3.1 Everyday and Scientific Concepts

Concept formation was a central topic for Lev Vygotsky, a founding figure in the formation of cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT). In his classic Thinking and Speech, Vygotsky (1934/Reference Vygotsky, Rieber and Carton1987b) opened up an interactive and creative view of concept formation. Instead of authoritative concepts simply being handed down, Vygotsky described the process as a creative meeting between children’s spontaneous or everyday concepts developing bottom-up, and the scientific concepts taught in school instruction, moving top-down.

This insight meant the acknowledgment of the existence, interplay, and movement of qualitatively different kinds of concepts, an idea surprisingly absent in the theories discussed in Chapter 2. I will return to the limitations of Vygotsky’s notion of scientific concepts when I introduce the work of Davydov on concept formation.

3.2 Double Stimulation

For Vygotsky, the interplay between everyday and scientific concepts took place along a vertical dimension. Vygotsky did not address the issue of qualitatively different or colliding worldviews, perspectives, and positions in concept formation. Clearly such differences and clashes exist both among authoritative “scientific” concepts and among everyday concepts. This interplay between competing and complementary perspectives may be characterized as the horizontal dimension of concept formation.

With regard to the mechanism of concept formation, Vygotsky’s idea of double stimulation is of central importance. Double stimulation has been predominantly understood as a mediational method that can be used to enhance learning and problem-solving. In this view, the first stimulus is the problem posed to the learner, and the second stimulus is an artifact that the learner uses as a support in grasping and solving the problem, somewhat in the same way as the “material anchors” described by Hutchins (Reference Hutchins2005) are used to support various cognitive operations. But whereas Hutchins considers words as the weakest kind of material anchors, for Vygotsky words are the most important mediators: “Fundamental to the process of concept formation is the individual’s mastery of [one’s] own mental processes through the functional use of the word or sign.” (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky, Rieber and Carton1987b, p. 132).

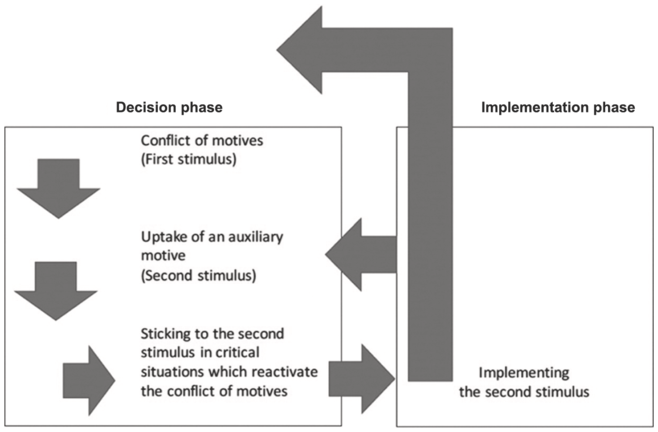

However, the principle of double stimulation had also a deeper meaning for Vygotsky. Double stimulation is a foundational mechanism behind the emergence of volitional action, will, and agency. This aspect of Vygotsky’s thinking has only recently been rediscovered by Sannino (Reference Sannino2015, Reference Sannino2016, Reference Sannino2020, Reference Sannino2022; Sannino & Laitinen, Reference Sannino and Laitinen2015) and modeled as shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Sannino’s (Reference Sannino2020, p. 169) model of transformative agency by double stimulation.

This work opens up the possibility of incorporating volition and agency as integral aspects into our understanding of concept formation in the wild. Concepts emerge as willful projections toward future action. Elaborating on his principle of double stimulation, Vygotsky (Reference Vygotsky and Rieber1997) referred to a waiting experiment, also called the experiment of the meaningless situation, as an example of human beings’ ability to agentively transform their circumstances. A subject is invited to participate in an experiment. The experimenter leaves the subject in a room without explanation and without a task. The experimenter observes from a separate room how the subject deals with the situation. This problematic situation itself is the first stimulus. It becomes a conflict of motives – to stay in the room or to leave. The subject hesitates, oscillating between the two options. The subject then looks at the clock on the wall and decides to leave when the hands of the clock reach a certain position. The clock thus functions as a second stimulus. When it is invested with meaning (“at a certain point I will leave”), it becomes a sign that enhances the will of the subject and allows breaking out of the paralyzing situation.

As demonstrated by Sannino (Reference Sannino2015, Reference Sannino2020, Reference Sannino2022; see Figure 3.1), in double stimulation the initial stimulus situation foundationally involves a conflict of motives. This gives a new meaning to the notion of tension put forward by Marková. The tension in double stimulation stems from a conflict of opposite motives. Volitional action and transformative agency emerge when human beings struggle to find a way out of the paralyzing conflict of motives.

The conflict is resolved by invoking a neutral artifact as a second or auxiliary stimulus. The clock in the waiting experiment is a good example. The artifact is turned into a mediating sign by investing it with meaning; for example, the clock is turned into a sign that marks the moment of departure. The true test of double stimulation takes place when the “real conflict of stimuli” occurs and it is time to actually take volitional action by means of the mediating sign. In such a process of double stimulation, the formation of transformative agency and the formation of concept go literally hand in hand. Double stimulation is essentially a process of reframing or reconceptualizing a pressing and paralyzing conflict of motives. The construction of a culturally novel concept takes place as an effort to resolve such a conflict of motives, emanating from contradictions within the activity system at hand. The emerging novel concept may in turn become a critical second stimulus in further efforts to resolve the conflict and reshape the activity.

3.3 Four Generations of Activity Theory

The development of activity theory may be understood as a succession of four generations of theorizing and research. Each of the generations developed its own prime unit of analysis. The first generation was embodied in Vygotsky’s work. Even though Vygotsky occasionally wrote about “systems of activity” (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky and Rieber1997, pp. 20–21), he never proposed or conceptualized activity as a basic unit of analysis. As pointed out by Zinchenko (Reference Zinchenko and Wertsch1985), for Vygotsky the prime unit of analysis was that of culturally mediated action.

It was Leont’ev (Reference Leont’ev1978, Reference Leont’ev1981) who worked out the second-generation unit of analysis, namely the concept of activity.

Activity is a molar, not an additive unit of the life of the physical, material subject. … In other words, activity is not a reaction and not a totality of reactions but a system that has structure, its own internal transitions and transformations, its own development.

Activity is a relatively durable system in which the division of labor separates different goal-oriented actions and combines them to serve a collective object. Object is what the activity is oriented toward. As the true motive of the collective activity, the object gives activity its identity and direction. The object is durable and constantly under construction; it generates a perspective for possible actions within the activity. As such, the object is not reducible to conscious goals; those are connected to discrete and relatively short-lived actions. The object of an activity is typically difficult to define for the participants.

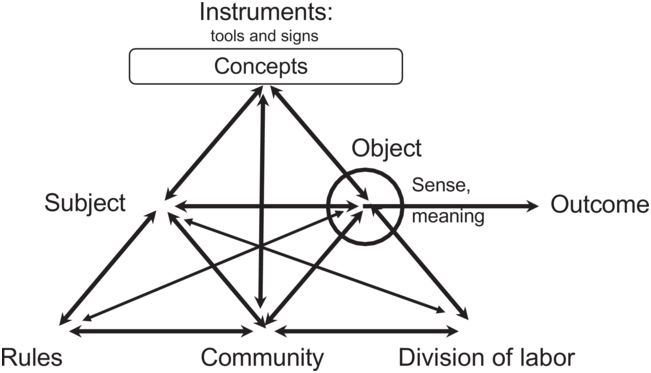

An activity system is more than a mechanical sum of its components. An activity weaves together its own dynamic context. In an activity system, concepts are a specific type of instrument, developed and used for grasping and representing aspects of the object and orienting actions toward it (Figure 3.2). When people transform and radically redefine their activity, they typically construct a new object and, at the same time, a new concept that captures the idea of the new object and guides efforts at its enactment.

Most concepts serve temporary and partial purposes in an activity system. We might call them action-level concepts, roughly corresponding to what Wartofsky (Reference Wartofsky1978) characterized as “secondary artifacts.” But there are also concepts that become durable orientation bases for the entire activity, or even for coalitions of multiple activity systems. We might call those activity-level concepts, again corresponding to Wartofsky’s “tertiary artifacts.” Such activity-level concepts may also be understood with the help of Leont’ev’s (Reference Leont’ev1978) notion of “motive–goal,” a merger of conscious goals of individual actions and the motive of the entire collective activity.

a different fate is created when the principal motive-goal is elevated to a truly human level and does not weaken man but merges his life with the life of people, with their good.

As activity systems are increasingly interconnected and interdependent, many recent studies take as their unit of analysis a constellation of two or more activity systems that have a partially shared object. Such interconnected activity systems may form a producer–client relationship, a partnership, a network, an alliance, or some other pattern of multi-activity collaboration. The formation of minimally two activity systems connected by a partially shared object may be regarded as the prime unit of analysis for third-generation activity theory.

Increasingly complex and fateful “runaway objects” with broad societal ramifications, such as climate change, homelessness, or pandemics, connect large numbers of activity systems across sectors, levels of policymaking, and national borders. Such objects tend to transcend and blur the boundaries between the history of a specific activity, the history of a singular society, and the history of humankind. The emerging fourth generation of activity theory zooms on heterogeneous activity coalitions aimed at resolving wicked societal problems, or runaway objects, and creating sustainable and equitable alternatives to capitalism (Engeström & Sannino, Reference Engeström and Sannino2021; Sannino, Reference Sannino2020).

The four generations of activity theory coexist and cross-fertilize one another. All of them see that human lives need to be understood as object-oriented activities, mediated by instruments, and changing through their inherent contradictions. Activity is to be understood in its constant development and transformations, making learning a central aspect of all activity. Transformative agency is of crucial importance in performing and shaping activities.

3.4 Ascending from the Abstract to the Concrete

Evald Il’enkov was the most important contemporary philosopher for the founders of activity theory. His analysis of the dialectics of the abstract and the concrete (Il’enkov, Reference Il’enkov1982) is of crucial importance for an activity-theoretical understanding of concept formation.Footnote 1 Il’enkov pointed out that in the prevalent formal-logical understanding of concepts

the term “concept” is taken to mean any verbally expressed “general”, any terminologically recorded abstraction from the sensually given multiformity, any notion of what is common to many objects of direct contemplation.

Il’enkov described the corresponding view of concept formation, characterizing it as “Robinson Crusoe epistemology.”

it is assumed that the individual first experiences isolated sensual impressions, then inductively abstracts something general from them, designates it by a word, then assumes an attitude of “reflection” towards this general, regarding his own mental actions and their products – “general ideas” (that is, general notions recorded in speech) – as a specific object of study.

In a dialectical view, concept formation begins from the concrete, understood not as isolated things but as the complex relations in which the subject is acting, as “a system of interacting things.” This concreteness initially appears to the subject “in some particular, fragmentary manifestation, that is, abstractly” (Il’enkov, Reference Il’enkov1982, p. 57). If our thinking merely reduces the sensually concrete into an abstract one-sided definition, it produces what Il’enkov calls “a general notion,” not a concept. To form a concept, we need to construct an abstraction that captures the origin of the phenomenon under scrutiny. A prime example of such an abstraction is the idea of commodity as the germ cell of capitalism, developed by Marx.

commodity is the kind of particular which simultaneously is a universal condition of the existence of the other particulars recorded in other categories. That is a particular entity whose whole specificity lies in being the universal and the abstract, that is, undeveloped, elementary, “cellular” formation, developing through contradictions immanently inherent in it into other, more complex and well-developed formations.

A fully developed concept is formed and manifests itself in the process of ascending from the abstract to the concrete. The initial abstraction, the germ cell, evolves into “the universal objective interconnection and interdependence of a mass of individual phenomena, ‘unity in diversity’, the unity of the distinct and the mutually opposed rather than an abstract identity, the abstract dead unity” (Il’enkov, Reference Il’enkov1982, p. 88). This unity in diversity is the foundation for understanding the horizontal dimension of concept formation: the struggle and negotiation between different and outright opposing perspectives and positions as a necessary aspect of concept formation.

One exists as such, as a given concretely defined object, exactly because and only because it is confronted by something different as concretely different from it – an object whose definitions are all diametrically opposed to those of the former object. … That is the only way in which concrete unity of opposites, concrete community, is expressed in a concept.

A germ cell abstraction is the starting point from which one ascends to the conceptually mastered concrete. The germ cell is “the genetic basis from the development of which all other, just as particular, phenomena of the given concrete system may be understood in their necessity” (Il’enkov, Reference Il’enkov1982, p. 76). But the germ cell is in itself also a real phenomenon that does not disappear with the emergence of its more complex manifestations. Simple commodities continue to exist even in our current era of extremely complex financial derivates.

the universal, which manifests itself precisely in the particularities, in the individual characteristics of all the components of the whole without exception, also exists in itself as a particular alongside other isolated individua derived from it.

From a dialectical perspective, a concept is a stepwise process of moving from the initial germ cell abstraction to its concrete manifestations. A concept is expressed in movement and action, not in fixed definitions. As Davydov emphasized, “every concept conceals a particular action with objects (or a system of such actions)” (Davydov, Reference Davydov1990, p. 299).

Every concept (if it is really a well-developed concept and not merely a verbally fixed general notion) is therefore a concrete abstraction, however contradictory that may sound from the standpoint of old logic.

The origin of concepts is to be found in productive labor, in the practical molding of materials into artifacts. In other words, concepts are pervasively present in all walks of life.

The concept (in its strict and precise sense) is not therefore a monopoly of scientific theoretical thought. Every man has a concept, rather than a general notion expressed in a term, about such things as table or chair, knife or matches. Everybody understands quite well … the role of these things in our lives …. In this case, the concept is present in the fullness of its definition, and every man consciously handles things in accordance with their concept, proving thereby that he has this concept.

However, for Il’enkov “everyday thinking is a very inconvenient object of logical analysis” (Il’enkov, Reference Il’enkov1982, p. 99).

It stands to reason that the universal laws of thought are the same both in the scientific and the so-called everyday thinking. But they are easier to discern in scientific thought for the same reason for which the universal laws of the development of the capitalist formation could be easier established, in mid-19th century, by the analysis of English capitalism rather than Russian or Italian.

Il’enkov’s argument may be valid from a logical standpoint. But a crucial issue for humanity today is how common people may conceptually grasp and practically act upon complex phenomena with potentially fateful implications and consequences. Practical work activities such as designing buildings or treating patients are dependent on forming shared, future-oriented concepts. The same is true of social movements. The separation of scientific thinking and practical everyday thinking is increasingly problematic. That is why concept formation in the wild is the focus of this book. Il’enkov’s work on concepts needs to be rediscovered and expanded on in this context.

3.5 Concept Formation as a Pedagogical Challenge

Davydov was a follower of Vygotsky. Above all, he was a student and practitioner of dialectics. In his groundbreaking work Types of Generalization in Instruction, Davydov (Reference Davydov1990) translated the principle of ascending from the abstract to the concrete into a dialectical theory of concept formation in processes of learning and instruction. This work owes much to Davydov’s close interaction with and learning from Il’enkov.

As I mentioned above, Vygotsky’s distinction between scientific and everyday concepts was problematic. Davydov pointed out the shortcomings of this distinction.

the determining difference between everyday concepts and scientific ones was found [by Vygotsky], not in their objective content, but in the method and ways of mastery (“personal experience,” “the process of instruction”). Some are without a system, others are given in a system. “Scientific concepts” are concepts specified in school.

But, as is known, empirical concepts also possess a certain system (e.g., in the realm of genus-type relationships). In school, particularly in the primary grades, it is exactly such concepts that are taught, on the whole. Of course, scientific concepts are given in a system – but in a particular system. It is this point, decisive on a logical level, that Vygotsky and his associates have overlooked. Therefore the genuine criterion for “scientific concepts” was not given in their works.

As a result, [Vygotsky’s] considerations to the effect that thought moves in a “pyramid of concepts” both from general to particular and from particular to general lose definiteness and unambiguousness. The point is that, in principle, this is allowable in a more or less systematized “pyramid” of empirical concepts. Mastery that starts from the “general,” from a verbal definition in itself, in no way characterizes the scientific nature of a concept – any everyday, empirical general conceptions can be specified in a similar way in instruction.

These critical observations of Vygotsky’s understanding of scientific concepts were grounded in Davydov’s carefully researched and rather devastating critique of predominant forms of school instruction. He concluded that schools typically nourish empirical thinking and the formation of empirical concepts, or abstract general notions to use Il’enkov’s expression, at the expense of dialectical thinking and theoretical concepts. To cultivate the formation of theoretical concepts, Davydov and his research groups constructed and implemented in practice alternative curricula for different school subjects, based on the principle of ascending from the abstract to the concrete (Davydov, Reference Davydov2008).

To overcome the dualistic separation of everyday and scientific concepts, one needs to build the study of concepts on careful examination of their origination and implementation in practical productive activity. In Types of Generalization in Instruction, Davydov wrote extensively on the practical origins of human thought, including theoretical thought (Davydov, Reference Davydov1990, pp. 232–258).

Theoretical thought also has an ancient origin. Its potential is included in the process of productive labor itself. It is a derivative of this object-oriented, practical activity and is always internally related to sensorially given reality. … Theoretical thought “snatches up” and idealizes the experimental aspect of production, first attaching to it the form of an object-sensory cognitive experiment, and then that of a mental experiment done in concept form and through a concept.

In Davydov’s theory of formation of theoretical concepts, the initial problem situation or task represents a diffuse sensory concreteness. It is manipulated and transformed – experimented with – to find its basic explanatory relationship or germ cell, which will be represented with the help of a model. These actions of transformation and modeling involve tracing the origin and genesis of the problem. The model itself is examined and used to generate and solve further problems. This enrichment and diversification of the abstract model leads to the ascending to the concrete, that is, to a conceptually mastered systemic concreteness that opens up possibilities for development and innovation.

Some scholars have interpreted this stance of radical pedagogical reform as yet another form of enlightenment thinking that privileges science as a superior form of human cognition.

We cannot fail to see that Davydov’s concept of the concept is imbued with a general outlook of the world that favors a certain form of knowability – the one that predominated throughout the twentieth century and considered scientific theoretical thought as the summit of human cognition.

Within this scientific outlook, law, measure, and calculation became the key concepts to understand the world.

I have to disagree with Radford. As I see it, Davydov was pursuing nothing less than a revolutionary transformation in school curricula and pedagogy. He did not emphasize the “scientific” as Vygotsky did – he emphasized the “theoretical,” which for him meant the “dialectical.” In my reading of and interactions with Davydov, I certainly never saw him emphasizing “calculation.” Instead, he repeatedly pointed out that you find powerful traces of dialectical-theoretical thinking in religions and in art, often more so than in the sciences. Although Davydov himself was focused on transforming school instruction, he actively followed and supported the work of Gromyko on “organizational activity games” (Gromyko, Reference Gromyko1997) as well as my own work on expansive learning in workplaces and communities.

Still, Radford has a point when he wants to go beyond a narrowly intellectualist understanding of concepts.

I prefer not to conceive of a concept as a mental rule, but as something more poetic, something that brings together the cultural rationality and worldview of the contexts where the object has emerged and evolved with all its historical and political tensions. In this view, a concept would be what we enact with others in joint activity – a cultural-historical enactive experience that is not merely conceptual and theoretical, but also esthetic, ethical, political, and emotional: something that questions us.

3.6 From Classroom into the Wild

Ascending from the abstract to the concrete is accomplished by means of epistemic and practical actions. In learning processes, we may call these learning actions. According to Davydov (Reference Davydov1988, p. 30), an ideal-typical sequence of learning activity consists of the following six learning actions: (1) transforming the conditions of the task in order to reveal the universal relationship of the object under study, (2) modeling the identified relationship in a material, graphic, or literal form, (3) transforming the model of the relationship in order to study its properties in their “pure guise,” (4) constructing a system of particular tasks that are resolved by a general mode, (5) monitoring the performance of the preceding actions, and (6) evaluating the assimilation of the general mode that results from resolving the given learning task. These learning actions are accomplished in different school subjects with the help of appropriate tasks.

In the 1980s, I started to work on the challenge of implementing ascending from the abstract to the concrete outside the school, in workplaces and organizations facing transformations that required the practitioners to reconceptualize and reorganize their activity. This resulted in the theory of expansive learning (Engeström, Reference Engeström1987, Reference Engeström2015; Engeström & Sannino, Reference Engeström and Sannino2010). Many of the ensuing intervention studies were conducted with medical practitioners and patients in health care organizations (Engeström, Reference Engeström2018).

The theory of expansive learning may be seen as an expansion of Davydov’s foundational work. An ideal-typical sequence of epistemic actions in an expansive learning process can be condensed as follows.

- The first action is that of questioning, criticizing, or rejecting some aspects of the accepted practice and existing wisdom. For the sake of simplicity, this action is called questioning.

- The second action is that of analyzing the situation. Analysis involves mental, discursive, or practical transformation of the situation in order to find out causes or explanatory mechanisms. Analysis evokes “why?” questions and explanatory principles. One type of analysis is historical-genetic; it seeks to explain the situation by tracing its origins and evolution. Another type of analysis is actual-empirical; it seeks to explain the situation by constructing a picture of its inner systemic relations.

- The third action is that of modeling the newly found explanatory relationship in some publicly observable and transmittable medium. This means constructing an explicit, simplified model of the new idea that explains and offers a solution to the problematic situation.

- The fourth action is that of examining the model, running, operating, and experimenting on it in order to fully grasp its dynamics, potentials, and limitations.

- The fifth action is that of implementing the model by means of practical applications, enrichments, and conceptual extensions.

- The sixth and seventh actions are those of reflecting on and evaluating the process and consolidating its outcomes into a new stable form of practice.

Together these actions form an open-ended expansive cycle. In practice, the learning actions do not follow one another in a neat order. There are loops of returning and repeating some actions, as well as gaps of omitting or stepping over some action. However, the basic shape and logic of the expansive cycle have been observed in many detailed studies of transformations (e.g., Foot, Reference Foot2001; Caldwell et al., Reference Caldwell, Krinsky, Brunila and Ranta2019; Triste et al., Reference Triste, Vandenabeele, Lauwers and Marchand2020) and interventions (e.g., Bal, Afacan, & Cakir, Reference Bal, Afacan and Cakir2018; Engeström, Rantavuori, & Kerosuo, Reference Engeström, Rantavuori and Kerosuo2013; Englund, Reference Englund2018; Mukute et al., Reference Mukute, Mudokwani, McAllister and Nyikahadzoi2018; Sannino, Engeström, & Lemos, Reference Sannino, Engeström and Lemos2016).

The actions of an expansive cycle bear a close resemblance to the six learning actions put forward by Davydov (Reference Davydov1988). Davydov’s theory is, however, oriented at learning activity within the confines of a classroom where the curricular contents are determined ahead of time by more knowledgeable adults. This probably explains why it does not contain the first action of critical questioning and rejection, and why the fifth and seventh actions, implementing and consolidating, are replaced by “constructing a system of particular tasks” and “evaluating” – actions that do not imply the construction of actual culturally novel practices.

Particularly the first learning action of questioning is of great importance. An expansive learning cycle begins with the learners facing troublesome indications that something is not going well in their activity and questioning what the problem is and where it comes from. In other words, the cycle begins with a conflict of motives that stems from contradictions in the activity system. The recent work of Sannino (Reference Sannino2020, Reference Sannino2022) on transformative agency by double stimulation (TADS) illuminates the critical role of conflicts of motives as the energizing starting point of expansive learning actions. Without facing a conflict of motives, learners can hardly engage in an expansive learning process. This of course means that ascending from the abstract to the concrete in the wild is a risky and often emotionally charged process that involves confronting and renegotiating power relations.

3.7 The Germ Cell

In ascending from the abstract to the concrete, the germ cell plays a crucial role. The following characteristics are essential qualities of a germ cell that may lead to an expansive theoretical concept:

- The germ cell is the smallest and simplest initial unit of a complex totality.

- It carries in itself the foundational contradiction of the complex whole, as well as the seeds for transcending and overcoming the contradiction.

- The germ cell is ubiquitous, so commonplace that it is often taken for granted and goes unnoticed.

- The germ cell opens up a perspective for multiple applications, extensions, and future developments.

- The germ cell is action-based and actionable; it typically exists and is enacted in practice before it is discovered, verbally articulated, and modeled.

The germ cell in itself is not the concept. It is the starting point and core of a theoretical concept. It embodies the driving tension that makes the concept develop. Commodity is the germ cell of capitalism. As a contradictory unity of use value and exchange value, each commodity carries in itself the driving tension that makes capitalism develop.

To illuminate the idea of a germ cell, I will briefly describe a study of the Herttoniemi Food Cooperative in Helsinki, Finland (Engeström, Brunila, & Rantavuori, Reference Engeström, Brunila, Rantavuori, Levant, Murakami and McSweeney2024). The cooperative was founded in 2011 and is located in the metropolitan area of Helsinki, Finland. The cooperative rented a field thirty kilometers from the center of Helsinki where a hired farmer produced vegetables for the cooperative. During the harvest season, vegetables were transported weekly from the field into the city to distribution points where members would come and pick up their share. In spite of its growing popularity, the continuity of the food cooperative was constantly at risk. Small-scale ecological farming is very labor-intensive and has to compete with the heavily subsidized industrial farm products of large food store chains.

The board of the food cooperative faced a reoccurring crisis with the financial sustainability of the cooperative. The standard solution thus far had been to organize annual drives to recruit new members whose membership fees would rescue the cooperative. When our fieldwork commenced, the board members of the cooperative were becoming increasingly uncomfortable with these repeated pressurized efforts to grow. A collective search for a new way out emerged. In 2015–2016, the researcher, Juhana Rantavuori, followed and recorded 27 successive board meetings in which the challenge and potential solutions were discussed. The data cover a learning process that lasted more than a year. Unlike previous macroscale studies of expansive learning, this study was not conducted ex post facto but by observing and recording the events in real time as they happened.

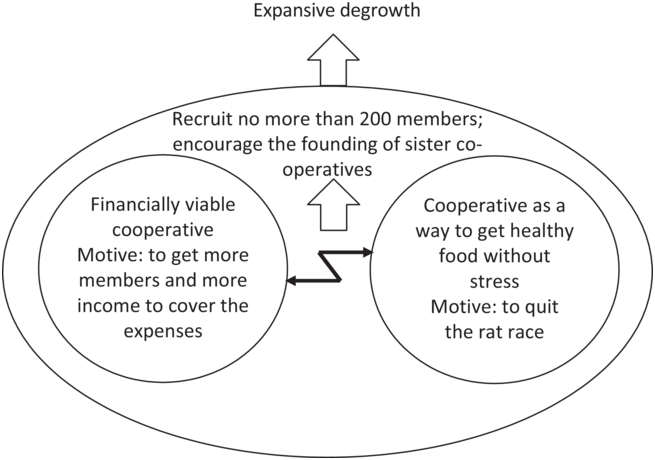

Over the 27 board meetings, the board generated a robust set of solutions to their pressing contradiction. Without going into the details, the main solution was to limit the number of members in the cooperative to 200 – a seemingly regressive decision that would stop the continuous and stressful quest for more members and more income. However, while putting a cap on its own growth, the board also decided to actively spread the idea of the food cooperative, aiming at the initiation and multiplication of similar cooperatives elsewhere. Thus, we may call the emerging concept of the cooperative “expansive degrowth.” It was degrowth in that it decisively withdrew from the self-perpetuating effort to increase the number of members and the amount of income. It was expansive in that it adopted the explicit aim of spreading and multiplying the model (for the concept of degrowth, see D’Alisa, Demaria, & Kallis, Reference D’Alisa, Demaria and Kallis2014; Latouche, Reference Latouche2009; Kallis et al., Reference Kallis, Kostakis, Lange, Muraca, Paulson and Schmelzer2018).

Figure 3.3 schematically depicts the internally contradictory germ cell that emerged in this case. The contradiction, typical of many enterprises in capitalist markets, was between the financial imperative “more members, more income” and the original idea of the cooperative as simply a way to get healthy food. The board members experienced this as a conflict between the motive to grow in order to cover the expenses and the motive to quit the rat race and produce healthy food without stress.

Figure 3.3 The germ cell in the case of the food cooperative.

The germ cell idea that transcended and resolved the conflict was crystallized in a critical action: “recruit no more than 200 members,” supported with a commitment to promote the founding of similar cooperatives around the country. Refusing to take more than 200 members was actually a deliberate non-action, similar to those discussed by Brook et al. (Reference Brook, Pedler, Abbott and Burgoyne2016). As this cap of 200 was set, a number of other, complementary solutions were connected to it, including reducing the workforce and reorganizing the work in the field, reducing the number of vegetable species and the field area, and bringing forward the annual rhythm of operations to reach a more anticipatory and proactive approach. The implementation of these and other related solutions represents ascending to the concrete in this case.

Although the germ cell was used to ascend to the concrete, the actual name “expansive degrowth” was not explicitly formulated by the participants. In other words, the emergent concept was practically enacted but only partially named and stabilized. This aspect of concept formation in the food cooperative will be examined in detail in Chapter 7.

3.8 Guiding Ideas for the Study of Concept Formation in the Wild

In Davydov’s theory of the formation of theoretical concepts, the initial problem situation or task represents a diffuse sensory concreteness. It is manipulated and transformed to find its basic explanatory relationship or germ cell, which will be represented with the help of a model. These actions of transformation and modeling involve tracing the origin and genesis of the problem. The model itself is examined and used to generate and solve further problems. This enrichment and diversification of the abstract model leads to the ascending to the concrete, that is, to a conceptually mastered systemic concreteness that opens up possibilities of development and innovation.

I will now sum up the basic points of departure gleaned from foundational sources of CHAT – Vygotsky, Leont’ev, Il’enkov, and Davydov – for the study of concept formation in the wild.

First, concept formation in the wild takes place in collective activity systems that evolve historically. Concepts serve as instruments for grasping the object and orienting actions toward it. Activity-level concepts can become durable guides for entire activity systems. In what ways are concepts actually used and how do they function in different activities?

Secondly, there are qualitatively different types of concepts. The identification of theoretical concepts is a foundational insight. However, the distinction between empirical and theoretical concepts may be an oversimplified dichotomy for understanding concept formation in the wild. What might be a more nuanced way to characterize different types of concepts in the wild?

Thirdly, theoretical concepts are formed by ascending from the abstract to the concrete. This dialectical procedure involves constructing a germ cell of the problem field to be mastered and using this germ cell to develop and understand a rich variety of consequences and concrete applications. How does ascending from the abstract to the concrete actually happen in the wild and how might it be supported? What complementary ways may be constructed to describe and analyze stepwise processes of concept formation in the wild?

Fourthly, concepts formed in the wild are inherently polyvalent, debated, and dynamic. Different stakeholders produce partially conflicting versions of the concept. Such “unity in diversity” is also an essential feature of theoretical concepts, as shown by Il’enkov. Thus, the formation of concepts in the wild involves confrontation, contestation, negotiation, and hybridization between different perspectives and positions. In which ways might clashes between positions and interpretations function as catalysts of concept formation?

Fifthly, concept formation in the wild is intertwined with the generation of TADS. Concepts inherently involve future-oriented intentions and they can become important second stimuli for agentive actions. How might concept formation and double stimulation be examined as intertwined processes within a unified analytical framework?

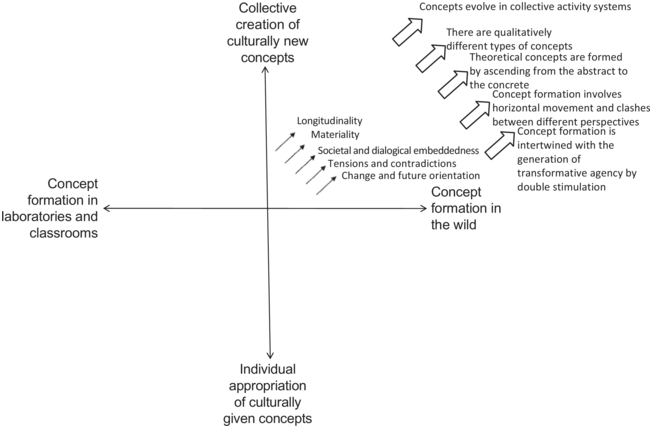

The five guiding ideas are depicted in Figure 3.4 as a second layer of lessons. These five guiding ideas are not easy recipes. They entail challenging questions that this book aims at answering.

Figure 3.4 Guiding ideas for the study of concept formation in the wild.

3.9 Formative Interventions

Ever since its inception, CHAT has been an interventionist approach devoted to and involved in efforts at changing people’s lives and advancing the common good (Sannino, Reference Sannino2011). Many of the empirical examples of concept formation discussed in this book stem from formative interventions conducted in workplaces and fields of work activity. Formative interventions differ from linear interventions in which the researcher knows ahead of time what the desired outcome should be (Engeström, Reference Engeström2011). In a formative intervention, practitioners (often including clients, patients, or pupils) tackle a critical transformation in their activity by analyzing the systemic contradictions that give rise to the transformation, and by designing a new model – and a new concept – for their activity.

Within the framework of CHAT, formative interventions are built on two epistemological and methodological principles (Engeström, Sannino, & Virkkunen, Reference Engeström, Sannino and Virkkunen2014), namely the principle of double stimulation and the principle of ascending from the abstract to the concrete – both discussed earlier in this chapter. The most well-known and widely used formative intervention method is the Change Laboratory (Engeström et al., Reference Engeström, Virkkunen, Helle, Pihlaja and Poikela1996; Sannino & Engeström, Reference Sannino and Engeström2017; Virkkunen & Newnham, Reference Virkkunen and Newnham2013). From the point of view of this book, we might say that Change Laboratories are laboratories of collective concept formation conducted in the wild. The wildness is in the facts that the interventionist-researchers do not know ahead of time the outcome of the Change Laboratory, and the participants commonly take control and change the course of the intervention (Engeström, Rantavuori, & Kerosuo, Reference Engeström, Rantavuori and Kerosuo2013). The laboratory-like character is in the facts that the intervention is carefully planned to generate the stepwise process of expansive learning, it systematically uses conceptual instruments of activity theory, and it is recorded for reflection and analysis.

The importance assigned to formative interventions is not unproblematic. It raises the issue of to which extent concept formation in the wild is an evolutionary process of adaptation and to which extent it is dependent on deliberate design efforts. I will return to this issue in Chapter 9.

3.10 From Dichotomy to Diversity

A theoretical concept is extremely practical in that it enables the production of creative solutions to a large variety of problems and tasks. Theoretical concepts are ways of understanding and acting in the world dialectically, of relating to objects and issues as historically developing and internally contradictory systems. Theoretical concepts allow us to identify possibilities and potentials even in threatening and oppressive phenomena – they are the core of possibility knowledge (Engeström, Reference Engeström2007a).

However, the boundary between theoretical and empirical concepts may not be so clear in the wild. The dichotomous distinction between empirical and theoretical concepts was made primarily to show that it is possible to cultivate genuine theoretical concepts in school instruction, not to account for the full diversity of concepts to be found in the wild. Chapter 4 is devoted to the examination of this diversity, with the aim of developing a workable typology of qualitatively different kinds of functional concepts.