From the so-called “liberation of the South” (giải phóng miền Nam) in late April 1975 until 1989, Vietnam and its people encountered severe difficulties in practically every aspect – politically, ideologically, militarily, socially, psychologically, and economically. Arguably, the latter were the most serious and had the most debilitating impact on Vietnam’s people. In retrospect, several, often interrelated, factors contributed to this sorry state of affairs. It is impossible, on the one hand, to comprehensively describe, with any real justice, all of those factors and, on the other, ascribe the impact of each in a chapter of this nature. Accordingly, this chapter will briefly address the various reasons for the challenges experienced by Vietnam and its people in the period immediately following the end of the war before delving into and expounding upon the most critical among them.Footnote 1

The moment the war ended, the victorious authorities in Hanoi adopted a winner-takes-all attitude. A widespread slogan at the time, which was on the tip of the tongue of most officials from the North, was “ai thắng ai” (who is victorious over whom). Top party officials and policymakers justified this notion in ideological and theoretical terms as one of proving that “large-scale socialist production” (sản xuất lớn xã hội chủ nghĩa) through bureaucratic centralization would win in the battle against capitalism and its free-market system. They thus often ignored advice and analyses even from the Southern revolutionary leaders, dismissing some of the latter supposedly for insubordination while marginalizing many others. Lesser officials and bureaucrats from the North also tried to grab the lion’s share of victory in most areas.Footnote 2 They perhaps acted even more crudely than the carpetbaggers after the American civil war. All the while they were aided and abetted by hordes of Southern opportunists known as the “April 30 revolutionaries” (cách mạng 30 tháng 4).

Premature Reunification and “Socialist Transformation”

The communist-led military takeover of Saigon brought about policy responses by the United States in the subsequent weeks and months that tended to bolster the positions of regime hardliners in Hanoi. One of these responses was the recommendation on May 14, 1975, by US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to the US secretary of commerce, that the strictest trade sanctions should be imposed on Cambodia and communist-controlled South Vietnam, just as they had been on North Vietnam.Footnote 3 Another response was the veto on July 30, 1975, by US Ambassador to the United Nations (UN) Daniel Patrick Moynihan, of the applications for membership by the two Vietnams as two separate states. The uncompromising stance of the United States had the effect of strengthening the hand of hardliners in Hanoi who favored early reunification with the South. Only two months after the US veto of the two independent Vietnamese applications to the UN, the Party Central Committee declared at its 24th Plenum in September 1975 that Vietnam had entered a “new revolutionary phase.” The tasks at hand were as follows:

To complete the reunification of the country and take it rapidly, vigorously, and steadily to socialism. To speed up socialist construction and perfect socialist relations of production in the North, and to carry out at the same time socialist transformation and construction in the South … in every field: political, economic, technical, cultural and ideological.

The Resolution of the 24th Plenary Session of the Party Central Committee stressed that in order to carry out socialist transformation and construction in the South, the “comprador class” and the “vestiges of the colonial and feudal land systems” had to be eradicated. To this end, the resolution emphasized that the most important task was to establish and strengthen the party system and the “people’s administrative system.”Footnote 4

Lê Vӑn Lợi, a seasoned Northern diplomat, later explained the reasons the leadership in Hanoi thought it was necessary to speed up the unification of the country and to expeditiously carry out socialist transformation and construction in the South:

After the liberation, in the South the revolutionary government administration was not yet strengthened, the administrative system of the pro-American regime at the provincial levels and the grass-root levels in reality were not yet dismantled, and tens of thousands of bureaucratic and military officials of this puppet regime were not yet under control administratively. This is a condition that could not be prolonged. There was a need for the unification of the country in terms of governmental administration.Footnote 5

Since both the government in Hanoi and the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Southern Vietnam (PRG) in Saigon had often stated that they envisioned the reunification of Vietnam to proceed step by step over a period of twelve to fourteen years, and had shown confidence by submitting, in mid-July 1975, their applications for membership to the UN as two separate states, the view expressed above reflected a fundamental reassessment by the Hanoi leadership. It is difficult to gauge how much of this was based on newfound fears and how much was a justification for imposing Hanoi’s political and bureaucratic control. What was certain was that the conditions on the ground in the southern part of Vietnam, especially at the grass-root and provincial levels, could not have changed that drastically in a couple of months, since these were areas where the PRG had the strongest support throughout the war years.

In any case, in order to carry out socialist transformation and construction in the South, two programs were initiated: the first was “Transformation of Industry and Commerce” (cải tạo công thương nghiệp) and the other “Transformation of Agriculture” (cải tạo nông nghiệp). Party leaders perceived that the commercialization of the South’s rural economy, particularly production by the middle peasants, was tightly connected to the comprador capitalists (tư sản mại bản) in the urban areas. The term “tư sản mại bản” (literally, capitalists who sell the country) is borrowed from the Chinese term used during the Qing Dynasty (1636–1911) that referred to merchants and bourgeois manufacturers who traded with foreigners. Since this term has a negative connotation, its use in Vietnam during this period was probably meant to differentiate these people from the “national capitalists” (tư sản quốc gia) or “domestic capitalists” (tư sản quốc nội) for easier targeting and scapegoating.

Whatever the intention, the middle peasants produced large food surpluses in the South. If the government allowed them to maintain close ties with the capitalists in the urban areas, it would be difficult for the government to procure enough staples and other agricultural products to supply the urban population and the huge numbers of people in its administration and its military. According to a US Senate investigation, by 1972 South Vietnam had more than 10 million internally displaced “refugees” out of a total population of 18.5 million, mostly living in and around urban areas and refugee camps.Footnote 6 Therefore, transformation of the rural economy had to be tightly coordinated with the transformation of the private commercial and industrial sectors.

Before describing how the first program was implemented, it is necessary to mention the fact that many “comprador” bourgeois in Southern towns and cities were businesspeople who had given valuable support to the struggles for independence and freedom. This support included donating money to the revolutionary cause, providing lodging and residences to cadres and fighters, participating in antiwar movements, denouncing US intervention, and opposing the policies and conduct of the Saigon regime. After the war ended, however, most of those people who were still engaged in commercial and industrial activities became targets of the transformation program. This policy change was explained, both ideologically and theoretically, by the fact that the revolution had by now moved from the “popular democratic stage” (giai đoạn dân tộc dân chủ nhân dân) to the “socialism stage” (giai đoạn xã hội chủ nghĩa). This meant that the revolution had moved from the period of struggle for national independence, when the main contradiction was between the entire Vietnamese nation and foreign interventionists, to the period of domestic struggle between different classes in order to solve the question of “who wins over whom” between capitalism and socialism within Vietnam.

Armed with the above ideological justification, the Politburo ordered the Party Standing Committee to formulate a plan for attacking the comprador class, which was given the code name “X1.” This operation was carried out in two stages. The first stage started in the middle of the night of September 9, 1975, when ninety-two persons called “leading compradors” (tư sản mại bản đầu sỏ) were arrested. Forty-seven others were summoned for questioning, three escaped, and one committed suicide. Despite the scope of the operation, the amounts of money and valuables seized were meager according to the official inventory recorded at the time. For example, there was a total of: 900 million đồng of the former regime’s currency (1,000 đồng was equal to $1 in 1974, but by late 1975 the currency had become practically worthless); $134,578 (of which $55,370 were in bank accounts); 1,200 French francs; 135 Thai Baht; 7,691 taels (about 850 lbs) of gold; 4,000 pieces of diamond jewelry; 97 pieces of jade jewelry; and 701 watches of all types. In terms of other assets, the operation confiscated: 60,435 tons of fertilizer; 8,000 tons of chemicals; 3,031,000 meters of fabric; 229 tons of aluminum; 1,295 automobile tires; 27,460 bags of cement; 136 air conditioners; 96,604 bottles of brandy and wine; 2,000 pairs of eyeglasses, etc.Footnote 7

One wonders why the regime had gone through all the trouble and created such social, political, and psychological turmoil in order to reap such meager results. Either the inventories were faked by the cadres involved in carrying out the campaign or the “leading compradors” were really never that wealthy. In any case, perhaps because the high officials felt that they had not obtained what they thought they could, the second stage of the operation was carried out from December 4 to December 6, 1975. This time around the cadres managed to seize 288 establishments in total – of which 64 were in the industrial sector, 10 were agricultural, 82 were commercial, and the rest in other fields. The total value of all these assets was estimated at slightly above 31 million đồng, which was equivalent to about $10 million US by the official exchange rate at the time.Footnote 8 These numbers suggest that either there was asset-stripping or the properties seized were intentionally undervalued – or both.

As it conducted the two operations against the comprador class, the government carried out a program to send urban dwellers who were considered “nonproductive” – many of whom were merchants – to the so-called “New Economic Zones” (NEZs, vùng kinh tế mới) in rural areas that had been abandoned during the war years. Many displaced war refugees were also sent back to their former native villages. One of the main aims of this campaign was to relieve the urban areas of social, economic, and political pressures. According to the official records kept by the Committee of Party Historical Research in Hồ Chí Minh City, as Saigon was renamed shortly after the country’s formal reunification, “during the first 15 days of October 1975 more than 27,000 inhabitants of the city had returned to their native villages or gone to the New Economic Zones.” During the month of October 1975, “100,000 inhabitants of the city went to the rural areas to construct New Economic Zones.” By official account, “in less than 5 months after liberation about 240,000 inhabitants of the city had enthusiastically returned to their former native villages and gone to the New Economic Zones.”Footnote 9 It is quite a stretch to maintain that these people had “enthusiastically” done so. As this author witnessed during his six-month research trip to Vietnam over 1979 and 1980, thousands of people who had been sent to the NEZs flooded back to Hồ Chí Minh City and were living on the sidewalks because they had run out of food supplies and/or because unexploded mines and ammunition were still in the ground, injuring and killing many people there. Nevertheless, according to official estimates, by the end of 1975 nearly 6 million refugees in the South had returned to their native villages. This resulted in critical demands for land and severe land disputes in the countryside.Footnote 10

The “transformation of agriculture” was carried out differently in the southern half of the country from how it was in the northern half. Since most of the rural areas in the North had already been collectivized, the government’s plan was to consolidate village cooperatives so that “large-scale socialist production” could be managed and coordinated, presumably more efficiently, at the district level. In southern Vietnam, peasant households were first encouraged to become members of the “production collectives” (tập đoàn sản xuất), purportedly in order to get them used to working together before moving them to the higher cooperative levels. These members pooled their means of production (such as land, buffaloes and cows, farm implements, and other capital inputs) and worked together in “unity production teams” (đội đoàn kết sản xuất), each composed of forty to fifty people who cultivated an average surface of 30 to 40 hectares. The administrative committee of each team included the head administrator, who was responsible for overall management, and two assistant administrators, who oversaw the particular tasks involved in planting and harvesting, rearing livestock, and performing other production activities. The responsibilities of the administrators and team members were to make sure that the production plans of the households would be feasible and would together become the common production plan of the whole team that, in turn, would meet the goals set by the central government. These goals included meeting government procurement quotas at price levels set by the government, making sure that materials purchased from the government and services provided by it would be paid on time, and a host of other matters.

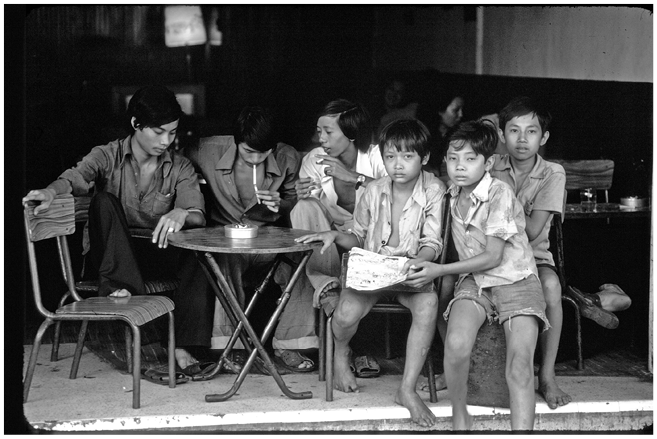

Figure 13.1 Young people sit in a coffee shop in Hồ Chí Minh City (April 20, 1980).

The “production collective” system in the south neither increased agricultural production nor food procurement for the government. Although in 1976–7 staple production (in terms of rice and rice equivalents) increased from 17 percent to 20 percent over the prewar years, this was mainly because of the redistribution of about 1 million hectares of land to the landless and the reclamation of about 1 million hectares of fallow land. Government food procurement (which included taxes and government purchases) actually decreased from 950,000 metric tons in 1976 to 790,000 metric tons the following year. Food production and procurement also suffered due to the escalating conflict with Cambodia and increasing tensions with China.

Impact of Conflicts with Cambodia and China

Beginning in January 1977, Khmer Rouge forces attacked across the Cambodian border into civilian settlements in six out of seven of Vietnam’s border provinces. Such attacks occurred again in April. The Vietnamese government decided not to retaliate at this point and instead sent a conciliatory letter to Phnom Penh proposing negotiations to resolve the border problem. The Khmer Rouge rejected this offer and continued with the attacks. In September and December, the Vietnamese counterattacked strongly, pulling back each time with an offer for negotiation. But each time Phnom Penh spurned the offer for talks and continued to attack Vietnamese territory, almost until the end of 1978. A reason for this intransigence on the part of the Khmer Rouge had to do with China’s aid and support. Between 1977 and 1978, China gave Pol Pot’s Cambodia several billion dollars in economic aid and supplied it with enough weapons to equip about 200,000 troops. An estimated 10,000 Chinese troops and technical personnel were also deployed to Cambodia to improve its military capability. During these two years of attacks, Khmer Rouge forces brutally murdered about 30,000 Vietnamese civilians, impelling tens of thousands to flee the border provinces. Many people in the NEZs abandoned their farmland and flooded back into Hồ Chí Minh City and other urban areas. Several hundred thousand Cambodian refugees also fled to Vietnam during those years.

In the face of these complicated developments, on April 14, 1978, the Hanoi Politburo issued Directive 43-CT/TW, which called for the vigorous “transformation of agriculture” in southern Vietnam. Collectivization had proceeded cautiously there, especially in the Mekong River Delta, until the beginning of 1978. But now the Party leadership was willing to take a gamble that, by getting the peasants into a collective framework, the government would be able to procure food more effectively in the effort to feed the burgeoning urban population and the armed forces. In response to the conflicts with Cambodia and China, some 300,000–400,000 men and women had by now been added to the various armed services, while hundreds of thousands of refugees had flooded into the cities. In 1980, the total number of people in the armed forces and in the urban areas was estimated at 11.5 million out of a total population of around 50 million. Another primary goal, similar to what had happened in 1975, was to relieve pressure in the urban areas by sending more of their inhabitants into the rural areas, where they could be isolated and controlled.

Connected to the goals mentioned above, the party leadership was now bent on an “all-out transformation policy” (chủ trương cải tạo triệt để) of the commercial and industrial sectors. In order to be able to do this, beginning in early 1978 leaders and cadres who had been involved in the transformation campaigns in 1975 were replaced. Nguyễn Vӑn Linh, the chair of the Transformation Committee for the South in 1975, was transferred to another position. On March 23, 1978, a secret campaign was carried out whereby all privately owned enterprises were simultaneously searched. All merchandise, raw materials, and means of production were confiscated. Large, privately owned industrial enterprises were transformed into “joint enterprises” (công ty hợp doanh), while smaller ones were organized into “production collectives.” Privately owned commercial enterprises were totally dismantled; meanwhile, small retail businesses were transformed into “service collectives” (tổ dịch vụ). Many merchants were sent to the NEZs to put fallow land under cultivation or to join production collectives. Only street vendors and manual laborers, such as bicycle repairers and barbers, were allowed to remain in the urban areas. A number of owners of large and medium-sized enterprises were arrested; many others fled abroad.

Hồ Chí Minh City was the focal point of the campaign, and an official report disclosed that 28,787 private commercial households were affected. Among them, 3,493 households were “deported” to rural areas. More than 2,500 households whose business enterprises had been dismantled, but whose members were later found to have been southern party cadres or strong supporters of the revolution, were allowed to remain in place and to work as government employees in various newly established enterprises slapped together from the privately owned ones that had been dismantled. In addition to the household members who were sent to the rural areas, 30,000 people fled abroad by various means.

Nguyễn Vӑn Trân, director of the Central Economic Institute when the campaign began, said later in an interview that the deportation of people to the NEZs was related to the belief by a number of top party leaders that, historically, the ethnic Chinese population of Chợ Lờn, a twin city of Saigon/Hồ Chí Minh City, had undermined the economic and political position of Vietnam for a very long time. Combining the transformation campaign with the deportation of a number of households from this area would prevent the return of some of these problems in the future. He added further that reliance on reports by unethical “April 30 revolutionaries” because of shortages of cadres on the ground caused distortions to the formation and implementation of the policies, thereby creating “extremely bad consequences.”Footnote 11

One of the “extremely bad consequences” had to do with the fact that, since many of the commercial capitalists were ethnic Chinese, this gave China the opportunity to accuse Vietnam of racial discrimination and thereby to terminate all aid and all trade by mid-1978. Trade with China had accounted for 70 percent of Vietnam’s foreign trade. Much of China’s aid consisted of consumer items, such as hot-water flasks, bicycles, electric fans, canned milk, and fabrics. Without these items, the government had little to offer the peasants for their produce in order to encourage them to increase production. China also increased the military pressure on Vietnam by shelling across Vietnam’s northern border on a regular basis. More significant still was the opportunity that the hardliners in Vietnam gave China to win over the hardliners within the US foreign policy establishment who wanted to use Vietnam for a proxy war against the Soviet Union. Since this would bring about huge problems for Vietnam and the whole Southeast Asia region for the next decade or so, a brief summary of the circumstances leading to this is necessary here.

While Vietnam was confronted by domestic difficulties and mounting problems in its relations with Cambodia and China, in the United States the Democratic Party had won the White House. After assuming the presidency, Jimmy Carter sought to improve relations with Vietnam for a number of reasons, including creating peace and stability in the Southeast Asia region. After a period of “feeling out,” the United States and Vietnam began a series of negotiations in May, June, and December 1977. During the first round of talks (May 3–4, 1977), the American side showed flexibility and suggested that the two sides should immediately establish diplomatic relations without preconditions. Other existing problems could be negotiated later on. The American delegation stated that the United States would not veto Vietnam’s application to be a UN member, but because of US laws Washington could not meet the promise stated in the 1973 Paris Agreement of giving Vietnam $3.2 billion “to heal the wounds of war.” However, the American side promised that after normalization of relations the United States would lift the trade embargo and consider humanitarian aid.

The counterproposal from the Vietnamese side was that the United States must accept a whole package, which included three items: (a) full diplomatic relations, (b) Vietnamese assistance in recovering American servicemen listed as missing in action (MIA), and (c) US reparations to Vietnam in the amount of $3.2 billion, as previously pledged by the administration of US President Richard Nixon. The biggest sticking point was the latter issue. During the second round of negotiations (June 2–3, 1977), the US delegation repeated its offer made in May. The head of the Vietnamese delegation, Phan Hiền, flew back to Hanoi and pressed for flexibility on the issue of aid/reparations, but the top party leaders would not budge. On July 19, 1977, the United States withdrew its veto on Vietnam’s UN membership as an indication of its good will before the third round of talks (December 19–20, 1977). At this third round of negotiations the American delegation suggested that if the two sides could not reach an agreement on establishing full diplomatic relations, then they could create Interest Sections in each other’s capital. In the latter case, the trade embargo could not be lifted right away. But Vietnam still insisted on the whole package that it had presented at the first round of talks.

On May 20, 1978, Zbigniew Brzezinski, President Carter’s national security advisor, went to China to discuss the normalization of relations between the two countries. The previous day, Deng Xiaoping, the “paramount leader” of China, was reported in the press as saying that China was the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) of the East, whereas Vietnam was the Cuba of East Asia. Given this development, it is not certain whether the top leaders in Vietnam still had any hope of normalizing relations with the United States. But for the next few months Vietnam offered, both publicly and through the offices of such countries as France, Sweden, and the Soviet Union, to drop the precondition for economic aid and promised to help the United States wholeheartedly in solving the MIA issues. On July 31, 1978, Vietnamese Premier Phạm Vӑn Đồng told an American delegation in Hanoi led by Senator Edward Kennedy not only that Vietnam had dropped the precondition for US economic aid in order to normalize relations with the United States, but that Vietnam also truly wanted to be a good friend of the United States.Footnote 12 Upon his return, Senator Kennedy called upon the US government to establish diplomatic relations with Vietnam, to lift the trade embargo against Vietnam, and to give Vietnam aid “according to the humanitarian traditions of our country.”Footnote 13 This was followed by meetings between US Assistant Secretary of State Richard Holbrooke and the Vietnamese foreign minister at the UN headquarters in New York on September 22 and 27, 1978, to discuss the normalization of relations between the two countries. The two agreed on normalization without any preconditions.

According to Brzezinski, on September 28, 1978, Secretary of State Cyrus Vance sent President Carter a report on the details of the agreement to normalize relations with Vietnam and recommended that normalization should proceed immediately after the congressional elections in early November. Brzezinski, a staunch Cold Warrior, strongly opposed this recommendation. According to Brzezinski, as of October 11, 1978, he had been successful in getting President Carter to drop the decision to normalize relations with Vietnam.Footnote 14 Instead, at the end of October 1978, “Vietnam was presented with a set of preconditions it could not possibly meet in the current situation.” Recognition, the United States now maintained, could not occur until three issues had been resolved to its total satisfaction: “the near-war between Vietnam and Cambodia; the close ties between Vietnam and the Soviet Union; and the continued flood of refugees from Vietnam.”Footnote 15

Fearing that the tough stance by the United States would encourage both Cambodia and China to stage a pincer attack on Vietnam, in early November 1978 Vietnam signed the Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union. On December 15, the United States announced normalization of relations with China. On December 25, Vietnam invaded Cambodia in order to preempt a pincer attack, claiming publicly that it went into Cambodia to save the Cambodian people from the genocidal Pol Pot regime. In late January 1979, Deng Xiaoping arrived in the United States for a visit and announced that China would “teach Vietnam a lesson.” He asked President Carter for “moral support” for the forthcoming Chinese punitive war against Vietnam. In his memoirs, Brzezinski disclosed his concern that President Carter would be persuaded by Cyrus Vance’s advice and would ask Deng Xiaoping not to use force against Vietnam. Therefore, Brzezinski stated that he did everything in his power to ensure that President Carter would support China.Footnote 16

Early in the morning of February 17, 1979, several divisions of crack Chinese troops simultaneously attacked Vietnam along the entire length of the northern border and went on to occupy Vietnam’s six northern provinces. Six divisions invaded Cao Bằng province, and three divisions were used against each of Lạng Sơn and Lào Cai provinces. It was widely reported that during their occupation Chinese troops reduced the six northernmost Vietnamese provinces to rubble and committed many atrocities. What is less known is the fact that after withdrawing from the said provinces, Chinese troops still continued to attack Vietnam across the northern border until 1989, causing much loss in lives and property. For example, the Battles of Vị Xuyên in Hà Giang province in April and May 1984 cost the lives of nearly 2,000 Vietnamese troops. From 1979 to 1989, China consistently refused to accept Vietnam’s proposals to hold talks to discuss the border issues, putting forth preconditions that included Vietnam’s total withdrawal from Cambodia and denunciation of the Soviet Union. Some of China’s top leaders even said publicly that they wanted to stretch Vietnam out and bleed it white as part of their proxy war against the Soviet Union. As a result, Vietnam had to maintain about 1.6 million soldiers for the defense of the northern and western borders.

The maintenance of such a large military force required increased supplies of food and materials. However, the “socialist transformation” campaigns in the rural and urban areas had already disrupted production capabilities and supply chains, creating severe shortages in food and in almost all other commodities. In the rural areas of the south, many peasants who refused to enter the collectives and the cooperatives left 1.8 million hectares of their land uncultivated out of a total of 7 million hectares in the entire country. Food procurement by the government, in terms of tax and purchases, decreased to 613,000 metric tons in 1979, as opposed to 1.1 million metric tons in 1976, 989,000 metric tons in 1977, and 716,000 metric tons in 1978.Footnote 17 Meanwhile, many former merchants and skilled workers from the urban areas who had been sent to the countryside to work in the newly established collectives did not have the means of production and the necessary skills to put the land under cultivation. Added to these problems was the fear that a prolonged war with China and with the remnants of Pol Pot’s army in Cambodia would bring about much more hardship and suffering. A combination of these and other factors led an increasing number of people in all regions of Vietnam to flee to other countries in search of safety and opportunities. The exodus from Vietnam during this period has been estimated at around 600,000 people. While many of these refugees encountered severe hardship and unspeakable tragedies, the exodus also created much criticism of Vietnam by other countries in the region, thereby contributing to its further isolation from the international community.

From Stop-Gap Measures to “Renovation”

Instead of reexamining the basic reasons behind the problems produced by the transformation campaigns, Hanoi embarked on a series of stop-gap measures to try to remedy them. For example, on November 18, 1980, the prime minister’s office issued the decree code-named 306-TTg ordering employees in all government offices and state-owned enterprises to go, by rotation, to rural areas about 25 to 30 miles (40 to 50 kilometers) in distance from the cities to put under cultivation land that the collectives and cooperatives had left fallow. Since government offices and enterprises had by now ballooned with employees who did not have much work to do, as a result of the transformation programs, it was not difficult to send them every month to the rural areas to till the land and raise livestock. The problem was that the costs involved in getting these government employees to these rural areas exceeded many times over the values of the things they could produce.

Stop-gap measures of this nature lasted for several years, in spite of courageous attempts by intellectuals and officials at various levels to voice their opinions on what they thought were the underlying problems. Many cadres were dismissed from their positions, while many independent intellectuals were driven to leave the country, since they realized not only that their interventions would not be listened to, but that their personal welfare would also be compromised. At the same time, however, the dire conditions in the country brought about a groundswell of resistance to the failed government policies and programs in every region and in most sectors of the economy. This grass-roots movement, which involved the participation of local inhabitants and officials both in rural and urban areas, lasted from 1979 to 1986, and had many ups and downs. This became known as a period of “fence-breaking” (phá rào) to indicate the efforts at tearing down the barriers that had been set up by the government at all levels to obstruct local and national development. Most of the time, however, these efforts involved subtle, indirect maneuvers to avoid direct confrontation with the authorities. In fact, the movement for renting out cooperative lands to household bidders for a certain agreed-upon percentage of the crops was initially called “sneak contracts” (khoán chui). Eventually, its name changed to “household contracts” (khoán hộ) and “two-way contracts” (khoán hai chiều). The overall effect was to force the central government to begin incrementally the process of reforms that culminated in the policy called Đổi mới (Renovation) in 1986.Footnote 18 But the real fruits of this change in outlook and policies only came after the withdrawal of all Vietnamese troops from Cambodia in the early 1990s.

Conclusion

After the so-called “liberation of the South,” Vietnamese leaders plunged Vietnam into more than a decade of difficulties on all fronts because of overconfidence, ideological steadfastness, and miscalculations. Domestic resistance and international pressures of various natures eventually brought about grudging changes that finally culminated in the reform process that opened up a new horizon for Vietnam and its people.