I have concluded, as the Assembly knows, within the time limit I’d set myself and with only a few hours’ discrepancy, agreements for the cessation of hostilities in Indo-China. A few days from now – and, in the principal sectors, very rapidly – blood will have stopped flowing, and we will no longer have the heart-rending thought that our young men are being decimated out there every day. The nightmare is over.Footnote 1

So began Pierre Mendès France’s July 22, 1954, speech to a packed Chamber of Deputies in Paris. The French prime minister was only five weeks into his premiership at the time. Not only that, but Mendès France had replaced his predecessor Joseph Laniel on June 13 with a dramatic pledge. He would resign in turn should he fail to negotiate peace in Indochina within a month. He just about made good on his promise, the final agreements at Geneva having been secured just two days earlier. Yet there was no triumphalism in Mendès France’s parliamentary statement.Footnote 2 The war in Indochina had cost 92,797 French Union lives.Footnote 3 For the first time almost 10,000 French Union troops had become prisoners of war of an anticolonial revolutionary regime.Footnote 4 Visibly exhausted, he instead justified his signature of a ceasefire with Vietnam meticulously, almost line by line.

It was significant that Mendès France felt the need not just to explain his actions, but to defend them as well. His speech culminated with a eulogy to the French garrison lost in the battle of Điên Biên Phủ in northern Vietnam less than three months earlier. Eschewing any mention of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN), the state that had inflicted that spectactular defeat on French forces, he instead focused on the garrison’s defenders, a high proportion of them colonial troops, doomed, but willing, even so, to sacrifice their lives for something beyond salvation. Mendès France’s listeners were left wondering: What was this “something”? Was it the garrison itself? Or France’s position in Indochina as a whole? Whichever the case, the deeper meaning conveyed was inescapable. The fight could not be won; it was time for France to leave.

Ironically, the defensiveness that Mendès France displayed regarding the Geneva Accords was echoed in the words of his adversaries. Just days earlier, senior leaders of the Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP) – the organization that controlled the DRVN state – gathered for the party’s 6th Plenum. Many listened with considerable skepticism as party founder Hồ Chí Minh and General Secretary Trường Chinh explained the terms of the deal that the DRVN had endorsed at Geneva. Some party officials criticized the acceptance of a temporary line of partition at the 17th parallel – a major concession that would force the DRVN to abandon large swaths of territory in central and southern Vietnam that it had controlled since the beginning of the war.Footnote 5 There was also dismay over the proposed neutralization of Cambodia, and likely also Laos. The communization of all of Indochina – a key VWP goal since its founding in the early 1930s – now seemed a more distant goal. The discontent with the Geneva Accords was also evident among the party’s rank and file. Lê Duẩn, the ranking VWP leader in southern Vietnam, faced difficult questions from cadres at a meeting in the Mekong Delta. Had the strategic advantage so hard-won at Điện Biên Phủ been squandered at Geneva? Why were elections on eventual Vietnamese unification postponed for fully two years? Why partition the country meanwhile at the 17th parallel when the DRVN controlled far more territory? Had the regime’s Chinese and Soviet patrons forced it to give so much away?Footnote 6

Unloved in France and vilified in much of Vietnam, it is tempting to conclude that the agreements to emerge from the Geneva Conference in July 1954 were fatally flawed. The impression is, of course, strengthened by our knowledge of their outcome: promised unification elections that never took place, a massive refugee flight, and the eventual outbreak of the “Vietnam War.” But this is to spy the Geneva Conference through the looking glass of America’s subsequent immersion in Vietnam. Although the Geneva Accords prefigured the eclipse of French colonialism in Southeast Asia, their decolonizing qualities have been obscured by historians’ focus on the postcolonial violence of the following decades.

If we take the failure of the conference for granted, we may overlook what its participants managed to accomplish. Painstakingly negotiated over four months, the Geneva settlement had two core elements. An “Agreement on the Cessation of Hostilities in Vietnam” concerned itself with immediate issues of stopping the fighting and enabling Vietnam’s people to move, either to places of safety in the short term or, in the longer term, to relocate permanently north or south of the partition line bisecting the country at the 17th parallel. The “Final Declaration of the Geneva Conference” addressed the country’s political future. It made provisions for national elections to be held two years hence, the victors of which would lead a national government in a unified and sovereign Vietnamese state.Footnote 7 Together these two settlements put an end to eight years of war between the French imperial state and their DRVN opponents.Footnote 8

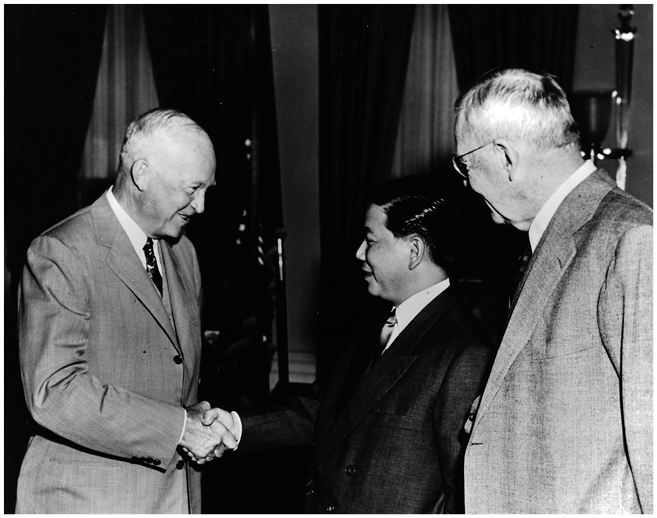

Much has been written about the Geneva talks (Figure 12.1), the agreements reached, and the ways they played out in practice. We now know a good deal more about those most directly involved in the negotiations, thanks to more extensive scholarship in Vietnamese sources, the release of additional Chinese and Soviet accounts of the conference, and continuing reflection on French, American, and other Western power reactions.Footnote 9 Diplomatic and social historians have also explored far beyond the conference hall to consider how Vietnam’s peoples, those most imminently affected by the Geneva arrangements, responded to war’s aftermath, whether as supporters of the victorious DRVN, as its opponents in the army and government of the French-backed State of Vietnam (SVN), as members of other militias and movements neither consulted nor reconciled to the conference outcome, or as refugees seeking sanctuary across the partition line.Footnote 10

Figure 12.1 Peace talks that led to the signing of the Geneva Accords (July 1954).

Embedded in this scholarship are attempts to explain why the Geneva settlement did not stick. However sensitive one is to the danger of reading history backward, it is difficult to evaluate the 1954 negotiations and their consequences contingently. It remains hard to capture the sense of expectancy for some, as well as the feelings of dread experienced by others. Yet it is only by grappling with the contingency and uncertainty that surrounded the events of 1954–5 that we can begin to understand the conference as something more than just an abject failure to head off the calamities that lay ahead. The significance of Geneva lay not only in what it portended about the future, but also in what it revealed about past patterns and practices.

Vietnamese and French Standpoints

Why did DRVN leaders agree to negotiate at Geneva, and why would they even consider a settlement that delivered neither total victory nor immediate unification of Vietnam under VWP rule? As Pierre Asselin has shown, the Hanoi regime doubted its capacity to impose terms without, in the process, provoking US intervention or forfeiting Chinese and Soviet goodwill.Footnote 11 Asselin’s astute analysis of the DRVN approach to the Geneva negotiations undermines the “standard total view” that Hồ Chí Minh and his comrades were compromised by dependency on their communist allies. Their Chinese partners, according to this view, were eager to consolidate Zhou Enlai’s success in breaking down the international isolation of the People’s Republic of China (PRC). And Beijing remained anxious at the prospect of VWP domination of the Indochinese peninsula. The Soviets, meanwhile, needed to build bridges to Paris to help ensure that France would reject the European Defence Community (EDC) project, at the heart of which stood a possible rearmament of West Germany.Footnote 12 These external pressures were real enough, Asselin shows, but the DRVN state faced other constraints much closer to home. Domestically, popular pressure for an end to the war was mounting, with calls for negotiations having become more insistent during late 1953. The DRVN regime was also internally divided between military supporters of an expanded war and civilian proponents of a compromise peace that would free the DRVN to enact socialist reforms.Footnote 13

As DRVN leaders estimated the optimal balance between domestic and diplomatic priorities, their rivals in the Saigon-based SVN were making their own calculations. On May 7, 1954, Bảo Đại, the former-emperor-turned-SVN-chief-of-state, signed off on a “National Salvation Front” aligning noncommunist nationalist parties with the Cao Đài, Bình Xuyên, and Hòa Hảo sects and their militias. Demonstrations in Saigon supporting a unified, noncommunist Vietnam sought to sway French and US opinion away from acceptance of partition.Footnote 14 It was to no avail. The delegation representing the SVN – soon to be rebranded the Republic of Vietnam under its newly appointed prime minister, Ngô Đình Diệm – found itself marginalized at Geneva. Never privy to the closed-session meetings between the conference’s principal international players, the SVN delegation at Geneva harbored no illusions about the proceedings. Above all, the settlement enabled France to withdraw, perhaps without even consulting SVN officials. Viewed from Saigon’s perspective, the accords left a vacuum that would be filled violently as Vietnam’s two regimes – and the rival political and religious movements and paramilitary groups within each of them – competed over the ideological complexion of a unified state.Footnote 15 Partition at the 17th parallel merely inscribed the initial battle line for an impending struggle: first, over unification; and second, over the nature of the social system to be constructed. The Republic of Vietnam, in other words, would have to live with the consequences of Geneva, but it accepted no responsibility for the settlement itself.Footnote 16

The fault lay, in part, with Geneva’s great-power players, but in larger measure with two other culprits. Between May and July 1954, Ngô Đình Diệm, both in his preparatory meetings with US diplomats in Paris and in his first public statements as SVN premier, was scathing in his criticism of the French. For Diệm, the half-baked Geneva accords were the logical outcome of France’s indecent haste to be rid of its obligations in Vietnam. In private, Diệm complained that the SVN’s inability to influence the negotiation process was the logical culmination of Bảo Đại’s decision to collude with French colonialism, thereby compromising Vietnamese national interests.Footnote 17

Pierre Mendès France shared Diệm’s low opinion of the so-called “Bảo Đại solution” of limited Vietnamese political autonomy, but he could hardly concede that the French war effort was entirely futile. Equally difficult to admit, Bảo Đại notwithstanding, was that Franco-SVN forces had almost broken the communist resistance in Vietnam’s far south. Only on the eve of withdrawal did France finally abandon its nationalist paramilitary partners, the Cao Đài, Hòa Hảo, and the Bình Xuyên.Footnote 18 If there was a studied ambiguity in his July 22 parliamentary comments about the value of a Franco-Vietnamese connection, there was more assertiveness in his portrayal of the Geneva Conference Accords. Here, Mendès France had placed himself at the heart of the drama. The text of the accords was “cruel” because the arrangements they consecrated were devastating, namely the division of Vietnam. But facts were facts: there was no alternative. The French Expeditionary Corps in northern Vietnam faced mounting losses. Negotiating a ceasefire, while, at the same time, rushing out the required additional troops, was not just the rational choice, it was the ethical one. Only now, with the diplomacy done, could Mendès France reveal how desperate the French military position had been.Footnote 19

During military talks in early June with DRVN commanders over prisoner-of-war exchanges, it had become apparent that Hồ Chí Minh’s government was receptive to a more general peace agreement. Jean Chauvel, personal envoy to Mendès France, was immediately instructed to seek clarification from the DRVN’s lead negotiator, Phạm Vӑn Đồng. In Mendès France’s retelling, it was then a matter of standing firm against excessive Việt Minh demands. Identical agreements, not just for Vietnam, but for Laos and Cambodia as well, were rejected. Such an arrangement would have seen all three countries temporarily partitioned, their northern sectors placed under Việt Minh or pro-Việt Minh administrations, an obvious precursor to communization of all of Indochina. Proposals for an immediate French evacuation followed by national elections only six months after a ceasefire were also turned down. In their place, Mendès France’s team secured a manageable 300-day deadline for reciprocal troop evacuations and a two-year timetable for Vietnam-wide elections.

The result was a workable peace accord and a symmetrical one. For every Franco-South Vietnamese concession, there was a DRVN quid pro quo. The embodiment of this reciprocity was the free movement for all Vietnamese across the partition line. French negotiators, Mendès France suggested, had dug in hard over matters of genuine human consequence. France could depart Vietnam with a clear conscience, focusing instead on matters of more proximate interest: the EDC talks and, above all, the export drive needed to secure future French prosperity.Footnote 20 Mendès France’s underlying message was obvious. He had salvaged meaningful concessions from a weak military position. He had saved France from a crippling economic and military burden. And he had ensured that noncommunist Vietnamese living in the North could escape direct rule by Hanoi. It was a judgment echoed by René Moreau, French envoy to Saigon, who declared that Mendès France’s Geneva diplomacy had “saved the Expeditionary Force from complete disaster.”Footnote 21 Another month of fighting and Hanoi might have fallen, triggering civil war among southern anticommunist forces.Footnote 22 By implication, Phạm Vӑn Đồng’s team had frittered away their strategic advantage.

Heralded by some signatories as a remarkable peace negotiation, the Geneva Conference Accords remained highly provisional. Their fulfillment remained a matter of doubt, uncertain in the turbulent local and international climates of July 1954. Implementation of everything, from French military evacuation and refugee resettlement in the first instance, to peaceful elections and eventual Vietnamese reunification in the second, hinged on the American response, whether that be reluctant acquiescence or active sabotage. Walter Bedell Smith, Under-Secretary of State and official US delegate at Geneva, signaled that Washington “took note” of the accords, but most recognized even this as merely contingent. Much would rest on the complexion of Ngô Đình Diệm’s regime, still more on its effectiveness in channeling American anticommunism.Footnote 23 This is neither to impose a crude model of US hegemony on the Southeast Asian situation nor to deny agency or signal importance to the actions of the Vietnamese and others. It is simply to state the obvious: of all the conference participants, it was Eisenhower’s administration that was the most poorly reconciled to the outcome.

Certainly, French negotiators had extracted more than they thought possible when the conference opened in late April.Footnote 24 At that point the Điện Biên Phủ garrison, ravaged by successive DRVN assaults since March 13, was close to surrender. Daily media coverage, punctuated by stirring accounts of heroism and sacrifice in the press, increased the pressure on Mendès France’s negotiating team to secure an honorable peace – but a peace nonetheless. The domestic public was tired of the war. Some were traumatized by it; many more were bored with it. The French Union seemed set to disappear anyway, so why persist with the fiction that it might yet endure in Vietnam? A protracted conflict as manifestly colonial as it was remote, the French Indochina War failed to stir the public passions of the looming confrontation in Algeria. Settlers to Vietnam were few in number, too few to constitute a discrete political constituency or a powerful cultural symbol.Footnote 25 Their ability to sway distant compatriots, whether through literary and other artistic production or by direct political appeal, was commensurately limited. Conscripts and celebrated Metropolitan Army regiments played no part in the fighting, much of which fell to colonial and, increasingly, to SVN forces.Footnote 26 But the anxiety persisted that an unending war might yet require the blood of national servicemen.

Among the major French political parties, the Gaullist Rassemblement du Peuple Francais (RPF) had argued most fervently for a greater military effort. But even de Gaulle’s fervent supporters stopped short of suggesting the use of conscripts. De Gaulle himself made no secret of his contempt for Bảo Đại’s administration, a fading regime that, in Gaullist eyes, mirrored the ineffectiveness of the Fourth Republic.Footnote 27 Other senior RPF figures viewed any additional military commitment as a diplomatic lever, as a means to negotiate from strength. Indeed, the eponymous military plan of General Henri Navarre, commander of French forces in Indochina, had by 1954 been reinvented as a tool of defensive attrition that would ensure the DRVN paid the highest price possible for any strategic gains.Footnote 28

It had all been rather different four years earlier, when US aid deliveries began to flow over the spring of 1950. At that point, French policymakers concluded that there was simply no alternative to fighting on with the United States’ backing. The recently signed Hạ Long Bay Accords committed France to do so. Many Vietnamese would feel justifiably betrayed should France abandon them. And Southeast Asia would be left so chronically exposed to communist incursion that a wider conflagration was probable. The conclusion reached was peculiar. France, it was argued, should prosecute its limited war in Vietnam to prevent a bigger one.Footnote 29

By late 1953 every element in this bizarre logic had been reversed. Both the Fourth Republic’s most virulent internal critics and its senior strategic planners were, by then, convinced that peace talks made sense.Footnote 30 During a National Assembly debate on Indochina in late October, Socialist Party figures baited Joseph Laniel’s center-right coalition with the accusation that the government had surrendered France’s strategic independence to the United States. With the Korean War now concluded, what was to stop Washington from demanding a larger French commitment in Vietnam? If, as Laniel insisted, the war was still worth fighting, then surely more soldiers would be required? For what? Ostensibly, the French war effort was meant to induce the DRVN to seek terms – in which case the French would probably negotiate much the same peace arrangements as if they had sought negotiations first. Laniel’s refusal to parley with the DRVN was not the result of careful strategic evaluation; it was partisan stubbornness. For the socialists there was no reason to disbar Vietnamese independence anyway, as long as fair elections were held after a ceasefire.Footnote 31

The calculus of French lives at stake formed part of a broader equation in which monetary investments had also depreciated.Footnote 32 French business owners and investors began transferring south or relocating offices and funds to other, safer francophone territories long before the Geneva talks began.Footnote 33 Ironically, the gathering perception that, ultimately, the war in Indochina was not essential to France was, if anything, reinforced by the depth of the United States’ pockets. Washington’s commitment to provide money and materiel for the expeditionary force added to the impression of a war dislocated from other, more proximate French concerns. An important side-effect of France’s loss of unilateral control over the war’s direction was to relegate the conflict from the stature of a national emergency to that of a peripheral conflict: devastating certainly, but not above the fray of interparty dispute and the vitriolic debate over the Fourth Republic’s system of coalition government. The war in Indochina, in other words, was something it was okay to question, to criticize, and, ironically, to ignore.

But even if the war was increasingly something that metropolitan French politicians were prepared to set aside, the peace agreement negotiated at Geneva was something else entirely. For the French officials who still wielded considerable power over Indochinese affairs, as well as for their Vietnamese counterparts, the difficulties associated with making peace in Indochina would be at least as daunting as those associated with waging war. The most immediate challenges lay in securing and monitoring the proposed ceasefire, as well as the authorized movements of military personnel and civilians in both directions across the 17th parallel. Following suggestions from Soviet and Chinese officials, the negotiators had assigned these crucial duties to a tripartite International Control Commission (ICC) headed by India in partnership with Canada and Poland.Footnote 34 Everyone expected that the new commission had its work cut out for it. But almost no one anticipated the controversy that would almost instantly envelop the ICC – or how the implementation of the accords would provide new opportunities for critics to attack it.

Monitoring Geneva: The International Control Commission and Refugees

Among the many issues left hanging by the Geneva Accords, the means to enable the promised free movement of people across the partition line aroused the fiercest international criticism. This was especially true in the United States, where the plight of more than 800,000 Vietnamese refugees seeking to leave the Việt Minh-controlled North became emblematic of all that was allegedly wrong with the settlement. The fact that most of these northern refugees were Roman Catholics, plus the apparent need for US naval and air transport to ensure their safe passage, lent weight to the image of an American mission of mercy to save the largest postwar tide of refugee humanity in Southeast Asia from death or persecution at the hands of a ruthless and godless communist regime. Garish, sensationalist accounts in the American Catholic press of Catholic villages destroyed and defenseless refugees mown down by communist machine-guns were, in turn, encouraged by a CIA campaign of misinformation and propaganda. In the hands of Colonel Edward Lansdale’s notorious psychological warfare operation designed to delegitimize the Hanoi regime ahead of the planned elections on Vietnamese unification in July 1956, the Vietnamese refugee crisis was instrumentalized to confirm the moral bankruptcy of the Geneva settlement.Footnote 35

Less well known to Western publics were the DRVN regime’s persistent accusations that the departing French authorities were forcing populations to move southward whether through direct coercion, forcible transfer, or intense psychological pressure. Central to this last were misleading threats about the VWP’s elimination of alleged traitors and dire warnings of imminent US atomic bombing of North Vietnam.Footnote 36 The DRVN government also accused the French government of complicity in the US propaganda campaign, notably in regard to systematic killings of Catholic villagers and their priests. One such case was that of Ba Làng, a fishing community in Hải Thanh district, where initial accounts of a massacre in March 1955 were soon exposed as a fabrication.Footnote 37

The doomsaying may have been overblown but there is no disputing the fact that the bulk of refugees’ petitions submitted to the ICC came from practicing Catholics, Buddhists, and other minority groups who faced victimization under the communist regime.Footnote 38 In addition to reports of village massacres, police shootings, and mass arrests were more prosaic but no less revealing accounts of punitive DRVN taxation and regime discrimination against smallholders fearful of imminent collectivization.Footnote 39

Logically enough, the ICC remit was extended to cover supervision of refugee exchanges. Here, though, we get to the nub of things. For the ICC was not armed with any peace enforcement powers. Aside from adverse publicity and moral sanction, it had no means to ensure compliance with the Geneva Accords.Footnote 40 ICC monitors quickly became embroiled in investigating, not just minor ceasefire breaches but alleged massacres of civilians and other major human rights violations.Footnote 41 ICC personnel were also intimately involved in evacuation arrangements, including the final French withdrawal from Hanoi.Footnote 42 For all that, the effectiveness of this oversight regime rested on the self-restraint of the major parties involved rather than any threat of sanction were the Geneva Accords to be violated.Footnote 43 There were some promising signs. The departing French and the victorious Việt Minh seemed genuinely eager to mend fences. Talks on prisoner of war releases and other war-related disputes were well underway by September 1954.Footnote 44

Remarkably, on November 5 General Giáp told France’s ICC liaison that the two countries shared equal responsibility for the violence of the preceding war.Footnote 45 Hồ Chí Minh echoed the sentiment, albeit in less mathematical terms, in an interview with Agence France Presse five days later. Eager to bury the hatchet, the Vietnamese leader spoke effusively about a rapid resumption of Franco-Vietnamese commerce, deeper cultural exchanges, and the normalization of diplomatic relations, all of which, he admitted, would help offset domineering Chinese influence in northern Vietnam.Footnote 46 Phạm Vӑn Đồng told French envoy Jean Sainteny much the same on November 13, focusing in particular on the need for French economic aid.Footnote 47 This soothing rhetoric also had substance. The DRVN’s nationalization of key French industrial assets notwithstanding, there was a reciprocal willingness to see economic activity resumed, ambassadors exchanged, and other transitional arrangements made.Footnote 48 Unfortunately, this bilateral reconciliation was soon overshadowed by the deepening animosity between the two Vietnamese states.Footnote 49

Here was the ICC’s Achilles heel. The peacekeeping apparatus of the Geneva Conference was stretched beyond its tensile capacity because Vietnam’s two competing regimes viewed the ceasefire accords and consequent monitoring arrangements as functional preludes to the resumption of conflict over the country’s unification. This struggle might be pursued politically at first, but the readiness to use force was obvious. Indeed, Diệm’s SVN government pointedly refused to endorse the Geneva Accords at all.

Central to Diệm’s eagerness to transform the erstwhile SVN into a postcolonial republic was the desire to break any vestigial ties with France, clearing a path to closer strategic alignment with Washington.Footnote 50 Noncooperation in Saigon might have been less damaging had there been stronger unity among Geneva’s external sponsors. But the Geneva powers lacked both the unity and the political volition to see the accords through to their conclusion. The Soviets and British had other European and imperial priorities. And the French, as we have seen, were desperate to focus their strategic efforts and budgetary spending closer to home. Conscious of Washington’s frustration at France’s recent definitive rejection of the EDC, no government in Paris was likely to insist on by-the-letter adherence to the Geneva Accords. The Chinese seemed more committed. Their 200-strong delegation to Geneva that took up residence at Versoix’s Grand Mont-Fleury estate in late April 1954 underlined the PRC’s commitment to an agreement on Indochina.Footnote 51 Yet, for all its advocacy of “peaceful coexistence,” the Chinese government still sought to exploit division between the United States and its Western allies.Footnote 52 The resulting double-edged strategy would be evidenced in 1954–5 by confrontation over Taiwan versus conciliation at Bandung.Footnote 53 Next to this, ensuring that the Geneva terms were upheld was a secondary concern. Meanwhile, closer US strategic alignment with Chiang Kai-shek’s regime in Taipei further reified the Washington orthodoxy that Geneva was a rotten deal.Footnote 54 In simple terms, from London to Beijing consensus was lacking over enforcement of the Geneva Accords – and over the making of peace.Footnote 55

A Failed Settlement?

From this lack of consensus, historians have deduced two underlying reasons for the ultimate collapse of the Geneva settlement: Cold War friction and US hostility. Analytically, however, neither of these takes us very far. The East–West divisions were present before the conference as well as after it. Geneva, if anything, is usually depicted as a brief moment when dialogue trumped confrontation. Numerous studies highlight the effective working relationships nurtured across ideological lines during the conference. Admittedly, much of this bonhomie concealed ulterior motives, such as Soviet efforts to ensure French rejection of the EDC or Chinese attempts to secure wider diplomatic recognition. But so what? Conference diplomacy, whether stimulated by crisis as in Geneva’s case or part of a cycle of transactional foreign policy, enables nation-states to pursue their interests alongside more lofty goals of peacemaking or norm-setting.Footnote 56 The formal agreements that such conferences produce may thus be only a part of the multiple diplomatic purposes served.

The peculiar circumstances of spring 1954 were indisputably conducive to diplomatic bargaining. Moscow’s leaders seemed anxious to build bridges to the West in the aftermath of Stalin’s death a year earlier.Footnote 57 Meanwhile, Geneva offered Beijing the opportunity to cement its putative, if conflicted, role as both the leading power in Asia and an authentic voice of radical anticolonialism.Footnote 58 More generally, multiple participants were anxious for the meetings to conclude on a positive note. The Geneva Conference, it should be remembered, began months before the matter of peace in Indochina took center stage. And it had not been going well. The absence of any definitive agreement over Korea’s long-term political future created pressure to achieve something definitive over Indochina. The British, the Soviets, and the Americans, albeit for different reasons, did not want France to leave the conference humiliated and resentful. Indeed, in the short term at least, resentment was perhaps most keenly felt in Washington, not Paris or Hanoi.

Turning to US hostility: here we must consider the agreement’s normative implications in the mid-1950s. The principal victors of World War II, each represented at Geneva, had by 1954 arrived at a form of political peace that, in the aftermath of the Korean Armistice, looked more stable than previously. While certainly not predicated on mutual affinity or lasting geopolitical stability, this fragile peace had thus far prevented another global conflagration. In place of devastating and potentially atomic direct confrontation, proxy conflict was becoming the norm.Footnote 59 Such wars would be fought mostly in what Mao Zedong identified as the vast “intermediate zones” of Asia and Africa, amidst the remnants of European colonial collapse.Footnote 60 The PRC, according to Mao, should play a decisive role in this decolonizing world.Footnote 61 But the normative standard intrinsic to proxy war was that rival sponsors should not directly come to blows.Footnote 62 In this respect, Korea had been a near miss. It is worth remembering that most of Korea’s war dead were civilians, counted in the hundreds of thousands. A large portion of these were the victims of US aerial bombardment.Footnote 63 And yet, barely a year later, elements within the Eisenhower administration seemed ready to do it all again, to intervene not just as proxy backers but as direct combatants in Indochina. John Foster Dulles, Admiral Arthur Radford, and their fellow hardliners, in other words, were prepared to contemplate conflict escalation.Footnote 64 This was a potential normative breach of what would become the unwritten code, not just of Cold War peacemaking but of war-making in the Global South as well.Footnote 65 From this perspective, the fact that the agreements were concluded and that Washington felt obliged to stand down and “take note” of the results can be counted a significant success, even in hindsight.

Decolonization and Geneva

Instead of treating the conference solely as an event in East–West relations (or as an episode in US Cold War foreign policy) we would do better to place it within broader transnational currents. The Geneva Conference laid bare influential markers of North–South divisions including racial discrimination, Western incomprehension of the cultural economies of peasant society, and insensitivity to the acute economic hardships that nurtured support for the Việt Minh. Mention of these structural forces places the Geneva settlement in a subtler light as part of a larger Asian decolonization.Footnote 66 Viewed from this perspective, the motivations of key actors seem rather different. The DRVN’s burning desire to be rid of their colonial occupiers mirrored the sentiments uppermost among rural cultivators desperate to see meaningful land redistribution enacted.Footnote 67 The resultant compromises made at Geneva also evoked the regime’s readiness eight years earlier to do all that was necessary to hasten the evacuation of Chinese Nationalist occupation forces from northern Vietnam.Footnote 68 The close attention paid to the conference proceedings among other decolonizing Asian nations and India’s pivotal arbitral role at Geneva also prefigured the articulation of the doctrine of nonalignment by these same countries one year hence at the May 1955 Bandung conference.Footnote 69 The Five Pancha shila Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, a statement of the core ideas of nonaligned international politics enunciated by Jawaharlal Nehru and endorsed by Zhou Enlai on April 29, 1954, lent force to what the Indian premier had previously described as the two “strongest urges” in the new diplomacy of South and East Asia: a nationalist rejection of foreign intervention and an anticolonial loathing of racial discrimination.Footnote 70 In Jason Parker’s tidy formulation, during 1954–5 the interrelatedness between decolonization and Cold War altered fundamentally. Decades of race repression gave way to a new era, post–Geneva and post–Bandung, of race liberation.Footnote 71 The United States’ determination to build a broader Southeast Asian anticommunist alliance, although crowned by the creation of the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) in September 1954, exposed its deeper ideational divide from Asia’s anticolonial, nonaligned states.Footnote 72

Perhaps, then, it was little wonder that French and British representatives at Geneva proved more willing than their American ally to parley deals with the Chinese, Soviet, and, ultimately, the DRVN delegations. If the Eisenhower administration was struggling to adjust to the nonaligned, anticolonial turns of Asian geopolitics, its Western partners were confronted with a different transition of power. Although reluctant to acknowledge matters in these terms, the old European colonialists had already ceded regional hegemonic imperial power to the United States.Footnote 73 Geneva, in other words, was a facet of a longer-term process of European decolonization in Asia.

For France, leaving Vietnam was the culmination of a phased withdrawal that began in earnest with the Hạ Long Bay Accords. These arrangements conceded limited sovereign rights to Indochina’s Associated States, albeit within the confines of the French Union. The ministry set up in July 1950 to handle relations with the Associated States anticipated an eventual transfer of institutional control. Arguably, the ministry had other purposes entirely. For one thing, it was guided by Jean Letourneau, a colonial hardliner determined to maintain the connection between the Associated States and their French political masters. His ministry pursued this objective both as an end in itself and as a means to sustain the wider French Union project. If Indochina’s Associated States severed ties with France, then why shouldn’t Morocco, Tunisia, even Algeria, follow suit? The Ministry also aimed to improve civil–military coordination over the war’s conduct in the aftermath of the 1950 French defeat at Cao Bằng.Footnote 74 Nevertheless, it was inarguable that France, whether by accident or design, was loosening its grip on Indochina. Indeed, when framed as instruments of French decolonization and a device for colonial extrication, the Geneva Accords emerge not as a failure but as a striking success.

Geneva, then, was part of a decolonization process that would take decades more to complete. The totality of that decolonization is not our primary concern here, but the nature of the process profoundly impacted Vietnam’s transition from one conflict to another. Two points bear emphasis. The first is that Indochina’s colonial constitutional architecture, formally dismantled after Geneva, was a hybrid construction. It was, in part, a semiautonomous confederation with the two outlying polities of Laos and Cambodia uncomfortably welded to a warring Vietnamese colonial center. Yet it was also a more instrumental device, colonially designed with a specific ulterior motive: to block Vietnamese communist domination of the Indochinese peninsula. Hardly surprising, then, that separate peace agreements would be signed at Geneva for Laos and Cambodia, the relative straightforwardness of which underlined the artificiality of their juridical connections with Vietnam. The Indochina Federation, its constitutional sophistry notwithstanding, was also a classic late colonial state, one whose eventual demise was anticipated, even planned for, by its architects.Footnote 75 Yet, this point requires further nuance. There is a big difference between anticipating decolonization and hoping that Indochina’s Associated States would still agree to remain affiliated with the French Union. Here, French planners would be quickly disappointed, as Geneva ushered in full independence for Cambodia and Laos and a postcolonial republic in South Vietnam.

The second point has to do with the politics of imperial exit. A negotiated settlement to end a colonial conflict, to permit a more or less orderly imperial withdrawal, and to impose a partition supposedly as a temporary expedient, but potentially as a lasting barrier to peace, was far from unusual. The British had done something similar in Ireland, securing a partial peace in 1921 that facilitated their withdrawal, but hardened the Ulster partition and left the messy details of a final treaty settlement to unravel amidst an Irish civil war. The violence and displacement of partition serving as a prelude to wider war was an unhappy sequence that was repeated twice in the late 1940s, first in the Indian subcontinent, months later in Mandate Palestine.

Taking a longer historical view, other premonitions and echoes of Geneva might be found. Dwell for an instant on the conditional arrangements made at Potsdam for transitional military administrations within a partitioned Vietnam. Recall the United States’ decisive influence, first in promoting decolonization talks in Indonesia, then in turning against the Dutch hardliners who resisted Washington’s preferred outcome. Or telescope twenty years forward to the pullouts from Lusophone Africa negotiated by Portugal amidst its Carnation Revolution of April 1974. A sclerotic Lisbon regime overwhelmed by Cold War internationalization of its contested decolonization was replaced by an infant democracy desperate to be rid of colonial conflicts that were spiraling into calamitous civil wars in Angola and Mozambique. Each of these cases was circumstantially contingent and historically unique. But certain familiar features – a febrile metropolitan regime, decisive external pressure, and proxy war – can be glimpsed in each.

Digging a little into the defining characteristics of late colonial states helps unearth the colonial dynamics played to their conclusion at Geneva in 1954. Founded on the notion of a phased French withdrawal and political, economic, and cultural partnerships with the metropole, the Associated States of Indochina were, in French parlance at least, no longer a colonial domain but rather a field of experimentation. In simple terms, the late colonial state would no longer be required once its political offspring were deemed capable of surviving alone. French forces were fighting to clear a path for Indochina’s component polities to build their independence on the foundations laid by the late colonial state: limited monarchy, gradual democratization, the embrace of French values and administrative practices. Herein lay the essential contradiction at the heart of such arrangements. For the judgments involved were entirely subjective: a reflection of abiding imperialist thinking about societies at differing developmental stages rather than any definitive recognition that empire had had its day. In this conceptual schema – perhaps more like an absurd parallel universe to those living through the everyday violence of the Indochina conflict – the war was being fought, not to prolong the French presence but for a new politics to keep Southeast Asia within a Western orbit, free of communist influence. Intrinsic to this worldview was an insistence upon the unrepresentative nature and consequent illegitimacy of the Hanoi regime. Coming to terms at Geneva thereby marked a fundamental ideational departure for France. The country’s rulers at last acknowledged the DRVN as the authentic voice, not just of Vietnamese socialism, but of Vietnamese national aspirations as well.Footnote 76

Conclusion

Seen from the vantage point of decolonization, Geneva was of a piece with adaptations made by late colonial states unable to mitigate their declining position. Although determined to cling on in Algeria and elsewhere, few French decision-makers could dispute the logic of Mendès France’s pursuit of negotiated withdrawal from Vietnam. In these more fluid circumstances multilateral diplomacy provided the necessary cover for exhausted imperial powers to quit. For all that, the Geneva Conference could be viewed very differently: as a logical compromise for a DRVN regime anxious to rebuild at home, as a victory of pragmatism for French negotiators playing a losing hand, and, more broadly, as a curtain-raiser for radical nonalignment and the rejection of rigid Cold War loyalties by the decolonizing Global South.

In hindsight, France’s generals were proved right: seizing Điện Biên Phủ was a superlative achievement for the DRVN, but it was still less than outright victory. This returns us to the question of why DRVN leaders chose to negotiate at Geneva in the first place. In part, the conference heralded the emergence of a new type of diplomacy, one in which the transnational mobilization of anticolonialist sentiment would cut across the neat dividing lines of Cold War ideology. But in other respects, the Geneva settlement was more familiar: a classic holding action in which the dominant external actors agreed to disagree in an effort to contain the regional fallout from another contested decolonization. In this respect, the Geneva Accords accomplished their short-term task. Few doubted that the settlement was unsustainable in the longer term. But that was a tragedy yet to unfold.

Introduction: Vietnam as a Cold War Domino

For “the big picture” boys in Washington, Vietnam in the 1950s was primarily a piece on a global game board. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had inherited from his predecessor the grand strategy of containment, which had set the rules of the game. The explicit objective of this strategy was to limit the expansion of Soviet power and influence everywhere in the world, including in the faraway country of Vietnam. By 1954, however, Eisenhower had begun to grasp that Vietnam was no ordinary pawn. Although he famously characterized the Southeast Asian country as a domino – literally a game piece that might topple over and set off a chain reaction involving other nations – the outcome of the Geneva Conference that summer showed that Vietnamese actors were important international players in their own right. In the aftermath of the conference, Eisenhower confronted the problem of a pawn that seemed not to be following the rules.

In November 1954, Eisenhower dispatched his trusted friend and World War II colleague, General J. Lawton Collins, to South Vietnam. Significantly, Collins was given status equivalent to an ambassador, but was officially designated the president’s special representative. Colonel Edward Lansdale, an American who had arrived in Saigon a few months ahead of Collins, quickly concluded that the general’s understanding of Vietnam was lacking:

Collins was from the world of “the big picture,” the top management circles of Washington with their necessarily simplistic view of the complex problems of the world … To apply this picture to what then existed in South Vietnam, where a small group of [American] bureaucrats in Saigon … issued orders mostly to one another in tragic ignorance of what was happening beyond the suburbs, could only lead to faulty judgments.Footnote 1

For Lansdale, Collins’ insistence on viewing Vietnam in geopolitical terms was flawed because it overlooked the importance of mobilizing local support for US policies among Southeast Asian anticommunist nationalists. Lansdale, a former advertising agent who now worked for the CIA, considered himself an expert on how to carry out such mobilizations at the “rice roots” level in countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines.

But the differences between Collins and Lansdale should not be overdrawn. After all, both men had been sent by the Eisenhower administration to try to “save” South Vietnam from communism, and both were equally ignorant of Vietnamese history, politics, and culture. Instead of understanding Collins and Lansdale as polar opposites, they are more usefully understood as exemplars of the two primary themes underpinning Eisenhower’s approach to Vietnam. On the one hand, US officials situated Vietnam explicitly within the grand strategy of containment. On the other, American perceptions of Vietnamese actors – both allies and adversaries – were steeped in racist and patronizing assumptions about Washington’s ability to uplift and transform the country to conform with American objectives. These assumptions reflected the persistent influence of colonial-era ideas about identity and difference in Southeast Asia.

This pair of themes – which were the two sides of the same ideological coin – shaped the Eisenhower administration’s approach to Vietnam as it went through three phases: first collaboration, then unilateralism, and finally self-congratulation and complacency. Working with the French and other allies marked the initial phase. With France’s final withdrawal of its forces in 1956, Washington embarked upon the second phase, structured around the United States’ singular relationship with Ngô Đình Diệm’s Republic of Vietnam. In the final phase, during Eisenhower’s second term, the White House considered Vietnam a problem largely under control and shifted its attention elsewhere.

Throughout Eisenhower’s presidency, Washington’s perception of Vietnam as a piece on the containment gameboard obscured Vietnamese desires to define their nation’s postcolonial identity. US leaders’ insistence on viewing American security through the lens of containment exaggerated the strategic importance of Vietnam, and effectively precluded any consideration of how best to align US interests with Vietnamese political aspirations. When Eisenhower passed leadership to John F. Kennedy in 1961, he had committed the United States to the defense of a state and a president in South Vietnam whose leadership and legitimacy seemed increasingly in doubt.

Containment: The Blinders of Grand Strategy

If there had not been a Cold War, there almost certainly would not have been an American war in Vietnam. One of the most enduring explanations for the US decision to intervene in Vietnam’s internal conflict and to persist for so long and at such great cost is the concept of flawed containment. Put simply, this argument is that the Truman administration’s grand strategy of containment in response to a perceived Soviet political and military threat to Europe was wrongly adapted to Asia following the Chinese communists’ civil war victory in 1949 and the Korean communists’ invasion of South Korea in 1950.Footnote 2

The errors of applying the containment paradigm to Asia are evident in hindsight. There was no Soviet Army poised on the borders of Southeast Asia, and the historical trajectories of the various Asian nations, many subjected to Western imperialism, were significantly different from those of European nations. Moreover, doctrinaire policy formulas are invariably expressions of sweeping generalizations. American leaders have loved doctrines: the Monroe Doctrine, the Open Door in China, Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, and Franklin Roosevelt’s Atlantic Charter. Truman continued this tradition with his Truman Doctrine, declaring in 1947 with thinly veiled reference to the Soviet Union that “it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities and outside pressures.” He added that “we must assist free peoples to work out their own destinies in their own way” – a prescription that was appealing in abstract form but almost never followed by US leaders in practice.Footnote 3

Strategic doctrines can be quite useful to national leaders making decisions under extreme pressures in a chaotic world environment. Such cognitive shorthand is easy to communicate to domestic and international audiences, especially in comparison to subtle and intricate calculations about local agendas and interests. But the formulation of grand strategy and doctrines can also create problems. Indeed, “the ritual of crafting strategy encourages participants to spin a narrative that magnifies the scope of the national interest and exaggerates global threats … Strategizing turns possible threats into all-too-real ones.”Footnote 4

Eisenhower’s famous “falling dominoes” press conference held on April 7, 1954, illustrates how strategic doctrines are formulated and the unintended consequences that can ensue. The president’s immediate objective during this regularly scheduled press event was actually not the presentation of a doctrine, but the transmission of a message: He wanted to signal Vietnam’s strategic importance to Washington at a moment when the military forces of Hồ Chí Minh’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN) were laying siege to the French garrison at Điên Biện Phủ. But in response to a question about “the strategic importance of Indochina to the free world,” Eisenhower invoked what he called the “falling domino principle.” “You have a row of dominoes set up, you knock over the first one, and … the last one … will go over very quickly,” he declared. “So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influence.” With hindsight, it is clear that Eisenhower’s statement was aimed at enlisting France, Britain, and a few Asian and Pacific nations to commit to a US-led plan for “united action” in Indochina. He did not actually believe that the line of containment would hinge on the defense of Điện Biên Phủ. However, to many of those who heard or read the president’s comments, the binary nature of his logic seemed clear and indisputable: Either the United States would prevent the fall of the region to communism, or disaster would ensue. The domino analogy would go on to serve as the touchstone of US policy in Vietnam for the next four presidential administrations.Footnote 5

The focus on falling dominoes obscured the fact that there was actually much more in the president’s answer. Eisenhower first noted Southeast Asia’s “production of materials that the world needs.” After the domino sentences, he returned to raw materials – specifically tin, tungsten, and rubber. The region’s markets were also important to Japan, he explained, because Japan must have this trading area to prevent its turning “toward the communist areas in order to live.”Footnote 6 He declared that “the loss of Indochina, of Burma, of Thailand, of the Peninsula, and Indonesia … [would] not only multiply the disadvantages that you would suffer through loss of … sources of materials, but now you are talking really about millions and millions and millions of people.” His concern for the population was that it would “pass under a dictatorship that is inimical to the free world.”Footnote 7 He called for “a concert of readiness” but cautioned that “no outside country can come in and be really helpful unless it is doing something that the local people want.” “The aspirations of those people must be met,” he reiterated, adding that “I can’t say that the associated states [of Indochina] want independence in the sense that the United States is independent. I do not know what they want.”Footnote 8

In the long run, however, Eisenhower’s interest in what the people of Indochina might want would be eclipsed by the imperatives of containment. In a 1959 speech, the president reaffirmed his famous image: “The loss of South Vietnam would set in motion a crumbling process that could, as it progressed, have grave consequences for us and for freedom.”Footnote 9 As he prepared to leave office in 1961, Eisenhower issued his Farewell Address, which would become famous for its warning against the military–industrial complex. Yet he opened that speech with a stern warning that the United States continued to face “a hostile ideology – global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method.”Footnote 10 For Eisenhower and American strategists, communists anywhere in the world – including in Vietnam – were enemies of the United States. Like it or not, the people and populations who were threatened by those communists had to be protected, lest the dominoes fall.

Legacies of Colonialism and Empire

As Eisenhower had frankly admitted in his 1954 press conference, he and his advisors had scant knowledge of the views and aspirations of the Southeast Asian populations that US policies in the region were intended to support. The president and his advisors did not understand “those people,” and administration leaders often invoked racist and stereotyped images. A State Department planning document from June 1950, for example, described Asians as peasants “steeped in Medieval ignorance, poverty and localism … [and] insensitive to … democratic ideology … or the desirability of preserving Western civilization.”Footnote 11 This notion of Asians as indolent and incompetent pervaded American opinions of Chinese as well as Vietnamese until the Korean War forced US leaders to acknowledge at least the military prowess of Chinese communist soldiers and commanders. But that experience did not translate into appreciation of the Vietnamese abilities. Lưu Đoàn Huynh, an intelligence analyst in Hanoi’s ministry of foreign affairs, later observed that, unlike Washington’s view of China as a force to be respected, Vietnam was always seen as small, weak, and dependent upon others.Footnote 12

The Eisenhower administration’s uncertainty over how to proceed in Vietnam became apparent in the aftermath of the Geneva Conference. At a National Security Council (NSC) meeting in August 1954, US officials struggled to craft new strategic guidance for US policy. Parts of it fell readily into place: the United States would create a regional defensive alliance (the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, or SEATO) and provide economic and military aid through the French to the State of Vietnam (SVN), the Saigon-based anticommunist entity headed by the former emperor, Bảo Đại. When the council reached the paragraph entitled “Action in the Event of Local Subversion,” however, the discussion abruptly halted. This section sought to articulate policy in the event of communist subversion that was not “external armed attack.” When the president declared that he was “frankly puzzled” on this issue, the council tabled discussion until the next meeting.Footnote 13

A few days later, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles presented several options for the unfinished paragraph. The president impatiently announced that he was not interested in “strictly local” subversion unless it was motivated by Chinese communists. Vice President Richard Nixon offered that the Indochinese communist leader Hồ Chí Minh might actually be a Soviet agent. Eisenhower ended the discussion asserting that “of course if the Soviet Union were the motivating source of subversion, it would mean general war.”Footnote 14 No one seems to have considered the possibility that the Vietnamese, who had defeated the French at Điện Biên Phủ and negotiated a compromise peace at Geneva, might be acting on their own initiative.

Some of Eisenhower’s biographers credit the president with acting cautiously in Indochina in 1954. But this alleged caution is belied by his confidential remarks, which reveal a determination not to countenance Soviet communist success anywhere.Footnote 15 In 1953 and 1954, the president secretly authorized CIA-backed coups against elected governments in Iran and Guatemala, believing those governments were Soviet proxies.Footnote 16 Eisenhower and his advisors were not oblivious to the depth of anticolonial feeling in the Global South and they routinely stated their willingness to accommodate nationalist sensibilities in Indochina. Yet they also frequently displayed a profound inability to reconcile global containment with the indigenous cultural and historical identity of the Vietnamese.

Although US leaders denied having any colonial ambitions in Indochina, the policies they fashioned routinely undermined Vietnamese national sovereignty. Indeed, portraying the communist threat in Vietnam as an absolute danger to the United States required Washington to fashion a Vietnamese solution to such a dire threat. Like the French before them, the Americans had their own views about the future of Vietnam, and they were prepared to employ unilateral and even coercive tactics to achieve those views. The United States had its own civilizing mission, and after the French departure, Washington worked to convince the South Vietnamese to comply with America’s objectives. Although those efforts were often stymied – especially after Ngô Đình Diệm came to power in Saigon – US officials, diplomats, aid experts, and military advisors still persisted in their efforts to fashion South Vietnamese state and society according to American prescriptions.Footnote 17

Collaboration, 1953–5

The first phase of Eisenhower’s stewardship of US interests in Southeast Asia was a collaborative approach that began with Washington’s decision to provide France with material support in its war against Hồ’s DRVN. Eisenhower was uneasy with France’s evident colonial motives, but the Cold War seemed to require a united front with European allies against the Soviet Union. In 1954, France’s commitment to that venture was abruptly thrown into question by the compromise peace agreement reached with the DRVN at Geneva, prompting US officials to promote SEATO as an alternative arrangement.

Although Eisenhower came to office dedicated to global containment, he was also committed to reducing US government spending. As part of this commitment, he introduced the New Look strategy that promised economical ways to protect American security. In public statements, Secretary of State Dulles emphasized the reliance on the United States on nuclear deterrence (or what became known as “massive retaliation”) as a way to counter Soviet threats without stationing US conventional ground forces overseas. However, the New Look also included greater reliance on military alliances, negotiation with adversaries, and covert operations.Footnote 18 Not surprisingly, Eisenhower and Dulles applied elements of the New Look in Indochina. But such cost-cutting concerns, combined with the heavy focus on the US–Soviet confrontation, left little room for attention to Vietnamese nationalism or local Indochinese agendas.

Initially, the United States connected its collaboration with France in Indochina to the building of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Europe. Although many US leaders were skeptical about supporting a French colonial war in Indochina, Dulles told US Senators that “the divided spirit” of the world and containment objectives in Europe required Washington to continue to tolerate colonialism in Indochina a little longer. Dulles also sought French acceptance of a rearmed West Germany as part of an American-backed plan for NATO called the European Defence Community (EDC). To keep the French fighting for containment in Asia and cooperating in Europe, the Eisenhower administration expanded US aid to almost 80 percent of French military expenditures in Indochina by January 1954.Footnote 19

In the early weeks of 1954, as the decisive events at Điện Biên Phủ began to unfold and the French public turned increasingly against the Indochina War, Eisenhower and his aides weighed their options. The president remarked that “while no one was more anxious … to keep our men out of these jungles, we could nevertheless not forget our vital interest in Indochina.”Footnote 20 The decision for the moment was to stay with France, and that option included reluctant agreement to attend the proposed conference at Geneva to seek a negotiated end to the fighting. Meanwhile, the Pentagon examined possible US air and ground operations in support of the French, and the CIA explored clandestine assistance to Bảo Đại’s SVN, including dispatching Lansdale to Saigon.Footnote 21

By March 20, the French position at Điện Biên Phủ had become desperate. General Paul Ely, the French chief of staff, traveled to Washington for consultations. Eisenhower’s advisors considered a tactical US airstrike, an option favored by Vice President Nixon. There is little evidence that the president seriously considered use of nuclear weapons, but massive conventional bombing was a genuine possibility. Eisenhower never ruled out air bombardment, but the president ultimately decided against direct US military intervention, in contrast to later chief executives who deployed US troops and planes to Vietnam. On the weekend of April 3–4, Dulles met first with congressional leaders – Senate Minority Leader Lyndon Johnson among them – who expressed opposition to unilateral American intervention. In response, Eisenhower decided that US military intervention was possible as long as it was multinational, included France, and predicated on eventual independence for Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. In a personal letter to British prime minister Winston Churchill, Eisenhower joined Dulles in pursuing a multilateral demarche. This effort was quietly underway when Eisenhower employed the domino analogy at his April 7 press conference. By the time the Geneva Conference opened on April 26, Dulles had already finished meetings in London and Paris and reported to Washington that there was no time left to arrange the political understanding necessary for joint action. The French garrison at Điện Biên Phủ fell on May 7, ceasefire negotiations plodded along at Geneva, and Eisenhower’s team continued to seek ways to internationalize security arrangements for Southeast Asia.Footnote 22

At Geneva, the Eisenhower administration took a passive role to avoid any responsibility for a settlement that validated communist success in Vietnam. Ironically in view of later US policy, Eisenhower expressed firm opposition in late April to military intervention in Vietnam because “in the eyes of many Asian people [the United States would] merely replace French colonialism with American colonialism.”Footnote 23 The president’s focus remained on the Soviet Union and China and the risk of general war. He disdained “brushfire wars” that “frittered away our resources in local engagements.”Footnote 24 Yet he envisioned the United States taking leadership of an allied defense of Southeast Asia against communist expansion.

American leaders considered the outcome at Geneva a tactical defeat and concluded that two elements of the New Look – negotiation and the threat of bombardment – had proven ineffective. Washington publicly acknowledged but did not formally endorse the Geneva ceasefire terms that included the temporary partition of Vietnam at the 17th parallel. Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) Allen Dulles, using Lansdale as point man in Vietnam, deployed New Look-style covert psychological measures aimed at weakening the DRVN in North Vietnam and strengthening the new administration of Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm in the South. Meanwhile, the DCI’s brother, the secretary of state, took the lead on making the 17th parallel the new containment line in Asia. Discussions within the NSC briefly examined the idea of doing basically nothing in Vietnam to avoid becoming trapped in defense of a rump state in the South, but the president himself ended the talk declaring that “some time we must face up to it: we can’t go on losing areas of the free world forever.”Footnote 25

On September 8, 1954, staying with a collaborative and alliance-focused approach, Secretary Dulles presided over the signing in Manila of the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty. Also known as the Manila Pact, Dulles described it as a “no trespassing” sign warning Moscow and Beijing to keep hands off the region. It was intended as a psychological deterrent and as a mechanism for making joint military action palatable to Congress – something that had been unavailable to Washington during the siege of Điện Biên Phủ. The authors of this agreement purposefully modeled the acronym SEATO on NATO. But the similarity of the two alliances ended there. Unlike the NATO treaty, the Manila Pact did not require an automatic response in the event that one member came under attack. The Geneva ceasefire prohibited South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from joining any military alliances, but an addendum designated them as being within the treaty area and allowed SEATO members (the United States, Britain, France, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand, and Pakistan) to take action on their behalf with their consent. Despite efforts to recruit India, Burma, and Indonesia, those governments declined to join in order to preserve their political neutrality.

Despite its less-than-auspicious launch, the creation of SEATO had lasting implications. Johnson’s 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution cited the SEATO treaty as a US “obligation” in defense of freedom in the region.Footnote 26 The pact was a step toward converting the 17th parallel into another 38th parallel, the line separating North and South Korea – a new segment of the Asian containment line. SEATO also forged new links in the so-called ring of alliances envisioned by the New Look with acronyms such as CENTO and ANZUS, as well as bilateral defense arrangements with Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea.Footnote 27

SEATO was a line of credit upon which South Vietnam might draw some future allied assistance. By itself, however, the pact could not breathe life into the fragile SVN government in Saigon. In June, with the Geneva talks still ongoing, Bảo Đại made Diệm SVN prime minister, anticipating that this anticommunist nationalist known to some prominent Americans would attract US backing.Footnote 28 But Washington’s interest in Diệm threatened the collaborative approach with Paris because French officials knew Diệm to be an anti-French nationalist.

Lansdale arrived in Saigon as Allen Dulles’s “own representative” just in time to witness what he described as Diệm’s inauspicious arrival in the city.Footnote 29 Lansdale invented the Saigon Military Mission (SMM), a team tasked with manipulating information and misinformation, conducting espionage, and covertly advising Diệm. Lansdale’s self-described purpose was “to help the Vietnamese help themselves.”Footnote 30 Many years later Lansdale acknowledged that “I was backed by the CIA” and “I had CIA people.”Footnote 31 The degree of credit the SMM deserves for Diệm’s survival in those early days is difficult to measure, but the efforts of the SMM, other American agents, and some able Vietnamese officials, such as Trần Vӑn Đỗ who had represented the SVN at Geneva, helped resettle Vietnamese Catholics from the North to the South to provide Diệm a small public base of fellow Catholics in the predominately Buddhist country. Lansdale also claimed to have helped Diệm avoid a seizure of power by Nguyễn Vӑn Hinh, the head of the French-created Vietnamese National Army.Footnote 32 Despite these accomplishments, Eisenhower viewed Diệm as a weak figure around whom to fashion a Cold War battlefront. The president decided to send General J. Lawton Collins with broad authority to try to fashion joint US–French assistance to Diệm but also to evaluate honestly Diệm’s survivability and, if necessary, to identify leaders who might be more effective allies.

The Collins Mission was part of a White House “crash program” to invigorate Diệm’s government before, in the president’s words, it “went down the drain.” Washington wanted direct US military aid and training for a South Vietnamese army without going through the French Expeditionary Corps, which was the occupying force designated in the Geneva Accords. Eisenhower thought it was time to “lay down the law to the French.” “We have to cajole the French in regard to the European area, but we certainly didn’t have to in Indochina,” the president instructed the NSC.Footnote 33

Working together, Collins and Ely improved military training and bureaucratic processes in the South, but the fate of the SVN remained uncertain. French officials believed Diệm was an unreliable leader, but Lansdale insisted that Diệm had the potential to be “highly popular.”Footnote 34 Tasked to make an assessment, Collins voiced doubts about Diệm’s leadership almost as soon as he arrived in November 1954, and finally on March 31, 1955, he cabled Washington that Diệm was “operating practically one-man government” and could not last much longer.Footnote 35 He advised that Trần Vӑn Đỗ or Phan Huy Quát, a veteran of several Bảo Đại cabinets, had the experience and political connections to best leverage American support for the South.Footnote 36

An eruption of open warfare in the streets of Saigon and its suburb Chơ lớn – what became known as the Sect Crisis – prompted this urgent message. Diệm had many domestic opponents, including the Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo religious sects outside Saigon and the Bình Xuyên crime syndicate in the city. Whether Diệm’s forces or the Bình Xuyên gangsters fired first, public order had collapsed. French General Ely blamed Diệm for losing control, and Lansdale believed the Bình Xuyên provoked the clash. Washington instructed Collins to try to gain time because Eisenhower and Dulles were not prepared simply to cut off the prime minister. Notably, Diệm had gained the sympathy of significant members of Congress, including senators Mike Mansfield, Hubert Humphrey, and John Kennedy. Likely because of Lansdale’s favorable reports about Diệm through CIA channels, Secretary Dulles encouraged Collins to stick with Diệm. On April 7, however, the general finally determined that “Diệm does not have the capacity to achieve the necessary purpose and action from his people … essential to prevent this country from falling under communist control.” He deemed Diệm to be a patriot but concluded that Diệm was not “the indispensable man.”Footnote 37

With Eisenhower’s permission, Dulles summoned Collins to Washington to try to resolve the differences over Diệm. The president respected both men and left the prime minister’s fate in their hands – until Diệm decided to wrest it back. In Washington, Collins stood his ground and appeared to have prevailed, when suddenly word arrived that Diệm’s forces had engaged the Bình Xuyên gang in renewed fighting on April 27. Lansdale flashed the news to the Dulles brothers and reiterated his argument for continued support of Diệm. Collins later recalled: “I [was] getting instructions from the president of the United States, and this guy Lansdale, who had no authority so far as I was concerned, [was] getting instructions from the CIA. It was a mistake.”Footnote 38 As Collins hurried back to his post in Saigon, Secretary Dulles with the concurrence of the State Department’s Asian specialists decided the violent outbreak was an inopportune time to tamper with the Saigon regime’s leadership. Dulles made the fateful decision to stick with Diệm and extend him America’s “wholehearted backing.”Footnote 39

The Eisenhower administration tried to convince France to accept the course it had chosen with Diệm. After several tense sessions in early May 1955, Foreign Minister Edgar Faure yielded to Dulles’ insistence. French forces agreed to depart Vietnam and leave the fate of the southern portion of the country to Diệm and his American backers. The FEC was formally dissolved in April 1956, and Paris with Washington’s blessing put its military efforts into the worsening anticolonial war in Algeria, seeking to avoid “another Indochina.”Footnote 40 SEATO provided a semblance of collaborative sanction for US efforts to sustain South Vietnam, but the weakness of the pact and the departure of the French meant that the security and development of the South would be a unilateral US program. The Eisenhower administration had entered a new and perilous policy phase.

Unilateralism, 1956–7

At least for the moment, Washington had cast its lot in Vietnam with Diệm. Although Diệm strove to refute communist allegations that his government was a mere American puppet, he ruefully admitted that many Vietnamese had adopted the disparaging term Mỹ–Diệm (America–Diệm) to refer to the Saigon regime. As Diệm moved to consolidate power, Eisenhower and Dulles left it to others to shape the large flows of assistance now programmed for South Vietnam. A heart attack in 1955 slowed Eisenhower for a while, Dulles received a diagnosis of abdominal cancer the next year, and crises emerged elsewhere in the world. American diplomats, military officers, and various development experts set to work on the effort to build an effective state in South Vietnam around Diệm and his family.Footnote 41

This experiment in state-building faced enormous obstacles. The State of Vietnam had a small army of 150,000 with an inexperienced officer corps. Its civil bureaucracy consisted of fonctionnaires trained by the French to take orders, not make decisions. The South had less heavy industry than North Vietnam, and its largely rural population of farmers and fishermen were impoverished from decades of exploitation by Vietnamese and French landlords and colonial taxes. Even before tackling these deficiencies, however, the Saigon government needed to create its own popular legitimacy. Diệm was not a prince of royal lineage, as was Norodom Sihanouk, the head of state of neighboring Cambodia, nor was he a patriotic hero of the war against France, as was Hồ Chí Minh. Any claim to popular authority would have to come from some form of democratic endorsement, presumably an election.Footnote 42

The final declaration of the Geneva Conference had called nationwide elections in 1956 to determine Vietnam’s political future. But most participants recognized that the chances of actually conducting elections were “definitely poor.”Footnote 43 The Geneva documents outlined no voting procedures, nor did they specify which offices or legislative bodies were to be filled by the balloting. One Canadian officer on the staff of the International Supervisory Commission (ISC) later recalled that Hanoi had the atmosphere of a “police state.”Footnote 44 That same officer described the ISC – created by the Geneva conferees to supervise the ceasefire and possibly an election – as “very inactive,”Footnote 45 and scholars have described it as “procedurally defective,”Footnote 46 especially on political matters. The French forces that could have helped implement an election in the South had departed by the spring of 1956. Moreover, neither Bảo Đại’s representatives nor those of the United States or even those of the DRVN had formally endorsed the final declaration at Geneva, including the national elections provision.Footnote 47

The State Department officer in charge of Philippine and Southeast Asian affairs, Kenneth Young, was keenly aware that the legitimacy of Bảo Đại’s State of Vietnam was fragile. Diệm owed his appointment to an ex-emperor tainted by his self-serving associations over the years with the Japanese, the French, and the Bình Xuyên. In the wake of the Sect Crisis, Young feared that elections in the South would invite anarchy.

While Washington officials exhibited little trust in democracy in Vietnam, Diệm acted unilaterally. In October 1955, he staged a referendum that deposed Bảo Đại. He then declared himself president of the newly proclaimed Republic of Vietnam (RVN). A few months later, he and his brothers ran an election that produced a constituent assembly, heavily stacked in their favor, to draft a constitution. These were not exercises in pluralistic democracy – evidence of ballot manipulation was widespread – but they provided a means for the regime to advance its own claims to sovereignty and legitimacy.Footnote 48