In 1966, Argentinian revolutionary Che Guevara wrote an address to the newly formed Organization of Solidarity with the Peoples of Asia, Africa, and Latin America (OSPAAL). He was then based in Cuba, where he had served as a commander of the rebel army in the revolution of 1959 before becoming a government official under Fidel Castro. Che would eventually support and lead anti-imperialist, guerrilla movements in the Congo in Africa as well as other parts of Latin America, including Bolivia, where he was ultimately assassinated in November 1967. In April 1967, however, his message to OSPAAL was published in the organization’s magazine, Tricontinental. In what has become a movement classic, Che wondered, “How close we could look into a bright future should two, three or many Vietnams flourish throughout the world with their share of deaths and their immense tragedies, their everyday heroism and their repeated blows against imperialism.”Footnote 1 This call for “two, three, many Vietnams” became a popular slogan during the US wars in Southeast Asia. It conveyed how radical activists around the world understood Vietnam not as an isolated country or exceptional war. Instead, they interpreted the Vietnam War as a, and arguably the, primary example of US imperialism. The slogan also captured how the North Vietnamese and the National Liberation Front (NLF) served as heroic role models whose resistance could be replicated around the world.

Drawing upon the burgeoning scholarship on the global 1960s, this chapter argues that the Vietnam War was a key historic event that internationalized radical social movements. The war did so in three main ways. First, through the conflict, activists in different parts of the world formed a global public sphere. Through transnational circuits of travel and information exchange, critics of the war developed a common “international language of dissent.”Footnote 2 They nurtured a belief in the need for resistance against those with military, financial, and authoritarian political power and shared a repertoire of activist strategies. Individuals, organizations, and movement communities based in different locales and nation-states disagreed with one another in terms of political analysis, ideology, and resistance tactics. Nevertheless, there was a tendency toward creating a “global consciousness.” In the words of the editors of New World Coming: The Sixties and the Shaping of a Global Consciousness, “one of the defining features of the political and cultural movements of the era was the feeling of acting simultaneously with others in a global sphere, the belief that people elsewhere were motivated by a common purpose.”Footnote 3 This global public sphere helped to transcend Cold War and colonial divisions between the First, Second, and Third Worlds, terms and identifications embraced by historical actors of that era. However, these geopolitical formations as well as the uneven power relations within and across each world also shaped how activists understood and participated in internationalized antiwar movements against US imperialism.

Second, the resistance against the Vietnam War fostered internationalism by foregrounding the agency of the marginalized. The war featured a David-versus-Goliath competition between a presumably backward, peasant society against the mightiest military in the world. The Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN) and the NLF did receive support from the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Nevertheless, it was the Vietnamese revolutionaries – male and female, young and old – and their dedication to fighting, organizing, sacrificing, and even “winning” that made them into global role models. Their status as the ultimate underdogs helped to bring attention to others who experienced systematic oppression due to race, class, gender, religion, political ideology, and so on. It became more conceivable to celebrate subaltern groups and individuals as makers of history, capable of what Che called “everyday heroism.”Footnote 4 There were blind spots to this recognition of the subaltern, as the oppressed could easily be tokened as victims and iconized as one-dimensional heroes. Still, the idealization of Vietnamese revolutionaries facilitated a crossborder identification of shared oppression.

Third, the wars in Southeast Asia helped to internationalize antiwar resistance by illuminating the interconnectedness of various systems of inequality. Imperialism and colonization became part of the activist lexicon, utilized to interpret cultural, racial, class, gender, and other forms of exploitation everywhere. Vietnamese representatives and sources of publication played an important role in disseminating the political message about the interlocking nature of power as well as the idea that the “powerless” could perform meaningful forms of resistance. However, Vietnam also became a symbol that non-Vietnamese around the world could imbue with meaning. Vietnam served as a multivalent signifier of oppression and resistance. As such, the idea of “Vietnam” could be used to identify multiple manifestations of imperialism as well as the need to challenge these forms of inequality both abroad and at home.

This chapter will draw upon the increasingly rich scholarship on transnational protest movements, particularly those based outside the United States, during the “long 1960s.” These studies explore the uniqueness of periodization, historical events, and political actors in different locales, but they also point toward how these local, regional, and national movements reached beyond political borders and Cold War divisions. Regardless of the issues debated during the “long 1960s,” Vietnam was frequently invoked as part of these transnational cultures of dissent. There were significant points of political difference as well as misunderstanding within this global network of activists. This relatively brief overview of international antiwar activism will illuminate how the circulation of people and ideas facilitated the creation of a global public sphere, and the recognition of subaltern heroism, as well as the replication of Vietnam as a symbol of imperialism and resistance.

A Global Public Sphere

How did Vietnam, a relatively small country in Southeast Asia that most Americans could not locate on a map, become a familiar site of war and a source of global political inspiration? Martin Klimke, in his study of the transnational connections between student protests in the United States and Germany, argues that it was the antiwar movement in the United States that transformed the leading New Left organization, Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), into an international phenomenon:

Starting in 1965, the growing antiwar movement in the United States influenced the style of protests on an international level … [The] movement was also able to gather a worldwide following of protestors by the late 1960s, all of whom had one thing in common – their opposition to the Vietnam War.Footnote 5

This collective antiwar movement articulated similar critiques of the war as a US-led imperialist venture that utilized inhumane forms of warfare. The activists in different locales also utilized a common set of protest strategies, ranging from teach-ins and nonviolent direct action, to protest theater and even guerrilla-like forms of violent resistance. Both the recognized movement leaders and the rank-and-file activists shared ideas through travel and the circulation of activist literature. Through repetition, the underground activist media fostered a common political language and a sense of simultaneity for their readers. Together, they created a global public sphere, in which people and ideas traveled across borders to create a common protest language as well as a shared sense of community and responsibility.Footnote 6 This global public sphere had the ability to bridge Cold War and colonial divisions. However, people of varying backgrounds, from different nations and regions of the world, and as members of the First, Second, and Third Worlds, also tended to perceive Vietnam and the conflicts there in diverse ways.

Activists in First World nations based in Western Europe, North America, Australia, and arguably Japan recognized the global reach of US political and military interests. By definition, as constituents of the “First World,” countries such as West Germany, France, Canada, and so on were political allies of the United States during the Cold War. Their collective participation in alliances such as NATO (the North Atlantic Treaty Organization), ANZUS (Australia, New Zealand and US Security Treaty), and other security agreements tethered the political interests of First World nations to that of the United States. The relationships with the United States and policies of each nation varied, and some were quite critical of US policy in Southeast Asia.Footnote 7 Overall, these countries tended to receive reconstruction aid from the United States in the aftermath of World War II, serve as host countries for the expansion of US military bases during the Cold War, and be subjected to diplomatic pressures to support US policies globally, including in Southeast Asia. Many of these First World countries also experienced being on the frontlines of the Cold War. The political tensions between “East” and “West,” the militarization of their societies, and the possibility of nuclear annihilation were tangible threats.

In this context, the activists who opposed the US wars in Southeast Asia tended to frame their critiques in terms of both US aggression/imperialism and their own governments’ perceived collusion in these conflicts. Protests throughout the First World targeted symbols of American influence (e.g., America House in West Berlin) and US political leaders (Vice President Hubert Humphrey’s European tour in 1967) for protest. In his characterization of the British New Left, Holger Nehring argues that “some activists … framed … the United States … as a war-prone capitalist–imperialist power. They rejected American consumerism as potentially totalitarian and regarded the American intervention in Vietnam as a novel form of colonialism.”Footnote 8 Bertrand Russell’s Tribunal on Vietnam, held in Sweden and Denmark in 1967, charged the United States with war crimes.Footnote 9 In addition, antiwar activists in the First World also critiqued their own nation’s support of US policies. For example, members of the German SDS (Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund) targeted NATO “as the central offspring of global imperialism in Western Europe.”Footnote 10 Rudi Dutschke, one of the key leaders in Germany’s New Left, called for both an “attack [against] American imperialism politically” and “the will to break with our own ruling apparatus.”Footnote 11 Antiwar activists in the First World condemned both existing policies that supported US militarism and their nations’ past colonial and ongoing militaristic endeavors, such as the UK’s policy of nuclear proliferation, France’s wars in Algeria and Vietnam, Germany’s Nazism, Australia’s settler colonialism, and Japan’s empire in Asia. The struggles in each locale were interpreted as part of a broader global pattern. At the February 1968 Vietnam Congress held in West Berlin, approximately 5,000 activists from across Europe, the United States, and other parts of the world were in attendance.Footnote 12 Participants, encouraged by US activists, understood their collective antiwar activism as forming “an international ‘second front’” in the Vietnam War.Footnote 13 The war was being waged not just in Southeast Asia but in the First World as well.

The motivation and antiwar activism of those in the socialist Second World differed from those in the First World. Again, variations existed across nations and over time, but the Soviet Union and East European socialist nations tended to condemn the Vietnam War as part of their government- and party-endorsed policies. Having official diplomatic ties to the Democratic Republic of Vietnam facilitated the sponsorship of international anti-imperialist meetings and conferences in Eastern Europe and the circulation of political travel through the Soviet Union. The convenings in Eastern Europe attracted representatives from the East and the West, facilitating political dialogue and fostering a global public sphere. For example, members of US antiwar movement met with representatives of the NLF and DRVN in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, in 1967 and in Ljubljana, Yugoslavia, in 1968. Tom Hayden of the US SDS attended the Bratislava meeting, along with thirty-seven other Americans as well as representatives from antiwar movements from other parts of the world. These meetings had a profound impact on antiwar activism globally. Vietnamese representatives discussed the possibility of releasing American POWs to US antiwar activists as acts of solidarity, which in fact occurred through followup discussions and travels to Southeast Asia.Footnote 14 Bernadine Dohrn, who became a leader in the Weather Underground, recalled that the 1968 meeting in Ljubljana “was life-altering”; it “took place the same week as the Democratic National Convention demonstrations in Chicago, the same week that the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia. This convening of New Left forces, who consciously came together after the spring 1968 uprisings in both the US and Europe, including Eastern Europe, was hugely transformative because it helped us locate where we were in history.”Footnote 15 These meetings in the Second World were facilitated through state resources and Communist Party organizations such as the Women’s International Democratic Federation (WIDF) and the World Federation of Democratic Youth (WFDY). The gatherings established contact and facilitated invitations for antiwar activists in the First World to visit Vietnam itself. These subsequent travels often went through the Soviet Union, particularly Moscow, before arriving in the DRVN.

Although the Second World helped facilitate political dialogue and travel across the First, Second, and Third Worlds, the motivation of activists also differed from those from the other geopolitical regions. Nick Rutter points out that activists from the West and those from the East might have shared a common vocabulary and critique of the Vietnam War; however, they had different understandings of politics.Footnote 16 Dutschke, who defected to the West from East Germany, encountered cynicism when he traveled to a conference in Prague in 1968. Even prior to the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia that year, Dutschke had discovered a lack of understanding for his enthusiasm for Marxism; for Czechs who dialogued with Dutschke, “Marxism meant oppression.”Footnote 17 Similarly, Polish activist Adam Michnik argued that he and his Warsaw comrades “fought for freedom,” while students from the First World “fought against capitalism.”Footnote 18 Internationalist gatherings, like the 9th World Youth Festival, held in Sofia, Bulgaria, in 1968, were not necessarily free, open arenas for political exchange. Instead, the speakers, performers, agenda, and attendees were carefully monitored by the socialist state to foster particular types of internationalist discussions.

Nevertheless, the cause of Vietnam held political appeal for those resisting Soviet and socialist political control. The DRVN, a relatively small country, and the NLF, based in South Vietnam, had to skillfully navigate political differences between the USSR and the PRC in order to chart their political and military paths.Footnote 19 East European countries shared this position of having to negotiate Soviet control. As a result, Vietnam received both affective and political support as well as economic and material aid from East European countries and their citizens. In her study of the German Democratic Republic, Christina Schwenkel notes that “solidarity campaigns in East Germany, through voluntary and coerced mechanisms, garnered extensive humanitarian and other aid to Vietnam.”Footnote 20 While some scholars document that this officially mandated internationalism generated resentment among East Germans who felt obligated to donate, others point to the “depth of empathy felt by Eastern German citizens for those struggling against invasion, occupation, and racialized oppression, and the salience of a moralized sense of differentiation from the US-led bloc.”Footnote 21

The political solidarity between the Second and Third Worlds revealed ambivalence regarding the role of race in socialist political ideology. While racial dialogue was officially banned in East Germany in the aftermath of World War II and tended to be minimized within the Second World, there nevertheless existed a tendency to represent Vietnam and other Third World countries and peoples through a practice that Quinn Slobodian describes as “socialist chromatism.”Footnote 22 Socialist propaganda posters tend to feature “racial rainbow” motifs that “profile[d] nonwhite objects of solidarity,” oftentimes in stereotypical and caricatured ways, to proclaim internationalism and to attack imperialism.Footnote 23 These displays of socialist internationalism built upon Soviet representations of “a multiethnic territory under a single administration” and anti-imperialist political rhetoric.Footnote 24 These representations, which foregrounded race, helped to generate empathy and political solidarity. Although Schwenkel points out that East Germany contributed the most aid in comparison with other European socialist countries, the sense of socialist international solidarity as well as the desire to assist victims of and condemn US imperialism reverberated throughout the Second World.

Those in the decolonizing Third World tended to regard Vietnamese liberation fighters as “comrades of color” engaged in a shared global struggle against Western imperialism.Footnote 25 Although the term “Third World” originated with a French social scientist in 1952, it became a widely recognized political category and identity in the aftermath of the 1955 Afro-Asia Bandung Conference. Bandung sought to chart a third alternative for decolonizing nations, pressured to choose alliances between the First (noncommunist) and Second (communist) Worlds.Footnote 26 By the 1960s, particularly late in the decade, “Third World” described countries, movements, and peoples seeking decolonization in Africa, Asia, and Latin America (i.e., the Tricontinental) whether they were communist or capitalist. The term “Third World” was also used to characterize racialized people in the First World, particularly the United States, seeking to overthrow internal colonialism. Che Guevara presented this vision of tricontinental anticolonial solidarity in his statement calling for “two, three, many Vietnams.” He described this sense of anticolonial internationalism by asserting the interchangeability of Third World warfare:

the flag under which we fight would be the sacred cause of redeeming humanity. To die under the flag of Vietnam, of Venezuela, of Guatemala, of Laos, of Guinea, of Colombia, of Bolivia, of Brazil – to name only a few scenes of today’s armed struggle – would be equally glorious and desirable for an American, an Asian, an African, even a European.Footnote 27

Adding the phrase “even a European” suggested that the primary audience of Guevara’s appeal was for those in Latin America, Asia, or Africa or those who were descendants of these countries. Although there were racial and ethnic variations as well as political differences within and across these continents, Guevara’s statement nevertheless called for pancontinental solidarity across Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Locales within the Third World did help foster a global antiwar movement. Political icons such as Che and important organizations such as the Black Panthers promoted resistance against US policies in Vietnam. Also, Third World countries such as Cuba, Algeria, the People’s Republic of China, North Korea, and so on offered meeting sites and facilitated political contacts for antiwar activists around the world.

Nevertheless, there were important distinctions to note about these Third World expressions of solidarity. Zachary Scarlett argues that China’s interest in Vietnam stemmed from national political priorities of countering Soviet leadership in the Third World and promoting support for Mao Zedong in the midst of the Cultural Revolution.Footnote 28 Strategic representations of Vietnamese fighters helped to project “Maoism across borders and promoted the idea that Mao was the leader of the global revolution.”Footnote 29 Samantha Christiansen and Scarlett also suggest that there were crucial distinctions within the Third World during the post–World War II era. They identify a “first wave” of Third World nations that up to the mid-1960s “focused on the anti-colonial struggle for national independence.”Footnote 30 The second wave, in contrast, “fought against neo-colonialism and the project of the nation-state, which tended to subvert progressive activism in favor of stability.”Footnote 31 The Republic of Korea (ROK, i.e., South Korea) could be interpreted as a prime example of the neocolonial formation of the Third World nation-state. Characterized as a “subempire” of the United States, South Korea contributed more than 300,000 troops to fight with the United States and South Vietnam.Footnote 32 The South Korean soldiers were reputed to be among the most vicious fighters during the war. In addition, the Republic of Korea received approximately $1 billion from the United States in exchange for its military contributions. The money in turn helped to fuel the economic modernization of South Korea. The differing positions of the PRC and the ROK reveal that there was no natural alliance between Third World countries; the former supported the DRVN and the NLF but the latter supported the Republic of Vietnam and the United States. Each made its choice based on calculated political self-interest as well as ideological solidarity.

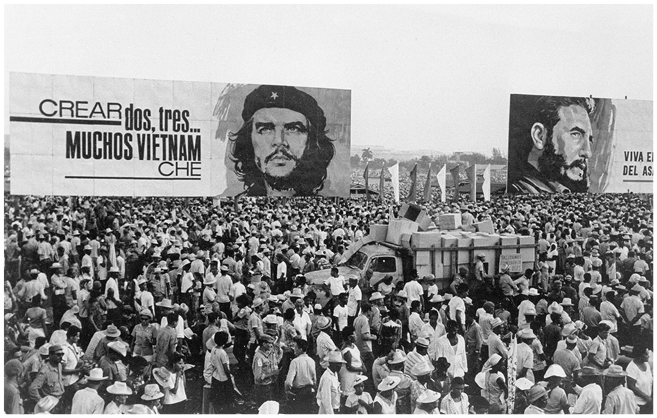

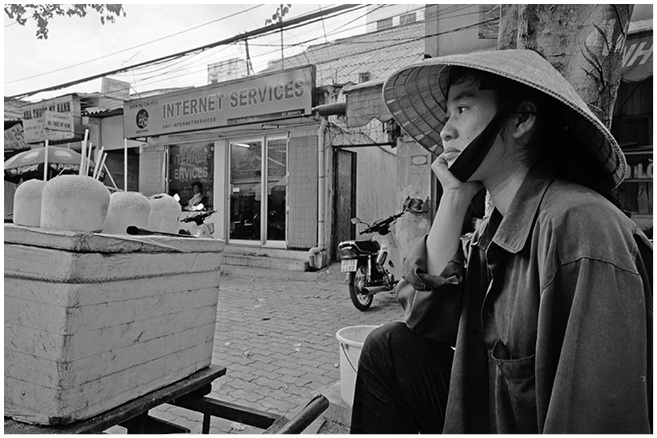

Figure 24.1 A crowd gathers in Havana, Cuba, to celebrate the fourteenth anniversary of the beginning of the Cuban Revolution in 1953. A banner showing Che Guevara urges the people of the Third World to create “two, three, many Vietnams” (July 26, 1967).

This periodization of the first wave (decolonialization up to the mid-1960s) versus the second wave (neocolonialism after the mid-1960s) of Third World development does not quite match Vietnam’s lengthy chronology fighting against Japanese, French, and US imperialisms. Nevertheless, Vietnam’s anachronism may help explain why it became such an important political symbol. As a country that experienced almost continual warfare for national liberation between 1941 and 1975, through World War II as well as the French Indochina War and the Vietnam War, Vietnam had the romantic revolutionary appeal of a not yet fully realized nation-state. The heroes and heroines of Vietnam’s liberation struggle became iconic “Third World Guerrilla[s]” and political role models.Footnote 33 Only after the reunification in 1975 did Vietnam become a “country,” not a “cause,” a consolidated nation-state with messy policies.Footnote 34 In the midst of the struggle for decolonization, however, Vietnam could generate internationalist solidarity and political sympathy across the First, Second, and Third Worlds for those who sought to condemn US imperialism, capitalism, and militarism.

The Heroism of the Subaltern and the Ubiquity of Anti-Imperialism

Along with Che’s “Two, Three, Many Vietnams,” Tom Hayden’s pronouncement at the 1967 Bratislava conference that “We are the Viet Cong now” became another important mantra of the antiwar movement. Viet Cong or VC was the shorthand term used by the US military, political leaders, and media to identify the Vietnamese who engaged in warfare against the United States and the Republic of Vietnam (RVN). Due to the nature of guerrilla warfare, the NLF were particularly denigrated for engaging in “sneak” attacks. “VC” more commonly described the fighters of the National Liberation Front rather than the regular troops of the DRVN, although the lines could be blurred. By claiming identification with the despised enemy of the United States, activists around the world declared their opposition to the US political and military establishment and those who supported their views. Instead, critics of US policies celebrated the heroism of the underdog, those with such unequal military power that they had to resort to guerrilla warfare. This identification facilitated the alliance with the VC of people experiencing oppression due to race, class, gender, religion, and/or political beliefs within their own societies. Like the Vietnamese, ostracized peoples around the world could be potentially capable of similar forms of heroism. The phrase “We are all the Viet Cong now” indicated that critics of US policies conceived of themselves as guerrilla fighters, too, engaging in a war against the war, opening an additional front behind enemy lines.

The dual meaning of the term “Third World” illuminates the connections that activists made between national liberation and racial liberation. The Third World referred to decolonizing nations in Africa, Asia, and Latin America as well as to people of color in the First World. While the former experienced colonialism on a global scale, the latter framed their oppression as a form of “internal colonialism.”Footnote 35 The connections between internal and global colonialism relied upon the intersections between race, economic exploitation, and political disfranchisement.

The Vietnam War, as argued by many activists, particularly those of Third World identification, was a racial war. The extensive bombing (triple the amount of tonnage used during all of World War II), the use of chemical weapons, the popular use of the term “gook,” and the dehumanization of the enemy all served to racialize the Vietnamese enemy as subhuman.Footnote 36 In addition, as a “working-class war,” US armed forces were composed disproportionately of the poor, the less well educated, and men of color.Footnote 37 As Martin Luther King, Jr., argued, the Vietnam War siphoned US economic resources away from the War on Poverty in the United States, thereby “devastating the hope of the poor at home”; furthermore, the conflict “was sending their sons, and their brothers, and their husbands to fight and die in extraordinarily high proportion relative to the rest of the population.”Footnote 38 In fact, the war ironically provided the US public with an opportunity to watch “Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same school room.”Footnote 39 In explaining why he resisted the draft, champion heavyweight boxer, Muhammad Ali, famously stated, “I ain’t got no quarrel with those Viet Cong.”Footnote 40 In a quote attributed to Ali and others, including the musical Hair, the draft represented “white people sending black people to fight yellow people to protect the country they stole from the red people.”

African American troops, along with other racialized soldiers, stationed throughout the world and fighting in Southeast Asia, experienced racism through the US military, through the conditions of war, and in their host societies. In response, activists in Europe, Canada, Japan, and elsewhere connected Black liberation struggles with antiwar activism. In Germany, for example, organizers reached out to US GIs, “particularly black soldiers,” to encourage political discussions about the war and to support desertion; one German activist argued, “this war in Vietnam is dirty and so is the American Army and what it stands for. American soldiers should be told how things are and what they can do to get out of that army.”Footnote 41 In fact, focusing on race in the US military merged the two most powerful movements of the 1960s, the antiwar and Black liberation movements. African American political leaders, including members of the Black Panthers, were popular if controversial speakers who traveled globally to speak to antiwar activists and US Black soldiers stationed around the world.

Antiwar activists also encouraged Chicano/Latino soldiers to think about the commonality between their status as colonized peoples in the United States and the status of the Vietnamese.Footnote 42 Similar to African Americans, Mexican Americans tended to face systemic discrimination and hence had lower socioeconomic status as well as fewer opportunities for college admissions. Consequently, Chicanos tended to be overrepresented in the military.Footnote 43 Chicano/a activists encouraged members of their community to question why they were fighting in the war. In 1970, they formed the only “minority-based antiwar organization, called the National Chicano Moratorium Committee.”Footnote 44 The Moratorium, held in Los Angeles, attracted an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 protestors, including elderly and children, the “largest anti-war march by any specific ethnic or racial group in US history.”Footnote 45

The depiction of Vietnamese as a racial other was profoundly connected to the racialization of Asians in the United States as well. Asian American soldiers were presented to other members of the US military as examples of what the Vietnamese enemy looked like.Footnote 46 No distinction was made between an Asian person serving in the US military (who was unlikely to be Vietnamese, given the ethnic composition of the Asian American population), a soldier in the Army of the Republic of Vietnam that was allied with the United States, a Vietnamese civilian, and a “Viet Cong” guerrilla fighter.Footnote 47 This racial lumping of all Asians as the enemy was reinforced by the US military practice of counting all dead Asians as VC.Footnote 48 Doing so inflated the body count and helped to broadcast the success of the war.

Scholars of colonialism have pointed out that both race and gender are intertwined with imperial and military processes. Similarly, the Vietnam War raised global awareness about the gendered impact of war. As Asian American antiwar activist Evelyn Yoshimura pointed out in her 1971 essay “GIs and Racism,” the representation of Asian women played a central role in the racial education of US military personnel.Footnote 49 Through the systematic creation of red-light districts in Asian countries where US troops were stationed, in what sociologist Joane Nagel calls the “military sexual complex,” the US military institutionalized a culture of American GIs frequenting Asian prostitutes.Footnote 50 Not limited to individual excursions, these practices became integral to military culture and discourse through ritualized retellings of these experiences. An Asian American marine recalled of his boot camp experience,

We had these classes we had to go to taught by the drill instructors, and every instructor would tell a joke before he began class. It would always be a dirty joke usually having to do with prostitutes they had seen in Japan or in other parts of Asia while they were stationed overseas. The attitude of the Asian women being a doll, a useful toy, or something to play with usually came out in these jokes and how they were not quite as human as white women … how Asian women’s vaginas weren’t like a white woman’s, but rather they were slanted, like their eyes.Footnote 51

Such racialized and sexualized depictions of Asian women, used to foster male bonding among US soldiers, shaped US military policies and practices in Southeast Asia – in the brothels and in the general prosecution of war.

Vietnamese women who suffered these practices helped to educate women around the world about the gendered impact of militarism as well as potential for women to combat the war. Vivian Rothstein, a member of the US SDS who had traveled to Bratislava in 1967, recalled that the Vietnamese women whom she met insisted on having women-only discussions with American representatives. This was unusual for Rothstein. She tended to work in mixed-gender settings as a student activist. Also, men and women both attended the Bratislava conference. However, the women from South Vietnam wanted to convey that the war had a unique impact on women. Rothstein recalled that they discussed how militarization fostered the growth of prostitution in South Vietnam. In addition, they provided examples of how American soldiers threatened and utilized rape as well as sexual mutilation as military tactics. Shaken and moved by these meetings, Rothstein requested an audiotape version of their presentation so that she might share their “appeal to the American women.”Footnote 52

These international dialogues between women of varying nationalities and racial backgrounds occurred throughout the war.Footnote 53 The Vietnam Women’s Unions (VWU) in the North and South reached out to women globally through women’s organizations, such as the Women’s International Democratic Federation, the Korean Democratic Women’s Union in the North, Women Strike for Peace in the United States, and the Voice of Women in Canada. The VWU also hosted visits to North Vietnam and sponsored meetings and conferences around the world.

Studies on global feminism and global sisterhood have noted the disproportionate power and the misperceptions of white middle-to-upper-class women from the “West” seeking to “rescue” oppressed Third World women.Footnote 54 This politics of rescue was not completely absent in the gendered political discourse of the war. For example, Gregory Witkowski points out that solidarity campaigns in East Germany, particularly in church-based campaigns, tended to portray “the deserving poor, primary women and children, who did not have the means to help themselves without external help.”Footnote 55 Quinn Slobodian coined the phrase “corpse polemics” to capture how West German activists increasingly showed “dead and mutilated” Third World bodies, thereby transforming “usually nameless and mute bodies into icons of mobilization.”Footnote 56

However, the agency of Vietnamese women in fighting the war and building a women’s global antiwar movement also reveals that these “Third World” women served as political mentors to women around the world. In fact, after Rothstein accepted an invitation to visit the DRVN after Bratislava, she observed how the VWU inspired and mobilized women to protect and transform their society. The VWU had chapters at various levels, ranging from local villages to the national level and operating in schools, workplaces, health clinics, and government units. In all of these settings, the unions trained women for political leadership and advocated for their collective interests. VWU representatives conveyed to Rothstein “how important it was to organize the women … and how powerful American women could be” as well.Footnote 57 When Rothstein returned to the United States, she went back to the “little women’s group” that she had participated in before she left. Inspired by her experiences in Czechoslovakia and North Vietnam, Rothstein proposed the formation of the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union, a group modeled on the VWU.

Vietnamese women not only inspired female activism around the world, but the political constructs of imperialism and colonialism were also utilized to characterize patriarchy and female oppression. Some feminist and lesbian organizations during the late 1960s and early 1970s argued that women constituted the original colonized subjects under male domination.Footnote 58 In fact, some called for a gendered liberation movement that was akin to the emergence of a “Fourth World.”Footnote 59 Just as the Third World asserted its autonomy from the United States and the Soviet Union, women, described as constituents of a Fourth World, sought self-determination and liberation.

The heroism of the subaltern had an appeal not only among racialized groups and women. The identification with the Viet Cong extended to individuals and groups who experienced marginalization due to a variety of factors. The French separatist movement in Canada, the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland, and the alienated youth of the New Left and counterculture around the world all proclaimed identification with the revolutionary Vietnamese and their cause.Footnote 60 Treated as outsiders and self-identified as colonized subjects, they allied with the enemy of their enemies, the revolutionaries seeking self- and national liberation.

Two, Three, Many Vietnams

The Vietnam War appealed broadly to radical activists around the world. It resonated differently depending on the geopolitical context, but the Vietnam conflict and the Vietnamese people drew worldwide attention, support, and sympathy. The North Vietnamese and those based in the South who resisted the United States and the Republic of Vietnam consciously cultivated these internationalist affinities. They assigned personnel and allocated resources to engage in formal as well as citizen diplomacy.Footnote 61 In addition to waging war on the battlefields and engaging in state-to-state negotiations, the NLF and the DRVN also prioritized a third front of mobilizing worldwide public opinion.

In addition to hosting diplomats and political visitors in North Vietnam, the DRVN and the NLF posted communication officers and sent diplomatic missions to Europe, Asia, Africa, Latin America, Australia, and Canada.Footnote 62 These representatives communicated not only with heads of state but also with individuals and organizations seeking information about the war in Vietnam. Pham Van Chuong, for example, worked for the Liberation News Agency of the NLF. He was posted in East Berlin during the early to mid-1960s and was then sent to Prague in 1965. Because Czechoslovakia was relatively easy for those from the West to reach, Chuong met with religious and pacifist delegations both in Prague and in other European cities. He recalled meeting well-known antiwar activists Dave Dellinger, Tom Hayden, Staughton Lynd, and Stewart Meacham of the American Friends Service Committee, as well as entertainers Jane Fonda and Dick Gregory.Footnote 63 In both North and South Vietnam, organizations were established to foster these international relationships. The Vietnam–America Friendship Association was created in 1945, soon after the founding of the DRVN. During the Vietnam War, the organization became the Vietnam Committee for Solidarity with American People or the Viet-My Committee. The NLF created a similar organization. Other groups fostering Vietnamese friendship with various nations were also established.

These citizen diplomacy efforts were perceived as a crucial part of the war effort. Trịnh Ngọc Thái, a former delegate at the Paris Peace Talks and the former vice chair of the External Relations Department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam, explained that the Vietnamese conceived of fighting the war on multiple fronts. He quoted Hồ Chí Minh, who identified two primary fronts: “the first front [is] against the US war in Vietnam, and the second one is inside the United States. The American people fight from inside, the Vietnamese fight from outside.”Footnote 64 Thái also quoted another Vietnamese leader who conceived of the war in three fronts: “one united front against the United States in Vietnam; one united front of Indochinese nations against the United States; and one front formed by the people in the world against US imperialism, for national independence, and peace.”Footnote 65 In either the two- or three-front formulation, the mobilization of US and worldwide public opinion was regarded as an important priority. As Thái notes, “the power of public opinions” could pressure US policy and military leaders. In addition, worldwide support served as “an enormous source of encouragement to the Vietnamese people and their armed forces in the battlefields. The world people’s support was very valuable both spiritually and materially to the Vietnamese people.”Footnote 66

Recognizing the impact of these global antiwar efforts, the US government and their allies also closely monitored the potential proliferation of two, three, many Vietnams.Footnote 67 Moshik Temkin points out how the French government surveilled American expats for their political activities and also attempted to control their travels.Footnote 68 Even Canada, formally neutral and a locale to which US draft resisters fled and where significant antiwar conferences were held, nevertheless engaged in covert military initiatives to support the US war effort and at times denied visas to Vietnamese spokespeople against the war.Footnote 69 During the period between the 1969 and 1971 conferences, a group of Vietnamese representatives were prevented the right of entry into Canada. They had planned to participate via closed-circuit television in the 1971 Winter Soldier Investigation, a three-day conference sponsored by Vietnam Veterans against the War in Detroit.Footnote 70 As a result of the denial of visas, the organizers of the 1971 Indochinese Women’s Conference had to balance their need to advertise these meetings to attract antiwar activists in North America and also prevent the Canadian government from excluding participants from Southeast Asia.

This concern about the proliferation of Vietnams stemmed from the ability of the war and the people engaged in fighting for national liberation to evoke political solidarity and sympathy across the First, Second, and Third Worlds. The Vietnam War graphically illustrated the militarized imperialism of the United States. The war also illuminated the ability of the subaltern to resist and even win against the most powerful country in the world. Vietnam gave those who experienced oppression and identified with the marginalized a sense of political hope and purpose. This belief in “everyday heroism” motivated activists around the world to read, think, protest, and organize. Through their collective efforts, they created a global public sphere that could broadcast critiques of the Cold War order, foster awareness of the interconnectedness of various forms of oppression, and possibly work toward creating a new and just world.

It hardly bears repeating that the danger of “falling dominoes” in Southeast Asia was not as acute as it seemed when the United States committed itself to a bloody conflict in Vietnam. What we know today of the relationship between North Vietnam (the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, DRVN) and its two key allies and sponsors, China and the Soviet Union, is enough to put to rest uncritical assumptions about a global, Moscow-directed conspiracy aimed at turning all of Southeast Asia into a sea of red. Finding themselves at odds with the Chinese and the Soviets, the Vietnamese communist leaders worked to preserve their freedom of maneuver while assuring the continuation of political support and the supply of economic and military aid from both. Hanoi kept its eyes on the prize: the defeat of the United States on the battlefield, a task that was possible only with allied support. Moscow and Beijing recognized the importance of this goal but their prize was Vietnam itself, that is to say, its loyalties in the unfolding Sino-Soviet split.

What was it about Vietnam that proved so important to its communist allies? There was a range of issues, from the geopolitical and security rationales to ideological zeal and the fates of world revolution. Historians have explored these questions in depth.Footnote 1 Acknowledging the importance of their contributions, this chapter makes the case for interpreting Chinese and Soviet policies in light of the narratives of political legitimacy. Much as was the case with American involvement in Vietnam, Beijing and Moscow understood the war in terms of opportunities for asserting their own, and undermining each other’s, credibility as an ally. Credibility was central to the Chinese and Soviet bids for leadership in the socialist camp and the Third World, while the notion of leadership was closely related to self-perceptions of legitimacy of the ruling elites. Their costly, long-lasting commitment to Vietnam was, in a sense, not about Vietnam at all: it was about the Sino-Soviet rivalry for leadership.

In the end, Moscow won the contest. Its victory was as much a function of the Soviet material commitment to Hanoi’s war effort as it was a consequence of China’s domestic meltdown. But it was a very costly victory. The Soviets became a party to a distant war that they could neither adequately control nor even fully understand.

A Slide into Conflict, 1960–1964

At the turn of the 1960s, the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and Chairman Mao Zedong of China were on parallel trajectories in Southeast Asia: both wanted to avoid conflict. In the late 1950s Khrushchev had his hands full with other problems. In 1958–9 he was preoccupied with the Berlin crisis, which he himself had started but was desperate to end, and with the unrest in the Middle East, which he did not start but hoped to turn to his advantage. In September 1959 Khrushchev traveled to the United States, meeting President Dwight D. Eisenhower. The positive spirit of their talks at Camp David imbued Khrushchev with hope that the Cold War itself could be quietly wound down, if only the Americans recognized Moscow’s legitimate interests. These did not include Southeast Asia in any meaningful way. By contrast, the Chinese were very interested in what transpired south of the border but primarily from the standpoint of national security rather than revolutionary strategy. China’s domestic difficulties – the failure of the Great Leap Forward – called for a cautious posture in foreign policy.

In the early 1960s North Vietnam drifted perceptibly in China’s direction. Those were the years of the Sino-Soviet polemics, when China openly challenged Moscow’s leadership in the international communist movement. Mao accused Khrushchev of betraying Marxism and colluding with the United States to sell out revolutionary movements around the world. This charge appeared all the more credible after Khrushchev’s capitulation in the Cuban Missile Crisis, in October 1962, when, under pressure from JFK, he had to remove nuclear-tipped missiles. If Khrushchev sold out Cuba, would he not sell out Vietnam as well? These were questions that the Chinese were now raising with the Vietnamese leaders, hoping to win their support.

Hồ Chí Minh was cautious. When Sino-Soviet relations came under strain because of Khrushchev’s falling out with Albania, he pleaded with the Soviet leader to forgive the Albanians. “If a tiger forgives the cat,” he told skeptical Khrushchev, “he will only become more glorious.”Footnote 2 Hồ Chí Minh was genuinely worried that the fracturing of the socialist camp would undercut Vietnam’s war in the South. Mao was unhappy. “Hồ Chí Minh,” he surmised in June 1962, “is afraid that, if N. Khrushchev expelled Albania today, he may tomorrow expel Vietnam too.” He went on: “In a meeting that Hồ Chí Minh had with me, I asked him, why are you afraid? In our country, in China, the grass is growing just fine even though N. Khrushchev is attacking and fighting us. If you do not believe this, go have a stroll around our mountains and see with your own eyes.”Footnote 3 Two months later, Chairman Mao proclaimed the return to class struggle in China’s foreign policy. Because of this new militant posture, and due to growing concern with the increased American presence in South Vietnam, the Chinese upped their political and military commitment to Hanoi.Footnote 4 Meanwhile, North Vietnamese requests for Soviet aid and cash went largely unanswered.Footnote 5

Mao and other Chinese leaders repeatedly assured the Vietnamese that they would back them in the conflict with the United States, even as the Soviets carefully probed for the possibility of a peaceful settlement. Unsurprisingly, by late 1963 the ranks of “pro-Soviet” Vietnamese leaders grew thinner, while the Chinese gained influence by the day. For a time, Hồ kept up the pretense of friendship with the USSR, blaming rumors of Hanoi’s anti-Soviet tilt on “hooligans and reactionary elements.”Footnote 6 But the Soviets knew that Hồ Chí Minh himself was “swimming between the currents” while others, including the Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP) general secretary Lê Duẩn, already “stood on the Chinese bank.”Footnote 7 “Pro-Soviet” players in the Vietnamese leadership reported feeling “complete isolation.”Footnote 8

It was not so much a matter of picking and choosing between ideologies, between embracing China’s “class struggle” and renouncing Khrushchev’s “peaceful coexistence.” The question was simpler: the North Vietnamese sought to take advantage of the deteriorating political situation in the South by launching an armed uprising, a decision formalized by a party plenum in December 1963. They needed political support and weapons, which the Chinese were happy to provide, even as Khrushchev, his eyes on better relations with the West, continued to procrastinate. Under these circumstances, North Vietnam’s siding with China was a tactical move in the absence of better options. Khrushchev himself precipitated this shift by ignoring his client’s needs. But, characteristically blind to his own policy failures, he blamed the loss of North Vietnam on the imaginary machinations of “Chinese half-breeds” in the Vietnamese party leadership.Footnote 9 For Khrushchev, the problem of Vietnam was only an aspect of his broader struggle with China, and a rather peripheral aspect at that. The Chinese worried about Vietnam much more, and for a good reason. The situation on the ground continued to deteriorate.

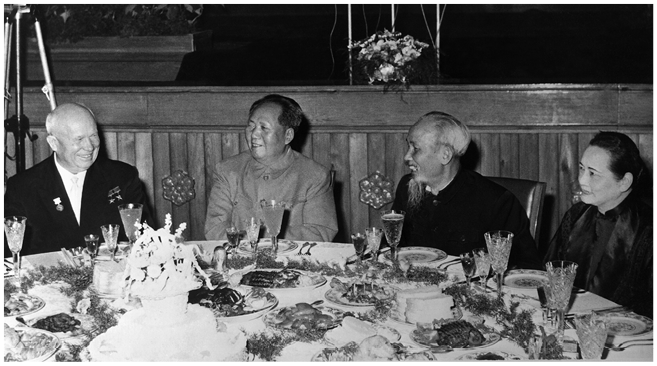

Figure 25.1 Premier Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union, Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, Hồ Chí Minh, President of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and Chairman of the Vietnam Workers’ Party, and Soong Ching-Ling, Vice Chairwoman of China (from left to right), dining together in Beijing (October 4, 1959).

The Struggle for Vietnam, 1964–1965

The rapid escalation of American involvement in Vietnam after the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964 meant that the war, which Mao and Khrushchev had so hoped to avert in the late 1950s, was now a brutal reality. Khrushchev witnessed the imbroglio from the political sidelines. In October 1964 his comrades-in-leadership overthrew him for reasons that had relatively little to do with foreign relations.Footnote 10 Meanwhile, Mao was egging the Vietnamese on. The escalating Vietnam War developed into the core concern of China’s foreign policy, becoming entangled imperceptibly with a very different struggle that unfolded in China itself. The Soviets half-suspected that the Tonkin Gulf incident was a secret Chinese ploy to prod Vietnam toward an open war with the United States and so instill their allegiance to, and dependence on, China.Footnote 11 There is no evidence of such devious plotting on Mao’s part. But once the war began in earnest, he embraced it with relish. As Mao famously advised the North Vietnamese in October 1964:

If the Americans are determined to invade the inner land, you may allow them to do so … You must not engage your main force in a head-to-head confrontation with them, and must well maintain your main force. My opinion is that so long as the green mountain is there, how can you ever lack firewood?Footnote 12

He preferred to keep the war confined to South Vietnam. But if it expanded to the North, that was fine, too, because the Americans would then find themselves knee-deep in a quagmire.

Three considerations underpinned Beijing’s approach to the deepening conflict. First, the Chinese believed that, for all the dangerous escalation, the chances of a broader regional (never mind a global) conflagration were minimal. The United States was already badly overextended. The more overextended it became, the lower its chances of winning. Speaking in the immediate aftermath of the Tonkin Gulf, Chinese premier Zhou Enlai outlined the stratagem in nearly poetic terms:

If there were just a few more Congos in Africa, a few more Vietnams in Asia, a few more Cubas in Latin America, then America would have to spread 10 fingers to 10 different places, spreading its power very thin … If we make America extend its 10 fingers to 10 different places, then we can chop them off one by one.Footnote 13

It did not matter to the Chinese how long the struggle would take – a hundred years or more, perhaps – but it would end in victory. It was imperative that the United States leave Indochina – indeed, not just leave, but, as Mao put it, “leave with shame.”Footnote 14 Mao valued the Vietnam War for the chance to “humiliate” the Americans, and so undermine their global influence.

Second, the struggle was a good thing because it helped mobilize the “people” – not just the Vietnamese but the Chinese too. The Vietnam War intersected with the trajectory of Chinese domestic politics. Mao’s leftward turn in domestic politics in mid-1962 stemmed from his dissatisfaction with the pace of his country’s revolutionary transformation. Mao now saw an opportunity to drum up support for more radical policies by invoking the threat of war. As he explained shortly after the Tonkin Gulf incident, “though the Americans cannot win in Vietnam, it is useful to have them there because ‘imperialism’ is necessary to unify revolutionary forces, and excesses of ‘imperialism’ are necessary to prove that socialism is the way of the future.”Footnote 15

Millions of Chinese took to the streets in August 1964 to “angrily denounce US imperialist aggression.” The DRVN Embassy in Beijing became a pilgrimage site for expressing officially sanctioned outrage, and for handing in thousands of letters of support, including one by a “78-year-old professor with a long silvery beard” and by a “12-year-old Young Pioneer who, in his summer vacation, had collected signatures to a pledge of support from 11 classmates.”Footnote 16 This outpouring of support was far from spontaneous. The massive demonstrations were organized by the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in order to “raise vigilance among the army and the people,” and to “educate [the people] about the concepts of national defence.” The instructions even included the slogans for the demonstrators’ banners: “Resolutely oppose,” “Resolutely support,” and, of course, “Long Live World Peace!”Footnote 17

Third, the war gave Mao an opportunity to assert leadership in the international communist movement amid the deepening conflict with the Soviet Union. The worse the fighting, the better were the grounds to claim that Khrushchev got it wrong: one could not have peaceful coexistence with the United States. By attempting to build bridges to the United States, Khrushchev had betrayed Vietnam’s hopes and the hopes of the entire revolutionary world. That was the message that the Chinese were now selling in Southeast Asia and further afield, and with some success. That said, the Chinese themselves were very careful to keep the war within certain bounds, and signaled to the United States that, as long as the Americans did not directly attack China, Beijing would not intervene. As Zhou Enlai put it in August 1964, “We do not provoke, but answer America’s provocation. As America takes one step, the people of China follow in taking one step … If America wants to expand the war, we will certainly resist.”Footnote 18 The message was reiterated through multiple channels, and it gave China’s policy greater nuance than one could extract from loud proclamations of solidarity.

Moscow’s approach began to change after Khrushchev lost power. The new Soviet leaders Leonid Brezhnev (as First and, later, General Secretary) and Aleksey Kosygin (as prime minister) made an effort to prove that they were truly committed to supporting an ally in need. In late 1964, Brezhnev and Kosygin tried to improve relations with both the Chinese and the Vietnamese. Unlike the former, who remained steadfast in criticizing Soviet “revisionism,” the Vietnamese leaders were eager to rebuild bridges with Moscow. Prime Minister Phạm Vӑn Đồng visited the Soviet Union in November and was promised help. In February 1965 Kosygin traveled to Vietnam. He was in Hanoi when the Americans began their bombing campaign in retaliation for an attack on a US helicopter facility near Pleiku by the National Liberation Front (NLF). This only served to increase the Soviet resolve to aid Vietnam. The underlying rationale for Moscow’s increased interest was that the Soviet leadership faced a deficit of political legitimacy. Aiding Vietnam in a war against “imperialism” helped them to be recognized – by their people, their clients and allies, and the broader world – as the legitimate heirs to the leadership of the socialist camp. An effort to improve relations with China also served the same purpose.

Mao, however, was not inclined to reciprocate. This became clear during Kosygin’s February 1965 trip to Beijing. Kosygin, who passed through China on his way to and from Vietnam, spoke of the need for “united action” to help Hanoi’s war effort. Zhou Enlai initially appeared sympathetic, even enthusiastic. During their meeting on February 10, 1965, Zhou readily agreed that the US bombing campaign gave Moscow and Beijing the freedom to offer the Vietnamese the unconditional support they needed. When Kosygin spoke of sending artillery, tanks, and surface-to-air missiles to North Vietnam, Zhou urged him to supply the equipment more quickly and promised China’s cooperation in transporting these weapons by rail.Footnote 19 If Zhou had actually been in charge of Chinese foreign policy, he and Kosygin could well have worked out a joint approach to North Vietnam, which was what the Vietnamese desperately wanted.

This was not to be. On February 12, 1965, Mao, responding to Soviet pleas with hostile sarcasm, told Kosygin that the Sino-Soviet struggle would last for 10,000 years. “The United States and the USSR are now deciding the world’s destiny,” Mao said acidly. “Well, go ahead and decide. But within the next 10–15 years you will not be able to decide the world’s destiny. It is in the hands of the nations of the world, and not in the hands of the imperialists, exploiters, or revisionists.” Mao appeared unconcerned by the new round of escalation in Vietnam – “So what? What is horrible about the fact that some number of people died?” – and countered Kosygin’s worries about the deepening conflict with optimistic calls for a “revolutionary war.”Footnote 20 Kosygin left Beijing disheartened and empty-handed. The tentative move toward Sino-Soviet rapprochement, of which Kosygin was a foremost advocate in the Soviet leadership, was peremptorily aborted.

The deepening crisis in Sino-Soviet relations made it more difficult for Moscow to supply military aid to North Vietnam. The Chinese flatly refused to establish air corridors for deliveries, held up trains, and rejected the Soviet proposal to cover the Sino-Vietnamese border against US air incursions as a hideous plot to put China under military control.Footnote 21 Still, such obstructionism actually helped Soviet standing in Vietnam, because it made it easier to accuse Beijing of hypocrisy: on the one hand, the Chinese propaganda hammered the Soviets for “selling out” Vietnam; on the other, the Chinese were demonstrably obstructing the delivery of vital supplies to an ally on absurd pretexts. Brezhnev used every opportunity to alert the Vietnamese to this discrepancy between Beijing’s words and actions. “Don’t think that I am trying to cause a quarrel between you and the Chinese,” he told North Vietnamese deputy prime minister and Politburo member Lê Thanh Nghị, when the latter turned up in Moscow in June 1965. “We are surprised and saddened that the Chinese leaders are willing to pay this price to achieve some kind of selfish aims.”Footnote 22

The Chinese, meanwhile, did their best to downplay the extent and the quality of the Soviet aid. “The Soviet leaders are not sincere or serious about providing help to Vietnam,” Zhou Enlai told Lê Thanh Nghị. Zhou reasoned that the Soviets had given Egypt, India, and Indonesia more than they were now giving Vietnam, and this was allegedly “so that Vietnam will not be able to fight big battles, so that it will not be able to start a war.” On the whole, Lê Thanh Nghị suggested in his written report on the trip, the Chinese were “displeased with our attitude toward the Soviet Union.”Footnote 23 This was hardly surprising. As Moscow increased the quantity and the quality of their military aid, providing equipment that China did not have and could not match, the Vietnamese began to move away from their pro-Chinese orientation. Understanding this, the Chinese even attempted to slow down or prevent altogether transport of Soviet weapons by rail, leading to a massive backlog of Vietnam-bound railcars on the Sino-Soviet border.Footnote 24 Moscow then began sending arms by sea – a circuitous and dangerous route. That only helped Brezhnev’s standing in the eyes of the Vietnamese, a reminder that Vietnam’s friendship could be bought if the price was right. Khrushchev had been unwilling to pay but his successors understood that the brutal war unfolding in Southeast Asia was a test of their credibility as the leaders of the socialist world.

War and Diplomacy, 1966–1968

The war continued to escalate. US ground troops carried on conducting combat missions against the NLF, with mounting casualties (with more than 6,000 dead in 1966, the American losses were more than three times greater than the previous year). Meanwhile, with brief respites in May and December 1965, bombs continued to fall on North Vietnam. Operation Rolling Thunder aimed at dissuading Hanoi from supplying their war effort in the South. But it did not work, not even when, in the summer of 1966, the Americans expanded the list of targets by bombing petroleum, oil, and lubricants (POL) facilities. The POL campaign came to an end in September, after a CIA study concluded that it did not significantly diminish Hanoi’s ability to fight. The US president faced divided counsel: Defense Secretary Robert McNamara had lost faith in the war by late 1966. Others, including prominently National Security Advisor Walt Rostow, were upbeat about the prospects. “My feeling is that the pressures on the regime may be greater than most of us realize,” Rostow told LBJ in September.Footnote 25 Yet, two years after the Tonkin Gulf, LBJ was beginning to waver, looking for a way out.

In public, Hanoi presented an impregnable façade of resolve. Summed up in Phạm Vӑn Đồng’s “Four Points” of April 8, 1965, this position called for the unconditional US withdrawal from Vietnam, followed by the country’s unification on communist terms. Continued escalation was spun as evidence of the United States’ growing difficulties, not just in public but also internally, for the benefit of the war-weary audiences in the socialist camp. Records of North Vietnamese discussions with the Soviet leadership often read like propaganda: so many airplanes downed, so many enemies destroyed, and not a word of one’s own losses. As Lê Thanh Nghị explained to Brezhnev in December 1965, “The American imperialists are suffering new defeats … As the latest fighting, and our observations show, American soldiers are afraid of dying in Vietnam. They cannot stand the difficulties and the losses, and cannot spend more than 3–4 days in the swampy areas, in the jungles.”Footnote 26

Careful Soviet probes about potential peace talks were met with stubborn rebuff, presented in terms of: yes, we are in favor of peace talks, but not now. This was the argument Phạm Vӑn Đồng cited to Brezhnev in October 1965 (Brezhnev was amused that the argument was made through the interpreter who read from a prepared text). “The Americans cannot be trusted,” Đồng said. “We don’t want to end up in a trap.”Footnote 27 He did not decipher this reference to a “trap” but, given Hanoi’s bitter experience at the 1954 Geneva Conference, where the North Vietnamese were arm-twisted by their allies into dividing the country along the 17th parallel, it is not surprising that they would be more suspicious the second time around. “An old story,” Brezhnev noted in his diary with evident resignation.Footnote 28

It was an old story but there was new blood spilled every day. Economic losses from bombing were partly made up for by a steady stream of economic aid from the socialist camp, especially the Soviet Union. But there was no making up for the tens of thousands of dead, maimed, and deprived. Recalled Janusz Lewandowski, Poland’s representative at the International Control Commission and (at one point) a crucial interloper in a failed attempt at US–North Vietnamese peace negotiations: “Population was starved, the rations were very limited, you know, the people gathered grass, herbs, finding the crickets … For every American, I think, there were a hundred Vietnamese killed.”Footnote 29 Although an exaggeration, the claim accentuates the brutal reality of war and helps us understand why, from late 1966, the North Vietnamese began sending signals of interest in peace talks. However, the signals were too weak and too equivocal to provide sufficient impetus for serious negotiation. That would have to wait for another two years of carnage and casualties, two years of internal deliberation centered in no small part on the question of China.

The Chinese persisted in their opposition to peace talks. They were at first quite successful. The Sino-Vietnamese relationship seemed to grow ever closer as the war intensified. DRVN leaders were frequent visitors in Beijing, informing, listening, consulting. “At present all the world is depending on you to defeat imperialism,” Chinese foreign minister Chen Yi told Hồ Chí Minh in June 1965, while Zhou Enlai and Deng Xiaoping warned him that Moscow would sell out Vietnam. Hồ Chí Minh played along but there was a perennial concern in Beijing that the Vietnamese might one day tilt the other way: toward the Soviets and toward peace talks. This helps explain the extraordinary lengths to which the Chinese went in trying to prevent the shipments of Soviet aid, and also in warning Hanoi not to take it. “Their help is not sincere,” Zhou cautioned Phạm Vӑn Đồng in October 1965. “The US likes this very much. I want to tell you my opinion. It will be better without the Soviet aid.”Footnote 30 Dong went on to Moscow, where, in talks with Brezhnev, he did exactly what Zhou hoped he would not – asked for aid – but also showed his loyalty by claiming commonality of views with the Chinese: “they have long been helping us.”Footnote 31

The DRVN’s dependence on Chinese aid – light weapons, ammunition, and daily necessities – could partly explain North Vietnam’s opposition to peace talks. This was the preferred Soviet interpretation: Brezhnev and Kosygin were ever prone to see the Chinese hand behind the Vietnamese recalcitrance. But that was not the whole story. Hanoi’s struggle lined up with Mao’s theory of the “people’s war.” When the Vietnamese leaders spoke in well-rehearsed catchphrases that sounded like Chinese propaganda, it was because they believed that propaganda, and were open to Chinese methods of guerrilla warfare. “Fighting a war,” Mao instructed Phạm Vӑn Đồng in April 1967, “is like eating: you eat a bite at a time. It is not hard to understand.”Footnote 32 The Vietnamese thanked Mao profusely for China’s help, and were invariably thanked in return: You are on the frontlines, Mao would say. You are waging the struggle against American imperialism.

In June 1966 Mao proposed to Hồ Chí Minh – half in jest, perhaps – that he would not mind heading down the Hồ Chí Minh Trail to carry on with the struggle. “We wouldn’t be able to vouch [for your safety],” Hồ Chí Minh replied in bemusement. Mao pressed on: “Isn’t this the same thing to die and to be buried in China as to die and be buried in Vietnam? It would be good to be killed by the Americans.”Footnote 33 Mao never went to Vietnam but hundreds of thousands of Chinese did. Between June 1965 and March 1968 a total of some 320,000 railroad, engineering, and minesweeping troops served in North Vietnam (the peak year was 1967, when the number reached 170,000).Footnote 34 One could say that the Vietnam War was organically linked to China in ways that it was not, and never could be, linked to the USSR. Even after the Vietnamese and the Chinese began to develop disagreements, it took years before they proved sufficiently serious to give the Soviets an opening in Vietnam.

Divergences did eventually spring up between Beijing and Hanoi, for two reasons. The first was China’s slide into the chaos of the Cultural Revolution. Begun in earnest in mid-1966, this campaign thrust China into radical violence. Senior leaders were purged. Those in “positions of authority” were beaten and tortured by radicalized youngsters. Convulsing in a bacchanalia of rallies and struggle sessions, China turned inward. All ambassadors but one (Huang Hua in Egypt) were recalled from overseas, and diplomacy was downgraded to revolutionary propaganda. The chaos decreased Beijing’s credibility as the DRVN’s protector. Disorder bordering on a civil war, especially in the southern provinces, disrupted the flow of weapons and supplies to Vietnam. Most importantly, Hanoi resented China’s efforts to “export” the Cultural Revolution, especially by relying on the local Chinese community and the railroad troops. There was, as Lê Duẩn put it in 1967, a “crisis of trust” between yesterday’s comrades-in-arms. In an even more telling assessment by the deputy Politburo member Nguyễn Vӑn Vịnh, “as paradoxical as it sounds, we [the Vietnamese] do not fear the Americans but fear the Chinese comrades.”Footnote 35

The second reason was Hanoi’s decision to begin peace talks with the United States in Paris. The discussions began on May 14, 1968, in the aftermath of the Tet Offensive. A brainchild of General Secretary Lê Duẩn, Tet had aimed at overwhelming US forces in South Vietnam in a series of powerful conventional strikes. The idea did not go down well in Beijing and in Moscow but for different reasons. The Chinese were upset that their preference for protracted guerrilla warfare had been ditched in favor of large-scale battles.Footnote 36 The Soviets had long sought a negotiated solution to the war, and did not like further escalation. But the failure of the Tet Offensive prodded Hanoi toward the negotiating table. The Soviets were relieved, and the Chinese outraged.

The Endgame

The DRVN presently showed a little flexibility, agreeing, for instance, to Saigon’s representation at the peace talks. More by innuendo than by diktat, the Soviets continued to encourage their allies to make concessions. Brezhnev was worried by Richard Nixon’s arrival in the White House. “We’ve known Nixon for a long time,” Brezhnev told Phạm Vӑn Đồng in November 1968, days after the Republican presidential nominee clinched victory. “He is distinguished by extreme self-love and great irritability … This does not mean that we are afraid of him. But one must take into account that, in a situation when no solution has been reached, he will have only one policy – to continue the war.”Footnote 37

But the North Vietnamese were not in any great hurry. They interpreted LBJ’s October 31 announcement of ending the bombing of North Vietnam as a momentous victory for the communist forces. “This new victory of ours,” Đồng told Brezhnev in November, “bred the spirit of confusion and decay in the ranks of the enemy, the American and the Saigon armies.” The initiative was in the Vietnamese hands. They had to press on.Footnote 38

Hanoi’s optimism came through in the Vietnamese Workers’ Party Politburo discussions. The records demonstrate that six months into the Nixon administration, the North Vietnamese remained upbeat about the near-term prospects of the ongoing war. This was due to the perceived weakness of South Vietnam’s armed forces, which were supposedly “falling apart,” with three of four top military commanders secretly supportive of the Viet Cong. According to the VWP Central Committee secretary Lê Vӑn Lương (who reported on these developments to the Politburo in early July), Hanoi’s problem was not so much in beating the “puppet” army as in working out what to do with them once they defected: how to feed them and how to sort the good from the bad.Footnote 39 Not long after this Nixon announced his policy of “Vietnamization” of the war: a phase-out of the US military presence accompanied by considerable strengthening of the South Vietnamese forces. Hanoi remained confident of victory just around the corner.Footnote 40

As the 1970s dawned, the end of war was finally in sight. Much of Indochina was in ruins but the North Vietnamese leaders looked forward to their long-sought victory, which would herald Hanoi’s rise to ranks of the leader of, and the socialist bridgehead to, the Third World. These ambitions were compatible with being a Soviet client. As a midsize power, the DRVN desired deference even as it itself deferred to the Kremlin for guidance. Vietnam continued to rely heavily on Moscow’s economic and military aid. Fiercely independent Hanoi accepted this dependence on Soviet largesse, partly because the Vietnamese had little choice, and in part because the Soviets were not competitors for Vietnam’s regional hegemony. Nor, ironically, were the Americans. With the United States on the way out and the Soviets in a detached, advisory role, though generous in contributing weapons, the politics of Southeast Asia were reverting to more ancient rivalries.

Unhealthy tendencies in Sino-Vietnamese relations, present during the early years of the Cultural Revolution, continued to worsen. The feeling in Hanoi was that the Chinese “support our revolution only to the extent to which we support the Cultural Revolution.” Zhou was apologetic, blaming the difficult political situation inside China. “The situation inside our party is very complicated,” he confidentially told the Vietnamese. “These difficulties have reached such a degree that they cannot be resolved at present.”Footnote 41 Externally China was also facing an unprecedented crisis. Following the Sino-Soviet border clashes in March 1969, it seemed that the Soviet Union would invade any moment.

Meanwhile, the Vietnamese were unhappy: not just with the collapse of Chinese aid, not just with meddling in Vietnam’s domestic politics, but with Beijing’s unwillingness to recognize the global importance of the Vietnamese revolution. China had long presented itself as the role model for revolutionary war. Mao instructed visiting revolutionaries – the Vietnamese among them – in the art of guerrilla warfare. The Chinese claimed leadership in the Third World partly by the right of their experience in the revolution and then the war with Korea, where China fought the Americans to a standstill. Now the Vietnamese were more than fighting the Americans to a standstill, emerging as yet another role model in Asia, another leader.

This rivalry was checked by continued Vietnamese obeisance and the decline of Chinese radicalism. In May 1970 Lê Duẩn found Mao more accepting of Hanoi’s conduct of the war and the peace talks in Paris. “You may negotiate,” he told Lê Duẩn. “I am not saying that you cannot negotiate.” “But,” Mao added, “your main energy should be put [into] fighting.” This was one of the last meetings between the Chinese and the Vietnamese leaders, when they still spoke from the same script. Mao was at his militant best: still berating the Americans and the Soviets, still upbeat about the prospects of the global revolution, still full of praise for the Vietnamese war effort. “Who fears whom? Is it you, the Vietnamese, Cambodians, and the people in Southeast Asia, who fear the US imperialists? Or is it the US imperialists who fear you? … It is a great power which fears a small country – when the grass bends as the wind blows, the great power will be in panic.” Lê Duẩn responded with deference and even requested “Chairman Mao’s instructions.”Footnote 42 Yet, even as he encouraged the Vietnamese to continue fighting, the Chinese leader was also carefully exploring the idea of rapprochement with the United States. This led in July 1971 to the bombshell China visit of Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, and the announcement that Nixon himself would soon come to Beijing.

Hanoi was flabbergasted. The Chinese had not consulted them before Kissinger’s trip, and Zhou’s reassurances about how Nixon’s visit to China would be of great benefit to Vietnam, and Beijing’s readiness to increase the aid flow, could hardly make up for the injury, and the insult, of such mistreatment. It was clear that Beijing and Washington had been talking, noted Hanoi’s chief peace negotiator Lê Đức Thọ days after Kissinger’s visit. “But the Chinese invitation to Nixon to visit Beijing was completely unexpected for us.” In November 1971 Phạm Vӑn Đồng visited Beijing in a bid to persuade the Chinese to uninvite Nixon.Footnote 43 In the words of General Võ Nguyên Giáp, who briefed Brezhnev and Kosygin on the visit several days later, Đồng “concluded that the general strategy of the Chinese leaders is a compromise with American imperialism.” “At whose expense will this compromise be reached?” interjected Kosygin. “It’s hard to say,” uttered Giáp. “I think you and I can guess at whose expense.”Footnote 44

As the Vietnamese leaders whetted Brezhnev’s appetite by invoking the bright prospects of a Soviet–Vietnamese revolutionary partnership in Asia, Hanoi’s relationship with Beijing was on a steep downward trajectory. The differences were still carefully papered over: not just in public but also, for the time being, in private. Mao, looking (in Lê Duẩn’s words) “old and very sick,” praised the Vietnamese leaders in a mawkish sort of way when they met in June 1973. “The people of the world, including the Chinese people and the Chinese party, have you to thank,” he said. “You’ve defeated the United States.” He even went as far as to thank the Vietnamese for the Sino-American rapprochement: “Think about it, why did Nixon come to Beijing? If you hadn’t won the war, he wouldn’t have come.”Footnote 45 What struck Lê Duẩn was that this time there was no discussion of the Soviet Union, no scaremongering about the Soviet threat, no pressure to combat “revisionism.” This was a sign of a broader shift in Chinese foreign policy – away from ideology toward Realpolitik. But what role would Vietnam play in this overtly geopolitical game?