16.1 Introduction

In 2016 a full-page advertisement was placed by 56 Australian scientists in the Brisbane Courier Mail. The context of the advertisement was the continuing commitment of Australian governments, federal and state, to coal mining and coal-fired power stations despite overwhelming evidence connecting this activity to the severe damage being suffered by the Great Barrier Reef (Hoegh-Guldberg, Reference Hoegh-Guldberg2015). As well as presenting their scientific credentials in the advertisement – together they had devoted more than 1200 years to studying climate change, marine ecosystems and the Great Barrier Reef – the scientists prioritised the Reef’s economic value over its conservation values. The burning of fossil fuels, they wrote, is ‘directly threatening a major economic resource. The World Heritage listed Great Barrier Reef earns multiple billions for the economy and provides jobs to tens of thousands of Australians’ (Courier Mail, 2016). ‘[T]here can be no new coal mines …’, the scientists demanded, and ‘No new coal-fired power stations’.

This attempt to influence public opinion and thus political outcomes through media appeared in the face of what is now recognised as one of the world’s most notable failures in conservation: the continuing destruction of a global nature ‘superstar’. We suggest in this chapter that such public acts are often rendered futile because of a poor understanding of the communicative processes underpinning the research-to-policy pathway. This is troubling given the risks some scientists – working within expectations of independence and measured professional response – take when entering public debate. But this is only part of the story. While many scientists do not have the necessary communication skills or knowledge to join controversial debates (Besley & Tanner, Reference Besley and Tanner2011) or have been burned by previous experience (Dunwoody, Reference Dunwoody, Hansen and Cox2015), there is also evidence that others see themselves as remote from the public sphere, a messy space of negotiation and contest that has a clearly troubled relationship with fact (Besley & Nisbet, Reference Besley and Nisbet2013; Dudo & Besley, Reference Dudo and Besley2016; Simis et al., Reference Simis, Madden and Cacciatore2016).

In this chapter, we highlight aspects of this disconnection between environmental science and public debate and policy outcomes from a media and communication perspective. We begin by briefly outlining recent approaches to mediated environmental communication. We then turn to the communication of science more specifically. We argue that models of science communication and public engagement with science need to more explicitly acknowledge issues of power, complexity and conflict within the context of the contemporary media landscape. To conclude, we offer suggestions for how science and communication can be better equipped to influence environmental debate and decision-making.

16.2 Mediated environmental communication

As a starting point, we need to recognise the inherently political nature of environmental and conservation sciences – that even at their least political, they seek to influence behaviours and outcomes, and at their most political they are resisting global pressures for intensified use of land and water and increasing demand for and movement of resources. The politics of the environment consistently test our capacity to civilly negotiate a shared future (Cox, Reference Cox2012; Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2013), whether that concerns the composition of our atmosphere or the fate of a small localised fishery (Murphy, Reference Murphy2017). That environmental activists and journalists are greater targets of violence than ever before in many parts of the world is evidence not only that resource management and conservation are areas of conflict, but that what is said, how and to whom clearly matters (Cottle et al., Reference Cottle, Sambrook and Mosdell2016; Lester, Reference Lester, Tumber and Waisbord2017). Media and communication are central to this flow or containment of environmental information and meanings. As such, here we briefly outline key ideas from communication and media studies as they relate to environmental debate and decision-making.

As others before them, media and communication scholars have turned to nature for useful metaphors to help describe some of the dynamism and complexity they now witness. ‘Media ecology’ is a popular term to capture the interconnection of various media systems, platforms, technologies, genres, formats, and producer and audience practices driving media production and distribution (Altheide, Reference Altheide1994; Singer, Reference Singer2018). How, and to what extent, this metaphor should be applied remains contested (Maxwell & Miller, Reference Maxwell and Miller2012; Lester, Reference Lester2019). Nevertheless, a focus on interconnectivity within media and communication is useful in highlighting the interactions and dynamism of contemporary spheres for public and political negotiation (Habermas, Reference Habermas and Burger1989; Fraser, Reference Fraser2007).

An immediate outcome of applying this metaphor is the redundancy of the definite article in relation to ‘media’. Once it may have made sense to refer to ‘the media’ as a bounded entity, in which media companies hired journalists, editors and camera operators to produce information in the form of news and entertainment that was circulated via newspapers and broadcast outlets to readers and viewers. Now, the use of ‘the’ in front of ‘media’ is as anomalous as it would be if used in front of ‘nature’. Media are no longer separable from our social lives or indeed our environmental futures (Deuze, Reference Deuze2012). Media shape and frame our everyday life, including political decisions. They are the principal means through which we form a shared understanding of the world and come together to debate and negotiate common risks and concerns.

A second outcome of recognising ecological-type interconnectivity within a media and communication context is the acknowledgement of interaction. It is almost impossible to isolate environmental concerns and risks and the decisions they prompt to a defined locality. When residents in Mackay, Queensland, protested against the impacts of the proposed port expansion on the Great Barrier Reef, they entered a world that stretched communicatively from their local newspaper, to a series of NGO-established hashtags, to transnational corporations that sell ice cream, to European banks, to a US president and his daughters, to international governance bodies (Lester, Reference Lester2016; Foxwell-Norton & Lester, Reference Foxwell-Norton and Lester2017). And back again. Claims by industry of a ‘social licence to operate’ can be challenged when an ‘affected public’ is no longer defined as those living within a 20-km radius of a development site. We might all consider ourselves affected when the future of the Great Barrier Reef is concerned, and media and communication provide us with the means of engaging, and the sense that we have a right and duty to be involved openly in decisions about its future (Volkmer, Reference Volkmer2014).

Dynamism is the third element to be considered. As the traditional business model for the production of news has collapsed, numerous other forms of information production and circulation have emerged. All are constantly adjusting and changing their practices in relation to one another. NGOs collate and publish information on illegal logging in places where it is now too dangerous or expensive for income-losing news organisations to send their journalists. Citizens establish community websites for local audiences or single-issue blogs for targeted business readers. News outlets campaign on climate change to attract subscribers, or do not cover climate change at all if it attracts too few site visits. Other media outlets closely guard a political and/or conservative readership, muscling out potential competitors with tactics sometimes bordering on bullying, in order to maintain a reputation for political influence (McKnight, Reference McKnight2012). Meanwhile, audiences have more choices than ever on what news they will receive and via what platform, self-selecting, re-selecting and screening sources, topics and subject matter via news feeds, hashtags and new sites selection.

Power plays a key role in structuring this interconnected, interactive and dynamic system. Within media and communication, power appears in diverse and often surprising forms, and even ownership of mega-media companies is no guarantee of uninterrupted influence, as both Rupert Murdoch and Mark Zuckerberg have experienced. Power is never certain, although it holds true that some conditions enhance the capacity to control information as it travels. Information emanating from institutional settings, such as universities, scientific organisations, courts, parliaments or international governance bodies, can often travel with authority for longer than NGO-sponsored communications. However, the long-running clash in the Southern Ocean between the NGO, the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, and the Japanese government-backed whaling fleet provides an excellent example of how geography impacts this. Throughout much of the conflict, Sea Shepherd was able to capitalise on the remote location of the conflict, from which journalists were absent, by producing and distributing images and messages that circulated within media relatively unchallenged. Symbolic power is key here. No amount of Japanese government-sponsored public relations or ‘scientific knowledge’ was able to successfully counter the messages carried by the bloodied corpses of ‘charismatic megafauna’ (McHendry, Reference McHendry2012; Cox & Schwarze, Reference Cox, Schwarze, Hansen and Cox2015).

Environmental NGOs have pioneered the strategic management of symbolic power within media and communication, and here conflict is often a necessary component. Sophisticated multi-pronged campaigns with minimal financial resources have threatened and interrupted the multimillion-dollar flow of goods and capital. The campaign aimed at Japanese buyers of Tasmanian native timbers involved a young woman in a tree with a laptop and a daily blog (albeit for over a year); a string of social media-active international backpackers and celebrity visitors; a single campaigner in Japan translating various media texts; and access to the email addresses of key corporate and social responsibility personnel in relevant Japanese companies (Lester, Reference Lester2014). The Sarawak-based forestry company at the centre of the trade quickly altered its business practices in Tasmania once the Japanese companies withdrew from contracts rather than be seen to be failing to meet their own environmental procurement principles.

This terrain is media saturated, and the role of media and communication is more than mere conduits for data or messages. Modern environmental conflict is hugely influenced by media, as the ‘product of mutually constitutive interactions between activism, journalism, formal politics, and industry’ (Hutchins & Lester, Reference Hutchins and Lester2015, p. 339) enacted in the public sphere. Activists’ strategies and campaigns, journalistic practices and news reporting, formal politics and decision-making processes, and industry activities and trade coalesce to enact moments of environmental conflict in public view. These moments of conflict largely centre on the legitimate dimensions of local, national and international policy and law, underpinned by the pursuit of environmentally sustainable development (Konkes, Reference Konkes2018; Foxwell-Norton & Konkes, Reference Foxwell-Norton and Konkes2019).

For example, state, NGO and industry responses to Japanese whaling conflicts in the southern oceans drew heavily upon the duties of signatories to the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling, that for over 30 years has delivered a commercial whaling moratorium. Sea Shepherd undertook protest action, with international laws and policy aiming to deliver whale conservation underpinning its media-based efforts, holding nations and industries to institutional and public account. Science was used both to support conservation via the International Whaling Commission (IWC) and to challenge it via the research claims of Japanese whaling fleets. Meanwhile, the IWC’s pursuit of conservation management plans, sanctuaries and marine parks has been underpinned by science that seeks to balance whale populations with the impacts of industry, even when not explicit. Science and scientific knowledge are thus very much a part of these conflicts, powerful, contested factors in contemporary social relations.

Media and communication form an interconnected, interactive and dynamic system, in which power, conflict and threat to established practices and order are always evident. As with any complex ecology, this is delicately balanced and easily interrupted, constantly adjusting and shifting as its component parts struggle for sustainability and/or dominance. They remain integral to the formation of public opinion and the political influence that follows, but contemporary flows and networks of information make the paths from source to policy more difficult to predict than ever. In the next section, we contrast this view of media and communication with that circulating around environmental sciences.

16.3 Communicating environmental sciences

If the view we have presented of media and communication is of a highly political, dynamic and complex system – one that is central to social life and environmental decision-making, but that does not easily lend itself to being understood or charted via neat models – the environmental sciences can present a near opposite view. Communication here is often an add-on activity, and ‘the media’ considered a relatively stable platform or tool to deploy as needed in order to change public opinion and produce policy outcomes. Indeed, a key premise in recent literature is the idea of ‘protecting science communication’ from the dynamism and noise characteristic of public debate and controversy, and of an active separation of science communication from political communication (Hall Jamieson, Reference Hall Jamieson, Hall-Jamieson, Kahan and Scheufele2017; Kahan et al., Reference Kahan, Scheufele, Hall Jamieson, Hall-Jamieson, Kahan and Scheufele2017). Here, ‘science and its communication’ rather than ‘communication and its implications for science’ has underpinned scholarship, leaving science seemingly remote from, rather than a part of, the public.

In considering how this situation has developed, we turn to a subset of literature that is not so interested in public understanding of science as scientists’ understanding of ‘the public’. In a review of findings from surveys of scientists, Besley and Nisbet (Reference Besley and Nisbet2011) found that, when asked about the role of the public, ‘scientists may opt for some type of co-decision-making but also suggest a desire by scientists to differentiate themselves from the public’. Their relevant findings include the following.

Scientists say the main barrier to ‘greater understanding of science’ among the public is lack of education. Media are second.

Scientists see the public as homogenous – although experience interacting with the public can bring a more nuanced view. Scientists perceive policy-makers as the most important group with which to engage, with the public in the mid-range of importance – somewhat more important than young people or NGOs, but less important than the private sector and educators.

Scientists appear to rely on a simple sender–receiver model of media effects that fits poorly with contemporary media research, that is, they ‘tend to favour one-way communication with the public via the media, viewing engagement as chiefly about dissemination rather than dialogue’ (Besley & Nisbet, 2011, p. 653).

Overall, scientists are willing to engage directly with citizens but ‘such engagement is usually still framed in terms of providing information’ ‘to increase citizen knowledge’ (Besley & Nisbet, 2011), while addressing the knowledge deficit and/or ‘scientific literacy’ still dominates scientists’ communication goals (Peters & Dunwoody, Reference Peters and Dunwoody2016).

This transmission model of communication (Shannon & Weaver, Reference Shannon and Weaver1949) – underpinned by a desire for a clear channel of communication that protects the message on its route from sender to receiver – has serious implications for public understanding, awareness and/or engagement with conservation and other sciences. It epitomises frustrated attempts to eliminate ‘noise’ – that is, to control the ‘message’ on a path to the public or policy and decision-makers. In the case of science, and more specifically conservation and ecology, the greatest ‘noise’ is the sound that resonates in the public sphere when citizens and scientific expertise collide. Exploring this noise requires a thoughtful and critical examination of the structural characteristics of this collision, and how this may impact the passage of scientific knowledge to citizens. This is difficult work, occurring in a space where diverse publics and communities with a range of understandings about scientific expertise and/or the primacy of economic imperatives reside. Instead, a range of contexts, influences and often conflict await the path of scientific knowledge to the public. Public understandings of science cannot be divorced from these social processes, and a ‘pure and protected’ science message, unsullied by politics, is unlikely to arrive untouched at its destination audience.

Citizens enter the public communication of science as social, political and cultural beings with a range of historical and contextual nuances. The underlying assumption of communication as mere transmission of data – as a controllable process – will often fail to register the impacts sought and may act to reinforce the communicative distance between scientific expertise and the citizens to whom their message is directed. While some effort has been made to abandon communication models that are based upon ‘knowledge deficit’, the model is still evident in many attempts to distribute scientific research and findings to the public. A carefully crafted tweet, a multimillion-dollar documentary or a full-page advertisement framed by 1200 years of expertise and experience of Great Barrier Reef scientists or equivalent is communication that often underestimates the conditions within which these citizens reside. What is heard by the public can be quite distant from the sender’s intent.

16.4 Better conservation communication

We suggest some key strategies that might help in the communication of conservation. The starting point must be a consciousness of one’s own role – a critical self-reflexivity – that positions science and its communication as only one of many domains of legitimacy and authority in conservation debates and efforts. There are other sources that carry legitimacy and authority in the public and private lives of individuals, institutions and their societies and these also command a place in public communication about conservation. This ‘communication noise’ cannot be bypassed and is indeed a distinctive characteristic of the current era. When conservation science enters this messy sphere of debate, it becomes enmeshed in the public realm of politics and political communication. Efforts to ‘secure’ a message to an audience, even via the expensive production of one’s own media content, underestimate communication’s complexity and unstable networks of connectivity. Seeking innovative collaborations with communication scholars, and inviting their meaningful participation in the constitution and design of research projects, is one way in which conservation scientists might better prepare their work for public deliberations.

Popular messages are not necessarily wedded to scientific rigour, expertise or fact. In the twenty-first century, scientists are encouraged to communicate their knowledge widely, making it increasingly susceptible to challenge and disrepute. An understanding of how science is embedded and implicated in processes of public debate and negotiation may reorient these communication strategies. For example, by prioritising the scientific and economic imperatives to protect the Reef, as evident in our opening example, the scientists could actually have affirmed the powerlessness of the public in relation to the destruction of the Reef, especially when even experts are compelled to take out full-page advertisements in a state newspaper. Conversely, communicating the Reef as a scientific fact and an economic resource may alienate already marginalised public sentiments that do not prioritise this message in their own experience of or relationship with the Reef.

Further, when scientific messages are framed with deliberate reference to the ‘economy’, including the tourism and mining industries, the impacts of mining and tourism on the Great Barrier Reef and the science are (again) diluted by a perhaps unwitting collusion with industry – as has been repeated in the history of Reef policy and protest moments (see Foxwell-Norton & Lester, Reference Foxwell-Norton and Lester2017; Foxwell-Norton & Konkes, Reference Foxwell-Norton and Konkes2019). Conservation science may do better to elevate the impact on the Reef’s ecology, and return to its messages of connectedness between human and natural systems. Is the Reef not worth protecting in itself? In the 1960s, the emergent discipline of ecology was evoked to argue that a mining lease on one part of the Reef would have dire consequences for the entire Reef ecosystem (McCalman, Reference McCalman2013). This ecological approach requires ongoing critical reflection on the concept of ‘ecologically sustainable development’ and the relationship of research to a system of industrial development that threatens ecologies everywhere (Redclift, Reference Redclift2005). Suffice to say, much public trust in science is at stake in these reflections.

In the longer term, better conservation communication can also be fostered in training and development. The distance between the ‘two cultures’ or, more specifically, the humanities, arts and social sciences and that of the science, technology, engineering and mathematics disciplines, is shrinking, but not fast enough. Clearly, neither ‘culture’ alone is sufficient to arrest the current trajectory of ecological decline. As researchers, we must continue to challenge false dichotomies that diminish scholarly contributions to conservation efforts – from global superstar ecologies like the Great Barrier Reef to the local ecologies of the places we live (Foxwell-Norton, Reference Foxwell-Norton2018). This distance can also be lessened in the design of degree programmes and training courses, giving current and next-generation science communicators access to different ways of thinking about their role, their potential place in public sphere debate, and the public.

In the twenty-first century, where networks of communication link individuals and civic institutions through digital media and mobile communication, a sophisticated understanding of communication is power (Castells, Reference Castells2013). Communication scholars are well-equipped to assist scientists, and their disciplinary communicators, to extend existing understanding of communication, media and journalism. This entails a re-examination of what is meant by ‘science communication’ and its current strategies to engage citizens in support for, and trust in, its work and expertise. Currently, such collaborations overwhelmingly favour scientific expertise, leaving communication expertise (beyond media industry experience or production expertise) underrepresented, despite its potential to add critical dimensions to scientific research and projects. Deeper collaborations could better explore the challenges and capitalise on the opportunities that emerge where communication is pervasive, ubiquitous and complex.

16.5 Real ‘citizen science’?

In liberal democratic societies, science enters the public sphere of debate with a menagerie of mitigating concessions and qualifications. Conservation ecology and science communication that seek to engage the public cannot be protected from these complexities: they are sine qua non to human societies. Communication between science and citizens in the twenty-first century is further impacted by the complex, interconnected network of communication technologies, practices and transnational flows characteristic of the modern experience. The public sphere that scientific knowledge enters is not a level playing field for all participants. Even ‘pure’ science messages are exposed to the unevenness wrought by conflict involving power, wealth, industry and politics.

Our Reef scientists and the scientific community are clearly attuned to the power of media in addressing environmental conflict and the public, hence the advertisement. We have questioned, however, whether such a blunt tool underpinned by a transmission model of communication is likely to result in the protection of the Reef intended by these scientists. We assert that messages, even those that seemingly carry the credibility and authority of scientific expertise, are confused and contorted by ‘communication noise’. This embeds science in the dirty politics of public sphere debate, rather than beyond the politics of knowledge, position and power. Early communication scholar John Dewey expressed these ideas at the turn of the twentieth century:

Society not only continues to exist by transmission, by communication, but it may be fairly said to exist in transmission, in communication. There is more than a verbal tie between the words common, community and communication. Men live in a community in virtue of the things they have in common; and communication is the way in which they come to possess things in common. What they must have in common in order to form a community or a society are aims, beliefs, aspirations, knowledge – a common understanding – like mindedness as the sociologists say. Such things cannot be passed physically from one thing to another like bricks; they cannot be shared as persons would share a pie by dividing it into physical pieces.

Opportunities are repeatedly missed and frustration grows in part because communication is assumed, and the scientists’ ‘camera’ faces out when what is needed is a science ‘selfie’ – a critical self-reflexivity capable of understanding not only the science but how science might be heard once it leaves the minds of experts and enters the community (Foxwell-Norton, Reference Foxwell-Norton2018). Understanding this requires ‘knowing thyself’ as a product of a peculiar set of historical circumstances that have legitimised and given authority to scientific messages but also as part of the politics of the public sphere – where citizens (including scientists) reside and knowledges circulate. Citizens must be the target of science messages in order to shift voting behaviour for a politics that gives due reference and regard to best conservation practice. This is clearly, from a communication perspective, the terrain upon which the Reef scientists are operating, albeit unconsciously. The core problem is that science communication understands itself, and largely gathers its authority and legitimacy, by defining its terrain in terms of ‘science’ rather than communication.

Science communication is very clear about the merits of bringing science to society, but is found wanting in the reverse, of the importance of bringing society to science. This is a tragic flaw, especially relevant at the current juncture when communication networks mean science is everywhere, visible and not, elevated and undermined, in every moment in society. As a starting point, there are a few key strategies that can begin to mitigate against the repetition of the ‘communication breakdowns’.

Improve scientists’ understanding of the ways in which their knowledges enter the public sphere of political debate and the politicised nature of their own knowledge.

Acknowledge that conservation science is understood by the public in terms mostly not answerable to, or cognisant of, scientific rigour or research.

Enter the arena of media-immersed environmental conflict willing to participate alongside and through other interests of politics and decision-making, including activist groups, industries and government.

Accept there can be no divorce of any aspect of conservation science from these politics, as it hampers meaningful engagement between science and its publics.

Take the ‘scientific selfie in society’ that shows the flaws, the unknowns and the occasional exhilaration.

A thorough and candid examination of the relations between citizens and scientists in a media-saturated society is, we suggest, extraordinarily hard science. It is, however, science that is critical to the development of new directions in the public communication of conservation science.

16.6 Acknowledgements

This chapter draws on research supported by the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Program (DP150103454 ‘Transnational Environmental Campaigns in the Australia-Asian Region’) and the Griffith Centre for Social and Cultural Research.

17.1 Introduction

This chapter examines campaigning: what it is, when it is needed and who conducts campaigns. Drawing upon examples from the NGO conservation sector, we discuss how to plan and execute a campaign, and explore the different types of campaign: behaviour change, policy change and fundraising. Finally, we consider some of the potential pitfalls, including a lack of a strong evidence base, overstating claims of success, the introduction of bias, conflicting views of co-organising partners, the inappropriate use of emotion and the risk of unintended consequences.

17.2 What is campaigning?

Campaigning, also described as influencing or advocacy, is about creating a change. Whether the aim is to reduce trade in the horn of a threatened species of rhino, protect the habitat of a rare population of wild orchids, raise funds for a workshop or the ongoing costs of species monitoring, or change the law on the import of hunting trophies into a country, conservation NGOs campaign to create change. The desired change may be to address the root cause of a conservation problem, such as demand-reduction or behaviour-change campaigns, or the campaign may be focused only on mitigating the effects of a problem, as in the case of grants to improve law enforcement activities that prosecute wildlife traffickers. Some organisations may decide to focus on campaigning to tackle both the cause and the effect.

17.3 When is campaigning appropriate?

Campaigning can be appropriate in a diverse range of situations: from local to global issues, from high-profile to emerging conservation problems, from long-term to opportunist responses. While campaigning is often on high-profile and well-known conservation problems, it may also be used to mobilise or harness existing public support for less well-known or emerging issues, or to tackle issues with impacts at a global scale.

In a recent opportunistic, but highly effective example, several NGOs launched campaigns to urge the public and policy-makers to phase out single-use plastics after the high-profile BBC documentary Blue Planet II, screened in the UK in December 2017, highlighted the problem of plastic pollution in the world’s oceans. The programme showed footage of a pilot whale cow carrying her dead calf for days, with the calf’s death linked to the possibility of its mother’s milk being poisoned with toxins accumulated through the food she had been eating. The combined messaging gained considerable public attention, and in April 2018 the UK Government launched a consultation to explore the possibilities of banning plastic straws and other single-use plastics. While this consultation follows on from other action to reduce plastic usage that took place before these campaigns, such as the introduction of charges for plastic bags in 2015, increased public pressure likely highlighted the issue as a priority at this time. Indeed, the then Environment Secretary Michael Gove reportedly stated that he had been moved by the BBC programme (Rawlinson, Reference Rawlinson2017). In addition, several large companies responded to pressure from consumers by pledging to reduce or phase out single-use plastics.

Campaigning can also be used to give a voice to those without one. NGOs focusing on humanitarian relief or disadvantaged groups of people will often tell the story of a single person as a microcosm of the wider issue. Conservation causes, whether endangered species or ecosystems, are not able to speak for themselves, and NGOs often use ‘ambassador’ animals, such as Sudan, the last male Northern white rhino (euthanised in March 2018 after experiencing an increasing number of age-related problems), which came to embody the long, sorry history of the doomed attempts to conserve the species. Sudan became the focus of numerous fundraising campaigns to generate income for assisted reproduction technologies to try to ‘recreate’ the subspecies.

Finally, campaigning is sometimes the only action possible, especially when the scale of the problem is large or cannot be addressed without state or international intervention (such as plastics in the ocean). One successful example took place in 2002, when campaigning by Project Seahorse played a central role in the listing of all seahorse species on Appendix II of the Convention on the International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), meaning that international seahorse trade was regulated and monitored for the first time (Project Seahorse, 2018). Through policy recommendations informed by scientific research, Project Seahorse highlighted the huge scale of trade in seahorses and the threat to wild species that unregulated and unsustainable trade was posing. With up to 20 million seahorses traded annually, this listing represented an important step towards sustainability of this trade.

17.4 Who campaigns?

Campaigns can be created and delivered by individuals, groups or organisations, whether commercial or charitable. NGOs are particularly associated with campaigning; their fundamental objective is to make the world a better place, and they have members who feel strongly about the issue in hand. NGOs are often very close to their service users and beneficiaries, and can therefore use evidence from their direct experience to highlight changes needed, whether to attitudes, legislation or budgets. The examples in this chapter are drawn from the conservation NGO sector.

A common cause can bring together disparate voices to create a collective campaign that is louder, more wide-reaching and more effective than could be achieved by any single organisation. The campaign to create a marine reserve around the Pitcairn Islands began in 2011, when the Pew Environment Group’s Global Ocean Legacy project first discussed with Pitcairn islanders the idea of establishing a large-scale marine reserve within their waters. A number of organisations and celebrities then became involved in the campaign, including the Great British Oceans Coalition, National Geographic, the Zoological Society of London, Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, Gillian Anderson, Julie Christie and Helena Bonham-Carter; the Pitcairn Island Marine Reserve was eventually legally designated in September 2016.

17.5 Planning a campaign

A well-designed campaign cycle will begin by analysing and selecting the issue, followed by developing the strategy, planning the campaign, delivering it, monitoring progress, evaluating impact and drawing out learning. More complex campaigns may research and develop different strategies and pilot them before conducting monitoring and evaluation on the different groups to determine the most effective strategy. They may begin by establishing an evidence base, developing a theory of change, and embedding within that the system of monitoring and evaluation, to include targets, indicators and means of verification.

Campaigns usually employ a call to action, which will differ depending on the target audience and the chosen goal. Such calls to action need to consider their target audiences. For example, a campaign to conserve water in Europe and the USA may ask people to turn off the tap while brushing their teeth, whereas a water conservation campaign in sub-Saharan Africa may ask farmers to introduce night-time drip irrigation for their crops to minimise evaporation.

If there is no budget previously set aside for the campaign, then funds need to be raised. Communications staff need to work on how to articulate the campaign’s concepts and frame the debate. Finally, the organisation needs to be ready to implement the change, perhaps in partnership with others, with all the resources required, and to be able to manage that implementation without detracting from its ongoing work.

17.6 Types of campaigns

Campaigns generally fall into three categories: bringing about behaviour change, bringing about policy change, or raising funds. We consider each of these in turn and, for each category, we give an example of a successful campaign, seeking to highlight the aspects that, in our view, contributed to that success.

17.6.1 Campaigning to change behaviour

Many campaigns aim to change human behaviour, to reduce the incidence of behaviour that is in some way harmful to wildlife or ecosystems, or promote positive behaviour. Changing behaviour is different to raising awareness of an issue, which involves simply communicating the nature of a threat or conservation problem in the hope that the public or policy-makers will take action. Increasingly, the effectiveness of raising awareness in changing a person’s behaviour is being questioned (Christiano & Neimand, Reference Christiano and Neimand2017).

Greenpeace’s palm oil campaign of 2010 (Greenpeace, 2010) targeted both the people buying Kit Kats and Nestlé, the manufacturer. A one-minute video shows a bored office worker shredding documents while watching the clock until 11:00 and his break. He tears open the wrapper of a Kit Kat. We, the viewer, see that the wafer finger is actually an orangutan’s finger, complete with furry knuckle and nail. The chocolate bar drips into his keyboard; oblivious, he wipes his mouth and spreads a smear of blood. The video ends with a call to ‘Stop Nestlé buying palm oil from companies that destroy the rainforests’. A link to Greenpeace’s website, with suggestions for how concerned viewers could take action, was provided. Greenpeace reported 1.5 million views of the advert, more than 200,000 emails and phone calls to Nestlé HQ and countless comments posted on Facebook. This, combined with protests at Nestlé AGM and its headquarters all over the world, and meetings between Greenpeace campaigners and Nestlé executives, resulted in swift action. Nestlé developed a plan to identify and remove any companies in their supply chain with links to deforestation so their products would have ‘no deforestation footprint’, although it has been reported that they have since backtracked on these commitments (Neslen, Reference Neslen2017).

In a contrasting example, campaigns to increase consumer awareness of the impact of their purchases on overfishing, including labels for certified sustainable products, have been found to have little effect on purchasing choice or consumer demand (Jacquet & Pauly, Reference Jacquet and Pauly2007). Therefore, it is essential that behaviour-change campaigns go beyond simple awareness-raising and base their messages on sound research into when, where, how, why and by whom the behaviour is occurring.

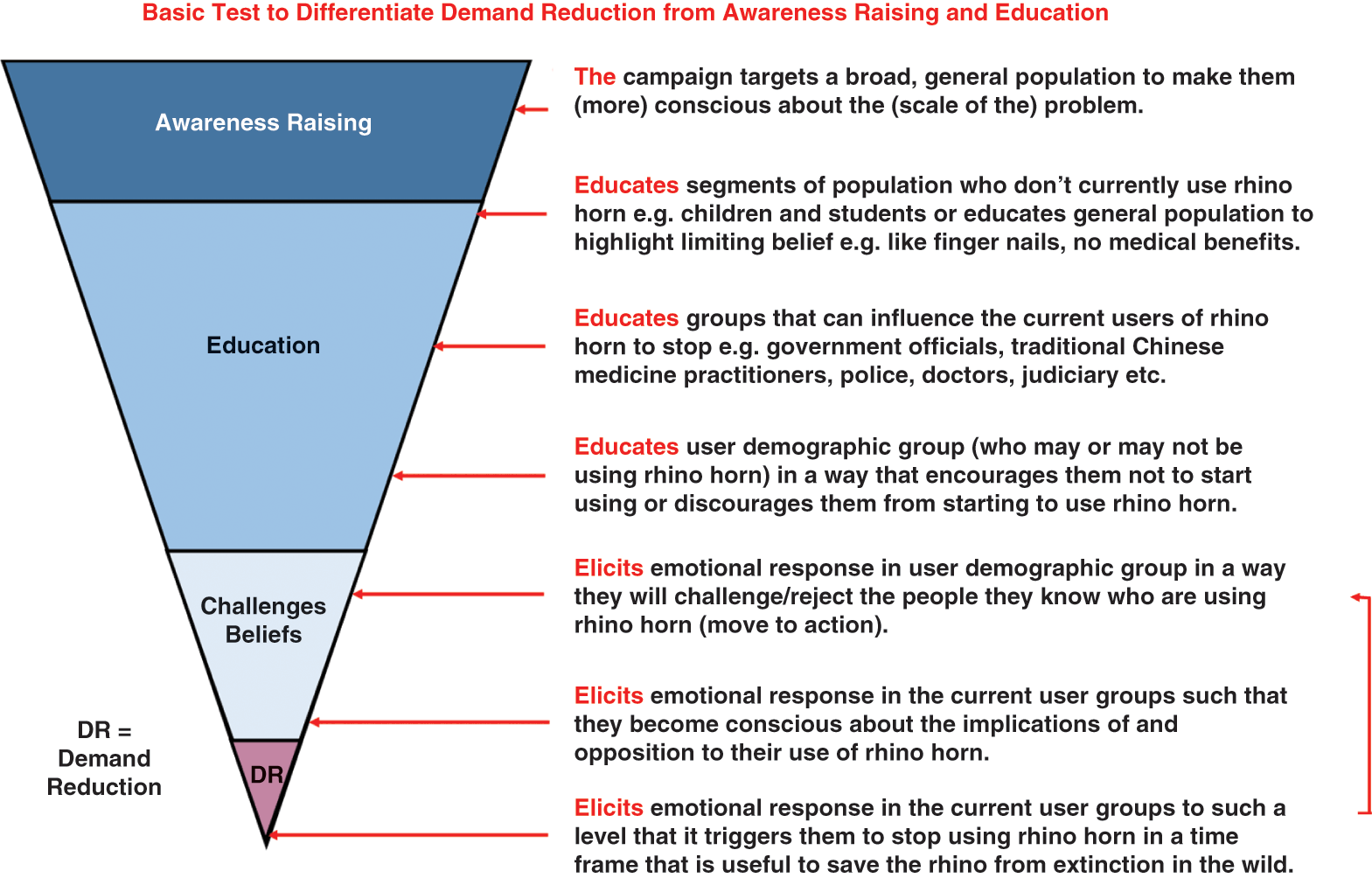

Lynn Johnson has developed a useful pyramid (Figure 17.1) to show the difference between behaviour-change and awareness-raising campaigns. However, the majority of so-called behaviour-change campaigns actually operate at the awareness-raising level, rather than that at the demand-reduction level. Programme managers dealing with the direct consequences of poaching understandably must feel frustrated when they see substantial funds being invested in ineffective efforts to change consumer behaviour in the main consumer countries for illegal wildlife products.

Figure 17.1 Model showing differences between behaviour-change and awareness-raising campaigns developed by Nature Needs More Ltd for its Breaking The Brand RhiNo Campaign.

Doug Mackenzie-Mohr (Reference Mackenzie-Mohr2011) has written extensively about fostering sustainable behaviours and has broken down the steps involved. The process starts by identifying which behaviour you want to change and in whom, while also considering when and where they exhibit this behaviour. The next step involves identifying what might be stopping people from changing behaviour, and what the incentives might be for doing so. This allows informed strategies to be developed that consider the design of the messaging but also other factors, such as how social norms can be used to reinforce the desired behaviour. These strategies should then be fully tested in a pilot phase before full-scale implementation, with monitoring and evaluation throughout.

Although behaviour-change campaigns focused on illegal products often suffer from a lack of available data on consumers, there are examples of targeted campaigns that have carefully planned their messages based on evidence. In 2014, TRAFFIC in Vietnam launched the Chi campaign, a behaviour-change campaign based on consumer research into the groups most likely to buy illegal rhino horn. This research established that the key driver for the consumption of rhino horn was its ‘emotional’ value rather than its ‘functional’ (i.e. medicinal) value and that the main users were wealthy businessmen aged between 35 and 50 living in Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City (TRAFFIC, 2013). They valued the strength and power of the animal that had been killed to obtain it, but also the scarcity and high cost of rhino horn and the difficulty of obtaining it; being able to do so demonstrated the extent of the buyer’s networks. Having segmented the consumer market, and with the information on the motivations of the prime target audience and the drivers of consumption, there was little point in launching a campaign that relied on photographs of traumatically dehorned rhinos, or on debunking beliefs that rhino horn could cleanse the body of toxins following chemotherapy. Instead, the campaign focused solely on the importance of ‘Chi’, an inner power and strength that negated the need for rhino horn. While it is too early to evaluate the success of this campaign, it is a good example of the careful designing and tailoring of messages to a specific situation that should be employed in campaigns of this type. Audience segmentation is a commonly used approach of subdividing populations into groups with shared characteristics, such as socio-demographic, behavioural or psychographic profiles (Wedel & Kamakura, 2000).

17.6.2 Campaigning to bring about policy change

When it comes to bringing about a change in policy, NGOs usually try to both influence and inform the target audience, who may be legislators or Members of Parliament. They may employ methods that include media campaigns, public speaking, commissioning and publishing research, online petitions (change.org and avaaz.org are two of the most popular English-language online petition websites), organising protest marches or demonstrations, recruiting advice from experts, or making direct approaches to legislators or Members of Parliament on the issue concerned.

In 2017, a group called Two Million Tusks was concerned about the plight of African elephants and the UK’s role in the global ivory trade. They researched the quantity of ivory being sold through UK auction houses and whether those auctioneers were compliant with the UK’s rules on ivory trade. The resulting report, published in October 2017, exposed weaknesses in auction houses’ compliance and called upon the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs to ban all trade in ivory within the UK (Two Million Tusks, 2017). While the debate about ivory sales has been long-fought, a linked television programme, presented by Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall, revealed new concerns. He arranged for eight ivory items on sale in UK antiques shops to be radiocarbon-dated, and found that three of the pieces were from modern, i.e. post-1947, ivory, and as such could not be legally sold in the UK. During a televised press briefing on this finding, the then Environment Minister, Andrea Leadsom, came under sustained pressure to address the UK’s role in laundering ivory from poached African elephants; the eventual result was a Bill to restrict severely the conditions under which ivory can be sold in the UK.

17.6.3 Campaigning to raise funds

Fundraising wisdom says that the most effective calls for donations are ones that engage the audience(s) on an emotional level (Hill, Reference Hill2010). Handling such messaging can be challenging: whether to use images that provoke negative (horror, disgust) or positive (empathy, inspired) emotions; whether to hold donors to ransom (‘Unless we act now, this species will go extinct’) or focus on success stories; whether to focus on a single, named animal as an ambassador for its species, while being clear that donations will be spent on a wide range of activities, or on a species or habitat as a whole.

In the UK, the Fundraising Regulator, formerly known as the Fundraising Standards Board, sets and maintains the standards for charitable fundraising in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, and aims to ensure that fundraising is respectful, open, honest and accountable to the public, and regulates fundraising practice via The Code of Fundraising Practice (Fundraising Regulator, 2016). Its guidance on ‘Content of Fundraising Communications’ says that organisations: must not imply that donations will be used for a specific purpose if they will be allocated to general funds; must be legal, decent, honest and truthful; must make it clear if they alter any elements of real-life case studies; and must give warnings about and be able to justify the use of any shocking images.

In October 2014, Save the Rhino International (SRI) began planning its annual fundraising appeal for 2015. The decision was made to focus on Kenya, which had not benefited from previous appeals and which had suffered a spike in rhino poaching in 2013, when 59 rhinos were killed, as compared to 29 the previous year. SRI had a long history of supporting rhino conservation efforts with its in-country partners. It was suggested that a focus on the canine units employed by Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, Borana Conservancy, Ol Jogi Conservancy and Ol Pejeta Conservancy, as part of their anti-poaching and community engagement strategies, would provide an interesting and engaging angle for a public fundraising appeal. These units use Belgian Malinois and bloodhounds for tracking (i.e. following poachers’ scent trails) and/or detection (i.e. dogs are trained on specific scents to be able to carry out, for example, vehicle searches at road blocks). A name for the appeal, ‘Rhino Dog Squad’, was chosen as being descriptive, punchy and memorable.

Based on results from previous appeals, SRI’s primary objective for the appeal was to raise a total £40,000 for the three canine units in Kenya by February 2016, of which £30,000 would come from a campaign marketed to the general public and £10,000 from zoos via spin-off campaigns.

Three distinct target audiences were identified: the general public/animal lovers, particularly those with pet dogs, living in the UK, continental Europe or the USA, across a broad age range, with some but not detailed knowledge of the rhino poaching crisis; high–net-worth individuals who have visited or have links with Kenya; and zoo visitors. Save the Rhino applied successfully to BBC Radio 4 to have the Rhino Dog Squad featured as one of the station’s charity appeals: this greatly increased the charity’s ‘reach’ to the first audience.

SRI’s appeal planning team realised early on that the choice of presenter would influence the script, and considered the merits of having a celebrity record the appeal versus one of the Kenyan field programme staff. In the event, SRI recruited Sam Taylor, Chief Conservation Officer at Borana, to read the script, giving SRI an opportunity to personalise the script. Furthermore, knowing that the appeal would be broadcast just before Christmas 2015 (twice on the last Sunday before Christmas and once on Christmas Eve) meant that the SRI team had to consider where radio listeners would be, and how to engage their emotions at such a time.

The BBC Radio 4 appeal alone raised more than £22,000, with the Rhino Dog Squad in total realising about £60,000 by 31 March 2016; some donors set up standing orders and funds are still being received for the canine units at the time of writing (June 2018). The BBC said that the appeal was one of the most successful of its type, and attributed this to:

a knowledgeable presenter: having someone who worked at one of the beneficiary conservancies read the appeal meant that it could be written in a way that was highly personal and credible;

an unusual script: the first words of the appeal were ‘Sausage bonus! Now there’s an image to conjure with. I’m guessing you don’t often see the words “Sausage bonus” in a budget. I do, in my work as Conservation Officer in a wildlife sanctuary in northern Kenya’. The first two words caught and held the attention, as Sam went on to explain how the canine units help the rangers with their work;

making the most of the timing: SRI knew that listeners would likely be at home with their families, wrapping presents, decorating the tree or beginning to cook Christmas meals. Contrasting listeners’ lives at Christmas with that of the rangers in Africa would be powerful. ‘This Christmas, as you enjoy time with your families, friends and your pets, please remember our dogs and rangers. They’ll be at work, protecting Africa’s wildlife. Please help the Rhino Dog Squad’;

the famous British love of dogs: ‘We use bloodhounds and Belgian Malinois, and they’re awesome. They can track scent for up to three days. They’re better than a bullet – they can go around trees and hold poachers until our rangers can safely make an arrest. The dogs work at roadblocks, detecting rhino horn, ivory, and weapons. We also use them to help find lost children or recover stolen property. Our dogs are part of our team’;

the wider appeal held by SRI: in addition to the BBC 4 appeal, SRI had planned a strong social media campaign with many assets: ezines, blogs written in advance ready to be posted, lots of high-quality images (including photographs taken during a visit in March of dogs tearing into parcels wrapped in Christmas paper containing bones and toys), and a main 4-minute film supported by four supplementary 2-minute films.

17.7 Potential pitfalls for campaigns

17.7.1 Lack of a strong evidence base

While reports of incredible successes offer good news stories for conservation and boost the reputation of the organisations that carry out the campaign, there is the risk that once the evidence base (where it exists) is questioned, the outcomes turn out to be not quite the success story that they initially appeared. Although in the majority of cases this may just lead to wasted donor funds and NGO time, there are also examples of where this has created a conservation problem in itself.

A good example is the ‘Save the Bay, Eat a Ray’ campaign that followed all of the rules for a good campaign. It used clear messaging to communicate a simple evidence-based action that members of the public could take to help restore Chesapeake Bay: eating more cownose rays (Rhinoptera bonasus) (National Aquarium Baltimore, 2016). The evidence said that a huge population increase of cownose rays was decimating the Bay’s oyster populations, and some also claimed that the species was invasive. However, further analysis of the science found that the models used were flawed and, not only was the ray a native species that was not responsible for the decline, it was itself extremely vulnerable to overfishing (Grubbs et al., Reference Grubbs, Carlson and Romine2016; National Aquarium Baltimore, 2016). In this case, a lack of robust scientific evidence relating to the ecology of the system led to negative conservation consequences, even if these outcomes were intended in the first place.

Behaviour-change campaigns can become particularly complex when they are based around reducing the use of illegal wildlife trade products. Communicating messages to the consumers of an illegal product is difficult because, if admitting to using the product could result in some kind of punishment, even identifying the consumers of it will be a challenge (see Chapter 5 for a discussion of approaches to gathering information about sensitive topics, including illegal resource use). Often, in-depth research focusing on consumer preferences and behaviour is needed to understand motivations for consumption (e.g. Nuno & St John, Reference Nuno and St John2015; Hinsley et al., Reference Hinsley, Verissimo and Roberts2015). However, behaviour-change campaigns are often carried out by NGOs without the time, expertise, resources or capacity to do this kind academic research. This has resulted in several campaigns based on very little knowledge of who the target audience should be, often using high-profile celebrities or eye-catching graphics to get the message out to as many people as possible, with the hope that this will include the actual consumers of the product. Unfortunately, it is not possible to say whether this works: a recent review found that almost no behaviour-change campaigns focused on wildlife consumers report evidence of impact, and very few carry out any kind of robust evaluation at all (Veríssimo & Wan, Reference Veríssimo and Wan2018). One way to address this could be greater collaboration between NGOs that do not have in-house scientists and academics, to ensure that campaigns are based on good scientific evidence, and that results are analysed in depth to evaluate the impact.

17.7.2 Over-stated claims of success

Some NGOs have focused their behaviour-change campaigns at children, banking on the ‘pester-power’ factor (cf. Figure 17.1, activity that ‘Educates segments of the population who don’t currently use rhino horn, e.g. children’). Humane Society International, for example, launched a campaign aimed at stopping the use of illegal rhino horn in Vietnam via a book called I’m a little Rhino that was used in schools to help teach children about rhino poaching concerns and conservation efforts. No information is available on how the campaign was designed, targeted or evaluated, but claims that demand for rhino horn had fallen by 77% in Hanoi following the campaign have been heavily criticised by conservation practitioners (Roberton, Reference Roberton2014).

17.7.3 Bias in campaigns

One of the dangers of advocacy/campaigning is that it may not be sufficiently inclusive or consultative. For example, the NGO leading the campaign may have a particular stance on a controversial issue, or an NGO with a direct line to a Member of Parliament or Minister may be able to exert undue influence.

For example, IFAW, Lion Aid and the Born Free Foundation, among others, have worked closely with a group called ‘MEPs for Wildlife’ (MEPs are Members of the European Parliament). While there was an initial focus on banning the hunting of canned lions (canned hunts are trophy hunts in which an animal is kept in a confined area, such as in a fenced-in area, increasing the likelihood of the hunter obtaining a kill), MEPs for Wildlife expanded its efforts to call for an EU-wide ban on the import of lion trophies, in keeping with decisions made by the Netherlands, French and Australian governments.

However, as an IUCN Briefing Paper for European decision-makers explains (with reference to the then recent and still notorious case of ‘Cecil the Lion’, shot in July 2015):

Intense scrutiny of hunting due to these bad examples has been associated with many confusions (and sometimes misinformation) about the nature of hunting, including:

None of these statements is correct. (IUCN, 2016)

The Briefing Paper goes on to conclude that ‘legal, well-regulated trophy hunting programmes can – and do – play an important role in delivering benefits for both wildlife conservation and for the livelihoods and wellbeing of indigenous and local communities living with wildlife’ (IUCN, 2016).

Making the case for positions, particularly ‘unpopular’ ones such as advocating for well-run trophy hunting, is extremely difficult to do. The IUCN Briefing Paper includes two graphs on rhinos and trophy hunting: the first showing the change in estimated numbers of Southern white rhino in South Africa before and after limited trophy hunting was introduced in 1968; and the second showing growth in estimated total numbers of black rhino in South Africa and Namibia before and after CITES approval of limited hunting quotas (a maximum of five animals per country per year, and even then only if suitable candidate animals can be identified) in 2004. Both graphs show populations increasing exponentially until the current poaching crisis began (IUCN, 2016).

Numerically speaking, the evidence in the Briefing Paper is conclusive: trophy hunting of rhinos, while fatal for the individuals concerned, has not adversely affected the species’ meta-population growth. Simultaneously, it has generated incentives for landowners (government, private individuals or communities) to conserve or restore rhinos on their land; and generated revenue for wildlife management and conservation, including anti-poaching activities. This does not hold sway, however, with NGOs that are ideologically opposed to trophy hunting.

17.7.4 Conflicting views

It would be wrong to assume that all conservation NGOs speak with a common voice. The Global March for Elephants and Rhinos (GMFER) has become a worldwide campaign, taking place in more than 160 cities in 2016, and thus enabling people from many different countries to take part. In the beginning, the march was about ‘raising awareness, generating global media attention on the crisis, and keeping political pressure on world leaders to protect our endangered wildlife’. Such broad aims made it possible for a broad church of elephant- and rhino-focused conservation organisations to take part in the march.

However, in more recent years, the GMFER has focused on banning trade in ivory and rhino horn, including applying pressure on South Africa to maintain a ban on domestic rhino horn trade (the ban was eventually overturned in early 2017) and on Japan and Hong Kong to ban online and domestic sales of ivory. A number of NGOs that are working to tackle the rhino and elephant poaching crises are actually pro-sustainable use, and have taken the decision not to participate in GMFER’s annual event, because its aims were incompatible with their own.

17.7.5 Inappropriate use of emotion

Conservation or animal welfare/animal rights NGOs must tread a fine line when campaigning about emotive subjects. Some of the most difficult images to view are those showing animal abuse or suffering, bushmeat and the impact of poaching. A photograph that is too upsetting will result in the viewer turning the page quickly without taking in the call to action.

There are ways around this challenge. Photographs of dead elephants with their tusks hacked out certainly tell the story behind the poaching crisis, but so too does Nick Brandt’s monochrome image, Line of rangers holding tusks killed at the hands of man, Amboseli 2011. As the photographer writes (Brandt, Reference Brandt2015),

I wish that I had never had to take this photo. I wish that it had never been possible to take this photo. The photo was taken as a deliberate visual echo of Elephants Walking Through Grass, a very different world – a vision of paradise and plenty – taken only a couple of miles away three years earlier. But instead of a herd of elephants striding across the grassy plains of Africa, we see only their remains: the tusks of 22 elephants killed at the hands of man within the Amboseli/Tsavo Ecosystem.

Brandt’s post goes on to hold out hope in the form of the work being done by Big Life Foundation’s rangers; a good example of a strong image, which does not in itself provoke feelings of disgust or revolt in the viewer (Fundraising Regulator, 2016), but which explains the catastrophe that has occurred and offers a way of helping to solve the problem.

17.7.6 Risk of unintended consequences

Ensuring that communications are well-designed and that the campaign’s main messages are evidence-based can make achieving the ultimate aim more likely, but it does not always protect against unintended, often negative, consequences of the campaign.

To date in conservation there has not been enough robust evaluation of campaigns to measure the occurrence of unintended consequences, but evidence from other fields demonstrates the risk. In the field of health, the risk of unintended consequences is well-recognised. For example, multiple studies have found that campaigns aimed at reducing drug and alcohol consumption frequently create so-called ‘boomerang effects’, where the result is an increase in consumption rather than a decrease (Ringold, Reference Ringold2002). This extent to which this phenomenon may be occurring in response to demand-reduction campaigns for high-profile wildlife products is unknown, but the complexity of these markets and the use of conflicting messages by different groups may increase the risk. For example, the legal bear bile trade in China has been the focus of extensive campaigns by animal welfare organisations, with the ultimate aim of closing down all bear farms. While some campaigns use the ineffectiveness of bear bile as a medicine as the key message, others instead focus on the cruelty of the farms, or the health risks to consumers of using farmed bile, such as the 2012 Healing without Harm campaign (Watts, Reference Watts2012). While these messages may be intended to close down the market for bear bile, and with it the farms themselves, little is known about how regular consumers of bile – who believe that it is an effective treatment for a serious condition, such as liver cirrhosis – will react. For example, will these consumers switch to wild-sourced bear bile instead where it is available, or will they start using another product? Currently there is little evidence either way, making this a risky strategy for conservation. To mitigate this, campaigns should fully consider all potential consequences of their messaging and evaluate the risks of carrying out the campaign before it starts, drawing on existing evidence from other fields.

Another problem area lies in the way that illegal wildlife trade products are described by some NGOs, which is then repeated in the media. Products such as orchids, pangolin scales and rhino horns are often described as rare and hard to obtain by well-meaning organisations or researchers. However, in markets that often prize rarity, such messages can increase consumers’ desire for the forbidden item, the acquisition of which will demonstrate both their wealth and their ability to use their networks to obtain it. For example, specialist consumers of slipper orchids, all species which are on CITES Appendix I, have been found to be willing to pay more for a rare species (Hinsley et al., Reference Hinsley, Verissimo and Roberts2015). Although several of these species have already been collected to near extinction for trade (e.g. Paphiopedilum canhii: Rankou & Averyanov, Reference Rankou and Averyanov2015), highlighting their rarity is likely to be counter-productive. Similarly, mentioning high prices for wildlife products can raise awareness of their value among both consumers and traders, and organisations like TRAFFIC and Wildlife Conservation Society have drawn up clear internal guidelines for their staff, explaining why they should never discuss the black-market price of an illegal wildlife product.

17.8 Future directions for campaigns in conservation

Campaigning to bring about change is central to much of conservation action, and it is essential that the importance of a well-designed campaign is recognised and appreciated. There are numerous examples of campaigns that have brought about change, many that did not achieve their intended goals, and even more that have never been carefully evaluated. As described in this chapter, the most successful campaigns will undertake careful planning and tailor their messages to the specific aim and context to ensure that they engage the target audience effectively. Other important steps include clear goal-setting, development of indicators and means of verification; monitoring, and a comprehensive evaluation of outcomes.

Competition for donor funds or the support of the public can sometimes mean that collaboration and open dialogue between different conservation actors is not always a priority. However, partnerships between different NGOs can extend the reach of a campaign and provide new perspectives, and collaboration with academics can provide a strong scientific research base for its design. Possibly the most important action should be to share lessons learned from successes and failures, as this is an important way that campaigns can continue to improve and avoid the pitfalls described here. These steps are essential, as a good campaign cannot only prevent the waste of donor funds, but increase the likelihood of conservation delivering change for the common good.

18.1 Introduction

Many of society’s ailments and ambitions, from obesity and corruption to economic growth and conflict, are ultimately about human behaviour. Sustainability and conservation challenges are no different, and although legal, economic and engineering solutions will be key, so will a shift in individual actions around resource use and waste, diet, fishing and agricultural practices, wildlife consumption, tourism and beyond (Rowson & Corner, Reference Rowson and Corner2015). Policy-makers, educators and conservation NGOs are therefore unavoidably in the business of behaviour change, but the conventional toolkit of regulation, incentives and information provision is increasingly being recognised as incomplete, and too rooted in a rudimentary model of human behaviour (Shafir, Reference Shafir2013).

On the rise is a more realistic understanding of behaviour, drawing on the latest insights from behavioural economics, social marketing and cognitive and social psychology. By harnessing these new tools we can radically improve policy and campaign outcomes and achieve greater social impact (Halpern, Reference Halpern2015). The field is rapidly growing in some parts of the sustainability community, as well as in public health, international development and consumer finance, but conservationists have so far been slow to embrace the behavioural perspective (Reddy et al., Reference Reddy, Montambault and Masuda2017). This is now beginning to change, particularly among NGOs faced with explicitly human challenges such as poaching, corruption, the illegal consumption of wildlife and common pool resource depletion, including water and coastal fisheries.

In this chapter I provide an overview of behavioural insights for sustainability and conservation, aimed at readers with little prior expertise in the subject. I do this by first reviewing a conventional understanding of behaviour change, discussing its shortcomings and then presenting some additional strategies.

18.2 A flawed starting point – rational choice

In both economics and psychology the dominant models of behaviour have historically been rooted in the concept of subjective expected utility, describing individuals as making rational choices that maximise the benefits to themselves (Scott, Reference Scott, Browning, Halcli and Webster2000) (see also Darnton, Reference Darnton2008, for a review of behaviour-change models). The axioms underlying these models are first that behaviour is cognisant and deliberate; second, that we are self-interested in the sense that we maximise our own utility as defined by our preferences, typically construed as wealth, enjoyment or subjective well-being; and finally that the locus of decision-making is the individual, implying a degree of indifference to context (Becker, Reference Becker1976).

In economics, this account of behaviour is formalised in standard micro and macro models, and has long provided the dominant intellectual framework for policy, regulation and law, business and finance, international development, public health and natural resource management. Indeed, the economic concept of cost–benefit analysis is highly analogous to this understanding of behaviour, implying we make choices by carefully trading off pros and cons. Among environmental campaigners and educators the language draws more from the field of psychology, speaking of values and attitudes rather than preferences and utility, but the assumptions of intentional, reasoned and individual choice are usually still implicit.

With this conventional model of behaviour in mind, a suite of tools for behaviour-change emerge, and capture the bulk of government and NGO activity.

1. Regulation. Influencing our behaviour through the threat of sanction via bans, quotas or standards.

2. Economic levers. Self-interest is harnessed by making pro-environmental behaviours the more appealing option, typically through the provision of economic incentives including taxes, subsidies, fines, grants, or payments for eco-services.

3. Social marketing and attitudinal campaigns. An attempt to alter our preferences, values or attitudes by promoting greater environmental concern.

4. Information provision. Assuming pro-environmental values to be present, people cannot act on them if they have flawed beliefs or lack awareness of the environmental impact of their choices. This information deficit may be overcome through education, awareness-raising, guidance, or product labels and kite marks. In practice, the line between ‘merely’ providing information and attempting to influence our attitudes is often blurred.

18.3 Going beyond conventional wisdom

A great deal has been achieved through the above approaches. In particular, regulation and economic incentives can be highly effective, reflecting the fact that self-interest is a powerful driver of behaviour. Information provision can also be effective if information deficit is a major barrier – product labels can have powerful effects in otherwise shrouded markets, for example. Raised awareness is also often a critical step towards building public consent for big-ticket policy initiatives, such as a carbon tax or the banning of wildlife products (Marteau, Reference Marteau2017; Portney et al., Reference Portney, Hannibal and Goldsmith2018). In and of itself, however, awareness is often not enough to shift individual behaviour due to the dominance of other factors, such as competing motivations or practical and psychological barriers to action (Barr, Reference Barr2004; Olander & Thøgersen, Reference Thøgersen2014).

The wider criticism is that these tools, and the behavioural assumptions underpinning them, overlook important aspects of human nature. I highlight three insights below as particularly in need of greater focus, before outlining some additional tools that emerge from these insights.

18.3.1 The importance of context

By focusing on the individual as the locus of behaviour, rational accounts of behaviour fail to recognise the extent to which our actions are shaped by the social, physical, economic, political and cultural context (Shove, Reference Shove2009). Indeed, evidence suggests that interventions that alter the setting in which choices are made, by making the desired behaviour cheap, convenient, politically cultivated and socially normative, are often more effective than those which focus solely on individual beliefs, attitudes and choices (Thøgersen, Reference Thøgersen2014). They do, however, require fundamentally different levers than conventional information-provision approaches often relied upon by conservation NGOs, targeting not the individual’s unsustainable choice, but the socio-technical structures which encourage unsustainable practices to flourish.

18.3.2 The importance of non-conscious processes

This sensitivity to context is best explained by dual-process models of cognition, which define two parallel systems of mental activity. One is slow, reflective, cognisant and deliberative. This system most resembles rational choice, although more accurately is boundedly rational, operating under limited information and cognitive bandwidth, and usually aiming to satisfice (find a good enough solution) rather than to optimise (Simon, Reference Simon1972). The second system, which dominates more of our decision-making than we tend to realise, is fast, largely automatic and driven by intuitive processes such as ingrained habit, emotion and heuristics (mental shortcuts) (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011).

These fast-and-frugal processes are mostly unreflective responses to cues in our social and physical environment, and hence our great susceptibility to external influence. They also leave us susceptible to predictable errors of judgement, or cognitive biases, as we trade-off accuracy for cognitive efficiency. For example ‘choose the middle option’, ‘stick with the default and the familiar unless there is a strong reason to risk the unknown’ and ‘do what most people like me appear to be doing’ are all heuristics we instinctively adopt – serving us well enough most of the time without demanding much mental resource, but often leading us to err from optimal decisions (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011). Designing environments, and campaigns, which reflect these more automatic processes can be an effective strategy for enabling and encouraging more sustainable behaviour (Thaler & Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008).

18.3.3 The importance of behaviour over values, attitudes and beliefs

Conservation campaigns typically attempt to raise awareness and elevate pro-environmental values, on the premise that greater concern for the planet, or a species or habitat, will drive financial support or more sustainable behaviour. However, it can be difficult to engage citizens in these issues. Research shows that pro-environmental information often has the intended impact only on those already sympathetic to the message, as we update our views asymmetrically, skewed towards the direction of our prior convictions (Sunstein et al., Reference Sunstein, Bobadilla-Suarez and Lazzaro2016). This observation is rooted in confirmation bias – our tendency to gravitate towards information which corroborates our existing views, while we discount, ignore or distort information which challenges us (Nickerson, Reference Nickerson1998).

That said, encouragingly, the battle for hearts and minds is slowly being won: pro-environmental attitudes are now common across much of Europe, for instance (Steentjes et al., Reference Steentjes, Pidgeon and Poortinga2017). This is helping to raise the policy agenda (Carrington, Reference Carrington2019). However, few citizens are independently giving up their cars, overseas holidays or beef burgers. It would also be naïve to expect fishers, farmers, poachers and loggers to compromise their livelihoods so willingly. Clearly, there is more to behaviour change than awareness and attitudes, highlighting the problem of a widely observed value–action gap (Kollmuss & Agyeman, Reference Kollmuss and Agyeman2002). The reasons for this gap are myriad and complex, although two broad categories are worth highlighting: insincerity of our values and barriers to acting on them.

First, pro-environmental values are frequently in tension with self-interest, creating cognitive dissonance and guilt for habits we are unwilling to forego. Guilt can be a powerful motivator for action, but we also have a tendency to resolve this dissonance not by curbing our unsustainable behaviour, but by ignoring the issue (wilful ignorance), or employing various acts of psychological fudging, including motivated reasoning (rationalising towards a convenient and ego-serving, rather than logical, conclusion), moral licensing (excusing ourselves the flight because we recycled) and biased social comparisons (inflated convictions that ‘I do more than most’ and deferring responsibility to government/industry/other countries) (Barkan et al., Reference Barkan, Ayal and Ariely2015). In other words, our behaviour reveals that our concern for cost, profit, convenience and enjoyment frequently outranks our concern for the planet, despite our ability to maintain sincere environmental values and a sense of integrity – the psychological equivalent of having our cake and eating it (Shalvi et al., Reference Shalvi, Gino and Barkan2015; Gino et al., Reference Gino, Norton and Weber2016).

Second, even where intentions are sincere, we may fail to act due to various psychological and practical barriers. These include hassle, a lack of options, lack of know-how, upfront cost barriers, lack of willpower, lack of self-efficacy (belief that we can make a worthwhile difference), procrastination, forgetfulness, ineffective planning, ingrained habit and various cognitive biases that favour a ‘do-nothing’ strategy, including loss aversion, present bias, uncertainty-aversion, inertia and risk-aversion. These factors constitute the second major element of the value–action gap (Webb & Sheeran, Reference Webb and Sheeran2006), and although they often seem trivial, they can be disproportionately impactful. They therefore deserve disproportionate attention when designing interventions and campaigns to help bridge the divide between good intentions and action. For example, helping people plan better to reduce food waste, removing the hassle of switching to a green energy tariff, providing easy substitutes to medicinal wildlife products, or providing timely reminders and tips for reducing water consumption are all strategies which can help turn green aspirations into green actions.

18.4 Effective strategies for promoting conservation behaviours