On February 12, 1966, a crowd of approximately 15,000 people sat in a rain-drenched Atlanta Stadium to hear speeches by Secretary of State Dean Rusk, General Lucius Clay, and South Vietnamese ambassador to the United Nations, Nguyen Duy Lien. The master of ceremonies was an Emory University student named Remar “Bubba” Sutton, who in December 1965 decided to organize a pro-Vietnam demonstration over dinner with fellow student Don Brunson. Sutton had recently heard Ralph McGill, liberal publisher of the Atlanta Constitution, call on students to “answer” the much-publicized antiwar student demonstrations. The event he organized, Affirmation: Vietnam, was designed to counter the image that the majority of students, or indeed Americans, questioned US policy in Southeast Asia.Footnote 1 The student group intended to send a message to international audiences regarding the commitment of the majority of Americans to supporting President Lyndon Johnson’s military strategies and diplomatic goals. Within weeks of creating the group, Sutton and Brunson had acquired the use of twenty dormitory rooms from Emory University, drafted a constitution, and received tax-exempt status from the Internal Revenue Service. They established links with student body presidents at colleges throughout Georgia and secured financial support from businesses to host a major pro-Vietnam event. The Emory Wheel editorialized that the antiwar “march on Washington and subsequent picketing of the White House during the holidays by pacifist student groups protesting administration policy in Viet Nam is but another slap in the face of common sense and reason.” “Each citizen,” the editors insisted, “has a duty to support his country in wartime, however much he might protest a certain action in time of peace.” It was time to “spread the truth about American sentiment.”Footnote 2

Affirmation: Vietnam attracted students from across Georgia and won the support of several celebrities, including veteran United Service Organizations (USO) entertainer Bob Hope, who emceed a documentary broadcast the week of the event titled “A Generation Awakes.” Singer Anita Bryant, who had previously taken part in Hope’s USO tours, altered her schedule to perform at the rally after Sutton’s late-night surprise visit to her Florida home. It was styled as a mass display of patriotic fervor and relied heavily on institutional support, whether from the universities, business leaders, veterans’ organizations, or state and national politicians, who rallied from across the political spectrum to attach their names to the event. While the rally itself received substantial press coverage both domestically and internationally and was thereby broadly successful, the activism of its organizers was short-lived. The students’ commitment to the speakers’ bureau that was created at the time of the rally may well have been heartfelt, but as Sutton readily acknowledged most students were now focused on returning to their studies.Footnote 3 Within two years, furthermore, antiwar activism was far more prevalent on the Emory campus, and university administrators were keen to appear neutral.

The ad hoc nature of Affirmation: Vietnam was representative of prowar demonstrations that took place throughout US engagement in Vietnam. The more successful events invariably tried to reflect widely held views about the United States’ moral purpose abroad, focused on endorsing the president’s existing policy, and utilized standard tropes relating to American patriotism. Student-led campaigns were the most successful in terms of achieving coordinated and sustained activism. Unlike their antiwar counterparts, however, prowar student campaigners relied on relationships with more established groups. As with Affirmation: Vietnam, these prowar campaigns were often reactionary in nature, designed to counter the image of widespread support for the antiwar movement, rather than intended to create a groundswell of popular activism in favor of any particular military or diplomatic strategy.Footnote 4

Many Americans proclaimed strongly held views about the importance of securing victory in Vietnam, and this chapter will consider the relevance and influence of their political and social activism. Yet, it is important to note the significance of indifference among those who often proclaimed prowar positions, which reflected adherence to the Cold War status quo rather than considered ideological engagement with the war. In sociologist David Flores’s study of contrasting views among Vietnam veterans, he noted that those who remained supportive of the war after engagement described “an absence of strong preexisting ideals before, during, and after their participation in warfare.” In contrast, veterans who became active opponents of the war described themselves as prior war supporters whose idealistic views of warfare had been undermined by the moral dilemma arising from the guerrilla conflict in Southeast Asia.Footnote 5 Flores was primarily concerned with how veterans remembered their experiences and the impact of memory on political views, but his study highlights one key aspect of prowar sentiment throughout the Vietnam War. Many individuals, regardless of socioeconomic background, ethnicity, age, or gender, supported the war because to do so required little engagement with the nature of the war itself or the consequences of military engagement. Supporting the war simply meant supporting the president’s policy, whether it was Johnson’s mass introduction of ground troops and aerial bombardment of North Vietnam, or Richard Nixon’s commitment to escalated bombing and Vietnamization, the incremental withdrawal of American troops, who were replaced with South Vietnamese personnel from mid-1970.

That most Americans became disillusioned with the war due to casualties, the perceived inequities of the draft system, and the apparent endlessness of the conflict is clear.Footnote 6 But it is also evident that Americans continued to respond positively to messages that celebrated global anticommunism and discredited the radical antiwar movement. As Steven Casey notes, the Johnson administration recognized that the antiwar movement provided an opportunity as much as a threat to his selling of the war during 1967. Polling in October of that year revealed that even among students 49 percent supported a hawkish view with 35 percent opposing the war, while among the public more generally only 5 percent stated that the war affected them personally, thus highlighting the “shallowness of the public’s frustration with the war.”Footnote 7 Nixon understood more explicitly the utility of domesticating the war through social and political division in order to buy time for his administration to continue the conflict and force a settlement. While his administration was unable to reverse the course of popular frustration with the seemingly endless war, it succeeded in redefining the meaning of victory in Vietnam and tied his promise of “peace with honor” to popular understandings of the United States’ moral purpose in the international arena.

This chapter will examine two distinct aspects of prowar sentiment: grassroots campaigns to promote popular support for the US mission, which successfully focused on support for American troops and prisoners of war during the later years of the conflict; and conservatives’ ideological commitment to securing military victory after 1964. Conservatives were not alone in pursuing outright victory in Vietnam, and there was considerable division within the movement about both the importance of this particular conflict and the utility of supporting Nixon’s policies relating to negotiation in particular. Yet, conservative political activists were far more consistent than any other group in maintaining support for the goal of defeating communism in Southeast Asia. As the war progressed both policymakers’ and conservatives’ definitions of victory changed, and conservatives increasingly adopted the patriotic perspectives put forward by less ideological prowar activists.Footnote 8 The war altered the character of the conservative movement, furthermore, prompting the development of alliances with social activists less committed to conservatives’ foreign policy goals. As Andrew Johns discusses, divisions over Vietnam among Republicans drove the party in new directions, allowing conservatives to reach ascendency in the Republican Party.Footnote 9 Prowar sentiment was therefore passive in terms of reflecting support for the Cold War status quo. It was active in terms of driving support for conservatives’ emphasis on delegitimizing antiwar activism and championing the need for a return to the superpower Cold War. Public opinion relating to Vietnam was fundamentally in flux throughout the period of US engagement in Southeast Asia and was broadly shaped by domestic events and the effects of the war at home more than by the course of the war itself. Prowar sentiment among Americans was therefore malleable, which made it difficult for the administrations to rely on popular backing. But it was a powerful agent in shaping American politics and contributed to the divisiveness of American society during the 1960s and beyond.

Grassroots Activism and American National Identity in Vietnam

There was little popular demand for US intervention in Southeast Asia during the 1950s and 1960s, yet public opinion rallied in support of Operation Rolling Thunder, the sustained bombing of North Vietnam that began in March 1965, and the introduction of large-scale numbers of American ground troops was widely accepted as necessary. In late March, a clear plurality described themselves as agreeing with the “hawks” over the “doves,” with a quarter of those polled offering no opinion either way. The Affirmation: Vietnam rally was by no means an aberration, and early demonstrations of support for the war reflected its theme of supporting the president and undermining antiwar sentiment. While conservative organizations such as the American Conservative Union (ACU) made considerable efforts to promote the international significance of the conflict and offered specific military strategies for achieving more immediate success, there was little popular appetite for campaigns or rallies that focused on national security. Concerns about appearing opposed to peace further inhibited the development of campaigns that focused on policy in Vietnam, while many Americans remained reluctant to adopt the tactics of the increasingly vocal antiwar movement. Instead, prowar campaigners focused on supporting American men and women serving in Vietnam. But as David Levy notes, individual acts of support for the troops undertaken by “Young Republicans and Young Democrats; by Lions, Moose, Elks and Masons; by the American Legion, the Jewish War Veterans, the VFW [Veterans of Foreign Wars], DAR [Daughters of the American Revolution]; by church groups, women’s clubs, PTAs, the Junior Chamber of Commerce, and Boy Scouts; by garden clubs, labor unions, and 4-H groups; by local newspapers and television stations” cannot be entirely separated from support for the war itself.Footnote 10 Demonstrations such as blood drives, gift programs, and particularly prowar rallies became more prevalent as antiwar sentiment became increasingly vocal. Open expressions of support for the American effort in Vietnam were not, however, undertaken merely because of social and moral rejection of the aims and methods of the radical left. Rather, they reflected faith in the rationale put forward by Johnson for US involvement in Vietnam: a belief that Americans were defending the independence of a weaker people; that they were extending democracy and protecting the freedom of the United States; and that the war was a vital aspect of undermining the Soviet threat. Many Americans may have had difficulty fully articulating the reasons why the war in Vietnam was directly related to American security, with the result that emphasizing support for the troops or for the government became the most relevant means of confirming United States involvement in Southeast Asia.

The most dramatic exhibition of support for American servicemen in Vietnam happened in May 1967, with the We Support Our Boys in Vietnam rally. New York Fire Department chief Raymond Gimmler developed the large-scale patriotic parade because of his disgust at the “peaceniks” and “anti-Americans” protesting the war effort. With the help of the American Legion, Gimmler established an organizing committee for a parade and insisted that his purpose was not to comment on administration policy or to oppose dissent. Rather, the committee resisted “attacks on our nation and the impression given to the world of a people who oppose their country. Above all we are striving to assure our fighting men in Vietnam that they have the full respect, love, prayers and backing of the American People.”Footnote 11 The goal of national unity led the committee to avoid any ideologically narrow or partisan connotations. Yet, the parade was repeatedly portrayed as an antidote to the antiwar demonstration in New York in April 1967 where an American flag was infamously set alight. Gimmler’s aim was therefore to associate the antiwar movement with anti-Americanism, implicitly relating patriotism with support for the government’s objectives in Vietnam. Gimmler and his fellow activists contributed a great deal to the organization and promotion of the event, yet they relied heavily on the practical support offered by the American Legion and echoed its position of support for the war. The VFW also distributed material about the “mammoth Patriotic Parade,” while the organization’s New York department commander Herbert Brian likened the parade to the VFW’s Loyalty Day when “[we] first chased the Communists off the streets of New York.”Footnote 12 The issue of fidelity to the United States served as a powerful rhetorical tool for those committed to the causes for which the country was engaged in Vietnam, even when the “causes” were reduced to matters such as basic anticommunism and protection of American values.

On May 13, approximately 70,000 people marched down Fifth Avenue in a “forest of American flags” during a parade that lasted almost nine hours.Footnote 13 Conservative groups attempted to coopt the allegedly apolitical parade, with the New York Conservative Party’s poster urging citizens to “counteract the vicious anti-American spectacle” of the April antiwar demonstration.Footnote 14 The national board of the conservative Young Americans for Freedom (YAF) associated its prowar position with the event, requesting that its chapter chairmen send “Victory in Viet Nam” buses to the parade. YAF asked attendees “to write their Congressman, US Senators, and President Johnson [asking them] to take all necessary steps [to] win the war in Viet Nam, to support those military advisers who recommend the bombing of airfields in North Viet Nam, [and] to enable American fighting men in Viet Nam to carry out the necessary missions to defeat the Communist aggressors.”Footnote 15 YAF’s objective was to incorporate its demands for change in administration policy, and particularly its effort to associate support for the troops with endorsement of removing the military restrictions on Americans fighting in Vietnam, into the main thrust of the parade.

Conservative hawks succeeded in that many who participated in the parade carried signs urging escalation, and many of the signs carried by participants urged the administration to “Bomb Hanoi.”Footnote 16 The New York Times reported that the “usual atmosphere” of the parade was “belligerent. It showed clearly in such signs as: ‘Down with the Reds,’ ‘My country right or wrong,’ ‘Hey, hey, what do you say; let’s support the USA,’ ‘Give the boys moral ammo,’ … ‘God bless us patriots, may we never go out of style,’ ‘Escalate, don’t capitulate.’”Footnote 17 While the parade was described as mainly orderly, “a dozen times paraders or their sympathizers attacked individuals displaying signs urging the end of the war or expressing such sentiments. A man who was said to be a bystander was smeared with tar and feathers.” The mood created by the march, particularly after the violent ejection of a group of antiwar protestors who claimed that they were expressing support for the troops by demanding their immediate return home, was ultimately one of faith in the American cause in Vietnam.Footnote 18

Parades of this nature served prowar politicians’ longstanding efforts to equate patriotic duty with support for a victory strategy in Vietnam. Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona asserted in 1966 that he was “ashamed to … see [Democrats] telling the American people that our power has made America arrogant and self-righteous and expansionist and immoral.” “No American,” he asserted, “has the right to or the justification to level such charges against his country. And that goes double for doing it in a time of war and in a fashion that lends comfort to our enemies.”Footnote 19 Goldwater asserted that the war was just and necessary, but he also conveyed the message that patriotism demanded that the sacrifice of American life and resources be met with full national support. In criticizing Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara’s decision to leave office in 1967, Goldwater asserted that “no honorable man can walk away from a war to which he has sent hundreds of thousands of men.”Footnote 20

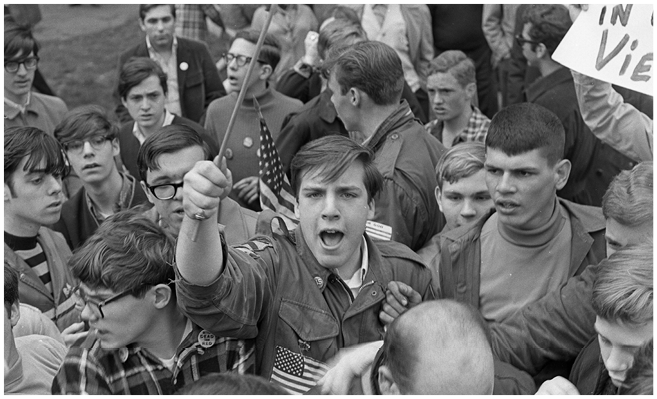

Figure 20.1 Pro–Vietnam War demonstrators at a rally in Central Park in New York City (April 27, 1968).

Goldwater was not alone in this view, particularly in his association of antiwar protest with un-Americanism. While recognizing that many Americans were frustrated with the war, conservatives also understood that broad antipathy toward the antiwar movement could prevent the growth of mainstream opposition to the war. Conservatives certainly promoted this process and actively welcomed the cultural and political polarization that the war appeared to be causing by 1967. Reagan explicitly articulated the negative impact of antiwar protest, lamenting in 1969 that because of domestic protest “some young Americans living today will die tomorrow.” Many of those marching in the name of peace, he declared, “carry the flag of a nation which has killed almost 40,000 of our young men.” Patriotism required support of those “entrusted with the immense responsibility for the leadership of our nation” and “rejection of those in our streets who arrogantly kibitz in a game where they haven’t even seen the cards with which the game is played.”Footnote 21

Late 1969 marked the high point of popular activism in opposition to the antiwar movement. The week of Veterans Day in November 1969 saw many Americans respond to Reagan’s call to arms. “National Unity Week” was developed by Edmund Dombrowski, a California orthopedic surgeon who wanted to challenge the divisiveness in American society he attributed to antiwar protest. The Committee for a Week of National Unity comprised local businesspeople and anticommunist activists and led to a petition drive to enhance popular involvement in local patriotic events. Angered by campus and peace activists, Dombrowski was also influenced by high school students opposed to the antiwar Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam on October 15, 1969. They believed that the president was doing all he could to end the war, but did not want to have to parade in the streets to show their support. Within two weeks of the committee’s founding in mid-October, Bob Hope enthusiastically agreed to become its honorary chairman, and the committee distributed promotional leaflets and more than 200,000 “National Unity” bumper stickers on a daily basis for several weeks. Hope sent telegrams on behalf of the committee to governors and city mayors across the country, urging them to promote National Unity Week. The committee recommended that citizens fly the American flag, wear red, white, and blue armbands, turn on car headlights during the day, leave houselights on over the weekend, pray for prisoners of war, and sign petitions.Footnote 22 The committee’s primary theme was further encouraged by Nixon’s emphasis on the Silent Majority during his early November speech, and therefore used Vietnam as a means of locating individuals on a particular side of debates relating not only to the prosecution of the Cold War, but also to social, cultural, and moral norms.

During the same period, Charles Wiley of the National Committee for Responsible Patriotism (NCRP) developed a similar patriotic campaign. Wiley’s New York–based committee was founded in the wake of the original We Support Our Boys in Vietnam parade, and its staff of volunteers was rallied for specific campaigns. Wiley was a freelance journalist who was long established in anticommunist activism. He asserted that “Honor America Week” was not simply an “antimoratorium venture” but was rather a means of celebrating American unity. Undermining the antiwar movement was clearly a core goal, however. In reference to what he deemed acceptable criticism, Wiley declared: “Responsible criticism would be a disagreement with policy or short-term aims which would not at the same time suggest bad motives on the part of the United States, that would not question the greatness of our country’s heritage, the motivation of our servicemen or the basic honorable intentions of our leaders.”Footnote 23 Wiley petitioned the White House for support, and publicly claimed to have received endorsements from Nixon and the cooperation of the major labor unions and veterans’, fraternal, police, and firefighters’ organizations.Footnote 24 Adopting familiar patriotic tropes, the NCRP’s posters showed images of the Liberty Bell and an astronaut walking on the moon. Honor America Week urged patriotic Americans to use the flag as a symbol of loyalty to the president’s Vietnam policies. While referring simply to the need to “pray for our gallant men in Viet-Nam and an honorable peace as quickly as possible” in its posters, the NCRP made clear its association of “honorable peace” with a measure of victory in Vietnam. Future wars, which would bring “the enemy closer and closer to our shores,” would be the inevitable result of leaving Vietnam prematurely. The US commitment to its Vietnamese ally was tied to its moral integrity as well as its national security. Americans could not abandon their commitment to their allies or their dead. “When you think about conscience,” Wiley stated to CBS, “how do you explain to the loved ones of the nearly 40,000 Americans who thought they were dying to defend their honor – that their cause was immoral?”Footnote 25

The National Unity and Honor America campaigns did not formally unite but cooperated to promote their programs among local veterans and civic groups. The New York Times reported that the two organizations “have offices three doors apart in downtown Washington” and were both involved in “suggesting ways to organizations around the country to generate and demonstrate support of ‘the President’s search for peace.’”Footnote 26 Both campaigns asked little of their projected audiences – flying the US flag at full-staff, driving with headlights on, and attending veterans’ parades remained the staple means of projecting confidence in the president and the war. Tens of thousands of bumper stickers and buttons were distributed, but it was often unclear what organization was promoting these activities. The New York Times reported simply that a “coalition of veterans groups, educators and conservatives are sponsoring an ‘Honor America Week,’” while in New York the VFW, American Legion, Uniformed Firefighters Association, and Patrolmen’s Benevolent Society endorsed similar measures of demonstrative support for the president.Footnote 27 Each organization relied on the traditional Veterans Day parade as a focal point for community activism. As the New York Times commented, from the Los Angeles Coliseum where World War II hero General Omar N. Bradley urged that America “keep the faith,” to the colonial streets of Manchester, NH, where housewives in a Silent Majority Division marched beside veterans, the war dead of the past were linked to the war effort of the present.Footnote 28 Whether because of the publicity campaigns of the committees, because of Nixon’s rallying call to the “great Silent Majority,” or because of simple frustration with antiwar activism, the Veterans Day parades of 1969 received a turnout of unprecedented proportions throughout much of the United States.Footnote 29

Activism in support of Nixon’s pursuit of peace with honor continued during early 1970, in no small part in response to antiwar attacks on the president’s decision to invade Cambodia in April. The most well-known demonstrations took place in lower Manhattan and became popularly known as the Hard Hat Riots. As the work of Frank Koscielski, Christian Appy, and Penny Lewis reveals, responses to the war among working-class communities were far more complex than suggested by the common stereotype of workers who supported the war because they had “less education [and] less interest in politics” and espoused a “more frequent resort to force.”Footnote 30 Koscielski argues that the working people he analyzed “were no more supportive of the war than the general population” as a whole.Footnote 31 Appy also cites public opinion surveys that indicated little difference between the opinions of workers and those of middle- and upper-class Americans.Footnote 32 Penny Lewis’s work reveals the strength of working-class involvement in the antiwar movement and discusses the significance of contemporary media and scholars’ failure to acknowledge the relevance of class consciousness among working-class antiwar campaigners.Footnote 33 There is a clear need to distinguish between the stance adopted by unions and the opinions of union members. As Lewis notes, “big labor’s embrace of the Vietnam cause confirmed the image of the working-class patriot who shouts ‘love-it-or-leave-it’ at young, entitled hippies.”Footnote 34 The large-scale support for the war among prominent American figures of the Roman Catholic Church also cemented the image of ethnic working-class support for the anticommunist crusade in general and the Vietnam War in particular. Despite the inaccuracy of this stereotype as applying to the “working class” as a whole, and despite the failure of the public, media, and government to acknowledge the nuances of working-class attitudes toward the war, the image of patriotic “middle Americans” in favor of the war provided a compelling contrast to the supposed elitism of antiwar campaigners.

Writing in early May 1970, presidential aide Tom Charles Huston, a former chair of Young Americans for Freedom, asserted the need for White House officials to recognize the class resentment and anger of blue-collar workers. “Fed up with more, of course, than rampaging students,” Huston wrote, “construction laborers, clerks, store-keepers, taxi drivers or factory workers” were frightened of the rapid pace of change within American society and were “confused and frustrated and getting angry.”Footnote 35 Huston was prompted to compose his memorandum by the events of “Bloody Friday” when construction workers in lower Manhattan attacked students protesting the recent killing of four students by Ohio National Guardsmen during an antiwar protest at Kent State University. Construction workers interrupted the antiwar protest and marched to nearby City Hall, where they forcibly hoisted the US flag to full-staff in repudiation of liberal Republican mayor John Lindsey’s decision to lower it to honor the students who had died. The violent attacks on protestors became headline news across the nation.

Nixon was certainly keen to make use of the issue and held a high-profile meeting with representatives of the New York unions at the White House, dismissing the advice of aides who warned that directly associating with those held responsible for the riots might alienate Americans angered by yet more violence. The White House encouraged Peter Brennan of the New York Building and Constructions Trades Union to organize the pro-Nixon demonstration on May 20, 1970. Designed to counter the negative image of rampaging and violent workers, the second march heavily evoked a love-of-country theme, reinforcing the link between patriotism and support for the war. The peaceful parade involved close to 150,000 people and included labor union members and their families, police and fire department officers, and thousands of individuals who wished to express their support for the president.Footnote 36 Recognized at the time as expressions of faith in the Vietnam War, the pro-Nixon or pro-America demonstrations which took place throughout the United States in the aftermath of the Cambodian incursion limited the impact of antiwar demonstrations. While it was not possible to promote support for the war continuing indefinitely, these prowar demonstrations provided much-needed political capital as Nixon prolonged the increasingly unpopular war. Although those labor leaders who met with Nixon in May promised to continue the marches in support of the president, the May 20 rally was the last great parade in the vein of the We Support Our Boys in Vietnam parade. As Nixon intensified Vietnamization, so too did fervent supporters and patriots reduce their activism in favor of the Vietnam War. Few anticipated that the war would last almost another three full years.

In February 1970, 55 percent of those polled by Gallup indicated that they did not support an immediate withdrawal from Vietnam, yet the number who did favor such a policy had risen from 21 to 35 percent since October.Footnote 37 Shortly after the announcement of the Cambodia incursion a majority of Americans, 56 percent of those polled, stated that it had been a mistake to send troops to Vietnam in the first place, while only 36 percent insisted that it had been the right policy.Footnote 38 Americans were increasingly divided over Vietnam, with higher numbers accepting the position that it was “morally wrong” for the United States to continue fighting the war. Such division did not easily reflect a simple hawk-versus-dove dichotomy, however, as by May 1971 only 42 percent were willing to accept a coalition government in Saigon that included communists if this was the only available means of securing a peace deal.Footnote 39 For Americans who did not share the widening antiwar movement’s critique of the war as immoral, unnecessary, or unwinnable, support of Nixon’s policies of withdrawal and Vietnamization provided a positive means of interpreting the war despite growing frustration with its longevity. Nixon’s insistence that the war was winding down, despite intermittent bombing campaigns during 1971 and 1972, altered popular narratives about American goals in Vietnam. Rather than focus on winning the war, prowar activists increasingly emphasized the moral superiority of both the United States and war supporters through campaigns to highlight the plight of American prisoners of war and celebration of American servicemen.

Arguably the most successful prowar organization was originally founded in California in 1966 as the student-led Victory in Vietnam Association (VIVA). Its goals at that time were similar to those of Affirmation: Vietnam and focused explicitly on challenging the idea that students as a whole opposed US policy in Southeast Asia. Initially VIVA was led by students affiliated with the Republican Party who worked to establish chapters on campuses across the United States in order to bring “both sides of the Viet Nam question to the students.”Footnote 40 One of VIVA’s primary goals was to project the Vietnam War in positive terms, which could be secured by emphasizing the barbarity and immorality of the Vietnamese communists. This implied a dichotomy between good American troops serving in Vietnam and an evil and corrupt enemy. One of VIVA’s most widely publicized initiatives was titled “Friendly Viet Cong” and presented photographic evidence of alleged communist atrocities, thereby providing compelling animation to VIVA’s campus demonstrations and tutorials.Footnote 41 According to VIVA, “this presentation has had profound results in that it establishes that terror is necessary for political control by the Viet Cong.”Footnote 42 Its literature further challenged the “allegation made by ‘antiwar’ groups that America [was] engaged in ‘reckless’ and ‘wholesale’ napalming of Vietnamese civilians.”Footnote 43

This line of argument became more pronounced in response to the large-scale antiwar demonstrations of 1969. VIVA emulated National Unity Week activities by calling on individuals to “wear red, white and blue armbands, fly the American Flag and turn on their porch and car lights.”Footnote 44 Judy Davis of VIVA charged protestors with betrayal of their fellow youth serving in Vietnam “to have Hanoi publicly endorse the moratorium and offer congratulations to the participants must certainly be the highest insult ever paid an American serviceman.”Footnote 45 VIVA called for Americans to avoid demonstrations by channeling their energies into positive programs such as its own Operation Mail Call – the sending of letters and packages to American servicemen. While such programs reflected VIVA’s continuing dedication to the armed forces, the group’s rhetoric was couched in the terms of support for the present US military engagement. The demonstrations would surely be interpreted, according to VIVA, “as tantamount to calling for an American surrender in Vietnam without regard for the reason forty thousand Americans have given their lives.”Footnote 46

By 1969, the concept of outright military victory in Vietnam was neither politically viable as a policy goal nor a useful means of winning popular backing, and so the group’s name was changed to Voices in Vital America. Soon after, VIVA developed the prisoner-of-war bracelet campaign, which enormously enhanced its reach beyond like-minded students. Engraved on each bracelet was the name of an American prisoner or individual missing in action and the date on which he went missing. Originally VIVA stated “it is to be worn with the vow that it not be removed until the day that the Red Cross is allowed into Hanoi to assure his family of his status and that he receives the humane treatment due all men.” This was subsequently modified, as Hanoi began to respond to international pressure and to use antiwar forces in the United States to satisfy demands regarding information on POWs. Bracelets were later expected to be worn until the POW was returned or an accounting was made, thus upping the demands and the stakes in the POW/MIA cause. By creating “a level of personal involvement and a visible display of Americans uniting behind a common cause,” VIVA was again able to tie its support for the war to its twin themes of encouraging demonstrative faith in the American system and promoting anticommunism abroad.Footnote 47 As the Nixon administration discovered also, however, the POW issue did not lend itself to easy control. VIVA earned substantial income from bracelet sales and was able to open sixty-eight offices to distribute millions of bumper stickers and pamphlets by 1972. But these materials related almost exclusively to POWs and, while VIVA continued its support of the administration’s policy of phased withdrawal, public demands for a more rapid end to the war were fostered by VIVA’s emphasis on success being associated with the return of American prisoners. The ambiguous association of support for the troops or prisoners served prowar activists’ goals during the early years of the conflict, but by 1972 many Americans were prepared to accept a peace settlement that did little more than result in the return of American prisoners and celebrated American servicemen. Prowar activism helped change the meaning of victory in Vietnam, ensuring that Nixon’s declaration of “peace with honor” in 1973 appeared plausible. And, while Barry Goldwater might have declared the settlement a great victory, it was evident that the Peace Accords were far from what conservative national security hawks had expected to achieve when they supported the war in Vietnam.

Prowar Sentiment and the Development of the Conservative Movement

Vietnam was not the war that conservative political leaders and activists had wanted. There was little appetite for another ground war, given the widespread conclusion among conservatives that the Korean War had ended disastrously. Conservative political activists were conflicted over Vietnam during 1964 and indeed for much of the war. Their perspective on the international ambitions of the Soviet Union and its use of wars of national liberation convinced them of the importance of directly meeting the communist insurgency in South Vietnam. Their inaccurate belief that this campaign was being solely directed by Hanoi led them to push for military attacks against North Vietnam. Yet, this was not the war of conservatives’ choosing, and their concern that it distracted public attention from what they believed were more serious threats, such as Cuba, impacted the extent of their early commitment to the emerging conflict.

Demands for escalation increased dramatically following the military coup against Ngô Đình Diệm, the president of South Vietnam. Claiming that the administration of John F. Kennedy could not have been an “innocent bystander” in the coup, the Chicago Tribune asserted that US military officials had not been opposed to the Diệm regime and charged that “liberal correspondents” in Saigon had continued the propagandist drive which had also undermined Chiang Kai-shek and Fulgencio Batista.Footnote 48 A subsequent article in the conservative weekly Human Events detailed the “inglorious role” of the United States in the overthrow of Diệm, and concluded: “The only sure thing in Vietnam today is that the United States has set an extremely controversial precedent by encouraging, for the first time in our history, the overthrow in time of war of a duly elected government fighting loyally against the common Communist enemy.”Footnote 49 Conservatives began to talk of Vietnam as a vital test of American will and credibility. It was, Goldwater claimed, “as close as Kansas or New York or Seattle” in “the mileage of peace and freedom.”Footnote 50

Conservatives were united in their rejection of the restrained military strategies originally implemented by the Johnson administration. Some, including Southern Democrats such as Senator Richard Russell of Georgia, favored a strong push for victory or an immediate plan to terminate US involvement. Governor George Wallace of Alabama insisted that he would simply hand control of the war over to the generals and either “win or get out” during his 1968 presidential campaign, and such an argument had particular appeal as a rhetorical tool for far-right figures such as Fred Schwarz. Conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly also “originally opposed sending American troops to Vietnam” and later “maintained that the Vietnam War was a Soviet-engineered distraction designed to weaken America’s defense capability.”Footnote 51 On the eve of the Republican National Convention in 1964, Goldwater simply stated that he would hand the management of the war over to the Joint Chiefs of Staff and say, “Fellows, we made the decision to win, now it’s your problem.”Footnote 52 For the most part, however, conservatives did not seriously advocate that the United States should either win immediately or pull out.

During 1964 conservatives overwhelmingly pushed the Johnson administration to escalate its air campaign against North Vietnam. In July, Human Events argued that because of Johnson’s “‘no-win’ policies” it was necessary to increase troop levels in South Vietnam.Footnote 53 Goldwater’s presidential platform left little ambiguity regarding Vietnam and insisted that the United States should “move decisively to assure victory in South Viet Nam.”Footnote 54 He insisted that the United States could not afford to fight a “defensive war”Footnote 55 and focused on the importance of airpower to defoliate the pathways on which supplies traveled into South Vietnam and force Hanoi’s capitulation.Footnote 56

Conservatives’ military options for Vietnam were based on the principle that the war should not be limited to South, or even North, Vietnam, and they denied that extension of the war into either Laos or Cambodia would escalate the conflict internationally. The conservative American Security Council argued that, by cutting off Laos and Cambodia as “a base of supply and sanctuary for the Viet Cong, both the military and the all-important psychological atmosphere in South Viet Nam could be transformed.”Footnote 57 Ignoring the clear signs of French and British wariness about US military intervention, Goldwater claimed that “no responsible world leader suggests that we should withdraw our support from Viet Nam,” and committed the United States to learning the lessons of Korea: “In war there is no substitute for victory.”Footnote 58 In no small part conservatives’ limited emotional commitment to Vietnam was determined by the perception that this was “Johnson’s war.”Footnote 59 In spite of these conflicted perspectives on the war, the opportunity to directly challenge communist expansion trumped a deep hostility to Johnson’s understanding of international relations. Indeed, Johnson’s pursuit of limited war in Southeast Asia provided clear political opportunities for both Republicans and the wider conservative movement. Desperate to escape the connotations of extremism or radicalism associated with rightwing politics, conservatives associated with the National Review and the ACU viewed Vietnam as an opportunity to push for a stronger anticommunist foreign policy without attracting unwarranted claims that they were warmongers.

Nixon developed support among conservatives largely because of his challenge to Johnson’s handling of the Vietnam War.Footnote 60 While Reagan was certainly the preferred Republican presidential candidate among many conservatives in 1968, Nixon was readily identified as more than acceptable because of his longstanding calls for military escalation in Vietnam. Nixon privately revealed in early 1968 that he did not think military victory possible because of the public’s frustration with the costs of the war, and publicly let stand the flawed notion that he had a secret plan to end the conflict. As Nixon’s Vietnam policies developed during the first six months of his presidency, conservative reactions were mixed. Frustrations among hardline hawks that the administration had not ended the bombing pause introduced by Johnson in October may have been shared by conservative Republicans such as Goldwater and Strom Thurmond (R-South Carolina). But few conservative political leaders rejected Nixon’s plans to reduce US troop numbers or questioned the president’s commitment to secure the freedom of South Vietnam. Before Nixon’s May peace proposal, Goldwater stated that he believed the administration may have “issued some ultimatums to the North Vietnamese which had not been made public.”Footnote 61 By July he asserted that troop withdrawals would not be allowed to hinder American objectives in Vietnam. Nixon was “not going to tolerate any soft peddling” with the North Vietnamese and would do what was “necessary militarily to bring this war to an end.”Footnote 62 While praising Nixon’s policies, claiming that “for the first time we have an administration that has the courage to look at the situation in Vietnam realistically,” Thurmond reiterated the need to acknowledge that Vietnam was but one element of a global struggle and that disengagement would depend on the international environment.Footnote 63 The ACU continued to focus on ensuring that a coalition government was not imposed on Saigon, but it did not object to the NLF participating in free elections and essentially endorsed the process of Vietnamization.Footnote 64 Within the conservative community, support for Vietnamization was based on the fundamental assumption that it would be coupled with more forceful military measures if the generous overtures of the United States were not met by North Vietnamese reciprocity. As such, support for Vietnamization was opportunistic among conservatives, presenting the possibility that the United States might finally use its military might to strike a knockout blow at Hanoi.

By January 1973 the conservative movement was highly fractured in relation to the Nixon administration and the pursuit of détente. Leaders at the ACU and National Review launched an ill-fated challenge to Nixon’s visit to China that was met with hostility from Republican leaders such as Goldwater. Such division undermined any serious conservative opposition to the slow winding down of the Vietnam War, and conservatives were buoyed by the resumption of bombing of North Vietnam in the wake of the Easter Offensive. There was considerable unease among conservatives, however, during late 1972 when the peace terms resulting from Kissinger’s secret negotiations significantly undercut conservatives’ minimum objectives. The proposal for a ceasefire-in-place was particularly unacceptable and, once negotiations broke down again in October, conservative supporters of the administration such as Goldwater and writer and commentator William F. Buckley, Jr., insisted that the administration could reach a settlement only when Hanoi was forced to concede.

The Linebacker II bombing campaign presented conservatives with a means to positively interpret the way in which the Vietnam War ended. While militarily significant, Linebacker II was principally designed to reassure President Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu and also Nixon’s most ardent prowar constituency, his conservative supporters, that the proposed accords secured “peace with honor.” Goldwater was determined to use the bombing campaign to validate his philosophical objections to limited war. He lambasted those who protested the administration: “I insist there is no such thing as a limited war … When you go into a war, the more effort and power you put into it the quicker you win it – and at less cost and fewer casualties. President Nixon understands this but his predecessors apparently did not.”Footnote 65 Conservatives remained concerned about the specific details of the peace terms and there is evidence that they expected true Vietnamization to allow the United States to return to the air war once the Peace Accords were inevitably violated by Hanoi. Yet, the tenor of the patriotic campaigns of the previous three years severely undercut conservatives’ interest in mounting a strong challenge to the administration at this time. Congressional opposition to Nixon’s policies only served to heighten conservatives’ willingness to accept the limited gains the administration had made.

Popular opposition to the bombing led to conservatives’ acceptance that the wider public simply would not countenance further military measures. Aware of the likelihood that Congress would limit resources for a continued war, Goldwater, Thurmond, and others were intent on supporting the president’s peace terms. This position was reinforced by the increasingly vocal and troublesome demands for immediate settlement emanating from the ranks of the POW/MIA campaign. POW/MIA organizations pressured the president to secure a settlement and the immediate release of prisoners. In many respects the movement Nixon had helped create for his administration’s benefit was now beyond government influence. Having persuaded the public that the POW issue was a priority in the war, it was difficult to call for patience when this noble goal was in sight.Footnote 66 By January 1973 it was clear the administration would not continue the war for much longer. Conservatives were unwilling to be seen as extreme in matters of foreign policy and knew that opposition to the Peace Accords would be politically devastating. Despite all their protests of October and November 1972, in January 1973 conservatives rallied to champion the ending of the Vietnam War, declaring that the United States had achieved a great victory. In this sense, they aided the Nixon administration’s subtle abandonment of South Vietnam.

In the wake of American withdrawal a series of Welcome Home parades was organized by veterans’ groups and activists who had originated the We Support Our Boys in Vietnam parade. They reaffirmed the idea that patriotism was tied to supporting American servicemen and honoring their sacrifices. In several parades, participants wore hard hats intended to evoke popular memories of the most famous anti-antiwar events of the long domestic conflict over Vietnam. By 1973 fewer Americans were prepared to accept that the war had been necessary. And both the Nixon administration and conservative leaders had learned that patriotism was not something that could easily be harnessed for narrow political or strategic goals. Yet, if prowar sentiment had declined with each passing year of the war, it had also served to redefine American politics, undermining the association of many traditional Democratic constituencies with the party and cementing powerful alliances between intellectual and social conservatives. Conservative leaders had learned that their foreign policy objectives relied on appealing to popular understandings of American purpose in the world, while recognizing the limits to the public’s acceptance of war. In the wake of American defeat in Vietnam, prowar sentiment transformed into a socially powerful critique of the antiwar movement’s betrayal of the United States. Despite conservatives’ efforts, it was not possible to “win” the war by claiming that the United States should have tried harder to secure military victory. Nor did the public unanimously rally to Reagan’s definition of the war as a “noble cause.” Yet, prowar sentiment continued to play an important role in sustaining the divisiveness of the war years, ensuring that for many Americans the cultural Vietnam War did not end in 1973.