Retro in Hungary dates to the mid-2000s, tracking with global retro consumer trends and marketing strategies of the neoliberal era. From the retro-branded revival of a sneaker first produced in 1971 to public exhibits of obsolete video games, Hungarians draw on the international retro genre to celebrate the popular and consumer culture of decades that have otherwise been seen through the lens of a stigmatized state socialism. This is accomplished by selecting for the modern, colorful imagery and branded products that were available to middle-strata citizens at the time—including those from the capitalist West—while ignoring those generic Soviet goods that once indexed an impersonal socialist state (Fehérváry Reference Fehérváry2009). In this article, I will argue that retro as a genre has been used to reposition the country within a twentieth-century history where it was never separated from a Western modernity by an “Iron Curtain.” Indeed, Hungarian Retro displays material evidence of Hungary’s full and coeval participation in the modern West as consumers and producers of world-class goods. Unlike socialist nostalgia, “Hungarian Retro” is a present-oriented re-mattering of the nation’s past, one in which state socialism effectively vanishes.

This revaluing of the past in terms of consumer citizenship is inextricable from Hungary’s political-economic history. Retro emerged around the time the country was admitted to the European Union (2004), well into the second decade of economic malaise after the collapse of state socialism in 1989–1990. This was a reversal of fortune for a nation-state once envied as the most prosperous country in the Soviet Bloc and widely considered well-prepared for rebirth as a market economy. Instead, by the 2010s, when a Hungarian Retro took off, citizens struggled to recover from the economic recession and the Swiss franc crises, more of the population emigrated for better wages to Western Europe, and the Fidesz party government embarked on its populist, “illiberal” transformation of the country. Hungarian Retro cultivates the modern past as an era of national prestige, value, and economic sovereignty relative to the demoralized present.

Like retro elsewhere, retro in Hungary emerged in the revival of older branded products in newly produced and retro-branded form; in the curation and display of vintage material and pop culture; and in the DIY reproduction and sampling of retro styles in fashions, music, and other forms of creative production. Although retro draws from the long twentieth century, its heart is the postwar period from the 1950s to the 1990s, its pop aesthetics, its consumer technologies, and its future-facing optimism. This is a time linked to the spread of television, the transnational proliferation of “youth culture,” and the rise of corporate and product branding.

In Hungary, the term “retro” shows up in the names of commercial establishments from hair salons to pizza joints (figure 1). It is used to promote events like concerts of aging Hungarian rock bands, or to lend authenticity to menu items like “retro limonádé” in hipster cafes. The beloved Túró Rudi, a chocolate-covered sweet-cheese confection dating to the 1960s, is widely considered the quintessential retro product with its red and white polka-dotted packaging.Footnote 1 The demographic using “retro” as an adjective is not limited to young urbanites with smart phones: a tiny snack büfé I saw in a Budapest hospital lobby, little changed since socialist times, advertised a “retro burger” on its chalkboard menu. Friends of mine in their fifties redecorate “retro” rooms in their homes with new furnishings manufactured to look like 1970s styles, or old and somewhat dilapidated décor now imbued with new value. “Retro” has also become the favored term for online photo archives as well as for “retro” exhibits (obsolete computer consoles, toys, typewriters, newspaper clippings, lamps, soda bottles, cell phones, etc.) that have emerged around the country as high-school history projects, in local museums, and as private collections (figure 2). The American musical Hair, a hit in 1980s Hungary, has also made a come-back in staged revivals and theme-parties (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Retro ABC convenience store in Budapest, referencing the state-owned ABC chain started in the 1970s. Author’s photo, 2014.

Figure 2: The Komet TR8 electric razor from East Germany, part of a friend’s collection of old technologies that he now refers to as “retro.” Rácalmás, Hungary. Author’s photo, 2021.

Figure 3: Getting ready for a Hair-themed New Year’s Eve party in Dunaújváros, 2015. The 1979 Miloš Forman film, based on the 1968 American musical, was a counter-culture phenomenon in 1980s Hungary. Photo used with permission.

Retro proliferates on radio, television, and online. Indeed, the retro phenomenon coincides with the rise of the internet and digital media which facilitates the widespread collection and sharing of images and information about old TV shows, outdated fashions, and antiquated technologies, and with it the emergence of new forms of shared curation and connoisseurship. On Retro Instagram, Pinterest boards, Facebook pages and online marketplaces, Hungarian speakers post, discuss, and exchange an astonishing array of things that index a modern past in Hungary.Footnote 2

The Problem with Retro in Postsocialist Eastern Europe

Throughout Eastern Europe, the problem with retro is that goods from this modern past have previously been aligned with state socialism as a system, often in explicit and negative comparison to capitalist consumer culture. Once state socialism collapsed, goods produced during the era were a reminder of a controversial past. The politicized remains of an authoritarian Soviet state (busts of Lenin, red stars) were quickly taken up and mobilized by political actors positioning themselves by opposition to the evils of “Communism in absentia” (Gal Reference Gal1994). But the commercial material and popular culture of everyday life was also a source of discomfort, exacerbated by the response of Western tourists. Tourists sought out the titillating, political symbols of their Cold War “other,” but were also drawn to the unfamiliar mass-produced and branded consumer goods of a so-called alternative modernity. These live on as Communist Kitsch, successfully marketed to tourists in themed cafes and tours, and simultaneously vilified by people who condemn the old regime (Pope Fischer Reference Pope Fischer2017). Unlike retro trends, kitsch venues reinforce assumptions that Communist products were low-quality copies of Western products, indexing a failed production system, and stigmatize those who made them as a “Communist proletariat.”

As those familiar with the region know, these negative perceptions have been challenged and at times inverted through “socialist nostalgia,” or modes of appreciating the everyday, commercial goods and popular culture produced during the decades of state socialism. Western critics as well as anti-Communist politicians worried that such affection might reflect desires to restore an authoritarian state, but scholars of the phenomenon, especially in its first two decades, generally found that such nostalgia stemmed from attachments that people had for the familiar tastes, sounds, packaging, and popular culture associated with their youth—a world that had vanished from store shelves in the early 1990s.Footnote 3 Such practices, many argued, were a critical revaluing of past experience during state socialism from the perspective of the postsocialist present, one in which people were disillusioned with capitalism and resentful of the blanket condemnation of all things state socialist. Decades on, the phenomenon continues, as new variations on “nostalgia” for the state-socialist period resurface across the region, attempts to honor positive aspects of this system from the vantage point of the present.Footnote 4

Nevertheless, “communism” continues to haunt the politics of the region. Both neoliberal and populist policies have been legitimated by their opposition to communism, a process that Chelcea and Druţǎ have called “zombie socialism” (Reference Chelcea and Druţǎ2016). Contemporary structural economic problems are thus blamed on the material worlds, values, and the kinds of people (elderly, working, and underclasses, Roma and other minorities) ostensibly produced by the communist system. This anti-communist politicization intensified with the 2010 election of the nationalist, populist government of Viktor Orbán’s Fidesz Party, which won a landslide victory over a Socialist party coalition that had governed largely by acquiescing to the economic policies of neoliberal globalization. Orban took this victory as a mandate to embark on a populist, “illiberal” transformation of the country and to purge the institutions of state of any connection with the communist period.

The Fidesz regime has also poured resources into re-mattering the Hungarian landscape to lionize its pre-socialist past, and not just the buildings of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The once-taboo authoritarian interwar period, complete with its anti-Semitic associations and irredentism, has reemerged in the form of statuary in public space (Hann Reference Hann, Angé and Berliner2015), in consumer goods like T-shirts and car stickers (Molnár Reference Molnár and Zubrzycki2017), and in new commemorations of Trianon (Feischmidt Reference Feischmidt2020).Footnote 5 Periods much earlier in Hungarian history have also become resources for neo-nationalist agendas for revaluing the nation. The roadside signs for towns now include one in the runic script of ancient Magyar tribes, while the symbol of Hungary’s first Christianizing king in AD 1000—a crown with bent cross—turns up on everything from government websites to egg cartons (see figure 5). Meanwhile, the “remains of socialism,” as Maya Nadkarni argues, from political symbols and secret police files to popular children’s games and branded sodas, continue to be drawn into the contentious process of national memory making (Nadkarni Reference Nadkarni2020). A paradigmatic example of the Fidesz regime’s efforts to rid the country of vestiges of the communist era are its auctions entitled “Never Again!” (figure 4).

Figure 4: “NEVER AGAIN, the third time.” Logo for auction held in December 2010, ridding the state of its collection of state-socialist art and artifacts. Screengrab: https://dumaszinhaz.blog.hu/2010/12/08/kalapacs_ala_kerult_lenin (last accessed 22 Dec. 2021).

In this highly politicized context, it is tempting to see retro in Hungary as another version of socialist nostalgia. There is considerable overlap in content, and both movements depoliticize the modern past and revalue it with a sense of national loyalty (Nadkarni and Shevchenko Reference Nadkarni and Shevchenko2004). But retro purveyors often explicitly reject “nostalgia” as a label and a sentiment, and just as importantly, state socialism as a frame is jettisoned altogether. Of course, certain objects or pop cultural references in retro collections can provoke memories or even “nostalgic” sentiments, just as the term “retro” can be deployed a variety of ways. Nonetheless, attention to how retro is curated, displayed, and discussed in Hungary shows that a “Hungarian Retro” has emerged as a shared genre, one attuned to contemporary styles and market sensibilities rather than evocations of the past.

In this article, I argue that a Hungarian Retro draws on the global retro genre to reframe the matter of the modern past in Hungary as coeval and of consequence—mattering—in the regimes of value of the modern world. Retro challenges conventional narratives of the region which posit a shabby, derivative modernity in which Hungary is figured as a backwards and poor eastern province, cut off by an “Iron Curtain” from the authentic modernity of the West, and instead places Hungary within a modern twentieth-century narrative of economic, technological, and cultural progress. Unlike socialist nostalgia, Hungarian Retro does not limit itself to what was produced within the state-socialist “bloc” or during the Communist period (1948–1989).Footnote 6 Rather, it embraces the more expansive twentieth-century periodization of retro as it has emerged in the West, and includes fashions, consumer goods, and pop culture from across the Cold War geopolitical divide. Hungarian Retro connoisseurs cull from abundant material evidence for this coeval modern, evidence that attests to not only Hungarian knowledge about international, and particularly Western, fashions, technologies, and consumer goods, but also access to a variety of these accoutrements of modern life. In contrast to the present, when few products are still “made in Hungary,” Hungarian Retro also lavishes attention on formerly well-known Hungarian brands and their commercial cultural production.

The combination of the retro genre’s origins in the Euro-American West during the Cold War, its unsentimental pillaging of the commercial culture of the past, and its international success in the twenty-first century, all make it particularly compelling for people in former state-socialist countries like Hungary. The world celebrated by retro can be presented as shared by capitalist and state-socialist twentieth-century modern projects, pursuing shared “dream worlds” (Buck-Morss Reference Buck-Morss2002) of a future-facing, utopian modernity materialized in and made possible by modern consumer goods, infrastructures, and technologies. From the perspective of the globalized, financialized capitalism of the present, the similarities between state-socialist and capitalist economic production in the second half of the twentieth century can appear greater than their differences. This includes a time characterized by Fordist production, when brands were still tethered to factories in which their products were made, and one could speak more meaningfully of “national economies.” It can also be seen, retrospectively, as a time when the Euro-American West (rather than global North/South divide of today), was still the undisputed center of the modern world. Instead of the stigma of a peripheral, derivative modernity, the retro genre can be plausibly used to assert Hungary’s full participation in this European modernity, one in which it never had to catch up with the West because its own consumer culture evolved alongside that of powerful capitalist countries. This framing has the power to counter the demoralizing economic climate of the past few decades, including the decline of Hungarian manufacturing and the prejudice against Eastern Europeans in Western Europe.

Retro is constituted by materials that index a past divided into decades and that conjure affective imaginations of them. This is made possible by the capitalist drive for product innovation and design that renders goods obsolete long before they have worn out, turning them into markers of their time. The question “What is retro?” usually elicits lists of decade-specific things—a TV show, a kind of technology, or a candy bar—that often index a person’s age. People argue over whether something is or is not retro, but the category is made meaningful primarily through the material rather than through discourse, namely, by pointing to it, exhibiting it, populating it, and understanding it by exposure to how it is made by others. Therefore, for my analysis, I draw on a semiotics focused on material things, how they are assembled, and what is left out.Footnote 7 I attend to how particular designs, colors, graphics, smells, tastes, and sounds both conform to and constitute “aesthetic regimes” for specific decades (Fehérváry Reference Fehérváry2013: 3). This focus on the material also moves us beyond representation. Hungarian Retro materials are not just symbolic of a former “modern life,” but are evidence of what once constituted that life: the silhouette created by flared jeans; the mobility and thrill offered by the motorbike; the hairstyles requiring a light-weight plastic hair dryer.Footnote 8

When considering the relation of materialities to identities on the scale of the nation-state, this article builds on scholarship on the ways material culture makes the nation tangible in everyday life and deployable for various projects, what Geneviève Zubrzycki has captured with the expression, “national matters” (Reference Zubrzycki2016). My focus is on the specific materialities of mass-produced consumer goods and their role in the making of national identity (Foster Reference Foster2002), including how a people identify with the value of their nation-state’s exports and imports in global prestige hierarchies. This form of national identity is often experienced as inescapable and prescribed rather than elective or simply imagined. Even those Hungarians eager to embrace an identity as a “European” are reminded of their second-class status as east Europeans when traveling or working in Western Europe, or by the limits they experience in being bound by Hungary’s borders, its currency, its laws, and its politics.

The argument proceeds in three parts. The first provides a brief history of the retro phenomenon and then situates it in the process by which mass-produced consumer goods index the value of nation-states and their citizens in global hierarchies of value. Part two provides three examples of Hungarian Retro that feature mass-produced, durable consumer goods:Footnote 9 (1) the Tisza Cipő retro-branded shoe, launched in the early 2000s by a young Hungarian entrepreneur in Budapest as a faithful but upscaled reproduction of the “classic” Tisza from 1971; (2) a “Retro Exhibit” of twentieth-century goods and technologies collected by a middle-aged teacher in a provincial town in 2014; and (3) the website “Retronom.hu,” active since the late 2000s, in order to engage with retro’s vast online presence in Hungary. These three examples are united in their presentation of a past in which Hungary was a player in a global marketplace and in which state socialism as an historical period, a political ideology, or an economic system, is systematically ignored. In part three, I summarize my findings and consider what has been erased by this revisionist history.

I. Retro: Consumer Goods and National Value

“Retro” today is generally defined as a valorization of things from the modern past that can be deployed in the present as style. These characteristics have been central to the phenomenon since it first emerged in the Euro-American West in the 1970s. Because of the genre’s focus on the commercial culture of the twentieth century, it participates in the process by which mass-produced and mass-mediated consumer goods stand for the value of nation-states and their citizens in a global hierarchy of value. National reputations on a global stage have long been linked to a country’s consumer good exports and the “fame” they generate circulating in the world, like emissaries of national value.Footnote 10 This value is produced both by market exchange and the specific material qualities of these exported goods. For Simmel, exchange reveals the momentary value of something because others must sacrifice to acquire it; such value is not stable but determined by the conditions within which an exchange takes place as well as how the partners in the exchange are situated, or what Appadurai (Reference Appadurai and Appadurai1986) has called “tournaments of value.” As a tournament of value, the global marketplace is not a neutral space of abstract fungibility or total commodification in Marx’s sense. It assigns value to products according to hierarchies of power and prestige, something businesses and nation-states still attempt to manipulate with labels such as “Made in Italy” (Yanagisako Reference Yanagisako2018). The material qualities of goods (as indexes in the Peircean sense) can come to signify the places they were produced as well as the “character” of the people producing them. A nation-state’s standing in such hierarchies, based on its economic prowess and the desirability of its exports, is one factor in the pride or shame that people feel in relation to their nationality—particularly in how they are identified. However, it is rarely noted that the prestige of a nation-state is also indexed by how and what its citizens are understood to consume. National and regional identities are constituted not only by the consumption of locally produced cuisines and products, but also by the kinds of goods imported for domestic consumption, including mass-produced commodities, as Robert Foster has shown (Reference Foster1999: 268).

In Europe in the twentieth century, modernization became the overriding metric for measuring national value, and by mid-century, this “modern” was being materialized not just in modern infrastructures but in mass-produced consumer goods. The countries and corporations of the Euro-American West and eventually Japan were the “source” of this modern through the export and mediated circulation of fashions, popular culture, and mass-produced consumer goods, increasingly identified by trademarked corporate brand. These things did not just project a modern future, but brought that modernity into being with new technologies, fabrics, colors, sounds, and leisure pursuits. The urban centers of these powerful countries defined the temporal edge of “the modern” against which the rest of the world’s “backwardness” was measured, a dynamic that came to define the Cold War. The socialist states of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union were drawn into a competition to prove that the socialist system would allow them to catch up to and surpass the West in providing modern lifestyles for their citizens (Reid and Crowley Reference Reid and Crowley2000).

* * * * *

Retro as phenomenon emerged as one of many postmodern preoccupations with this “modern” in the Euro-American West. Early retro practitioners were particularly attracted by the growing material detritus of mass-produced consumer goods, as the rapid temporalities of the modern dictated that it be incessantly produced anew. According to art historian Elizabeth Guffey, retro enthusiasts shared in postmodernism’s “self-reflexiveness, its ironic reinterpretation of the past, its disregard for the sort of traditional boundaries that had separated ‘high’ and ‘low’ art” (2006: 21). Indeed, retro-chic in fashion was produced as much by amateurs sifting through available material and media culture as by fashion designers or clothing retailers and was drawn as much from finds in thrift shops and flea markets as by imitating what was on catwalks and in film (Guffey Reference Guffey2006: 17). By selecting items from the discarded modern material culture of the recent past, retro celebrated the kinds of things that had previously been thought of as junk. No longer fashionable but not old enough to qualify as antique, retro aficionados revived these goods and styles as quirky, unique, and anti-hierarchical (Baker Reference Baker2012: 624–26). Unlike postmodern nostalgia, however, with its melancholic take on the fleeting passage of time and loss of faith in a modern future (Boym Reference Boym2002), retro regarded the past with unsentimental detachment (Guffey Reference Guffey2006: 25; see Ivy Reference Ivy1995: 56, on unsentimental “nostalgia as style” in Japan). Retro producers and enthusiasts were never much concerned with the conventional historical periodization found in textbooks. They were less interested in remembering the modern past than in pillaging it for styles to deploy in the present.

By the 1990s, retro’s revivalist imagery had made its way into the mainstream, “shaping how the recent past was being presented in advertising, film, fashion” (Guffey Reference Guffey2006: 27), and extended to furniture and obsolete technologies (Baker Reference Baker2012: 623–26). It was also going international. With the end of the Cold War and the spread of neoliberal globalization, old barriers were removed for the flow of “Western” mass-produced commodities and media into the former Soviet Bloc as well as to other countries around the world that had managed to limit imports. Retro as a genre was also boosted by the success of a new marketing strategy known as heritage- or retro-branding (Brown, Kozinets, and Sherry Reference Brown, Kozinets and Sherry2003). Corporate marketers began selecting iconic branded products from the past and reissuing them in updated form, as in the revival of the Volkswagen Beetle in 1997. Alternatively, corporations acquired the rights to old, defunct brands to repurpose for new ventures. In both, retro-branding capitalized on impressions of local, artisanal craft production in the digital age of knowledge work.Footnote 11 By renewing or inventing historical continuities, brand managers hoped to counter the effects of deterritorialization on brands, as globalizing production chains eroded the indexical connections between brands and modern nation-states, the labor of their citizens, and the branded goods they continued to claim as their own (Nakassis Reference Nakassis2013: 112). Internationally, commercial retro-branding was also key to publicizing retro as an urban, cosmopolitan hipster style. Thus, by the mid-2000s, the retro phenomenon was becoming a shared genre, reproduced in films, fashions, café décor, and exhibits in metropolitan centers around the world, from Berlin to Jakarta, London to Seoul.

For scholars who study retro subcultures or practitioners in the Euro-American West, it is taken for granted these groups draw on a Western modern past. After all, retro aesthetics refer to decades when the Euro-American West (and later Japan) defined what it meant to be “modern” in the form of exported modern consumer good design, technologies, and popular culture.Footnote 12 And yet, the Western provenance of retro complicates how it can be been taken up elsewhere in the twenty-first century, given diverse twentieth-century histories of modern development and commercial culture, not to mention colonialism and independence movements. Deployments of retro style have to contend with local histories, including their relationship to the West and the degree to which they participated in this modern popular culture at the time. Retro in South Korea, for example, intersperses South Korean items from the 1990s with iconic Western ones, such as a retro cafe in Seoul built around a classic VW bus. It also takes the form of creative use of retro styles from elsewhere to produce a new Korean retro aesthetics (dubbed “Newtro”) found in K-pop fashions or popular TV series, and where “vintage” traditional Korean clothing is worn with a modern twist.Footnote 13 In Indonesia, on the other hand, Brent Luvaas (Luvaas Reference Luvaas2009) has shown how the very lack of an Indonesian commercial or pop cultural archive enables local indie bands to deploy retro styles as a way of escaping the provincialism and specificities of ethnic differences within the multiethnic country. These styles, along with the English language, allow them to avoid reference to local languages or “traditional” motifs in order to take their place within a global indie music scene.

In Eastern Europe, retro’s appearance on the scene in the 2000s was felicitous, as it was fairly easy to align the region’s modern pasts with Western modernity and capitalism, albeit not in uniform ways.Footnote 14 As I will elaborate in the next section, these countries had a rich history of participating in the twentieth-century competition to define the modern good life, and people also had a wealth of evidence to prove it—in the backs of closets, on book shelves, and in storage units. Moreover, the populations of these countries had been primed, at least since the state socialist period, to understand themselves in terms of these geopolitical hierarchies of value, of valorized modern to stigmatized left-behind, hierarchies constituted and maintained through consumption and exchange.

As elsewhere in the Soviet Bloc after the 1950s, the Hungarian state-socialist regime under János Kádár tied the legitimacy of the economic and political system to the provision of not only the material necessities of life (subsidized food, drink, housing, utilities, transportation, education, and medical care), but to a modern good life measured against the one emerging in the Euro-American West (Fehérváry Reference Fehérváry2013). While within the Soviet Bloc, institutions such as COMECON were meant to orchestrate economic cooperation among member states, competition between these nation-states prevailed along with aims of national sovereignty (Balassa Reference Balassa1992). These socialist states retained distinct national economies with unique constellations of property regimes, degrees of central planning, and legal systems. They entered into trade agreements with so-called capitalist countries as nation-states, they exhibited technological and design innovations at international trade fairs, they developed flagship firms—including national airlines such as Hungary’s Malév—and they produced branded consumer goods for both domestic consumption and export. In Hungary, the state-run media regularly reported on how the country was represented through its branded exports, ranking the country in comparison with other east European countries as well as Western ones, promoting identification with the fortunes of high-profile national companies almost as much as it did the fortunes of national sporting teams.

State-socialist countries trademarked goods in part to participate in a global market (Vida Reference Vida1982), where such exports could be exchanged for all-important hard currency.Footnote 15 In Hungary, the fact that branded goods like Tungsram light bulbs, Ikarus buses, and Orion television sets were sold and recognized outside of the bloc was a source of pride, as was Hungary’s enviable reputation within the bloc for its modern lifestyles and production of desirable consumer goods. Likewise, it was a source of frustration when products successful in the West were not recognized as coming from Hungary. Maya Nadkarni articulates this phenomenon with the example of the Rubik’s Cube. Although it had “found its way into nearly every American household” by the 1980s, it was “rarely recognized as a Hungarian invention. It failed to export Hungary’s self-image as a nation whose scientific skill and creativity was on par with more affluent countries … even as it demonstrated that its products could indeed provoke reciprocal consumer desire” (2010: 207).

An East-West hierarchy developed within the bloc as well, materialized in the quality of imports and exports. It was well-known that the highest quality goods were exported to Western nations, and at the same time, imported goods from the West—from tropical fruit and coffee to perfume brands and clothes—were considered luxuries by central planners (Mihályi Reference Mihályi1989: 57) and routinely set apart through special packaging or by sale in special shops. Meanwhile, goods shipped further east tended to be of the lowest quality, many of them destined for the Soviet Union. The hierarchies of value embedded in trade reinforced the equation between the quality of goods and the quality of people.

This dynamic intensified after the regime change of 1989, when neoliberal capitalism became the dominant model in the region for building a market economy (Appel and Orenstein Reference Appel and Orenstein2018). Domestic economies were opened up to foreign goods and retail chains just as state-socialist markets were collapsing. Even fairly successful domestic factories had little chance of survival, since they had long failed to break into markets dominated by manufacturers from the United States, Western Europe, and Japan.Footnote 16 Almost overnight, the familiar assortment of mass-produced goods vanished from store shelves, as domestic products were cast aside in favor of long-coveted brands from abroad. Indeed, by 1990, the referent for “branded goods” (márkás cikkek) had become so aligned with iconic capitalist brands that when Western market researchers asked Hungarians about their access to branded goods, it did not occur to either the researchers or their respondents to think of state-socialist brands (James Reference James1995).

Generations coming of age during the neoliberal reform era of the 1990s and 2000s did so as consumers in a highly differentiated consumer goods arena that included upscale shopping malls and high-end luxury brands along with flea markets selling knock-off branded goods, second-hand shops of “American and UK” clothing, or stores selling garments by the kilo from China and Turkey. These goods and venues have materialized the social and economic inequalities that have stratified the population since 1989, but also the relative value of Hungary and Hungarians in a global ranking. As Magda Crăciun has observed for Romania, generations too young to remember the state-socialist years have experienced “similar feelings of being second-class citizens through their own encounters with low quality consumer goods” (Crăciun Reference Crăciun2015: 17). Indeed, in 2017 a European Union commission found that the contents of brand-named goods produced for sale in Eastern Europe—from Nutella to baby food—were often of lower quality than those sold in Western Europe, despite identical packaging and similar prices.Footnote 17

Meanwhile, “Hungarian” products became harder to find. Even when factories were not closed down, their subsumption under multinational corporate brands meant the loss of recognition for companies with brand-name histories extending back to the 1800s, as well as those established under the centralized economy of the socialist state.Footnote 18 Hungarian Retro’s revival of old brand names and logos responds to the loss of manufacturing jobs but also of “Hungarian” control over and recognition for “export quality” mass-produced goods. For example, in Audi’s new components factory in Hungary, Audi employs skilled labor from the former Rába plant which had manufactured vehicle parts for over a hundred years. While the jobs are welcome and there is some pride in Audi’s confidence in the quality of Hungarian labor, credit for the goods produced still goes to Audi, and by extension, to Germany (Bartha Reference Bartha, Kalb and Halmai2011). As with the Rubik’s cube, Hungarian labor and expertise go unrecognized as the source for high-end Audi components. In this context, labels such as “Made in Hungary,” “Hungarian Product,” or “Assembled in Hungary” have proliferated, even as fragmented supply chains and rapidly shifting production sites make it ever more complicated to nail down what they mean.

As elsewhere in Eastern Europe, governments in Hungary have mounted various nation-branding campaigns to overcome the negative stereotypes plaguing the region in order to court foreign investment, promote tourism, and advertise manufacturing capacities (Kürti Reference Kürti, Sándor, Péter and László2001). Such initiatives have spawned a voluminous scholarship, part of research on the ways neoliberal capitalism, contrary to expectation, has spawned new forms of ethnic and national affiliation.Footnote 19 As Özkan and Foster demonstrated with Turkey’s launch of Cola Turka, transformations in the global economy pushed states to innovate “new strategies for defining the … nation vis-à-vis other nations or … for making and managing national culture” (Reference Özkan and Foster2005). In Hungary, these campaigns have consistently worked to distance the nation’s “brand” from anything to do with the “communist” era.

Since 2010, the right-wing FIDESZ government has shifted the emphasis of these campaigns inward, towards fortifying national pride. This includes the aggressive promotion of recognizably Hungarian stuff by branding it as Hungarikum, a mark of authentic Hungarian provenance that was initiated in the private sector. Hungarikum was institutionalized in 2012 with a parliamentary act that grants special status to a range of products, places, buildings, animals, techniques, and even people, both within Hungary and outside its borders. A multi-tiered but secretive evaluation procedure determines if something is worthy of representing “the high performance of Hungarian people thanks to its typically Hungarian attributes, uniqueness, specialty and quality.”Footnote 20 The Hungarikum logo (figure 5), a stylized motif of the ancient crown with tilted cross, indexes the kinds of products that tend to qualify, namely those with strong associations with traditional, regional Hungarian heritage from Szeged paprika and Tokaj dessert wines to breeds of hunting dog, or iconic trademarked brands like Pick Salami, Zwack Unicum bitters, and Herend porcelain.Footnote 21 In keeping with nation-branding efforts of early decades, almost nothing innovated and mass-produced during the state-socialist decades has qualified.

Figure 5: Hungarikum logo of crown with tilted cross. Used with permission of the Hungarian Agriculture Ministry, 2021.

The tumultuous experience of the regime change in the 1990s, widely regarded as the triumph of capitalism, overwhelmed how the quotidian mass-production of the previous decades could be framed. It would take some time before these goods could be seen through something other than the lens of state socialism.Footnote 22 An early example of “retro” in Hungary was, in fact, a clothing chain called Retro Jeans that was branded as if it were selling Western streetwear, with no indication it had been founded in 2001 by a young Hungarian to target the east European market. Eventually, a distinctly “Hungarian” retro emerged as commercial actors began to see the potential value of retro-branding old, defunct Hungarian products that would stand out in the new retro market. In the following three examples of retro practices, I thus begin with the retro-branded Tisza shoe, and then move to non-commercial venues.

II. Hungarian Retro

Retro Tisza Shoe Brand

The retro-branded Tisza Cipő helped to promote the idea that mass-produced goods from the Hungarian past could have market value if they fit the international aesthetic criteria of retro. After its launch in the mid-2000s, the “Tisza shoe” quickly became admired by Western hipsters used to dropping over 100 Euro for a pair of sneakers as well as by a generation of Hungarians too young to have experienced the original.Footnote 23 The Tisza “story,” as told to me by the marketing director and repeated in other publicity for the brand, begins with a young entrepreneur named László Vidák who had become familiar with the retro-shoe trend from his work with a multinational company, and in the early 2000s started looking for a local brand to target the high-end niche market (interview Szaplonczai Mátyás, Nov. 2010). One day, he spotted a man in Budapest wearing an old but well-kept pair of Tisza shoes and realized they would be perfect. By 2003, he had persuaded the Tisza Factory in Martfű, on the banks of the Tisza River, to sell him the name, logo, and rights to the original designs (figure 6). In the deal, he got the original shoe-forms and hand-drawn design specifications, and thereby obtained the material connection to an authentic retro product necessary to target a new generation of consumers. A corporate brand design firm helped him stage a publicity campaign of pop-up shops in vintage Hungarian Ikarus buses that had enjoyed a global export market in the 1970s (Katona et al. Reference Katona, Kovács, Papp-Váry and Sáfrány2008). In the downtown store, poster-size photographs zeroed in on the weathered hands of Hungarian workers, stained with dye, crafting the limited editions of the new Tisza shoe, now made of high-quality leather on patinaed shoe forms and using “original” machinery to stitch in the iconic “T” logo.

Figure 6: Tisza shoe with trademarked logo, ca. 1972. Screengrab, 2013.

The sign over the Tisza Cipő store front (figure 7) proclaims: “Registered quality trademark since ’71,” referring to the year the state-owned shoe factory’s management registered the “T” logo and, following trends emerging in Euro-American markets, integrated the logo into the sport shoe’s design. A young salesman with ear gauges told me that these had been good enough to attract the attention of Adidas, which then subcontracted with the Tisza factory to produce a line of soccer cleats (“La Paz”). The Adidas story was repeated as part of a narrative across the self-branded stores and website as evidence that Tiszas were considered a world-class product back in the 1970s, exported to desiring consumers in the West as well as to the state-socialist market. This narrative also suggested that Tiszas had been continuously produced at the Tisza factory in Martfű since the 1970s, even though production there ended in the 1990s when Tisza’s former clientele abandoned it for newly accessible global brands. The Tisza brand had once been isomorphic with a specific place and factory along the Tisza River, making it stand out against a backdrop of largely unbranded shoes of state mass production. The new Tisza Shoe brand, in contrast, is now severed from the Tisza Shoe Factory and attached to shoes produced with subcontracted labor on the outskirts of Budapest.Footnote 24

Figure 7: Tisza’s own-brand store in downtown Budapest. Author’s photo, 2014.

Tisza Cipő’s pricing is justified by reference to their high-quality materials and by the claim that the shoes are 100 percent “Hungarian made,” contrasting them to the mass-marketed shoes manufactured by unknown and “cheap” labor in far-flung parts of the world. And while the in-store posters displayed the manual labor of older, skilled workers, the website featured the creative labor of a young, Hungarian professional design team that keeps abreast of shifting style trends. Like retro-branding elsewhere, the website claimed that “the authentic designs of the past are brought up to meet the expectations of the twenty-first-century customer.”Footnote 25 Its English-language “history” section now introduces Tisza as “a heritage brand” that got its “corporate logo” in 1971, and was renewed in 2003, with no mention of state-socialism.Footnote 26

The popularity of Tiszas was not always shared by my older, well-educated friends who had experienced Tiszas back when they were made with a PVC sole. As they gently reminded me: “You know, my parents couldn’t afford Adidas for my brother and me, so we got stuck with Tiszas,” or “Tiszas weren’t that great back then. We liked them alright for socialist products, but they were a cheap version of Adidas.” Thus, while Tiszas were once regarded as an improvement over the kinds of shoes mass-produced during state socialism, they were still considered a passable imitation of Western brands. They resembled what Vietnamese consumers call a “mimic” good: neither original branded good nor useless fake, but an accessible and fairly well-produced imitation (Vann Reference Vann2006).

Today’s retro-branded Tisza inverts this equation. The Tisza shoe is an authentic branded product, made in Hungary, and positioned as unique against the ubiquitous Nike and Adidas lines. For younger generations, the Tisza Shoe is a desirable product from the Hungarian past that meets the criteria for the particular 1970s retro aesthetic promulgated by powerful media and fashion industries (figure 8). In the 2010s, Tisza fans from this demographic commented to me or on Facebook that they liked taking foreign visitors by the store to see an exemplar of Hungarian quality and style reaching back to the 1970s. The politics of Hungarian Retro for these consumers are not about questioning the political economy of contemporary capitalism, beyond a “buy Hungarian” consumer citizenship. It is thus not surprising that I found admirers of the brand from across the political spectrum. Tiszas are seen as a genuinely Hungarian product, one that provides material evidence of continuous Hungarian participation in regimes of value that matter today as both consumers and designer-producers of an internationally desirable product.

Figure 8: Tisza shoes on the Budapest metro. Author photo, 2021.

Retro Exhibition

The logic of retro in Hungary quickly expanded beyond newly branded products like Tisza shoes to the celebration of actual goods from the modern past. In contrast to socialist nostalgia displays, retro exhibits more closely resemble exhibits elsewhere in the world showcasing the commercial design of industrial consumer products and technologies, such as vintage motorcycles in New York and Berlin, or antiquated computer and gaming consoles in London or Nagasaki. The “Retro Exhibit” (Retro Kiállítás) I discuss here was a temporary display I visited with a friend in 2014, in the new, EU-funded buildings of the junior technical college in the provincial factory town where I had done long-term fieldwork. The middle-aged curator, Csaba Bús, a high school teacher, talked to us about the saga of finding a venue for his collection. The city had been built in the early years of the Communist regime alongside a new steel mill, and since the collapse of state socialism city leaders had struggled to rebrand it as a center for innovation and entrepreneurship. They had refused to endorse any tourism initiatives that attempted to build on the city’s Communist past, and apparently saw the Retro Exhibit in this light.

Bús explained that the collection had started by chance when he found himself with multiple cell phones from the 1990s that had rapidly become obsolete. Instead of discarding them, he added to his collection through donations and purchase, gradually amassing enough to fill a storage shed. The centerpiece of the exhibit was the iconic object of 1960s international youth culture, the motor scooter, but instead of an Italian Vespa, this was a dark red Verhovina, mass-produced in Soviet Ukraine and imported to Hungary in the 1970s (figure 9).

Figure 9: Verhovina motorcycle, Retro Exhibit. Author photo, 2014.

Exhibit attendees included people who recognized things from their youth in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, but also students who wandered in to check out the array of technologies. They started with a table of colorful toys, primarily cars, trucks, and trains as well as games in their illustrated packaging. A Roulette set that several attendees happily recognized was displayed next to a board game designed to teach youngsters traffic signals (figure 10). Dispersed through the games were a few empty bottles of defunct Hungarian soda brands like Sztár. This display of mass-produced consumer goods iconic of twentieth-century “capitalist” modernity, from gambling to automobility, was followed by a table covered with the accoutrements of white-collar office work: old calculators, a digital accounting machine, antique manual typewriters including an American Remington, a few electric typewriters, and even an early desktop computer, the Indian brand SYQUEST.

Figure 10: Roulette Game, Retro Exhibit. Author photo, 2014.

The table was also decorated with awards, service medals, and “best mechanic” pendants in wine-red or the Hungarian tricolors (red-white-green), embossed with the acronyms of factory-firms. On one of these, one could make out a tiny red star, but given the continuing importance of the steel factory as a workplace, these would be recognized as awards for exemplary work. The little red stars were among the scant glimpses of the old political regime in the entire exhibit. Nonetheless, Bús had included a small disclaimer: “Attention: The symbols of tyranny included in the exhibit do not mirror any kind of political or ideological persuasion. Our goal is the most faithful display of history.”

Figure 11: Table with cameras, Retro Exhibit. Author photo, 2014.

The rest of the exhibit was a cornucopia of technologically obsolete, brand-name consumer goods displayed in similar fashion. The largest collections were of cameras, telephones, and stereo equipment. The camera display (figure 11) included an antique wood and brass accordion box camera alongside an East German Praktica, the Soviet SMENA, and the Zenit-E, a West German Agfamatic pocket camera, a Keystone Everflash with “Made in the USA” prominent, a Kodak instant camera, the Hungarian Pajtás box camera, the SONY digital Mavica, and a Soviet PYCb home movie projector. Some were displayed with colorful but faded packaging or a user manual. In setting out these cameras, no effort was made to mark off historical periods, conventionally defined, nor to indicate Cold War divisions of East and West. Here Japanese, Soviet, Canadian, Hungarian, East German, and American brand name cameras were assembled as evidence for Hungarian access to and use of one of the twentieth century’s most significant technologies for modern-self fashioning.Footnote 27

A century’s worth of telecommunications and music technology was set out with a similar logic. One table held a switchboard set from the 1920s, colorful and sturdy circular dial phones from the 1970s and 1980s (figure 12), as well as the technology that had inspired the entire collection: the succession of cell phones (figure 13). Above it, a poster board educated attendees on the history of the telephone, including Hungary’s rapid adoption of the technology in the late 1800s and the contributions of Tivadar Puskás, who ran Thomas Edison’s affairs in Europe. Phone cards from the 1990s were arrayed under a Westel telecom Map of Hungary. Here, the country was presented as actively integrated into the twentieth-century modern telecom and connected to the world through its technology.

Figure 12: MM rotary-dial telephones of the state-owned company. Author’s photo, 2014.

Figure 13: Cell phones, Retro Exhibit. Author’s photo, 2014.

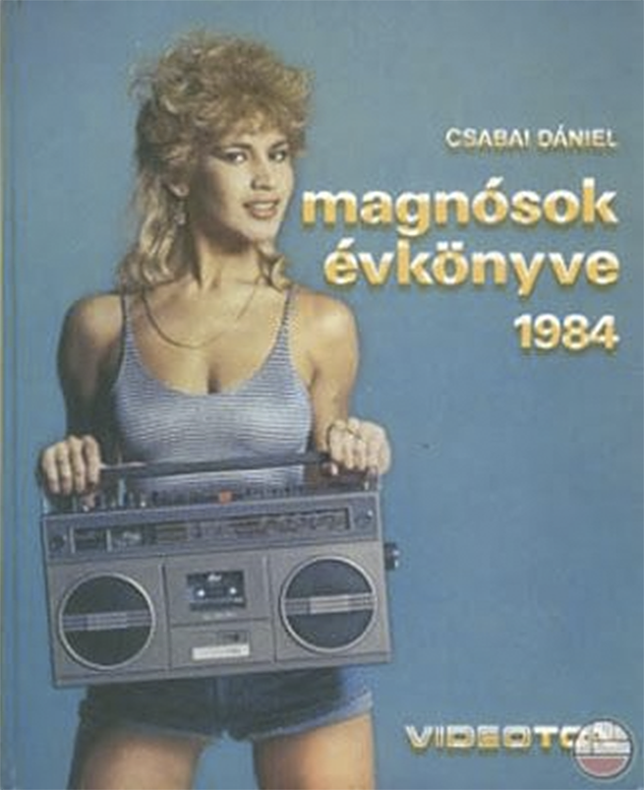

Another table was covered with branded audio technology, beginning with a gramophone, and moving to electronics. A Toshiba TAYA turntable was adorned with a 45 single by The Who, ready to play (figure 14), while another sported a vinyl record by Hungary’s 1970s disco band Neoton Família. Next was a Japanese AKAI reel-to-reel with a Hungarian language manual on top; a small, portable cassette player from the Budapest Rádio Gyár with “BRG Cassette” embossed on a strip of faux wood; a Videoton boom box, a Sony Walkman, and an assortment of digital music technologies. These provided evidence that people in Hungary had not only shared the technology of an international youth culture but had also shared in its music as both consumers and as producers.

Figure 14: A Japanese TAYA turntable, with a 45 r.p.m. record by The Who, put out by the Hungarian label Pepita. Author’s photo, 2014.

This exhibit was a concrete example of how “retro” collections are displayed to differentiate them from both “socialist nostalgia” and “kitsch.” Socialist nostalgia collections are characterized by affection tinged with loss (Nadkarni Reference Nadkarni2020: 85). While they sometimes valorize the remembered superiority of socialist products (especially of favorite foods), consumer goods are often regarded with fondness as much for their deficiencies as in spite of them. Kitsch, on the other hand, reinforces assumptions that Communist products were of low-quality, in part by presenting them as so much trash, piling up multiples of the same discarded and yellowing television sets, with brand-names obscured, as evidence of generic, shabby, and monotonous mass production. Kitsch also jumbles object types together, placing unpackaged, cheap plastic toys next to stylized photos of celebrity athletes, or kitchen utensils alongside iconic posters of Communist politicians (see Pope Fischer Reference Pope Fischer2017).

In contrast, the Retro Exhibit suggested an abundance of high-quality goods from around the world available to Hungarian citizens throughout the twentieth century. Goods of Hungarian and COMECON production held their own among Japanese and Euro-American brands. Just as the Tisza Store supplied evidence of Hungary’s participation in global fashion trends, the Retro Exhibit interspersed goods of Hungarian mass-production with foreign consumer brands from East, West, and Far East as coeval and of equal value. And just as the Tisza store glossed over the product’s demise in the 1990s to produce a continuous brand lineage from the 1970s through the 2000s, the Retro Exhibit extended this temporality backwards to the early twentieth century, emphasizing Hungarian technological prowess, business acumen, and national prosperity over political or economic systems.

In my conversation with the laconic collector, I asked why he had chosen “retro” instead of “nostalgia” for his exhibit. He replied that “retro” was more about “remembering fashion,” and returned to the theme of technological obsolescence and the cellphones that had started his collection. Initially, I assumed he was circumventing the contentious politics of socialist nostalgia, but in my subsequent exploration of retro I came to understood that, instead of mourning the disappearance of socialist-era products, the Retro Exhibit explored the experience of rapid obsolescence as a phenomenon central to modern subjectivity everywhere.

The logic of the Retro Exhibit also re-mattered Hungary’s place in the history of modern technology. This was clearest in the poster boards which celebrated technology companies: the Japanese company Sony, and Hungary’s BRG, Orion, and Videoton. The SONY board focused on the company’s pioneering innovations for home electronics, decentering the West and particularly the United States as the global technology leader. At the same time, it aligned Hungary with Sony against the rest of the Communist world. Sony’s chairman, the text claims, refused to work with China or the Soviets. This was not for political reasons but because the “primitive” circumstances there failed to meet Sony’s standards for producing quality goods, while SONY “operated production units in our country.”

The boards for Videoton and Orion, meanwhile, traced in iconic form the exhibit’s twentieth-century vision of Hungarian modern production and consumption. The texts started with the companies’ founding in the early twentieth century by industrial magnates, and then quickly moved from their wartime fates to the infrastructural modernization they enjoyed “after nationalization in 1948” that transformed them into electronics companies. The boards included logo designs, images of well-known products, and significantly, advertising campaigns from the 1970s that regularly circulated on digital retro venues. These featured young women in colorful bikinis or cut-off shorts, perched on stereo Hi-Fi receivers or on brand-name televisions (figures 15 and 17). The boards also celebrated the “veritable competition” that developed between the two companies in the 1960s. Videoton, for example, “won the contract” for the car radio in the [Bulgarian] Zsiguli, and by the end of the 1980s, “Videoton was the largest and most modern electronic media company in central Eastern Europe.” Exhibit attendees would be aware that Videoton, located less than an hour away in Székesfehérvár, was a Hungarian success story. Unlike its rival, Orion, it not only survived the decades after 1990, but is still in Hungarian hands, with its CEO, the right-wing media mogul Gábor Széles, regularly listed as among the richest Hungarians in Forbes Hungary.

Figure 15: Section of Orion Electronics Company board, with inset advertisement. Author’s photo, 2014.

In this narrated trajectory, there is no reference to a “socialist era,” nor to the discontinuities created by shifting from private company to state-owned firm to holding corporation. Instead, the twentieth-century history of the company is unified by the brand names Videoton and Orion, the Latinate names and modern logos the companies did not receive until the 1960s. Instead of central planning, the text emphasizes the market competition between state-owned firms as well as between firms within COMECON for major contracts.

Retro Online

These themes are elaborated online, as thousands of Hungarian-speakers participate in the production of a Hungarian Retro. Unlike physical sites, online sites encourage discussion, evaluation, and information-sharing, and enable the exponential increase in what can be circulated. Online forums can also bring retro to life with video clips, photographs of ordinary people, newspaper articles of popular events, or promotion material for leisure-pursuits. Unlike the fixed arrangements in physical exhibits, online sites encourage postings that can be searched and sorted in a myriad of ways.

Figure 16: RETRONOM.HU home page banner. Screengrab, 27 May 2021.

There are many digital archives, collections, and online marketplaces, many of which I used in my research. Here, I discuss one of the first, the site Retronom.hu (figure 16). It was founded by two men in 2003 as a public repository for digitized material from the past. Joining “retro” with “metronome” to make Retronom.hu, they decided on the timeframe of 1900 to 1999. The site includes old photographs, magazines, electronics, advertising, games, cigarette packaging, and so on. Eventually, the founders made it possible for people to use the site to buy and sell. This possibility, as Bach has observed for the “socialist nostalgia” market (2015b), imbued old things with new value as commodities, proof that some people at least were willing to pay for them.

Like other online retro sites, Retronom.hu presents Hungarian participation in a modern twentieth century. A search through Retronom.hu’s thousands of posted newspaper clippings suggests that the public was kept fully abreast of international events, including Yuri Gagarin’s monumental space flight in 1961, the Munich Olympics hostage crisis of 1972, and Princess Diana’s wedding in 1983. At the same time, there is next to nothing on political events specific to Communist countries, or to János Kádár or other political leaders.Footnote 28 The modern past as a “socialist” past can be glimpsed here and there, as in mementos from childhood such as Young Pioneer booklets. But these are decontextualized from socialist political connotations by being grouped with prewar Boy Scout materials.

While products from other countries—both East and West—are posted on Retronom.hu, the focus is on the Hungarian people, places, and products that fit a contemporary retro aesthetic. These include Hungarian media and sports celebrities, especially the country’s “Golden Team” of soccer and their 6 to 3 victory over England in 1953. They include sites of modern, consumer leisure time (cafes and restaurants, Balaton vacation resorts), products of Hungarian design and production, and the modern corporate logos of memorable Hungarian firms. They also include the kinds of technologies, like cameras or hair dryers, that allowed Hungarians to craft themselves into modern, fashion-conscious subjects of the time.

Central to all of these was their design and the ways they were advertised and otherwise circulated on television, radio, and the pages of newspaper and glossy magazines, producing an apolitical dreamworld of commercial modernity in state-socialist Hungary. The same set of iconic commercial posters for well-known Hungarian companies and their branded products in Retronom.hu are also featured on Pinterest and Instagram retro sites. These include the classic Art Deco poster for Tungsram lightbulbs from the 1920s, the Csepel motorcycle poster from the 1940s, and various ads for Fabulon suntan lotion and cosmetics from the 1970s. Videoton and Orion circulate as much for their sexually-provocative ads—themselves important indexes of the modern—as for the quality of their products (figure 17).

Figure 17: Videoton boombox ad from 1984. Screengrab, 2020.

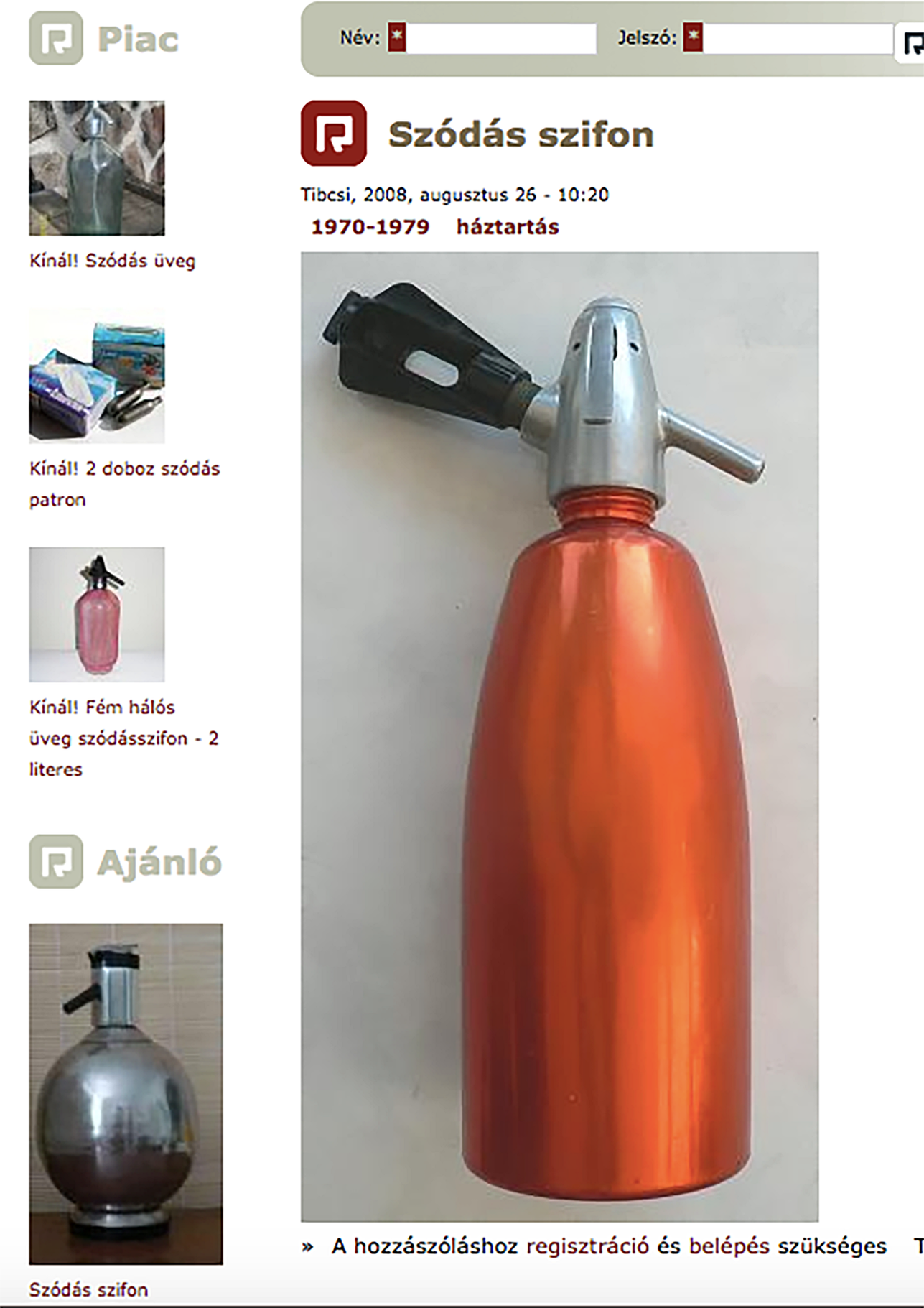

The persuasiveness of Hungarian Retro’s revisionist history also depends on evidence of “quality” products of the era made in Hungary, such as the iconic chrome soda cannisters made by the Lehel factory (figure 18). Three Videoton stereo amplifiers and two Orion speakers were in the top fifteen of the most-searched objects on Retronom.hu. The most sought-after good, after the Hungarian socialist version of Monopoly, was the Hungarian HAJDU Energomat-Thermal Washing Machine from 1983 (figure 19), and not the Soviet Eureka ridiculed by talk show hosts as socialist kitsch (Pope-Fischer Reference Pope Fischer2017). Indeed, the durable material capacities of some goods form the basis for new forms of sociality. Membership in the Hungarian Riga Moped Club, for example, requires ownership of a working Riga, Verhovina, Delta, Stella, Fora, or Kárpátia moped—all brands made in Soviet Eastern Europe and sold in Hungary. Club members communicate via their webpage about the bikes, parts, and repair, and organize excursions for the mostly older members.

Figure 18: LEHEL chrome soda maker, 1970s, Retronom.hu. Screengrab, 2020.

Figure 19: HAJDU Energomat-Thermal washing machine, 1983, Retronom.hu. Screengrab, 2020.

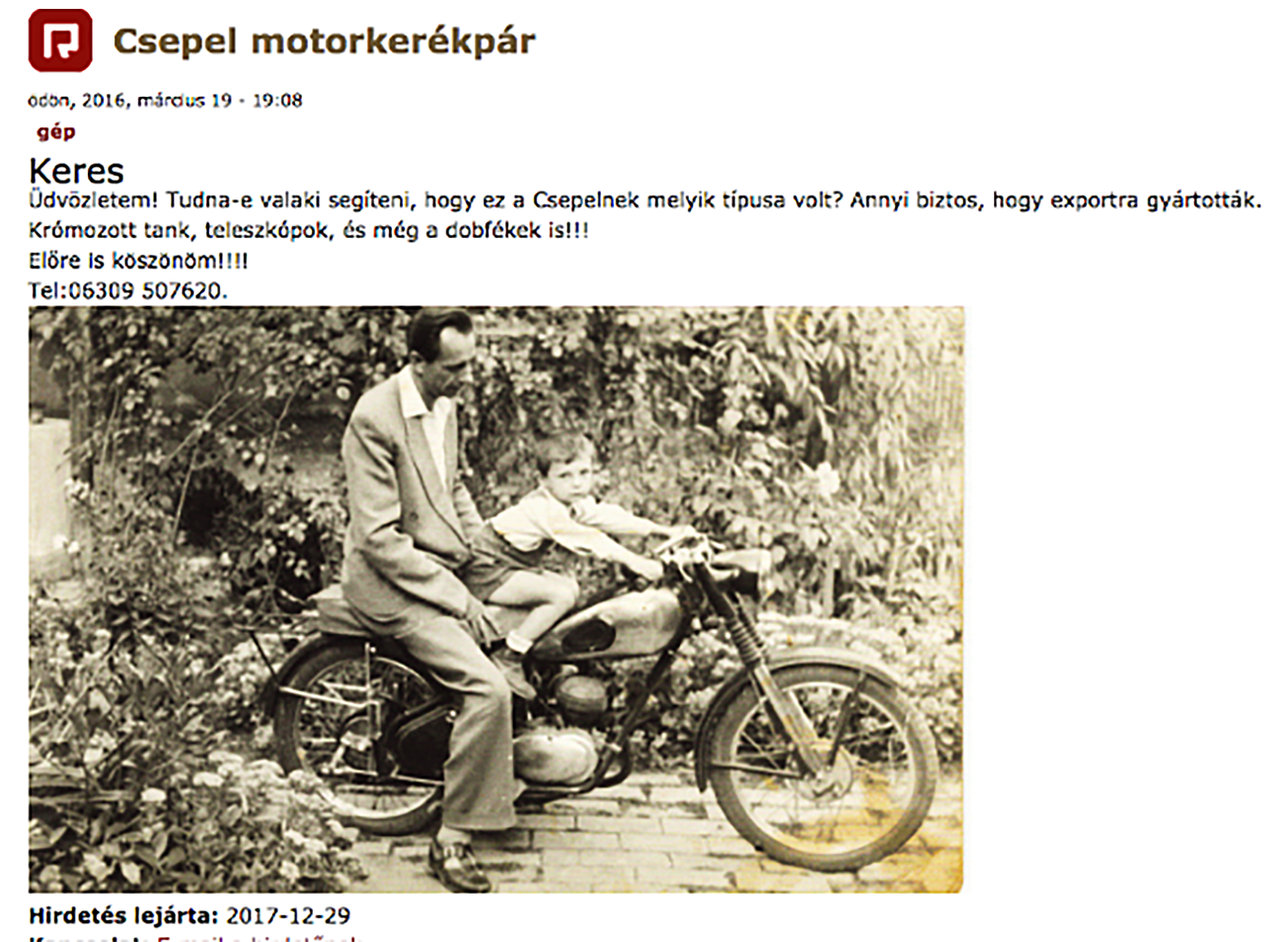

Like other online retro sites, Retronom.hu allows for commentary on posted items, and viewers often praise or contest the qualities of objects. While the occasional troll surfaces to malign the state-socialist period and its remains, the main practice is to deliberate the merits and commercial value of the items rather than musing on the memories they occasion. An example from Retronom.hu is a post of an old, faded family photograph, picturing a man seated on a “Csepel” motorcycle, wearing a casual suit, gazing at a small boy in shorts sitting in front of him (figure 20). The description reads: “Greetings! Can someone help with what type of Csepel this was? It was surely manufactured for export. Chrome tank, teleskop, and drum brakes too!!! Thanks in advance!!!!” These questions suggest the point of posting was not to elicit nostalgic sentiments, but to find out more about the design and export value of this Hungarian-made technology of modern mobility: to ascertain its value and what it said about the people that possessed it.

Figure 20: Csepel motorbike photo post to Retronom.hu, 2016. Screengrab, 2017.

III. Hungarian Retro as Revisionist History

As the above examples illustrate, Hungarian Retro serves the interests of the present, one where east Europeans have felt pressured to imitate not only the political and economic systems of the Euro-American West, but to acknowledge their moral superiority and even tastes (Bakke Reference Bakke2020). Retro provides evidence for a counternarrative of equivalence, one that rejects a derivative state-socialist modernity and with it the problematic sentiment of nostalgia. It suggests a domestic consumer culture archive full of material that matches the aesthetic criteria of retro styles elsewhere. Retro enthusiasts young and old can play with the old consumer goods unearthed from storage, revive familiar advertising jingles, TV shows, and cartoons, and reproduce fashions and leisure-time venues, all with retro’s disdain for conventional historical periodization. Indeed, as scholars on the use of popular culture and artistic motifs in Russia from Soviet times have found, such practices allow for a sense of continuity with the past rather than the rupture implied by socialist nostalgia (Oushakine Reference Oushakine2007; Pehe Reference Pehe2020; Platt Reference Platt2013).

For generations born after 1980, retro is also a framework that they can adopt with ease. The genre calls out the kind of subject position with which they are familiar, as consumers and connoisseurs, media publicists and designers, fashionistas, and technophiles, but not as workers on a factory assembly line. For them, the decades of state socialism are a distant history entirely disconnected from their own experience. Retro offers a flattering picture of the world they imagine their parents and grandparents inhabited, but it also allows them to participate in reviving the past in a way socialist nostalgia practices no longer can. Unlike socialist nostalgia, which built on shared experience of old consumer goods that remained unchanged for decades (Nadkarni Reference Nadkarni2020), retro relies on the aesthetic regimes made possible by rapid obsolescence. These become the mechanism by which people of different ages can enjoy retro revivals, offering up decades as styles to appropriate for fun. For both young and old, retro “matters” the past in a way that affirms contemporary market sensibilities, infusing it with value through assertions of market equivalence in the past and new value as commodities in the present.

We have seen how this re-mattering of Hungarian history in a capitalist idiom effaces state socialism. Indeed, Hungarian Retro greatly resembles what Michael Schudson (Reference Schudson1986) called “capitalist realism,” or the idealized world of consumer abundance conjured by capitalist advertising practices in the postwar West. Like capitalist realism, retro focuses on entertainment and leisure, and avoids anything that might mar its consumer-oriented picture of modern life as fun, colorful, youthful, and prosperous. Not only does the political vanish from Hungarian Retro, but so does urban poverty; pensioners, priests, or protesters; and peasants, farm animals, dirt roads or other signs of rural life (Valuch Reference Valuch2013). Popular but unfashionable clothing styles of the time are also missing, from the ubiquitous housedress to the working-class beret. Conspicuously absent is the East German Trabant, a car that tens of thousands drove in modern Hungary, and not just because Hungary never produced its own car. The Trabant, with a design unchanged over thirty years, has become iconic of socialist nostalgia.

The fact remains, however, that much of what is recruited for retro today was produced within a state-socialist political economy. The state owned most of the means of production, a majority of the working-age population was employed in state-sector factories, retail chains, farms, and public institutions, and a range of benefits were distributed through the workplace. Much has been written about the entanglements of “capitalist” and “communist” economies, but even in Hungary’s “goulash communism,” the political economic system was not capitalist.Footnote 29 So how does the retro that has emerged in Hungary manage its portrayal of a world of accessible, abundant, diverse, and even luxury goods? In this final section, I briefly address how such a reframing is possible by looking at the state-socialist consumer culture and manufacturing regime that produced them. In the process, I address the pitfalls of erasing the state-socialist political economy.

Much recent scholarship has shown that life during the state socialist period, particularly after the 1950s, was not the bleak and colorless existence posited in Cold War binaries (Reid Reference Reid2016). In Hungary, economic reforms in the manufacturing sector helped to increase the quantity and diversification of products on offer, including technologies that modernized household labor and offered home entertainment. Access to these goods grew over time. Since many were manufactured for export, they sported trademarked brands and were indeed often of higher quality. Unlike the Trabant, they were also technologies that were regularly redesigned and thus satisfy retro’s criteria for decade-specificity. Domestic production was also supplemented by importing goods and components from the West. Nevertheless, even the most industrialized of the state-socialist economic systems struggled with production and distribution, and with the quality and diversity of consumer goods.Footnote 30 While lack of product differentiation accompanied Fordist mass production everywhere, in Eastern Europe the unadorned, often unpackaged goods and impersonal modern retail environments came to stand in for the qualities of state-sector production in general. Needless to say, there is no place in Hungarian Retro for the “socialist generic” materialities that came to index the bureaucratic socialist state (Fehérváry Reference Fehérváry2009; Reference Fehérváry2013).

Over time, the state also innovated new retail venues and increasingly promoted advertising and branding practices, much of which is now celebrated as retro. Media scholar Anikó Imre has suggested that the commercial advertising that resembled Western forms reached for and presented a world that did not yet exist in state-socialist Hungary (Reference Imre2016: ch. 8). We might also say that the world in which this commercial culture existed, even as it drew on Western models, was an altogether different one (Patterson Reference Patterson, Bren and Neuburger2012; see also Gorsuch and Koenker Reference Gorsuch and Koenker2013). Commercial media, for example, was often designed to bolster pride in state-socialist manufacturing and to promote the modern lifestyles promised by a state-socialist political economy, rather than to stimulate sales of goods for profit.

As we have seen, retro selects for the material goods that embody idealized twentieth-century technologies, conform to contemporary design ideals, or hold up as substantial, well-made goods. To index “abundance,” retro collections often feature goods that were, in fact, selected for production early on in the Soviet Union to index abundance in quantity and diverse array, from everyday “treats” like candies and cigarettes to select luxury goods like champagne to be made available to the working masses in times of celebration (Gronow Reference Gronow2003). By the 1960s in Hungary, many such goods were available year-round. Care was spent on colorful packaging and branding to differentiate them, but also to promote a variety of projects or places (see Manning Reference Manning2012), from the 5-Year Plan to Lake Balaton. Retro collections of hundreds of cigarette cartons and candy-bar wrappers document the variety once produced in now-defunct Hungarian factories.

These modes of selection help to correct the “bleak and colorless” picture of everyday life for Hungarian citizens in the twentieth century’s second half, even as they obfuscate the negative realities of state socialist consumer culture: from persistent inequalities in access to higher quality goods to continuing problems with production and distribution. At the same time, some of the more laudable aspects of this political economy are also erased, particularly in retro’s celebration of “Hungarian” factories like Tisza or Videoton through the lens of contemporary corporate branding.

In today’s global, financialized capitalism, dominant corporate brands wield enormous power. The fame and value of these brands have increased exponentially as they circulate in the world, protected by international trademark agreements of the neoliberal economic era. Since much of what Hungarian manufacturing remains now goes out under global brands like Audi, Hungarian Retro attempts to reterritorialize and reclaim the quality of such manufacture by lionizing old Hungarian brand names and their modern logos. Hungarian Retro projects back into the twentieth century the power of today’s corporate brands in order to conjure a golden age of the Hungarian economy (figure 21). But the unifying device of the corporate brand obscures the de-territorialization of brand, as with the new Tiszas, and the vastly different political economies that produced retro goods. These brands reveal nothing about whether the property regime in Hungary was the industrial capitalism of the pre-socialist period, state ownership of factories and companies, or the forms of privatization that have characterized the postsocialist period.

Figure 21: Ikarus bus logo plate. Screengrab, 2018.

Hungarian Retro thus elides the fact that the purpose of state-socialist firms was not limited to success measured by profit: it was to produce employment as well as goods for the population, to use resources available domestically as much as possible, and to anchor the wider community via social benefits and extra-work life. However one evaluates the centrally planned economic system, it was oriented to the provision of modern goods to the entire citizenry and attempted to keep within a national budget, without being driven by profit for private owners or distant shareholders. Hungarian Retro also effaces the workers in these factories, identifying instead with the white-collar workers needed to design, engineer, and advertise brand-name consumer goods. Today, what matters is that these firms were in Hungarian hands over a company’s longue durée history, and that goods once “Made in Hungary” now provide evidence of a production system that worked. Forgotten are the century of struggles over whether this ownership should be the property of a family, private shareholders, workers, or the state.

IV. Conclusion

The retro genre is a mode of curation which selects those aspects of the modern past that conform to its unified, commercial aesthetic. Although elements of what are now called “retro” undeniably share in some of the features explored in the scholarship on “socialist nostalgia,” Hungarian Retro celebrates a national, commercial modernity, one that rejects state socialism as a legitimate way to frame or define the four decades from 1948 to 1989. Hungarian Retro re-matters history by curating and displaying objects from that era alongside items from a wider twentieth-century time frame and a global marketplace that does not recognize a Cold War divide. It draws on the genre of retro branding internationally and deploys it to bolster Hungarian pride and prestige via the selective evidence of its high-quality and fashionable commercial culture from the past. It is thus a powerful counter to the widespread narrative of abject state-socialist materialities and isolation from the modernity of the West, replacing it with that of a Hungarian twentieth-century consumer abundance and technological sophistication—evidence of lives lived with the latest consumer technologies from all over the world, East and West, and also products of Hungarian innovation, design, and manufacture.

In many respects, Hungarian Retro, with its urban, cosmopolitan air and its celebration of branded goods from the state-socialist period, appears diametrically opposed to right-wing nationalism in Hungary. Indeed, some sympathizers with neo-nationalist groups oppose retro’s revisionist narrative, in part because of their virulent anti-Communism. Others reject it in much the same way a right-wing nationalist in the United States might reject hipster style as undignified and incompatible with their “Hungarian” identity. As we have seen, right-wing groups champion Hungarian mythic exceptionalism for a domestic audience, consuming commodities like nationalist fashion brands, irredentist stickers, and heavy metal music. Likewise, the nationalist, conservative Fidesz government promotes “uniquely” Hungarian, traditional places and products that predate the state-socialist period (image 22).

Figure 22: Online post of the Túró Rudi as Hungarikum. Screengrab, 2014.

However, Hungarian Retro shares in these nationalist projects to elide the state-socialist political and production regimes. While the conservative government tries to purge the country of the remains of state socialism and reaches back to pre-socialist times to fortify the present through Hungarikum products, Hungarian Retro re-matters Hungary’s place in a twentieth-century modern European history without state socialism. A wry, racist post from 2014 in the blogosphere brings these together, by displaying an image of the Túró Rudi candy bar in its distinctive polka dot packaging, proclaiming: “This is the real hungarikum, not gypsy music!” The intimation is that, instead of dwelling on touristic symbols of national identity like the music Roma bands play in tourist locales, the real focus of Hungarian national pride should be on a modern, branded product like the Túró Rudi, one that debuted in 1968, has an international following, and continues to be a national favorite. Unlike socialist nostalgia, Hungarian Retro helps to erase state socialism from Hungarian history and allows for the resurrection of the “lost decades” of the 1950s to the 1980s as a golden age of Hungarian commercial prestige and economic sovereignty.

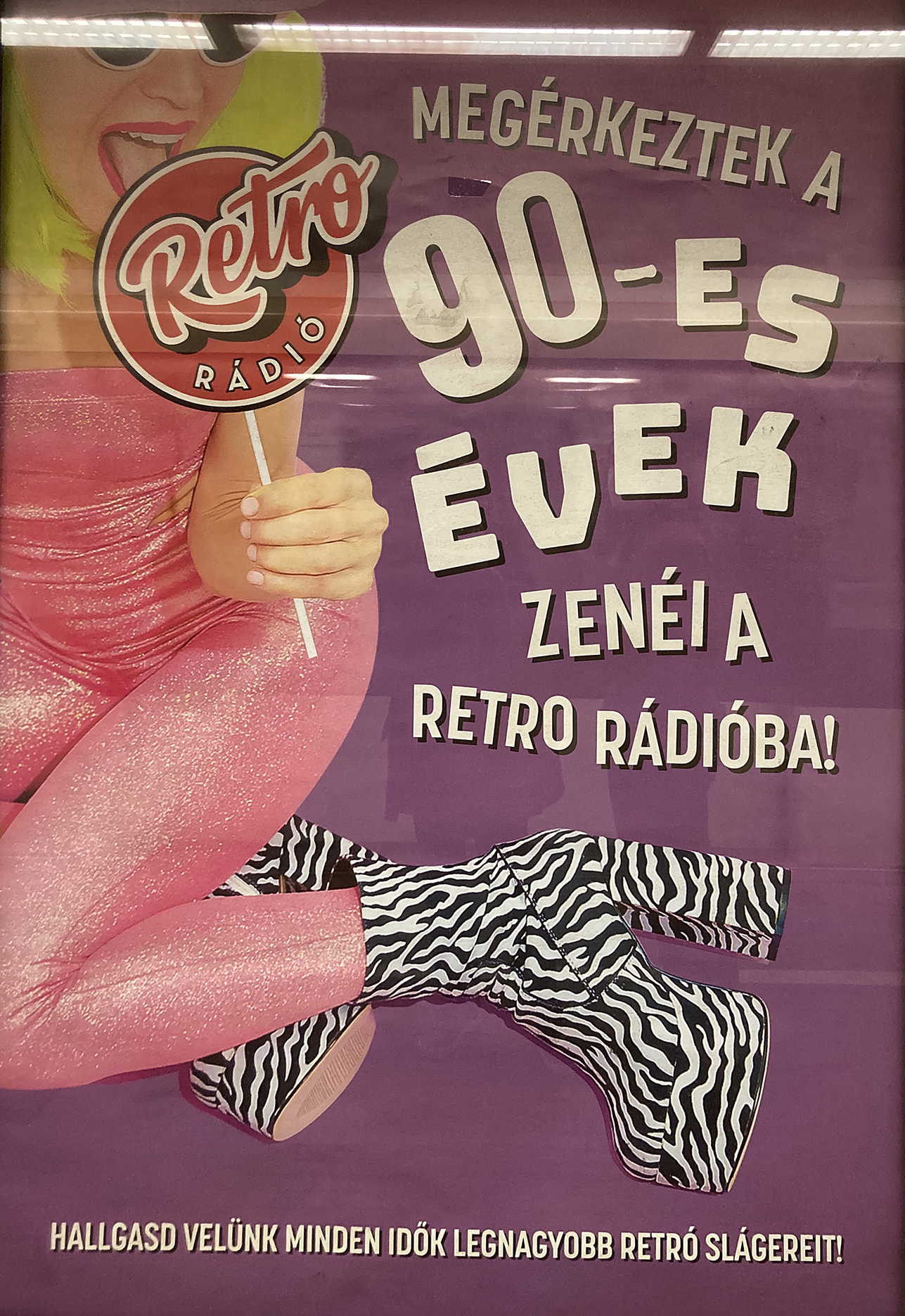

An ironic coda to this story is that, by 2017, the Fidesz regime finally recognized the potential convergence of retro with its own agenda, backing a new nation-wide classic rock radio station called “Retro Rádió” playing “the greatest hits from the 60s, 70s and 80s,” and then adding the 1990s (figure 23). It remains to be seen whether Hungarian Retro’s de-stigmatizing of the commercial culture of socialist-era decades might eventually lead to reevaluations of other aspects of the state-socialist system itself.

Figure 23: Poster in a Budapest metro station: “Music from the 90s has arrived at Retro Radio!” Author’s photo, 2021.