Epistemic Crisis: Did Technology Do It?

The election of Donald Trump and success of the Brexit campaign created a widespread sense among liberal and conservative elites that something had gone profoundly wrong. Both results were a resounding rejection of the combination of cosmopolitanism and globalization, deregulation, privatization, pluralism, and a commitment to market-based solutions to public problems that typified Homo Davosis.

Throughout the first year after the 2016 US presidential election, the leading explanations of epistemic crisis offered by academics, journalists, and governments focused on technology. Some focused on political clickbait entrepreneurs, who had figured out how to get paid through Facebook’s advertising system by using outrage to induce readers to click on “fake news” items. Others focused on technologically induced echo chambers (where endless options for news allow us to self-segregate by our own choices into separate communities of knowledge) or filter bubbles (where companies use algorithms that feed us divergent narratives in order to trigger our persistent interest), suggesting that the epistemic crisis was the result of social media. For a brief period, Cambridge Analytica, a company that claimed to have used psychographic data collected from Facebook to target political ads, claimed credit for both Trump and Brexit. Those claims turned out to have been little more than snake oil. For many who focused on Russia, Russian interference too was anchored in technology – email hacks and networks of bots and sockpuppets manipulating online discourse. Yet others focused on alt-right trolls who thought they had “memed” Trump into the White House from 4chan and Reddit.

In an effort to provide an evidentiary basis upon which to distinguish and measure the relative importance of such sources of epistemic crisis, my team analyzed four million stories relating to the US presidential election, and after the election, to national politics more generally. Our data spans from April 2015, the beginning of the presidential election cycle, through January 2018, the one-year anniversary of the Trump presidency. We reported the results in Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics.1

An Asymmetric Media Ecosystem

Our major finding was that the American political media ecosystem is fundamentally asymmetric. It has a well-defined, relatively insular right wing, anchored by Fox News and Breitbart, but the rest of the media ecosystem is more politically diverse and highly interconnected; ranging from editorially conservative sites like the Wall Street Journal or Forbes to historically left-wing media like Mother Jones or The Nation and newer left-activist sites like the Daily Kos. The widespread assertions about echo chambers or filter bubbles would have predicted a symmetric pattern, given that both right-leaning and left-leaning audiences in America occupy the same technological frontier. The basic sociological and psychological dynamics that predict echo chambers derive from experiments that apply equally across the population. Incentives that drive companies to establish filter bubbles are the same for both groups, and there is no recorded finding that social media companies treat audiences differently. All these elements would predict a clear right, a clear left, and possibly some less well-attended center, only loosely connected to the two more significant symmetrically polarized groups. But that is not what we found.

For the four million stories in our data set, we used network analysis to understand the shape of attention and authority, both on the supply side and the demand side. For the supply side we analyzed networks in which media sources were nodes, with edges defined by links from one media source or another. We observationally assigned the political orientation of the sites into five quintiles: sites whose stories were tweeted or shared on Twitter by a ratio of 4:1 or more by users who had retweeted tweets by Donald Trump, we defined as “right.” Sites whose stories were tweeted by a ratio of 1:4 or more by Clinton supporters, we defined as “left.” Sites whose stories were tweeted by ratios of 3:2 or 2:3 respectively, we called center-right and center-left, and sites that tweeted at a roughly 1:1 ratio we called “center.” This measure, based on observed behavior of 45,000 Twitter users, yielded media oriented scores that were highly correlated with those identified in a study from 2015, which used Facebook users’ self-reported ideology and usage patterns.2

The link networks that we constructed from our data reflect the choices of authors and publishers to link to other sites. They are distinct both from the choices of algorithms that social media companies use, or the choices of readers about the stories they share. Using these measures, it is clear that the right-wing sites are a distinct and insular community that link to each other much more than to media in any other quintile (left, center-left, center, center-right), or that media in any other quintile link to their own quintile. Moreover, attention to right-wing sites increases, both as measured by inlinks and as measured by tweets and Facebook shares, the more exclusively right-wing oriented they are. By contrast, for sites ranging from the center (in which our observational measure includes the Wall Street Journal and Forbes) to the left, there is a single, strongly connected network, with a normal distribution of attention peaking on the traditional professional media that our measure identifies as center-left: the New York Times, CNN, and the Washington Post. There are very few sites that are observationally “center-right”; the most notable include historically right-wing publications such as the National Review, the Weekly Standard, and Reason, who did not endorse Trump. These outlets received little attention over the period we studied.

We also produced Twitter-based networks to describe attention on the demand side. The nodes were the same media outlets, with the same method of political identification, but the edges were based on how often two sources were tweeted on the same day by the same person, with a higher number of co-tweets between any two sites suggesting that the two sites share an audience. Again, we found a highly divided and asymmetric media ecosystem. While the left-oriented sites are moderately less tightly connected to the center and center-left sites when measured by audience attention than when measured by the attention of other media producers, the right-oriented sites are much more clearly separate from the rest of the media ecosystem. Moreover, on the right, the sites that rise to particular prominence using social media metrics, whether Twitter or Facebook, quickly move from partisan media with some of the trappings of professional media, like Fox News, to conspiracy-mongering outrage producers like the Gateway Pundit, Truthfeed, TruePundit, or InfoWars. While we observed some hyperpartisan sites on the left, such as Occupy Democrats during the election or the Palmer Report in 2017, these are fewer and more peripheral to the left-oriented media ecosystem than the hyperpartisan sites oriented toward the right.

Our observations of macro-scale patterns of attention and authority among media producers and media consumers over the three years surrounding the 2016 US presidential election are consistent both with survey data on patterns of news consumption and trust, and with smaller scale experimental and micro-scale observational studies. A Pew survey right after the 2016 election found that Trump voters concentrated their attention on a smaller number of sites, in particular Fox News, which was cited by 40 percent of Trump voters as their primary source of news. The equivalent number of Clinton voters who cited MSNBC as their primary source was only 9 percent.3 More revealing yet is a 2014 Pew survey on news consumption and trust in media across the partisan divide which may help explain the rise of Trump and his successful capture of the Republican Party, despite holding views on trade and immigration so diametrically opposed to the elites of the party of Reagan and Bush, and exhibiting personal behavior that should have been anathema to the party’s Evangelical base. The Pew survey arrayed participants on a five-bucket scale including consistently liberal, liberal, mixed, conservative, and consistently conservative. Respondents who held mixed liberal-conservative views and liberal views differed very little. Those characterized as liberal added PBS to their list of trusted news sources, while sharing the other major television networks that those who held mixed views trusted most – CNN, ABC, NBC, and CBS. Consistently liberal respondents preferentially trusted NPR, PBS, the BBC, and the New York Times over other television networks. A bare majority trusted MSNBC over those who distrusted it. By contrast, conservatives reported that they trusted only Fox News, while consistently conservative respondents added Sean Hannity, Rush Limbaugh, and Glenn Beck to Fox News as their most trusted sources.4 Two distinct populations: one that trusts news it gets from PBS, the BBC, and the New York Times, and the other which locates Hannity, Limbaugh, and Beck in the same place of trust.

It seems clear that the business models and institutional frameworks of these two sets of sources will lead the former to be objectively more trustworthy than the latter, and that a population that puts its trust in the latter rather than the former is liable to be systematically misinformed as to the state of affairs in the world. Consistent with that prediction, studies of the correlation between political knowledge and the tendency to believe conspiracy theories have found that for Democrats, the more knowledgeable respondents are about politics, the less likely they are to accept conspiracy theories or unsubstantiated rumors that harm their ideological opponents. For Republicans, more knowledge results, at best, in no change in the level with which they accept conspiracy theories, and at worst, increases their willingness to accept such theories.5 Again, consistent with what one would predict from patterns of attention and trust we observe and evident from the survey data, more recent detailed micro-observational work on online reading and sharing habits confirms that sharing of fake news is highly concentrated in a tiny portion of the population, and that population is generally more than 65 years old and either conservative or very conservative.6

These findings provide strong reason to doubt the technological explanation of the perceived epistemic crisis of the day. At baseline, technology diffusion in American society is not in itself correlated to party alignment. If technology were a significant driving force we should observe roughly symmetric patterns. If anything, because Republicans do better among older cohorts, and these cohorts tend to use social media less, technologically driven polarization should be asymmetrically worse on the left, rather than on the right. The fact that “fake news” located online is overwhelmingly shared by conservatives older than sixty-five, who also make up the core demographic of Fox News, and that only about 8 percent of voters on both sides of the aisle identified Facebook as their primary source of political news in the 2016 election, support the conclusion that something other than social media, or the Internet, is driving the “post-truth” moment. And the political polarization that undergirds the search for belief-consistent news not only precedes the rise of the Internet, but actually progressed earlier and is more pronounced in populations with the least online exposure since 1996.7

The Propaganda Feedback Loop

Analyzing a series of case studies of the most widely shared false stories, such as the Clinton pedophilia frame that resulted in “Pizzagate”; the Seth Rich conspiracy; or the assertion that Trump had raped a thirteen-year-old; as well as detailed analysis of each of the “winners” of Trump’s “Fake News Awards” for 2017, reveals that the two parts of the American media ecosystem follow fundamentally different dynamics.

The cleanest comparison is between the two stories that emerged in the spring of 2016. The first asserted that Bill Clinton flew many times to “pedophilia island” on Jeffrey Epstein’s plane. The second was that Donald Trump had raped a thirteen-year-old girl at a party thrown by Epstein. The two stories were equally pursued by the most highly tweeted or Facebook-shared extreme clickbait sites who sought to elicit clicks by stoking partisan outrage on both the right and left. The differences between the two parts of the media ecosystem emerge, however, when considering the top of the media food chain. On the left, leading media quickly debunked the anti-Trump story, finding that the lawsuit in which the allegations had been made was backed by an anti-Trump activist, and the story died shortly thereafter. By contrast, the Clinton pedophilia story originated on Fox News online, and was quickly replicated and amplified across the right-wing media ecosystem. It was repeated on Fox television, both on Brett Baier’s “straight” news show and on commentary shows like Hannity. The story became Fox News’ most Facebook-shared story of the entire campaign period, and elaborations of the Clinton pedophilia frame continued to appear on Fox News throughout the campaign, and provided validation to conspiracy theories from a broad range of other outlets. The reporter who “broke” the story on Fox News online, Malia Zimmerman, suffered no repercussions, and indeed was the same reporter who later “broke” the Seth Rich conspiracy story. This story claimed that Rich, a DNC staffer found dead in an apparent robbery murder, had in fact been murdered because he, rather than Russian intelligence operatives, was responsible for the leak of the DNC emails.

We found similar patterns throughout our case studies, on both sides. When mainstream media reported a false story, the errors were found by other media within the mainstream, and public retractions followed in all but one of the cases we studied. Reporters were usually censured or fired when they made false factual assertions. By contrast, in right-wing media reporting, falsehood was never fact-checked within the right-wing media at large (only by external fact-checkers), retractions were rare, and there were no consequences for the reporters.

In effect, we see two fundamentally different competitive dynamics. On the left, outlets compete for attention, often aiming to stoke partisan outrage through framing and story selection, but always constrained both by the fact that audiences pay attention to a broad range of media and by a mainstream professional media delighted to catch each other out in error. As a result, the tendency to feed audiences whatever they want to hear and see is moderated by the risk that an outlet will lose credibility if it is found out in blatant factual error. In addition, reporters suffer professional reputational loss when their stories turn out to have been false.

Things are different on the right. Here, there is no tension between commercial and ideological drivers and professional commitment to factual veracity. We see a propaganda feedback loop with an absence of correction mechanisms which results in the unconstrained propagation of identity-consistent falsehoods. Media outlets police each other for ideological purity, not factual accuracy. Audiences have become used to receiving belief-consistent news, and abandon outlets that insist on facts when these are inconsistent with partisan narratives. The phenomenon is not new, and was lamented as early as 2010 by the libertarian commentator Julian Sanchez, who described it as “epistemic closure” on the right.8

It is nonetheless important not to be Pollyanna-ish about mainstream media. From Stuart Hall’s groundbreaking work in the 1960s and 1970s on the role of mainstream media in constructing race and class; through the 1980s, with Ben Bagdikian’s work on media monopolies, Neil Postman on the inanity of television, and Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky on war propagandism; to the work of Robert McCheseny, Ed Baker, and others in the 1990s on the destructive impact of market incentives on the democratic role of media, a half century of trenchant critique demands that we not idealize mainstream commercial media simply because we encounter even more destructive forces in the right-wing ecosystem. Early enthusiasm for the potential of the Internet to improve our public sphere reflected not only Silicon Valley neoliberalism (although there was plenty of that), but for many, myself included, also reflected a recognition of the limits of mainstream media and observations of successful distributed, non-market media that offered a genuine alternative and more democratic voice within a networked fourth estate. The New York Times’ coverage of WMD (Weapons of Mass Destruction) was only the most prominent beating of war drums that typified American mainstream media in the buildup to the Iraq War, and in the 2016 election our work in Network Propaganda: Manipulation, Disinformation, and Radicalization in American Politics documented how central a role mainstream media played in shaping the public’s perception that Clinton was primarily associated with scandals, not policies. The entire public conversation of police shootings of unarmed black men was transformed by citizens armed with video cameras visually documenting blue on black crimes and distributing them on decentralized networks that forced traditional media to pick them up. There is, moreover, plenty of groupthink and kowtowing to owners and advertisers in mainstream media, and the tension between journalistic ideals and commercial drivers (and the venality of owners) is alive and well. But in our observations of specific factual claims, as opposed to both broad ideological framings, and specific, emotional appeals aimed to stoke outrage, we saw the tension between professional norms and commercial drivers played out as a reality-check dynamic. And that tension moderates the prevalence and survival of audience-pleasing, bias-consistent, outrage-inducing narratives that are factually false. Because of this dynamic, mainstream media, for all its systemic limitations, does not pose the same acute threat to democratic practice as the present right-wing outrage industry.

The Political Economy of Our Asymmetric Media Ecosystem

Partisan media is hardly new in America. Patronage-funded partisan media was the norm for nineteenth century newspapers; professional journalism focused on factual news under norms of neutrality emerged largely only after World War I.9 During the heyday of high modernist professionalism in journalism, from the end of World War II to the 1970s, these norms were most evident in the valorization of fact-based reporting. Media concentration (three broadcast networks as well as a growing number of one-newspaper towns) made reporting from a consensus viewpoint and avoiding offending any part of your audience good business. Even at that time, though, partisan media existed on both the right and the left. On the left, repeated attacks during the first and second Red Scares largely suppressed socialist voices, but outlets rooted in the earlier progressive era, like The Nation or The Progressive, were joined in the 1970s by Mother Jones and later by the American Prospect, as well as Pacifica Radio on the air. These were all relatively small-circulation affairs and were not, in the main, commercially driven.

The same was true on the right until the late 1980s. Beginning with the founding of Human Events in 1944 by the remnants of the America First movement, and followed by the Manion Forum on radio and the National Review in 1955, a network of right-wing outlets cooperated and supported each other throughout the post-war period.10 At no point during this period, however, was this network able to replicate Father Coughlin’s market success in the 1930s, who reached 30 million listeners, and whose shift from support for the New Deal to increasingly virulent anti-Semitic and pro-Fascist propaganda became the basis for one of the classics of propaganda studies.11 Instead, it existed on a combination of relatively low-circulation sales, philanthropic support from wealthy conservatives, and reader and listener contributions.

Like their left-oriented counterparts, these mid-century conservative outlets could not overcome the structural barriers to competing in concentrated media markets. The three networks dominated the news. Radio, under clear ownership limits, had to operate in ways consistent with the fairness doctrine, which made nationwide syndication costly. Local newspaper ownership was fragmented, and local monopolies benefited by serving all readers in their markets. It was simply too hard for either side to capture large market shares.

This had changed dramatically by the end of the 1980s. The most distinctive feature of present-day right-wing media is that it is very big business. Beginning with Rush Limbaugh in 1988, and extending through the launch of Fox News in 1996 to Breitbart in 2007, with non-fiction best sellers from Ann Coulter and others in the present, stoking right-wing anger has become big and lucrative business.12 And it is that fundamental shift from the non- or low-profit model to the profitable business model that has created a dynamic that forces all the participants in the right-wing media ecosystem to compete on the terms set by the outrage industry.

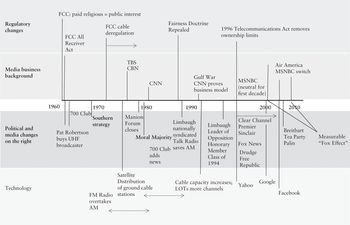

What happened on the right, and why didn’t it happen on the left? Why in 1988? To answer these questions, we have to look at the political economy in the United States, and in particular at the interaction between changes in law and regulation, political culture, technology, and media markets that stretch back as early as 1960. I summarize these factors in figure 1. The short version of the answer is that changes in political culture created a large new market segment for media that emphasized white, Christian identity as a political identity; and that a series of regulatory and technological changes opened up enough new channels that the old strategy of programming for a population-wide median viewer, and hoping for a share of the total audience, was displaced by a strategy that provided one substantial part of the market uniquely-tailored content. And that content was the expression of an outraged backlash against the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, and the New Left’s reorientation of the moral universe inward, to the individual, rather than to the family or God. The left, by contrast, was made up of a coalition of more diverse demographic groups, and never provided a similarly large market to underwrite a commercially successful mirror image.

Figure 1 Feedbacks create supply and demand conditions to make right-oriented outrage-peddling a lucrative business.

The first channel expansion came from UHF television stations in the 1960s. The All Receiver Act in 1961 required television manufacturers to ship televisions that could receive both UHF and VHF stations. Before the Act, because few televisions received UHF, few stations existed, and because few stations existed, few consumers demanded all channel televisions. This regulatory move allowed the technical base for a larger number of channels to emerge. Complementing this move, the FCC (Federal Communications Commission) changed its rules regarding the public interest obligations of broadcasters, and permitted broadcasters to count paid religious broadcasting against their public interest quota. This change permitted Evangelical churches, who were happy to pay for their airtime, to crowd out and displace mainline Protestant churches that had previously been the dominant religious broadcasters and had relied on what the FCC called “sustaining” (free) access to the airwaves. Pat Robertson’s purchase of an unused UHF license in 1961, and his launch of the 700 Club in 1963, epitomize these two pathways for the emergence of televangelism.13 And televangelism, in turn, forged the way for the emerging right-wing media ecosystem.

The second channel expansion happened in the 1970s, through a combination of technological and regulatory changes surrounding cable and satellite transmission of television. In the 1960s through mid-1970s, the FCC had used its regulatory power largely to contain the development of cable. The shift in direction toward deregulation, which swept across trucking, airlines, and banking in the 1970s, reached telecommunications as well (I’ll return to the question of why the 1970s in the last part of the chapter), and the FCC increasingly removed constraints on cable companies and cable-only channels, allowing them to compete more freely with over-the-air television.14 At the same time, development in satellite technology to allow transmission to cable ground stations allowed the emergence of the “superstation,” and Ted Turner’s launch of TBS as the first national cable network. Robertson soon followed with the Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN), and in 1980 Turner launched a revolutionary product: a 24-hour news channel, CNN. Within a dozen years, CNN was to equal and surpass the three networks; 30 percent of survey respondents who got their 1992 presidential election news on television got it from CNN.15

The final piece of the media-ecosystem puzzle came from developments in an old technology – radio. During the 1970s, FM radio, long suppressed through sustained litigation and regulatory lobbying gamesmanship, came into its own, and its superior quality allowed it to capture the music market. AM radio broadcasters needed a new format that would not suffer from the difference, and were ready to adopt talk radio once it was unleashed. And unleashed it was when, after spending his entire tenure pursuing it, Ronald Reagan’s FCC Chair, Mark Fowler, succeeded in repealing the fairness doctrine in 1987. Liberated from the demands of response time, radio stations could now benefit from a new format, pioneered by Rush Limbaugh. In 1988, within months of the repeal of the fairness doctrine, Limbaugh’s three-hour-a-day program became nationally syndicated, using the same satellite technology that enabled distribution to ground stations and made cable networks possible. His style, based on strong emotional appeals, featured continuous criticism of mainstream media, systematic efforts to undermine trust in government whenever it was led by Democrats, and policing of Republican candidates and politicians to make sure they toed the conservative line defined the genre.

For the first time since Father Coughlin in the 1930s, a clear right-leaning, populist and combative voice emerged that was distinct from the ideologically committed but market-constrained efforts of the Manion Forum or the National Review, and became an enormously profitable business. The propaganda feedback loop was set in motion. Within four years Ronald Reagan was calling Limbaugh “the number one voice of conservatism” in America,16 and a year after that, in 1993, the National Review described him as “The Leader of the Opposition.”17 Often credited with playing a central role in ensuring the Republican takeover of the House of Representatives in 1994, Limbaugh was tagged an honorary member of the freshman class of the 104th Congress. By 1996, Pew reported that Limbaugh was one of the major sources of news for voters, and the numbers of respondents who got their news from talk radio and Christian broadcasters reached levels similar to the proportion of voters who would later get their news from Fox News and talk radio in the 2016 election.18 Everything was set for Roger Ailes to move from producing Limbaugh’s television show, to joining forces with Rupert Murdoch and launching Fox News.

Technology and institutions alone cannot explain the market demand for the kind of bile that Limbaugh, Hannity, or Beck sell. For this we must turn to political culture, and the realignment of white, Evangelical Christian voters into a solidly, avidly Republican bloc. The racist white identity element of this new Republican bloc was a direct response to the civil rights revolution. Nixon’s Southern Strategy was designed to leverage the identity anxieties of white southerners, as well as white voters more generally, triggered by the ideas of racial equality and integration in particular. The Christian element reflects the rapid politicization of Evangelicals over the course of the 1970s, in response to the women’s movement, the sexual revolution, and the New Left’s relocation of the center of the moral universe within the individual and the ideal of self-actualization. The founding of the Moral Majority in 1979, the explosive success of televangelism in the 1980s, and Ronald Reagan’s embrace of Evangelicals, all combined to create what would become the most dedicated and mobilized part of the Republican base in the coming decades.

The two elements that defined these audiences, predisposed them to reject the authority of modernity and its core epistemological foundations – science, expertise, professional training, and norms. For Evangelicals, the rejection of reason in favor of faith was central to their very existence. For white southerners, and those who aligned with them in anxiety over integration, the emerging elite narrative after the civil rights revolution treated their anxieties as anathema, and judged their views as shameful, rather than a legitimate subject of debate. Archie Bunker was a laughing stock. This substantial population was shut out and alienated from the most basic axioms of elite-controlled public discourse, be it in mainstream media, academia, or law and policy. And while most successful Republican politicians merely blew their dog whistle, as with Reagan’s “welfare queen” or Bush’s use of Willie Horton; early entrepreneurs like Pat Buchanan were already exploring frankly nativist and racist politics, which, combined with a full-throated rejection of elites, would become the trademark of Donald Trump a quarter century later.

It was a multi-channel market, where three broadcast networks were to compete with three 24-hour news cable channels (MSNBC was launched as a centrist clone of CNN in 1996, only shifting to a strategy of mirroring Fox News for the left in 2006). Having everyone programming for the middle and aiming to get a portion of the audience turned out to be an inferior model to programming uniquely designed to capture one large, alienated audience. Within half a decade of its launch, Fox News had become the most watched network, offering its audience the same mixture of identity confirmation, biased news, and attacks against those who do not conform to the party line, that Limbaugh had pioneered. And, building on the significant relaxation of group ownership rules on broadcasters in 1996 (a product of the political and ideological victory of neoliberalism), Clear Channel Communications purchased over 1,000 radio stations, as well as Premier Radio, producers of Limbaugh, Hannity, and Glenn Beck’s talk radio shows. By 1999, Clear Channel was tapping into a proven right-wing audience, programming coast-to-coast, round-the-clock, outrage-stoking talk radio. Sinclair Broadcasting followed suit with local television stations. By the time Breitbart was launched in 2007, white-identity Christian voters had been forged into a shared political identity for over thirty years, and for twenty of those years had been served media products that reinforced their beliefs, policed ideological deviation in their party, and viciously attacked opponents with little regard for the truth. They were ready for a Vice President Palin. They were ready to believe that a black man called Barack Hussein Obama was a Muslim, an Arab, and in all events constitutionally incapable of being President of the United States. Ready for Donald Trump to phone in to Fox and Friends demanding to see the president’s birth certificate to prove otherwise. And they were only interested in new media outlets that conformed to or extended the kind of news performances they had come to love and depend on over the prior two decades.

The Internet and Social Media

The Drudge Report started about the same time as Yahoo, a year before Fox News. Not long after, the Free Republic forum became the first right-wing online forum. Despite the early emergence of these sites, the first few years of the twenty-first century saw more or less similar growth on the left and right of the new blogosphere, rather than an online reflection of the growing difference on television and radio between the right and the rest. If anything, the near lockstep support in mainstream print media for the Iraq and Afghanistan wars prompted more online activism and criticism on the left than on the right, and the right, in turn, saw a good bit of growth in libertarian blogs. Ron Paul’s supporters in particular flourished on the right; while sites on the left, like the Daily Kos, emphasized mobilization for action, fundraising, and collaborative authorship in multi-participant sites.19

Empirical research about the architecture of the blogosphere at the time showed a symmetrically polarized blogosphere.20 It is possible that these findings reflect the scale of the data or the methods of defining edges. Studies at the time used substantially less data than we now have, observing hundreds of sites over several weeks, rather than tens of thousands of sites over years. It is possible that looking at the blogosphere alone, without including the major media sites such as Fox, reflected the more elite, libertarian-right focus of the blogosphere at the time, which our data suggest were still less enmeshed in the Fox-Limbaugh right in 2016. It is possible that the largely supine coverage by mainstream media of the Iraq war and the “war on terror,” led the left of the blogosphere to separate out and mirror what was already happening on the right, but that the online left became more closely tied into the mainstream as those media outlets soured on President Bush after Katrina, torture, and warrantless wiretapping became widely acknowledged, an alignment that continued with the benign coverage of the Obama White House. And it is possible that the asymmetry between the two poles sharpened dramatically with the rise of the Tea Party, and the shock that white identity voters received from waking up to a black president. We do not have the data to determine whether the original findings of symmetry were incorrect, or whether asymmetry developed online later than it did in radio and television. In any event, our own earliest data: a single month’s worth from October 2012, shows clearly that the asymmetric pattern we observe in 2015 was already present. This asymmetric pattern is also visible in Facebook data from late 2014. The asymmetric pattern in radio and cable news, however, long precedes the significant rise in commercial internet news sites, and it shaped the competitive environment online, making it basically impossible for a new entrant into the competition for right-wing audiences to escape the propaganda feedback loop.

It’s important to clarify here that I am not arguing that the Internet and social media have no distinctive effect on political mobilization by marginalized groups. My focus has been on disinformation and the formation and change of beliefs at the population level, not for individuals and small groups. There is no question that by shifting the power to produce information, knowledge, and culture, the Internet and social media have allowed marginal groups and loosely connected individuals to get together, to share ideas that are very far from the mainstream, and try to shape debates in the general media ecosystem or organize for action in ways that were extremely difficult, if not impossible, even in the multi-channel environment of cable and talk radio. The Movement for Black Lives could not have reshaped public debate over police shootings of black men but for the fully distributed, highly decentralized facilities of mobile phone videos and the sharing capacities of YouTube or Facebook. Twitter and YouTube, 4chan and Gab have provided enormously important pathways for white supremacists to get together, stoke each other’s anger, and trigger murderous attacks across the world. YouTube, in particular, appears to be a cesspool of apolitical misinformation, allowing anti-vaxxers and flat earthers to spread their “teachings.” Any efforts to study social mobilization – whether mobilization one embraces as democratic, or action one reviles as terrorism – or to study misinformation diffusion in narrow, niche populations must focus on these affordances of the Internet and how they shape belief formation. But that is a distinct inquiry from trying to understand belief formation and change at the level of millions, the level that shapes national elections or referenda like Brexit.

Origins: Agency, Structure, and Social Relations; Ideology, Institutions, and Technology

The political economy explanation I offer here seems in tension with accounts in other chapters of this volume. A first dimension of apparent disagreement is an old workhorse: the agency/structure division. How much can be laid at the feet of specific intentional agents as opposed to structural drivers? Several chapters in this collection take a strong agency-oriented stance toward the origins of crisis. Nancy MacLean focuses on the Koch network and its decades-long efforts to create a web of pseudo-academic, political, and media interventions to confuse the voting public in order to enact an agenda that they knew would lose an honestly informed democratic contest. W. Lance Bennett and Steven Livingston take a similar approach, but broaden the lens organizationally toward a broader set of rich, corporate actors funding the emergence of neoliberalism as a coherent intellectual and programmatic alternative. Naomi Oreskes and Eric Conway’s chapter operates within the same frame, but rolls the clock back, focusing on the National Association of Manufacturers and their central role in propagandizing “free market” ideology as part of their efforts to resist the New Deal. The cleanest “structure” version in this volume is Paul Starr’s focus on the Internet and its destructive impact on the funding model that typified the pre-internet communications ecosystem (for all its imperfections). His emphasis is on systematic change in the economics of news production caused by an exogenous global technological shift and not met by an adequate institutional countermovement.

A second dimension of divergence among the accounts focuses on vectors of change – in particular, the extent to which change happens through shifts in the prevailing ideological frame through which societies understand the world they occupy; through formal state-centric politics; through other institutions, most directly law; or through technology. Oreskes and Conway, and Bennet and Livingston both emphasize the cultural or ideological vector (popular in the former, elitist in the latter). MacLean emphasizes ideology and politics. Starr emphasizes the interaction of technology and institutions.

None of us, one assumes, holds a simplistic view that only agency or only structure matters. Our narratives focus on one or another of these, but each of us is holding on to bits of the story. My own approach has long been that both agency and structure matter, and are related by time in punctuated equilibrium – alternating periods of stability when structure dominates, and institutions, technology, and ideology reinforce each other and are resistant to efforts to change social relations, with periods of exogenous shock or internal structural breakdown, during which agency matters a great deal, as parties battle over the institutional ecosystem within which the new settlement will congeal.21 Similar analyses that combine agency and structure over time include earlier work by Starr and Paul Pierson. Starr focused on strategic entrenchment – intentional action aimed at achieving hard-to-change institutions that, in turn, stabilize (just or unjust) social relations.22 Paul Pierson focused on politics in time, incorporating periods of stability intersected by periods of shock or internally accumulated tipping points.23 My interpretation of the diverse narratives in this volume is that we are looking at different time horizons and different actors. It would be irresponsible to assume that sustained strategic efforts, over decades, funded to the tune of hundreds of millions of dollars, by any one or several super-rich individuals and corporations, simply didn’t matter to the rise of neoliberalism and the declining public belief in the possibility of effective government or truth as a basis for public policy. But conservative billionaires and corporate interests have invested in supporting right-wing ideology and politics throughout the twentieth century. As long as their investments were made in the teeth of an entrenched structure where ideology, institutions, and technology reinforced each other within the settlement of high modernism and managerial capitalism, these investments could not batter down the social relations that made up the “Golden Age of Capitalism” or the “Glorious Thirty.”

That “Golden Age,” and high modernism with it, collapsed under the weight of its own limitations. Our experience of epistemic crisis today cannot be separated from the much broader and deeper trends of loss of trust in institutions generally associated with that collapse. When we look at the survey that offers the longest series of comparable responses regarding trust in any institution – trust in the federal government – we see that most of the decline in trust occurred between 1964 and 1980. Pew’s long series shows that this change was not an intergenerational shift. There is no meaningful difference between the sharp drop in trust among the “greatest,” “silent,” and “boomer” generations. And the drop from 77% who trust government in 1964, to 28% in 1980, dwarfs the remaining irregular and gradual drop from 28% in 1980, to 19% in the period from 2014 to 2017.24 Gallup’s long-term data series, starting from 1973, shows an across-the-board decline in which trust in media does not stand out. Only the military and small business fared well over the period from 1973 to the present. Big business and banks; labor unions; public schools and the healthcare system; the presidency and Congress; the criminal justice system; organized religion; all lost trust significantly, and most no less or more than newspapers.25 Moreover, loss of trust in government is widespread in contemporary democracies.26

What happened in the 1960s and 1970s that could have caused this nearly across-the-board decline in trust in institutions? One aspect of the answer is rooted in material origins. The period from World War II to 1973 was a unique large-scale global event typified by high growth rates across the industrialized world due to postwar recovery investment, at a time when war-derived solidarism underwrote political efforts to achieve broad-based economic security and declining inequality, even in the United States. These conditions were supported by an ideological frame, high modernism, which was oriented toward authority and expertise. Leadership by expert elites pervaded political, economic, and cultural dimensions of the period, from Keynesianism, dirigisme, and the rise of the administrative state, through managerial capitalism and the social market economy; to centralized, national or highly concentrated media.

There are diverse arguments about why the Golden Age ended. By one account, strong labor and wage growth combined with the catch-up of both postwar European countries and newly developing countries, and created a profit squeeze for management and shareholders, which drove inflation and led to the collapse of Bretton Woods.27 Other accounts focus on the exogenous shock caused by the oil crisis of 1973 and 1979, and yet others on myopic mistakes by the Federal Reserve in response to these pressures.28 These dramatic, global, economy-wide phenomena followed by the Great Inflation of the 1970s, undermined public confidence in government stewardship of the economy and drove companies into a more oppositional role in the politics of economic regulation. As Kathleen Thelen has shown, the distinctive politics of each of the “three worlds of welfare capitalism” – the Nordic social democracies, mainland European Christian Democratic countries, and Anglo-American liberal democracies – resulted in their adapting to the end of the Golden Age in distinct ways.29 Each of these systems adopted reforms with a family resemblance – deregulation, privatization, and a focus on market-based solutions. But each reflected a different political settlement, with different implications for economic insecurity for those below the top 90th percentile. In the United States in particular, the historical weakness of labor (relative to other advanced democracies); stark racial divisions; and a flourishing consumer movement that set itself up against labor in the battles over deregulation, resulted in the now well-known series of losses for labor, compounded by the Reagan Revolution and normalized by the Clinton New Democrats in the 1990s. These political and institutional changes reshaped bargaining power in the economy, allowing investors, managers, and finance to extract all growth in productivity since the 1970s. Real median income flatlined, and the transformation to a services economy, financialization, and the escape of the 1 percent followed. The result was broad-based economic insecurity coupled with fabulous wealth for the very few. Research in the past few years, across diverse countries following the Great Recession, suggests a strong association between economic insecurity and rising vote share for anti-establishment populists, particularly of the far-right variety. Under conditions of economic threat and uncertainty, people tend to lose trust in elites of all stripes, since they seem to be leading them astray.

The second part of the answer is more directly political. In the 1960s and 1970s, it wasn’t only the right that had had enough of high modernism and its belief in benign elite expertise to govern economy and society. High modernism with its unbounded confidence in scientific management by a white, male elite committed to publicly oriented professionalism, was on the defensive across the developed world. The women’s movement criticized its patriarchy. The civil rights and decolonization movements criticized its racism. The antiwar movement criticized its warmongering and support of a military-industrial complex. The Nader Raiders and the emerging consumers movement did every bit as much to document agency capture and undermine trust in regulatory agencies as did the theoretical work of conservative economists, like future Nobel laureates in economics James Buchanan or George Stigler, who systematized distrust in government as the object of study that defined the emerging field of positive political theory. It was Nader who testified before Ted Kennedy’s Senate committee hearings that led the charge to deregulate the airline and trucking industries, over strong opposition from both unions and incumbents.30 And it was Nader again, shoulder to shoulder with the AARP (The American Association of Retired Persons), who led the charge to deregulate banks in defense of the consumer saver; and again, it was Jimmy Carter’s Democratic Administration that pushed through the transformational deregulation of banking.31 The Carter FCC deregulated cable more than the Nixon and Ford FCCs that preceded it.32 Meanwhile, science and technology studies, from Thomas Kuhn and Bruno Latour on, played a central role in questioning the autonomy and objectivity of science. When business-funded attacks on science came, the elite-educated left had already embraced a profoundly unstable view of the autonomy of science. Similarly, communications studies exposed and criticized the compliance of mainstream media with all these wrongs. Such a comprehensive zeitgeist shift cannot be laid solely at the feet of a handful of identifiable conservative billionaire activists.

On the right, I’ve already noted the backlash of southern white identity voters against the civil rights movement, harnessed and fanned by Nixon’s Southern Strategy, and of Christian fundamentalists against the women’s movement, reinforced by Ronald Reagan’s embrace. These created large basins of loss of trust in political institutions on the other end of the spectrum. The response of business to its losses on consumer, worker, and environmental campaigns in the 1960s, drove a dramatic strategic shift by mainstream business leadership in building lobbying capabilities in Washington DC and the states in the 1970s,33 complementing the more ideologically motivated investments documented by several of the other chapters here.

Throughout this period, mainstream media portrayals of the world in terms congruent with elite views, widely diverged from the perspectives of critics on both sides of the political map. The declining trust in institutions in each of these distinct segments of the population was, in many cases, a reasonable response to institutions whose actual functioning fell far short of their needs or expectations, or had been corrupted or disrupted as a result of the political process. So, too, was their declining trust in media that no longer seemed to make sense of their own conditions.

Taking the material and political dimensions of the answer together begins to point us toward an answer to the question – why are we experiencing an epistemic crisis now, across many democratic or recently democratized countries? The answer is not that all these countries have been hit by a technological shock that undermined our ability to tell truth from fiction. At least in the United States, where we have the best data and clearest measurements, this is not what happened at all. Instead, we need to look for the answer in the deep economic insecurity since the Great Recession and the opening it gave to nationalist politicians to harness anxieties over economic insecurity by transposing them onto anxieties about ethnic, racial, and masculine identity. All elite institutions – not only mainstream media outlets, but academia, science, the professions, and civil servants and expert agencies were to be regarded with fear and anger, which undermined them as trustworthy sources of governance and truth. It is possible that more studies, of more countries, will reveal different dynamics than those we now know have marked American public discourse. It is possible that technological change played a more crucial role in some countries. But barring such evidence, it seems more likely that the shared, global crisis of the neoliberal settlement since the Great Recession is driving what we experience as epistemic crisis, and not the other way around.

Why does it matter whether we focus on structure or on distinct agents? Critically, it affects where we need to focus our political energy. Recognizing that neoliberalism was itself the result of the right and organized business seizing on the crisis of the 1970s to fundamentally redefine the institutional terms of economic production and exchange, demands that the response to the current crisis be focused on building new, inclusive economic institutions that provide coherent, effective answers to the actual state of deep economic insecurity that has left millions susceptible to right-wing, racist-nationalist propaganda. We are now at a moment of instability, where programs we adopt will likely congeal into the institutional elements of the settlement that will surely follow. But the managerialism that preceded neoliberalism during the Golden Age was itself far from perfect, and efforts to build a new, more egalitarian economic system cannot emerge from nostalgia or the simple reconstitution of the progressive institutions that marked modernism and the Golden Age, including hopes for a revival of a traditional, mainstream press.

As the twenty-first century began, the digital revolution seemingly validated two general ideas about the contemporary world. The first was the era’s dominant ideological preference for a reduced role for the state. The Internet of the 1990s and early 2000s appeared to be neoliberalism’s greatest triumph; government regulation was minimal, and digital innovation and entrepreneurship were creating new online markets, new wealth, and new bases of empowerment, connection, and community.

The digital revolution also seemed to validate a second idea: an optimistic narrative about technological progress and its political implications. According to that narrative, the new means of communication expanded access to the news, delivered it faster and more reliably, and afforded broader opportunities for free expression and public discussion. Now, with both personal computers and access to the Internet, individuals would have unlimited information at their fingertips, as well as unprecedented computational and communicative power.1 All this would be good for democracy. Celebrants of the digital era saw the new technology as inherently tending to break down centralized power; the further the Internet spread around the world, the more it would advance freedom and threaten dictatorships.2

These early judgments have now come to seem not just premature but downright naïve. But what exactly went wrong? Here, I want to argue that the early understanding of the implications of digital innovation for the news media and democracy fell prey to three errors. First, the prevailing optimism at the century’s turn highlighted what digital innovation would add to the public sphere, hardly imagining that it would subtract anything of true value. The optimistic narrative undervalued the ways in which the predigital public sphere served democratic interests. It assumed, in particular, that the emerging digital economy left to itself would be no less supportive of a free press than the predigital economy.

Second, the optimistic vision failed to appreciate that the new technology’s affordances are a double-edged sword. As should be all too clear now, online communication is capable of spreading disinformation and hatred just as fast and cheaply as reliable information and civil discourse; indeed, virality favors false and emotional messages.3 The opportunities for greater individual choice in sources of news have been double-edged because, when given the chance, people are inclined to seek sources that confirm their preexisting biases and to self-segregate into groups with similar views, a pattern that much research has shown heightens group polarization.4 The new structure of communication has also created new means of microtargeting disinformation in ways that journalists and others cannot readily monitor, much less try to correct in real time.

Third, like generals still fighting the last war, the digital visionaries who saw the new technology as breaking down established forms of centralized power were blind to the new possibilities for monopoly, surveillance, and control. They mistakenly believed that the particular form the Internet had taken during the 1990s was inherent in the technology and therefore permanent, when it was, in fact, contingent on constitutive choices about the Internet’s development and open to forces that could fundamentally change its character. In a different era, the Internet would have developed differently. But in the United States, which dominated critical decisions about the technology, government regulation and antitrust enforcement as well as public ownership were all in retreat, and these features of neoliberal policy allowed the emergence of platform monopolies whose business models and algorithms helped propagate disinformation.

The digital revolution has made possible valuable new techniques of reporting and analysis, such as video journalism and data journalism, as well as greater engagement of the public in both originating and responding to news. But there is no denying the seriousness of the problems that have emerged. Just as studies of democratization have had to focus on the reverse processes of democratic backsliding and breakdown, so we need to attend to the related processes of backsliding and breakdown in the development of the media.5 I use the term “degradation” to refer to those backsliding processes. In telecommunications engineering, degradation refers to the loss of quality of an electronic signal (as it travels over a distance, for example); by analogy, media degradation is a loss of quality in news and public debate.

To be sure, the meaning of quality is more ambiguous and contestable for news and debate than for an electronic signal. But it ought to be uncontroversial to say that the quality of the news media, from a democratic standpoint, depends on two criteria: the provision of trustworthy information and robust debate about matters of public concern. The first, trustworthy information, depends in turn on the capacities of the media to produce and disseminate news and on the commitment to truth-seeking norms and procedures – that is, both the resources and the will to search out the truth and to separate facts from falsehoods in order to enable the public to hold both government and powerful private institutions to account. The second criterion, robust debate, requires not only individual rights of free speech but also institutions and systems of communications that afford the public access to a variety of perspectives.

Media degradation can take the form of a decline in any of these dimensions. In contemporary America, that decline has taken the form of a degradation in the capacities of professional journalism and a degradation of standards in online media, particularly the insular media ecosystem that has emerged on the far right. Social media, rather than encouraging productive debate, have amplified sensationalism, conspiracy theories, and polarization. In a degraded media environment, many people don’t know what to believe, a condition ripe for political exploitation. In early 2018, Steve Bannon, publisher of Breitbart News and Donald Trump’s former strategist, gave a concise explanation of how to exploit confusion and distrust: the way to deal with the media, he said, is “to flood the zone with shit.”6 That not only sums up the logic of Trump’s use of lies and distraction; it also describes the logic of disinformation efforts aimed at sowing doubts about science and democracy, as in industry-driven controversies over global warming and in Russian uses of social media to influence elections in western Europe as well as the United States. “Flooding” the media with government propaganda to distract from unfavorable information is also one of the primary techniques the Chinese regime currently uses to manage discontent.7

In the past, the mass media were not immune from analogous problems; the “merchants of doubt” in the tobacco and oil and gas industries also deliberately flooded the zone.8 But the new structure of the media has greatly reduced the capacity of professional journalists to act as a countervailing influence and to interdict and correct falsehood. How journalism lost its power and authority, how the new media environment helped undermine standards of truth seeking, and how the great social media platforms came to aid and abet the propagation of hatred and lies – these are all critical parts of the story of the new age of disinformation.

The Attrition of Journalistic Capacities

The optimistic narrative of the digital revolution is a story of disruptive yet ultimately beneficial innovation. As improved ways of producing goods and services replace old ones, new enterprises are born while obsolete methods and legacy organizations die out. This kind of “creative destruction” has certainly happened in many industries, including in some segments of the media such as music and video. But no historical law ensures that every such transformation will be more creative than destructive from the standpoint of liberal democratic values, especially where the market alone cannot be expected to produce a public good at anything like an optimal level.

News about public issues is a public good in two senses. It is a public good in the political sense because it is necessary for democracy to work, and it is a public good in the strict economic meaning of the term because it has two features that distinguish it from private goods: it is non-rival (my “consumption” of news, unlike ice cream, does not prevent you from “consuming” it too), and it is non-excludable (even if provided initially only to those who pay, news usually cannot be kept from spreading). These characteristics enable many people to get news without paying for it and prevent the producers of news from capturing a return from all who receive it. As a result, market forces alone will tend to underproduce it, even in strictly economic terms.

Historically, there have been three general solutions to the problem of news being underproduced in the market. The first solution consists of selective subsidies – that is, subsidies to specific media outlets. Such subsidies have come from governments, political parties, groups in civil society, and powerful patrons typically interested in promoting their own views, and consequently have afforded news organizations little independence. The second type of solution consists of general non-selective media subsidies that are more compatible with editorial autonomy: below-cost postal rates for all newspapers and other publications regardless of viewpoint; tax exemptions applicable to all media outlets; and governmental and philanthropic funds for independent, public-service broadcasting.

In its early history, the United States used both selective subsidies (mainly through government printing contracts for party newspapers) and non-selective subsidies (through the Post Office) to support the development of the press. But since the late nineteenth century, America has had an almost entirely commercial model for the news media in which the financing for high-quality journalism has come via the third method for supporting news that would otherwise be underproduced – cross-subsidies. The various sections of a newspaper, from the classified ads to the sports and business pages and political news, were akin to different lines of business; the profitable lines cross-subsidized the reporting on public issues that might not have been justified from a narrower view of return on investment. During the second half of the twentieth century, the newspaper business was also highly profitable; the consolidation of the industry in metropolitan areas left advertisers with few alternatives to reach potential consumers and gave the surviving papers considerable pricing power in advertising rates. With 80 percent of their revenue typically coming from advertising and only 20 percent from subscriptions and newsstand sales, newspapers could pay for most of the original reporting in a community (radio and television news were distinctly secondary), while generating healthy profit margins.9

By undercutting the position of newspapers and other news media as intermediaries between advertisers and consumers, the Internet has destroyed the cross-subsidy system, along with the whole business model on which American journalism developed. Advertisers no longer need to support news enterprises in order to reach consumers. With the development of Craigslist, eBay, and other sites, the classified ads that had been a cash cow for newspapers disappeared. The Internet also disaggregated the various types of news (sports, business, and so on) that newspaper had assembled, allowing readers to go to specialized news sites instead of buying their local paper. Today most online advertising revenue goes to companies that produce no content at all; in 2017 Facebook and Google alone took 63 percent of digital advertising revenue.10

The capture of digital advertising revenue by the big platform monopolies helps explain why the digital revolution has not led to a growth in online news that could have offset the decline in legacy media. Journalism now depends far more on generating revenue from readers than it did in the past, but many of those readers see no reason to pay, since alternative sources of online news continue to be available for free. At the top of the market, a few national news organizations such as the New York Times and Washington Post have instituted paywalls and appear on their way to a successful digital transition as their aging print readership dwindles; subscriptions can also sustain specialized news sites, particularly for business and finance. But regional and community newspapers have sharply contracted and show no signs of revival. Although digital news sites have developed – some of them on a nonprofit basis – they have not come close to replacing what has been lost in reporting capacities, much less in readership. Despite the scale of decline in local journalism, most Americans seem to be unaware of a problem. According to a survey by the Pew Research Center in 2018, 71 percent think their local news media are doing well financially; only 14 percent, however, have paid for local news in any form.11

The decline in employment in news organizations gives a sense of the scale of lost reporting capacities. According to data from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, total employment in both daily and weekly newspapers declined by 62 percent from 1990 to 2017, from 455,000 to 173,900.12 Those numbers include not only reporters and editors but also salespeople, secretaries, and others. A more narrowly defined measure – reporters and editors at daily newspapers – shows a decline over the same period of 42 percent, from 56,900 to 32,900, according to an annual survey of newsrooms by the American Society of Newspaper Editors.13 Broader measures that include digital news organizations are available only for the more recent period. From 2008 to 2017, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of editors, reporters, photographers, and videographers employed by news organizations of all kinds, fell from about 114,000 to 88,000, a decline of 23 percent. Newspapers, which cut newsrooms by 45 percent over that period, accounted for nearly all the decline.14

The geography of journalism has also changed. While internet-related publishing jobs have grown on the coasts, journalism in the heartland has shrunk. By 2016, 72 percent of journalists worked in counties won by Hillary Clinton, while newspapers underwent the greatest decline in areas won by Trump.15 As a result of the overall contraction and geographical shift, the United States has now been left with an increasing number of “news deserts”, communities without any local newspaper. About 20 percent of newspapers have closed since 2004, while many of the survivors have become ad shoppers with hardly any original news: “newspapers in name only” (NINOs) as one analyst calls them.16 The people who live in the news deserts and communities with NINOs may be especially dependent on the news they receive via social media.

The decline of newspapers has not only brought a falloff in reporting and investigating throughout much of the United States; financially weakened news organizations are also less capable of maintaining their editorial independence and integrity. This is a real cost to freedom of the press, if one thinks of a free press as being capable of standing up against powerful institutions of all kinds. When news organizations teeter on the edge of insolvency, they are more susceptible to threats of litigation that could put them out of business, and more anxious to curry the favor of such advertisers as they still have. The major professional news organizations used to maintain a strict separation between their editorial and business divisions, but new digital start-ups haven’t adopted that rule and older news organizations no longer defend it as a matter of principle. The adoption of “native advertising” – advertising produced by an in-house unit and made to look nearly indistinguishable from editorial content – is one sign of that change.17

For all its faults, the predigital structure of the public sphere enabled news organizations to thrive while producing critical public goods. That structure had a value for democracy that digital enthusiasts failed to grasp. It allowed for considerable institutional autonomy and professionalism and enabled journalists to limit the spread of rumors and lies. But with new technological and institutional developments, those checks on the degradation of standards have collapsed.

The Degradation of Standards

To the celebrants of digital democracy, the downfall of the public sphere’s gatekeepers counted as one of the chief benefits of the Internet. Speech would no longer need the permission of the great media corporations, their owners or publishers, editors or reporters, programming executives or producers. The online world has indeed afforded greater opportunities for the unfiltered expression of individual opinion and the unedited posting of images, videos, and documents. By the same token, however, the gates have swung wide open to rumors, lies, and increasingly sophisticated forms of propaganda, fraud, and deception.

News spreads in two ways, from one to one and from one to many. The new media environment has transformed both sets of processes compared to the predigital era. Online networks allow for more rapid and extensive viral spread from one person to another than the old word-of-mouth did. The new technology has also lowered the barriers to entry for one-to-many communication – “broadcasting” in the general sense of that term.

Broadcasts now include dissemination not only by mass media with high capital costs but also by lower-budget websites, aggregators, and sources on social media with large numbers of followers. Among those sources are individual social media stars (“influencers”), who can broadcast news and opinion, unrestrained by traditional gatekeepers or journalistic norms. For example, the alt-right gamer PewDiePie (Felix Kjellberg) has nearly 96 million subscribers on YouTube. Trump accumulated millions of followers largely on the basis of his virtual-reality TV show before he became a political candidate. The online world is also populated by bots, trolls, and fake-news sites, and it is subject to strategies for gaming searches and other means of both microtargeting messages and shaping what diffuses fastest and furthest.

The one-to-one and one-to-many streams have never been entirely separate; varying combinations of the two always determine the full pattern of communication. In this respect, every media system is a hybrid. In the classic model of the mass media from the 1940s, the sociologist Paul Lazarsfeld posited a “two-step flow” from the mass media to local opinion leaders, and from those opinion leaders to others in their community.18 Lazarsfeld didn’t consider a prior step: how the news reached the mass media. In the new media environment, the flow of communication may have a long series of traceable steps, leading up to and away from broadcasters of all types, with total diffusion depending on the branching structure of cascades. A study of one billion news stories, videos, and other content on Twitter finds a great deal of structural diversity in diffusion, but “popularity is largely driven by the size of the largest broadcast” rather than by viral spread.19 In short, while the spread of disinformation depends on both virality and broadcasting, the preponderant factor is still likely to be the behavior of broadcasters – not just legacy news organizations but also new digital media, individual social media influencers (including political leaders), and other sources with wide reach.

Disinformation flourishes in both the viral and broadcast streams of the new media ecology. Another study of online diffusion using data from Twitter finds that “false stories spread significantly farther, faster and more broadly than did true ones. Falsehoods were 70 percent more likely to be retweeted, even when controlling for the age of the original tweeter’s account, its activity level, the number of its followers and followees, and whether Twitter had verified the account as genuine.” According to this analysis, virality favors falsehood because the false items tend to be more novel and emotional than the true items.20

The new forms of broadcasting have also helped amplify the spread of disinformation. Here it helps to backtrack to the changes in the late twentieth century that led to the emergence – or rather reemergence – of aggressively partisan media outlets.

By the mid-twentieth century, the mass media in the United States no longer had strong connections to political parties, as newspapers had in the nineteenth century before the turn toward advertising as a source of income, and toward professionalism and objectivity as journalistic ideals. American radio and television also developed on a commercial rather than party foundation and, in their news operations, emulated the ideals of print journalism. During television’s early decades, when most areas had only two or three stations, the networks often created a captive audience for the news by scheduling their evening news broadcasts at the same time. In a market with few competitors, the three national television networks – CBS, NBC, and ABC – rationally sought to maximize their advertising income by seeking the widest possible audience, staying close to the political center, and avoiding any partisan identification.

As the number of TV channels increased, however, two things changed. First, people with little interest in politics were free to switch to entertainment shows, while the more politically oriented could watch more news than ever on cable. The news dropouts, according to an estimate by Markus Prior, amounted to about 30 percent of the old TV news audience, while the news addicts represented about 10 percent.21 Other evidence on news consumption in the late twentieth century also suggests rising disparities in exposure to news as older habits of reading the newspaper over breakfast or watching the evening news died out. No longer socialized into those habits by their families, young adults reported lower rates of getting news in any form.22

While viewers with lower political interest dropped out, the audience that remained for news was both more partisan and more polarized. With the increased number of channels, catering to partisans also became a more rational business model for broadcast news, just as it became more profitable on radio and cable TV to specialize in other kinds of niche programming (“narrowcasting”). In 1987 the Federal Communications Commission abandoned the fairness doctrine, which had required broadcasters to offer public affairs programming and a balance of viewpoints. Many radio stations stopped broadcasting even a few minutes of news on the hour, while conservative talk radio led by Rush Limbaugh took off. Ideologically differentiated news channels then developed on cable TV, first with Fox and later with MSNBC. The Internet further strengthened these tendencies toward partisan media since it had no limit on the number of channels, much less any federal regulation requiring balance. These developments created the basis for a new, ideologically structured media environment in which the more politically engaged and more partisan could find news and opinion aligned with their own perspectives, and the less politically engaged could escape exposure to the news entirely.

This new environment, however, has not given rise to the same journalistic practices and patterns of communication on the right and left. The media in the United States now exhibit an asymmetrical structure, as Yochai Benkler, Robert Faris, and Hal Roberts have shown in a study of how news was linked online and shared on social media from 2015 to 2018. On the right, the authors find an insular media ecosystem skewed toward the extreme, where even the leading news organizations (Fox and Breitbart) do not observe norms of truth seeking. But journalistic norms continue to constrain the interconnected network of news organizations that runs from the center-right (e.g., the Wall Street Journal) through the center to the left.23

During the period Benkler and his coauthors studied, falsehoods emerged on both the right and left, but they traveled further on the right because they were amplified by the major broadcasters in the right-wing network. Even after stories were shown to be false, Fox, Breitbart, and other influential right-wing news organizations failed to correct them or to discipline the journalists responsible for spreading them. The much-denounced mainstream media, in contrast, checked one another’s stories, corrected mistakes, and disciplined several journalists responsible for errors. As a result of these differences, the right-wing media ecosystem was fertile ground during the 2016 election for commercial clickbait and both home-grown and Russian disinformation.