Sacred Fictions of Medieval France

Sacred Fictions of Medieval France Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Sacred Romances: Genealogy, Lineage and Cyclicity

- 2 Sacred Epic and the Diffusion of Anti-Jewish Sentiment

- 3 Sacred Allegory and Meditation

- 4 Sacred Histories: the Chronicles of Jean d’Outremeuse and Jean Mansel

- 5 Sacred Imaginations: Lives of Christ and the Virgin in Texts of A ffective Devotion

- Epilogue: Lives and Afterlives

- Appendix: Lists of Manuscripts by Chapter

- Bibliography

- Index

5 - Sacred Imaginations: Lives of Christ and the Virgin in Texts of A ffective Devotion

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 June 2021

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1 Sacred Romances: Genealogy, Lineage and Cyclicity

- 2 Sacred Epic and the Diffusion of Anti-Jewish Sentiment

- 3 Sacred Allegory and Meditation

- 4 Sacred Histories: the Chronicles of Jean d’Outremeuse and Jean Mansel

- 5 Sacred Imaginations: Lives of Christ and the Virgin in Texts of A ffective Devotion

- Epilogue: Lives and Afterlives

- Appendix: Lists of Manuscripts by Chapter

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

Et … pour plusgrande impression ainsi que on peut debonnairement croire que elles sont advenues selon aucunes representacions ymaginees lesqueles mon courage a prinses et apperceues en diverses manieres.

(Brussels, KBR, IV. 2547, fol. 8r)[And, to make a greater impression, as one can meekly believe that they happened according to some imagined representations which my heart has taken and chosen in various ways.]

One of the distinctive features of late medieval society was the intensity of religious feeling among the laity, particularly ‘the literate, the leisured and in urban populations’, who hungered for a form of spirituality that went deeper than the minimal observances required by the Church. One manifestation of this desire was the development and spread of ‘Books of Hours’, which from the middle years of the thirteenth century gave lay people access to a form of spirituality that had long been restricted to the cloister. Composed of elements borrowed from the monastic prayer-book called the ‘Breviary’, the Book of Hours presented an abridged form of monastic liturgical prayer suitable for lay people. In the Office of the Virgin – the most important element of a Book of Hours – the devotional material (Psalms, Lessons, and Hymns) was divided into seven sections, each assigned to a different liturgical hour of the day (Matins, Prime, Terce, etc.). The periodic interruption of the ordinary tasks of daily life to read or recite these texts was a deliberate attempt to sanctify secular time. Nevertheless, the essence of this type of prayer was not the mechanical repetition of the same words each day, but the effort enjoined on the pious reader to use the texts as a basis for meditation, particularly on the events of Christ's life, either his childhood or his Passion. Since the texts of the Office of the Virgin do not relate these episodes, the reader was obliged, often with the aid of an accompanying illustration, to create the scene in his or her mind through a process of imagination.

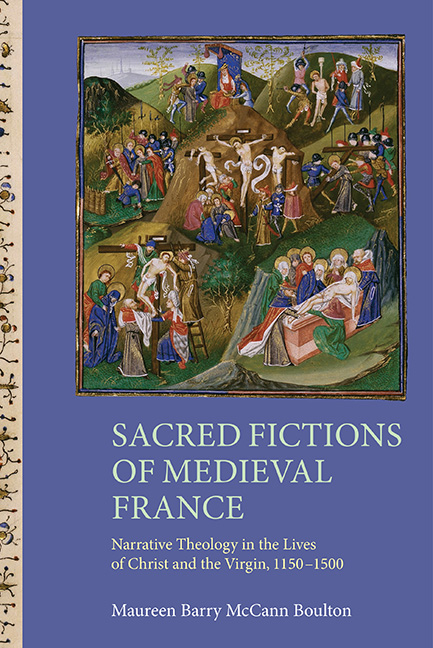

In illustrated Books of Hours, the succession of miniatures accompanying each section guided the content of that meditation. They frequently included representations of the life of the Virgin and the childhood of Jesus, often derived from the types of work examined in the previous chapters of this book, along with scenes from the Passion in the Office of the Cross, augmented by material from the illustrative traditions of similar sources.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Sacred Fictions of Medieval FranceNarrative Theology in the Lives of Christ and the Virgin, 1150–1500, pp. 229 - 284Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2015