A Requiem for Carpe Diem

What does carpe diem sound like? Apparently, a bit like the Canadian rock star Neil Young – or at least this is how journalists described the experience of listening to the so-called Seikilos epitaph in a recording by the classicist David Creese.Footnote 1 The Seikilos epitaph is a remarkable inscription dating from the second century ᴀᴅ and found in Tralleis, near modern-day Aydın in Turkey. Extraordinarily, the epitaph features a song and some musical notation. Creese’s recording of the song caused a media sensation, and news outlets dubbed the epitaph the ‘world’s oldest song’.Footnote 2 The central section of the epitaph, following an initial elegiac couplet, constitutes the song, over which musical notation is written. Its text proclaims that as long as one is alive, one should not be sad (SGO 02/02/07 Tralleis = GV 1955 = Reference Pöhlmann and WestPöhlmann and West (2001) 88–91, no. 23 = Copenhagen, National Museum of Denmark, Inv. 14897; see Figure 0.1 for a photograph of the stele and Figure 0.2 for the transcription of the musical notation).Footnote 3

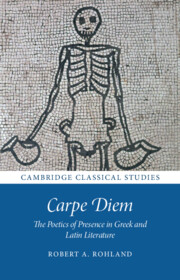

Figure 0.1 Stele of the Seikilos epitaph

Figure 0.2 Transcription of musical notation of the Seikilos epitaph

The message of the epitaph is clear enough: carpe diem! Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die! The motif of carpe diem prescribes the enjoyment of life as the result of insight into human mortality.Footnote 5 In the short Seikilos epitaph these two parts that constitute the motif are particularly apparent; ‘shine, don’t be sad at all’ is the prescription to enjoyment. ‘Life is short, time asks for its due’ offers insight into human mortality. Other texts discussed in this book will sometimes express these two components in more complex or elusive ways, but all texts will fall under this definition of the carpe diem motif: a combination of insight into human mortality and an admonition to present enjoyment. Thus, some form of prescription has to be present in a text to qualify as carpe diem, though this can be implicit and does not have to be an admonition in the strict grammatical sense. Similarly, insight into human mortality can also be included implicitly, for example, by reference to worrisome old age or grievous cares.Footnote 6

The motif of carpe diem is prominent throughout ancient literature and beyond; in early Greek poetry Alcaeus, Mimnermus and others proclaim it, and of course Horace makes the message central to his Latin lyric. It is written on numerous tombstones and carefully crafted on silver cups, while Roman satire even attributes the sentiment to a mouse. Today, the message appears on numerous T-shirts. This book attempts to understand the prominence and significance of the carpe diem motif: it does so by analysing how carpe diem poems are crucial places for negotiating textuality, performance and presence. These issues are naturally prominent in the Seikilos epitaph – an inscribed song. The song of Seikilos thus comes as the prelude to this study: in the present Introduction I offer a new interpretation of this important musical document, and I will show how this new interpretation of the Seikilos epitaph can serve as a model for reading carpe diem. Many motifs we can hear in the short song of Seikilos will reappear amplified in various permutations in the chapters of this book.

Because of its notation, the Seikilos epitaph has attracted much attention as one of the key sources for Greek music in general and musical notation in particular.Footnote 7 Its text, however – the carpe diem motif – is widely dismissed: one scholar, for instance, called the text ‘embarrassingly banal’ and another called it ‘a ditty’.Footnote 8 To be sure, the text of the Seikilos epitaph is hardly original, and its expressions can easily be paralleled elsewhere.Footnote 9 Yet the text and the musical notes of the Seikilos epitaph need to be interpreted in conjunction. Thus, Armand D’Angour has recently shown how impressively the melody underlines the sense of the words.Footnote 10 I argue that the carpe diem text should be central to our understanding of the Seikilos epitaph: while the inclusion of a song on a tombstone is unparalleled and requires explanation, close attention to the text of the epitaph can help us appreciate more fully the function of song.Footnote 11

For any reader of the Seikilos epitaph, the notes mark the central section of the epitaph as a song, that is, as something that was properly performed rather than inscribed. Such a song would have been performed at a drinking party, the prime environment for the enjoyment of life.Footnote 12 This explains the function of song on Seikilos’ tombstone: the song’s placement and its overt and unique identification precisely as a song underline its content, the carpe diem message. As the words exhort the reader to enjoy life, so the notes point back to the enjoyment of music and evoke the banquet as the space of musical performance.Footnote 13 Yet these notes also mark a feeling of loss: once Seikilos is dead, he will never hear music again. Text and notation, then, work together in conveying the message of the epitaph that conjures up present enjoyment and its loss.

Notation is a sign system with a very clear function: one reads notes in order to make music. But did visitors to the graveyard look at the inscription and sing the song or play it on instruments? Perhaps they did so at the funeral itself, but it seems unlikely that the notation still served this function for the average visitor to the graveyard, who would glance at the inscription long after the funeral (note μνήμης ἀθανάτου σῆμα πολυχρόνιον; ‘long-lasting sign of immortal remembrance’). Indeed, musical scores were primarily read and used by performers, and not destined for wide publication or readership.Footnote 14 In the case of the Seikilos epitaph, the notation thus constitutes a sign system bereft of its original function, which makes the system stand out all the more, for the notes clearly set the central section of the inscription apart from its paratext.Footnote 15 This paratext provides a strong contextualisation of a sepulchral inscription; preceding the song, there is the characteristically sepulchral elegiac metre as well as the sepulchral key terms σῆμα and μνήμη. Succeeding the song, Seikilos’ own name in the nominative, along with his father’s name in the genitive, and the epitaphic formula ζῇ (‘during his lifetime’) again manifest the sepulchral nature of the monument.Footnote 16 Yet, framed within this funerary paratext, the song, with its fast iambics and its notation, points back to life, where Seikilos was happily singing at the symposium. The Seikilos epitaph is thus both song and stone, both performance and text: the notes, permanently silent in the graveyard, create a silent requiem for carpe diem. The notation, just like the carpe diem text of the epitaph, both evokes the present moment and laments its loss. As a funerary inscription, the Seikilos epitaph is read, yet readers read not only an inscription but also a song and a moment of present time. They read carpe diem.

A feeling of loss not only applies to Seikilos’ individual life but also to performance and music in literature more widely. For Seikilos, a life of song is succeeded by a written epitaph. I propose that the loss of present enjoyment in Seikilos’ individual life and the way in which this loss is negotiated in his epitaph can offer a model for analysing the perceived loss of performance and music in a wider literary context.Footnote 17 In archaic Greece, songs at banquets expressed the sentiment of carpe diem; such songs simultaneously praised and created present enjoyment. This book analyses what happens to the motif when it is not sung but appears in books, inscriptions, or on artworks. I argue that non-performative textual exhortations to carpe diem demonstrate nostalgia for an idealised notion of banquet songs: texts attempt to evoke music and presence.

To my knowledge, no monographic treatment of the ancient carpe diem motif exists yet; as we saw in the case of the Seikilos epitaph, the motif is usually dismissed as trite and unworthy of further analysis.Footnote 18 This book, by contrast, argues that close analysis of the carpe diem motif can make a key contribution to a question that is central to literary studies in and beyond Classics: how can poetry give us the almost magical impression that something is happening here and now? The book is also a study of lyric and its reception (throughout this book I use the term ‘lyric’ comprehensively to refer to elegy and iambus as well as melic);Footnote 19 I explore how lyric is inscribed into Greek and Latin epigrams (Chapters 1 and 4), how Horace transforms lyric in his Latin poetry books (Chapters 2 and 3), how lyric is cut up and bastardised in anthologies, satires, and other texts (Chapter 5), and, finally, how in all these contexts carpe diem exemplifies a lyric spirit which constantly oscillates between presence and textuality. The period of interest for this study reaches from Alexander the Great to the Latin satirist Juvenal, that is, from the dawn of the Hellenistic period to the Imperial period.

Though there exist some valuable contributions on individual aspects of the carpe diem motif,Footnote 20 a wider-ranging study is needed if we wish to understand the significance of the carpe diem motif for the evocation of present time in poetry. This book will therefore take into account methods from a range of fields in order to do justice to the manifold appearances of carpe diem in ancient culture. I will pay equal attention to Greek and Latin material and I will employ methods from various fields, including philology, epigraphy, art history, music, ancient linguistics, and critical theory. It is only by taking these fields into account that we can understand either the motif of carpe diem or the significance of presence for poetry.

The Pleasure in Greek and Latin Texts

The carpe diem motif urges us to enjoy the pleasures of life. Arguably the most authoritative passage in ancient literature which tells of the pleasures of life is the beginning of Odyssey Book 9. There, Odysseus proclaims that the finest thing in life is to partake at a banquet, listen to the music of a bard, and enjoy wine and company.Footnote 21 When carpe diem poems extol the pleasures of life, these are pleasures of the banquet: eroticism and wine and lyric, an ancient counterpart of ‘sex and drugs and rock ’n’ roll’. Pleasure is almost synonymous with the banquet in its various forms, whether it is the Homeric feast, the Greek symposium, or the Roman conuiuium.Footnote 22 Thus, carpe diem poems tell their addressees to drink, eat, fool around (παίζω), not to deny sex, to enjoy dance and music, not to be greedy, to enjoy luxuries, and to enjoy one’s youth.Footnote 23 Such exhortations regularly appear in pairs or as a triad of merriment: eat, drink, and be merry…Footnote 24 Besides exhortations to specific actions, texts also tell their addressees simply to enjoy life – the most concise exhortation to carpe diem for which Greek and Latin use characteristic expressions.Footnote 25 One should not worry about the future, and indeed one should ignore anything other than sensuous pleasures.Footnote 26 Often we encounter the claim that the insight of carpe diem applies universally to all mankind.Footnote 27 We are also told to hurry and seek pleasures now while we may.Footnote 28 This sense of hurry suits the hunt for sensuous pleasures; conversely, we sense a mismatch when one poet proclaims that we must do righteous deeds as life is short (Bacchylides 3.78–84). An exhortation of this nature is an exception and should arguably be read as a reaction against the calls to sensuous pleasure-seeking elsewhere. There is also some obvious humour at play when Ovid at Ars Amatoria 2.113–22 employs numerous carpe diem images only to say that the shortness of life demands that we study Greek and Latin! For Ovid’s praeceptor amoris, knowledge of Greek and Latin literature is of course only the means for impressing women and having sex (and thus not after all very far removed from the regular carpe diem motif).Footnote 29 Others have been more serious than Ovid when they claim that one must study while one may. Still, when some philosophers and a poet proclaim that true pleasure is found in study, thought, and intellectual conversation, they plainly make these claims in an attempt to rewrite a well-known model that extols the sensuous pleasures of the banquet.Footnote 30 This is where all pleasure is located.Footnote 31 Admittedly, this statement needs some modification; we do not have to assume that every carpe diem poem addressing a lover is necessarily imagined as taking place at a banquet. Rather, what matters is that the erotic poetry is at home at the symposium, though erotic encounters surely also happened in other places. In addition, Roman carpe diem epitaphs repeatedly mention baths as one of the pleasures of life, something with a less close connection to the banquet (though Trimalchio takes his guests for a bath at the banquet).Footnote 32 Yet, despite these caveats, the general point still stands: the ancients would agree with Odysseus that the banquet is ‘the finest thing’.

Although Odysseus’ views on pleasure were formative for Greek culture, neither in this instance nor elsewhere do the Homeric epics urge their audience to carpe diem. Two possible exceptions need to be considered. When Priam visits Achilles in order to release the body of his son Hector, Achilles invites him to eat despite his suffering. Even Niobe, he says, ate after she had lost all her children (Il. 24.602–20). Similarly, after the death of Patroclus, Thetis tells her son Achilles not to refrain from sex, as his life would be short and he would die soon (Il. 24.128–32). Yet, in both these passages, characters are not so much told to enjoy life as to overcome grief: the sentiment is ‘life goes on’ rather than ‘live it up’.Footnote 33

While Homeric heroes have little interest in carpe diem, Homer’s audience and readers are fascinated with the motif. The carpe diem motif is prominent in archaic Greek lyric, both melic and elegy, and it is elegy in particular that reworks Homeric words and images in order to tell its listeners to enjoy life while they may. When Glaucus compares the generations of men to the generations of leaves on the battlefield before Troy (Il. 6.145–9), carpe diem is far from his mind, but in an elegy of Mimnermus falling leaves become an image of human transience and a call to enjoy life.Footnote 34 Indeed, a number of Mimnermus’ scarce fragments are preoccupied with carpe diem and the praise of youth.Footnote 35 Not only does he compare humans to leaves that fall in autumn, but he also speaks of the ‘flower of youth’ (ἄνθεα ἥβης/ἄνθος at frr. 1.4, 2.3, 5.2 if authentic), the ‘fruit of youth’ (καρπός ἥβης at fr. 2.7–8), and the ‘season [sc. of youth]’ (ὥρη at frr. 2.9, 3.1). Human life is compared to nature, then, withering away after a brief season of spring. This comparison between nature’s withering and human transience would become a key trope of carpe diem poems, influencing poets from Horace to Herrick and beyond. Since words such as the flower or season of youth in Mimnermus are taken from the Homeric epics, it has been argued that elegy programmatically appropriates Homeric words for new unheroic contexts: calls to merrymaking phrased in the words of martial epic.Footnote 36 Indeed, Archilochus in his elegies uses Homeric language even as he proclaims that the pleasures of the symposium and carpe diem are preferable to warfare.Footnote 37

Boys and cups seem to be substitutes for Homer’s kings and wars. One of the most influential theories for this apparent change was championed by Bruno Snell and Hermann Fränkel, who argued that a supposed lyric age of individuality witnessed a change of mentalities: lyric poets began to sing of their own life from a first-person perspective in the present tense.Footnote 38 Yet, this view has been challenged on methodological as well as chronological grounds; although the Homeric epics have been handed down to us as the oldest Greek poems, short lyric poetry probably existed already at the same time as, or before the composition of, the Homeric epics.Footnote 39 If so, it is conceivable that images such as the falling leaves were already part of short carpe diem pieces when the Homeric epics were composed.Footnote 40 Another example of Homeric engagement in elegy can be found in the Theognidean corpus, which includes numerous carpe diem poems;Footnote 41 one Theognidean poem seems to appropriate Odysseus’ ‘golden verses’ on the pleasures of life to a sympotic piece that comes close to being a carpe diem poem (Thgn. 1063–8) – yet, it is also possible that the Theognidean poem gives us a glimpse into the sort of short lyric pieces that may have influenced Odysseus’ words.Footnote 42 While it thus seems misguided to argue that lyric poets turned their thoughts to present enjoyment because of a change of mentality, it is arguably right that lyric appropriates epic language for a competing worldview – even though this worldview is grounded in genre rather than the mentality of the age.Footnote 43 Later these textual dynamics would become explicit in a fifth-century-bc elegy of Simonides, which quotes Homer’s line on leaves and turns it into a carpe diem poem.Footnote 44

In melic poetry, Alcaeus and Anacreon are most prominently associated with the carpe diem motif. Perhaps the most obvious feature of Alcaeus’ sympotic poems is that they call for particularly heavy drinking. Thus, the fragment that most clearly brings out the message of carpe diem (fr. 38a) immediately begins with the imperative ‘drink!’ (πῶνε).Footnote 45 The same piece also includes two arguments that commonly support calls to enjoy life while one may: first, the argument that there is no return from death (lines 1–4); second, the argumentum a fortiori, according to which even greater men could not evade death (lines 5–10).Footnote 46 In a number of other Alcaean fragments the time of the year offers the justification for drinking; although the fragmentary status of these pieces does not allow us to say whether they would have included the carpe diem motif, this sort of argument certainly became prominent in Horace’s poetry, in which insights from seasonal change offer the justification for carpe diem, as Gregson Davis has shown in detail.Footnote 47 It is then in the reception of Alcaeus’ poetry more so than in his scarce surviving fragments wherein his importance for the carpe diem motif now lies. This is even more so the case with Anacreon; though Anacreon has the reputation of a carpe diem poet par excellence, this reputation is based on the later reception of his poetry, above all in the Anacreontea, a collection of poems passed under the name of Anacreon. While numerous Anacreontic poems include the carpe diem motif, we can find it in only one of Anacreon’s own fragments.Footnote 48 Anacreon will almost certainly have composed more carpe diem poems, but it is the later tradition which tempts us to supply the carpe diem motif where a fragment itself does not include it.Footnote 49 To what extent melic poets other than Alcaeus and Anacreon engaged with the carpe diem motif is difficult to say. No one else has quite the reputation of a sympotic reveller that Alcaeus and Anacreon have, but some suggestive phrases that are scattered through lyric fragments of other authors suggest that they, too, occasionally exhorted their audience to make merry.Footnote 50

Songs about carpe diem continued after the end of the archaic age. Yet, in some cases one can only speculate; in the classical age, Ion of Chios may have composed elegiac poems on that motif, but though some tantalising fragments extol merrymaking (frr. 26, 27), too little survives of his poetry to be certain.Footnote 51 We also know far too little about Hellenistic lyric, but if Asclepiades indeed wrote lyric poetry (as the metre that is named after him suggests) it would not be surprising if he had written carpe diem poems, since his surviving poetic output shows much interest in this motif as well as in Alcaeus.Footnote 52 It is generally assumed that such poems would have employed lyric metres not in the originally strophic form, but in stichic form: sequences of lines in the same metrical lengths, which were suitable for reading and recitation rather than song.Footnote 53 There is in fact an extant Hellenistic poem of this type that includes the carpe diem motif: Theocritus 29. Theocritus’ poem uncovers a number of traits of archaic lyric in archaeological fashion:Footnote 54 the theme of pederastic love, the opening quotation from Alcaeus, and the Lesbian lyric metre (the Aeolic pentameter). Much like the later Seikilos epitaph, discussed at the beginning of this Introduction, Theocritus’ poem also evokes music in a written medium; Lucia Prauscello has shown how the poem mimics distichic strophic form by creating end-stopped distichic sense units.Footnote 55 When Theocritus tells his addressee in the manner of Alcaeus to enjoy life while he may (Theoc. 29.25–34), we seem to hear momentary lyric song arising from the page of the book.

While hardly any Greek lyric on carpe diem survives from known authors after the archaic age, then, we possess a number of anonymous carpe diem poems, which are sometimes called ‘popular’ songs. Besides a few other examples, such carpe diem songs appear in particular in the Anacreontea.Footnote 56 Songs of this kind are an important reminder that carpe diem songs continued to be composed and performed after a so-called ‘age of song’. Throughout this book they will be regularly adduced as a comparison to textual exhortations of carpe diem, though there is no space for a comprehensive interpretation of such songs. Still, it seems clear that any such interpretation in the future should not only take account of their performative nature, but should also consider to what extent books and writing influenced these songs. For instance, the carpe diem poem Anacreontea 8 begins with a motto taken from Archilochus fr. 19. Mottoes of this kind have received much attention in the context of Horace’s book poetry, where they point to Horace’s engagement with Alexandrian book editions, which catalogued early Greek lyric under such incipits (I will return to Horatian mottoes in Chapters 2 and 5). The usage of the same technique in songs complicates this picture and opens up new avenues of research.

Epigrams offer the most sustained engagement with the carpe diem motif alongside lyric.Footnote 57 ‘Epigram’ describes verse inscriptions as well as the poetry genre that originated from these inscriptions, and the interplay between inscribed and literary epigrams is crucial for the genre in general and its treatment of the carpe diem motif in particular.Footnote 58 Epigram as a literary genre rose to prominence in the Hellenistic period, and we find carpe diem poems among the works of the first generation of Hellenistic epigrammatists such as Asclepiades of Samos (third century ʙᴄ), as well as in late Hellenistic epigrams collected in the Garland of Philip (first century ʙᴄ to first century ᴀᴅ), and also later still in Imperial and late antique epigrams (first century to sixth century ᴀᴅ).Footnote 59 In one epigram, the Hellenistic poet Leonidas of Tarentum urges us to enjoyment, because even prudent Mr Temperance died (AP 7.452 = Leonidas 67 HE):Footnote 60

1 μνήμην Reiske : μνήμης codd. : μνήμονες Casaubon : μνῆμα τόδ’ Grotius

The hexameter looks just like an epitaph and raises the expectation that this is precisely what we are reading. Yet as soon as we are imagining ourselves standing in front of the tombstone of Eubulus and reading the letters of its inscription, a call to drink screams at us at the beginning of the pentameter. The exhortation to drink seems to come straight out of the songs of a lyric poet and clashes with the epitaphic-writing of the previous line. We must revise our interpretation, then; what looked like a grave inscription turned out to be a piece of sympotic banter.Footnote 62 Yet it is of course precisely the play with epitaphic conventions that allows Leonidas to bring out the carpe diem message. Similarly, the epigrammatist Asclepiades of Samos plays with epitaphic formulae in a poem that tells a woman to sleep with him as life is short (AP 5.85 = Asclepiades 2 HE). Such an argument for seduction would of course become extremely common in later carpe diem poems.Footnote 63 While literary epigrams of this kind play with epitaphic conventions, the carpe diem motif was also common on actual epitaphs, which often address a wayfarer and exhort him with a triad of words of merriment to eat, drink, and be merry.Footnote 64 Epigrams thus share with lyric the figure of the addressee as a characteristic of the genre, which is relevant for the present study: a call to enjoyment has to be addressed to someone. Inscribed epitaphs that exhort to enjoyment may long precede Hellenistic literary epigrams; Christiane Sourvinou-Inwood argues that the word χαῖρε on fifth-century-bc epitaphs implies the meaning ‘to rejoice’ and is exclusively said by the deceased to the living.Footnote 65 If right, this is a concise early form of carpe diem in an epitaphic context. Epigram and lyric come from opposing sides to the carpe diem motif, then: while lyric is originally located at the banquet, the place of drinking and merrymaking, epigrams are located on tombs, the place of death.Footnote 66 Lyric and epigram also evoke different media: lyric is imagined as being sung, while epigrams are imagined as being written. Such extreme formalism needs to be modified, though. We have seen above how Leonidas juxtaposes an epitaphic line with a sympotic one. Indeed, ‘sympotic’ epigrams of this kind owe some debt to archaic elegy; deprived from their respective settings on stones or at symposia, Hellenistic epigrams and archaic elegy look rather alike.Footnote 67 Lyric and epigram thus share a relatively short form and a connection to the banquet. Verse inscriptions were of course not only a feature of epitaphs but also of dedications and objects other than tombs. Indeed, a number of carpe diem epigrams evoke inscriptions on objects such as cups and gems, which are part of the sympotic luxurious lifestyle.Footnote 68 Here, epigrams evoke a world of material objects that would have exhorted people to enjoy life while they may. In particular, the skeleton was an image for carpe diem that can be found on cups, gems, mosaics (on tables and elsewhere), and tombstones, as well as in the shape of little figurines.Footnote 69 One version of the carpe diem argument that is particularly prominent in material culture is that death will make us all equal, so we may just as well enjoy ourselves while alive.Footnote 70

Latin literature follows Greek models in treating the carpe diem motif in particular in lyric. Thus, Catullus wrote a carpe diem poem that contrasts individual human life with the cycle of nature: ‘The Sunne may set and rise, but we contrariwise sleepe after our short light one everlasting night.’Footnote 71 This contrast between nature’s renewing cycle and the death of individual human life would become a key trope of carpe diem poems, in particular in Horace’s poetry.Footnote 72 Indeed, while Catullus’ carpe diem poem remains an isolated example in his corpus, in Horace the sentiment becomes a ‘philosophical position advocated throughout the œuvre’:Footnote 73 time and again Horace’s odes tell their addressees to enjoy the present.Footnote 74 Horace famously writes himself into the canon of lyric poetry (C. 1.1.35–6). His poetry becomes a postscript to the Greek lyric tradition as numerous odes follow on from an initial quotation or motto from Greek lyric. Such poems collapse the time that separates Horace from archaic Greece, as Horace virtually joins the momentary celebrations of Alcaeus and the like: nunc est bibendum! (‘Now we must drink!’). The generic self-consciousness of Horace guarantees that not only his own poetry but lyric as a genre becomes the poetry of carpe diem.Footnote 75

Roman epitaphs, just like Greek ones, frequently include the carpe diem motif.Footnote 76 But Latin literature does not have an equivalent to the vast numbers of literary epigrams that the Greek Anthology preserves. Still, the epigrammatist Martial wrote a number of carpe diem poems.Footnote 77 Whether the pseudo-Vergilian elegiac poem Copa also belongs to the epigrammatic tradition is doubtful at best.Footnote 78 In this elegiac poem of thirty-eight lines a barmaid praises the features of her establishment and tells her addressee to live it up while he may. Wilamowitz argued that the poem is an embellished version of a tavern shop sign that would advertise its virtues; it would thus be an extended epigram.Footnote 79 Yet, there are no signs in the poem that hint at writing and shop signs; rather, the barmaid is said to dance and make music. It thus appears more likely to see connections between the piece and popular song and performance; we are invited to listen to the song of the barmaid and imagine her dancing.Footnote 80 The Copa is difficult to date, though may be a first-century-ᴀᴅ poem. In late antiquity we can find more Latin elegies on the carpe diem theme; these employ the elegiac metre for themes that owe much to Horace’s lyric.Footnote 81

While lyric and epigram are the two genres that show the most sustained engagement with carpe diem, there remain three categories that need to be addressed: the false, the lost, and the ugly. These will be discussed in turn. The false: the carpe diem motif is often characterised as Epicurean.Footnote 82 Yet, the carpe diem argument would not be possible without fear of death; it is this fear that compels us to hurried pleasure-seeking during our lifetime. Epicureans, such as Lucretius and Philodemus, thus explicitly disassociate carpe diem from true Epicureanism.Footnote 83 Indeed, as Lucretius is doing so, he tells of a banqueter who bewails the shortness of life and takes this as an excuse for pleasure-seeking. Lucretius may take his aim here at the sort of poetry that is set at banquets, in which the carpe diem motif is common: lyric and epigram.Footnote 84 If so, this passage offers further support for the stance of this book, namely that the carpe diem motif belongs to banquet poetry, not philosophy. Although real Epicureans rejected the idea of carpe diem, many hedonists used Epicureanism as an intellectual pretence under which they sought pleasures. Seneca paints a vivid portrait of such people (Dial. 7.13), and popular or trivialised Epicureanism of this kind can also be seen on a silver cup that shows (among others) Epicurus in the form of a skeleton next to whom is written ‘pleasure is the goal’ (τὸ τέλος ἡδονή at Louvre, Bj 1923; see Figure 4.1c).Footnote 85 When Horace’s carpe diem poems include Epicurean imagery and phrases, this, too, should be attributed to popular Epicureanism.Footnote 86

While Epicureans would not subscribe to the idea of carpe diem, the question arises if other philosophical schools proclaimed this idea. It may seem intuitive to associate the idea of carpe diem with Aristippus and the Cyrenaics since their philosophy is associated with pleasure and seemed to exalt sensuous pleasures. Yet it is difficult to assess whether or not the Cyrenaics told their followers to make merry while they may. If Aristippus left behind any writings, they are lost to us, and we rely on later, sparse, often unreliable testimonies for his philosophy.Footnote 87 In one particularly suggestive fragment Aristippus says that pleasure can only be found in the present, though it is not clear whether this argument in a larger context would have amounted to carpe diem.Footnote 88 The question cannot be answered with certainty, then, and an additional difficulty concerns possible differences in the philosophical doctrines between Aristippus and later Cyrenaics; Hegesias, a later Cyrenaic philosopher, held the pessimistic view that happiness in life is so difficult to attain that death may be more pleasant, that is, the hedonistically preferable option.Footnote 89 This seems a far cry from carpe diem.

Seneca is arguably the philosopher who wrote most extensively on the shortness of life.Footnote 90 Yet, his teachings, too, differ from the idea of carpe diem in two important ways. First, the carpe diem argument poses that life is an absolute good and death is an absolute bad, for one can only find pleasure in the former and not in the latter. Seneca disagrees: life is not an absolute good and the wise man chooses to die rather than to live on in a miserable life. Seneca can thus criticise a certain Pacuvius, who seems to exemplify the carpe diem attitude as he celebrates each day his own funeral among wine, dinners, and male prostitutes who shout ‘he has lived’ (Epist. 12.9). Pacuvius’ actions seem to reveal an overestimation of life as well as a fear of death.Footnote 91 For Seneca, this makes Pacuvius a fool. Second, the carpe diem argument urges to hurried pleasure-seeking in the present as the future is beyond our control. Seneca, however, claims that the wise man can bring past, present, and future all under his control.Footnote 92 Whoever finds pleasure only in the present is a fool (Epist. 99.5): anguste fructus rerum determinat, qui tantum praesentibus laetus est (‘He who takes pleasure only in the present sets a narrow boundary to his enjoyment of things’).Footnote 93 Despite the difference in argument, readers of Seneca are frequently reminded of the carpe diem motif and Horace’s treatment of it: numerous images, expressions, and quotations in Seneca are taken from poems that treat this motif.Footnote 94 It is, then, the poetic heritage of Seneca’s language rather than the content of his philosophy for which carpe diem matters, and I will discuss one such example in Chapter 5.

It is time to turn to the lost. Lost lyric poems have already been mentioned. It is more difficult still to judge how lost works in other genres would have changed our understanding of the carpe diem motif. One poem from the classical period which may have offered us a different perspective on the carpe diem motif if it had survived is the Hedypatheia of Archestratus of Gela. In this didactic poem, Archestratus gives culinary insights in hexameters. For instance, he advises ignoring the cheap stuff and heading straight for lobster (fr. 25 Olson and Sens). Apart from timeless insights of this sort, the text also includes the carpe diem motif in one of the longest fragments (fr. 60 Olson and Sens): a free man should enjoy his drinks with dainties, and die if this is not possible. It is tempting – though ultimately speculative – to assume that this fragment would have been a programmatic passage; the whole justification of the work would then have been to enjoy good food because life is short.Footnote 95 If right, Archestratus’ work may have shown us a side of carpe diem that differs in some respects from the texts discussed in this study. First, it would have put a strong emphasis on eating rather than drinking and merrymaking, as is the case in Alcaeus, Theognis, or Horace.Footnote 96 Second, the poem would have been comparatively long, unlike the short carpe diem poems in lyric and epigram, which are the focus of this study. Third, the fragment of Archestratus lets us see more clearly the formally instructive nature of carpe diem poems: didactic poetry and carpe diem poems share a first-person speaker, an addressee, frequent imperatives, and the ostensible aim to instruct. The inclusion of the carpe diem theme in a didactic poem sheds light on these features.Footnote 97

I have argued so far in this section that the carpe diem motif belongs to banquet poetry, that is, lyric and epigram. Yet the picture that is emerging may strike readers as rather too neat – after all, the carpe diem motif is scattered through a multitude of texts throughout different genres and ages. Thus, in tragedy a Persian king ends a speech with this sentiment (A. Pers. 840), and the drunk Heracles dedicates a little speech to the idea of merrymaking (E. Alc. 780–802).Footnote 98 In comedy, too, we see the motif in a number of fragments.Footnote 99 Pastoral poetry, Latin love elegy, epic, and didactic poetry all include the carpe diem motif.Footnote 100 Satirists attribute the sentiment to a mouse and a gigolo.Footnote 101 The carpe diem argument appears as a gnome or even cliché in these texts. Such messy, scattered pieces of carpe diem, which turn the motif into a cliché and can appear in contexts far removed from lyric settings, are what I have been calling ‘the ugly’. Yet, while the motif appears in these texts, this does not make them all carpe diem texts; in other words, Aeschylus’ Persians is not a tragedy on carpe diem just because a character voices this sentiment at one point. On the contrary, carpe diem sections that appear in longer texts regularly feel alien to their context: through their diction and imagery they evoke lyric poetry and look like quotations. Chapter 5 looks at some – though necessarily not all – instances of such carpe diem sections in longer texts.

The short survey of the carpe diem motif has pointed to lyric and epigram as the two genres in which the motif appears most frequently. I have so far only touched upon a key difference between these two genres: lyric hearkens back to performative song, while epigram looks back at written inscription. This difference in media is important for the carpe diem motif and will be addressed in the next section.

Performance, Text, and Evocation of Presence

Carpe diem poems proclaim the supreme importance of the present moment, the here-and-now. As such, these poems directly concern a topic that has been central in studies of lyric as well as literature more generally: the relation between lyric poems and their setting in the present. Literary scholars have tackled this theme of presence with divergent approaches – though they all agree on its importance.Footnote 102 In this section, I wish to show how my own approach relates to existing methodologies and how a close analysis of carpe diem poems can advance our understanding of this problem.

Carpe diem poems call their addressees to the momentary pleasures of the banquet. Early Greek lyric of that sort was also itself an element of the banquet, where it was sung. The ideal carpe diem poem would not only urge present enjoyment, but its performance at the symposium would make it a present event, and its music would create enjoyment. Yet, did such an ideal carpe diem poem ever exist? Research on early lyric, particularly from the 1980s onwards, has done much to highlight the significance of performance and the ‘song culture’ of Greece: numerous important studies have focused on the social function of the performance of lyric songs in their historical or ritual context.Footnote 103 Thus, the function of Alcaeus’ poetry, for instance, has been seen as forging bonds between men of the elite at the symposium.Footnote 104 When we encounter a carpe diem poem in early Greek lyric, in the Theognidean corpus, the likely performance context can add something to the poem (1047–8): νῦν μὲν πίνοντες τερπώμεθα, καλὰ λέγοντες· | ἅσσα δ’ ἔπειτ’ ἔσται, ταῦτα θεοῖσι μέλει (‘now let’s enjoy drink and good talk. But what will happen later is up to the gods’). As the speaker exhorts his fellow symposiasts to enjoyment in drink and good talk, they might indeed be drinking at the very moment of performance, and the poem itself creates the very enjoyment it asks for through its good talk and music. The words of the speaker are truly performative, according to J. L. Austin’s definition of performative words:Footnote 105 the speaker does things with words as his utterance performs an action. When his words urge enjoyment through fine talk, they create enjoyment through fine talk (and music).Footnote 106 Through its performative power, the poem seems to assert an almost magical control over the present. Indeed, the hexameter seems to stress the poet’s control over the present (νῦν μέν), while the pentameter notes that anything after this present moment is uncertain (δ’ ἔπειτα).

The ideal carpe diem poem creates present enjoyment, then. And yet such a poem might be exactly this: nothing but an ideal.Footnote 107 For the stumbling block that stands in the way of this ideal is reperformance. Lyric was frequently reperformed. Lyric carpe diem songs thus did not in fact create a single wonderfully magical moment of present enjoyment that coincided with the performance of the song. Rather, from the beginning, this present moment was designed to be repeatable. The perfect unity of carpe diem, song, performance, and momentary present enjoyment is a nostalgic ideal. Indeed, a number of recent studies on Greek lyric have underlined the importance of reperformance and looked beyond a first performance or original audience of lyric.Footnote 108 This is not to deny the significance of the performative utterance in the Theognidean carpe diem piece. But reperformance cautions us against a too-pragmatic reading of performance. Already in the Theognidean corpus we can observe poems that evoke the present moment rather than simply being present: the moment (νῦν) will endlessly recur.

The turn to song culture in studies of archaic poetry has also had an impact on studies of later Greek and Latin poetry. This has taken two different forms. On the one hand, later poems came to be seen as songs embedded in rituals and social contexts, akin to Greek lyric. On the other hand, Latin as well as Hellenistic poetry has been described as detached book poetry, the polar opposite of early Greek song.Footnote 109 Thomas Habinek’s book The World of Roman Song is the most notable contribution to the former approach.Footnote 110 Habinek’s emphasis on song and its aspiration to enchant and do things with words is welcome. Yet, as Habinek takes statements of Roman poets about their carmina at face value and turns Roman poetry into indigenous, ritualised song, he risks ignoring both its literariness and Greek heritage.Footnote 111 The debate about Hellenistic literature in general and epigram in particular is comparable: Alan Cameron argued that sympotic epigrams were the product of a lively performance culture at symposia, whereas other scholars emphasised the importance of books and writing for such epigrams.Footnote 112 There thus seems to be a need to look at Greek and Roman material collectively. This is even more the case as scholars on early Greek poetry also started to look beyond performance and textuality in their research. A volume edited by Felix Budelmann and Tom Phillips analyses how early Greek lyric poems can be both text and event.Footnote 113 Thus Giambattisto D’Alessio’s contribution in this volume argues that already Sappho’s poems are not ‘straightforward scripts of ritual performances’ but rather ‘evoke such performances, or look at them sideways’.Footnote 114 I will show how Hellenistic and Roman poets take the cue from such archaic models when they evoke presence.Footnote 115

The question of to what extent Latin poems should be understood as songs or written texts has been debated with particular intensity in the case of Horace.Footnote 116 The Latin lyrist Horace introduced the Romans to Greek-style lyric songs they had never heard before, and he found it pleasing that gentlemen read his poetry with their eyes and held it in their hands. These words are of course not my own but Horace’s (Epist. 1.19.32–4), and they should give pause to anyone who maintains that Horace simply sung his lyric poetry.Footnote 117 Indeed, elsewhere Horace speaks of ‘songs (carmina) that deserve preserving with cedar oil and keeping safe in smooth cypress’, in an image borrowed from Callimachus.Footnote 118 Horace’s songs are songs to be read and seen on the page of a book.Footnote 119 And yet songs they are, according to Horace. There thus arises the danger, if we avoid Charybdis and steer clear of the fiction of song, that we fall victim to Scylla and interpret Horace’s poetry as detached literary book poetry in strongest contrast to allegedly organic pre-literary Greek lyric.Footnote 120 This is a difficult course to steer. A middle course needs to be taken – but, as Odysseus learned the hard way, it is advisable to stick somewhat closer to Scylla, which is in our case book poetry. In other words, Richard Heinze’s well-known dictum, according to which Horace’s song is nothing but fiction, helps us to see how striking the concept of lyric is on the pages of books.Footnote 121 It also makes us see more clearly how the page of the book mimics song: even Horace’s stichic poems were apparently arranged in four-line stanzas (Meineke’s Law).Footnote 122 Finally, it points to the influence of Hellenistic book editions of early lyric, which had already published lyric texts without accompanying musical notation.Footnote 123 The next question, though, is why this fiction of song still matters for Horace.

The preceding paragraph already hints at the influence of a number of scholars who have raised important questions concerning the textuality and performance of Horace’s book poetry. Alessandro Barchiesi addressed such questions in an influential article, titled ‘Rituals in Ink’.Footnote 124 Barchiesi notes that Horace writes himself into a tradition of Greek lyric poets (C. 1.1), but that two elements of Greek lyric are notably lost in his poetry: music and performance. Yet, Barchiesi argues for Horace that ‘what gets lost of a tradition continues to work in absentia’:Footnote 125 Horace’s poetry projects and recreates performance through textual means. That is to say, Horace is acutely aware of the performances, occasions, and moments in time of early Greek lyric, and he makes these features a major theme in his lyric.Footnote 126 Barchiesi also stresses how reperformance connects early Greek lyric with Horace’s book poetry: though Greek lyric describes unique events in time, such as dinner parties or feasts for the gods, these should be reperformed. In Horace’s lyric, ‘every reading is a reperformance’.Footnote 127 Besides Barchiesi, Michèle Lowrie has extensively discussed the role of text and performance in Horace and Latin literature more widely in two monographs, Horace’s Narrative Odes and Writing, Performance, and Authority in Augustan Rome.Footnote 128 Lowrie argues that Horace’s poetry is centred on a tension between its professed status as momentary song and its reality as permanent text. A reader, Lowrie argues, is constantly invited to explore the tension between the media and to deconstruct Horace’s ‘poetics of presence’.Footnote 129 The subtitle of my book, ‘The Poetics of Presence in Greek and Latin Literature’, indicates my debt to Lowrie. Yet, while Lowrie sees in Horace’ poetics of presence primarily a construction that invites its own deconstruction, I emphasise that poetic presence can also succeed in giving us the impression that something is happening here and now. The influential studies of Barchiesi and Lowrie have opened the door for others to look beyond a simple dichotomy between texts and performance. Thus, recent monographs that discuss Horace alongside other poets still wrestle with the problems that Barchiesi and Lowrie have set out: Lauren Curtis on choral performance, Kathleen McCarthy on the first-person form, and Adrian Gramps on occasion all argue that performance is a key issue with Horace and other poets.Footnote 130 These studies, as well as my own, tackle a problem which Lowrie neatly describes as the ‘relationship between a text and its world or worlds’.Footnote 131 Where my own approach differs from previous ones is in that I attempt to include a world or worlds of things, such as monuments, inscriptions, gems, cups, and calendars, alongside my interpretation of texts.

It is not only in classical studies that debates around performance and presence have been prominent. In English and Comparative Studies, Jonathan Culler argues in his Theory of the Lyric that one distinctive feature of lyric is its ability to ‘produce effects of presence’.Footnote 132 By this he means, for instance, the striking use of present tenses, addresses, and apostrophes in lyric poetry. The present tense is characteristic for lyric, and Culler argues that the tense creates a now that becomes repeatable; this, he says, is particularly the case of lyric written in English, which conventionally uses the simple present of habitual action, although the grammar would normally require a progressive tense (‘I wander through each chartered street’ rather than ‘I am wandering’).Footnote 133 According to Culler, address is another device that can produce effects of presence. When lyric poems address someone or something, they evoke the presence of this someone or something: ‘if one puts into a poem thou shepherd boy, ye blessed creatures, ye birds, they are immediately associated with what might be called a timeless present but is better seen as a temporality of writing […] – a special temporality which is the set of all moments at which writing can say “now”’.Footnote 134

One of the most radical proponents of ‘presence culture’ (as he calls it) is Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, a scholar of Romance and comparative literature.Footnote 135 According to Gumbrecht, the humanities in general and literary studies in particular have focused exclusively on hermeneutics and interpretation. Gumbrecht, conversely, argues that there is another dimension to texts beyond meaning and interpretation: presence, and the ecstatic moments art can create. What Gumbrecht advocates can perhaps be illustrated by a well-known anecdote from the life of the classical scholar A. E. Housman.Footnote 136 When lecturing, Housman came to Horace, Odes 4.7, a carpe diem poem that ‘he dissected with the usual display of brilliance, wit, and sarcasm’. He then notably stepped aside from this usual habit of his and invited his class to look at the ode ‘simply as poetry’. Housman proceeded to recite both the Latin poem and his own English translation. Afterwards he quickly confessed that he regarded the ode as ‘the most beautiful poem in ancient literature’, before he rushed out of the room. The anecdote shows us a development in nuce, in a single lecture, which Gumbrecht sees in the humanities at large: the attempt to tackle a text with traditional hermeneutic tools and to get to its meaning gives way to a turn to presence. It seems that Housman attempted to recapture a facet of the ode that goes beyond its meaning and which consists of its sound, its quality of being in the moment and making the moment present. Not by chance did Housman recite the poem and his translation in May, ‘when the trees in Cambridge were covered with blossom’: ‘The snows are fled away, leaves on the shaws | And grasses in the mead renew their birth […]’.

The occasion of Housman’s recital matches the occasion of the poem, and young students are a fitting audience for carpe diem poems that tell their addressees to enjoy their bloom of youth.Footnote 137 In some ways, then, Housman’s translation seems to grant us a poem that is grounded in occasion to an extent that some scholars of archaic Greek lyric only wish for. And yet the very word that means ‘now’ in the first line of Horace’s poem is left untranslated: redeunt iam gramina campis (‘And grasses in the mead renew their birth’). A closer translation would be ‘now the grass is returning to the fields’. Housman leaves out the word ‘now’, and rather than the momentary progressive present tense (‘is renewing’) uses the simple present tense of habitual action (‘renew’). This suggests the iterability of the moment, and we can indeed find inscribed in the poem moments from Housman’s past, when during his own undergraduate days he fell in love with his fellow student Moses Jackson. For Housman would later end a poem to Moses Jackson with words that are evocative of the last lines of Horace’s ode and his translation.Footnote 138 The late spring moment that Horace experienced in Rome thus fuses with the very late spring moment at Housman’s lecture in Cambridge, with such moments in his youth, and with countless other spring moments of their readers.Footnote 139

Housman’s treatment of the Horatian ode brings out qualities which Gumbrecht would call ‘presence effects’.Footnote 140 These presence effects are, I argue, an inherent quality of carpe diem poems, which strive to evoke presence and momentary pleasure. Perhaps the most striking line in this regard can be found in the second stanza of Housman’s translation: ‘The swift hour and the brief prime of the year | Say to the soul, Thou wast not born for aye’ (inmortalia ne speres, monet annus et almum | quae rapit hora diem at Hor. C. 4.7.7–8). Housman replaced Horace’s indirect statement with direct speech. The direct speech, the address, the succession of six monosyllables, and the archaic diction suddenly change the atmosphere of the poem, as if death were kicking at the door. As we perceive this change of atmosphere, we feel the presence of a different voice in the poem that addresses us: the curt archaisms evoke the days of yesteryear.Footnote 141 But who is talking? It is of course ‘the swift hour and brief time of the year’; in other words, it is time itself that is talking, addressing us. Readers for time to come are addressed with a stomping, capitalised ‘Thou’, as they are cast in the audience of Housman’s lecture and as the listeners of Horace. For a moment we are in the presence of time, a presence that we feel rather than understand, and a time that is our own past as well as Housman’s and Horace’s. The task of this book is to listen to time talking.

The question of performance, presence, and textuality is, then, a major concern in literary studies in and beyond Classics. Yet, an extended treatment of the carpe diem motif has so far not been undertaken, although this motif is naturally paramount for any question concerning presence. This book will show that an analysis of the carpe diem motif is central for understanding how poetry writes now: as carpe diem poems aim to affect our senses as if they were music or wine, they become programmes of a poetry that produces presence. Another aim of this book is to show that Classics as a discipline is uniquely well-suited to explore how literature produces presence: as poems evoke a world of things, of inscriptions, monuments, music, books, wine labels, wine cellars, calendars, and cups, Classics, which is by its nature interdisciplinary, can explore this world of things.Footnote 142

Culler ends his book on lyric by stressing lyric’s heritage in song. He suggests that it might be profitable to experience lyric in the same spirit one may experience song: gaining a sensuous pleasure from sound and rhythm that transcends meaning.Footnote 143 This brings us back to the Seikilos epitaph. Here is a poem that invites its readers to do precisely this: to read it as song, to experience the pleasures of life and song, although it is permanently silent. The Seikilos epitaph invites us to read carpe diem.

The Structure of the Book

Chapter 1 starts by tracing the archaeology of carpe diem. Rather than speculating about the origin of a motif that is already attested in Akkadian and Egyptian sources, I look at the Greeks’ own discourse of the past and how they constructed the origins of the motif. My focus is the hedonistic epitaph of the legendary last king of Assyria, Sardanapallus. Greeks were fascinated with this foreign carpe diem text, which seemed to precede their own history. In fact, however, it was by misunderstanding this foreign monument that they recreated its text: lurking behind Sardanapallus’ Assyrian orgy are Greek banquets and the present tense of performative Greek lyric. As I discuss the reception of the Sardanapallus epitaph, I show how one of Epicurus’ detractors forges a false link between Epicurus and carpe diem, when he changes one word of the epitaph.

Chapters 2 and 3 turn to Horace, who coined the expression carpe diem and wrote some of the most memorable carpe diem poems. Chapter 2 looks at wine in Horace. Rich Romans possessed thousands of wine amphorae, and consular dates marked the age of each amphora. I argue that this made wine storage places into huge drinkable calendars, in which the oldest wines were stored at the back and the younger wines at the front. Every time Horace mentions vintage wines, he accesses this calendar. Time is expressed through wine: opening an old wine creates a moment of present enjoyment which cannot be repeated. Yet, through vintage wines Horace also brings moments of the past to the present. Chapter 3 introduces a linguistic turn. In the Ars Poetica, Horace compares a language’s lexical development to leaves falling from a tree: while some words disappear, old ones return. Both the image of leaves and the understanding of time as cyclical are also part of Horace’s poetry of carpe diem. I show that the poems as well as the individual words of which they consist evoke present enjoyment.

Chapter 4 analyses epigrams and objects between 100 ʙᴄ and ᴀᴅ 100, and discusses how objects and texts engage with one another in expressing the idea of carpe diem. Rarely studied Greek epigrams from the Garland of Philip and texts by the Latin authors Martial, Pliny the Elder, and Petronius point to exciting interplay between the textuality of epigrams and the presence of objects. Besides more conventional literary sources, my analysis also includes numerous artworks and inscriptions.

Chapter 5 looks at passages of carpe diem within longer texts. As carpe diem poems are read and re-read, they become independent textual objects: they can be inserted just about anywhere but never lose their lyric splendour. Thus, Vergil applies the carpe diem motif to a context as humble as cattle-breeding, while both Seneca and Samuel Johnson ignore the context and treat this section as vatic wisdom. I analyse how such excerpts relate to Latin satire, which bastardised other texts, to late antique anthologising, to medieval florilegia, and to early modern commonplace-books.

This book does not proceed chronologically; instead, its chapters are arranged thematically. A strictly chronological order is not realistic when so many inscriptions are difficult to date precisely, nor desirable when thematic arrangement allows us to compare, for example, reactions to the Sardanapallus epitaph from Aristotle, Crates, Chrysippus, and Cicero. The selection of material in the book will necessarily be selective, and not every occurrence of the carpe diem motif in the ancient world will be discussed. But it is hoped that the choices here will prove greater than the sum of its parts. Detailed analyses of the techniques with which texts evoke present enjoyment will arguably prove more useful than an extended list of carpe diem poems.

Last, it should be noted that the term carpe diem may be seen as problematic for several reasons. Taken from Horace, Odes 1.11, it is grossly anachronistic when used to refer to archaic Greek poetry. Moreover, as a quotation from Horace, the term may be strongly associated with Horace’s own version of carpe diem: a cultured dinner party of elite Romans engaging with Greek-style poetry. The term’s strong association with Horace may subsequently run the risk of making the analysis of carpe diem a search for the most ‘Horatian’ poetry, and thus lead to ignoring less ‘Horatian’ forms of carpe diem such as the radically hedonistic Sardanapallus epitaph. Nonetheless, I will resist the temptation to coin a new term to describe this motif. Carpe diem is a universally used and recognised term by scholars, and it is unlikely that others will adopt a new term. Indeed, the striking choice of words, the callida iunctura, is Horace’s domain; whoever strives to rival him and soar to the heights of his ingenuity is likely to fall like Icarus, who, as we are told, gave his name only to the sea. Finally, the Horatian coinage also supports the retrospective approach of this study: as the study analyses acts of reading carpe diem, it is only natural to use a term that has struck a chord with many who read carpe diem.