Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Foreword to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on the Essays

- The “I” of the camera

- 1 Hollywood Reconsidered: Reflections on the Classical American Cinema

- 2 D. W. Griffith and the Birth of the Movies

- 3 Judith of Bethulia

- 4 True Heart Griffith

- 5 The Ending of City Lights

- 6 The Goddess: Reflections on Melodrama East and West

- 7 Red Dust: The Erotic Screen Image

- 8 Virtue and Villainy in the Face of the Camera

- 9 Pathos and Transfiguration in the Face of the Camera: A Reading of Stella Dallas

- 10 Viewing the World in Black and White: Race and the Melodrama of the Unknown Woman

- 11 Howard Hawks and Bringing Up Baby

- 12 The Filmmaker in the Film: Octave and the Rules of Renoir's Game

- 13 Stagecoach and the Quest for Selfhood

- 14 To Have and Have Not Adapted a Film from a Novel

- 15 Hollywood and the Rise of Suburbia

- 16 Nobody's Perfect: Billy Wilder and the Postwar American Cinema

- 17 The River

- 18 Vertigo: The Unknown Woman in Hitchcock

- 19 North by Northwest: Hitchcock's Monument to the Hitchcock Film

- 20 The Villain in Hitchcock: “Does He Look Like a ‘Wrong One’ to You?”

- 21 Thoughts on Hitchcock's Authorship

- 22 Eternal Véritées: Cinema-Vérité and Classical Cinema

- 23 Visconti's Death in Venice

- 24 Alfred Guzzetti's Family Portrait Sittings

- 25 The Taste for Beauty: Eric Rohmer's Writings on Film

- 26 Tale of Winter: Philosophical Thought in the Films of Eric Rohmer

- 27 The “New Latin American Cinema”

- 28 Violence and Film

- 29 What Is American about American Film Study?

- Index

16 - Nobody's Perfect: Billy Wilder and the Postwar American Cinema

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 June 2012

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Foreword to the Second Edition

- Preface to the First Edition

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on the Essays

- The “I” of the camera

- 1 Hollywood Reconsidered: Reflections on the Classical American Cinema

- 2 D. W. Griffith and the Birth of the Movies

- 3 Judith of Bethulia

- 4 True Heart Griffith

- 5 The Ending of City Lights

- 6 The Goddess: Reflections on Melodrama East and West

- 7 Red Dust: The Erotic Screen Image

- 8 Virtue and Villainy in the Face of the Camera

- 9 Pathos and Transfiguration in the Face of the Camera: A Reading of Stella Dallas

- 10 Viewing the World in Black and White: Race and the Melodrama of the Unknown Woman

- 11 Howard Hawks and Bringing Up Baby

- 12 The Filmmaker in the Film: Octave and the Rules of Renoir's Game

- 13 Stagecoach and the Quest for Selfhood

- 14 To Have and Have Not Adapted a Film from a Novel

- 15 Hollywood and the Rise of Suburbia

- 16 Nobody's Perfect: Billy Wilder and the Postwar American Cinema

- 17 The River

- 18 Vertigo: The Unknown Woman in Hitchcock

- 19 North by Northwest: Hitchcock's Monument to the Hitchcock Film

- 20 The Villain in Hitchcock: “Does He Look Like a ‘Wrong One’ to You?”

- 21 Thoughts on Hitchcock's Authorship

- 22 Eternal Véritées: Cinema-Vérité and Classical Cinema

- 23 Visconti's Death in Venice

- 24 Alfred Guzzetti's Family Portrait Sittings

- 25 The Taste for Beauty: Eric Rohmer's Writings on Film

- 26 Tale of Winter: Philosophical Thought in the Films of Eric Rohmer

- 27 The “New Latin American Cinema”

- 28 Violence and Film

- 29 What Is American about American Film Study?

- Index

Summary

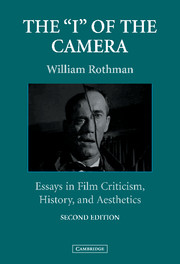

Film scholars often attribute differences between pre–World War I and post–World War II Hollywood films to the influx of exiles from strife-torn Europe. Film noir, in particular, is said to reflect themes, character types (the “femme fatale”), and stylistic devices (oppressive shadows) associated with the “expressionist” cinema of Weimar Germany. Billy Wilder, an East European Jew who came to America in the early 1930s and whose first noteworthy directorial effort was Double Indemnity, a prototypical film noir, is a critical case in assessing the European influence on post–WWII Hollywood.

The matter is complicated, however, for at least three reasons. First, because “expressionist” German silent cinema had already had a profound impact on Hollywood movies of the 1930s, above all in the impact of F. W. Murnau's Sunrise (1927) on directors like Capra, Hawks, von Sternberg, Cukor, and Ford. Sunrise was the ultimate achievement of the German silent cinema. It was also an American film, however. Made in America for the Fox studio, Sunrise uncannily anticipated the contours of the genres that were soon to crystallize in Hollywood – in particular, the genre Stanley Cavell calls the comedy of remarriage [It Happened One Night (1934), The Philadelphia Story (1941), et al.] and, a few years later, film noir. Second, because “expressionism” is at most a superficial feature of Wilder's films, which align themselves primarily with the comedies of Ernst Lubitsch, whose American films reflect a very different aspect of German silent cinema. There is a third reason as well.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The 'I' of the CameraEssays in Film Criticism, History, and Aesthetics, pp. 177 - 205Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2003