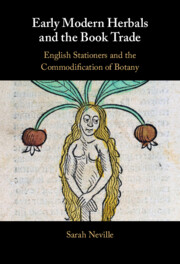

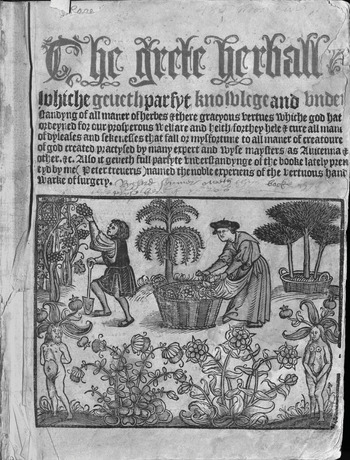

Sometime in spring 1526, Peter Treveris squinted over a page, red pencil in hand. He was correcting pages of his latest publication, an English translation of a French herbal that had been in print on the continent since 1487.Footnote 1 With nearly 500 woodcuts, Treveris’s illustrated folio herbal was an expensive and complicated undertaking, especially for a new printer who’d published only a handful of works before.Footnote 2 The new herbal was designed to supplement another illustrated folio that Treveris had published immediately upon settling in Southwark the prior year, Hieronymus Brunschwig’s Noble Experyence of the Vertuous Handy Warke of Surgeri (STC 13434). This work, too, was a substantive investment for Treveris, and he had gone to some trouble in printing its strikingly illustrated title page in both red and black ink. Treveris intended to use a similarly eye-catching design for the title page of his herbal, and he even planned to reference the surgery book on the title page of this new volume to reinforce how the two books were designed to complement each other (Figure 5.1).Footnote 3 He further planned to add to the title that the remedies in his volume were “practysed by many expert and wyse maysters/ as Auicenna & other. &c.,” an endorsement that suggested there was more to these titles than what was available for sale elsewhere.Footnote 4 As the unillustrated quarto herbal that Richard Bankes had printed the previous year was only a fraction the size of his own, Treveris may have been especially pleased to title his new work The Grete Herball (STC 13176, emphasis added).Footnote 5

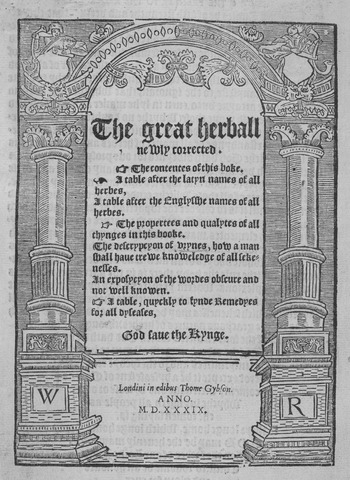

Figure 5.1 The Grete Herball (1526), sig. ✠1r.

Before Treveris could attend to the printing of his herbal’s preliminaries, however, he had to print the remainder of the volume, and something was amiss in his chapter on juniper. As he checked the newly printed pages against his manuscript copy, Treveris noticed that a few clarifying words were missing from the instructions on how to make juniper oil, a remedy for quartan fevers caused by melancholy. With his red pencil, Treveris made a note in the margin. To accommodate the new words, he would need to reorient a few lines and respell some of the surrounding text. No matter: “the” could easily be shortened to “ye” and “with” abbreviated to “wt” to provide the necessary space. Treveris likewise marked for correction a misspelled and incoherent word, “pacyon,” a dittography error likely caused by the compositor’s inadvertently echoing the ending of a word in the chapter’s subheader. In the margins, he noted that the ending needed to be revised so that the word read “pacient.” Most of Treveris’s corrections assured the accuracy of his translation of the verbal text from a manuscript into print, but as a craftsman he was also concerned with the technical errors that marred the aesthetics of his page with unsightly blotches, conspicuous errors that might preclude his being hired by another publisher as a trade printer sometime in the future. At one point, a space had risen to take ink; a few lines later, the kerning of one form of lowercase r in his textura type pushed against a long-st ligature in “first,” creating another blemish. The r would need to be replaced with the other sort of the letter. Treveris marked these errors for correction, too.Footnote 6

We know the specifics of Treveris’s activities as a corrector of his text of The Grete Herball because his proof-sheet for leaves N2–N5 survived in the binding of a 1526 indenture held at Queen’s College, Oxford.Footnote 7 Scrap papers and other forms of printers’ waste were regularly recycled into the paste downs and board bindings in Renaissance books, and as Strickland Gibson observes in his account of the proof-sheets, these “tiny pearls” can provide insight into the mechanics of textual transmission.Footnote 8 In the case of the first edition of The Grete Herball, the proof corrector’s notes testify to Treveris’s careful attention both to his copy-text and to the aesthetics of his printed page, demonstrating his awareness that errors could easily creep into the documents he offered for sale. Both forms of correction were relevant to Treveris’s livelihood: as a bookseller who may have commissioned the translations of the works he published, Treveris had a vested interest in ensuring that his texts were sufficiently accurate and free from nonsensical errors that readers (and fellow booksellers) would value their verbal content enough to purchase them; as a printer whose press and type might be hired by another publisher, he likewise had a vested interest in ensuring that his printed pages were clean and legible. More than four centuries later, Jerome McGann would need to remind scholars that “texts … are embodied phenomena, and the body of the text is not exclusively linguistic,” but for a Renaissance printer-publisher like Treveris, such concerns were perfectly obvious and wholly commonplace.Footnote 9

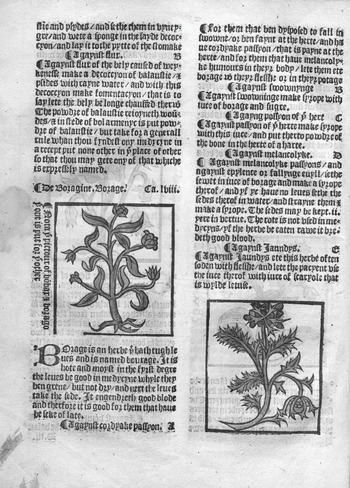

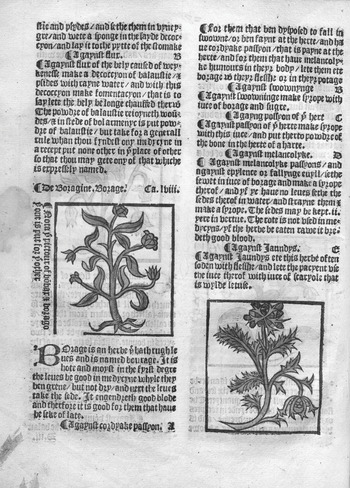

Treveris’s (and McGann’s) attention to the embodiment of texts as material documents results from their awareness that the interaction between verbal and illustrative texts produces meaning. The Grete Herball lacks even the basic descriptions of plant morphology found in the editions of the little Herball, and in many cases, Treveris’s woodcut illustrations, flawed and stylized as they were, provided the only evidence that could enable a user of the text to identify an unfamiliar plant. Along with the volume’s preface, his woodcuts had been copied from those in a continental herbal, the German Herbarius, which purported to be the product of a wealthy traveler to the east who’d commissioned an artist to accompany him on his travels and illustrate plants firsthand.Footnote 10 Recognizing that some of the utility of his product depended on this precise coordination of text and image, Treveris’s press-correcting efforts therefore extended to making sure that his copious woodcuts matched up with the correct chapter. Here, too, there was a problem. Treveris noticed only as he was perfecting sheet D3–4 that the illustration accompanying chapter 58 on borage had been switched with the illustration for an earlier, unnumbered chapter on bombax, or cotton, which he had already printed on the outer side of the same sheet (Figure 5.2). Treveris made the only correction available to him short of scrapping the page entirely and starting over: he inserted a vertical note running alongside the inaccurate cotton illustration that was now heading the borage chapter, noting “Nota [the] pictour of bo[m]bax & borago [the] one is put for [the] other.”Footnote 11 The illustrations were restored to their proper places in Treveris’s second edition of The Grete Herball in 1529, which Treveris printed as a joint investment with his fellow London printer Lawrence Andrewe.Footnote 12 The remaining two sixteenth-century editions of The Grete Herball, by Thomas Gibson in 1539 (STC 13178) and John King in 1561 (STC 13179), were largely unillustrated.Footnote 13

Marginalia

Treveris’s careful attention in ensuring the quality of his printed books was justifiable because errors of textual transmission not only promulgate themselves in future editions; they also lead to readers taking matters of correction into their own hands.Footnote 14 The manuscript annotations early modern readers left in their books testify that they too were aware of the possibility that errors could appear anywhere in their printed books. The popularization of “Faults Escaped” or errata lists in sixteenth-century European books helped readers normalize difficulties in textual transmission when they encountered them, and as William Sherman and Seth Lerer have demonstrated, readers regularly corrected by hand both those errors listed in printers’ errata lists and those they found on their own.Footnote 15 A reader of Thomas Petyt’s 1545 edition of Thomas Moulton’s Mirror, or Glass of Health (STC 18225.4), for instance, confronted in the table of contents with the nonsense chapter heading “yf one womysshe to moche,” correctly surmised that “womysshe” must mean “vomiteth.”Footnote 16 John Locke’s copy of the 1526 edition of The Grete Herball, now held in the Bodleian Library, features manuscript notes detailing an error in that particular copy’s binding, while John Donne’s copy of John Gerard’s 1597 Herball contains a series of corrections to that edition’s errors in page numbering. Other readers corrected a printer’s technical omissions, such as a note furnishing a missing chapter number in Treveris and Andrewe’s 1529 edition of The Grete Herball,Footnote 17 or a dutiful attempt to supply pagination throughout Robert Redman’s 1539 reprint of Bankes’s little Herball.Footnote 18 Yet sometimes readers’ attempts at correction could make matters worse. A reader of Treveris and Andrewe’s 1529 edition realized that two items on sig. O5r were not given chapter numbers and added them, also correcting the numbers in the register of chapters; however, the inattentive reader seems not to have realized that doing so would necessitate advancing all the other chapter numbers in the volume by two.Footnote 19 Nonetheless, readers’ marks such as these testify to moments when readers found fault in their books, and as producers of the printed artifacts in question, booksellers had a vested interest in offering products for sale that were as correct as it was possible to make them.

As Treveris realized, though, just as readers recognizing the vicissitudes of textual transmission could correct printers’ errors in the construction of the book artifact, so too could they correct the content of the verbal and illustrative texts that such books contained. The evidence of contemporary marginalia left in Renaissance books likewise indicates that early modern readers, much like modern scholars, were capable of using books as authorities over knowledge domains only inasmuch as it suited them to do so. Readers who took their pens to printed works could express their disagreement with the verbal text at hand, as did one reader of The Secrets of Alexis (London, 1580) who, upon altering several recipes, wrote “All theas receipts ar verye falsly written, but being corrected heer they ar trew.”Footnote 20 Manuscript evidence contained in several extant printed herbals likewise reveals that, when sixteenth-century readers sought medical advice from their pages, they did so with an evaluative and utilitarian eye, changing the physical artifact of the book to better suit their individual needs as book users and consumers. Wyer’s Macer editions, discussed in the previous chapter, offered readers printed marginal annotations that quickly highlighted key terms to facilitate the scanning of its pages, but the clear margins of the Bankes and Copland editions (and their successors) allowed readers to do such annotating for themselves.Footnote 21 The single surviving copy of Thomas Petyt’s 1541 edition (STC 13175.8) contains manuscript notations from a sixteenth-century reader who found some plant names too Latinate to be helpful, and after reading their vernacular monikers in the text that follows the Latinate heading, they added the English names in the margin. Sig. A3v’s “Absinthium” is thus annotated with “Wormewoode,” and on the following leaf, “Arthemesia” is renamed “mugworte.” A British Library copy of the “W.C. herbal” (published by John Wight in 1552) was read by someone particularly vested in the remedies for flatulence contained in the text, as this document is annotated to highlight those simples that alleviate “wycked wynd.”Footnote 22 A Folger Library copy of Ram’s Litle Dodeon (1606; STC 6988) features heavy annotation in both red and black inks; as Katarzyna Lecky has noted, several of the receipts “are distinguished with sketches of the body part that they treat; others reveal a reader’s reactions to the sugarcoated language referring to women’s health issues.”Footnote 23

Attuned to his customers’ use of books to catalogue and note their own reading experiences, Treveris supplied The Grete Herball with sophisticated finding aids to provide readers with opportunities for using – and marking up – the book in a variety of different ways. Both the 1526 and 1529 editions feature a “registre of the chapytres in latyn and in Englysshe,” which provide each entry in the volume with its own chapter heading and number.Footnote 24 The chapters are alphabetized by the first letter of the entry’s Latinate name, usually immediately followed by the corresponding name for the plant or substance in the English vernacular.Footnote 25 In addition to the initial “registre,” Treveris’s editions of The Grete Herball conclude with “a table very necessary and prouffytable for them that desyre to fynde quyckely a remedy agaynst all maner of dyseases.”Footnote 26 Organized into ailments affecting body parts from the head to the feet, remedies in the table are “marked by [the] letters of the.A.B.C. in euery chaptyre.” Those readers interested in, for example, remedies “Agaynst a balde heed” are instructed to seek out section A in chapter cccclxxxi (481) where they learn that Abrotanum powder muddled with “oyle of Rafanus” and anointed on the head will cause hairs to grow.Footnote 27 Freed from the tyranny of consecutive reading, consumers of The Grete Herball could either use the work as a pharmacological guide, by seeking out individual remedies in the initial register and learning what ailments each could treat, or use the herbal’s concluding table to read the work as a book of cures, organized by complaint.Footnote 28 Later publishers of The Grete Herball like Thomas Gibson would clarify the organization still further by splitting the register to provide separate lists of Latin and English names.Footnote 29 These pharmacologically inflected affordances pioneered by Treveris and Gibson would eventually be adopted and modified by publishers of later “authoritative” herbals like John Gerard’s of 1597, whose considerable size made discontinuous reading preferable. Reading such a massive tome straight through would be nearly impossible.Footnote 30

Most of the British Library copies of The Grete Herball contain annotations that suggest readers engaged with the book for specific purposes. A reader of John King’s 1561 edition was particularly concerned with women’s health, noting that chamomile is useful “for to provoke the flowers,” and inserting a manicule (☞) alongside the same effect of calendula.Footnote 31 On sig. N2r, under “to lose the wombe,” this same tactful reader has noted “to cause the flowers to flowe,” while later they opine that a recipe to “cause you to be laxe and go too the Stole” is “a good purgation.”Footnote 32 A reader of a British Library copy of William Copland’s 1559 little Herball (STC 13175.11) has numbered its pages from one to seventy-eight but there gave up the enterprise. They did not correspond to the numbered pages to the work’s ending table (which offers nothing more than an alphabetical listing of the plants contained), but it is clear that the reader was attempting to organize and annotate their reading. On sig. A5r, the word “wormes” is inserted into the margin at “destroyeth wormes,” while on the facing page they repeat “morphew” and offer three hasty manicules. Worms continue to preoccupy the reader on the following page, while “palsey” and “dropsy” appear to annotate lavender and wormwood respectively.

Because readers of herbals turned to these books as tools that helped them solve problems, these volumes also provided readers with an occasion for recording their own receipts or modifications of verbal details. The same abovementioned British Library copy of Copland’s little Herball is bound with handwritten lists of recipes “For purgation,” written on three pieces of smaller format paper that had presumably been tucked into the volume for safekeeping.Footnote 33 That they are recipes is not in question: “For purgation” is clearly legible, as are the words “take,” “boyle,” “oz,” and “draught.” A handwritten recipe for a distillation contains marigolds and roses and advises that the concoction should only be used in May and June. Such use of herbals as locations for early modern readers to store their own or acquired remedies was widespread, as was the tendency of readers to modify the recipes to suit their own particular religious or geographic affiliations. R. T. Gunther found a copy of Gerard’s 1597 Herbal with notes that indicate the work’s contemporary usage, while a Protestant reader of Treveris and Andrewe’s 1529 edition of The Grete Herball removed the work’s Catholic sentiments.Footnote 34 In a remedy “for the byting of a madde dog,” where the text reads “go to the chyrche and make thy offrynge to our lady and pray her to helpe and hele thee,” the reader has crossed out “our lady” and inserted the word “God.”Footnote 35

This kind of readerly alteration was made possible by a verbal text’s incarnation in a book, whose physical manipulability enabled readers to highlight certain details and ignore others. As Lorraine Daston has observed, “[t]aking notes entails taking note – that is, riveting the attention on this or that particular.” Note-taking, whether it occurs as a result of reading or of observation, “imparts a distinctive economy of attention to practitioners, sharpening their senses and whetting their curiosity for certain domains of phenomena at the expense of others.”Footnote 36 The surviving annotations of Renaissance readers thus indicate that they were not passive agents of the advice that they received from books but rather active mediators who evaluated the diverse claims of written advisors against the body of their own knowledge and experience.Footnote 37 Though some scholars of early printed books conclude that the shift from script to print ultimately resulted in the creation of a passive reader who largely agreed with a text, William Sherman finds that “Renaissance marginalia usually offer clues not just about the context in which books were circulated and read, but about how they were used; indications of the kinds of training that readers brought to bear on their encounters with texts, and the kinds of needs they could be made to serve.”Footnote 38

The Use Value of Herbals

This evidence of reading and note-taking habits contained within extant books is crucial to challenge accounts of herbals that assume contemporary readers simply treated these books as authoritative sources of medical and botanical information in the absence of professional authorities. In so doing, these scholarly accounts support not objective facts about early moderns’ credulity or epistemology but the subjective advertising strategies deployed by publishers as they sought to differentiate their books in the marketplace. For example, H. S. Bennett’s influential work English Books & Readers, 1475 to 1557 identifies herbals as “invaluable first-aid books of reference, and to those far from medical care, often served as the only means whereby a patient’s ailments might be treated. Of course, they were far from scientific in many particulars; but, expressed in simple language, and at times adorned with crude woodcuts of the plants, they met an obvious need.”Footnote 39

Bennett’s interpretation takes The Grete Herball’s own preface as a model in describing the book’s utility for readers. In his preface to the work in 1526 and 1529, Treveris claimed that the herbal provided readers with

fortune as well in vilages where as nother surgeons nor phisicians be dwellyng nygh by many a myle/as it dooth in good townes where they be redy at hande. Wherfore brotherly loue compelleth me to wryte thrugh [the] gyftes of the holy gost shewynge and enformynge how man may be holpen w[ith] grene herbes of the gardyn and wedys of [the] feldys as well as by costly receptes of [the] potycarys prepayred.Footnote 40

Putting his book to press within a year of Bankes’s little Herball being offered for sale (and its being popular enough to quickly merit a second edition), Treveris sought to differentiate his more expensive work from the unillustrated little quarto. To do so, he explicitly presented his herbal as a surrogate for medical care in the absence of knowing professionals, and he likewise positioned himself not merely as a broker in printed commodities but as a thoughtful would-be Englishman engaging in dedicated Catholic service.Footnote 41

In English Books & Readers, Bennett takes Treveris at his word. Yet, as Paul Slack notes, such introductory or title page appeals to “brotherly love” or the good of the “common weale” were routine in the vernacular medical literature of Tudor England.Footnote 42 Though they are compelling evidence for a publisher’s motivations in putting a particular text to print at a particular time, these remarks function more as

pious hopes or calculated advertisements rather than statements of fact. Such works can scarcely have reached the illiterate poor, and the extent of their diffusion even among the literate may well be questioned … they were one small and specialized part of a medical world in which there were several alternative sources of knowledge and advice, from the educated practitioners to the more numerous “cunning” men and women who represented a well-worn and well-known tradition of magical and folk medicine.Footnote 43

Slack concludes that, while works such as The Grete Herball may have offered ancillary help to literate lay readers, they were not primarily viewed as replacements for the myriad forms of professional and “cunning” medicine available for purchase. Yet books such as herbals did serve as a supplement to medicine, a means for readers to learn about some common tricks of the medical trades and how to avoid being taken in. In addition to the remedies for common ailments contained in its entries on aloe, garlic, honey, and other plants and minerals, The Grete Herball details the methods by which unscrupulous medical practitioners could forge expensive medicaments: “And though in this boke we put the craftynesse or deceyt of medycynes / It is not bycause we wolde not that it shoulde be made / but to eschew [the] frawde of them that selleth it / and thus it is made decytful.”Footnote 44

The title pages of herbals indicate that their publishers recognized how these books offered opportunities for readers to exercise their own independent critical judgments, yet, in scholarship, the notion of deferential English readers is nonetheless pervasive. The implicit but usually unacknowledged assumption rests on the notion that the credulous early modern herbal reader accepted anything written down or printed at face value, unquestioningly following the directions depicted in an authoritative book. Readers are often assumed to have attempted anything they encountered in a book’s pages in their desperation to cure. Sometimes scholarly sympathy for the ignorant reader is cited to amplify the misconduct associated with a non-authorial textual agent. For instance, in his extended condemnation of Robert Wyer’s alterations to the little Herball, Francis Johnson bemoans the way that

Wyer makes purely mechanical changes in the wording of sentences that originally were perfectly clear, and thus creates sentences that are either vague or have a different meaning. Note, for example, the condensation of the last part of the section “Anetum.” Bankes’s text was clear, but Wyer, perhaps because his changed order of words led to a mental association of roasting the seed and hotness, directs that the plaster be applied hot to the hemorrhoids. One winces at the agony that many patients must have endured because of this ignorant compiler’s mistake.Footnote 45

Medical doctors and historians evaluating the value of these herbal remedies of printed medical books likewise assume readers’ naïveté when they make a point of emphasizing that seldom did such remedies actually work. In their facsimile edition of the little Herball of 1525, editors Sanford V. Larkey and Thomas Pyles assert that “undoubtedly a number of the prescriptions may have had some efficacy, but in many cases it is difficult to see where they could have been of any value whatsoever. The diseases treated cover a very wide range, and there is little evidence of any rationale.”Footnote 46 Agnes Arber’s approach is similar: in her examination of The Grete Herball, Arber remarks that the work gives “a definite idea of the utilitarian point of view of the herbalist of the period” and that “from the twentieth-century point of view, [it] contains much that is curious, especially in regard to medical matters … the remedies for various ailments strike the modern reader as being violent in a terrifying degree, and adapted to a more robust age than the present.”Footnote 47 Ludmilla Jordanova has identified such presentist accounts as following a “use/abuse model” that “does not challenge historians to unravel the mediating processes involved in the creation of knowledge, leaving the ‘best’ science and medicine as unhistoricized, because true and acceptable, and capable of being used for worthy purposes.”Footnote 48 She advocates instead for the deployment of a social constructivist approach to the history of medicine that can better integrate multiple perspectives and ideologies of healing.

An attention to the materiality of books further aids in the recognition of multiple perspectives. As Jonathan R. Topham observes, the very act of manipulating artifacts enables readers to contest the meaning of verbal texts, which requires rethinking default assumptions about readers’ credulity or innate trust in written objects. “[T]he new history of reading highlights the recalcitrant materiality of the printed works through which readers encounter texts and the hermeneutical significance of that material form,” he writes. “The fact that readers encounter texts in particular material objects – whether books, newspapers, or computer monitors – makes a difference to the meaning they derive from them, because they read more than merely the works.”Footnote 49 Adrian Johns’s work has likewise demonstrated that it took considerable effort for seventeenth-century scientists to make their printed books appear trustworthy, and as we have seen, Renaissance authors themselves were well aware of this phenomenon, using various rhetorical strategies to assert hermeneutic control over their texts.Footnote 50 In Chapter 1, I pointed out how Leonard Fuchs’s praise of Michael Isingrin, the Basel printer and publisher of Fuchs’s De historia stirpium, served to elide Fuchs’s dependency upon Isingrin’s dissemination of printed books as a means of establishing and maintaining Fuchs’s own scholarly authority. Chapter 6 of this study offers an investigation into the way the authority of printed books was broadly understood by early modern Londoners by considering how books were deployed on the popular English stage, while later chapters on William Turner and John Gerard further reveal how these authors’ anxieties over their credibility with readers caused them to attempt to “authorize” themselves through various strategies. The remainder of the present chapter demonstrates that this authorial “authorization” in English herbals, paradoxically, derives from the reprinting of an anonymous work. As The Grete Herball found its way into the hands of Protestant physicians looking to instrumentalize print to suit their professionalizing and evangelical ends, they recognized that books like herbals could reach an audience of self-healers that may have otherwise been resistant to authorized forms of medical care. The books then served as advertisements, not for the services of particular authors or physicians but for the integrity of the emerging practice of professional physic more generally.

Thomas Gibson and the Authoritative Move

I began this chapter with an account of the first illustrated herbal in English, The Grete Herball published by Peter Treveris in 1526, which offered its users innovative affordances like indexes and tables of contents to enable discontinuous reading. Like his contemporary Richard Bankes, Treveris thought of his herbal as part of a sequence of related books about healing, relating it both to his recent handbook on surgery (1525) and later to Lawrence Andrewe’s publication of a book of distillation (1527), which made use of The Grete Herball’s woodcuts. Treveris reprinted The Grete Herball in a joint publication with Andrewe in 1529. My analysis continued by suggesting that the printer Treveris’s concern for the appearance of error in his books indicated his latent anxiety about readers’ expectations for the printed artifacts they purchased and his awareness that readers could do whatever they liked with his books once they took them home from his bookshop. The evidence of annotative reading found in contemporary marginalia indicates that Treveris’s concerns were justified: Renaissance readers were skeptical of the information presented in books, capable of recognizing the limitations of both textual transmission and a verbal text’s authoritative claims. An attentiveness to the materiality of books as repositories for authorized and regularized attitudes towards knowledge establishes a crucial context for what comes next: the third edition of The Grete Herbal published by grocer-printer Thomas Gibson in 1539. This edition included the first appearance in English printed herbals of an authorizing figure who attempts to delimit or mark the interpretive boundaries of his verbal text.

Thomas Gibson, a Morpeth native, made his way to London to apprentice as a grocer in or around 1518. He was made free of his apprenticeship and was a citizen of the City by August 30, 1524, and immediately set up shop as a grocer, successful enough in his trade to bind apprentices in 1526 and 1528.Footnote 51 By 1535, however, Gibson had also begun printing, joining the ranks of several other non-stationers who were engaging in the craft before the Stationers’ Company’s incorporation in 1557 enabled Stationers to have full control over the technology. Gibson’s religious sympathies can be gleaned from his publications: his first known printed book was an edition of Coverdale’s concordance to the Tyndale Bible (STC 3046), and he printed Tyndale’s New Testament (STC 2841) a few years later. Within the next four years, Gibson had printed a total of twelve works, eleven for himself as well as an English primer (STC 15998) that he printed for William Marshall.Footnote 52 In 1537, the bishop of Worcester, Hugh Latimer, wrote to Thomas Cromwell asking that Gibson (who was the messenger of the letter) be entrusted with the printing of The Institution of a Christian Man (STC 5163–7), a privilege that would normally be granted to the King’s Printer Thomas Berthelet (which it ultimately was). Latimer notes in the letter that he himself is only passingly acquainted with Gibson; he remarks that he is vouching for the printer at the behest of one “Doctor Crome,” probably Edward Crome, a clergyman and fellow of Gonville Hall.Footnote 53 Gibson seems to have done his best to ingratiate himself to the king; Blayney records finding among Cromwell’s papers an eleven-page letter of pro–Henry VIII prophecies that Gibson had collected in the hopes of being useful, as well as a proposed bill to “regulate the use of confiscated monastic property.”Footnote 54

Gibson’s petitions for advancement were not particularly successful, and he appears to have left England around 1543 to acquire a medical degree.Footnote 55 John Bale would later record in a notebook kept between 1548 and 1552 (which had once belonged to Gibson) that Gibson was “olim calcographus, nunc medicus” (“formerly a printer, now a physician”).Footnote 56 Such medical sojourns by Englishmen were themselves not unusual; the physician Thomas Linacre took his MD at the University of Padua in 1496 before forming the College of Physicians of London in 1518.Footnote 57 Linacre’s fellow Oxford graduate Edward Wotton and Cambridge’s William Harvey also took their MDs at Padua, later having their credentials incorporated by their home universities. Archivists have found Gibson practicing medicine in Strasbourg in 1555–1558, and upon his return to England he was granted a license to practice medicine by Cambridge University in 1559.

One of the last books that Gibson printed before he left England testifies to his medical interests: a new and unillustrated 1539 edition of The Grete Herball (now spelled The Great Herball). Given The Grete Herball’s investment in enabling patients to forgo the “costly receipts of the pothecaries prepared” in favor of their own knowledge of “green herbs of the garden and weeds of the fields,” Gibson’s choice to republish Treveris’s text is a curious one. Why would a grocer-apothecary undermine his craft by publishing a book that seeks to expose trade secrets? What seems to have happened is that, by 1539, Gibson had already decided to ally himself with a more professionalized medical calling than that of the apothecary-grocers. Hints of Gibson’s philosophy may be seen in the changes that he made to the text of The Grete Herball, which he chose to advertise as “The great herball newly corrected.” In place of Treveris’s xylographic red and black title page with its illustrated gardens, florals, and a pair of coy mandrakes, Gibson’s title page made use of an architectural window-frame border that had previously belonged to printer William Rastell, who had used it to print Fabyan’s Chronicle and Thomas More’s rebuttals to Tyndale (Figure 5.3).Footnote 58 Unable or unwilling to locate botanical woodcuts to illustrate his text, Gibson may have thought it appropriate to suggest instead that his text of The Great Herball could stand alongside such commanding books. He did not use the border in his other publications.Footnote 59

Figure 5.3 The Great Herball (1539).

More telling, however, are Gibson’s editorial changes to the contents of the work that justify his editorial pledge of “newly corrected.” As he reprinted Treveris’s text, the Protestant Gibson stripped The Grete Herball of its inherent Catholicism, removing the advice to pray to “our Lady” from the account of what to do for a bite from a “wood” or mad dog.Footnote 60 In addition to changing the work’s religious bent, though, Gibson’s text also used his printer’s address to the reader to endorse the professionalization of healing as it was practiced by English physicians, shifting the nature of The Grete Herball’s medical authority from the individual self-healer to the dutiful patient who seeks out the resources of informed practitioners. While Treveris’s preface emphasized the potential of the “gyftes of the holy gost” to enable a man to heal all manner of diseases himself, without the recourse of the “costly receipts of the apothecaries,”Footnote 61 apothecary Gibson’s preface, now headed “The Prenter to the Reder,” is careful to note that the authority of the text’s remedies stems primarily from the professional status of its compilers. Though the 1539 Great Herball’s simples are still those “which God hath ordeyned for our prosperous welfare, & helthe,” their virtues are reframed. Gibson’s readers should take note of the remedies in his volume because they “ware practysed by many experte and wyse masters of physyke who also co[m]pyled this most necessary volume, for the comforte of all those, whiche tender theyr owne helth.”Footnote 62 The volume’s “exposycyon of the wordes obscure and not well knowen” appeared at the end of Treveris’s editions of the book, but Gibson finds the glossary (which defined words like “appoplexie,” “conglutinative,” and “sirop”) worth advertising on his title page. Gibson’s highlighting of the list as a selling feature likewise serves to suggest the professional expertise of those who use such a vocabulary. Gibson’s volume teaches, but it also implicitly sends the message that those who would heal themselves must rely on professionals for instruction. Without the intervening expertise of editorially employed masters of physic, “studies” like The Great Herball would be unable to “te[m]per prosperytye … mytygate aduersytye … kepe vnder the hastye and rashe mocions of yeuth, and make yonge persons semblable and equalle to me[n] of great age.”Footnote 63 Education and scholarship are great equalizers, but as Gibson carefully reframes the work, The Great Herball’s contents are particularly valuable because they originate in professional masters who were motivated by a higher power to share their knowledge with the ignorant. Those compilers who “set forth first this herball, which geueth perfyte knowledge and vnderstandynge of all maner of herbes and theyr gracious vertues,” were inspired by God, “as God is the causer of all good studyes … euen in lyke maner as it hath pleased God to styrre and moue those (whyche no doubte of it ware his elect) to set forth first this herbal.”Footnote 64

Gibson claims that printed books of medical remedies authored by learned, Galenic physicians serve the interest of the public, because

sekenesses may be cured & healed by those which knowe the gracyous natures of herbes through the influe[n]ce course of the four eleme[n]tes which God hath set in theyr order, whiche order bryngeth all men to knowledge of all infyrmitees, and to the spedye remedyes therof.Footnote 65

Medical authorities’ education of readers through the distribution of printed books of remedies may be a benefit to the public at large, but as Gibson reframes his argument, it is also one that reaffirms the intellectual superiority of the English medical establishment and its construction of authorized forms of healing. Crucially, there is one exception to the diseases that the listed herbal remedies can cure: “excepte it be a dysease sent of God, as comenly men haue one dysease or other whyche bryngeth all people as the comen saying is, to theyr longe home.”Footnote 66 Gibson’s reworking of The Grete Herball therefore serves to provide his version of the text with a particularly authoritative medical standpoint, repeating the early modern physician’s ultimate excuse that his inability to heal a sick patient results not from his lack of expertise but from the will of God.

Gibson likewise removed from his edition a closing address to readers that had previously appeared in Treveris’s and Andrewe’s editions and that would reappear in John King’s 1561 edition. The address suggests that the volume would benefit both readers and “practicyens,” a Middle French word that originally meant a practicer of a particular, usually medical, art, one who operates on the basis of practical rather than theoretical experience.Footnote 67 In equating readers with practicians, The Grete Herball of 1526 offers equal benefit and opportunity to all, regardless of intellectual or authoritative status:

OYe worthy reders or practicyens to whome this noble volume is prese[n]t I beseche yow take intellygence and beholde ye workes & operacyo[n]s of almyghty god which hath endewed his symple creature mankynde with the graces of ye holy goost to haue parfyte knowlege and vn∣derstandynge of the vertue of all maner of herbes and trees in this booke comprehendyd / and eueryche of them chaptred by hymselfe / & in euery chaptre dyuers clauses wherin is shewed dyuers maner of medycynes in one herbe comprehended whiche ought to be notyfyed and marked for the helth of man in whome is repended ye heuenly gyftes by the eternall kynge / to whom be laude and prayse euerlastynge. AMENFootnote 68

Gibson’s edition of 1539 eliminates this closing note. The herbal for Gibson thus confirms a Tudor Reformer’s moral value of the medical arts, one whose practitioners heal the body just as the minister of the Gospel heals the soul. A decade later, in his Summarium of 1548, John Bale would credit Gibson with authorship of a now-lost treatise on unskilled alchemists, suggesting that Gibson was invested in authorizing discourses even beyond what we see in this small printer’s preface.Footnote 69 Though he was trained as an apothecary and a member of the Grocers’ Company, Gibson had his eye on more professional advancement, and he sought preferment both in direct appeals to the crown and in the books that he offered for sale.

As discussed, Peter Treveris’s reading of the print marketplace led him to experiment with marketing his texts in new ways, like offering his innovative “register” to enable different types of reading acts and by declaring his work of particular use to his English readership in the absence of readily accessible medical professionals. Gibson’s edition is largely structured like Treveris’s, but Gibson improves upon the earlier herbal’s multiple articulation systems to offer distinct alphabetized tables for both Latin and English chapter headings, and he expressly uses the space of his new title page to advertise them. Within the border’s corniced columns, The Great Herball’s title page in 1539 offers a careful list of “The contentes of this boke,” which includes “A table after the latyn names of all herbes, / A table after the Englysshe names of all herbes.” Along with the closing index of diseases he provides, Gibson’s opening tables allow his readers to search for individual medicaments in both languages, expanding upon Treveris’s single table that had been organized solely by simples’ Latin names. These, too, are carefully advertised on The Great Herball’s new title page. As we will see in Chapter 7, Gibson’s approving attitudes towards the professionalization of medicine, as well as the utility of the form of the printed book to further these professionalizing ends, will resurface in the writings of William Turner and color the way that scholars have since read English herbals.

John King Plays the Odds

More than two decades after Gibson’s revised The Great Herball appeared, John King suggested his familiarity with Gibson’s “newly corrected” 1539 edition by advertising on the title page of his 1561 publication of The Grete Herball (as The Greate Herball) that the work was not only “newely corrected” but also “diligently ouersene.” King’s highlighting of correction as a feature of his text demonstrated his familiarity with the advertising language of his competitors in the English book trade: William Powell’s 1550 edition of the “Askham” herbal, discussed in Chapter 4, advertised its text as being “newely amended and corrected,” and it was this text that King saw fit to print for himself at the same time that he printed his edition of The Grete Herball. King’s text, however, was not a reprint of Gibson’s but a copy of Treveris’s text that King saw fit to reprint unillustrated, perhaps because he was unable to locate suitable woodcuts or because he was unwilling to pay to have new ones cut at his own expense. Given the increasing demand for botanical accuracy that stemmed from popular continental publications like Otto Brunfels’s Herbarum vivae eicones (Strasbourg, 1530–1536) and Leonard Fuchs’s De historia stirpium (Basel, 1542), King may have surmised that the old illustrations simply would not serve the turn. There was also a new illustrated herbal complicating matters: the first part of William Turner’s illustrated A New Herball had first been issued from John Gybkyn’s shop in Paul’s Churchyard in 1551, and King may have seen this authoritative book’s impressive and detailed woodcuts in the copies that continued to circulate in London’s bookshops. There was therefore good cause for eliminating illustrations entirely, despite their potential utility for readers.

King had started printing in 1554 and was one of the stationers listed in the Company’s charter of incorporation.Footnote 70 Sometime between November 20, 1560, and March 8, 1561, King sought Stationers’ Company licenses for three books: “the one Called the little herball the ijde the grete herball the iijde the medicine for horses.”Footnote 71 King had been fined 2 shillings 6 pence by the Company in 1558–1559 “that he Ded prynte the nutbrowne mayde without lycense,” so perhaps he, once burned, was particularly shy of being subjected to another Company sanction.Footnote 72 It is also possible that King was, like Peter W. M. Blayney’s hypothetical stationer in “The Publication of Playbooks,” either an “optimist (hoping that his [books] would do well enough to attract thoughts of piracy) or a pessimist (anticipating unspecified problems of infringement).”Footnote 73

The calculated nature of John King’s business strategy is confirmed by his choice in 1561 to pay to acquire the rights to two vernacular English herbals. By doing so, King eliminated both books from the public domain so long as he kept them in print, and he dutifully printed the little ten edition-sheet octavo (STC 13175.19) and the much larger, seventy-five edition-sheet double-column folio (STC 13179) immediately.Footnote 74 King’s decision to market simultaneously two different English herbals testifies to the economic diversity he saw in the marketplace for printed books in the first decades of Elizabeth’s reign. The longer, more expensive herbal could provide for users who were able to afford a more comprehensive text, while the smaller octavo could be bound with other related octavo works that King was issuing around the same time, like his new English translation of the book of secrets of Albertus Magnus (STC 258.5), which had been printed by William de Machlinia nearly eight decades before.Footnote 75 It was a clever scheme: by controlling both forms of herbals, King could ensure that the pair of texts were positioned to compete not with each other but within different markets and with different classes of users in mind.

Throughout this chapter, I have argued that, though historians of herbals have often ascribed credulity to early modern English readers, such accounts strain against the evidence of authors’ paratexual explanations for their texts, the evidence of publishers’ paratextual explanations for their books, and finally, the evidence of the marginalia left behind by contemporary readers. A publisher’s decision to print an anonymous herbal text allowed readers to use their copies of books as locations to record their own local knowledge and experience free from authorial anxieties about intellectual influence. Yet, as Thomas Gibson’s edition of the Great Herball shows, publishers’ use of anonymous texts could also provide an opportunity for would-be medical authorities to step into the breach. When William Turner turned his attentions to the genre at the end of the 1530s, the market was primed to christen a new – and named – figure upon the title pages of printed herbals.