More than ten years ago Sophie Quinn-Judge observed, “We can follow month by month Robert McNamara’s or Lyndon B. Johnson’s agonizing over their choices, but still have to speculate about much that occurred in Hanoi.”Footnote 1 Since then, our understanding of domestic politics in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN) has improved due to the better accessibility of sources inside and outside Vietnam and the resulting studies by Lien-Hang T. Nguyen, Merle Pribbenow, Pierre Asselin, and others.Footnote 2 However, in comparison to our knowledge about decision-making in the US administration during the war, information about the inner workings of the socialist state in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam is still limited.

Factional Infighting and the Campaign against “Modern Revisionism”

The year 1964 marked a watershed in the history of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam. It marked the victory of those in Hanoi who advocated a direct military intervention in the South in order to topple the government in Saigon, establish a communist-controlled coalition government, and unify the whole country under the Democratic Republic of Vietnam before the United States intervened militarily. Others, such as General Võ Nguyên Giáp, were afraid that by sending North Vietnamese troops to the South Hanoi might itself provoke direct American intervention. They therefore favored a more cautious approach, a protracted guerrilla people’s war. At the same time, they worried that the militant line proposed by the party leadership under First Secretary Lê Duẩn might alienate the Soviets.

The rift between these two factions came to the fore during the 9th Plenum of the Central Committee at the end of 1963, which an East German journalist in Hanoi called “the most massive confirmation of disagreement in the [Vietnam Workers’] party.”Footnote 3 Lê Duẩn managed to prevail: at the end of the plenum the Central Committee issued a concluding statement that became known as Resolution 9 and fully supported his aggressive line. It called for an escalation of the insurgency in the South and “gave DRVN decision-makers a blank check to wage war in the South.”Footnote 4 In addition, the resolution attacked “revisionists” within the socialist bloc who still propagated the theory of peaceful coexistence and were thus undermining the world revolution. Whereas these attacks still criticized “revisionists” in general, later in February 1964 the Vietnamese Workers’ Party (VWP, Lao Động Party) launched a campaign against “modern revisionism” that specifically targeted moderates within the party who had expressed reservations about the militant course of the Lê Duẩn faction.

It was Lê Duẩn’s closest ally Lê Đức Thọ, the head of the Party Organization Committee, who proclaimed the start of the campaign in a series of articles in the party newspaper Nhân Dân (The People). He called for absolute party discipline and demanded that all cadres should be fully committed to the new aggressive line. As a direct reaction to the division within the party that had come to light during the 9th Plenum, Lê Đức Thọ denounced “factionalist and divisive activities” that had undermined the unity of the VWP.Footnote 5 This was aimed at party members such as Hoàng Minh Chính, head of the Institute of Philosophy, whose proposal for the plenum had endorsed the principles of peaceful coexistence and economic cooperation, and all those who had supported his ideas during the meeting. Next to Hoàng Minh Chính, Lê Liêm, Deputy Minister of Culture, Dương Bạch Mai, Vice President of the Vietnamese–Soviet Friendship Association, Bùi Công Trừng, Deputy Chairman of the National Commission of Science and Technology, and Ung Vӑn Khiêm, former foreign minister, ranked first among those eyed by the DRV security apparatus. In addition, the Ministry of Public Security and the army’s Security Service (Bảo vệ) targeted all other intellectuals, civil servants, artists, and journalists who were suspected of not fully supporting the new militant line of the party leadership.

In the following months, the campaign attacked institutions that had been identified as “bulwarks of modern revisionism”: the National Commission of Science and Technology, the party’s publishing house Sự Thật (The Truth) and its director Minh Tranh, the army newspaper Quân Đội Nhân Dân (People’s Army), and other smaller newspapers and journals. People who were held responsible for spreading “revisionist ideas” were demoted and sent to the countryside. Everybody had to attend “reeducation classes” to fully absorb the substance of Resolution 9.Footnote 6

In order to enforce absolute conformity with the party line, Tố Hữu, the “culture tsar” of the party, opened a “special front” in the field of culture. He complained that the DRV authorities had not been careful enough when selecting foreign films, books, and plays and that therefore too many “cultural items with revisionist contents” from other socialist countries had entered the country. Thus, for example, Soviet films that only described the dark side of war, thereby blurring the boundaries between “just” and “unjust wars” and spreading defeatism, had influenced cultural life in North Vietnam.

Therefore, Tố Hữu together with Hồng Chương, Deputy Editor of Học Tập (Study), the party’s theoretical journal, started a systematic campaign to track down “revisionist influences” on cultural activities in the DRV. It turned out to be the most intense ideological struggle in the field of literature and art since the campaign against the so-called Nhân Vӑn–Giai Phẩm clique in the 1950s. The campaign significantly restricted cultural exchange, such as the import of films from those socialist countries that were denounced as “revisionist.” Foreign films imported into the DRV but classified as “problematic” were henceforth shown only to a restricted audience. This was common practice until the postwar period.Footnote 7 Similarly, in the summer of 1964, all students from the DRV studying in Eastern Europe were called back home to purge them of any “revisionist influences.” Subsequently, only a few students who were specializing in natural sciences were allowed to return to their host countries.

The antirevisionist campaign had a negative influence on relations between Vietnamese and foreigners from socialist countries in Central and Eastern Europe staying in the DRV. Vietnamese who had regular contact with diplomats and other foreigners in Hanoi were classified as potentially “revisionist” themselves and increasingly monitored. The same applied to foreigners such as Georges Boudarel, Erwin Borchers, and Albert Clavier, who had lived in North Vietnam for a long time and whose contributions to the Vietnamese revolution had been previously welcomed by the party. Now they were also classified as “revisionist” and increasingly met with distrust. Access to the offices of Soviet and East German news agencies and embassies was closely supervised and gradually restricted. The “campaign against modern revisionism” in 1964 set the stage for the coming war and achieved the “mobilization of the entire country behind the war effort.”Footnote 8

After the demise of Nikita Khrushchev in October 1964 and developments in the Vietnamese theater of war, DRV media stopped their outright attacks against “revisionist socialist countries.” In the face of the escalation of war and US bombardments on DRV territory, the leadership in Hanoi realized that it was now in dire need of sophisticated weaponry from Moscow. Internally, however, the Lao Động Party continued to fight against “revisionist influences” in the DRV – not only in politics, but also on the “cultural front.”

At a meeting of literary critics in Hanoi in May 1965, culture tsar Tố Hữu propagated the concept of socialist realism and claimed that the overriding task of artists and literary critics was “to forge in all strata of society a very high revolutionary heroism, a readiness to fight, a certainty to win, and an absolute faith in the victory of the revolution.”Footnote 9

In line with what Nguyễn Chí Thanh and other militants had written in 1963 and 1964 on the character of the war against “US imperialists,” literature and film in the DRV after 1965 celebrated “the war as a feast for all the people.”Footnote 10 Writers and other artists had to paint war and the construction of socialism in glowing colors. They absolutely had to stick to the dichotomous classification of the warring parties as “good” and “evil,” and thereby contribute to the state’s narrative of a sacred war (chiến tranh thần thánh) against the “US imperialists” and the South Vietnamese “puppet regime.” To write about the “real” face of war, about suffering and death, was tantamount to treason.Footnote 11 In other words, the authorities in Hanoi established full control over cultural and political expression – much in contrast to the less restrictive cultural policy of the Republic of Vietnam.

However, it was not the task of literature, music, and art alone to serve the war cause and to maintain wartime morale among civilians and soldiers; the whole propaganda machine in the DRV also had to foster popular support for the war and keep morale high. It did so by rigorously vetting and manipulating information on the war, by celebrating the heroic struggle against US and “puppet troops” in the South and quelling any information on the suffering and hardships of the North Vietnamese population and soldiers in the South – except for cases that could be presented as stories of heroism and self-sacrifice in order to boost morale on the homefront and on the battlefield. Thus, it censored news of the massive numbers of deaths on the Southern battlefield in order not to undermine morale.

The control of information in the DRV was so extreme that even journalists from other socialist countries who supported North Vietnam in the war against the United States were annoyed. Theoretically, they were allowed to talk to Vietnamese on the street, but the latter were forbidden to reply. And whenever an East German journalist, for example, asked the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Hanoi for a reply to an insensitive question, the ministry had to consult the VWP, which could take a long time.Footnote 12 For example, the correspondent for the East German news agency ADN in Hanoi, Hellmut Kapfenberger, complained that, due to the authorities’ restrictive information policy, “the population of the DRV is one of the worst informed populations,” whereas at the beginning of the 1960s before the campaign against “modern revisionism” North Vietnamese society still had access to a great deal of information.Footnote 13

Domestic Security and Politics at the Beginning of the War

While the propaganda machine in Hanoi strictly controlled information and aimed to keep morale high, the DRV Ministry of Public Security (Bộ Công an) enforced ideological conformity as well; after the outbreak of the war it intensified its efforts to track down and eliminate any party members and individuals who dissented with the aggressive line of the Lê Duẩn leadership. Since he had been elected First Secretary of the Lao Động Party in 1960, Lê Duẩn had increasingly relied on the security apparatus and its minister, Trần Quốc Hoàn. Several decrees at the beginning of the 1960s expanded the role of the Ministry of Public Security, turning it into an “instrument of dictatorship absolutely loyal to the party” and creating a national security state in the DRV.Footnote 14

In order to harness the institutional means to carry out a vast cleanup campaign against real and imagined “counterrevolutionary elements,” the leadership in Hanoi granted the Ministry of Public Security comprehensive authority to oversee internal security in North Vietnam and to proceed against all suspects. To establish the necessary institutional capabilities, the DRV also carried out the professionalization and modernization of its security apparatus, which among other measures included setting up scientific and technical departments within the Ministry of Public Security. In addition, the ministry stepped up its cooperation with the party’s own Domestic Affairs Committee (Ban Nội chính) and the army’s Security Department (Cục Bảo vệ).

After the outbreak of the war, Minister Trần Quốc Hoàn launched an overall offensive that aimed at the modernization of the DRV security apparatus. He proactively sent delegations to Eastern Europe to learn from the experiences of the “fraternal” security services and ask for material assistance as well. The available evidence shows that not only the Soviet Union, the German Democratic Republic (GDR, East Germany), and Hungary, but also Poland, Czechoslovakia, and the People’s Republic of China, had offered or upgraded assistance to the Ministry of Public Security in Hanoi. The aid provided by allied socialist countries to the DRV during the Vietnam War enabled the North Vietnamese security state to tightly control the public sphere and to suppress expressions of war weariness.Footnote 15

The DRV authorities responded to the sustained US bombing of the North and the deployment of hundreds of thousands of US combat troops in the South with a mass mobilization campaign that engulfed the whole population. This involved the mass conscription of males aged eighteen to forty and mobilization of women to replace men on the homefront.Footnote 16 Furthermore, Hanoi built up an air defense apparatus with the support of the Soviet Union and China and evacuated the bulk of the younger population from the cities to the countryside. While especially at the outset the evacuation was carried out in a far from perfect manner, in general it was efficient. At the same time, the DRV tried to relocate its economy and localize production.

In spite of massive US intervention, party leader Lê Duẩn and General Nguyễn Chí Thanh, commander of the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN), still believed in a total military victory and followed an offensive military strategy in the South that led to extremely high casualty rates of 222,000 in the 1965–7 period among the PAVN (People’s Army of Vietnam) and the PLAF (People’s Liberation Armed Forces of South Vietnam). This and other problems associated with the militant strategy of the party leadership led to dissent among some of those cadres who had been marginalized during the “antirevisionist campaign” in 1964. They reiterated an argument that had already been raised during the discussions in 1963 and labeled as defeatist: the party had underestimated the strength of the US war machinery in comparison to that of the French during the French Indochina War. At the same time, moderate cadres reestablished contacts with embassies of socialist countries in Hanoi such as the East German one and proposed a “more flexible foreign policy.” The VWP leadership, which unswervingly held on to the idea of a total victory and vigorously excluded diplomatic resolutions, quickly got to know about these activities.

The rifts within the party that had come into the open during the debates at the Central Committee’s 9th Plenum continued to widen. Thus, in December 1965, Lê Duẩn said in a speech to the Twelfth Plenum of the Central Committee that, “Ever since the resolution on twenty international issues was passed by the Central Committee’s 9th Plenum, our party’s Central Committee has held a steady course and has correctly implemented the policy laid out in that resolution. However, a number of comrades have mistakenly concluded that our party’s policy has changed.”Footnote 17 About one year later, in February 1966, Lê Đức Thọ, the infamous head of the Party Organization Department, issued similar warnings in Học Tập to those “few cadres” who had “erroneous and deviationist opinions” and criticized them for being “pessimistic,” of believing in the “plot of peace negotiations,” and only “relying on foreign powers.”Footnote 18 Events in 1967 were to show which “foreign power” he meant: the USSR.

In mid-1966 General Nguyễn Chí Thanh heated up the domestic climate even further. He defended his own offensive strategy and lashed out against those who overestimated the enemy and propagated “rightist ideas” and pessimism and lacked “resoluteness.”Footnote 19 His article aimed not merely at anonymous cadres, but directly at General Võ Nguyên Giáp, who had called into question Thanh’s offensive strategy in the South that involved suicidal clashes with US forces. Also against the background of this “battle of words” between the two generals, Lê Duẩn and Lê Đức Thọ increasingly became aware that Giáp was considering a challenge to their militant strategy. Further domestic developments in the DRV showed that Nguyễn Chí Thanh’s intervention had not succeeded in keeping his critics in their place and stopping the discussion about his military strategy and the option of peace negotiations.

The Soviet Union, which by 1966 had become the DRV’s biggest provider of military aid, tried to wield greater political influence on the VWP leadership. Soviet diplomats increasingly made contacts with those Vietnamese cadres whom they considered to be “pro-Soviet” and tried to push Hanoi to start peace talks with the Americans. East Germany was extremely close to Moscow, and so the GDR Embassy in Hanoi also intensified its contacts with certain Vietnamese politicians who had been sidelined in 1963 and 1964. For example, Ung Vӑn Khiêm, who had been deposed as minister of foreign affairs and since then had shunned the public eye, met the East German ambassador several times. He made no secret of his disapproval of the Cultural Revolution that had engulfed China. Officially, however, the party leadership in Hanoi abstained from any criticism. On the other side, Beijing, which had stationed 170,000 troops in the northern border provinces of North Vietnam and controlled transport logistics into the country, tried to counteract growing Soviet influence by pushing the leadership in Hanoi to wage a Maoist-style protracted guerrilla war and avoid peace talks with Washington at any cost.

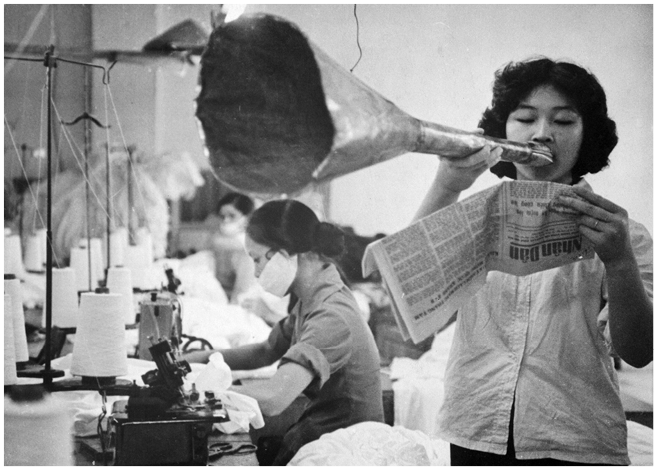

Figure 17.1 A propagandist reads the latest news to workers at a Hanoi factory using a makeshift megaphone (February 13, 1968).

Against this background the increasingly sophisticated North Vietnamese security apparatus was in full swing. East European diplomats believed they saw signs that the domestic political climate in the DRV had relaxed, but at the same time diplomats and foreign journalists were still closely monitored by the North Vietnamese security service. Similar surveillance measures applied to those Vietnamese cadres who had already been targeted during the “antirevisionist campaign” in 1964. In the second half of 1966 several editorials in the party newspaper Nhân Dân urged vigilance against spies.Footnote 20 New developments on the Southern battlefield and on the homefront in the DRV caused new challenges for the security apparatus.

Party Purge: The “Revisionist Antiparty Affair” in 1967

In 1967 the war escalated further, and fighting in the South caused heavy losses for the People’s Army of Vietnam. The DRV faced not only destruction caused by US bombardments on territory north of the 17th parallel, but also supply problems that were further exacerbated by slow deliveries of aid from the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China. The evacuation of the urban population to the countryside also went far from smoothly. There were serious problems with hygiene, for example. In addition, the supply situation was very tense.Footnote 21

Against this background political tensions in the DRV gradually escalated over the course of 1967. One factor that contributed to this increasingly tense situation was the efforts of the Chinese Embassy in Hanoi to spread the ideas of the Cultural Revolution in the DRV. The local authorities did not openly criticize the chaotic internal developments in China, but tried hard to curb the propaganda activities of Chinese diplomats, and the police in Hanoi obstructed access to the Chinese Embassy and confiscated Chinese propaganda material. However, DRV authorities in the northern border provinces had a hard time preventing Chinese Red Guards and Chinese soldiers stationed there from propagating the ideas of the Cultural Revolution on Vietnamese territory and distributing leaflets that presented Võ Nguyên Giáp as “revisionist number 1” in Vietnam and accused him of planning to overthrow the Hồ Chí Minh government.Footnote 22

At the beginning of 1967, First Secretary Lê Duẩn had decided to break the stalemate and change the course of war by launching a major military offensive in the South that would provoke a general uprising of the South Vietnamese people and topple the “puppet government” in Saigon. He entrusted his close aide General Nguyễn Chí Thanh with designing the concrete plan for the decisive offensive. However, during a stay in Hanoi in July 1967 Thanh unexpectedly died of a heart attack, which disrupted the power apparatus in Hanoi.

The preparations for the major offensive continued, but soon led to disputes within the leadership in Hanoi. Whereas Lê Duẩn and Vӑn Tiến Dũng, Chief of the General Staff, wanted to go for broke and advocated a general offensive even without decisively weakening ARVN (Army of the Republic of Vietnam) and US forces in the South in advance, Võ Nguyên Giáp had advised caution and made the offensive contingent on a prior paralysis of hostile forces. As a result, Lê Duẩn reproached Giáp of wavering. In the end, the militant faction prevailed and the preparations for a general offensive continued. At the same time, the North Vietnamese police state tightened security further. In the summer of 1967, a few months before the start of the general offensive, it lashed out against those who did not fully support the plans of the militant faction led by party chairman Lê Duẩn or who were not deemed fully reliable.

Rumors of a purge were also afloat among diplomats from the socialist embassies in Hanoi. At the end of August 1967, the GDR ambassador in Hanoi, Wolfgang Bergold, reported back home that “nothing much was going on” because most of his colleagues were on leave.Footnote 23 The Soviet ambassador complained that he only had a few reliable sources among and contacts with Vietnamese. Often the embassy “just received news that could not be verified and was sometimes contradictory. Thus, he mentioned rumors of arrests that we [the GDR Embassy] had also heard through the grapevine. Some said that ‘revisionist elements,’ others that pro-Chinese persons and still others that spies have been arrested, others are rumored to be under house arrest and then word is that they are kept in the ZK [Central Committee] to be educated.”Footnote 24 Back in the summer of 1967, neither the Soviet nor the East German Embassy could verify these rumors, but it later became apparent that they were essentially true; they referred to one of the largest party purges in the history of the Vietnamese Communist Party, which became known as the “Revisionist Antiparty Affair” (vụ án xét lại chống Đảng).

On July 27, 1967, Hoàng Minh Chính, Director of the Institute of Philosophy, Hoàng Thế Dũng, former editor-in-chief of the army newspaper Quân Đội Nhân Dân, and two other journalists were arrested. The second wave of arrests in October hit a larger group of high-ranking cadres closely linked to General Võ Nguyên Giáp: Đặng Kim Giang, Deputy Minister of Agricultural Cooperatives, whom the DRV security apparatus identified as one of the “ringleaders”; Lê Liêm, Deputy Minister of Culture; and senior colonel Lê Trọng Nghĩa. All of them had served on General Giáp’s staff during the battle of Điện Biên Phủ in 1954, as head of logistical command, highest political commissar, and director of information respectively. Others arrested included Vũ Đình Huỳnh, Hồ Chi Minh’s former secretary, and Nguyễn Kiến Giang, former journalist for Học Tập.

At the end of November 1967, shortly after the second wave of arrests, the National Assembly in Hanoi passed a decree that specified the terms of punishment for treason, plotting with a foreign country, transmitting state secrets, planning a coup d’état, and espionage. This led to a third wave of arrests in December 1967, which affected the largest number of party cadres and nonparty professionals such as Vũ Thư Hiên, Vũ Đình Huỳnh’s son; even more officers close to Võ Nguyên Giáp such as Lê Minh Nghĩa and Đỗ Đức Kiên; and many journalists who had worked for journals and newspapers that in 1964 had been under strong suspicion of having propagated “revisionist” ideas. Others included members of the Institute of Philosophy, whose director Hoàng Minh Chính had been one of the first to be imprisoned in summer 1967. Other cadres were put under house arrest, such as the economist Bùi Công Trừng, who had also been sidelined during the “antirevisionist campaign” in 1964; Nguyễn Vӑn Vịnh, Deputy Defense Minister and Chairman of the Central Committee of Reunification; and former foreign minister Ung Vӑn Khiêm, who had dared to be quite outspoken in his talks with East German diplomats.

Those arrested were first incarcerated in the Hỏa Lò Prison in central Hanoi, the former French colonial jail where captured US pilots were kept. Later they were transferred to other prisons far from the capital, where they were held until 1972 and 1973 without any trial. Some of the “ringleaders,” such as Đặng Kim Giang, were placed under house arrest until 1976 or 1977. Even after being released, they continued to be closely monitored and socially isolated as “enemies of the Party.” As a form of collective punishment, their families also faced myriad problems.

When in 1981 Hoàng Minh Chính and Đặng Kim Giang submitted official petitions to the authorities asking for their case to be reopened, they were imprisoned once again. Đặng Kim Giang died under house arrest in 1983 because he did not get proper medical treatment; Hoàng Minh Chính died years later in 2008. The families of the victims are still struggling for rehabilitation of those arrested, but to this day their efforts have been to no avail.

The available evidence supports several different ways of explaining the background of the “Revisionist Antiparty Affair.” The official version propagated by the Vietnamese authorities, with Lê Đức Thọ at the forefront, became known as early as 1967 and since then has been repeated in histories of the Vietnamese security apparatus that are no longer classified as “top secret.”Footnote 25 According to this narrative, Hoàng Minh Chính, Đặng Kim Giang, Phạm Viết, and others had tried to organize a faction to oppose the VWP, managed to gain the support of a number of high-ranking cadres, passed state secrets to the Soviet Embassy, and planned to topple the Hồ Chí Minh government. The memoirs of victims of the affair reveal that those arrested were constantly confronted with allegations that they had transmitted confidential information to the Soviet Embassy in Hanoi.Footnote 26

Evidence that Hoàng Minh Chính and others had planned a coup d’état in collusion with the Soviet Embassy or that they posed a serious threat to national security is nonexistent. At the same time, available sources show clearly that, prior to the arrests in the summer of 1967, representatives of the “dove faction” in the DRV had increasingly ventured to meet Soviet and other East European diplomats and that the Soviet Embassy itself had also proactively tried to (re)establish contacts with those within the party who favored a more cautious military approach and peace negotiations with the United States. Thus, it can be argued that, by arresting moderate cadres, Lê Duẩn and his faction sent a clear signal to Moscow that any hopes that Hanoi could be pressured into peace negotiations were groundless. At the same time, the offensive against “pro-Soviet” elements within the party was meant to please Beijing. Thus, when Nguyễn Kiến Giang met Lê Đức Thọ after his release, the latter told him that one of the aims of the arrests had been to signal to the Chinese that Hanoi was still fighting “revisionism” and keeping a distance from the Soviet Union.

Besides this connection in Chinese–Soviet–Vietnamese relations, the preemptive strike of 1967 had other agendas. As Lien-Hang T. Nguyen has argued, “Le Duan and his faction orchestrated the arrests to capitalize on this fear [the spy fever] by whipping up paranoia with accusations of espionage and treachery in order to ensure that the planning for the Tet Offensive unfolded in the utmost secrecy it needed to succeed.”Footnote 27 It was certainly not by coincidence that in February 1968 Lê Đức Thọ published a programmatic article in Học Tập that provided a belated rationale for the party purge: in it he warned against “rightist influences” in the party and “petty bourgeois elements” at the highest levels.Footnote 28 Thus, the strike in 1967 hit not only those who had actively contacted the Soviet Embassy to find support for a moderate approach that included the option of peace talks with the United States, but all longstanding opponents of the Lê Duẩn faction who had dared to speak out against the militant line of the party leadership in 1963 and later. In addition, the harsh measures taken in 1967 also reflected a hardened party line that was not restricted to the debate about a correct military strategy.Footnote 29

The arrested cadres were questioned in prisons all over North Vietnam about their alleged plans for a plot against the party with a foreign power, and the VWP leadership also launched an attack against attempts to undermine its system of agricultural cooperatives. Trường Chinh, Chairman of the Standing Committee of the National Assembly and one of the bulwarks of party orthodoxy, signed a decree stipulating harsh forms of punishments for “counterrevolutionary activities.” He targeted in particular Kim Ngọc, the party chief of Vĩnh Phú province, who had initiated the so-called product-contract system, a moderate reform that allowed farmers more freedom in production.Footnote 30

Similarly, in 1968 Tố Hữu, who had already acted as ideological watchdog during the “campaign against modern revisionism” in 1964, ordered the establishment of a commission charged with tracing “revisionist influences” in universities in the DRV. This campaign lasted for two years and was carried out with great ideological fervor inspired by the Great Cultural Revolution, which was taking place at the same time in China. At Hanoi University (Trường Đại học Tổng hợp), the person singled out as the main victim of the campaign was the well-known linguist Nguyễn Tài Cẩn, who was married to a Russian woman. In “struggle sessions” that were reminiscent of the land reform in the 1950s, his colleague Phan Cự Đệ accused him of receiving Soviet citizens in his private house, visiting the Soviet Embassy regularly, and acting as spy. The final report of the commission did not provide any substantial evidence for these charges, but the campaign had at least managed to create a “spy fever” in the academic world in DRV as well. Nguyễn Tài Cẩn kept his position; others, however, were removed.Footnote 31

In addition, the waves of arrest that shook North Vietnam in 1967 reflected a power struggle in the leadership in Hanoi. Since Lê Duẩn’s rise to power, his personal rivalry with Võ Nguyên Giáp had become obvious. Their competition further intensified because of Giáp’s more moderate and cautious approach to the struggle for the reunification of the country and to the military struggle in the South. The conflict had become evident during the debates preceding the historic 9th Plenum of the party in 1963 and then during the famous “battle of words” between the victor of the battle of Điện Biên Phủ, Giáp, and the second-ranking five-star general in the DRV, Nguyễn Chí Thanh. The latter was an integral member of the militant faction led by Lê Duẩn and served as a counterweight to Võ Nguyên Giáp. His sudden death in July had a clear impact on Hanoi’s balanced power structure, which was in danger in any case because President Hồ Chí Minh’s health was in decline. In addition to this, Giáp did not advocate the new plan for a decisive victory developed by Lê Duẩn and General Vӑn Tiến Dũng (the chief of the Army General Staff, who filled the void that Nguyễn Chí Thanh’s death had created): to launch a general offensive and incite an insurrection without crippling the ARVN and US armed forces beforehand.

Against this background it was certainly not by coincidence that many of those arrested in 1967 – such as Đặng Kim Giang, Lê Liêm, Lê Trọng Nghĩa, Lê Minh Nghĩa, Đỗ Đức Kiên, and Đinh Chân – were close to General Võ Nguyên Giáp and that Lê Trọng Nghĩa and Nguyễn Vӑn Vịnh (the latter “only” lost his positions and had his military rank downgraded) were actively involved in the General Staff’s preparation of the plans for the general offensive. That the purge of 1967 also aimed at Giáp himself and thus was part of internal factional infighting is further substantiated by the fact that when questioned by the DRV security apparatus the arrested persons were constantly asked about Võ Nguyên Giáp’s involvement in the alleged plot or – more concretely – whether he had maintained relations with the Soviet Embassy in Hanoi.Footnote 32

Interestingly, in October 1967, months before the Tet Offensive started, Võ Nguyên Giáp left for Hungary – officially for “rest” and to undergo treatment for kidney stones. Hồ Chí Minh, who had made his objections against the risky plan for a general offensive known during a Politburo meeting in July 1967, was “convalescing” in China and only briefly returned for another Politburo meeting in December. There is evidence that at this stage, when a military offensive was on its way, Giáp and Hồ Chí Minh were politically sidelined. It was only at the beginning of February 1968 that Giáp returned to Hanoi – after the general offensive had started, the opposing ARVN and US forces had begun to crush it, and the general uprising in the South had not materialized.Footnote 33

Võ Nguyên Giáp died in 2013 at the age of 102. During his lifetime, he at least indirectly rehabilitated some of his comrades who had been put into prison back in 1967. Still, to his last breath he maintained party discipline and took the memories on his role in the Revisionist Antiparty Affair to his grave. It is also possible that not only Lê Duẩn but also his close ally Lê Đức Thọ tried to settle a score during the Revisionist Antiparty Affair. Thus some of the victims and family members of arrested people claim that Lê Đức Thọ wanted to dispose of some unwelcome witnesses to his alleged dealings with the French during his term in the colonial prison of Sơn La at the beginning of the 1940s. It is difficult to substantiate these allegations, but it is striking that Đặng Kim Giang, Hoành Minh Chính, and Vũ Đình Huỳnh, three of the most prominent victims of the purge, and two journalists, Phạm Kỳ Vân and Lưu Động, had also spent some time in the prison of Sơn La.Footnote 34

While the Revisionist Antiparty Affair unfolded, planning for the Tet Offensive continued in Hanoi. The general offensive began on January 30, 1968, with attacks in thirty-six of South Vietnam’s forty-six provinces. After the Army of the Republic of Vietnam and US forces had recovered from the initial shock, they repulsed the attacks and reoccupied areas taken by communist troops. Thus, the general offensive was a military defeat. In addition, Lê Duẩn’s hope for a general uprising in South Vietnam did not materialize. At the same time, Hanoi had struck a psychological blow against the American psyche.

It is improbable that in North Vietnam’s tightly controlled public sphere people would have dared to express dissatisfaction with the disappointing military outcome of the Tet Offensive.Footnote 35 Those few cadres and intellectuals who had not completely backed Lê Duẩn’s risky plan for a simultaneous general offensive and uprising in the South, or who had attracted attention because they had previously expressed dissent with the militant strategy of the leadership in Hanoi, were behind bars and had been silenced.

Conclusion

As a result of the antirevisionist campaign in 1964 and the purge of 1967, First Secretary Lê Duẩn managed to finally assert his dominance over the Vietnam Workers’ Party. This dominance would last until his death in summer 1986.

By marginalizing and eliminating those who did not fully support his aggressive course, he did not just get rid of critics inside and outside the VWP; he also deprived the party of a critical and creative potential that could have been of some use during the war and especially in the immediate postwar period when the leadership in Hanoi mechanically started to force the socialist model of development on the former Republic of Vietnam. The purges in the DRV established orthodoxy in all fields, and it was only the death of Lê Duẩn in July 1986 and the subsequent launching of the đổi mới reforms that cleared the way for more heterodox voices. In more general terms, the war deeply affected state-making in North Vietnam. It allowed the Vietnamese Workers’ Party to perfect the party-state, to modernize and expand the security apparatus, to further social mobilization and bring the society in line in all fields – whether in politics or in culture.

It remains to be seen whether one day researchers will get access to the internal files of the party and relevant ministries and can thus shed more light on internal factional infighting in the DRV during the war. In 2018, Vietnamese state media for the first time addressed the wave of arrests of 1967 that so far had been a taboo issue, so there is a ray of hope.Footnote 36