Introduction

On February 1, 1942, revolutionary leader Hồ Chí Minh published a short article entitled “Our History Must be Studied” (Nên học sử ta). The article appeared in a newspaper that Hồ Chí Minh had established the previous year called Việt Nam độc lập, or Independent Vietnam. This newspaper was published in the northern province of Cao Bằng, where Hồ Chí Minh resided for a time in 1941 and 1942 after crossing the border from southern China to organize a united front against French rule and Japanese occupation known as the Việt Minh. Published three times a month with a run of 400 copies, Independent Vietnam’s reach was probably quite limited. However, the interpretation of the past that Hồ Chí Minh presented in this brief essay would be repeated countless times in the thirty years of revolution and war from 1945 to 1975, and it serves today as a key element in Vietnamese nationalism and identity.Footnote 1

The gist of Hồ Chí Minh’s view of Vietnamese history was summarized in the following two sentences that appeared at the end of the article: “Whenever our people unite as one, our country is independent and free. By contrast, whenever our people do not unite, we are invaded by foreign countries.”Footnote 2 The same issue of Independent Vietnam contained a list of “Ten Musts” (10 Điều nên) that was also penned by Hồ Chí Minh. These were ten acts that Hồ Chí Minh declared members of the Việt Minh must carry out: they must maintain the secrecy of the Việt Minh, they must be completely loyal to the Việt Minh, they must disseminate the aims of the Việt Minh, they must do their utmost to find new members for the Việt Minh, they must do their utmost to work for the Việt Minh, they must pay their dues on time, they must help each other, they must strive to study, they must read the books and newspaper of the Việt Minh, and they must support the newspaper of the Việt Minh.Footnote 3

Although Hồ Chí Minh argued in 1942 that the key lesson to learn from the Vietnamese past was that Vietnamese needed to unite to maintain the country’s independence, we can see today that what Hồ Chí Minh was attempting to unite in Independent Vietnam in 1942 was history and revolutionary politics. While one could argue that historical writings in Vietnam had always been political, earlier works had supported other types of politics, such as dynastic politics, and later, colonial politics. As such, to tell the story of the production of historical knowledge about Vietnam, as I will do in this essay, is to tell the story of the political history of Vietnam, and how the two processes have closely mirrored each other.

That said, the aim of this essay is not simply to point out how writings about Vietnamese history have been influenced by politics. Instead, its goal is to provide an historical background that will enable readers to better understand the articles in this Cambridge History of the Vietnam War. There are many ideas about Vietnamese history in the chapters following this one that are new. They are new not only because scholars have conducted new research and made new findings but also because there has been a movement away from certain “truths” that previously dominated writings on the history of Vietnam. In this essay, we will examine where those “truths” came from, and how they came to be adopted by scholars writing in English.

From Traditional to Modern Histories

The first histories produced by Vietnamese were dynastic histories. The two most important of these written prior to 1900 were the fifteenth-century Complete Book of the Historical Records of Dai Viet (Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư; hereafter Complete Book) and the nineteenth-century Imperially Commissioned Itemized Summaries of the Comprehensive Mirror of Viet History (Khâm định Việt sử thông giám cương mục; hereafter Comprehensive Mirror). These works were composed in classical Chinese, a language that only a small percentage of the population could understand. Each provided historical examples of good and bad governance, in the hopes that current dynastic officials would learn from the past.

Until the nineteenth century, Vietnamese history was thus a topic that was largely restricted to the world of court officials and the tiny literate elite aspiring to enter government service. While some Western missionaries and travelers learned what they could from local interlocutors, gaining access to actual historical texts proved to be difficult. That situation changed, however, with the French conquest of Vietnam. The extension of French control over Vietnam was a decades-long process but it began with treaties in the 1860s in which the ruling Nguyễn Dynasty granted the French direct control over the southern third of Vietnam, or what they called Cochinchine (Cochinchina). During this period, a French missionary by the name of Théophile Marie Legrand de la Liraye wrote the first history of Vietnam in French. While this work was based on Vietnamese sources, it nonetheless began a process of the “Westernization” of Vietnamese history in that Legrand de la Liraye employed European concepts to explain the past.

Whereas the Complete Book and Comprehensive Mirror documented a political genealogy from one ruling house to another, the purpose of Legrand de la Liraye’s work was to educate readers about the history of a people, or what he called the “Annamite nation.”Footnote 4 To do this, Legrand de la Liraye attempted to determine what race the Annamites belonged to so that his European readers could understand who these people were in relation to other racial groups in the region. These two concepts of nation and race were Western concepts, and they had never been previously applied to the history of Vietnam.

Another important idea that Legrand de la Liraye introduced to the writing of Vietnamese history was the concept of “independence.” There was a period in the early fifteenth century when the Chinese Ming Dynasty controlled the areas of what is now northern and north-central Vietnam. That brief period was brought to an end by a man named Lê Lợi, the founder of the Lê Dynasty. The Complete Book simply stated that Lê Lợi had “wiped out the Ming bandits” (tước bình Minh tặc 削平明賊).Footnote 5 By contrast, Legrand de la Liraye depicted that same historical event as a “war of independence” (guerre de l’indépendance). This was another new concept. Hence, when Hồ Chí Minh declared in 1942 that Vietnamese history was a timeless story of the Vietnamese people (dân tộc) uniting (đoàn kết) to maintain the independence (độc lập) and freedom (tự do) of the country, his interpretation of the past was filled with words and concepts that his ancestors would not have understood. That Hồ Chí Minh understood these words and concepts was because they all became part of the Vietnamese worldview during the years of French colonial rule.

Such ideas were adopted first in Cochinchina. There, the French established a new educational system, and in 1875, Trương Vĩnh Ký, a Vietnamese Catholic polymath, produced a history of Vietnam in French for the Vietnamese students there.Footnote 6 By 1906, a Vietnamese translation of a similar French-language history of Vietnam was published in Cochinchina, called a Brief History of the Country of Dai Nam (Đại Nam quốc lược sử).Footnote 7 In that same year, educational reforms were implemented in the center and north of Vietnam that sought to modernize the curriculum for the traditional civil-service examinations. In the late nineteenth century, the central and northern regions of Vietnam had both become protectorates of France.Footnote 8 Known as Annam and Tonkin, respectively, these regions were still governed by Nguyễn Dynasty officials, albeit under the guidance of French advisors. Proficient in classical Chinese, some of those officials learned a great deal about the West at that time through the writings of Chinese reformist intellectuals, and they transformed the educational curriculum in accordance with these new ideas.

A clear example of this is a work that was produced in 1906 and employed in the reformed curriculum in Annam and Tonkin by a scholar named Hoàng Đạo Thành entitled the Complete Compilation of the New Convention of Việt History (Việt sử tân ước toàn biên).Footnote 9 Hoàng Đạo Thành’s text was the first history created by a Vietnamese that was structured around the concept of the nation. It explicitly aimed to inculcate readers with a sense of pride in the nation. Whereas the Complete Book and the Comprehensive Mirror were designed to teach government officials about morally upright rule and the need to be loyal (trung) to the monarch, Hoàng Đạo Thành’s history was designed to teach students to be patriotic (ái quốc). This term for “patriotism” literally means “cherish the country.” It was a Western concept introduced to Vietnamese scholars through the writings of Chinese reformers, and it was a term that Hồ Chí Minh took as part of his revolutionary name, Nguyễn Ái Quốc, not long after Hoàng Đạo Thành produced his new account of the Vietnamese past.

Although Hoàng Đạo Thành’s history was a pioneering work, it was written at a time when classical Chinese started to lose its position of prominence in Vietnam. In 1909, colonial officials Charles Maybon and Henri Russier produced another new history of Vietnam in French for the revised civil-service exam curriculum. Entitled Ideas about the History of Annam (Notions d’histoire d’Annam), this work deliberately sought to present history following “European methods” of explaining the past and its importance rather than following what they criticized as the “Chinese model” of chronicling events.Footnote 10 They also sought to instill in their Vietnamese readers a sense of gratitude toward the French, rather than pride in the nation. While they acknowledged that there had been a “tendency towards unity” in the past, they nonetheless argued that true unity and independence only arrived in the nineteenth century as the French assisted Gia Long, the first emperor of the Nguyễn Dynasty, in establishing his rule over the entirety of Vietnam, and as the French forced the Qing Dynasty to terminate Vietnam’s status as a tributary state.Footnote 11

Such a view of the past was rife with contradictions, but this view was the norm from the 1910s through the 1930s. Although the civil-service exams were abolished in 1919, a system of Franco-Annamite schools with instruction in Vietnamese and French was established at that time, and an updated version of Maybon and Russier’s history continued to be employed in the curriculum for these schools. Also popular was a conservative rendering of the past by Vietnamese scholar Trần Trọng Kim, An Outline of the History of Vietnam (Việt Nam sử lược).Footnote 12

One could argue that by the 1930s there was a certain degree of stasis in the knowledge about the Vietnamese past. That intellectual stasis was a mirror image of the stability that had been established in colonial Vietnam and was supported by the individuals, both Vietnamese and French, who maintained the colonial order. However, in the 1940s, that colonial order was challenged, and as that happened, Vietnamese historical knowledge came to life.

Historical Writings of the 1940s

In the summer of 1940, France was occupied by Nazi Germany and a collaborationist government known as Vichy France was established. The Japanese took advantage of this political transition to move troops into French Indochina to block war supplies from reaching Republican China through the Hanoi–Kunming railway, as well as to prepare for their eventual occupation of the rest of Southeast Asia. Even as Vichy officials allowed what essentially became a Japanese military occupation, they attempted to challenge Japanese wartime propaganda that called for Asians to unite in opposition to the West. Vichy French colonial officials did this by promoting Vietnamese nationalism.Footnote 13

Certain Vietnamese intellectuals embraced this opportunity to express ideas that had previously been prohibited. With regard to historical scholarship, a journal called Trí Tân (New Knowledge) was established in 1941, and in the more than 200 issues that were published over the following four years, writers made initial steps toward moving historical knowledge out of the patterns into which it had fallen in the previous decades. In the very first issue, for instance, Ứng Hòe Nguyễn Vӑn Tố, a researcher at the École Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO), a research institute established by the French in the early twentieth century, wrote an essay that encouraged people to not use the term “Annam” to refer to the country. He produced historical evidence to argue that this was a term that the Chinese had created for Vietnam when it was under their control and that it had submissive connotations. Instead of using the term “Annam,” Nguyễn Vӑn Tố argued that historically the term that made the most sense to use was “Đại Nam,” meaning the “Great South,” a name that Nguyễn Dynasty emperor Minh Mạng had officially introduced in 1838.Footnote 14

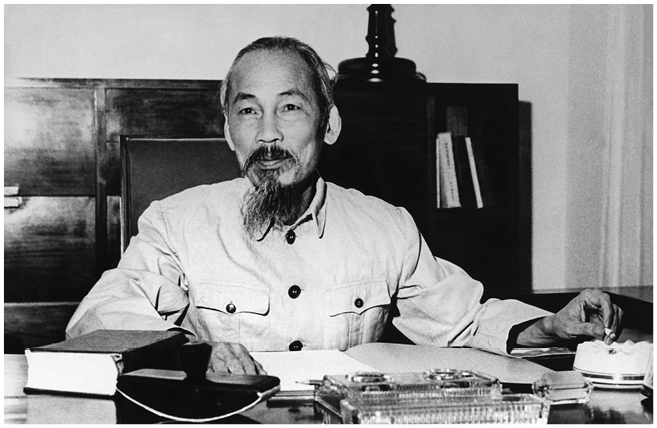

That Nguyễn Vӑn Tố did not suggest using the term “Vietnam” demonstrates how inchoate certain ideas about the nation and its past still were at that time. It is in this context that Hồ Chí Minh penned his article “Our History Must be Studied” the following year. He also wrote and published a poem at that time called “The History of Our Country” (Lịch sử nước ta) that summarized key events over the previous two millennia.Footnote 15 As in his article, Hồ Chí Minh emphasized the importance of unity and concluded the poem with an appeal for people to unify under the Việt Minh. In other words, Hồ Chí Minh attempted to identify a key element of the past – unity – and to declare that the Việt Minh had the mandate to realize that goal (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Hồ Chí Minh at his writing desk, probably in Tonkin c. 1950. A picture of Soviet leaders Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin hangs on the wall behind him.

This new interpretation of the past was one that many other Vietnamese shared. However, not all of them agreed with Hồ Chí Minh about the need to unify under the aegis of the Việt Minh. In March 1945, the Japanese took full control of French Indochina by imprisoning Vichy officials and ordering Nguyễn Dynasty Emperor Bảo Đại to declare Vietnam’s independence. A government was quickly formed with historian Trần Trọng Kim serving as prime minister. While Trần Trọng Kim’s own history of Vietnam was conservative in its approach, a certain Nguyễn Duy Phương quickly produced a new history of Vietnam to mark the establishment of this new government and the country’s nominal independence. Entitled The History of the Independence of Vietnam, Nguyễn Duy Phương sought to place the Trần Trọng Kim administration at the end of a long line of historical struggles for independence.Footnote 16 That said, at only twenty-six pages, and undoubtedly written in a hurry, Nguyễn Duy Phương’s history offered cursory and uneven coverage of the past. It began with a discussion of the Trưng Sisters’ struggle against Han Dynasty rule in the first century CE and then discussed other instances of resistance during the millennium of Chinese rule. This was followed by a detailed discussion of Lê Lời’s struggle against the Ming in the early fifteenth century. The text concluded with some brief comments about the colonial period.

Trần Trọng Kim’s government did not last long, but the model for writing about the Vietnamese past that first emerged in the 1940s with the brief writings of Hồ Chí Minh and Nguyễn Duy Phương did. In August 1945 Japan surrendered and the Việt Minh declared Vietnam to be independent under its authority. This of course was challenged by the French and the French Indochina War began late the following year. While some intellectuals joined the Việt Minh, others remained in French-controlled territory. One such person, Phạm Vӑn Sơn, took this time to write a more comprehensive history of Vietnam than either Hồ Chí Minh or Nguyễn Duy Phương had been able to produce. Entitled A History of Vietnamese Struggles, Phạm Vӑn Sơn’s work likewise focused on the topic of struggles for independence and resistance to foreign attacks. It began with a discussion of the Trưng Sisters, whom Phạm Vӑn Sơn referred to as “the two Joan of Arcs of Vietnam.” He devoted chapters to wars with the Chinese and the Cham and detailed the various “independence movements” (vận động độc lập) that arose between 1861 and 1945. The various revolutionary parties that sought to bring about independence in the first half of the twentieth century were also discussed, as was the August Revolution of 1945. Uncertain which direction Vietnam would take in the future, Phạm Vӑn Sơn provided chapters in his book on Emperor Bảo Đại, who had just agreed to work with the French to establish the State of Vietnam, and Hồ Chí Minh, who was fighting the French.Footnote 17

Historical Scholarship in South Vietnam

Phạm Vӑn Sơn’s A History of Vietnamese Struggles was first published in Hanoi in 1949. When the French Indochina War ended in 1954, Phạm Vӑn Sơn followed hundreds of thousands of other people in migrating to the South. His text was subsequently republished numerous times in Saigon. Meanwhile, Phạm Vӑn Sơn continued to write new works, including a multivolume survey of Vietnamese history entitled A New Compilation of Việt History that began to appear in 1956.Footnote 18 As such, Phạm Vӑn Sơn’s scholarship can be seen as representing a continuation in South Vietnam of an approach to writing about the past that had ties to earlier periods, as it perpetuated certain ideas that had been produced by historians during the colonial era, under the Trần Trọng Kim administration and the State of Vietnam. In this way, Phạm Vӑn Sơn’s writings were not unlike the government of South Vietnam, which built on the expertise of men who had served in earlier regimes.

At the same time, however, historians in South Vietnam, like their government counterparts, also contributed to the process of decolonization. While they built on, and cited, the work of colonial-era scholars, South Vietnamese historians also sought to produce new historical scholarship that could help create a national spirit (tinh thần dân tộc) for their young nation. The University of Hue, established in 1957, set this process in motion. It employed an historian from Taiwan who had spent time at the EFEO in the 1940s, Chen Jinghe, to lead a group of scholars to start cataloging and translating Nguyễn Dynasty documents. It also produced a journal called University (Đại học) that published articles on topics ranging from French philosophy to Vietnamese linguistics and history. One of the early issues included an article by a young historian who had recently returned from graduate school in Belgium, Trương Bửu Lâm, that called for a new national history curriculum.Footnote 19

The University of Huế was supported not only by the South Vietnamese government but also by foreign organizations such as the International Rescue Committee, The Asia Foundation, the Committee of the American Sponsors of the University of Huế, and the American Friends of Vietnam. It was part of a Cold War effort to build a democratic and prosperous South Vietnam. That effort started to falter, however, as the university became embroiled in the tumultuous events of 1963 that led to the assassination of President Ngô Đình Diệm in November of that year. The university’s Catholic rector, Cao Vӑn Luận, was dismissed by President Diệm for supporting the Buddhists, and although he was briefly reinstated after Diệm’s assassination, the times had changed. University ceased publication and the Nguyễn Dynasty historical sources project was discontinued.

This was not, however, the end for historical scholarship in South Vietnam. On the contrary, professors and students at Saigon Normal University collaborated to start publishing a journal in 1965 called History and Geography (Lịch Sử và Địa lý). This journal was published continuously until 1975 and it featured the work of historians who had come of age during the colonial era, such as Phạm Vӑn Sơn, Hoàng Xuân Hãn, Hồ Hữu Tường, and Phan Khoang, as well as a new generation of South Vietnamese historians, such as Tạ Chí Đài Trường and Nguyễn Thế Anh. In an effort to create a sense of a national spirit, albeit one with a southern emphasis, these historians published articles on famous figures in Vietnamese history, such as Trương Công Định, a Nguyễn Dynasty official who led a resistance war against the French in Cochinchina in the 1860s, Phan Thanh Giản, a Nguyễn Dynasty official who committed suicide in 1867 for failing to prevent the French from gaining control of Cochinchina, and Nguyễn Huệ, the leader of the Tây Sơn Rebellion.Footnote 20

Historical Scholarship in North Vietnam

Like their counterparts in South Vietnam, Historians in North Vietnam were eager to produce historical writings to educate the population under their control. However, whereas South Vietnamese historians built on the work of colonial-era scholars, the historians in North Vietnam sought to make a deliberate break with the world of colonial scholarship. They criticized the “colonial mindset” of EFEO scholars and strove to produce scholarship that was free of colonial influence. Ironically, North Vietnamese historians attempted to do this by closely following another foreign model of knowledge production, Marxist historiography, which they learned from Chinese and Soviet writings.

This process formally began in 1953, when the French Indochina War was still underway, with the establishment of the Institute of History. Scholars affiliated with this institute set about discussing various issues that their Chinese and Soviet counterparts were debating, such as how to periodize Vietnamese history following Marxist stages of development, and how to determine when the Vietnamese nation was first formed, using Stalin’s definition of a nation. The various viewpoints that scholars proposed were published in a journal called Literature, History and Geography (Vӑn sử địa).Footnote 21

Some historians also worked on producing surveys of Vietnamese history. The first to do so was a man who wrote under the name of Minh Tranh (Khuất Duy Tiễn). In 1936 Minh Tranh became a communist, and during the French Indochina War he served as a propagandist, journalist, and editor for the Việt Minh. He was also a committee member of the Central Department of Literary, Historical and Geographical Research (Uỷ viên Ban Nghiên cứu Vӑn Sử Địa Trung ương). In 1954 Minh Tranh published a book entitled a Draft Brief History of Vietnam (Sơ thảo lược sử Việt Nam) that was meant to serve as a history textbook for schools in North Vietnam. This work closely followed Marxist theory. It divided Vietnamese history into periods of primitive communism, slave society, feudalism, etc., and highlighted peasant rebellions as examples of the struggle of the working class against the oppression of the feudal elite.

Two years later, in 1956, historian Đào Duy Anh published another survey entitled the History of Vietnam (Lịch sử Việt Nam). Đào Duy Anh saw value in the Marxist approach to history; however, he felt that Marxist theory had to be adapted to the Vietnamese context rather than rigidly imposed, and this survey was essentially devoid of Marxist theory. Further, in an interview published that same year in the journal Humanities (Nhân Vӑn), Đào Duy Anh criticized the restrictions being placed on scholars at that time.

This journal was one of two journals (the other being Giai Phẩm, or Masterpieces) that critiqued government restrictions on artistic and intellectual life following the French Indochina War. The North Vietnamese government cracked down on this critique, an event that is known as the Nhân vӑn–Giai phẩm Affair. In 1958 Đào Duy Anh’s scholarship was denounced, and Minh Tranh’s Draft Brief History of Vietnam was upheld as an ideal model for the writing of Vietnamese history. However, that honor did not last long – Minh Tranh was demoted in 1963 for his “revisionist” view against expanding the war in the South.Footnote 22

Both these men were in their fifties when they were demoted, and a new generation of historians in their twenties emerged to take their place. In the early 1960s, for instance, archaeologist Hà Vӑn Tấn and historian Trần Quốc Vượng published a volume on early history called the History of the System of Primitive Communism in Vietnam (Lịch sử chế độ cộng sản nguyên thủy ở Việt-Nam) and contributed a volume on early history to a three-volume history entitled the History of the Vietnamese Feudal System (Lịch sử ch́e độ phong kiến Việt Nam).Footnote 23 The second volume in this series, on premodern history, was authored by historian Phan Huy Lê. Meanwhile, the final volume, on modern history, was written by Phan Huy Lê, Chu Thiên, Vương Hoàng Tuyên, and Đinh Xuân Lâm.Footnote 24 Four of these men – Hà Vӑn Tấn, Trần Quốc Vượng, Phan Huy Lê, and Đinh Xuân Lâm – would continue to produce historical writings for decades to come and came to be known as the “Four Pillars of the Field of History” (Tứ trụ sử học).

Although the titles of these works indicate an effort to follow the ideas of Marxist historiography, with the expansion of the war in 1963 historians in North Vietnam abandoned the strict adherence to Marxist theory that Minh Tranh had promoted in the 1950s in favor of a more nationalistic approach to the past. North Vietnamese historians ceased writing about class divisions and conflicts and focused instead on unity. Further, the Sino-Soviet Split, the Cultural Revolution, and Nixon’s visit to China were all events that gradually introduced an anti-China element in historical writings. This topic was broached in subtle terms in the mid-1960s as historians began to write about a history of “resistance to foreign invasion” to mobilize the population, but it eventually reached extreme levels during and after the 1979 border war with China.

An additional important development in this period was an intense focus on ancient history. A series of conferences were held in Hanoi in the late 1960s and early 1970s in which scholars from various fields sought to prove that the earliest rulers in the Red River Delta, the mythical Hùng kings, had truly existed. Here the work of North Vietnamese archaeologists was particularly important as they tried to find material evidence for the existence of these rulers that could make up for the absence of solid textual information. In the end, archaeologists did find many artifacts, but nothing that could unquestionably prove the existence of the Hùng kings. As such, while scholars initially sought to verify that these kings had existed, they ended up declaring that “the period of” the Hùng kings had existed. Nonetheless, that was sufficient to serve the nationalist need of the moment to rally people behind the war effort by pointing to the supposed antiquity of the Vietnamese nation with its heartland in the Red River Plain.

In the 1970s, these developments culminated in what we can consider the orthodox history of Vietnam as it is known in Vietnam today. This view of the past argues that there was a unified and culturally and linguistically distinct group of people who lived in the Red River Delta long before the Chinese Qin and Han dynasties extended their control into the region at the end of the first millennium BCE. This group of people endured a thousand years of Chinese domination, but emerged again as an independent nation, and that nation has been fighting off successive efforts by foreigners to encroach on their land ever since. Finally, in the twentieth century, this Vietnamese orthodox history argues, the task of resisting foreign invasion was led by the Communist Party.

This is the interpretation of the past that Hồ Chí Minh argued in 1942 the Vietnamese needed to know. By the time the Vietnam War ended in 1975, the inhabitants of half of what is now Vietnam had been taught this version of history for a good twenty years. In the years that followed, the other half of Vietnam was introduced to this interpretation of the past. To launch this effort, in 1976, the Institute of History in Hanoi published a book entitled The Country of Vietnam is One, the People of Vietnam are One (Nước Việt Nam là một, dân tộc Việt Nam là một). In it, the anonymous collective authors argued for the historical unity of Vietnam, and highlighted the Communist Party’s role in unifying the country.Footnote 25

Anglophone Histories of Vietnam

As the above discussion should make clear, the version of Vietnamese history that gained prominence in Vietnam after 1975 has its own long, complex history. By contrast, writings about the Vietnamese past in English have a shorter history. However, in the years following the end of the Vietnam War, these writings likewise culminated in a kind of “official” version of the Vietnamese past, one that mirrored the official version in Vietnam in significant ways.

When the US government first intervened in Vietnamese affairs in the 1950s, there was very little information available in English about Vietnamese history. Over the subsequent two decades, various writers and scholars tried to fill this gap. Lacking knowledge of the Vietnamese language, the earliest English-language writers relied heavily on the work of a very limited number of scholars writing in French, such as Lê Thành Khôi, an expatriate Vietnamese in Paris, and Paul Mus, a French scholar and colonial official.

The first survey of Vietnamese history in English was Joseph Buttinger’s The Smaller Dragon: A Political History of Vietnam.Footnote 26 Buttinger was an Austrian-born socialist politician who fled his home country in 1938, first for France and then the United States. During World War II, Buttinger started working for the International Rescue Committee (IRC), an organization that aided refugees. In 1954 the IRC sent Buttinger to South Vietnam to assist the government in settling the hundreds of thousands of refugees who moved south of the 17th parallel under the Geneva Accords. This was Buttinger’s first exposure to Vietnam, and he was so impressed by the country and its people that he spent the next four years reading everything he could find in Western languages on Vietnam and writing a survey on Vietnamese history.

In researching and writing this book, Buttinger was particularly influenced by a survey of Vietnamese history published in 1955, Lê Thành Khôi’s Vietnam: History and Civilization, the Environment and History.Footnote 27 Lê Thành Khôi was born and raised in Hanoi but then went to study in Europe where he received a Ph.D. in economics in Paris in 1949 and then went on to study international law at the Hague. Vietnam: History and Civilization was his first work of history. Influenced to some extent by Marxist theory, Lê Thành Khôi argued that French colonization had led to the emergence of a bourgeoisie and a proletariat, but a sense of romanticism for the past led him to play down the existence of any class antagonisms in the precolonial period. He was similarly positive about a future under a “Marxist democracy” in “the new Vietnam,” the topic of his brief concluding chapter.

Buttinger did not reproduce Lê Thành Khôi’s views, but he did rely heavily on Vietnam: History and Civilization to create a basic narrative of the Vietnamese past. Buttinger’s work also mirrored that of Lê Thành Khôi in that it focused primarily on premodern history, and in fact, only provided a chronology of events for the twentieth century. In a footnote, Buttinger blamed French scholars for an imbalance in historical information about Vietnam, as he argued that the French, “in accordance with French colonial policy,” had “consistently ignored the reality of Vietnamese nationalism” and the many developments that led to its rise. “In short,” he noted, “they ignored the development of the forces that they had to fight after 1945.”Footnote 28

When war did break out after 1945, there was one French scholar who did seek to understand the forces that the French faced in Vietnam: Paul Mus. Born in France but raised in Hanoi, Mus became an expert on early India and Southeast Asia and was employed by the EFEO. He then fought in various capacities in World War II, served as a political advisor for the high commissioner for Indochina in the immediate postwar years, and finally returned to academia, teaching both in France and at Yale University. Warfare and the August Revolution of 1945 had a transformative effect on Mus’s ideas.Footnote 29 Unlike many of his contemporaries, Mus took Vietnamese nationalist aspirations seriously and even came to empathize with the Vietnamese.Footnote 30 At the same time, however, his positive views of the Vietnamese and their anticolonial struggle were still framed in Orientalist terms that explained to his Occidental readers how these, albeit dynamic, Oriental people thought.Footnote 31

As the Vietnam War got underway, Mus’s description of the Vietnamese struck a chord with his students in the United States, particularly Frances FitzGerald who visited Vietnam in 1966 as a journalist and went on to publish a Pulitzer Prize-winning work on the Vietnam War and its historical background, Fire in the Lake: The Vietnamese and the Americans in Vietnam.Footnote 32 This book begins with a chapter entitled “States of Mind,” and following Mus, to whom the book is dedicated, Fitzgerald describes the Vietnamese world as one that functions based on a different logic. With numerous references to texts and ideas in the Sinitic cultural tradition, from the Yijing, or Classic of Changes, to the idea of the Mandate of Heaven, Fitzgerald describes a world of thought and action that is completely alien to the American experience.

Ultimately what FitzGerald and many others who followed argued is that Vietnam was a country that Americans simply did not understand, and that once they did understand Vietnam better they would see that it was a foe the United States could not take lightly. This latter point was highlighted in an extremely influential work by George Kahin and John Lewis entitled The United States in Vietnam. Although the authors did not know Vietnamese, their depiction of Vietnamese history was strikingly similar to the interpretation that Hồ Chí Minh in 1942 argued that his compatriots must adopt. Like Hồ Chí Minh, Kahin and Lewis viewed Vietnamese history as a long story of efforts to resist foreign intrusions and to maintain the independence of the country, arguing that “for many centuries a basic and constant theme of [Vietnamese] nationalism was freedom from China’s domination,” and that with the end of colonial rule, “this theme reasserted itself with traditional vigor.”Footnote 33 One difference with the past, according to Kahin and Lewis, was that now nationalism had “fused” with communism.Footnote 34 Their message was thus that the Americans were facing a foe that for millennia had fought off previous attempts by foreigners to control their land.

This vision of the Vietnamese past became extremely popular among members of the antiwar movement, and over time, it made its way into countless publications, two of the most influential being Stanley Karnow’s Vietnam, a History and Marilyn Young’s The Vietnam Wars, 1945–1990.Footnote 35 Such works were often produced by authors who did not know Vietnamese. Meanwhile, in the 1970s and 1980s there were scholars proficient in the language who produced more grounded studies of the Vietnamese past. Nonetheless, many of these studies focused on gaining a better understanding of the communist side, and in so doing perpetuated Hồ Chí Minh’s interpretation of the past that placed the communists at the center of Vietnamese history.

Since the 1990s, there has been a new wave of Anglophone scholarship on Vietnamese history. Produced by scholars who write in English but who read Vietnamese and who have conducted extensive archival research, this body of scholarship has moved away from the essentialized renderings of the Vietnamese and Vietnamese history that were produced in and outside of Vietnam in the twentieth century. This work has eschewed the depiction of the Vietnamese past as a perpetual struggle against foreign domination; it has also challenged the habit of depicting the communists as the primary drivers and central actors in twentieth-century Vietnamese history. In these accounts, modern Vietnamese history appears as a much more complex tale of multiple efforts to build Vietnam based on competing visions of the future. This scholarship, in turn, has opened up new perspectives on the history of the Indochina Wars – including the “Vietnam War” that began in the late 1950s and continued until 1975. In the chapters that follow, readers will find many instances of these new perspectives and the historical insights that can be gleaned from them. These new perspectives and insights are undoubtedly very different from what Hồ Chí Minh had in mind when he declared in 1942 that “our history must be studied.” But they are no less a part of the still-unfolding tradition of seeking to understand Vietnam through its vibrant and fascinating history.

Scholars have long viewed the history of the Vietnam War as deeply entwined with the history of the Vietnamese Revolution. But what was this revolution, when and how did it begin, and what were its defining features? While some have depicted the revolution as the culmination of a centuries-long process of national formation, many more have depicted it as a reaction to colonial rule and the creation of French Indochina during the last decades of the nineteenth century. Recently, however, postcolonial scholars have critiqued the view of the Vietnamese Revolution as nothing more than a “response” to European conquest. This chapter does not seek to identify a singular moment of revolutionary origins, nor does it depict Vietnam’s revolution as a necessary or inevitable response to “foreign invasion.” Instead, I chart the complex political, economic, and cultural changes that transformed Indochina between the 1860s and the 1920s, paying particular attention to the strikingly different effects that these changes produced in the five regions (pays) of France’s colonial empire. By 1930, many Vietnamese had embraced revolution, but the implications and direction of the country’s revolutionary politics – and the fate of colonial rule in Indochina – appeared more uncertain than ever.

Vietnam on the Eve of French Conquest

Contrary to what some later observers supposed, the colonial-era division of Vietnam into the three regions of Tonkin, Annam, and Cochinchina was not a French innovation. It replicated the administrative structure devised by Emperor Gia Long when he established the Nguyễn Dynasty in 1802. Gia Long’s newly unified empire was much larger than the realm that his ancestors had established in the coastal region below the 18th parallel two centuries earlier, when they separated from the northern Viet kingdom based at Hanoi. While Gia Long’s court, now located in Huế, ruled the central region directly, one viceroy was appointed for the North and another for the South. The position of northern viceroy was abolished in 1817 but that of southern viceroy lasted until 1832. By the time the Nguyễn kingdom first came under French attack in 1858, the empire had been administratively unified for only twenty-four years. Still, the memories of this unity would nourish nationalist sentiments in the twentieth century.

Despite its heavy reliance on revenues from mining in the Northern Highlands,Footnote 1 the Nguyễn Dynasty idealized the village-based agrarian society of the Red River Delta. In northern villages, distrust of outsiders accompanied communal solidarity. Rural trade was hampered by geography and seen mostly as a remedy for poverty.Footnote 2 For ordinary residents, the path out of both village and poverty was through education and bureaucratic appointment. But in the central region with its long coast and lack of arable land, the Nguyễn ancestors to the nineteenth-century emperors had maintained the Cham tradition of long-distance maritime trade. Meanwhile, since the late seventeenth century, an influx of Chinese immigrants made possible the expansion of Nguyễn rule southward, into the fertile Mekong Delta. In response to demand for rice in Southeast Asia, canals were dug to drain swamps, bring new land into cultivation, and facilitate the transport of rice to Saigon for export.Footnote 3 In this ever-changing landscape, Vietnamese, Chinese, and Khmer peasants were constantly on the move. Unlike their northern and central counterparts, southern villages were open but lacked the former’s communitarian ethos. A scarcity of imperial officials and Confucian educators hampered the court’s efforts at administrative control and ideological conformity. Economic success rather than educational achievements and bureaucratic appointment was the chief means of social advancement. French colonial policies would exacerbate these pre-existing regional differences.

French Cochinchina Before 1885

The ill-defended southern region was the first to fall to French conquest. In 1862, the Treaty of Saigon ceded the region’s three eastern and most populous provinces to the French. In 1867, having already installed a protectorate in Cambodia in 1864, the French seized the remaining three provinces of the west. The flight of Vietnamese officials to the still-independent northern and central regions contributed to turning the Vietnamese south into the colony of French Cochinchina.

Under French rule, Cochinchina was first divided into thirteen then eventually twenty provinces. Each was governed by a French administrator. Below him were other French officials; Vietnamese were only allowed to perform clerical duties or to hold purely honorific titles. At first, the colony was governed by an admiral. In 1879, after Jules Ferry became French prime minister, a civilian governor was appointed by Paris and an elected Colonial Council was created to make the governance of the colony more democratic. Only six of the Council’s fourteen (eventually eighteen) members were Vietnamese and these were elected by a restricted pool of property-owning electors. The Colonial Council sent one delegate to the Chamber of Deputies in Paris. When France decided to resume expansion in Vietnam, the settlers objected to using the Cochinchinese budget to fund the Tonkin campaign of 1883–5. Paris reacted by replacing the colony’s first civilian governor, le Myre de Vilers, with a more compliant one.Footnote 4

Colonialism’s economic impact on the economy of Cochinchina was immediate and long-lasting. From the outset, the French had systematically seized lands whose owners had fled the conquest or who had stayed to oppose them. Once the western provinces of the Mekong Delta were annexed, agricultural settlements that had been opened to bring more land under cultivation were also confiscated on the grounds that their ownership had been transferred from the Court to the new authorities. The pre-existing network of canals was greatly expanded.Footnote 5 To hasten large-scale export-oriented agriculture, lands, either confiscated or newly brought into cultivation, were auctioned off as lots whose size and price put them out of the reach of ordinary Vietnamese. Many small cultivators lacked proper titles for the lands they had reclaimed and lost them to unscrupulous speculators and corrupt officials. Scandals associated with land grabbing were a recurring theme of southern politics throughout the colonial period. The growth of large landholdings encouraged the twin phenomena of landlessness and absentee landlordism.Footnote 6

Other far-reaching changes came in the realm of culture. The system of Confucian education, culminating in bureaucratic employment, held little attraction for the southern peasants and merchants. It was thus easy to jettison the traditional curriculum. The earliest French-affiliated institution of new learning, the Catholic Collège d’Adran, was founded in 1861 even before the Treaty of Saigon was signed. By 1869, Cochinchina counted 126 public schools where Vietnamese students were taught in the Romanized script (quốc ngữ). After the third grade, students could transfer to more advanced schools in which the language of instruction was French, though few did. The first such school, the Collège Chasseloup-Laubat, opened in Saigon in 1874. In 1879, the Collège de Mỹ Tho was established on the prior foundation of a primary school to serve the needs of students from the Mekong Delta. In 1882, Jules Ferry mandated universal education in France and pushed for opening more public (and secular) schools in the colonies.Footnote 7 New Franco-Annamite schools were thus opened throughout Cochinchina – though they catered mainly to the children of wealthy Vietnamese and Chinese (Figure 2.1).

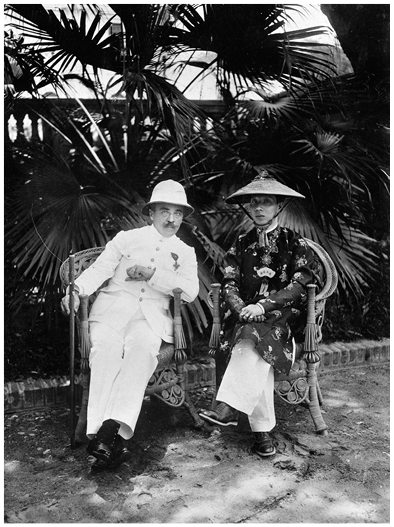

Figure 2.1 The governor-general of French Indochina, Albert Sarraut, with Emperor Khai Dinh of Annam (April 1918).

In 1865, the Vietnamese Catholic polymath known as Petrus Trương Vĩnh Ký began publishing Gia Định Báo (Gia Dinh Journal). Printed in quốc ngữ, it functioned as an unofficial journal of record. Besides official notices and legal documents, the weekly journal, which ran until 1897, published articles on agriculture and culture.Footnote 8 Beginning in 1879, all official documents were issued in French and quốc ngữ, thereby cementing the latter’s use as the script for communicating with and among Vietnamese. By the time French colonial conquest resumed in the rest of the country in 1882, the Vietnamese south had already experienced profound political, economic, and cultural transformations that magnified previous differences with the rest of the country.

The Conquest of Tonkin and Annam

After the French annexation of the southern provinces, the rest of the country fell prey to economic difficulties, rebellions, and factionalism among court officials. Owing to the chronic indecisiveness of Emperor Tự Đức (1847–83), his court failed to take advantage of the hiatus in France’s colonial expansion between its defeat in the war with Prussia of 1870 and Jules Ferry’s assumption of the premiership in 1879. Although the Vietnamese court had previously sought assistance from China in vain, in 1883, a new appeal found a favorable response among conservative Qing officials, leading to war between France and China. But the Sino–French war ended badly for Vietnam. The Treaty of Tianjin of June 1885 affirmed the French annexation of the remaining Vietnamese territory and its division into the protectorates of Tonkin and Annam in the North and center respectively.

The following month, several attempts to restore the Nguyễn monarchy to power, known collectively as the Aid the King Movement (Cần Vương), were launched.Footnote 9 Imperial regents whisked the twelve-year-old emperor Hàm Nghi to the hills of central Vietnam to lead the struggle, but his absence from the court gave the French a pretext to enthrone his elder half-brother Đồng Khánh. From Đồng Khánh onward, Vietnamese emperors ruled in name only, with effective power residing in the hands of French officials.

In 1887, the colony of Cochinchina and the three protectorates of Cambodia (since 1864) and of Tonkin and Annam (since 1885) were brought together in a new entity, the Indochinese Union, to which Laos was added in 1893. A governor-general was appointed at the head of the Union, above the governor of Cochinchina and the French résidents supérieurs of the four protectorates. Although the governor-generals initially resided in Saigon’s Norodom Palace (later Independence Palace), the capital of the Union was moved to Hanoi in 1902.

Although the traditional imperial bureaucracy was preserved in both Tonkin and Annam, each protectorate had its own political and administrative regime that was headed by a French résident supérieur. In Tonkin, each province remained nominally administered by a Vietnamese governor (tổng đốc), but actual power was exercised by a French résident, the equivalent of a Cochinchinese administrator. The résident supérieur governed with the assistance of an advisory council that, unlike the Cochinchinese Colonial Council, was neither elected nor endowed with the power of the purse. In Annam, the seat of the Nguyễn court, there was no French administrator below the résident supérieur. But that official had total, if indirect, control over the Nguyễn court bureaucracy. He presided over meetings of the imperial cabinet and set their agenda. Vietnamese ministers were barred from introducing any new item for discussion and were especially prohibited from discussing matters of personnel or taxes, including their amount, collection, or distribution.

During these decades, few Vietnamese living in Tonkin or Annam ever saw a French official or settler. They experienced colonialism indirectly as Vietnamese prefects and magistrates continued to discharge their functions as before, albeit while taking their orders from the colonial rather than imperial state.Footnote 10 While Vietnamese officials were subservient to the French authorities, many abused the power they wielded within their local jurisdictions. As a result, in the two protectorates, traditional governance – and the Confucian ideology on which it was supposedly based – became indelibly and negatively associated with colonial rule.

When the Aid the King Movement ended in 1895, the Indochinese government switched from pacification to economic exploitation. In 1897, a new governor-general, Paul Doumer, set about reforming the Indochinese budget, which depended heavily on subsidies from the metropole. He introduced new taxes, including monopolies of opium and salt. Later, alcohol was added to these two sources of revenue (although policing them turned out to be quite costly).Footnote 11 A new bureaucratic apparatus, the general services, was created to administer projects that transcended state borders, but also to solidify the position of the governor-general over the heads of the five states of Indochina, in particular the governor of Cochinchina. The colony contributed 40% of the Union’s budget; consequently, the Cochinchinese settlers and their representatives in both Saigon and Paris exerted enormous power over the affairs of the Indochinese Union. The general services enabled the governor-general to siphon off revenues from Cochinchina, mitigate the influence of the settlers, and restrict the power of the governor of Cochinchina.

In Tonkin and Annam, land plots tended to be small and property registers were better kept than in the developing Mekong Delta and thus did not attract land speculators. The socioeconomic landscape changed more gradually than in Cochinchina, but the new taxes weighed more heavily on their inhabitants than on those of the South, where greater social (and geographical) mobility accompanied rapid development. Although the colonial administrators stopped above the village level, French rule had a profound impact on rural life in both regions. Peasants in Tonkin and Annam existed at subsistence level, their crops often mortgaged before they had ripened, in order to pay their taxes. In the early 1880s, the colonial authority introduced a series of measures to increase tax revenues. First, the census, which determined the amount of taxes owed by each village, was no longer conducted by village councils but by agents of the state. It was no longer possible for the councils to minimize their villages’ tax liability by underreporting population figures. The traditional distinction between registered peasants who had the right of citizenship in their village and those who were nominally exempted from taxes because of their supposedly transient status (a situation that could persist over three generations) was gradually eliminated; every villager was now a taxpayer. Furthermore, a new tax was introduced as replacement for the traditional corvée, which was usually performed by villagers in the offseason and close to home. As the large-scale projects undertaken by the general services required year-round manpower, coerced labor details known as corvée remained a hated feature of rural life until the end of the colonial period. Under the new system, peasants were forcibly recruited, even kidnapped, to work on projects far from home for long periods and were severely punished for breaking contracts.Footnote 12

While they no longer conducted the census, village councils remained responsible for collecting taxes and remitting them in full. The introduction in 1897 of tax receipts as forms of identification opened villagers to new exploitation by village councilmen. Having previously served as buffers against the imperial state, they now became reviled as rapacious agents of the colonial regime. In 1927, the colonial regime introduced a measure to shore up the representativeness of village councils in Tonkin, but their prestige continued to decline. Throughout the 1920s, the northern Vietnamese press routinely called for reforming village government.

Reform and Collaboration

The end of the Aid the King Movement coincided with Japan’s victory over China in 1895. These two events convinced the traditionally trained scholars who made up the leadership of the movement to abandon its purely restorationist objectives and to embrace cultural reform as a prerequisite for independence. Inspired by Chinese reformers such as Liang Qichao, they jettisoned the ideal of social harmony as the organizing principle for society and replaced it with Social Darwinian notions of racial competition. They accepted that Vietnam had fallen to colonial conquest because its civilization had become stagnant and unable to compete against a more vigorous West.

The first advocate of reform was Phan Bội Châu (1867–1940). After the end of the Aid the King Movement in which he had played a minor role, he concentrated on his studies and obtained a degree in the regional examinations of 1900. In 1903, he penned the first of his appeals for reform. This was A New Letter from Ryukyu Written in Blood and Tears (Lưu Cầu Huyết Lệ Tân Thư). In it, he drew parallels between the loss of Ryukyu’s annexation by Japan in 1879 with Vietnam’s own loss of independence to the French. He echoed Chinese reformers’ calls for immediately developing the people’s intellect and cultivating the people’s strength. The following year, he created the Reform Society (Duy Tân Hội) whose main activity was the Eastern Travel Movement (phong trào Đông Du), aimed at bringing young Vietnamese to Japan to acquire a more modern education than was available in Vietnam. The most noteworthy of these students was Prince Cường Để (1882–1951), a direct descendant of the Nguyễn dynastic founder. But while the aim was to send students abroad from the two protectorates, most of the Vietnamese who joined the Eastern Travel Movement came from the more prosperous South. This pattern of southern support for Phan Bội Châu would continue throughout the first decades of the twentieth century and shape his politics. Not long after his arrival in Japan, Phan Bội Châu wrote another pamphlet, A History of the Loss of Vietnam (Việt Nam Vong Quốc Sử) for which Liang Qichao wrote a preface. Liang also had it printed and distributed as far as Korea. Both the New Letter from Ryukyu Written in Blood and Tears and the History of the Loss of Vietnam were written in classical Chinese, the language in which Phan Bội Châu had been educated. Although an ardent advocate of quốc ngữ, he never learned it.

The other towering figure of the reformist movement, Phan Châu Trinh, likewise wrote in Chinese. Born in 1872, Phan Châu Trinh had been too young to participate in the Aid the King Movement. His father had, however, been assassinated by fellow insurgents. Unlike Phan Bội Châu who was willing to resort to violence in the pursuit of independence, Phan Châu Trinh renounced it entirely. Blaming the monarchy for his father’s assassination, he became an ardent advocate of republicanism. And while Phan Bội Châu saw cultural reform in purely utilitarian terms as a useful instrument for political action, Phan Châu Trinh believed that independence could only be sustained after a thorough process of cultural change that might last decades. To the dismay of Phan Bội Châu, whom he met in both Japan and China, he distrusted Japan and was willing to learn from the French.Footnote 13 In 1907, Phan Châu Trinh became involved in the Tonkin Free School Movement (Đông Kinh Nghĩa Thục) which advocated the spread of quốc ngữ as a bridge between the elite and ordinary Vietnamese. The Tonkin Free School operated impromptu classes that not only taught quốc ngữ but also introduced new ideas from East Asia and Europe. Several of its leaders were graduates of the School of Interpreters that had opened in Hanoi in 1886 to train intermediaries between the French authorities and imperial officials. The school’s curriculum combined a smattering of Chinese, quốc ngữ, and French with new subjects of study, so its graduates became known as scholars of New Learning. Some members of the Tonkin Free School also opened businesses, both to provide financial support for its operations and to elevate the status of trade and traders.Footnote 14

The reforms advocated by the Tonkin Free School aimed to replicate developments in Cochinchina, where the use of quốc ngữ was widespread and commerce and entrepreneurship had always enjoyed popularity. Gia Định Báo had ceased publication in 1897, but some of its mission was resumed in 1901 with the launching of a new journal, Nông Cổ Mín Đàm (Forum for Agriculture and Commerce). Like Gia Định Báo, it was written entirely in quốc ngữ. It had few paid subscribers but a wider readership. As its title indicated, it aimed to promote the interests of Vietnamese farmers and businesspeople. It provided regular information about the price of rice for export and advice on agricultural matters, but it also devoted columns to cultural issues. It published translations of Chinese historical novels such as the Romance of the Three Kingdoms and short stories from Chinese, French, or English, as well as original poems; it also reproduced news from European newspapers. Fully two pages were taken up by advertisements. There was nothing like it in Tonkin or Annam.Footnote 15

The reformers’ educational enterprise included a significant innovation. Women had traditionally been barred from taking the civil service exams; their education had been limited and haphazard, focusing mainly on moral prescriptions and domestic advice. It turned out that women, who were not tied to a Chinese-language education, were quicker learners of the Romanized script than the men. Thus, when he found out that his daughter was already fluent in the new script, Lương Vӑn Can put her in charge of the women’s section of the Tonkin Free School.Footnote 16

A Collège du Protectorat (colloquially known as Trường Bưởi) was established in 1908 in Hanoi to cater to Vietnamese students. In Huế, the Imperial Academy (Quốc Học) was founded in 1896, but it began actual operations only in 1909. The limited availability of Franco-Annamite education in Tonkin and Annam was due not only to their protectorate status but also to the persistence of the traditional civil service exam system as the means of staffing the imperial bureaucracy. The system continued to function for an entire decade after its abolition in China. The last regional exams were held in the North in 1915; but only in 1919 was the last metropolitan exam held in Huế.

In addition to building new institutions, the reformers also sought to transform Vietnamese mores. They encouraged their peers to cut their hair and nails short and embrace Western-style modernity. Paradoxically, in the South, where all the measures advocated by northern reformers had long taken hold, some chose to express their patriotism by clinging to traditional hair and clothing styles and to profess allegiance to the Vietnamese monarchy that no longer reigned over the colony.

For all the publicity it generated then and later, the Tonkin Free School Movement lasted only one year. In 1908, the last significant armed revolt against French conquest ended after a plot to poison the colonial garrison in Hanoi was uncovered and its mastermind, Đề Thám, was captured. The same year, peasants in Annam staged protests against the corvée and against the introduction of a new currency that severely disadvantaged them. Leaders of the Tonkin Free School lent their support by writing poems and songs that the colonial authorities deemed subversive. Phan Châu Trinh and other supporters of the protests were arrested and the classes of the Tonkin Free School were shut down. The University of Hanoi (actually School of Medicine), which had opened in 1902 to address Vietnamese calls for educational reforms, was also shut down and did not reopen until 1917. Scholars of New Learning such as Nguyễn Vӑn Vĩnh and Phạm Duy Tốn, who had enthusiastically embraced the Movement because it vindicated their own educational trajectory, took fright. While many continued to pursue cultural endeavors, they largely ceased to be involved in what might be deemed political activism.Footnote 17

Meanwhile, in 1909 Phan Bội Châu was expelled from Japan at the behest of the French colonial authorities. After wandering in Siam (where many former participants in the Aid the King Movement had taken refuge) and Hong Kong, Phan Bội Châu settled in South China. He quickly immersed himself in the political activities of the Vietnamese émigrés there as well as in Chinese politics. An enthusiastic supporter of the 1911 Revolution that ended Manchu rule over China, in 1913, he tried to form an anticolonial movement that drew its inspiration from Sun Yat-sen’s Revolutionary Alliance (Tongmenhui). However, its proposed republican platform encountered opposition from his southern supporters who furnished him with the bulk of his funds. To placate them, he placed prince Cường Để at the head of the League for the Restoration of Vietnam (Việt Nam Quang Phục Hội). Seeking to publicize the new organization, he encouraged a bomb plot in the Saigon–Cholon area. This was carried out through the intermediary of the clandestine Heaven and Earth Society. The Society, which originated in China, had replaced its anti-Manchu slogan (“Fight the Qing, Restore the Ming”) with an anticolonial one (“Fight the French, Restore Vietnam”). Phan Xích Long, the local mastermind of the bomb plots, was arrested before the plot could be carried out while Phan Bội Châu was sentenced to death in abstentia.Footnote 18 The French authorities were able to convince the governor of Guangdong to arrest him, but not to deport him back to Vietnam. Phan Bội Châu spent the next four years in a Chinese prison.Footnote 19

These waves of anticolonial activity made it difficult for the new governor-general, Albert Sarraut (Figure 2.2), who arrived in Indochina in 1911, to implement his program of economic development (mise en valeur) of the colonies. Sarraut’s plan relied on mollifying native populations with concessions to promote social stability. But it soon ran afoul of the French settlers’ belief that social unrest should be met with severe reprisals. By the time ill-health forced Sarraut to return to France in 1913, he had not been able to accomplish much in the way of reforms, though he succeeded in releasing Phan Châu Trinh from prison. Phan Châu Trinh left for Paris and was even given a subsidy (it was withdrawn when World War I broke out).

Figure 2.2 A Franco-Annamite school in Đồng Khê (Upper Tonkin) in 1902.

French Indochina initially refused to become involved in the metropole’s war with Germany but changed course in 1915. The government immediately set about rounding up “volunteers” to serve on the front or relieve French workers in factories. Eventually, 94,000 such volunteers, the overwhelming majority coming from Vietnam, went to France during the Great War.Footnote 20 Although they were supposed to go of their own free will, in fact, most were conscripted, sometimes even kidnapped. Riots broke out throughout the country. In Cochinchina, anticonscription protests merged with an attempt by members of the Heaven and Earth Society to spring Phan Xích Long out of the Central Prison of Saigon in 1916. Eventually, thirty-eight men involved in that failed attempt were publicly executed. In Annam, too, political unrest was rife. The sixteen-year-old Emperor Duy Tân was persuaded by a Taoist scholar, Trần Cao Vân, to plot an attack on French military installations in Annam. When the scheme was discovered, Duy Tân was sent into exile together with his father Thành Thái, whom the French had deposed in 1907 after he called on the French to restore prerogatives that by treaty were supposed to be reserved for the court.

In August 1917, a revolt took place among colonial troops stationed in Thái Nguyên in the north. The insurgents made common cause with some of the political prisoners detained in the prison, notably Lương Ngọc Quyến, the son of the reformist scholar Lương Vӑn Can. The authorities dealt with the uprising with ferocious intensity, mobilizing 500 troops who, in the space of five days, razed the town that had given shelter to the insurgents.Footnote 21 The French authorities and settlers usually described incidents of unrest as either expressions of opposition to colonialism (as would Vietnamese historians later) or as purely local disturbances caused by dissatisfaction with specific policies. In the case of the Thái Nguyên uprising, there was ample reason to lay the blame on the French résident, Darles, who mistreated both prisoners and colonial troops equally. At the same time, the presence of political prisoners also suggested that the uprising had been inspired in part by anticolonial sentiments. Albert Sarraut, who had arrived back in Indochina in January 1917, chose to interpret the uprising as a purely local affair. It is likely that his choice was motivated by his desire to implement the program of “Franco-Annamite collaboration” he had proposed prior to the war (Figure 2.2).

The New Journalism: Politics vs. Culture

The post–World War I situation made Sarraut’s program of collaboration seem more necessary and more possible. Even after Governor-General Paul Doumer had tried to put the finances of Indochina on a sounder footing, the colony had continued to depend on subsidies from the metropole. Given the parlous state of the postwar French economy, reducing Indochina’s financial dependence on Paris was imperative. Sarraut proposed to institute a constitution that would give Indochina greater independence from Paris in return for becoming financially self-sufficient. The colonial state also faced a dearth of European personnel, due to the staggering casualties sustained on the battlefields of Verdun and the Somme.Footnote 22 This meant appointing Vietnamese to positions hitherto reserved for French people. It also spurred educational reforms that greatly increased the number of schools in Cochinchina and extended the system of Franco-Annamite education to Tonkin. In Annam, where the last traditional metropolitan exam was held in 1919, the classical curriculum was reformed to purge it of anticolonial elements. In a bow to girls’ education, the Đống Khánh School opened in Huế in July 1917.Footnote 23

To advance his program, and to counter the opposition of the French settlers that was even more virulent than in 1913, Sarraut courted the Vietnamese elites of Cochinchina and Tonkin with notable success. In Cochinchina, the rising middle class had achieved political visibility by enthusiastically voicing its patriotism toward “the mother country” (mẫu quốc) of Great France (Đại Pháp) and buying war bonds. Sarraut’s main supporter was Bùi Quang Chiêu, whose biography suggests the educational gulf that existed between Cochinchina on the one hand and Tonkin and Annam on the other. Bùi Quang Chiêu was born in Bến Tre in 1867, the same year as Phan Châu Trinh. But while Phan Châu Trinh in Quảng Nam received a traditional education culminating in a degree in 1902, Bùi Quang Chiêu went to Algeria in 1894 and graduated three years later with a degree in agronomic engineering. Back in Vietnam, he was an enthusiastic supporter of the reform movement, particularly of the Tonkin Free School. Albert Sarraut tapped him to become the editor-in-chief of the French-language newspaper La Tribune Indigène for which the colonial regime provided generous subsidies (paid for by villages, which were required to purchase the newspaper though their residents were largely illiterate even in their own language). In 1919, the newspaper announced that it was the organ of the Constitutionalist Party and openly supported Sarraut’s attempt to forge an Indochinese constitution. The newspaper benefited from the policy of relative press freedom that allowed French-language newspapers to discuss economic and political matters. La Tribune Indigène advanced the interests of Vietnamese landowners and businessmen against both the French settlers who had their own mouthpieces in several newspapers and against the Chinese businessmen who dominated the economic sector, especially the rice trade. In 1919, the newspaper spearheaded a boycott of Chinese businesses. Bùi Quang Chiêu had another target: the poor and uneducated. He had become a believer in Social Darwinism as an explanation for personal success or failure. He used his newspaper to campaign for greater Vietnamese representation on the Cochinchinese Colonial Council but feared that the illiterate peasants who had gone to France as “volunteers” would be rewarded for their war service with the right to vote when they returned. Their sheer numbers would dwarf those of the Vietnamese businessmen and landowners who were eligible to vote on the basis of their education and wealth. The Constitutionalist Party was never a mass organization.Footnote 24

In Tonkin, the elite was still dominated by graduates of the civil service exam system and the press operated under a far stricter regime than in Cochinchina. It was prohibited from discussing political matters (interpreted broadly to include economic affairs as well). Sarraut entrusted a new journal, Southern Wind (Nam Phong), to Phạm Quỳnh (1892–1945), a graduate of the Lycée du Protectorat who had begun working at the EFEO at the age of sixteen years old. Nam Phong was launched in July 1917. Nam Phong originally had three sections: a summary in French, a short section in Chinese, and a longer one in the Romanized script. Gradually, the Chinese section shrank as the quốc ngữ section grew. Unlike the southern press, which openly debated economic and political issues and showed little interest in questions of culture, Nam Phong concentrated on cultural issues. Phạm Quỳnh was a proponent of innovation in literature and especially of fiction as more than a vehicle for entertainment. The journal was also a platform for discussing the question of women in debates that pitted modernity against tradition, patriarchy against youth. While Southerners did journalistic battle with hard-line settlers, Chinese traders, corrupt politicians, and land speculators, Nam Phong was the mouthpiece of the emerging generation of graduates of the Franco-Annamite schools in the North who sought to supplant the classically trained scholars as the new elite. The closest that Nam Phong came to political debates was on the topic of reforming village councils. But these were also couched in the language of cultural reform, villages having become, in the eyes of their modernizing detractors, repositories of outmoded and oppressive customs.Footnote 25 Sarraut made no effort to win over the even more conservative elite of Annam. It was only in 1927 that the newspaper Tiếng Dân (The People’s Voice) was launched by Huỳnh Thúc Kháng, a classical scholar who had taken part in the Reform movement of 1908.

By the time Sarraut left for France in 1923, he had not succeeded in implementing an Indochinese constitution, but he had profoundly altered the terms of political discourse among Vietnamese. In Cochinchina, La Tribune Indigène became the dominant voice of the Vietnamese who espoused Franco-Annamite collaboration though few went as far as Bùi Quang Chiêu in calling for total assimilation. While Bùi Quang Chiêu enthusiastically supported landowners and businessmen, Nguyễn Phan Long, his successor as editor-in-chief of the newspaper, championed the interests of Vietnamese civil servants and other professionals whose numbers had risen in the aftermath of World War I. In the constantly developing south, La Tribune Indigène took for granted the profound changes in the social structures and culture of the region. The opposite was true of Southern Wind which, forced to eschew political and economic matters, concentrated on discussing and even advocating cultural reforms.

Radicals on the Rise

Not every Vietnamese subscribed to Sarraut’s paternalistic view that they were not yet ready for self-rule. New kinds of anticolonial activists were emerging in France and China, as well as in Vietnam. In France, sometime during World War I, the exiled Phan Châu Trinh met up with Phan Vӑn Trường, a lawyer married to a Frenchwoman. In 1917, they were joined by Nguyễn Tất Thành (soon to be better known as Nguyễn Ái Quốc and later as Hồ Chí Minh) who had arrived in Paris from London. Nguyễn Tất Thành had left Vietnam in 1911 at the age of twenty-one (according to his official biography) and worked as a sailor then as a cook in hotels in various countries. Inspired by Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points of January 1918, the three men drafted a document entitled “Revendications du Peuple Annamite” that they signed with the collective name Nguyễn Ái Quốc (Nguyễn the Patriot?). They sent this document, which called for home rule for Vietnam, to all the senior Allied leaders at the Versailles Conference in 1919. None responded. On behalf of the trio, Nguyễn Tất Thành took copies of the document to all the Paris newspapers. Only that of the Socialist Party, L’Humanité, agreed to publish the text of the Revendications. Nguyến Tất Thành was also warmly welcomed into the Socialist Party by Jean Longuet, a grandson of Karl Marx. From then on, the name Nguyễn Ái Quốc was exclusively attached to him.

At the Congress of the French Socialist Party held in Tours in July 1920, Nguyễn Ái Quốc, who had been invited to attend despite not being a French citizen or subject (he was born in Nghệ An, Annam), decided to join the breakaway Communist Party because it seemed more interested in colonial problems than the socialists. He read Lenin’s “Theses on the National and Colonial Question,” in which Lenin connected imperialism to capitalism but also predicted that colonies, as the weak links of capitalism, would end the domination of colonial powers. Nguyễn Ái Quốc was assigned to edit the party’s paper Le Paria (The Pariah) but eventually became disenchanted with what he saw as the party’s indifference toward workers and colonial people. He left some time in 1923 for Moscow, re-emerging in late 1924 in Guangzhou.Footnote 26

Also in 1923, twenty-three-year-old Nguyễn An Ninh, the son and nephew of anticolonial activists, returned to Saigon from France with a law degree and a burning desire to inspire Vietnamese youth to action. He launched a French-language newspaper, La Cloche Fêlée, which took aim at the financial scandals that plagued French Cochinchina in the postwar years. But his main goal was to urge young Vietnamese to achieve their personal independence from family and tradition by working for the independence of the nation. Unlike Southern Wind, which was respectful toward Confucianism, Nguyễn An Ninh portrayed Confucianism as a straitjacket that prevented the Vietnamese from being creative and self-reliant. While his advocacy of change was ardent, his actual program of action was rather vague. But he became an object of adulation among young Vietnamese who passed his newspaper from hand to hand clandestinely. He also gained support not only in Saigon but also in rural areas, belying the limited number of copies his newspaper sold. Of the Saigon-based activists and journalists, he was nearly the only person who sought to mobilize workers.Footnote 27

In 1924, Phạm Hồng Thái, a native of Tonkin, tried to assassinate Governor-General Merlin during his visit to the French concession in Guangzhou. His attempt having failed, Phạm Hồng Thái committed suicide, but his deed resonated among the expatriate population in southern China. Soon thereafter Nguyễn Ái Quốc, newly trained in revolutionary strategy in Moscow, arrived in Guangzhou as a representative of the Comintern. He founded the Vietnam Revolutionary Youth League (Việt Nam Thanh Niên Cách Mạng Đồng Chí Hội) with the aim of training patriotic young men and women in anticolonial activism. At the core of the League was a secret group that was meant to be the nucleus of an eventual communist movement.Footnote 28

In 1926, the Revolutionary Youth League received a sudden influx of recruits thanks to a fortuitous concatenation of events. In 1925, Phan Bội Châu was arrested in China and brought back to Hanoi for trial. The hard-line settlers scheduled his trial for 1926 to embarrass the new governor-general, Alexandre Varenne, who had a reputation as a liberal. Then in March of that year came news of the death of Phan Châu Trinh. He had been suffering ill health for several years but had not dared return to Vietnam until the death in 1925 of Emperor Khải Định, whom he had offended three years earlier by publishing a list of his “crimes.” Phan Châu Trinh never was in good enough health to return to his native Quảng Nam and died in Saigon. On the day his death was announced came news that Nguyễn An Ninh had been arrested for distributing inflammatory anti-French leaflets. The trigger for his action had been the deportation of a Vietnamese activist from Tonkin who had been agitating on behalf of workers.