Introduction: Vietnam as a Cold War Domino

For “the big picture” boys in Washington, Vietnam in the 1950s was primarily a piece on a global game board. President Dwight D. Eisenhower had inherited from his predecessor the grand strategy of containment, which had set the rules of the game. The explicit objective of this strategy was to limit the expansion of Soviet power and influence everywhere in the world, including in the faraway country of Vietnam. By 1954, however, Eisenhower had begun to grasp that Vietnam was no ordinary pawn. Although he famously characterized the Southeast Asian country as a domino – literally a game piece that might topple over and set off a chain reaction involving other nations – the outcome of the Geneva Conference that summer showed that Vietnamese actors were important international players in their own right. In the aftermath of the conference, Eisenhower confronted the problem of a pawn that seemed not to be following the rules.

In November 1954, Eisenhower dispatched his trusted friend and World War II colleague, General J. Lawton Collins, to South Vietnam. Significantly, Collins was given status equivalent to an ambassador, but was officially designated the president’s special representative. Colonel Edward Lansdale, an American who had arrived in Saigon a few months ahead of Collins, quickly concluded that the general’s understanding of Vietnam was lacking:

Collins was from the world of “the big picture,” the top management circles of Washington with their necessarily simplistic view of the complex problems of the world … To apply this picture to what then existed in South Vietnam, where a small group of [American] bureaucrats in Saigon … issued orders mostly to one another in tragic ignorance of what was happening beyond the suburbs, could only lead to faulty judgments.Footnote 1

For Lansdale, Collins’ insistence on viewing Vietnam in geopolitical terms was flawed because it overlooked the importance of mobilizing local support for US policies among Southeast Asian anticommunist nationalists. Lansdale, a former advertising agent who now worked for the CIA, considered himself an expert on how to carry out such mobilizations at the “rice roots” level in countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines.

But the differences between Collins and Lansdale should not be overdrawn. After all, both men had been sent by the Eisenhower administration to try to “save” South Vietnam from communism, and both were equally ignorant of Vietnamese history, politics, and culture. Instead of understanding Collins and Lansdale as polar opposites, they are more usefully understood as exemplars of the two primary themes underpinning Eisenhower’s approach to Vietnam. On the one hand, US officials situated Vietnam explicitly within the grand strategy of containment. On the other, American perceptions of Vietnamese actors – both allies and adversaries – were steeped in racist and patronizing assumptions about Washington’s ability to uplift and transform the country to conform with American objectives. These assumptions reflected the persistent influence of colonial-era ideas about identity and difference in Southeast Asia.

This pair of themes – which were the two sides of the same ideological coin – shaped the Eisenhower administration’s approach to Vietnam as it went through three phases: first collaboration, then unilateralism, and finally self-congratulation and complacency. Working with the French and other allies marked the initial phase. With France’s final withdrawal of its forces in 1956, Washington embarked upon the second phase, structured around the United States’ singular relationship with Ngô Đình Diệm’s Republic of Vietnam. In the final phase, during Eisenhower’s second term, the White House considered Vietnam a problem largely under control and shifted its attention elsewhere.

Throughout Eisenhower’s presidency, Washington’s perception of Vietnam as a piece on the containment gameboard obscured Vietnamese desires to define their nation’s postcolonial identity. US leaders’ insistence on viewing American security through the lens of containment exaggerated the strategic importance of Vietnam, and effectively precluded any consideration of how best to align US interests with Vietnamese political aspirations. When Eisenhower passed leadership to John F. Kennedy in 1961, he had committed the United States to the defense of a state and a president in South Vietnam whose leadership and legitimacy seemed increasingly in doubt.

Containment: The Blinders of Grand Strategy

If there had not been a Cold War, there almost certainly would not have been an American war in Vietnam. One of the most enduring explanations for the US decision to intervene in Vietnam’s internal conflict and to persist for so long and at such great cost is the concept of flawed containment. Put simply, this argument is that the Truman administration’s grand strategy of containment in response to a perceived Soviet political and military threat to Europe was wrongly adapted to Asia following the Chinese communists’ civil war victory in 1949 and the Korean communists’ invasion of South Korea in 1950.Footnote 2

The errors of applying the containment paradigm to Asia are evident in hindsight. There was no Soviet Army poised on the borders of Southeast Asia, and the historical trajectories of the various Asian nations, many subjected to Western imperialism, were significantly different from those of European nations. Moreover, doctrinaire policy formulas are invariably expressions of sweeping generalizations. American leaders have loved doctrines: the Monroe Doctrine, the Open Door in China, Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, and Franklin Roosevelt’s Atlantic Charter. Truman continued this tradition with his Truman Doctrine, declaring in 1947 with thinly veiled reference to the Soviet Union that “it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities and outside pressures.” He added that “we must assist free peoples to work out their own destinies in their own way” – a prescription that was appealing in abstract form but almost never followed by US leaders in practice.Footnote 3

Strategic doctrines can be quite useful to national leaders making decisions under extreme pressures in a chaotic world environment. Such cognitive shorthand is easy to communicate to domestic and international audiences, especially in comparison to subtle and intricate calculations about local agendas and interests. But the formulation of grand strategy and doctrines can also create problems. Indeed, “the ritual of crafting strategy encourages participants to spin a narrative that magnifies the scope of the national interest and exaggerates global threats … Strategizing turns possible threats into all-too-real ones.”Footnote 4

Eisenhower’s famous “falling dominoes” press conference held on April 7, 1954, illustrates how strategic doctrines are formulated and the unintended consequences that can ensue. The president’s immediate objective during this regularly scheduled press event was actually not the presentation of a doctrine, but the transmission of a message: He wanted to signal Vietnam’s strategic importance to Washington at a moment when the military forces of Hồ Chí Minh’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN) were laying siege to the French garrison at Điên Biện Phủ. But in response to a question about “the strategic importance of Indochina to the free world,” Eisenhower invoked what he called the “falling domino principle.” “You have a row of dominoes set up, you knock over the first one, and … the last one … will go over very quickly,” he declared. “So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influence.” With hindsight, it is clear that Eisenhower’s statement was aimed at enlisting France, Britain, and a few Asian and Pacific nations to commit to a US-led plan for “united action” in Indochina. He did not actually believe that the line of containment would hinge on the defense of Điện Biên Phủ. However, to many of those who heard or read the president’s comments, the binary nature of his logic seemed clear and indisputable: Either the United States would prevent the fall of the region to communism, or disaster would ensue. The domino analogy would go on to serve as the touchstone of US policy in Vietnam for the next four presidential administrations.Footnote 5

The focus on falling dominoes obscured the fact that there was actually much more in the president’s answer. Eisenhower first noted Southeast Asia’s “production of materials that the world needs.” After the domino sentences, he returned to raw materials – specifically tin, tungsten, and rubber. The region’s markets were also important to Japan, he explained, because Japan must have this trading area to prevent its turning “toward the communist areas in order to live.”Footnote 6 He declared that “the loss of Indochina, of Burma, of Thailand, of the Peninsula, and Indonesia … [would] not only multiply the disadvantages that you would suffer through loss of … sources of materials, but now you are talking really about millions and millions and millions of people.” His concern for the population was that it would “pass under a dictatorship that is inimical to the free world.”Footnote 7 He called for “a concert of readiness” but cautioned that “no outside country can come in and be really helpful unless it is doing something that the local people want.” “The aspirations of those people must be met,” he reiterated, adding that “I can’t say that the associated states [of Indochina] want independence in the sense that the United States is independent. I do not know what they want.”Footnote 8

In the long run, however, Eisenhower’s interest in what the people of Indochina might want would be eclipsed by the imperatives of containment. In a 1959 speech, the president reaffirmed his famous image: “The loss of South Vietnam would set in motion a crumbling process that could, as it progressed, have grave consequences for us and for freedom.”Footnote 9 As he prepared to leave office in 1961, Eisenhower issued his Farewell Address, which would become famous for its warning against the military–industrial complex. Yet he opened that speech with a stern warning that the United States continued to face “a hostile ideology – global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method.”Footnote 10 For Eisenhower and American strategists, communists anywhere in the world – including in Vietnam – were enemies of the United States. Like it or not, the people and populations who were threatened by those communists had to be protected, lest the dominoes fall.

Legacies of Colonialism and Empire

As Eisenhower had frankly admitted in his 1954 press conference, he and his advisors had scant knowledge of the views and aspirations of the Southeast Asian populations that US policies in the region were intended to support. The president and his advisors did not understand “those people,” and administration leaders often invoked racist and stereotyped images. A State Department planning document from June 1950, for example, described Asians as peasants “steeped in Medieval ignorance, poverty and localism … [and] insensitive to … democratic ideology … or the desirability of preserving Western civilization.”Footnote 11 This notion of Asians as indolent and incompetent pervaded American opinions of Chinese as well as Vietnamese until the Korean War forced US leaders to acknowledge at least the military prowess of Chinese communist soldiers and commanders. But that experience did not translate into appreciation of the Vietnamese abilities. Lưu Đoàn Huynh, an intelligence analyst in Hanoi’s ministry of foreign affairs, later observed that, unlike Washington’s view of China as a force to be respected, Vietnam was always seen as small, weak, and dependent upon others.Footnote 12

The Eisenhower administration’s uncertainty over how to proceed in Vietnam became apparent in the aftermath of the Geneva Conference. At a National Security Council (NSC) meeting in August 1954, US officials struggled to craft new strategic guidance for US policy. Parts of it fell readily into place: the United States would create a regional defensive alliance (the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, or SEATO) and provide economic and military aid through the French to the State of Vietnam (SVN), the Saigon-based anticommunist entity headed by the former emperor, Bảo Đại. When the council reached the paragraph entitled “Action in the Event of Local Subversion,” however, the discussion abruptly halted. This section sought to articulate policy in the event of communist subversion that was not “external armed attack.” When the president declared that he was “frankly puzzled” on this issue, the council tabled discussion until the next meeting.Footnote 13

A few days later, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles presented several options for the unfinished paragraph. The president impatiently announced that he was not interested in “strictly local” subversion unless it was motivated by Chinese communists. Vice President Richard Nixon offered that the Indochinese communist leader Hồ Chí Minh might actually be a Soviet agent. Eisenhower ended the discussion asserting that “of course if the Soviet Union were the motivating source of subversion, it would mean general war.”Footnote 14 No one seems to have considered the possibility that the Vietnamese, who had defeated the French at Điện Biên Phủ and negotiated a compromise peace at Geneva, might be acting on their own initiative.

Some of Eisenhower’s biographers credit the president with acting cautiously in Indochina in 1954. But this alleged caution is belied by his confidential remarks, which reveal a determination not to countenance Soviet communist success anywhere.Footnote 15 In 1953 and 1954, the president secretly authorized CIA-backed coups against elected governments in Iran and Guatemala, believing those governments were Soviet proxies.Footnote 16 Eisenhower and his advisors were not oblivious to the depth of anticolonial feeling in the Global South and they routinely stated their willingness to accommodate nationalist sensibilities in Indochina. Yet they also frequently displayed a profound inability to reconcile global containment with the indigenous cultural and historical identity of the Vietnamese.

Although US leaders denied having any colonial ambitions in Indochina, the policies they fashioned routinely undermined Vietnamese national sovereignty. Indeed, portraying the communist threat in Vietnam as an absolute danger to the United States required Washington to fashion a Vietnamese solution to such a dire threat. Like the French before them, the Americans had their own views about the future of Vietnam, and they were prepared to employ unilateral and even coercive tactics to achieve those views. The United States had its own civilizing mission, and after the French departure, Washington worked to convince the South Vietnamese to comply with America’s objectives. Although those efforts were often stymied – especially after Ngô Đình Diệm came to power in Saigon – US officials, diplomats, aid experts, and military advisors still persisted in their efforts to fashion South Vietnamese state and society according to American prescriptions.Footnote 17

Collaboration, 1953–5

The first phase of Eisenhower’s stewardship of US interests in Southeast Asia was a collaborative approach that began with Washington’s decision to provide France with material support in its war against Hồ’s DRVN. Eisenhower was uneasy with France’s evident colonial motives, but the Cold War seemed to require a united front with European allies against the Soviet Union. In 1954, France’s commitment to that venture was abruptly thrown into question by the compromise peace agreement reached with the DRVN at Geneva, prompting US officials to promote SEATO as an alternative arrangement.

Although Eisenhower came to office dedicated to global containment, he was also committed to reducing US government spending. As part of this commitment, he introduced the New Look strategy that promised economical ways to protect American security. In public statements, Secretary of State Dulles emphasized the reliance on the United States on nuclear deterrence (or what became known as “massive retaliation”) as a way to counter Soviet threats without stationing US conventional ground forces overseas. However, the New Look also included greater reliance on military alliances, negotiation with adversaries, and covert operations.Footnote 18 Not surprisingly, Eisenhower and Dulles applied elements of the New Look in Indochina. But such cost-cutting concerns, combined with the heavy focus on the US–Soviet confrontation, left little room for attention to Vietnamese nationalism or local Indochinese agendas.

Initially, the United States connected its collaboration with France in Indochina to the building of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in Europe. Although many US leaders were skeptical about supporting a French colonial war in Indochina, Dulles told US Senators that “the divided spirit” of the world and containment objectives in Europe required Washington to continue to tolerate colonialism in Indochina a little longer. Dulles also sought French acceptance of a rearmed West Germany as part of an American-backed plan for NATO called the European Defence Community (EDC). To keep the French fighting for containment in Asia and cooperating in Europe, the Eisenhower administration expanded US aid to almost 80 percent of French military expenditures in Indochina by January 1954.Footnote 19

In the early weeks of 1954, as the decisive events at Điện Biên Phủ began to unfold and the French public turned increasingly against the Indochina War, Eisenhower and his aides weighed their options. The president remarked that “while no one was more anxious … to keep our men out of these jungles, we could nevertheless not forget our vital interest in Indochina.”Footnote 20 The decision for the moment was to stay with France, and that option included reluctant agreement to attend the proposed conference at Geneva to seek a negotiated end to the fighting. Meanwhile, the Pentagon examined possible US air and ground operations in support of the French, and the CIA explored clandestine assistance to Bảo Đại’s SVN, including dispatching Lansdale to Saigon.Footnote 21

By March 20, the French position at Điện Biên Phủ had become desperate. General Paul Ely, the French chief of staff, traveled to Washington for consultations. Eisenhower’s advisors considered a tactical US airstrike, an option favored by Vice President Nixon. There is little evidence that the president seriously considered use of nuclear weapons, but massive conventional bombing was a genuine possibility. Eisenhower never ruled out air bombardment, but the president ultimately decided against direct US military intervention, in contrast to later chief executives who deployed US troops and planes to Vietnam. On the weekend of April 3–4, Dulles met first with congressional leaders – Senate Minority Leader Lyndon Johnson among them – who expressed opposition to unilateral American intervention. In response, Eisenhower decided that US military intervention was possible as long as it was multinational, included France, and predicated on eventual independence for Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. In a personal letter to British prime minister Winston Churchill, Eisenhower joined Dulles in pursuing a multilateral demarche. This effort was quietly underway when Eisenhower employed the domino analogy at his April 7 press conference. By the time the Geneva Conference opened on April 26, Dulles had already finished meetings in London and Paris and reported to Washington that there was no time left to arrange the political understanding necessary for joint action. The French garrison at Điện Biên Phủ fell on May 7, ceasefire negotiations plodded along at Geneva, and Eisenhower’s team continued to seek ways to internationalize security arrangements for Southeast Asia.Footnote 22

At Geneva, the Eisenhower administration took a passive role to avoid any responsibility for a settlement that validated communist success in Vietnam. Ironically in view of later US policy, Eisenhower expressed firm opposition in late April to military intervention in Vietnam because “in the eyes of many Asian people [the United States would] merely replace French colonialism with American colonialism.”Footnote 23 The president’s focus remained on the Soviet Union and China and the risk of general war. He disdained “brushfire wars” that “frittered away our resources in local engagements.”Footnote 24 Yet he envisioned the United States taking leadership of an allied defense of Southeast Asia against communist expansion.

American leaders considered the outcome at Geneva a tactical defeat and concluded that two elements of the New Look – negotiation and the threat of bombardment – had proven ineffective. Washington publicly acknowledged but did not formally endorse the Geneva ceasefire terms that included the temporary partition of Vietnam at the 17th parallel. Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) Allen Dulles, using Lansdale as point man in Vietnam, deployed New Look-style covert psychological measures aimed at weakening the DRVN in North Vietnam and strengthening the new administration of Prime Minister Ngô Đình Diệm in the South. Meanwhile, the DCI’s brother, the secretary of state, took the lead on making the 17th parallel the new containment line in Asia. Discussions within the NSC briefly examined the idea of doing basically nothing in Vietnam to avoid becoming trapped in defense of a rump state in the South, but the president himself ended the talk declaring that “some time we must face up to it: we can’t go on losing areas of the free world forever.”Footnote 25

On September 8, 1954, staying with a collaborative and alliance-focused approach, Secretary Dulles presided over the signing in Manila of the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty. Also known as the Manila Pact, Dulles described it as a “no trespassing” sign warning Moscow and Beijing to keep hands off the region. It was intended as a psychological deterrent and as a mechanism for making joint military action palatable to Congress – something that had been unavailable to Washington during the siege of Điện Biên Phủ. The authors of this agreement purposefully modeled the acronym SEATO on NATO. But the similarity of the two alliances ended there. Unlike the NATO treaty, the Manila Pact did not require an automatic response in the event that one member came under attack. The Geneva ceasefire prohibited South Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from joining any military alliances, but an addendum designated them as being within the treaty area and allowed SEATO members (the United States, Britain, France, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand, and Pakistan) to take action on their behalf with their consent. Despite efforts to recruit India, Burma, and Indonesia, those governments declined to join in order to preserve their political neutrality.

Despite its less-than-auspicious launch, the creation of SEATO had lasting implications. Johnson’s 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution cited the SEATO treaty as a US “obligation” in defense of freedom in the region.Footnote 26 The pact was a step toward converting the 17th parallel into another 38th parallel, the line separating North and South Korea – a new segment of the Asian containment line. SEATO also forged new links in the so-called ring of alliances envisioned by the New Look with acronyms such as CENTO and ANZUS, as well as bilateral defense arrangements with Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea.Footnote 27

SEATO was a line of credit upon which South Vietnam might draw some future allied assistance. By itself, however, the pact could not breathe life into the fragile SVN government in Saigon. In June, with the Geneva talks still ongoing, Bảo Đại made Diệm SVN prime minister, anticipating that this anticommunist nationalist known to some prominent Americans would attract US backing.Footnote 28 But Washington’s interest in Diệm threatened the collaborative approach with Paris because French officials knew Diệm to be an anti-French nationalist.

Lansdale arrived in Saigon as Allen Dulles’s “own representative” just in time to witness what he described as Diệm’s inauspicious arrival in the city.Footnote 29 Lansdale invented the Saigon Military Mission (SMM), a team tasked with manipulating information and misinformation, conducting espionage, and covertly advising Diệm. Lansdale’s self-described purpose was “to help the Vietnamese help themselves.”Footnote 30 Many years later Lansdale acknowledged that “I was backed by the CIA” and “I had CIA people.”Footnote 31 The degree of credit the SMM deserves for Diệm’s survival in those early days is difficult to measure, but the efforts of the SMM, other American agents, and some able Vietnamese officials, such as Trần Vӑn Đỗ who had represented the SVN at Geneva, helped resettle Vietnamese Catholics from the North to the South to provide Diệm a small public base of fellow Catholics in the predominately Buddhist country. Lansdale also claimed to have helped Diệm avoid a seizure of power by Nguyễn Vӑn Hinh, the head of the French-created Vietnamese National Army.Footnote 32 Despite these accomplishments, Eisenhower viewed Diệm as a weak figure around whom to fashion a Cold War battlefront. The president decided to send General J. Lawton Collins with broad authority to try to fashion joint US–French assistance to Diệm but also to evaluate honestly Diệm’s survivability and, if necessary, to identify leaders who might be more effective allies.

The Collins Mission was part of a White House “crash program” to invigorate Diệm’s government before, in the president’s words, it “went down the drain.” Washington wanted direct US military aid and training for a South Vietnamese army without going through the French Expeditionary Corps, which was the occupying force designated in the Geneva Accords. Eisenhower thought it was time to “lay down the law to the French.” “We have to cajole the French in regard to the European area, but we certainly didn’t have to in Indochina,” the president instructed the NSC.Footnote 33

Working together, Collins and Ely improved military training and bureaucratic processes in the South, but the fate of the SVN remained uncertain. French officials believed Diệm was an unreliable leader, but Lansdale insisted that Diệm had the potential to be “highly popular.”Footnote 34 Tasked to make an assessment, Collins voiced doubts about Diệm’s leadership almost as soon as he arrived in November 1954, and finally on March 31, 1955, he cabled Washington that Diệm was “operating practically one-man government” and could not last much longer.Footnote 35 He advised that Trần Vӑn Đỗ or Phan Huy Quát, a veteran of several Bảo Đại cabinets, had the experience and political connections to best leverage American support for the South.Footnote 36

An eruption of open warfare in the streets of Saigon and its suburb Chơ lớn – what became known as the Sect Crisis – prompted this urgent message. Diệm had many domestic opponents, including the Cao Đài and Hòa Hảo religious sects outside Saigon and the Bình Xuyên crime syndicate in the city. Whether Diệm’s forces or the Bình Xuyên gangsters fired first, public order had collapsed. French General Ely blamed Diệm for losing control, and Lansdale believed the Bình Xuyên provoked the clash. Washington instructed Collins to try to gain time because Eisenhower and Dulles were not prepared simply to cut off the prime minister. Notably, Diệm had gained the sympathy of significant members of Congress, including senators Mike Mansfield, Hubert Humphrey, and John Kennedy. Likely because of Lansdale’s favorable reports about Diệm through CIA channels, Secretary Dulles encouraged Collins to stick with Diệm. On April 7, however, the general finally determined that “Diệm does not have the capacity to achieve the necessary purpose and action from his people … essential to prevent this country from falling under communist control.” He deemed Diệm to be a patriot but concluded that Diệm was not “the indispensable man.”Footnote 37

With Eisenhower’s permission, Dulles summoned Collins to Washington to try to resolve the differences over Diệm. The president respected both men and left the prime minister’s fate in their hands – until Diệm decided to wrest it back. In Washington, Collins stood his ground and appeared to have prevailed, when suddenly word arrived that Diệm’s forces had engaged the Bình Xuyên gang in renewed fighting on April 27. Lansdale flashed the news to the Dulles brothers and reiterated his argument for continued support of Diệm. Collins later recalled: “I [was] getting instructions from the president of the United States, and this guy Lansdale, who had no authority so far as I was concerned, [was] getting instructions from the CIA. It was a mistake.”Footnote 38 As Collins hurried back to his post in Saigon, Secretary Dulles with the concurrence of the State Department’s Asian specialists decided the violent outbreak was an inopportune time to tamper with the Saigon regime’s leadership. Dulles made the fateful decision to stick with Diệm and extend him America’s “wholehearted backing.”Footnote 39

The Eisenhower administration tried to convince France to accept the course it had chosen with Diệm. After several tense sessions in early May 1955, Foreign Minister Edgar Faure yielded to Dulles’ insistence. French forces agreed to depart Vietnam and leave the fate of the southern portion of the country to Diệm and his American backers. The FEC was formally dissolved in April 1956, and Paris with Washington’s blessing put its military efforts into the worsening anticolonial war in Algeria, seeking to avoid “another Indochina.”Footnote 40 SEATO provided a semblance of collaborative sanction for US efforts to sustain South Vietnam, but the weakness of the pact and the departure of the French meant that the security and development of the South would be a unilateral US program. The Eisenhower administration had entered a new and perilous policy phase.

Unilateralism, 1956–7

At least for the moment, Washington had cast its lot in Vietnam with Diệm. Although Diệm strove to refute communist allegations that his government was a mere American puppet, he ruefully admitted that many Vietnamese had adopted the disparaging term Mỹ–Diệm (America–Diệm) to refer to the Saigon regime. As Diệm moved to consolidate power, Eisenhower and Dulles left it to others to shape the large flows of assistance now programmed for South Vietnam. A heart attack in 1955 slowed Eisenhower for a while, Dulles received a diagnosis of abdominal cancer the next year, and crises emerged elsewhere in the world. American diplomats, military officers, and various development experts set to work on the effort to build an effective state in South Vietnam around Diệm and his family.Footnote 41

This experiment in state-building faced enormous obstacles. The State of Vietnam had a small army of 150,000 with an inexperienced officer corps. Its civil bureaucracy consisted of fonctionnaires trained by the French to take orders, not make decisions. The South had less heavy industry than North Vietnam, and its largely rural population of farmers and fishermen were impoverished from decades of exploitation by Vietnamese and French landlords and colonial taxes. Even before tackling these deficiencies, however, the Saigon government needed to create its own popular legitimacy. Diệm was not a prince of royal lineage, as was Norodom Sihanouk, the head of state of neighboring Cambodia, nor was he a patriotic hero of the war against France, as was Hồ Chí Minh. Any claim to popular authority would have to come from some form of democratic endorsement, presumably an election.Footnote 42

The final declaration of the Geneva Conference had called nationwide elections in 1956 to determine Vietnam’s political future. But most participants recognized that the chances of actually conducting elections were “definitely poor.”Footnote 43 The Geneva documents outlined no voting procedures, nor did they specify which offices or legislative bodies were to be filled by the balloting. One Canadian officer on the staff of the International Supervisory Commission (ISC) later recalled that Hanoi had the atmosphere of a “police state.”Footnote 44 That same officer described the ISC – created by the Geneva conferees to supervise the ceasefire and possibly an election – as “very inactive,”Footnote 45 and scholars have described it as “procedurally defective,”Footnote 46 especially on political matters. The French forces that could have helped implement an election in the South had departed by the spring of 1956. Moreover, neither Bảo Đại’s representatives nor those of the United States or even those of the DRVN had formally endorsed the final declaration at Geneva, including the national elections provision.Footnote 47

The State Department officer in charge of Philippine and Southeast Asian affairs, Kenneth Young, was keenly aware that the legitimacy of Bảo Đại’s State of Vietnam was fragile. Diệm owed his appointment to an ex-emperor tainted by his self-serving associations over the years with the Japanese, the French, and the Bình Xuyên. In the wake of the Sect Crisis, Young feared that elections in the South would invite anarchy.

While Washington officials exhibited little trust in democracy in Vietnam, Diệm acted unilaterally. In October 1955, he staged a referendum that deposed Bảo Đại. He then declared himself president of the newly proclaimed Republic of Vietnam (RVN). A few months later, he and his brothers ran an election that produced a constituent assembly, heavily stacked in their favor, to draft a constitution. These were not exercises in pluralistic democracy – evidence of ballot manipulation was widespread – but they provided a means for the regime to advance its own claims to sovereignty and legitimacy.Footnote 48

By the time the July 1956 deadline for the Geneva-mandated elections arrived, the United States had strengthened South Vietnam through economic aid and a vague warning to Hanoi in the form of SEATO. Moreover, the major powers appeared content to see partition continue, rather than risk a crisis or hostilities in Indochina. Britain and France were more concerned with Europe than Asia. The Soviet Union was developing its post–Stalin “peaceful coexistence” line toward the West and even suggested it might accept the admission of both Vietnams to the United Nations. Beijing seemed similarly content with a divided Vietnam. In the summer of 1955, the Soviet Union and PRC both declined to press the election issue in separate meetings with US officials in Geneva and Warsaw.Footnote 49

Largely ignorant of Vietnamese history and culture, American leaders understood politics and strategy well enough to recognize the advantages of a divided Vietnam and handled the issue of the 1956 elections with finesse. Neither Hồ Chí Minh’s DRVN nor Diệm’s RVN could claim to represent all Vietnamese, and both faced the task of building a political community.Footnote 50 Although US officials did not want the elections to take place, they nevertheless pressed Diệm to open consultations with Hanoi so as to appear supportive of the Geneva stipulation that the elections would serve as a “free expression of the national will.”Footnote 51 But Diệm had no interest in parleying with Hanoi. In July 1955 he declared that no consultations could take place unless and until the DRVN was willing to “renounce terrorism and totalitarian methods.” By the spring of 1956, despite complaints made by Hanoi and its allies, it was clear that the elections would not take place. Washington thus reaped the benefits of Diệm’s intransigence while still asserting their support in principle for free elections as a means of achieving national unity.Footnote 52

In the long run, the nonelections of 1956 greatly contributed to an increased US presence in South Vietnam. Although Hanoi did not immediately abandon its hopes for peaceful reunification, it would eventually turn to armed insurgency to achieve its goals.Footnote 53 The muted international response to the nonelections also showed that Britain and France would henceforth defer to Washington on policy in Indochina. At the same time, South Vietnam had been transformed in the eyes of US leaders. During 1954–5 they viewed South Vietnam as a potential major setback for American containment strategy, but two years later they congratulated themselves for having “saved” the country from communism. This narrative of rescue and salvation would later help pave the way for a massive new unilateral American military intervention in the 1960s. For the moment, however, Washington believed it had successfully bought more time to achieve its objective of a strong, anticommunist state in South Vietnam.

Self-Satisfaction and Complacency, 1957–61

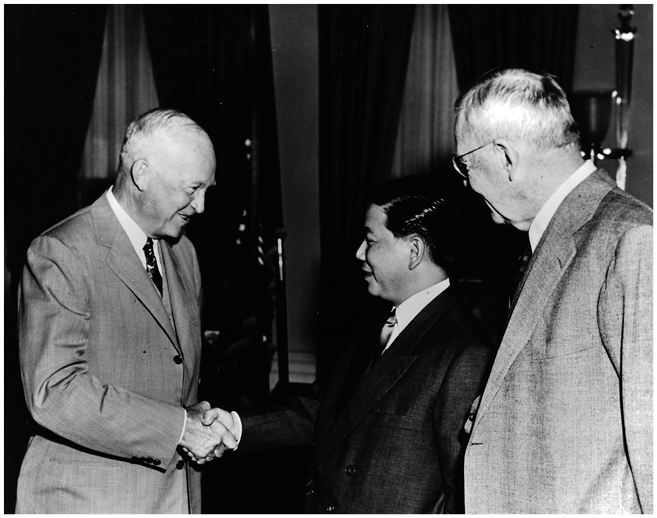

The Eisenhower administration chose to declare Diệm’s political survival a great success, despite the RVN’s considerable weaknesses. On May 7, 1957, Eisenhower endured the heat of Washington National Airport’s parking apron to welcome Diệm for a highly publicized state visit (Figure 13.1). The public pageantry included an address to Congress and was part of an outreach to Third World leaders in the wake of the Suez Crisis the previous fall. Diệm was only a circumstantial beneficiary of this attention, but the American public rhetoric was effusive. Eisenhower accepted his aides’ now-optimistic assessment of Diệm and joined the chorus that hailed the “tough miracle man” and the “savior” of South Vietnam.Footnote 54 In private meetings, budget-conscious Republicans rebuffed Diệm’s appeals for increased aid, but the public show reconfirmed the strategic importance of Vietnam to the United States.Footnote 55

Figure 13.1 Dwight D. Eisenhower shaking hands with Ngô Đình Diệm (1957).

This celebrated success, however, was tenuous. The Saigon regime’s narrow political base and lack of economic development left the RVN increasingly vulnerable to instability, including armed insurrection. Leland Barrows, who directed the US assistance program in Vietnam, recalled that “Diem had no desire to reduce his dependency on us. Aid creates dependence no matter how good it is.”Footnote 56 Under American tutelage, the RVN remained dependent on the United States and its legitimacy remained very much in question.

American civil and military officers in Saigon and the Diệm government waged a three-way tussle over how to direct US aid. As the DRVN-backed insurgency grew in the South after 1959, Diệm and his influential brother Ngô Đình Nhu moved to protect their authority through suppression of anticommunist critics within South Vietnam. They also demanded US financing for a larger army. Pentagon officials argued that meeting the RVN’s security needs had to precede political reforms, and US diplomats countered that military assistance should be withheld as leverage to prompt Diệm and Nhu to implement reforms.Footnote 57 US Ambassador Elbridge Durbrow in Saigon observed, however, that the “somewhat authoritarian government of President Diem is compatible with our interest in Vietnam” primarily because of “its strongly anti-communist external stance.” Lest anyone in Washington get the wrong idea, Durbrow warned that “democracy in the Western sense of the term may never come to exist in Viet-Nam.”Footnote 58

As Sputnik, Cuba, Taiwan, and other Cold War issues captured Eisenhower’s time, the US country team in Saigon wrestled with the task of state-building. The president remained focused on Soviet intentions in the world, and, as his second term ended, Moscow was supplying communist forces in Laos against an American-recognized government. He briefed John Kennedy in January 1961 immediately before the new president’s inauguration that Laos was the most serious American problem in Southeast Asia. Eisenhower made no mention of Vietnam, where the situation still seemed manageable.Footnote 59

The debate among Americans revealed that US state-building had evolved in ways reminiscent of the French colonial regime. Although Washington had no desire to colonize the RVN and claimed to abhor imperialism, the Washington–Saigon axis was not one of equals. To protect the global security of the United States, the administration had defined South Vietnam as a domino – a piece in the containment puzzle – that like Iran and Guatemala must not be allowed to fall to communism. In backing Diệm, the Eisenhower administration showed how far it was willing to go for the sake of containment in Southeast Asia. The Kennedy administration would go even farther – both in its support for Diệm and in its eventual withdrawal of that support. The logic of containment dictated that South Vietnam had to be defended, even if that came at the cost of compromising the legitimacy and sovereignty of the Saigon government.Footnote 60

Conclusion: Commitment without Creativity

Eisenhower’s management of Vietnam as a national security issue began as a collaboration with the French and then morphed into a unilateral intervention before ending with self-congratulations. As the French war in Indochina raged, the White House focused attention on Vietnam because France was a valuable Cold War ally and communism seemed to be on the rise in Asia. By the time Eisenhower left office, Vietnam remained strategically important but had a lower priority among world trouble spots. Washington believed for a time that the alliance with Diệm protected American interests, but eventually US leaders lost confidence in the abilities of Saigon’s leaders.

In October 1960, on the fifth anniversary of Diệm’s establishment of the RVN, Eisenhower praised “its successful struggle to become an independent Republic.”Footnote 61 Once France had acceded to American designs for Vietnam, the administration assumed that Saigon was free from the colonial stigma. Washington underestimated the dangers of aligning US interests with those of Diệm and his family. The United States did not exploit Vietnam’s economy for profit; indeed, it spent vast sums there. But the massive flows of aid and the showy displays of diplomatic support failed to stem the decline in Diệm’s popularity and legitimacy, especially after 1960. These would prove costly failures – more costly than Eisenhower or his advisors ever could have imagined, especially during the halcyon days of the late 1950s, when South Vietnam seemed to be an irresistible story of the United States’ Cold War success.