workings are less visible than Barry’s but no less intricate, one might consider the reflowable e-book as experienced by the reader as an event rather than an artefact. If so, readers might be observing the early generations of an additional subcategory of paratext: event paratext. Such a type of paratext would contrast with and function separately from artefact paratext; potentially as a paratextual equivalent of Drucker’s performative materiality, one that similarly ‘always occurs only in real time and is distinct in each instance’.50 This problematises present conceptions of digital paratext and opens the door for an expansion of paratextual theory. If there is such a thing as event paratext, and readers are viewing and responding to a set of paratextual signals that exist but only for a single viewing, the reflowable e-book is not real, and not real because it is a digital proxy: in this case, a digital proxy for a digital artefact. (And if the reader is conceptualising the e-book itself as a digital proxy for a print edition, doubly distanced.)

Proxy status, and subsequent unrealness, does not by itself stop paratext from functioning as paratext. Genette’s categories embrace mediated categories, such as interviews, conversations and colloquia.51 But it does emphasise the greatest problem with event paratext: discerning authorial intention.

Changes or additions made to a text without the author’s or publisher’s approval are not paratext. The challenge facing the reader is determining which aspects of the e-book they are viewing on screen are intended and which are accidental (e.g. in the case of a corrupted file such as the edition of The Sentimentalists examined by Galey) or imposed (e.g. in an e-book that includes promotions for other books overlaying the final pages, and it may be difficult to tell which were included by the publisher and which were generated by an e-retailer’s algorithm). Mutability does not of itself make a particular aspect irrelevant, or even ambiguous. Font, a prime example of a feature controllable via user settings, can nonetheless be initially set by the publisher as part of the .EPUB or other e-book file (settings have for most of the Kindle’s history changed on a book-by-book basis, but on some newer models and the Kindle app changing font for any book can change font for every book). Not every book has ‘publisher font’ as a menu option. But where that option does appear, the very existence of ‘publisher font’, even when not chosen, focuses the reader’s attention, however briefly, on the publisher’s original intentions: the invitation to alter is also an invitation to contemplate paratextual choices, highlighting them in a different, but far from trivial, way. (A sobering check on this new way of communicating with readers comes in the form of limited font libraries. Many e-reading devices are loaded with only a handful of popular fonts and, if presented with a file set for anything else, will default to the manufacturer’s choice; in Galey’s example replacing Joanna with Georgia on Kobo,52 but on Amazon apps and Kindles typically reverting its own custom Bookerly font. This severely constricts publishers’ options, much in the way that production process limits on colour, size, layout, and so on would constrict other design options on a print edition.)53 This engagement could even, at least for some users, be considered ludic, a game-like interface where playful interaction is not a means to an end but part of the experience. Perpetual customisation, in some ways, exemplifies the transaction element of paratext, where authors and publishers do not and indeed cannot dictate, they can only meet readers on the threshold and make proposals, from which the negotiation may begin.

The invitation to customise, to join publishers and authors at the threshold, does not automatically make a text less important or desirable: these options are only promoted as features because retailers believe they add value to the product. But this form of customisation undermines claims to realness in two ways. One is that drawing attention to publisher-suggested settings foregrounds the idea of an original, valid version, true to the author’s intentions, that the e-book-as-proxy emulates with greater or lesser fidelity: as one respondent put it, explaining why they consider e-books to be real books (but not without some qualification), ‘I will confess that Kindle and even Google Books seem less like real books because their fonts and text sizes can be changed. I appreciate those options, but I still prefer to see whatever the author, designers and publishers intended’.54 The second is that by selling proxyhood as a feature, retailers remind readers of the commercial value of unrealness. If ‘an ebook is a shadow of a real book’ or ‘electronic materials feel like a copy, a pdf of the book’, as two rationales for e-book unrealness put it, that shadow is cast by something: the ‘copy’ is still connected to the book, and gains value, and meaning, from that connection.

Immutable Impressions? The Case of Choosing for Reasons of Selection

The e-book’s problems with reputation – the suspicion and uncertainty readers feel when trying to judge whether it is a ‘proper book’55 – impact its legitimacy. Results from one suite of questions from my survey, those on selection, offer further insights into ways that trust in print, and lack of trust in digital, is driven by beliefs rather than experience.

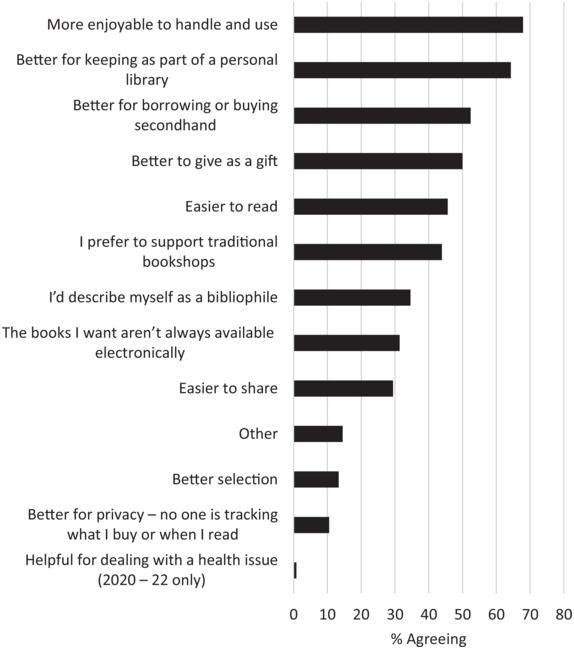

When it comes to one form of trust, faith in the selection of books available in a given format, print enjoys what appears to be an unearned advantage. Overall, ‘better selection’ is not an important motivator: only 13.3 per cent of all respondents choose print for this reason, making it among the least common reasons in the survey (Figure 2.2). (In my surveys, I asked about reasons for choosing print and digital not to identify affordances – these have been widely studied, from industry and academic perspectives, and exhaustively discussed in the popular press – but to look at their relative importance, and how they relate to book-reading and book-buying behaviour.)

Figure 2.2 ‘When you choose print, what are your reasons?’ (All readers, all years).

What is interesting is the degree of disconnect from recent digital reading experience. For print selection (the only form of selection print-only readers were asked about), there is no difference between print-only readers and e-book readers. Those who agreed were somewhat more active consumers of print books, more likely to have obtained one in the past twelve months from Amazon, a library, and secondhand bookshops. However, other than an increased likelihood of having used Project Gutenberg in the past twelve months, there were no links to sources of e-books, e-book genre, or reading device usage. And there were no links at all to reasons for choosing e-books – even to choosing e-books for reasons of better selection. (In contrast, despite its relative unimportance as a motivator, choosing print for reasons of better selection is positively and significantly correlated with every other print motivator in the survey, other than choosing print because it is ‘helpful for dealing with a health issue that can interfere with my reading’, a question added for the 2020–22 surveys only.)

Digital Selection

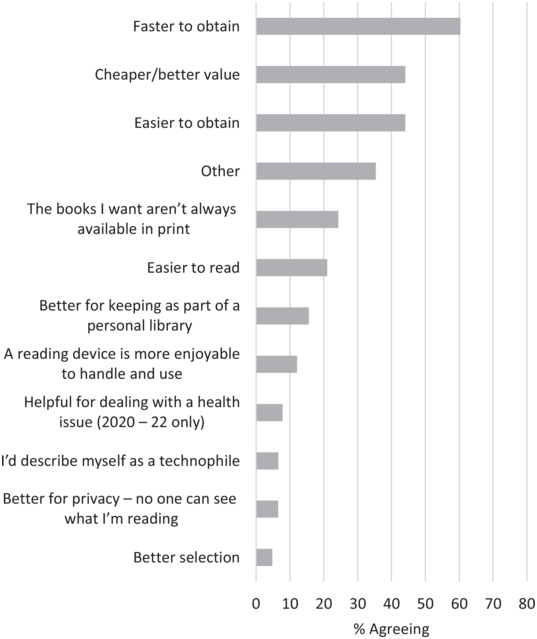

The rise of digital self-publishing, combined with that of digital-original imprints (which retain the gatekeeping functions and many editorial processes of traditional publishing, only without print editions in the first instance), the number of books only available in digital form has increased exponentially.56 At the same time, continuous digitisation efforts, in the form of collection-led initiatives from individual publishers as well as libraries, archives, and Google Books, and by independent actors such as Project Gutenberg,57 have swelled the ranks of older print-original material available in digital form, and where original editions are out of print all but replacing print as the readily available option. Newly published books are now released with a digital-access policy in mind, and it’s an unusual and conspicuous choice to sacrifice potential sales (and antagonise readers who rely on e-books for accessibility reasons) by releasing any book in print without an accompanying e-book edition.58 But despite the near-universal availability of digital as an option for new books, and increasing availability of digital as an option for older works, readers in this survey are near-unanimous in their judgement that selection is not a reason to choose digital. A mere 4.8 per cent of e-book readers choose e-books for this reason, making it the least important motivator in the survey (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 ‘When you choose digital, what are your reasons? (E-book readers only, all years).

As some qualitative responses explicitly noted, ‘better selection’ does not necessarily mean ‘wider selection’. A number of participants cited self-published books as a key source of material they wanted to read, and hence a key reason to choose digital reading.59 Others, however, described self-publishing as the source of an oversupply of low-quality or otherwise uninteresting books that made it more difficult to find books they actually wanted: ‘I don’t have the stamina’ or ‘life’s too short, I’ve got 17 unread novels already on my shelves without looking for bloody self-published books’.60

Examining the tiny group who choose e-books for better selection reveals a pattern similar to that of print: ties to values and preferences are considerably stronger than ties to behaviour. Links to sources of e-books and types of e-reading devices used are negligible61 – the last being particularly remarkable for the portion of data collected under pandemic conditions, when intermittent lockdowns temporarily disrupted access to print books and increased access to digital ones. But those who choose digital for reasons of selection could be described as all-around digital enthusiasts: more likely to share most reasons for choosing e-books, including the exceptionally e-bookish values of preferring digital for personal libraries and considering an e-reading device more enjoyable to handle and use.

In short, perceptions of good selection are linked to a general preference for, and enjoyment of, a given format, but largely disconnected from reading habits and purchasing/borrowing experience. A belief that print has better selection appears to be just that: a belief. And, more importantly, this advantage may be unassailable. If it is not based on evidence in the form of personal experience, but rather on sentiment, there may be no improvement creators or retailers can make to change minds. The impression is entrenched, just as belief in the low quality of self-published novels (which can be in print, but are overwhelmingly released as digital-only) is entrenched: if, as discussed later in this chapter, readers frequently mistake high-quality self-published books for traditionally published books, and only identify as self-published the poorest examples, there is little opportunity to revise judgements.

Self-publishing and the Elusive ‘Book of Quality’

‘The difference between the e-book and print book is that [with a] print book you have packaging, so you already have some kind of preconception of what your experience should be. Sort of…what will be coming, in a way. With an e-book…you just have the cover, and then you go through, it’s sort of difficult to judge whether…it’s actually a book of quality, in a way? I mean, if it’s from one of the Big Five, it’s probably…more reliable in a way.

‘[A recently-read self-published book] had typos, it was clearly badly edited, it just looked like self-published, which was awful.’

Self-publishing continues to contend with ‘this horrible stigma’.62 ‘Vanity publishing’63 may predate digital, but the explosion in self-publishing facilitated by digital delivery has cemented the link between the two in the market and in readers’ minds. Participants acknowledge that quality can be found in self-published books (‘self-published…could be amazing’) and note the proud tradition of independent artists in many fields, comparing self-published fiction to avant-garde zines and punk aesthetics (‘the Sex Pistols were far better when they were putting it out themselves’).64 But many still strongly associate self-publishing with low quality, with ‘amazing’ examples the exception rather than the rule. In interviews and focus groups, participants discussed self-publishing in response to specific questions but also spontaneously, raising it continually as they described their experiences of e-reading. Some are confident in their ability to identify self-published books at a glance (‘you’d know the ones that are [self-published]’), and not simply due to quality issues such as poor copyediting (though ‘thinking, they need to get a better copy editor’65 is a common occurrence in their experiences of self-publishing). They describe a ‘whiff’ of fan fiction or a related ‘whiff’ of vanity publishing.66 Telltale signs, for these participants, include not only typographical errors and other editorial gaffes but also simply ‘something about them’ and the presence of the ‘odd’:67 aspects that are not blatantly incorrect, but are nonetheless out of step with what experienced readers expect (a further indication that readers are not isolated from the logic of the field68 and their personal judgements are informed, though not controlled, by industry norms).

Participants want good books, and describe themselves as open to the idea of good books coming from many sources, not only in print and from mainstream commercial publishing. A number are active, enthusiastic readers of self-published books, particularly fiction. Some report that ‘self published books are often only available as ebooks, so I buy those on ereader’ or that some ‘favourite’ books are books obtained ‘for free on Amazon’.69 A number note fan fiction as particularly important, either as the genre that attracted them to digital reading or a genre they discovered through digital reading.70 Even those who do not (or do not knowingly) read self-published books cite examples of self-published works they consider to be of outstanding quality, including print bestsellers that were initially self-published such as Andy Weir’s The Martian.71 Many stress that they do not dismiss self-published books out of hand (e.g. ‘I’m not generally opposed to [self-published books]’)72 and some condemn such dismissal as snobbery,73 of a kind detrimental to book culture, an outdated and ill-informed prejudice. However, their personal experiences of self-published works are frequently of books where ‘the quality of writing and editing is not as good as traditionally published novels’.74 Even where the ‘ideas were really interesting’ or ‘content was fantastic’, poor editing could render a book unreadable.75 Intriguingly, given the confidence many expressed (as above) that they could identify a self-published work by its general oddness, several described experiences of haphazard professionalism, as with an excellent cover but poor editing, or of being caught out: ‘I didn’t realise [the book] was self-published until I started reading it and I thought, “This cannot possibly have gone through a reputable publisher.”’76 This makes it possible that many have read high-quality self-published books without realising it. Their general impression is that quality can be found in self-published books, but that it is ‘harder to find’, especially when past encounters of ‘really awful’ self-published books have ‘put [them] off…it could be amazing, but it could be really, really dire’.77 ‘Pleasant surprises’78 are, largely, surprises.

These experiences reinforce the negative perception of self-publishing as an author’s ‘last resort’,79 and the common assumption (acknowledged by participants as typical, even if they would not want to make such an assumption themselves) that ‘this has probably been rejected by every publishing house in Britain…That’s why it’s self-published’.80 As noted, the stamp of mainstream publishing signals to these participants’ investment. Gatekeeping is widely considered to guarantee a certain (if not perfect) level of ‘quality control’ and to offer ‘an indication of whether it’s worth reading or not’.81 Without such guarantees, personal recommendations are even more important, whether from friend networks for fan fiction or ‘traditional mediums like newspaper columns and book reviews and things’.82 The industry gatekeeper can be dispensed with, but not simply replaced in a one-to-one swap: some readers stress that for self-published works there is a ‘higher standard of recommendation’, where multiple endorsements are needed to provide the same level of trust: ‘if it’s a self-published book then you have to wait for three or four people to tell you that it’s actually really good’ instead of just one friend.83

This frames traditional publishing as a service to readers, with professional editors paid to ‘jump in and go find things’ because ‘life’s too short’84 for readers to do so on their own time. This vocabulary of service may downplay an editor’s power, but only highlights the overwhelming trust placed in editors: they will supply the best traditionally published material, but they will also find and elevate the best self-published material, as with ‘so, you just think that if it is self-published, if it is good enough to be worth reading, a publisher will pick it up eventually’.85 It leaves an uneasy balance, where the editor is an unquestioned expert, controlling what readers can see, but who is nonetheless effectively subordinate, someone to whom the reader can delegate work.

The enduring trust in professional judgement intersects with the lower perceived value of digital in the category of digital-only works that are not self-published. Digital-only releases by traditional publishers are again rare, with experiments from the 2010s, including Big Five imprints such as Penguin Random House’s Hydra and Alibi and Avon Impulse86 and series from highly respected literary magazines such as Ploughshares Solos,87 largely augmented with print-on-demand options or quietly retired. Despite the fact that a digital-first or digital-only release from any of the above would have received the same editorial attention and is held to the same standard as any print release, digital-only remains, as a category, ‘dubious’.88 There is a suspicion that a book released only in digital form is by definition second-best: ‘why would [the publisher] invest in print for other books but not this one?’89 Explaining why they don’t consider e-books to be real books, one respondent cuttingly laid out the enduring legitimacy gap for anything not released in print form with ‘Obviously books that do not merit print publication…do not merit print publication’.90 As another put it, ‘e-only, in my head, I equate it with, like, films that go straight to DVD’91 – a statement that, coming from a young adult, invoked the obsolete technology of an earlier generation to comment on the credibility of digital books for their own generation.

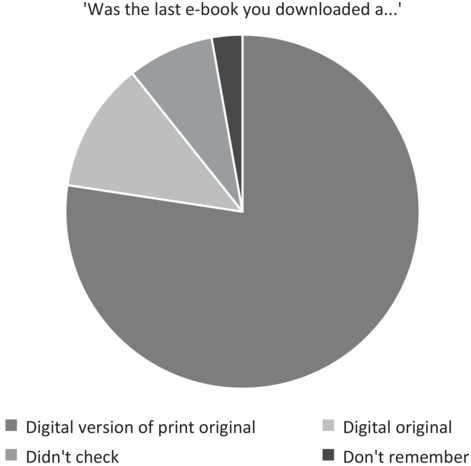

The question is how this perception of digital-only as a cheap option, suitable for second-rate books, plays into readers’ perception of individual books … and if readers know, or care, whether their e-books have print editions. I asked e-book readers about the print status of the last e-book they read. The options were ‘Digital version of a print book (you could have chosen a printed copy)’ and ‘Digital original (there was no printed copy to choose)’, but also ‘Didn’t check’ and ‘Don’t remember’. If print status were irrelevant, one would expect a large number of answers in the latter categories. However, readers are in fact overwhelmingly aware of, and overwhelmingly remember, the print status of their e-books. Of the e-book readers who answered the question, nine out of ten (89.3 per cent) were confident that they had this information (Figure 2.4).

Figure 2.4 Publication status of last e-book downloaded.

Only 7.9 per cent ‘didn’t check’, indicating that readers almost invariably do check at some point in the process of obtaining a digital book. Of those who were confident that they did know, digital original was a rare choice. More than five out of every six (86.6 per cent) reported having read a ‘digital version of a print original’, where they could (at least in theory) have opted for a print copy. These proportions were largely stable over the course of the survey, meaning that the massive increase in digital reading, and turmoil in print book availability, during lockdown had little discernible effect.

This commitment to digital versions of print originals may not, however, be as powerful as it first appears. Readers’ recollection of the print status of last e-book read depends not only on their memory but also on the accuracy of their original assessment of that print status. And as data indicate, sources of such information can be misleading.

Signalling Status: Digital-only, or Also in Print?

Publishers and author/publishers who cannot answer ‘yes’ to the reader question ‘is this book in print?’ face a grave obstacle. They must respond to another question – ‘if it is not in print, why not?’ – and if this second answer is not convincing, the text will not be viewed in the same light. Epitext offers authors a chance to answer with a narrative, telling a story that defines their digital-only or self-published work in terms of its relationship to print and in the context of a larger writing career and authorial identity. Authors may make extensive use of public authorial epitext, in the form of mediated interviews and articles, unmediated social media and personal websites, actively deceptive pseudo-allographic or crypto-authorial ploys, or a coordinated campaign using a variety of such approaches. Their narratives can align them with traditional mainstream publishing as ‘proper’ print authors who happen to be releasing one-offs for artistic reasons: for example, Richard Russo using interviews to defend use of the now-defunct digital publisher Byliner for his novella Nate in Venice as the only way to publish a novella as a standalone work, and hence to realise his vision.92 Their narratives may also align them against traditional mainstream publishing. Such stories can present them as artists resisting a corrupt corporate oligarchy that exploits writers and fails readers, as with Polly Courtney using near-identical wording in interviews, articles, social media bios, and tweets to reinforce the message that she ‘dumped’ her Big Five publishers and now self-publishes for reasons of principle.93 But authors can and do attempt to embed messages of legitimacy in the digital book-object, not via epitextual narrative but via what are in print peritextual elements: front matter, covers, and page design. For the former, this involves the arguably deceptive tactic (though, as noted above, paratext is often deliberately deceptive) of the single-author imprint.

Masquerading as ‘Chosen’

Self-published authors have for decades been advised to evade rather than confront the self-publishing stigma by ‘choos[ing] a publishing imprint name, to make your book sound more as if it has been published by a company rather than an individual’94 – a tactic that predates e-books, and indeed computers. Blogging in 2011, author Lindsay Burokur described her choice not to conceal her status as the publisher of her own work as an iconoclastic and risky one, reporting that ‘someone more experienced (and more successful) than I said that indie authors should create an imprint because (a) reviewers who say they won’t take self-published fiction might consider work from small presses and (b) there are readers who refuse to try independent authors’.95 She concluded, however, that despite the ‘stigma associated with self-published books’ she considered such a ‘disguise’ incompatible with her ‘embrace’ of the independent author mission and identity: ‘I’m all for trying to make the packaging of my books professional, but I don’t think it’s in me to make up a press in an attempt to look like something I’m not’.96 (In other posts, Burokur describes being approached by publishers, including Amazon’s digital-only 47North imprint, but turning these down,97 using authorial epitext to position herself as credentialed by, but in principled opposition to, mainstream publishing in a manner reminiscent of Polly Courtney.)

For a Kindle Direct Publishing author such as Lindsay Burokur, explicit differences between undisguised self-publishing and using a single-author imprint typically appear in only two places. One, falling outside peritext, is a ‘Publisher’ line on an Amazon product page. (This typically sits far below the first and second screen of content and requires scrolling to find: focus groups revealed that even committed e-book readers who regularly purchase from Amazon were sometimes surprised to learn from fellow participants that this section of an Amazon product page existed.) The other is the e-book front matter. Distinguishing between independent, small-press, single-author, and customers of pay-to-publish vanity publishing firms based only on a name is difficult even for industry insiders and experienced researchers, and for members of the public sometimes impossible: in the early 2010s, one data-gathering exercise produced by a self-described coalition of independent authors set itself the task of quantifying royalty income, author by author, in part to question whether self-publishing was truly less lucrative than traditional publishing for a typical author.98 This required definitively categorising books by publication type. The project described a labour-intensive process of researching each imprint individually, hunting online for any clues regarding hundreds of obscure names, and on particularly complex cases giving up.99 Even the layout of the front matter is less important electronically: if the typographical arrangement appeared haphazard, only some participants highlighted this as a sign that ‘not as much care [has] gone into this as perhaps should’.100 Others were ready to attribute mistakes to the e-reading device or app rather than the novel itself: a sharp contrast to their lack of patience with imperfect copyediting, where details on the level of unusual hyphenation were sufficient for participants to conclude that a piece ‘wasn’t done professionally’.101 This willingness to effectively give the novel the benefit of the doubt suggests, for this one aspect, something like a level playing field: an arena where the skill of professional book designers does not confer advantage. But in an e-book, where the reader has little else to go on, front matter does at least promise an answer to pressing questions on relationship to traditional mainstream publishing.

Equivalence as Realness: ‘Same’ as the Benchmark for a Real Book

The enduring importance of relationship to a print edition in determinations of value and credibility is equally visible in determinations of realness. Across all the free-text answers on why e-books are, or aren’t, real books, ‘same’ was one of the most frequently occurring words. ‘Same words’, ‘same content’, ‘same book’, and many variations on ‘it’s the same thing, just in a different format’ featured in arguments for e-book realness, while the aforementioned ‘not the same product’ made a counterargument against. This theme of equivalence is entwined with those of utility (e-books offering the ‘same experience’, which I’ll return to in Chapter 4) and materiality (e-books having the ‘same content’, discussed further in Chapter 5). But same book, same thing, speaks to an argument about the fundamental nature of an e-book – and not to the e-book’s advantage. E-book designers’ emulation of print,102 even at the expense of functionality,103 actively invites the comparison, while at the same time setting up unwinnable direct competition. Backing away from the ‘super-book’ dreams that showcased what digital could do that paper could not,104 visions that made Coover so confident that the print novel would die of neglect,105 creators are left in a contest where the best that can be hoped for is a draw. E-books are left not trying to out-book print books, but out-print print books. The result is lukewarm arguments for realness like ‘same words and story. They are not as pretty to look at but while reading this doesn’t really matter to me’ (where the beauty of print books still makes them superior, but in ways not as important ‘while reading’) and ‘because it’s pretty much the exact same as a physical book except I can read them in the dark! I do prefer a physical book as they don’t run out of battery and feel nicer’ [emphasis mine] (where even the valued affordance of night-time reading is outweighed by battery life and ‘feel’ factors, e-books remaining the less-preferred option). Even among participants who agreed that they considered e-books to be real books, fidelity to a print edition could be set as a condition for realness, as with ‘[e-books are real books] if content is identical to the print version’ – and if the ‘content’ (however defined), is not identical, the e-book is not real. ‘Pretty much the exact same’ is, ultimately, not the exact same – and in that head-to-head, e-books come off worse.

‘Not the Same Product’: the Ersatz Book

Participants in my study describe willingness to consider digital-only books as equal to also-print books, but in practice may not take in evidence that might make them reconsider their perception of e-books as a whole. In terms of trust, this suggests that e-books may be grouped together in a permanently lower category: ultimately and irretrievably lacking. That lack speaks directly to a state of bookness that e-books cannot attain, and links to forms of unrealness distinct from digital proxyhood, event paratext, and performative materiality.

In terms of this form of trust, the e-book most often functions for the readers in this study as an ersatz book. It is a substitute, and potentially a good one. The ersatz at best equals the original: it does not exceed and cannot supplant, and more than likely falls short. But fundamentally it is something different. It is ‘like a book’, nearly a book, potentially valuable and worthwhile, but not fully legitimate: it is ‘just not the real thing’. But while the ersatz book is different from a book, it is also different from a digital proxy. These participants’ experiences of e-book legitimacy, and multiple forms of unrealness, demonstrate two things. One, that unrealness is perfectly acceptable to some readers at some times: e-book readers do not choose digital books because they fall into a camp of believers who consider e-books always real, but because they are willing to read unreal things. And two, that different forms of unrealness can coexist.

Conclusion

Trust in a book takes a long time to build but only a moment to break. On this dimension, legitimacy and realness are deeply enmeshed with reputation, and a novel that is not available in print is, by many respondents, assumed to be of lower quality. Readers demonstrate understandable caution, retaining respect, even reverence, for the traditions of print. They subject e-books and e-novels to stringent investigation before even considering induction into their reading lives, or the designation of ‘book’. That said, caution does not equal conservatism: these readers are in theory highly generous in their willingness to consider e-book bids for inclusion, and to learn new ways of evaluating texts in new formats even as they import old ways from their experiences with print. Readers demand professionalism but are willing to consider the possibility of excellence appearing in e-books with no industry pedigree, even if their own experience of self-published e-books has made them pessimistic. However, receptiveness in theory may not translate into receptiveness in practice, as readers’ means of determining self-publishing status are unreliable. In evaluating individual e-books, readers negotiate with authors and publishers in some new and some familiar ways, continuing to draw on what in print are peritextual elements, particularly cover images and page-level design. This defies simplistic transfers of paratextual theory to e-books: it is not possible to ignore the spatial dimension and declare that peritext no longer exists, but neither is it realistic to assume that all peritextual elements are either visible or influential.

When it comes to first impressions and taking a chance, e-books are effectively unreal. In some ways, they function as ersatz books, perceived as lacking the certifying investment of the publishing industry or the sumptuous range of choice on offer in print (even if those judgements are not based on fact). But in terms of paratext, e-books and e-novels function as digital proxies of stable but incomprehensible ‘disguised zip files’ of data. Both forms of unrealness are at least sometimes acceptable. Readers demonstrate the ability to move between frames of reference regarding e-book realness, and hence between conceptions of the nature of an e-book. And as we examine in Chapter 3, on transactions, this movement can be purposeful, and very much under the reader’s control.