Walk the street with us into history. Get off the sidewalk.

As Chapter 9 argued, the kinds of changes that will be necessary to complete the transition away from fossil fuels in time to avoid the worst consequences of global heating are unlikely to take place without concerted government oversight and action, which in turn is unlikely to take place unless national decision makers are compelled to act by pressure from below. Although that pressure can take different forms, including advocacy by individual people and large nongovernmental organizations, the greatest impetus for significant change is likely to be grassroots collective action, which operates relatively free of elite or institutional control and derives its politics from the willingness to disrupt established institutional functions. As earlier chapters showed, action to cut emissions must reject false solutions and technofixes and focus instead on leaving the remaining fossil fuels in the ground and achieving a technical transition to renewable energy. While grassroots climate organizations have already offered several far-reaching proposals for achieving those goals and have had some notable successes in changing both public perceptions and institutional and governmental policies, the urgent need to accelerate confrontation and meaningful action across many levels of government and realms of society will require building a much broader and more powerful movement. This chapter explores strategies for growing and empowering such a movement, looking first at insights offered by the sociology of social movements and the psychology of collective action, then at the histories and tactics of three prominent grassroots climate groups in the Global North. Finally, the chapter turns to the various kinds of advocacy that can be undertaken by many more members of society more widely, recognizing that only a small proportion will join the grassroots.

Activating Grassroots Collective Action

As described earlier, the climate and environmental justice movement has been engaged in myriad struggles all over the world, some of which it has won. Just in late 2021, for instance, the Los Angeles County board of supervisors finally bowed to grassroots pressure and pledged to phase out all existing oil wells in the county; and the province of Quebec responded to the demands of a vigorous movement by declaring it would ban new oil and gas exploration.1 But despite such victories, the larger movement still seems far too small,2 considering the rapidly narrowing time frame within which serious emissions cuts must be achieved to prevent major disruptions in organized human existence. This section examines what lessons can be gained from research into social movements and the psychology of collective action about how to grow active participation in this movement.

Social Movement Theory

Social movement theory is an interdisciplinary field that explores the factors that influence the emergence, development, and effectiveness of social movements. Insights offered by practicing organizers and academics from the fields of history, sociology, and political science can help us better understand the main forms of organizing that activists may engage in, the different types of struggle they can wage, the varied ways in which they may frame the wider meaning of their struggle, and the locus at which social change is focused, each of which is considered in this section.

Forms of Organizing

Successful social movements vary their strategies for recruiting members and organizing their activities. Among researchers who have studied such movements, Mark and Paul Engler have identified three main approaches to such social organizing – community-based, mass mobilization, and momentum-based organizing – each of which offers different strategies for growing grassroots climate movements.3

Movements that follow the approach of community-based organizing (also called structure-based organizing), which was set out most famously in Saul Alinsky’s 1971 Rules for Radicals, tend to be pragmatic, nonpartisan, and ideologically diverse.4 As Alinsky noted, this approach is slow: “To build a powerful organization takes time. It is tedious, but that’s the way it is played – if you want to play and not just yell.”5 Such organizations are focused on goals defined from the bottom up so as to meet the immediate needs of the local community rather than high-profile national goals. Alinksy framed the goals of such organizing in terms of people’s self-interest (getting more local public transit) instead of lofty moral ideals, and he was suspicious of volunteer activists who were motivated by ideology. Alinksy’s framing is an important insight for today’s climate movements, which, as we will see, tend to be disproportionally made up of college students or middle-class professionals who are sometimes untethered from local communities. Despite being slow and requiring a long and constant local presence, community-based organizing also offers the advantages of being useful in building coalitions with other organizations and being more sustainable over time.

Another major approach to organizing, mass mobilization, utilizes the power of disruption by quickly drawing together a lot of people and leaving the establishment scrambling. As scholars Frances Fox Piven and Nelson Cloward have described, historical examples of this approach include actions by unemployed workers during the Great Depression, the industrial strikes that gave rise to unions in the 1930s, and the civil rights movement in the South in the 1950s and 1960s.6 An advantage of this approach is that it can come together quickly and makes it possible for people who have few resources and little regular political influence to attract attention and force change. While this method of quickly organizing on a large scale could be key in specific political battles over reducing greenhouse gas emissions, a disadvantage of this method for movements that want to have a lasting impact is that its energy can quickly dissipate unless it is accompanied by a sustained organizational structure.

A third type of approach is momentum-based organizing, a hybrid form that attempts to combine both the short-term explosive potential of disruptive action (to bring in more people and gain attention) with the benefits of a strong leadership and administrative structure to keep those participants engaged. While organizations may experience some tension between adherents of slow, structure-based organizing and advocates of quick mobilization, research and the histories of the climate change groups discussed later show that groups that practice both of these approaches together are likely to be most effective in achieving their intended goals.

Types of Struggle

Scholars such as the Englers have also identified two different types of struggle that social movements engage in. One type is a transactional struggle, which typically involves working toward concrete legislative and legal victories, such as pressuring the governor of California to stop issuing permits for new oil and fossil gas extraction or pressuring a city to adopt a policy to require all new buildings to run on electric power rather than fossil gas. In contrast, the goal of transformational struggle is to shift public opinion, often as a prelude to a later transactional win. The power of engaging in transformational struggle can be seen in numerous historical examples in which people with very few material resources managed to create change that many high officials considered absurd right up to the moment that those changes became seen as common sense. In the case of same-sex marriage, for instance, victories in state legislatures and courts and the eventual ruling in its favor by the US Supreme Court in 2015 reflected the end point of a person-by-person, family-by-family change of opinion that occurred over a decades-long struggle for LGBT rights.

As Figure 10.1 shows, achieving the transformational aims of a grassroots social movement requires shifting, or even pulling down, the specific pillars of support for the status quo that the movement hopes to change. These might include the media, business leaders, churches, labor, the civil service, the education establishment, and the courts. In one such example, the 2020 campaign to get the ten-campus University of California system to stop burning fossil fuels for heating and electric power generation focused on the pillars of students, staff, and faculty opinion, as well as the attitudes of campus and system administrators, including sustainability officers, chancellors, the president, and the board of regents.7 This campaign began with an energy petition that was signed by 3,500 staff, faculty, and students and supported by university unions representing 50,000 workers. Further organizing led to meetings with individual campus chancellors and sustainability officers, on-campus protests, op-eds in the media, and a social media presence. This emphasis on shifting the beliefs of key pillars of the university system, undertaken by a small group, produced some fairly rapid success: within a year, several of the ten campuses had allocated money to make plans to shift away from using fossil fuels, and the combined faculty were voting on a resolution to reduce on-campus fossil fuel combustion by 60 percent by 2030 and 95 percent by 2035.8

As such examples show, shifting the pillars of support requires a core of energized, active supporters engaged in collective action who are willing to show up at rallies, protests, and meetings, to persuade others around them, and to act independently wherever they are positioned in society so as to push against the pillars they are closest to. As impossible as it might seem to wage a struggle against formidable fossil fuel interests and their political and institutional allies, it is helpful to remember that the eventual victories against British colonialism in India, apartheid in South Africa, and lynching in the USA were in fact the culmination of a long line of events and pressures, many of which at the time appeared small and even unsuccessful.

Based on these prior social movements, it is important for participants in the climate movement to regard progress in the transformational struggle, as partial as it sometimes seems, as a win, which should be celebrated as such. Take, for example, the city of San Diego’s decision in early 2021 to approve a ten-year deal with the subsidiary of a fossil fuel company to continue providing electricity utility services, which on a transactional level was a resounding loss for the city’s climate movements. At the transformational level, however, the campaign was at least a partial win: the relentless campaigning by different climate groups led to a lot of media coverage and wider recognition among the city’s citizens of problems with the fossil fuel subsidiary and the need for publicly owned power providers, and the campaign efforts helped the local organizations build a coalition for future struggles. It can be highly motivating to climate activists to recognize that the process of attempting to achieve specific goals, even when not immediately successful at the transactional level, can help shift the pillars supporting the destructive status quo.

Frames of Meaning

As Paul and Mark Engler point out, transformational struggles often require a narrative about their moral significance. In the US South, for example, the Montgomery bus boycott in the 1950s began with a narrow demand for racial desegregation on city buses but soon became widely seen as part of a larger struggle for human dignity that energized its participants, attracted national attention and support, and provided moral legitimacy for its disruptive strategies. This additional element in the success of social movements is what social movement theorists such as Doug McAdam refer to as the frames they utilize: the shared meanings and cultural understandings that bind people together in a movement and create resonances among larger parts of the public.9

Specific frames that often motivate participation in social movements include shared feelings of grievance, threat, and anger, such as outrage at the poor treatment of animals, or, in the environmental case, the impact of fossil fuel extraction on the health of local communities. Larger master frames may also be shared across social movements, such as the notions of human rights or opposition to colonialism or globalization (such as the protests against the WTO mentioned in Chapter 4).10 The existing literature has shown that movements that create persuasive and coherent frames are more likely to be successful and to persist over time and that master frames can be especially useful for coalition building across movements.

As McAdam has noted, one problem facing the climate change movement is that for most people in the USA, the issue is not linked to a salient collective identity in the same way that, for example, the Me Too and Black Lives Matter movements have been to many people. With the exception of a few serious climate activists, McAdam argues, climate identity is not the most important issue in the lives of most people, for whom the salience of the climate issue varies over time in relation to many issues, including the economy, weather patterns, media coverage, and their material needs to provide for households. As a result, no substantial group “owns” the issue. To change this, he advises climate change organizers to find ways “to establish a clear, compelling connection between the issue and one or more highly salient identities, thereby conferring ownership of the issue to those groups.”11

One successful example of framing the climate issue to forge a stronger link to other salient identities has been the fossil fuel divestment movement on college campuses (which is discussed in more detail later in this chapter). Inspired in part by the earlier anti-apartheid boycott movement on US campuses, this movement has managed to link university community members’ identification with their institutions to concerns about how that institution’s money is invested in ways that impact climate change, thereby elevating the issue to an ethical and personal one.

Another attempt to connect the climate issue with identity is the environmental justice frame which tries to forge broader alliances between middle-class white environmentalists and people of color and Indigenous groups who are victims of environmental injustice, which arises from their exposure to toxic air pollution from fossil fuel infrastructure or from having oil pipelines built across their lands. Another current frame is the notion of a just transition, which, as Chapter 9 showed, tries to link climate and environmental struggles with workers’ rights and interests, especially among union workers within the fossil fuel industry, some of whom face the demise of coal and oil.

At a higher level, a master frame that has been employed by the climate movement is the notion of climate justice. As Chapter 8 showed, climate justice has rich resonances, encompassing the historical responsibility of different countries, the disproportionate emissions of a tiny global elite, the exposure of false technocratic solutions, and a shift away from the technicalities of cutting emissions toward a focus on the poor and marginalized people who bear the greatest climate impacts while having the least responsibility for emissions.12 While advocates see this master frame (of the ethical and political implications of climate change) as having enormous potential for motivating action, similar to a broad appeal to human rights, there are also potential problems. One problem is that the linkage of climate action with social justice sometimes encourages institutions to skirt the issue: for example, some institutions now go about addressing the climate concern with strategies to increase diversity and inclusion instead of dealing substantively with their ongoing burning of fossil fuels. Another problem is that the climate justice framing may not be inclusive enough. The broad political and social framework of effective action that was considered in Chapter 9 requires a politics of huge public investment, green urbanization, rewilding and afforestation, and a focus on human flourishing aside from growth per se. As the writer James Butler put it, “any such programme would need to garner the support not only of metropolitan liberals and the young, but to penetrate and revive the atrophied organisations of the old working class, to appeal ruthlessly to the desire of parents to hand on a better world to their children, and to recruit one pillar of the community for every activist or street prophet. It would need many more leaders and allies, interpreters and defenders at every level of culture.”13 This potentially broad alliance of which Butler speaks – which in the USA would include not only Indigenous peoples but also current and former fossil fuel industry, electrification, and other union workers, and presumably part of the wider white working class and college and high school students – certainly needs a master frame, but to date it is not yet clear what that is. A different argument for the climate justice frame to be more inclusive was made by Matt Huber in his book Climate Change as Class War. He faults the typical climate justice frame for making the problem too much about the source and impact of emissions (for instance, that the Global North caused the emissions, rich people exacerbate them, and the Global South and marginalized people experience the impacts) instead of focusing the struggle against the class that controls, owns, and profits from fossil fuel capital.14 He argues it is a mistake to assume that the real environmental struggle will only emerge from those with a direct material relationship to land and pollution (the Indigenous and marginalized), instead of appealing to working-class people who make up the vast majority of the population and who live from the market and not the land and who face little directly apparent environmental threat to their livelihoods. He suggests the electricity sector as a place where workers could organize to confront capital and to improve their material interests in a way that could also win climate policy.

Locus at which Social Change Is Focused

Although confronting fossil fuel interests and making the energy transition will require significant action at the national level in the USA, as discussed in Chapter 9, several aspects of the current political landscape present huge obstacles for a movement hoping to achieve goals through legislation, including partisanship, gridlock, and the influence of enormous amounts of money in US politics, particularly from fossil fuel and electric utility interests. A 2014 study of ninety-one climate change countermovements funded by conservative causes in the USA found that they had a combined annual budget of more than $900 million, dwarfing the funding of even the best-funded environmental action organizations,15 and contributions from fossil fuel interests have undoubtedly increased significantly since the Citizens United ruling allowed untold amounts of “dark money” to flow to politicians. The influence of fossil fuel interests has similarly held back the renewable energy transition in many other countries, including Canada, Australia, and Germany, and at the level of international negotiations. The UN Conference of the Parties 26 in Glasgow in 2021, for instance, was attended by more than 500 fossil fuel industry executives among the nations’ delegates, which exceeded the combined representation of all the Indigenous representatives from around the globe.16

Further, as Matto Mildenberger points out in his book-length analysis of energy policy in the USA, Norway, and Australia, the political problem facing the climate change movement is more complex than simply whether the governments in those countries are currently under the control of liberal or conservative parties, as carbon polluters have considerable influence within all major parties, including Republicans and Democrats in the USA, albeit somewhat less on the latter (Figure 10.2).17

Although none of this means it is pointless for grassroots social movements to try to influence national policy directly, the difficulties involved and the history of earlier social change efforts suggest that grassroots movements may need to focus most of their energy on the tried-and-trusted strategy of making local change first. Indeed, many successful attempts to create social change, such as the movement to legalize same-sex marriage or raise the minimum wage to $15, did begin locally and then spread to many states before becoming national policy.18 And the basic environmental laws that many take for granted in the USA didn’t come out of nowhere, they were issued by President Richard Nixon in the early 1970s. Yet Nixon, who was certainly no environmentalist but instead an incredibly cynical and conniving politician from the beginning to end of his career, ended up signing the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, and other environmental laws, only because he was compelled to by the political climate that arose from many years of mobilization at the local level, the passage of local anti-pollution measures throughout the country, and huge lawsuits against polluting corporations.19

Social Psychology Theory

Whereas social movement theory carries lessons for how to grow the grassroots movement at a group or social scale, the field of psychology carries lessons for how to motivate individuals. Specifically, it might help us understand why some people are more likely to enter into these movements and what strategies might make the movement more successful at attracting and retaining them. As discussed in Chapter 7, psychology research has shown that people with stronger perceptions of the risk of climate change have higher biospheric values, and these in turn are shaped in part by personality (especially openness at the aesthetic level) and early life experiences, such as role models and exposure to nature. Yet, beyond this, research in the specific area of social psychology, which deals with social effects on the individual, could reveal psychological variables that specifically affect the decision to join collective action.20 As some of these influences might be more modifiable than personality or early life experience, a better understanding of which variables are key could be useful for growing grassroots social movements

While many studies in social psychology have looked at collective action over several decades, they mostly focused on the anti-discrimination, anti-nuclear, and broader environmental movement rather than climate action, and the research was mostly based on survey reports about what people said they would do, or what they had done, rather than objective verification of their activist behavior.21 A 2008 meta-analysis of 182 such studies showed that two psychological variables – identity and efficacy – relate to self-reported engagement in collective action.22 The first of these, identity, comes in different forms: there is self-identity, which is the sum of all one’s attributes (e.g., father, musician, New Yorker), and collective identity, which is related to one’s sense of membership of a social group.23 When a group to which one belongs locates an external body, authority, or enemy that represents power and against which the group feels a grievance, that collective identity may become politicized. For example, although any group of women may develop a collective identity, once their identity as women becomes politicized they may become feminists.24 Having developed a politicized identity, the group may now choose to engage in collective action. The second variable identified by the meta-analysis is efficacy. This also comes in different forms: self-efficacy, which refers to an individual’s belief that they can accomplish whatever they want to and that they can use their skills to perform a behavior that will lead to a desired outcome,25 and collective efficacy, which refers to an individual group member’s belief about what the group can do, which could be summed up by the saying, “we can do this, people!” 26

Moving past the 2008 meta-analysis of 182 studies on collective action, more recent research, which included a focus on climate action, suggested the importance of additional psychological variables such as social norms (i.e., what the people around one are doing or one thinks they expect one to do) and participatory efficacy, which leads a group member to turn up for a climate rally or meeting with city officials because they believe that their participation is essential to the group’s effectiveness.27

Although there has been scant further psychological research on what drives people to join collective action specifically on the climate crisis,28 earlier chapters of this book strongly suggest additional variables beyond the biospheric values and open personality mentioned above, such as level of knowledge about the human cause and high threat perception.29 Other variables that are also likely to be important are one’s beliefs about how change is made. For example, someone who thinks climate action is relevant only for China to undertake (as the biggest current emitter) is less likely to want to take action in the USA, while someone who thinks climate action is the province of national policy will be less likely to act locally. Indeed, having a theory of change about the centrality of local action is probably a necessary criterion for joining grassroots action of any kind. So too, perhaps, is having the correct level of faith in institutions. As illustrated in Figure 10.3, too much faith may lead individuals to overly trust government and decision makers to make necessary change and therefore to not want to do anything themselves, whereas too little faith may make them too cynical or skeptical of the prospects for change to act. Instead, the “sweet spot” is probably an intermediate level of belief. This would be consistent, for instance, in believing that, based on its own history, the US Democratic Party is not by itself likely to produce serious climate policy, but is amenable to taking bold action if grassroots pressure grows strong enough (which was vindicated by passage of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022).

Although, as noted earlier, biospheric values arising from personality and early life experience are unlikely to be modifiable, many of these other psychological variables probably are modifiable. Understanding which to focus on, and how to boost them with educational interventions, is an important practical question facing social science, given the stakes for life on Earth and given how few sustained activists are currently organizing in the climate movements. What is needed is a research program that tests which specific psychological variables are causal to joining grassroots climate action, and also objectively verifies whether study participants did so. Figure 10.4 shows an example of a possible experimental design to increase the psychological factors underlying grassroots activism. Figure 10.5 provides an overview of all the psychological factors discussed in this section of the book

Examples of Climate Activist Movements

A better understanding of how to grow grassroots action can surely benefit from examining some of the main existing climate change groups to see what appears to have worked well and what does not. For that purpose, this section examines three of the most prominent such groups currently operating in the Global North: 350.org, Extinction Rebellion, and the Sunrise Movement. As it will show, these groups have taken quite different approaches, reflect different central features of social movements, and have received different sorts of criticism, as summarized in Table 10.1.

Table 10.1. Comparison of three grassroots social movements

350.org

The climate action organization 350.org was founded in 2007 by a group of students and the American environmentalist and author Bill McKibben.30 The name 350.org stands for 350 parts per million of CO2, which some scientists have identified as the safe upper limit to avoid disruptive climate impacts.31 Since then, 350.org has grown into an international organization whose goal is to help end the use of fossil fuels and hasten the transition to renewable energy by building a global grassroots movement. It has since mobilized thousands of people through the activities of multiple chapters in nearly 200 countries.

In what CNN called at the time “the most widespread day of political action in the planet’s history,”32 350.org mobilized people in 181 countries to come together ahead of the COP 15 meeting in Copenhagen in 2009 with a single message for world leaders: they must produce a fair, ambitious, and binding climate treaty to stay below 350 parts per million of CO2 in the atmosphere.

The group has initiated many campaigns but perhaps the best known, which started in 2012, was the fossil fuel divestment movement. The organizers argued that if the existing fossil fuel industry stockpiles of coal, gas, and oil were actually burned, we would blow through our remaining carbon budget five times over.33 The resulting campaign soon galvanized local groups at campuses across North America, and later more widely, to demand that their universities take their financial holdings out of fossil fuel stocks and bonds.34 To date, dozens of universities have claimed they have, or will, remove their investments from fossil fuel extraction, including the University of California, Oxford, Harvard, and Columbia, albeit the last two with such a late date, 2050, as to be practically meaningless.35 While these institutions have usually not framed their action in terms of the moral imperative of divestment, preferring to call it derisking,36 (which means they could in principle buy the stocks and bonds back when the financial risk changes), and while it is usually not possible to transparently verify their actions or to establish a bottom-line impact,37 the divestment movement has clearly had important effects. For example, it has focused the attention of hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of faculty, staff, and students on the need to leave fossil fuels in the ground, which is part of a transformational struggle that has also spread to other campaigns, such as those focused on state pensions, whose investments in fossil fuel extraction in California alone total over 80 billion.38 The fossil fuel divestment campaign has also brought a lot of people into the wider climate movement, including the youth organizers Sara Blazevic and Varshini Prakash, who went on to found the Sunrise Movement, and it led 350.org to develop a later campaign known as Stop the Money Pipeline, focused on banks and insurers. This new campaign noted that, since the Paris Accord in 2015, JP Morgan Chase had financed the fossil fuel industry by over $400 billion, with Bank of America, Citibank, Wells Fargo, and other banks not far behind (Figure 10.6).39 While these banks financed fracking, Arctic oil and gas exploration, coal mining, and tar sands oil, insurance companies, such as Liberty Mutual, were behind the Transmountain pipeline and other projects. So far, Chase responded to the campaign by taking the relatively minor step of announcing in February 2020 that it would stop financing new oil and gas drilling in the Arctic, but a more notable response, also in early 2020, was from the money manager BlackRock, which announced changes to its investment approach, including disclosing climate-related risks.

Thus, 350.org achieved international prominence and reach, which reflected its strong structure-based organization strategy. It developed dozens of chapters in the USA, some quite large, where it engaged in a mix of both transformational struggle, such as to shift attitudes and beliefs around the Stop the Money Pipeline campaign, and transactional struggle, such as partnering with other organizations to win local legislative changes by pressuring state officials to cancel new drilling. The frames it used were climate justice, environmental justice, and fossil fuel divestment as an ethical approach. Its theory of change appeared to be focused mostly on creating local shifts to undergird national policy later.

Members of 350.org have engaged in diverse actions, including civil disobedience outside Chase Bank locations, organizing marches, providing training, pressuring local congresspeople, engaging in outreach to students in high schools, and working with local cities to develop clean energy plans.40 This diversity of approaches is a strength in providing opportunities for different kinds of people to be involved. One possible weakness that limited 350.org’s growth potential was the perception that its volunteer base was mostly older, white, middle-class retirees, although, to be sure, those members were also hugely valued for providing a dedicated and sustained community-based substrate for further organizing, and meanwhile many chapters were making progress in diversity and inclusion.

Extinction Rebellion

An altogether quite different grassroots movement is Extinction Rebellion, which first burst into public awareness in London in October 2018, when it received major attention from the news media for blocking access to Parliament, for using music, dance, and elaborate costumes, and for adopting a mass arrest strategy.

The group was founded by a small number of activists with previous experience in climate and human rights organizing and the Occupy movement.41 The group adopted a highly confrontational direct action approach that followed a long tradition of transgressive environmental action, such as anti-nuclear protests, but was also novel and particularly effective in its emphasis on grief about ecological and human loss and its alarmism about the severity and speed of the crisis. As a result, the group was able to quickly mobilize tens of thousands of people, some for the first time, to take illegal disruptive protest actions, such as blocking bridges and roads.

The group’s approach was inspired by earlier transformative civil rights movements, such as those associated with Gandhi and Martin Luther King, and particularly influenced by co-founder and Kings College London researcher Roger Hallam’s studies of effective civil resistance against authoritarian regimes.42 Specifically, the mass arrests at the center of the group’s strategy were designed to overwhelm police resources, escalate costs, and fill up jail cells to create a level of disruption sufficient to force the government to take the climate crisis seriously.

In April 2019, Extinction Rebellion staged what it referred to as a second rebellion with actions at multiple sites in London and the wider UK, which led to more than a thousand “rebels” being arrested. As a result of these actions, discussion of the climate crisis penetrated many levels of civic society, media, and politics. The following month, Parliament declared a “climate emergency,” making it the first country to do so. In October, Extinction Rebellion launched what it termed an International Rebellion, staging actions in sixty countries, which in London included protests against institutions for their financing of the fossil fuel sector and a faux funeral march down a major London street that attracted about 20,000 participants.43

Thus, at least in its first two years, and centered mostly in London, Extinction Rebellion had a small core of structure-based organizers but also relied strongly on mass mobilization. Its goal for struggle was mostly transformational, raising awareness by using the frames of extinction and climate and ecological emergency, and its theory of change appeared to be to jolt political change through raising moral awareness.

Although Extinction Rebellion has clearly achieved its first stated goal, which was to force more people in the UK, and especially within the government, to tell the truth about the climate emergency, it has made much less progress toward its second goal of decarbonization or third goal of making changes to the democratic process via citizens’ assemblies. Although many institutions, cities, and countries across the world have now declared climate emergencies, such declarations do not themselves lead to genuine emissions reductions. Those disappointments experienced by Extinction Rebellion and some internal conflicts about strategy, control, and racial politics led to the splitting away of some of the founding members and internal reflection about strategies and tactics.

Specifically, some critics of Extinction Rebellion noted that the organization failed to attract large numbers of nonwhite participants and that it had not dealt with its class privilege; nor had it developed close contacts with the communities whose support it would need to become a mass movement,44 echoing a more general critique of most environmental organizations in the Global North, including the other two discussed here. Resolving this problem may perhaps require applying a more Alinsky-like approach to slow, structure-based organizing that centers a movement in the surrounding community of stakeholders. Another critique, made by journalist Nafeez Ahmed, was that its reliance on mass arrests directed at overwhelming the police represents a misreading of social science research.45 Ahmed argued that while the mass arrest strategy may have worked for the American Civil Rights Movement and Gandhi’s movement, it may be fundamentally out of place in the climate movement, as this model simply cannot be transplanted to the modern Western context, where the structures of power are much more complex, the repression much more invisible, and the institutions being targeted are only indirectly related to the problem being addressed.

As it emerged from the Covid-19 pandemic, Extinction Rebellion appeared to shift tactics by broadening its effects beyond the state to a focus on companies, banks, IT, agribusinesses, and the news media, such as disrupting the distribution of multiple newspapers owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp, the same organization that controls Fox News in the USA, in response to its failure to adequately report on the climate emergency.46 Indications were that Extinction Rebellion in the UK was attempting to increase its diversity and to link its struggles to class inequality: for example, as noted earlier, in 2021, it conducted an action that blockaded the private Farnborough Airport near London with signs declaring that “1% of people cause 50% of aviation emissions.” 47 Further, responding to the criticism that it was all about castigation and not about “solutions,” Extinction Rebellion launched the Insulate Britain campaign.48 Activists blocked motorways and planned repeated actions until arrest to draw attention to their demand for the government to make the investments to insulate housing, a very substantive way to reduce emissions through increased thermal efficiency, and also an equity issue that might draw in more people from the center and center right who were concerned about the cost of electricity and gas bills. In 2022, members of Extinction Rebellion also launched the campaign Just Stop Oil, which aimed to draw attention specifically to fossil fuel infrastructure, for example by trying to block trucks from oil terminals.49 In perhaps a sign that these tactics of blockade and civil disobedience were having an effect, the government proposed a repressive protest crackdown bill which would obligate the courts, which had often been sympathetic, to start jailing activists.50

Meanwhile, hundreds of Extinction Rebellion chapters have flourished around the world, from Paris to Lagos, from Delhi to Cape Town – indeed, Extinction Rebellion in Cape Town managed to temporarily, at least, stop Shell Oil from prospecting for fossil fuels off the South African coast.

Sunrise Movement

Unlike 350.org and Extinction Rebellion, which had an international dimension, and includes a wide range of ages, the Sunrise Movement has been tightly focused on electoral politics in the USA and is deliberately a youth movement.

Sunrise was launched in the USA in 2017 by students who got their start in climate change activism in the fossil fuel divestment movement on college campuses and in the pipeline protest movement.51 Its initial goal was to elect proponents of renewable energy in the 2018 midterm elections, when, indeed, half of the group’s first twenty endorsements won their elections.52 After that election, the group shifted its focus to gaining a consensus in the Democratic Party in support of the Green New Deal, a plan that, as discussed in Chapter 9, included the core principles of decarbonization, jobs, and justice. By late 2019, Sunrise leaders estimated that around 15,000 young people had shown up at in-person actions across the USA and 80,000 had participated in mailings and less direct actions.53

The tactics that have been used by Sunrise at the US capitol, state houses, and Democratic National Committee meetings are reminiscent of those of the civil rights movement of the 1960s: singing loudly, then standing quietly as officers tied their hands for arrest. Sunrise also mastered digital organizing, using the social media program Slack and Google documents to host digital field offices that have no walls and no set hours, which is easier for students and gig workers. Sunrise uses carefully crafted imagery and short and punchy videos, a striking example of which was a confrontation between middle-school students and Senator Diane Feinstein of California.54 Sunrise clearly understands well the impact of youth speaking to power, especially on the topic of intergenerational justice, emphasized by youth telling personal stories of how they feel and what they expect to experience.

In perhaps the most famous Sunrise action to date, in November 2018 members occupied the office of Nancy Pelosi, the top Democrat in Congress, and demanded that all members of the Democratic leadership refuse donations from the fossil fuel industry and that Pelosi herself work to build consensus in the Congress over Green New Deal legislation. About 250 members of Sunrise used their loud tactics to disrupt the office of the speaker of the house and persisted even after fifty-one were arrested. Within weeks, their ambitious demand for a Green New Deal was on the lips of every congressional staffer and progressive candidate for president in the country, and the HR-109 Green New Deal resolution was presented to Congress.55 By August 2020, President Biden had proposed a $2 trillion climate program that, although not called the Green New Deal, was the largest climate plan yet proposed by an administration.

Sunrise initially appeared to be stunningly successful in what it set out to do: a few thousand young supporters, distributed around the USA, were able to help make the climate crisis a central topic of discussion in the Democratic Party and to make it politically relevant. Part of this success may be attributable to Sunrise’s observing one of the key principles of good movement organizing discussed above: framing. As one of the founders, Varshini Prakash, observed, few people get excited about the topic of decarbonization in its own right, so she and her colleagues at Sunrise developed a vision for solving climate change through the creation of green jobs, which “are things people intuitively understand because they relate to their everyday lives.” Although “climate activists are always frustrated people don’t care about their issue,” she believed that “the real problem is we’re not listening to what people care about.”56

Thus, Sunrise soon achieved national prominence by reflecting a mix of structure-based organizing and explosive mobilization/protest: the momentum-based approach. Its original impetus was an openly transactional struggle to produce specific national policy outcomes, and it used the frames of intergenerational justice, the just transition, and the Green New Deal.

But by mid-2021, some critics had begun to point out that the group’s activities were having little impact on the few Democrat senators who were holding out on climate legislation, that media attention to Sunrise was generally waning, and that the kind of multiracial populism it was advocating was out of touch with the realities of the American body politic.57 These criticisms echo the broader critique leveled at the other groups discussed in this section: that if a grassroots climate change movement is to become successful, it will need to penetrate a much broader cross section of the population than its mostly middle-class, well-educated members from metropolitan areas. For all of these groups, becoming more effective is likely to require the development of a mass base of support around the country and across current class and racial divides.58 A possible remedy for the Sunrise Movement might be to shift its focus from influencing politicians directly to building mass support among working people, including fossil fuel workers and union workers, by helping them see the renewable energy transition as in their own best material interests.

All Together Now

Overall, 350.org, Extinction Rebellion, and the Sunrise Movement have achieved strong success in different ways but are still struggling to increase their numbers. Perhaps the common denominator for the future of all three is to find ways to make their climate and ecological struggle of interest beyond the relatively tiny number of environmentalists who have the class, race, and leisure-time privileges to engage in it. (See, for example, the comments of an expert organizer in Box 10.1.) This may require different kinds of framing and perhaps a renewed focus on community-based organizing among communities of color and union workers. Another very promising direction is coalition building with other organizations involved in climate, environmental, and social justice.59 One example was the formation of the San Diego Green New Deal Alliance during the Covid-19 pandemic in California in 2020. A big-tent alliance of more than sixty local organizations soon sprung up which was able to leverage substantial people power to shape climate policy at the city council and the regional transportation authority.

Box 10.1 Interview with Masada Disenhouse

Masada Disenhouse is a nonprofit administrator and program manager who for more than a decade has empowered people to organize, advocate, and campaign to build grassroots political power, most recently as executive director of SanDiego350.

AA: Can you trace what it was in your early life experiences that set you up to be a grassroots organizer, and specifically one so focused on the climate crisis?

MD: I feel like a lot of it just comes out of my personality. I have a strong sense of right and wrong and moral outrage. And I think I got that from my dad, who is also an organizing type personality. And then I think I got a real love of nature from my family, which used to camp and hike. I do not get my politics from my family, which is very conservative – I’ve always been very progressive. I started being an activist in high school. I distinctly remember reading the summary of the second IPCC report which had just come out, and I just couldn’t believe that there was this huge problem that nobody was talking about and seemingly nobody was doing anything about, and I was kind of freaked out by the whole thing.

Working on Ralph Nader’s Green Party presidential campaign in 2000, I really saw the value of long-term movement building versus short-term political campaigns. If you’re not doing long-term movement building between campaigns, you don’t have a base to draw from. It showed me that if you want to get people civically engaged, you need to create the structures and the resources that let people plug in when they’re available and for the small amounts of time that they’re available. It’s not just about climate – I developed a passion for helping people understand that they do have political power and how to use it on any issue that they might be interested in.

AA: When some students in my university get their eyes on the climate and ecological crisis, they want to do something about it. But they often say they don’t know what to do. What are your recommendations for people just starting to get involved in the climate movement? As an organizer, how do you match individual people with what they can do?

MD: Start by talking to everybody you know about why you care about this issue and what you’re personally doing about it. Movement building is related to how much people get the word out and how much you convince regular people that this is an important issue, that it’s a problem that affects them, and that something needs to be done. Everybody needs to realize that they’re an influencer. Whether it’s on social media or talking to people in person, everybody has their own networks. My Step 2 is always going to be joining a group. In this country, unless you are a rock star or have a ton of money, pretty much the only avenue that’s left to you for exercising serious political power is through organizing, and that means working with other people in some sort of structure. So I really recommend joining a group and learning how you can contribute. For it to be sustainable, for you to continue to contribute to that cause, you must do work that’s meaningful and rewarding for you. There are a lot of different ways that people can contribute. You don’t have to do everything.

About how to match people, the role of the organizer is to talk to people and find out where their passion is and what they like to do. I like to listen, then make some suggestions of things to try out, so they see if it’s a good fit. I also do like to push people to try things out of their comfort zone. I think that current political power in this country relies a lot on people accepting the status quo, and there are a lot of social norms around what’s acceptable and what’s not and how to engage as an activist and advocate, and change doesn’t happen without disrupting those norms.

AA: Your organizing work is mostly at the local, regional, and state levels. Yet we need a huge energy shift, ideally driven by national policy. How does your local work connect with the national and international levels? How do you motivate someone new to join the grassroots when the changes that are needed are so much bigger than what we can accomplish locally?

MD: First of all, I think that the local matters a lot because it’s where you have the most influence, right? It’s where you understand how politics works. Getting things done in cities and regional agencies like SANDAG [San Diego County’s transportation agency] is where we can build power and really affect things. Also, accomplishments in a city can serve as a model. For example, San Diego passed one of the most aggressive and accountable climate action plans back in 2015. It was one of the few big city models that were available at that time, so it had a far-reaching impact on other cities. I also think belonging to a network is important. My local organization is affiliated with the national and international organization 350.org, and we also build relationships with lots of other local organizations. Having those networks is really important, so that occasionally you can bring everybody together and bring all that power to bear on something specific. For example, we’ve participated in big days of action, where people show power in the streets. You can get lots of people to sign petitions or make phone calls, you can get a significant number of people from each area to participate in key moments, like the Keystone XL protest at the White House or the Dakota access pipeline protests. I also think that sharing information and resources across networks is very important, so everybody doesn’t have to reinvent the wheel. Just look at the Black Lives Matter movement this last year. People turned out in their own city, and some were able to get changes to the policy in their own city, but you can see that the whole nation shifted on this issue, and similarly on other issues. I like to give the example of same-sex marriage. It went from being something that was unthinkable when I was in high school, a hot-button issue that nobody would talk about, to something that successfully passed, and is now completely supported by a lot more than 50 percent of the people in this country. Within a generation, not a long time. And the reason it became so acceptable was mostly because people decided that they were going to go and talk to their families, right? It’s hard to tell someone you don’t know about the right to same-sex marriage, but it’s a lot easier when you’re a sibling or a child. I think that can be really powerful. And I think it goes back to the relevance of working locally. If we all push in the same direction, we can achieve that national-level shift.

AA: What role does money play in your grassroots work? Can you define grassroots? Do you need more funding, and what would you do with it? At what point might your approach be compromised by (large) sources of money?

MD: Grassroots organizing is all about having accountability to the community that you work in and being driven by the people in that community as opposed to top down. Our organization is very volunteer-led. We have about twenty different volunteer-led teams and decisions are mostly made by the people in the teams, as long as what they’re doing is consistent with our mission. And we bring team representatives together to make organizational decisions. In terms of money, I would say that, yes, it’s very helpful for getting things done. It’s really important that most of our money comes from individuals, though some of it comes from individuals who have a lot of money and give us a good chunk of money, and we definitely try to stay in their good graces. In the non-profit universe there are grants, but there are very few foundations who will give money toward disruptive political work. So organizations that rely on grants often do end up being influenced by that, and that’s one of the reasons that we really value donations from individuals, because it gives us the freedom to be disruptive. The funds primarily allow us to provide the structure that enables a lot more people to get involved. Our staff make sure that there’s onboarding and follow-up for new people, that we have tech, and we provide training and mentorship to volunteers as they’re developing their skills. So I think you can ideally balance your independence and commitment to grassroots organizing with being able to raise the money to support that work. I think a lot of people were inspired by Senator Sanders’ campaign, which was able to raise a lot of money from small donations and that’s the model that we use.

AA: To go up against the fossil fuel industry, we need massive political power and the largest grassroots big-tent movement possible. What are some of the factions or divisions in the climate movement? How do you join forces with progressive allies whose focus isn’t climate change? How do you determine who to ally with? What can we do to ensure we’re all pushing in the same direction?

MD: Well, first of all, I would say, if I knew all the answers to this, I would probably win the Nobel Prize! There are legitimate differences of opinion about what is politically viable, and I think in every movement, one of the classic divisions is between people who want to do incremental work versus people who are more radical and push for the full changes that are needed, and there’s a lot of friction that’s caused by that. But I don’t think there’s an easy solution. As an example, within the climate movement, there is the Citizens’ Climate Lobby and they’ve put forward a bill for a carbon tax that gets paid back as a dividend. This is an incredibly incremental, and I would say, conservative-leaning approach. And then, on the other side, I have a friend who was one of the valve turners. They identified the five pipelines that transport oil between Canada and the US, and they went out one day and cut the bolts on the fences and turned off those valves. So there are a lot of narratives out there. I’m going to sound like a broken record, but it really comes back to how do you shift the narrative? You need the wider public to be outraged by it and think of it like a moral justice issue that they need to pay attention to. We haven’t gotten there on climate, not yet. You know, I think of our local work at the city council. On the one hand, it will give us a climate action plan and at the same time, it will shift the way people think about the issue. You’re trying to accomplish both at the same time. And I think if people in the wider movement agree on shifting the narrative then they are allies, rather than people to be fought.

I also believe that we need to escalate, to disrupt things and bring pressure to get people to see that moral outrage, so I wouldn’t make any apologies about that. And something else is trigger points that suddenly raise massive public awareness and concern, like the murder of George Floyd. That was one of those moments that made people focus and come out in a way that they had never come out before. You can’t predict when those triggers will occur, but you can get ready for them.

You also asked me about who to work with outside of climate groups. I would just say that, first of all, the most important thing to know is that environmentalists are too small a percentage right now to win anything on our own. So we have no choice but to go out and partner with people whose main issue is something else. And I think we have some natural allies, since climate is clearly a justice issue. Lower-income people and communities of color are way more impacted by climate and way less able to deal with the pollution that’s caused by drilling for and burning oil and gas. So I think social justice groups are kind of a natural ally for us on this. And we’ve worked with labor, housing groups, faith groups, and others. I think it’s really about broadening that coalition. The other benefit is familiarizing other people with your issues. I would partner with anybody pretty much as long as I feel like we can get to common ground. Partnering means having a genuinely reciprocal and respectful relationship.

AA: I want to follow up on the labor issue. Some have said that the unions are not with the shift to renewable energy.

MD: I think that the reality is that there are a lot of legitimate concerns by people in labor. For one thing, I’ll say that labor has gotten the short end of the stick on politics a lot in the last several decades. There’s been a concerted attack on labor since before I was born, and union memberships have gone down tremendously. And I think that one thing to recognize is that labor has on the whole been playing a very defensive game for a very long time now, and they are very vested into hanging on to what they have. And that’s legitimate, they’ve been attacked. Another issue is that there is little overlap between the people in the environmental movement and unions. Environmentalists tend to be more professional and often misunderstand what the unions are for and how they work. The main job of the union, really, is to look after their members, to make sure that they’re getting treated fairly and paid reasonable wages and benefits. To underestimate the value of unions is a mistake. There are a lot of people in this country who don’t get paid enough to live on, who have to work multiple jobs, who don’t have child-care, who don’t have health care, who don’t have sick pay. Workers in this country, unionized or not, have been attacked for a long time. And if we’re serious about justice and equity, we have to support unions and collective bargaining.

The unions are looking out for people now, so they may say no to things that are a long-term opportunity. For example, you might say to them, okay over the next ten years, things are going to really shift and a lot more jobs will be coming out of the renewable energy industry. But when they look at it, they see the choice between working now for SDG&E [local electric utility], which has been unionized for a long time, which they have a relationship with, and some political leverage over, or they can work for fifty or a hundred different solar companies, 80 percent of which are not unionized, probably will never be unionized, where they will completely lose all that power to get decent compensation for their members. So you need to try to understand where people are coming from and try to find solutions that work for them.

While grassroots social movements such as 350.org, Extinction Rebellion, and Sunrise were certainly effective in elevating truth-telling, in creating policies to end extraction, in pushing some universities and institutions to divest, or promise to divest, their holdings of fossil fuel stocks and bonds, and in creating local policies for renewable energy, the world was still on course to emit 42 gigatons of CO2 in 2021 alone, and the COP 26 in Glasgow that year was widely recognized as a failure. The big stuff had not yet changed: the enormous fossil fuel subsidies provided by governments, the interference of fossil fuel interests in international talks and national policy decisions, the escalating extraction in many countries, the private jets, the enormous sales volumes of CO2-spewing SUVs, which hit record sales in 2021,60 and the official greenwashing strategies of carbon neutral and net zero, which amount to ongoing extraction now with a vague promise of action later.

Whether ongoing grassroots activity, including a scaling up along the principles discussed in this chapter, will be sufficient to stop this trajectory is obviously still an open question. The existential threat posed by global heating and the urgency of taking dramatic action to address it has led the human ecology writer Andreas Malm to counsel the wider climate movement to reevaluate its commitment to nonviolence against property.61 Malm has acknowledged that such strategies as damaging SUVs, disabling extractive machinery, and shutting off oil pipelines could backfire on the movement more generally and that such actions would touch only a tiny fragment of the vast CO2-emitting property of the global energy infrastructure. Nonetheless, based on his understanding of the role that a radical flank that engaged in property damage played in the suffragette movement, the civil rights movement in the US, and the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa, he argued that similar actions by a radical flank within the environmental movement could discourage further investment in the fossil fuel industry and hasten the day when fossil gas, oil, and coal become stranded assets, leading to a huge plunge in the industry’s stock prices.62 Although Malm’s position is not currently shared by many in the climate movement, even a commentator who has argued strenuously against it nevertheless concluded by saying, “[p]oliticians should take it as a warning: If governments cannot protect their citizens from fossil fuel oligarchs, then those citizens will turn to other means of self-protection – regardless of their strategic merit.”63

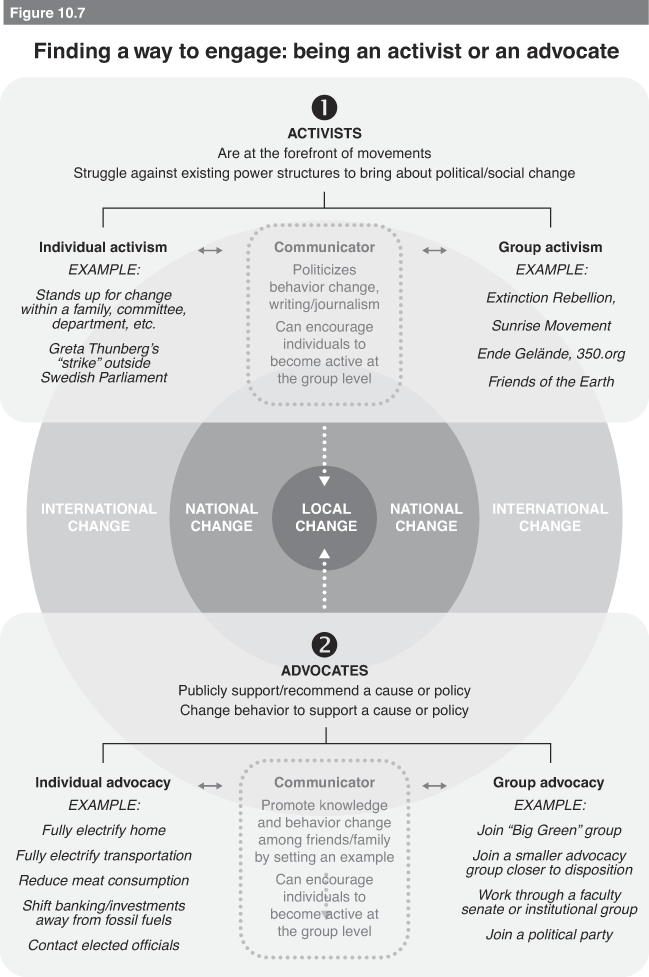

Being Active without Being an Activist

Although the transition away from burning fossil fuels is unlikely to happen without a strong and growing grassroots movement to hold institutions and politicians to account, engaging in political or social activism is not always an option for a given person at a given point in their lives or the only way one can have an impact on the problem. This section thus explores some other ways in which individuals can support that transition (Figure 10.7).

One such way is through membership of other kinds of group than the grassroots organizations described above. For example, the larger nonprofit or nongovernmental organizations that are sometimes referred to as Big Green, such as the Sierra Club, have long been engaged in efforts that can be synergistic with those of grassroots climate change movements. While these larger groups often depend for their legitimacy and financial survival on their embeddedness in the established organizational structures of wider society, which can often limit or compromise some of the actions they can take, they also have much more financial clout, access to mainstream media, networks of millions of paying supporters, in-house lawyers, and access to politicians and powerbrokers.

Individuals can also use their membership or role within an institution, such as serving on the faculty senate of a university, the budget committee of a church, or the investment committee of a condominium association, to influence that organization’s energy use and financial decisions, such as shifting their banking services from banks that are financing the fossil fuel industry or moving their campus from burning fossil gas for power generation to renewable energy sources.

Another option is to take actions as an individual that will support and hasten the transition to renewable energy sources. It is now possible for even mid-income households to get off fossil fuels by using electricity to cook and heat water and to charge an electric car. (The price of an entry-level EVs is expected to hit parity with internal combustion engine vehicles by 2025, and they are cheaper to maintain – although recent supply chain issues cast this into some doubt.)64 One can also choose to shift one’s mortgage and personal banking away from Chase, Citibank, Bank of America, and Wells Fargo to a local credit union that does minimal financing of fossil fuel extraction.65 There are also numerous ways in which individuals can contact city, university, health system, or state and national leaders about their climate policy positions.

Of course, these kinds of individual actions can become much more consequential when they are coordinated with other people, such as shifting one’s personal banking in concert with the Stop the Money Pipeline campaign, advocating for similar actions among friends and family members, and timing one’s contacts with officials to coincide with those of hundreds or thousands of others. Likewise, making changes in one’s personal lifestyle is most effective when it helps serve as a lever for broader society-wide changes. As environmental writer Sami Grover observes, “[w]hen we ride our bikes, our power lies not in cutting our personal travel footprint – an impact that seems trivial when surrounded by gigantic, diesel-chugging trucks. Instead, it is in creating a space where politicians and planners feel confident investing in bike-friendly infrastructure and policies.”66 Better yet is to also team up with or donate to a local bicycle-promoting group to help make their advocacy within the city more powerful.

As this chapter has shown, a big part of this struggle is transforming people’s attitudes and shifting social norms, which almost anyone can help do by sharing knowledge about the science and impacts of global heating and the technical feasibility of the energy transition with friends and family and modeling such behavior changes as flying less, driving less, and reducing meat-eating (as Chapter 9 pointed out, animal agriculture amounts to about 13 percent of global emissions). Elementary, high school, and college teachers can introduce elements of the climate crisis into their classes, or even create classes directly focused on the topic. Academic researchers can choose to reorient their research to topics that can advance our ability to understand and meet the technological, political, social, and psychological challenges of the shift to renewable energy.67 Artists can volunteer their services to help produce posters, websites, and murals promoting climate awareness and advocacy, and see Table 10.2 for examples of ways that other careers provide opportunities for climate action.

Table 10.2. Examples of ways to make a difference within different jobs and roles

System change is fundamentally important, but we will get there partly by personal changes made along the way. It is a false dichotomy that personal changes and system changes are separate from each other (see Table 10.3 for this point and other “discourses of climate delay”). As activist and climate scientist Peter Kalmus has succinctly written, “[t]here is no collective action without individuals choosing to contribute to it. There is no cultural shift without individuals leading the way.” In short, he argues, “[t]here is no bright line between systems change and individuals acting according to their principles.”68

Table 10.3. Common discourses of climate delay (forms of response skepticism)

| Response skeptic | Intended meaning | Type of discourse | Answer |

|---|---|---|---|

| What about China? | It is pointless to cut emissions elsewhere because China emits more now | Redirecting responsibility – someone else should act first | China’s emissions are currently greater than those of the USA annually, but not per capita or historically, and much of China’s emissions arise from products consumed by the Global North. China has already installed over 1,000 GW of renewable energy, more than ten times the total energy generation of California. As the major military, economic, and political power, the USA has a responsibility to lead in emissions reductions. |

| Individuals and consumers are responsible for action or evil corporations are at fault and must change | The focus on individuals lets the system and fossil fuel industry off the hook; the exculpatory focus on corporations lets individuals off the hook | Redirecting responsibility – someone else should act first | The focus solely on individuals or corporations is a false dichotomy. There is no clear dividing line between the need for systems change and for individual action – e.g., if many individuals shift their personal banking from banks that finance fossil fuel extraction, those banks will change their actions. |

| What about lithium? | Shorthand for a legitimate concern about extractivism related to the transition to renewable energy and EVs | Emphasizing the downside – change will bring new disruptions | This legitimate concern could be accommodated with a commitment to consumption reduction, more public transit, increased recycling, substitute materials, and new ethical standards for minerals sourcing. |

| Renewable energy is greenwashing | Greenwashing refers to creating a false impression that one is taking environmental action when one is not; the concern here is that renewable energy is yet another form of exploitation | Emphasizing the downside – change will bring new disruptions | A strong version of this claim seems like nihilism, as there is no way to stop global heating without abandoning fossil fuels and transitioning to renewable energy. A weaker version intended to criticize boosterism for renewable energy without cognizance of its problems is legitimate but can be accommodated with a commitment to consumption reduction, public transit, and minimization of extractivism. |

| It’s too late | Catastrophic climate change is already baked in no matter what we do | Fatalism, doomism, or defeatism – denying possibility of mitigating climate change | If we reach tipping points, it may become too late, but until then, they provide only more reason to act. Although some amount of heating is baked in no matter what we do, there is a huge difference between that and projected rises if we do not act immediately. Every fraction of a degree has enormous implications for billions of people. |

| It’s hopeless | Because of capitalism or “selfish” human beings, nothing we can do will matter | Fatalism, doomism, or defeatism – denying possibility of mitigating climate change | This position is too easy for comfortable people to take while hundreds of millions in other parts of the world face mounting difficulties because of the ongoing emissions created by rich countries and people. History has shown that social change is possible despite entrenched interests and injustices and that industrial economic policy is not incompatible with capitalism. |

| The renewable energy transition generates lots of emissions itself | It’s pointless advocating for renewable energy | Fatalism, doomism, or defeatism – denying possibility of mitigating climate change | The facts rely on life-cycle assessments of how many emissions are created by building wind and solar plants, relative to the fossil fuel energy status quo. A large wind turbine does require mining, steel, and concrete, but about six to nine months of operation is enough to compensate for the emissions from construction, leaving it virtually carbon free for the next 20 years.69 |

| Our climate plan is carbon neutrality | Carbon neutrality typically means to keep on emitting and to rely on purchases of carbon offsets | Pushing nontransformative approaches – disruptive change is not needed | By continuing to burn fossil fuels one is maintaining the economic and political might of fossil fuel interests and continuing to do damage to the biosphere. Meanwhile, carbon offsets are usually impossibly cheap, often neocolonial, often uncertain whether they will deliver the claimed benefit, and hard to validate regarding additionality. |

| We need to rely on carbon capture and hydrogen produced from methane | The fossil fuel industry is “part of the solution,” “low-carbon” fossil fuels are bridge fuels | Pushing nontransformative approaches – disruptive change is not needed | Some continued use of fossil fuels may be necessary to manufacture petrochemicals for specific kinds of plastics, but other uses of fossil fuels must be ended quickly. The promise of technical carbon capture and of “low-carbon” fuels are simply ways for the industry to attempt to maintain its enormous economic and political power. |

| We must develop new technologies | New nuclear, fusion, geoengineering, BECCS, and direct air capture will provide solutions in the future | Pushing nontransformative approaches – disruptive change is not needed | Most of the technology needed for the renewable transition already exists, although further developments in substitute materials and better batteries requiring less extractivism are likely and welcome. But promises of grand new technology constitutes a form of technological solutionism that simply delays the cultural, behavioral, and political changes that are really needed. |

Conclusion

The chapters in Part III have outlined what kind of action will be necessary to achieve a transition to renewable forms of energy and to permanently lower CO2 concentrations to manageable levels. As the book as a whole has made abundantly clear, however, accomplishing this urgent and existential goal will require that decision makers be compelled by pressure from below to change course. In this, every one of us has a role if we want one. We all have the choice and the power to take actions that can make a difference, including making individual lifestyle changes that reduce emissions, voting for candidates committed to eco-friendly policies, changing one’s bank, becoming a climate change advocate within our institutional settings, joining or donating to a Big Green organization, or engaging in grassroots collective action. And all of us can choose to have conversations with ourselves and the people around us that can create a wider awareness of the facts about the human causes of global heating, its current and predicted impacts, the speed and scale of emissions reduction that is needed, and the essential actions that we must take right now.

The long story of skepticism, inaction, and outright opposition to climate action and justice detailed in this book is admittedly discouraging and often maddening. But as this chapter has also shown, history and research both tell us that transformational changes in attitudes, policies, and practices are indeed possible when such individual actions are accompanied by coalition building, community activism, and a grassroots movement willing to disrupt established institutional functions by protesting, engaging in civil disobedience, and questioning the social license to pollute. Although concerted pressure must continue to be exerted upon government officials at the national and international levels, occasional wins against fossil fuel interests and for renewable energy in cities, regions, and states remind us that social change can be made by relatively small groups of people working together.