In 1965, the US Department of Defense produced a film entitled Why Viet-Nam? to explain to American soldiers their nation’s escalating military involvement in that country. The film asserted that Hanoi’s “war of liberation” threatened not just the South (which sought only “peace” and economic reconstruction), but also the rest of Southeast Asia. Per the film’s narrator, any failure on America’s part to resist North Vietnam’s aggression would parallel Neville Chamberlain’s disastrous appeasement of Adolf Hitler in 1938, emboldening the Vietnamese communists and their Chinese and Soviet patrons to gun for the entire region. At one point in the film, US President Lyndon Johnson’s voice boomed over images of National Front for the Liberation of Southern Vietnam (NLF, or Viet Cong) forces, declaring that these Southern insurgents were “guided by North Vietnam [and] spurred by communist China” to “conquer” the South and help Beijing “extend the Asiatic dominion of communism.”Footnote 1

Johnson had long believed, as his predecessors had, that the United States must intervene in Southeast Asia or else face the prospect of bearing witness to the toppling of countries there to communism one after the other, like a row of dominoes. In early 1965, he ordered aerial bombardments of North Vietnam and began deploying US forces to conflict zones in the South. By the end of that year, there were around 180,000 American troops in Vietnam, a number that swelled to some 450,000 two years later.Footnote 2 The Vietnamese communists – with Beijing’s and Moscow’s support – never buckled. In 1969, the administration of President Richard Nixon began withdrawing US forces from Vietnam, having neither scored a clear military victory nor established a sustainable government in Saigon. The US retreat from Vietnam was completed in early 1973, followed closely by a banner year for the communists of Indochina. In 1975 alone, the Khmer Rouge took Cambodia, North Vietnam captured the South, and the Pathet Lao swept to ascendancy in Laos.

The remaining dominoes of Southeast Asia did not follow Vietnam into communism. Major studies concerned with the US debacle in Vietnam thus insist that the domino theory was invalid; that the stakes of American intervention in Vietnam had been exaggerated; and that Southeast Asian nationalism had driven the European and American empires from the region.Footnote 3 But the broader patterns of Southeast Asian history during the Cold War cannot be extrapolated from just the US experience in Vietnam. The region’s nationalists did not roundly reject the Western powers. In fact, when Lyndon Johnson Americanized the Vietnam conflict, Southeast Asia’s anticommunist nationalists had already entered the US orbit to ward off both communist revolutions at home as well as Chinese and Soviet influence in the region. Furthermore, five of these anticommunist states – Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand – held most of Southeast Asia’s peoples, resources, and wealth.Footnote 4 In 1967, these five states formed the regional organization known as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which a senior Singapore diplomat, years after the fall of Saigon, reminded his US counterparts had always been “on your side.”Footnote 5

This chapter traces Southeast Asia’s overall pro-US trajectory from before and through the American war in Vietnam, a process in which the region’s anticommunist nationalists collaborated with the United States and Britain to gain, and remain in, power. Between the late 1940s and the early 1960s, indigenous anticommunist elites in Thailand and the Philippines rose to political dominance with US assistance; in Malaya and Singapore they did so with British support. The United States and Britain, with their Malayan and Singaporean allies, also influenced developments within Indonesia that precipitated the Indonesian Army’s rightwing coup of 1965, a transformative event that removed the left-leaning President Sukarno from power and led to the eradication of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), the third-largest communist party in the world. As US involvement in Vietnam deepened, these five anticommunist Southeast Asian states pursued increasingly intimate political, military, and economic links with the United States and each other. They offered the United States political support for the Vietnam War, namely troops and military bases in their countries, or pleaded their vulnerability as teetering dominoes to acquire more US assistance. In so doing, they correctly anticipated that their US ally would draw them deeper into the American sphere of influence and, where necessary, render them aid against homegrown rivals inspired by Hanoi and Beijing. Indeed, though US leaders despaired over their own efforts in Vietnam, they nevertheless persisted in a broader regional strategy, underwriting their ASEAN allies’ rightward tendencies, and forging a geostrategic arc of anticommunist states that effectively encircled Vietnam and China, and also frustrated Soviet ambitions in Southeast Asia. This anticommunist arc would outlast the US military withdrawal from Vietnam and Indochina’s embrace of communism.

The Failures of Southeast Asian Communists before 1965

In the waning days of the Johnson administration, US intelligence officials concluded that the “Communist parties in Southeast Asia [had] fared poorly,” that communist insurgency was by 1968 “less a threat in Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and the Philippines than 20 years ago.”Footnote 6 For these analysts, the gloomy pall that had settled over the American war in Vietnam did not obscure how regional developments over the longer term had served US Cold War objectives. By the mid-1950s, for example, the United States’ oldest regional ally, the Philippines, had already crushed the Hukbalahap Rebellion (abbreviated as Huk), a peasant uprising with deep links to the Communist Party of the Philippines (PKP) and legitimate grouses against the Philippine elite’s long-standing monopoly of political power and resources.Footnote 7

The Huks had waged guerrilla warfare against Japan’s occupying forces during World War II, much like the Việt Minh in Indochina and the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) in Malaya and Singapore. Sensing that the Filipino elites who still dominated their country after independence planned to keep hoarding wealth and power, the Huks launched their military campaign in 1947. Three years later, when Huk offensives had the US-backed Philippine government on the ropes, Washington and Manila began taking actions that soon overcame the rebels. From August 1950, the charismatic Philippine defense minister (and, later, president from 1953 to 1957), Ramon Magsaysay, reorganized the national armed forces to execute a deadly counterinsurgency program against the Huk guerrillas. Capitalizing on the influx of American military equipment, as well as US assistance in psychological warfare, Magsaysay’s forces went after the rebels so effectively that Huk leader Luis Taruc felt compelled to surrender in 1954, bringing the uprising to an end.Footnote 8 Though Magsaysay did not proceed to snuff out the PKP, the organization without its Huk guerrillas would never again pose an existential threat to the Philippine government, nor prevent its charter membership in the anticommunist Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO), nor evict the Americans from Clark Air Base and Subic Naval Base, the largest US military installations outside the United States.

By the mid-1950s, too, Britain and its Malayan allies had hobbled the MCP guerrillas. The conflict had not started out that way, however. Malayan communists enjoyed some potential advantages over British colonial authorities when they undertook their armed revolt in June 1948. The MCP was almost 95 percent ethnic Chinese (local and foreign born) and popular with many Malayan Chinese, who comprised nearly 40 percent of the population. The MCP, like the Huks, had formed the backbone of the anti-Japanese resistance on the peninsula. Owing to World War II, about half a million of Malaya’s ethnic Chinese had been displaced and were residing in makeshift dwellings (the British called them “squatters”) all around the country’s jungles. The MCP made good use of the Chinese “squatters,” drawing some into their ranks and obtaining supplies and food from others, sometimes by intimidation. Malaya’s jungles covered four-fifths of the peninsula, providing MCP fighters an almost impenetrable cover for their many hideouts.Footnote 9

In addition to these challenges, British leaders’ great fear was that the MCP and Malaya’s Chinese population would serve as a fifth column for Beijing and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). For decades, all colonial powers in Southeast Asia had worried to varying degrees about China’s influence over its diasporic networks. After the CCP took mainland China in 1949, Anglo-American Cold Warriors in particular eyed the region’s Chinese populations with mounting suspicion.Footnote 10 To be sure, Beijing’s determination to marshal its diaspora against the Western powers did not exist only in British and American imaginations. The CCP in the immediate wake of its victory over Chiang Kai-shek and the Guomindang (GMD) formally resolved to expand communist influence in Southeast Asia via its diaspora. US intelligence learned in 1950 that CCP propaganda organs and cultural outreach, along with vigorous campaigns to secure political power through courting ethnic Chinese, were active throughout the region, even in Burma, despite its small ethnic Chinese population.Footnote 11

In fact, many Southeast Asian Chinese did laud the CCP’s win over the corrupt US-backed GMD, taking it as a triumph of Chinese nationalism after a humiliating century of Western and Japanese imperial domination. However, by the mid-twentieth century, many of the region’s Chinese had also planted deep social and economic roots in their adopted countries. Also, many Chinese families had resided in Southeast Asia for centuries and intermarried with the indigenous communities (contributing to a process that scholars have termed “Southeast-Asianization”).Footnote 12 In Malaya, the British-educated Asians, along with middle-class and wealthy ethnic Chinese who believed that the MCP would treat them as class enemies, firmly supported Britain’s anti-MCP campaign and the peaceful transfer of power from Britain to anticommunist nationalists who readily aligned independent Malaya with the West.Footnote 13

At any rate, the CCP appears to have been less committed to the MCP in Malaya (and Singapore) and keener instead on building relations with and supporting the Vietnamese Communist Party and the PKI.Footnote 14 Beijing must have quickly recognized that aiding the MCP would win them no great advantage. After all, Britain’s counterinsurgency tactics took only a few years to turn the tide against the MCP guerrillas. To address the fact that the MCP sustained itself by exploiting the squatters, British colonial authorities forcibly resettled all the squatters into “New Villages” – purportedly, the inspiration of South Vietnam’s “strategic hamlets” – to wall them off from the MCP. Consequently, MCP guerrillas had to infiltrate the heavily guarded New Villages to acquire food, monies, and medicines, a perilous task that left them vulnerable to attacks from British and local forces, as well as exposing the paths to MCP hideouts. British officials, by providing some level of security and economic welfare for the squatters, also ensured the MCP (which could not offer the same) looked far less appealing in the struggle for postwar Malaya. At the same time, British officers routinely brutalized New Villagers they suspected were in cahoots with the MCP to learn the whereabouts of the guerrillas’ refuges. By 1955, British and local forces had eliminated thousands of MCP personnel, cadres, fighters, and sympathizers.Footnote 15 US officials judged a few years later that British methods, brutal and unorthodox as they were, had reduced the MCP to “nuisance status, with less than 800 ‘hard core’” guerrillas – one-tenth of their original numbers – hiding at the Malay–Thai border.Footnote 16

Malaya rose to independence in 1957, led by a class of reliably anticommunist and pro-Western leaders, unencumbered by MCP rivals. The Malayan prime minister, Tunku Abdul Rahman, a Cambridge-educated member of the Malay royalty, would maintain close economic and military links with Britain. But the Tunku also recognized that British power was fading and looked to the United States as a new patron.Footnote 17 Under his leadership, Malaya began cultivating close ties with the United States, allowed Britain to use Malayan military bases for its commitments to SEATO, supported the failed US–British covert operations to bring down Sukarno in 1957 and 1958, and trained South Vietnamese forces in counterinsurgency tactics. The Tunku would also work with Filipino and Thai leaders to establish the Association of Southeast Asia (ASA) in 1961, a regional organization that made no secret of its anticommunist leanings and that, in time, became the foundation for ASEAN.Footnote 18

Like the Philippines and Malaya, Thailand’s authoritarian military government, led by Field Marshal Plaek Phibunsongkhram (known to Western leaders as Phibun), steered a pro-US course during the 1950s. As a lieutenant colonel in the Royal Siamese Army in the 1930s, Phibun had collaborated with French-educated lawyer Pridi Phanomyong in a bloodless coup against the Siamese monarchy, coercing the king into becoming a constitutional ruler. Phibun became prime minister in 1938, renamed the country Thailand in 1939, and three years later (over Pridi’s objections) allied with the then-ascendant Japanese empire. Phibun was forced to resign when the Allies prevailed over Japan. Pridi, on the other hand, cooperated with the Allies throughout the war, assisting the underground anti-Japanese “Free Thai” movement that had been trained and supported by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS, predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency [CIA]). He also attempted to guide postwar Thailand toward civilian government and democratic elections, and, for a brief period in 1946, assumed the position of prime minister to stabilize the country. Pridi voluntarily stepped down after ushering the country through a general election.Footnote 19

In 1947, a military coup put Phibun back in power. And though US leaders bemoaned the demise of Thailand’s democratic government and deplored Phibun’s prior compact with Tokyo, the Americans quickly resolved, owing to Cold War exigencies, to court Phibun’s military-dominated regime. Communist factions were in armed revolt in Burma, Malaya, and Vietnam in mid-1948. And Thailand was located strategically at the center of the mainland Southeast and therefore was vital to US aims of containing communism there. Washington desired a stable, conservative Thai administration, and Phibun’s government fit the bill.Footnote 20

The relationship ran both ways. By early 1950, Phibun also felt the need to cleave to the United States. Beijing had singled him out for criticism in Chinese newspapers, attacking him for ill-treating ethnic Chinese in Thailand. (As prime minister, Phibun had in fact forced Thai Chinese out of major labor and industrial sectors in the 1930s.) As Daniel Fineman notes, the Shanghai paper Dagong Pao announced that the “Fatherland is now behind” the “overseas Chinese,” implying that China planned to support the revolt of its diasporic communities in Thailand. It was unclear if Beijing would make good on this threat. But Phibun believed it had become imperative to secure military and economic aid from the United States and consolidate his regime by suppressing local Chinese and leftist rivals, as well as defend against China’s apparent bent toward expansion into Southeast Asia. He believed he could loosen the spigots of US aid by officially recognizing Bảo Đại, the former Annamese emperor that France had cynically installed as a figurehead to lead Vietnam, and whom the Americans had endorsed as an alternative to Hồ Chí Minh and the communists. Of course, Phibun knew that the uncharismatic Bảo Đại was unpopular in Vietnam, but shunted aside his reservations to make a bold overture to the Americans, a decision that proved a turning point in Thai history. Thereafter, US aid flowed copiously to Phibun’s government, causing his prestige in military circles to soar, while enabling him to crush and otherwise silence his political rivals.Footnote 21

Phibun was so eager to prove his support for US containment policy that, with minimal prodding from Washington, he rammed a resolution through parliament in July 1950 that would send Thai expeditionary forces to aid the United Nations (UN) coalition in the Korean conflict. Phibun’s move, buoyed by military officials who anticipated more American arms as a reward for upholding US aims (Phibun had stoked their expectations), easily ran roughshod over civilian opposition within parliament. The civilian wing of the Thai parliament, which had barely survived Phibun’s return to power in 1947 and had been slowly whittled away, had advocated good relations with powers on both sides of the Cold War divide, insisting this would give Thailand a wider range of diplomatic options. In response, Phibun and the military elites treated as dissidents all the civilian leaders, activists, and journalists who questioned the pro-US bent of Thai policy. He launched a crackdown on them in 1953 that effectively made Thailand a police state. US leaders, for their part, tolerated such repression as long as it ensured Thailand remained a loyal Cold War ally. Indeed, Thailand joined SEATO in 1954, and Bangkok served as the headquarters of the organization.

It would not be plain sailing for Phibun, though. Internal rivalries within the Thai military elite troubled his authoritarian regime, sparking abortive military coups against him. His luck ran out in 1957, when he was finally deposed. But this did not disrupt the US–Thai relationship. Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat assumed power and pursued even closer ties with the United States. In fact, Sarit’s armed forces became almost completely reliant on American military equipment. Sarit, like Phibun, cottoned on to American hints (emanating from the Eisenhower administration) that US aid would accompany the complete elimination of Thailand’s leftists and neutralists. Desperate for more of that aid, Sarit proceeded to repress all opponents of his authoritarian rule. By the time of his death in 1963, Thailand had become locked within a self-perpetuating pattern of military governments in league with America. Sarit’s successor, Field Marshal Thanom Kittikachorn, was the same, and under his leadership Thailand assisted US covert operations in Burma and Laos in the 1950s and 1960s, while Thai air and naval bases provided US airmen platforms to launch punishing raids against North Vietnam. By the late 1960s, US intelligence officials judged that Thailand’s military regime had absorbed too many billions in aid from the United States and set itself so decisively against China that Thai leaders had little latitude for trying a different superpower patron.Footnote 22

Even so, when President John F. Kennedy entered the White House in January 1961, it might have been difficult for US officials to discern how developments in Southeast Asia had started to tilt in America’s favor. The states of Indochina certainly did not give this impression. President Dwight Eisenhower, for one, offered ominous parting words to Kennedy about the Laotian crisis. Laos was wracked by a civil war between the Pathet Lao, a neutralist front, and the US-backed Royal Lao government (RLG). Eisenhower warned Kennedy that losing Laos to the communists would topple all the Southeast Asian dominoes.Footnote 23 US insecurities about Laos would never go away. For though Kennedy hammered out an international agreement to keep Laos neutral, the CIA conducted a destructive and doomed secret war by training and equipping Hmong tribes to fight the Laotian communists.Footnote 24 The Kennedy administration was also frustrated by Cambodian leader Prince Norodom Sihanouk, whose determination to keep his country nonaligned did not preclude him gravitating toward China and allowing the North Vietnamese Army to use his country for sanctuaries, as well as sustaining the Hồ Chí Minh Trail. At the same time, Ngô Đình Diệm’s anticommunist government in South Vietnam seemed in grave danger, a consequence of Diệm’s repressive rule, his intensifying unpopularity, and gathering pressure from North Vietnam and the NLF. The fatal military coup against Diệm in November 1963, subtly abetted by the Kennedy administration, sent South Vietnam spiraling into further instability.Footnote 25

But while Indochina festered, the governments of Malaya, the Philippines, and Thailand grew closer to Washington. In September 1963, a new independent Southeast Asian state, Singapore, joined them. Two years before, the Tunku, British policymakers, and Singapore’s anticommunist Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew had agreed to merge Malaya and Singapore – to be joined by Sabah and Sarawak in British Borneo – into an enlarged federation called Malaysia. This arrangement would grant Singapore full independence from Britain, but within the Malaysian Federation. Complications riddled the Malaysia Plan, not least the fact that the federation would have two prime ministers, the Tunku for the federation and Lee for Singapore. But Britain, along with Lee and the Tunku, prized the expediency of the Malaysia Plan. By relinquishing Singapore, Sabah, and Sarawak, the British could tout to observers worldwide that Britain was truly liquidating its empire in Asia. In reality, the British government had agreed with Lee and his colleagues that Britain would retain control of its massive military installations in Singapore, thereby perpetuating the British imperial presence in Southeast Asia. For the Tunku and Lee, creating Malaysia offered a solution to the thriving socialist movement in Singapore. The Tunku was convinced that Lee’s leftist rivals could potentially seize power from Lee and turn Singapore into a “Cuba in his Malayan backyard”; he longed to employ Malaya’s internal security apparatus (tried and tested on the MCP) toward squashing all the politicians and unionists that one former official of the US State Department had labeled the “Singapore Reds.”Footnote 26

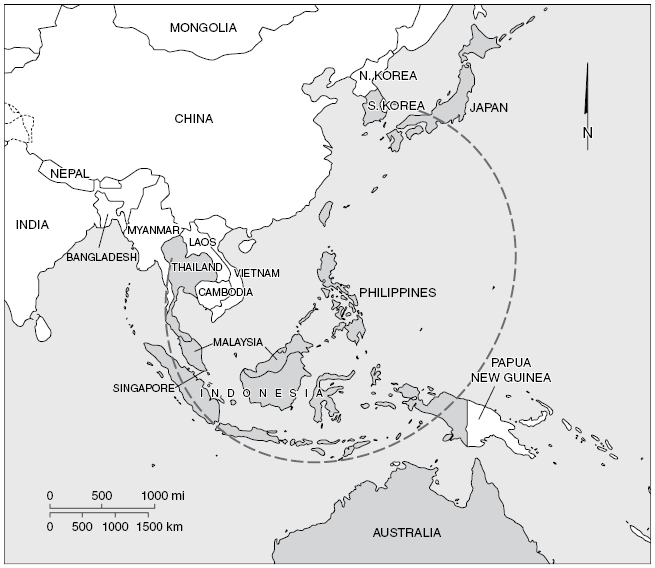

The Tunku ultimately grew impatient and demanded that Lee deal with his opponents even before Singapore joined Malaysia. And Lee, yearning to secure independence for Singapore and his place in the country’s history, summarily incarcerated his enemies (without trial and for years) in February 1963 with the repressive tools he had inherited from the British colonial administration, the same instruments that the Tunku had been itching to use. Lee and his People’s Action Party (PAP) were dominant in Singapore politics from that moment onward.Footnote 27 Like the Tunku, Lee promptly showed himself an ardent supporter of the US presence in Southeast Asia and the American war in Vietnam, contributing to the region’s broader rightward turn. If somewhat dimly, the Americans did perceive that this geostrategic shift was underway. As one Kennedy official predicted in late 1962, the formation of Malaysia “would complete a wide anticommunist arc enclosing the entire South China Sea.”Footnote 28 A few months later, the New York Times echoed that position, describing Malaysia as a “strong bulwark against communism” that produced a “1,600-mile [2,500-km] arc … from the border of Thailand to the Philippine archipelago.”Footnote 29 To all intents and purposes, the pro-Western nations of Southeast Asia encircled the “compromised” states of Indochina.Footnote 30

Indonesia’s New Order and ASEAN

Just south of the so-called “anticommunist arc,” however, was the left-leaning Sukarno regime of Indonesia. In the early 1960s, Sukarno had swung definitively to China’s side in the Cold War, a turn in Indonesian foreign relations that traced its roots to the prior decade. Senior policymakers of the Eisenhower administration were irked by Sukarno’s neutralism throughout the 1950s, viewing the Indonesian leader as alternately playing for economic and military aid from the United States, the Soviet Union, and China, or being highly susceptible to communist blandishments. All three Cold War powers avidly wooed Sukarno anyway, not least because Indonesia was the fifth-most populous nation in the world and home to a vast trove of natural resources. Here, Beijing began to enjoy a slight advantage in cultivating Indonesia, treating Sukarno to such a warm reception on his visit to China in 1955 that he came away enamored of the Chinese leadership. (His trips to the United States and the Soviet Union the next year, despite American and Soviet efforts, did not have a comparable effect on his political predilections.) While Sukarno had abjured communism as an ideology, he nevertheless held communists in high esteem for their revolutionary ardor and nationalist vigor.Footnote 31

More to the point, Washington and its anticommunist allies – Britain and Malaya – were the ones that contributed significantly to Sukarno’s decisive tilt toward Beijing. US and British leaders, already concerned about Sukarno’s burgeoning admiration for China, were further alarmed when, in the mid-1950s, he courted the well-organized PKI as a counterweight to local conservative army elites who were mostly anticommunist in their worldviews and deeply suspicious of the PKI’s links to China. The United States, not yet attuned to the golden opportunity of cultivating the rightwing elites of the Indonesian military, instead collaborated with Britain and Malaya, and also used British military bases in Singapore, in futile operations to topple Sukarno. (In time, Washington would switch tack toward cultivating the Indonesian Army and its anticommunist elites, training, equipping, and funding army officers, thereby building the army’s capacity to take control of the country.) For the moment, however, US, British, and Malayan subversive actions against Sukarno embittered the Indonesian leader, steeling his resolve to embrace the PKI; crucially, these subversive actions also paved the way for deeper Sino-Indonesian ties.Footnote 32 By mid-1961, as Britain, Malaya, and Singapore began negotiating the formation of Malaysia, Sukarno’s political sympathies lay firmly with Beijing’s bellicose anti-imperialist stance.

Little wonder, then, that Sukarno vehemently opposed the creation of Malaysia, calling it a British neocolonial scheme that endangered Indonesian security. The Tunku had, after all, backed the Anglo-American plot against Sukarno. And by Sukarno’s reckoning, Britain’s military installations in Singapore remained an obvious threat to Indonesia. Furthermore, Sabah and Sarawak, on the border of Indonesian Borneo, when integrated into Malaysia, could certainly be utilized to continue US and British efforts against Sukarno. In 1963, Sukarno’s truculent response to Malaysia crystallized as Konfrontasi (Confrontation), a politico-military campaign to “crunch up Malaysia and spit out the pieces.” Radio Peking added its voice to this, quoting its junior partner, PKI Chairman D. N. Aidit, that Malaysia was obviously a “quarantine station” against all socialist nations of the region.Footnote 33

US officials, already vexed by their failing policy in Vietnam, were leery of Konfrontasi dragging the United States into another conflict via treaty obligations to Britain through SEATO, or to Australia and New Zealand under the ANZUS (Australia, New Zealand, United States) Security Pact. The Kennedy administration hoped its aid packages might entice Sukarno away from China and have him climb down from his aggressive stance against Malaysia.Footnote 34

In contrast, Britain and its regional allies had no qualms about taking the fight to Indonesia. What Sukarno foresaw came true. British and Malaysian officials secretly aided Indonesian secessionist groups to destabilize Sukarno’s regime; British troops simultaneously conducted clandestine cross-border raids well into Indonesian Borneo to keep the Indonesian military on the defensive. Additionally, some 60,000 British military personnel were mobilized for the conflict, and more than a quarter of the Royal Navy was involved in operations against Indonesia.Footnote 35 Striking from a different angle altogether, diplomats from Singapore, Sabah, and Sarawak visited seventeen African heads of state from January through February 1964 to convince them that creating Malaysia served authentic local aspirations, not British neocolonialism, and that Sukarno was an unreasonable aggressor who should be censured and opposed. In this endeavor, the Malaysian diplomats did remarkably well. Almost all the African leaders they met agreed that Sukarno’s allegations of British neocolonialism were unfounded. Furthermore, President Camille Alliale of the Ivory Coast expressed “grave disapproval of the Indonesians” and promised, like Kenyan Prime Minister Jomo Kenyatta, to support Malaysia’s candidacy in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC).Footnote 36 With endorsement from the Ivory Coast and Kenya, Malaysia easily clinched nonpermanent membership within the UNSC in January 1965, gaining acceptance as a legitimate political entity and vindicating its cause against Indonesia. Outplayed and enraged, Sukarno withdrew Indonesia from the UN. Of course, he did try to claim victory in August 1965 when Singapore was ejected from Malaysia after months of fractious Sino-Malay tensions and disagreements between Lee, the Tunku, and their respective political parties.Footnote 37 But Singapore did not dissolve into chaos; instead, it rose quickly to become the richest state in the subregion, due in no small measure to its military procurement contracts with the United States, which, after 1965, readily fed the American war in Vietnam.Footnote 38 Absent Singapore, the Malaysian Federation remained otherwise stable and intact. Sukarno’s campaign to “crush Malaysia” had achieved little of what he had hoped.

As Konfrontasi ground on, Indonesia’s rightwing army elites grew worried about their nation’s low-grade conflict with Britain and Malaysia escalating into full-scale war. They had also become frustrated with how their forces were bearing the brunt of Sukarno’s foreign policy excesses and lost all patience with Sukarno’s close ties to the PKI and China, an attitude reinforced by the Indonesian Army’s burgeoning relationship with the United States. As such, the army’s rightwing elites began weighing their options for seizing power. But in an unexpected turn, Aidit and select PKI members launched a preemptive move on October 1, 1965, with the help of sympathetic left-leaning military officers, hoping to protect Sukarno from the army’s rightwingers.Footnote 39 Supporters of the so-called Thirtieth of September Movement (which unfolded a day later than its name suggests) assassinated six Indonesian army generals that Aidit and his collaborators presumed to be the core of the rightwing group opposed to Sukarno. Though Aidit caught his patrons in Beijing by surprise, the Indonesian Army found it easy to capitalize on this opportunity. Major General Suharto accused Aidit and the PKI of mounting a treasonous coup against Sukarno, mobilized a propaganda campaign that with US support insisted that Chinese communists were in on the plot, and with the full force of the army’s machinery and personnel annihilated the PKI and many noncommunists within a few months. The death toll was catastrophic, with estimates at half a million or more dead. Suharto’s troops located and killed Aidit in December.Footnote 40 Bereft of the support of the PKI, Sukarno could not stop Suharto from assuming dictatorial powers. The latter relegated him to the status of figurehead and, two years later, formally took the presidency from him.

Indonesia’s momentous shift to the right in late 1965 reinforced the West-leaning tendencies of Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Singapore. This represented, after all, the biggest blow to international communism in the entire Cold War period. And it was not long before Suharto’s New Order made its regional influence felt. In August 1967, with a substantial push from Indonesian Foreign Minister Adam Malik, the leaders of the five anticommunist nations created ASEAN. The regional organization both succeeded the ASA and retained its pro-West stance.Footnote 41 Assistant Secretary of State William Bundy greeted the formation of ASEAN with optimism, though he and other officials refrained from lauding ASEAN too publicly, worried that such an endorsement could undermine ASEAN’s claims that it sprang from genuine Southeast Asian aspirations and not, like SEATO, from the American mind.Footnote 42

Indonesia continued to please the Americans when it broke its diplomatic relations with Beijing in October 1967, withdrew Indonesian personnel from China, and sent Chinese ambassadorial staff home.Footnote 43 That same month in Foreign Affairs, presidential aspirant Richard Nixon praised the Indonesian Army’s “countercoup” for “rescu[ing] their country from China’s orbit.” Nixon believed that Washington had now scored Southeast Asia’s “greatest prize”: Indonesia’s “100 million people and 3,000-mile [4,800-km] arc of islands containing the region’s richest hoard of natural resources.”Footnote 44 The Johnson administration, for its part, certainly believed it urgent to integrate Indonesia into the US-dominated world system. US economic aid had begun flowing freely into the country; US oil companies were inking deals with Indonesian officials; Washington and Jakarta were steadily reinforcing their military ties.Footnote 45

Suharto and his close advisors understood that throwing Indonesia’s weight behind US Cold War causes would bring rewards from the United States, a familiar dynamic also central to Washington’s relationships with Thailand and the Philippines.Footnote 46 By the end of 1967, US officials noted Indonesia’s “hardening of attitude toward Hanoi,” which was coupled with Malik’s assurance to US officials that Indonesia supported the American war in Vietnam and even escalation of the conflict to involve Cambodia. In November 1969 and January 1970, Indonesian military leaders secretly invited their likeminded anticommunist counterparts from the Cambodian military to study how Suharto and his group had ousted Sukarno. In March, Cambodian General Lon Nol seized power from Prince Sihanouk and immediately received support from an Indonesian military mission. The next month, the United States invaded Cambodia on the pretext of preventing the country from becoming North Vietnam’s launchpad for attacks on South Vietnam.Footnote 47 Indonesian leaders then went full tilt in support of Lon Nol when Nixon tripled the Military Assistance Program to Indonesia a few weeks later and encouraged Suharto to “play a big role in Southeast Asia.” By July, Indonesia had sent Cambodia 25,000 AK-47 rifles, drawn up training programs for Cambodian troops, and readied an Indonesian brigade to be “projected into trouble-spots” on the Asian mainland, with US air and amphibious support.Footnote 48 Indonesia did not prevent Cambodia from falling to the Khmer Rouge years later, but, more importantly, the US–Indonesia alliance grew ever stronger.

In January 1969, the State Department reported that “on the whole” the US “record in Asia has been good.” In effect, the State Department had begun to entertain notions that US frustrations in Vietnam were offset by developments elsewhere in the region. Its report emphasized that a “new spirit of regional cooperation in Southeast Asia” was building sturdy bonds between the United States and its Asian allies. In particular, the State Department noted how ASEAN countries had pursued “multilateral undertakings” with such groupings as the Japanese-led Asian Parliamentarians Union, which linked ASEAN nations to other West-leaning countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and South Korea; and the avowedly anticommunist ASPAC (Asian and Pacific Council), which was formed in 1966 with Australia, Taiwan, Japan, Malaysia, New Zealand, the Philippines, South Korea, South Vietnam, and Thailand. These “undertakings” entwined ASEAN with other pro-West security frameworks such as ANZUS.Footnote 49

Even the grasping Philippine president, Ferdinand Marcos, bolstered US power in the region whenever he sought personal profit from the Vietnam War. Marcos had solicited tens of millions of dollars in US economic and military aid by promising Johnson that he would raise Philippine battalions for Vietnam. Sending only a small force to Vietnam, Marcos instead channeled the bulk of what monies he received from the United States toward reinforcing his increasingly authoritarian and unpopular rule. These schemes made Marcos’ political prospects ever more reliant on US patronage and left his nation ensconced within America’s sphere of influence well after the US withdrawal from Vietnam.Footnote 50

Map 7.1 By the late 1960s, anticommunist states in Southeast and East Asia had completely encircled Vietnam and China.

ASEAN countries were not the only ones in the region that leaned toward the United States. Nonaligned Burma (now Myanmar) under its isolationist junta also entered a “delicate” relationship with the United States, sustained by US economic and military aid. Throughout the Vietnam War, though Burmese leader General Ne Win turned increasingly dictatorial, the United States accommodated itself to his repressive excesses to preserve its ties with Burma. In contrast, Sino-Burmese relations blew cold rather than hot. Ne Win, resistant to Chinese influence, reportedly described Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai as a “bastard” in 1965 for presuming that Burma would readily subordinate itself to China. Burma certainly could not be counted as a firm friend of the United States, but it was by no means a member of the Chinese or larger communist camp.Footnote 51

Buying Time for US Hegemony in Southeast Asia

By the late 1960s, therefore, a nascent US hegemony loomed beyond Indochina across much of Southeast Asia. Why, then, did the United States remain for several more years committed to the flailing Saigon government? There are some well-trodden explanations. President Johnson’s defense secretary, Robert McNamara, for one, admitted decades later that he along with the best and the brightest – ironically named, in hindsight – had simply not grasped how the rise of Suharto diminished the US stake in Vietnam.Footnote 52 In fact, the Nixon administration did attempt to extricate the United States from the war. But its peace talks with North Vietnam broke down repeatedly over such issues as the timetable for the withdrawal of troops, and what form the South Vietnamese government would take after a ceasefire. Also, senior US policymakers believed (in vain) that sustained military force, while unable to rout the communists, might somehow pressure Hanoi into letting Saigon remain noncommunist. US leaders were loath to withdraw from Vietnam without even this paltry victory. Even when Nixon’s triangular diplomacy saw China and the Soviet Union pledge to encourage Hanoi to end its war by means of a diplomatic solution, Hanoi fought on ferociously to extend the war and whittle away any advantages the Americans could bring to the negotiating table.Footnote 53

No doubt, the above reasons and others similarly focused upon the interactions of the United States, China, the Soviet Union, and the two Vietnams help us to understand the protraction of America’s military fiasco in Indochina. But situating the firestorm of the Vietnam War in its peculiar regional context actually illuminates another critical reason that the United States continued to run the gauntlet in a state supposedly devoid of strategic significance to US aims. Indeed, the United States continued to fight the Vietnam War because US leaders and their Southeast Asian allies sought time to bind their fates even more tightly together, to reinforce the existing geostrategic arc that both ran through the ASEAN states and had already contained the influence of Vietnam, China, and even the Soviet Union.

Nixon’s 1967 Foreign Affairs article had recommended a course of action roughly along these lines. He had asserted that US forces in Vietnam had “diverted Peking” and “bought vitally needed time” for Asia’s noncommunist states to stabilize their economies and develop their militaries.Footnote 54 This notion at first blush may not sound novel. Johnson’s National Security Advisor Walt Rostow and ASEAN allies such as Lee Kuan Yew had argued before that the Vietnam War was “buying time” for precisely these purposes.Footnote 55 The crucial distinction, however, was that Nixon believed that that precious time had already been “bought,” that anticommunist Southeast Asia was now primed for much more. To be sure, even Lyndon Johnson, while still in the White House and burdened by the Vietnam War, had at much the same time begun to speak of the “domino theory in reverse” across Southeast Asia, inspired by Indonesia’s explicit anti-China stance in October 1967.Footnote 56 In like vein, Nixon’s article urged US policymakers to “look beyond Viet Nam,” not for insecure and wobbling dominoes needing US protection but to appreciate instead the “extraordinary set of opportunities” now open to America. Most Asian countries saw China as a “common danger,” thought of the United States “not as an oppressor but a protector,” and supported US policy in Vietnam, he insisted.Footnote 57 He was making an argument for consolidating a strategic advantage that the United States already enjoyed.

From outside the White House, Nixon had the luxury of making bold and optimistic statements about “opportunities” and proposing the United States turn its gaze away from the Vietnam War. But he had certainly discerned how Indonesia’s titanic shift to the right decisively tipped the regional balance of power toward the United States. After a whirlwind visit to the region in April 1967, Nixon intuited that the Vietnam War had further intertwined the US anticommunist project in Southeast Asia with pro-US ASEAN leaders’ desire to check Chinese influence and maintain power at home. As US intelligence officials emphasized some months after Nixon’s article, ASEAN leaders harbored a “traditional fear of China [and] distrust of communism as an antinationalist and pro-Chinese movement.”Footnote 58 For these reasons, most of Southeast Asia’s conservative elites had by the early 1960s (as demonstrated above) tied their destinies to the US containment project; South Vietnam’s instability merely increased the urgency of augmenting US predominance in the region as a prophylactic against Chinese penetration. Indeed, the Tunku worried about a Chinese invasion led by a Vietnamese vanguard, and that ragtag bands of the MCP might become reanimated by Hanoi and NLF victories. Lee wanted to ensure that neither North Vietnam nor its Chinese patrons could galvanize any leftist sympathies lying dormant within Singapore’s majority Chinese population. Suharto, having eradicated the pro-Chinese PKI, was determined to not allow Beijing any sway over Indonesia. Thai and Filipino leaders were already in deep with the United States.

But prolonging an already unpopular war to consolidate the US presence in Southeast Asia, a war that had attracted few public endorsements and troop contributions from many of America’s other allies, would take some doing.Footnote 59 The stakes could not have been higher for the ASEAN leaders, and in different ways they threw themselves into the task even before Nixon became president. Malaysia and Singapore proved formidable apologists for the American war in Vietnam, especially after they transitioned into the US orbit to compensate for Britain’s surprise decision – following its expensive campaign against Konfrontasi – to withdraw completely from Southeast Asia. In July 1965, the Tunku addressed all the US foreign policy thinkers that might oppose Johnson’s decision to intervene in Vietnam, publishing an article in Foreign Affairs that underscored how Malaysia “look[ed] northward” with “anxiety,” for Beijing and Hanoi were menacing the Saigon government by “infiltration, subversion and open aggression.” He stated that “we in Malaysia fully support Washington’s actions” in Vietnam.Footnote 60 In 1967 the Tunku took this message international, lashing out at critics of the war at the Conference for Commonwealth Heads of Government in London. He declared that “had the Americans not gone to the assistance of South Vietnam … it was only a matter of time before they [the communists] marched through and militarily occup[ied] all of Asia.”Footnote 61

With aplomb, Lee conducted his public diplomacy along similar lines. In a speech in Christchurch, New Zealand, in March 1965, Lee described how, if Vietnam were to fall to communist forces, Cambodia and Thailand would follow, with Malaysia next on the chopping block.Footnote 62 At the Institute for Strategic Studies in London in June 1967, Lee told his audience firmly that he was a “believer in the domino theory,” that “if American power were withdrawn [from Vietnam], there could only be a Communist Chinese solution to Asia’s problems.”Footnote 63 In October that year, he pledged Lyndon Johnson his “unequivocal” support for the Vietnam War and promised to work on American and international opinion-makers whenever and wherever he could.Footnote 64

ASEAN leaders’ defenses of the Vietnam War, as they circulated in American and international discourse, gave Johnson the means to defy detractors while continuing to prosecute the war. In early December 1967, at a foreign policy conference for concerned American business executives, Johnson could thunder with confidence at critics of the domino theory that “Communist domination is not a matter of theory for Asians … Communist domination for Asians is a matter of life and death.”Footnote 65 After all, Lee had only weeks before appeared on the NBC (National Broadcasting Company) television program Meet the Press, wherein he had quipped darkly that if Vietnam collapsed, Thailand and Malaysia would succumb, which meant the communists would soon have him “by the throat.”Footnote 66

ASEAN leaders would find Nixon and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger just as eager to fill their quiver with whatever words from their Asian allies that could legitimize the Vietnam War. For example, the administration warmly welcomed Lee’s services as a “neutral” Asian leader who could publicly valorize US goals in Vietnam.Footnote 67 To the same end, Kissinger recorded on July 1, 1970 that Suharto’s officials expected the fall of South Vietnam would see all the ASEAN leaders but Indonesia racing to accommodate the Chinese.Footnote 68 Because Southeast Asian leaders had declared that they believed in the domino theory, Nixon had ammunition to deflect his opponents. In a television interview broadcast live on the same day that Indonesian leaders spoke with Kissinger, Nixon invoked the fact that ASEAN supported the Vietnam War, attacking his critics for not even having “talked to the dominoes … to the Thais, to the Malaysians, to the Singaporans [sic], to the Indonesians, to the Filipinos.” He stated that he, on the other hand, had been “talking to every one of the Asian leaders,” finding that all of them believed that the fall of South Vietnam meant that they “might be next.”Footnote 69

Of course, simply invoking the words of ASEAN leaders did not enable US leaders to overturn the groundswell of domestic and international opposition to the Vietnam War. For Johnson and Nixon, deploying the ASEAN leaders’ endorsements of the war was more about deflating critics than converting them. Indeed, Johnson and Nixon’s modus operandi was to repeatedly dismiss all critics of the Vietnam War by deriding how opponents of US military intervention in Indochina, safely removed from Southeast Asia, had no right to question ASEAN leaders’ genuine security concerns or their lived reality of the domino theory so proximate to Vietnam. These rhetorical flourishes bought time, if only a little, not for Southeast Asian regimes at risk of communist domination to gain stability, but instead to magnify the de facto US hegemony in the region already upheld by the pro-US ASEAN states.

Conclusion

Except in Indochina, the surge in Southeast Asian nationalism after 1945 had not ejected Western power from the region. Rather, anticommunist nationalists collaborated readily with the United States, which had adverse repercussions for Soviet and Chinese influence in the wider region. True, the Soviet Union could boast that its resources and guidance had enabled Hanoi to humble the United States. But apart from its alliance with Vietnam, Moscow from the 1950s onward had not lent significant support to other communist parties in the region. Soviet leaders had doubted that Southeast Asia’s other communist groups could succeed and, in the shadow of the nuclear arms race, sought peaceful coexistence with the United States. To enlarge the Soviet Union’s political presence in Southeast Asia, the Soviets instead nurtured relations with the region’s noncommunist nationalists who had (as Moscow anticipated) gained power by the late 1950s. This nondoctrinaire approach to the emerging Third World had some purchase with newly independent states of Africa and the Middle East but backfired in Southeast Asia. The region’s anticommunist nationalists had already picked the United States as their patron. Certainly, they traded with the Soviet Union, but their economic ties were more extensive with the United States and Western Europe. And when Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev sent feelers to ASEAN leaders in the late 1960s about assembling a Moscow-led regional security system, the proposal elicited no favorable response. Worse for the Soviets, most of Southeast Asia’s communist groups (besides the Vietnamese) had aligned themselves with China, disappointed by the Soviet Union’s neglect but inspired by Chairman Mao Zedong’s call to aggressive anti-imperial struggle.Footnote 70

From the late 1960s through the early 1970s, Soviet officials had become increasingly resigned to the fact that their influence had not advanced beyond Indochina. Even Soviet hopes of filling the vacuum left by Britain’s withdrawal from its bases in Singapore and Malaysia were dashed when both countries concluded a defense arrangement with Australia, New Zealand, and Britain. Furthermore, Malaysia and Singapore, like their ASEAN counterparts, fell squarely within the US orbit. Soviet diplomats would even divulge to American officials that they preferred the United States dominating the region so long as it precluded Chinese expansionism. No wonder, then, that when Nixon and Kissinger successfully executed rapprochement with China between 1971 and 1972, Soviet leaders felt compelled to pursue détente with the United States.Footnote 71

China’s policy toward Southeast Asia had fared little better than that of the Soviet Union while the Vietnam War raged and the US–ASEAN relationship deepened. Like the Soviet Union, China’s influence in the region was scant beyond the borders of Indochina. To be clear, China’s capacity to compete against US and British power in Southeast Asia had once seemed bright because of the PKI and Sukarno’s pro-China inclinations. But Suharto’s New Order abruptly ended China’s clout over Indonesian politics in late 1965. And it made little difference that other communist parties, such as those in Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines, ascribed to China’s revolutionary vision. In these three ASEAN states, pro-US factions had prevailed in the 1950s and remained firmly in control; in contrast, these communist groups had become terribly weak after muffed bids for power, or remained marginal entities without much political weight in their own countries.

Premier Zhou Enlai himself grasped the limited prospects for Chinese foreign policy in Southeast Asia. In March 1969, US intelligence officials learned that Zhou saw China “encircled” and “isolated.”Footnote 72 It is likely that Zhou perceived how deeply entwined ASEAN had become with other anticommunist and West-leaning multilateral organizations and security networks. When he was more at ease with Kissinger some years after their first meeting in 1971, Zhou shared how he believed that the “institutions” for containing China in Southeast Asia were “more numerous than any other area in the world.”Footnote 73 Adding to these frustrations for Chinese ambitions in Southeast Asia, years of Sino-Soviet rivalry had bloomed into violent confrontations in early 1969, while the excesses of Mao’s Cultural Revolution had decimated the nation’s political infrastructure and international reputation.Footnote 74 This combination of crises had crippled Chinese diplomacy. Once Nixon offered to thaw relations with China, Zhou and Mao knew that détente gave China a reprieve from fighting a losing battle against America.

Neither the failures of US policy in Vietnam nor the caving in of pro-US governments in Cambodia and Laos to local communist forces could stymie the rise of American hegemony in broader Southeast Asia. Nixon’s rapprochement with China, geared among other things toward reducing Cold War tensions in East and Southeast Asia, was undertaken from the position of US predominance in that very region. Before Lyndon Johnson Americanized the Vietnam War, anticommunist nationalists in Malaya, the Philippines, and Thailand had defeated their communist rivals, with British and US support, in the 1950s. Also, before US forces were even deployed to Vietnam, the creation of Malaysia in the 1960s led to the strangling of Singapore’s socialist movement and sparked the ill-fated Konfrontasi campaign which led to the downfall of Sukarno and the PKI. Thus, throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, the unstable anticommunist governments in South Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos proved striking contrasts to the overall rightward shift of Southeast Asia. In fact, Indochina’s slide toward communism bound the United States and ASEAN closer, with US economic and military aid extending the lifespans of ASEAN’s pro-US authoritarian regimes well past the end of the Vietnam War. As one senior ASEAN official reminded the international press in 1970, the broader region was not simply “Vietnam writ large.”Footnote 75