Up until now, our analysis of the Attalid political economy has traced patterns of interaction between royal and civic actors that help explain the success of the Pergamene imperial project. Whether taxing or gifting, the characteristic Attalid finesse was always on display. Genuine negotiation produced the proliferation of earmarking arrangements. As we shall see in Chapter 5, it also had the effect of channeling royal benefaction into the civic gymnasia. As techniques of domination and accommodation, none of this was new. On the contrary, these were time-honored, culturally privileged solutions to the problems of governance. What was new was the intensity with which the Attalids pursued administrative and ideological cohesion, producing new collectivities as fiscal structures aligned interests. However, we have yet to consider what is usually regarded as the most strikingly new, distinctive, and still mysterious feature of their rule, namely, the coinage and, specifically, the cistophori (plural for cistophorus).

These are curious coins. They were minted on a peculiar weight standard. They also lack the royal portraits that genre prescribed. Their very strangeness has provoked radically divergent interpretations. For Fred Kleiner, whose Early Cistophoric Coinage is the standard reference work on the subject, the cistophori were “the king’s money,” a straightforwardly royal coinage.Footnote 1 That position, it must be understood, is polemical. There is a long tradition, stretching back to Alexandre Panel and Joseph Eckhel in the eighteenth century, with Henri Seyrig and Wolfgang Szaivert as its most recent exponents, which regards the cistophori as the federative coinage of cities.Footnote 2 In an authoritative study, George Le Rider writes of the “cistophoric coinage of the Attalids,” but tentatively puts forward a more nuanced vision, suggesting that the kings negotiated the cistophori into existence, and then shared with the cities of Asia Minor the attendant responsibilities and rewards.Footnote 3 This chapter argues that the cities’ cooperation was key not only to the birth of the cistophori but to the maintenance of the entire Attalid monetary system. As an arena of negotiation between city and king, the coinage elicits our attention.

Neither purely royal nor civic, the cistophori defy labels and epitomize the eclecticism of the Attalid state. On closer inspection, we will find other confounding forms of Attalid money, such as the Wreathed Coinages and the so-called “cistophoric” countermarks. From ca. 170 BCE, we enter a transformative period in the history of Greek coinage. The relationship between sovereignty and coinage becomes ever more difficult to untangle. As Olivier Picard has pointed out, to make sense of large new coinages such as the Athenian New Style or Macedonian Meris coinage, we need to lose old labels such as “imitation” or “pseudo-Roman.”Footnote 4 Indeed, this chapter will propose one new schema: coordinated coinage. Achaemenid antecedents aside, the monetary system of the Attalid kingdom at its acme involved civic institutions and promoted civic identities to an unprecedented and ultimately unmatched degree. Paradoxically, this had the effect of extending the kings’ reach over much new territory. In other words, coinage had a role to play in fostering the integration of the various micro-regions of the Attalid state. It is interesting to contrast the testimony of Polybius, for whom coinage was merely an index of state formation and integration (symphronêsis) (2.37.8–11). For the Megalopolitan, the federal coinage of the Achaean Koinon is just one measure of the remarkable transformation of the Peloponnese into, in his formulation, a single polis but for the walls. It is an expression, not a tool of integration. We can go further, attributing to a Hellenistic coinage the power to bind the smaller polities of a royal state to each other and to the crown.

The narrow question of what to call the cistophori – the binary choice of royal or civic coinage – is a fruitless question of cui bono. The cistophoric system generated profits, through the procurement and transfer of bullion, and through the exchange and reminting of old coin. Yet given the present state of our evidence, we cannot so much as guess at the size of these profits and the extent to which the Attalids shared them with the cities. We can, however, observe in the cistophoric system features of both centralized and decentralized control. This hybridity permits us to state with confidence that the inherent profits were shared. Decentralization is emphasized in the explanation of the cistophori set out in what follows mainly because previous scholarship seems to overstate the case for centralization. To emphasize cooperation is not to lose sight of the Attalids as the prime movers behind this coinage, nor to discount their role as the indispensable coordinating force behind the system – to ignore the obvious asymmetries of power. It is instead a means, first, of situating the cistophori in the broader context of Attalid money and, second, of highlighting the distinctiveness of Attalid monetary practice. The chapter first lays out a new understanding of the cistophori: neither royal nor civic, but what we term a coordinated coinage. Second, it proposes an explanation of the various changes in the coinage of the Attalid kingdom, 188–133, set against the wider backdrop of the eastern Mediterranean. But before we can explain them, we need to introduce the coins.

Overview of the Coinages of the Attalid Kingdom, 188–133 BCE

The most current numismatic research on the mint of Pergamon undercuts the notion of a decisive change in 188.Footnote 5 The Attalids had always minted an Attic-weight, which is to say, international silver coinage, and they continued to do so after the Treaty of Apameia (Marcellesi nos. 26 and 42; Fig. 3.1).Footnote 6 The Philetairoi, Attic tetradrachms bearing the face of the founder, have been divided into seven groups by Ulla Westermark.Footnote 7 With minor modifications, Westermark’s groups have been retained, but their absolute dates are not fixed. Andrew Meadows has recently posited a gap in the production of Philetairoi from ca. 190 to ca. 180–175.Footnote 8 Yet the Attalids were minting an Attic-weight silver coinage in the 180s, if indeed their posthumous Alexanders continue from the late third century into this period (Marcellesi no. 32). Meadows has placed a subset of Attalid Alexanders (Price nos. 1491–95) in the 180s, arguing that “Alexander coinage is likely to have been the principal coinage produced by the Pergamene kings during the period of their conflict with Antiochos III, and in the subsequent decade of reorganization of the Pergamene kingdom.”Footnote 9 In other words, the Attalids seem to have preferred to make payments in Alexanders during the crucial start-up years of the enlarged kingdom. Pergamon now joined Miletus and a host of other cities in the region already minting Alexanders. With an eye to making their coinage acceptable and their royalty inconspicuous, the Attalids paused production of the Philetairoi in favor of generic Alexanders.Footnote 10

Figure 3.1 Silver tetradrachm of Eumenes II minted in the name of Philetairos, Westermark Group VII.

At some point in the 180s, a new wave of Attic-weight silver entered the enlarged Attalid kingdom in the form of countermarked tetradrachms of four Pamphylian cities: Phaselis, Perge, Aspendos, and Side.Footnote 11 The Sidetan issues, which predominate, bore that city’s own types; the rest, like many other civic coinages of this period, were Alexanders. A second minting authority placed a countermark on the obverse of the host coin, consisting of a bow-in-case alongside an abbreviated city name or ethnic (Fig. 3.2). These have been named “cistophoric countermarks” on account of the bow-in-case symbol, shared with the cistophori proper, which would seem to refer to the Heraklid origins of the House of Telephos. The cities evoked by the marks were also all in post-Apameian Pergamene territory: Ephesus, Tralles, Sardis, Synnada, Apameia, Laodikeia-on-the-Lykos, Stratonikeia-on-the-Kaikos, Adramyttium, Toriaion, the long unidentified ΕΛΗΣ, ΕΛ/ΛΗ, ΕΛΛΗ, and Pergamon itself.Footnote 12 However, these countermarks and the cistophoric coinage itself were not contemporaneous. The so-called cistophoric countermarking seems to end in the early 170s, just before the cistophori, on the “low chronology,” begin.Footnote 13 Indeed, seven of the twelve known cities referred to by the countermarks correspond to cistophoric cities. While Sardis appears on the countermarks the most, Ephesus barely registers. This is significant because Sardis plays a minor role and Ephesus a major one in the production of cistophori, implying shifting priorities or purpose.Footnote 14

Figure 3.2 Silver tetradrachm of Side minted ca. 210–190 BCE, bearing countermark of bow-in-case + ΠΕΡ.

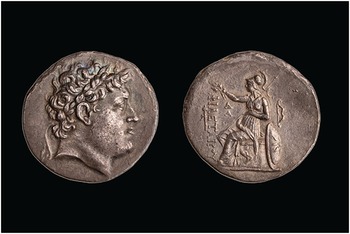

The cistophori are one of the great numismatic puzzles of Classical Antiquity. The term cistophorus is an ancient one, usually used by Moderns to refer to the tetradrachms of a system that included didrachms and eventually drachms.Footnote 15 It is the tetradrachm alone, however, which, bears on its obverse the wicker chest or ritual basket, the so-called cista mystica, with its lid ajar and a serpent emerging (Marcellesi no. 45; Fig. 3.3). An ivy wreath wraps around the field. On the reverse, the tetradrachm displays two snakes on either side of a bow in its case (gorytos). The reverse also bears various symbols and the name of a city – or an ethnic – usually in abbreviated form, for example, ΕΦΕ or, less often, as a monogram.Footnote 16 The didrachms (Marcellesi no. 46; Fig. 3.4) and post-Attalid drachms (Marcellesi no. 49; Fig. 3.5) share types: on the obverse, a club draped with a lion skin, wrapped in a wreath; on the reverse, a bunch of grapes on a vine leaf, and again, various marks and the shortened version of a city’s name/ethnic. The tetradrachm, which will be referred to here as the cistophorus, per the convention, is the dominant denomination; the didrachms and the later drachms, which will be referred to as the fractions, are rare by comparison. (By “cistophori,” we mean all three denominations.) The cistophoric tetradrachm was minted at a theoretical weight of ca. 12.6 g, the didrachm at 6.15 g, and the drachm at 3.05 g.Footnote 17 This weight standard is singular, if also relatable to its contemporaries, with a cistophorus weighing roughly the same as three Attic-weight drachms or Roman denarii, and the drachm a negligible 0.05 g heavier than the Rhodian plinthophoros.Footnote 18

Figure 3.3 Cistophoric silver tetradrachm of Pergamon, ca. 160–150 BCE.

Figure 3.4 Cistophoric silver didrachm of Tralles, ca. 145–140 BCE.

Figure 3.5 Cistophoric silver drachm, ca. 134–128 BCE.

The iconography of the mythological repertoire glimpsed on the cistophori is bewilderingly complex.Footnote 19 Perhaps it was meant to be so, and therefore it managed to appeal to a broad range of users, Greek and Anatolian, while remaining politically and culturally anodyne. Alternatively, the peculiar combination of myths depicted eludes conclusive interpretation because it is not preserved in any other media. Commentators since Warwick Wroth in the nineteenth century have emphasized different divine attributes, the snake of Asklepios, ivy and grapes of Dionysos, arms and lion skin cloak of Herakles, without offering a comprehensive interpretation of the visual program.Footnote 20 One tends now to describe cistophoric iconography as a mixed bag. For example, asserting that the Attalids “considered Pergamon as a sort of Athens of the east,” Elizabeth Kosmetatou argues that the cista and snake of the obverse represent the myth of Erichthonius and Athena, while also allowing that the visual frame of the ivy wreath may refer to the dynasty’s favored cult of Dionysus Kathegemon.Footnote 21 For Marie-Christine Marcellesi, the coins are a savvy mix of Bacchic and Heraklid imagery. The cista, then, would be part of the paraphernalia of the mystery cult of Dionysos Kathegemon, while the citizens of Pergamon, as the descendants of Telephos, would be vindicated by the symbols of Herakles.Footnote 22 In fact, any number of these conclusions is open to debate. For example, in an exhaustive study of the cults of Pergamon, Erwin Ohlemutz finds no sign of the mystery cult of Dionysos Kathegemon on the coins.Footnote 23 Rather, an ancient viewer may have seen the cult of Demeter and Persephone in the image of a snake-in-a-box.Footnote 24 We tend to focus on the cista, at least in part, because we happen to have it in a Greek and later Latin term for the coin. Yet the most dominant motif overall is the snake – with one on the obverse and two on the reverse. To a different ancient viewer, these could have been the “snake-bearing coins (ophiophoroi).”

It is worth bearing in mind that some or all of these snakes may belong to a class of benevolent serpents (drakônes).Footnote 25 This distinguishes the cistophori from famous coin types such as the silver of classical Chalchis, which exhibits a predatory eagle holding a serpent in its beak and claws, and the hunch can lead us in several interesting directions.Footnote 26 The heraldic pair of standing snakes on the reverse of the cistophorus almost seems to guard the gorytos of Herakles. Are these snakes in fact friendly to the house of Telephos? Apparently, some serpents were friendly to the Pergamene hero. In a possibly Sophoclean version of the myth, a snake stood up to prevent the hero from consummating his marriage with his mother Auge, the very scene depicted on Panel 21 of the Great Altar’s inner frieze.Footnote 27 Moreover, an important precedent among the coin types of Pergamon should be brought into the discussion. A large number of bronzes were minted in the name of Philetairos from the 270s until the early second century that bear a standing snake on the reverse (Marcellesi no. 18; Fig. 3.6). A reference to the popular, pre-Attalid cult of Asklepios is certainly plausible given echoes on the god’s own bronze and that of Hygieia (Marcellesi nos. 59–60, 62), but the snake on the Philetairos bronze, lacking omphalos or staff, also bears a striking resemblance to the one saving Telephos from Oedipal sin on the Great Altar (Fig. 3.7). Indeed, if we cast a wider net, we find plenty of contemporary myths of foundation that involve friendly snakes, most relevant among them, the argolai, which are said to have aided Alexander in Alexandria.Footnote 28 The Alexander Romance suggests that household snakes as friendly spirits (agathoi daimones) had well-known associations with Hellenistic royalty.Footnote 29 Meanwhile, Iron Age Anatolia seems to have contained its own tales of founder-snakes and serpentine progenitors. Strabo tells us of the snake-men as heroes of the tribes of the conspicuously pro-Attalid city of Parion, and a recurrent motif on the coinage of Pisidian Etenna shows that non-Greek myth mixed easily with Greek when it came to friendly snakes.Footnote 30

Figure 3.6 Standing serpent on reverse of large module (hemiobol?) bronze coin in the name of Philetairos, ca. 270s–200 BCE.

Figure 3.7 Fragmentary bedroom scene from the Telephos Frieze with standing serpent warning hero and Auge.

From an administrative standpoint, the cistophori are slightly less mysterious. We can be reasonably certain of the identity of most of the pre-133 cistophoric mints – at least the major ones (Map I.3). There are two tiers in terms of volume of production: the large, regular mints, which are Pergamon, Ephesus, Tralles, Apameia, and, to a lesser extent, Sardis (Synnada in Phrygia was once thought to be Sardis-Synnada);Footnote 31 and the small, irregular ones: Laodikeia-on-the-Lykos; Adramyttion, which is attested by a single pre-133 coin, though it became a major mint from the time of the Revolt of Aristonikos;Footnote 32 and, finally, a smattering of small mints whose identity is contested, but at least four seem to be south Phrygian: Blaundos, Dionysoupolis, Dioskome, and Lysias (or Synnada?). The mystery mint ΚΟΡ may be Kormasa in the Milyas.Footnote 33 Quantitatively speaking, an overall volume of roughly 50 obverse die equivalents per year points to Attalid initiative and bullion resources behind coins that deliberately obscure – and indeed efface – the kings’ role. Meanwhile, the cistophori represent Attalid minting on an unprecedented scale. François de Callataÿ has estimated the value of the cistophori at 6.5 times that of the annual average of pre-170 Philetairoi.Footnote 34

Dating the Cistophori

The terms of the debate on the vexed question of the date of the introduction of the cistophoric system have narrowed in recent years.Footnote 35 For the high chronology, Karl Harl and Marcellesi rely on the testimony of Livy, who records the display of cistophori in four Roman triumphs between 190 and 187. Marcellesi sees the Attalids minting the new coins at Pergamon in the run-up to the war with Antiochos III. After the victory, the system was expanded to include the other mints in the new territories.Footnote 36 Many other numismatists dismiss Livy’s testimonia as anachronism, and have instead concentrated on the period between 188, when the political geography of Asia Minor was redrawn, and ca. 166–ca. 150, when the coins start to turn up in the Delian accounts. The debate turns on the dating of a portion of Westermark Group VII Philetairoi, reclassified as Nicolet-Pierre issues 19–25.Footnote 37 These Philetairoi share control marks with what are understood to be early cistophori. Leaving aside for a moment the important point that the Attalids struck the cistophori and this Attic-weight regal coinage simultaneously, one needs to decide on dates for this group of the latest Philetairoi. Their presence in the Maaret-en-Nouman hoard (northwest Syria) provides a terminus ante quem of 162.Footnote 38 But it is difficult to determine how much earlier they began, and how long they took to travel from Pergamon to Syria and into the ground. For the overlap of Philetairoi and cistophori, Meadows argues for the lowest chronology yet, ca. 165–ca. 160, and points to a coin of Alabanda minted in 167/6 on the cistophoric standard as supplementary evidence of their existence.Footnote 39

Many scholars posit 181 as a further terminus ante quem for the launch of the cistophori on the basis of Richard Ashton’s interpretation of a letter of Eumenes II to Artemidoros, the Attalid governor of the Lycian outpost of Telmessos (D3).Footnote 40 The letter concerns benefactions for the inhabitants of the Kome Kardakon, who had fallen on hard times.Footnote 41 The key passage reads: “Since it is necessary for them to pay arrears on the poll-tax, each of them four Rhodian drachmas and one obol, but since, in light of their suffering, this is not within their means, let this amount be remitted this year, and from next year, let them pay one Rhodian drachma and one obol (καὶ ἐπεὶ τῆς συντάξεως δεῖ διορθοῦσθαι αὐτοὺς ἑκά̣στου σώματος ἐνηλίκου Ῥοδίας δραχμὰς τέσσαρας ὀβολόν, ἀσ̣θενοῦντες δὲ τοῖς ἰδίοις βαρύνονται, τά τε παραγραφόμενα αὐτοῖς ἐκ τοῦ ἑκκαιδεκάτου ἔτους ἐκ τούτων ἀφεῖναι, ἀπὸ δὲ τοῦ ἑπτακαιδεκάτου ἔτους Ῥοδίαν δραχμὴν καὶ ὀβολόν)” (lines 10–14). Ashton calls attention to the significance of what he deems the curiously unrounded number of the tax. He takes it as given that the poll-tax was normally paid at a rate of four “Rhodian” drachms and one obol, which, if the Rhodian coins are indeed Rhodian plinthophori, is equivalent to a total of ca. 12.6 g of silver, the weight of the cistophorus. This would mean that in Telmessos, in the vicinity of the Rhodian zone of control, the Attalids had decided to collect a tax collected elsewhere in the kingdom as a cistophorus in an equivalent amount of Rhodian coined silver. Therefore, the curiously unrounded number of the tax levied at Telmessos tells us that the cistophorus already existed in the kingdom at large. It is an ingenious conjecture, but should not be mistaken for an unimpeachable fact. The decree only states that the Attalids had been unable to collect the 12.6 g of Rhodian silver coins from the Kardakoi. Significantly, they then permanently lowered the tax rate to a figure, one Rhodian drachm and one obol (3.5–6 g), which bears little relation to the weight of the cistophoric drachm (3.05 g).Footnote 42 Was the attempt to integrate the Lycian outpost into the new monetary system so quickly abandoned? Rather, the Telmessos text only demonstrates that in 181 the Attalids were employing a unit of account that would later be expressed in the cistophorus. The origin of the unit of 12.6 g may lie in fiscal experimentation, but 181 cannot be posited as a terminus ante quem for the cistophoric system, which was introduced some time after ca. 175.Footnote 43

Attic-Weight Coinage

Whether we date the cistophoric reform to the 170s or 160s, it is becoming increasingly clear that the introduction of the cistophorus did not spell the end of production of Attic-weight coinage in the kingdom.Footnote 44 In fact, we are only just coming to recognize the impressive scale of Attic-weight, “international” coinages minted in the final decades of Attalid rule. Of those that are patently royal, to the aforementioned Group VII Philetairoi we must add an extremely rare issue of tetradrachms bearing a portrait of Eumenes II, dated by Hélène Nicolet-Pierre to 166–159 (Fig. 3.8).Footnote 45 Two other silver coinages known from a very small number of specimens seem to be related to officially sanctioned cultic activity: the tetradrachms of Athena Nikephoros, usually placed in the mid-160s (Fig. 3.9), and a tetradrachm from Teos, but issued in the name of a group with deep ties to the Attalid court, the Association of the Artists of Dionysus, dated by Catherine Lorber and Oliver Hoover to the 150s. Meadows has added a further coinage to the mix from the mid- to late 140s. These are tetradrachms that show Demeter on the obverse and the Kabeiroi encircled by a wreath on the reverse, in much the same fashion as the reverse of the Eumenes II portrait coins. Their legend, however, reads not ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΕΥΜΕΝΟΥ (“of King Eumenes”), but ΘΕΩΝ ΚΑΒΕΙΡΩΝ ΣΥΡΙΩΝ (“of the Syrioi Kabeiroi”). If Meadows is correct in attributing this coinage to the Attalids, it would be of more than antiquarian interest. By the looks of the die counts, this was a very large coinage, on the same scale as the cistophori in the same period of production.Footnote 46

Figure 3.8 Silver tetradrachm of Eumenes II, ca. 166–162 BCE.

Figure 3.9 Silver tetradrachm in the name of Athena Nikephoros, reign of Eumenes II, ca. 180–165 BCE.

Several cities within the Attalid kingdom also minted Attic-weight coinage after the introduction of the cistophorus. For example, the gold drachms of Tralles, minted on the Attic standard, share control marks with the cistophori Kleiner-Noe series 9 and 41.Footnote 47 Signaling the city’s autonomy, it seems that Tralles minted the two gold issues at two distinct periods of its history. Of much greater importance to the regional money supply were the many Ephesian silver drachms with bee on obverse, stag on reverse (Fig. 3.10). Philip Kinns has established an early phase for this coinage that ends ca. 170, as well as a later phase for which he gives only the terminus ante quem of ca. 150.Footnote 48 It is indeed likely that Ephesus was producing Attic drachms and cistophori in parallel. The cases of Ephesus and Tralles, cities awarded to the Attalids at Apameia as gifts (dôreai; Polyb. 21.46.10), point up the difficulty of using coinage to determine the political or fiscal status of a community after 188.Footnote 49 The same can be said of Temnos, which, while under tight Attalid control, continued to mint its Alexanders in the 150s and 140s.Footnote 50 Monetary production is just one arena for the negotiation of sovereignty. As Thomas Martin has shown, the ancient Greeks possessed little loyalty to an abstract connection between sovereignty and the right to mint.Footnote 51 For the cities of the Attalid kingdom, it is not possible to extrapolate monetary behavior from the political status assigned at Apameia.Footnote 52

Figure 3.10 Silver drachm of Ephesus with legend “of the Ephesians,” ca. 150 BCE.

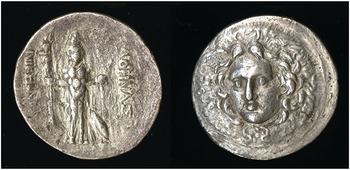

Finally, the most significant Attic-weight coinages produced in the Attalid kingdom in these years are the so-called Wreathed Coinages.Footnote 53 These are silver tetradrachms bearing the civic types and ethnics of coastal cities, the obverse framed by the wreath that gives them their name (Fig. 3.11). The cities in question are Aigai, Kyme, Myrina, and Smyrna in the Aeolian core; Lebedos; Magnesia-on-the-Maeander; and Herakleia-under-Latmos. With good hoard evidence and die studies available, Callataÿ has been able to date the Wreathed Coinages ca. 154–135, although the mints operated on different schedules.Footnote 54 Still, even on the lowest chronology, the cistophori and the Wreathed Coinages are contemporary developments. It should be noted that several other coinages of the middle two quarters of the second century share the wreath design, for example, coins of Macedonia under Philip V, of Eretria and Cyzicus, and the Athenian New Style tetradrachms. This is evidence not of a monetary union, as some have hypothesized, but of a popular fashion in coin design that may have served to enhance the coins’ acceptability.Footnote 55

Figure 3.11 “Wreathed” silver tetradrachm of Myrina, ca. 160–135 BCE.

The Wreathed Coinages circulated similarly to other Attic-weight coinages of Asia Minor. They do not appear in the thin hoard record for mid-second-century Asia Minor, but they do turn up in Levantine hoards of the 150s and 140s.Footnote 56 We do not need ad hoc political or military explanations to explain why silver moved from the Aegean to the Near East, where the higher value of silver relative to gold had since Achaemenid times attracted Greek coinage to the Levant.Footnote 57 Indeed, the Wreathed Coinages participated in an old circulation pattern that intensified in this period. What needs to be explained is the size of these coinages, which share common designs and originate in cities firmly under Attalid control. Callataÿ estimates a total of 76.8 Attic-drachm equivalent obverses per year for the Wreathed Coinages – compared with just 51.9 for the pre-133 cistophori!Footnote 58 Tipped off by the size of the issues, scholars since Rostovtzeff have suspected Attalid involvement.Footnote 59 The notion of a “proxy coinage” may seem less conspiratorial after the discussion below. Leaving open for now the question of the precise nature of Attalid involvement with the Wreathed Coinages, it is difficult to understand how these cities minted in such quantities without injections of bullion from the outside.

Explaining the Cistophori

Scholars have struggled to define the character of the cistophoric coinage, vacillating between civic, royal, and federal models of minting. The inherited paradigms fail us, in part, because the coins look so strange. However, their visual strangeness need not be explained away in our analysis. Attalid silver and indeed bronze had always born the portrait of Philetairos, nearly always with the legend ΦΙΛΕΤΑΙΡΟΥ, “of Philetairos.” That combination of image and text was standard practice across the Hellenistic world. In their design, the cistophori mark a radical break with the past – and with convention, in a medium that is famously conservative.Footnote 60 Not only do these coins renounce the claims of the typical Hellenistic coin legend; they also replace the dynastic portrait with imagery sufficiently generic or enigmatic, it seems, to evoke a wide range of associations. They leave us asking, “Whose money is it?” On the other hand, the coins bear symbols, control marks, which without question derive from the iconographic repertoire of the various cities involved. This is best observed in Ephesus, where the bee and stag (along with the quiver of Artemis), appear on the cistophori; meanwhile, Ephesus had for centuries placed that same imagery on its own coinage, and in fact continued to do so, even after the introduction of the cistophori, on its common Attic-weight drachms.Footnote 61 In the markets adjacent to its new harbor, the one built by the engineers of Attalos II, traders handled both coinages in tandem. Or consider the case of Tralles. It provides another clear instance of identifiably civic badges on the cistophori: the humped bull, the meander pattern, and, perhaps, Zeus Larasius. The bull we find on the aforementioned gold coinage of Tralles, and the meander pattern, so important to the civic and regional identity of the city, appears already on pre-188 bronze.Footnote 62 Kleiner sought to limit the phenomenon to Tralles and Ephesus, but his own catalogue shows its breadth. Some Apameian cistophori bear flutes (of Marsyas), and Laodikeian ones display the punning wolf (lykos) for the Lykos River.Footnote 63 To match image with text, then, we are justified in following Le Rider, who restores cistophoric legends as ethnics, not mintmarks, as, for example, ΕΦΕ[ΣΙΩΝ], “(coin) of the Ephesian (citizens).”Footnote 64 The coins represented the citizens – of their respective poleis – just as much as the kingdom.

To cast the cistophori as either strictly royal or civic in nature is to explain away their visual strangeness. Either one argues that the combination of civic iconography and muted reference to the crown signals the withdrawal of the Attalids from the domain of coinage, a restatement of the laissez-faire, constitutional vision of Attalid imperialism, or the coins dissemble and mask the kings’ interventions. In that sense, as Kleiner puts it: “The cistophoric coinage is not what it appears to be.”Footnote 65 Yet a coin in this world was always, in some sense, what it appeared to be. According to the classic formulation of an inscription from Sestos honoring the late Attalid courtier Menas, the benefits of introducing any new epichoric coinage were of two kinds (I.Sestos 1 lines 44–45).Footnote 66 First, the community was able to place its own charaktêr on its coins. Second, the coinage would become a source of revenue (prosodos) for the community through mandatory exchange, reminting fees, and so on. Unfortunately, on the present state of the evidence, we cannot say anything about who laid claim to the surely considerable profits of the cistophoric system, or in what proportions. Tellingly, Kleiner relates the fiscal structure of the cistophoric system to the practice of earmarking. In his view, they were both forms of bait-and-switch fiscality, tribute disguised as taxation and redistribution.Footnote 67 On the other hand, we must admit that the Attalids ceded away a certain part of the charaktêr of this coinage, and the text from Sestos provides explicit confirmation of the significance of that aspect of coinage for late Hellenistic cities. Meadows has gone so far as to suggest that the political significance of minting with epichoric types was changing and in fact intensifying in precisely this period.Footnote 68 Therefore, it seems prudent to take the cistophori at “face value,” even if this means ruling out conventional models of royal or civic coinage. The strange appearance of the coins hints at the same Attalid sensitivity to civic identity and the same reliance on civic institutions that undergirded the practice of earmarking. Yet any new characterization of the cistophori must rest on the evidence of the coins themselves for the administration of the system.

The Devil in the Administrative Details: The Evidence for Centralization

To underline the point, the coins do not give us a balance of accounts, how much city and king – or indeed third parties, like merchants – each invested in the system, and how much each took out. And this problem is not unique to Attalid Asia Minor. In a programmatic essay on late Hellenistic coinage, Picard has sized up our aporia with the question, “Where does the metal come from?”Footnote 69 No metallurgical analysis is available to trace the origin of the various stocks of silver bullion used to mint early cistophori.Footnote 70 On the other hand, we can at least try to determine where the minting took place, and how the shape of the money supply and the rhythm of monetary production were managed. To begin with the organization of the cistophoric mints, Kleiner’s Early Cistophoric Coinage (ECC) appears to have overstated the case for centralized production. Le Rider and Otto Mørkholm have offered criticisms of ECC on this score, but given the status of Kleiner’s book as the standard of reference for the coinage, its arguments deserve further scrutiny, since for Kleiner, what he calls “inter-city linkage” would “necessitate a complete reconsideration of the nature of the cistophoric coinage.”Footnote 71

ECC does not postulate two tiers of mints, large and small, as we have above. The system of ECC contains just three central mints that produce all the coins, whichever their charaktêr: Ephesus, Tralles, but, most importantly, Pergamon itself, the administrative hub, minting for a number of smaller pseudo-mints. Central to Kleiner’s argument is a notion of intercity linkage that includes not only die links, but also shared symbols, monograms, and, crucially, the stylistic links that Kleiner observes throughout the coinage. Numismatic method privileges the evidence of die links over stylistic links, but the number of die links in the ECC corpus is surprisingly low.Footnote 72 In fact, there are only two instances of verifiable die-sharing between mints, both involving Pergamon.Footnote 73 The first is the link between Kleiner’s P24 of Pergamon and S10 (series 6) from “Sardis-Synnada.”Footnote 74 Noting that “Sardis-Synnada” series 6 is itself die-linked to the then as yet un-deciphered ΒΑ ΣΥ ΑΡ cistophori, Kleiner argued for the unlikelihood of a single die traveling between the royal capital, Lydia, and Phrygia. Since then, Le Rider has suggested that “Sardis-Synnada” is actually two mints, Sardis and Lysias in south Phrygia; that the monogram on the reverse of the obverse die-linked coin at issue should be read “Dionysoupolis”; and that the ΒΑ ΣΥ ΑΡ coins come from Blaundos, both Dionysoupolis and Blaundos themselves also lying in south Phrygia.Footnote 75 All this still leaves us with the circulation of at least one die between two or perhaps three regions. Its possible mintmark notwithstanding, Blaundos, for example, does not seem to have been urbanized under the Attalids.Footnote 76 So the need for greater centralization in rural south Phrygia makes sense. We cannot rule out a traveling mint that accompanied the retinue of Eumenes II, who might have faced the Galatians at both Sardis and Synnada.Footnote 77 Edward Robinson demonstrated a roving mint for Aristonikos.Footnote 78 Whatever the arrangement here, it was short-lived, irregular, and confined to an early stage, perhaps under the peculiar conditions of the Galatian War.

Much more suggestive of centralization is the second case of die sharing, known from an impressive five links between Pergamon and Apameia: Kleiner’s A17/P38, A24/P46, A28/P54, A38/P75, and A40/P79. Moreover, Kleiner’s observation that the pace of production at both mints was increasing simultaneously is intriguing. It at least implies that both mints faced a sharp increase in demand for coinage at the same time and coordinated a response. But were these actually two distinct mints? If one assigns to Pergamon the 16% of production currently credited to Apameia, a more centralized system emerges with just three mints functioning. However, many of the die linkages have been challenged.Footnote 79 It was also quite common for dies and die-cutters to pass between mints.Footnote 80 The detailed study of Christophe Flament on the mechanics of minting in Classical Greece highlights the pitfalls of using hand studies to demonstrate centralized production.Footnote 81 Yet Kleiner’s observations of hands is what sustains much of his model of centralization, from Apameia to the mystery mint ΚΟΡ to his claim that Tralles struck for Laodikeia.Footnote 82 There are clear signs of coordination by a central authority, but we also find hints of local participation and information sharing. Apameia seems to have minted its first civic bronze coinage about now, which shares the symbol of the pilos with early cistophori.Footnote 83 For the late cistophori, the civic mint was certainly involved, as the magistrate ΚΟΚΟΥ appears on both the silver cistophori and the civic bronze coinage.Footnote 84 In sum, it still seems probable that Apameia possessed a mint under the Attalids.

It must be admitted that the cistophori display remarkable uniformity of type. The imagery is consistent, as is the placement of the ethnic and the symbols (Figs. 3.3 and 3.12). The weight of the coin and the size of the flan do not change much either.Footnote 85 Most importantly, the repetition of symbols on the coins of different mints implies a coherent administrative system. On the other hand, we find striking anomalies, such as the letters on a limited number of series from Ephesus (33–35) and Apameia (27–28), usually taken to be regnal years. Whether the letters on either of these coinages actually represent regnal dates, and why these cities alone and not Pergamon itself would have marked time in this way are both open questions.Footnote 86 The salient point is that different administrative systems were at work in different places. This implies that local actors and institutions influenced the production of the cistophori. We get a sense of just how important local officials might have been under the Attalids from the behavior of their mints immediately after 133. While the Ephesians were quick to place their city’s civic era on the coins, the citizens of Pergamon minted cistophori bearing the names of their prytaneis.Footnote 87 Had those magistrates shared the responsibility for minting with royal officials all along?

Figure 3.12 Cistophoric silver tetradrachm of Ephesus, ca. 150–140 BCE.

The Peculiar Role of Tralles

… that they think it just the same, whether they arrive in Tralles or in Formia …

Die sharing is just one of the twin pillars of the case for centralization. The other is the specialization of the mint of Tralles in the production of small denominations. These are the didrachms and drachms that survive in much smaller numbers than the cistophoric tetradrachms (Figs. 3.4 and 3.5). This unmistakable peculiarity of Tralles in this respect fulfilled the needs of local users on the border between two large regional monetary systems. Thus, ECC lists 16 obverse drachm dies and 18 obverse didrachm dies for Tralles.Footnote 89 No other mint comes close.Footnote 90 However, the traditional view is that the Attalids arbitrarily assigned small change to Tralles. “It is unlikely that the silver currency needs of Tralles differed substantially from those of the other large Attalid cities,” writes Kleiner.Footnote 91 On this interpretation, royal needs motivated Tralles’ designation, which represents the ultimate instantiation of the “royal design” behind the cistophoric system. Even those who model decentralized production assume centralized control of the shape of the supply of coin. For example, Callataÿ: “The fact that the mint of Tralles was in charge of nearly all the fractions points too in the direction of a general policy established at a higher level.”Footnote 92 It is also commonly assumed that the Attalids decided unilaterally to focus the production of fractional coinage in Tralles. As Thonemann writes, “The cistophori were produced at a number of decentralized mints. Their production, however, was closely directed from the centre.… [Tralles’ specialization] strongly suggests that the distribution and scale of the mints did not necessarily reflect the coinage’s circulation.”Footnote 93

In fact, the special role of Tralles was neither arbitrary nor the outcome of a unilateral royal decision. Further, the case of Tralles may even shed light on circulation patterns. Consider first that the city continued to specialize in fractions – and even intensified its production of small denominations after the fall of the Attalid dynasty. In his study of the very large coinage known as the “late cistophori,” minted from ca. 133 to ca. 67, Kleiner found that Tralles retained its traditional role.Footnote 94 The only hoard of late cistophori that contains fractions is IGCH 1460 (unknown provenance in Asia Minor). It contains 2 drachms and 7 didrachms, all of them, except for a single drachm of Ephesus, from Tralles. Kleiner did not make a companion die study of the late cistophori, but he does note that the late fractions of Tralles are overwhelmingly dominant in both public and private collections.Footnote 95 In trying to understand the persistence of the pattern, it is important to remember that early Roman administrators were cautious and practical. We could see here simply the rote reproduction of an administrative procedure and the inertia of bureaucracy.

However, a meaningful pattern emerges when we consider a yet later stage in the long history of the cistophori. When production of the late cistophori ended ca. 68/7 in the context of Pompey’s operations in the East, a 10-year hiatus ensued.Footnote 96 Around 58, the cistophori appeared again, this time bearing the names of cities, but also two personal names, one Greek and one Latin. These are the so-called proconsular cistophori, which carry the names of Roman proconsuls and local Greek magistrates. The coinage ends ca. 49 BCE with the issue of the propraetor L. Aemilius Lepidus Paullus. Gerd Stumpf’s corpus of proconsular cistophori does not record any fractions.Footnote 97 Yet this is because the one fraction that can be associated with the proconsular cistophori does not bear the typical two names, but just the Greek one. The coin is a didrachm minted by a certain ΑΡΙΣΤΟΚΛ[ΗΣ] (BMC Lydia 335, no. 55).Footnote 98 The same Aristokles of Tralles, we presume, is known to have minted proconsular cistophori (tetradrachms, bearing the city’s ethnic) for both C. Claudius Pulcher (Fig. 3.13) and C. Fannius (Stumpf nos. 55, 63, and 65). It is unclear whether Aristokles’ name appears alone on the didrachm due to considerations of space in the visual field or whether this is an expression of a different institutional arrangement. Either way, it appears that Tralles – and perhaps only Tralles – was minting fractions after a decade-long hiatus.

Figure 3.13 Proconsular cistophoric silver tetradrachm, signed by C. Pulcher and Aristokles, 55–53 BCE.

After all the intervening disruption, why was it Tralles, yet again, which specialized in fractions? We need not imagine that its citizens held a monopoly on the technological know-how. Rather, we need to take seriously the possibility that the monetary needs of this city had been distinctive all along. In other words, we need to examine the economic and historical geography of the Maeander Valley. Thonemann’s study of the long-term history of the Maeander region illustrates how it can either connect or separate different stretches of Anatolia. He views Apameia both as a limit point for the Attalid imperial space and as an interchange between the steppe of inner Anatolia and the coastal lowlands.Footnote 99 The Maeander after 188 was very much a political frontier, chosen to mark the boundary between Rhodes’ domain on the mainland (peraia) and the expanded Attalid kingdom. In economic terms, perhaps this frontier was more permeable. Thonemann’s study does not offer us any idea of what an interchange would look like that connected the Rhodian zone of southwestern Asia Minor to the Attalid Maeander and beyond. Tralles fits the bill perfectly.

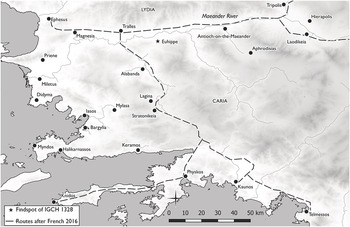

Positioned at the junction of several important trans-Anatolian routes, Tralles also joined Attalid Lydia to Rhodian Caria (Map 3.1). Branching off from the primary route between the coastal delta and the upper Maeander, the major route south into Caria took off from Tralles. In Pergamene terms, it connected Tralles to Alabanda, and, ultimately, Telmessos. But another branch connected Alabanda to Lagina, Stratonikeia, and, finally, Physkos (Marmaris), on the mainland opposite Rhodes.Footnote 100 The road from Alabanda to Tralles connected Caria to the Attalid’s southern highway, a stretch of the road that was to become one of the main arteries of the Roman province of Asia.Footnote 101 Strabo’s source Artemidoros of Ephesus (fl. 104–101 BCE) traveled it. In his testimony, Artemidoros is explicit about how he conceptualizes the road. For him, the road was part of a route from Physkos to Ephesus. Thus, Strabo: “Artemidoros says that the journey from Physkos, on the coast opposite Rhodes, towards Ephesus, as far as Lagina is 850 stadia; thence to Alabanda 250 stadia; to Tralles 160. About halfway, on the road to Tralles, the Maeander is crossed, and here are the boundaries of Caria. The whole number of stadia from Physkos to the Maeander, along the road to Ephesus, is 1180 stadia” (14.2.29).Footnote 102 For Artemidoros, note, Tralles was the middle point on this route, in terms of both distance and conceptual geography. Tralles was the end of Caria.Footnote 103

Map 3.1 The Maeander Valley and Rhodian Caria.

By location, therefore, Tralles was a monetary interchange between, on the one hand, the Rhodian zone to the south, where Rhodian and pseudo-Rhodian coinages on epichoric standards dominated for centuries, and, on the other, the young cistophoric zone. After 188, but seemingly before the advent of the cistophorus, the Rhodians reformed their own coinage, minting the plinthophoros.Footnote 104 The Rhodians may have designed the plinthophoros to be even more epichoric than other Rhodian and pseudo-Rhodian coinages in circulation.Footnote 105 In any case, the plinthophori, like other coinages on the various “Rhodian” standards, circulated throughout the Rhodian peraia and rarely left the zone. For their part, the cistophori almost never left the Attalid kingdom. The Maeander Valley, then, formed the border between two large, relatively impermeable regional monetary systems.Footnote 106 Passage between the two would have necessitated an exchange of currencies. And if the volume of those exchanges were higher than elsewhere, the demand for small denominations would also have been elevated. Indeed, if we accept that Tralles linked the Rhodian zone to the cistophoric zone, then as an interchange between two major epichoric systems, Tralles was sui generis as an Attalid mint.Footnote 107

To test the hypothesis of high-volume currency exchange in and around Tralles, we may look to the thin but suggestive hoard record. As noted, fractions of Tralles dominate the only known hoard of late cistophoric fractions, which is the unprovenanced IGCH 1460. For the cistophori of the Attalids, we are luckier. We still have just one hoard containing fractions, but it has a provenance. IGCH 1328 (Şahnalı) contains 18 pieces of cistophoric silver, 10 of them fractions. Again, among the fractional mints, Tralles predominates, with four didrachms. But the other mints are represented too: one didrachm apiece from Pergamon, Ephesus, Apameia, and “Synnada.”Footnote 108 While the Şahnalı hoard provides further confirmation of Tralles’ special role, it also sheds light on circulation patterns in the system. In other words, it is important to notice that the hoard contains coins from all the major mints, both cistophoric tetradrachms and fractions. It could be what numismatics call, with all due caution, a “circulation hoard,” the proverbial snapshot of what was in circulation at a given place and point in time.Footnote 109 The hoard was found near the site of ancient Euhippe, which lies just opposite Tralles, south across the plain of the Maeander, not far to the east from where the route of Artemidoros entered and exited the Valley, on the way from Tralles to Alabanda in Caria.Footnote 110 We simply do not have the hoard evidence to test the representativeness of the Şahnalı hoard in terms of circulation, though it is unquestionably representative in terms of content; that is, the common fractions of Tralles predominate. This is an isolated piece of evidence, but it suggests a pattern of circulation that concentrates fractions from all over the Attalid kingdom in the vicinity of Tralles, on the very edge of the cistophoric zone.

The hypothesis of heavy traffic between the Rhodian and cistophoric zones, channeled through Tralles, which produced a high volume of currency exchange, motivating the special role of Tralles in the cistophoric system, finds support in the behavior of mints south of the Maeander after the introduction of the cistophorus. In reaction to the creation of the cistophoric zone, these cities minted a portfolio of coinages on different standards, which allowed them to maintain their economic ties to the Maeander and profit from their own position of connectivity. After 167, the Rhodian political hegemony in Caria and Lycia began to collapse, but southwest Asia Minor was still very much part of the Rhodian monetary koinê.Footnote 111 In Caria, Alabanda in the 160s minted not only Attic-weight Alexanders, but also a coinage on the cistophoric standard.Footnote 112 With this coinage, Alabanda was not pledging fealty to Pergamon. It remained outside the Attalid kingdom, even if Eumenes II was inching into the power vacuum.Footnote 113 The Alabandan “cistophori” imply significant traffic back and forth along the first stretch of the Tralles-Physkos corridor, and represent one state’s attempt to integrate the two regional systems to its advantage. Similarly, Carian Stratonikeia, which lay further south along the same route, minted a curious denomination in this period, an Attic tridrachm alongside an Attic drachm in a system otherwise dominated by plinthophoric drachms and hemidrachms.Footnote 114 Meadows has pointed out that the weight standard of Stratonikeia’s Attic-weight tridrachm, ca. 12–12.5 g, made it interchangeable with a cistophorus. In northern Lycia, Oinoanda may have pursued a similar strategy, minting silver didrachms that equated nicely with the cistophorus at the ratio 3:2.Footnote 115 Another north Lycian city, late Hellenistic Kibyra followed Alabanda and minted its own cistophoric tetradrachms and drachms (BMC Phrygia, pp. 131–32, nos. 1–5). The north Lycian cases are without firm dates, floating between the mid-second and early first centuries BCE. For our purposes, it need not matter. Clearly, the spread of the cistophorus into southwestern Asia Minor was a slow, intermittent, century-long process, still being completed in the early first century BCE.Footnote 116 Along the way, it was useful for those cities situated on major routes in and out of the Maeander Valley to mint an appropriately flexible coinage.

Another measure of the extent to which Tralles straddled two monetary zones is the poor survival rate of its coins. Low survival rates may provide indirect evidence that cistophoric fractions were leaking out of the cistophoric zone faster than the cistophori themselves. The loss of small denominations is a case of the notorious “problem of small change” studied by economic historians Thomas Sargent and François Velde.Footnote 117 The drachms of Tralles are known from 18 specimens (n) and 16 dies (D), a ratio of nearly 1:1; the didrachms are 30 (n) and 20 (D), exactly 3:2.Footnote 118 Numismatists, with theoretical backing from statisticians, typically seek a sample of n/D = 3:1 before undertaking a die study.Footnote 119 Using a lower ratio is dangerous because it is not possible to estimate the original number of dies with any degree of certainty. In other words, we must admit that we do not have any idea of the scale of Tralles’ production of cistophoric fractions. However, we do know that Tralleian fractions survive very poorly. The average n/D for the entire cistophoric coinage (166–123 BCE) is 2.75 (1,142/416).Footnote 120 So, while the sample size is small, the fractions of Tralles are significantly below the average at 1.5 for the didrachms and 1.125 for the drachms. But how do those rates compare with other small silver of second-century Asia Minor? Kinns’ study of the copious silver drachms of Ephesus (ca. 202–150 BCE), produced an n/D of 8.43 (590/7).Footnote 121 On the other hand, the Rhodian plinthophori (ca. 185–84 BCE) survive at a much more comparable rate of 1.91 (1,583/829), as do the Stratonikeian hemidrachms (130–90 BCE) (4.92 = 305/62) and the pseudo-Rhodian drachms of Mylasa (165–30 BCE) (5.79 = 619/107). Hoarding practice may account for the problem. It could be that small silver in a multidenominational system was hoarded differently – that is, less – and so survives less often. An apposite comparison is available from Bithynia of the reign of Prousias II (189–149 BCE). His silver drachms are extremely rare by comparison to his tetradrachms.Footnote 122 We may also consider the possibility that the high volume of currency exchange on either side of the “cistophoric frontier” just south of Tralles contributed to a distinctive circulation pattern for the fractions, and so a lower rate of survival. The plinthophoric drachm weighed about as much as the cistophoric drachm (3.05 g), but we can hardly suppose that money changers were willing to make the exchange for free.Footnote 123 Did those who went south take the fractions of Tralles with them, exchanging these coins inside the plinthophoric zone, where they eventually met the melting pot?

The weight of the evidence shows that local needs and preferences determined the choice of Tralles as the chief fractional mint in the cistophoric system. Or to put it another way, regionalism inflected the shape of the money supply in the Attalid kingdom. Consider again the regional situation along the Maeander, but now against the backdrop of the wider Hellenistic world. As Picard has illustrated, the typical late Hellenistic monetary system was built around large silver and fiduciary bronze, with little coinage at the intermediary values.Footnote 124 Few regional systems reserved an important role for small silver. The exceptions to this rule were two: the symmachic Peloponnese and the Rhodian zone that intersected with the cistophoric zone at Tralles. In the late third or early second century, Rhodes even raised a tax (or a public subscription?) called the didrachmia (SEG XLI 649).Footnote 125 Moreover, the imitative cistophoric production of Kibyra in northern Lycia seems also markedly biased toward the fraction. No comprehensive study exists, but a survey of major collections reveals a nearly 3:1 advantage for Kibyra’s cistophoric drachms over its tetradrachms (30:9).Footnote 126 The Tralleian cistophoric fractions are representative of the affinity of southwest Asia Minor for small silver. In the end, there were good reasons for Tralles to specialize; the choice was not arbitrary.

In sum, the case of Tralles is a far cry from proof that the Attalids held fiat power when it came to the shape of the money supply. Naturally, the people of Tralles possessed some notion of how to shape it themselves. Recall that they minted Attic-weight gold staters in two issues ca. 167–133. They may very well have minted civic bronzes in this period too.Footnote 127 It also remains possible that civic authorities in Tralles applied a countermark of their own, the bull protome, to certain Attic-weight silver tetradrachms from outside the kingdom.Footnote 128 Therefore, one can conceivably find local inflection up and down the complete range of value. Yet for poleis, just as important as the shape of the money supply was the rhythm of monetary production. As noted, the cistophoric system contains several administrative anomalies. From Tralles, we have intriguing signs that the rhythm of minting was not set on high. These are the unusual combinations of letters and monograms on Kleiner-Noe series 33–35, tetradrachms, didrachms, and drachms, which Ashton has read as Macedonian months.Footnote 129 Again, the sample size is small, and the die links imply a perhaps short-lived experiment. None of this disproves the existence of a central authority in the cistophoric system. It merely alerts us to the existence of countervailing forces of decentralization. When it came to money, Tralles wanted what every Greek state wanted in order to combat the “anarchy” of the ancient monetary world: some measure of control over the rhythm of the production of coinage – and with it, the shape of the money supply; some room for supple reactions to changing conditions.Footnote 130

Closure and Closed Currency Systems: The Ptolemaic Model

So much about Tralles was royal. It had fallen to the Attalids as a “gift” city at Apameia, and it seems to have displaced Sardis as the chief administrative center of the region. In Tralles, the Attalids constructed a palace and may have received extraordinary cultic honors.Footnote 131 However, the city’s minting reminds us of the complexity of the relationship between sovereignty and coinage in ancient Greece.Footnote 132 Yet, prima facie, Tralles seems unlikely to have exercised influence over the design of the scaffolding of the cistophoric system. Just outside the city’s gates was an open-air royal military encampment.Footnote 133 If the introduction of the cistophorus necessitated negotiation, Tralles was not in a position of strength. Yet the character of the cistophoric coinage was not “royal,” if by royal we mean that the coinage expresses raw domination. We must reckon with the iconoclastic appearance of the coins, while the role of royal authority in the system also cannot be denied. This is because the cistophoric zone was a closed monetary system. The only state around capable of launching and maintaining an epichoric coinage on this scale and territory was Pergamon, even if nothing was possible without the cooperation of the cities.

Confronted with a closed currency system within a Hellenistic kingdom, scholarship has always turned to well-documented Ptolemaic Egypt as both the historical and interpretive model for the cistophori. From Rostovtzeff to Mørkholm, the Attalids were seen to have taken direct inspiration from the Ptolemies.Footnote 134 For Le Rider and Callataÿ, the Attalids imitated the Ptolemies, but the model belonged to no one; closed currency systems were simply the norm in both classical and Hellenistic Greece.Footnote 135 Lost in all this is the distinctiveness of the Attalid case. In other words, even more than the term “royal,” the notion of closure lacks nuance in most accounts and potentially leads us astray. Unchallenged, the inapt Ptolemaic comparison impedes our understanding.Footnote 136

Leaving aside the question of its origins and motivations, how did the Ptolemaic system work in practice?Footnote 137 We know surprisingly little, but it is clear from the hoards that foreign coinage, both Attic-weight and foreign epichoric, ceased to circulate in Egypt ca. 310–ca. 300.Footnote 138 Over this period, the weight of the Ptolemaic silver coinage descended progressively from the Attic standard of ca. 17.25 g to its own epichoric standard of ca. 14.25. Around the same time, Ptolemy I also introduced reduced-weight gold and bronze coinages.Footnote 139 According to Gresham’s law, the reduced-weight coinages in precious metals would have forced the full-weight (i.e., Attic-weight) coinage, much of it foreign, out of circulation; and market forces alone would have kept Ptolemaic gold and silver coins from leaving Egypt, since their local value so exceeded their international one.Footnote 140 Yet it appears that the Ptolemaic state had a more active role to play in creating the homogeneity of the hoards. Relying on the indirect evidence of P.Cair.Zen. I 59021 of the year 258, one generally sees an official prohibition on the use of foreign coinage in the form of a prostagma issued ca. 300. Unfortunately, we do not possess the text of a law, just that famous letter of the mint official Demetrios to the royal dioikêtês Apollonios. It depicts a frustrated foreign merchant class waiting to change foreign (epichorion) gold coins and old Ptolemaic trichrysa into new Ptolemaic mnaieia after the reform of Ptolemy II. Their money is lying idle. The lesson is that, in Egypt, there were no options. The Ptolemaic state created a system in which the exclusive legal tender was whatever local coinage the king ruled valid. Buying and selling, all payments public and private, were to be conducted in the local coinage sanctioned by the Ptolemaic state.Footnote 141

Therefore, part of the standard reconstruction of economic life in Ptolemaic Egypt is the following scenario. A foreign trader arrives at port. To buy an export cargo, he will have to obtain Ptolemaic coinage. To buy Ptolemaic coinage, he must bring his foreign coinage into the country. It is possible that the import of coinage was taxed.Footnote 142 Having paid customs, the trader goes to a bank, where he changes foreign coinage into Ptolemaic coinage at officially prescribed rates of exchange – taking a 17% (?) loss on silver, perhaps even more on gold.Footnote 143 Of course he keeps some amount of foreign coinage on hand in anticipation of his final departure from Egypt. He wants to avoid repurchasing foreign coinage from the bank, coinage that he will need when he arrives at his next port of call. Foreign coinage was not contraband in Ptolemaic Egypt, but unacceptable as legal tender. This is why it is so rarely found in hoards post-ca. 300, but, occasionally, it does turn up.

To compare the situation in second-century Asia Minor, when the Attalids introduced the cistophorus at a weight 25% below the Attic standard, they ensured that the coins would not travel far. Royal authority clearly granted them a premium above their international value as silver bullion. This explains why we essentially never find a cistophoric coin in a hoard outside the Attalid kingdom – and indeed the singular example of one such coin in the Larissa hoard is usually considered an intrusion (IGCH 237; buried ca. 165). The cistophoric zone was closed in the sense that the cistophori did not slip out too easily. As Meadows points out, these silver coins behave just like any epichoric bronze: with all their fiduciary value, they are meant to stay put.Footnote 144 Yet the Ptolemaic – or Olbian – notion of closure was something else.Footnote 145 There, exchange as such was closed to foreign coinage, whether gold, silver, or bronze. In other words, whatever its real value in Egypt as precious metal, or its fiduciary value elsewhere as coin, non-Ptolemaic coinage could not serve as a means of payment in the Ptolemaic state. Contrary to popular belief, there is no firm basis for the view that the Attalids similarly banned the use of non-cistophoric coinage within the territory of their kingdom or even within some “cistophoric core,” the existence of which is scarcely visible in the hoard record and is in fact contradicted by the epigraphic record.Footnote 146 Ultimately, the cistophoric system outlived the Attalids and all their edicts. Yet to argue for a “hard” notion of closure, one often points to the hoard record for pre-133 cistophori, which, again, is poor in the extreme.Footnote 147 Almost all of the hoards contain only cistophori. However, the earliest hoard to include cistophori is mixed, the 1962 “Asia Minor” hoard IGCH 1453, containing 71+ silver coins, 42 of them cistophori, the rest, various Attic-weight coins, including five Pergamene. Meadows dates the deposit of this hoard to ca. 150 but is agnostic about its findspot.Footnote 148 To preserve the picture of a Ptolemaic-style closed system, Christof Boehringer, in publishing the hoard, placed it on the frontier between the cistophoric zone and the neighboring Attic-weight zone within the boundaries of the kingdom of Bithynia.Footnote 149 Yet consider also the fact that an unmixed hoard of 37 cistophori was found at Türktaciri on the Upper Sangarius, in the hinterland of Pessinous (CH VIII 446). That hoard, known as the Polatlı hoard, does not make the Galatian frontier part of the cistophoric core. Rather, it reminds us that the borders of the monetary zone as much as the kingdom were permeable and mutable. Among its 37 coins is a range of some of the earliest and latest series, right down to autonomous cistophoric issues of Ephesus securely dated 131/0.Footnote 150 In addition, all five of the largest mints are represented, in regular proportion to their size, making trade, as much as warfare, a plausible explanation for it on the Sangarius. Either trade or warfare could also explain the Ahmetbeyli hoard from the opposite, Aegean fringe (CH IX 535). Further, a large hoard of 120+ cistophoroi was found in the nineteenth century in Afyonkarahisar (IGCH 1415). Does it derive from a single military campaign or from healthy trade at the great emporion of Apameia?Footnote 151 We must admit our ignorance. In the end, what the evidence of hoards tells us is that the ancient user generally kept separate stores of cistophoric and non-cistophoric coinage, not that the Attalids proscribed the use of foreign coin. Hoarding practice does not necessarily reflect what was used or in circulation.Footnote 152

The logic of such a hoarding practice is that the monetary system is ramified. Different payments require different currencies. For the Attalid kingdom, then, we can reconstruct the following scenario. A foreign trader arrives at an Attalid port or at an inland interchange like Tralles, and he first pays customs. To what extent does he then change his foreign coinage, Attic-weight or epichoric, into cistophori, assuming he does not possess a reserve of them like the merchants of the Antikythera shipwreck?Footnote 153 The answer is that it depends on what kinds of payments he will make – and this is the crucial difference between the Ptolemaic and Attalid situations. For in the Attalid system, cistophoric coinage must have been required only for a certain a set of payments. Chief among these payments would have been official payments: taxes, fees, rents, and others, and so our hypothetical foreign trader could certainly not have avoided purchasing some cistophori. Of the official status of the money changer that he went to, we can say nothing. Yet in light of the comparative evidence, we can be fairly certain that the Attalid state fixed either the exchange rate or the exchange fee (agio), or perhaps both. In the fifth century, the Athenians set an official agio for the exchange of foreign coinage into owls in the so-called Coinage Decree (ML 45 line 5).Footnote 154 The citizens of Pontic Olbia set an official rate of exchange for their coinage against Cyzicene electrum staters (Syll.3 218 lines 24–26). In the end, this is part of the logic of any epichoric coinage: the state, whether it be a polis like Sestos or the Ptolemaic kingdom, gained revenue by forcing people into currency exchanges, and then profiting from its position of monopoly power over some aspect of those exchanges.Footnote 155

For a host of other payments inside the Attalid kingdom, one might have preferred or been compelled to make payments in Attic-weight silver or gold; or in a different epichoric coinage, the Rhodian, in places with strong economic ties to Rhodes, its peraia, and the Cyclades; or for small transactions, in the local epichoric bronze that cities minted without Attalid participation and without reference to the cistophoric standard.Footnote 156 It may have been that the deeper one went inland, the greater the number of payments requiring cistophori. But it need not have been so. Wherever you went, people were making payments in multiple coinages.

The Attalid Model

If we adopt a ramified vision of coinage in the Attalid kingdom, we can resolve several outstanding problems. The first is the troublesome matter of the extraordinarily high cost of exchanging non-cistophoric coinage for cistophoric. Assuming one exchanged an Attic-weight silver tetradrachm for a cistophorus, the commission was 25%, plus whatever agio was charged. The conventional agio in ancient Greece seems to have been ca. 5–7%, so the total premium of the cistophorus would have been near 30%.Footnote 157 Again, the Ptolemies are seen to have set a precedent with the high rate of exchange of 17%, their agio being around 10%, for a similarly high total premium of around 30%. Yet how can we compare the alluring resources of Ptolemaic Egypt with those of Attalid Asia Minor? To buy Egyptian grain, the premium was evidently palatable, and the Ptolemies in the Nile Valley enjoyed the perfect ecological niche for enforcing monopoly. In an analogous fashion, and perhaps with Ptolemaic support, the cities of Byzantium and Chalcedon profited from their peculiar ecology on the Bosphorus, but overreached ca. 235–220 when they tried to force an exchange rate of ca. 19% on users.Footnote 158 This is a limiting case: it seems that Rhodes went to war over the issue, and the closed currency system failed. Byzantium and Chalcedon lacked the resources to sustain the enterprise. For their part, the Attalids enjoyed neither a preciously unique ecological niche nor a productive base that could have justified a demanded premium of 25+%. There are no echoes in the sources of resistance to such measures, which surely would have represented a painful restructuring of economic life, nor signs of the kind of coercive enforcement necessary to sustain a truly closed currency system on this territory. It is impossible to explain how the Attalids managed to impose and maintain the kind of closed system that succeeded in Egypt but ultimately failed in the Propontis. However, this is a question mal posée. Those are inappropriate points of comparison.

We can now also make sense of the large amount of Attic-weight silver minted in Attalid Asia Minor after the cistophoric reform, with both royal (Marcellesi nos. 42–44) and civic types. First, we can dispense with the idea that these were “export coinages.” By sheer volume, they must have been an important part of the money supply of Asia Minor. Consider, for example, that Myrina produced a total of 445 Attic drachm obverse equivalents in Wreathed Coinage, while Ephesus coined a total of 486 in Attalid-era cistophori.Footnote 159 Of course, as international coinage, these coins were particularly useful for exchange with outsiders. Yet we need not doubt that they passed between insiders too, if we can accept that there existed a series of nonofficial payments for which these coins were legal tender. Selene Psoma restricts these transactions to the fairs of religious festivals, where in her view, locals were required to use Attic-weight coinage to make purchases.Footnote 160 These were largely big-ticket items like slaves and livestock, and the vendors were outsiders. She adduces the tetradrachm of the technitai of Dionysus (of Ionia and the Hellespont), and the Attic silver called for in the Archippe dossier from Kyme, prescribed for the purchase of a victim. Indeed, one could explain the rare gold staters of Tralles similarly. Like Kyme, the city needed to buy a bull for a festival sacrifice. Yet why should the city be required to purchase the bull (1) from an outsider and (2) under the special conditions of festival commerce? The associations of the technitai, after all, were regional; in Asia Minor, they were intimates of the Attalid court – these were not outsiders. Psoma’s point is salutary, but she has isolated only one of the contexts for which Attic-weight coinage would have been usable and useful.

It is difficult to shine a light directly on those other contexts for Attic-weight coinage in the Attalid kingdom, but we possess tantalizing clues such as the Athenian New Style tetradrachm with the countermark of bull protome (Thompson no. 184b). Margaret Thompson dated the issue of the coin, in Athens, to 175/4, but the whole series has long been downdated. On David Lewis’ influential chronology, the Athenians issued the coin some 33 years later.Footnote 161 Picard’s downward shift is only 20 years, but he also questions the assumption of uninterrupted minting.Footnote 162 On any of these chronologies, a coin minted at least one or two decades before 133 can plausibly be imagined to have entered circulation in the Attalid kingdom. The same is true of a related coin, the Sidetan tetradrachm that recently surfaced at auction bearing both the bull protome countermark and a cistophoric countermark – this Attic-weight coin obviously circulated in the late Attalid kingdom.

The problem is a familiar one of how to interpret the countermark. Rather than see it as remonetizing a coin that is no longer money once it travels inside the cistophoric zone, we can see it as expanding the range of transactions for which the coin is acceptable. Whoever conveyed this tetradrachm considered it money. The countermark only extended its acceptability, and perhaps cleared up some ambiguity about its value. For example, was the slightly lightweight New Style tetradrachm really worth four Attic drachms? The countermark did not remonetize the coin, but may have allowed it to enter the transactional sphere of local taxes. It is a stark reminder that civic fiscality had its own relationship with coinage to maintain.Footnote 163

Dispensing with the Ptolemaic model also allows us to clarify the role of bronze coinage in the Attalid monetary system after the cistophoric reform. In Egypt, closure meant the application of standard ratios of value between Ptolemaic gold, silver, and bronze. Thus, when the Ptolemies altered the weights and denominational structure of their bronze, the papryi reflect the consistent application of the new ratio. Around 260, Philadelphos was even able to impose a heavy bronze coin at value equal to his silver drachma.Footnote 164 Granted, the Attalid state will have had a hand in fixing the rates at which moneychangers in the kingdom sold their cistophori, rates that were reckoned in gold, bronze, or other silver. The state had to safeguard its profit with a fixed exchange rate – precisely what the Athenians do in the Coinage Decree, or what we see the Roman emperor Hadrian attending to in an Imperial-period decree from Pergamon (OGIS 484). Yet the Attalids minted no gold and, at the beginning of the second century, appear to have stopped minting bronze in the name of Philetairos.Footnote 165 New bronze issues appear in the era of the cistophori, a civic bronze in the name of the citizens of Pergamon (Marcellesi nos. 63–67) and coins in the name of deities such as Athena Nikephoros and Asklepios Soter (Marcellesi nos. 53–62). Crucially, their denominational structure and, therefore presumably, the values affixed to bronze coinages changed little from the third to the second century. Larger denominations (obols and diobols) are added in the second century.Footnote 166 Yet we see no reform of the bronze to match the cistophoric reform in silver, such as is visible in the case of the Rhodian plinthophori.Footnote 167 Effectively, the Attalids had at most an indirect influence over the value of bronze coins trading in an entire sea of transactions.Footnote 168

The value of bronze coins was not determined solely by the asking price for cistophori, but far more directly by the issuing authorities. And those authorities were the cities of the Attalid kingdom, which granted a fiduciary value to their own bronze coins. This has often escaped notice because it has long been conventional to use 133 as a terminus post quem for many late Hellenistic bronzes of Asia Minor, to assume, unjustifiably, an Attalid prohibition of civic bronze.Footnote 169 Long-running excavations in the imperial metropole have turned up a restricted range of other cities’ bronze.Footnote 170 The picture that emerges is of each city attending to its own needs for bronze, choosing the value and acceptability of coin for this tier of the monetary system. We are very far indeed from Ptolemaic Egypt.

The Cistophori: A Coordinated Coinage

Part of the justification for examining in detail the incongruence of the Ptolemaic and Attalid systems is that we can now distinguish the banal from the exceptional. A ramified monetary system, which coupled closure, in the form of a silver coinage removed from the international standard of its day, with an openness absent from Egypt (and Rhodes?) was in fact commonplace. The impermeable Ptolemaic system and the open system of the Seleukids were, in fact, the outliers of the Hellenistic world. The norm for most Greek states was a mixed regime: epichoric coinage was required for one set of transactions, while the rest, to paraphrase the decree of Olbia, was a matter of persuasion.Footnote 171 This is just what we have envisioned for the Attalid kingdom. It is instructive here to recall that in the late 180s, the Attalids had twice asked the Kardakes for a certain tax to be paid in Rhodian coin. It should then be no stretch of the imagination to propose that after ca. 167, the Pergamene state was prescribing a specific coinage – the cistophori – for a certain set of official payments. This exposes what is truly strange about the cistophoric system: its size. Instead of imitating the Ptolemies, the Attalids acted rather like a polis with an exceptionally large chora.Footnote 172