As part of broader government transparency initiatives, selected Chinese courts began publishing their decisions on public websites in the early 2000s, but in significant numbers beginning only in 2008 (Reference HeMa, Yu, and He 2016; Reference LiuTang and Liu 2019; Reference ChenYang and Chen 2014). Prior to the SPC’s promulgation on July 1, 2013, of provisional rules requiring all courts to publish most of their decisions on the SPC’s newly launched national website, China Judgements Online (中国裁判文书网, which went live on the same day),Footnote 1 provincial high courts regulated the online posting of decisions on their own websites under the guidance of the SPC (Reference SprickAhl and Sprick 2018; Reference Hou and KeithHou and Keith 2012; Reference Liebman, Margaret Roberts and WangLiebman et al. 2020; Reference HeMa, Yu, and He 2016:200, 203; SPC 2013; Reference WangXu, Huang, and Wang 2014:88). Some provincial high courts maintained their online repositories even after the SPC centralized the dissemination of court decisions on its unified digital platform. The provincial repositories of Henan and Zhejiang are the sources of the court decisions I analyze in this book.

Scholars have raised concerns about the possibility of systematic selection bias in what courts have chosen to post online (Reference Liebman, Margaret Roberts and WangLiebman et al. 2020; Reference HeMa, Yu, and He 2016; Reference HeYang, Tan, and He 2019). I heed their warnings against uncritically treating online court decisions as either true populations or random samples. By carefully benchmarking the characteristics of my Henan and Zhejiang samples, I show they are well suited for studying adjudications in general and divorce adjudications in particular. By all measures, my samples of online divorce adjudications are at worst reasonably representative and at best spectacularly representative.

The sheer volume of China’s online court decisions presents unprecedented research opportunities. Indeed, we can more readily study divorce adjudication outcomes in China than in perhaps any other part of the world, including the United States.Footnote 2 At the same time, however, the methodological challenges posed by such a colossal amount of text are daunting, to say the least. For this reason, few studies have drawn on more than relatively small samples of online court decisions. Until recently, most studies of online court decisions followed the same basic design: after collecting a sample of relevant decisions, often using keyword search terms, and sometimes from one or more courts in a specific city or province, the investigators read each decision and manually coded it according to characteristics of the litigants, legal representatives, case circumstances, outcomes, and so on (Reference Yang and TanChen and Yang 2016; Reference Cheng and GaoCheng and Gao 2019; Reference He and LinHe and Lin 2017; Reference He and YangHe and Su 2013; Reference JiangY. Jiang 2019; Reference LiebmanLiebman 2015; Reference Xia, Zhou, Li and CaiXia, Zhou, et al. 2019; Reference ZhangJ. Zhang 2018). Such a strategy, of course, is constrained by human limits to the number of court decisions that can be manually read and coded. By contrast, this book is the product of a computational (a.k.a. “big data”) approach to automating the process of collecting and coding Chinese court decisions in order to analyze samples far too large to code manually. Some computational studies of court decisions have already appeared (Reference Liebman, Margaret Roberts and WangLiebman et al. 2020; Reference Xia, Cai and ZhongXia, Cai, and Zhong 2019; Reference 525ZuoZhang and Zuo 2020), and many more are on the way.

But this is not a purely quantitative study. By letting us hear the personal voices of divorce litigants, qualitative case examples add a human dimension to the quantitative data. The individual experiences of litigants help us comprehend the tragic human toll of judicial decision-making patterns in the statistical results I report. Qualitative case examples provide a window into the real lives of divorce litigants. Knowing that a case example can represent thousands more like it also helps us grasp the scale of gender injustice in China’s divorce courts.

I chose Henan and Zhejiang for several reasons. First, they are among the earliest and most prolific publishers of court decisions. Second, their provincial high court websites, unlike China Judgements Online, were highly amenable to automated mass downloading of documents, thanks to sequentially numbered URLs. By contrast, not only has China Judgements Online incorporated sophisticated defenses against bulk downloading, but its court decisions are located at seemingly randomly generated alphanumeric URLs. Third, Henan and Zhejiang are large provinces that capture some of China’s regional and socioeconomic diversity. For this reason, they provide analytical leverage in ways precluded by single-province research designs. A finding that observed differences between the two provinces in average caseloads per judge correspond to observed differences between the two provinces in adjudicated denial rates would support my argument that the former causes the latter (Chapter 6). At the same time, a finding that gender differences in divorce litigation outcomes are similar in the two provinces would support my argument about the pervasiveness of patriarchal cultural values and gender stereotypes and biases (Chapters 8, 10, and 11).

In what follows, I will first describe the provincial contexts represented in this study. Next I will provide background on court decisions in general and online collections of court decisions in particular. Then, after describing the characteristics of my two provincial samples, I will detail how I constructed my measures of judicial decision-making. Finally, I will assess the representativeness of the court decisions in my samples and describe my use of qualitative case examples.

Henan and Zhejiang

Reflecting their large sizes and locations in China’s poorer agricultural heartland and more prosperous coastal Yangtze River Delta, respectively, Henan and Zhejiang taken together accounted for 11% of the national population in 2016 and represent a wide geographical and socioeconomic swath of the country. With crude divorce rates slightly below the national average (2.9 in Henan and 2.6 in Zhejiang compared with the national rate of 3.0 per 1,000 population), both provinces in 2016 together accounted for 10% of all divorces and 10% of all divorces granted specifically by court adjudication (Ministry of Civil Affairs of China, various years). In 2016, with a population of 95 million, Henan was the third most populous province behind Guangdong (110 million) and Shandong (99 million). Zhejiang’s population (56 million) ranked it tenth in the country out of all 31 provincial-level units (provinces, autonomous regions, and centrally administered municipalities). In terms of per capita GDP, Henan (ranked 20th) was 25% lower – and Zhejiang (ranked fifth) 50% higher – than China as a whole. Similarly, in terms of urbanization, the share of Henan’s population residing in urban areas (ranked 25th) was 9 percentage points below – and Zhejiang’s (ranked 7th) 9 percentage points above – the national average of 56%. Reflecting the relative importance of agriculture in each province, the primary sector accounted for 11% of Henan’s GDP but only 4% of Zhejiang’s in 2016. Henan is a net sender of internal migrants, whereas Zhejiang is a net receiver of internal migrants (many hailing from Henan; Reference Liu, Liang and MichelsonLiu et al. 2014). In terms of the total value of international trade in 2016, Zhejiang ranked fourth behind Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Shanghai, whereas Henan ranked tenth (with imports and exports valued at only one-fifth of Zhejiang’s). Zhejiang’s rural per capita annual disposable income of ¥22,866 (ranked second) was roughly double Henan’s ¥11,697 (ranked 18th).Footnote 3 Although the court fee for a divorce petition tried according to the simplified civil procedure was not substantial in absolute terms (¥150, or about US$23), it was equivalent to about five days’ worth of rural per capita disposable income in Henan in 2016.

Mirroring Henan and Zhejiang’s contrasting socioeconomic profiles are their contrasting profiles of judges. Although judges are a male-dominated profession in both provinces, women were better represented on the bench in Zhejiang (about one-third) than in Henan (about one-quarter) in 2013 (Henan Provincial Bureau of Statistics, various years; Reference LiuZheng, Ai, and Liu 2017:181). In 2015, Zhejiang was ranked number one among all provinces and centrally administered cities in terms of judges’ average caseload. Zhejiang’s average caseload of 218 closed cases per judge was 2.2 times the national average and perhaps three times heavier than Henan’s (Henan Provincial Bureau of Statistics, various years; Reference LiuLiu 2016; Reference Yu and MengYu and Meng 2016). The foregoing differences will help us make sense of regional variation in China’s judicial clampdown on divorce (Chapter 6). At the same time, we will see uniform patterns of female disadvantage persist across these two otherwise different contexts (Chapters 8, 10, and 11).

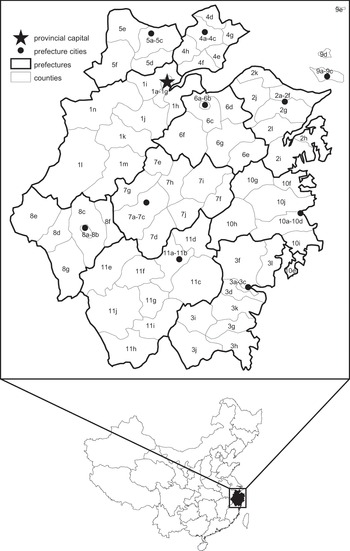

Figures 4.1 and 4.2 depict the locations of all courts in Henan and Zhejiang, respectively. In China, leaving aside courts of special jurisdiction such as railway transportation and maritime courts, each prefecture-level city and provincially administered city has one intermediate court, and each county, county-level city, and urban district has one basic-level court. Henan’s city of Luoyang, for example, has a grand total of nine courts: one intermediate, one for each of its six districts, one for its hi-tech industry development zone, and one railway transportation court. Its intermediate court also has jurisdiction over an additional nine basic-level county and county-level city courts within the prefecture. All of Henan’s 183 courts covering the 2009–2015 time period (including its three special courts) are represented in my sample of online court decisions. In addition to its provincial high court are 19 municipal intermediate courts (including one railway transport court) and 163 basic-level courts (including two railway transport courts). Of all 161 regular basic-level courts, 87 are in counties, 21 are in county-level cities, and 53 are in urban districts (belonging to 17 prefecture-level cities). Likewise, all of Zhejiang’s 105 courts covering the 2009–2016 time period (including its two special courts) are in my sample. In addition to its provincial high court are 11 municipal intermediate courts and 93 basic-level courts (including one railway transportation court and one maritime court). Of all 91 regular basic-level courts, 34 are in counties, 19 are in county-level cities, and 38 are in urban districts (belonging to 11 prefecture-level cities). Court names corresponding to the location codes on the maps are available in the supplementary online material (https://decoupling-book.org/).

Figure 4.1 Locations of courts in Henan province

Note: Codes correspond to courts listed in the supplementary online material available at https://decoupling-book.org/.

Figure 4.2 Locations of courts in Zhejiang province

Note: See note under Figure 4.1.

Among all decisions posted to China Judgements Online prior to 2016, more came from Zhejiang than from any other province. Henan was ranked fourth (Reference HeMa, Yu, and He 2016:208). At that time, both provinces had published fewer decisions on China Judgements Online than on their provincial websites. Henan’s courts, initially slow to post their decisions on China Judgements Online, accelerated and completed the transition away from their provincial website in 2015. As I was finishing this book, Zhejiang still led the country in the number of cases posted to China Judgements Online, and Henan had moved up to third place. The contributions of China’s provinces to China Judgements Online are generally commensurate with the volumes of cases processed by their courts. Henan and Zhejiang have each posted more court decisions than almost any other province because they have processed more cases than almost any other province in China. In 2017, Henan and Zhejiang trailed only Guangdong and Jiangsu in terms of concluded cases. At the same time, Zhejiang’s case volume (and hence its contribution to China Judgements Online) has been disproportionate to its population. Case volumes in Zhejiang, Henan, Guangdong, Jiangsu, and Shandong were all similar even though Zhejiang’s population was about half of the respective populations of Henan, Guangdong, and Shandong and about 70% that of Jiangsu (Reference HeYang, Tan, and He 2019:132). Thanks to the relatively large size and international character of its economy, Zhejiang’s court caseloads have been relatively heavy compared to those of other parts of China (Chapter 5).

Chinese Court Decisions Online

Civil court decisions contain the following basic contents, which generally appear in the following order: court name; decision type; case ID (案号); litigants and their legal representatives, including lawyers (当事人); dispute type; the plaintiff’s legal complaint (诉称), which I usually refer to as either the plaintiff’s statement or petition to the court, and which contains the plaintiff’s claims and requested relief; evidence submitted by the plaintiff, including witness testimony; the defendant’s statement (辩称), which is the defendant’s response to the plaintiff’s legal complaint; evidence submitted by the defendant, including witness testimony; the court’s rulings on admitting or excluding pieces of evidence according to their authenticity and relevance; the court’s holding(s) (理由), which in Chinese literally means “grounds,” and refers to the court’s legal reasoning and analysis behind its ruling(s); the court’s decision(s) or verdict(s) on the matter(s) in dispute (裁判); court fees; the names and titles of decision-makers (the head judge, associate judge[s], assistant judge[s], and lay assessor[s]); the decision date; and the name of the court clerk (书记员). For additional descriptions of the format and contents of court decisions, see Reference Hou and KeithHou and Keith (2012:73–76) and Reference Liebman, Margaret Roberts and WangLiebman et al. (2020:184).

In this book, I generally refer to plaintiffs’ legal complaints as “statements” or “petitions.” They include requests, claims, reasons, and arguments, as well as supporting evidence. Defendants’ statements include responses and supporting evidence. Judges affirm facts presented in litigants’ statements, including marriage dates; names, sexes, and birth dates of children; and individual and marital assets. The plaintiff’s legal complaint, the defendant’s response, and matters of evidence are grouped together in a section called “facts” (事实). “Decision type” refers both to the court division (civil, criminal, administrative, or enforcement) and the type of document (adjudication, procedural ruling or order, mediation agreement, enforcement order, etc.). Litigants were always identified as either plaintiff or defendant and, in second-instance decisions, their original status in the first-instance trial. A litigant’s information also includes, at best, name, sex, date of birth, ethnic group, level of education (only rarely), occupation (also rarely), and residential location (sometimes with a detailed address), and, at worst, only a surname. A surprisingly large number of court decisions even contain unredacted resident identity card (身份证) numbers. Information on representation often includes individual and firm/office names, from which the type of representation can be inferred (firm lawyer, legal aid lawyer, or legal worker). “Citizen representation” (公民代理) by a relative, friend, or colleague, for example, is also permitted but unusual. Sometimes personal information about a representative, such as sex and date of birth, is also included. Dispute type, usually the first sentence of the decision’s main body, includes the nature of the legal complaint (e.g., debt collection, breach of contract, divorce, personal injury compensation). Judges typically explain their reasoning for excluding pieces of evidence. In their holdings, judges, citing relevant provisions in specific bodies of law, also explain the reasoning behind their judgments. On China Judgements Online, a title containing both the dispute type and decision type appears at the top of each court decision (e.g., “First-Instance Civil Adjudication in the Case of Plaintiff Pan Yanle and Defendant Zhang Dashuan’s Divorce Dispute”).Footnote 4

Anyone who analyzes online court decisions must confront two kinds of information availability gaps: document availability in the form of the systematic nonpublication of certain types of court decisions and content availability in the form of the systematic suppression of certain pieces of information within the published decisions. With respect to the problem of document availability, mediations and withdrawals are systematically underrepresented in online collections of court decisions. Generally speaking, cases closed by judicial mediation are designated as mediation decisions (调解书), whereas judicial confirmations of private mediation agreements and case withdrawals are both designated as caiding decisions (裁定书). Caiding decisions are procedural rulings or orders that include approvals of plaintiffs’ requests to withdraw their petitions, confirmations of litigants’ private mediation agreements to render them legally binding, enforcement orders, dismissal orders, and transfer orders. According to the 2009 Measures of the Henan Provincial High Court on Posting Decisions Online, “caiding decisions are in principle not to be posted online” (Article 2). Henan’s 2010 Detailed Rules on Posting Decisions Online were more emphatic by stipulating that “the court decisions of mediated and withdrawn cases are not to be posted online” (Article 5). Likewise, the 2011 Provisional Rules of the Zhejiang Provincial People’s High Court on Posting Decisions Online (hereafter the “2011 Provisional Rules”) prohibited the online publication of cases closed by mediation or withdrawal (Article 4, Item 5 and Item 6, respectively).

In July 2013, when it launched China Judgements Online, the SPC clarified that mediations and withdrawals were generally not to be posted online; that court decisions involving death penalty review cases, state secrets, commercial secrets, and individual privacy were unequivocally not to be posted online; and that courts were to redact individual identifying information from court decisions before posting them online (SPC 2013; Reference WangXu, Huang, and Wang 2014:88). A few months later, when the SPC promulgated its 2013 Provisions of the SPC on People’s Courts’ Posting Decisions Online (hereafter the “2013 Provisions”) for the purpose of unifying the regulation of the online publication of court decisions on its new centralized website, mediation agreements remained excluded (Article 4, Item 3), but caiding decisions were no longer off limits. The 2013 Provisions, which took effect on January 1, 2014, replaced earlier provisions of the same name issued by the SPC in 2010 (Reference TangTang 2018:91; Reference ChenYang and Chen 2014). By stipulating that courts should post decisions on their own websites while the SPC builds a national website, the earlier provisions reflected a decentralized system. After the establishment of China Judgements Online, the 2013 Provisions cemented a centralized, unified national system, stipulated the responsibility of all courts to post their decisions there, and reflected a provision added to the 2012 Civil Procedure Law giving all citizens the right to search for and read nonexcluded court decisions (Reference Liebman, Margaret Roberts and WangLiebman et al. 2020:180; Reference HeYang, Tan, and He 2019:140).

Zhejiang’s 2011 Provisional Rules prohibited the online publication of court decisions on marital and family disputes (Article 4, Item 4). Because the SPC’s 2013 Provisions contained no such restriction, it was removed from tReference Hehe 2014 Detailed Rules of the Zhejiang Provincial People’s High Court on Posting Decisions Online (hereafter the “2014 Detailed Rules”). However, when it amended its 2013 Provisions in 2016 (hereafter the “2016 Provisions”), which took effect on October 1, 2016, the SPC did prohibit the online publication of all divorce decisions.

The extent to which courts complied with public disclosure rules can be seen in Figure 4.3. Let us first consider Henan in Panel A. Among its online court decisions made in 2009, 23% were caiding decisions. After the online publication of caiding decisions was prohibited in October 2009, their representation among all court decisions posted online dropped precipitously and hovered around 10% until the SPC lifted the prohibition in November 2013. At no point did Henan’s courts post more than a handful of court decisions designated as mediations, which are cases concluded by judicial mediation. They did, however, post a few caiding decisions confirming the legal validity of private mediation agreements. The key takeaway from Panel A is that from 2010 to 2013, both caiding decisions and mediations were vastly underrepresented among all court decisions posted online. Whereas mediations and caiding decisions accounted for at least half of all of China’s court decisions, they accounted for only around 10% of Henan’s online court decisions during these four years.Footnote 5 Immediately after the 2013 Provisions were issued in November 2013, Henan’s courts ramped up their online publication of caiding decisions. Caiding decisions as a share of all online court decisions more than doubled between 2013 and 2014, from 14% to 33% and grew to 46% by 2015.

Figure 4.3 Composition of online court decisions

Note: Henan n = 1,014,439 and Zhejiang n = 3,088,636 court decisions. Items in Panel A exceed 100% owing to rounding error. Smoothed with moving averages. The category of “other” types of decisions refers to mediation agreements (调解书), decisions (决定书), and notices (通知书). In Henan, “other” decision types consisted almost entirely of “notices.” In Zhejiang, “other” decision types consisted almost entirely of mediation agreements in 2009 and 2010, but consisted almost entirely of “decisions” and “notices” in 2016 and 2017.

Panel B shows that Zhejiang’s courts were similarly responsive to changing rules from above. Among all of Zhejiang’s online court decisions made in 2009, a little over one-quarter were caiding decisions, and almost one-quarter were mediation agreements. As a consequence of Zhejiang’s 2011 Provisional Rules prohibiting the online publication of mediations and withdrawals, mediations and caiding decisions as a share of all court decisions declined dramatically from 49% in 2009 to 13% in 2011. Then, after the SPC issued its 2013 Provisions, caiding decisions as a share of all court decisions increased to 34% in 2014, 40% in 2015, 47% in 2016, and 45% in 2017. Zhejiang’s courts also complied with the SPC’s rules by not posting mediations. The “other” decisions emerging in 2017 consisted entirely of “decisions” (决定书) and “notices” (通知书). The patterns I have presented so far suggest that online court decisions are well suited neither for the study of mediation conducted by or brought to courts at any point in time nor for the study of withdrawals prior to 2014.

Turning now to the problem of content availability, Henan’s 2009 and 2010 rules required the redaction of identifying information about witnesses and minors, but also required the full disclosure of litigants’ names, sexes, and birthdates. By contrast, Zhejiang’s 2011 Provisional Rules and 2014 Detailed Rules both required the redaction of all litigants’ personal information such as names, sexes, addresses, resident identity card numbers, and bank account numbers. Zhejiang’s rules thus went further than the SPC’s requirement that litigants’ names in only some types of cases, including family disputes, be redacted. Zhejiang’s prohibition of the disclosure of all potentially identifying personal information, including litigant sex, remained in effect – and was generally followed by its courts – following the implementation of the SPC’s 2013 Provisions. The almost complete omission of names and sexes of divorce litigants in Zhejiang’s court decisions is a serious limitation to the study of gender differences in divorce litigation outcomes. Nonetheless, as we will see, enough courts published enough adjudicated divorce decisions containing litigant sex – or information sufficient to infer litigant sex – to support my empirical analyses.

The relatively few published caiding decisions approving plaintiffs’ withdrawal requests contain only information about the litigants, their representatives, and statements such as this: “In the process of trying the plaintiff’s divorce case against the defendant, the plaintiff submitted an application to the court on May 21, 2015, to withdraw the petition. The court approved the plaintiff’s request.” Published caiding decisions on withdrawals contain no information about claims, allegations, reasons, or evidence, and therefore are of limited empirical value. They cannot support a conclusive account of why, for example, women were more likely than men to withdraw their petitions (Chapter 6). Although we can hypothesize that women were disproportionately pressured by judges to do so, we cannot use published court decisions to test either this hypothesis or an alternative hypothesis – and popular narrative – that women’s petitions are more “impulsive” than men’s, that women are more likely than men to use divorce petitions as a tool to scare their husbands into improving their behavior, and that women are therefore less committed than men to follow through with their divorce petitions (Reference 484DiamantDiamant 2000b:338). Similarly, given the scarcity of information in caiding decisions, we have no way to know whether the strongly negative association in the data between the participation of legal professionals and divorce petition withdrawals is a selection effect (plaintiffs who are determined to divorce hire legal professionals) or a treatment effect (legal professionals advise their clients not to withdraw their petitions).

Court decisions are not verbatim transcripts of everything every participant uttered throughout the litigation process. Because they omit ubiquitous informal behind-the-scenes negotiations, often brokered by judges (Chapter 10), court decisions contain significant blind spots that can be remedied only by ethnographic and interview research (Reference HeHe 2021; Reference LiLi 2022).

To sum up, the composition of online court decisions is less reflective of the actual work of courts than of what courts were allowed to post. Collections of online court decisions include virtually no mediations and, prior to 2014, underrepresent withdrawals and other caiding decisions. As we will continue to see in this chapter, however, adjudications, the focus of this book, are generally well represented in online repositories of court decisions.

Sample Characteristics

The court decisions I analyze in this book were downloaded in bulk from the websites of the provincial high courts of Henan and Zhejiang: http://oldws.hncourt.gov.cn/ and www.zjsfgkw.cn/Document/JudgmentBook/, respectively.Footnote 6 Henan’s decision dates range from February 26, 2000, to December 28, 2015, and Zhejiang’s decision dates range from January 6, 2001, to December 31, 2017. In both provinces, the vast majority of decisions were made after 2008. For this reason, and because courts were required to stop posting divorce decisions online when the SPC’s amended rules took effect on October 1, 2016, I limit all analyses of Henan’s decisions to 2009–2015 and of Zhejiang’s decisions to 2009–2016.

Decisions made after 2008 in my Henan sample total 1,014,439, of which 675,956 are civil decisions (67%) and 72,102 are adjudicated approvals and denials of first-instance divorce petitions.Footnote 7 Decisions made after 2008 in my Zhejiang sample total 3,088,636, of which 1,794,217 are civil decisions (72%) and 72,048 are adjudicated approvals and denials of first-instance divorce petitions. I flagged divorce cases by searching for the word “divorce” (离婚) in the titles or opening descriptions of decisions designated as adjudications (判决书).Footnote 8 I excluded post-divorce motions (离婚后). I removed duplicate cases from the Zhejiang sample of divorce decisions. There were no apparent duplicates in the Henan sample.

Panel A of Figure 4.4 shows the temporal distribution of adjudicated divorce decisions in the Henan and Zhejiang samples. Some of its peaks and valleys reflect compliance with rules about posting divorce decisions. Zhejiang’s gaps in court decisions made in the second half of 2011 and most of 2012 may reflect its courts’ compliance with the rule discussed above in the 2011 Provisional Rules prohibiting the publication of marriage and family cases.Footnote 9 In the second half of 2013, the launch of China Judgements Online and the 2013 Provisions led to an immediate boost in the volume of posted decisions in both provinces.

Figure 4.4 Decision dates and filing dates of online divorce adjudications

Note: Panel A depicts first-instance divorce petitions by the dates courts granted or denied them (Henan n = 72,102 and Zhejiang n = 72,048). Panel B depicts first-instance divorce petitions by the dates they were filed in court (Henan n = 42,764 and Zhejiang n = 68,866). Panel B contains fewer cases than Panel A because dates of petition filings are often missing. Labeled dates with arrows in Panel B refer to Spring Festival (Chinese lunar New Year) statutory holidays.

Panel A also shows that courts faithfully heeded the SPC’s call in its amended 2016 Provisions to stop posting divorce decisions effective October 1 of the same year. The precipitous drop in Henan’s volume of online divorce decisions at the end of 2015 is simply a function of the end of its high court’s practice of uploading court decisions to its own website and the beginning of its exclusive use of China Judgements Online.Footnote 10 Zhejiang’s high court, by contrast, continued to upload court decisions to its own website before going offline in 2019. Although my Zhejiang collection contains over 600,000 decisions of all types made in 2017, it contains only 19 decisions on divorce petitions made in the same year. China Judgements Online shows that Zhejiang’s courts were more compliant than courts in most provinces. Nationwide, first-instance divorce adjudications published online dropped from 290,651 in 2015 and 253,371 in 2016 to 45,563 in 2017, and even further to 28,588 in 2018.Footnote 11 Although the SPC has prohibited courts from posting new divorce decisions since October 2016, some courts have continued to do so, albeit in much smaller numbers. Moreover, at the time I was finishing this book, divorce decisions did not appear to have been removed from China Judgements Online.

Annual dips in the production of decisions visible in Panel A correspond to annual surges in filings visible in Panel B. The ebbs and flows of divorce decision-making and divorce case filings are inversely related. The months in which courts decide the fewest divorce cases are January and February (Panel A) owing to the Spring Festival (Chinese lunar New Year) statutory holiday. By far the largest annual spikes in divorce filings occur during the month immediately following the Spring Festival break, the dates of which are indicated in Panel B. Divorce decision-making lulls during the holiday are immediately followed by divorce filing spikes. The annual Spring Festival travel rush (春运) has become an annual divorce rush for migrant workers (Reference LiLi 2015a:106). These annual divorce rushes are far less pronounced when Panel B is limited to urban courts, suggesting that they are driven by migrant workers. The limited ability of many migrant divorce-seekers to return home prolongs the divorce process (Chapter 9). Smaller spikes in July 2013 and 2014 follow the Dragon Boat Festival, another statutory holiday.

Table 4.1 summarizes key characteristics of my samples of divorce decisions, including the size and character of the jurisdictions of the basic-level courts that made them. It brings into high relief differences between Henan and Zhejiang. Henan is a more rural province than Zhejiang. Because the populations of county and county-level cities are predominantly rural, I refer to basic-level county and county-level city courts as “rural.” Because the populations of urban districts are predominantly urban, I refer to basic-level urban district courts as “urban.” In most respects, county-level cities resemble counties more than urban districts. Table 4.1 shows that, defined this way, rural courts handled 82–87% and 65–67% of all divorce cases I analyze from my Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively. Most people and most adjudicated divorces are from rural areas. The rural character of divorce litigation also emerges from national judicial statistics. They show that family cases (divorce, inheritance, and other marriage and family) are overrepresented in People’s Tribunals, which we know from Chapter 1 are predominantly rural. In the ten-year period spanning 2007 and 2016, 30–33% of all first-instance cases and 49–54% of all first-instance family cases were handled by People’s Tribunals (SPC 2018).

Table 4.1 Distributions of cases, courts, and populations

| Rural courts | Urban courts | All courts | Population / basic-level courts / cases | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Henan | ||||

| Population, 2014 | 76% | 24% | 100% | 95,036,900 |

| Basic-level courts | 67% | 33% | 100% | 161 |

| Population % urban, 2014 | 37% | 73% | 45% | |

| Per capita GDP, 2014 | ¥34,505 | ¥44,098 | ¥36,803 | |

| Average annual caseload per judge | 60 | 73 | 65 | 26 basic-level courts |

| First-attempt divorce petitions | ||||

| Full sample | 82% | 18% | 100% | 57,502 |

| With litigant sex | 84% | 16% | 100% | 54,200 |

| Child custody decisions | ||||

| Full sample | 86% | 14% | 100% | 19,201 |

| With litigant sex | 87% | 13% | 100% | 18,216 |

| Zhejiang | ||||

| Population, 2014 | 62% | 38% | 100% | 48,591,771 |

| Basic-level courts | 58% | 42% | 100% | 91 |

| Population % urban, 2014 | 21% | 51% | 33% | |

| Per capita GDP, 2014 | ¥60,432 | ¥157,606 | ¥97,071 | |

| Average annual caseload per judge | 181 | 224 | 200 | 70 basic-level courts |

| First-attempt divorce petitions | ||||

| Full sample | 65% | 35% | 100% | 51,573 |

| With litigant sex | 67% | 33% | 100% | 8,626 |

| Child custody decisions | ||||

| Full sample | 66% | 34% | 100% | 13,832 |

| With litigant sex | 67% | 33% | 100% | 2,529 |

Note: Whereas Henan’s population figures include all residents, Zhejiang’s population figures are limited to people registered by public security organs. In Henan, “% urban” refers to the proportion of the population residing in cities and towns (城镇人口). In Zhejiang, “% urban” refers to the proportion of the population registered as nonagricultural (非农业人口). As described in this chapter, “average annual caseload per judge” refers generally to the mid-2010s and is presented in this table as averages of court-level averages. In 2014, US$1 was worth a little over RMB¥6. Zhejiang’s population of 48.6 million refers to the officially registered population, and is therefore less than its 55.1 million residents in 2014.

According to “population % urban” figures in Table 4.1, Henan appears to be more urbanized than Zhejiang. As I will elaborate later in this chapter, this is a misleading artifact of differences between the two provinces in how urbanization is measured. Although this measure of urbanization is constructed differently in the two provinces, and therefore cannot be used for inter-provincial comparisons, it can be used for intra-provincial comparisons to validate my definition of “rural” and “urban” courts. In both provinces, courts I defined as “urban” were about twice as urbanized as courts I defined as “rural.”

According to the share of the population residing in urban districts, Zhejiang (38%) was far more urbanized than Henan (24%) in 2014. Not surprisingly, per capita GDP levels were far higher in Zhejiang than in Henan and far higher in urban districts than in counties and county-level cities in both provinces. The distribution of basic-level courts generally mirrors the distribution of the population. In Henan, court concentration is greater than population concentration in urban areas because, on average, urban districts have smaller populations than counties and county-level cities.

Although Henan’s population was about double Zhejiang’s, its aggregate GDP was only about three-quarters that of Zhejiang in 2014. For this reason, differences were even greater between the two provinces in terms of per capita GDP. As we will see in greater detail in Chapters 5 and 6, Zhejiang’s higher level of economic development translated into heavier caseloads for its judges.

Of all 72,102 first-instance adjudicated divorce decisions in the Henan sample, 57,502 appear to be judgments of first-attempt petitions and the remaining 14,600 appear to be judgments of subsequent divorce petitions following prior adjudicated denials or withdrawals. Similarly, of all 72,048 first-instance adjudicated divorce decisions in the Zhejiang sample, 51,573 appear to be judgments of first-attempt petitions and the remaining 20,475 appear to be judgments of subsequent divorce petitions filed after failed or aborted prior attempts. Removing decisions with missing data – most notably missing values of litigant sex – reduces the analytical samples of first-attempt adjudications to 54,200 in Henan and 8,626 in Zhejiang. My analyses of child custody determinations include granted divorce petitions regardless of how many attempts were necessary. In other words, whereas analyses of the decision to grant or deny a divorce petition are limited to adjudicated judgments of first-attempt divorce petitions, analyses of the decision to grant child custody to a plaintiff or a defendant (or both) encompass all granted first-instance divorce petitions that include child custody determinations. Hereafter, I refer to the sample of first-attempt divorce adjudications as the “main sample.”

Table 4.2 affirms that online collections of court decisions are well suited for the study of adjudicated divorce outcomes. Looking at all years covered by the samples, online first-instance divorce adjudications account for 58% and 45% of the true population of first-instance divorce adjudications in Henan and Zhejiang, respectively.Footnote 12 Excluding years when courts uploaded relatively few decisions, online divorce adjudications as a proportion of all divorce adjudications are 69% in Henan (2012–2014) and 70% in Zhejiang (2010, 2014–2016). By any sampling standard these are remarkably high rates of representation if we have no reason to suspect systematic variation between published and unpublished cases. In these years, disclosure rates of divorce adjudications in Henan and Zhejiang were higher than those in most provinces. A comparison of officially reported numbers of divorce adjudications and divorce adjudications posted on China Judgements Online shows overall disclosure rates of 61% in 2014 and 59% in 2015. In each year, about one-third of all provinces disclosed fewer than 40% of their divorce adjudications, while a few other provinces appear to have disclosed over 90% of their divorce petitions.Footnote 13 We should be confident that the conclusions I draw from my samples extend to the populations of divorce adjudications in Henan and Zhejiang to the extent that we are confident that unavailable decisions are not significantly and systematically different from those in my samples.Footnote 14

| Year | Henan | Zhejiang | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Civil affairs yearbook | Online | Proportion online (%) | Civil affairs yearbook | Online | Proportion online (%) | |

| 2009 | 10,767 | 3,927 | 36 | 20,522 | 388 | 2 |

| 2010 | 12,542 | 6,937 | 55 | 19,711 | 14,150 | 72 |

| 2011 | 6,908 | 6,940 | 100 | 19,903 | 4,895 | 25 |

| 2012 | 11,026 | 7,905 | 72 | 19,187 | 4,496 | 23 |

| 2013 | 20,668 | 13,462 | 65 | 19,191 | 6,453 | 34 |

| 2014 | 28,021 | 20,023 | 71 | 19,225 | 12,762 | 66 |

| 2015 | 34,934 | 12,908 | 37 | 20,122 | 16,512 | 82 |

| 2016 | – | – | – | 20,892 | 12,392 | 59 |

| Total | 124,866 | 72,102 | 58 | 158,753 | 72,048 | 45 |

Note: “Civil affairs yearbook” refers to the officially published number of first-instance divorce petitions adjudicated by courts (divorces granted and divorces denied by adjudication). Henan’s official 2011 figure of 6,908 divorce adjudications is likely an error.

Measures

When writing their decisions, judges are required to adhere to a standardized template set by the SPC. As discussed earlier, online court decisions are divided into sections, including the court name, the parties (litigants and their legal representatives), the main body of the decision containing the litigants’ statements, the evidence they submitted in support of their claims, the judges’ determinations of the facts, the judges’ holdings and final judgments, the judges’ names, and the decision date. Online court decisions are simply HTML files containing otherwise unstructured GB18030-encoded text. Their sections are demarcated not by headings, much less by delimiters, but rather by content cues: commonly used words and phrases. Relevant information must be parsed from large quantities of raw text written with varying vocabularies and styles. Judges express the decision to deny a plaintiff’s divorce request in a variety of ways. Plaintiffs make claims about domestic violence using a wide variety of words and expressions. Defendants express their unwillingness to divorce in different ways. Even the presentation of names, sexes, and birthdates of litigants is highly variable across court decisions. Dates are formatted in different ways. Numbers appear variously as Chinese and Arabic numerals. In short, court decisions are replete with inconsistencies and typos (Reference HeMa, Yu, and He 2016:199). Scholars must also be mindful of the existence of duplicates in online collections of court decisions (Reference HeYang, Tan, and He 2019:129).

The key sections from which I extracted and coded information are the following. The “parties” section includes selected information about the litigants and their advocates. The “facts” section includes litigants’ claims as well as arguments they made and evidence they submitted to the court to support them. This section also includes the court’s determination of the admissibility of the submitted evidence; the litigants’ objections to, agreement with, and cross-examination of evidence; and the court’s determination of the relevant facts of the case according to the litigants’ statements, arguments, and admitted evidence. Where applicable, it also includes findings of the court’s investigations, such as documents it requested from government agencies and witness testimony, sometimes from local authorities with knowledge of the matter in dispute. The “holdings” section contains the court’s legal rationale for its ruling(s), including the legal sources on which they are based. The “decision” section contains the verdict(s). Finally, the “tail” section contains the names of the involved court personnel, their roles (associate judge, assistant judge, lay assessor, or clerk), and the date of the decision (Reference DuBaidu 2020).Footnote 15

The technical challenges posed by the task of rendering text into quantitative data were multiplied by the sheer volume of text. The main sections of text in the almost 150,000 court decisions in my two samples consist of 202 million Chinese characters, Latin letters, and Arabic numerals (95 million and 107 million in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively). Applying conservative rules of thumb of 600 English words per 1,000 Chinese characters and 500 words of text per page, 202 million Chinese characters is over 240,000 pages of single-spaced English text.Footnote 16 If a 500-page ream of paper is 5 centimeters thick, then printing this much text would require a stack of paper 24 meters tall. Although hand-coding even a fraction of this much text would be hopelessly infeasible, the automated coding process nonetheless required a great deal of manual reading in order to develop and refine measures incrementally and iteratively through random audits – searching for errors by comparing quantitative codes with the original text from which they were derived. I hand-coded random samples and assessed the degree of consistency between the manual codes with the machine codes. Imperfection notwithstanding, they are highly accurate, reliable, and valid. Among 500 decisions I randomly selected from both samples, levels of agreement between hand codes and machine codes on all measures range from 78% to 100%, and are almost all well over 90%.Footnote 17 More details follow.

I took a keyword and keyphrase approach to constructing measures from the written court decisions. For the purpose of analyzing the decision to grant or deny a divorce petition (Chapters 6 and 8), I created a variable that limits the scope of analysis to first-attempt petitions. I also used this variable in analyses of the number of attempts and duration of time to win an adjudicated divorce (Chapter 9). Courts almost always cite in their decisions the case IDs of prior decisions pertaining to the dispute in question. I therefore coded as a subsequent-attempt divorce petition any first-instance divorce decision containing a reference to a previous civil case – either a specific civil case ID or a descriptive reference to a previous divorce litigation attempt. Descriptive references come from a wide array of words and phrases (e.g., 曾向本院起诉, 再次提出离婚, 再次诉至法院, 原告于[previous date]起诉要求离婚). I coded all remaining first-instance divorce decisions as first attempts. My analyses of child custody determinations include all divorces granted by adjudication regardless of how many attempts were necessary to get there.

Outcome Variables

The outcome measures I describe in this section correspond to the two sets of quantitative analyses at the heart of this book: the court ruling to grant or deny the petition and the court ruling to grant or deny child custody.

Grant or Deny the Divorce Petition. Adjudicated denials can be reliably identified by words and phrases in the “ruling” (裁判) section of court decisions, such as “deny” (不予支持 or 不予准许), “do not approve” (不准), and “reject” (驳回). Adjudicated approvals of divorce petitions can be identified by words and phrases, such as “approve” (准予 and 准许) and “dissolve” (解除), that do not satisfy the criteria for adjudicated denials.

Child Custody. In analyses of plaintiffs, the outcome is whether the court awarded child custody (yes or no) to the plaintiff. Likewise, in analyses of defendants, the outcome is whether the court awarded child custody to the defendant. I can also combine plaintiffs and defendants and consider whether the court awarded child custody to the mother or to the father. I machine-coded this dichotomous measure using combinations of words and phrases judges almost always used to record their decisions: “plaintiff” (原告), “defendant” (被告), “by” or “of” (由, used in “custody assumed by” or “under the care of”), “follow” or “go with” (随), “go back with” or “return to” (归), “custody” (抚养), and “live” (生活, used in “live with”). Judges generally referred to plaintiffs and defendants as such. For purposes of coding this and other variables, I substituted the personal names of litigants with their corresponding roles of “plaintiff” and “defendant.”Footnote 18

In cases of only-children, child custody is a zero-sum game: it goes to either the plaintiff or the defendant. In cases of siblings, child custody could be granted solely to the plaintiff, solely to the defendant, or to both. My measure does not consider joint custody – a situation in which custody of one child is granted to both sides – because it was practically nonexistent. Indeed, the legal term “joint custody” (轮流抚养) appeared in only five child custody verdicts in the Henan sample and four in the Zhejiang sample. To assess the accuracy of this measure, I hand-coded 100 randomly selected decisions. To my amazement, my hand codes and the machine codes were in perfect (100%) agreement.

Explanatory Variables

The measures in this section support my efforts to answer the following questions. How prevalent are domestic violence allegations in divorce trials? Consistent with the faultism divorce standard, does a domestic violence allegation increase the probability of a ruling to dissolve the marriage? Consistent with the breakdownism standard, does a defendant’s unwillingness to divorce increase the probability of a ruling to preserve the marriage? Which of these two standards matters more to judges? To what extent and in what ways do divorce outcomes vary by plaintiff sex? How do judges treat evidence? In what ways does case complexity – measured by the presence of marital property and/or minor children – influence judges’ rulings? How important are claims of physical separation? What happens when a plaintiff “voluntarily” gives up property and/or child custody claims? Do these various sources of influence on judicial decision-making vary by plaintiff sex?

Domestic Violence

Similar to Reference LuoLuo’s (2016:15n3) approach, I did not limit the definition of “domestic violence” to claims expressed by plaintiffs using this specific term (家庭暴力) or its contraction (家暴). I included a variety of additional, often colloquial, expressions for physical and verbal abuse commonly used by plaintiffs (e.g., 打骂, 打伤, 殴打, 动手, 毒打, 大打出手, 拳打脚踢, and 拳脚相加).Footnote 19 Consistent with previous estimates about the prevalence of domestic violence reviewed in Chapter 1, the incidence of domestic violence allegations was about 30% overall and almost 40% among female plaintiffs in both samples; about 90% of plaintiffs in both samples who made domestic violence allegations were women (Chapter 7). Although it includes a small share of false positives caused by male plaintiffs who made allegations of violence inflicted by their wives’ family members, this measure was generally very accurate. In my random audits, levels of agreement between hand codes and machine codes were 99% among 200 decisions from Henan (Cohen’s kappa = .97) and 95% among 100 decisions from Zhejiang (Cohen’s kappa = .89). Because marital rape lacks legal recognition in China (Reference FincherFincher 2014:145; Reference Honig and HershatterHonig and Hershatter 1988:277–78; Reference LiLi 2015b:170), it appears relatively rarely in court decisions. It can sometimes be inferred when women refer euphemistically to involuntary or forced sex (Chapter 7).

Defendant Consent and Defendant Absenteeism

I defined a defendant’s unwillingness to divorce using words and phrases such as “oppose,” “disagree” with, or “object” to the divorce (不同意离婚, 不同意与原告离婚, 不同意解除, 不愿与原告离婚, 不想与原告离婚, and similar variants), “I request that the court reject the plaintiff’s petition” (请求法院驳回, 请驳回, 希望法庭驳回, and similar variants), “I hope to reconcile with the plaintiff” (variants of 希望能和原告和好), and other relevant words and phrases. Defendants can only express consent or withhold consent if they participate in the litigation process, usually in person, in writing, or by proxy, but also occasionally by telephone. In order to assess the effect of consent, therefore, this variable also includes values for a defendant’s failure to participate in court proceedings. I defined the absence of defendant participation using phrases such as “failed to appear in court” (未到庭), “failed to provide a defense” (未做答辩), “failed to submit a defense statement” (未提交答辩状), “in absentia trial” (缺席审理), “refused to appear in court without due cause after being served a court summons” (经本院传票传唤无正当理由拒不到庭), and other relevant variants. The presence of the word “public notice” (公告) differentiates in absentia public notice trials in which defendants were alleged to be missing from other in absentia trials in which defendants were served by regular means because they were not alleged to be missing. This measure thus includes four values: (1) “defendant in absentia: public notice,” (2) “defendant in absentia: no public notice,” (3) “defendant consented to divorce,” and (4) “defendant withheld consent.” By including absentee defendants in this measure of defendant consent, we can be confident that the value of “defendant consented to divorce” captures a documented expression of affirmative consent and therefore excludes a failure to withhold consent owing to failure to participate in court proceedings. In a random audit of 100 court decisions, hand codes and machine codes for this measure were in agreement 98% of the time (Cohen’s kappa = .97).

As I discussed in Chapter 2, although divorces should be granted when defendants are declared missing (according to Article 32 of the Marriage Law), defendants whose whereabouts are alleged to be unknown are rarely declared missing. Defendants commonly failed to appear in court: they were no-shows in 35% and 29% of first-instance divorce adjudications in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively. More specifically, “defendant in absentia: public notice” and “defendant in absentia: no public notice” accounted for 12% and 23% of Henan’s main sample, respectively, and for 6% and 23% of Zhejiang’s main sample, respectively. In only a few cases in each respective sample, however, were defendants formally declared missing (被宣告失踪). Even though, with court permission, plaintiffs can be represented in absentia in civil trials, this almost never happens in divorce cases. Defendants withheld consent in 50% and 56% of all first-attempt divorce adjudications in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively, meaning they explicitly consented to divorce in 15% and 14% (Chapter 8, Table 8.6).

Litigant Sex

Personal details about litigants – including name, sex, date of birth, officially registered residential address, and ethnic group – are disclosed in the vast majority of decisions in the Henan sample: 94% of all decisions on first-attempt petitions include litigant sex (54,200 out of 57,502). In the Zhejiang sample, by contrast, only 3% of first-attempt decisions disclosed litigant sex (1,534 out of 51,573). Similarly, litigant sex was disclosed in 95% of all child custody rulings in the Henan sample but in only 3% in the Zhejiang sample. Courts in Zhejiang took great care to redact the personal identifying information of litigants and their family members. The redaction of litigant names precludes gender guessing on the basis of given names (typically only surnames were retained).

I was, however, able to infer litigant sex (both plaintiffs and defendants) with near-perfect accuracy from almost 7,000 additional first-attempt decisions (and from more than 2,000 additional subsequent-attempt decisions) according to the content of text about three gendered topics: (1) bride price (彩礼), (2) dowry (嫁妆), and (3) wives’ natal families (娘家). Because the bride price is paid by the husband’s family, a litigant’s statement concerning the plaintiff’s payment of bride price or the plaintiff’s request for the return of the bride price is a valid and reliable indication that the plaintiff is male. Because the dowry is paid by the wife’s family, language in a court decision claiming or affirming the plaintiff’s payment of the dowry or the plaintiff’s request for its return is a valid and reliable indication that the plaintiff is female. Likewise, a statement concerning the plaintiff’s receipt of – or obligation to return – the bride price or dowry indicates that the plaintiff is female or male, respectively. Finally, a litigant’s statement concerning the plaintiff’s return to “the wife’s natal family” is a valid and reliable indication that the plaintiff is female.Footnote 20

I assessed the reliability of this method of inferring litigant sex by comparing inferred sex with disclosed sex. The level of agreement between the two values of sex among the 474 litigants in the Zhejiang sample with both was 97% (Cohen’s kappa = .95). Applying the same method of inferring sex to the Henan sample is a far better test of its accuracy. Thanks to high rates of disclosing litigant sex in Henan, its sample is an ideal source of “training data” for machine coding litigant sex. The level of agreement between the two values of sex among the 27,434 litigants in the Henan sample with both was 96% (Cohen’s kappa = .91). Plaintiff sex in my main Henan sample (n = 54,200) comes exclusively from the published court decisions because I would have gained only an additional 570 court decisions (1%) by inferring litigant sex in decisions that did not originally disclose it. Of all values of plaintiff sex in my main Zhejiang sample (n = 8,626), 83% were inferred.

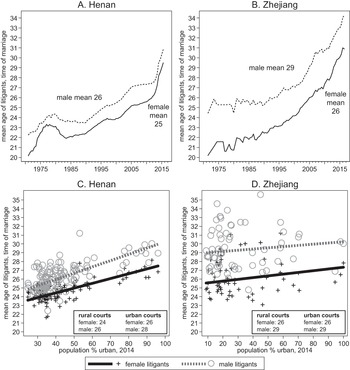

Figure 4.5 shows that, consistent with previously published estimates reviewed in Chapter 1, women accounted for 66% and 67% of all plaintiffs in the main Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively. While the gap persisted across levels of urbanization in both samples, Panel C also shows that it narrowed with urbanization in the Henan sample. Indeed, in the urban districts of the provincial capital of Zhengzhou, in which 4.6 million resided in 2014, almost 90% of whom were urban, plaintiffs filing for divorce for the first time were split evenly between women and men. Panel D shows that the gap narrowed to a much lesser extent in Zhejiang. Overall, female plaintiffs outnumbered male plaintiffs by a 2:1 ratio in both samples.

Figure 4.5 Gender composition of plaintiffs filing first-attempt divorce petitions

Note: n = 54,200 and n = 8,626 first-attempt adjudicated decisions (granted or denied) from Henan and Zhejiang, respectively. Panels A and B are smoothed with moving averages. Scatterplot points represent courts. Each court is represented twice, once for women and once for men. Panel C depicts 161 basic-level courts, including 88 county and 21 county-level city courts. Henan’s 53 urban district courts are aggregated to their 17 prefecture-level cities. Kaifeng’s Xiangfu District People’s Court is represented twice because prior to December 2014 it was named the Kaifeng County People’s Court. Thus, Panel C depicts 126 administrative units (88 + 21 + 17 = 126), once for women and once for men (252 points). Panel D depicts 91 basic-level courts (182 points). Panels C and D contain best-fit lines for female and male plaintiffs.

Civil Procedure

Information about judges reflects both the civil procedure (simplified or ordinary) and the composition of the collegial panel when the ordinary civil procedure was applied. A collegial panel of judges implies the application of the ordinary civil procedure. Measured this way, the ordinary civil procedure was applied in 59% and 17% of all first-attempt divorce adjudications in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively. Over time, however, the two provinces began to converge in their embrace of the simplified civil procedure (Chapter 5).

The presence of a solo judge is redundant with language in a written decision indicating the use of the simplified procedure (适用简易程序). I validated my measure of the simplified civil procedure, coded according to whether the case was tried by a solo judge or a collegial panel, with a separate measure, coded according to the presence of terms for “simplified procedure” (简易程序) or “solo judge” (独任法官, 独任审理, or 独任审判) and the absence of the term “ordinary procedure” (普通程序) in the text of the court decisions. The two codes are identical in 98% of all decisions in each province’s main sample. This measurement is further validated by the near-universal application of the ordinary civil procedure in public notice trials. As mentioned in Chapter 2, courts are prohibited from applying the simplified procedure when the defendant’s whereabouts are unknown. In both main samples, the ordinary civil procedure was applied in virtually every case (99%) coded as a public notice trial. Therefore, in order to avoid multicollinearity (i.e., in order to ensure that this variable is not redundant with the “defendant consent and absenteeism” measure discussed above), I assign a value of zero both to cases tried according to the simplified procedure and to public notice trials, and a value of one to all remaining cases tried according to the ordinary civil procedure.

Evidence

I used variants of phrases containing “plaintiff supplied” (原告提供) and “plaintiff submitted” (原告提交) in conjunction with evidence (证据) to measure whether or not plaintiffs submitted evidence. This code also incorporates language that describes, without the use of the word “evidence,” plaintiffs’ submission of relevant materials to support or prove their claims. Court decisions in Henan’s main sample were far less likely than those in Zhejiang’s main sample (50% and 82%, respectively) to indicate that the plaintiff submitted evidence. In my random audits, levels of agreement between hand codes and machine codes were 97% among 200 decisions from Henan (Cohen’s kappa = .94) and 98% among 100 decisions from Zhejiang (Cohen’s kappa = .92).

Children

I coded the presence of children using a variety of words and phrases for giving birth (e.g., 女儿, 生女, 生一女, 生下女, 儿子, 生男, 生一男, 生下子, 生下儿, 生子, 生儿, 婚生, 生育) while also doing my best to exclude those preceded by “did not” (e.g., 未生育). A different code for the presence of a child custody ruling automatically triggers a code for the presence of children. Although adoption is rare, it too is included in this measure. Inconsistently disclosed details about children prohibits distinguishing adult children from minors. Most first-attempt divorce adjudications involved children: about 80% in both samples. In my random audits, levels of agreement between hand codes and machine codes were 98% (Cohen’s kappa = .92) among 200 decisions from Henan and 100 decisions from Zhejiang.

Property

I coded the apparent absence of marital property using variants of the statement, “there is no common property” (e.g., 无[or 没有]共同财产, 无[or 没有]夫妻共同财产, 无[or 没有]家庭共同财产, 无家庭财产, and 婚后无财产). Most first-attempt divorce adjudications involved marital property: 90% in both samples. In my random audits, levels of agreement between hand codes and machine codes were 99% among 200 decisions from Henan (Cohen’s kappa = .96) and 99% among 100 decisions from Zhejiang (Cohen’s kappa = .94).

Claim of Physical Separation

I identified claims of physical separations fairly broadly using phrases containing the word “separation” (e.g., 分居至今, 分居生活至今, 长期分居, 一直分居, and many similar variants) as well as the word “separation” alone (分居) in conjunction with a date or duration of time, as indicated by the presence of the word “year” (年) in close proximity. I also used terms that express the meaning of separation without using this specific word, such as not living together (e.g., 无共同生活, 没有在一起生活), also in conjunction with a date or duration of time. Of all divorce petitions in the main samples, 41% and 52% included claims of physical separation in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively.

Plaintiff Gave Up Property or Child Custody

In her pathbreaking research on divorce and gender in rural China, Ke Reference LiLi (2015a, 2015b) reports that women are often forced to bargain away marital property and child custody in exchange for their freedom. I identify instances of plaintiffs’ giving up claims to property and child custody using expressions that appear in plaintiffs’ statements, including “express my willingness to give up” (表示放弃), “voluntarily give up” (自愿放弃), “the plaintiff gives up” (原告放弃, 原告可放弃, or 原告均放弃), and many additional combinations of the word “give up” or “waive” in conjunction with “property” (财产) and “custody” (抚养). Concessions such as these were explicitly recorded in the decisions of only 7% and 3% of first-attempt divorce adjudications in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively. Judges did not always document informal off-the-record sidebar negotiations in which they, together with defendants and lawyers, pressured women to concede their property and/or child custody claims (Chapter 10; Reference LiLi 2022).

Number of Children and Their Sex Composition

All analyses of child custody orders are limited to eligible children, and thus exclude those who were 18 years of age or older at the time of the trial. For example, in a case of a couple with one 22-year-old daughter and one 13-year-old son, only the son would be included in the analysis. Chinese characters denoting the sex of the child used in judges’ statements about which side was awarded custody are “子” and “男” for “son” (婚生子, 儿子, 男孩, etc.) and “女” for “daughter” (婚生女, 女孩, etc.). By counting each instance a son and each instance a daughter was assigned to a parent, I can, for each decision, easily calculate the number of children subject to a child custody order and their sex composition. By linking the sex of the child to the sex of the litigant, I can also easily code mothers and fathers who were respectively awarded custody of a son, of a daughter, of two daughters, of two sons, and of one son and one daughter. This variable includes seven values: (1) one daughter, (2) one son, (3) one of each, (4) two daughters, one son, (5) one daughter, two sons, (6) two or more daughters, and (7) two or more sons. Chapter 11 is devoted to analyses of the number and sex composition of children within families and their effects on child custody outcomes. In 100 randomly selected decisions, the level of agreement between hand-coded and machine-coded values is 94% (Cohen’s kappa = .91).

Let me illustrate my coding method with a few concrete examples. First, “Daughter Zhang One X and Son Zhang Two X shall live with the defendant” (女儿张一×、男孩张二×随被告生活) is accurately machine-coded as custody of two children (one girl and one boy) assigned to the defendant (whom we know to be male). Second, in a typical example of a court splitting up siblings, “Custody of older daughter Jiang X Ling is granted to the plaintiff, custody of subsequent daughter Jiang X Tian is granted to the defendant” (原被告婚生长女江某玲由原告抚养, 次女江某天由被告抚养) is accurately machine-coded as each parent gaining custody of one daughter. Third, in another example of a court splitting up siblings, “Custody of son Zhou X One is granted to the defendant and custody of subsequent son Zhou X Two is granted to the plaintiff” (婚生长子周某乙由被告抚养, 婚生次子周某丙由原告抚养) is accurately machine-coded as each parent receiving custody of one son. Finally, “Daughter Ye X One shall live with the plaintiff and son Ye X Two shall live with the defendant” (婚生女儿叶某乙随原告生活, 儿子叶某丙随被告生活) is accurately machine-coded as custody of one daughter assigned to the plaintiff (whom we know to be female) and one son assigned to the defendant (whom we know to be male).

In order to simplify the presentation of multivariate regression results in Chapter 11, I collapsed all sex combinations of siblings into a single category. In the case of siblings, the same code is assigned to two girls, two boys, and one of each. Thus, I coded three values for the variable measuring the number and sex composition of children: (1) only-daughter, (2) only-son, and (3) siblings.

In compliance with a requirement in the 2013 Provisions to protect the privacy of minors, courts often redacted children’s dates of birth. I therefore did not attempt to parse children’s birthdates. In court decisions, birth order is sometimes denoted by characters for “older” or “first” (长, 大, etc.) and “younger” or “subsequent” (小, 次, 二, 2, etc.). Courts typically used words such as these only in cases of same-sex siblings in order to differentiate, say, two daughters (i.e., older daughter versus younger daughter). Mixed-sex siblings could be easily differentiated (i.e., daughter versus son) without birth order words. Because court decisions list children in chronological birth order (oldest to youngest), I was able to code the birth orders of some but not all of the litigants’ children. Children over the age of 18 are not subject to child custody determination and are therefore excluded from child custody orders. Although birth order is not a central part of my analysis of child custody determinations, we will see that it brings son preference into high relief.

Claiming Child Custody

Judges recorded litigants’ requests for child custody using terms such as “requested custody” (要求抚养), “live with me” (随我生活), “return to my custody” (归我抚养), and “under my custody” (由我抚养) appearing in plaintiffs’ legal complaints and defendants’ defense statements. Although litigants in these selected examples referred to themselves in the first person, many referred to themselves in the third person as “plaintiff” and “defendant.” I coded four values: (1) plaintiff yes, defendant no, (2) both yes, (3) plaintiff no, defendant yes, and (4) neither. In most cases involving a child custody decision, custody was requested by either the plaintiff alone (43% and 41% in Henan and Zhejiang, respectively) or both sides (36% and 41%, respectively). This measure does not distinguish a request for two or more children (among siblings) from a request for only one child. In 100 randomly selected decisions, the level of agreement between hand-coded and machine-coded values is 81% (Cohen’s kappa = .68). Coding errors are concentrated in the last two values. Limiting the assessment of accuracy to the first two values, which account for about 80% of all child custody decisions in my samples, increases the level of agreement between hand-coded and machine-coded values to 92% (Cohen’s kappa = .83).

Physical Possession of a Child

Owing to the importance of the physical possession standard, the residential circumstances of the child is reported in about two-thirds of decisions made by rural courts and a somewhat lower proportion of decisions made by urban courts (see Table 11.1 in Chapter 11). I coded physical possession according to combinations of the words “plaintiff,” “defendant,” “currently” (现, 目前), “continuously” (一直), “long-term” (长期), “with” (跟), and “of” (由, used in “in the custody of”) appearing in conjunction with either “plaintiff” or “defendant.”Footnote 21 As I did for my measure of claiming child custody, I coded four values: (1) plaintiff yes, defendant no, (2) both sides, (3) plaintiff no, defendant yes, and (4) neither side or undisclosed. A code of two usually refers to parents in the same household or siblings who have already been split up by separated parents. Rarely does it mean both parents claimed to have physical possession of one or more children. Values of one and three include parents with sole possession of all children subject to a custody determination – an only-child or all siblings. A value of four includes cases in which the physical location of the child was either undisclosed or expressed using language not incorporated into my coding method.

I assessed the accuracy of the machine codes by comparing them to hand codes in 100 randomly selected decisions. Almost every error is confined to the fourth value. Overall, the level of agreement between hand-coded and machine-coded values is 78% (Cohen’s kappa = .68). Excluding values of four, however, the level of agreement is 99% (Cohen’s kappa = .97). Many values of four reflect truly undisclosed physical locations. But many also reflect alternative ways – beyond the scope of my coding method – in which judges conveyed information about children’s physical locations.Footnote 22 For these reasons, the first three values can be regarded as almost perfectly accurate, and the fourth value should be regarded as somewhat less accurate. In child custody cases in which physical possession was unambiguous, children were far more likely to be living with plaintiffs than to be living with defendants (Chapter 11).

Urbanization

Ignoring regional variation and instead, as scholars who apply macro-comparative cross-national research designs tend to do, treating China as internally homogeneous would be a mistake (Reference Berkovitch and GordonBerkovitch and Gordon 2016). Perhaps the most salient social category shaping opportunity structures and life chances in China is household registration (hukou, 户口) status, which classifies people as either rural or urban. Because of the all-encompassing significance of its rural–urban divide, China is characterized as “one country, two societies” (Reference WhyteWhyte 2010), a “two-class society” (Reference TreimanTreiman 2012), and “caste-like” (Reference Gong and DuttonGong 1998). Although constraints on geographical mobility have relaxed over time, as evidenced by China’s massive “floating” population of over 200 million migrants “living away from their places of hukou” (Reference Liu, Liang and MichelsonY. Liu et al. 2014:50), most of whom are rural-to-urban migrants, a deep institutional chasm dividing China’s rural and urban populations persists.

As discussed earlier, I classified courts dichotomously as either rural or urban according to the administrative status of the jurisdiction to which they belong. In some descriptive analyses, I treat urbanization as a continuous variable. China’s National Bureau of Statistics reports national- and provincial-level urbanization as the proportion of the population residing in cities and towns (城镇人口). At the provincial level, using this measure, Zhejiang was far more urbanized than Henan in 2014 (65% versus 45%) (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2015:7). In Henan, as we saw earlier in Table 4.1, sub-provincial levels of urbanization in counties, county-level cities, and urban districts are reported using the same measure (Henan Provincial Bureau of Statistics 2015:871–73). In Zhejiang, however, this measure is available only for prefectures. The only measure of urbanization available for Zhejiang’s counties, county-level cities, and urban districts is the proportion of the population registered by the public security administration as nonagricultural (非农业人口) for household registration (户籍) purposes (Zhejiang Provincial Bureau of Statistics 2015:46–48). Among Zhejiang’s 11 prefectures, these two measures are correlated at R = .58 (P = .06). Because the “nonagricultural” population is considerably smaller than the “urban” population, presumably because many people who belong to the “agricultural” population officially registered in villagers are actually residing in urban areas, we cannot compare urbanization levels between Henan and Zhejiang at the most granular sub-provincial level. In Table 4.1, what appears to be lower levels of urbanization in Zhejiang than in Henan is simply an artifact of measurement differences. Comparisons within provinces, of course, are perfectly valid.

While it generally holds up well, my method of classifying courts as rural and urban according to the administrative status of their jurisdictions is imperfect. To be sure, by definition, “urban” courts are far more urbanized than “rural” courts: in “rural” and “urban” courts, respectively, average levels of urbanization were 37% and 73% in Henan and 21% and 51% in Zhejiang (Table 4.1). However, Henan’s Yima Municipal People’s Court is classified as “rural” (because it is in a county-level city) even though 96% of its population were urban residents in 2014. On the flip side, in both provinces, several courts in urban districts in the outskirts of cities are classified as “urban” even though the populations they served were predominantly rural.Footnote 23

Court decisions do not consistently disclose the residential locations of litigants. But the nearly 15,000 divorce decisions in my samples that do disclose at least counties or cities of residence, including the almost 4,000 that disclose detailed residential addresses, show that court locations reflect divorce litigants’ officially registered residential locations. This should not be surprising given that plaintiffs, upon filing their petitions, are required to satisfy jurisdictional standing requirements. The Civil Procedure Law stipulates that court petitions should, under most circumstances, be filed in the defendant’s place of residence (Article 21), which practically speaking usually means the defendant’s place of hukou registration and which, in the case of divorce, is usually the same as the plaintiff’s.

Recall that each county, county-level city, and urban district has one regular basic-level people’s court. Plaintiffs who file for divorce are, by and large, tethered to the basic-level courts in the counties, county-level cities, or urban districts of their officially registered residential addresses. Most plaintiffs and defendants – 94% and 97% in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively – shared the same city or county. A smaller proportion – but still a majority – of plaintiffs and defendants shared the same address. Among plaintiffs and defendants whose detailed residential addresses were disclosed in the court decisions, 61% and 60% in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively, lived together at the time of the adjudication. But even when they were physically separated, most plaintiffs and defendants – 85% and 79% in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively – shared the same court jurisdiction. Finally, consistent with China’s civil legal principle of privileging the defendant’s jurisdiction, among the relatively few plaintiffs and defendants who lived in separate court jurisdictions, most plaintiffs – 84% and 91% in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively – filed their first-attempt petitions in defendants’ court jurisdictions. Overall, 99% and 98% of plaintiffs in the Henan and Zhejiang samples, respectively, filed their first-attempt petitions in courts with jurisdiction over defendants’ residential locations.