It has become an article of faith among neo-orthodox observers who want to picture the Vietnam War as a United States victory that the guerrilla enemy was defeated. In some formulations this goes so far as to claim the insurgents were vanquished on the way to the defeat of the North Vietnamese main forces by American air power. Let us postpone that overarching question while laying the groundwork to consider it by looking at “pacification,” which in Vietnam came to mean organized efforts to root out the adversary’s apparatus across the broad extent of South Vietnam. The story is both more complex and less clear than neo-orthodox proponents would have it; and the record is also more nuanced than the views of those who favor the insurgents, the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF).

The American war in Vietnam is often described as a struggle for the “hearts and minds” of the Vietnamese people. This chapter will examine United States efforts to stimulate Saigon’s government in this enterprise. It will also look at “nation-building,” a complementary set of foreign assistance and aid programs that Washington intended to create a robust Republic of Vietnam that could offer an attractive alternative to the NLF. The approach will be partly thematic and partly chronological, opening with the definitional problem and a general description of the conflict terrain, then turning to a narrative showing the progression of how various Saigon regimes and American actors gradually shifted to a countrywide focus on a “war in the villages.”

What Were the Americans Up To?

The first problem is one of definition. Despite probably millions of words, even pages, devoted to this topic, in public speeches, secret documents, and oral briefings, during the war there was no generally accepted definition of “pacification.” The September 1974 edition of the Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, for example, contains no entry on this key principle of the war.Footnote 1 A standard source such as Spencer C. Tucker’s The Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War gives this meaning: the “array of programs that sought to bring security, economic, development, and local government to rural South Vietnam.”Footnote 2 That text fails to define pacification as a process, but merely pictures it as a collection of programmatic elements. Similarly, the history crafted by Richard A. Hunt, a foremost expert on the subject, reports that “Pacification encompassed both military efforts to provide security and programs of economic and social reform and required both the US Army and a number of US civilian agencies to support the South Vietnamese.”Footnote 3 In essence pacification remained in the eye of the practitioner – and the pulling and hauling among different actors with differing interests and perceptions of the task bedeviled this effort throughout the period.

Richard Hunt’s description has the virtue of pointing to the Saigon government. The United States may have been the main actor in pacification but US actions were in support of the South Vietnamese, who held the real responsibility. Never could the United States do whatever it wanted, and from beginning to end the South Vietnamese commitment remained problematic. Former CIA officer Thomas Ahern, author of the agency’s official history of pacification in the war, quotes Saigon’s deputy defense minister’s telling comment to the CIA’s chief of operations for South Vietnam. This was late 1954, and the two were in Vĩnh Long city, a Mekong provincial capital, for the baptism of a child of Ngô Đình Nhu. The CIA man asked how far out from Saigon the government’s control extended. “As long as we’re here it’s this far, but when we go back to Saigon it goes back with us.”Footnote 4

On the American side, the administration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower took a conventional view of developing the South Vietnamese military, but did provide economic aid aimed at subsidizing land reform, and other elements that would become elements of pacification. President John F. Kennedy may not have had a comprehensive definition of the phenomenon, but his promulgation of a doctrine of “counterinsurgency” offered a readymade framework with which to understand the struggle. It was counterinsurgency, rather than pacification, that would frame early United States efforts. This subsumed “civic action” – a limited form of relating to people – but was largely built around security tactics. Counterinsurgency would be applied as the United States induced Saigon to fight the NLF guerrillas on their own terms. Later, President Lyndon B. Johnson, champion of the Great Society in the United States, devoted major attention to nonmilitary aspects of the conflict, and this “other war” became the foundation for the comprehensive pacification attempted at the midpoint of the Vietnam War. At its highest level the development inherent to the other war would be called “nation-building.” In the villages at the micro level the sides contested the loyalties of the South Vietnamese people.

This other war was a fundamentally political conflict in which pacification, or the push to uproot the adversary’s networks in the villages, became a primary warfighting mechanism. Nation-building sought to create and improve South Vietnamese institutions and productive means sufficiently to give the populace a stake in supporting the Saigon government. One important scholar of the process has labeled it “inventing Vietnam.”Footnote 5 Counterinsurgency continued to be pursued, identifying specialized forces and means, acting alongside the social and political aspects of building popular support. While all these elements had formed part of the South Vietnamese struggle from the beginning, their application varied in depth and over time. The sides thus began to implement strategies and tactics that were not fully understood, under leaders and commanders who varied in their approaches to the problem.

The Era of Special Warfare

The early months following the 1954 Geneva Agreements, when the government of Ngô Đình Diệm was busy establishing itself, pushing out from Saigon, in the way that Ngô Đình Nhu did for his son’s baptism, were a major piece of the action for pacification. The first big pushes were into Cà Mau province, at the southern tip of Vietnam, and Bình Định on the central coast. Already, American advisors were promoting a “people first” approach while French officers – still in Vietnam at the time – emphasized security. By 1956 the French were forced out. Consolidating his power, Diệm relied on military force. South Vietnamese civilian agencies did not seem to understand that people had any role at all, while US aid focused on more conventional assistance.Footnote 6

President Diệm’s approach successfully wore down the South Vietnamese political–religious sects, and the former Việt Minh cadres who had stayed in the South after Geneva were shrunk to a small, hard kernel. By the end of 1957 an estimated 65,000 people had been arrested and several hundred killed. A government decree imposed the death penalty for membership in the Communist Party. Executions later averaged 150 a month.Footnote 7

Cadres begged Hanoi authorities for permission to take up arms, permission that only came in 1959. By then the pent-up energy among this cadre was enormous, and their upsurge exploded across South Vietnam. The Southern resistance built considerable strength in the villages by creating “parallel hierarchies” of interlocking movements – from farmers’ or women’s groups and health cooperatives to quasi-governmental entities that performed functions identical to Saigon government organs. Thus it enlisted people in ways that compromised them insofar as Saigon was concerned.

At the end of 1960 the Southern resistance gave itself a fresh, united-front cloak by creation of the National Liberation Front (NLF). The NLF supplemented its organizational efforts with forceful acts against official government representatives, in effect closing Saigon officials out of many areas of South Vietnam. The relative strength of the government versus NLF hierarchies defined progress.

Early experts who believed in people-first approaches held out for supplies of potable water, blankets, mosquito nets, and the like. This became known as “civic action.” Major initiatives established medical clinics or centered on land reform. Several ordinances, culminating in No. 57 of October 1956, sought to provide “land to the tiller,” going one better over the Việt Minh, who had enjoyed good success during the French war with a program of this type (in contrast to the North’s disastrous mid-1950s attempt at collectivization). In the early 1960s Saigon claims for land expropriated from rich landowners ranged as high as a half-million hectares. Later study showed the households benefiting from the program to be a tiny fraction of the millions of peasants who lived on the land.Footnote 8

Another Diệm program, called “land development,” even better illustrated the direction Saigon had taken. Here the proposition was to homestead wilderness, or underutilized land, and build a new class of Saigon loyalists by giving them title. Washington subsidized land development to the tune of $10 million. Most of the land “developed” was in the Central Highlands or the western Mekong Delta. The “plateaux montagnards du sud,” the Central Highlands, were largely tribal lands belonging to a range of primitive societies that cohabited South Vietnam with the Vietnamese. In French colonial times the Highlands, and the “Montagnard” peoples who lived there, had been administered separately from lowland Vietnamese. This minimized contact between Montagnards and lowlanders – just as well since Vietnamese frequently viewed Montagnards in racialist terms. The western Mekong lands were those of the sects Diệm had overpowered in 1955. In fact, in both arenas development had a political content. Diemist land “development” effectively annexed Montagnard or sect land to distribute to Vietnamese homesteaders – often members of the diaspora migrating from North Vietnam. Put differently, the most significant land redistribution in South Vietnam amounted to an act of imperialism – Vietnamese seizing land from tribes or religious minorities to hand to other, favored, Vietnamese. Ngô Đình Diệm visited the Highlands only once, when he went to Buôn Mê Thuột in February 1957, and it is not surprising that an attempt was made to assassinate him there.Footnote 9

President Diệm’s policies illustrated the dichotomy that persisted between United States and South Vietnamese pacification leaders throughout the conflict. Americans were torn between different visions of technique, and they may not have had a clear definition of the process or their goal, but the Saigon hierarchy had different purposes and objectives altogether. This dichotomy played out in pacification efforts throughout the Vietnam War.

Despite President Diệm’s strenuous efforts, the resistance that opposed him scored gains quite quickly once it took to the field. Members of the Southern resistance openly say that the Diemists whittled them down practically to the nub, a fact that only underlines the degree of their success. By April 1959 – a month before Hanoi even approved the creation of the Trường Sơn Strategic Supply Route (known to Americans as the Hồ Chí Minh Trail) – the CIA was already reporting the resistance had achieved nearly complete control of whole villages and districts in Cà Mau province, the part of South Vietnam furthest away from Hanoi’s control. This was more than eighteen months before the rebels created their NLF. Here they perfected the techniques of parallel hierarchies and political struggle (đấu tranh) they would use throughout.

Pacification as conventionally pictured started right then. Diệm approved a program for population relocation into so-called agrovilles, theoretically separating peasants from the Liberation Front cadres seeking their support. The arrangement also permitted Saigon’s security forces to keep an eye on suspect villagers. Proponents claimed the “agricultural villages” would enable the Saigon government to furnish goods and services which peasants had never had access to. Peasants disliked being uprooted from their land, and living in the agroville but farming as before they had even further to travel to and from work each day. The promised goods and services proved thin, and late. Worse, Saigon officials sought to finance the agrovilles internally – with peasants contributing labor to build communal facilities and forced to buy their new plots of land and even to dismantle their own village homes to build the new houses. The failure was such that, within six months of its March 1960 inception, the plans were scaled back by 75 percent. Fewer than 50,000 people – a tenth of the original anticipated number – finally lived in agrovilles, which were effectively moribund by early 1962.Footnote 10

Diệm and his officials were largely responsible for the agroville formula. After that, counterinsurgency experts followed with all kinds of possibilities. Many were impressed with the British campaign in Malaya, where an ethnic Chinese insurgency movement was being progressively defeated, and “population relocation” – the strategy of moving the people off the land, now given a formal name – was seen to have played a major role. Robert Thompson, a veteran of the Malaya campaign, arrived in Saigon in 1961 as chief of a British Advisory Office, and he urged on Diệm a new variant of population relocation. In Vietnam, Saigon leaders and Americans would call it the “Strategic Hamlet Program.” North Vietnamese observers coined the name “special warfare.” Thompson with Diệm, and CIA station chief William Colby with Ngô Đình Nhu, Diệm’s brother and éminence grise, proposed new population defense schemes which merged into the Strategic Hamlet Program and got underway early in 1962. By then John Kennedy, the apostle of counterinsurgency, was sitting in the White House, and the United States was supporting the Saigon government’s program.

Ngô Đình Nhu chaired the committee of Saigon officials who led the program, and Nhu spoke of social transformation through relocation. Colby had similar ideas, and US aid supported some modest improvements in the standard of living for the peasantry. But forcible relocation, corruption, poor security, and failure to engage the populace to explain Saigon’s intentions collectively revealed the inadequacy of implementation. North Vietnamese adversaries worried about the roughly 12,000 strategic hamlets that were created, but many of them were really no more than bamboo barriers surrounding peasant shacks, without even radios to summon help. The hamlet defenses required insurgents to mass for attacks, affording the South Vietnamese army opportunities for countermoves, but that was a limited gain, especially if Saigon troops, due to poor communications, never learned of the guerrilla threats. The showcase for strategic hamlets was Operation Sunrise, begun in the spring of 1962 to pacify a notorious Liberation Front hotbed north of Saigon, the sector called War Zone D. Six months into the effort just four of fourteen projected strategic hamlets had been set up, and the first one was already falling apart. Countrywide, the program had come to a standstill by the summer of 1963, and after the coup that overthrew Diệm the strategic hamlets were largely abandoned.Footnote 11

The coup against President Diệm ushered in a period of intense political infighting in Saigon. Immediate successors, the military strongmen Dương Vӑn Minh and Nguyễn Khánh, made halfhearted efforts to reenergize pacification programs but were obliged to keep much of their attention constantly on Saigon politics. There were seven military coups or attempted coups between November 1963 and mid-1966. American enthusiasm for pacification stumbled on Saigon’s inward focus. CIA authority Thomas Ahern observes, “the six counterinsurgency programs sponsored or encouraged by CIA in concert with the Diệm government all achieved their greatest effectiveness by late 1962. Thereafter a variety of causes inhibited further progress.”Footnote 12

The Other War

In addition to the overthrow and murder of Ngô Đình Diệm, November 1963 brought the assassination of President Kennedy. LBJ, his vice president and successor, came to the table with a very different attitude. Johnson had made his way in American politics with social and economic programs, all the way back to the 1930s, such as rural electrification and the Tennessee Valley Authority. LBJ appreciated – more than had Kennedy – the importance of giving South Vietnamese citizens a stake in the conflict. If Johnson could have bought the hearts and minds of the Vietnamese peasantry, he would have.Footnote 13 This president not only devoted more attention to these elements of the conflict, he also coined the term the “other war” to connote this aspect.Footnote 14 Indeed the first summit conference between American and South Vietnamese leaders took place at Honolulu in 1966 specifically to focus on economic and social features of the war. President Johnson’s efforts led to the elaboration of actual management structures on the US side of the pacification mission.

A structure to actually conduct pacification operations was a Johnson-era innovation that had not even been dreamed of before. Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge actually took the first steps in the autumn of 1965, when he created a committee within the US mission under Deputy Ambassador William J. Porter.Footnote 15 In Washington, the Vietnam Coordinating Committee chaired by the State Department began parallel deliberations. Early in January 1966 a conference at Warrenton, Virginia, brought together officials from both sides of the Pacific, crystallizing thoughts of providing more structure – a single manager – for pacification initiatives. This thinking was taking hold when LBJ held his summit at Honolulu in February.Footnote 16 Shortly thereafter, on the National Security Council staff, the president designated Deputy National Security Advisor Robert J. Komer as his point man for all things related to the “other war.” Johnson also affirmed Lodge’s choice of William Porter to pull together pacification elements within the US mission to South Vietnam. In National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 343 of March 28, 1966, LBJ put his instructions in a formal directive. This directive – almost the last NSAM on Vietnam strategy President Johnson would ever approve – indicates the seriousness with which he saw this matter.

By December a more formal entity, the Office of Civil Operations, had been created within the mission structure. For the first time this brought the related elements of the CIA, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the spin doctors of the Joint United States Public Affairs Office (JUSPAO) together for a coordinated effort. But pacification work still suffered from a relative lack of resources compared to those for fighting. Komer argued that until military resources could be funneled into pacification few hearts or minds would ever be won. The result, in May 1967, would be creation of an organization directly subordinate to General William C. Westmoreland, the US military commander in Vietnam. Called Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development Support (CORDS), the organization provided a command center for all aspects of pacification activity. President Johnson appointed Komer to lead CORDS as a deputy to Westmoreland and with protocol rank of ambassador. In 1968 CIA official William E. Colby came to CORDS as Komer’s assistant, succeeding him that summer. Komer and Colby became the sparkplugs of US pacification efforts.

In the field, meanwhile, various people from the CIA and USAID were busily crafting tactics and techniques, and had been since Diệm’s time. Oftentimes formulas devised in one place seemed quite successful, but failed badly when applied across the board. Other times Saigon officials objected to projects, appropriated money the United States had intended to finance initiatives, or dragged their feet when implementing both US and South Vietnamese programs. A partial list of the programs and devices would include armed militias (such as Sea Swallows, Civil Guard, Combined Action Platoons, Regional Forces/Popular Forces), strike teams (CounterTerror Teams, People’s Action Teams, Provincial Reconnaissance Units), encouragement of defection projects (chiêu hồi, Kit Carson Scouts), territorial control efforts (chiến thắng, hợp tác), forcible relocation into defended villages, information-gathering and village surveillance teams (Census Grievance, Revolutionary Development), neutralization of the guerrilla hierarchy (Phoenix, Phượng hoàng), and more.

A critical element remained the fuzziness of the strategic picture. Judgments on control over the districts and provinces had long been based on the simple opinions of Saigon officials as reviewed by their American advisors. The softness of this data was plain. After an October 1966 visit to the war zone, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara asked CIA director Richard M. Helms to craft a more refined method. Brainstorming overnight at CIA headquarters, with officers including some from the Special Assistant for Vietnam Affairs (SAVA), others of the Saigon Station, and USAID officials, came up with a report card schema, subsequently refined by SAVA Philip Carver and approved at the US Embassy two months later. American advisors along with their South Vietnamese counterparts would complete monthly reports grading their areas on ninety-seven different political, socioeconomic, and security criteria. As a check on Vietnamese overoptimism the Americans in addition filed separate report cards.

The data was compiled in Saigon and used to rank villages in what became known as the Hamlet Evaluation Survey (HES). Hamlets were graded A through E, with the ones labeled A considered fully loyal to Saigon, B hamlets slightly less well controlled, C ones relatively stable, then D and E were contested in worsening degrees. Liberation Front–controlled hamlets were not graded. While elaborate, HES could not escape from subjectivity – or from the exigencies of war. Beyond dispute the Tet Offensive set back pacification. In its wake CORDS initiated Operation Recovery to regain the lost ground, while a programmatic response called the Accelerated Pacification Campaign soon appeared. As part of the latter, the HES report cards were stripped down, losing grades for land reform, transportation improvement, public health, eradication of illiteracy, and agricultural improvement – and eliminating the requirement to identify corruption among South Vietnamese officials. Meanwhile, it turns out, roughly 20 percent of the 67.2 percent of villages rated as secure (graded A to C) at the time of Tet had not actually been evaluated at all. In 1970 the “secure” percentage was arbitrarily reduced but soon reached a staggering 95 percent. There was an improvement from pacification but it remains difficult to identify precisely – the provinces and districts across South Vietnam that were considered dangerous had long been so. There was a Vietnam data problem that persisted throughout.Footnote 17

At the same time the growing violence of the war itself had the effect of destroying many hamlets and villages and driving people off the land. Between 1964 and 1972 the proportion of South Vietnamese living in the cities increased 13 percent. Excepting Saigon, where much migration had occurred before 1960, large fractions of the population had arrived within the past five or ten years. The number of urban centers with 100,000 to 299,999 citizens increased from two to six during the stipulated period, and ones peopled by up to 100,000 people grew from fifteen to twenty-eight. The military correlation is clear: questioned as to why they had moved, from 1964 to 1966, 55 percent gave war-related reasons and another 16 percent wanted more opportunity; in 1967–8 the war-related figure rose to 63 percent. In 1969–71 war-related migrants diminished to 36 percent but those who had left the land for opportunity’s sake remained high at 14 percent.Footnote 18

Another complicating element in the picture was the evolution of US strategy and politics. After 1968 it became perfectly evident to all sides that the United States could not afford to send additional ground troops to South Vietnam. Peace negotiations telegraphed the United States need to end the war. American politics made apparent the diminution of US power. Yet it was at that same time that CORDS hit its stride and the Americans began an intensive campaign of pacification. Much like the North Vietnamese army, the Liberation Front had an incentive to wait out Vietnamization and the US withdrawal. It is simply not possible to determine how much of what could be observed in the pacification data was attributable to guerrillas’ deliberate strategy versus actual improvement.

One observable was the recorded level of terrorist incidents. This figure increased steadily after 1968, more than doubling by the time it peaked in 1971. In their councils the American commanders viewed this as the Liberation Front, increasingly desperate, trying to attain by violence what it could no longer do by political struggle (đấu tranh). But there was a half-empty/half-full problem with the water in this glass. The data could equally well be read as retaliation for the counterinsurgent violence of the Phoenix Program. Or the statistic might mean something different from how it was taken. Thừa Thiên province included the city of Huế, certainly making it a priority pacification sector. Statistics kept by the senior US advisor in Thừa Thiên show that levels of all kinds – from terrorist incidents to NLF armed attacks – were virtually identical for the month before 1968’s Tet Offensive and the one before 1972’s Easter Offensive.Footnote 19 A CIA report one month into the Easter Offensive reported damage to pacification programs in places where major fighting was in progress, but also in Bình Định province and in the Mekong Delta. The report observed, “In a short time, the Mekong Delta has changed from the most secure and prosperous part of the country to a source of considerable apprehension.”Footnote 20 Whatever pacification had accomplished does not seem to have affected the raw military capability of the People’s Liberation Armed Forces (PLAF) or the North Vietnamese at their side.

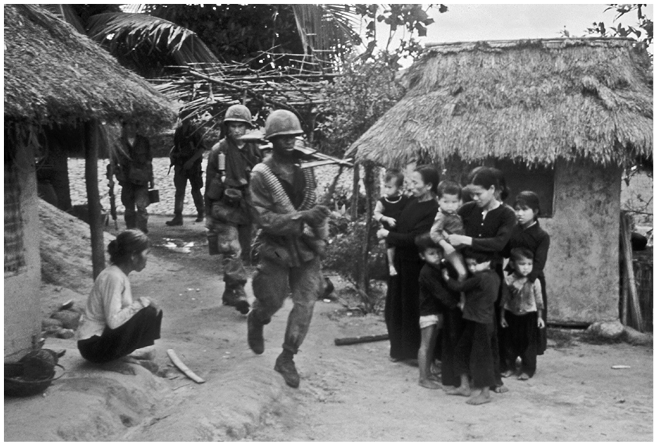

Figure 5.1 Vietnamese women and children huddle together as US soldiers enter their village (May 12, 1967).

Uphill Battle

In the early days of CORDS the Americans engaged in what they called Project TAKEOFF, which was an effort to create a more solid footing for a variety of pacification initiatives. This included elements ranging from building more prisons to house enemy suspects, to greater efforts to induce defections from the Liberation Front, to increasing capacity to handle refugees, to police and military support and mounting a dedicated attack on the NLF infrastructure, to land reform. Those things the United States could do on its own moved ahead, albeit with the kinds of internal conflicts within the US mission already mentioned. Those things that depended on the Saigon government did not exactly languish, but they were not pursued with the energy the Americans deemed appropriate. For someone like Robert Komer, whose antics earned him the sobriquet “Blowtorch Bob,” that state of affairs had to be extremely frustrating. But Komer continued to work as a booster for Vietnam pacification, reporting in 1971 that total US/South Vietnamese funding for pacification had mushroomed from $582 million in 1965 to more than $1.5 billion programmed for 1970.Footnote 21

The analyst who compiled the portion of The Pentagon Papers which dealt with this aspect of the war trenchantly commented, “the Vietnamese have not yet convinced many people that they attach the same importance to [pacification] as we do.”Footnote 22 This was apparent in many ways, every day. The field agent Frank Scotton, whom superiors sent to take the temperature of South Vietnamese officers on the possibility they might fear the expansion of local militias, found the chief of the army’s Political Warfare Department entirely concerned with being a watchdog for army loyalty.Footnote 23 A National Intelligence Estimate in January 1969 concluded that “Saigon now seems finally to have accepted the need for a vigorous pacification effort. However progress may still be hampered by the political situation.”Footnote 24

Or take the case of Trần Ngọc Châu, among South Vietnam’s most successful practitioners of the art of pacification, whose efforts had largely succeeded in pacifying Kiến Hòa province in the Mekong Delta. The techniques Colonel Châu pioneered included the “Census Grievance” and “Revolutionary Development” initiatives, which the Americans picked up but which were viewed with suspicion in Saigon – no Saigon leader after Diệm ever showed up in Châu’s province. The CIA funded a school at Vũng Tàu to teach these methods. Châu was taken away from his province to head it. General Nguyễn Đức Thắng, head of a new Ministry for Rural Construction, issued the order, which Châu later decided had really emanated from his American counterparts.Footnote 25 Although he was among the Vietnamese most dedicated to the effort, Châu soon found the CIA and others had completely different recipes for what he should be doing – and they held the purse strings.Footnote 26 He was soon obliged to try and put a Vietnamese face on a student strike by South Vietnamese trainees at the Vũng Tàu school, even while General Thắng was caught in between Saigon pretenders Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu and Nguyễn Cao Kỳ in their power struggle. Kỳ wanted to make Thắng’s ministry the focal point for programs, while Thiệu wanted to locate pacification within the National Police.

A 1967 reshuffle sent Thắng to the Joint General Staff, where he complained that South Vietnamese corps commanders were sabotaging pacification.Footnote 27 In December 1967 a set of province rankings prepared for Ambassador Komer put Châu’s province, Kiến Hòa, so successfully secured in Châu’s time, as the ninth worst among the South’s forty-four provinces. After the Tet Offensive, a CORDS survey ranked it among the most adversely impacted provinces.

The CIA’s historian of pacification identifies a “gradual drift toward conventional operations.” Commenting on versions of the hunter–killer teams that were attacking local NLF, Trần Ngọc Châu found them to be merely improved versions of similar programs Saigon, or the French before that, had run. Châu estimated that, as a rule of thumb, every cadre killing “created at least five new hard-core National Liberation Front supporters, often more.”Footnote 28 That was nevertheless the tactic CORDS proposed, and Nguyễn Vӑn Thiệu’s government approved, for neutralizing the NLF apparat in the Phoenix Program.

The Phoenix Program (which the South Vietnamese called Phượng hoàng) sought to weaken the Liberation Front’s administrative structure by arresting or killing NLF operatives in the villages and the higher-up district or province committees. In July 1968 President Thiệu issued a decree establishing the program and locating it within the Saigon bureaucracy. The CIA and Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) assisted with intelligence, training and weapons, small-unit leadership, and advice. Interrogation centers at district and province levels, as well as in Saigon, would develop new information and feed the dossiers that supposedly identified enemy cadres. The interrogations generated attendant charges of torture, arbitrary imprisonment, and other abuses. United States authorities remained uncomfortable with these charges and, when “Vietnamization” became US policy, progressively scaled back their participation. The CIA ended its official support in 1970 although it continued to serve as a conduit for US funds to the South Vietnamese engaged in these activities. A few agency officers continued to liaise with Saigon’s Phượng hoàng apparat. MACV ended the service of its Phoenix advisors in 1971, although in August 1972 more than one hundred military personnel were still helping the Vietnamese in some capacity.

President Thiệu not only approved Phoenix, he also designated goals for the number of NLF cadres to be neutralized, and he located a central bureau for the program within his own office. That changed in May 1970 when Thiệu relocated the Phoenix office within the National Police. The program had to surmount numerous obstacles, including early goals more ambitious than could be handled, a lack of trained lawyers and of prosecutors for those arrested and put on trial, arbitrary criteria for judgment, corruption, limited space to house prisoners, and so on. Building more prisons had been a goal of Project TAKEOFF, the CORDS precursor to Phoenix. Another precursor had been the Intelligence Coordination and Exploitation (ICEX) program, which sought to overcome the biggest obstacle, a lack of detailed knowledge of the NLF apparatus. Creating the Provincial Reconnaissance Units (PRUs) was another headache, but ultimately a force of more than 4,400 soldiers was mobilized in units nominally under South Vietnamese command but in practice often led by Americans.

The quality of intelligence remained the most important determinant in the success of Phoenix against the NLF infrastructure. The intelligence remained uneven throughout. Orrin DeForest, a former detective who had joined the CIA and previously worked in Japan, took charge of the spy info for the III Corps region, the portion of South Vietnam that covered the areas outside Saigon and in the Mekong Delta. He believed in classic techniques rather than torture, tricking enemies into revealing key information.Footnote 29 Statistics indeed show that III Corps proved the most successful in neutralizing actual NLF higher-ups rather than just bodies – studies using data from the end of 1970 projected that III Corps, though “neutralizing” about the same proportion of the NLF as other regions, had gotten twice as many cadres ranking at the district level or higher. Over South Vietnam as a whole there were 19,534 neutralizations in 1969 but fewer than 150 were of high-level cadres, and just one was an NLF official Phoenix had specifically targeted. Of 22,341 neutralizations in 1970, high-level cadres more than doubled (to 357) but those eliminated specifically from the NLF hierarchy were reduced (to an estimated 7,800). Considering that these identifications were based upon soft data, that the NLF infrastructure was believed to number between 65,000 and 80,000 people, and that the United States had little understanding of the NLF’s ability to replace its losses, the Phoenix results are indeterminate at best.

In March 1969 the PRUs were designated an element of Saigon’s National Police. By 1971 the CIA station was reporting that the police executive was passive, leaving all decisions back with Saigon’s prime minister. Meanwhile Phoenix became steadily more controversial in the United States, with charges that it was an assassination program.Footnote 30 Hearings in the US Congress challenged William Colby, and the sinister reputation made Phoenix increasingly problematic.Footnote 31 At length, as part of Vietnamization, US military personnel were withdrawn from CORDS, Phoenix, and the PRUs. The CIA removed the last of its people in summer 1972. South Vietnam continued Phoenix as the Phượng hoàng program but, judging from the large numbers of Liberation Front agents and supporters who bubbled up from the populace during the last days of Saigon, Saigon’s special effort proved little more successful than the American one.

Counterinsurgency in the Vietnam War ended more or less where it had begun, with the bulk of efforts devoted to security measures. The kinds of social and economic programs that might have gained the loyalty of South Vietnamese peasants were given lip service, and discontinued whenever resources were thin. Corruption diluted whatever was left. Differences between the United States and the Saigon government on the importance of these programs also weakened them. The opportunity to drain the sea in which the guerrilla fish swam was lost. If Saigon was going to emerge victorious from the war that had begun with Ngô Đình Diệm’s repression, that outcome would not be the result of pacification.