Early modern apocalyptic and anti-Catholic discourse draws on a wide range of Classical, biblical, medieval, and Humanist ideas. In this chapter, I explore how these intellectual strands are used before and after the Reformation. I then examine how theatrical and visual culture draws on such strands, suggesting how they relate to the generic, national, and international preoccupations of early modern drama. My main argument is that the seventeenth century sees the development of a flexible apocalyptic and anti-Catholic discourse closely attuned to political tensions within the state.

I

One problem faced by early modern Humanists is how best to understand the very different accounts of creation, matter, and the end of the world found in Classical texts and in Scripture.Footnote 1 Book one of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (8 CE) offers Christian readers an alternative account of the world’s creation and destruction. As Arthur Golding’s 1567 translation has it:

Matter is not created ex nihilo as in Genesis but preexists the moment that it is brought into ‘order’. Ovid goes on to explain that after the four ages, Jove becomes angry with mankind and determines to destroy it in a great flood. He chooses this method over bolts of lightning because he fears to set the heavens on fire, and also because:

Despite the difficult idea of Chaos, which does not fit well with an ex nihilo account of creation, generally these Classical theories are syncretised with Christian ideas in Humanist culture.Footnote 3 Indeed, Ovid is often quoted approvingly in apocalyptic writing, as in the commentaries of John Napier (Reference Napier1593) and Hugh Broughton (Reference Broughton1610).Footnote 4 At the start of the Metamorphoses, Ovid draws on the Epicurean physics and cosmology of Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura (c. 54 BCE), a text that has recently received a great deal of scholarly attention.Footnote 5 Lucretius’ controversial argument (developed from Aristotle) that ‘nil posse creari / de nilo’ (1. 155–156) is also used in defences of Christian cosmology, natural science, and providentialism during the period, as in John Dove’s A Confutation of Atheisme (Reference Dove1605) and Ralph Cudworth’s The True Intellectual System of the Universe (Reference Cudworth1678).Footnote 6 Lucretian ideas may be alluded to in King Lear’s ‘Nothing will come of nothing’ (I.i.89), and it is notable that this play explores the interplay between Classical and Christian theories of creation and destruction by drawing extensively on apocalyptic language and imagery.Footnote 7 To consider the end of the world is to consider physical matter itself, how it came to be, and how it might eventually be destroyed.

The discussion of prophecy and empire in Virgilian texts also influences the Reformers’ interpretations of Revelation.Footnote 8 In book six of Virgil’s Aeneid (19 BCE), Aeneas listens to the prophecies of the Cumaean Sybil and goes with her into the Underworld: ‘Ibant obscuri sola sub nocte per umbram / perque domos Ditis vacuas et inania regna’ (6. 268–269).Footnote 9 After leaving the Underworld, Aeneas’ own famous prophecy of a Roman golden age under Augustus Caesar follows (6. 777–807).Footnote 10 Such passages underpin the connection between prophecy and the imperial theme in the apocalyptic commentary tradition, especially the idea of a universal ruler or last world emperor with powers of renovatio.Footnote 11 Other Classical descriptions of the Underworld are important, not least those found in Seneca’s plays, which are so influential for early modern dramatists. In the first act of Thyestes (first century CE), Tantalus says:

In early modern England, the most well-known dramatic fusion of these Virgilian and Senecan tropes is found in Thomas Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy (c. 1587–1592), one of the most frequently performed plays of the period. As Frank Ardolino has shown, Kyd offers a sharp critique of Spanish imperialism towards Portugal (and by extension England) through a typically Humanist elision of Classical and apocalyptic language. Building on this work, Eric Griffin has argued that the play is concerned with the entanglement between ‘two nations which read the present in terms of mythic past and an apocalyptic future that have long since determined its meaning’.Footnote 13 This imperial model and its internationalist perspective are influential for other dramatists, as I explore more fully in the next chapter.

Other Classical ‘apocalypses’ could be mentioned here. Book one of Virgil’s Georgics (c. 29 BCE) contains a famous account of heavenly tumult, omens, earthy battles, ghosts, natural disorder, and opened graves, all of which signal disaster and which Virgil uses to rouse Rome to greater imperial glory (1. 461–514).Footnote 14 This passage is often invoked in discussions of empire and apocalypse. It is quoted, for instance, by William Fulke in his Praelections (Reference Fulke and Gifford1573) and by Broughton in A Revelation of the Holy Apocalyps (Reference Broughton1610).Footnote 15 Virgil even makes an appearance in the popular Protestant Geneva Bible, mentioned by Francis Junius in his marginal commentary to Revelation.Footnote 16 A passage in book two of the Georgics (‘septemque una sibi muro circumdedit arces’, 2. 532–540) is sometimes used by commentators on Revelation to confirm that Rome and Babylon are synonymous. As William Perkins asks in his Lectvres vpon the Three First Chapters of Revelation (Reference Perkins1604): ‘What boy, I say, in the Grammer schoole doth not vnderstand this to be meant of the citie of Rome, although the Poet in that place doth not once name Rome?’Footnote 17 Last, sections of Lucan’s Pharsalia (c. 65 CE) describing the eventual fall of the Roman Empire and the battle between Pompey and Caesar are often used in apocalyptic writing.Footnote 18 English Protestant exegetes give imperial Roman discourse a Christian gloss. The fact that so many of these commentators explicitly oppose the Roman Church and Spain (and later in the century France) shows how English apocalyptic writing often casts national opposition to Roman Catholic and Hapsburg (or Bourbon) rule in an imperial light.Footnote 19

Many of these intellectual strands would have been familiar to Dante, Wycliffe, Chaucer, or Langland.Footnote 20 Reformers in the late-medieval period criticise both ecclesiae and religio.Footnote 21 Luther begins as an Augustinian monk with a soft spot for Virgil who tries to reform the Roman Church from within.Footnote 22 Anti-papalism is a medieval invention informed by imperial Classical discourse.Footnote 23 It is the political establishment of the Reformed Churches across sixteenth-century Europe that allows Protestants to lay claim to the medieval language of anti-papal critique. It also enables them to tap into an apocalyptic tradition that is the common heritage of all Christians and to recast it as one of the most powerful languages in Protestantism’s rhetorical arsenal, anti-popery. To this end, a number of late-medieval and Humanist writers reconsider the relationship between prophecy and history.Footnote 24 One important strand is found in the writings of the Calabrian mystic and prophet Joachim of Fiore. The Joachimite tradition has a clearly defined ‘historicist’ slant. It interprets temporal and spiritual history together as moving through the Augustinian six ages, marked by the Trinitarian status of father, son, and holy spirit. Only when the last status is achieved will the world move towards the renovatio or seventh age promised at the end of days.Footnote 25 Such ideas are culturally influential across Europe. In the words of one scholar, ‘Renaissance ideas of restoration and reformation in both Catholic and Protestant circles owed some of their hope to the expectation stemming from Joachim’ and his belief that ‘the Book of Revelation expressed a continuous history of the Church and the hope of further improvement to that Church within human history.’Footnote 26 These ideas inform texts such as Thomas Wimbledon’s famous fourteenth-century sermon given at Paul’s Cross. Drawing on Joachim and Hildegard of Bingen, Wimbledon argues that

if thou see in the seculer menne that darknesse of syn beginneth to haue the mastry it is a token that the world endeth. But when thou seest Priests that be put in the top of sufferancie of spirituall dignitye, that should bee as hyls among the common people in perfect lyuing, that darkenesse of sin hath got the vpperhand of them, who doubteth but that the worlde is at an ende? Also Abbot Ioachim in the exposition of Ieremy sayeth That from the yeare of our Lorde. M.CCC. all times be to be suspected to mee and wee be past this suspect tyme, nigh CC yeares.Footnote 27

The connection between anti-clericism and the imminent apocalypse finds a ready audience before and after the Reformation: Wimbledon’s sermon was often reprinted during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote 28 Apart from shaping how medieval radicals interpret the prophetic and apocalyptic books of the Bible to comment on the ills of contemporary society, Joachimite theories of renovatio and a last world emperor who purges society in anticipation of the end times retain their appeal well into the early modern period. Such ideas are found throughout the commentary tradition and in popular compendia such as Stephen Batman’s The Doome warning all men to the Iudgement (Reference Batman1581). I explore this tradition further in Chapter 4.Footnote 29

This essentially optimistic strand of thinking is contrasted by a more pessimistic approach found in the writings of the Lollards, or Wycliffites. This group often criticise the medieval papacy and predict its overthrow.Footnote 30 John Wycliffe’s De Pontificum Romanorum Schismate was probably written in the late 1370s/early 1380s in response to a notorious ecclesiastical schism. Because of a disputed papal election, rival popes vied for preeminence in Rome and Avignon. In the text, Wycliffe offers an apocalyptic interpretation of the crisis: ‘For þis unkouþe discencioun þat is bitwixe þes popes semeþ to signyfie þe perilous tyme þat Poul seiþ schulde come on þes laste dayes.’Footnote 31 Despite this particular claim, however, Wycliffite thinking also uses an ‘allegorical representation of the continual sufferings of the true Church’, one that needs to be decoded and interpreted.Footnote 32 Perhaps the most well-known medieval text that brings the historical and the allegorical together is William Langland’s great dream vision, Piers Plowman (B Text c. 1376–1379). This poem ends with antichrist and his followers besieging Holy Church and Conscience resolving ‘To seken Piers the Plowman’ (XX, 383).Footnote 33 Although the point is open to debate, the poem’s conclusion comes down on the side of ecclesial reformation rather than overthrow, even if the apocalyptic framework implies that the latter will not be long in coming.Footnote 34 Piers Plowman remained popular after the Reformation, championed by writers such as Robert Crowley as a forerunner of Protestant concerns.Footnote 35 As he explains in his 1550 edition of the poem, it was written:

in the tyme of Kynge Edwarde the thyrde. In whose tyme it pleased God to open the eyes of many to se hys truth, geuing them boldenes of herte, to open their mouthes and crye oute agaynste the works of darckenes, as dyd John Wicklyfe who also in those days translated the holye Byble into the Englishe tonge and this writer who in reportynge certayne visions and dreames, that he fayned hym selfe to haue dreamed doth…rebuke the obstynate blynde.Footnote 36

Langland’s work, refracted through Crowley’s Protestant lens, also influences early modern poets such as Edmund Spenser, Michael Drayton, and George Wither.Footnote 37 The mantle of the prophetic poet who hymns imperial power is worn with particular skill by Spenser. Though by no means an extreme Puritan, nor uncritical of the apocalyptic narrative, the imperial view of monarchy remains central to his poetic vision. Throughout his epic The Faerie Queene (1596) his praise of Elizabeth is framed by imperial language and imagery, as is the depiction of Una in Book One.Footnote 38 By contrast, the antichristian figures of Duessa and Archimago undermine this claim to authority. Duessa is depicted as the ‘sole Daughter of an Emperour’ who has ‘the wide West vnder his rule’ and who has set his throne in Rome ‘where Tiberis doth pass’ (Book One, Canto Two, 23).Footnote 39 Her Roman Catholic imperial lineage is a threat to both Una and, by implication, Elizabeth. While we can call Una an allegory of the True Church, Duessa a type of Whore of Babylon, and Archimago a kind of antichrist, Spenser’s figures were also decoded by early modern readers, most notably James VI of Scotland, who objected to the trial of Duessa because it supposedly represented the fate of his mother Mary, Queen of Scots. Allegory and typology, apocalypticism and anti-Catholicism: all intermingle, sometimes uneasily, in Spenser’s great epic.Footnote 40

The assimilation of these Classical and medieval ideas by early modern writers raises the matter of periodisation. Brian Cummings and James Simpson have argued that the very existence of period boundaries between medieval and early modern has a revolutionary ethos: ‘Our very conception of historical periods, divisible into detached segments of time punctuated by liberating convulsions, is itself the product of revolutionary aspiration to neutralize the pathologies of time and start again.’Footnote 41 Yet this is not a move without difficulty: ‘the humanists of the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries conceptualized their own place in history not so much by inventing the modern as by inventing the “medieval”. They created the third term as a conscious polemic.’Footnote 42 Early modern Protestantism offers a polemical redefinition of the ‘medieval’ in order to affirm an invariably partial interpretation of temporal and spiritual history. This ‘liberating convulsion’ is part of a broader Humanist revision of historiographical practice that is achieved by rewriting the relationship between Classical, medieval, and post-Reformation Christian history.Footnote 43 The idea of an imperial ruler who possesses a universal authority over the temporal realm and who will reform the spiritual realm as a prelude to the second coming is a powerful one in medieval and early modern Europe.Footnote 44 After the Reformation in England, the monarch, rather than the Emperor or the Pope, is invested with temporal and spiritual authority. The contingencies of religion and politics often occlude the articulation of the imperial idea in early modern England. But it is an idea – part reality, part fantasy – that does not go away.

The connections between ‘Rome’, ancient and Roman Catholic, are systematically rethought by Reformed commentators on Revelation. We can see this in various historiographical discussions of imperium.Footnote 45 Take the example of the ancient sibylline oracles, referred to by Christian writers throughout the medieval and early modern periods.Footnote 46 As mentioned above, the Cumaean Sybil is Aeneas’ guide to the Underworld in the Aeneid. Virgil also refers to the sibylline oracles in his fourth Eclogue (37 BCE). This text (‘Ultima Cumaei venit iam carminis aetas; / magnus ab integro saeclorum nascitur ordo’, 4. 4–5), his prophecy of a child who sees the coming empire (4. 7), and his reference to a chaste virgin (4: 8) all inspire Christian writers to conflate the return of a pagan golden age with the coming of Christ and the eschatological promise of Revelation.Footnote 47 In De Civitate Dei (c. 410 CE) Saint Augustine argues that the Erythraean Sibyl prophesies the coming of Christ.Footnote 48 He also notes that this Sibyl may have ‘liued in the Troyan war long before Romulus’ and so only Christian writers can fully understand the prophecy.Footnote 49 De Civitate Dei is written at a period when the authority of the Roman Empire is under assault: small wonder that Augustine is interested in prophecies that seemingly predate that Empire. The imperial inflection of Augustine's historiography appeals to the Reformers as much as his theology. If these ancient texts can be used to affirm the reality of the historical Christ, then they can also be folded into a broader narrative that promises the return of Christ and the establishment of the City of God in the face of Rome’s diminishing temporal power. Virgil uses the sibylline prophecies in the pastoral Georgics to promote a cyclical idea of historical desolatio and renovatio that is used in the service of an imperial pax Romana. Augustine translates that sentiment into a desire for temporal desolatio to be overwritten by spiritual renovatio. More than anyone, Augustine is responsible for combining the Classical idea of history as a series of cycles with the belief that history is also moving towards a predetermined end.Footnote 50 This idea of the six ages, as well as Augustine’s sceptical view of Roman power, is important for early modern Protestants. They see themselves as living in a similarly transitional period when authority is shifting in uncertain ways. Empires may rise and fall, but there is a larger providential purpose at work in temporal affairs. Augustinian renovatio also allows Protestants to conflate opposition to the Roman Catholic Church with a prophetic narrative that either predates or opposes the Classical Roman imperium.

In his The Historie of Great Britaine (1611), John Speed argues that the historical moment of ancient Britain’s subjection to Rome’s ‘vniuersall peace’ sees the articulation of a promise. It is shown in the sibyl’s prophecy from Virgil’s fourth Eclogue and book one of the Georgics, from which Speed quotes, that Christ will come to reign over all and the ‘vniuersall subiection’ of Rome will be as nothing.Footnote 51 To oppose the state of Rome is also to undercut Rome’s claims to historical authority. In late sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England, the more sceptical view of Roman history found in Tacitus and Suetonius influences this kind of reading, as do debates about reason of state and the historical formation of national constitutions: Bullinger quotes both of these Roman authors approvingly in his commentary.Footnote 52 These arguments also apply to the inheritor of the Roman imperium, the Roman Catholic Church. Speed reinterprets the ancient prophecies so that the British state and Church can claim an authority that predates their historical emergence in the sixteenth century.Footnote 53 Reformed historiography is grounded in an imperially inflected eschatology. It offers a complete rethinking of ‘Rome’, ancient and Roman Catholic, an imperial legitimation of the Reformed state and monarch, and a promise of the revelation to come.

The most well-known practitioner of this kind of history, and one whose work is drawn on by Speed, is the Lutheran historiographer John Sleidan (Sleidanus).Footnote 54 He develops an important Protestant Humanist version of the translatio imperii, the translation of empire, drawing on the prophetic language and discussion of empire found in the Books of Daniel and the Prophecy of Elias, the works of Virgil, Augustine, and, later, Joachim of Fiore.Footnote 55 Sleidan formulates a model in which ‘the culmination of God’s plan came with the last of the four great world empires, which reached its political pinnacle with Charles V and its religious perfection simultaneously with Luther’.Footnote 56 Spiritual and temporal history is interlinked but Sleidan emphasises the triumph of the former. He also uses the Joachimite idea of the last world emperor.Footnote 57 The political emergence of the Roman Catholic Church is seen in these terms. More radical millenarians such as the Fifth Monarchists would draw on some of these ideas during the English Civil Wars.Footnote 58 To interpret Revelation is to understand the usurpatory history of papal authority: ‘And so is the pope successively become a ruler aboue emperours and kynges, and al christendome vniuersallye.’Footnote 59 The establishment of the Reformation is a key stage in restoring the Church to its primal state of grace, so the argument goes. In freeing people from the thraldom and slavery of Roman Catholicism and establishing a reformed monarchy, the Reformation inaugurates the end of days. Some argue that this restoration will be led by a strong military leader. Throughout the seventeenth century in England, militant Protestantism invests various figures with the imperial hope of renovatio by arms. By contrast, other strands of Protestantism are more gradualist, trusting in the institution of monarchy or, during the Civil Wars, parliament, not putting too much hope in any one figure, and stressing the end of days as a collective judgement. I will return to these ideas later.

In the Protestant exegetical tradition that develops during the sixteenth century, readings of Revelation foreground the intertwined nature of spiritual and temporal history. Alexandra Kess has shown that while Sleidan’s historiographical model is intended to offer an account of ‘salvation history’, it is also flexible enough to allow Protestant writers ‘to consolidate state and religion’.Footnote 60 Important examples of this kind of work include Johann Carion’s Chronicle (1537), Andreas Osiander’s Conjectures of the Ende of the Worlde (1544), Melchior Ambach’s On the End of the World and the Coming of Antichrist (1550), Matthais Flacius Illyricus’ Magdeburg Centuries (1559–1574) and Catalogus testium veritatis (1556) – a writer known to Bale and Foxe – as well as the extremely influential commentary on Revelation written by Heinrich Bullinger (1557) and published in England in 1572.Footnote 61 Here, Bullinger identifies the reign of the eighth-century Carolingian king Pepin as marking ‘The beginninges and preludes of the empire translated’.Footnote 62 Similar arguments are made in the work of Protestant reformers such as John Bale’s equally important commentary The Image of Both Churches (1545) and The Pageant of Popes (1574), his friend John Foxe’s famous Acts and Monuments (multiple editions between 1563 and 1684), where, as one writer put it, ‘the whole glory and power of his [the Pope’s] Babilon, that is drunken with the blood of Saints and Martyrs, [is] vtterly defaced’, and the marginal exegetical notes to the popular Geneva Bible, especially Francis Junius’ commentary on Revelation, which was appended to all copies of this text from 1599.Footnote 63 In fact, the point at which Junius alludes to Virgil’s Georgics in his commentary also marks the point that the Roman Empire is ‘translated into another’ and its authority ‘that before was ciuill became Ecclesiastiall’.Footnote 64 Given the popularity of this Bible in England, and of Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, it is reasonable to suppose that many were familiar with this imperially framed apocalyptic historiography.Footnote 65 Certainly not all Protestants read Revelation in an imperial light. Nor does every exegete interpret this book in relation to temporal political events and figures. But this typological approach is widespread and well known during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

As Arthur Dent writes in his popular commentary on Revelation (Reference Dent1603): ‘we liue in an age wherein the most of the things prophecied in this booke are fulfilled’.Footnote 66 David Norbrook notes that this way of reading ‘challenged the Augustinian distinction between temporal and spiritual spheres, and in so doing it gave renewed importance to the active political life’.Footnote 67 This helps to explain the popularity and political capaciousness of many Protestant commentaries on Revelation. In addition to specific theological and philological exegeses inspired by the studia humanitatis, exegetes are able to relate the broad sweep of spiritual history to the contingent specifics of national and international politics. This includes the rise and fall of the major historical empires, the emergence of the spiritual and temporal authority of the papacy (seen as an ungodly usurpation), the persecution of the saints and martyrs under various wicked temporal rulers, the (re)emergence of the ‘true’ Protestant Church, its ongoing political travails, and its eventual triumph.Footnote 68 As Richard Bauckham notes: ‘Whereas the medievals still located the end of the Roman Empire in the future, the Protestants placed it firmly in the past, holding that the papacy has usurped the powers of the Empire and subjected Europe to itself rather than to the Emperor.’Footnote 69 John Napier’s A Plaine Discouery (Reference Napier1593) offers the reader a historiographical account of the rise and fall of empires that is folded into this providential narrative.Footnote 70 Yet his grand sweep does not preclude specific comments on contemporary politics. Writing for instance of the 1588 Spanish Armada, Napier says: ‘God hath by the tempest of his windes, miraculouslie destroyed the huge and monstrous Antichristian flote, that came from Spaine.’Footnote 71 Although an act of providence, God intervenes to destroy the enemies of the state. Protestant exegesis of Revelation serves eschatology, history, and the state alike.

In The Image of Both Churches Bale reworks Augustine’s concept of the two cities. He draws a contrast between the ‘true Christian Church’ and ‘the proud church of hypocrites, the rose coloured whore, the paramoure of Antichrist, and the sinfull sinagoge of Sathan’, enabling his readers to distinguish between the two Churches and warning them of the affective deceits employed by the Roman Church.Footnote 72 After detailing the ‘persecution, tyrannie, and murther’ of Christians under various Roman emperors, he interprets the opening of the fourth seal and the fourth horseman of the apocalypse in Revelation as the moment when Pope Boniface III (607 CE) usurps imperial temporal powers from the Byzantine Emperor Phocas. Although Protestant commentators differ on precisely when the papacy’s political emergence begins in earnest, Boniface’s reign is often singled out in the commentary tradition. For Bale, Boniface’s actions upset the balance between spiritual and temporal authority. As Popes gain in imperial authority so the people are enslaved: ‘Then were kynges deposed and made monkes, Emperours put downe & paryshe prestes set vp.’Footnote 73 This shift also paves the way for the emergence of ‘Mahometes secte’. According to one popular argument, the Ottoman Empire is covertly working in the service of the papacy’s temporal ambitions.Footnote 74 Bale is sceptical of the Roman Catholic Church. It is an anti-Christian counterfeit, a spiritual front for temporal ambition – here is reason of state writ large. This battle between the true and false Church resounds throughout Protestant polemics. The Whore of Babylon emblematises the latter Church, her cup representing ‘the false religion that she daielye minystreth’.Footnote 75 To drink from her cup is to experience religious and affective disorientation. Like many other Protestant commentators, Bale rejects the Roman Catholic idea that the antichrist is a single figure still to emerge. He argues that there has been a succession of antichrists occupying the chair of St Peter, enemies of the true Church.Footnote 76 The important point is not so much the individual Pope but the ecclesial institution that he represents. As a later commentator puts it, the Church in England is ‘the Church of Christ, and the Church of Rome the Church of Antichrist’.Footnote 77 Only at the second coming can ‘the Romysh Pope and Mahomete’ be defeated and the ‘newe Hierusalem’ established.Footnote 78

These apocalyptic and imperial foundations of the Reformed English Church are crucial.Footnote 79 In the case of Foxe, his martyrological narrative of a true Church (re)emerging from the darkness of persecution gives a prophetic cast to Tertullian’s old adage that ‘sanguis martyrum est semen ecclesiae’.Footnote 80 Foxe’s 1563 Preface to Acts and Monuments addresses Elizabeth as an imperial monarch and heir to Constantine.Footnote 81 She is not simply a national monarch. This is significant because the implication is that, like a Roman Emperor or a Pope, the queen’s spiritual authority transcends national borders. Commentators such as Bale, Foxe, and John Jewel are so interested in the early Church fathers like Tertullian and Origen, the history of the early Church and its martyrs, and in Constantine, because they see parallels between that period and the European Reformation.Footnote 82 They believe that their actions enable the restoration of the ‘Catholic’ Church’s apostolic purity by an imperially authorised monarch.Footnote 83 If done properly in England, theological reformation will then enable the broader European restoration of ‘Christes vniversall Church’.Footnote 84 English apocalyptic historiography commonly sees the Church in both a national and a pan-national context.Footnote 85 It is not a narrowly nationalistic discourse. This view underlies important international political questions that come into focus during the second half Elizabeth’s reign. Should England primarily be concerned with the defence of its own monarchy and Church? Or, as part of the Europe-wide reformed community, does it not also have political obligations beyond its borders?

Clearly the story of the Reformation does not end with Luther or Charles V, and so during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, writing on the end of the world develops sophisticated ways of carrying on. Apocalyptic writing is double edged and adaptable. It allows for prophecies to be made, remade, and reinterpreted, for the end point to be identified and then pushed back, and for interventions to be made in the political realm.Footnote 86 In Frank Kermode’s succinct phrase: ‘Apocalypse can be discomfited without being discredited.’Footnote 87 Protestants can discuss the imminent end while continuing to deal with worldly matters. Such a deferral is also, as John Parker has argued, implicit in Christ’s own promises in the Gospels: ‘The beauty of Christ’s apocalyptic discourse arises … from the way the performance itself represents the nearest instance of the end it proclaims for the simple reason that it can make proclamations only so long as the end has not come.’Footnote 88 Less abstractly, this is another reason why the idea of ‘history’ is so important in early modern Protestantism and why anti-Catholic and apocalyptic writing regularly reflects on contemporary political events.Footnote 89 In anticipation of spiritual transcendence, the focus turns to the imminence of temporal politics. It also explains why the English Protestant commentary tradition encompasses a number of eschatological views, from covenant theology to millenarianism.Footnote 90 Writers from across the religious spectrum read and interpret Revelation and address a wide variety of audiences. The flexibility of this rhetoric and its political usefulness are two of the main reasons why dramatists use this language so often throughout the period.

II

In his preface to Samson Agonistes (1671), John Milton writes, ‘The Apostle Paul himself thought it not unworthy to insert a verse of Euripides into the Text of Holy Scripture, 1 Cor. 15.33; and Paraeus commenting on the Revelation, divides the whole Book as a Tragedy, into Acts distinguished by Heavenly Harpings and Song between.’ Later he notes that the Church father Gregory of Nanzianus ‘thought it not unbeseeming’ to write a tragedy called ‘Christ suffering’.Footnote 91 There are many medieval and early modern plays that explore ideas of renovatio ecclesiae and mundus.Footnote 92 One of the finest surviving high medieval plays, the so-called Ludus de Antichristo (c. 1150), dramatises the arrival, triumph, and eventual defeat of antichrist. ‘Ludus’ can mean a play, a game, and a joke or jest: this connection between apocalypse and laughter is a significant one as we see in Chapter 2. While spiritual history is important to the author of the Ludus, he also allegorically examines the twelfth-century political struggles between Emperor Frederick I Barbarosa, various secular monarchs, and the papacy.Footnote 93 The question of imperial power and who possesses it is at the heart of this play. The dramatic nature of divine judgement at the end of the world (as well as the odd jibe at ecclesiastical failings) is explored with great power in a number of later English medieval plays, such as the York and Chester Cycles, the latter of which includes an antichrist play.Footnote 94 Some biblical characters in the Cycles such as Noah’s wife, Herod, and devils are presented as comic figures, though the laughter that they produce ranges from jest to mockery to fear. In the York Judgement pageant, the elect and the damned are divided by the angels, judged by Christ, and cast into hell. Staging eschatology is central to medieval dramaturgy. It also informs Elizabethan and Jacobean drama, as in the final scenes of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (c. 1588–1592) or Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure (1604). Some Cycles continued to be performed well into the sixteenth century, and a number of early sixteenth century writers draw on these medieval dramatic models as they defend the Reformation on stage.Footnote 95

In Thomas Kirchmeyer’s anti-papal and apocalyptic Latin drama Pammachius (1536–1538) we see morality forms combined with those of Classical comedy.Footnote 96 The play features allegorical abstractions such as Truth alongside historical personations such as Pamachius and the apostles Peter and Paul.Footnote 97 As John Hazel Smith notes, this play is important for a number of English Reformers who see drama as a useful way of proselytising their religion.Footnote 98 Probably the earliest surviving anti-papal play written in English, John Bale’s King Johan (c. 1537–1540), as well as John Foxe’s later Latin Christus Triumphans (1556), are influenced by Kirchmeyer’s play. They also combine allegorical abstractions and historical personifications to explore the connections between temporal and spiritual history. An intriguing-sounding play – now lost – called De Meretrice Babylonica was written in 1548, possibly by King Edward VI. One text that almost certainly influences Foxe is Bernadino Ochino’s Edwardian dramatic dialogue A Tragoedie or Dialogue of the vniuste vsurped primacie of the Bishop of Rome (1549).Footnote 99 Both Pammachius and Christus Triumphans were performed at Cambridge, the first in 1545, the second in 1562–1563.Footnote 100 These texts can be categorised generically as comoedia apocalyptica, a phrase found in the dedicatory material and Prologue to Foxe’s play. Comoedia apocalyptica fuses the spiritual and the temporal, national and international concerns, through drama. Combining the Classical genres of Old and New Comedy with Christian allegory and typology, it invites readers to decode the play’s political aims.

In Foxe’s Prologue, the poet asks for ‘silence of you, new spectators, while he brings onto the stage something new for you to see: to be precise, we bring you Christ Triumphant’.Footnote 101 The play dramatises the ‘divine comedy’ of creation, fall, rebirth, and salvation, allowing for a generic intermingling of tragedy and comedy. As in Piers Plowman, Ecclesia is oppressed by the forces of antichrist. Satan promises to seduce men with ‘all manner of life’s pleasure, the Circean cup as it were’, to offer ‘painted glories, worldly empires, and distinguishing titles’, and to use Pseudamnus (the Pope) as his vehicle, enjoining him to bribe his way to the pontificate.Footnote 102 Foxe’s play may not be funny in the way that Chaucer’s The Miller’s Tale or Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream are. But it does display a bawdy, satirical humour that is reminiscent of the medieval Cycles and that anticipates Jonson. For instance, the fall of Pseudamnus and Pornapolis (the Whore of Babylon) is depicted through the apodioxis found in earthy Lutheran polemic: ‘Men won’t be led by the nose much longer’, Pseudamnus is told; ‘they’re farting at your orders and shitting on your bulls. Your keys are worthless, but your thunder and triple crown are universally scorned, for they say Christ himself lives and that a body which sustains two heads is a monstrosity … they firmly believe that you are the Antichrist.’Footnote 103 Africus and Europa argue for a war to restore the true Ecclesia, but she demurs: ‘Except by the coming of Christ, this beast cannot be destroyed.’Footnote 104 It is notable that Ecclesia plays down the temporal militant argument, preferring instead the spiritual war of the second coming. For Foxe drama can advance an imperial apocalyptic interpretation of history, even if only as a mirror of the divine revelation promised at the end of the world.Footnote 105 At the play’s conclusion, Ecclesia dresses for a wedding, but the arrival of the bridegroom is not staged. The drama ends instead with an Epithalamion sung by the company calling on Christ to come: ‘Too long are the ages you have been away from the earth, oh saviour, while we your people groaned, mangled by wolves.’ Only then, ‘Babylon will fall, and the exalted power of kings: Christ alone will have power through all the world.’Footnote 106 This could be a radical conclusion: all temporal authority will eventually be as nothing. Yet it also points to the limitations of the comoedia apcalyptica: ‘The Poet has shown what he could’ yet these can only ever be ‘marvellous preludes’.Footnote 107 Drama can promise the apocalypse, it can prepare the spectators for the second coming. But it cannot ultimately stage the End. In the absence of the Messiah, we are left with the compromises and contingencies of worldly politics.

The religious structure and dramatic rhetoric found in Christus Triumphans and, more importantly, repeated in commentaries, sermons, and numerous other writings influences the writing of drama. The Humanist practice of imitatio helps to disseminate key ideas: the translatio imperii and studii, opposition to Roman Catholicism, and the relationship between temporal and spiritual history are all exemplary and commonplace themes in Protestantism whose centrality is heightened by exegetical repetition.Footnote 108 Whatever their personal faith, post-Reformation dramatists clearly understood dominant Protestant methods of reading these themes. Other sixteenth-century plays and interludes that can be considered in this light include Lewis Wager’s The Life and Repentance of Mary Magdalene (c. 1550–1562), William Wager’s The Longer Thou Livest the More Fool Thou Art (c. 1559–1568) and Enough Is as Good as a Feast (c. 1559–1570), lost texts such as Papists (1559) (perhaps performed at court) and Mock Mass (c. 1563–1565) (perhaps performed at Cambridge), texts such as King Darius (c. 1565), Henry Cheke’s Free Will (c. 1565–1572), New Custom (c. 1571), Nathaniel Woodes’ The Conflict of Conscience (c. 1570–1581), and the lost Pope Joan (c. 1580–1592). In some of these dramas the characters are solely allegorical. Wager’s The Longest Thou Livest contains abstractions such as Piety or Ignorance who invite audiences to perform a kind of religious decoding, encouraging them to reflect on Protestant doctrine. Many other plays and interludes follow Bale and Foxe in combining allegorical abstractions with historical characters. In New Custom the title page informs the reader that ‘Peruerse Doctrine’ is in fact ‘an olde Popish Priest’, and in Woodes’ play we see Philologus (lit. Learned Man) alongside his sons – the realistically named Gisbertus and Paphinitius – confronting abstractions such as Horror and Theologus.Footnote 109

In the last two decades of the sixteenth century, dramatists develop the relationship between allegorical abstraction and historical personation: the former mode does not disappear but the latter comes to dominate representation in the public theatres.Footnote 110 While it would be tempting to connect this shift to the general Reformist suspicion of allegory and a preference for a typological interpretation that is more obviously grounded in history, the first waves of reformist drama show us that the reality is more complex. As John Pendergast puts it: ‘Although many Reformation exegetes were unwilling to acknowledge the prior nature of allegory to typology, and the resulting ontological dependence of typology on allegory, many of the same exegetes made room at least rhetorically for allegory.’Footnote 111 Typological reading, however historically situated it is, can never completely escape the pull of allegory. In the Reformed tradition apocalyptic history is, as we have seen, susceptible to a spiritual, even allegorical reading. The implications of this mode of reading have been underappreciated by scholars of early modern drama. An important play in this respect is Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus (A Text c. 1588–1592). It draws on Woodes’ A Conflict of Conscience and includes apocalyptic and anti-Catholic imagery. More than in Woodes’ play Faustus deals with the effects of doctrine on individuals who occupy a historically identifiable time and place. Think here of Faustus’ debates with Charles V or the famous (mis)reading of Scripture in Faustus’ first soliloquy. Whether done wilfully or not, his exegesis is closely bound up with contemporary Calvinist debates about election, reprobation, and predestination.Footnote 112 And yet the play does not completely forgo the allegorical implications of Faustus’ fate. Through abstractions such as the Seven Deadly Sins and the Good and Evil Angels, audiences are reminded that the allegorical and the typological are related modes of reading. Another important example is Kyd’s popular The Spanish Tragedy where a Classical abstraction (Revenge) and a Ghost (of Don Andrea) are embroiled in the political affairs of Spain and Portugal. The temporal machinations of Hieronimo, Lorenzo, Bel-Imperia, and Horatio are read through the dramaturgical frame occupied by Revenge and the Ghost, reminding the audience that politics also has a spiritual significance.

The fact that both of these plays continue to be performed regularly throughout the seventeenth century is important. They keep a form of dramaturgy that has direct roots in the reformist theatrical and exegetical tradition in the public consciousness. They also help us to see why allegory retains a theatrical hold throughout the century. Most obviously in allegorical plays written at moments of political tension such as Dekker’s The Whore of Babylon (1605/6), Middleton’s A Game at Chess (1624), and William Bedloe’s The Excommunicated Priest (1679), there is a self-conscious return to older modes of reformist theatre. However, we also see allegorical figures appear intermittently in a number of other plays (such as Time at the beginning of act IV of Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale), in academic drama, in City Pageants, and in the Court Masque. Allegory is the exception rather than the rule in seventeenth-century theatre. Yet even in a Protestant interpretative culture that prefers the typological mode, the use of allegory on stage reminds audiences that typological readings are themselves a form of allegory, one that invests imaginative or past events with present meaning. Even in the more historically situated drama of the seventeenth century, politics can have a temporal and spiritual significance.

Of course the broader cultural assimilation of apocalyptic and anti-Catholic discourse in the seventeenth century does not preclude scepticism towards, or even mockery of, that language. Some of Shakespeare’s early characters use anti-Catholic terms: King John’s tirades against the papal legate Pandolf are a case in point, as are Gloucester’s threats to the Bishop of Winchester in 1 Henry VI (c. 1591). Hotspur in 1 Henry IV (c. 1596) is a good example of a figure who uses religious and militaristic rhetoric but whose belligerence also leads to his downfall.Footnote 113 In his later plays, Shakespeare presents these languages in a more detached, sceptical way. In Antony and Cleopatra (c. 1606) he explores how the Roman imperium problematically foreshadows the Christian imperium through numerous references to Revelation. And in Macbeth (c. 1606) – another play full of references to Revelation – he sceptically interrogates the Stuart evocation of the ‘imperial theme’ (I.iii.128). In Francis Beaumont’s The Knight of the Burning Pestle (1607), the language of the Spenserian would-be-knight Rafe is used to parody the inflated rhetoric of militant Protestantism, while also drawing attention to the potential for this group to mobilise independently of the state.Footnote 114 As mentioned, Ben Jonson has little time for hotter forms of apocalypticism and anti-Catholic language. He regularly mocks the Puritans, most famously in The Alchemist (1610) when Ananias criticises Surly for his ‘profane / Lewd, superstitious, and idolatrous breeches’ and concludes:

For more extreme Puritans, the expression of anti-popery is a sign of election: this is precisely the logic that Jonson satirises here.Footnote 116 In Bartholomew Fair (1614), Zeal-of-the-Land-Busy’s thunderous uses of apocalyptic and anti-Catholic language are undermined because of his hypocrisy, as well as his inability to beat a puppet in debate.Footnote 117 And in Volpone (1606) and The Alchemist Jonson derides the Hebraist and biblical commentator Hugh Broughton for his obscure style and apocalyptic enthusiasms. Despite the cultural centrality of apocalypticism and anti-popery, these ideas and their adherents can be exposed to Juvenalian scorn and Montaignean scepticism onstage.Footnote 118

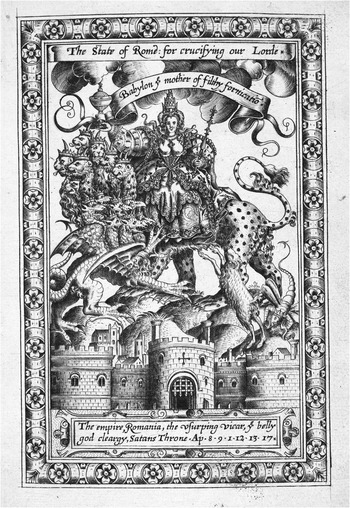

Anti-Catholic and apocalyptic images are disseminated in a popular print culture underpinned by a providential view of the world.Footnote 119 Despite Protestant iconophobia, images of papal corruption or the Whore of Babylon are found throughout contemporary visual culture. They reinforce popular anti-Catholic sentiment, offering people a way of understanding their country’s place in the world and defending their Church and state. It is unlikely that dramatists were unaware of this polemical visual imagery. One drama apparently indebted to contemporary visual depictions is Thomas Dekker’s The Whore of Babylon. Written in the aftermath of the Gunpowder Plot, the play was not a success on stage, perhaps because its apocalyptic reading of recent European history is overly didactic, owing more to the commentary tradition and allegorical poetry than to the demands of the theatre.Footnote 120 Exploiting the political situation in 1605/6, Dekker represents his Whore verbally and visually. At the start of the play, the Empress of Babylon is shown as a spiritual and temporal ruler:

Empresse of Babylon: her canopie supported by four Cardinals: two persons in Pontificall roabes on either hand, the one bearing a sword, the other the keies: before her three Kings crowned, behinde her Friers, &c.Footnote 121

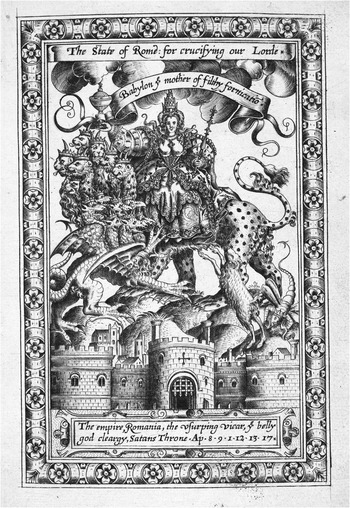

This tableau depicting imperial Roman Catholic authority over spiritual and temporal rulers is similar to contemporary visual depictions.Footnote 122 Albrecht Dürer’s influential Apocalypse of 1498 shows the Whore of Babylon seducing kings and merchants. In early modern England similar imagery of the Whore is found in printed books, engravings, woodcuts, and broadsides.Footnote 123 A striking example is found in Hugh Broughton’s A Concent of Scripture (Reference Broughton1590) (Figure 1). Similar to contemporary Dutch and Italian depictions of prostitutes, we see the Whore with her breasts bared. She holds the cup of fornication in her right hand and the sceptre of power in her left as she tramples over Babylon. Dekker’s tableau evokes this kind of commonplace visual image. It also creates a problem for the viewer. As noted, reformed culture is generally wary of the image. Visual or theatrical representations of religious corruption must tread a fine line between iconophobia and iconophilia. Depicting the Whore in the public theatre reminds the audience of their common foe. Yet her presence, even as a negative representation, is dangerous: there is always the potential of seduction to the ‘false’ religion.Footnote 124

Figure 1 Hugh Broughton, A Concent of Scripture (London: Richard Watkins for Gabriell Simson and William White, Reference Broughton1590).

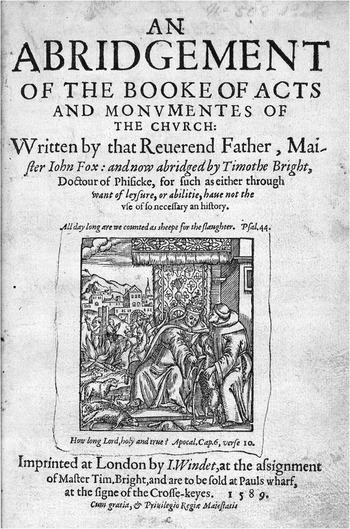

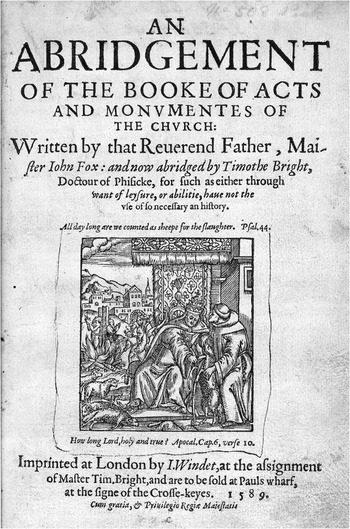

More subtly drawn politique representations such as Pandolf in Shakespeare’s King John, Ferdinand and the Cardinal in John Webster’s The Duchess of Malfi (1614), or Ignatius Loyola in Thomas Middleton’s A Game at Chess keep the image of the manipulative Roman Catholic in the public consciousness. They may also evoke visual polemics.Footnote 125 In The Duchess of Malfi images of wolfishness abound. Ferdinand suffers from lycanthropy and calls himself a ‘sheep-biter’ (Vi.ii.45), an image that taps into the polemical association of Roman Catholics as wolfish persecutors of sheep/martyrs: we may recall here Foxe’s depiction of Christ’s people ‘mangled by wolves’ in Christus Triumphans. Earlier, the Duchess appeals to heaven to ‘cease crowning martyrs / To punish them’ (IV.i.105).Footnote 126 In the image (Figure 2) from the title page of an abridgement of John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments, the Pope is shown sacrificing sheep while martyrs burn in the background. Webster’s verbal allusions draw their authority from such allegorical visual representations. Polemical and dramatic imagery occupy a common ground, allowing theatrical audiences to encounter the enemy of the state.

Figure 2 An Abridgement of the Booke of Acts and Monumentes of the Church … (London: SN, 1589), title page.

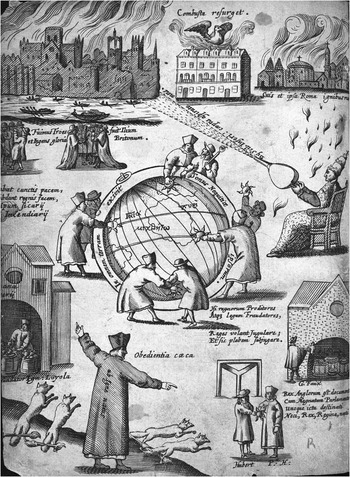

Like Macbeth, Barnabe Barnes’ The Devil’s Charter makes much of King James’ interest in necromancy. As we saw in the previous chapter, the play starts with the Pope’s pact with the Devil. Later the Pope conjures a king from hell who appears wearing an imperial crown, and in the final scene the Devil returns and, à la Faustus, drags Alexander off to hell. The association of the Pope with the Devil is another visual commonplace that informs such polemical dramatic representations.Footnote 127 For instance, in a number of Pope-burning processions held during the Popish Plot, a devil is shown whispering to the Pontiff.Footnote 128 These events, like the Gunpowder Plot ceremonies held annually on 5 November, memorialise popish atrocities past and present through a kind of recursive cultural imitatio. Often accompanied by violence, these rituals shore up the powerful national myth of popish subversion and Protestant perseverance. This is vividly depicted in one image (Figure 3), printed after the Great Fire of London in 1666, which shows the Jesuits, aided by the Pope, indulging in pyrotechnic subversion of the state. The insistent repetition of such images in visual and verbal culture shows us just how much Protestantism needs the papal scapegoat as a form of representation. As René Girard has shown, the scapegoat possesses a ‘harmful omnipotence’.Footnote 129 Anti-papal iconography, burnings, processions, and plays offer a temporary outlet for laughter, mockery, anger, and violence. Yet the threat remains.Footnote 130 The anti-Catholic scapegoat haunts the seventeenth-century cultural imagination.

Figure 3 Pyrotechnica Loyolana, Ignatian fire-works … (London: Printed for G.E., 1667), title page.

The performance of these symbolic rituals is a marker of national self-assertion and anxiety. Important work in the so-called new British history has shown how the political history of England in this period is intertwined with its major European neighbours, especially Spain, France, and Holland.Footnote 131 In the words of John Morrill, ‘one of the unfulfilled dimensions of the new British history is to examine the way different parts of Britain draw differentially on parts of Europe’.Footnote 132 Drama often mediates that relationship. We might think here of John Fletcher and Philip Massinger’s contentious play on the Arminian controversy in Holland, Sir John van Olden Barnavelt (1619), or Middleton’s scathing critique of international Roman Catholicism, A Game at Chess, both of which draw on polemics with a national and European focus. Spain and France are Roman Catholic countries, and the Protestant parts of the Netherlands finds itself under attack at various points from these two powers throughout the period. This helps to fuel English fears about overt or covert popish infiltration. Accusations of popish plots often go hand in hand with a critique of Spain or France’s political ambitions and a defence of England’s place within the Protestant international. The idea of a popish plot is first articulated in Elizabethan England in the aftermath of Pius V’s Bull of excommunication against the Queen, Regnans in Excelsis (1570).Footnote 133 We see it emerge again at points throughout the seventeenth century, for instance after the Gunpowder Plot, during the marriage negotiations for James I’s children, with the emergence of Arminianism during the 1620s and ’30s, during the collapse of Charles I’s personal rule, before and after the Irish Rebellion of 1641, after the Great Fire of London, and most notoriously during the Popish Plot.

This recurring perception that the Protestant state is susceptible to Roman Catholic assault is a mark of political vulnerability. This can be explained by reference to Jonathan Scott’s important work on anti-Catholicism:

What one notices first about the seventeenth-century English fear of popery are its range and power: it spanned the century; it crossed all social boundaries; as a solvent of political loyalties it had no rivals. What one should notice next is that it is inexplicable in a purely national context. Within England in the seventeenth century catholics made up a tiny and declining proportion of the population: protestantism was secure, and was becoming more so. It was in Europe that the opposite was the case. Between 1590 and 1690 the geographical reach of protestantism shrank from one-half to one-fifth of the land area of the continent. The seventeenth century in Europe was the century of the victories of the counter-reformation, spearheaded by Spain in the first half of the century and France in the second. It was the century in which protestantism had to fight for its survival. This was the context for fear of popery in England, which found itself thrust into the front line against the European counter-reformation advance.Footnote 134

Understood in this context, the fear of popish plots makes sense. At such moments, bellicose self-assertion and defensive insecurity jostle for preeminence. Certainly, this did not stop people from reading Roman Catholic books, conversing with their recusant neighbours, or, in the case of a number of aristocrats, being influenced by developments in Counter-Reformation and Baroque art, and in the more ephemeral spheres of fashion and manners. The Grand Tour exposed many individuals of means to Roman Catholic culture.Footnote 135 Moreover the expression of a more irenic attitude towards Roman Catholicism can be glimpsed haltingly at points during the period. Seventeenth-century anti-Catholicism is not a consistent discourse and this admixture is part of the story as other scholars have shown.Footnote 136 Yet when anti-Catholic rhetoric takes on a more embattled tone and binary structure, it reveals the fault lines that run through the Protestant state.Footnote 137

How is that state to be best defended? Some argue for an insular, isolationist approach. Some argue for a limited engagement with their European neighbours mainly through trade. For those on the militant wing of opinion, Protestantism has to be asserted with martial vigour at home and abroad. The relationship between the Stuart monarchs and militant Protestant ideology is rarely a comfortable one. Many were concerned for example, by James VI and I’s plans during the early years of his reign for a pan-European ecumenical Church council with the Pope at its head: martial opposition to Roman Catholicism is preferable.Footnote 138 Charles I and his court are regularly criticised for perceived popish leanings and arbitrary rule, as is the regime of his son Charles II. The concern expressed at various points throughout the century that the Stuart monarchs are unwilling or unable to uphold the Protestant religion, or to guarantee the liberty of subjects, finds its mirror image in the claim that the Pope is a universal monarch who should be opposed. In the words of one text published in 1621: ‘the Pope commandeth Kings, curseth them, and killeth them; to that end he hath his triple Crowne, and claymeth soueraignty over the Church, and commandeth the treasure of the World: whereas Peter had neither gold, nor siluer’.Footnote 139 The Roman Church has fallen from its apostolic purity and is engaged in anti-Christian subversion. Only those of the militant Protestant persuasion fully realise the implications of this fact and are primed to put it right through force of arms, so the argument goes. Order can be guaranteed and liberty upheld only when kings command Popes. Or if, as it was suggested by some radicals during the Civil Wars, the king cannot uphold liberties because his rule is too close to popish tyranny, then he should be resisted.

Certainly, this kind of argument has more of the whiff of fantasy about it, one that encapsulates the paranoia of the conspiracy theorist throughout the ages. Scott’s claim that Britain found itself ‘thrust into the front line against the European counter-reformation advance’ overstates the degree to which the state was ever likely to be able to maintain this line. As Jason White has persuasively argued in his recent study of Jacobean militant Protestantism: ‘That there was a serious disjuncture between what many thought Britain should be – a Protestant and Continental power – and what it was in reality – formidable enough to avoid invasion but prone to neutrality and failure – created serious tensions between the early Stuart kings and a significant portion of the body politic.’Footnote 140 This is a key point. As we will see throughout this book, the militant internationalist perspective defines debate throughout the seventeenth century, even when it is a fantasy position. Moreover, militant rhetoric addresses some of the period’s most intractable political problems, especially the relationship between imperial monarchical authority and military power. Militant Protestantism returns again and again to ideas of imperial renovatio through force of arms. Yet many polemicists also know that the Stuart claim to imperial monarchy is largely ideological, not material. An Empire is fuelled by the spoils of military conflict abroad: on this front, the Stuarts fall short. Militant calls to arms are made for many reasons, but one repeated theme is that a true imperial monarchy can be established only through the defeat of international Roman Catholicism. In examining how this and related problems are explored in the theatre, this book explores the sheer variety of opinion to which drama is capable of giving voice.

III

It is no longer necessary to offer exhaustive defences of the claim that early modern drama is deeply implicated in the religious and political debates of the period. Scholarship over the past thirty-five years has definitively proved the case. Yet there is still more that can be said. Richard Helgerson pointed out a number of years ago that ‘Apocalyptic was radically inclusive. Ordinary craftsmen and labourers, even women, had a significant part in it.’Footnote 141 We can make a similar argument about anti-Catholicism. In some hands, these religious languages can be fundamentally conservative, a polemical reinstatement of the status quo; modern criticism is good at identifying this phenomenon. Yet in other hands, this rhetoric can also be surprisingly flexible and fleet, a way of blurring the boundaries between competing ideologies; criticism is less good at explaining this fact.

As Helgerson implies, this language may also pose a subversive threat to established power and privilege. In a passage in his sermon on 2 Thessalonians 2:3, the Oxford academic John Rainoldes draws a contrast between the violent establishment of temporal rule and the papacy:

Wherefore as Princes when they haue subdued any people, to shew that they are their gouenours, are wont to change their customes, alter their state, abrogate their ancient laws & and appoint new at their pleasure: so the Pope herein sheweth himself as God, in that occupying the place in Gods church he taketh vpon him to establish and make new and strange ordinances at his good pleasureFootnote 142

This is an argument by analogy, but it also shows that early modern monarchies of whatever religious stripe are often uncomfortable mirror images of each other. Though Rainoldes is no firebrand, there is a radical core to apocalypticism that is subversive of political authority and that, at various times throughout the century, is accessed by a number of people. In a society where temporal politics is organised hierarchically, and where for most subjects individual liberty is invariably circumscribed, the ‘promis’d end’ (V.iii.262), as Kent puts it in King Lear, is ultimately the promise of a transcendent new order that will reduce those temporal hierarchies to nothing. Some make more of this promise than others. Yet as Martin Luther pointed out at the inception of the Reformation, Christian liberty is a fundamentally nonhierarchical and horizontal thing, a gift that ushers in the levelling inheritance of grace.Footnote 143 At the end of the world, the only true liberty is that extended to those who will be saved: ‘the happie renewing of the whole world shalbe, when Christ the redeemer of the electe shall once appeare’.Footnote 144 Today we might view such thinking as a spiritual reinstatement of hierarchy, the very antithesis of what should properly be called freedom. Are the damned not like those temporal slaves who are deprived of their liberty? As the texts examined in this book make clear, this is not how most of our early modern forebears saw the matter. True liberty and freedom is a spiritual inheritance and will come only when the false church is defeated and when Christ comes to judge the quick and the dead. If such thinking paradoxically enables the halting emergence of more recognisably modern understandings of liberty, then our broader task here is to try to understand why it is that during the seventeenth century, the dramatic language of apocalypticism and anti-Catholicism can inspire both stasis and revolution alike.