Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Chronological List of Grimmelshausen's Works and Their First English Translation

- Introduction

- I Basics

- II Critical Approaches

- Engendering Social Order: From Costume Autobiography to Conversation Games in Grimmelshausen's Simpliciana

- The Poetics of Masquerade: Clothing and the Construction of Social, Religious, and Gender Identity in Grimmelshausen's Simplicissimus

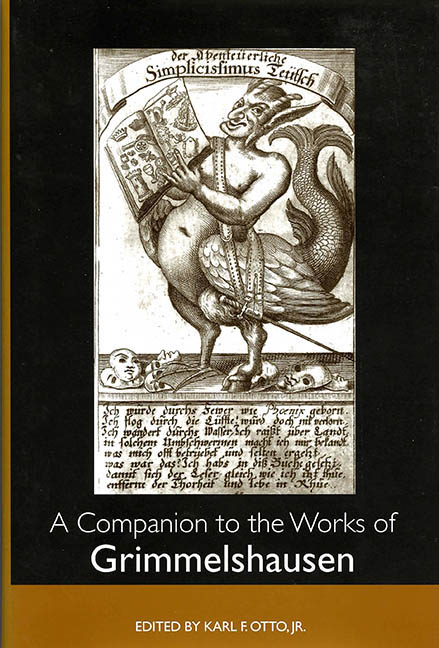

- “To see from these black lines”: The Mise en Livre of the Phoenix Copperplate and Other Grimmelshausen Illustrations

- The Search for Freedom: Grimmelshausen's Simplician Weltanschauung

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

The Search for Freedom: Grimmelshausen's Simplician Weltanschauung

from II - Critical Approaches

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 April 2017

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Chronological List of Grimmelshausen's Works and Their First English Translation

- Introduction

- I Basics

- II Critical Approaches

- Engendering Social Order: From Costume Autobiography to Conversation Games in Grimmelshausen's Simpliciana

- The Poetics of Masquerade: Clothing and the Construction of Social, Religious, and Gender Identity in Grimmelshausen's Simplicissimus

- “To see from these black lines”: The Mise en Livre of the Phoenix Copperplate and Other Grimmelshausen Illustrations

- The Search for Freedom: Grimmelshausen's Simplician Weltanschauung

- Notes on the Contributors

- Index

Summary

There is no such thing as Simplician ism. It would be quite feasible, if a little tiresome for both writer and reader, to distill from Grimmelshausen's writings a systematic account of his “thinking” on a wide variety of topics. There are treatises on social and governmental “policy” (Ratio Status [1670]), on language (Teutscher Michel [1672]), and on the acquisition of wealth (Rathstübel Plutonis [1672]. The Satyrischer Pilgram and the Verkehrte Welt (1672), the latter of which owes much to the Alsatian author of the Gesichte of Philander von Sittewaldt, Johann Michael Moscherosch (1601–1669), show him as a comprehensive and severe satirist of human frailty. The novels, in addition, range over most aspects of seventeenth-century life. Yet in creating such an account, we would run the risk of losing sight of what makes Grimmelshausen most accessible and precious to us. And that is his “Simplician” way of looking at, and finding freedom and humor in, a real world, which, like most of his contemporaries, he found something of a prisonhouse and vale of tears and yet at the same time infinitely fascinating. Our aim, therefore, is the evocation of an attitude rather than the definition of a philosophy.

The image of Grimmelshausen that emerged from the latter would be somewhat less exciting, probably, than his known biography might lead one to expect. His childhood, and education, had been rudely interrupted at age thirteen, by the sack of Gelnhausen after the Battle of Nördlingen. He had known, and shared, the “low life.” He had experienced his share of knocks, and even after he had pulled himself up by his bootstraps and re-assumed the aristocratic “von” that his bakergrandfather had felt inappropriate to his station, occupied a somewhat precarious position between the noble and moneyed and the “low” layers of society. Much of Baroque literature is courtly, in ethos if not literally in origin, but he could say with justice: “An grosser Herren Höffen bin ich zwar nicht sonderlich bekant” (VW 13). While he retained an understanding of the peasant's viewpoint, he was no revolutionary. He endorsed the “God-given” social order. He was a good, orthodox Catholic Christian, but no bigot. He was less than reverential, at times, to the Church's representatives, many of whom show a regrettable tendency to worldly deviousness and pride, and excessive confidence in their own spiritual authority.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- A Companion to the Works of Grimmelshausen , pp. 359 - 378Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2002